1. Introduction

Tyrosinase is an enzyme belonging to the polyphenol oxidase group and acts as the central enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway of melanin[

1,

2,

3,

4]. Tyrosinase catalyzes the conversion of tyrosine into L-DOPA and subsequent L-DOPA into

O-quinone, resulting in the synthesis of melanin through subsequent spontaneous reactions[

5,

6]. Which can lead to hyperpigmentation disorders such as senile lentigo, chloasma, and freckles; when melanin is in excess within the body, it significantly affects the phenotypic appearance[

7]. Apart from these, neurodegenerative problems like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s can cause tyrosinase overexpression and hyperactivation[

8,

9]. Beyond its pathogenic roles, tyrosinase is crucial for enzymatic browning, leading to a significant concern during plant-based foods’ handling, processing, and long-term storage[

10,

11]. Thus, inhibiting tyrosinase’s catalytic activity represents a practical approach to skin brightness and lightening.

The readily available ascorbic acid[

12,

13], kojic acid[

14], arbutin[

15,

16], and hydroquinone[

17,

18,

19] are among the myriad of tyrosinase inhibitors. Nonetheless, the drawbacks of these inhibitors make them blemished due to the potential carcinogenicity, high cellular toxicity, instability and off-odours propensities[

20,

21]. With the growing consumer awareness towards the possible side effects of these inhibitors, there is a high demand for naturally occurring tyrosinase inhibitors as a safer alternative.

Bioactive peptides derived from food have emerged as promising alternatives due to their potential effectiveness, availability, targeting capabilities, safety and specificity[

22,

23]. However, despite the potential theoretical and practical application of thesis peptides, they always encounter challenges, along with their stability and selectivity, which remain a critical concern for peptide tyrosinase inhibitors. Hydrolysis susceptibility is observed in both

in vivo and

in vitro environments for many peptide-based, resulting in rapid deactivation, thereby diminishing their ability to deliver sustained effects in practical scenarios, impacting the therapeutic efficacy and patient experience. Furthermore, the bioavailability of these inhibitors presents another challenge. Traversing cell membrane is impeded due to the large molecular weight of peptide compounds, leading to restricted drug concentration in the body to reach minimum therapeutic levels. Addressing this issue involves enhancing drug design; for instance, the drug bioavailability could be improved by incorporating suitable carriers or modifying groups. These challenges significantly limit the practical application of peptide tyrosinase inhibitors in clinical settings.

2. Materials and Methods:

2.1. Materials:

Methyl Thiazolyl Tetrazolium (MTT) was procured from Sigma-Aldrich. DMEM/F12 Medium, Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin were obtained from Gibco. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was sourced from Solarbio, China. Analytical Grade Melanin, tranexamic acid and L-DOPA were purchased from Sigma. Glabridin and kojic acid were acquired from Olibio Co. Ltd. and Yuanye Biotechnology Co. Ltd., respectively. All other reagents were obtained from commercial sources and used as received without further purification.

2.2. Cell culture

The human melanocyte (Batch number: MC210817) were purchased from Guangdong Biocell Biotechnology Co. LTD. Cells were cultured in complete medium (DMEM/F12) supplemented with 20% FBS (Hyclone) and 100 U/ml penicillin. All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 (V/V).

2.3. Cytotoxicity evaluations

The cytotoxicity effect of peptides on human melanocyte cells was assessed using the standard Methyl Thiazolyl Tetrazolium (MTT) assay[

24]. Cells were initially seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 10000 cells per well. Following a 12 h incubation at 37 ºC in a humidified incubator (5% CO

2, V/V), the cells were treated with target peptides or the positive control for 24 h. Eight gradient concentrations were established for each compound, with three replications per concentration. The cells in the negative control group were treated with only a culture medium containing DMSO (10%, V/V). Following incubation, cells were treated with 0.5 mg/mL MTT for 4 h at 37 °C; subsequently, the formazan crystals formed in viable cells were dissolved in 150 μL DMSO. The absorbance of solubilized formazan was measured using a Synergy multimode reader (BioTek, American) at the wavelength of 490 nm.

2.4. Determination of Melanin Content in melanocyte

Upon reaching 80–90% confluence, human melanocyte cells were dissolved with 0.25% trypsin to create a single-cell suspension. Then, the cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 200000 cells per well and cultured for 12 h in a 37 ºC humidified incubator (5% CO2, V/V). When the confluence of cells reached 40% to 60%, they were incubated with specific peptides or the positive control for 24 h. following the incubation period, the supernatant was removed and the adherent cells were washed with PBS before being dispersed using trypsin (700 μL/well, 0.25%). The dispersed cells were collected and centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 10 min. The cell pellet from each well was then treated with a mixture of distilled water (200 μL), anhydrous ethanol (500 μL) and ether (500 μL). The mixture was vortexed and allowed to stand at room temperature for 20 min, followed by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The precipitation was added 1 ml of 1M NaOH with a 10% concentration of DMSO and incubated at 80 ◦C in a water bath for 40 min before being transferred to a 96-well culture plate. For optical density measurement, 405 nm wavelength was used for each well. Each analysis was replicated three times and the results were presented as a mean ± SD (standard deviation). SPSS Statistics 20 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was selected for student t-test analysis of variance.

2.5. Tyrosinase inhibition assay

The inhibition of tyrosinase activity was assessed according to the reported method[

25]. The 6-well plates were incubated at 37 ºC with human melanocyte cells at a density of 2.5×10

5 cells per well in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO

2) for 24 h. Subsequently, these cells were exposed to glabridin (0.00625%, V/V) as the positive control, along with other tested compounds. Following treatment, cells were incubated at 37 ºC for 24 h using identical conditions. After treatment, cells in each well were rinsed with a PBS buffer solution (500 μL) and lysed with a lysate buffer (100 µl containing 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) at approximately 0 ºC for 1 h. The resulting cell lysate was then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 ºC for 20 min. The protein concentration in the supernatant was quantified by a BCA Assay Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). Samples were transferred to a 96-well plate in a total volume of 100 µl (90 µL of lysate supernatant and 20 µL of 0.1% L-DOPA) and incubated for 60 min at 37 ºC. The absorbance was measured at 475 nm using a Synergy multimode reader (BioTek Corporation, USA).

2.6. Molecular docking

The cyclopeptide CHP-9, a potent inhibitor in tyrosinase inhibition assay, was docked into the active site cavity of human tyrosinase (PDB ID: 5M8M) using the MOE 2008 docking program after removing all water molecules from the crystal structure before the experiment to ensure precise docking results. The Protonate 3D application was added with hydrogens and partial charges. We then defined the docking site for residues within an 8 Å radius of kojic acid. The initial 3D conformation of CHP-9 was optimized in ChemBio3D Ultra using the MM2 energy minimization method. We applied the default parameter values for docking, modifying only the scoring function to ASE Scoring from the typical London dG. This scoring adjustment identified the best pose.

To assess the feasibility of the docking program for the ligand binding to human-tyrosinase, we initially selected tyrosinase-related protein 1 in complex with kojic acid (PDB ID: 5M8M) and the docking structure of kojic acid was comparable to its crystallographic structure. This result implied that the MOE docking program is appropriate for identifying a binding model between CHP-9 and human tyrosinase.

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. Experimental

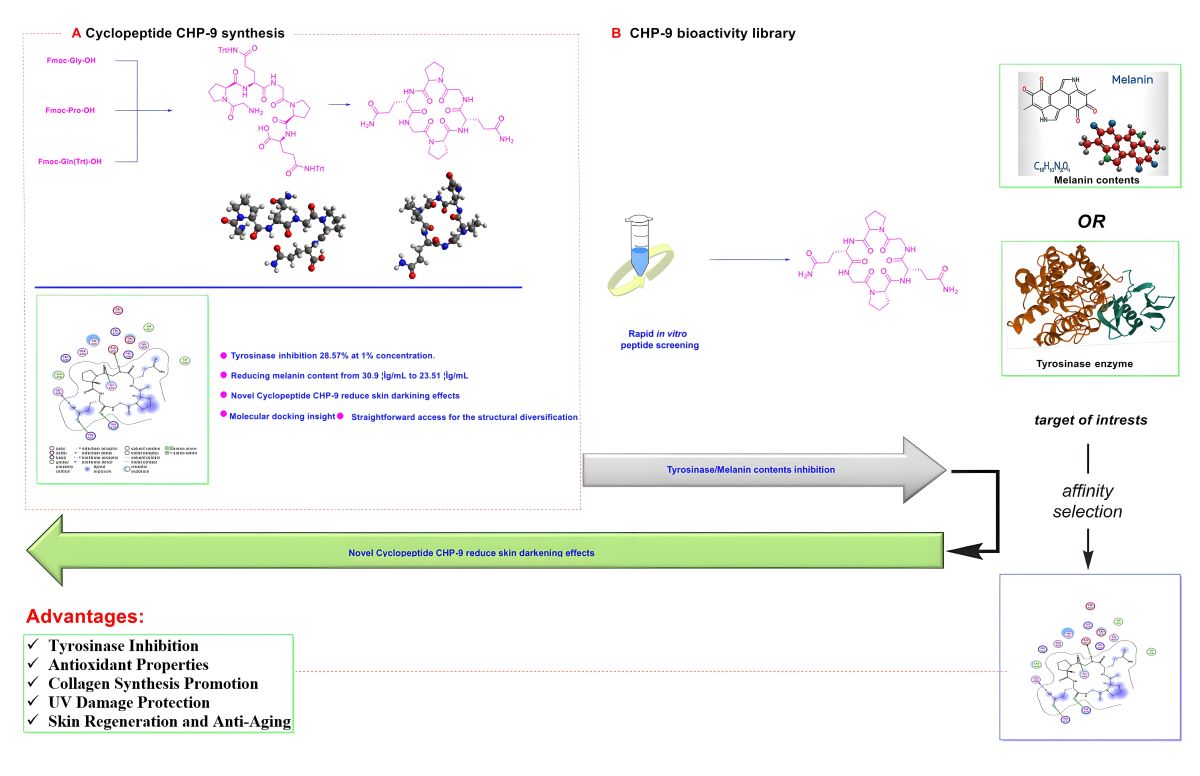

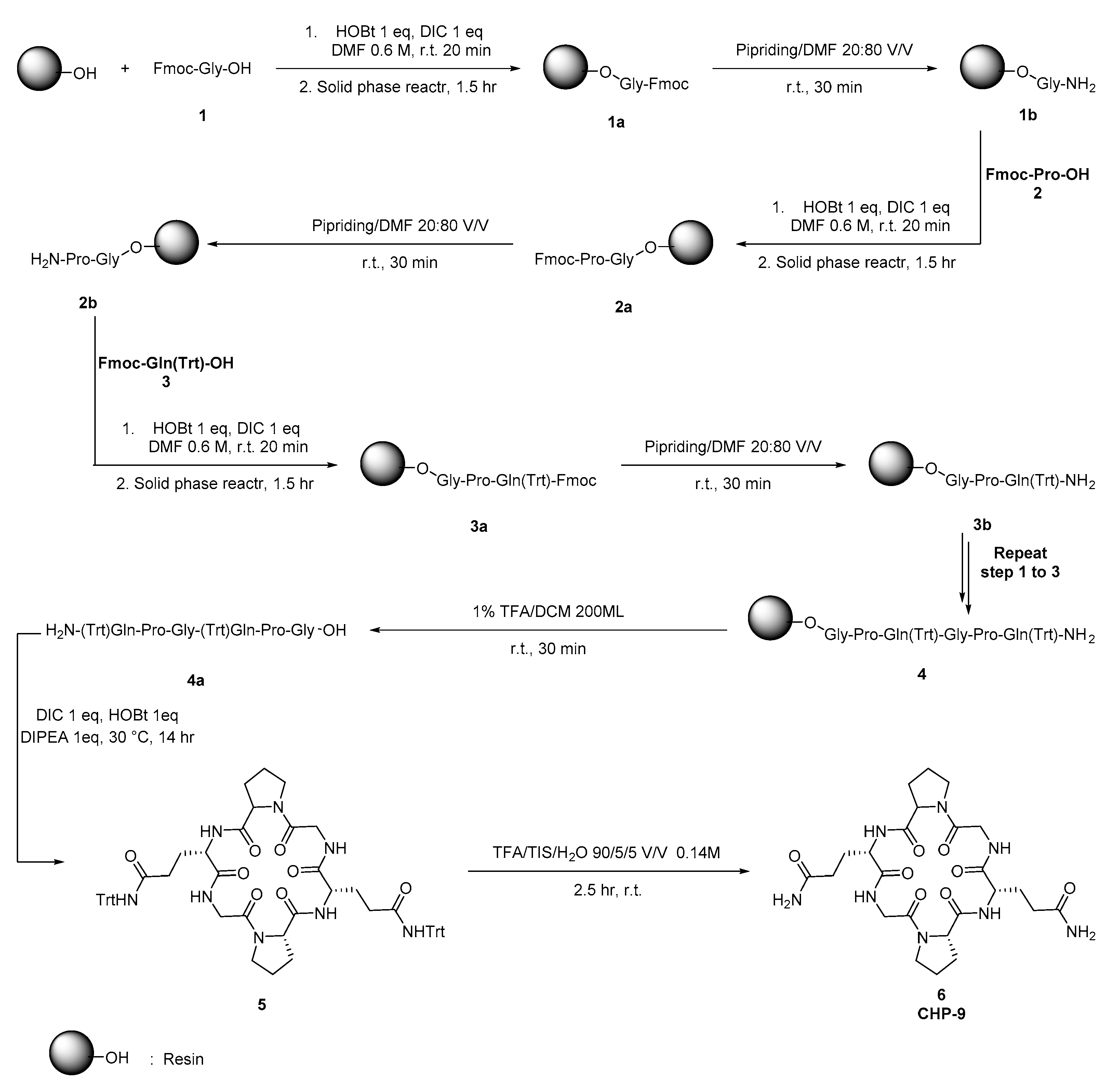

The cyclopeptide

CHP-9 was synthesized according to the reported strategy[

26]. The CHP-9 was synthesized from the amino acids Fmoc-Gly-OH (

1), Fmoc-Pro-OH (

2), and Fmoc-Gln(Trt)-OH (

3) as starting materials to prepare the linear peptide (

4) using classical synthetic strategies and solid phase resin reactor flask as illustrated in scheme 1. The linear peptide, H-Gln(Trt)-Gly-Pro-Gln(Trt)-Gly-Pro-OH (

4a), was then cyclized to form the intermediate Cyclo(Gln(Trt)-Gly-Pro-Gln(Trt)-Gly-Pro) (

5). The intermediate (

5) underwent a deprotection strategy, yielding the crude peptide. The crude product was purified by reverse-phase C18 preparative chromatography and lyophilized to obtain the pure compound (cyclopeptide

CHP-9) Cyclo(Gln-Gly-Pro-Gln-Gly-Pro) (

6), with a final purity of 99.2%, confirmed by HPLC analysis. HRMS (ESI-TOF):

m/z [M + Na]

+ calcd for C24H36O8N8Na, 587.2554; found, 587.2549.

Scheme 1.

synthetic strategy of Cyclopeptide (CHP-9).

Scheme 1.

synthetic strategy of Cyclopeptide (CHP-9).

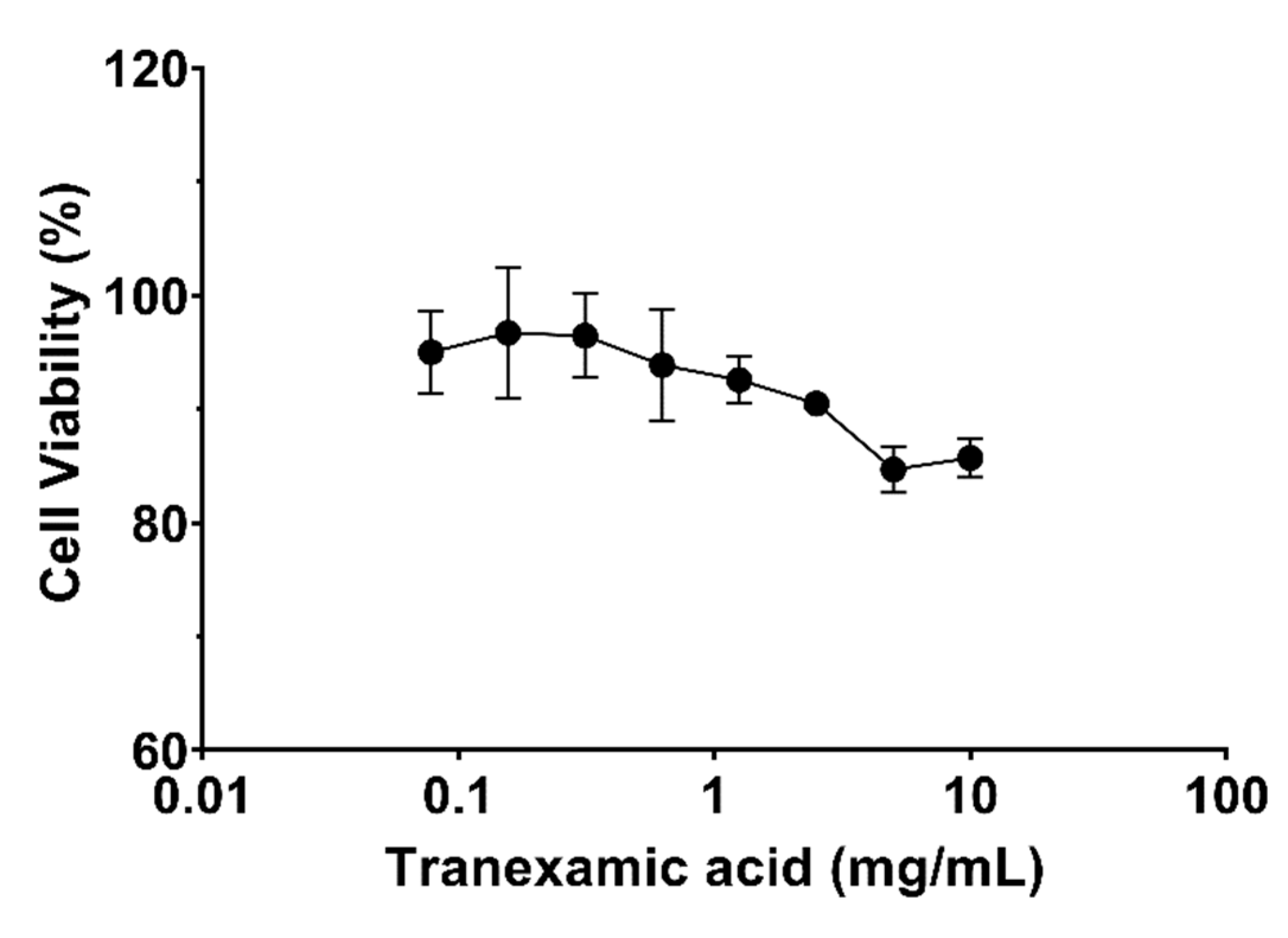

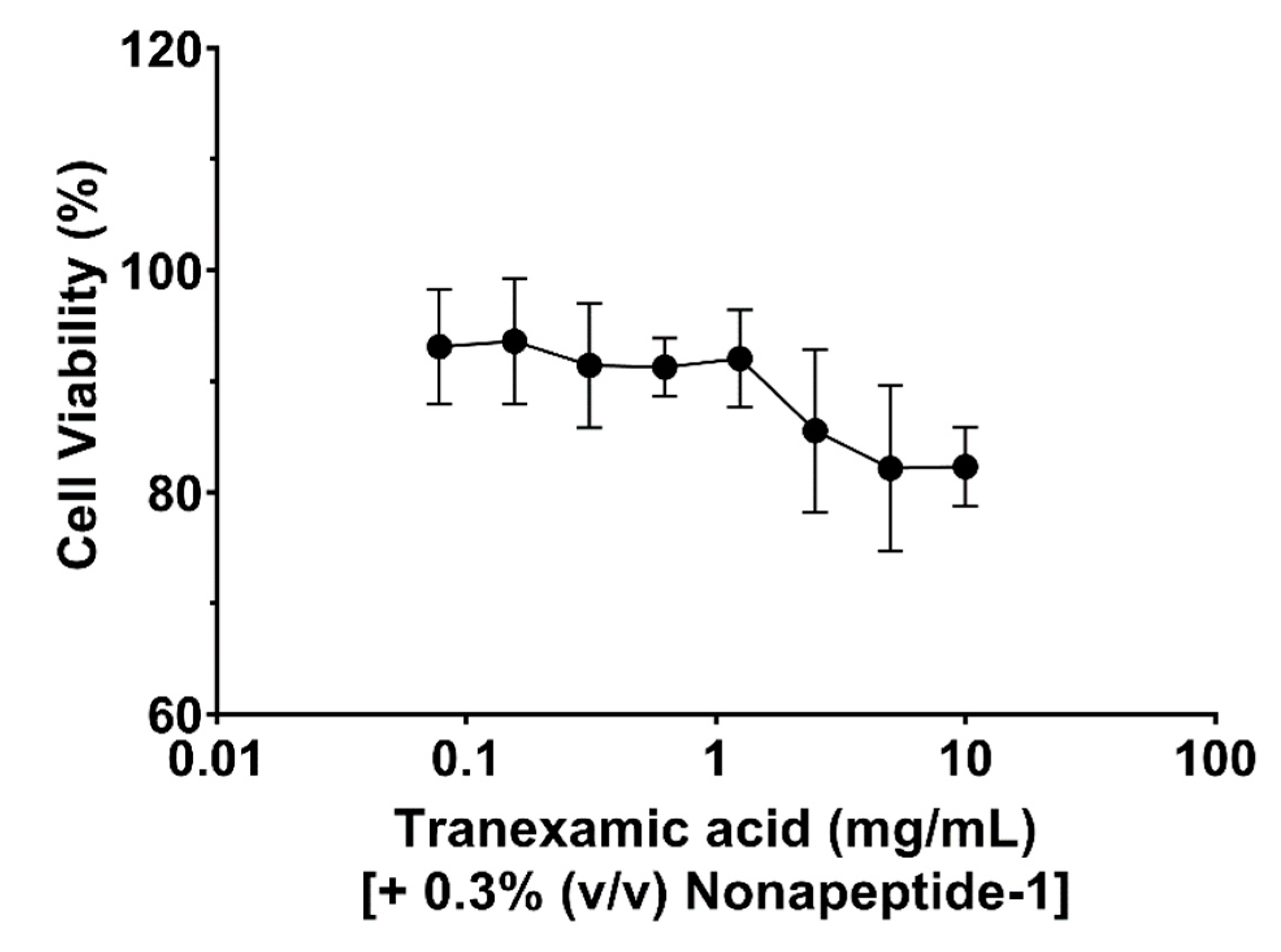

3.2. Cytotoxicity evaluation

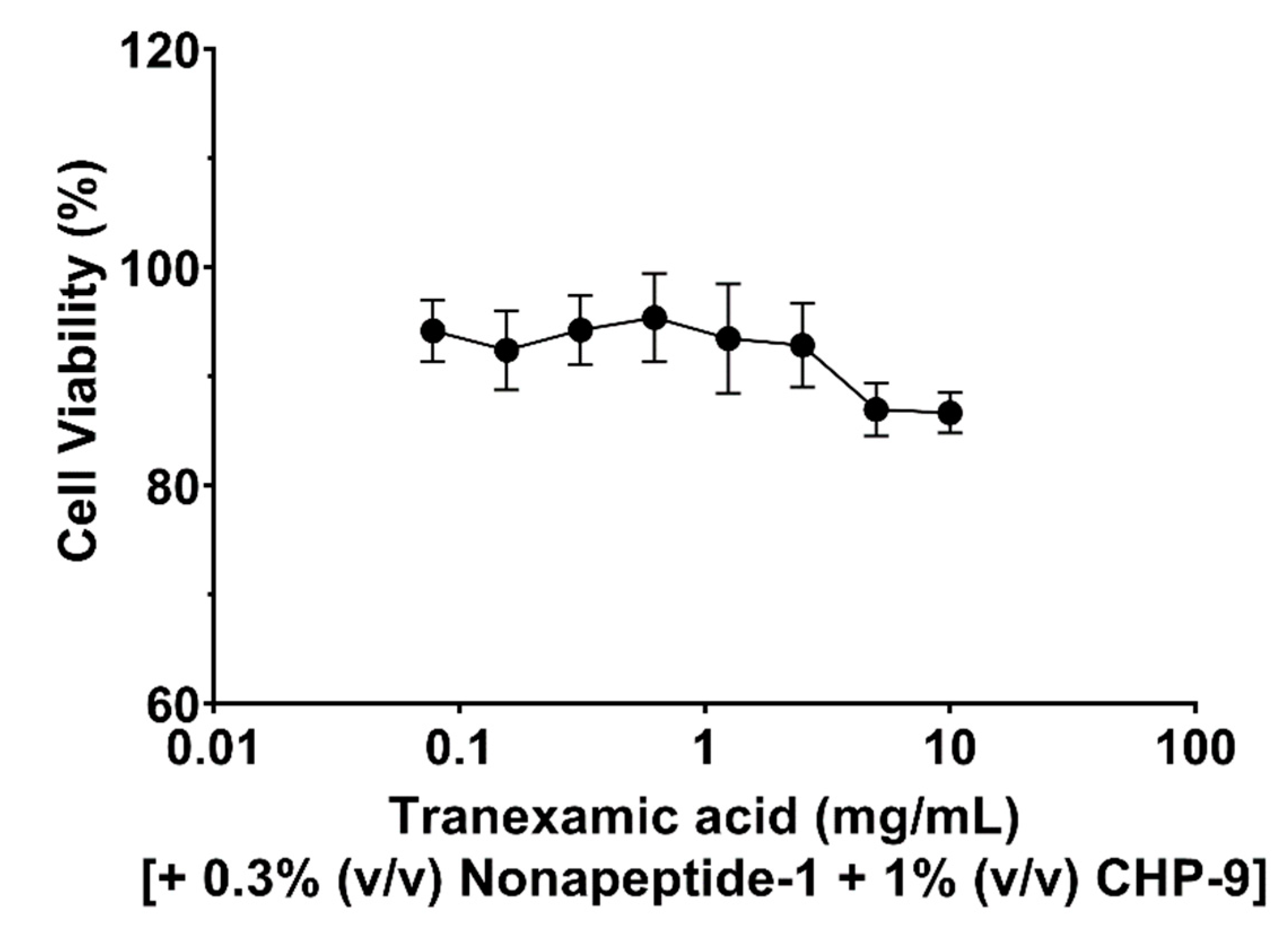

The cytotoxicity of tranexamic acid alone, tranexamic acid plus nonapeptide-1 and tranexamic acid combined with nonapeptide-1 and cyclopeptide CHP-9 were evaluated against human melanocyte cells. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the target compound did not exhibit any antiproliferative effects against the tested cell at concentrations ranging from 0.0781 to 2.5 mg/mL; this observation is supported by the fact that cell viability was more than 90% when incubated with tranexamic acid (2.5 mg/mL) concentration. The cell viability of human melanocyte cells slightly decreased when incubated with higher concentrations of the tested compound (5 mg/mL and 10 mg/mL). Additionally, incubating cells with tranexamic acid and nonapeptide-1 at 0.3% (v/v) did not influence cell viability (

Figure 2). The cytotoxicity slightly decreased when the concentration of tranexamic acid was increased to 5 mg/mL.

For the group in which human melanocyte cells were treated with tranexamic acid (1 mg/mL), nonapeptide-1 (0.3%, V/V) and cyclopeptide (CHP-1), cell viability was evaluated using the MTT assay. As shown in

Figure 3, even with the

CHP-1 concentration set at 2.5 mg/mL, the mixture did not affect cells’ growth.

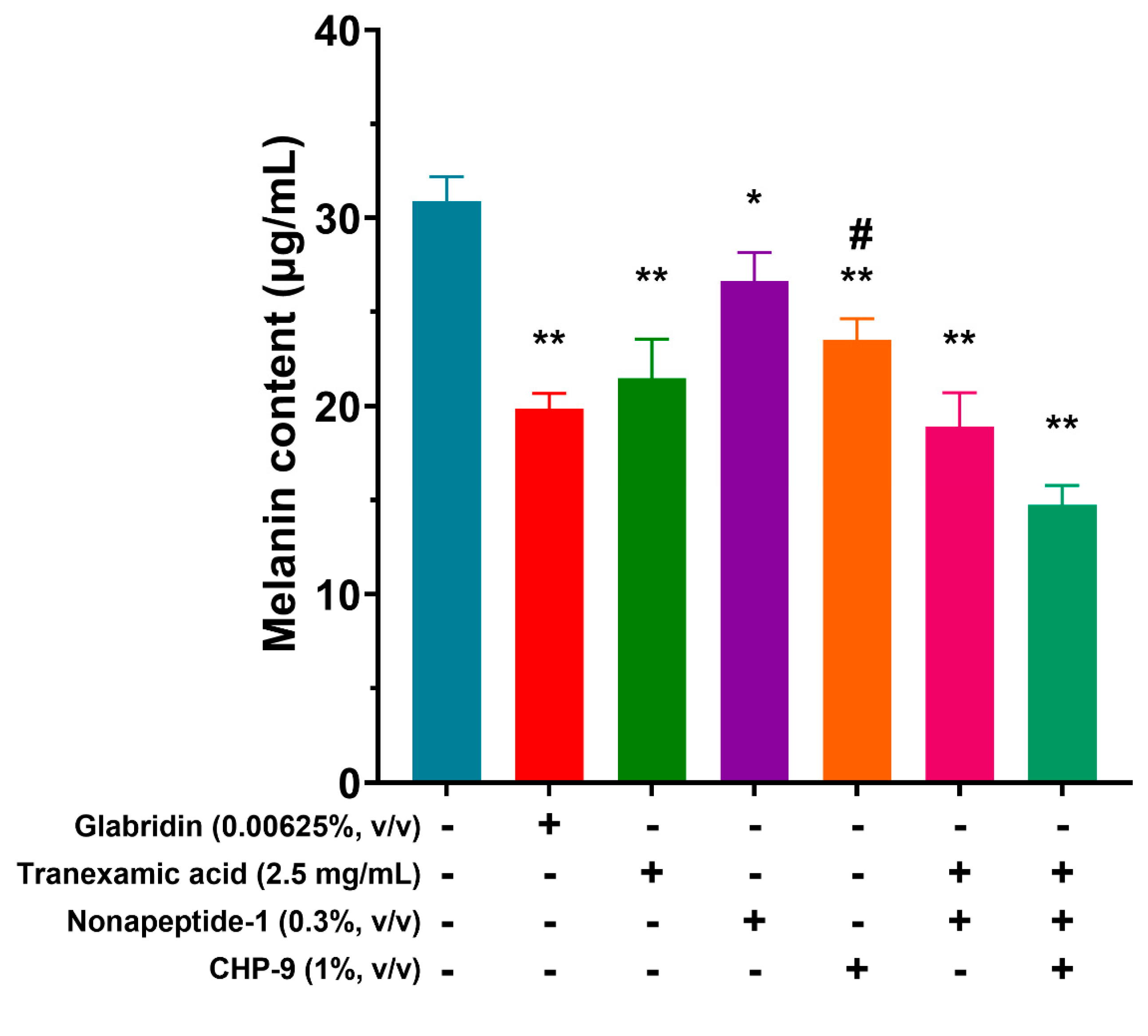

3.3. Effect of cyclopeptide on intracellular tyrosinase activity and melanin content in melanocyte cells

To evaluate the inhibiting potency of cyclopeptide and related compounds in the cellular model, the inhibitory effect of these compounds on the tyrosinase activity of human melanocytes treated with 1% cyclopeptide (

CHP-9) was examined. Exposure to

CHP-9 alone resulted in decreased melanin content from 30.90±1.13 μg/mL to 23.51±1.14 μg/mL. Compared to untreated cells (

Figure 4).

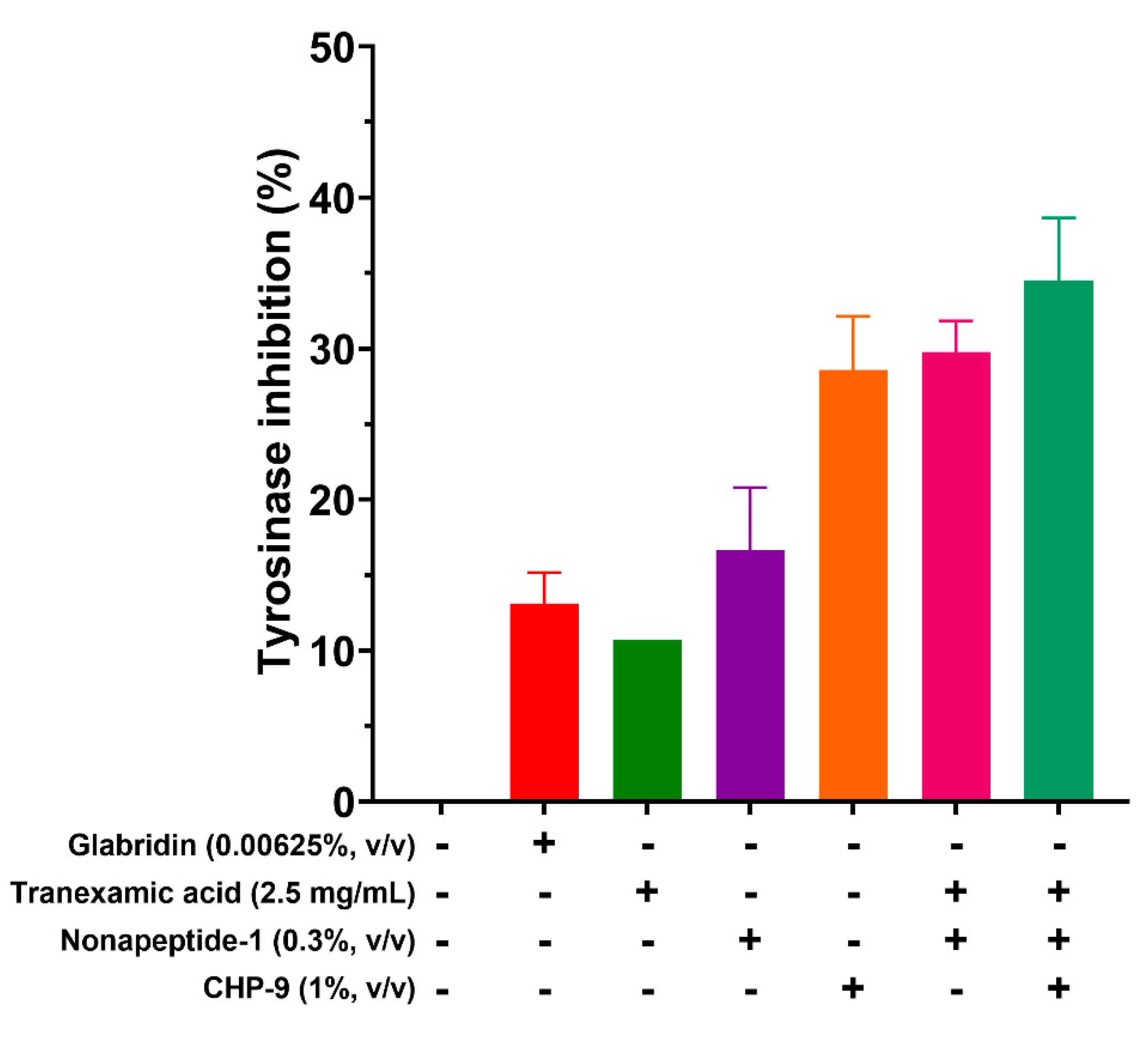

3.4. Tyrosinase inhibitory activity evaluation

Following the screening method from the previous study[

22], samples listed in

Figure 5 were assessed for their tyrosinase inhibitory activity. Glabridin was used as the positive control in the biological assay evaluation due to its established potency as a tyrosinase inhibitor[

27]. The cyclopeptide CHP-9 demonstrated significant tyrosinase inhibition with an inhibition rate of about 28.57% at the concentration of 1%. Gratifyingly, its inhibitory activity was 2-fold more potent than the positive control’s. The enzymatic inhibition rates of tranexamic acid and nonapeptide-1 were 10.71% and 16.67%, respectively, indicating good tyrosinase inhibitory activity for both compounds. Notably, the combination of tranexamic acid and nonapeptide-1 significantly enhances the enzymatic inhibition potency, achieving an inhibitory rate of 29.76%, which was slightly higher than the sum of the inhibition rate of tranexamic acid (10.71%) and nonapeptide-1 (16.67%), i.e. (27.38%). The observed incline in inhibitory rate can be ascribed to the synergistic activity of the compounds. The mixture consisting of tranexamic acid (2.5 mg/mL), nonapeptide-1 (0.3%), and cyclopeptide CHP-9 (1%) demonstrated the most potent inhibitory efficacy with an inhibition rate of 34.52%.

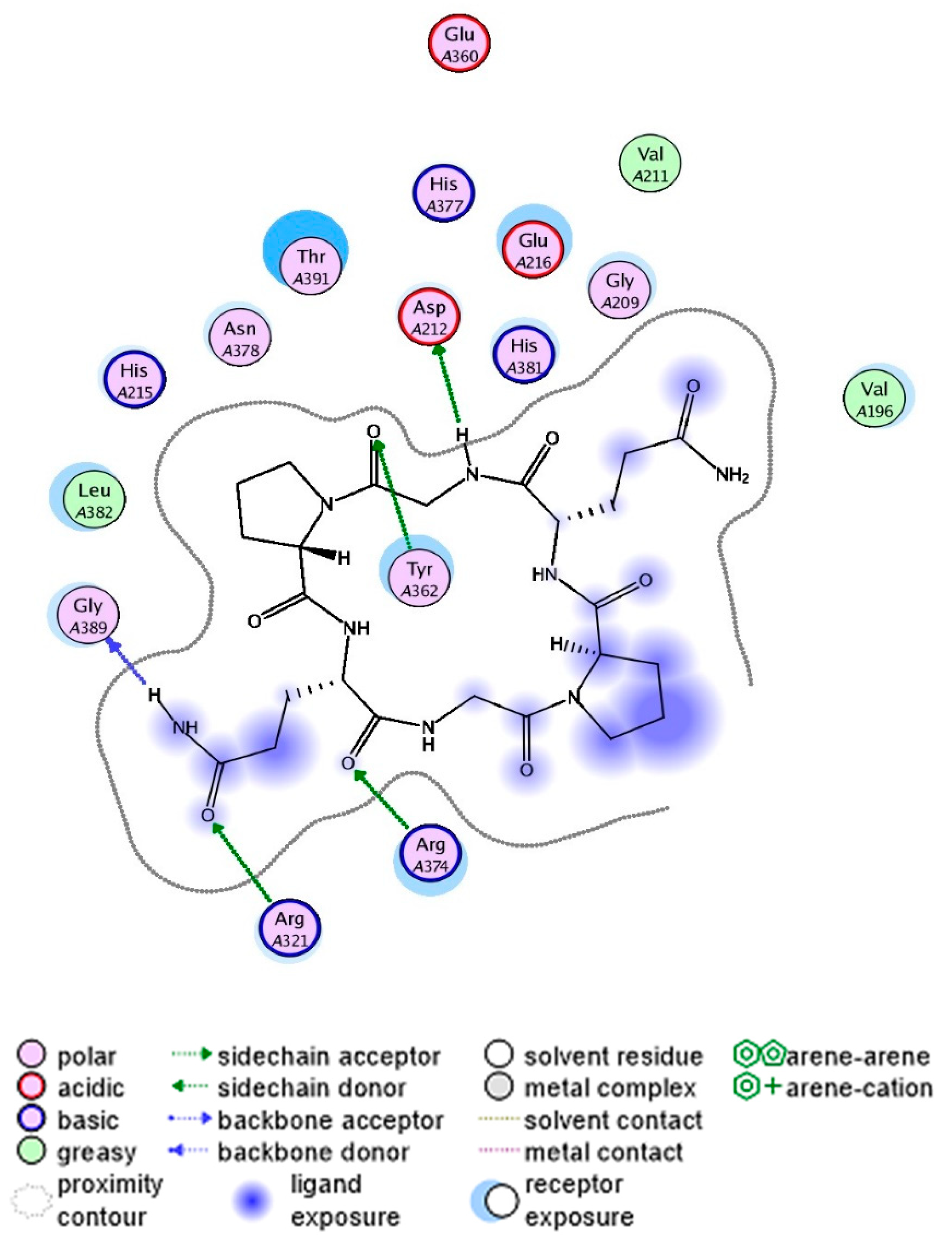

3.5. Molecular docking between the cyclopeptide and tyrosinase

Recently, computer-based simulation, known as molecular docking, has become widely used to investigate potential interaction mechanisms between inhibitors and corresponding targets. To gain insights into the molecular determinants modulating the inhibitory activity of the cyclopeptide CHP-9 against tyrosinase, we perform molecular docking studies of CHP-9 with human tyrosinase using the MOE 2008 software based on the X-ray crystal structure of human tyrosinase-related protein 1 in complex with kojic acid in the active site cavity (PDB ID: 5M8M).

As shown in

Figure 6, the cyclopeptide

CHP-9 is bound within the binding cavity, positioned above the surface of the catalytic center. Different interaction types can significantly influence the structure binding affinity and stability between the tyrosinase and

CHP-9 peptide. Specifically, a total of six hydrogen bonds were formed (one cation hydrogen bond and five conventional hydrogen bonds) between peptide

CHP-9 and tyrosinase, including 6 amino acid residues in tyrosinase, that is, Asp212, Tyr362, His321, Gly389, Arg374, and His382.

Additionally, the hydrophobic aliphatic residue leucine382 plays a pivotal role in tyrosinase inhibition by directly interacting with tyrosinase to block dopaquinone formation. Considering the results from molecular docking, cyclopeptide CHP-9 acts as a tyrosinase inhibitory peptide, and we observed that hydrogen bonding was crucial in influencing the binding affinities and structure stabilities of the peptide-tyrosinase complexes, thereby blocking the tyrosinase activity.

5. Conclusions

Since the content of melanin can directly determine the degree of skin-lightening effects of active ingredients, inhibition of melanin formation could contribute to skin lightening. This study identified a new cyclopeptide as a safe and potent human tyrosinase inhibitor. It showed potent tyrosinase inhibition with an inhibition rate of about 28.57% at the concentration of 1%. In melanin formation assay, upon exposure to CHP-9 alone, cellular melanin content decreased from 30.90±1.13 μg/mL to 23.51±1.14 μg/mL. Further, in silico molecular docking experiments were conducted to verify the tyrosinase inhibitory activity of the cyclopeptide CHP-9, and hydrogen bond was identified as the most critical force in the binding affinity of CHP-9 with the target enzyme in docking. These results suggest that the cyclopeptide CHP-9 may be helpful as a source of bioactive compounds for skin-lightening agents in cosmetics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Hu huang, Jiahua Cui and Shah Nawaz Khan; Methodology, Huailong Chang and Kan Tao; software, Jiahua Cui and Shah Nawaz Khan; validation, Huailong Chang, Kan Tao, Hu huang and Jiahua Cui; formal analysis, Jiahua Cui and Shah Nawaz Khan; investigation, Huailong Chang, Kan Tao, Hu huang and Jiahua Cui; writing—original draft preparation, Jiahua Cui and Shah Nawaz Khan; writing—review and editing, Jiahua Cui and Shah Nawaz Khan; visualization, Jiahua Cui and Shah Nawaz Khan; supervision,Jiahua Cui; project administration, Jiahua Cui and Jinping Jia; funding acquisition, Jinping Jia. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), grant number 81673281. The APC was also covered by this grant.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the Supporting Information. Further data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zolghadri, S.; Bahrami, A.; Hassan Khan, M.T.; Munoz-Munoz, J.; Garcia-Molina, F.; Garcia-Canovas, F.; et al. A comprehensive review on tyrosinase inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2019, 34, 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yan, D.; Wu, H.; Li, R.; et al. Polyphenol oxidase plays a critical role in melanin formation in the fruit skin of persimmon (Diospyros kaki cv. ‘Heishi’). Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Wichers, H.J.; Soler-Lopez, M.; Dijkstra, B.W. Structure and Function of Human Tyrosinase and Tyrosinase-Related Proteins. Chem A Eur J. 2018, 24, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Ferrer Á, Neptuno Rodríguez-López J, García-Cánovas F, García-Carmona F. Tyrosinase: a comprehensive review of its mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995, 1247, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Sugumaran, M.; Wakamatsu, K. Chemical Reactivities of ortho-Quinones Produced in Living Organisms: Fate of Quinonoid Products Formed by Tyrosinase and Phenoloxidase Action on Phenols and Catechols. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, U.K.; Ali, A.S.; Ali, A.; Naaz, I. Natural Tyrosinase Inhibitors: Role of Herbals in the Treatment of Hyperpigmentary Disorders. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2019, 19, 796–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolghadri, S.; Beygi, M.; Mohammad, T.F.; Alijanianzadeh, M.; Pillaiyar, T.; Garcia-Molina, P.; et al. Targeting tyrosinase in hyperpigmentation: Current status, limitations and future promises. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023, 212, 115574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Stehbens, S.J.; Barnard, R.T.; Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Ziora, Z.M. Dysregulation of tyrosinase activity: a potential link between skin disorders and neurodegeneration. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2024, 76, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo-Carbajal I, Laguna A, Romero-Giménez J, Cuadros T, Bové J, Martinez-Vicente M, et al. Brain tyrosinase overexpression implicates age-dependent neuromelanin production in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 973. [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-S. An Updated Review of Tyrosinase Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2009, 10, 2440–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong X, Zhu Q, Dai Y, He J, Pan H, Chen J, et al. Encapsulation artocarpanone and ascorbic acid in O/W microemulsions: Preparation, characterization, and antibrowning effects in apple juice. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 1033–1040. [CrossRef]

- Ros, J.R.; Rodríguez-López, J.N.; García-Cánovas, F. Effect of l-ascorbic acid on the monophenolase activity of tyrosinase. Biochem J. 1993, 295, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.-T.; Liang, Y.-Q.; Chai, W.-M.; Wei, Q.-M.; Yu, Z.-Y.; Wang, L.-J. Effect of ascorbic acid on tyrosinase and its anti-browning activity in fresh-cut Fuji apple. J Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanes, J.; Chazarra, S.; Garcia-Carmona, F. Kojic Acid, a Cosmetic Skin Whitening Agent, is a Slow-binding Inhibitor of Catecholase Activity of Tyrosinase. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 1994, 46, 982–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.H.; Jeon, A.R.; Mah, J.-H. Tyrosinase Inhibitory Activity of Soybeans Fermented with Bacillus subtilis Capable of Producing a Phenolic Glycoside, Arbutin. Antioxidants. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudeekulthamrong, P.; Kaulpiboon, J. Optimization of amylomaltase for the synthesis of α-arbutin derivatives as tyrosinase inhibitors. Carbohydr Res. 2020, 494, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, A.; d'Ischia, M.; Misuraca, G.; Prota, G. Mechanism of inhibition of melanogenesis by hydroquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 1991, 1073, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann T, Gerwat W, Batzer J, Eggers K, Scherner C, Wenck H, et al. Inhibition of Human Tyrosinase Requires Molecular Motifs Distinctively Different from Mushroom Tyrosinase. J Invest Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1601–1608. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Son, S.; Yun, H.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Chun, P.; Moon, H.R. Tyrosinase inhibitors: a patent review (2011-2015). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2016, 26, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, M.A.; Crist, C.M.; Devolve, N.L.; Patrone, J.D. Tyrosinase Inhibitors: A Perspective. Molecules. 2023, 28, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deri B, Kanteev M, Goldfeder M, Lecina D, Guallar V, Adir N, et al. The unravelling of the complex pattern of tyrosinase inhibition. Scientific Reports. 2016, 6, 34993. [CrossRef]

- Schurink, M.; van Berkel, W.J.H.; Wichers, H.J.; Boeriu, C.G. Novel peptides with tyrosinase inhibitory activity. Peptides. 2007, 28, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, P.-G.; Gan, C.-Y. Tyrosinase inhibitory peptides: Structure-activity relationship study on peptide chemical properties, terminal preferences and intracellular regulation of melanogenesis signaling pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2024, 1868, 130503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang C, Hu Y, Sun Y, Xiang S, Qian J, Liu Z, et al. Anti-Cancer Activity of Synthesized 5-Benzyl juglone on Selected Human Cancer Cell Lines. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2024, 24, 845–852. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Park, Y.; Park, C.; Lee, S.; Kang, D.; Yang, J.; et al. Antioxidant, anti-tyrosinase and anti-melanogenic effects of (E)-2,3-diphenylacrylic acid derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem. 2019, 27, 2192–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S. YW, Gao Y., inventor; Shanghai Baijian Biotech Co., Ltd., assignee. Cyclopeptide CHP-9 for Skin Lightening Applications. China patent CN 116284256 A. 2023.

- Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Huang, Y. Inhibitory mechanisms of glabridin on tyrosinase. Spectrochim Acta A: Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2016, 168, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).