1. Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, providing an opportunity for countries and their societies to embark on a new path aimed at improving the lives of all, while leaving no one behind. This agenda set forth objectives including the elimination of poverty, combating climate change, advancing education, promoting women's equality, protecting the environment, and redesigning our cities, among other objectives. Goal two, Zero Hunger, stablished a target for 2030 to eradicate all forms of malnutrition. This includes meeting the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under five years of age by 2030, as well as addressing the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women, and the elderly [

8].

From a conceptual standpoint, malnutrition results from prolonged food deprivation, which occurs when conditions of undernourishment persist over time in a territory. This leads to physiological adaptations in the body necessary for survival, going through acute states that can be fatal or leading to chronicity and growth arrest, with direct consequences on the proper growth and adequate development of children [

9] . Malnutrition can be classified into two types: primary, which is associated with a reduction in food consumption or use (due to scarcity or access difficulties), and secondary, which is linked to an underlying pathology.

In general, primary malnutrition is entirely preventable. In Colombia, the country has the capacity to produce the food necessary for its population [

10]. However, not all families have access to the necessary amounts of food to lead healthy lives. Indeed, 28.1% of households experience moderate to severe food insecurity, indicating compromised quality and variety of food, reduced food quantities, or instances of hunger [

11]. Although the prevalence of malnutrition varies depending on the territorial context (as conditions differ between departments experiencing drought or food supply issues compared to those without), wasting is a phenomenon that occurs across all Colombian departments. In 2023, moderate and severe wasting affected children who were born underweight, belonged to low socioeconomic strata, or had mothers with lower educational levels. The national prevalence of moderate or severe wasting in children under five, as reported by health services for the first half of 2023, was 0.31% in Colombia, an increase from 0.27% during the same period in 2022 [

12]. This reported prevalence is lower than the actual population prevalence, due to the underreporting of this condition.

Child malnutrition in Colombia continues to be an alarming issue that profoundly impacts the lives of many children. According to the National Survey of the Nutritional Situation in Colombia (ENSIN) [

13], one in ten children experiences stunting, and about two out of every hundred suffer from wasting. This represents around half a million infants nationwide [

14]. The root causes of this significant issue extend beyond mere food scarcity and include factors such as poverty, inadequate access to clean water, basic sanitation services, and insufficient parental education [

15,

16].

The consequences of child malnutrition are multifaceted. Children afflicted with malnutrition not only encounter an increased risk of mortality and susceptibility to diseases such as acute diarrheal disease (ADD) and acute respiratory infection (ARI), but their growth and cognitive development are also compromised [

2,

17]. This translates into challenges in learning and full development, which subsequently curtail their future opportunities and perpetuate the cycle of poverty in which they are entrenched [

18,

19]. Moreover, the Colombian health system incurs significant costs in addressing the complications associated with malnutrition, an aspect that has yet to be analyzed from a societal perspective.

Therefore, determining the burden of disease associated with malnutrition in a country that has the tools and resources to prevent it allows action to be taken and prevents an unjust and avoidable phenomenon from continuing its course. This research seeks to answer the following question: what is the burden of disease attributable to malnutrition in Colombia, and its economic impact from a societal perspective?

3. Results

3.1. Burden of Disease

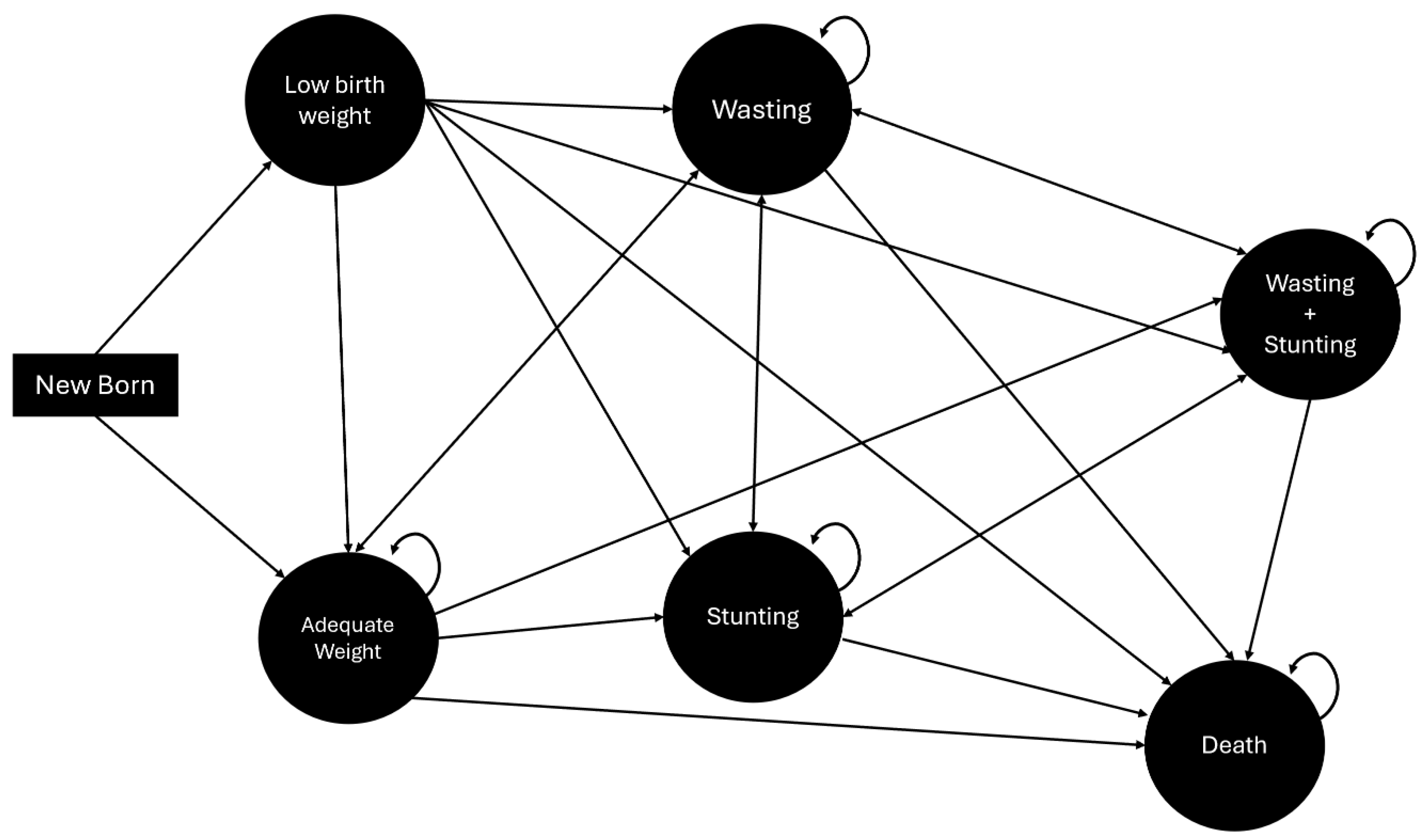

The Markov model estimate indicates that DALYs for malnutrition in Colombia correspond to 419.84 per 1,000 inhabitants during the first four years of life.

Table 2 and

Figure 2 present the summary of DALY, YLL, and YLD results. The data suggest that YLL significantly contributes to the increase in DALYs over time.

3.2. Direct and Indirect Costs

After reviewing the literature on direct cost data collection, priority was accorded to studies that provided analyses of national costs. Subsequent sections detail the costs associated with wasting, particularly those linked to ARI and ADD. Additionally, costs related to height delay are outlined, specifically the expenses for delayed psychomotor development, which include three weekly occupational therapy sessions after the age of 2 years. To ensure comparability among the various cost values, all figures have been adjusted for inflation. This adjustment ensures that the presented costs reflect up-to-date and comparable economic values, facilitating more accurate interpretations.

Table 3 present the results of the direct and indirect costs per cycle and the cumulative total for the first four years.

The results of the indirect cost analysis reveal that the total reaches USD

$243.576.094,12 over the four-year period analyzed.

Table 3 illustrates the evolution of indirect costs for each cycle.

At the time of the survey, most children were categorized under Nutritional Recovery, followed by Home Management with follow-up and re-entry to Nutritional Recovery. Among the surveyed children, 76.19% were identified as experiencing wasting.

Regarding demographic details, the children primarily belonged to socioeconomic strata 1, 2, and 3, with a prevalence in strata 1 and 2 (91%). The majority were covered under the subsidized health insurance regime (74.4%), with 23.3% under the contributory regime, and 2.3% uninsured. None of the respondents had additional insurance or supplementary plans.

Household characteristics indicated that the largest proportion resided in stratum 1 (55.8%), with 62.8% residing in urban areas. Most households did not include children under 5 years of age, individuals over 65 years of age, pregnant women, or disabled persons (See Annex 1).

Among the categories of annual out-of-pocket expenses, transportation incurred the highest costs at $451.76 USD, followed by food at $225.88 USD, and stationery at $84.71 USD. When analyzing indirect costs by socioeconomic strata, transportation and food consistently showed the highest expenses across strata 1, 2, and 3. Additionally, the most substantial out-of-pocket expenses occurred during hospitalization, totaling $971.89 USD. Detailed figures for these expenditures are available in Annex 2, which reveals that the average annual per capita expenditure for households is $162.98 USD.

According to the characteristics of the caregivers surveyed, the average age was 37 years. A significant majority (95.35%) were mothers, and 65% were not the heads of their households. The predominant affiliation regime was subsidized (74.4%). The highest level of schooling reported was high school, with 62.8% of caregivers having this educational background. Regarding occupation, 44.19% were engaged in household chores, and 25.58% were involved in informal work. Most caregivers did not cease their activities for child care, a situation most prevalent among those engaged in household chores. This finding suggests a lack of support for child care in most cases, as detailed in Annex 3.

In terms of the economic characteristics of the households, the average income per household was observed to be $352.21 USD, while per capita income averaged $190.34 USD. It was noted that most households did not have alternative sources of income.

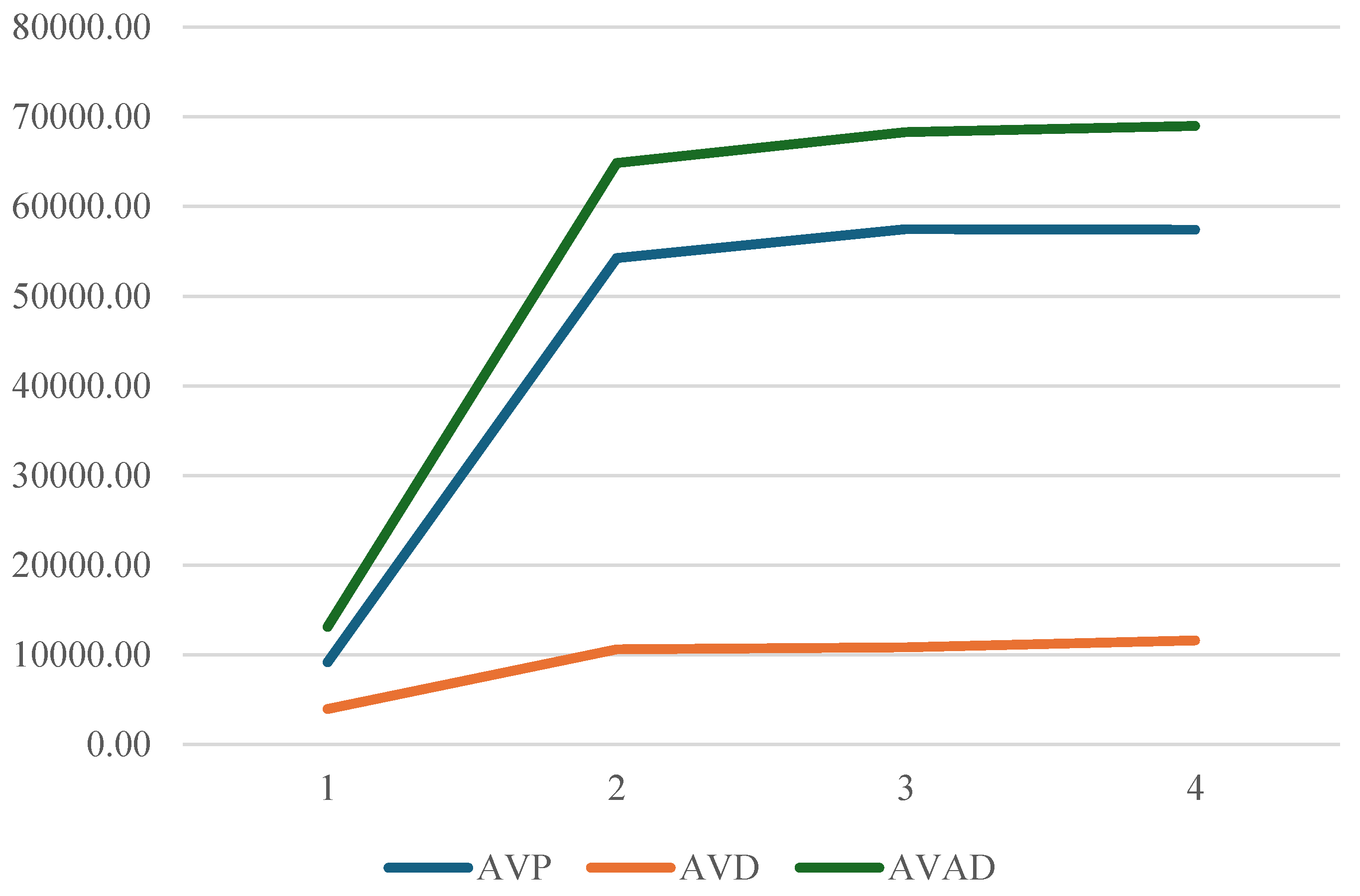

3.3. Economic Burden

The analysis of costs associated with malnutrition in Colombia reveals that direct costs amount to

$128.92 million USD, whereas indirect costs tally up to

$243.58 million USD. This results in a total cost of

$372.50 million USD over the first four years of the cohort's life. Additionally, DALYs per 1,000 inhabitants are found to be 419.8.

Table 4 illustrate the detailed breakdown and evolution of these costs over time.

The primary financial burden lies with indirect costs, constituting 65% of the total costs, in contrast to the 35% represented by direct costs. An increasing cost trajectory over time is noted, particularly after the second year of life, when households are required to cover two-thirds of occupational therapy costs as out-of-pocket expenses.

A comparison of these expenditures to the per capita income of individuals right above the extreme monetary poverty line and the monetary poverty line (According to the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), for the year 2022, the per capita extreme monetary poverty line was set at 198,698 Colombian pesos per month, while the monetary poverty line was established at 396,864 Colombian pesos per month.) reveals significant disparities. Specifically, the average annual out-of-pocket expenditure amounts to 123.4% of the total annual income for individuals right above the extreme poverty line, and 61.8% for those right above the monetary poverty line. Such economic strains suggest that, for households, coping with an income shock resulting from child malnutrition could lead to a higher incidence of monetary and extreme monetary poverty, restricting household spending flexibility in a manner that perpetuates poverty and deepens existing inequities.

4. Discussion

Child malnutrition is a completely preventable public health issue. No child should succumb to this condition, especially in a country with abundant and diverse food resources like Colombia. This problem is linked to health inequities and serves as a catalyst for the loss of human capital and the growth potential of society. Malnutrition contributes to cognitive decline, resulting in delayed school entry, poor academic performance, and decreased graduation rates [

3,

18,

19,

28]. Poor fetal growth or stunted growth within the first two years of life leads to irreversible damage, including shorter adult stature, lower educational attainment, reduced adult income, and lower birth weight in subsequent generations.

This study represents the first comprehensive assessment of the burden of malnutrition from a societal perspective in Colombia. Our findings indicate that the DALYs for child malnutrition in the first four years of life are 419.8 per 1,000 inhabitants. Despite high health coverage, a considerable proportion of the associated costs are borne by households: of the total costs attributable to child malnutrition, 32% are indirect costs assumed by households, while 68% are direct costs covered by the health system.

Several studies have shown a correlation between birth weight, subsequent nutritional status, and the development of diseases in adult life [

29,

30,

31]. This evidence highlights the importance of early interventions, particularly before the age of five, as a critical period for improving nutritional outcomes. According to one study, approximately 85% of children born with very low birth weight and 53% of those born with extremely low birth weight achieve normal height by the age of 4. However, children who remain short-statured at age 4 are unlikely to attain normal adult height [

32].

In 2014, the most recent study on the burden of disease in Colombia was published, utilizing data from 2010. It identified low birth weight as the primary cause of disease burden among children under five years of age, with 134 total DALYs in males and 144 in females. This was followed by asphyxia and birth trauma, accounting for 46 DALYs in males and 48 in females. The study also reported protein-calorie malnutrition with 4 DALYs in males and 5 in females per 1,000 children, and lower respiratory tract infections with 8.3 DALYs in males and 9.9 in females per 1,000 children [

5]. Additionally, a descriptive study conducted in Colombia reported the years of life lost due to premature mortality associated with child malnutrition, which ranged from 1,162 in 2016 to 6,411 in 2019. The years lived with disability varied from 1,239 in 2016 to 2,257 in 2019, corresponding to 2,402 DALYs in 2016 and 8,668 DALYs in 2019 [

33].

According to the 2016 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, diarrheal diseases accounted for approximately 40,125,700 DALYs due to the incidence of diarrhea and associated fatalities among children under five years of age, resulting in about 446,000 deaths (with a range of 390,900 to 504,600) and 1.105 billion episodes (ranging from 962 million to 1.275 billion). After including long-term sequelae associated with malnutrition, diarrhea contributed to an increased total of 55,778,000 DALYs, marking an almost 40% increase (39.0%, with a range of 33.0% to 46.6%) [

34].

To mitigate these effects, it is crucial to implement intervention strategies that encompass child nutrition programs and health education, particularly focusing on the first 1000 days of life. This period is critical for optimal brain growth and development [

35]. The findings of this study highlight the significance of such interventions: caregivers reported that malnutrition adversely affected both the health of children and household income, with 38.1% of households experiencing a decrease in income due to child malnutrition.

Although wasting is a notifiable condition in Colombia through its epidemiological surveillance system, SIVIGILA, there are significant gaps in the reporting mechanisms. Notably, stunting does not require mandatory reporting, and the data collected do not fully reflect the population's reality due to known issues of underreporting. This discrepancy arises because not all medical consultations classify nutritional status, and not all children suffering from malnutrition, whether acute or chronic, seek healthcare services. As a result, population statistics, which are typically reported by five-year surveys conducted in 2005, 2010, and 2015 [

13,

36,

37], should have been utilized. However, since there have been no updates since 2015, data from that year must be used as the most recent. Further research is essential, particularly longitudinal studies that explore the outcomes of child malnutrition, including changes in body composition and other developmental trajectories [

38].

It can be inferred from the information reported by the National Institute of Health [

12] and the Ombudsman's Office (Defensoría del Pueblo) for Colombia in 2023, that there is evidence of an increase in cases of child malnutrition both in its prevalence and in associated mortality, as there is a reported increase of 56.3% in infant mortality and 34.9% in cases of moderate and severe wasting [

39].

An inverse relationship has been established between public social expenditure and stunting; that is, as public social expenditure increases, the prevalence of stunting decreases. Consequently, it is imperative that governments in Latin America allocate greater budgetary resources to formulate comprehensive early childhood care policies. Such policies are essential not only for reducing stunting rates but also for fostering long-term sustainable development in the region [

40].

Within the context of the sociodemographic characteristics of households experiencing wasting, it is crucial to note that the findings of this study reflect the cyclical nature of the wasting scourge, encompassing poverty, hunger, and malnutrition. These conditions are often the result of low-paying jobs or unemployment, low educational levels among caregivers, and inadequate income to ensure food and nutrition security (FNS) in the household [

41].

One of the significant challenges in studying the burden of disease for child malnutrition is achieving a level of regional and territorial disaggregation that supports intersectoral decision-making at the local level. This is crucial, as addressing the issue requires coordinated efforts across various social determinants of health. Combating child malnutrition in Colombia needs an integrated strategy that incorporates food security policies, nutrition programs, and health education. The data and studies reviewed highlight the need to approach malnutrition not only as a public health issue but also as an economic and social imperative for the country's sustainable development. Implementing effective policies and early intervention programs is vital to reducing the burden of malnutrition and enhancing the quality of life for affected children and their households.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Taborda and Londoño methodology Taborda, De la Hoz and Londoño. Software De la Hoz.; validation: Londoño, Taborda, De la Hoz, Burgos, Arbelaez and Pineda; formal analysis, De la Hoz, Burgos, Arbelaez and Pineda, investigation, Taborda.; resources.; data curation Londoño, Taborda.; writing—original draft preparation, Londoño AND Taborda.; writing—review and editing, Londoño, Taborda, De la Hoz, Burgos, Arbelaez and Pineda.; visualization, Londoño, Taborda, De la Hoz, Burgos, Arbelaez and Pineda.; supervision, Londoño.; project administration, Taborda and Londoño.; funding acquisition N/A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding: “This research received no external funding, was funded by the Éxito Foundation and the Santa Fé de Bogotá Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement: “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of SANTA FE DE BOGOTÁ (protocol code 15280-2023 and April 24th/2023).”

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement: Consolidated survey data are in Appendices 1 to 3.

Acknowledgments: We thank Dr. Jorge Botero and Dr. Mauricio Sierra for their contribution as clinical experts, Dr. Gilma Hernandez for her statistical contribution. In the same way, to the institutions that allowed the collection of information: Santa Ana Children's Clinic and the Council of Medellín Children's Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.