1. Introduction

Blood group antigens are sugars or proteins attached to red blood cell (RBC) membrane. Antibodies are immunoglobins produced by lymphocytes and plasma cells following antigen stimulation and found in serum or in body fluids. They can be demonstrated, serologically. Antibodies against red blood cells can be natural (e.g. Anti-A, Anti-B) or immune immunoglobulins (e.g. Anti-D or Anti-Fya). The former are IgM class with large molecular weight, capable of binding complement cascade and causing intravascolar hemolysis, the latter are immunoglobulin IgG, capable of crossing the placenta and causing hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN) [

1,

2].

Some of blood group antibodies are agglutinins, whereas others are hemolysins. Many factors influence antigen-antibody reaction, such as temperature, incubation time, pH, ionic strength of environment, zeta potential between red cells, concentrations of antigen and antibody, effect of centrifugation [

1,

2].

Hemoagglutination occurs when IgM react with their corresponding red cell antigens, sensitization occurs when IgG react with their red cell antigens. The latter is not an observable reaction without potentiators such as Antihuman globulin (AHG) which contains IgG and complement fractions. Hemolysis is the result of antigen-antibody reaction that utilizes the complement proteins to mediate red cell membran attack and lysis [

1,

2].

The indirect antiglobulin (Coombs) test is used to determine whether serum or plasma contains IgG antibodies (antibody screen) and their identification. The sensitization of red cells is observed in vitro by incubating the red cells with the corresponding antibody from patient serum or plasma at 37 °C for 30 minutes, with or without potentiators (eg enzymes, low-ionic-strenght solution) [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Antibody formation against non-self-antigen on red blood cells may occur after transfusions, pregnancies or other exposures. Multiple triggers for red blood cell alloimmunization include donor and recipient factors (eg ethnicity, clinical conditions) and red blood cell factors (eg antigen variants, immunogenicity) [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

The RBC alloimmunization rates varies from 2% to 6% according to recent studies. The Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study-III (REDS-III) which included 319.177 recipients, recognized that older age, female sex, Rh (D) negative status, hemoglobinopaties and autoimmune disorders were risk factors for alloimmunization [

10].

RBC transfusion is a key component of therapy for medical and surgery patients and for chronic treatment of hematologic malignancies and hemoglobinopaties. After exposure to non-self-protein or non-self-carbohydrate of RBCs, B cells are activated from primary to secondary immune response. The former is T-cell independent, slow and weak response and the latter is T-cell dependent, strong and rapid response [

9].

Considering the complex interaction between donor and recipient, genetics of blood group antigens and clinical conditions further studies are necessary to better analyze the risk factors for alloimmunization and improve the ability to supply compatibile red blood units [

6].

2. Materials and Methods

A type and screen sample, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) anticoagulant, is commonly submitted to the blood bank with a request of units of red blood cells.

The antibody screen is performed by mixing patient’s plasma or serum with three reagent red cells of blood type O, to detect non-ABO antibodies. These reactions are incubated, centrifuged and interpreted based on the degree of agglutination (from 0 to 4+, no reaction versus strong reaction).

A negative antibody screen suggests absence of antibodies or that they are undetectable. In case of positive antibody screen, an antibody panel of 11 reagent red cells of blood type O is provided to detect non-ABO antibodies. Assigning presumptive antibody specificity is useful to select appropriate red blood units and determine compatibility of donor red cells with patient’s serum or plasma (major crossmatch).

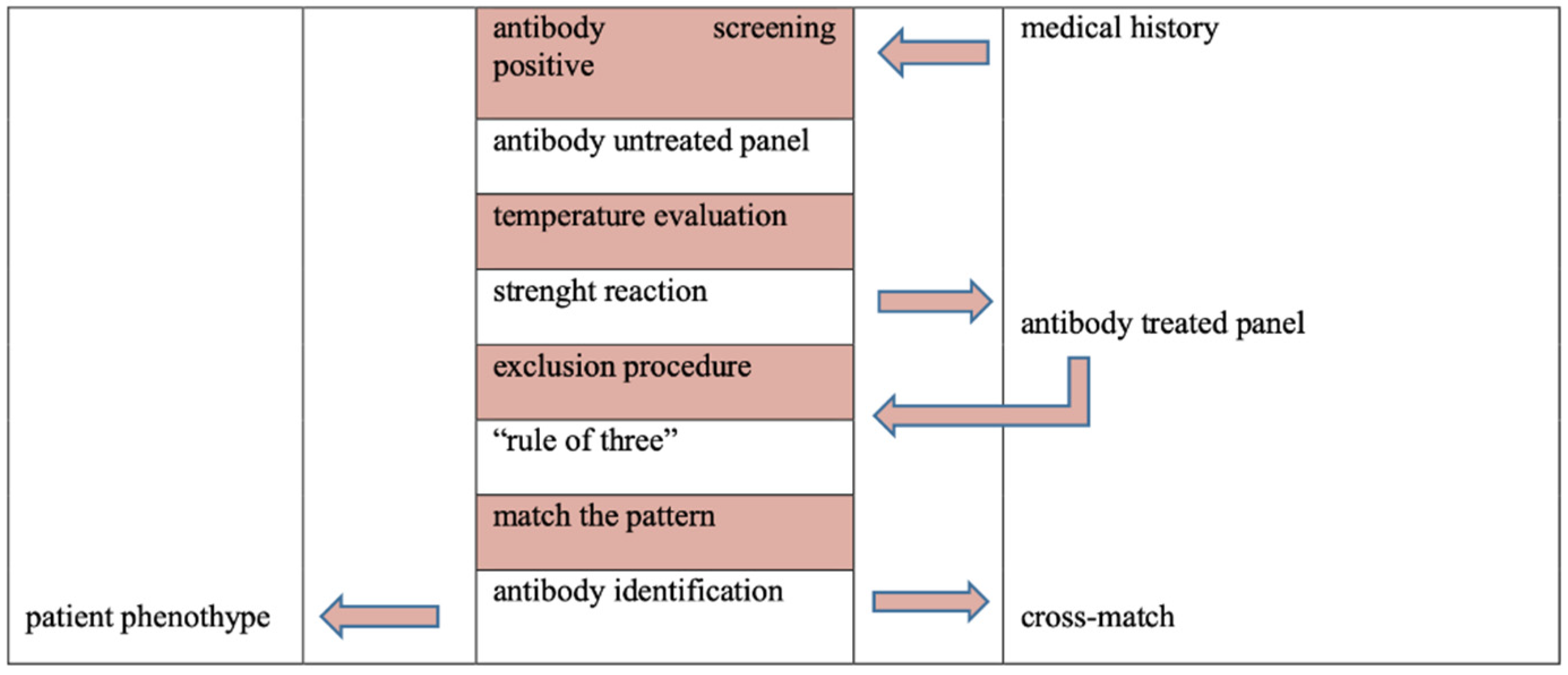

The antibody identification is a multistep process [

4,12]. Firstly, is important temperature evaluation of antigen-antibody reaction (for example, reaction at 37°C suggests clinically significant IgG antibody), strength reaction (for example, different scores of hemoagglutination may be due to multiple antibodies or antibody with dosage) and second, cross-out antibody properly.

More specifically, an exclusion procedure is based on observation of antigens present on RBC reagent of the panel with which patient serum or plasma did not react. For antibodies which demonstrate dosage (Rh excluding D, Kidd, Duffy, MNS blood groups) caution should be exercised when ruling out panel cells that have homozygous antigen expression.

Furthermore, cross-out antibody to the following antigen D, C, E, c, k, M, N, S, s, Fya, Fyb, Jka, Jkb is based on a minimum of two non-reactive cells with homozygous antigen expression, while exclusion of anti-K is based on one non-reactive cells with homozygous antigen expression or two non-reactive cells with heterozygous antigen expression [

4,12].

Ultimately, it is important detect three antigen-positive cells to be reactive and three antigen negative cells to be non-reactive to assign presumptive antibody specificity (“Rule of Three”), match the pattern of reaction and confirm correlation with patient’s phenotype (

Figure 1) [

4,12].

Autocontrol tests the patient’s serum or plasma with own red cells to exclude autoantobodies, drug interaction, transfused cells sensitized with antibodies [

4,12].

3. Results

Example 1

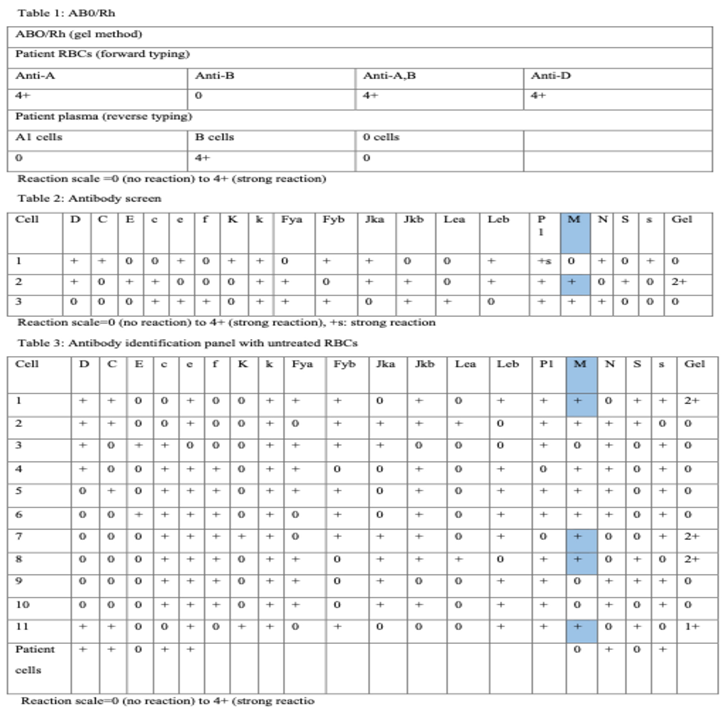

Table 1 represents ABO/Rh type. Forward type of the patient’s sample using gel method (microtube filled with gel particles) and reagent Ant-A, Ant-B e Anti-A, B indicates that the patient’s group is A. Reverse type of the sample (using A1 cells, B cells and O cells) confirms that anti-B isoantibodies are detected in the plasma. Testing with reagent anti- D recognizes that the Rh(D) is present on the patient’s red cells. Therefore, patient’s group is A Rh-positive.

Table 2 summarizes antibody screen using gel method. Alternatively, the reaction may be performed using tube test or solid phase technology.

Table 3 summarizes antibody identification panel using gel test with untreated RBC reagents.

Anti-M antibody can be identified and other clinically significant alloantibodies can be ruled out [

11,

12]. This antibody is active at 37°C and expresses a dosage effect. In fact, the reaction is stronger with homozygous M antigen cells than with eterozygous M antigen cells (M+N- reagent red cells versus M+N+ reagent red cells). Most antibodies to M antigen are cold reacting and they are not considered clinically significant. Dithiothreitol (DTT) is a reducing agent used to differentiate IgM and IgG reactivity of the antibody. This case, suggests a warm reacting alloantibody anti-M [

13,

14,

15,

16].

RBC units can be provided compatible through indirect antiglobulin test (IAT). In addition, serologic phenotype may confirms identification of the antibody. In case of pregnancy, IgG alloanti-M should be confirmed using different method such as tube test or solid phase technology and anti-M titer should be monitored for prevention of hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn [

17].

Example 2

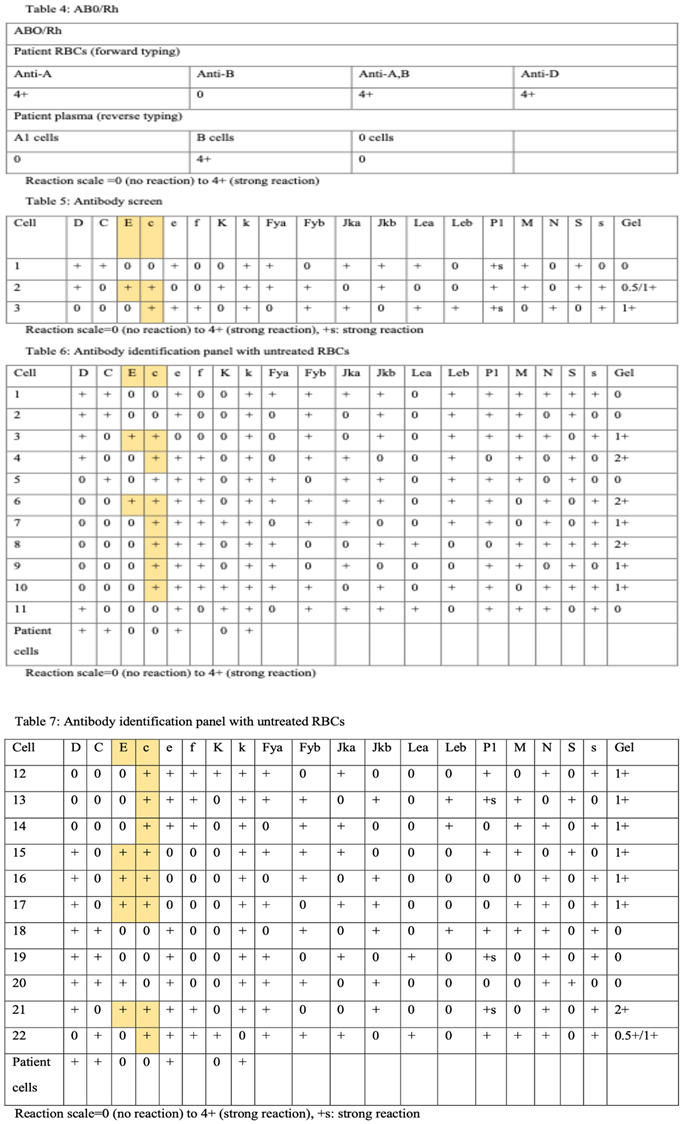

The patient’s group is A, Rh (D) pos using gel method (Table 3). Table 4 represents antibody screen. Table 5 and Table 6 summarize antibody identification panel using gel test with two different untreated RBCs.

Alloantibodies against the Rh (D) is confirmed in gel panel.

Anti-c and Anti-E can be identified and all other clinically significant alloantibodies can be ruled out (Table 5). 12,13 Rh blood group system antibodies are commonly observed after transfusion or pregnancy. They show specific characteristics; most are IgG, bind at 37°C indirect antiglobulin test (IAT). Some Rh antibodies may be found in individual who never pregnant (Anti-Cw) or never undergone transfusion (Anti-E). After alloimmunization, antibodies may persist for several years [

18,

19,

20].

Furthermore, the Rh(c) antigenic is more immunogenic than Rh(E) antigen and they may cause severe HDFN. Interestingly, a variety of strength reactions may suggest the presence of multiple antibodies [12].

A low titer of anti- E and Anti-c were recognized using gel method. Potentiators such as enzymes or more sensitive method of antibody identification may be used in case of weak reactions. Ultimately, c-negative and E-negative blood unit should be provided and crossmatched [12].

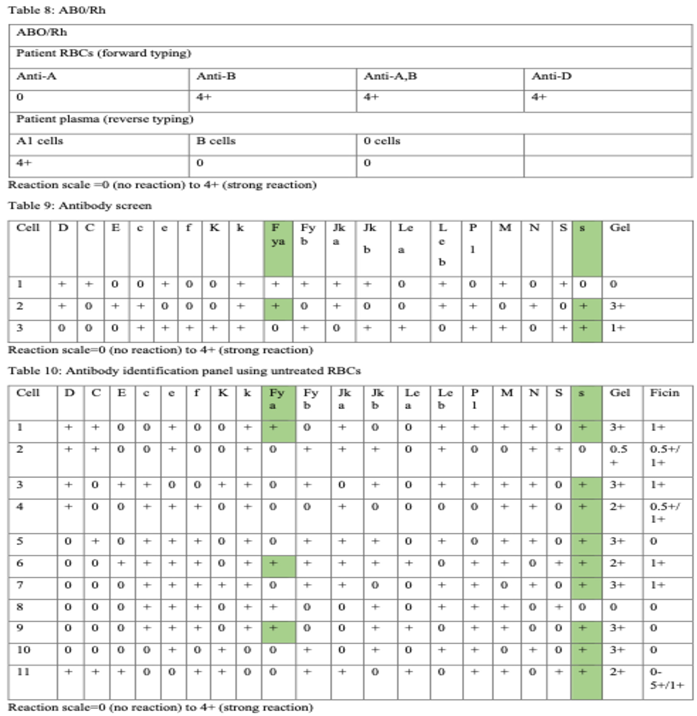

Example 3

The patient’s group is B, Rh (D) pos using gel method (Table 7). Table 8 represents antibody screen. Table 9 and Table 10 summarizes antibody identification panel using gel test with untreated RBCs and enzyme (ficin) treated red blood cells.

Multiple antibodies need a selected reagent panel red blood cells and additional techniques such as enzymes. More specifically, antibody reactions are enhanced using enzymes in Rh, P1, I, Kidd, Lewis blood groups. Antigens destroyed by enzymes are M, N, Duffy. The Kell blood group is unaffected by enzyme (ficin) reagent. S and s antigen present a variable effects on enzymes [

11,12].

Alloantibodies against the Fya and s are confirmed in gel panel and all other clinically significant alloantibodies are rule out (Table 6) [12]. Duffy antibodies are observed after acute and delayed transfusion reactions and are uncommon cause of HDFN. Anti-Fya is IgG, it usually does not usually bind the complement proteins. The antibody is classically non-reactive with ficin-treated RBC reagent because the enzyme degrades the antigen. Anti-s, is clinically significant IgG antibody that can induce hemolysis and HDFN. Anti- s shows a variable effect after ficin-treated red blood cells [

4,

21].

Fya-negative and s-negative red blood units should be provided and crossmatched for trasfusion request. Matching the pattern is more difficult when more than one antibody specificity exists [12].

4. Discussion

One of the most important process in transfusion medicine is management of patients who has red cell single or multiple alloantibodies.

The antibody screen is performed to identify or confirm the presence of antibodies in patient’s serum or plasma, as a preoperative and pretransfusion tests. Antibody identification and major crossmatch are provided using indirect antiglobulin test (IAT) to improve safety of red blood administration (

Figure 1).

The antibody screen is summarized in Tables 2, 5 and 9. The antibody panel is summarized in Tables 3, 6, 7 and 10. The three examples describe significant single and multiple alloantibodies in clinical practice.

Anti-M documented in first example is a possible warm reacting antibody. For decision making during pregnancy it is of paramount importance obtaining a complete transfusion history and monitoring antibody titer accurately.

Alloantibodies to Rh antigen is observed in the second example. Potentiators such as enzymes or a more sensitive method of antibody identification are necessary to increase weak reactions.

Anti-s recognized in last example is IgG and reactive at 37 °C. Similiarly, Anti- Fya is immonogenic and known to cause hemolytic reaction and HDFN. Duffy sistem includes antigens such as Fya and Fyb. Caucasian individuals express some combination of Fya and/or Fyb, while blacks may express neither antigen. Eventually, it is important to collect information regarding ethnicity, because it can expedite search of red blood units and supply of compatibile products.

5. Conclusions

The transfusion staff recommend red blood units units for transfusion request based on medical history and immunohematology tests (blood group, antibody screen and identification). In case of unavailability of suitable red blood cell units for transfusion purposes, communication between transfusion specialist and clinician is of paramount importance to plan further laboratory tests, search of red blood units and manage patients properly [

22,

23,

24,

25].

Acknowledgments

The autor thanks Dr Tommaso Granato Chief of Immunohematology and Transfusion Medicine, Policlinico Riuniti of Foggia and Dr Luciano Lombardi, MD at Immunohematology and Transfusion Medicine, Policlinico Riuniti of Foggia for their mentorship. The autor is grateful to Dr Valeria Elisena Cardo, MD at Poison Control Center, Policlinico Riuniti, University of Foggia for discussion that served to strengthen the manuscript. The author thanks all colleagues from Blood Bank Dr Filomena Sportelli, Dr Grazia Roberti, Dr Luigi Ciccone, Dr Antonietta Faleo, Dr Antonucci Francesco, Dr Lucia De Feo, Dr Libera Padovano, Dr Maria Lucia Mascia, technicians and nurses for their key observations. The author is grateful to Dr Elvira Schiavone, Dr Antonietta Ferrara, Dr Ferruccio Zaccaria, Dr Rocchina Altieri, Dr Lucia Simone MD at Clinical Pathology Laboratory, Policlinico Riuniti di Foggia for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Daniels, G. Human blood groups. 2nd Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Science; 2002.

- Reid ME, Lomas-Francis C, Olsson ML. The blood group antigens factsbook: Academic Press; 2012.

- Yamamoto, F. (2004). Review: ABO blood group system--ABH oligosaccharide antigens, anti-A and anti-B, A and B glycosyltransferases, and ABO genes. Immunohematology, 20(1), 3–22.

- Denise, M. Harmening, Modern Blood Banking and Transfusion Practices. 7th ed., Ch. 9. United states of America: F.A. Davis company Publication 2019. p. 232-248.

- Hendrickson, J. E., & Tormey, C. A. (2016). Understanding red blood cell alloimmunization triggers. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program, 2016(1), 446–451.

- Arthur CM, Stowell SR. The Development and Consequences of Red Blood Cell Alloimmunization. Annu Rev Pathol. 2023;18:537-564.

- Brinc D, Lazarus AH. Mechanisms of anti-D action in the prevention of hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;185-191.

- Jajosky RP, Patel KR, Allen JWL, et al. Antibody-mediated antigen loss switches augmented immunity to antibody-mediated immunosuppression. Blood. 2023;142(12):1082-1098.

- Flegel WA. Pathogenesis and mechanisms of antibody-mediated hemolysis. Transfusion. 2015;55 Suppl 2(0):S47-S58.

- Karafin MS, Westlake M, Hauser RG, et al. Risk factors for red blood cell alloimmunization in the Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study (REDS- III) database. Br J Haematol. 2018;181(5):672-681.

- British Committee for Standards in Haematology, Milkins C, Berryman J, et al. Guidelines for pre-transfusion compatibility procedures in blood transfusion laboratories. British Committee for Standards in Haematology [published correction appears in Transfus Med. 2022 Feb;32(1):91. doi: 10.1111/tme.12842]. Transfus Med. 2013;23(1):3-35.

- Simon TL, Cullough J, Snyder El et al. Rossi’s Principles of Transfusion Medicine 5th Ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley- Blackwell 2016.

- White, J. “Red cell antibodies-clinical significance or just noise?” Vox sanguinis vol 12, (2017):19-24.

- Thornton NM, Grimsley SP. Clinical significance of antibodies to antigens in the ABO, MNS, P1PK, Rh, Lutheran, Kell, Lewis, Duffy, Kidd, Diego, Yt, and Xg blood group systems. Immunohematology. 2019;35(3):95-101.

- Klein HG et al. Other red cell antigens. In: Klein HG, Anstee DJ, editors. Mollison’s Blood transfusion in clinical medicine. 11th ed. London: Blackwell Science; 2005.

- Das R, Dubey A, Agrawal P, Chaudhary RK. Spectrum of anti-M: a report of three unusual cases. Blood Transfus. 2014;12(1):99-102.

- Karafin MS, DeSimone RA, Dvorak J, et al. Antibody Titers in Transfusion Medicine: A Critical Reevaluation of Testing Accuracy, Reliability, and Clinical Use. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2023;147(12):1351-1359.

- Avent ND, Reid ME. The Rh blood group system: a review [published correction appears in Blood 2000 Apr 1;95(7):2197]. Blood. 2000;95(2):375-387.

- Daniels, G. Variants of RhD--current testing and clinical consequences. Br J Haematol. 2013;161(4):461-470.

- Scott, ML. The complexities of the Rh system. Vox Sang. 2004;87 Suppl1:58-62.

- Meny, GM. The Duffy blood group system: a review. Immunohematology. 2010;26(2):51-56.

- Stack, G. Post-transfusion detection of RBC alloimmunization: Timing is everything. Transfusion. 2021;61(8):2219-2222.

- Duval A, Frémeaux-Bacchi V. Complement biology for hematologists. Am J Hematol. 2023;98 Suppl 4:S5-S19.

- White J, Qureshi H, Massey E, et al. Guideline for blood grouping and red cell antibody testing in pregnancy. Transfus Med. 2016;26(4):246-263.

- Poston JN, Andrews J, Arya S, et al. Current advances in 2024: A critical review of selected topics by the Association for the Advancement of Blood and Biotherapies (AABB) Clinical Transfusion Medicine Committee. Transfusion. Published online August 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).