1. Introduction

Among the wide range of applications of essential oils, their potential as antimicrobial agents have long been studied [1]. The antimicrobial activity is closely linked to their chemical composition, which sometimes appears stronger than the activity of individual components due to the synergistic effect of the mixture [2]. Recently, the chemical composition and antioxidant activity of essential oils extracted from the leaves of various Citrus spp. have been reported [5,12]. In these articles, the authors highlighted a strong antimicrobial effect of the essential oil from the leaves of some Citrus limon species. This biological effect has been mainly attributed to the high concentration of citral (mixture of the two isomers neral and geranial) in the essential oil.

In this context, citrus leaves are known as valuable sources on citrus essential oil (EO) [3–5], easily obtained through steam distillation [6] The chemical profile of such EO is characterized by a mixture of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, alcohols, aldehydes, and esters [3,7,8]. The citrus leaf EO is usually rich in limonene [9], geranial, neral, citronellal, sabinene, linalool, (E)-_-ocimene, geraniol, geranyl acetate, linalyl acetate, alpha-terpineol, and myrcene [10–12]. This complex mixture of organic compounds shows wide biological activity against different pathogens. The employment of citrus EOs as antimicrobial [13,14], analgesic [15] insecticidal [16] anti-leishmanial [17], and antioxidant [5,9,10] have been reported. The biological activity of essential oils has been extensively studied in liquid phase[18], where it is possible to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration. Moreover, several authors have recently reported studies on the biological activity of essential oils in vapor phase on food matrices [19].

In this context, the designing of suitable systems for a controlled release of citrus leaf EO has gained attention.

The general addition of EOs to a solidliquid matrix or its deposition by filmcasting represent the most employed solutions for exploiting their antioxidant and antibacteric properties in food packaging [20]. Most employed materials able to include EOs are polymers as polypropylene, polyethylene, terephthalate, and some packages based on proteins, cellulose, and chitosan [20]. The application of eutectic mixture in this specific field is still unexplored. In fact, eutectic systems as the deep eutectic solvents (DESs) represent a suitable alternative for the dissolution and the controlled release of citrus leaf EO. DESs are eutectic systems, usually binary or ternary, composed by specific combination of hydrogen bond donors (HBDs) and acceptors (HBAs) which exhibit a melting point consistently lower than their theoretical one. Since the first report of Abbot and co-workers about the eutectic properties of selected mixtures between choline chloride and quaternary ammonium salts,[21] an exponential number of DESs and analogues has been designed and reported.[22] A general summary of the type of DESs is reported in

Table 1.

Regarding the many applications of DESs, their employment as releasing agents for active formulations is well known [23].

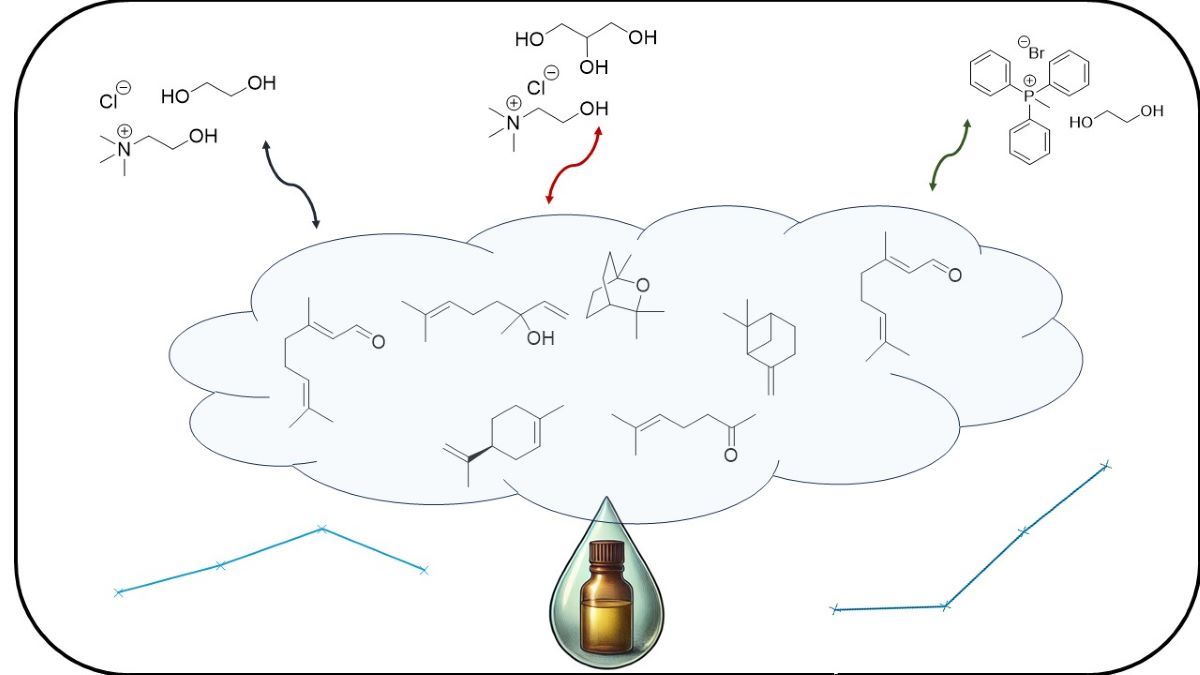

In the present research paper, three DESs have been tested as materials for the controlled release of Citrus limon essential oil obtained from lemon leaves: I - choline chloride:ethylene glycol (1:2) [24] II - triphenylmethylphosphonium bromide:ethylene glycol (1:5) [25] and III - choline chloride:glycerol (1:1.5) [26] GC chromatography coupled with MS spectrometry allowed to determine the releasing performances of the systems I-III, revealing a different behavior of system III, composed by choline chloride:glycerol, which resulted more efficient in trapping the volatiles mixture of the citrus leaf EO, providing its slower release. A sustainability and safety assessment has been conducted on the three potential solvents, revealing the suitability of the choline chloride:glycerol system even from a sustainable and safety perspective.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Choline chloride (98%), methyltriphenyl phosphonium bromide (98%), ethylene glycol (99%), and glycerol (99%) were purchased by Merk Europe.

2.2. Essential Oil Production

Essential oil was obtained from 0.5 kg leaves from Citrus limon trees ("Tirso Agrumi" farm, located near Solarussa, Italy) suspended in 0.7 Lof water and hydrodistilled for 2 hours with a Clevenger-type apparatus [27] The extraction was carried out in duplicate, the obtained essential oil (EO) were collected, dried over anhydrous Na₂SO₄ and stored at 4°C under a N2 in glass vials until analysis.

2.3. Eutectic Systems Preparation

Binary DESs were prepared in 1 g scale by mixing the two components in a vial equipped with a magnetic stirrer. The mixture was then heated at 80 °C and stirred during 1 h.

2.4.1. Static Headspace Extraction

200 mg of DESs containing 0.01 g (about 10% w/w) of EO in a 20 mL headspace vial tickly closed with a septum, were extracted using an Agilent 7694E automatic autosampler for headspace analysis. The extraction of volatiles was carried out after an equilibration at 60°C under shaking for 3 min. Loop and transfer line were maintained at 140°C. Helium was used as carrier gas and nitrogen as pressurization gas.

2.4.2. Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS) Analysis

Chemical analysis was carried out using an Agilent 6850 GC system coupled with an Agilent 5973 Mass Selective Detector. The chromatographic separation was performed on an HP-5 capillary column (30 m 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.17 _m). The following temperature program was used: 50 °C was held for 3 min, then increased to 210 °C at a rate of 4 °C/min, held for 15 min, and then increased at a rate of 10 °C/min up to 300 °C, which was finally maintained for 15 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min. Individual identification of the components was carried out by comparing the fragmentation spectra of the unknown molecules, separated into peaks by the GC component, with the spectra of known molecules available on the NIST online database. By comparing the Retention Indices of the unknown components of the EO that were experimentally detected with those of the NIST database, it was possible to further confirm the identification of the single molecules characterized by the fragmentation spectrum obtained by GC-MS. A solution of linear alkanes (C7–C22) was initially prepared and analyzed according to the same instrumental program applied for the EO samples in the same chromatographic column (HP-5) and Van den Dool and Kartz’s equation was applied in the calculation of the retention index (RI) [28].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Release Experiments

The following DESs have been tested as solvent and releasing agents for citrus leaf EO (

Table 2).

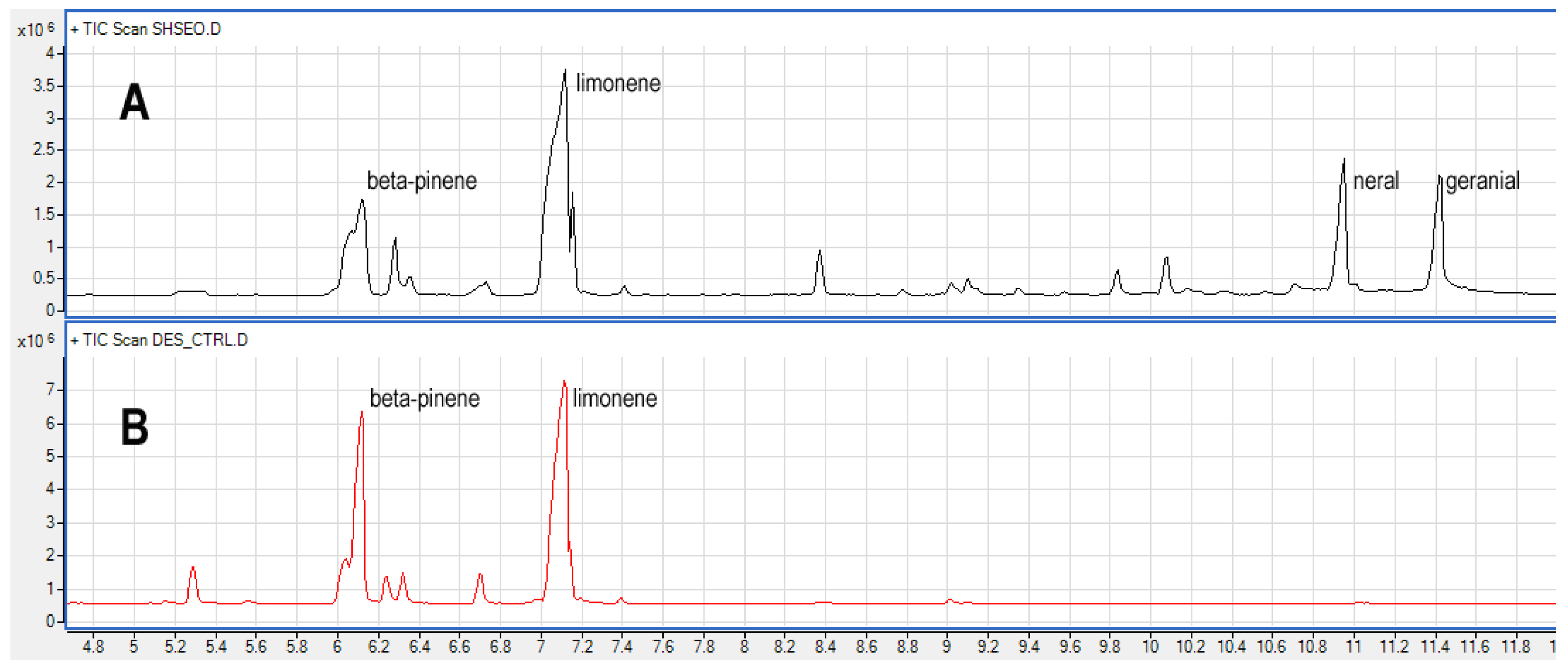

According to previous studies [10], the GC-MS analysis of the pure EO herein studied revealed the presence, as main constituents, of limonene, which dominates the chemical fingerprint accounting for 38% of the whole chromatogram, followed by neral and geranial which represent about the 10% each of the chromatogram (

Table 3). Beside to the liquid injection of the raw essetial oil, several experiments were carried out on the vapor fraction in the headspace. The direct comparison of the liquid injection vs headspace analysis of the same essential oil (

Table 3, pure oil vs CTRL) shows, as expected, that the headspace fraction is enriched in compounds with a higher vapor pressure whith respect to those with a lower one and, consequently, an higher boiling point. By looking

Figure 1, which represent the comparison of chromatograms of the same essential oil in headspace and liquid injection, is possible to observe an almost flat chromatogram in the headspace analysis after time 7.6 min supporting this conclusion.

*Results are expressed as mean of three replicate of the relative percent obtained by internal normalization of the chromatogram. RI: calculated retention index on an HP5 column. SD: standard deviation. CTRL stands for “control” meaning that the EO was analyzed in pure form. tr stands for traces. DESs I, II, and III are reported in

Table 1.

Looking at the chemical characteristics of the main volatile organic compounds (VOCs) detected in the tested EO, it is possible to notice the presence of ketones able to interact with DESs through hydrogen bonding, while interactions through dispersive forces involving the other chemical synthons can’t be excluded.

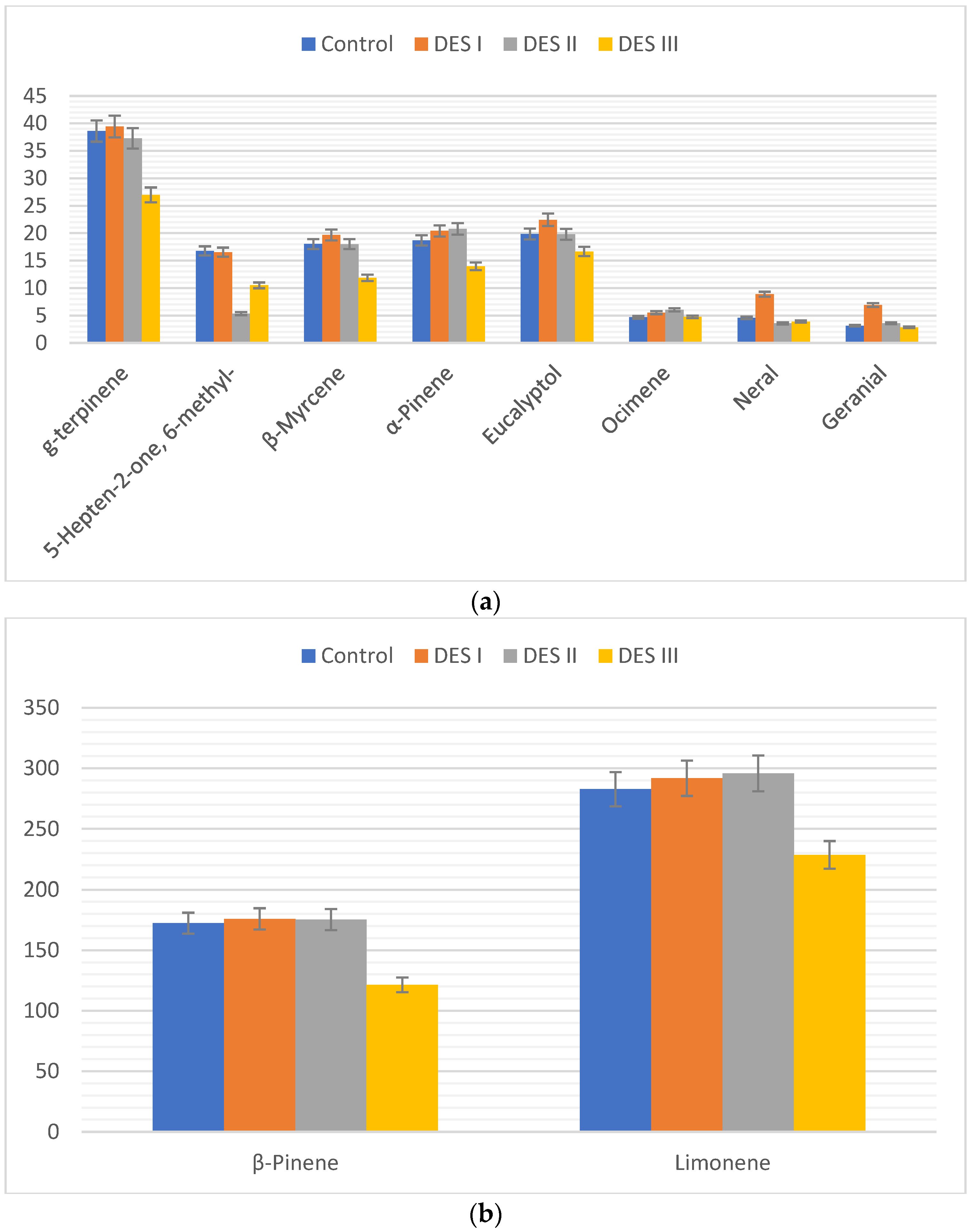

A direct comparision of the effect of the interactions between DES and essential oils was carried out on the absolute area of the chromatogram since the VOC profile was assessed from the same amount of EO dissoved in DESs I, II, and III. The results are reported in

Figure 2.

Looking at the data reported in

Figure 1, it is possible to see that specific organic molecules can be released in different way depending on the specific DES used. As general trend, the EO dissolved in DES III (choline chloride:glycerol) releases slower all the VOCs considered with respect to the control experiments (first bar on the left and last on the right for each VOC,

Figure 2). When DES I (choline chloride:ethylene glycol) is used, the volatility of the aldehydes neral and geranial resulted incremented with respect to the other solvents as well as to the control. This behaviour suggests that system I in some way is able to disdrupt the interactions occurring between the aldehydes and the other terpenes (mostly alkenes), making their releasing faster. This effect was not observed when instead of ethylene glycol, the glycerol is used as hydrogen bond donor (DES III). Also, a peculiar behaviour was detected for the 5-Hepten-2-one, 6-methyl- whose volatility is sensibly decreased when the EO is dissolved in DES II (methyltriphenylphosphonium bromide:glycerol). To the best of our knowledge, this ketone has not been previously detected in the leaves of

Citrus limon. Its presence in the essential oil could be due to the degradation of citral aldehydes, as previously described in the literature[29]. It should be considered that the DES I and III are considered hydrophilic [30], whith a molecular structure based mostly on hydrogen bonds, while the phosphonium DES II is hydrophobic [31], showing a consistent contribute of dispersive forces with respect to hydrogen bonds. The different nature and characteristics of the two types of DESs is then reflected on their behaviour with the ketone 5-Hepten-2-one, 6-methyl-.

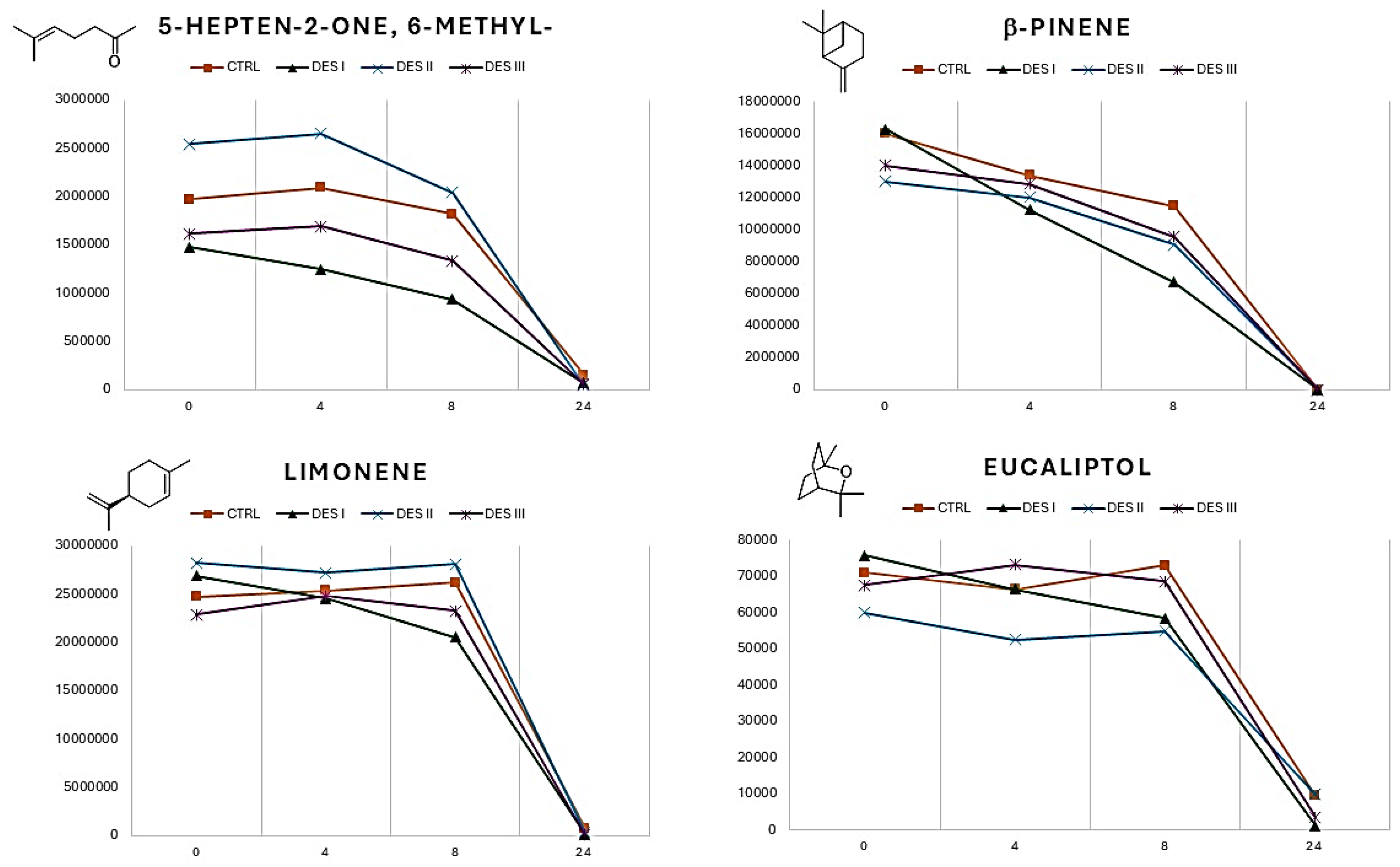

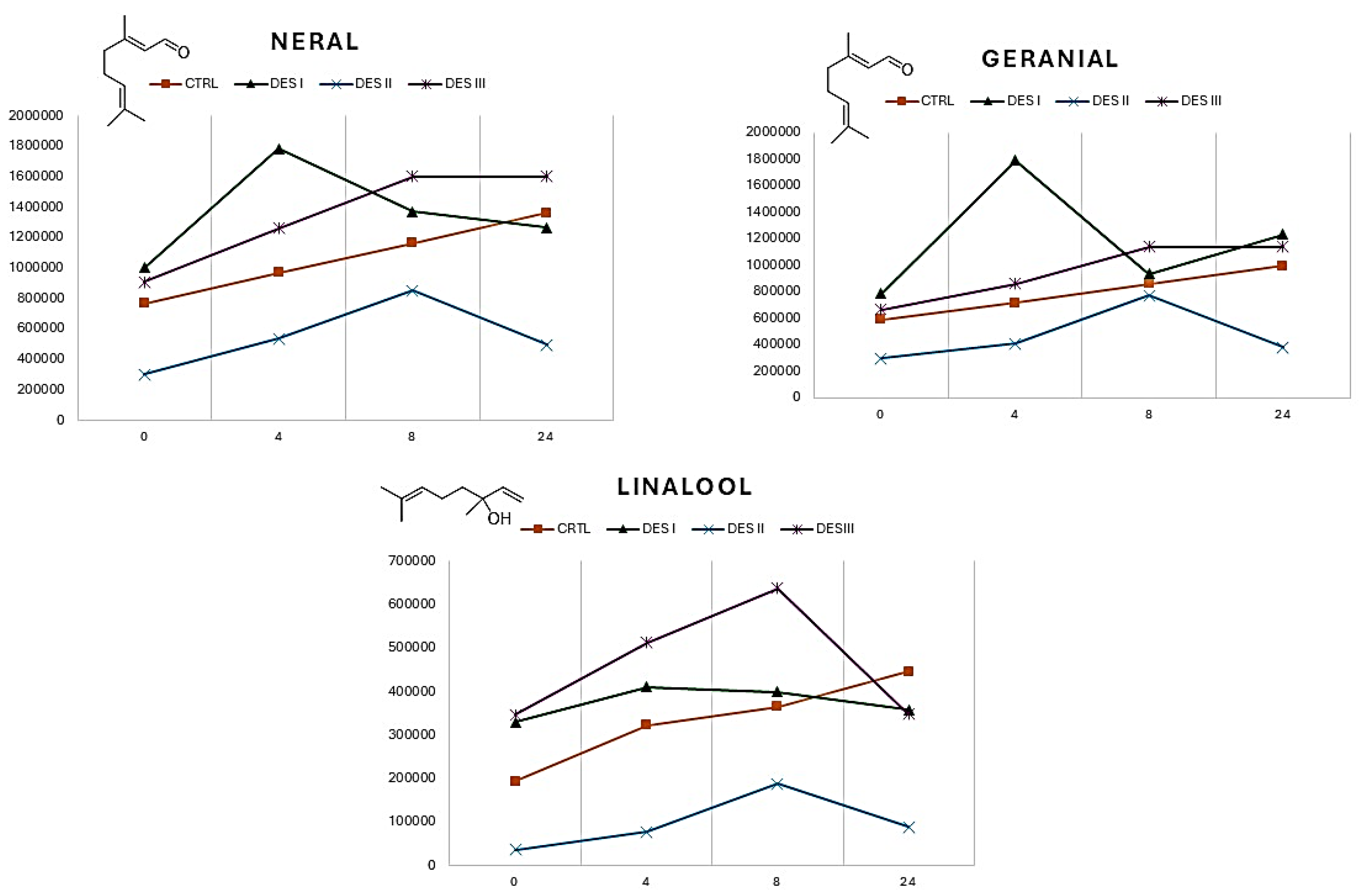

The EO is a complex mixture which physical characteristics, including the volatility, are the results of many interactions between the constituents, including the influence of synergic effects. Eutectic solvents of different nature (hydrophilic or hydrophobic) can interact differently with specific molecules. However, the major trend encountered is relative to the consistent decresing of the overall volatility of the EO when choline chloride:glycerol is used as solvent. To add further evaluation data, the variation of the volatile profile (neral, geranial, eucaliptol, limonene, 5-Hepten-2-one, 6-methyl-, linalool, β-pinene) during 24 h was recorded for the three DESs (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Looking at the plots reported in

Figure 3, it is possible to highlight some differences within the volatility of the single VOCs when the EO is dissolved in DES (I, II, and III) or is analysed as pure (CTRL curves). The monitoring of the 5-hepten-2-one, 6-methyl- and limonene showed no significant deviations from the control samples. In the case of β-pinene the releasing in DES I (choline chloride ethylene glycol) follows a different kinetic with respect to the control, resulting in a linear releasing during the time. Finally, the DES II (methyltriphenylphosphonium bromide ethylene glycol) impacts on the volatility of the eucaliptol, which is lower than in pure EO. All the VOCs reported in

Figure 3 show curves which ends in the same point after 24 h. Bigger differences can be observed if the volatility of neral, geranial and linalool is monitored (

Figure 4).

For all the three VOCs reported in

Figure 4 the pure EO shows a linear relasing over time, while the kinetics of the DESs are different. It is worth to highlight that neral and geranial are aldehydes, while the linalool is an unsaturated alcohol and thus all these VOCs have chemical groups senbsible to hydrogen bonding. A precise explanation of the kinetics of single VOCs would be not reliable due to the complex network of interactions which can occurr in the EO and in the different DESs. Nevertheless, some trends can be observed. When the EO is dissolved in the DES II (methyltriphenylphosphoiunm bromide ethylene glycol), the volatility of the aldehyde and of the linalool resulted reduced with respect to the control. Also, it is possible to observe some spikes corresponding to an increasing of the volatility for the neral and geranial in DES I, and for the linalool in DES II. Finally, after 24 h, the volatile content of the VOCs reported in

Figure 4 resulted different, suggesting a high sensibility of these polar molecules to the variation of the chemical composition of the EO.

To complete the assessment of the considered systems from the sustainability point of view, their were ranked according to the EcoScale procedure.

3.2. Sustainability and Safety Assessment

The analysis of the variation of the VOCs profile upon dissolution on systems I, II, and III, showed a different behavior depending on the specific type of molecule to be released (aldehydes, ketones, alkenes), whith the DES III showing a dinstinctive ability to decrease the overall volatility of the EO. To also explore the environmental and safety impact of the three systems considered, especially in the view of potential application of these systems in medicine or food devices, the EcoScale tool was used. According to Van Aken, sustainability and safety can be assessed by using the semiquantitative analysis EcoScale, which, starting from a score of 100, assign penalty points to several aspects related with the sustainability and safety of the process (equation 1) [32].

- (1)

EcoScale score = 100 – Σ individual penalty points

Panalty points are referred to yield, price of components, safety, technical setuptemperature, workup [Errore. Il segnalibro non è definito.]

The adaptation of the EcoScale to the three scenarios corresponding to the dissolution and releasing of the citrus leaf EO into the DESs I, II, and III, provided the following ranking (

Table 5).

The original EcoScale was designed for chemical reaction and thus, it has been adapted to our scenarios, as they are simple from an operational point of view. The preparation of the DESs is made with common laboratory setup (0 penalty points) at a temperature of 80 °C for more than 1 h (3 penalty points), and no workup is necessary (0 penalty points). The parameter yield can be related to the amount of citrus leaf EO which can be dissolved in the DES, and no differences have been observed within the three systems as they were able to fast dissolve 10 mg of EO in 200 mg of DES (0 penalty points). The cost of the components is considered high (5 penalty points), as the obtention of 10 mg of EO is associated to an elevate cost. Although same differences are present in the cost of the DESs’ components (with methyltriphenylphosphonium bromide more expensive that choline chloride and the diols), the higher cost related to the EO push all the three scenarios in the very expensive range.

What makes the real difference between scenarios I-III is the safety related to the components employed. Methyltriphenyl phosphonium bromide (CAS 1779-49-3) is classified as toxic if swallowed (H301) and toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects (H411), while ethylene glycol (CAS 107-21-1) is harmful if swallowed (H302) and may cause damage to organs (kidney) through prolonged or repeated exposure (if swallowed) (H373) [33]. On the other side, choline chloride and glycerol are considered safe, making the DES composed by choline chloride and glycerol the more suitable (97 EcoScale score versus 87 of the other scenarios), especially for application in medicine or food.

4. Conclusions

The possibility to employ three deep eutectic solvents as media for the controlled release of citrus leaf essential oil (EO) has been explored. The EO was dissolved in choline chloride:ethlylene glycol, methyltriphenylphosphonium bromide:ethylene glycol, or choline chloride:glycerol, and the volatile fraction was analyzed through headspace gas chromatography. Due to the nature of the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) present in the volatile fraction and to their different interaction with the three DESs considered, two general trends were observed. Choline-based DESs slower the releasing of alkene VOCs, while enhance the volatility of aldehyde-based neral and geranial. On the other side, phosphonium-based DES II sensibly reduces the volatility of the aldehyde VOCs, pourly interacting with the other less polar terpenes. Additionally, an assessment of the sustainability and safety was conducted for the three scenarios described above by using a system based on penalty points. As result, an EcoScale was obtained, which indicates the choline chloride:glycerol system as the most suitable for practical industrial application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.P. and A.M.; methodology, G.L.P. and A.M.; validation, G.L.P.; investigation, G.L.P. and A.M.; resources, G.L.P. and An.M; data curation, G.L.P. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.L.P., A.M., and An.M.; writing—review and editing, G.L.P., A.M., and An.M.; supervision, G.L.P., A.M., and An.M.; funding acquisition, G.L.P. and An.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Burt, S. Essential oils: their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods e a review. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2004, 94, 223e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyldgaard, M.; Mygind, T.; Meyer, R.L. Front. Microbiol., Sec. Antimicrobials, Resistance and Chemotherapy, 2012, 3.

- Brah, A.S.; Armah, F.A.; Obuah, C.; Akwetey, S.A.; Adokoh, C.K. Toxicity and therapeutic applications of citrus essential oils (CEOs): A review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouabdallah, S.; Cianfaglione, K.; Azzouz, M.; Batiha, G.E.; Alkhuriji, A.F.; Al-Megrin,W.A.I.; Ben-Attia, M.; Eldahshan, O.A. Sustainable extraction, chemical profile, cytotoxic and antileishmanial activities in-vitro of some citrus species leaves essential oils. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1163. [CrossRef]

- Fancello, F.; Petretto, G.L.; Zara, S.; Sanna, M.L.; Addis, R.; Maldini, M.; Foddai, M.; Rourke, J.P.; Chessa, M.; Pintore, G. Chemical characterization, antioxidant capacity and antimicrobial activity against food related microorganisms of Citrus limon var. pompia leaf essential oil. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 69, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzolo, E.; Laudicina, V.A.; Germanà, M.A. Current and potential use of citrus essential oils. Curr. Org. Chem. 2013, 17, 3042–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hsouna, A.; Ben Halima, N.; Smaoui, S.; Hamdi, N. Citrus lemon essential oil: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities with its preservative effect against Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in minced beef meat. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Nie, D.; Tang, W.; Li, Y. The chemical composition and antibacterial and antioxidant activities of five citrus essential oils. Molecules 2022, 27, 7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Tundis, R.; Bonesi, M.; Sanzo, G.D.; Verardi, A.; Lopresto, C.G.; Pugliese, A.; Menichini, F.; Balducchi, R.; Calabrò, V. Chemical profile and antioxidant properties of extracts and essential oils from Citrus _ limon (L.) Burm. cv. Femminello Comune. Chem. Biodivers. 2016, 13, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojjati, M.; Barzegar, H. Chemical composition and biological activities of lemon (Citrus limon) leaf essential oil. Nutr. Food Sci. Res. 2017, 4, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Tundis, R.; Bonesi, M.; Sanzo, G.D.; Verardi, A.; Lopresto, C.G.; Pugliese, A.; Menichini, F.; Balducchi, R.; Calabrò, V. Chemical profile and antioxidant properties of extracts and essential oils from Citrus _ limon (L.) Burm. cv. Femminello Comune. Chem. Biodivers. 2016, 13, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G.L. Petretto, G. Vacca, R. Addis, G. Pintore, M. Nieddu, F. Piras, V. Sogos, F. Fancello, S. Zara, A. Rosa, Waste Citrus limon Leaves as Source of Essential Oil Rich in Limonene and Citral: Chemical Characterization, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties, and Effects on Cancer Cell Viability. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1238. [CrossRef]

- Asker, M.; El-gengaihi, S.E.; Hassan, E.M.; Mohammed, M.A.; Abdelhamid, S.A. Phytochemical constituents and antibacterial activity of Citrus lemon leaves. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2020, 44, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Maugeri, A.; Lombardo, G.E.; Musumeci, L.; Barreca, D.; Rapisarda, A.; Cirmi, S.; Navarra, M. The second life of Citrus fruit waste: A valuable source of bioactive compounds. Molecules 2021, 26, 5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brah, A.S.; Armah, F.A.; Obuah, C.; Akwetey, S.A.; Adokoh, C.K. Toxicity and therapeutic applications of citrus essential oils (CEOs): A review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Tang, X.; Jian, R.; Li, J.; Lin, M.; Dai, H.; Wang, K.; Sheng, Z.; Chen, B.; Xu, X.; et al. Chemical composition, antimicrobial and insecticidal activities of essential oils of discarded perfume lemon and leaves (Citrus Limon (L.) Burm. F.) as possible sources of functional botanical agents. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 679116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouabdallah, S.; Cianfaglione, K.; Azzouz, M.; Batiha, G.E.; Alkhuriji, A.F.; Al-Megrin,W.A.I.; Ben-Attia, M.; Eldahshan, O.A. Sustainable extraction, chemical profile, cytotoxic and antileishmanial activities in-vitro of some citrus species leaves essential oils. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1163. [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, S.; Sharma, K.; Guleria, S. Antimicrobial Activity of Some Essential Oils—Present Status and Future Perspectives. Medicines 2017, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.K., Malik A., Gottardi D. Guerzoni, M.E. Essential oil vapour and negative air ions: A novel tool for food preservation. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2012, 26, 99–113. [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Chen, Z.; Xie, Y.; Yu, H.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, H.; Yao, W. Application of essential oil as a sustained release preparation in food packaging. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2019, 92, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.P. Abbott, G. Capper, D.L. Davies, R.K. Rasheed, V. Tambyrajah, Novel solvent properties of choline chloride/urea mixtures. Chem. Commun. 2003, 70–71.

- Mannu, A.; Blangetti, M.; Baldino, S.; Prandi, C. Promising Technological and Industrial Applications of Deep Eutectic Systems. Materials 2021, 14, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, S. N. , Freire, M. G., Freire, C. S. R., & Silvestre, A. J. D. Deep eutectic solvents comprising active pharmaceutical ingredients in the development of drug delivery systems. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery, 2019, 16(5), 497–506. [CrossRef]

- D. Lapena, L. Lomba, M. Artal, C. Lafuente, B. Giner, Thermophysical characterization of the deep eutectic solvent choline chloride:ethylene glycol and one of its mixtures with water. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2019, 492, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Skulcova, A., Russ, A., Jablonsky, M., and Sima, J. "The pH behavior of seventeen deep eutectic solvents,". BioRes. 2018, 13, 5042–5051. [CrossRef]

- Z.-T. Gao, Z.-M. Li, Y. Zhou, X.-J. Shu, Z.-H. Xu, D.-J. Tao, Choline chloride plus glycerol deep eutectic solvents as non-aqueous absorbents for the efficient absorption and recovery of HCl gas. New J. Chem., 2023, 47, 11498. [CrossRef]

- solvents as non-aqueous absorbents for the efficient absorption and recovery of HCl gas. New J. Chem., 2023, 47, 11498. [CrossRef]

- Fancello, F.; Petretto, G.L.; Zara, S.; Sanna, M.L.; Addis, R.; Maldini, M.; Foddai, M.; Rourke, J.P.; Chessa, M.; Pintore, G. Chemical characterization, antioxidant capacity and antimicrobial activity against food related microorganisms of Citrus limon var. pompia leaf essential oil. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 69, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Dool, H.; Kartz, P.D. Generalization of retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 1963, 11, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolken, W.A.M. , ten Have R. , van der Werf M.J. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 5401−5405. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, Z. Insights into the Hydrogen Bond Interactions in Deep Eutectic Solvents Composed of Choline Chloride and Polyols. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineerin, 2019, 7(8), 7760–7767. [CrossRef]

- Haghbakhsh, R.; Bardool, R.; Bakhtyari, A.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Raeissi, S. Simple and global correlation for the densities of deep eutectic solvents. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2019, 296, 111830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aken, K.; Strekowski, L.; Patiny, L. EcoScale, a semi-quantitative tool to select an organic preparation based on economical and ecological parameters. Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry 2006, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online (REACH database) at https://echa.europa.eu/information-on-chemicals/registered-substances. Accessed on September 25, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).