Submitted:

14 October 2024

Posted:

14 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antagonistic Bacterial Strain and Culture Conditions

2.2. Field Sampling and Environmental Condition

2.3. Microbial DNA Extraction and Sequencing

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Conditions in The Tested Orchard

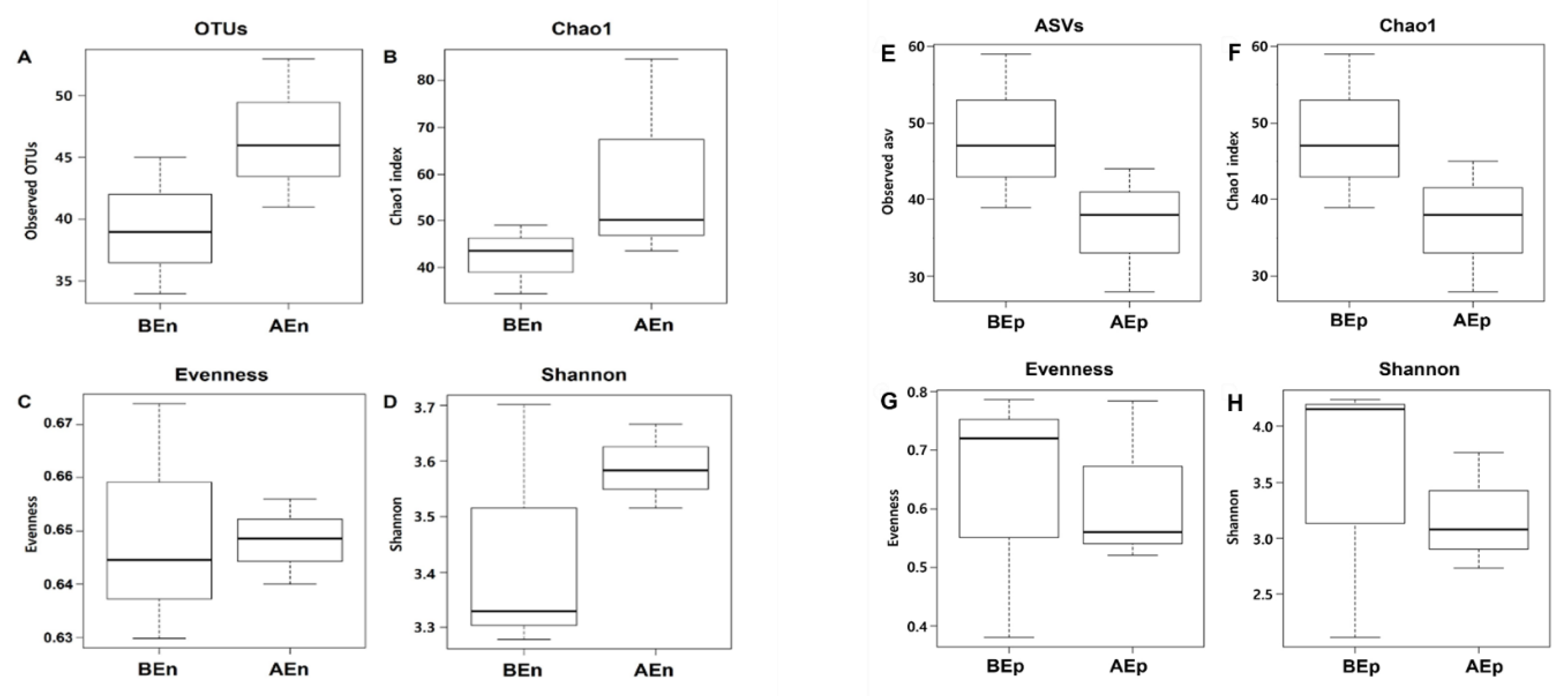

3.2. Bacterial Diversity in Endosphere and Episphere from Apple Leaves Before and After KPB25 Treatment

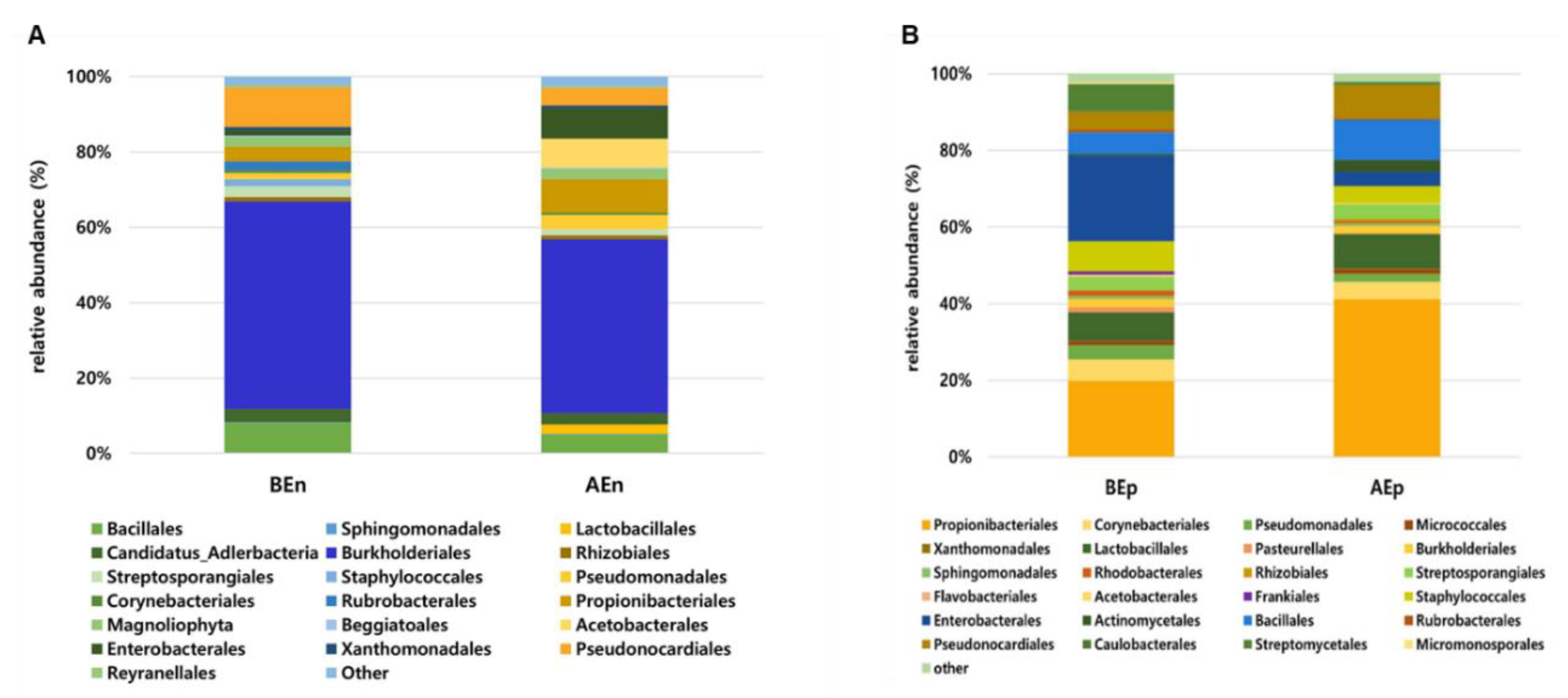

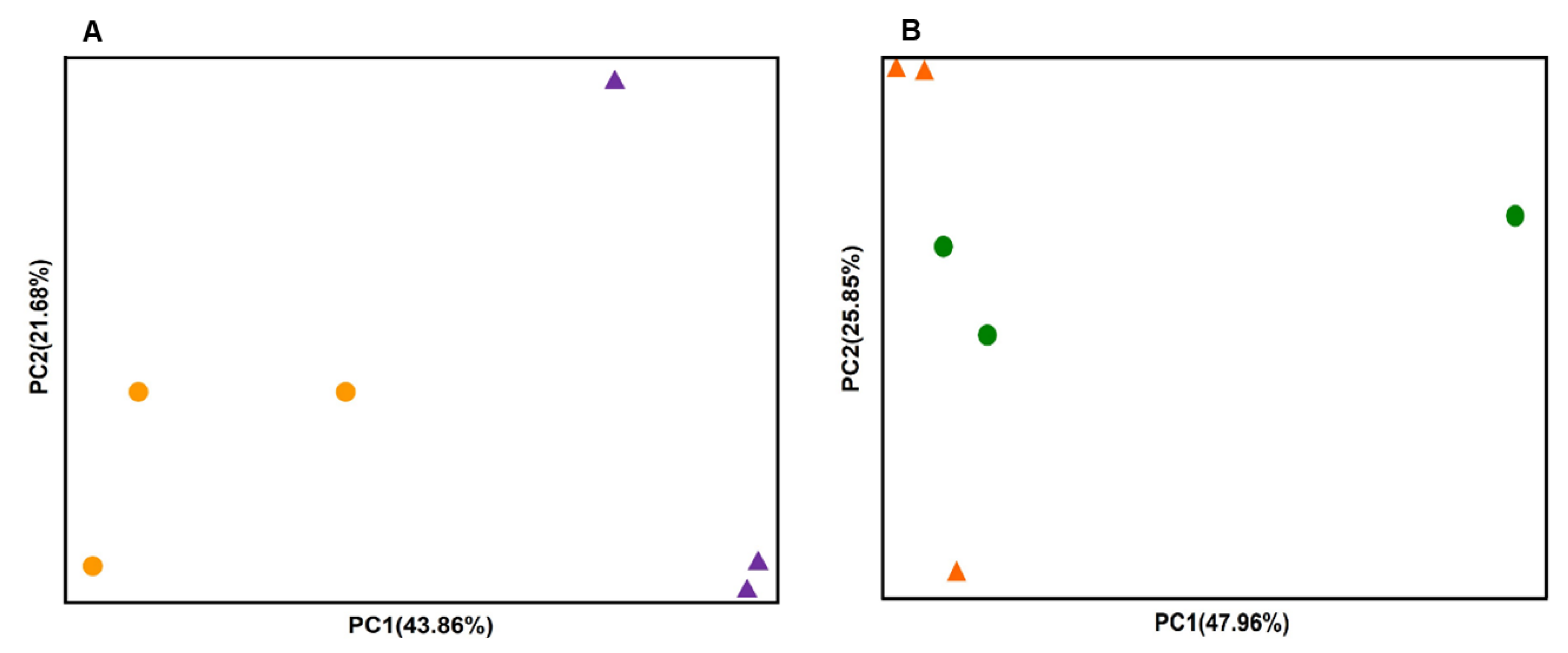

3.3. Bacterial Structure in the Endosphere and Episphere Before and After KPB25 Treatment

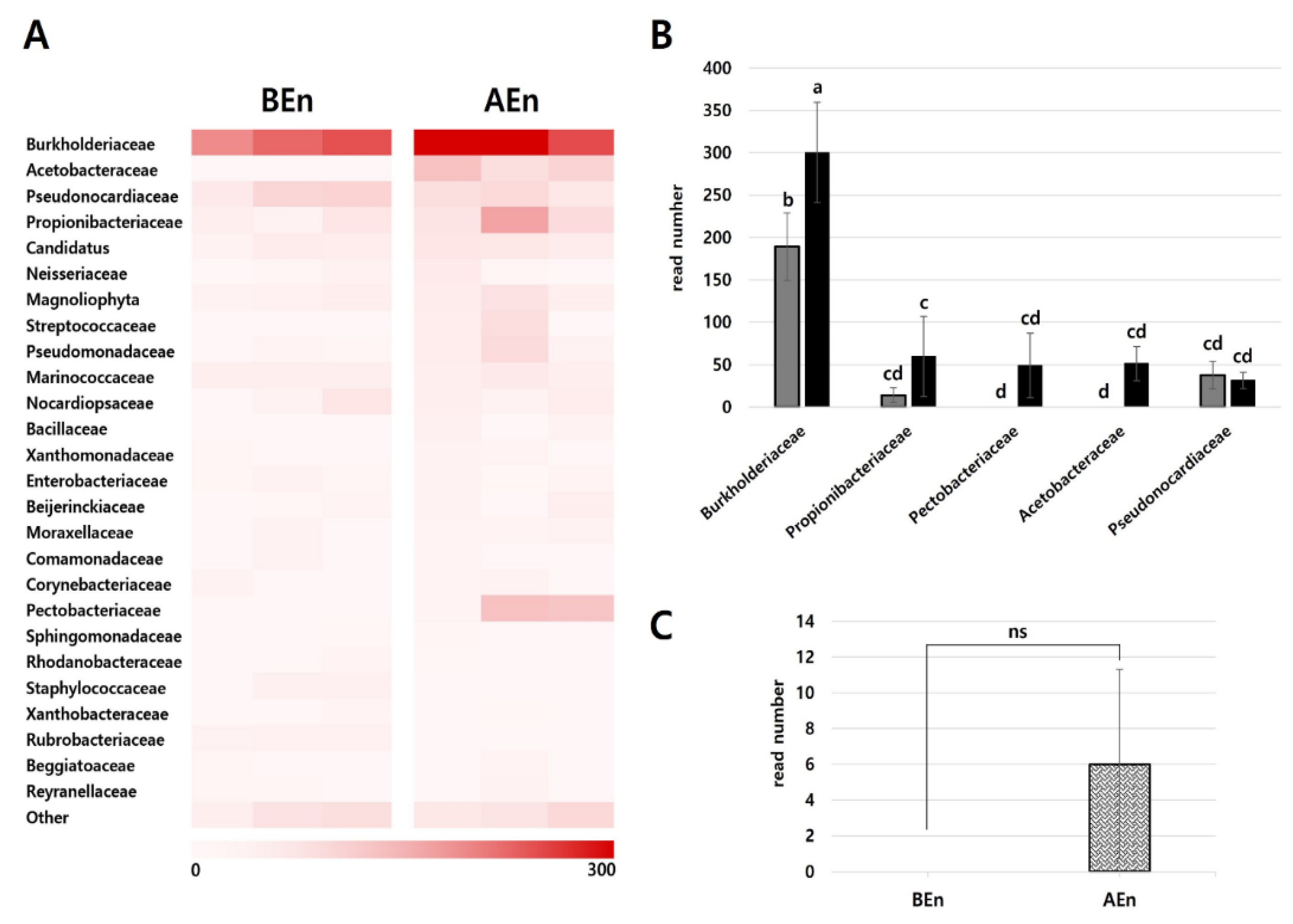

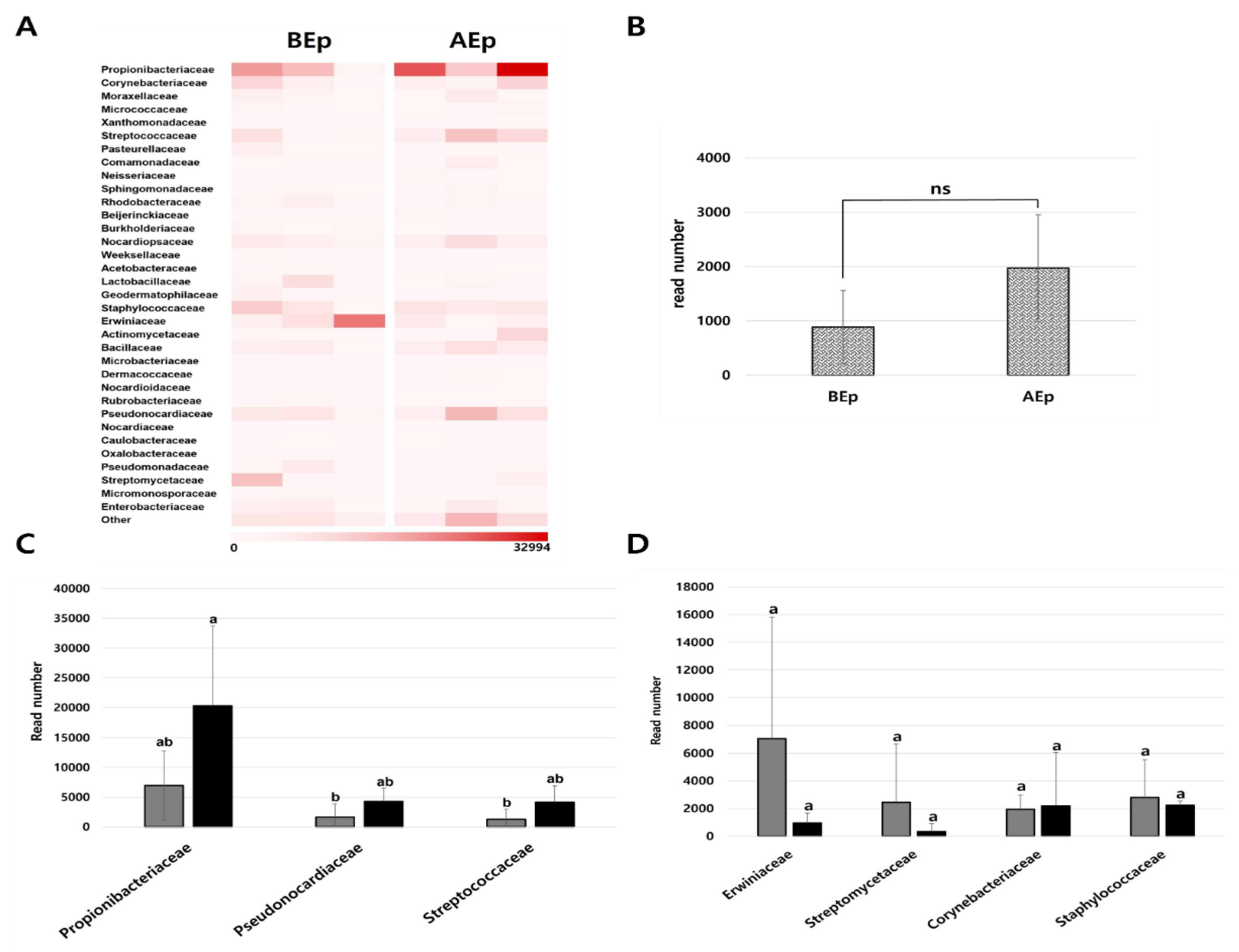

3.4. Composition of the Dominant Bacterial Community in the Endosphere and Ephisphere Before and After KPB25 Treatment

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

References

- Myung, I.-S.; Lee, J.-Y.; Yun, M.-J.; Lee, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.-K.; Park, D.H.; Oh, C.-S. Fire blight of apple, caused by Erwinia amylovora, a new disease in Korea. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Yu, J.-G.; Oh, E.-J.; Han, K.-S.; Yea, M.C.; Lee, S.J.; Myung, I.-S.; Shim, H.S.; Oh, C.-S. First report of fire blight disease on Asian pear caused by Erwinia amylovora in Korea. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, H.; Lee, Y.-K.; Kong, H.G.; Hong, S.J.; Lee, K.J.; Oh, G.-R.; Lee, M.-H.; Lee, Y.H. Outbreak of fire blight of apple and Asian pear in 2015-2019 in Korea. Res. Plant Dis. 2020, 26, 222–228. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, H.; Roh, E.; Lee, M.-H.; Lee, Y.-K.; Park, D.S.; Kim, K.; Lee, B.W.; Ahn, M.I.; Lee, W.; Choi, H.-W.; Lee, Y.H. Emergence characteristics of fire blight from 2019 to 2023 in Korea. Res. Plant Dis. 2024, 30, 139–147. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Lee, Y.G.; Kim, J.S.; Cha, J.S.; Oh, C.-S. Current status of fire blight caused by Erwinia amylovora and action for its management in Korea. J. Plant Pathol. 2017, 99, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.H.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lim, Y.-J.; Lee, I.; Park, D.H. Screening of bacterial antagonists to develop an effective cocktail against Erwinia amylovora. Res. Plant Dis. 2022, 28, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alengebawy, A.; Abdelkhalek, S.T.; Qureshi, S.R.; Wang, M.-Q. Heavy metals and pesticides toxicity in agricultural soil and plants: Ecological risks and human health implications. Toxics, 2021, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnahal, A.S.M.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Desoky, E.-S.M.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Rady, M.M.; AbuQamar, S.F.; El-Tarabily, K.A. The use of microbial inoculants for biological control, plant growth promotion, and sustainable agriculture: A review. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 162, 759–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldwinckle, H.S.; Bhaskara Reddy, M.V.; Norelli, J.L. Evaluation of control of fire blight infection of apple blossoms and shoots with SAR inducers, biological agents, a growth regulator, copper compounds, and other materials. Acta Hortic. 2002, 590, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broggini, G.A.L.; Duffy, B.; Holliger, E.; Schärer, H.-J.; Gessler, C.; Patocchi, A. Detection of the fire blight biocontrol agent Bacillus subtilis BD170 (Biopro®) in a Swiss apple orchard. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2005, 111, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadou, S.A.; Ouijja, A.; Karfach, A.; Tahiri, A.; Lahlali, R. New potential bacterial antagonists for the biocontrol of fire blight disease (Erwinia amylovora) in Morocco. Microb. Pathogenesis, 2018, 117, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shemshura, O.; Alimzhanova, M.; Ismailova, E.; Molzhigitova, A.; Daugaliyeva, S.; Sadanov, A. Antagonistic activity and mechanism of a novel Bacillus amyloliquefaciens MB40 strain against fire blight. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 102, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H.; Scholz, R.; Borriss, M.; Junge, H.; Mögel, G.; Kunz, S.; Borriss, R. Difficidin and bacilysin produced by plant-associated Bacillus amyloliquefaciens are efficient in controlling fire blight disease. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 140, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sébastien, M.; Margarita, M.-M.; Haissam, J.M. Biological control in the microbiome era: Challenges and opportunities. Biol. Control, 2015, 89, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, G.; Grube, M.; Schloter, M.; Smalla, K. Unraveling the plant microbiome: Looking back and future perspectives. Front Microbiol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, M. Plant phenotypic plasticity in the phytobiome: A volatile issue. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2016, 32, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, C.V.; Connor, E.W. Translating phytobiomes from theory to practice: Ecological and evolutionary considerations. Phytobiomes J. 2017, 1, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, A.; Whitehead, S.R.; Macarisin, D.; Liu, J.; Burchard, E.; Freilich, S.; Dardick, C.; Droby, S.; Wisniewski, M. Effect of washing, waxing and low-temperature storage on the postharvest microbiome of apple. Microorganisms, 2020, 8, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bösch, Y.; Britt, E.; Perren, S.; Naef, A.; Frey, J.E.; Bühlmann, A. Dynamics of the apple fruit microbiome after harvest and implications for fruit quality. Microorganisms, 2021, 9, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Huntley, R.B.; Zeng, Q.; Steven, B. Temporal and spatial dynamics in the apple flower microbiome in the presence of the phytopathogen Erwinia amylovora. ISME J. 2021, 15, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, D.-R.; Cho, G.; Kwak, Y.-S. Dynamics of bacterial communities by apple tissue: Implications for apple health. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, H.G.; Ham, H.; Lee, M.-H.; Park, D.S.; Lee, Y.H. Microbial community dysbiosis and functional gene content changes in apple flowers due to fire blight. Plant Pathol. J. 2021, 37, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhlaghi, M.; Tarighi, S.; Taheri, P. Effects of plant essential oils on growth and virulence factors of Erwinia amylovora. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 102, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Calle, D.; Benevides, R.G.; Góes-Neto, A.; Billington, C. Bacteriophages as alternatives to antibiotics in clinical care. Antibiotics, 2019, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Salem, H.M.; Ashry, N.M.; Abo Ghanima, M.M.; Shukry, M.; swelum, A.A.; Taha, A.E.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Abu Qamar, S.F.; El-Tarabily, K.A. Essential oils and their nanoemulsions as green alternatives to antibiotics in poultry nutrition: A comprehensive review. Poultry Sci. 2022, 101, 101584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Jeon, Y.H.; Ahn, J.-H.; Ahn, S.H.; Yoon, Y.G.; Park, I.C.; Park, J.W. Induction of systemic resistance against Phytophthora blight by Enterobacter asburiae ObRS-5 with enhancing defense-related gene expression. Korean J. Environ. Biol. 2020, 38, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, L.; Zeriouh, H.; Romero, D.; Cubero, J.; de Vicente, A.; Pérez-García, A. The antagonistic strain Bacillus subtilis UMAF6639 also confers protection to melon plants against cucurbit powdery mildew by activation of jasmonate- and salicylic acid-dependent defence responses. Microb. Biotechnol. 2013, 6, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, W.L. Roles of Bacillus endospores in the environment. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Cho, G.; Lee, S. I.; Kim, D.-R.; Kwak, Y.-S. Comparison of bacterial community of healthy and Erwinia amylovora infected apples. Plant Pathol. J. 2021, 37, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenye, T. The Family Burkholderiaceae. In: The Prokaryotes, Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria, 4th ed. eds. by E. Rosenberg; E.F. DeLong; S. Lory; E. Stackebrandt; F. Thompson, 2014. pp. 759–776. Springe-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Komagata, K.; Iino, T.; Yamada, Y. The Family Acetobacteraceae. In: The Prokaryotes, Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria, 4th ed. eds. by E. Rosenberg; E.F. DeLong; S. Lory; E. Stackebrandt; F. Thompson, 2014. pp. 3–78. Springe-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Reis, V.M.R.; Teixeira, K.R. dos S. Nitrogen fixing bacteria in the family Acetobacteraceae and their role in agriculture. J. Basic Microbiol. 2015, 55, 931–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.; Lee, S.-H.; Hur, J.-H.; Lim, C.-K. The effects of temperature, pH, and bactericides on the growth of Erwinia pyrifoliae and Erwinia amylovora. Plant Pathol. J. 2005, 21, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Franco, M.; labeda, D.P. The Order Pseudonocardiales. In: The Prokaryotes, Actinobacteria, 4th ed. eds. by E. Rosenberg; E.F. DeLong; S. Lory; E. Stackebrandt; F. Thompson, 2014. pp. 743–860. Springe-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Platas, G.; Morón, R.; González, I.; Collado, J.; Genilloud, O.; Peláez, F.; Diez, M.T. Production of antibacterial activities by members of the family Pseudonocardiaceae: Influence of nutrients. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1998, 14, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, J.P.S.; Dove, N.C.; Hart, S.C. Leaf endophytic microbiomes of different almond cultivars grafted to the same rootstock. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 3768–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patz, S.; Witzel, K.; Scherwinski, A.-C.; Ruppel, S. Culture dependent and independent analysis of potential probiotic bacterial genera and species present in the phyllosphere of raw eaten produce. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- app-Rupar, M.; Karlstrom, A.; Passey, T.; Deakin, G.; Xiangming, X. The influence of host genotypes on the endophytes in the leaf scar tissues of apple trees and correlation of the endophytes with apple canker (Neonectria ditissima) development. Phytobiomes J. 2022, 6, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini-Andreote, F. Endophytes: The second layer of plant defense. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).