1. Introduction

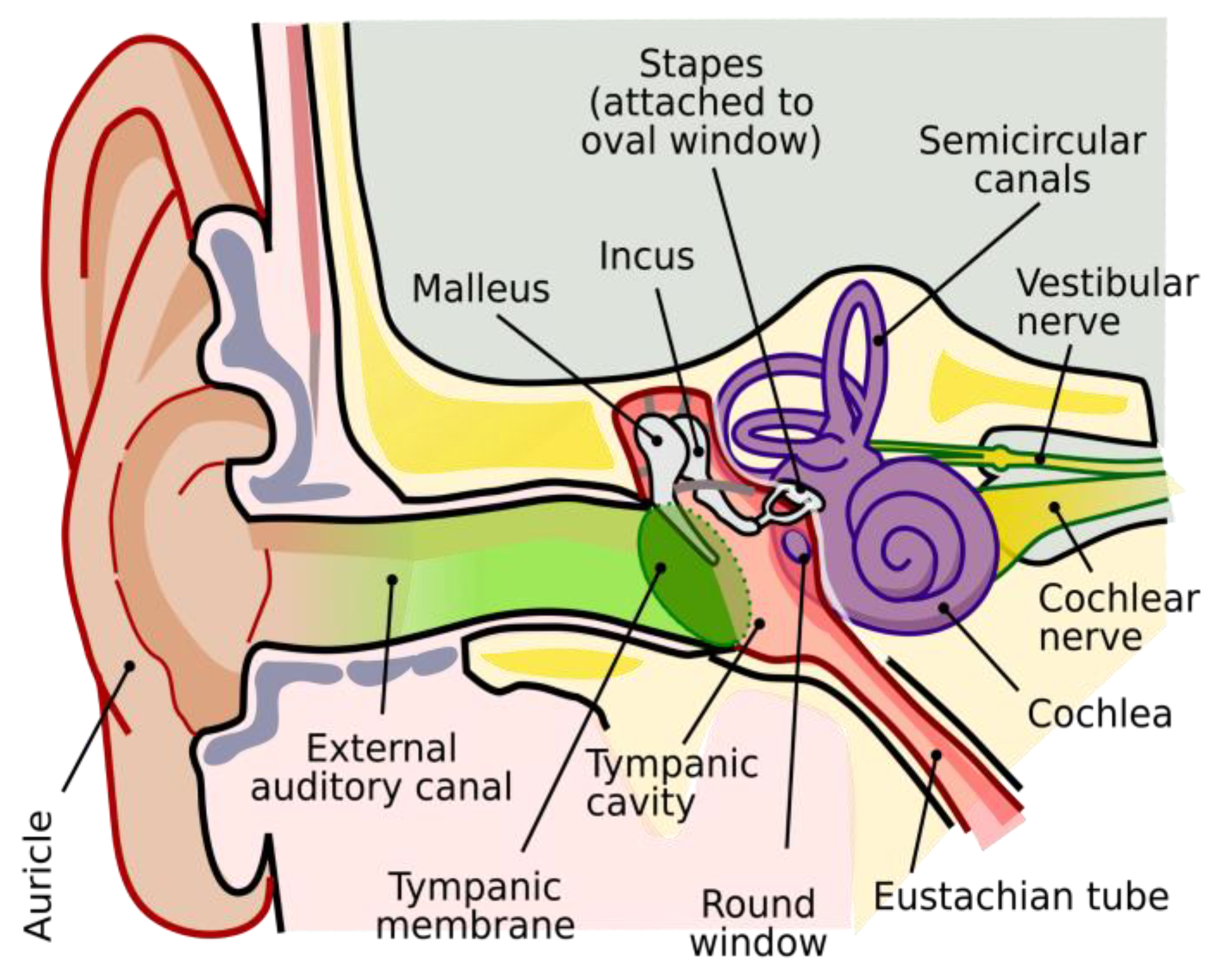

The human sense of hearing is an extraordinary capability, allowing us to perceive and interpret a vast array of sounds from the environment, from the subtle rustling of leaves to the nuanced tones of speech and music. Our ears are sophisticated biological sensor systems that transduce sound waves into neural impulses (

Figure 1). The ears and brain work in tandem to process these sounds effortlessly, enabling us to locate their sources, understand complex auditory signals, and even filter out background noise—all without conscious effort [

1]. This remarkable sense operates continuously, often unnoticed, as we navigate through our daily lives, taking it for granted as long as it functions normally. It’s only when our hearing is impaired that we begin to appreciate its vital role in our connection to the world around us.

Hearing loss may be the world’s largest pandemic that many fail to notice, care about or mention. According to the World Health Organization, a staggering 1.5 billion people globally suffer from some type of hearing loss (≥20 dB elevated hearing thresholds at audible frequencies) [

3]. Of these hearing-impaired population, nearly half a billion live with “disabling” hearing loss, meaning that to live a normal life, they require hearing assistance.

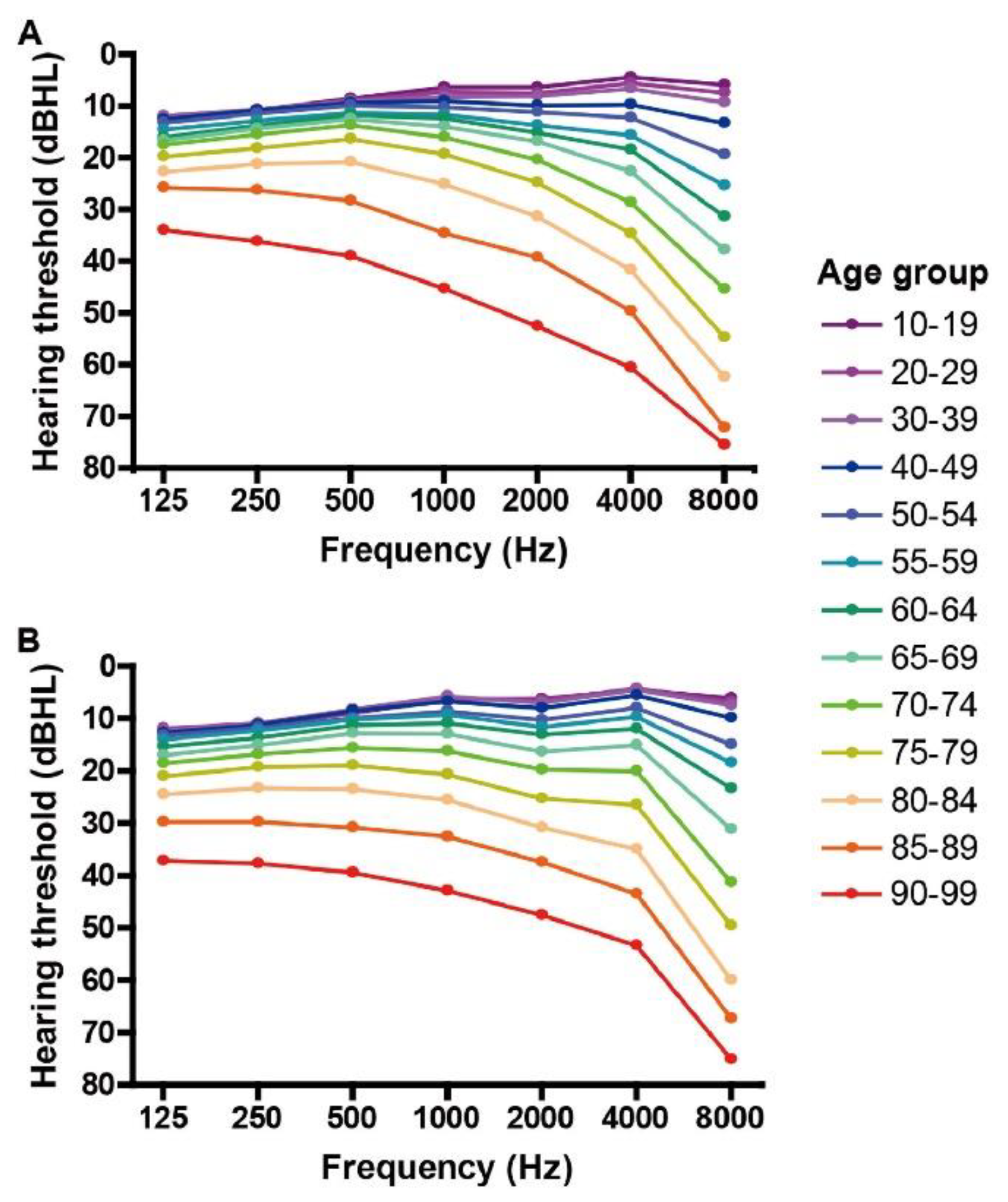

The prevalence of hearing loss, generally progressing with age, is a global phenomenon. A study on the prevalence of hearing impairment in the United States in 2019, according to age and severity, shows that approximately 30% of people in the age group of 50 to 59 years suffer from hearing loss, which increases to over 70% for the age group of 70 to 79 years, and exceeds 85% for people over 80 years [

4]. As another example,

Figure 2 shows the summary of a retrospective study of over 10,000 Japanese men and women, between 10 to 99 years of age, for their hearing loss evaluated by pure-tone audiometric tests spanning sound frequencies of 125 to 8,000 Hz [

5]. This study, published in the

Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, shows the steady progression of hearing loss with age, with worse hearing thresholds at higher sound frequencies in older ages.

Hearing loss, if left untreated, also has significant knock-on effects, or comorbidities. According to Hughes, et al., who conducted a comprehensive survey regarding the mental health impacts of hearing loss, untreated hearing loss forces those afflicted into social withdrawal, as they are therefore unable to participate in normal and routine conversations [

6]. That social withdrawal coupled with the other cerebral detriments of hearing loss, such as dementia, could be one of the most significant causes for cognitive decline in elderly people [

3,

6]. Outside of mental health, hearing loss also has a proven comorbidity with obesity and cardiovascular diseases, as hearing-impaired persons are more likely to not participate in social events, and therefore become highly sedentary [

7]. Patients with hearing impairment have been shown to suffer from increased risks of falls [

8]. Not only does hearing loss drastically undermine the health of the hearing-impaired individuals, but because of its detriments to cognition and intelligence, 1 trillion “international dollars,” are lost because of it yearly, according to the World Health Organization [

3]. Hearing loss, clearly, from a public health and economic perspective, could be one of the world’s most perilous conditions.

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is the most common form of hearing impairment, by some estimates accounting for nearly 90% of all hearing loss cases [

9]. The other 10% is conductive hearing loss (CHL) of which earwax buildup is the most common subset, in addition to pathologies of the tympanic membrane and the middle ear structures [

10]. Sensorineural hearing loss largely relates to either damages or de-innervation of the cilia hair cells that transform sounds to become understandable electrical signals that are relayed to the auditory cortex of the brain in the form of nerve impulses. Simply put, SNHL is derived from issues with the inner ear. Treatments for SNHL include both hearing aids and cochlear implants, but some estimates account for 80% of SNHL cases being treatable with hearing aids [

9]. These patients have hearing loss that ranges from mild up to severe, accounting for more than 1 billion people [

11]. The other 20% of SNHL patients could be cochlear implant candidates, that serve as an artificially innerved cochlea, implanted into the inner ear. Cochlear implants are a great solution for those who are severely or profoundly deaf, yet because of their narrow patient focus and significantly higher costs due to surgical procedures, they are not as ubiquitous as hearing aids [

9].

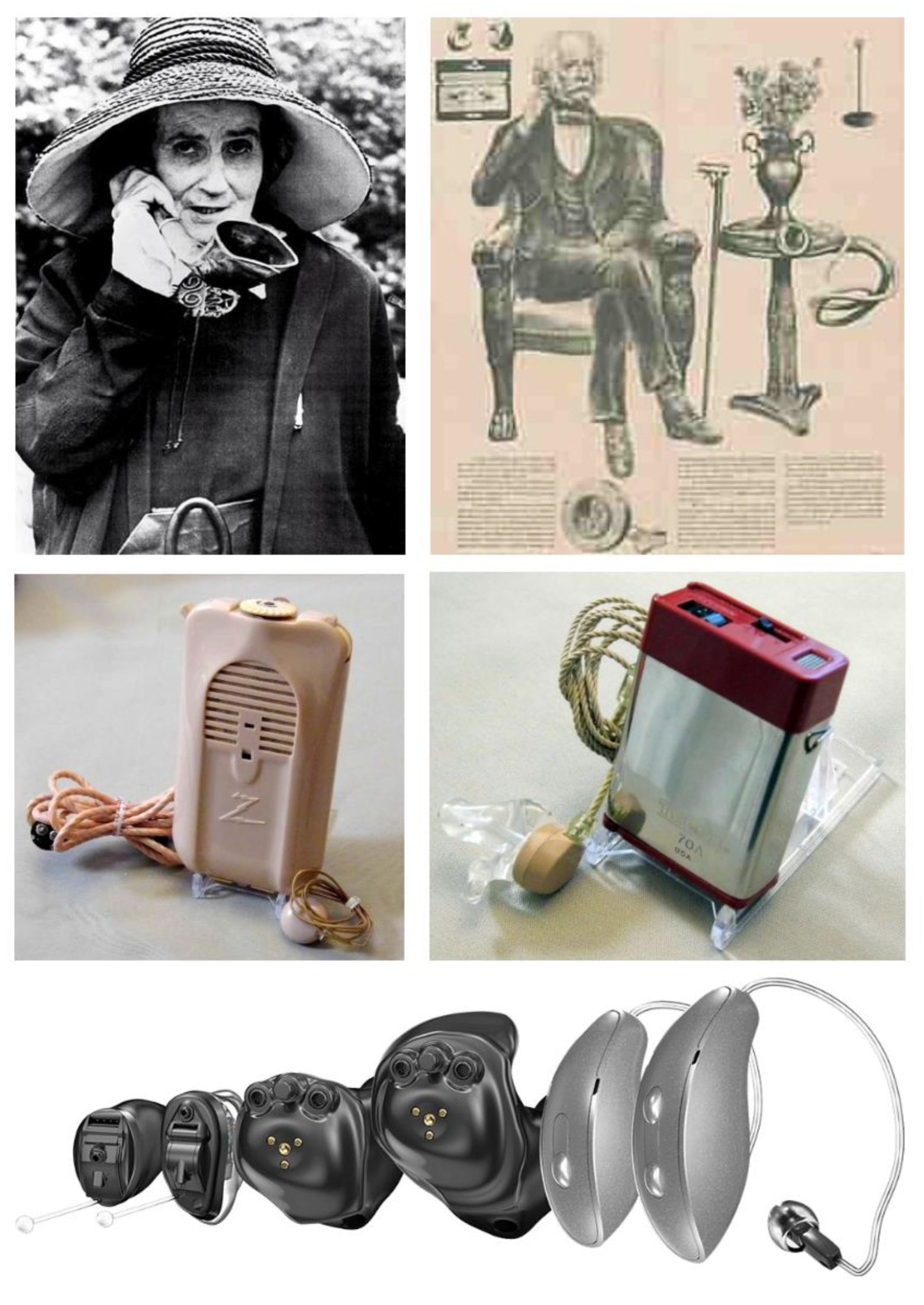

As depicted in

Figure 3, at their inception, hearing aids were rudimentary and mechanical systems, relying on passive amplification techniques. The ear trumpet of Madame de Meuron, for example, was a simple, funnel-shaped device that captured sound and directed it into the ear, while Frederick Rein's acoustic chair for King John VI of Portugal incorporated hidden sound-collecting tubes into a piece of furniture, allowing the user to hear conversations more clearly without the need for a conspicuous device. The mid-20th century marked a major milestone with the advent of body-worn hearing aids utilizing vacuum tube technology, a significant leap in portable amplification devices around 1940s. This was further refined by the 1970s with the introduction of transistor-based body-worn hearing aids, which offered greater miniaturization and efficiency.

Though the initial effects of these hearing aids seemed positive, an inability to distinguish signals (voices and other important sounds) from noise (everything else), made these hearing aids, and indeed many low-end digital hearing aids largely inadequate. Today’s state of the art hearing aids, however, are far more advanced than a rudimentary sum of its parts. Currently, hearing aids make use of digital signal processing techniques within the amplifier, making the sound passed on to the wearer far better and clearer. Also at their earlier iterations, hearing aids were large, obtrusive and were required to be worn on the body with wires connecting to the earpieces. Now, as all of the components that make up hearing aids have become far smaller, hearing aids can be made to be completely invisible inside the wearer’s ear canal in invisible-in-canal (IIC) designs, or nearly invisible form-factors such as completely-in-canal (CIC) and receiver-in-canal (RIC) styles, or more conspicuous designs such as in-the-canal (ITC), in-the-ear (ITE), or the traditional behind-the-ear (BTE) forms [

12].

In their most basic form, a hearing aid consists of a microphone, picking up sounds from the wearer’s environment and transforming them into electric signals; an amplifier, increasing the power of those signals and processing them; and a receiver, more commonly known as a speaker, playing those signals into the ear canal; and a battery powering the device [

12]. Modern hearing aid designs have refined these basic components into highly sophisticated, miniaturized devices that offer a range of customizable features and styles to meet individual needs. Advances in digital signal processing allow for precise amplification and noise reduction, while modern receivers deliver clearer, more natural sound. Additionally, contemporary hearing aids often incorporate wireless connectivity, enabling seamless integration with smartphones and other devices [

13].

Unfortunately, many people delay seeking help until their hearing impairment severely impacts their daily life, despite the availability of hearing aids that can enhance communication, social interaction, and overall well-being. This gap underscores the need for increased education, accessibility, and support to encourage more individuals to take advantage of the hearing solutions available to them. According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, a surprisingly small percentage of Americans who could benefit from hearing aids actually use them, with estimates ranging from just 16% to 30% [

14]. This disparity highlights a significant public health issue, as millions of individuals are missing out on the improved quality of life that hearing aids can provide. The reasons for this low adoption rate are multifaceted, including social stigma, cost barriers, lack of awareness, and a general reluctance to acknowledge hearing loss as a problem. In this paper, we review the historical stigma associated with hearing aids and examine the ways to alleviate it with improvements in designs and increased functionalities.

2. Survey of Prior Research

The body of research on hearing aid stigma offers a comprehensive understanding of the various factors contributing to the non-adoption or underuse of hearing aids, despite their potential to significantly enhance quality of life. In this section, we will review key studies that have systematically analyzed the social, psychological, and technological dimensions of hearing aid stigma.

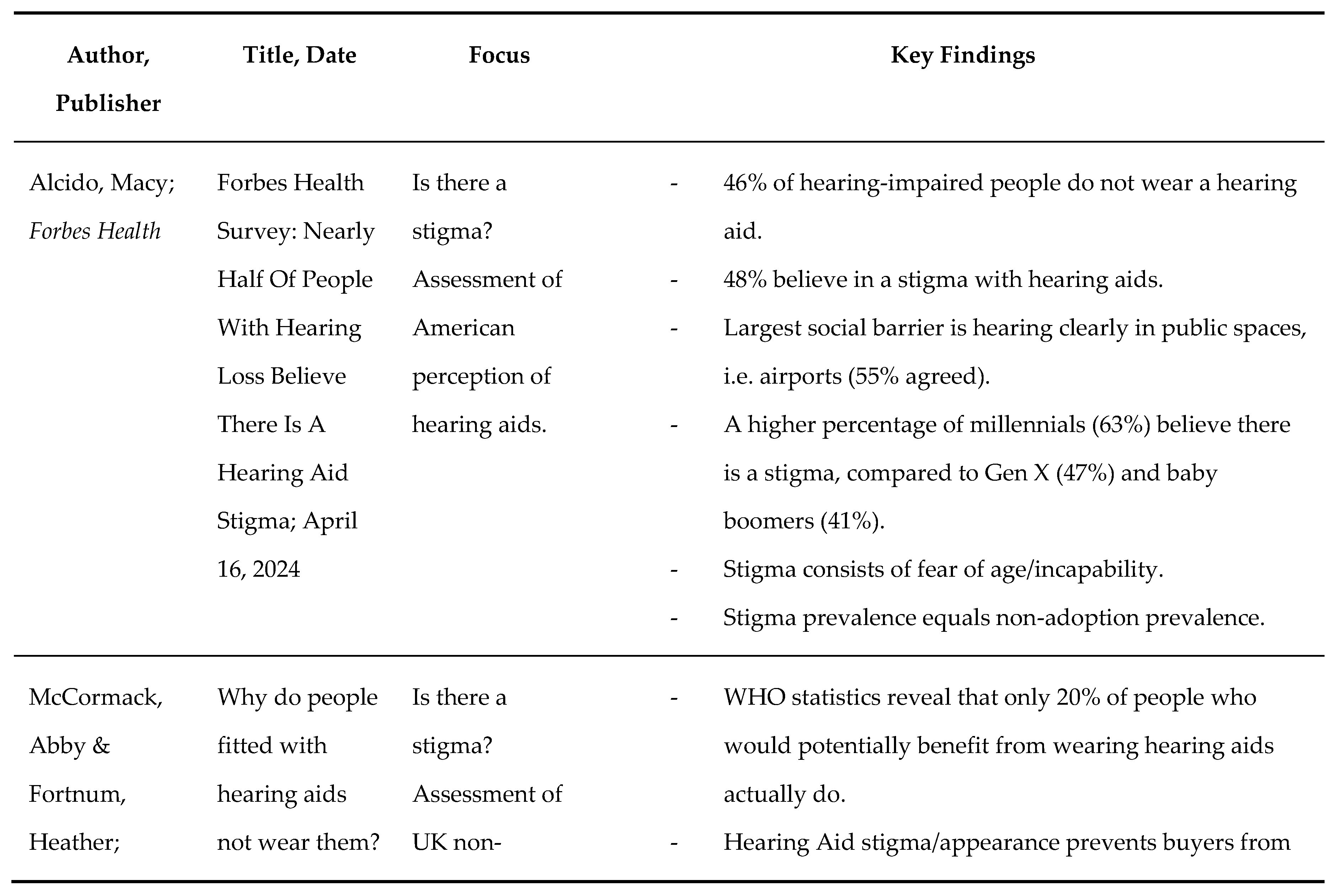

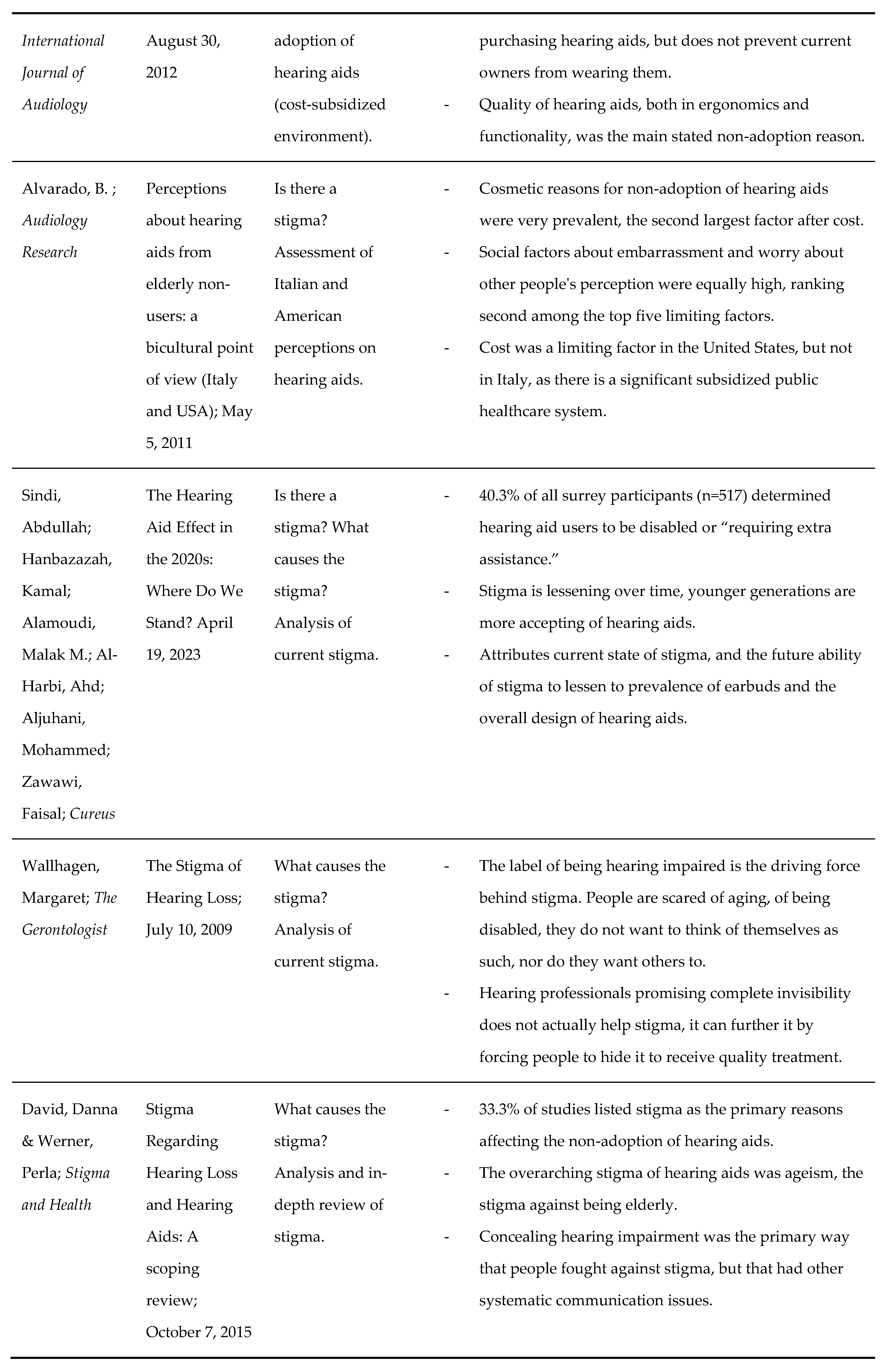

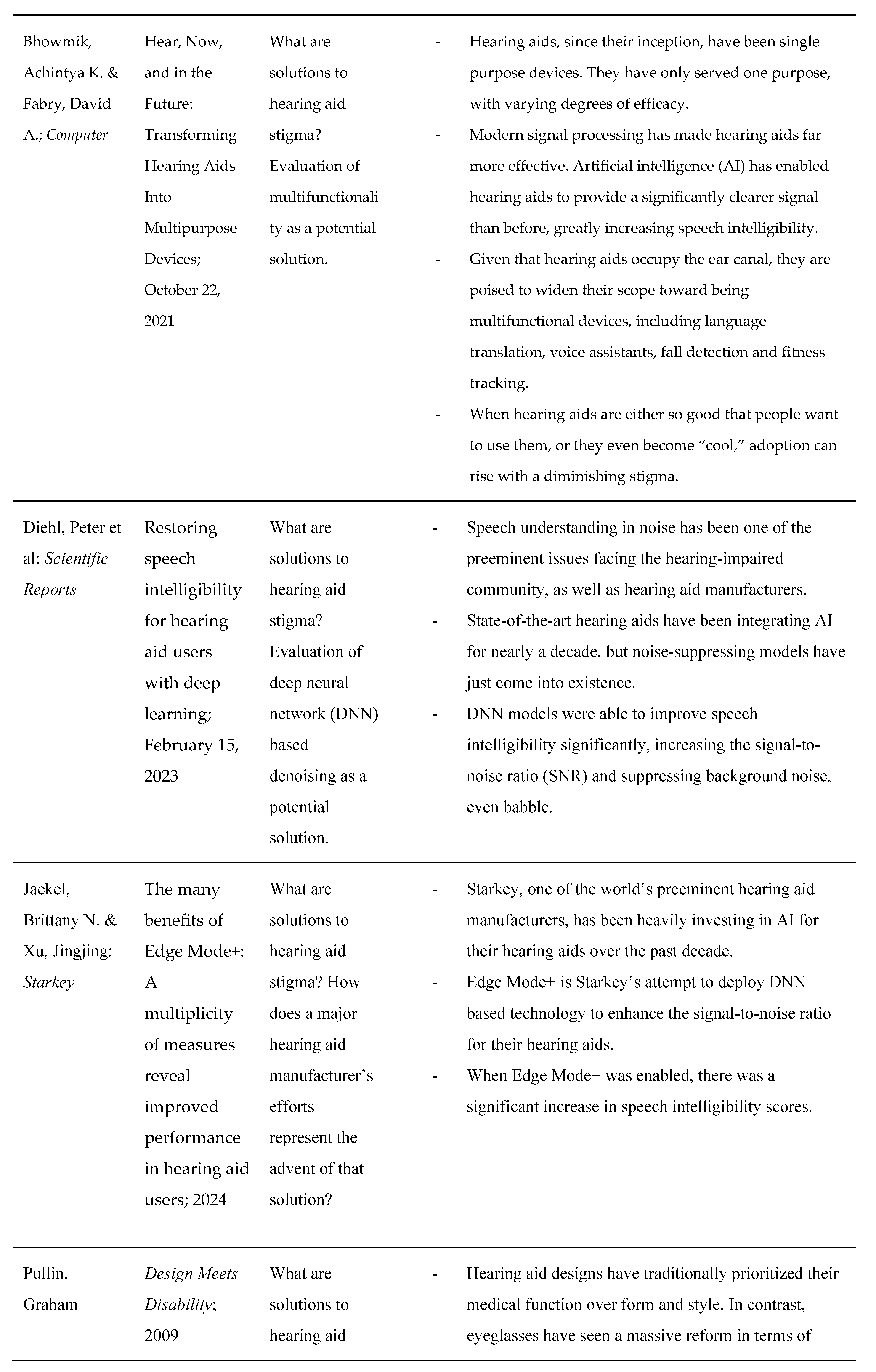

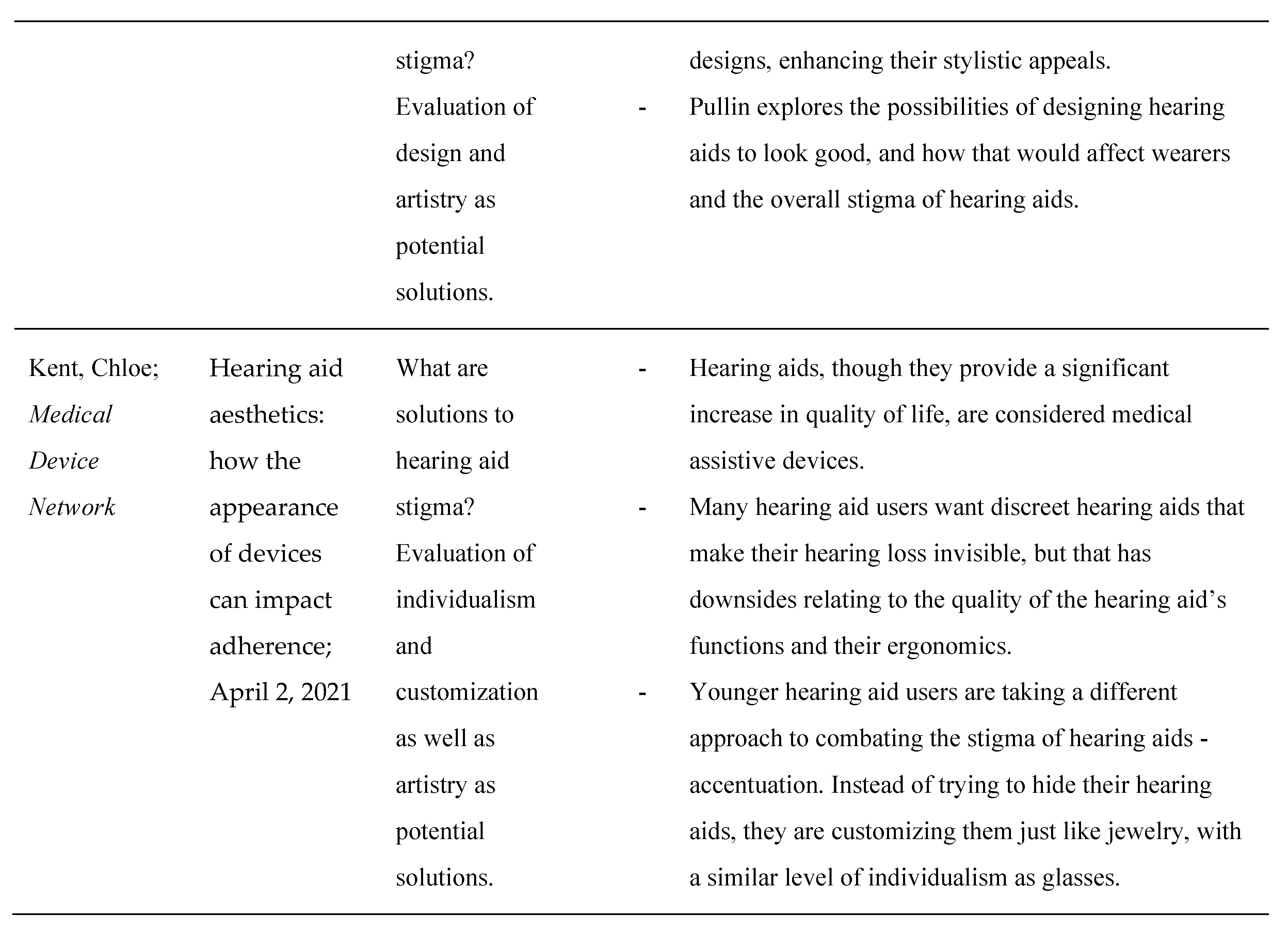

Table 1 provides a summary of notable research works, organized by authors, publication details, and their focus areas. These studies provide insights into both the causes of stigma—such as ageism, perceptions of disability, and concerns about aesthetics—and explore potential solutions, including advancements in technology and design. This survey aims to contextualize the current state of hearing aid adoption and identify pathways to reducing the associated stigma.

2.1. Is There a Stigma?

In short, yes, the surveys reveal that there continues to be a stigma associated with hearing loss as a whole, but especially regarding hearing aids as the main solution to hearing loss. A multitude of papers, spanning two decades, and multiple continents, state stigma as either the primary cause of hearing aid non-adoption or one of the leading causes.

Most recently, Mary Alcido, writing for

Forbes Health, conducted a survey on the limited adoption of hearing aids [

15]. She concluded that 46% of hearing-impaired people do not wear a hearing aid. More pertinently, however, out of the entire survey pool, 48% of people believed that hearing aids are stigmatized. The stigma, Alcido noted, was rooted in a fear of aging and incapability (i.e. people do not want to be perceived, nor do they want to perceive themselves as old or disabled). Importantly, and optimistically, however, the

Forbes survey also demonstrated that hearing aid stigma was less prevalent in younger generations, indicating that the stigma could naturally decrease over time.

As somewhat of a foil to Alcido’s survey, Abby McCormack and Heather Fortnum’s 2012 study for the

International Journal of Audiology as well as Beatriz Alvarado’s 2011 article for

Audiology Research were also reviewed [

16,

17]. Those papers offered an international and historical insight into hearing aid stigma to examine its evolution and global expanse. These two research works were conducted through rote mathematical anthropological analysis. McCormack and Fortnum observed current hearing aid users in the United Kingdom. Though they found quality to be the greatest inhibitor to regular use for users who already owned hearing aids, they found that stigma was the largest barrier to purchasing hearing aids in the first place. Alvarado compared hearing aid users in the United States and Italy. Though they found cost to be the largest barrier, cosmetic and social reasons for hearing aid non-adoption (all of the individual factors that make up stigma), occupied more of the highest-ranked positions overall. Additionally, cost was only a factor in the United States, as Italy has a large public healthcare system subsidizing hearing aids.

In a larger and more quantitative approach to hearing aid analysis, Sergei Kochkin’s examination of the MarkeTrak VII survey on hearing loss also saw stigma to be a significant inhibitor [

18]. Kochkin concluded that “nearly half (48%) indicated that stigma contributed to their desire not to wear hearing aids.” Apart from cost and perceived lack of need, which could also be attributed to stigma, stigma alone was the largest factor relating to hearing aid non-adoption. Additionally, though her paper is more poignant when examining what causes the stigma of hearing aids, one quotation from Margaret Wallhagen’s 2009 paper discussing the stigma of hearing loss as a whole is highly important to evaluating the presence of stigma [

19]. She found that “even if hearing aids were given away by the government at no cost to the user, 65% of the hearing-impaired population would decline the offer.”

2.2. What Causes the Stigma?

As a distinctly psychological and sociological issue, there are many factors and facets of hearing aid stigma, yet all of these factors can be roughly categorized as systemic and societal ageism and ableism.

Though Abdullah Sindi (et al)’s paper for

Cureus Journal does provide a wide overview of hearing aid stigma, it also provides analysis on the stigma, differentiating it from the articles above [

20]. Sindi et al presented their participants (n=517) with various pictures of hearing people, and hearing-impaired people, who were hearing aid users, and asked them if they believed that the hearing-impaired people seemed disabled or “required additional assistance.” They found that 40.3% of people (n= ~208) believed that hearing aid users fit the aforementioned description. Their survey thus points toward ageism as a root cause of the stigma. Just like the

Forbes Health survey, Sindi et al also optimistically claim diminishing stigma amongst younger generations. They attribute that transition to the prevalence of earbuds and the future designs of hearing aids.

Margaret Wallhagen’s 2009 paper entitled “The Stigma of Hearing Loss,” is one of the seminal articles relating to its namesake subject, though it is somewhat dated [

19]. Wallhagen attributes the stigma, simply to the label of being hearing-impaired, as well as the convention of hiding a hearing impairment, in pursuit of a solution. She claims that hearing aid professionals who constantly push hearing aid discretion and invisibility could actually be empowering the stigma of hearing aids instead of their patients.

In a 2015 review article not dissimilar to this paper, Danna David and Perla Werner examine all of the surveys surrounding hearing aid adoption [

21]. They found that 33.3% of all surveys listed hearing aid stigma as the primary reason for non-adoption. Just like Wallhagen, they found that ageism and the pursuit of concealment were the main causes behind stigma.

2.3. How Can the Stigma Be Alleviated?

Though this point will be further elaborated in the analysis and discussion portions of this paper, hearing aid stigma can be categorized as observed or perceived. Observed stigma is impacted by design, and perceived stigma, which could be categorized as the “crowded room effect,” is affected by functionality.

Graham Pullin’s book,

Design Meets Disability, is an important resource to consider when assessing design and its impact on observed stigma of hearing aids [

22]. In the book, Pullin explores the impact of industrial designs and color palettes from popular consumer electronic devices, and how that might affect the stigma of hearing aids. Pullin also provides an anecdote of a teenager wearing a bright white, ostensibly visible hearing device, and how confident he seemed comparatively.

Chloe Kent, in a 2021

Medical Device Network article, also explores the potential for the intersection of design and hearing loss, however differently from Pullin [

23]. Kent advocates for individualism and customization of hearing aids, similar to glasses. She claims that it is far more important, for the sake of eliminating hearing aid stigma, to make hearing aids look

good than to make them invisible, especially if invisibility trumps functionality. She also says that younger generations are especially attuned to this kind of design independence from the medical world.

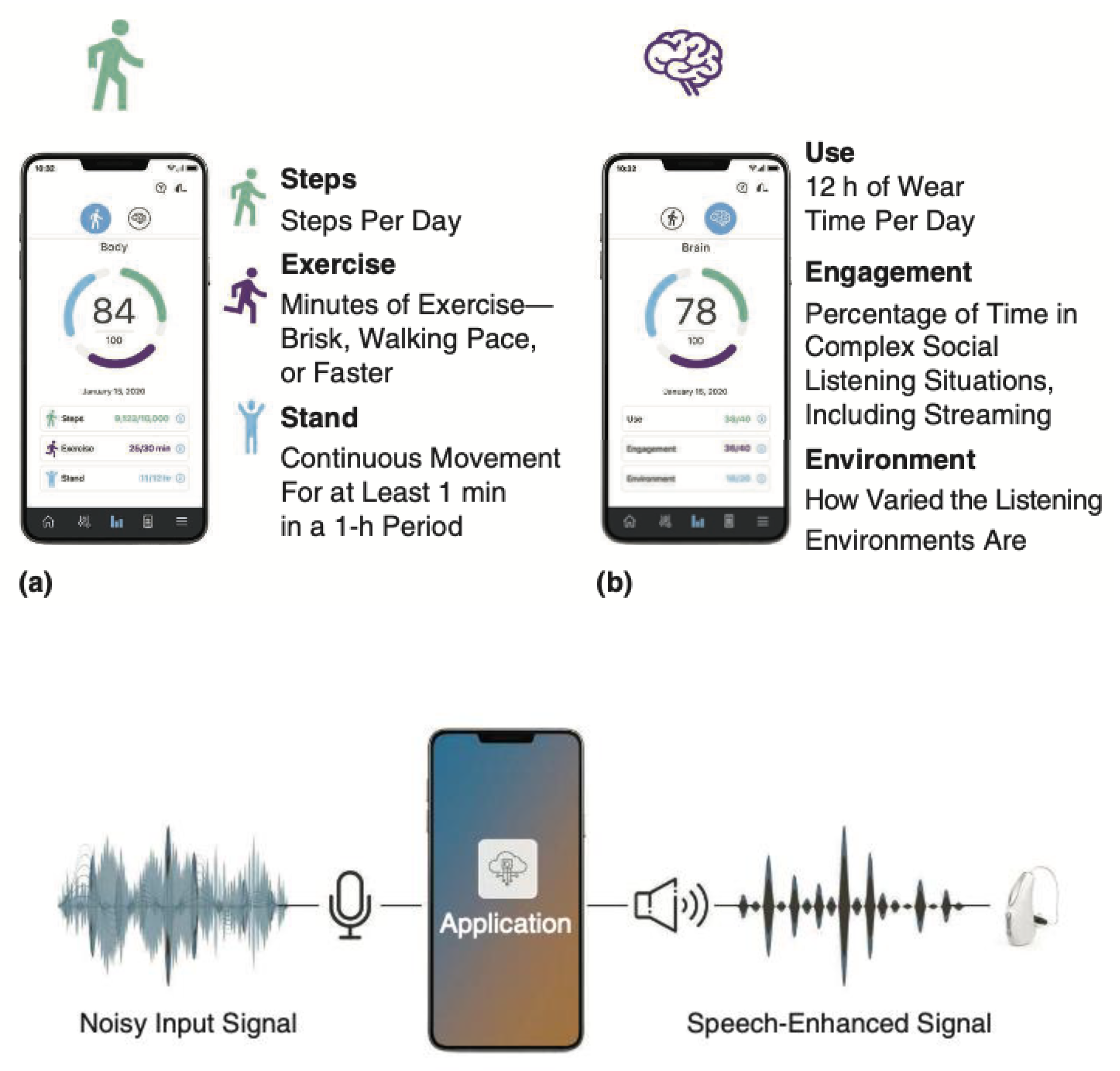

Bhowmik and Fabry, in an

IEEE Computer article, outlined the path forward for hearing aids to become multifunctional devices, transcending their primary purpose of amplifying sound [

13]. The computational processing power in modern hearing aids has become so advanced, and the connectivity to the cloud so pervasive, that they are able to integrate fall detection and fitness tracking sensors, language translation capabilities, and virtual assistants into the hearing aids. The scope of multifunctionality is that hearing aids can become devices that people want to wear instead of have to wear.

Artificial intelligence has significant capabilities within the audio world. In two papers, one scientific and the other clinical, Peter Diehl et al writing for

Scientific Reports and Brittany Jaekel and Jingjing Xu in a Starkey Hearing whitepaper, assess the potential of deep neural network (DNN) based denoising algorithms as a major improvement in hearing aid performance and functionality [

24,

25]. They found that that incorporating DNN algorithms was able to reliably improve speech intelligibility scores, by increasing signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs). In short, DNNs are a significant potential solution to hearing loss affecting the ability to understand speech in noisy environments. Just like in the

Scientific Reports trial, Starkey's work found success in speech intelligibility improvement when the DNN algorithms were enabled.

4. Conclusions

Hearing aids have undergone remarkable advancements in recent years, transforming from rudimentary sound amplification tools into sophisticated, multi-functional devices that utilize artificial intelligence to enhance sound quality and offer additional features like fall detection, physical activity and social engagement tracking, and even language translation. Despite these innovations, the adoption rate of hearing aids remains strikingly low, with a very small fraction of people who need them actually using them.

In this paper, we have examined the pervasive stigma associated with hearing aids, which continues to be a significant barrier to their widespread adoption. We have explored how the stigma—both observed and perceived—can be alleviated by improving the design and functionality of hearing aids. By drawing parallels with the evolution of eyeglasses, which successfully transitioned from a stigmatized necessity to a fashion statement, this paper argues that hearing aids can similarly overcome their negative perception. By integrating multiple functions besides design improvements, hearing aids can transform into must-have health and communication devices that many would want to wear. The discussion also emphasizes the importance of public awareness and education in reducing stigma and increasing acceptance of hearing aids, ultimately aiming to improve the quality of life for millions of individuals with hearing loss.

As hearing aid designers continue to create products that both look better and perform better, both the perceived stigma of wearing them and the observed stigma of being “disabled” will be reduced, paving the way to a world where hearing-impaired people are not discriminated against for wanting a better quality of life. As that happens, one of the world's largest pandemics, comprising one-fifth of the world’s total population, can be improved and those afflicted can receive the hearing care that they require and deserve.