1. Introduction

Robot Operating System (ROS, aka ROS1) emerged in 2009 and has been evolving as the de facto standard ecosystem for developing robotics applications, including mobile robots, robotic arms [

1], unmanned aerial systems and drones [

2], self-driving cars [

3], quadruped robots [

4], space robots [

5], and much more. ROS provides easy access to several open-source libraries, making developing robotic systems and applications faster. For example, open-source libraries like gmapping from OpenSLAM [

4] and cartographer from Google [

6] are integrated into ROS to provide a full-fledged navigation system for building maps and navigation. The OpenCV library [

7] for image processing and the Point Cloud library [

8] for point cloud processing are supported by ROS for advanced computer vision applications. ROS also provides high-level abstractions to low-level hardware drivers, simplifying the burden of low-level programming. ROS allowed robotics application designers and developers to focus on their scope of work rather than being distracted by marginal side details. These are just samples of ROS features that turned it into the most popular robotic framework.

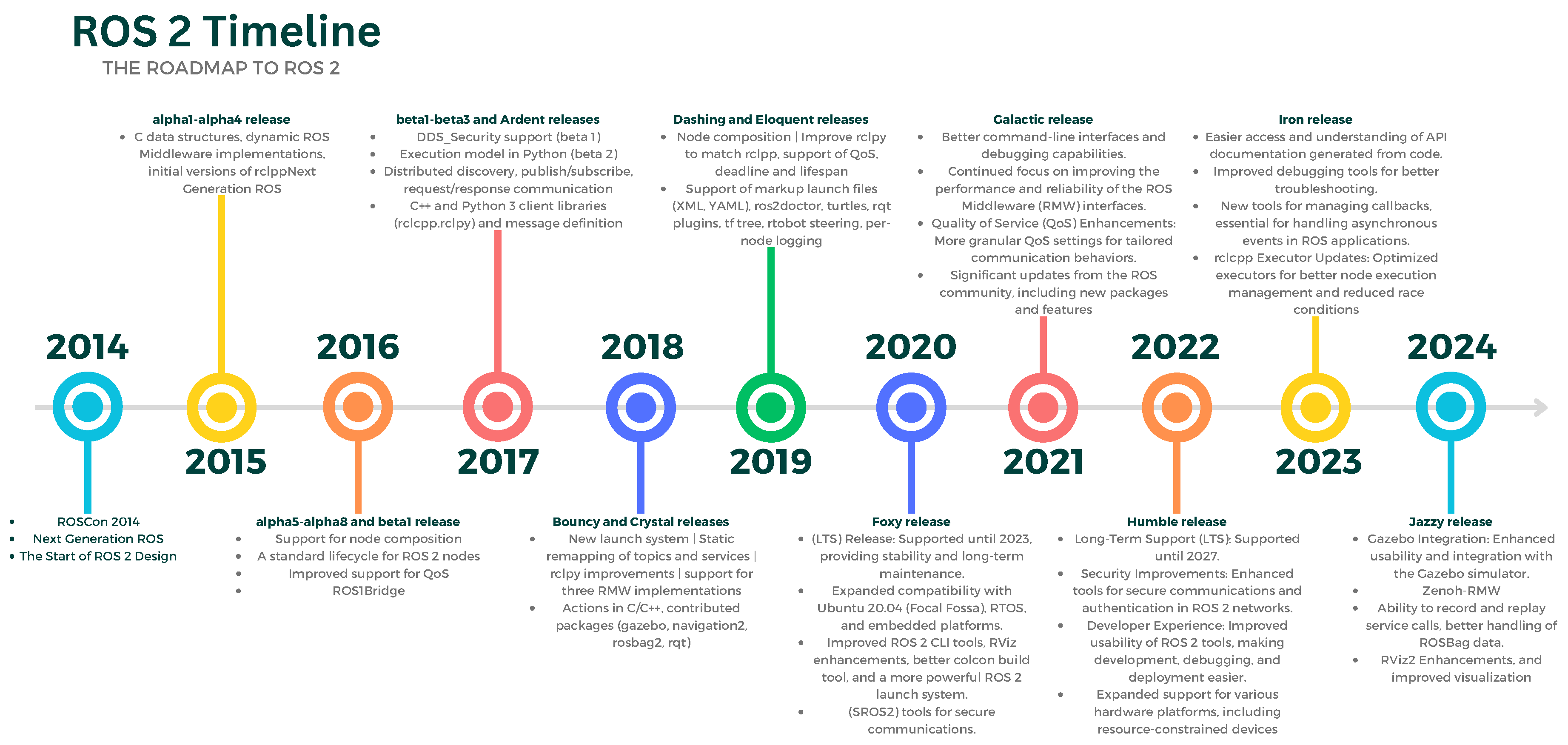

However, at ROSCon 2014 conference, the Open Source Robotics Foundations (OSRF) and the ROS community started to discuss and identify some gaps in ROS, including (a) single point of failure with the ROS Master Node, which also limits its scalability (b) nonsupport of multi-robots systems as ROS was designed for a single robot usage, (c) and the lack of support for real-time guarantee or quality of service profiles, and thus its reliability was questionable.

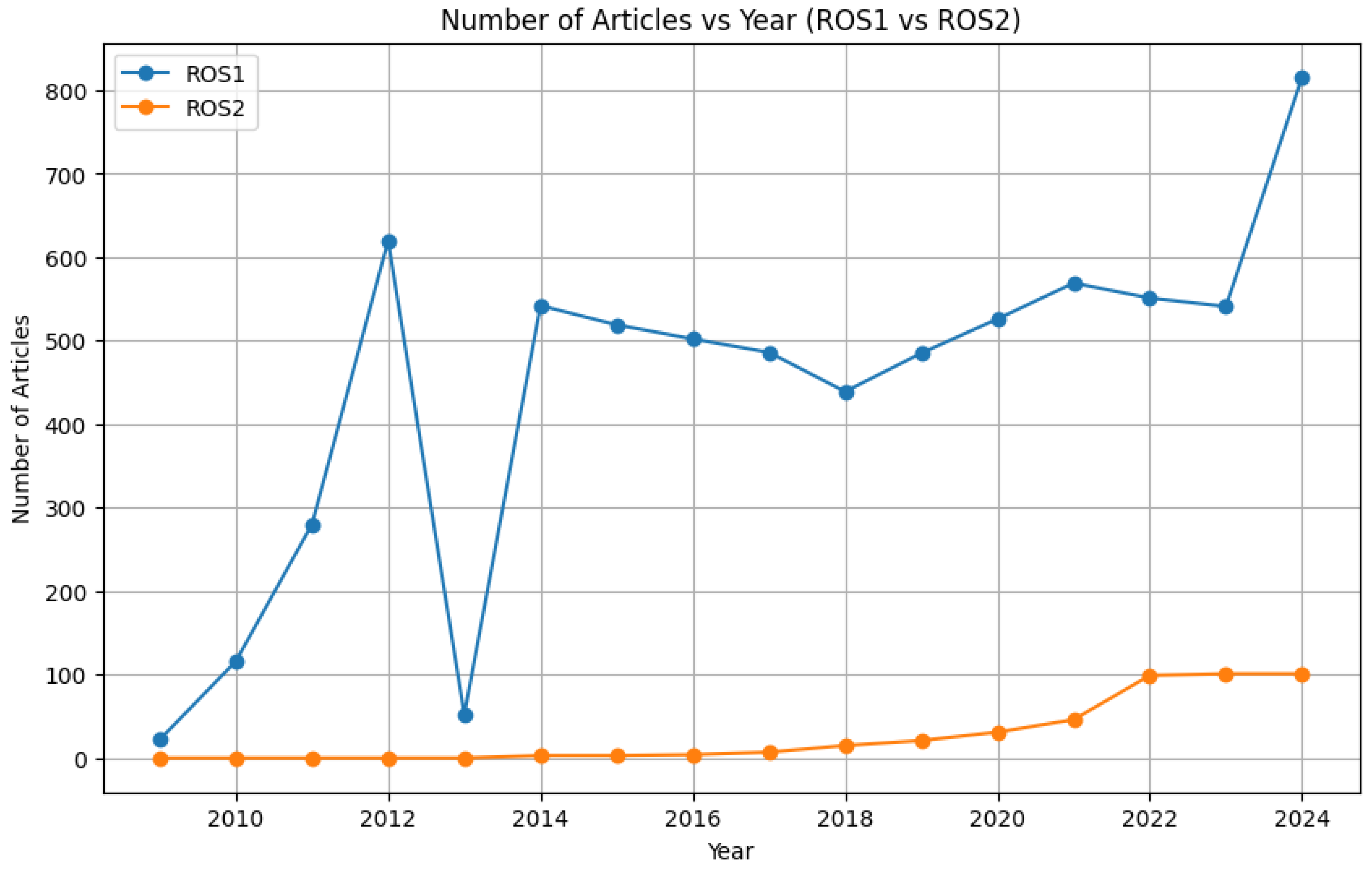

The ROS community has formed several working groups to design and develop the next-generation version of ROS, which is currently called ROS 2. Alpha and Beta versions started showing up from August 2015 until September 2017, and the first official ROS 2 release, Ardent Apalone, was launched on December 8th, 2017. Despite the release of ROS 2, ROS was still being used more actively than ROS 2 until 2023, and the main reason is that ROS 2 has been under continuous development and has yet to reach the same level of maturity as ROS. In fact, the ROS 2 developers created the ROS Bridge package to communicate between ROS and ROS 2 when ROS is needed from missing functionalities in ROS 2.

However, things have changed since late 2021, when ROS 2 has accomplished most of the missing functionalities, including navigation, transformations, and others. It is expected that ROS 2 will completely dominate ROS after the EOL of the last ROS distribution (ROS Noetic).

Figure 1 shows the road map to ROS 2 until the Jazzy distribution release.

1.1. Methodology

The methodology for obtaining and analyzing the literature on ROS 2 involved a comprehensive search across multiple databases including Google Scholar, IEEE, ACM, ScienceDirect, Springer, Elsevier, SAGE, and arXiv. From these sources, we collected a total of 7497 articles related to ROS 1 and ROS 2, dating from 2009 to the present. All these articles are recorded in our online database

https://www.ros.riotu-lab.org/, where each entry includes information about which version of ROS it addresses or utilizes, the research field, the robotic platform used, the article DOI, and its GitHub repository if available. This database allows users to filter and sort the records to find specific information, such as all GitHub ROS 2 repositories for UAV swarms.

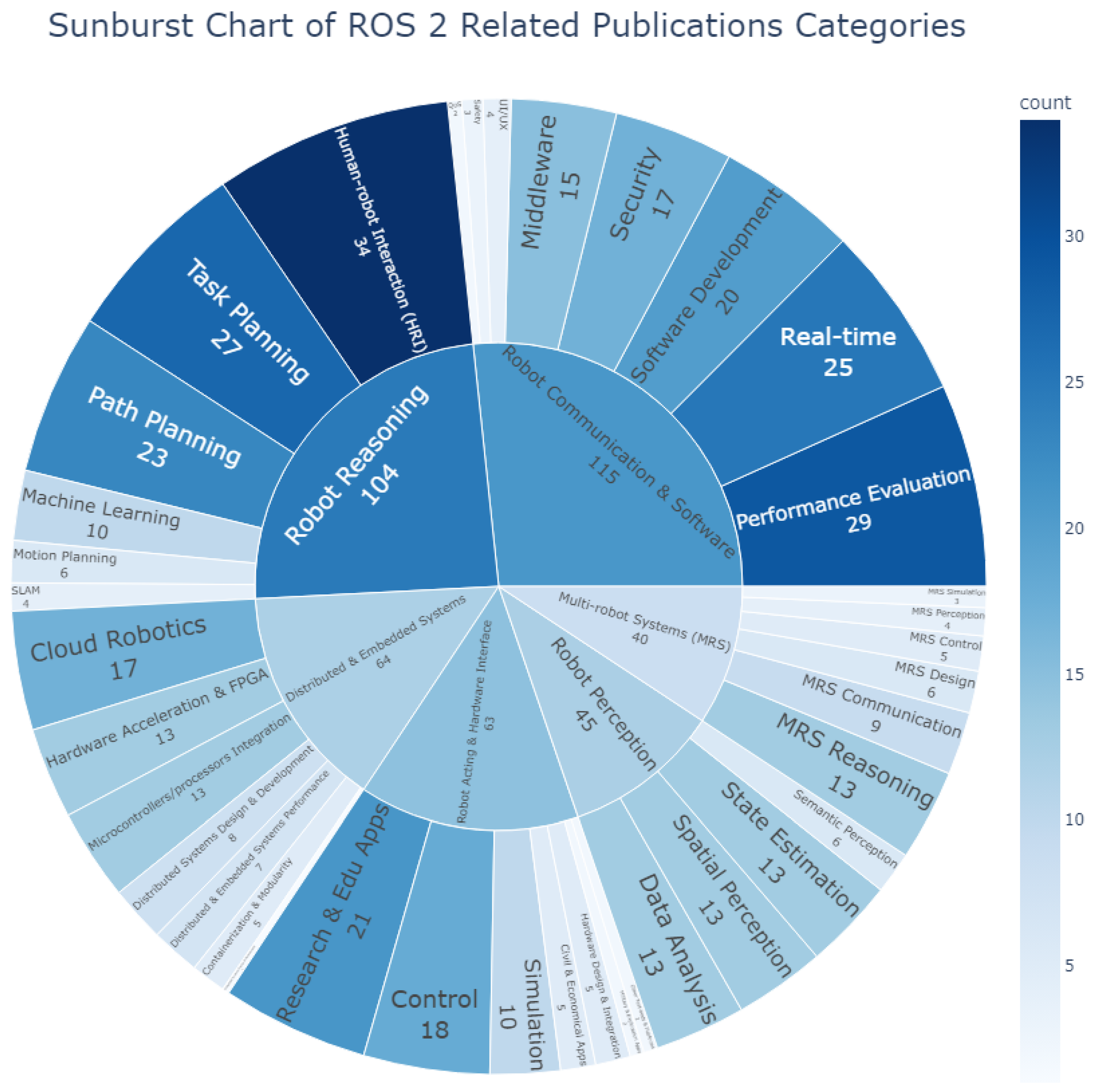

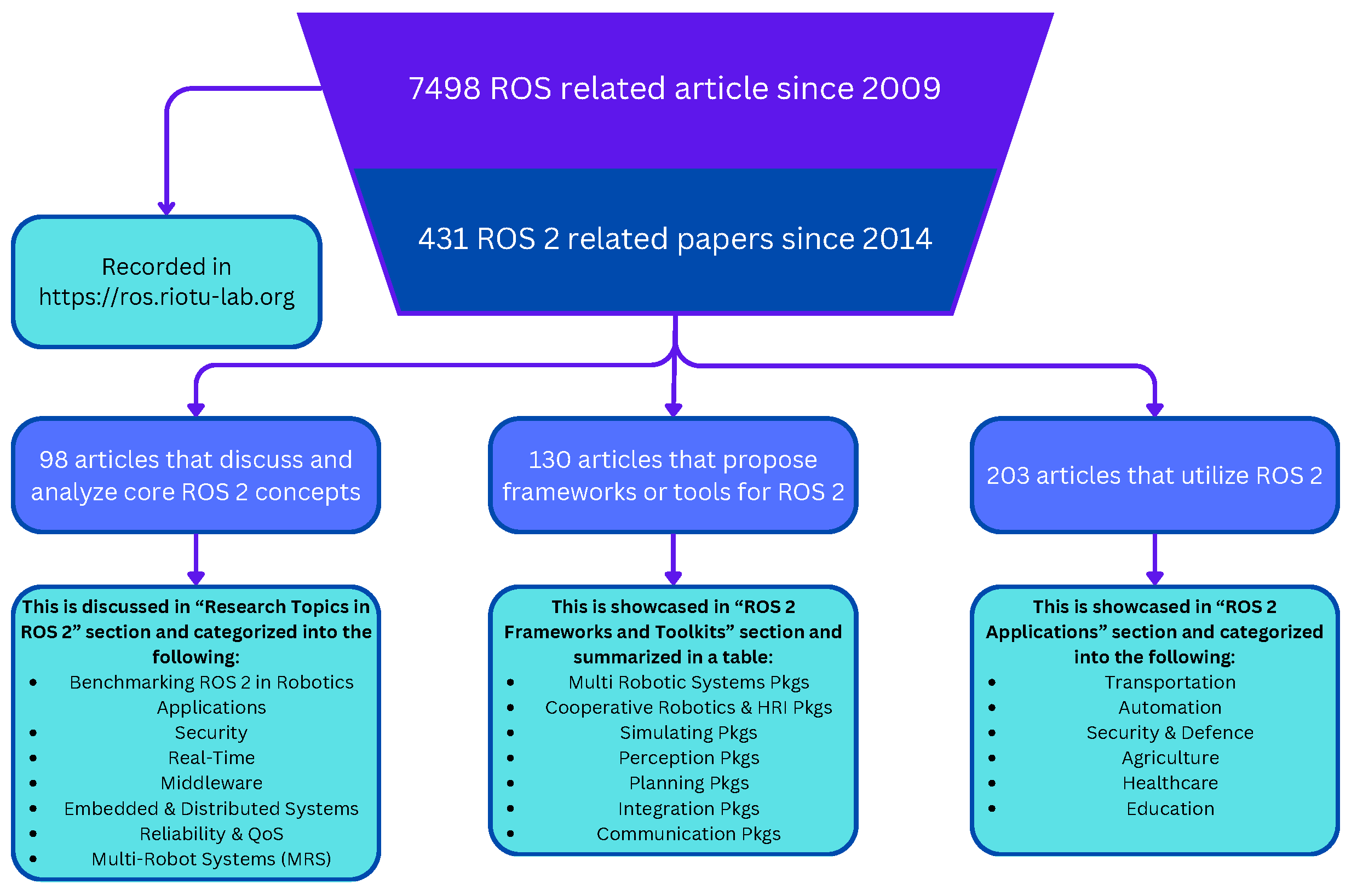

From the initial collection, we identified 431 articles specifically focused on ROS 2. These articles were further categorized into three groups as shown in

Figure 2, and they are explained as follows:

Articles that analyze ROS 2: This group includes 98 articles that discuss various areas that are core to ROS 2 design, such as Security, Real-Time Capabilities, Communication, and Multi-robot Systems support. Each research area is explored in depth, providing critical insights into the literature, motivations for the researchers, their contributions, and current gaps in

Section 4.

Articles that propose tool-kits for ROS 2: This group comprises 130 articles. These research works provide open-source software packages for ROS 2 users for different applications such as ROSGPT[

9] for HRI, or CrazyChoir[

10] for UAV in MRS settings. We cite some of these articles with their GitHub repositories in a table in

Section 5. This highlights the significant frameworks and tools developed by the community to support ROS 2.

Articles that utilize ROS 2: This group includes 203 research works that use ROS 2 as a middleware to facilitate their development such as the use of ROS 2 in healthcare research [

11]. We provide a taxonomy for these works. We mention some of these articles to showcase the diverse fields and applications that utilize ROS 2 in

Section 6, demonstrating its broad applicability and impact.

The detailed methodology for literature collection and categorization is illustrated in

Figure 3, which outlines the process from initial database searches to the final categorization of articles. This approach ensures a comprehensive and systematic review of the ROS 2 literature, providing valuable insights and resources for researchers and developers in the field.

1.2. Related Surveys

The body of literature surrounding ROS 2 has expanded significantly, with various surveys addressing specific aspects of this robotic operating system. In this subsection, we highlight key surveys, their focal points, the gaps they reveal, and how our work contributes to the existing knowledge base. A summarized comparison is presented in

Table 1.

Several noteworthy surveys have examined different facets of ROS 2. For instance, Audonnet et al. [

12] conducted a systematic comparison of simulation software for robotic arm manipulation in ROS 2, while Zhang et al. [

13] reviewed innovative architectures and technology readiness for distributed robotic systems within the edge-cloud continuum, focusing on ROS 2. Macenski et al. [

14] offered a comprehensive survey of modern mobile robotics algorithms in ROS 2, with particular attention to navigation systems. Additionally, Choi et al. [

15] explored priority-driven real-time scheduling in ROS 2, and Macenski et al. [

16] examined the design, architecture, and practical applications of ROS 2 across various environments. Similarly, DiLuoffo et al. [

17] addressed the critical need for secure robotic architectures, advocating for a holistic security approach in ROS 2. Finally, Alhanahnah [

18] evaluated software quality in ROS through static analysis of ROS repositories.

While these surveys contribute valuable insights, each focuses on a narrow aspect of ROS 2. In contrast, our survey offers a comprehensive review, spanning a wide range of research areas, including security, multi-robot systems, modularity, and real-time performance. Furthermore, we introduce a detailed database of ROS and ROS 2 literature, categorized by research domain, targeted robotic platforms, industry focus, and article type. This extensive scope not only fills the gaps identified in previous surveys but also provides a holistic view of ROS 2’s ecosystem and its evolving community contributions.

Table 1.

Comparison of ROS 2 Surveys.

Table 1.

Comparison of ROS 2 Surveys.

| Survey |

Focus Area |

Gaps |

Our Contribution |

| Audonnet et al. [12] |

Simulation software for robotic arms |

Limited to simulation software |

Comprehensive coverage of ROS 2 applications |

| Zhang et al. [13] |

Edge-cloud integration |

Does not cover security, real-time performance |

Wide range of research topics including security and modularity |

| Macenski et al. [14] |

Mobile robotics navigation |

Focuses only on navigation systems |

Holistic view including multi-robot systems and real-time performance |

| Choi et al. [15] |

Real-time scheduling |

Limited to real-time performance |

Inclusion of various research domains |

| Bonci et al. [19] |

Industrial autonomy |

Focused on industrial applications |

Broader application fields |

| Macenski et al. [16] |

ROS 2 architecture and uses |

Lack of systematic research analysis |

Systematic review and database of literature |

| DiLuoffo et al. [17] |

Security in ROS 2 |

Focused solely on security |

Inclusion of multiple research areas |

| Alhanahnah [18] |

Software quality assessment |

Centered on ROS 1 |

Extensive insights into ROS 2 |

1.3. Contributions

This survey provides a comprehensive analysis of the Robot Operating System 2 (ROS 2), highlighting its development, advancements, and applications across various research domains. Our contributions are summarized as follows:

Extensive Literature Review: Our survey systematically reviews the extensive body of literature on ROS 2, categorizing research topics into key areas such as security, multi-robot systems, modularity, and real-time performance. We provide detailed summaries and analyses of significant studies in each area.

Community and Ecosystem Contributions: We highlight the significant contributions of the ROS 2 community, including notable frameworks, tools, and open-source projects. This includes an overview of influential ROS 2 GitHub repositories and their impact on the robotics ecosystem.

Development of a Literature Database: As part of our survey, we introduce a comprehensive online database that catalogs ROS and ROS 2 literature. This database categorizes articles by research domain, targeted robotic platform, industry focus, and article type, making it a valuable resource for researchers and developers.

1.4. Paper Structure

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 provides an overview of ROS & ROS 2, detailing their development history, and core features.

Section 3 discusses ROS 2 architectural improvements over ROS 1, including a comparison between ROS 1 and ROS 2.

Section 4 explores various research topics within ROS 2, such as security, real-time capabilities, and other significant areas like middleware and communication.

Section 5 discusses the ROS 2 frameworks and toolkits, including major contributors and notable GitHub repositories.

Section 6 reviews the applications of ROS 2 across different industries and research domains, highlighting specific case studies of successful implementations.

Section 7 introduces the literature database created as part of this survey, providing an analysis of key insights and trends.

Section 8 concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings, discussing the impact of ROS 2, and emphasizing gaps, future directions, and the importance of continued research and community collaboration.

2. ROS & ROS 2 Overview

In this section, we will explore the distinctions between ROS and ROS 2. Originating in 2014, the Open Source Robotics Foundation (OSRF) and the ROS community identified several deficiencies in ROS, prompting the necessity for an evolved version of ROS. This was driven by the escalating demands of robotics applications, which necessitated enhancements in aspects such as real-time guarantees, quality of service, security, and scalability.

We will start by examining the core features of ROS, subsequently shift our focus to the primary design objectives of ROS 2, and conclude by juxtaposing the two versions. This comprehensive analysis aims to provide a detailed understanding of the evolution of ROS and the improvements brought about by the advent of ROS 2.

2.1. ROS

2.1.1. ROS Design Goals

ROS was fundamentally designed to serve as a unified platform for building single-robot applications. It offers a standard collection of tools, libraries, and conventions that aid in developing a broad spectrum of robotic applications, spanning from basic prototypes to intricate robotic systems. One of the salient design objectives of ROS was to promote reusability and modularity, enabling developers to readily share and consolidate software components, thereby facilitating the creation of sophisticated robotic applications. Notwithstanding the diverse use cases it covers, ROS’s primary focus remains on single-robot systems. While there have been initiatives to extend ROS’s capabilities towards multi-robot systems [

20], these efforts were neither seamlessly integrated nor widely adopted.

The next section will provide an overview of ROS Architecture.

2.1.2. ROS Architecture

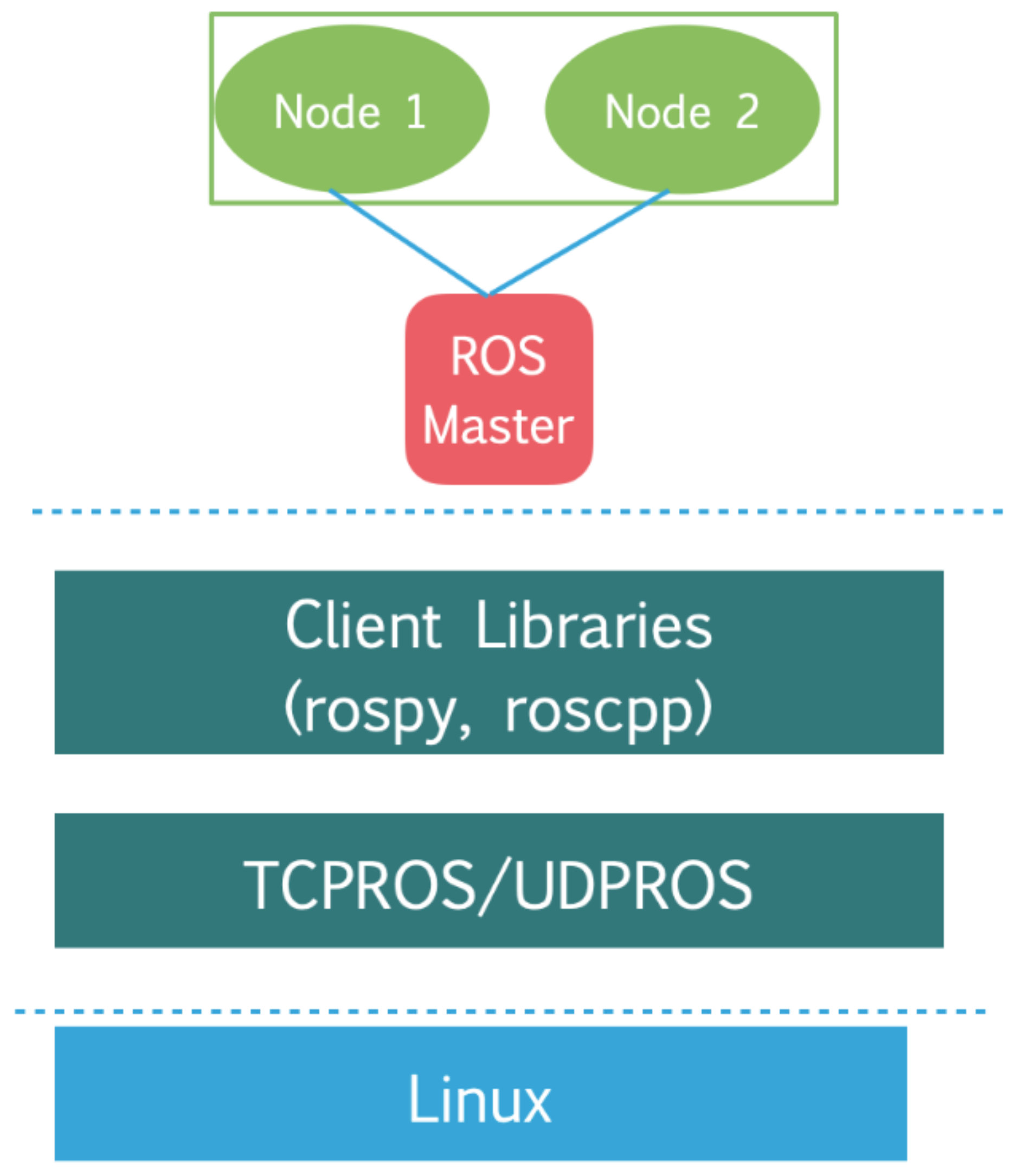

ROS architecture is depicted in

Figure 4 and summarized as follows.

Natively Centralized

The Robot Operating System (ROS) primarily serves as a middleware framework, promoting communication between various processes, called nodes, within a computational machine. Conceptually, ROS can be envisaged as anetwork of nodes (processes), exchanging messages to execute a specific task. This network pivots around a central node, termed the ROS master node (ROSCORE), which serves as a liaison between all nodes within the ROS network. The functionality of the ROS network is critically dependent on this master node. It is worth noting that the dependence on a single master node presents limitations in terms of scalability and introduces a single point of failure.

A ROS node can be a simple C++ program or a Python script, which reads data from other nodes, processes this data, and subsequently publishes it for other nodes. For instance, a camera node may acquire images via its drivers and publish this image data through a specified channel or topic (e.g., /camera/rgb/). Another node may receive this image data, process it using computer vision algorithms, and send the results to another node for appropriate action.

A Modular and Scalable Architecture

The structure of ROS, characterized by its distributed nodes, closely reflects the concept of a microservices architecture. In such an architecture, a monolithic application is partitioned into smaller, standalone services, each performing a specific function. This design is a strategic approach to managing complexity in large applications, facilitating modularity, and promoting scalability, as services can be developed, deployed, and scaled independently. Similarly, ROS strongly emphasizes modularity, allowing its applications to be executed and operated over multiple nodes. Each node in a ROS application performs a discrete task and can operate independently, analogous to a service in a microservices architecture. This arrangement allows for simplified debugging, testing, and understanding of individual components while permitting complex behaviors when the components interact. Thus, ROS’s modular and distributed nature echoes the microservices architecture principles, enhancing maintainability and scalability in robotic applications.

Communication Patterns

ROS employs several communication mechanisms that enable a seamless exchange of information between nodes.

Publisher-Subscriber (Topics): Fundamental to ROS’s communication infrastructure is the Publisher-Subscriber model, implemented through Topics. In this model, a node that generates data serves as the Publisher, broadcasting information over a channel known as a Topic. Other nodes that need this information can subscribe to the respective Topic, thereby consuming the published data. This decoupled communication model enables a many-to-many data flow, promoting the distribution of data to all interested nodes. Topics carry ROS messages, which encapsulate the information to be transmitted. The Publisher-Subscriber paradigm enhances flexibility, as nodes can dynamically publish or subscribe to Topics, and robustness, as the failure of one node does not directly impact others.

Synchronous Client/Server: (Services) Services denote the synchronous client/server model within ROS. In this paradigm, a client node sends a request to a server node and waits for a response. The client is unable to perform other tasks until this response is received, indicating a synchronous operation. This model is applied when the server can complete the task swiftly and the client requires an immediate response. If the task duration is prolonged, the Services model becomes unsuitable, and the ROSLib concept is employed instead.

Asynchronous Client/Server: (ActionLib) The ActionLib model signifies theasynchronous client/server model in ROS. This model contrasts with ROS Services in that the ActionLib client is not blocked while waiting for the server’s response. The client can concurrently execute other tasks while the server processes its mission. In addition, the ActionLib server can send intermediate results to the client, updating it on the task progress. This model is particularly useful for tasks such as robot navigation, where the server processes a navigation request over an extended period, and the client monitors progress while performing other tasks.

Messages and Services: In ROS, two distinct types of entities are used to facilitate communication: Messages for Topics and Services for synchronous client-server communication. Messages (rosmsg) are simple data structures comprising typed fields. They are used when nodes want to transmit data to one or multiple recipients. On the other hand, Services (rossrv) are defined by a pair of messages, one for the request and one for the response. They are used for synchronous RPC-like communication. This division, while serving its purpose, introduced complexity to the development process, as developers had to work with different types of entities depending on the communication model employed.

Client Libraries and Communication Middleware

While the fundamental concepts of ROS are retained in ROS 2, substantial differences lie in the client libraries, the communication middleware, and their underlying implementations.

In ROS, two primary client libraries are used: rospy for Python and roscpp for C++. These libraries provide the means for creating ROS nodes and handling the communication between them. Rospy primarily supports Python 2 across all ROS versions, except for the final ROS version, ROS Noetic, which introduces Python 3 support.

Regarding communication middleware, ROS employs a custom-made middleware: ROSTCP and ROSUDP, based on the TCP and UDP protocols, respectively. ROSTCP ensures reliable, connection-oriented communication, while ROSUDP enables connectionless communication with less overhead but no delivery guarantees. However, these custom protocols present limitations, such as the lack of real-time capabilities and difficulty in configuring Quality of Service (QoS) settings.

In contrast, ROS 2 introduces new client libraries, namely rclcpp and rclpy, with significant improvements over their ROS counterparts. More notably, ROS 2 transitions from custom protocols to the standardized Data Distribution Service (DDS) middleware for its communication infrastructure. This shift addresses the limitations of ROS middleware and will be explored in detail in the following section.

2.1.3. Limitations of ROS and the Motivation for ROS 2

Despite the significant contributions of ROS to the robotics community, certain limitations have prompted the development of a more advanced version. The deliberation to address these limitations began at the ROSCon 2014 conference, where the Open Source Robotics Foundation (OSRF) and the ROS community collectively identified areas of improvement.

Single-Robot Focus: The primary limitation of ROS is its exclusive design for single-robot applications. The absence of inherent support for multi-robot systems presented a challenge for applications involving swarms or collaborative robots. This is primarily attributed to ROS’s design requirement of a central ROS Master node, creating an isolated network per robot. In multi-robot applications, this necessitates additional packages to enable inter-robot cooperation. ROS 2 has addressed this limitation by removing the requirement for a ROS Master node, which we will discuss later.

Lack of Real-Time Guarantees and Quality of Service: Another significant drawback of ROS is the absence of real-time guarantees and Quality of Service (QoS) profiles for prioritizing critical messages. ROS’s reliance on TCP and UDP protocols translates to a best-effort service for message delivery without any assurance of successful transmission. The absence of message prioritization implies that critical and regular messages are treated on par, making it unsuitable for industrial-grade applications with stringent real-time and safety requirements, such as autonomous vehicles or unmanned aerial systems.

Reliability and Scalability Concerns: Lastly, the reliability and scalability of ROS are challenged by its dependency on the central ROS Master node. The entire network fails if the ROS Master node crashes, establishing a single point of failure. This design also constrains the scalability of ROS.

In the following section, we delve into how ROS 2 has been designed to address and overcome these limitations.

2.2. ROS 2

2.2.1. ROS 2 Design Goals

The design of ROS 2 was primarily driven by the need to overcome the limitations of ROS, as discussed in the previous section.

Focus on Swarm Robotics

In contrast to ROS, which was primarily designed for standalone robots, ROS 2 has been engineered emphasizing swarm robotic applications. The inherent complexity of swarm robotics necessitates a fully distributed middleware that enables ad-hoc communication between multiple devices. This distributed communication structure allows for the efficient coordination and collective behavior that characterize a robot swarm. This shift towards a more distributed architecture is a key factor differentiating ROS 2 from its predecessor.

Real-Time and QoS Guarantees

ROS’s lack of support for real-time guarantees and Quality of Service (QoS) were significant limitations, especially for applications with stringent timing and reliability requirements. To address this, real-time support and QoS guarantees were positioned at the forefront of ROS 2’s design considerations. The middleware used in ROS 2 is expected to provide sophisticated QoS policies, ensuring the prioritized and timely delivery of messages based on their importance and urgency. These features are crucial for applications that require high reliability and deterministic execution, such as autonomous vehicles and industrial automation systems.

Fast Prototyping and Cross-Platform Compatibility

Another important aspect of ROS 2’s design is its emphasis on enabling a seamless transition from fast prototyping to production, coupled with cross-platform compatibility. This focus is designed to facilitate the rapid development and deployment of ROS 2 applications across a variety of platforms and into production environments. This compatibility and ease of deployment are expected to expedite the development cycle, a significant improvement over ROS, which presented challenges in these areas.

Middleware Selection

The above design goals significantly influenced the selection of the communication middleware for ROS 2. The need for a robust, efficient, and reliable communication infrastructure that could meet the advanced requirements of real-time processing, Quality of Service, and distributed system support guided the choice of middleware. After extensive deliberations in 2014, the Data Distribution Service (DDS) was chosen for its inherent ability to meet these requirements. DDS, a standard for high-performance, scalable, and interoperable publish-subscribe communication, was deemed perfectly suited for the task. The choice of DDS as the middleware plays a pivotal role in ensuring that ROS 2 successfully addresses the limitations of ROS and meets its design objectives.

2.2.2. ROS 2 Architecture

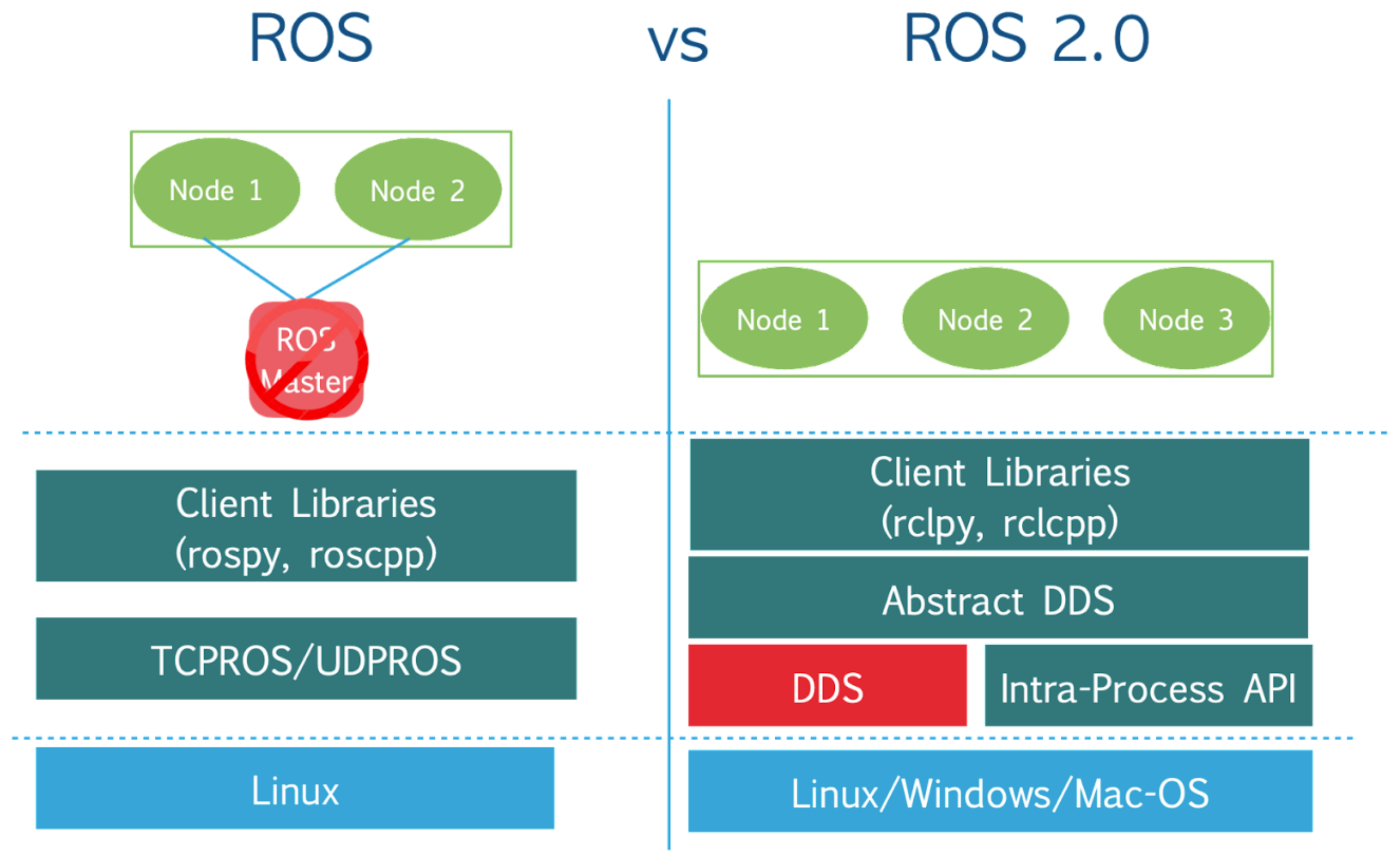

ROS 2’s architecture, as presented in

Figure 5, retains similarities with ROS in certain aspects but also presents a significant evolution to address ROS’s limitations.

Distributed by Design

In contrast to ROS’s centralized approach, ROS 2 is designed to be inherently distributed. It eliminates the need for a central ROS master node, thereby addressing the single point of failure and scalability issues present in ROS. Instead, ROS 2 nodes communicate directly with each other, facilitated by the underlying DDS middleware. This decentralized design is more fitting for multi-robot systems and enables more efficient and reliable communication in large-scale, distributed robotic applications.

Maintained Modularity and Enhanced Scalability

Like ROS, ROS 2 upholds the principle of modularity, where each node operates independently and performs a specific task. However, ROS 2 extends this concept to incorporate the notion of ’Managed Nodes’ that can be governed by a lifecycle manager, thereby providing more control over the system’s state and behavior. Furthermore, the distributed nature of ROS 2 enhances scalability, enabling the system to handle a more considerable number of nodes efficiently.

Extended Communication Patterns

ROS 2 inherits the primary communication patterns of ROS, with some notable improvements and extensions.

Publisher-Subscriber (Topics): The Publisher-Subscriber model, implemented via Topics, remains a vital part of ROS 2. However, ROS 2 introduces the concept of Quality of Service (QoS) policies for Topics, allowing more precise control over message delivery.

Synchronous Client/Server (Services): The synchronous client/server model, facilitated by Services, is also retained in ROS 2. Yet, similar to Topics, Services in ROS 2 support QoS settings, enabling reliable and timely communication based on specific requirements.

Asynchronous Client/Server (Actions): The asynchronous client/server model, formerly denoted by ActionLib in ROS, has been incorporated into the core of ROS 2 as Actions. Actions in ROS 2 provide a more streamlined interface and support QoS policies, offering improved reliability and flexibility.

Interfaces: In ROS 2, the concept of Interfaces is introduced, which encapsulates the functionality of Topics, Services, and Action messages. Interfaces replace the separate message types used in ROS, namely rosmsg and rossrv. This consolidation is an attempt to simplify the message generation process and to facilitate compatibility between different communication models. Interfaces enhance the consistency and maintainability of the ROS 2 communication model, as developers only need to familiarize themselves with a single message type, regardless of the communication pattern they employ. This simplification also enhances code portability between different ROS 2 applications, leading to a more robust and flexible system design.

Enhanced Client Libraries and Advanced Communication Middleware

ROS 2 introduces updated client libraries, rclcpp for C++ and rclpy for Python, which are more robust, maintainable, and feature-rich compared to their ROS counterparts. The most significant shift in ROS 2 is adopting the Data Distribution Service (DDS) as its communication middleware. DDS is an industry-standard middleware designed for high-performance, real-time, scalable, and interoperable publish-subscribe communication. The use of DDS in ROS 2 addresses the limitations of the customs protocols used in ROS. It provides native support for real-time communication, configurable QoS policies, and robust security mechanisms. Furthermore, the standardized nature of DDS facilitates interoperability with other systems and technologies, broadening the scope and applicability of ROS 2.

In the next section, we will further examine the distinctions between ROS 1 and ROS 2 across various non-architectural aspects.

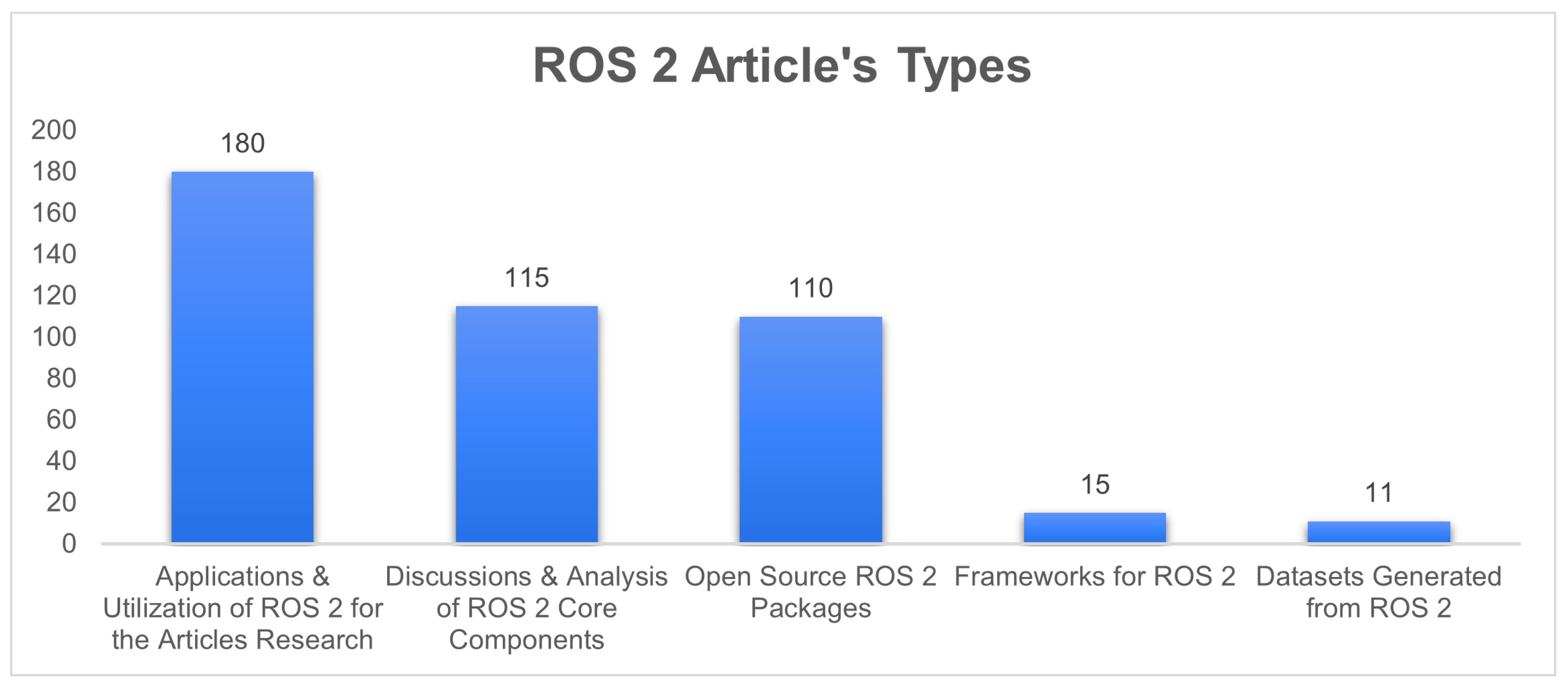

Figure 6.

ROS 2 Puplications Catgories.

Figure 6.

ROS 2 Puplications Catgories.

3. ROS vs. ROS 2

This section discusses the non-architectural differences between ROS and ROS 2 from different perspectives.

3.1. Programming Languages (C++ and Python Differences)

In ROS 2, both C++ and Python programming languages are embraced, but their utilization differs from ROS.

C++ in ROS 2: ROS 2 offers enhanced support for modern C++ features, including move semantics and lambda functions. This improved support leads to better performance and code readability in ROS 2 applications. Developers can leverage new language features and libraries that were previously unavailable in the older C++03 version. Notably, certain core libraries in ROS 2 have been upgraded to support C++14, expanding the range of modern C++ capabilities that can be utilized. These advancements empower developers to take full advantage of the latest features and functionalities offered by the C++ programming language.

Python in ROS 2: In contrast to ROS, which predominantly utilized Python 2, ROS 2 adopts Python 3 as its primary version. Consequently, ROS 2 packages are primarily written in Python 3. This transition allows developers to leverage recent Python enhancements, such as type hints and improved asyncio support. By aligning with the broader Python language community, ROS 2 enables seamless integration with other Python-based tools and libraries. However, it’s important to note that compatibility updates are required for any existing Python 2 code intended for ROS 2 usage.

Language-Agnostic Communication Interfaces: One of the notable advancements in ROS 2 is the introduction of the Abstract Data Distribution Service (DDS) interface, a language-agnostic communication protocol. This protocol enables seamless interaction and communication between nodes written in different programming languages. With DDS, nodes can exchange messages and information efficiently, regardless of whether they are implemented in C++, Python, or any other supported language. This language-agnostic approach facilitates interoperability and collaboration among diverse robotic systems.

These disparities in language support between ROS and ROS 2 emphasize the significance of staying abreast of the latest language features and standards. By accommodating modern C++ and Python versions, ROS 2 empowers developers to fully capitalize on the latest advancements in these languages, enhancing the quality and efficiency of their robotic applications. Ultimately, the choice between C++ and Python hinges on the specific requirements of the target robotics system, and ROS 2’s language flexibility caters to diverse needs.

3.2. Executors

In ROS 2, executors play a pivotal role in managing the execution of tasks within a node’s lifecycle. They facilitate communication between nodes and ensure the execution of callbacks for incoming messages, services, and actions, significantly influencing the overall ROS 2 architecture.

ROS 2 encompasses three executor types each offering distinct characteristics and benefits:

SingleThreadedExecutor: This executor executes all callbacks within a single thread, employing a round-robin scheduling approach to ensure fairness between tasks. However, computationally intensive tasks may experience slower execution due to the shared thread among all tasks.

MultiThreadedExecutor: Designed to handle high workloads and computationally intensive tasks, this executor employs multiple threads to execute callbacks concurrently. While it provides improved performance, careful synchronization is necessary to avoid potential race conditions or deadlocks.

StaticSingleThreadedExecutor: This executor is similar to SingleThreadedExecutor but is specifically designed for nodes with a fixed set of entities (such as sensors, actuators, or other components) known during the compilation process. It optimizes runtime costs by scanning the structure of the node, including subscriptions, timers, service servers, and action servers, only once during node addition. Unlike other executors, it does not regularly scan for changes. Therefore, the StaticSingleThreadedExecutor is most suitable for nodes that create all their subscriptions, timers, and other entities during initialization and do not dynamically add or remove them during runtime. By eliminating the need for continuous scanning, it improves performance and efficiency in such static systems.

In contrast, ROS employs a " spinner " mechanism to manage callback execution within a node’s lifecycle. Two primary spinner types are available:

ros::spin(): This single-threaded spinner sequentially processes callbacks within a single thread until the node is shut down. It represents the simplest and most commonly used spinner in ROS.

ros::AsyncSpinner: This multi-threaded spinner concurrently processes callbacks using multiple threads, suitable for scenarios involving computationally intensive tasks or varying callback execution times.

While spinners in ROS serve a similar purpose to executors in ROS 2, the latter offers advanced features and greater flexibility in task execution, including the StaticSingleThreadedExecutor for static systems. Moreover, introducing the Data Distribution Service (DDS) middleware in ROS 2 necessitates a refined and adaptable approach to task execution, effectively addressed by the concept of executors.

Using executors in ROS 2 provides efficient task management and optimal utilization.

3.3. Transformations: tf vs tf2

The original library for managing transforms in the Robot Operating System (ROS), known as tf [

21], utilizes a static transform tree to outline the relationships between coordinate frames. However, tf exhibits certain limitations, including susceptibility to errors during concurrent multi-thread access to the transform tree and inefficiency when handling large trees.

In contrast, tf2, an advanced version, employs a more efficient data structure for the transform tree representation, enhancing both speed and robustness. It is designed to be thread-safe, thereby eliminating the risk of errors during simultaneous access by multiple threads.

A novel feature introduced in tf2 is the Buffer, a sophisticated data structure that oversees the transform tree. It offers APIs for querying transforms between coordinate frames, thereby increasing the versatility and usability of the system.

A significant distinction between tf and tf2 lies in their support for coordinate representations. While tf is limited to the XYZ Euler angle representation for rotations, tf2 supports multiple representations. These include quaternions, rotation matrices, and angle-axis representations, thereby offering a more comprehensive and flexible system for users.

Moreover, tf2 introduces several new features, including support for non-rigid transforms and the capability to interpolate between transforms. It also enhances debugging and visualization support, thereby simplifying the process of diagnosing issues with the transform tree.

To summarize, due to its superior performance, thread safety, and additional features, tf2 is the recommended library for managing transforms in ROS 2. Its design and functionality improvements over tf make it a more robust and efficient tool for managing coordinate frame relationships.

3.4. ROS 2 Navigation Stack: Main Features and Comparison with ROS 1

The ROS 2 Navigation Stack, also known as Navigation2, is a significant upgrade from the ROS 1 navigation stack, with several key features that enhance its functionality and usability. A comprehensive description of the ROS 2 Navigation Stack can be found in the following reference: [

22]. In what follows, we present a systematic and methodological comparison of the ROS 1 and ROS 2 navigation stacks:

Task Orchestration using Behavior Trees introduces the use of a behavior tree for task orchestration, a feature absent in ROS 1. This tree orchestrates planning, control, and recovery tasks, with each node invoking a remote server to compute one of these tasks using various algorithm implementations.

Modularity and Configurability: Navigation2 is designed to be highly modular and configurable, a marked improvement over ROS 1. It employs a behavior tree navigator and task-specific asynchronous servers, each of which is a ROS 2 node hosting algorithm plugin. These plugins are libraries dynamically loaded at runtime, allowing for unique navigation behaviors to be created by modifying a behavior tree.

Managed Nodes: ROS 2 introduces the concept of Managed Nodes, servers whose life-cycle state can be controlled. Navigation2 exploits this feature to create deterministic behavior for each server in the system, a feature not present in ROS 1.

Feature Extensions: Navigation2 supports commercial feature extensions, allowing users with complex missions to use Navigation2 as a subtree of their mission. This is a unique feature not found in ROS 1.

Multi-core Processor Utilization: Unlike ROS 1, Navigation2 architecture leverages multi-core processors and the real-time, low-latency capabilities of ROS 2. This allows for more efficient processing and faster response times.

Algorithmic Refreshes: Navigation2 focuses on modularity and smooth operation in dynamic environments. It includes the Spatio-Temporal Voxel Layer (STVL), layered costmaps, the Timed Elastic Band (TEB) controller, and a multi-sensor fusion framework for state estimation, Robot Localization. Each of these supports holonomic and non-holonomic robot types, a feature not as developed in ROS 1.

State Estimation: Navigation2 follows ROS transformation tree standards for state estimation, making use of modern tools available from the community. This includes Robot Localization, a general sensor fusion solution using Extended or Unscented Kalman Filters. This is a more advanced approach compared to ROS 1.

Quality Assurance: Navigation2 includes tools for testing and operations, such as the Lifecycle Manager, which coordinates the program lifecycle of the navigator and various servers. This manager steps each server through the managed node lifecycle: inactive, active, and finalized. This systematic approach to quality assurance is a significant upgrade from ROS 1.

Navigation2 builds on the successful legacy of ROS Navigation but with substantial structural and algorithmic refreshes. It is more suitable for dynamic environments and a wider variety of modern sensors, making it a more advanced and versatile navigation stack than its predecessor, ROS 1.

3.5. ROS 2 Security

The key difference in security between ROS and ROS 2 is that ROS 2 has been designed with security in mind from the ground up, whereas security was not a primary consideration in the initial development of ROS.

In ROS, security mechanisms such as authentication and encryption were not implemented by default, leaving systems vulnerable to potential security threats. However, ROS users could implement security measures manually by using third-party libraries and plugins.

ROS 2, on the other hand, has a built-in security framework that provides authentication, encryption, and access control by default. This framework enables ROS 2 to support secure communication between nodes and across networks, even when communicating with nodes that may not support security natively.

SROS2 (Secure ROS2) [

23] is a security extension for ROS 2 that provides additional security features beyond those provided by the ROS 2 security framework. SROS is designed to address some of the limitations of the ROS 2 security framework and to provide enhanced security for critical robotic applications. SROS provides a more flexible and configurable access control system than the default ROS 2 permission system, allowing administrators to define fine-grained access policies for topics, services, and nodes. This can help to ensure that sensitive data and resources are protected from unauthorized access.

Overall, by implementing SROS in ROS 2, users can benefit from additional security features that are not available in ROS. This can help to ensure the security and integrity of critical robotic applications while also providing a more flexible and configurable security solution that can be tailored to the specific needs of each application.

3.6. Comparison of Platform Support in ROS and ROS 2

ROS (Robot Operating System) and its successor, ROS 2, are widely used frameworks for developing robotic systems. This section explores the level of support and compatibility with different operating systems in both frameworks. Specifically, we will examine the support for Windows, macOS, and Linux platforms, highlighting the advancements made in ROS 2.

Windows Support: When it comes to Windows support, ROS has experimental compatibility, while ROS 2 boasts more comprehensive and reliable support for Windows 10. The enhanced support in ROS 2 allows developers to leverage the framework more effectively on Windows machines, ensuring a stable and efficient environment for building robust robotic applications.

macOS Support: Both ROS and ROS 2 offer official support for macOS. However, ROS 2 surpasses its predecessor in terms of compatibility with the latest macOS versions. By capitalizing on the latest macOS features, such as the Metal graphics API, ROS 2 maximizes performance in specific applications. This advanced compatibility empowers developers to fully exploit the potential of macOS when constructing sophisticated robotics systems.

Linux Support: Both ROS and ROS 2 offer comprehensive support for Linux, with official support for various popular distributions. However, ROS 2 takes a more modular and flexible approach, making porting the framework to different Linux distributions and architectures easier. This flexibility is particularly advantageous in heterogeneous computing environments, allowing developers to deploy ROS 2 on various Linux systems.

The utilization of the Data Distribution Service (DDS), which inherently possesses cross-platform capabilities, significantly facilitated the seamless compatibility of ROS 2 with Windows, macOS, and Linux. In contrast, ROS 1 relied on the specific TCPROS and UDPROS protocols, which were more tightly coupled with the Linux environment, limiting its cross-platform compatibility.

While both ROS and ROS 2 offer support for multiple operating systems, ROS 2 surpasses its predecessor regarding platform compatibility. With its comprehensive support for Windows 10, better compatibility with the latest macOS versions, and flexibility in porting to different Linux distributions and architectures, ROS 2 provides a more robust and versatile framework for building robotic systems. The technical advancements in ROS 2, such as the use of DDS and modular architecture, further enhance its compatibility and usability across different operating systems. Developers can leverage these advancements to create efficient and reliable robotics applications on their preferred platforms.

4. Literature Analysis on Key ROS 2 Design Areas

This section provides a detailed analysis of the current research surrounding critical design areas in ROS 2, including real-time capabilities, middleware, QoS, security, and support for embedded and distributed systems, as well as multi-robot systems (MRS). Each of these areas plays a crucial role in shaping the effectiveness and performance of ROS 2 for modern robotics applications. By examining the key challenges and recent advances in each domain, we aim to highlight the gaps in the current literature and ongoing efforts to address them.

Table 2 offers a taxonomy of these areas, outlining the core issues and the technological innovations that are advancing the state of the art.

Following this, we delve into each domain, providing insights into the motivations driving research, the contributions made, and the existing limitations that researchers and developers continue to tackle.

4.1. ROS 2 Benchmarking

The evolution from ROS 1 to ROS 2 has successfully addressed crucial shortcomings in real-time communication, modularity, and support for multi-robot systems (MRS), catering to the increasing complexity of robotic environments. This shift has catalyzed a wave of scholarly investigation, focusing on rigorously evaluating ROS 2’s refined features across a spectrum of use cases. In this section, we explore pivotal research articles that critically assess the core functionalities of ROS 2, as highlighted in

Figure 2. These studies offer insights into the system’s enhanced performance, demonstrating its potential and identifying areas for further enhancement.

4.1.1. ROS 2 Performance and Software Quality Benchmarking

Several studies, such as [

18,

24,

25], and [

16], explore and benchmark the overall performance of ROS 2 across various parameters. Specifically, [

25] examines node composition within ROS 2, contrasting it with traditional multi-process systems. This benchmarking focuses on memory footprint, CPU usage, and latency, revealing that node composition, especially with intra-process communication (IPC), dramatically reduces memory usage by 33% and CPU load by 28%. Notably, the application of IPC in node composition lowers CPU usage by nearly an order of magnitude for larger messages and achieves latency reductions as low as 40

s, closely aligning with the performance of monolithic applications.

Furthermore, [

18] conducts an empirical study evaluating the software quality of ROS2 Java projects using the PMD static analysis tool. The study assesses multiple coding standards, including security, performance, and code style. It identifies 33,533 alerts, with 62% related to code style issues, 7% to performance, and a smaller percentage related to error-prone issues. Additionally, the study reveals specific security concerns, such as insecure default settings in ROS2’s DDS implementation, where key security features like encryption and signing were disabled.

4.1.2. ROS 2 Tools and Navigation Benchmarking

Studies such as [

12] and [

14] benchmark various tools and developments for ROS 2. For instance, [

12] systematically evaluates five simulation software tools—Ignition, Webots, Isaac Sim, PyBullet, and Coppeliasim—focusing on robotic manipulation tasks like pick-and-place and throwing. The results indicate that no single tool excels in all areas. Webots and Ignition demonstrated the most stability and accuracy in Task 1, with Webots achieving a task success rate of 88% (without GUI) and using 144% CPU and 1191 MB RAM (162% CPU and 1322 MB RAM in GUI mode). Ignition showed similar performance, with a task success rate of 91% and consuming 202% CPU and 686 MB RAM (205% CPU and 775 MB RAM in GUI mode). Isaac Sim, while offering advanced features like machine learning integration, exhibited a high memory usage of 10,070 MB RAM and achieved a task success rate of 89% but failed to maintain consistency across runs.

Meanwhile, PyBullet and Coppeliasim were more resource-efficient but showed lower task success rates, with PyBullet achieving only 18% task success in Task 1 and using 117% CPU and 663 MB RAM (140% CPU and 919 MB RAM in GUI mode), and Coppeliasim showing a 92% success rate but consuming 135% CPU and 860 MB RAM (100% CPU and 850 MB RAM in GUI mode). For Task 2, Webots demonstrated better throwing consistency, with a cube movement success rate of up to 50%, while Coppeliasim had a 50% success rate but a higher failure rate of 32%. Isaac Sim exhibited an 83% success rate for cube movement but suffered from inconsistent motion behavior, impacting overall performance.

Similarly, [

14] focuses on the ROS 2 Nav2 project, benchmarking path and trajectory planners across various robot types, including quadrupeds and Ackermann-steering vehicles. The study presents a comprehensive analysis of planners such as NavFn, Lazy Theta*-P, Smac 2D-A*, Smac Hybrid-A*, and Smac State Lattice, with Smac Hybrid-A* achieving the best performance in plan time (38.77 ms) and Lazy Theta*-P providing the shortest path length (50.28 meters). In terms of trajectory planners, benchmarks show Model Predictive Path Integral (MPPI) operating at 125 Hz and Regulated Pure Pursuit achieving frequencies above 4,000 Hz. Path smoothers, such as the Simple Smoother and Constrained Smoother, significantly improved path quality, with the Constrained Smoother yielding the best smoothness at 87.85. Additionally, state estimators like fuse demonstrated improved accuracy (with an error of 2.81 meters over a 542-meter route) compared to robot localization, though at a higher CPU cost (5.19% vs. 1.38%). These findings highlight significant improvements in ROS 2 over ROS 1, including enhanced flexibility, performance, and better support for modern robotic platforms. ROS 2 is shown to be well-suited for product-grade applications, and ongoing developments continue to push its capabilities forward, making it ideal for complex and large-scale robotics projects.

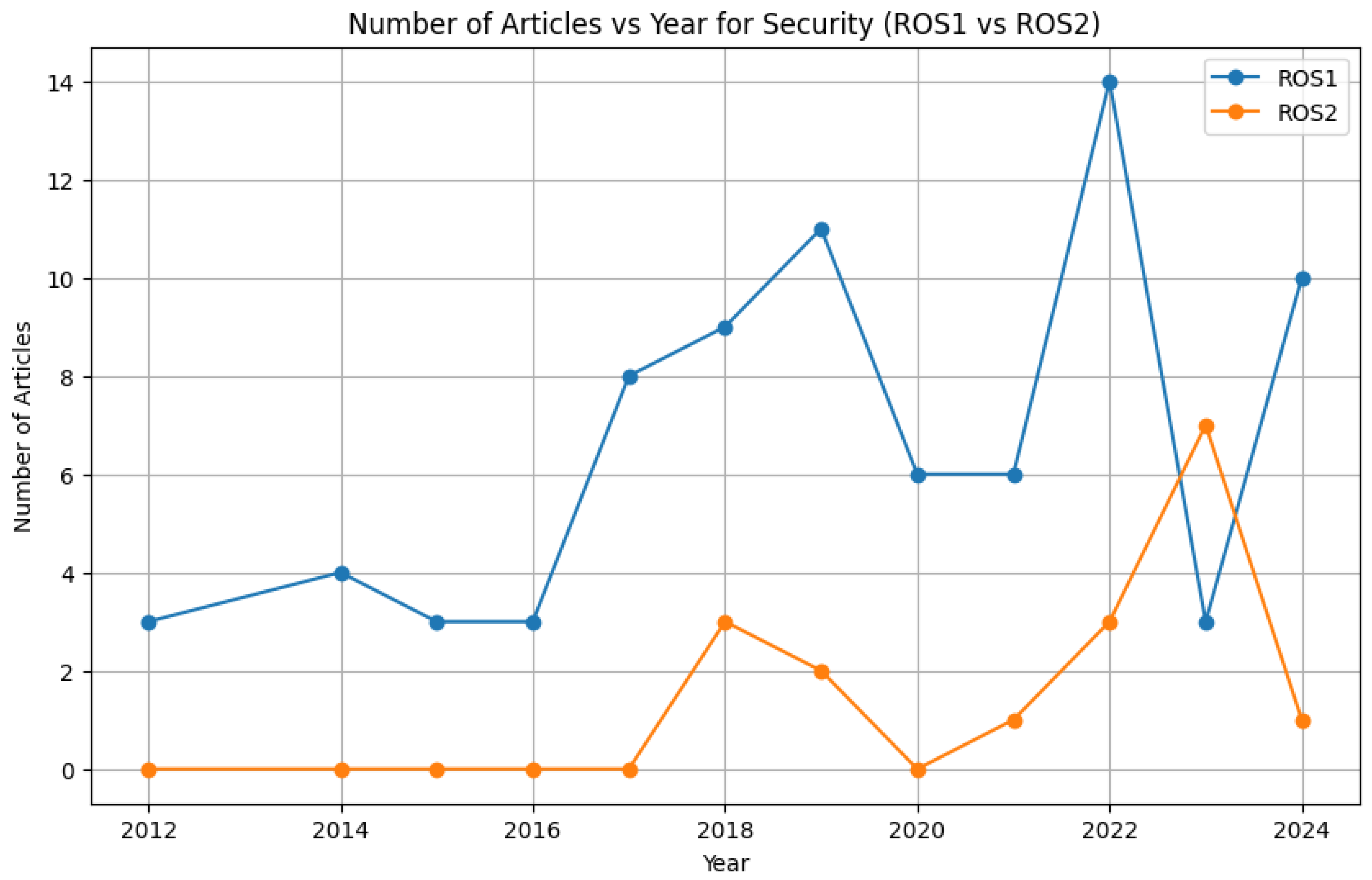

4.2. ROS 2 Security

As robotic systems are deployed in critical sectors such as healthcare, defense, and autonomous transportation, ensuring robust security in ROS 2 becomes vital. The transition to ROS 2 has brought improvements in communication and modularity, but security remains a critical challenge, particularly in terms of access control, communication integrity, and forensic capabilities. This section synthesizes recent advancements, limitations, and ongoing challenges in securing ROS 2 systems.

Challenges in ROS 2 Security: Access control and communication security are two key areas where significant challenges persist. The traditional role-based access control (RBAC) mechanisms, such as those implemented in SROS2, have been criticized for their rigidity and lack of scalability in complex, multi-robot environments. The fixed nature of RBAC often leads to inefficiencies in managing permissions dynamically, particularly in distributed systems [

26,

27]. Additionally, vulnerabilities in the Data Distribution Service (DDS) communication layer, such as unauthorized access, credential masquerading, and denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, have exposed ROS 2 to threats in high-risk environments [

28,

29].

Advances and Solutions: Addressing these challenges, research has focused on developing more flexible access control systems. Attribute-based access control (ABAC) frameworks, combined with blockchain technology, have emerged as a solution to overcome the limitations of RBAC by allowing fine-grained control over user permissions in dynamic environments [

26,

27]. In terms of communication security, there has been a shift towards adopting stronger encryption methods. Studies have evaluated the effectiveness of CAESAR encryption algorithms like Ascon and Deoxys-II, which offer enhanced security without significantly compromising performance [

30]. These encryption protocols have been particularly valuable in securing UAV swarms and multi-robot systems operating over wireless networks, where latency is a critical factor [

31].

Another area of progress is forensic investigation and anomaly detection. Tools such as ROS2Tester have been developed to provide runtime verification and vulnerability detection, enabling better monitoring of distributed systems [

32]. However, research continues to highlight gaps in post-attack forensic capabilities, particularly in recovering tampered data in collaborative robotic environments [

33]. These gaps point to a need for more sophisticated runtime verification techniques, such as the POLAR-Express framework for neural network-driven systems, which enhances anomaly detection and system introspection [

34].

Open Challenges and Future Directions: A significant challenge remains the trade-off between security and system performance. Studies consistently show that enabling security features—such as encryption and authentication—introduces latency and reduces throughput, particularly in wireless and resource-constrained environments [

35,

36]. Moreover, ROS 2 lacks a holistic security framework that addresses vulnerabilities across all layers of the system, from hardware to application-level security. Research in this area is focusing on multi-layered security architectures that provide comprehensive protection without compromising performance [

17].

While considerable advancements have been made in ROS 2 security, there is still a need for more adaptive and scalable solutions. Future research should focus on improving the balance between security and performance, particularly in real-time and resource-constrained environments. Additionally, enhancing forensic tools and anomaly detection mechanisms will be critical for ensuring the long-term security and reliability of ROS 2 systems.

Table 3 summarizes the key challenges and advancements discussed.

4.3. ROS 2 Real-Time Systems

As robotic systems evolve in complexity, real-time capabilities become crucial, especially for applications such as autonomous vehicles, multi-agent systems, and safety-critical robotic systems. Robot Operating System 2 (ROS 2) has gained attention for its potential to meet these demands through its support for Data Distribution Service (DDS) middleware and improvements over ROS 1 in scheduling and real-time operations. However, ROS 2 still faces challenges in ensuring predictable performance, reducing latency, and maintaining real-time constraints in diverse operating conditions. This section provides an aggregated discussion of the advancements, limitations, and open challenges in ROS 2 real-time systems based on recent literature.

Challenges in ROS 2 Real-Time Systems: The primary challenges stem from the unpredictability in callback scheduling, task prioritization, and worst-case response time (WCRT) guarantees. Many works identify that ROS 2’s standard executors lack the necessary mechanisms for efficient real-time execution, particularly in distributed and multi-threaded environments. The default callback execution order and lack of priority mechanisms result in high execution-time variability, causing issues like missed deadlines and buffer overflows [

40,

41,

42]. Moreover, ROS 2 suffers from performance degradation under stress and scalability issues when applied to complex, distributed setups [

43,

44].

Advances and Solutions: A key trend in addressing these challenges has been the development of customized schedulers and executors. Notable efforts include the introduction of priority-based scheduling frameworks such as PiCAS, which incorporates callback prioritization and resource allocation to reduce end-to-end latency [

45,

46]. Other solutions focus on formal real-time analysis frameworks to provide tighter bounds on WCRT for multi-threaded systems, helping designers guarantee that critical tasks meet their deadlines [

47,

48].

Another significant advance is the exploration of containerization and microservice architectures for improving real-time performance in ROS 2, particularly for SDVs and autonomous systems [

49,

50]. These studies have shown that containerized deployments can lead to better latency management and system resource utilization compared to bare-metal configurations. Furthermore, dynamic GPU management frameworks such as ROSGM offer improved processing efficiency, especially for tasks that require intensive computational power [

51].

Open Challenges and Future Directions: Despite these advancements, several gaps remain. Current solutions often fail to provide scalable, flexible, and holistic real-time performance for highly distributed systems, where network delays and jitter introduce significant unpredictability [

52,

53]. Furthermore, while various priority-driven schedulers have been proposed, integrating these into existing ROS 2 frameworks without introducing additional overhead remains a challenge. There is also a growing need for tools that can provide fine-grained runtime monitoring and online latency management to ensure real-time constraints are continuously met in dynamic conditions [

51,

54].

The development of real-time systems in ROS 2 has made significant strides, but further advancements are needed to overcome scalability, flexibility, and overhead challenges. Future work should focus on enhancing distributed real-time performance, integrating more adaptive scheduling frameworks, and developing robust online monitoring tools.

Table 4 summarizes the key trends, challenges, and solutions discussed.

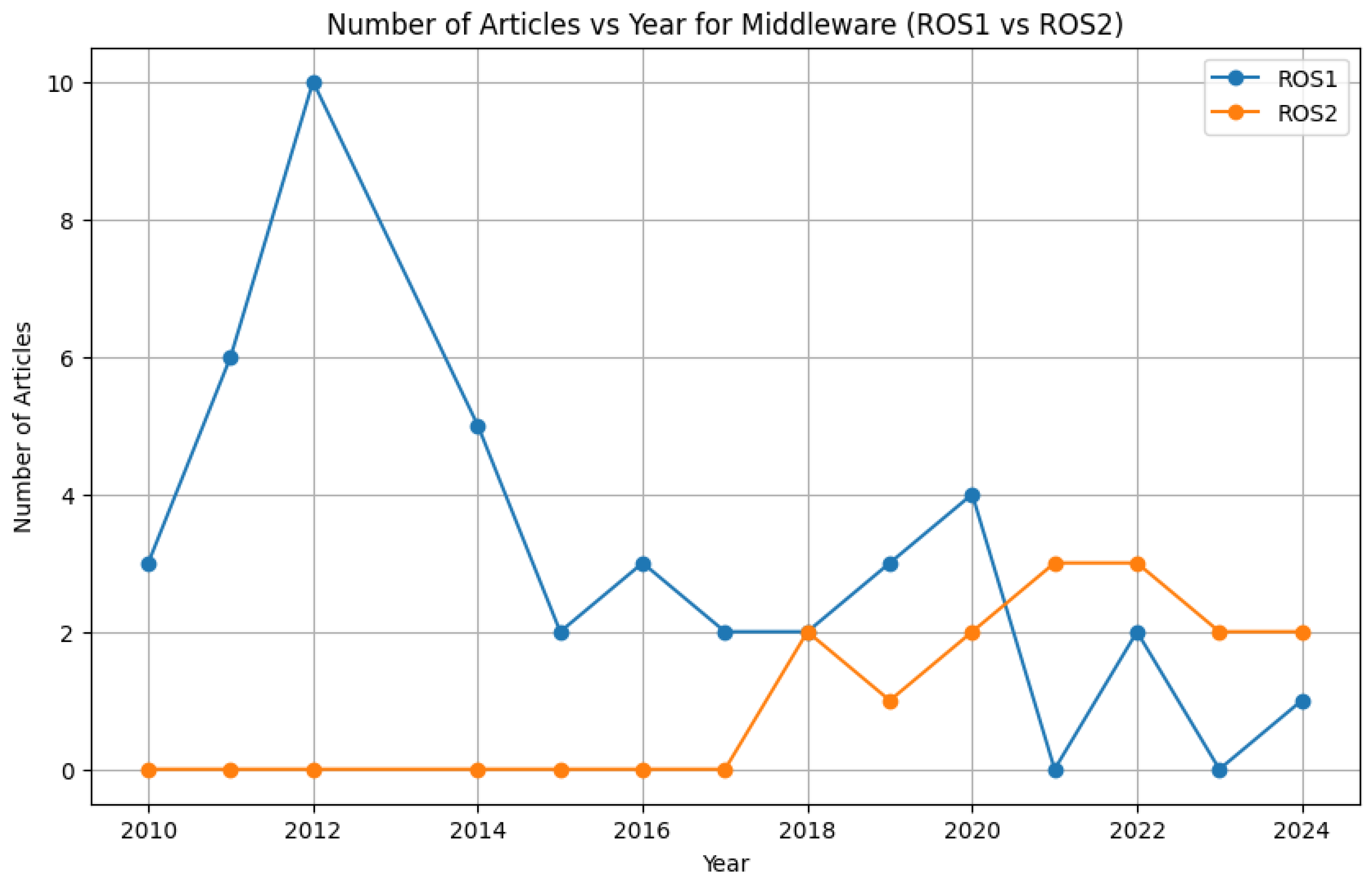

4.4. ROS 2 Middleware

The middleware layer in ROS 2 plays a crucial role in enabling efficient communication between distributed nodes in robotic systems. The Data Distribution Service (DDS) is the default middleware in ROS 2, providing real-time data-centric communication. However, challenges remain, especially in optimizing inter-node communication, handling varying Quality of Service (QoS) requirements, and improving reliability in complex and resource-constrained environments. This section discusses key advancements and challenges in middleware technologies within ROS 2, focusing on recent literature that explores optimizations, alternative middleware, and mechanisms to enhance communication performance.

Challenges in DDS Implementation: Despite the advantages of DDS in enabling real-time communication, it has limitations in scenarios involving intra-node communication, heterogeneous environments, and dynamic QoS requirements. Research has identified inefficiencies when ROS 2 relies on network-based communication mechanisms, even for local interactions, leading to unnecessary latency and overhead [

55]. To address this, studies have proposed dynamic DDS binding mechanisms that allow switching between DDS implementations based on the communication characteristics of each node [

56]. This approach optimizes resource usage and reduces latency by selecting the most appropriate communication method for each task.

Interoperability and Security Concerns: Another significant area of concern is the interoperability between different DDS implementations. While ROS 2 supports multiple DDS vendors (e.g., Fast DDS, Cyclone DDS, RTI Connext), studies highlight challenges when different implementations are used simultaneously, particularly with security features enabled [

57]. The performance overhead introduced by security configurations varies significantly across DDS vendors, requiring careful consideration in critical systems. These studies suggest that ensuring seamless interoperability and minimizing security-related overheads remain open challenges.

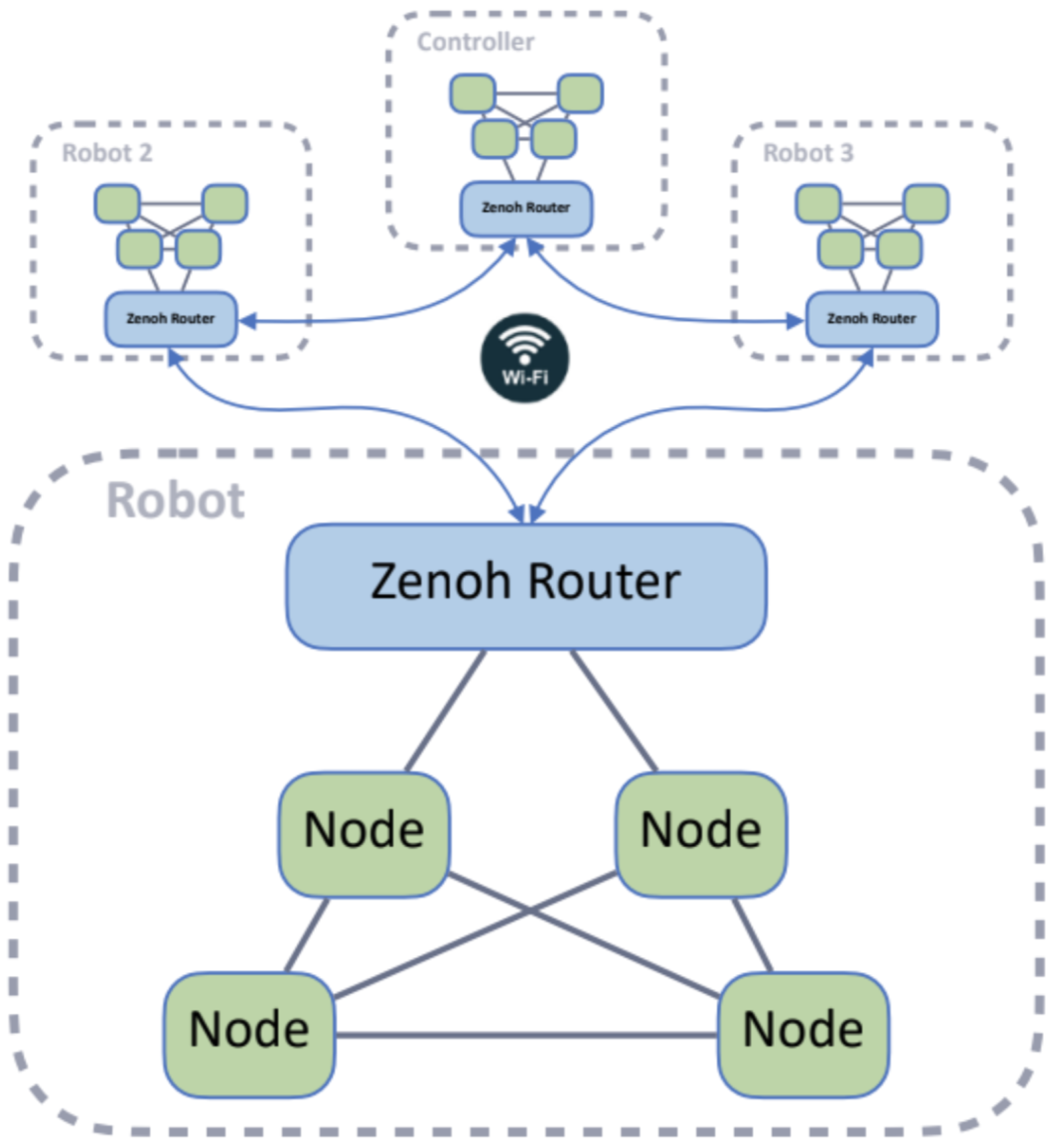

Zenoh Middleware and Dynamic Switching: An important milestone in ROS 2’s communication capabilities was the introduction of Zenoh in the Jazzy distribution. Zenoh offers a novel approach to ROS 2 communication, particularly in environments where traditional DDS may face challenges. The `rmw_zenoh_cpp` middleware interface maps the ROS 2 RMW API onto Zenoh APIs, enabling ROS 2 to utilize Zenoh for data exchange. This integration is depicted in

Figure 7, which illustrates the structure of the middleware and how Zenoh sessions interact with each other and with the Zenoh router. Notably, Zenoh sessions rely on peer-to-peer communication for data transfer while using a Zenoh router for discovery and gossip scouting. This architecture provides flexibility and performance advantages, particularly in distributed systems with varying network conditions.

The dynamic switching mechanism further enhances performance by allowing ROS 2 systems to switch between different middleware protocols based on network conditions and application demands. For instance, Zenoh excels in wireless environments, where it outperforms DDS in terms of latency and throughput, especially in edge-to-cloud communication [

58].

While DDS remains central to ROS 2 middleware, alternative solutions like Zenoh and dynamic DDS switching mechanisms address the limitations posed by static middleware configurations and challenging network environments. Future research should focus on refining these dynamic approaches, improving security interoperability, and expanding middleware support for diverse real-time applications.

Table 5 summarizes the key trends, challenges, and solutions discussed.

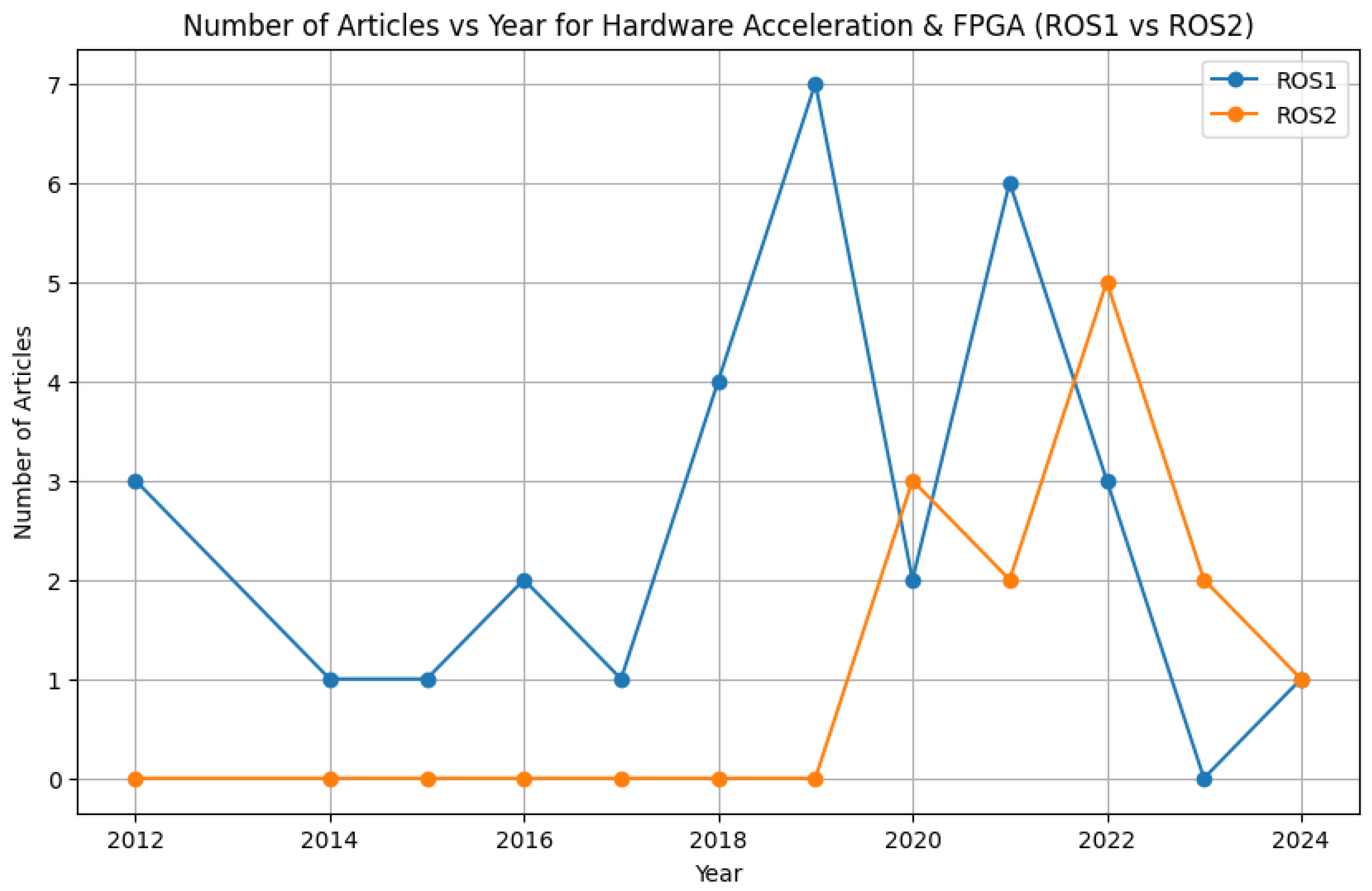

4.5. ROS 2 Embedded Systems and Distributed Systems

The integration of ROS 2 into embedded and distributed systems has gained significant attention in recent years, primarily due to the growing demand for scalable, real-time, and efficient robotic systems. Embedded systems, such as those found in autonomous vehicles, space missions, and IoT devices, present unique challenges due to their constrained resources and real-time requirements. Distributed systems, on the other hand, necessitate efficient communication protocols, particularly when leveraging edge-cloud technologies or containerized environments. This section discusses key advances in these areas within the ROS 2 framework, highlighting the contributions and addressing critical gaps in the literature.

Trends in Embedded Systems: One prominent trend in embedded systems is the adaptation of ROS 2 for real-time, safety-critical applications such as automotive and aerospace systems [

59,

60]. Efforts like Apex.OS extend ROS 2’s capabilities to meet the stringent requirements of automotive-grade environments by integrating best practices from traditional microcontroller-based systems like OSEK. Similarly, the development of Micro-ROS enables ROS 2 to be scaled down for resource-constrained platforms like CubeSats, demonstrating the framework’s adaptability across various hardware configurations [

60].

Moreover, hardware acceleration, particularly using FPGAs, has emerged as a key solution to overcome the limitations of traditional CPU-based implementations. ROS 2-centric architectures that facilitate the integration of FPGAs, such as fpgaDDS and ReconROS, address the inefficiencies in communication between hardware and software nodes [

61,

62]. These solutions significantly enhance real-time performance by leveraging parallel processing and reducing communication bottlenecks, enabling low-latency, high-speed operations in robotics applications.

Advances in Distributed Systems: The shift towards edge-cloud architectures in robotics is another significant trend, with ROS 2 playing a pivotal role in enabling distributed robotic systems [

63]. Technologies like containerization and orchestration, using platforms such as Docker and Kubernetes, allow for scalable, platform-agnostic deployment of robotic applications. However, ROS 2’s communication protocols face challenges in such environments, particularly concerning real-time performance and scalability. Recent research proposes optimization frameworks and orchestration-aware communication protocols to address these limitations [

64]. Additionally, edge computing has proven essential in distributed autonomous driving systems, offloading computational tasks from vehicles to external edge units, thus enabling higher levels of autonomy without the need for expensive on-board resources [

65].

Challenges and Future Directions: Despite these advances, several challenges remain. The scalability of ROS 2 in lossy, wireless networks, particularly in the context of unmanned assets, continues to be a limitation, with research showing increased latency and message loss when security features are enabled [

66]. The integration of ROS 2 with IoT devices also faces resource constraints, although progress has been made with lightweight operating systems like RIOT [

67]. Furthermore, while hardware acceleration shows promise, optimizing the dynamic mapping between hardware and software nodes, especially in event-driven environments, remains a challenge.

Significant strides have been made in adapting ROS 2 for embedded and distributed systems, but challenges in real-time performance, scalability, and resource optimization persist. Future work should focus on refining dynamic communication protocols, improving interoperability across hardware platforms, and further optimizing the integration of edge computing and orchestration in distributed robotic systems.

Table 6 summarizes the key trends, challenges, and solutions discussed.

4.6. ROS 2 Quality of Service (QoS)

As robotic systems increasingly operate in complex, dynamic environments, managing Quality of Service (QoS) in ROS 2 has emerged as a critical research focus. QoS in ROS 2 is essential for ensuring reliable communication between nodes, particularly in real-time applications like multi-robot coordination, remote surgery, and autonomous driving. While ROS 2 introduces flexible QoS profiles to manage data transmission, several challenges persist in optimizing performance, reliability, and security across varied network conditions. This section synthesizes recent research trends, addressing both the advancements and the ongoing limitations in ROS 2 QoS management.

Challenges in ROS 2 QoS: A primary challenge is the reliability of the communication framework, especially when employing the RELIABLE QoS setting. Despite its intention to guarantee message delivery, this setting often struggles in high-data-rate environments or under constrained buffer conditions, leading to message loss in multi-robot systems and aggregated processing architectures [

68,

69]. Additionally, balancing QoS parameters like DEADLINE and DEPTH can be difficult, particularly in real-time applications where both reliability and latency are critical.

Advances and Solutions: To address these issues, research has introduced caching mechanisms that store redundant data locally to reduce communication load and mitigate message loss [

70]. These systems have shown promise in improving overall performance by optimizing data transmission efficiency, especially in environments with high communication demands. Moreover, careful balancing of QoS parameters has been shown to significantly enhance system reliability and timeliness, especially in multi-robot setups.

Another important focus has been the trade-off between QoS and security. ROS 2’s use of the DDS standard introduces robust security features, but these features often introduce additional latency, especially in mission-critical environments like unmanned military vehicles [

71]. Research in this area emphasizes the need to optimize security-aware QoS configurations, where encryption and authentication protocols are balanced with performance requirements to minimize communication delays without compromising security.

Design-Time QoS Specification: Another significant development is the move toward design-time QoS specification. Traditional ROS 2 systems primarily check QoS profiles at runtime, leaving room for unexpected performance issues. To mitigate this risk, researchers have proposed domain-specific languages (DSLs) to formalize QoS requirements before deployment. This proactive approach ensures that systems meet performance and reliability expectations in varying conditions, particularly in multi-agent systems with fluctuating network environments [

72].

QoS in Wireless Networks: The challenges of managing QoS in wireless networks, such as those used in remote driving and teleoperated systems, have also been widely studied. Wireless networks introduce additional latency and data interference, necessitating more dynamic QoS management strategies. Solutions like WiROS dynamically adjust network parameters, such as Enhanced Distributed Channel Access (EDCA), to prioritize critical data flows in congested network environments, ensuring that latency-sensitive applications continue to perform effectively [

73].

Open Challenges and Future Directions: Despite significant progress in QoS management, challenges remain in balancing latency, reliability, and security in diverse deployment scenarios. Research should continue to explore adaptive QoS strategies that incorporate real-time feedback from the network and optimize security mechanisms to minimize their impact on system performance. Future work should also focus on extending dynamic QoS management strategies to better support complex, distributed systems.

Table 7 provides a summary of the key challenges and solutions discussed in ROS 2 QoS research.

4.7. ROS 2 Multi-Robot Systems (MRS)

The development of multi-robot systems (MRS) within ROS 2 has led to significant advancements in communication flexibility and real-time coordination, largely enabled by the Data Distribution Service (DDS) protocol. Despite these improvements, challenges such as synchronization, communication efficiency, and real-time performance remain key concerns, particularly in heterogeneous environments where robots, such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and ground vehicles (UGVs), interact under varying network conditions. This section provides a synthesized discussion of the progress, limitations, and future directions in MRS research within ROS 2.

Challenges in ROS 2 MRS: Synchronization between multiple robots in heterogeneous systems presents a primary challenge, especially when integrating different simulators or real-world robots in real-time, masterless environments. Traditional synchronization techniques from ROS 1 are insufficient, often resulting in high latency and packet loss. These issues are particularly pronounced in scenarios involving varying communication protocols and robot velocities, such as UAV-UGV collaboration [

74]. Additionally, communication architecture inefficiencies, especially in centralized multi-agent systems, further complicate performance. The choice between one-to-one and many-to-one communication architectures can significantly impact key performance metrics, such as data age and data miss ratio [

75].

Advances and Solutions: Research has proposed novel middleware solutions aimed at improving synchronization and reducing latency. For example, velocity-aware middleware has been introduced to optimize the coordination between heterogeneous robots, minimizing packet loss and improving real-time communication [

74]. In centralized multi-agent systems, studies have highlighted the importance of selecting appropriate communication architectures to optimize system robustness and communication efficiency. Comparative studies of DDS vendors, such as CycloneDDS and FastDDS, provide valuable insights for optimizing real-time communication under heavy network loads [

75].

Another key advancement is in managing real-time performance under constrained resources, particularly in low-cost robotic systems. Aggregated processing architectures and cache-control algorithms have shown to reduce latency and prevent data processing failures by offloading computational tasks to centralized environments. Experimental results demonstrate significant improvements in communication efficiency and system reliability, even in resource-constrained settings [

76].

Middleware for Extreme Environments: The use of ROS 2 middleware in extreme environments, such as planetary exploration, has further expanded the field’s understanding of middleware performance in dynamic mesh networks. Zenoh, a ROS 2 middleware implementation, has shown superior performance in delay reduction and CPU efficiency, making it a suitable candidate for space exploration missions where reliable and efficient communication is critical [

77].

Open Challenges and Future Directions: Despite these advancements, several challenges remain in optimizing middleware, communication architectures, and real-time performance in MRS. The scalability of middleware solutions and the integration of adaptive QoS strategies are crucial areas that require further exploration. Additionally, enhancing the interoperability of heterogeneous robotic systems and improving real-time synchronization across diverse environments will be critical to advancing MRS research.

Table 8 provides a summary of the key challenges and solutions discussed in ROS 2 MRS research.

5. Literature Analysis on Key ROS 2 Frameworks and Toolkits

The adaptability and extensive ecosystem of ROS 2 have facilitated the development of numerous frameworks and toolkits, enhancing its utility across a variety of applications. Key frameworks such as Nav2, MoveIt, and Autoware exemplify ROS 2’s capability to handle complex tasks in navigation, manipulation, and autonomous driving, respectively. These frameworks provide robust and flexible solutions for path planning, motion control, and vehicle autonomy, significantly advancing the state of robotic software development.

Table 9.

ROS 2 Open Source Packages.

Table 9.

ROS 2 Open Source Packages.

| Category |

Citation |

| Multi Robotic Systems |

Aerostack2[78], CrazyChoir[10], KubeROS[79], ROS2SWARM[80], The Cambridge RoboMaster[81], Toychain[82], TestbedROS2Swarm[83], ChoiRbot[84], ROS2BDI[85], |

| Cooperative Robotics & HRI |

ChoiRbot[84], ROSGPT[9], opendr[86,87], NAO[88], qml_ros2_plugin[89], PointIt[90], ros2-foxy-wearable-biosensors[91] |

| Simulators |

MVSim[92], HuNavSim[93], LGSVL Simulator[94], LunarSim[95], MAES[96], UUV simulator[97] |

| Computer Vision |

HawkDrive[98], ROSGPT_Vision[99], GLIM[100], UAV Volcanic Plume Sampling[101], YOLOX[102], direct_visual_lidar_calibration[103], Bridging 3D Slicer and ROS2[104], Video Encoding and Decoding for High-Definition Datasets[105], |

| Reinforcement Learning |

ros2-forest[106], gym-gazebo2[107], drl_grasping[108], LPAC[109], opendr[86,87], ros2learn[110], An Educational Kit for Simulated Robot Learning in ROS 2[111,112] |

| Performance Evaluation |

ChoiRbot[84,113], FogROS2[114], DriveEnv-NeRF[115], RobotPerf[116] |

| Real-Time |

CARET[113,117], ros2_tracing[118] |

| Cyber Security |

Bobble-Bot[119], Hyperledger Fabric Blockchain[120], rvd[121], KISS-ICP[122], RCTF[123], SROS2[124], |

| Software Platforms |

Aztarna[125], CFV2[126], SkiROS2[127], SMARTmBOT[128], Space ROS[129], ros2-3gppSA6-mapper[130] |

| State Estimation & Prediction |

MixNet[131], FusionTracking[132], NanoMap[133], wayp[134], lidar_cluster_ros2[135] |

| Planning |

navigation2[136], PlanSys2[137], SAILOR[138], YASMIN[138] |

| Navigation |

mola[139], depth_nav_tools[140], nav2_accountability_explainability[141], Navigation Approach based on Bird’s-Eye View[142], DeRO[143], vox_nav[144,145], evo[146], FlexMap Fusion[147], Mobile MoCap[148], MOCAP4ROS2[149], Multi-Robot-Graph-SLAM[150], pointcloudset[151], flexible_navigation[152], The Marathon 2[22], |

| Embedded & Distributed Systems |

embeddedRTPS[153], forest[154], ReconROS[155,156], FogROS[157], FogROS2[158,159,160], ros2-message-flow-analysis[161], PAAM[162], RobotCore[163] |

| UAV |

anafi_ros[164], CrazyChoir[10], UAV Volcanic Plume Sampling[101], HyperDog[165], Aerostack2[78], MPSoC4Drones[166] |

| UUV |

SUAVE[167], Angler[168], UUV simulator[97] |

| Self-driving Cars |

Autoware_Perf[169], DriveEnv-NeRF[115], XTENTH-CAR[170] |

| Service Robots |

MERLIN & MERLIN2[171,172], |

| Product Integration |

libiiwa[173], HRIM[174], kmriiwa[175], LBR-Stack[176], MeROS[177], OtterROS[178], RCLAda[179], RoboFuzz[180], Wrapyfi[112] |

Nav2, for instance, is a comprehensive navigation framework that supports modular and scalable navigation solutions for mobile robots. It leverages ROS 2’s advanced middleware to deliver reliable path planning and obstacle avoidance in dynamic environments. MoveIt extends ROS 2’s capabilities to robotic manipulation, offering tools for motion planning, control, and 3D perception. Autoware, on the other hand, focuses on autonomous driving, providing a full-stack solution for self-driving vehicles, including perception, planning, and control.

Table 10 shows different libraries and their application.

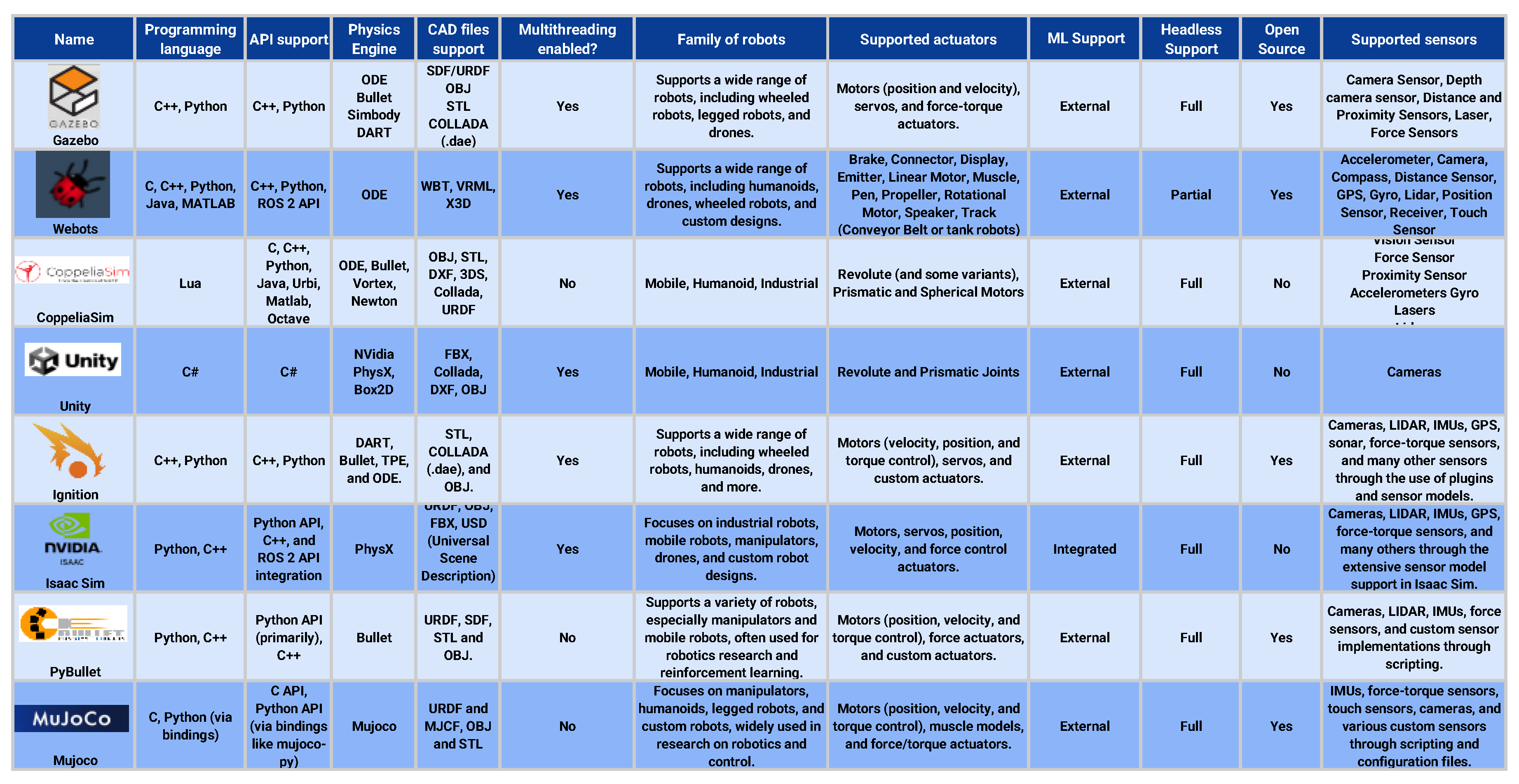

Simulation and visualization tools are integral to the development and testing of robotic systems. Gazebo and Webots are widely used simulators that integrate seamlessly with ROS 2, allowing for high-fidelity simulation of robots and environments. Gazebo supports complex physics simulations and is extensively used for testing algorithms in a controlled setting. Webots provides a user-friendly interface and supports a wide range of robotic platforms, making it ideal for both educational and research purposes.

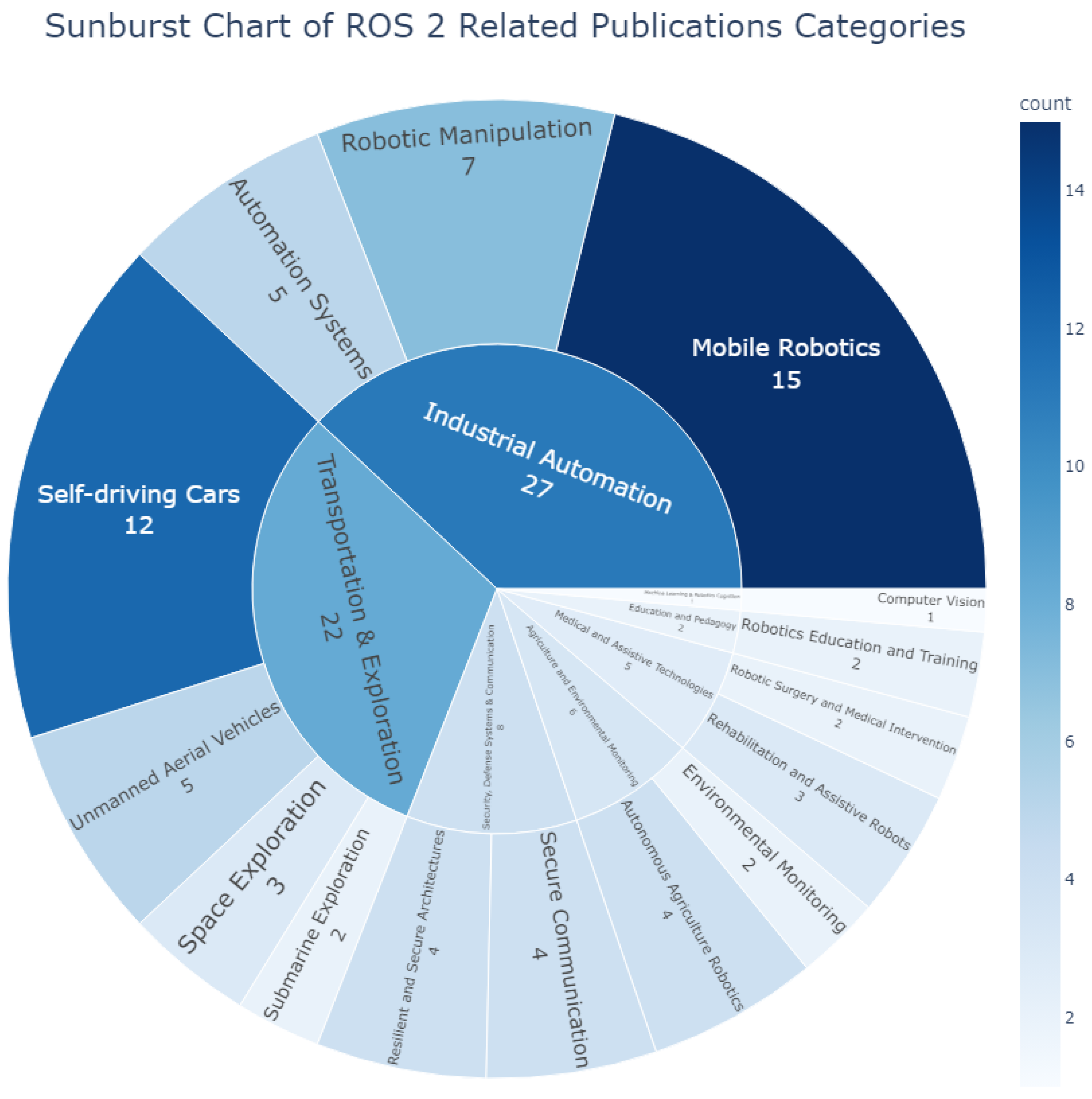

Figure 9 shows different simulators for ROS 2 along with different specifications.

Moreover, datasets generated using ROS 2 play a crucial role in training and validating machine learning models and other data-driven approaches in robotics. For example, Merzlyakov and Macenski [

181] compared modern visual SLAM approaches, while Amano et al. [

182] generated datasets for object recognition using FPGA nodes in ROS 2. Hallyburton et al. [

183] created a multi-agent security testbed, and Rosende et al. [

184] provided an urban traffic dataset for intelligent transportation systems. These datasets are crucial for benchmarking and improving the performance of various robotic applications.

Figure 8.

Taxonomy of different fields that utulizes ROS 2.

Figure 8.

Taxonomy of different fields that utulizes ROS 2.

Figure 9.

ROS 2 Simulators.

Figure 9.

ROS 2 Simulators.

Table 11.

Datasets and Tools Generated by ROS 2.

Table 11.

Datasets and Tools Generated by ROS 2.

| Title |

Authors |

Description |

| An Urban Traffic Dataset Composed of Visible Images and Their Semantic Segmentation Generated by the CARLA Simulator |

Rosende et al. [184] |

Urban traffic dataset for training computer vision algorithms |

| Are you a robot? Detecting Autonomous Vehicles from Behavior Analysis |

Maresca et al. [185] |

Dataset and framework for detecting autonomous vehicles |

| Co-driver: VLM-based Autonomous Driving Assistant with Human-like Behavior and Understanding for Complex Road Scenes |

[186] |

VLM dataset for Understanding for Complex Road Scenes |

| HawkDrive: A Transformer-driven Visual Perception System for Autonomous Driving in Night Scene |

Guo et al. [98] |

Visual perception system for night-time autonomous driving |

| Learning to Grasp on the Moon from 3D Octree Observations with Deep Reinforcement Learning |

[108] |