Submitted:

14 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

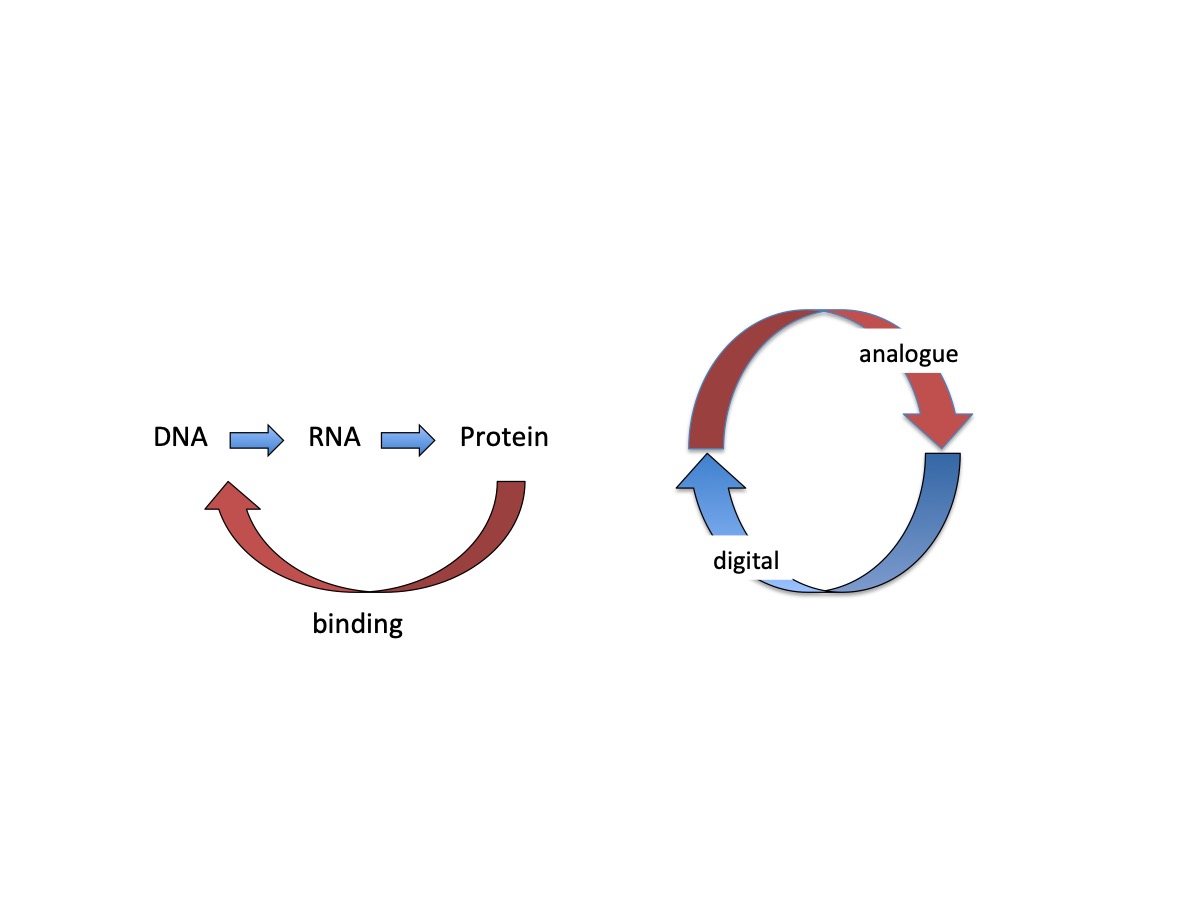

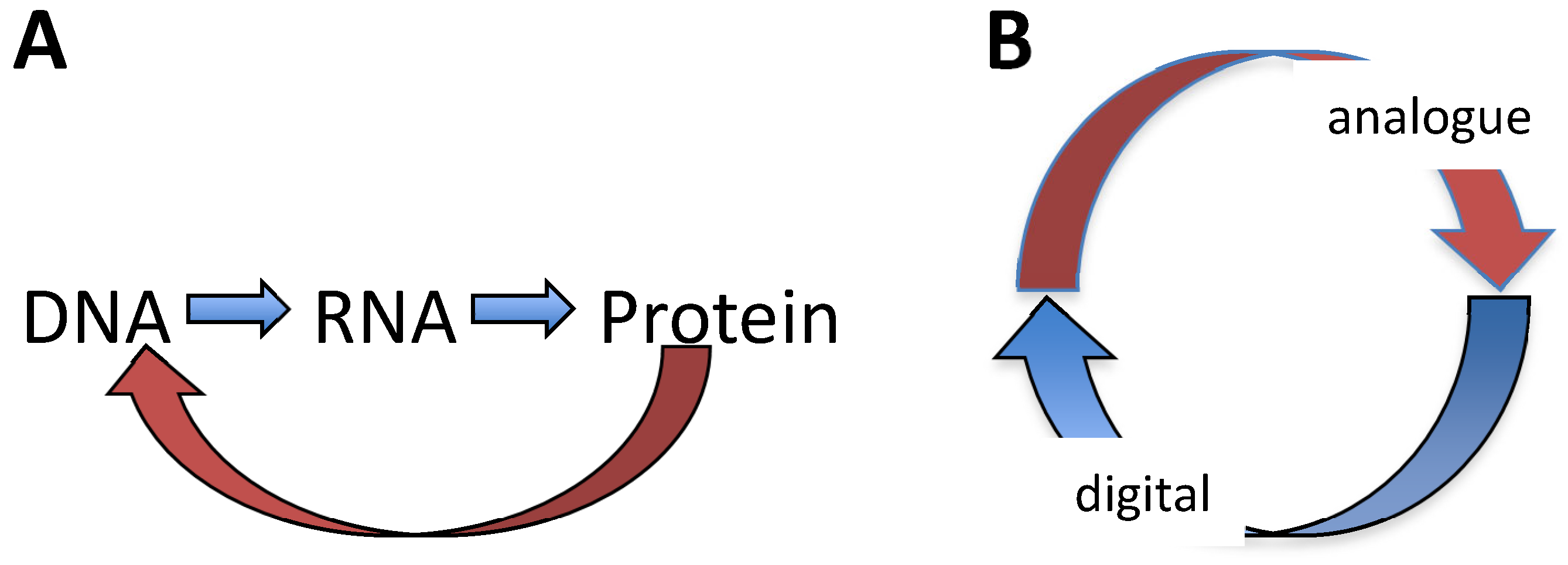

Living systems are capable on the one hand, of eliciting a coordinated response to changing environment (aka adaptation) and on the other hand, they are capable of reproducing themselves. Notably, adaptation to environmental change requires the monitoring of the surroundings, while reproduction requires monitoring oneself. These two tasks appear separate and making use of different sources of information. Yet both the process of adaptation as well as that of reproduction are inextricably coupled to alterations of genomic DNA expression, while a cell behaves as an indivisible unity in which apparently independent processes and mechanisms are both integrated and coordinated. We argue that at the most basic level, this integration is enabled by the unique property of the DNA to act as a double coding device harboring two logically distinct types of information. We review biological systems of different complexity and infer that inter-conversion of these two distinct types of DNA information represents a fundamental self-referential device underlying both systemic integration and coordinated adaptive response.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

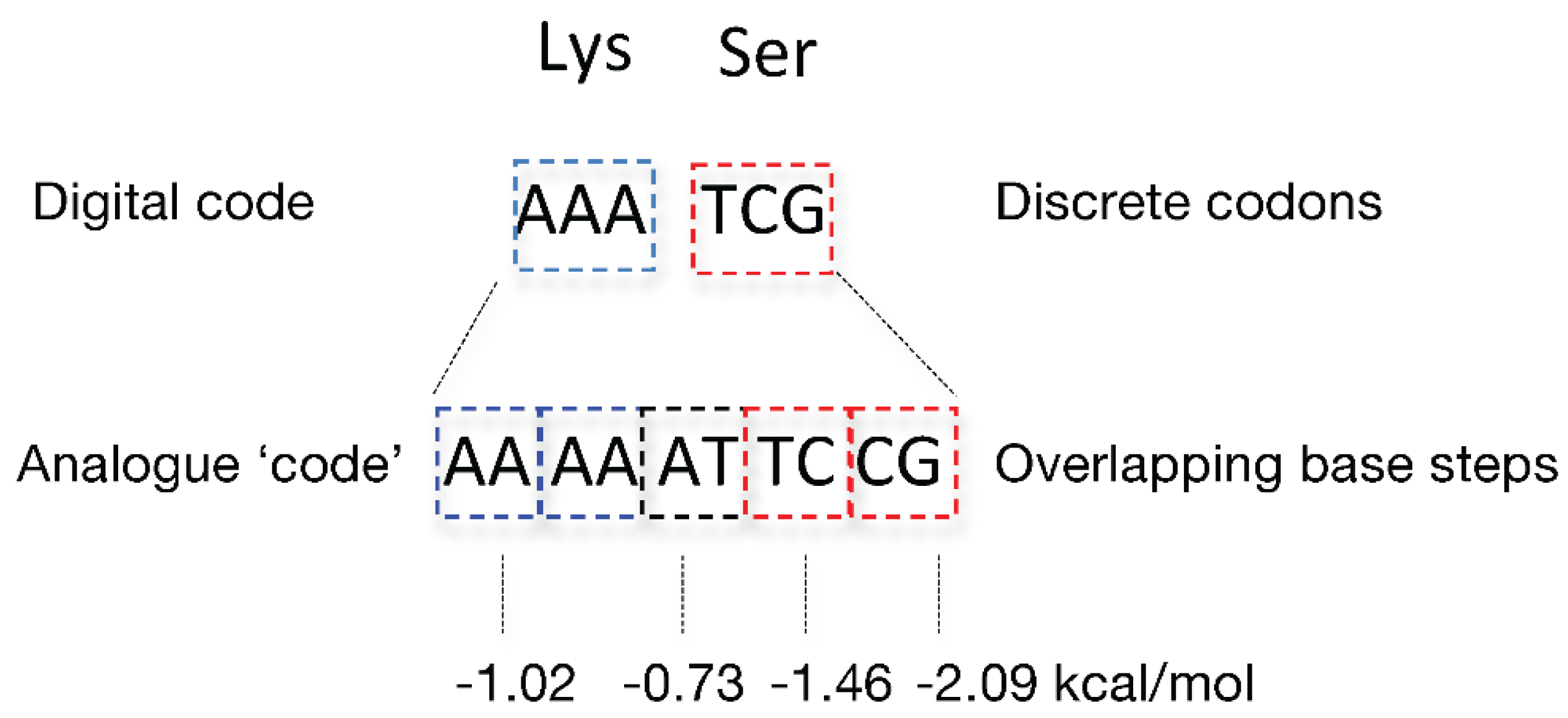

2. DNA Is a Source of Two Distinct Types of Information

3. Coupling of Logically Distinct Types of Information

4. Switching between Alternative Gene Expression Programs

5. Analogue/Digital Information Conversion Operates as a Regulatory Device in Living Systems of Diverse Structural Complexity

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaufman L.H. Self reference and recursive forms. J. Social Biol. Struct. (1987)10, 53-72. 1987 Academic Press Inc. (London) Limited.

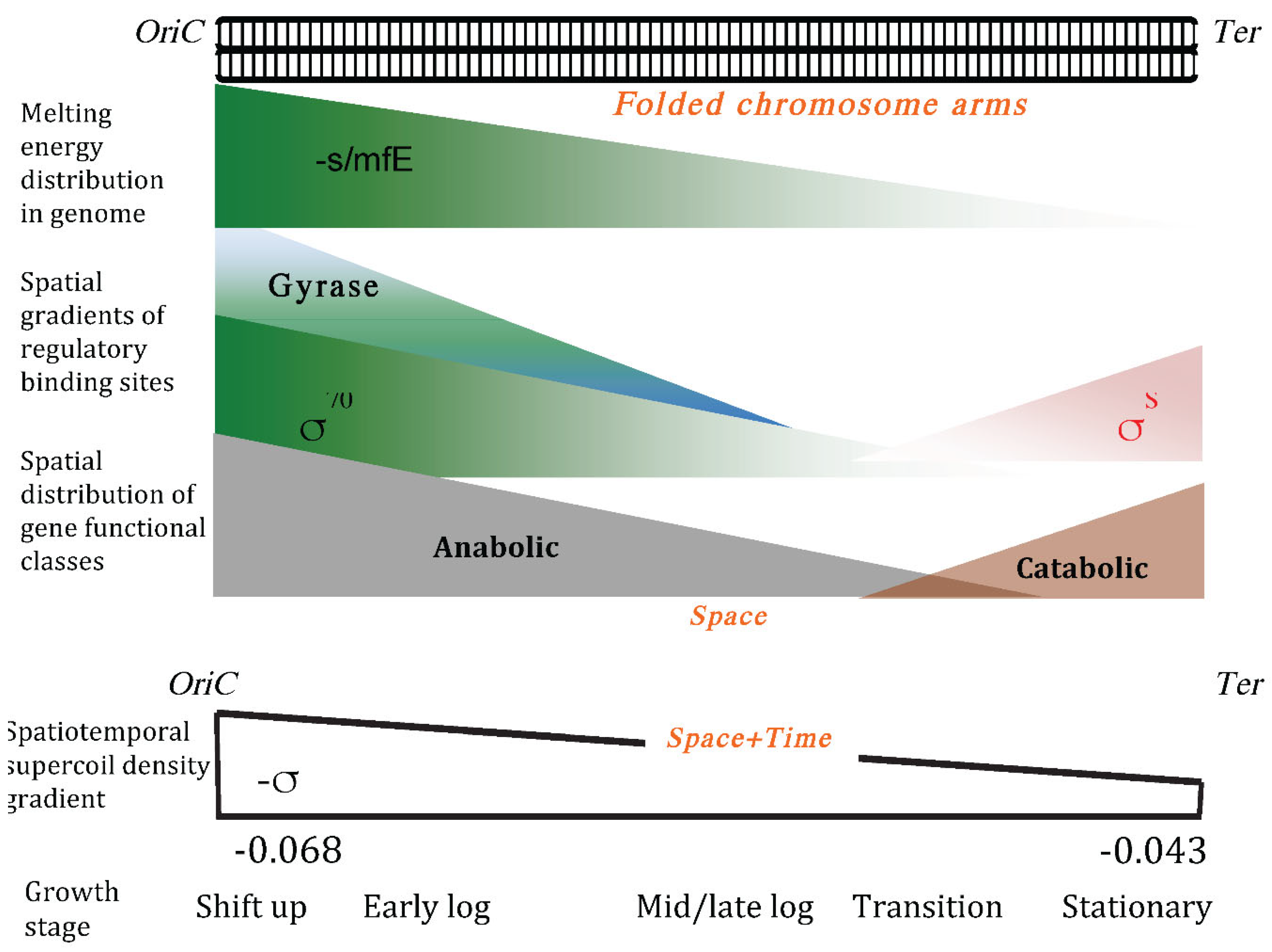

- Muskhelishvili G, Sobetzko P, Travers A. Spatiotemporal Coupling of DNA Supercoiling and Genomic Sequence Organization-A Timing Chain for the Bacterial Growth Cycle? Biomolecules. 2022 Jun 15;12(6):831. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruijtenberg S, van den Heuvel S. Coordinating cell proliferation and differentiation: Antagonism between cell cycle regulators and cell type-specific gene expression. Cell Cycle. 2016;15(2):196-212. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papenfort K, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing signal-response systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016 Aug 11;14(9):576-88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunez-Lamas M, Cabrera E, Lopez-Solanilla E, Solano R, González-Melendi P, Chico JM, Toth I, Birch P, Pritchard L, Liu H, Rodriguez-Palenzuela P. Bacterial chemoattraction towards jasmonate plays a role in the entry of Dickeya dadantii through wounded tissues. Mol Microbiol. 2009 Nov;74(3):662-71. Epub 2009 Oct 8. Erratum in: Mol Microbiol. 2009 Dec;74(6):1543. Prichard, Leighton [corrected to Pritchard, Leighton]. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Río-Álvarez I, Muñoz-Gómez C, Navas-Vásquez M, Martínez-García PM, Antúnez-Lamas M, Rodríguez-Palenzuela P, López-Solanilla E. Role of Dickeya dadantii 3937 chemoreceptors in the entry to Arabidopsis leaves through wounds. Mol Plant Pathol. 2015 Sep;16(7):685-98. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang X, Zghidi-Abouzid O, Oger-Desfeux C, Hommais F, Greliche N, Muskhelishvili G, Nasser W, Reverchon S. Global transcriptional response of Dickeya dadantii to environmental stimuli relevant to the plant infection. Environ Microbiol. 2016 Nov;18(11):3651-3672. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallgren J, Koonce K, Felletti M, Mortier J, Turco E, Jonas K. Phosphate starvation decouples cell differentiation from DNA replication control in the dimorphic bacterium Caulobacter crescentus. PLoS Genet. 2023 Nov 27;19(11):e1010882. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrows JM, Goley ED. Synchronized Swarmers and Sticky Stalks: Caulobacter crescentus as a Model for Bacterial Cell Biology. J Bacteriol. 2023 Feb 22;205(2):e0038422. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudin O, Geiselmann J, Ogasawara H, Ishihama A, Lacour S. Repression of flagellar genes in exponential phase by CsgD and CpxR, two crucial modulators of Escherichia coli biofilm formation. J Bacteriol. 2014 Feb;196(3):707-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scolari VF, Bassetti B, Sclavi B, Lagomarsino MC. Gene clusters reflecting macrodomain structure respond to nucleoid perturbations. Mol Biosyst. 2011 Mar;7(3):878-88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobetzko P, Glinkowska M, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G. DNA thermodynamic stability and supercoil dynamics determine the gene expression program during the bacterial growth cycle. Mol Biosyst. 2013 Jul;9(7):1643-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

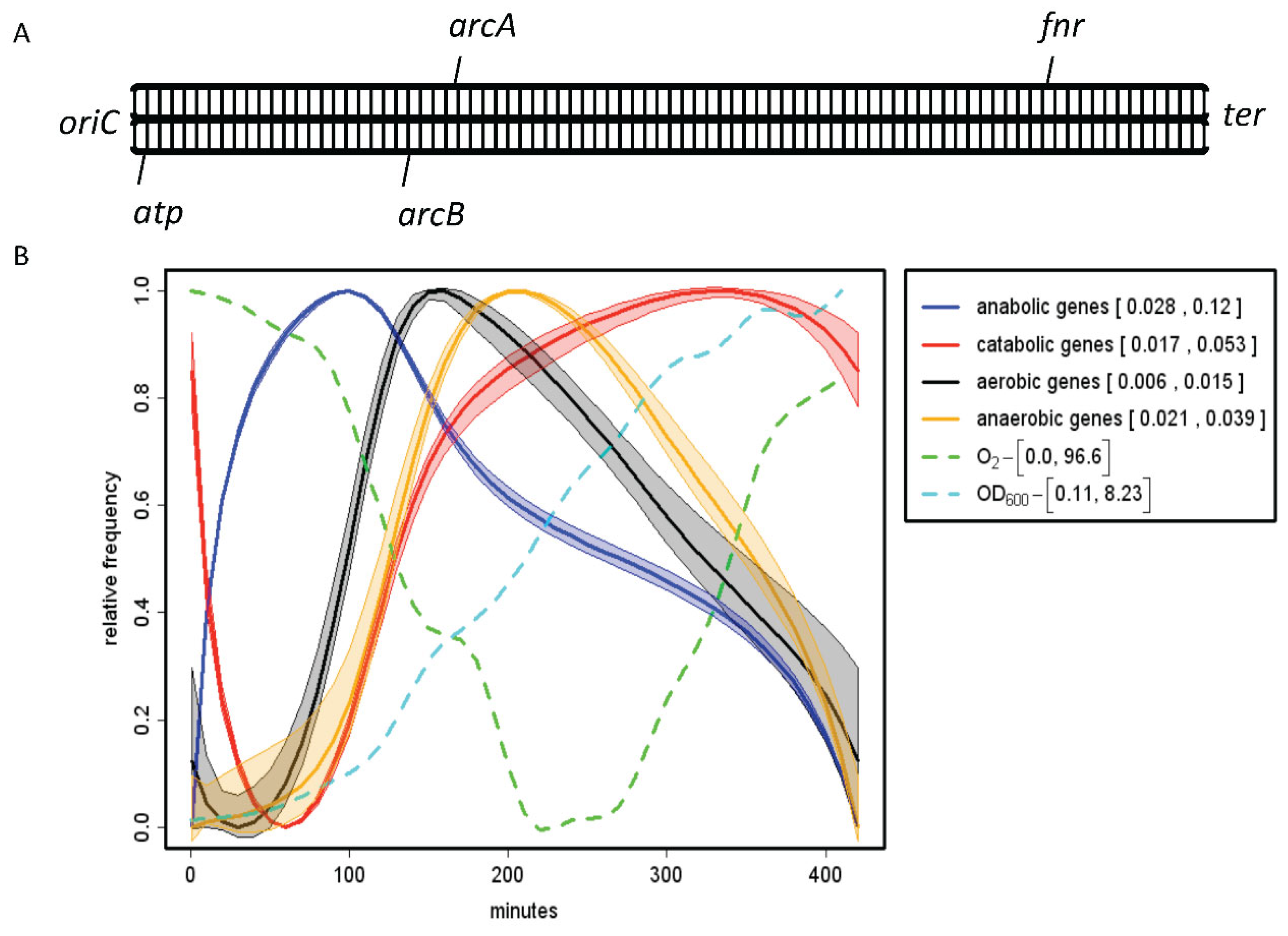

- Jiang X, Sobetzko P, Nasser W, Reverchon S, Muskhelishvili G. Chromosomal "stress-response" domains govern the spatiotemporal expression of the bacterial virulence program. mBio. 2015 Apr 28;6(3):e00353-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SantaLucia J, Jr. A unified view of polymer, dumbbell, and oligonucleotide DNA nearest-neighbor thermodynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Feb 17;95(4):1460-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

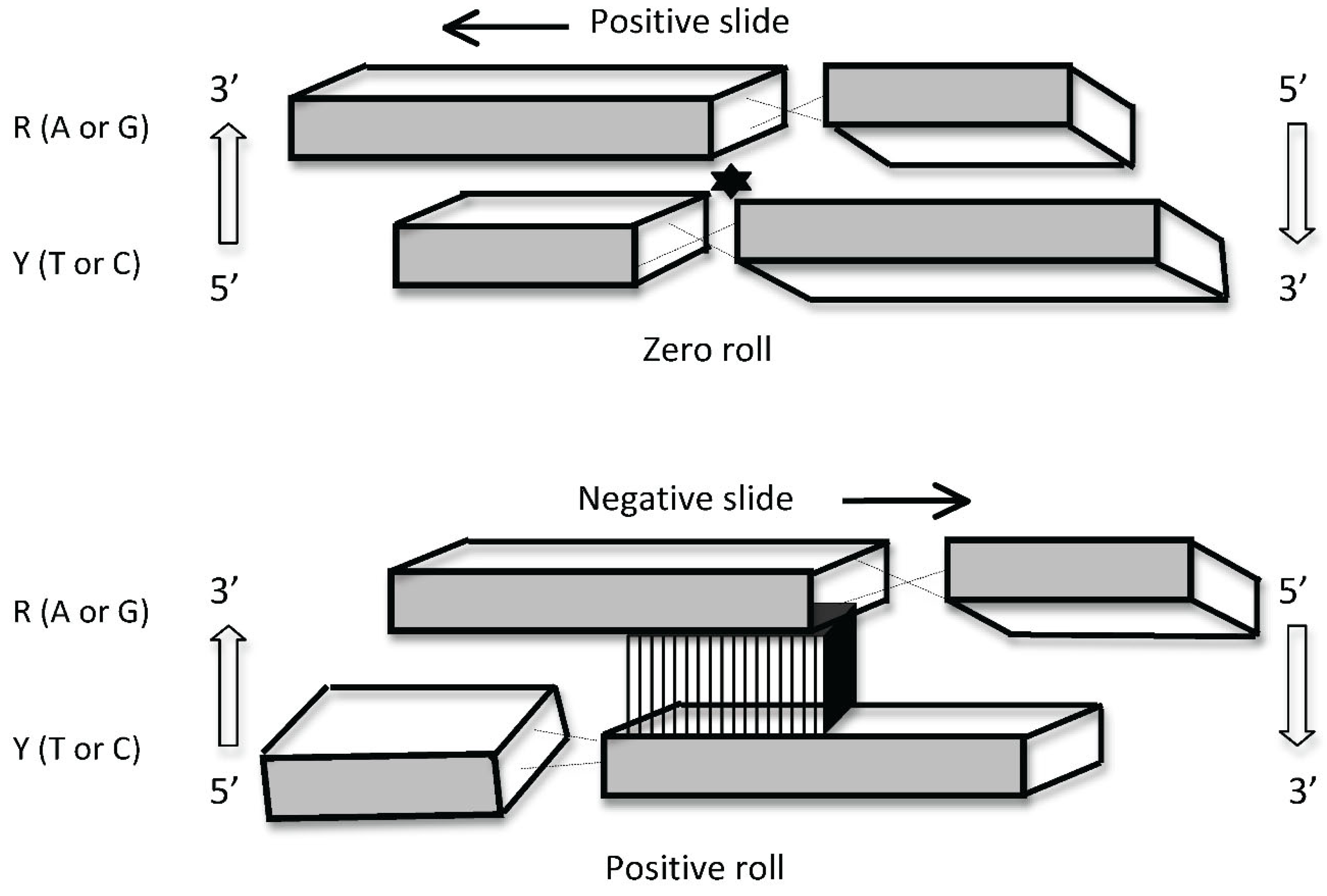

- Packer MJ, Dauncey MP, Hunter CA. Sequence-dependent DNA structure: dinucleotide conformational maps. J Mol Biol. 2000 Jan 7;295(1):71-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travers AA, Muskhelishvili G, Thompson JM. DNA information: from digital code to analogue structure. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2012 Jun 28;370(1969):2960-86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hassan MA, Calladine CR. The assessment of the geometry of dinucleotide steps in double-helical DNA; a new local calculation scheme. J Mol Biol. 1995 Sep 1;251(5):648-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calladine CR, Drew HR, Luisi BF, Travers A.A. Understanding DNA. The Molecule & How It Works. 2004, Third ed. ELSEVIER Academic Press.

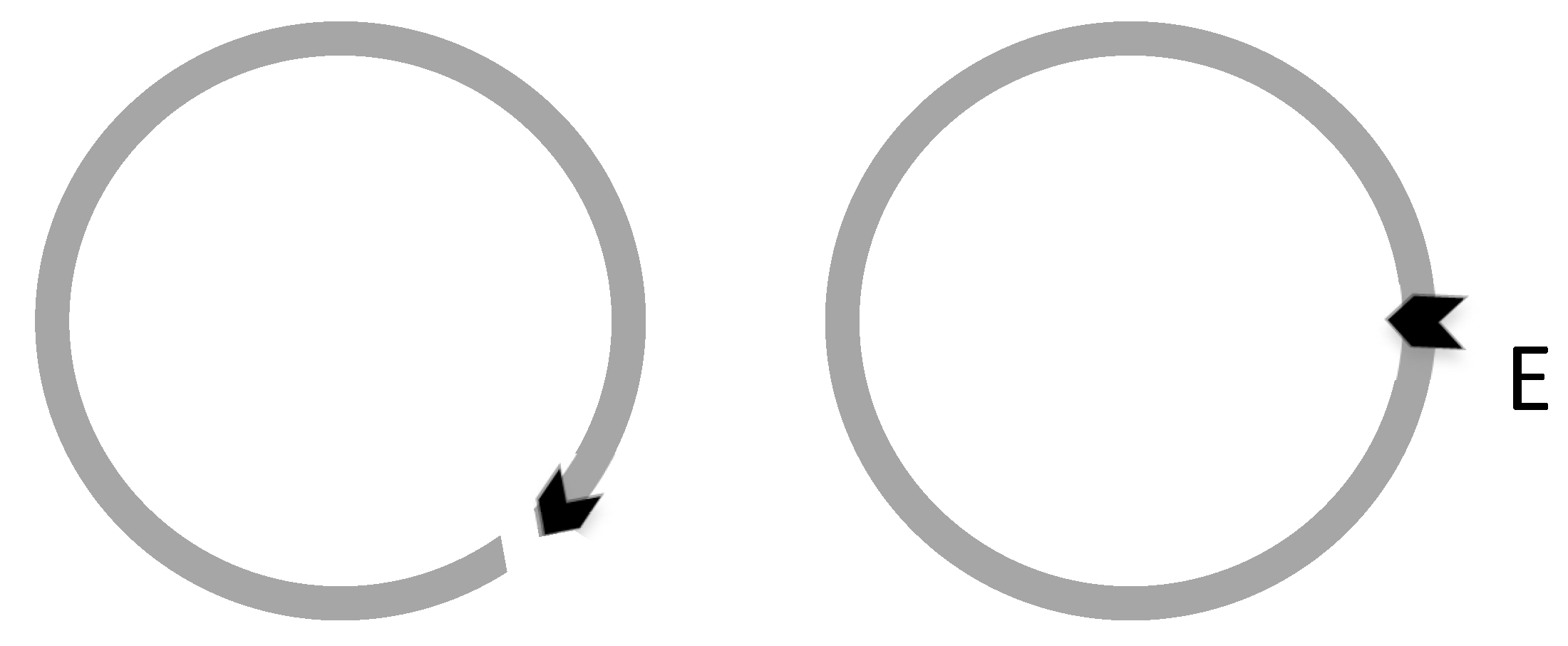

- Palecek, E. Local supercoil-stabilized DNA structures. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1991;26(2):151-226. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irobalieva RN, Fogg JM, Catanese DJ Jr, Sutthibutpong T, Chen M, Barker AK, Ludtke SJ, Harris SA, Schmid MF, Chiu W, Zechiedrich L. Structural diversity of supercoiled DNA. Nat Commun. 2015 Oct 12;6:8440. Erratum in: Nat Commun. 2015 Oct 29;6:8851. 10.1038/ncomms9851. Catanese, Daniel J [Corrected to Catanese, Daniel J Jr]. PMCID: PMC4608029. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Q, Irobalieva RN, Chiu W, Schmid MF, Fogg JM, Zechiedrich L, Pettitt BM. Influence of DNA sequence on the structure of minicircles under torsional stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 Jul 27;45(13):7633-7642. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyne ALB, Noy A, Main KHS, Velasco-Berrelleza V, Piperakis MM, Mitchenall LA, Cugliandolo FM, Beton JG, Stevenson CEM, Hoogenboom BW, Bates AD, Maxwell A, Harris SA. Base-pair resolution analysis of the effect of supercoiling on DNA flexibility and major groove recognition by triplex-forming oligonucleotides. Nat Commun. 2021 Feb 16;12(1):1053. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muskhelishvili G, Travers A. The regulatory role of DNA supercoiling in nucleoprotein complex assembly and genetic activity. Biophys Rev. 2016 Nov;8(Suppl 1):5-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh LS, Burger RM, Drlica K. Bacterial DNA supercoiling and [ATP]/[ADP]. Changes associated with a transition to anaerobic growth. J Mol Biol. 1991 Jun 5;219(3):443-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drlica, K. Control of bacterial DNA supercoiling. Mol Microbiol. 1992 Feb;6(4):425-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Workum M, van Dooren SJ, Oldenburg N, Molenaar D, Jensen PR, Snoep JL, Westerhoff HV. DNA supercoiling depends on the phosphorylation potential in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996 Apr;20(2):351-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snoep JL, van der Weijden CC, Andersen HW, Westerhoff HV, Jensen PR. DNA supercoiling in Escherichia coli is under tight and subtle homeostatic control, involving gene-expression and metabolic regulation of both topoisomerase I and DNA gyrase. Eur J Biochem. 2002 Mar;269(6):1662-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz SG, Solomon AK. Cation transport in Escherichia coli. I. Intracellular Na and K concentrations and net cation movement. J Gen Physiol. 1961 Nov;45(2):355-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hempfling WP, Höfer M, Harris EJ, Pressman BC. Correlation between changes in metabolite concentrations and rate of ion transport following glucose addition to Escherichia coli B. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1967 Jul 25;141(2):391-400. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson P, Bauer W. Supercoiling in closed circular DNA: dependence upon ion type and concentration. Biochemistry. 1978 Feb 21;17(4):594-601. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vologodskii AV, Cozzarelli NR. Conformational and thermodynamic properties of supercoiled DNA. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1994;23:609-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybenkov VV, Vologodskii AV, Cozzarelli NR. The effect of ionic conditions on DNA helical repeat, effective diameter and free energy of supercoiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997 Apr 1;25(7):1412-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu YC, Bremer H. Winding of the DNA helix by divalent metal ions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997 Oct 15;25(20):4067-71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusano S, Ding Q, Fujita N, Ishihama A. Promoter selectivity of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase E sigma 70 and E sigma 38 holoenzymes. Effect of DNA supercoiling. J Biol Chem. 1996 Jan 26;271(4):1998-2004. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider R, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G. FIS modulates growth phase-dependent topological transitions of DNA in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997 Nov;26(3):519-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordes P, Conter A, Morales V, Bouvier J, Kolb A, Gutierrez C. DNA supercoiling contributes to disconnect sigmaS accumulation from sigmaS-dependent transcription in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2003 Apr;48(2):561-71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulcrand, G. , Dages, S., Zhi, X. et al. DNA supercoiling, a critical signal regulating the basal expression of the lac operon in Escherichia coli. Sci Rep 6, 19243 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Gerganova V, Maurer S, Stoliar L, Japaridze A, Dietler G, Nasser W, Kutateladze T, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G. Upstream binding of idling RNA polymerase modulates transcription initiation from a nearby promoter. J Biol Chem. 2015 Mar 27;290(13):8095-109. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

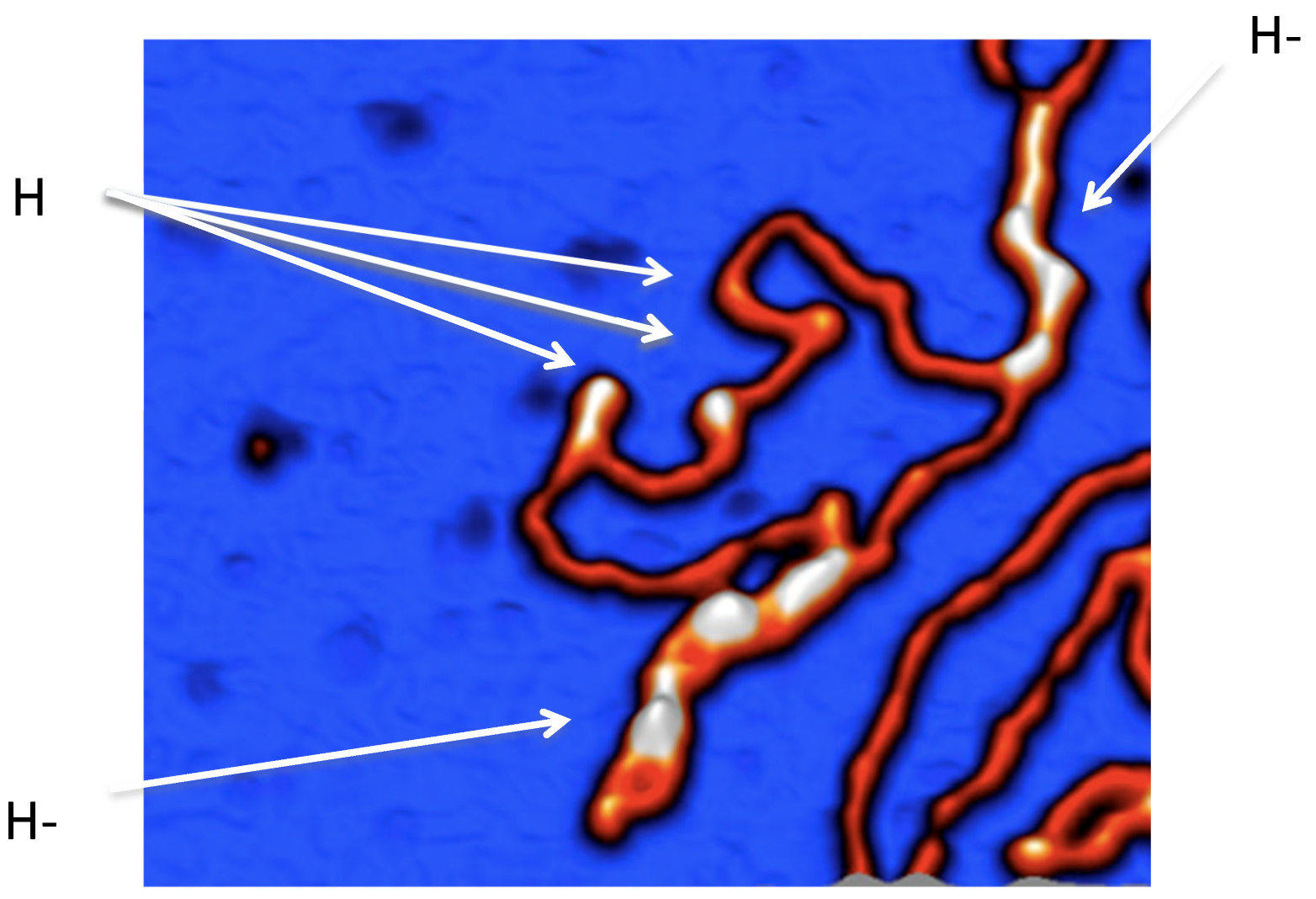

- Japaridze A, Muskhelishvili G, Benedetti F, Gavriilidou AF, Zenobi R, De Los Rios P, Longo G, Dietler G. Hyperplectonemes: A Higher Order Compact and Dynamic DNA Self-Organization. Nano Lett. 2017 Mar 8;17(3):1938-1948. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo MS, Haakonsen DL, Zeng W, Schumacher MA, Laub MT. A Bacterial Chromosome Structuring Protein Binds Overtwisted DNA to Stimulate Type II Topoisomerases and Enable DNA Replication. Cell. 2018 Oct 4;175(2):583-597.e23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarry MJ, Harmel C, Taylor JA, Marczynski GT, Schmeing TM. Structures of GapR reveal a central channel which could accommodate B-DNA. Sci Rep. 2019 Nov 13;9(1):16679. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang Q, Duan B, Qu Z, Fan S, Xia B. The DNA Recognition Motif of GapR Has an Intrinsic DNA Binding Preference towards AT-rich DNA. Molecules. 2021 Sep 24;26(19):5776. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu W, Yan Y, Artsimovitch I, Dunlap D, Finzi L. Positive supercoiling favors transcription elongation through lac repressor-mediated DNA loops. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Mar 21;50(5):2826-2835. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visser BJ, Sharma S, Chen PJ, McMullin AB, Bates ML, Bates D. Psoralen mapping reveals a bacterial genome supercoiling landscape dominated by transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 May 6;50(8):4436-4449. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider R, Lurz R, Lüder G, Tolksdorf C, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G. An architectural role of the Escherichia coli chromatin protein FIS in organising DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001 Dec 15;29(24):5107-14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo F, Adhya S. Spiral structure of Escherichia coli HUalphabeta provides foundation for DNA supercoiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Mar 13;104(11):4309-14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer S, Fritz J, Muskhelishvili G. A systematic in vitro study of nucleoprotein complexes formed by bacterial nucleoid-associated proteins revealing novel types of DNA organization. J Mol Biol. 2009 Apr 17;387(5):1261-76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dame RT, Kalmykowa OJ, Grainger DC. Chromosomal macrodomains and associated proteins: implications for DNA organization and replication in gram negative bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2011 Jun;7(6):e1002123. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma SC, Qian Z, Adhya SL. Architecture of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. PLoS Genet. 2019 Dec 12;15(12):e1008456. Erratum in: PLoS Genet. 2020 Oct 21;16(10):e1009148. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu LF, Wang JC. Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Oct;84(20):7024-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobetzko, P. Transcription-coupled DNA supercoiling dictates the chromosomal arrangement of bacterial genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 Feb 29;44(4):1514-24.

- doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw007.

- Dages S, Dages K, Zhi X, Leng F. Inhibition of the gyrA promoter by transcription-coupled DNA supercoiling in Escherichia coli. Sci Rep. 2018 Oct 3;8(1):14759. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Houdaigui B, Forquet R, Hindré T, Schneider D, Nasser W, Reverchon S, Meyer S. Bacterial genome architecture shapes global transcriptional regulation by DNA supercoiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019 Jun 20;47(11):5648-5657. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong KS, Ahn J, Khodursky AB. Spatial patterns of transcriptional activity in the chromosome of Escherichia coli. Genome Biol. 2004;5(11):R86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter BJ, Arsuaga J, Breier AM, Khodursky AB, Brown PO, Cozzarelli NR. Genomic transcriptional response to loss of chromosomal supercoiling in Escherichia coli. Genome Biol. 2004;5(11):R87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blot N, Mavathur R, Geertz M, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G. Homeostatic regulation of supercoiling sensitivity coordinates transcription of the bacterial genome. EMBO Rep. 2006 Jul;7(7):710-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrándiz MJ, Martín-Galiano AJ, Arnanz C, Camacho-Soguero I, Tirado-Vélez JM, de la Campa AG. An increase in negative supercoiling in bacteria reveals topology-reacting gene clusters and a homeostatic response mediated by the DNA topoisomerase I gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 Sep 6;44(15):7292-303. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behle A, Dietsch M, Goldschmidt L, Murugathas W, Berwanger LC, Burmester J, Yao L, Brandt D, Busche T, Kalinowski J, Hudson EP, Ebenhöh O, Axmann IM, Machné R. Manipulation of topoisomerase expression inhibits cell division but not growth and reveals a distinctive promoter structure in Synechocystis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Dec 9;50(22):12790-12808. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineau M, Martis B S, Forquet R, Baude J, Villard C, Grand L, Popowycz F, Soulère L, Hommais F, Nasser W, Reverchon S, Meyer S. What is a supercoiling-sensitive gene? Insights from topoisomerase I inhibition in the Gram-negative bacterium Dickeya dadantii. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Sep 9;50(16):9149-9161. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorman CJ, Ni Bhriain N, Higgins CF. DNA supercoiling and environmental regulation of virulence gene expression in Shigella flexneri. Nature. 1990 Apr 19;344(6268):789-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh LS, Rouviere-Yaniv J, Drlica K. Bacterial DNA supercoiling and [ATP]/[ADP] ratio: changes associated with salt shock. J Bacteriol. 1991 Jun;173(12):3914-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crozat E, Winkworth C, Gaffé J, Hallin PF, Riley MA, Lenski RE, Schneider D. Parallel genetic and phenotypic evolution of DNA superhelicity in experimental populations of Escherichia coli. Mol Biol Evol. 2010 Sep;27(9):2113-28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindré T, Knibbe C, Beslon G, Schneider D. New insights into bacterial adaptation through in vivo and in silico experimental evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012 Mar 27;10(5):352-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balke VL, Gralla JD. Changes in the linking number of supercoiled DNA accompany growth transitions in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987 Oct;169(10):4499-506. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger M, Farcas A, Geertz M, Zhelyazkova P, Brix K, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G. Coordination of genomic structure and transcription by the main bacterial nucleoid-associated protein HU. EMBO Rep. 2010 Jan;11(1):59-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

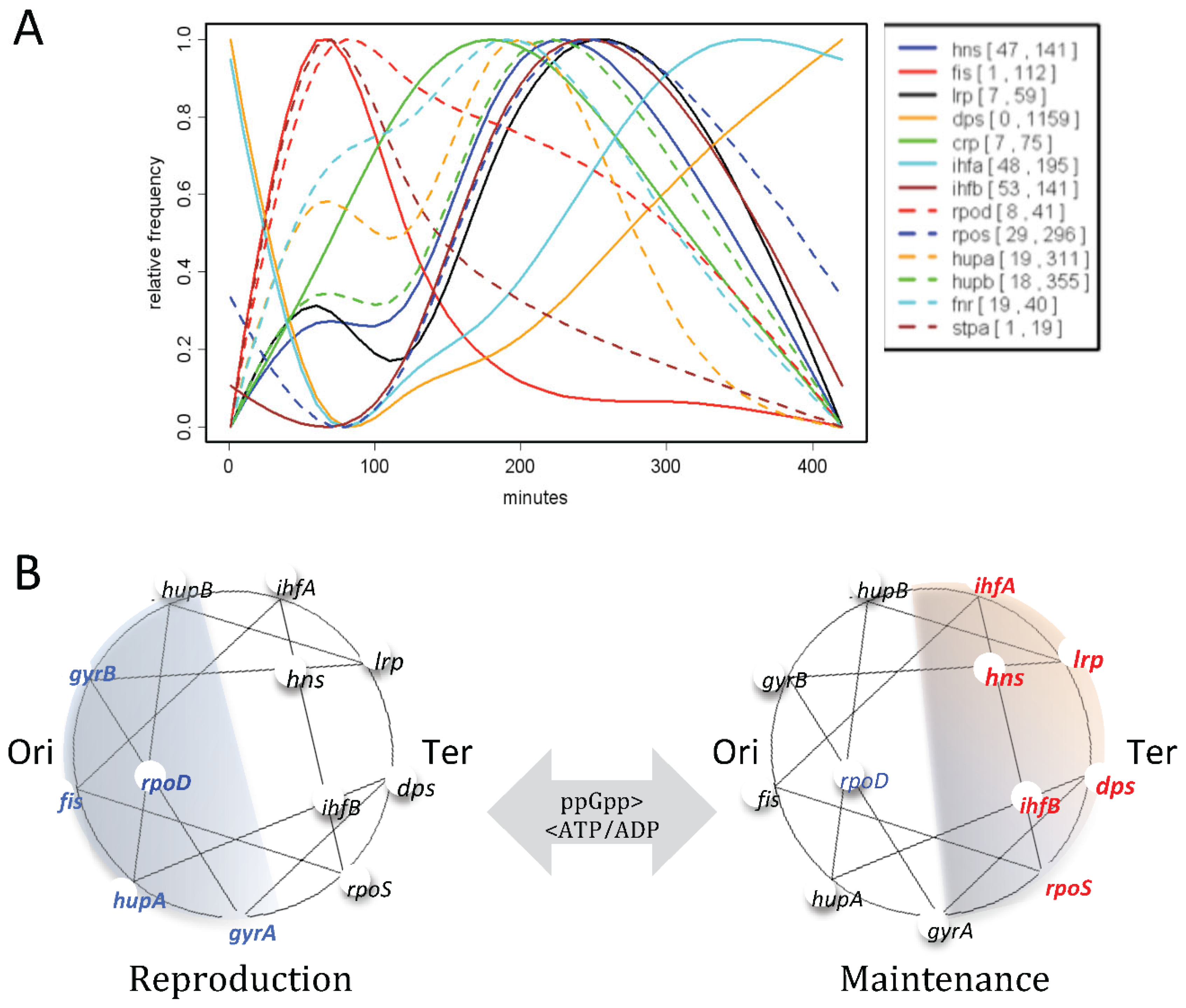

- Sobetzko P, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G. Gene order and chromosome dynamics coordinate spatiotemporal gene expression during the bacterial growth cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Jan 10;109(2):E42-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengge-Aronis, R. Stationary phase gene regulation: what makes an Escherichia coli promoter sigmaS-selective? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002 Dec;5(6):591-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klauck E, Typas A, Hengge R. The sigmaS subunit of RNA polymerase as a signal integrator and network master regulator in the general stress response in Escherichia coli. Sci Prog. 2007;90(Pt 2-3):103-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron ADS, Dillon SC, Kröger C, Beran L, Dorman CJ. Broad-scale redistribution of mRNA abundance and transcriptional machinery in response to growth rate in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microb Genom. 2017 Aug 4;3(10):e000127. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigatu D, Henkel W, Sobetzko P, Muskhelishvili G. Relationship between digital information and thermodynamic stability in bacterial genomes. EURASIP J Bioinform Syst Biol. 2016 Feb 2;2016(1):4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer S, Reverchon S, Nasser W, Muskhelishvili G. Chromosomal organization of transcription: in a nutshell. Curr Genet. 2018 Jun;64(3):555-565. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muskhelishvili G, Sobetzko P, Geertz M, Berger M. General organisational principles of the transcriptional regulation system: a tree or a circle? Mol Biosyst. 2010 Apr;6(4):662-76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa C, de Lorenzo V, Cebolla A. Modulation of gene expression through chromosomal positioning in Escherichia coli. Microbiology (Reading). 1997 Jun;143 ( Pt 6):2071-2078. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teufel M, Henkel W, Sobetzko P. The role of replication-induced chromosomal copy numbers in spatio-temporal gene regulation and evolutionary chromosome plasticity. Front Microbiol. 2023 Apr 20;14:1119878. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pountain AW, Jiang P, Yao T, Homaee E, Guan Y, McDonald KJC, Podkowik M, Shopsin B, Torres VJ, Golding I, Yanai I. Transcription-replication interactions reveal bacterial genome regulation. Nature. 2024 Feb;626(7999):661-669. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang B, Blot N, Bouffartigues E, Buckle M, Geertz M, Gualerzi CO, Mavathur R, Muskhelishvili G, Pon CL, Rimsky S, Stella S, Babu MM, Travers A. High-affinity DNA binding sites for H-NS provide a molecular basis for selective silencing within proteobacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(18):6330-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero Llopis P, Jackson AF, Sliusarenko O, Surovtsev I, Heinritz J, Emonet T, Jacobs-Wagner C. Spatial organization of the flow of genetic information in bacteria. Nature. 2010 Jul 1;466(7302):77-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlman TE, Cox EC. Gene location and DNA density determine transcription factor distributions in Escherichia coli. Mol Syst Biol. 2012;8:610. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antipov SS, Tutukina MN, Preobrazhenskaya EV, Kondrashov FA, Patrushev MV, Toshchakov SV, Dominova I, Shvyreva US, Vrublevskaya VV, Morenkov OS, Sukharicheva NA, Panyukov VV, Ozoline ON. The nucleoid protein Dps binds genomic DNA of Escherichia coli in a non-random manner. PLoS One. 2017 Aug 11;12(8):e0182800. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reverchon S, Meyer S, Forquet R, Hommais F, Muskhelishvili G, Nasser W. The nucleoid-associated protein IHF acts as a 'transcriptional domainin' protein coordinating the bacterial virulence traits with global transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021 Jan 25;49(2):776-790. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy CD, Cozzarelli NR. A genetic selection for supercoiling mutants of Escherichia coli reveals proteins implicated in chromosome structure. Mol Microbiol. 2005 Sep;57(6):1636-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Galiano AJ, Ferrándiz MJ, de la Campa AG. Bridging Chromosomal Architecture and Pathophysiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Genome Biol Evol. 2017 Feb 1;9(2):350-361. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan Y, Xu W, Kumar S, Zhang A, Leng F, Dunlap D, Finzi L. Negative DNA supercoiling makes protein-mediated looping deterministic and ergodic within the bacterial doubling time. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021 Nov 18;49(20):11550-11559. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortassa S, Aon MA. Altered topoisomerase activities may be involved in the regulation of DNA supercoiling in aerobic-anaerobic transitions in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993 Sep 22;126(2):115-24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaén KE, Sigala JC, Olivares-Hernández R, Niehaus K, Lara AR. Heterogeneous oxygen availability affects the titer and topology but not the fidelity of plasmid DNA produced by Escherichia coli. BMC Biotechnol. 2017 Jul 4;17(1):60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexeeva S, Hellingwerf KJ, Teixeira de Mattos MJ (2003) Requirement of ArcA for redox regulation in Escherichia coli under microaerobic but not anaerobic or aerobic conditions. J Bacteriol 185:204–209.

- Levanon SS, San KY, Bennett GN (2005) Effect of oxygen on the Escherichia coli ArcA and FNR regulation systems and metabolic responses. Biotechnol Bioeng 89:556–564.

- Mika F, Hengge R (2005) A two-component phosphotransfer network involving ArcB, ArcA, and RssB coordinates synthesis and proteolysis of sigmaS (RpoS) in E. coli. Genes Dev 19:2770–2781.

- Muskhelishvili G, Sobetzko P, Mehandziska S, Travers A. Composition of Transcription Machinery and Its Crosstalk with Nucleoid-Associated Proteins and Global Transcription Factors. Biomolecules. 2021 Jun 22;11(7):924. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowiec JA, Gralla JD. All three elements of the lac ps promoter mediate its transcriptional response to DNA supercoiling. J Mol Biol. 1987 May 5;195(1):89-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auner H, Buckle M, Deufel A, Kutateladze T, Lazarus L, Mavathur R, Muskhelishvili G, Pemberton I, Schneider R, Travers A. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by FIS: role of core promoter structure and DNA topology. J Mol Biol. 2003 Aug 8;331(2):331-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travers A, Muskhelishvili G. DNA supercoiling - a global transcriptional regulator for enterobacterial growth? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005 Feb;3(2):157-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forquet R, Pineau M, Nasser W, Reverchon S, Meyer S. Role of the Discriminator Sequence in the Supercoiling Sensitivity of Bacterial Promoters. mSystems. 2021 Aug 31;6(4):e0097821. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forquet R, Nasser W, Reverchon S, Meyer S. Quantitative contribution of the spacer length in the supercoiling-sensitivity of bacterial promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Jul 22;50(13):7287-7297. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein CA, Teufel M, Weile CJ, Sobetzko P. The bacterial promoter spacer modulates promoter strength and timing by length, TG-motifs and DNA supercoiling sensitivity. Sci Rep. 2021 Dec 22;11(1):24399. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochman M, Aviv M, Glaser G, Muskhelishvili G. Promoter protection by a transcription factor acting as a local topological homeostat. EMBO Rep. 2002 Apr;3(4):355-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares-Zavaleta N, Jáuregui R, Merino E. Genome analysis of Escherichia coli promoter sequences evidences that DNA static curvature plays a more important role in gene transcription than has previously been anticipated. Genomics. 2006 Mar;87(3):329-37. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balas D, Fernández-Moreira E, De La Campa AG. Molecular characterization of the gene encoding the DNA gyrase A subunit of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1998 Jun;180(11):2854-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirvonen CA, Ross W, Wozniak CE, Marasco E, Anthony JR, Aiyar SE, Newburn VH, Gourse RL. Contributions of UP elements and the transcription factor FIS to expression from the seven rrn P1 promoters in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2001 Nov;183(21):6305-14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayan V, Zuzow R, O'Shea EK. Oscillations in supercoiling drive circadian gene expression in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Dec 29;106(52):22564-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muskhelishvili G, Forquet R, Reverchon S, Meyer S, Nasser W. Coherent Domains of Transcription Coordinate Gene Expression During Bacterial Growth and Adaptation. Microorganisms. 2019 Dec 13;7(12):694. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le TB, Imakaev MV, Mirny LA, Laub MT. High-resolution mapping of the spatial organization of a bacterial chromosome. Science. 2013 Nov 8;342(6159):731-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le TB, Laub MT. Transcription rate and transcript length drive formation of chromosomal interaction domain boundaries. EMBO J. 2016 Jul 15;35(14):1582-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booker BM, Deng S, Higgins NP. DNA topology of highly transcribed operons in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2010 Dec;78(6):1348-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito D, Kawamura H, Oikawa A, Ihara Y, Shibata T, Nakamura N, Asano T, Kawabata SI, Suzuki T, Masuda S. ppGpp functions as an alarmone in metazoa. Commun Biol. 2020 Nov 13;3(1):671. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potrykus K, Cashel M. (p)ppGpp: still magical? Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:35-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez D, Collier J. Effects of (p)ppGpp on the progression of the cell cycle of Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 2014 Jul;196(14):2514-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer JA, Sanderlin AG, Laub MT. The Stringent Response Inhibits DNA Replication Initiation in E. coli by Modulating Supercoiling of oriC. mBio. 2019 Jul 2;10(4):e01330-19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashel, M. Inhibition of RNA polymerase by ppGpp, a nucleotide accumulated during the stringent response to aminoacid starvation in E. coli. (1970) Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 35, 407–413.

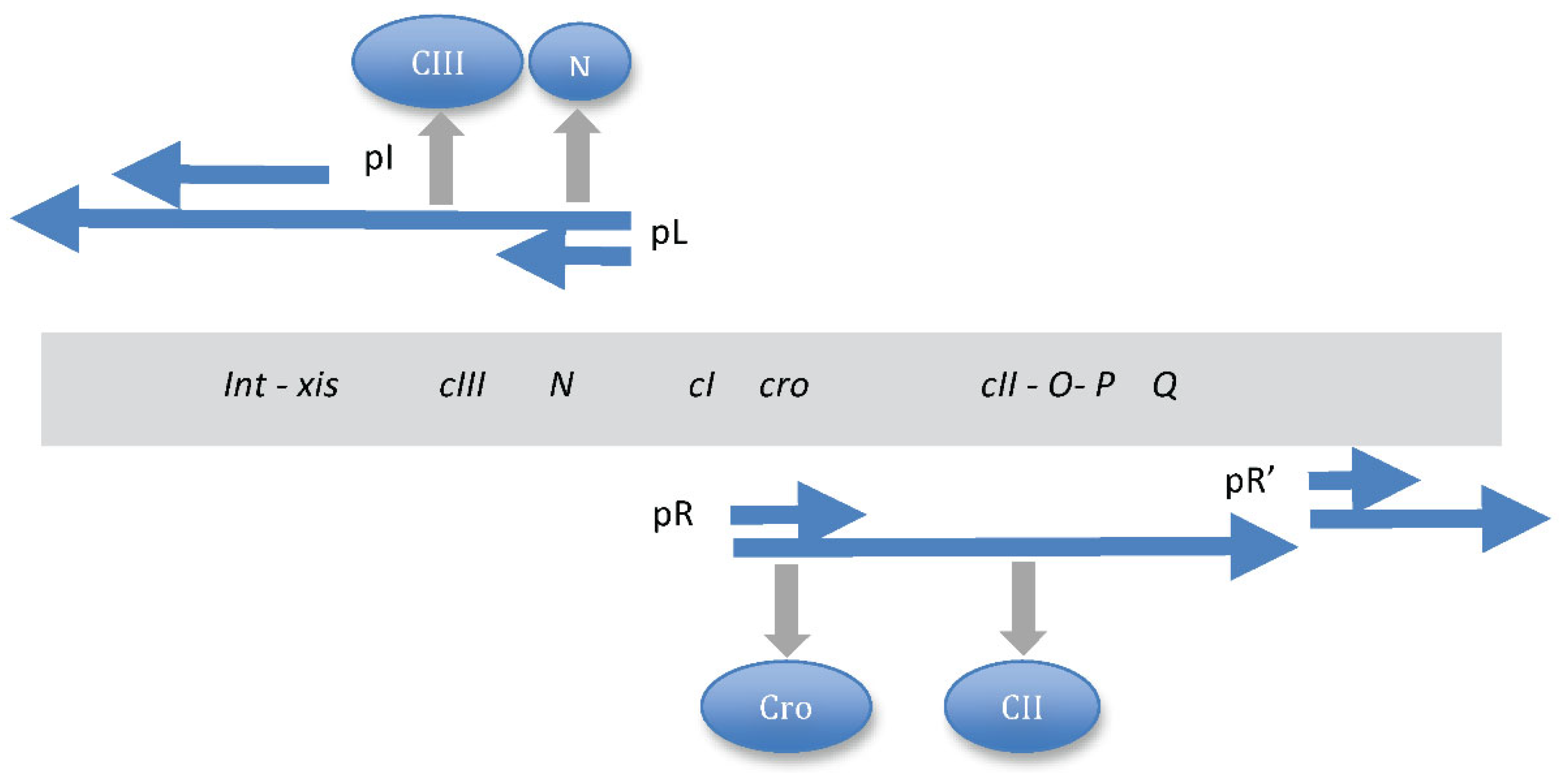

- Ptashne M (1992) A Genetic Switch - 2nd ed. Blackwell Scientific Publications & Cell Press.

- Laganenka L, Sander T, Lagonenko A, Chen Y, Link H, Sourjik V.2019.Quorum Sensing and Metabolic State of the Host Control Lysogeny-Lysis Switch of Bacteriophage T1. mBio10:10.1128/mbio.01884-19. [CrossRef]

- Norregaard K, Andersson M, Sneppen K, Nielsen PE, Brown S, Oddershede LB. Effect of supercoiling on the λ switch. Bacteriophage. 2014 Jan 1;4(1):e27517. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding Y, Manzo C, Fulcrand G, Leng F, Dunlap D, Finzi L. DNA supercoiling: a regulatory signal for the λ repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Oct 28;111(43):15402-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahramanoglou C, Prieto AI, Khedkar S, Haase B, Gupta A, Benes V, Fraser GM, Luscombe NM, Seshasayee AS. Genomics of DNA cytosine methylation in Escherichia coli reveals its role in stationary phase transcription. Nat Commun. 2012 Jun 6;3:886. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahramanoglou C, Seshasayee AS, Prieto AI, Ibberson D, Schmidt S, ZimmermannJ, Benes V, Fraser GM, Luscombe NM. Direct and indirect effects of H-NS and Fison global gene expression control in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011Mar;39(6):2073-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto AI, Kahramanoglou C, Ali RM, Fraser GM, Seshasayee AS, Luscombe NM. Genomic analysis of DNA binding and gene regulation by homologous nucleoid-associated proteins IHF and HU in Escherichia coli K12. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Apr;40(8):3524-37. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japaridze A, Yang W, Dekker C, Nasser W, Muskhelishvili G. DNA sequence-directed cooperation between nucleoid-associated proteins. iScience. 2021 Apr 20;24(5):102408. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hommais F, Krin E, Laurent-Winter C, Soutourina O, Malpertuy A, Le Caer JP, Danchin A, Bertin P. Large-scale monitoring of pleiotropic regulation of gene expression by the prokaryotic nucleoid-associated protein, H-NS. Mol Microbiol. 2001 Apr;40(1):20-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger M, Gerganova V, Berger P, Rapiteanu R, Lisicovas V, Dobrindt U. Genes on a Wire: The Nucleoid-Associated Protein HU Insulates Transcription Units in Escherichia coli. Sci Rep. 2016 Aug 22;6:31512. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid FM, Dame RT. 2024: A "nucleoid space" odyssey featuring H-NS. Bioessays. 2024 Sep 26:e2400098. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

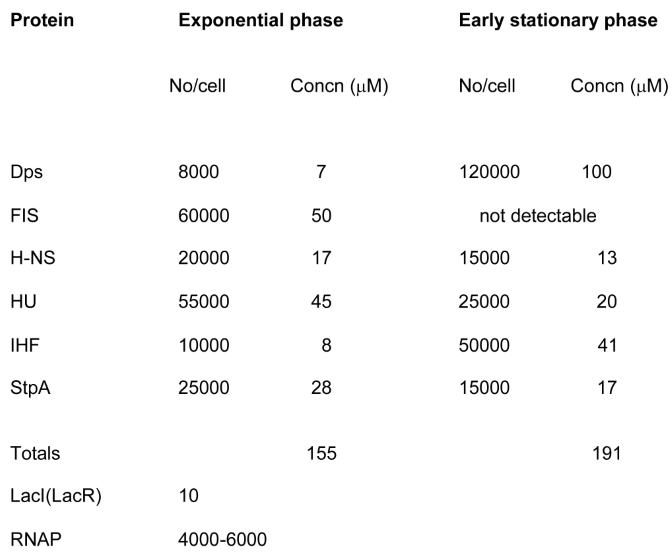

- Ali Azam T, Iwata A, Nishimura A, Ueda S, Ishihama A. Growth phase-dependent variation in protein composition of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. J Bacteriol. 1999 Oct;181(20):6361-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway C, Beckett MC, Dorman CJ. The DNA relaxation-dependent OFF-to-ON biasing of the type 1 fimbrial genetic switch requires the Fis nucleoid-associated protein. Microbiology (Reading). 2023 Jan;169(1):001283. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

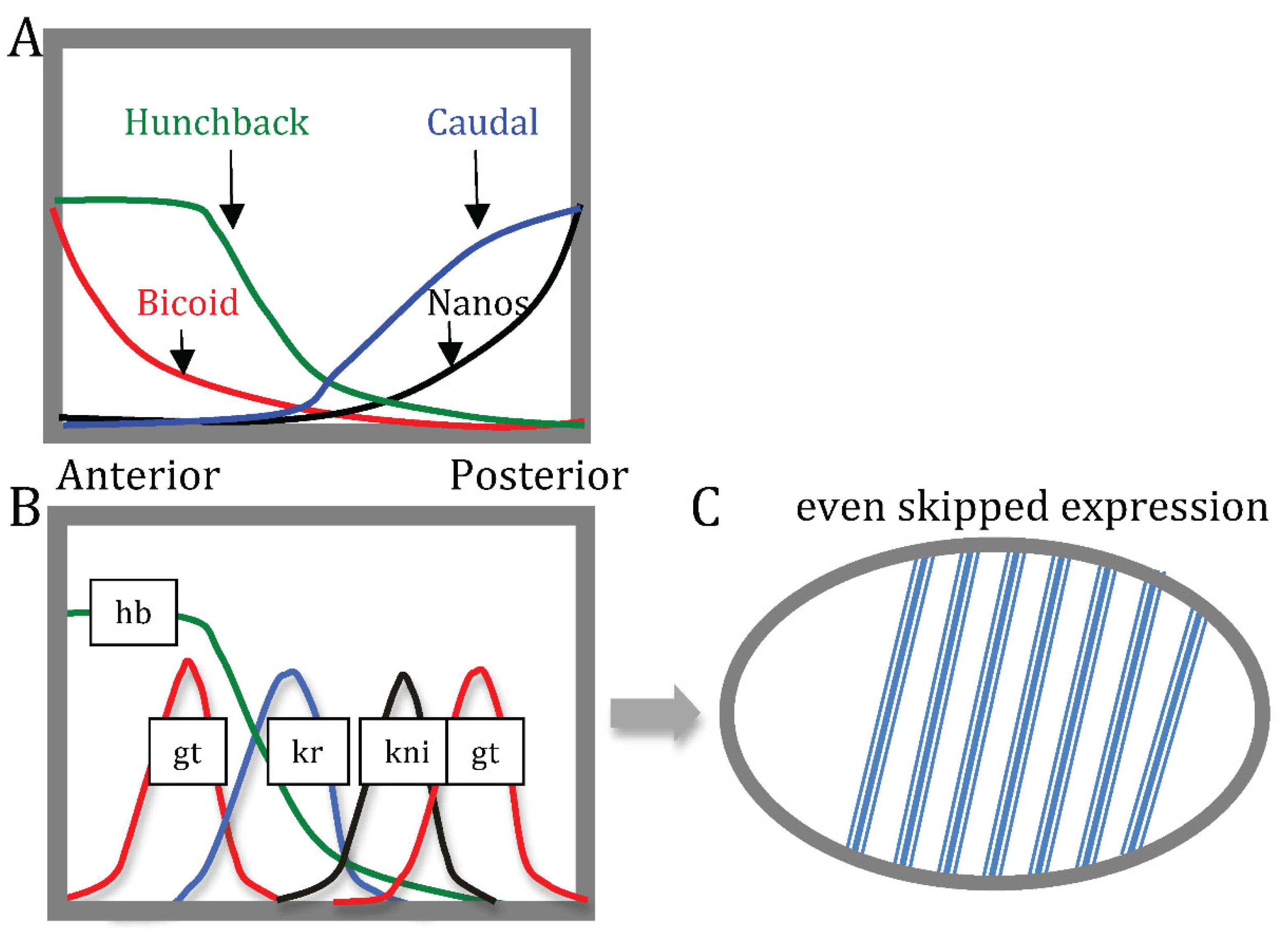

- Fujioka M, Jaynes JB, Goto T. Early even-skipped stripes act as morphogenetic gradients at the single cell level to establish engrailed expression. Development. 1995 Dec;121(12):4371-82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura Y, Tomonari S, Kawamoto K, Yamashita T, Watanabe T, Ishimaru Y, Noji S, Mito T. Evolutionarily conserved function of the even-skipped ortholog in insects revealed by gene knock-out analyses in Gryllus bimaculatus. Dev Biol. 2022 May;485:1-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnenschein N, Geertz M, Muskhelishvili G, Hütt MT. Analog regulation of metabolic demand. BMC Syst Biol. 2011 Mar 15;5:40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Mojica JE, Enders L, Walsh J, Lau KH, Lempradl A. Continuous transcriptome analysis reveals novel patterns of early gene expression in Drosophila embryos. Cell Genom. 2023 Feb 15;3(3):100265. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemkow MJ, Dichter J, Arndt-Jovin DJ. Developmental regulation of DNA-topoisomerases during Drosophila embryogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2001 Jan 15;262(2):114-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marr, AG. Growth rate of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1991 Jun;55(2):316-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama T, Mirth CK. Unravelling the diversity of mechanisms through which nutrition regulates body size in insects. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2018 Feb;25:1-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshkin YM, Chalkley GE, Kan TW, Reddy BA, Ozgur Z, van Ijcken WF, Dekkers DH, Demmers JA, Travers AA, Verrijzer CP. Remodelers organize cellular chromatin by counteracting intrinsic histone-DNA sequence preferences in a class-specific manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2012 Feb;32(3):675-88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosmidis K, Hütt MT. The E. coli transcriptional regulatory network and its spatial embedding. Eur Phys J E Soft Matter. 2019 Mar 20;42(3):30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosmidis K, Jablonski KP, Muskhelishvili G, Hütt MT. Chromosomal origin of replication coordinates logically distinct types of bacterial genetic regulation. NPJ Syst Biol Appl. 2020 Feb 17;6(1):5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci DP, Melfi MD, Lasker K, Dill DL, McAdams HH, Shapiro L. Cell cycle progression in Caulobacter requires a nucleoid-associated protein with high AT sequence recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Oct 4;113(40):E5952-E5961. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondi EG, Reisinger SJ, Skerker JM, Arif M, Perchuk BS, Ryan KR, Laub MT. 2006. Regulation of the bacterial cell cycle by an integrated genetic circuit. Nature 444:899–904. [CrossRef]

- Laub MT, Shapiro L, McAdams HH. 2007. Systems biology of Caulobacter. Annu Rev Genet 41:429–441. [CrossRef]

- Sobetzko, P.; Glinkowska, M.; Muskhelishvili, G.; GSE65244: Temporal Gene Expression in Escherichia coli. Gene Expression Omnibus. 2017. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE65244 (accessed on 20 June 2021).

| Base steps | kcal/mol |

|---|---|

| AA/TT | -1.02 |

| AT/AT | -0.73 |

| TA/TA | -0.6 |

| CA/TG | -1.38 |

| GT/AC | -1.43 |

| CT/AG | -1.16 |

| GA/CT | -1.46 |

| CG/CG | -2.09 |

| GC/GC | -2.28 |

| GG/CC | -1.77 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).