1. Introduction

Contemporary medical education faces unprecedented challenges: exponential growth of scientific knowledge, rapidly evolving healthcare technologies, and increasing complexity of healthcare systems. These developments necessitate innovative pedagogical approaches that transcend traditional didactic methods of instruction. Problem-Based Learning (PBL) has emerged as a response to these challenges, offering a student-centered ap-proach that prioritizes active knowledge construction over passive information reception.

PBL represents a significant paradigm shift in medical education, transitioning from teacher-centered to learner-centered approaches. This methodology is characterized by collaborative learning in small groups, where students encounter authentic clinical prob-lems that serve as catalysts for knowledge acquisition, integration, and application (Bar-rows, 1986). Several authoritative definitions help illuminate the essential characteristics of PBL:

Barrows (1986) defined PBL as ”a method of learning based on the principle of using problems as a starting point for the acquisition and integration of new knowledge.”

Hmelo-Silver (2004) characterized PBL as ”an instructional method in which stu-dents learn through facilitated problem solving that centers on a complex problem that does not have a single correct answer.”

Dolmans et al. (2005) described PBL as ”an approach to learning and instruction in which students tackle problems in small groups under the supervision of a tutor.”

This review aims to provide a comprehensive examination of PBL in medical educa-tion, analyzing its theoretical foundations, implementation methodology, and empirical evidence for effectiveness. Furthermore, we explore the challenges associated with PBL implementation and propose evidence-based strategies to overcome these barriers. By synthesizing current research and practical experiences, this article contributes to the ongoing discourse on optimizing medical education to prepare physicians capable of de-livering high-quality care in increasingly complex healthcare environments.

2. Historical Development of PBL in Medical Education

Problem-Based Learning emerged in the late 1960s at McMaster University’s Faculty of Medicine in Canada, representing a revolutionary departure from traditional medical education paradigms. Its development was catalyzed by a growing recognition that con-ventional teaching methods—characterized by passive knowledge transmission and com-partmentalized disciplines—were inadequate for preparing physicians to address the com-plexities of clinical practice (Schmidt et al., 2011).

The McMaster model, pioneered by Howard Barrows and colleagues, introduced sev-eral innovative elements that would become defining features of PBL: small group tutori-als, authentic clinical problems as learning stimuli, student-directed inquiry, and faculty as facilitators rather than information providers (Barrows, 1986). This approach was designed to enhance students’ motivation and facilitate deeper learning by contextual-izing knowledge acquisition within realistic clinical scenarios from the outset of medical training.

Following its introduction at McMaster, PBL was adopted by other institutions glob-ally, notably Maastricht University in the Netherlands, Newcastle University in Australia, and Harvard Medical School in the United States. Each institution adapted the core prin-ciples to their specific educational contexts, leading to various implementation models while maintaining the fundamental characteristics of PBL (Savin Baden Major, 2004).

The historical trajectory of PBL reflects broader shifts in educational philosophy to-ward constructivist approaches to learning. The methodology has evolved in response to empirical research, practical experience, and emerging educational technologies, while maintaining its core emphasis on active, self-directed, and collaborative learning (Hmelo Silver, 2004).

In the decades since its inception, PBL has expanded beyond medicine to numerous disciplines, including nursing, dentistry, pharmacy, engineering, and business. However, its most profound impact and extensive implementation remain within medical education, where it continues to influence curriculum design and pedagogical approaches worldwide.

3. Theoretical Foundations of PBL

The effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning is underpinned by robust educational theo-ries that explain its capacity to facilitate deep learning and develop essential professional competencies. Understanding these theoretical foundations is crucial for optimal imple-mentation and adaptation of PBL within medical curricula.

3.1. Constructivist Learning Theory

PBL is fundamentally grounded in constructivist epistemology, which posits that knowl-edge is not passively received but actively constructed by learners through interaction with their environment and integration with existing cognitive structures (Hmelo Silver, 2004). In the PBL context, students construct knowledge by:

Actively engaging with authentic clinical problems

Drawing on prior knowledge to formulate initial hypotheses

Identifying knowledge gaps that drive further inquiry

Integrating new information with existing cognitive frameworks

This constructivist approach contrasts sharply with the ”empty vessel” model im-plicit in traditional didactic teaching, instead recognizing learners as active participants in knowledge creation.

3.2. Social Cognitive Theory and Situated Learning

Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory and the concept of situated learning are evident in PBL’s emphasis on collaborative knowledge construction within a contextualized environment (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006). These theories recognize that learning is inherently social and optimized when:

Knowledge is constructed through social interaction

Learning occurs within relevant professional contexts

Cognitive development is facilitated through guidance from more knowledgeable peers (the ”zone of proximal development”)

Communities of practice develop through shared problem-solving

The small-group format of PBL creates a microcosm of clinical practice communities, where knowledge is negotiated, refined, and applied collaboratively.

3.3. Adult Learning Theory and Self-Directed Learning

Malcolm Knowles’ principles of andragogy (adult learning) align closely with PBL method-ology, particularly in its emphasis on self-directed learning and intrinsic motivation (Wood, 2003). PBL incorporates key principles of adult learning by:

Acknowledging learners’ existing knowledge and experiences

Emphasizing relevance through authentic clinical problems

Promoting autonomy in identifying learning needs and resources

Facilitating immediate application of knowledge to problem-solving

Fostering internal motivation through cognitive challenge

These principles are particularly significant in medical education, where fostering life-long learning habits is essential for keeping pace with rapidly evolving medical knowledge.

3.4. Cognitive Load Theory and PBL

Cognitive load theory offers important insights for PBL design, emphasizing the need to balance intrinsic cognitive load (inherent problem complexity), extraneous cognitive load (unnecessary processing demands), and germane cognitive load (productive cognitive pro-cesses that contribute to learning) (Dolmans et al., 2005). Effective PBL implementation must:

Present problems with appropriate complexity for learners’ current knowledge level

Provide sufficient scaffolding to prevent cognitive overload

Minimize extraneous cognitive load through clear problem formulation

Optimize germane cognitive load through carefully designed learning activities

These theoretical frameworks collectively provide a robust foundation for understand-ing why PBL is effective and how it can be optimally implemented. The integration of these theories in PBL design facilitates not only knowledge acquisition but also the de-velopment of critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and self-directed learning skills essential for medical practice.

4. Comparative Analysis of PBL and Traditional Teach-ing Methods

Problem-Based Learning represents a paradigm shift from traditional teaching approaches in medical education. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for educators considering curricular innovations.

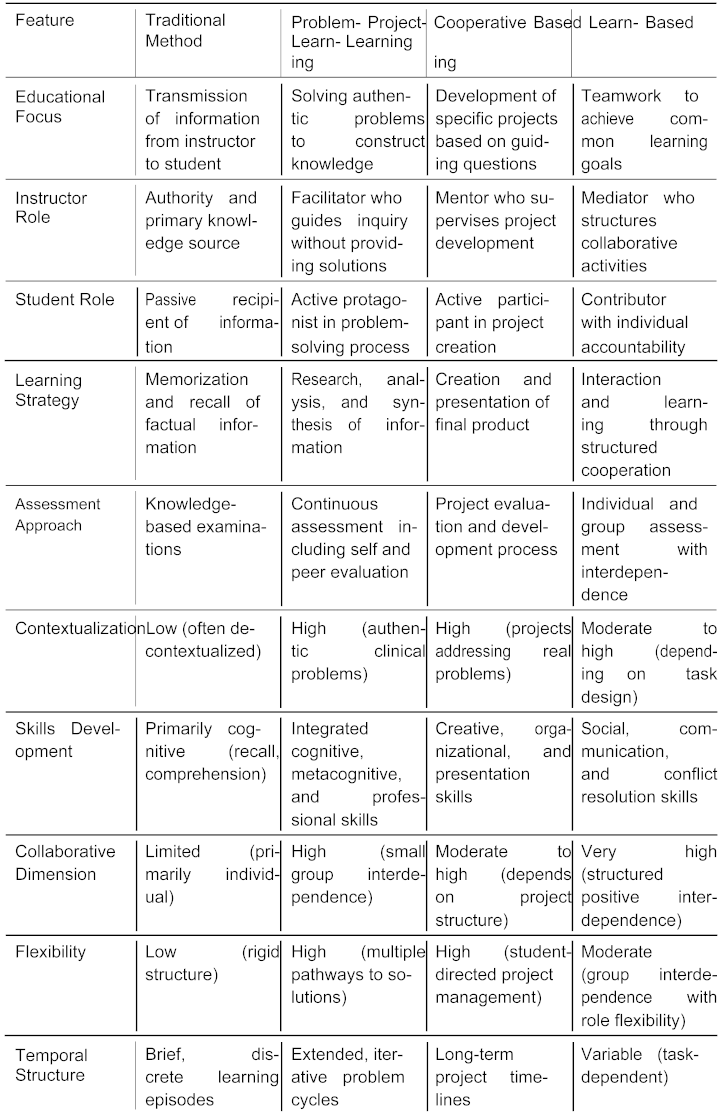

Table 1 presents a comprehensive comparison of key elements across different educational methodologies.

This comparative analysis highlights several distinguishing features of PBL that confer particular advantages in medical education:

Authenticity and Clinical Relevance: Unlike traditional methods that often present decontextualized knowledge, PBL embeds learning within authentic clinical sce-narios that mirror the complexity and ambiguity of actual medical practice (Dolmans et al., 2005). This contextualization enhances knowledge transfer to clinical settings.

Integration of Basic and Clinical Sciences: PBL naturally bridges the traditional divide between preclinical and clinical education by requiring students to apply biomedical concepts to clinical problems from the outset of their training (Schmidt et al., 2011). This integration facilitates the development of elaborate knowledge networks that enhance clinical reasoning.

Development of Self-Regulated Learning Skills: The self-directed nature of PBL cultivates metacognitive abilities and information literacy skills essential for lifelong learning in medicine (Hmelo Silver, 2004). These competencies are increasingly crucial as medical knowledge continues to expand exponentially.

Enhanced Engagement and Motivation: The authentic problems and collabora-tive dynamics of PBL typically generate higher levels of student engagement and intrinsic motivation compared to traditional lecture-based approaches (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006). This engagement contributes to deeper processing and retention of information.

While traditional teaching methods may be more efficient for transmitting large vol-umes of factual knowledge, PBL offers superior opportunities for developing integrated understanding, clinical reasoning, and professional competencies. The optimal approach may involve strategic integration of these methods within a comprehensive curriculum, leveraging the strengths of each according to specific learning objectives.

5. Implementation Methodology

Effective implementation of Problem-Based Learning requires structured processes and clear role definitions. This section outlines evidence-based approaches to PBL implemen-tation in medical education.

5.1. The PBL Process

While various models of PBL implementation exist, the most widely adopted is the seven-step approach developed at Maastricht University (Wood, 2003):

Problem Presentation: Students are presented with an authentic clinical scenario designed to trigger discussion and activate prior knowledge.

Clarification of Terms: Unfamiliar terms or concepts in the problem are identified and clarified to ensure shared understanding.

Problem Analysis: The group analyzes the problem, identifying key issues, po-tential causes, and relationships between different aspects of the scenario.

Hypothesis Generation: Students propose possible explanations or solutions based on existing knowledge, generating a provisional conceptual model.

Formulation of Learning Objectives: Knowledge gaps are identified and trans-lated into specific learning objectives that will guide independent study.

Independent Self-Study: Students individually research the learning objectives using various resources, preparing to share findings with the group.

Synthesis and Application: The group reconvenes to share findings, synthesize new knowledge, apply it to the original problem, and evaluate the learning process.

This iterative process typically spans multiple sessions, allowing for progressive knowl-edge construction and application. Variations of this model have been developed to ac-commodate different institutional contexts and curricular constraints, including ”one-day-one-problem” approaches and adapted formats for larger groups (Schmidt et al., 2011).

5.2. Roles and Responsibilities

The effectiveness of PBL depends on clear understanding of the roles and responsibilities of all participants:

5.2.1. The PBL Tutor

The tutor role in PBL differs significantly from traditional teaching roles, focusing on facilitation rather than direct instruction (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006). Effective PBL tutors:

Guide the learning process without dominating group discussions

Stimulate critical thinking through strategic questioning

Monitor group dynamics and ensure balanced participation

Provide process-oriented feedback rather than content-focused evaluation

Model reflective practice and metacognitive approaches

Research indicates that tutors need not be subject matter experts in every case, though they must possess sufficient knowledge to recognize erroneous reasoning and guide stu-dents toward appropriate resources (Schmidt et al., 2011). More critical than content expertise is skill in facilitation and understanding of the PBL process.

5.2.2. The Student Role

PBL places significant responsibility on students as active participants in knowledge con-struction (Hmelo Silver, 2004). Students must:

Actively contribute to group discussions and problem analysis

Identify personal and group learning needs

Independently locate, evaluate, and synthesize information

Share knowledge effectively with peers

Reflect on their learning process and outcomes

Provide constructive feedback to peers

This active role represents a significant shift from traditional educational expecta-tions and may require explicit orientation and scaffolding, particularly for students from educational backgrounds that emphasized passive learning approaches.

5.2.3. Case Design

The quality of problems presented in PBL significantly influences learning outcomes (Dol-mans et al., 2005). Effective PBL cases exhibit the following characteristics:

Authenticity: Cases should reflect real-world clinical scenarios with appropriate complexity

Alignment with learning objectives: Problems should naturally lead students toward intended curricular outcomes

Open-ended structure: Cases should permit multiple approaches and solutions

Integration of multiple disciplines: Problems should require knowledge from various biomedical and clinical domains

Progressive disclosure: Information may be revealed sequentially to mirror clinical reasoning processes

Engaging context: Cases should capture student interest and demonstrate relevance to future practice

Carefully designed problems serve as the foundation for successful PBL implementa-tion, requiring significant faculty development and collaborative design processes.

6. Assessment in PBL

Assessment in Problem-Based Learning requires approaches aligned with its constructivist philosophy and emphasis on process skills alongside knowledge acquisition. Traditional assessment methods focused primarily on knowledge recall are insufficient for evaluating the multidimensional competencies developed through PBL (Dolmans et al., 2005).

6.1. Principles of Assessment in PBL

Effective assessment in PBL curricula adheres to several key principles:

Constructive Alignment: Assessment tasks should reflect the active, constructive learning processes emphasized in PBL (Wood, 2003).

Authenticity: Assessment scenarios should mirror the complexity and contextu-alization of real clinical problems (Schmidt et al., 2011).

Multiple Dimensions: Assessment should address knowledge acquisition along-side the development of clinical reasoning, self-directed learning skills, and collabo-rative abilities (Hmelo Silver, 2004).

Continuity: Ongoing formative assessment should be integrated throughout the learning process, not limited to summative evaluation (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006).

Triangulation: Multiple assessment methods and perspectives should be incorpo-rated to develop comprehensive understanding of student competence (Dolmans et al., 2005).

6.2. Assessment Methods in PBL

A comprehensive PBL assessment strategy typically incorporates multiple complementary methods:

6.2.1. Formative Assessment

Formative assessment focuses on providing feedback to guide ongoing learning and in-cludes:

Tutor Observations: Structured observation of student participation in group processes, with feedback on problem-solving approaches, contribution quality, and collaboration skills (Wood, 2003).

Self-Assessment: Guided reflection on learning processes, knowledge acquisition, and skill development, fostering metacognitive development (Hmelo Silver, 2004).

Peer Assessment: Structured evaluation by group members, providing multiple perspectives on collaborative contributions and professional behaviors (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006).

Learning Portfolios: Curated collections of work that document learning trajec-tories and provide evidence of knowledge and skill development over time (Schmidt et al., 2011).

6.2.2. Summative Assessment

Summative assessment evaluates achievement of learning outcomes and includes:

Modified Essay Questions (MEQs): Sequential case-based questions that assess clinical reasoning processes alongside knowledge application (Wood, 2003).

Triple Jump Exercises: Three-stage assessments involving initial problem anal-ysis, independent research, and subsequent problem resolution, mirroring the PBL process (Schmidt et al., 2011).

Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs): Standardized patient encounters that assess integrated clinical competencies in authentic contexts (Dol-mans et al., 2005).

Progress Testing: Longitudinal assessment of knowledge growth through periodic comprehensive examinations spanning the curriculum (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006).

6.3. Assessment Challenges in PBL

Despite significant advances in PBL assessment, several challenges persist:

Resource Intensity: Comprehensive, authentic assessment requires significant fac-ulty time and institutional resources (Dolmans et al., 2005).

Reliability Concerns: Assessments of complex competencies and group processes may face challenges in achieving acceptable reliability (Schmidt et al., 2011).

Cultural Transitions: Implementing innovative assessment approaches often re-quires cultural shifts within institutions and examination systems (Wood, 2003).

Balancing Formative and Summative Purposes: Maintaining the develop-mental benefits of assessment while meeting certification requirements presents on-going tensions (Hmelo Silver, 2004).

Addressing these challenges requires institutional commitment to assessment devel-opment, faculty training, and ongoing evaluation of assessment practices. Despite these challenges, appropriately designed assessment systems are essential for realizing the full potential of PBL in developing future physicians with the complex competencies required for contemporary healthcare.

7. Evidence for Effectiveness

The effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning in medical education has been extensively investigated through empirical research. This section synthesizes findings from meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and longitudinal studies to evaluate the impact of PBL on various educational outcomes.

7.1. Knowledge Acquisition and Retention

Evidence regarding knowledge acquisition in PBL compared to traditional curricula presents a nuanced picture:

Meta-analyses indicate that students in PBL curricula may perform slightly lower on conventional knowledge tests in basic sciences during their preclinical years (Dol-mans et al., 2005).

However, longitudinal studies demonstrate superior knowledge retention among PBL graduates, with significantly better recall of concepts during clinical years and beyond graduation (Schmidt et al., 2011).

PBL appears particularly effective for promoting conceptual understanding and knowledge application rather than factual recall in isolation (Hmelo Silver, 2004).

Research suggests that PBL fosters more elaborated and integrated knowledge struc-tures that support clinical reasoning and knowledge transfer (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006).

These findings suggest that while PBL may not optimize short-term factual knowl-edge acquisition, it enhances long-term knowledge retention and application—outcomes arguably more relevant to clinical practice.

7.2. Clinical Reasoning and Problem-Solving

PBL demonstrates considerable strengths in developing clinical reasoning abilities:

Multiple studies indicate that PBL graduates demonstrate superior diagnostic rea-soning, particularly in managing complex and ambiguous clinical presentations (Schmidt et al., 2011).

PBL students typically develop more hypothesis-driven approaches to clinical prob-lems, generating broader differential diagnoses (Dolmans et al., 2005).

Longitudinal assessments show that PBL graduates are more likely to integrate biopsychosocial perspectives in their clinical reasoning compared to traditionally trained physicians (Wood, 2003).

Research indicates that PBL enhances adaptive expertise—the ability to apply knowledge flexibly to novel situations—a critical competency for clinical practice (Hmelo Silver, 2004).

The emphasis on authentic problem-solving and clinical contextualization in PBL appears to foster reasoning patterns that align well with the demands of clinical practice.

7.3. Self-Directed Learning Skills

PBL consistently demonstrates positive effects on the development of self-directed learning competencies:

Comparative studies show that PBL graduates report greater confidence and com-petence in identifying learning needs and locating appropriate resources (Schmidt et al., 2011).

PBL students demonstrate more sophisticated information literacy skills, including critical appraisal of evidence (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006).

Longitudinal research indicates that physicians trained in PBL curricula engage more actively in continuing professional development activities (Wood, 2003).

Studies show enhanced metacognitive awareness among PBL students, including more accurate self-assessment of knowledge limitations (Hmelo Silver, 2004).

These self-directed learning competencies are increasingly vital in a healthcare envi-ronment characterized by rapidly evolving knowledge and practice guidelines.

7.4. Professional and Interpersonal Skills

Evidence suggests that PBL contributes to the development of essential professional com-petencies:

Comparative studies indicate that PBL graduates demonstrate enhanced communi-cation skills, particularly in patient-centered communication (Dolmans et al., 2005).

PBL appears to foster more positive attitudes toward teamwork and interprofes-sional collaboration (Schmidt et al., 2011).

Research shows that PBL students develop stronger self-efficacy and tolerance for ambiguity—psychological attributes important for clinical practice (Hmelo Silver, 2004).

Studies indicate that PBL graduates report greater preparedness for the transition to clinical practice compared to traditionally trained peers (Wood, 2003).

The collaborative nature of PBL and its emphasis on authentic problems appear to support the development of professional competencies beyond knowledge acquisition.

7.5. Limitations of Current Evidence

Despite substantial research supporting PBL effectiveness, several limitations in the evi-dence base should be acknowledged:

Heterogeneity in PBL implementation makes cross-study comparisons challenging (Dolmans et al., 2005).

Many studies rely on self-reported outcomes or proximate measures rather than direct assessment of clinical performance (Schmidt et al., 2011).

Institutional contexts and concurrent curricular changes often confound attempts to isolate the specific effects of PBL (Wood, 2003).

Long-term outcomes, including impacts on patient care quality, remain understudied (Hmelo Silver, 2004).

Despite these limitations, the preponderance of evidence supports the conclusion that PBL effectively develops key competencies for medical practice, particularly when imple-mented with fidelity to its core principles.

8. Development of Autonomous Learning Skills in PBL

Problem-Based Learning fundamentally transforms the development of self-regulated learn-ing capabilities—a critical competency for physicians who must maintain professional competence throughout their careers. This section examines how PBL systematically cultivates autonomous learning skills through its structure and processes.

8.1. Theoretical Framework for Autonomous Learning

Autonomous learning in medical education refers to the ability of learners to take initiative and responsibility for their learning processes (Hmelo Silver, 2004). This capacity involves:

Accurately identifying knowledge gaps and learning needs

Setting appropriate learning goals and priorities

Selecting effective learning strategies and resources

Monitoring understanding and progress toward goals

Evaluating learning outcomes and adapting approaches accordingly

These metacognitive capabilities are essential for physicians practicing in a field char-acterized by continuous knowledge evolution and increasing complexity (Wood, 2003). Beyond medical knowledge acquisition, autonomous learning skills enable practitioners to adapt to emerging evidence, new technologies, and evolving healthcare environments throughout their careers.

8.2. PBL Components That Foster Autonomous Learning

Several structural elements of PBL systematically develop autonomous learning capacities:

8.2.1. Self-Identified Learning Needs

The PBL process explicitly requires students to identify their knowledge gaps through problem analysis:

Students must determine what they need to know to address the problem effectively

Learning needs emerge authentically from the problem context rather than external prescription

The discrepancy between current knowledge and problem requirements creates cog-nitive dissonance that motivates learning

This approach contrasts sharply with traditional curricula where learning objectives are entirely predetermined and externally imposed (Dolmans et al., 2005).

8.2.2. Independent Information Seeking

PBL requires students to develop sophisticated information literacy skills:

Students must locate relevant, credible resources independently

Critical evaluation of information quality and relevance is essential

Synthesis of information from multiple sources is required

Strategic time management becomes necessary when navigating extensive informa-tion resources

These skills directly parallel the information challenges faced by practicing clinicians navigating the medical literature (Schmidt et al., 2011).

8.2.3. Reflection and Self-Assessment

PBL incorporates structured reflection that develops metacognitive awareness:

Post-problem reflection on the adequacy of knowledge acquired

Critical assessment of learning strategies employed

Evaluation of individual and group contributions to problem resolution

Identification of persistent knowledge gaps requiring attention

These reflective processes cultivate the habit of continuous self-assessment essential for self-regulated professional development (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006).

8.3. Empirical Evidence for Autonomous Learning Development

Research demonstrates that PBL effectively fosters autonomous learning capabilities:

Longitudinal studies show that PBL graduates report greater preparedness for self-directed learning in clinical practice compared to traditional curriculum graduates (Schmidt et al., 2011)

PBL students demonstrate more sophisticated resource selection strategies and criti-cal appraisal skills when addressing unfamiliar clinical problems (Hmelo Silver, 2004)

Graduates from PBL curricula show higher rates of engagement with continuing medical education and evidence-based practice initiatives (Wood, 2003)

PBL students develop more accurate calibration between perceived and actual knowl-edge—a crucial metacognitive skill for identifying learning needs (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006)

8.4. Scaffolding Autonomous Learning Development

While PBL inherently promotes autonomous learning, effective implementation requires deliberate scaffolding, particularly for students transitioning from traditional educational environments:

Progressive reduction in structural guidance as students develop competence

Explicit modeling of information-seeking and critical appraisal strategies

Coaching in reflective practice and self-assessment techniques

Constructive feedback on learning process alongside content mastery

Development of metacognitive awareness through structured prompts and questions

This scaffolding acknowledges that autonomous learning is a developmental skill re-quiring deliberate cultivation rather than an innate capacity (Dolmans et al., 2005).

The development of autonomous learning capabilities represents one of PBL’s most significant contributions to medical education. By systematically cultivating these skills throughout the curriculum, PBL prepares physicians capable of maintaining competence through self-directed, lifelong learning—an essential capacity for providing quality care in an ever-evolving healthcare landscape.

9. Challenges and Strategies in PBL Implementation

Despite the demonstrated benefits of Problem-Based Learning, its implementation in medical education presents significant challenges. This section identifies common barriers and evidence-based strategies for addressing them.

9.1. Institutional Challenges

9.1.1. Resource Requirements

PBL implementation requires substantial resources that may strain institutional budgets:

Higher faculty-to-student ratios for small group facilitation

Additional physical spaces configured for group work

Development of quality PBL cases and supporting materials

Faculty development programs for tutor training

Strategic approaches: Institutions can consider hybrid models that combine PBL with other teaching methods, gradually phase in PBL components, utilize peer tutoring for advanced students, and develop shared case repositories across institutions (Dolmans et al., 2005).

9.1.2. Organizational Culture

Resistance to educational change is common and may manifest at multiple levels:

Faculty accustomed to content expertise rather than facilitation roles

Departmental structures that reinforce disciplinary silos

Institutional assessment systems aligned with traditional educational paradigms

Concerns about curriculum coverage and knowledge acquisition

Strategic approaches: Successful implementation requires establishing clear vision and leadership support, engaging key stakeholders in design processes, providing com-pelling evidence for effectiveness, celebrating early successes, and ensuring alignment be-tween curriculum, assessment, and institutional values (Schmidt et al., 2011).

9.2. Faculty Challenges

9.2.1. Role Transition

The shift from content expert to facilitator represents a significant professional identity transition for many faculty members:

Discomfort with reduced content control and authority

Uncertainty about facilitation techniques and appropriate interventions

Challenges in balancing process facilitation with content guidance

Concerns about ability to evaluate student learning effectively

Strategic approaches: Comprehensive faculty development programs should include experiential PBL participation, observation of skilled facilitators, practice with feedback, reflection on teaching beliefs, and ongoing mentoring and peer support (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006).

9.2.2. Assessment Competencies

PBL requires assessment approaches that many faculty lack experience implementing:

Unfamiliarity with formative assessment techniques

Limited expertise in evaluating process skills and group dynamics

Challenges in designing authentic, integrated assessments

Concerns about reliability and fairness in more subjective evaluations

Strategic approaches: Faculty development should include specific training in PBL assessment, opportunities to calibrate evaluations through group review of student work, development of structured assessment rubrics, and mentoring from experienced PBL as-sessors (Hmelo Silver, 2004).

9.3. Student Challenges

9.3.1. Learning Strategy Adaptation

Many students enter medical education with learning strategies optimized for traditional educational approaches:

Dependence on external direction rather than self-regulated learning

Preference for clear scope definitions and explicit expectations

Study habits focused on memorization rather than conceptual understanding

Limited experience with collaborative learning approaches

Strategic approaches: Explicit orientation to PBL methodology, progressive scaf-folding of self-directed learning skills, metacognitive coaching, and transparent alignment between PBL activities and assessment can facilitate student adaptation (Wood, 2003).

9.3.2. Group Dynamic Challenges

PBL’s collaborative nature introduces interpersonal variables that can impact learning effectiveness:

Uneven participation and contribution among group members

Social loafing or domination by individual students

Interpersonal conflicts that distract from learning objectives

Variable quality of peer teaching and feedback

Strategic approaches: Establishing clear ground rules for group interaction, teach-ing conflict resolution strategies, implementing structured roles that rotate among stu-dents, incorporating peer evaluation components, and providing tutor guidance on group process can mitigate these challenges (Dolmans et al., 2005).

9.4. Curriculum Design Challenges

9.4.1. Integration Across Disciplines

PBL requires integration across traditional disciplinary boundaries:

Coordination challenges between basic science and clinical departments

Content territoriality and concern about disciplinary representation

Logistical complexities in scheduling integrated sessions

Ensuring systematic coverage of essential content

Strategic approaches: Establishing cross-disciplinary curriculum teams, developing explicit curriculum mapping to ensure comprehensive coverage, creating shared owner-ship through collaborative case development, and implementing systematic blueprinting processes can facilitate effective integration (Schmidt et al., 2011).

9.4.2. Scaling to Larger Cohorts

Many institutions face challenges implementing PBL with large student cohorts:

Insufficient qualified tutors for multiple small groups

Limited appropriate physical spaces for concurrent group sessions

Coordination and quality control across multiple concurrent groups

Resource-intensive nature of comprehensive PBL implementation

Strategic approaches: Modified PBL approaches for larger groups, strategic com-bination with other teaching methods in hybrid curricula, use of technology to support aspects of the PBL process, and implementation of tutor training programs for senior students and residents can address scaling challenges (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006).

These implementation challenges highlight the need for context-specific adaptation of PBL principles. While maintaining fidelity to core PBL concepts is important, success-ful implementation requires thoughtful consideration of institutional context, available resources, faculty capabilities, and student characteristics.

10. PBL in Clinical Reasoning Development

Clinical reasoning—the cognitive process by which clinicians gather and integrate infor-mation to make diagnostic and therapeutic decisions—represents a core competency for medical practice. Problem-Based Learning offers particular advantages for developing these complex reasoning skills through its structure and processes.

10.1. Clinical Reasoning Processes

Clinical reasoning encompasses multiple interrelated cognitive processes:

Hypothesis generation: Formulating potential explanations for clinical presen-tations

Data gathering: Collecting relevant information through history, examination, and investigations

Pattern recognition: Identifying characteristic clusters of clinical findings

Hypothesis evaluation: Weighing evidence for and against potential diagnoses

Diagnostic verification: Confirming diagnoses through definitive testing or re-sponse to treatment

Therapeutic decision-making: Selecting appropriate interventions based on di-agnosis and patient factors

These processes require the integration of biomedical knowledge, clinical experience, and analytical thinking (Schmidt et al., 2011).

10.2. Alignment Between PBL and Clinical Reasoning Develop-ment

Problem-Based Learning closely parallels authentic clinical reasoning processes in several ways:

10.2.1. Problem Presentation and Initial Hypothesis Generation

PBL begins with case presentation, mirroring the initial patient encounter in clinical practice:

Students practice generating initial hypotheses from limited information

Early pattern recognition skills develop through exposure to multiple cases

The importance of systematic approaches to clinical problems is reinforced

This process develops the habit of immediate engagement with clinical data and hy-pothesis formulation essential for effective clinical reasoning (Dolmans et al., 2005).

10.2.2. Progressive Problem Analysis

As in clinical practice, PBL often employs progressive disclosure of case information:

Students must determine what additional information would be valuable

Hypotheses are refined based on new data, modeling clinical decision-making

The iterative nature of clinical reasoning is explicitly represented

This approach develops the flexibility in thinking required for effective diagnostic rea-soning (Hmelo Silver, 2004).

10.2.3. Integration of Basic and Clinical Sciences

PBL requires students to connect pathophysiological mechanisms with clinical manifes-tations:

Students explain clinical findings through underlying mechanisms

Basic science knowledge becomes contextualized within clinical presentations

Causal networks between pathophysiology and symptoms are constructed

This integration facilitates the development of illness scripts—organized knowledge structures that support clinical reasoning (Schmidt et al., 2011).

10.2.4. Explicit Reasoning Articulation

The collaborative nature of PBL requires verbalization of reasoning processes:

Students must articulate their thinking to group members

Reasoning flaws become visible and subject to peer critique

Multiple perspectives enrich individual cognitive models

This externalization of thought processes accelerates the development of metacognitive awareness in clinical reasoning (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006).

10.3. Evidence for Enhanced Clinical Reasoning

Research supports PBL’s effectiveness in developing clinical reasoning capabilities:

Comparative studies demonstrate that PBL students generate more diversified dif-ferential diagnoses for complex cases (Schmidt et al., 2011)

PBL graduates show enhanced diagnostic accuracy when confronted with atypical presentations (Dolmans et al., 2005)

Students from PBL curricula demonstrate superior abilities in integrating basic science knowledge in their clinical reasoning (Hmelo Silver, 2004)

PBL-trained physicians exhibit more sophisticated metacognitive monitoring during clinical problem-solving (Wood, 2003)

10.4. Optimizing Clinical Reasoning Development in PBL

Several evidence-based strategies can enhance clinical reasoning development within PBL curricula:

Structured reflection: Incorporating explicit prompts for reflection on reasoning processes

Exemplar diversity: Exposing students to varied presentations of similar condi-tions to enhance pattern recognition

Deliberate comparison: Designing cases that require discrimination between sim-ilar presentations with different underlying causes

Expert modeling: Occasional demonstration of expert reasoning processes at case conclusion

Concept mapping: Visual representation of relationships between clinical findings and potential diagnoses

These enhancements to standard PBL approaches can further optimize the develop-ment of clinical reasoning capabilities (Dolmans Schmidt, 2006).

The alignment between PBL processes and authentic clinical reasoning makes this pedagogical approach particularly valuable for developing the complex cognitive skills re-quired for diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making. By engaging students in authentic clinical problem-solving from early in their education, PBL cultivates reasoning habits and metacognitive awareness that support the development of diagnostic expertise.

11. Conclusions and Future Directions

Problem-Based Learning has evolved from an innovative experiment at a single institution to a dominant paradigm in medical education worldwide. This review has examined the theoretical foundations, implementation approaches, and empirical evidence supporting PBL as an effective methodology for developing the multifaceted competencies required for contemporary medical practice.

11.1. Key Findings

Several conclusions can be drawn from the evidence reviewed:

PBL effectively develops integrated knowledge structures that support clinical rea-soning and knowledge application, even if short-term factual recall may not surpass traditional approaches.

The methodology systematically cultivates self-directed learning competencies es-sential for maintaining professional competence in an era of rapidly evolving medical knowledge.

PBL fosters the development of collaborative and communication skills increasingly recognized as crucial for effective healthcare delivery.

Implementation challenges are significant but can be addressed through strategic approaches adapted to specific institutional contexts.

The alignment between PBL processes and authentic clinical reasoning supports the development of diagnostic expertise.

These findings validate PBL’s status as a valuable approach to medical education, particularly when implemented with fidelity to its core principles and adapted thoughtfully to specific educational contexts.

11.2. Recommendations for Practice

Based on the evidence reviewed, several recommendations can be offered for medical educators and institutions:

Strategic Integration: Rather than viewing PBL as an all-or-nothing approach, institutions should consider strategic integration of PBL elements within compre-hensive curricula that leverage diverse pedagogical methods.

Faculty Development: Robust faculty development programs are essential for successful PBL implementation, focusing on both facilitation skills and assessment approaches aligned with PBL principles.

Thoughtful Case Design: Investment in high-quality, authentic cases with ap-propriate complexity and alignment with learning objectives is critical for effective PBL implementation.

Assessment Alignment: Assessment systems must be carefully designed to eval-uate the multidimensional competencies developed through PBL, including process skills and clinical reasoning.

Technology Integration: Judicious incorporation of educational technologies can enhance PBL implementation through supporting information access, collaboration, and scalability.

These recommendations acknowledge that effective PBL implementation requires thought-ful adaptation rather than rigid adherence to a single model.

11.3. Future Research Directions

Despite extensive investigation, several areas warrant further research to optimize PBL implementation:

Long-term Outcomes: Longitudinal studies examining the impact of PBL on practice patterns, patient outcomes, and career trajectories would strengthen the evidence base for PBL effectiveness.

Implementation Science: Research on factors that influence successful PBL implementation across diverse institutional contexts would support more effective adaptation.

Cognitive Load Optimization: Investigation of approaches to managing cogni-tive load within PBL could enhance efficiency while maintaining effectiveness.

Technology-Enhanced PBL: Exploration of how emerging technologies, includ-ing simulation, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence, might enhance traditional PBL approaches.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Rigorous evaluation of the resource implications and return on investment for PBL compared to alternative approaches would inform institutional decision-making.

These research directions reflect the ongoing evolution of PBL as a responsive peda-gogical approach within changing educational and healthcare landscapes.

11.4. Concluding Perspective

Problem-Based Learning represents more than a specific methodology; it embodies a philosophical shift toward student-centered, active learning approaches in medical educa-tion. Its emphasis on authentic problem-solving, self-direction, and integrated knowledge application aligns well with the demands of contemporary healthcare, where physicians must navigate complexity, uncertainty, and continuous knowledge evolution.

While not without implementation challenges, PBL offers a powerful framework for developing the multidimensional competencies required for effective medical practice. The evidence reviewed supports its continued role as a fundamental pillar in the education of competent physicians prepared to meet the evolving challenges of healthcare delivery.

As medical education continues to evolve in response to changing healthcare needs and emerging evidence about learning, PBL is likely to remain a central approach—albeit one that will continue to be refined and integrated with complementary educational strategies. The principles underlying PBL—active construction of knowledge, contextual learning, and self-direction—represent enduring contributions to our understanding of effective pro-fessional education.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of their respective institutions in the preparation of this manuscript. Additionally, we express our gratitude to the many educators and researchers whose work has advanced our understanding of Problem-Based Learning in medical education.

References

- Barrows, H. S. (1986). A taxonomy of problem-based learning methods. Medical Educa-tion, 20(6), 481-486. [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, D. H., De Grave, W., Wolfhagen, I. H., and Van Der Vleuten, C. P. (2005). Problem-based learning: Future challenges for educational practice and research. Med-ical Education, 39(7), 732-741. [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, D. H., & Schmidt, H. G. (2006). What do we know about cognitive and moti-vational effects of small group tutorials in problem-based learning?. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 11(4), 321-336. [CrossRef]

- Hmelo Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn?. Educational Psychology Review, 16(3), 235-266. [CrossRef]

- Savin Baden, M., & Major, C. H. (2004). Foundations of problem-based learning. Open University Press.

- Schmidt, H. G., Rotgans, J. I., Yew, E. H. (2011). The process of problem-based learning: What works and why. Medical Education, 45(8), 792-806. [CrossRef]

- Wood, D. F. (2003). Problem based learning. BMJ, 326(7384), 328-330. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Educational Methodologies in Medical Education.

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Educational Methodologies in Medical Education.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).