Submitted:

10 October 2024

Posted:

11 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Materials and Methods

|

State (No. of Rivers) |

SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | TiO2 | P2O5 | SiO2/Al2O3 | Fe2O3/Al2O3 | Al2O3/TiO2 | CIA | PIA | ICV | MIA (O) | MIA (R) | IOL | |

| Kerala (21) | Range | 34.08-48.17 | 15.44-26.06 | 9.55-16.03 | 0.06-0.22 | 0.60-3.53 | 0.30-2.59 | 0.17-1.89 | 0.72-2.66 | 0.74-1.57 | 0.15-0.80 | 1.38- 2.21 |

0.37- 0.71 |

11.29- 34.19 |

76.13-94.19 | 67.23-91.28 | 0.57-1.14 | 75.61-93.55 | 50.39-67.10 | 34.69-54.21 |

| Avg., | 38.75 | 22.71 | 12.09 | 0.13 | 1.71 | 0.94 | 0.49 | 1.54 | 1.24 | 0.41 | 1.71 | 0.53 | 18.31 | 88.36 | 82.33 | 0.81 | 88.09 | 59.34 | 47.37 | |

| STD (±) | 3.96 | 2.25 | 1.94 | 0.04 | 0.75 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.10 | 4.64 | 4.25 | 5.95 | 0.16 | 4.20 | 4.94 | 4.02 | |

| Karnataka (20) | Range | 39.34-65.74 | 15.21-21.44 | 6.69-13.39 | 0.02-0.13 | 0.34-2.21 | 0.07-1.18 | 0.05-0.99 | 0.44-1.80 | 0.94-1.98 | 0.07-0.35 | 1.99- 4.32 |

0.32- 0.71 |

10.31- 19.97 |

81.23-96.24 | 72.89-94.17 | 0.50-1.02 | 81.34-96.47 | 52.86-71.74 | 26.29-44.13 |

| Avg., | 49.33 | 19.22 | 10.08 | 0.07 | 1.03 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 1.07 | 1.35 | 0.22 | 2.60 | 0.53 | 14.81 | 90.94 | 85.88 | 0.76 | 90.88 | 61.67 | 37.40 | |

| STD (±) | 5.38 | 1.64 | 1.85 | 0.03 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.10 | 2.71 | 3.49 | 4.90 | 0.14 | 3.48 | 5.17 | 3.88 | |

| Goa (11) | Range | 43.19-56.47 | 14.81-20.41 | 6.03-14.47 | 0.05-0.55 | 1.23-3.50 | 0.42-2.35 | 0.20-0.72 | 1.08-1.51 | 1.16-2.10 | 0.21-0.49 | 2.46- 3.15 |

0.31- 0.86 |

8.57- 14.90 |

80.13-90.81 | 74.00-84.87 | 0.60-1.32 | 78.79-91.41 | 47.05-67.95 | 31.34-42.56 |

| Avg., | 49.38 | 17.65 | 9.66 | 0.17 | 2.23 | 1.06 | 0.42 | 1.30 | 1.59 | 0.32 | 2.81 | 0.56 | 11.46 | 86.43 | 80.05 | 0.95 | 84.54 | 56.52 | 35.69 | |

| STD (±) | 4.23 | 1.72 | 2.64 | 0.18 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 2.12 | 3.12 | 3.49 | 0.22 | 3.84 | 6.65 | 3.26 | |

| Archean- Proterozoic Terrain (APT) | Range | 34.08-65.74 | 14.81-26.06 | 6.03-16.03 | 0.02-0.55 | 0.34-3.53 | 0.07-2.59 | 0.05-1.89 | 0.44-2.66 | 0.74-2.10 | 0.07-0.80 | 1.38-4.32 | 0.31-0.86 | 8.57-30.65 | 76.13-96.24 | 67.23-94.17 | 0.50-1.32 | 75.61-96.47 | 47.05-71.74 | 26.29-54.21 |

| Avg., | 45.07 | 20.30 | 10.80 | 0.12 | 1.56 | 0.80 | 0.41 | 1.31 | 1.36 | 0.32 | 2.29 | 0.54 | 15.76 | 88.57 | 82.75 | 0.84 | 87.83 | 59.17 | 40.15 | |

| STD (±) | 6.93 | 2.82 | 2.30 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.61 | 0.12 | 4.53 | 3.62 | 14.34 | 0.17 | 3.84 | 4.9 | 3.72 | |

| Maharashtra (21) | Range | 46.24-57.94 | 14.98-22.11 | 0.81-9.37 | 0.05-0.37 | 0.93-5.76 | 0.47-10.91 | 0.10-1.67 | 0.38-1.82 | 1.07-8.36 | 0.08-0.60 | 2.41- 3.72 |

0.04- 0.56 |

1.96- 15.77 |

55.08-92.99 | 52.15-91.00 | 0.39-1.45 | 56.03-89.80 | 44.10-85.37 | 22.98-31.62 |

| Avg., | 53.34 | 18.06 | 3.12 | 0.20 | 2.55 | 2.93 | 0.64 | 0.78 | 3.43 | 0.25 | 2.99 | 0.18 | 6.12 | 81.02 | 77.46 | 0.78 | 75.96 | 65.72 | 28.43 | |

| STD (±) | 3.46 | 2.11 | 2.45 | 0.08 | 1.20 | 2.25 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 1.49 | 0.11 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 2.67 | 8.77 | 8.73 | 0.27 | 9.41 | 10.54 | 2.60 | |

| Gujarat (17) | Range | 50.55-63.44 | 12.26-16.32 | 0.30-7.08 | 0.09-0.24 | 2.30-3.72 | 3.03-10.88 | 0.77-1.91 | 0.79-1.58 | 1.59-3.42 | 0.13-0.33 | 3.17- 4.75 |

0.02- 0.50 |

4.19- 8.81 |

46.56-77.56 | 41.06-73.78 | 0.97-1.87 | 48.67-75.85 | 37.37-57.14 | 18.73-30.73 |

| Avg., | 55.71 | 14.17 | 3.68 | 0.15 | 2.93 | 6.16 | 1.31 | 1.25 | 2.36 | 0.17 | 3.97 | 0.26 | 6.27 | 62.20 | 56.72 | 1.28 | 60.58 | 48.93 | 24.30 | |

| STD (±) | 3.36 | 1.46 | 1.62 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 1.86 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.12 | 1.35 | 7.54 | 8.09 | 0.27 | 6.24 | 6.17 | 3.12 | |

| Deccan Trap Terrain (DTT) | Range | 46.63-63.44 | 12.26-22.11 | 0.30-9.37 | 0.05-0.37 | 0.93-5.76 | 0.47-10.91 | 0.10-1.91 | 0.38-1.82 | 1.07-8.36 | 0.08-0.60 | 2.41-4.75 | 0.02-0.56 | 1.96-15.77 | 46.56-92.99 | 41.06-91.00 | 0.39-1.87 | 48.67-89.80 | 37.37-85.37 | 18.73-31.62 |

| Avg., | 54.40 | 16.32 | 3.37 | 0.17 | 2.72 | 4.37 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 2.95 | 0.22 | 3.43 | 0.22 | 6.19 | 71.61 | 67.09 | 1.03 | 68.27 | 57.32 | 26.36 | |

| STD (±) | 3.57 | 2.67 | 2.11 | 0.07 | 0.94 | 2.63 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 1.27 | 0.09 | 0.66 | 0.14 | 2.16 | 8.15 | 8.41 | 0.27 | 7.82 | 8.35 | 2.86 | |

| West Coast of India River Average Silt (WCIRAS) | Range | 34.08-65.74 | 12.26-26.06 | 0.30-16.03 | 0.34-5.76 | 0.07-10.91 | 0.05-1.91 | 0.38-2.66 | 0.74-8.36 | 0.02-0.55 | 0.07-0.80 | 1.61-4.75 |

0.02- 0.86 |

1.96-30.65 | 46.56-96.24 | 41.06-94.17 | 0.39-1.87 | 48.67-96.47 | 37.37-85.37 | 18.73-54.21 |

| Avg., |

49.30 |

18.62 | 7.66 | 2.14 | 2.58 | 0.67 | 1.17 | 2.03 | 0.14 | 0.27 |

2.81 |

0.41 |

1.96-30.65 |

81.79 |

76.86 | 0.89 | 80.24 | 59.03 | 34.63 | |

| STD (±) | 4.07 | 3.38 | 4.30 | 0.87 | 1.56 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 1.16 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 1.96-30.65 | 5.43 | 12.14 | 0.28 | 12.47 | 8.96 | 3.37 | |

| Reference Sediments | PAAS | 62.80 | 18.90 | 7.22 | 0.11 | 2.20 | 1.30 | 1.20 | 3.70 | 1.00 | 0.16 | 3.32 | 0.38 | 18.90 | 75.29 | - | - | 63.36 | 55.92 | 23.97 |

| UCC | 66.20 | 15.30 | 5.57 | 0.09 | 2.47 | 3.57 | 3.25 | 2.78 | 0.63 | 0.15 | 4.33 | 0.36 | 24.29 | 61.44 | - | - | 75.67 | 47.24 | 29.37 | |

| CIA: Chemical Index of Alteration (Nesbitt and Young 1982); PIA: Plagioclase Index of Alteration (Fedo et al. (1995, 1996); ICV: Index of Chemical Variability (Cox et al. 1995; Cullers 2000);MIA : Mafic Index of Alteration (Oxic) and MIA : Mafic Index of Alteration (Redox) (Babechuk and Fedo (O) (R) 2022); IOL: Index of Laterization (Babechuk and Fedo 2022); APT: Archean- Proterozoic Terrain (this study); DTT: Deccan Trap Terrain (this study); WCIRAC: West Coast of India River Average Clay (this study); WCIRAS: West Coast of India River Average Silt (this study); PASS: Post Archean average Australian Shale (Pourmand et al. 2012); UCC: Upper Continental Crust (Rudnick and Gao 2003). | ||||||||||||||||||||

| State (No. of Rivers) | Sc | V | Cr | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Rb | Sr | Nb | Cs | Ba | Hf | Th | U | Zr | Ta | Pb | Y | La | Ce | Yb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kerala (21) | Range | 20.635-32.939 | 111.228-247.004 | 108.934-286.565 | 18.621-41.839 | 42.601-101.548 | 29.208-111.952 | 29.812-155.052 | 24.975-37.808 | 36.921-91.318 | 45.695-160.748 | 10.997-21.144 | 2.399-6.017 | 169.206-805.442 | 3.647-6.870 | 7.098-24.337 | 1.542-5.112 | 106.617-220.885 | 0.738-1.285 | 12.152-55.830 | 16.558-32.174 | 29.485-95.765 | 63.296-179.624 | 1.864-3.336 |

| Avg., | 26.541 | 175.490 | 158.778 | 29.480 | 63.448 | 73.452 | 58.064 | 33.533 | 61.766 | 79.312 | 14.930 | 3.569 | 381.114 | 4.769 | 11.915 | 2.569 | 147.032 | 0.969 | 31.707 | 25.822 | 55.635 | 109.026 | 2.723 | |

| STD ± | 3.292 | 39.857 | 52.253 | 7.767 | 16.006 | 19.719 | 30.319 | 3.588 | 15.075 | 29.618 | 2.811 | 0.825 | 199.435 | 0.851 | 3.966 | 1.004 | 27.292 | 0.144 | 11.619 | 3.762 | 19.957 | 36.471 | 0.380 | |

| Karnataka (20) | Range | 14.307-36.603 | 136.105-347.618 | 82.778-897.427 | 11.395-55.126 | 46.310-129.463 | 76.344-231.775 | 53.654-195.438 | 24.545-39.110 | 31.908-88.767 | 29.474-71.719 | 11.333-26.539 | 3.222-6.995 | 104.126-288.198 | 4.027-10.586 | 7.939-25.704 | 1.629-6.168 | 136.561-393.665 | 1.040-2.388 | 17.312-51.190 | 8.572-27.410 | 8.035-42.580 | 29.500-86.723 | 1.238-2.966 |

| Avg., | 22.491 | 228.554 | 203.823 | 24.735 | 72.184 | 133.002 | 85.446 | 32.481 | 61.710 | 49.209 | 16.625 | 4.984 | 177.673 | 5.626 | 13.924 | 3.917 | 198.999 | 1.550 | 31.859 | 16.313 | 24.512 | 66.322 | 1.876 | |

| SD (±) | 7.090 | 64.939 | 168.245 | 11.363 | 18.098 | 48.957 | 32.997 | 4.005 | 17.035 | 10.621 | 3.600 | 1.285 | 49.698 | 1.665 | 4.884 | 1.133 | 66.097 | 0.373 | 9.974 | 4.828 | 9.141 | 15.286 | 0.479 | |

| Goa (11) | Range | 16.044-29.542 | 178.553-273.344 | 146.390-237.876 | 17.483-39.659 | 57.233-74.550 | 91.655-194.898 | 63.406-128.709 | 23.872-31.193 | 53.522-87.735 | 53.389-80.888 | 12.603-20.291 | 4.424-7.334 | 140.514-255.500 | 4.939-7.866 | 9.140-15.503 | 3.513-7.619 | 175.519-282.745 | 1.070-1.853 | 21.798-88.871 | 16.050-28.522 | 17.450-37.343 | 52.803-87.536 | 1.892-2.748 |

| Avg., | 24.123 | 222.571 | 187.975 | 30.539 | 63.886 | 121.412 | 84.618 | 27.003 | 74.508 | 70.698 | 15.604 | 5.931 | 185.070 | 6.142 | 12.544 | 4.939 | 220.424 | 1.425 | 34.096 | 22.733 | 28.772 | 71.293 | 2.333 | |

| SD (±) | 3.627 | 31.299 | 23.421 | 7.853 | 5.550 | 33.427 | 18.874 | 2.266 | 9.906 | 10.212 | 2.860 | 0.908 | 36.729 | 0.987 | 1.887 | 1.180 | 37.971 | 0.241 | 18.693 | 4.874 | 6.236 | 10.335 | 0.331 | |

| Archean- Proterozoic Terrain (APT) | Range | 14.307-36.603 | 111.228-347.618 | 82.778-897.427 | 11.395-55.126 | 42.601-129.463 | 29.208-231.775 | 29.812-195.438 | 23.872-39.110 | 31.908-91.318 | 29.474-160.748 | 10.997-26.539 | 2.399-7.334 | 104.126-805.442 | 3.647-10.586 | 7.098-25.704 | 1.542-7.619 | 106.617-393.665 | 0.738-2.388 | 12.152-88.871 | 8.572-32.174 | 8.035-95.765 | 29.500-179.624 | 1.238-3.336 |

| Avg., | 24.472 | 205.859 | 182.279 | 27.879 | 66.901 | 106.501 | 74.213 | 31.747 | 64.440 | 65.912 | 15.725 | 4.613 | 261.397 | 5.389 | 12.821 | 3.589 | 182.544 | 1.289 | 32.271 | 21.511 | 37.982 | 84.620 | 2.315 | |

| SD (±) | 5.374 | 55.028 | 110.183 | 9.503 | 15.695 | 45.140 | 31.878 | 4.291 | 15.627 | 24.388 | 3.180 | 1.386 | 163.369 | 1.345 | 4.072 | 1.418 | 56.012 | 0.380 | 12.627 | 6.121 | 20.315 | 32.318 | 0.555 | |

| Maharashtra (21) | Range | 26.371-58.580 | 194.681-465.372 | 86.186-267.990 | 27.035-70.839 | 53.673-104.417 | 133.713-275.273 | 64.061-192.930 | 23.349-45.456 | 26.920-92.183 | 42.265-217.870 | 9.002-18.219 | 1.670-7.822 | 128.836-362.785 | 4.319-9.142 | 5.400-18.302 | 1.000-5.902 | 158.734-321.440 | 0.904-1.712 | 8.604-39.252 | 20.649-54.546 | 20.087-46.223 | 45.041-127.803 | 2.053-3.924 |

| Avg., | 40.147 | 343.606 | 159.771 | 48.828 | 67.892 | 204.181 | 102.430 | 30.096 | 49.719 | 75.981 | 12.767 | 4.012 | 193.895 | 6.797 | 8.651 | 2.692 | 248.783 | 1.250 | 23.460 | 34.763 | 28.195 | 68.631 | 2.804 | |

| SD (±) | 8.210 | 75.765 | 46.991 | 12.268 | 12.018 | 47.942 | 32.047 | 4.772 | 19.262 | 38.998 | 2.940 | 1.816 | 59.513 | 1.230 | 3.331 | 1.377 | 45.455 | 0.249 | 8.440 | 8.949 | 6.895 | 19.883 | 0.471 | |

| Gujarat (17) | Range | 27.045-43.052 | 164.990-424.366 | 105.933-968.394 | 28.294-91.345 | 42.412-536.775 | 110.882-391.214 | 52.217-697.892 | 23.007-30.963 | 41.537-101.176 | 83.443-374.887 | 11.194-15.159 | 3.449-8.564 | 163.612-382.990 | 4.954-7.044 | 6.817-14.281 | 1.141-2.444 | 182.271-270.611 | 0.966-1.577 | 11.173-77.110 | 26.256-32.431 | 20.980-35.591 | 47.115-71.305 | 2.012-2.388 |

| Avg., | 36.241 | 264.236 | 172.995 | 40.262 | 75.466 | 165.342 | 117.304 | 25.963 | 65.382 | 129.261 | 13.054 | 5.016 | 225.596 | 5.902 | 8.731 | 1.583 | 221.234 | 1.225 | 21.669 | 29.637 | 26.779 | 57.510 | 2.235 | |

| SD (±) | 3.927 | 73.682 | 205.485 | 13.683 | 118.933 | 66.201 | 151.432 | 1.938 | 15.480 | 65.978 | 1.093 | 1.201 | 56.848 | 0.577 | 1.768 | 0.329 | 22.506 | 0.156 | 15.569 | 2.189 | 3.702 | 5.571 | 0.140 | |

| Deccan Trap Terrain (DTT) | Range | 26.371-58.580 | 164.990-465.372 | 86.186-968.394 | 27.035-91.345 | 42.412-536.775 | 110.882-391.214 | 52.217-697.892 | 23.007-45.456 | 26.920-101.176 | 42.265-374.887 | 9.002-18.219 | 1.670-8.564 | 128.836-382.990 | 4.319-9.142 | 5.400-18.302 | 1.000-5.902 | 158.734-321.440 | 0.904-1.712 | 8.604-77.110 | 20.649-54.546 | 20.087-46.223 | 45.041-127.803 | 2.012-3.924 |

| Avg., | 38.400 | 308.098 | 165.687 | 44.996 | 71.280 | 186.805 | 109.084 | 28.247 | 56.726 | 99.817 | 12.895 | 4.461 | 208.077 | 6.397 | 8.687 | 2.196 | 236.459 | 1.239 | 22.659 | 32.470 | 27.561 | 63.656 | 2.549 | |

| SD (±) | 6.854 | 83.965 | 139.632 | 13.451 | 78.800 | 59.335 | 102.605 | 4.274 | 19.144 | 58.526 | 2.283 | 1.632 | 59.726 | 1.079 | 2.711 | 1.177 | 39.097 | 0.210 | 12.006 | 7.214 | 5.669 | 16.079 | 0.459 | |

| West Coast of India River Average Clay (WCIRAC) | Range | 14.307-58.580 | 111.228-465.372 | 82.778-968.394 | 11.395-91.345 | 42.412-536.775 | 29.208-391.214 | 29.812-697.892 | 23.007-45.456 | 26.920-101.176 | 29.474-374.887 | 9.002-26.539 | 1.670-8.564 | 104.126-805.442 | 3.647-10.586 | 5.400-25.704 | 1.000-7.619 | 106.617-393.665 | 0.738-2.388 | 8.604-88.871 | 8.572-54.546 | 8.035-95.765 | 29.500-179.624 | 1.238-3.924 |

| Avg., | 30.353 | 249.027 | 175.274 | 35.106 | 68.750 | 140.407 | 88.936 | 30.269 | 61.183 | 80.227 | 14.530 | 4.549 | 238.884 | 5.814 | 11.076 | 3.001 | 205.308 | 1.268 | 28.212 | 26.138 | 33.582 | 75.768 | 2.414 | |

| SD (±) | 9.162 | 85.116 | 123.005 | 14.116 | 52.224 | 64.978 | 72.519 | 4.601 | 17.521 | 45.259 | 3.152 | 1.488 | 132.205 | 1.331 | 4.096 | 1.485 | 56.128 | 0.319 | 13.194 | 8.528 | 16.633 | 28.538 | 0.527 | |

| Reference Sediments | PAAS | 15.890 | 150.000 | 110.000 | 23.000 | 55.000 | 50.000 | 85.000 | 20.000 | 160.000 | 200.000 | 19.000 | 15.000 | 650.000 | 5.000 | 14.600 | 3.100 | 210.000 | 1.500 | 20.000 | 27.310 | 44.560 | 88.250 | 2.040 |

| UCC | 14.000 | 97.000 | 92.300 | 17.300 | 47.300 | 27.700 | 67.000 | 17.500 | 82.000 | 320.000 | 11.800 | 4.100 | 624.000 | 5.260 | 10.100 | 2.630 | 193.000 | 0.880 | 17.000 | 21.000 | 31.400 | 63.400 | 3.012 |

| State (No. of Rivers) | ∑TE | Th/Sc | Zr/Sc | Cr/V | Y/Ni | Co/Th | La/Sc | Zr/Co | La/Th | Th/Yb | Th/U | Rb/Sr | K2O/Rb | Cr/Th | Cr/Ni | V/Th | |

| Kerala (21) | Range | 991.581-1802.551 | 0.238-0.944 | 3.854-9.731 | 0.694-1.382 | 0.214-0.669 | 1.057-5.895 | 0.955-3.918 | 2.686-9.095 | 3.026-10.488 | 2.210-8.020 | 2.444-12.313 | 0.368-1.586 | 0.061-0.011 | 5.747-36.894 | 1.985-3.114 | 6.537-31.275 |

| Avg., | 1358.438 | 0.458 | 5.622 | 0.905 | 0.429 | 2.763 | 2.141 | 5.357 | 4.813 | 4.453 | 5.242 | 0.868 | 0.021 | 14.947 | 2.485 | 16.304 | |

| STD ± | 212.296 | 0.167 | 1.299 | 0.183 | 0.116 | 1.285 | 0.833 | 1.798 | 1.704 | 1.512 | 2.614 | 0.347 | 0.013 | 7.901 | 0.330 | 6.827 | |

| Karnataka (20) | Range | 1097.931-2027.128 | 0.222-1.473 | 4.235-1.288 | 0.426-3.350 | 0.099-0.350 | 0.443-4.207 | 0.281-2.388 | 3.576-23.381 | 0.751-2.515 | 3.562-20.755 | 1.937-7.176 | 0.725-2.038 | 0.015-0.022 | 3.220-110.234 | 1.787-6.932 | 5.747-33.781 |

| Avg., | 1368.793 | 0.694 | 9.327 | 0.907 | 0.234 | 1.967 | 1.230 | 9.450 | 1.773 | 8.061 | 3.685 | 1.281 | 0.018 | 17.981 | 2.633 | 18.567 | |

| STD ± | 218.062 | 0.345 | 3.215 | 0.619 | 0.071 | 1.021 | 0.633 | 5.100 | 0.370 | 4.177 | 1.178 | 0.373 | 0 | 22.360 | 1.070 | 8.419 | |

| Goa (11) | Range | 1269.836-1611.232 | 0.343-0.849 | 6.544-17.623 | 0.708-1.075 | 0.222-0.455 | 1.145-4.033 | 0.747-1.640 | 4.426-15.098 | 1.281-2.890 | 4.400-7.200 | 2.035-3.118 | 0.892-1.267 | 0.016-0.27 | 9.588-23.105 | 2.558-4.004 | 13.407-29.906 |

| Avg., | 1393.509 | 0.538 | 9.557 | 0.856 | 0.360 | 2.534 | 1.198 | 8.034 | 2.316 | 5.450 | 2.599 | 1.063 | 0.020 | 15.432 | 2.954 | 18.200 | |

| SD (±) | 92.542 | 0.150 | 3.345 | 0.138 | 0.087 | 0.899 | 0.224 | 3.709 | 0.483 | 0.988 | 0.366 | 0.129 | 0 | 3.643 | 0.405 | 4.533 | |

| Archean- Proterozoic Terrain (APT) | Range | 991.581-2027.128 | 0.222-1.473 | 3.854-17.623 | 0.426-3.350 | 0.099-0.669 | 0.443-5.895 | 0.281-3.918 | 2.686-23.381 | 0.751-10.488 | 2.210-20.755 | 1.937-12.313 | 0.368-2.038 | 0.015-0.27 | 3.220-110.234 | 1.787-6.932 | 5.747-33.781 |

| Avg., | 1369.840 | 0.566 | 7.879 | 0.896 | 0.339 | 2.409 | 1.591 | 7.498 | 3.116 | 6.052 | 4.084 | 1.068 | 0.02 | 16.217 | 2.641 | 17.576 | |

| SD (±) | 192.985 | 0.267 | 3.199 | 0.400 | 0.128 | 1.152 | 0.800 | 4.135 | 1.807 | 3.210 | 2.077 | 0.370 | 0 | 14.675 | 0.730 | 7.060 | |

| Maharashtra (21) | Range | 1360.433-1980.545 | 0.112-0.675 | 4.300-10.757 | 0.234-0.733 | 0.292-0.777 | 1.886-10.900 | 0.451-1.706 | 3.204-11.738 | 2.008-4.673 | 1.656-7.349 | 1.882-5.399 | 0.283-2.026 | 0.011-0.026 | 9.134-47.415 | 1.399-3.610 | 15.624-72.531 |

| Avg., | 1624.956 | 0.239 | 6.370 | 0.487 | 0.520 | 6.413 | 0.745 | 5.472 | 3.477 | 3.232 | 3.610 | 0.768 | 0.019 | 20.820 | 2.347 | 44.275 | |

| SD (±) | 164.494 | 0.153 | 1.521 | 0.164 | 0.130 | 2.809 | 0.312 | 2.127 | 0.873 | 1.567 | 1.054 | 0.481 | 0 | 10.617 | 0.513 | 16.835 | |

| Gujarat (17) | Range | 1248.288-3733.648 | 0.167-0.528 | 5.301-6.740 | 0.289-3.060 | 0.059-0.721 | 1.981-12.389 | 0.522-1.316 | 2.062-7.237 | 2.492-3.374 | 2.997-6.809 | 4.332-6.287 | 0.192-0.766 | 0.015-0.02 | 10.308-131.344 | 1.804-3.170 | 11.553-55.574 |

| Avg., | 1596.461 | 0.248 | 6.124 | 0.652 | 0.603 | 4.852 | 0.756 | 5.817 | 3.099 | 3.931 | 5.546 | 0.550 | 0.02 | 21.333 | 2.592 | 32.199 | |

| SD (±) | 565.617 | 0.083 | 0.423 | 0.634 | 0.159 | 2.166 | 0.187 | 1.099 | 0.234 | 0.918 | 0.493 | 0.139 | 0 | 28.535 | 0.285 | 13.035 | |

| Deccan Trap Terrain (DTT) | Range | 1248.288-3733.648 | 0.112-0.675 | 4.300-10.757 | 0.234-3.060 | 0.059-0.777 | 1.886-12.389 | 0.451-1.706 | 2.062-11.738 | 2.008-4.673 | 1.656-7.349 | 1.882-6.287 | 0.192-2.026 | 0.011-0.026 | 9.134-131.344 | 1.399-3.610 | 11.553-72.531 |

| Avg., | 1612.208 | 0.243 | 6.260 | 0.561 | 0.557 | 5.715 | 0.750 | 5.626 | 3.308 | 3.545 | 4.476 | 0.670 | 0.02 | 21.050 | 2.456 | 38.873 | |

| SD (±) | 391.379 | 0.125 | 1.159 | 0.442 | 0.148 | 2.629 | 0.260 | 1.732 | 0.687 | 1.348 | 1.287 | 0.382 | 0 | 20.325 | 0.439 | 16.239 | |

| West Coast of India River Average Clay (WCIRAC) | Range | 991.581-3734.378 | 0.112-1.473 | 3.854-17.623 | 0.234-3.350 | 0.059-0.777 | 0.443-12.389 | 0.281-3.918 | 2.062-23.381 | 0.751-10.488 | 1.656-20.755 | 1.882-12.313 | 0.192-2.038 | 0.011-0.061 | 3.220-131.344 | 1.399-6.932 | 5.747-72.531 |

| Avg., | 1473.054 | 0.429 | 7.196 | 0.754 | 0.431 | 3.805 | 1.236 | 6.707 | 3.197 | 4.993 | 4.249 | 0.900 | 0.019 | 18.257 | 2.563 | 26.568 | |

| SD (±) | 315.457 | 0.270 | 2.659 | 0.448 | 0.174 | 2.516 | 0.755 | 3.451 | 1.441 | 2.865 | 1.788 | 0.422 | 0.007 | 17.347 | 0.627 | 15.814 | |

| Reference Sediments | PAAS | 1807.090 | 0.919 | 13.216 | 0.733 | 0.497 | 1.575 | 2.804 | 9.130 | 3.052 | 7.157 | 4.710 | 0.800 | - | 7.534 | 2.000 | 10.274 |

| UCC | 1650.870 | 0.721 | 13.786 | 0.952 | 0.444 | 1.713 | 2.243 | 11.156 | 3.109 | 3.353 | 3.840 | 0.256 | - | 9.139 | 1.951 | 9.604 | |

| APT: Archean- Proterozoic Terrain (this study); DTT: Deccan Trap Terrain (this study); WCIRAC: West Coast of India River Average Clay (this study); PASS: Post Archean average Australian Shale (Pourmand et al. 2012); UCC: Upper Continental Crust (Rudnick and Gao 2003). | |||||||||||||||||

| State (No. of Rivers) | Sc | V | Cr | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Rb | Sr | Nb | Cs | Ba | Hf | Th | U | Zr | Ta | Pb | Y | La | Ce | Yb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kerala (21) | Range | 14.854-29.272 | 97.664-254.562 | 118.321-350.871 | 15.536-43.836 | 35.917-90.855 | 31.873-94.864 | 57.813-262.672 | 18.208-47.222 | 26.992-90.741 | 61.447-337.381 | 11.153-34.864 | 1.098-2.939 | 186.306-1503.009 | 5.498-65.310 | 6.937-116.474 | 1.260-14.628 | 188.075-2435.706 | 0.602-2.586 | 19.125-87.628 | 19.013-38.583 | 44.164-232.437 | 88.862-521.220 | 2.077-4.319 |

| Avg., | 24.274 | 181.089 | 174.381 | 29.602 | 56.458 | 68.216 | 148.772 | 33.527 | 59.268 | 155.883 | 20.47 | 2.197 | 642.236 | 18.707 | 30.731 | 3.924 | 646.91 | 1.278 | 41.001 | 30.508 | 105.36 | 201.265 | 3.102 | |

| STD ± | 3.966 | 45.163 | 76.903 | 7.459 | 15.724 | 17.486 | 67.617 | 6.186 | 20.956 | 79.156 | 6.357 | 0.491 | 401.360 | 15.033 | 27.443 | 3.266 | 538.363 | 0.515 | 18.694 | 5.379 | 56.695 | 111.539 | 0.542 | |

| Karnataka (20) | Range | 11.307-39.132 | 104.966-536.010 | 80.641-2350.397 | 10.733-35.554 | 35.120-146.151 | 50.123-185.463 | 44.007-98.212 | 11.628-39.139 | 15.114-79.790 | 36.624-101.549 | 10.205-23.313 | 1.663-4.702 | 98.824-290.563 | 5.396-27.486 | 6.273-28.434 | 1.958-7.147 | 194.577-1237.728 | 1.149-2.318 | 12.945-42.775 | 13.629-33.747 | 15.873-72.912 | 32.635-132.219 | 1.500-3.904 |

| Avg., | 22.533 | 228.920 | 296.124 | 21.222 | 63.728 | 106.649 | 67.097 | 29.130 | 40.539 | 61.829 | 16.905 | 2.966 | 194.489 | 10.917 | 14.313 | 4.144 | 426.758 | 1.724 | 25.186 | 21.573 | 32.060 | 68.186 | 2.400 | |

| SD (±) | 8.351 | 101.912 | 489.514 | 6.118 | 23.302 | 37.276 | 15.695 | 6.645 | 17.396 | 18.348 | 3.206 | 0.987 | 49.969 | 4.850 | 5.978 | 1.431 | 234.761 | 0.297 | 7.821 | 5.284 | 13.155 | 23.493 | 0.598 | |

| Goa (11) | Range | 18.965-28.718 | 183.738-348.378 | 185.497-245.622 | 16.628-39.026 | 44.343-68.937 | 85.387-166.157 | 51.774-73.844 | 16.935-26.490 | 28.959-58.617 | 52.106-107.487 | 13.638-25.627 | 2.449-5.297 | 102.865-274.009 | 6.269-13.274 | 4.339-16.796 | 4.006-7.936 | 229.788-502.269 | 1.355-4.114 | 19.446-57.531 | 18.004-31.954 | 16.758-39.641 | 31.783-89.493 | 2.109-3.339 |

| Avg., | 22.988 | 242.942 | 211.087 | 28.098 | 58.584 | 108.900 | 63.520 | 22.547 | 47.641 | 84.841 | 17.556 | 3.851 | 203.644 | 8.724 | 10.843 | 5.304 | 326.408 | 2.059 | 29.866 | 27.507 | 28.408 | 61.807 | 2.767 | |

| SD (±) | 2.904 | 49.259 | 18.595 | 7.025 | 6.884 | 28.239 | 7.531 | 2.669 | 9.228 | 17.140 | 3.831 | 0.982 | 50.619 | 2.255 | 3.268 | 1.273 | 88.031 | 0.811 | 11.116 | 4.796 | 6.400 | 16.244 | 0.343 | |

| Archean- Proterozoic Terrain (APT) | Range | 11.307-39.132 | 97.664-536.010 | 80.641-2350.397 | 10.733-43.836 | 35.120-146.151 | 31.873-185.463 | 44.007-262.672 | 11.628-47.222 | 15.114-90.741 | 36.624-337.381 | 10.205-34.864 | 1.098-5.297 | 98.824-1503.009 | 5.396-65.310 | 4.339-116.474 | 1.260-14.628 | 188.075-2435.706 | 0.602-4.114 | 12.945-87.628 | 13.629-38.583 | 15.873-232.437 | 31.783-521.220 | 1.500-4.319 |

| Avg., | 23.333 | 212.570 | 228.970 | 26.061 | 59.704 | 91.605 | 99.325 | 29.513 | 49.605 | 104.681 | 18.483 | 2.843 | 377.247 | 13.599 | 20.210 | 4.301 | 494.438 | 1.615 | 32.563 | 26.437 | 60.889 | 120.580 | 2.761 | |

| SD (±) | 5.869 | 76.530 | 307.772 | 7.790 | 17.875 | 34.241 | 59.887 | 7.072 | 19.318 | 67.266 | 5.034 | 1.022 | 336.330 | 10.820 | 19.720 | 2.356 | 391.371 | 0.600 | 15.372 | 6.528 | 51.970 | 98.176 | 0.609 | |

| Maharashtra (21) | Range | 18.191-54.444 | 179.812-1308.249 | 124.634-576.092 | 25.650-82.147 | 42.067-103.186 | 84.521-424.443 | 46.005-156.513 | 19.139-39.997 | 12.762-60.436 | 50.559-380.447 | 11.850-68.140 | 0.533-5.174 | 83.550-340.665 | 5.153-21.472 | 2.628-15.640 | 0.831-5.563 | 195.087-1119.754 | 0.900-7.484 | 7.031-38.443 | 21.641-40.056 | 12.698-40.812 | 29.291-98.563 | 2.264-3.656 |

| Avg., | 37.241 | 599.333 | 219.288 | 54.569 | 65.729 | 229.672 | 88.680 | 27.206 | 28.016 | 114.670 | 23.684 | 1.961 | 176.599 | 9.627 | 7.461 | 2.472 | 397.791 | 2.384 | 18.591 | 31.774 | 25.036 | 56.908 | 2.984 | |

| SD (±) | 10.175 | 276.646 | 125.908 | 13.816 | 11.951 | 91.615 | 30.578 | 6.011 | 13.303 | 68.844 | 12.209 | 1.222 | 70.630 | 3.974 | 3.612 | 1.421 | 222.874 | 1.410 | 8.286 | 4.977 | 6.928 | 17.660 | 0.464 | |

| Gujarat (17) | Range | 15.154-28.242 | 165.008-403.659 | 77.848-732.654 | 21.726-66.599 | 31.267-440.134 | 81.248-264.516 | 37.103-387.413 | 15.974-21.982 | 30.362-67.086 | 127.084-340.740 | 13.123-23.777 | 1.274-4.381 | 166.051-323.900 | 4.848-9.071 | 6.667-24.500 | 1.283-3.241 | 179.656-353.630 | 0.853-2.127 | 10.548-51.997 | 26.210-38.237 | 22.815-53.570 | 47.952-103.572 | 2.299-3.514 |

| Avg., | 20.393 | 280.239 | 153.228 | 34.949 | 62.746 | 130.616 | 72.733 | 18.324 | 45.902 | 189.427 | 18.446 | 2.602 | 238.464 | 6.713 | 11.423 | 1.965 | 250.858 | 1.559 | 17.292 | 31.146 | 32.941 | 67.287 | 2.821 | |

| SD (±) | 3.541 | 73.025 | 153.310 | 9.933 | 97.386 | 40.970 | 82.149 | 2.026 | 11.312 | 52.791 | 3.085 | 0.825 | 39.802 | 1.118 | 4.358 | 0.547 | 45.837 | 0.329 | 9.767 | 3.190 | 7.955 | 14.942 | 0.300 | |

| Deccan Trap Terrain (DTT) | Range | 15.154-54.444 | 165.008-1308.249 | 77.848-732.654 | 21.726-82.147 | 31.267-440.134 | 81.248-424.443 | 37.103-387.413 | 15.974-39.997 | 12.762-67.086 | 50.559-380.447 | 11.850-68.140 | 0.533-5.174 | 83.550-340.665 | 4.848-21.472 | 2.628-24.500 | 0.831-5.563 | 179.656-1119.754 | 0.853-7.484 | 7.031-51.997 | 21.641-40.056 | 12.698-53.570 | 29.291-103.572 | 2.264-3.656 |

| Avg., | 29.704 | 456.580 | 189.735 | 45.792 | 64.394 | 185.357 | 81.546 | 23.233 | 36.018 | 148.114 | 21.341 | 2.248 | 204.275 | 8.324 | 9.234 | 2.245 | 332.058 | 2.015 | 18.010 | 31.493 | 28.572 | 61.551 | 2.911 | |

| SD (±) | 11.552 | 263.683 | 140.858 | 15.607 | 64.658 | 88.058 | 59.061 | 6.430 | 15.239 | 72.014 | 9.574 | 1.098 | 65.980 | 3.352 | 4.388 | 1.134 | 182.320 | 1.137 | 8.876 | 4.230 | 8.317 | 17.102 | 0.403 | |

| West Coast of India River Average Silt (WCIRAS) | Range | 11.307-54.444 | 97.664-1308.249 | 77.848-2350.397 | 10.733-82.147 | 31.267-440.134 | 31.873-424.443 | 37.103-387.413 | 11.628-47.222 | 12.762-90.741 | 36.624-380.447 | 10.205-68.140 | 0.533-5.297 | 83.550-1503.009 | 4.848-65.310 | 2.628-116.474 | 0.931-14.628 | 179.656-1435.706 | 0.602-7.484 | 7.031-87.628 | 13.629-40.056 | 12.698-232.437 | 29.291-521.220 | 1.500-4.319 |

| Avg., | 26.023 | 315.597 | 212.404 | 34.392 | 61.684 | 131.189 | 91.818 | 26.862 | 43.868 | 123.019 | 19.689 | 2.591 | 304.215 | 11.372 | 15.575 | 3.433 | 425.877 | 1.784 | 26.418 | 28.572 | 47.245 | 95.657 | 2.824 | |

| SD (±) | 9.232 | 216.679 | 250.815 | 15.234 | 43.892 | 77.870 | 59.861 | 7.455 | 18.866 | 72.209 | 7.392 | 1.089 | 272.050 | 8.867 | 16.142 | 2.181 | 328.779 | 0.885 | 14.846 | 6.177 | 42.826 | 80.649 | 0.534 | |

| Reference Sediments | PAAS | 15.890 | 150.000 | 110.000 | 23.000 | 55.000 | 50.000 | 85.000 | 20.000 | 160.000 | 200.000 | 19.000 | 15.000 | 650.000 | 5.000 | 14.600 | 3.100 | 210.000 | 1.500 | 20.000 | 27.310 | 44.560 | 88.250 | 2.040 |

| UCC | 14.000 | 97.000 | 92.300 | 17.300 | 47.300 | 27.700 | 67.000 | 17.500 | 82.000 | 320.000 | 11.800 | 4.100 | 624.000 | 5.260 | 10.100 | 2.630 | 193.000 | 0.880 | 17.000 | 21.000 | 31.400 | 63.400 | 3.012 | |

| APT: Archean- Proterozoic Terrain (this study); DTT: Deccan Trap Terrain (this study); WCIRAS: West Coast of India River Average Silt (this study); PASS: Post Archean average Australian Shale (Pourmand et al. 2012); UCC: Upper Continental Crust (Rudnick and Gao 2003). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| State (No. of Rivers) | ∑TE | Th/Sc | Zr/Sc | Cr/V | Y/Ni | Co/Th | La/Sc | Zr/Co | La/Th | Th/Yb | Th/U | Rb/Sr | K2O/Rb | Cr/Th | Cr/Ni | V/Th | |

| Kerala (21) | Range | 1395.114-3848.586 | 0.237-5.317 | 8.226-111.194 | 0.716-1.486 | 0.273-0.929 | 0.201-6.296 | 1.509-10.611 | 5.993-103.999 | 1.999-6.759 | 1.807-31.859 | 2.761-18.264 | 0.188-1.357 | 0.017-0.037 | 1.016-46.171 | 2.037-4.897 | 1.083-36.290 |

| Avg., | 2338.935 | 1.266 | 26.650 | 0.963 | 0.540 | 0.963 | 4.340 | 21.853 | 3.428 | 9.907 | 7.830 | 0.380 | 0.027 | 5.674 | 3.089 | 5.893 | |

| STD ± | 601.675 | 1.313 | 26.082 | 0.228 | 0.182 | 1.655 | 2.666 | 27.469 | 1.562 | 7.533 | 4.794 | 0.312 | 0.000 | 11.988 | 0.687 | 9.802 | |

| Karnataka (20) | Range | 1148.902-3826.032 | 0.245-1.640 | 5.677-71.398 | 0.340-6.734 | 0.183-0.637 | 0.435-4.673 | 0.433-4.206 | 5.473-79.219 | 1.158-3.188 | 2.613-16.469 | 1.901-7.526 | 0.327-1.323 | 0.021-0.046 | 3.265-236.694 | 1.684-16.082 | 5.939-39.056 |

| Avg., | 1635.173 | 0.726 | 21.896 | 1.201 | 0.360 | 1.810 | 1.644 | 22.342 | 2.320 | 6.513 | 3.596 | 0.670 | 0.028 | 25.725 | 3.768 | 18.940 | |

| STD ± | 600.637 | 0.406 | 15.322 | 1.344 | 0.109 | 1.069 | 0.897 | 16.141 | 0.538 | 3.770 | 1.456 | 0.265 | 0.000 | 50.132 | 3.013 | 11.365 | |

| Goa (11) | Range | 1319.378-1753.873 | 0.205-0.676 | 9.674-21.269 | 0.599-1.114 | 0.299-0.594 | 1.260-8.085 | 0.792-1.787 | 6.925-23.738 | 1.945-3.862 | 1.855-5.206 | 1.043-3.160 | 0.398-0.706 | 0.021-0.037 | 12.991-53.113 | 3.045-4.921 | 15.717-62.361 |

| Avg., | 1499.403 | 0.477 | 14.446 | 0.895 | 0.476 | 3.041 | 1.238 | 12.713 | 2.742 | 3.901 | 2.063 | 0.568 | 0.028 | 22.019 | 3.660 | 25.559 | |

| SD (±) | 144.137 | 0.151 | 4.449 | 0.160 | 0.097 | 1.925 | 0.260 | 5.906 | 0.597 | 1.031 | 0.546 | 0.087 | 0.000 | 10.976 | 0.640 | 14.060 | |

| Archean- Proterozoic Terrain (APT) | Range | 1148.902-3848.586 | 0.205-5.317 | 5.677-111.194 | 0.340-6.734 | 0.183-0.929 | 0.201-8.085 | 0.433-10.611 | 5.473-103.999 | 1.158-6.759 | 1.807-31.859 | 1.043-18.264 | 0.188-1.357 | 0.017-0.046 | 1.016-236.694 | 1.684-16.082 | 1.083-62.361 |

| Avg., | 1890.664 | 0.930 | 22.863 | 1.034 | 0.473 | 2.101 | 2.728 | 21.722 | 3.243 | 7.172 | 5.217 | 0.569 | 0.027 | 19.265 | 3.455 | 17.318 | |

| SD (±) | 649.463 | 0.938 | 19.633 | 0.846 | 0.170 | 1.572 | 2.322 | 20.603 | 1.435 | 5.700 | 4.152 | 0.271 | 0.000 | 32.527 | 1.940 | 12.425 | |

| Maharashtra (21) | Range | 1483.292-3738.619 | 0.065-0.660 | 5.900-28.979 | 0.132-1.228 | 0.254-0.588 | 2.280-24.939 | 0.316-1.723 | 3.265-18.511 | 2.359-5.671 | 1.007-4.969 | 1.627-6.194 | 0.066-0.950 | 0.020-0.043 | 10.223-96.157 | 2.045-9.173 | 15.985-253.897 |

| Avg., | 2104.976 | 0.230 | 11.317 | 0.460 | 0.492 | 9.624 | 0.750 | 7.822 | 3.726 | 2.526 | 3.398 | 0.313 | 0.029 | 35.782 | 3.299 | 105.718 | |

| SD (±) | 483.883 | 0.164 | 6.685 | 0.345 | 0.077 | 5.865 | 0.375 | 4.775 | 0.951 | 1.199 | 1.326 | 0.242 | 0.000 | 23.824 | 1.681 | 75.202 | |

| Gujarat (17) | Range | 1081.086-2897.201 | 0.304-1.447 | 7.658-20.749 | 0.300-2.770 | 0.068-1.117 | 0.887-6.919 | 1.008-3.164 | 3.034-12.901 | 2.187-3.459 | 2.776-7.645 | 4.907-7.705 | 0.135-0.456 | 0.019-0.034 | 4.544-76.118 | 1.665-5.744 | 6.735-48.798 |

| Avg., | 1557.880 | 0.589 | 12.693 | 0.563 | 0.767 | 3.452 | 1.680 | 7.641 | 2.991 | 3.990 | 5.722 | 0.255 | 0.028 | 14.745 | 2.913 | 27.158 | |

| SD (±) | 381.926 | 0.291 | 3.432 | 0.576 | 0.224 | 1.448 | 0.582 | 2.327 | 0.329 | 1.205 | 0.708 | 0.082 | 0.000 | 16.133 | 0.859 | 10.031 | |

| Deccan Trap Terrain (DTT) | Range | 1081.086-3738.619 | 0.065-1.447 | 5.900-28.979 | 0.132-2.770 | 0.068-1.117 | 0.887-24.939 | 0.316-3.164 | 3.034-18.511 | 2.187-5.671 | 1.007-7.645 | 1.627-7.705 | 0.066-0.95 | 0.019-0.043 | 4.544-96.157 | 1.665-9.173 | 6.735-253.897 |

| Avg., | 1860.223 | 0.391 | 11.932 | 0.506 | 0.615 | 6.863 | 1.166 | 7.741 | 3.397 | 3.181 | 4.437 | 0.287 | 0.028 | 26.371 | 3.126 | 70.573 | |

| SD (±) | 515.404 | 0.290 | 5.453 | 0.459 | 0.210 | 5.401 | 0.665 | 3.831 | 0.820 | 1.396 | 1.593 | 0.188 | 0.000 | 23.059 | 1.373 | 68.319 | |

| West Coast of India River Average Silt (WCIRAS) | Range | 1082.666-3848.586 | 0.065-5.317 | 5.677-111.194 | 0.132-6.734 | 0.068-1.117 | 0.201-24.939 | 0.316-10.611 | 3.034-103.999 | 1.158-6.759 | 1.007-31.859 | 1.043-18.264 | 0.066-1.357 | 0.017-0.046 | 1.016-236.694 | 1.665-16.082 | 1.083-253.897 |

| Avg., | 1878.625 | 0.702 | 18.248 | 0.811 | 0.533 | 4.111 | 2.068 | 15.819 | 3.308 | 5.486 | 4.888 | 0.450 | 0.028 | 22.265 | 3.316 | 39.803 | |

| SD (±) | 593.281 | 0.782 | 16.209 | 0.753 | 0.200 | 4.375 | 1.969 | 17.250 | 1.211 | 4.833 | 3.329 | 0.277 | 0.005 | 28.979 | 1.722 | 52.236 | |

| Reference Sediments | PAAS | 1807.090 | 0.919 | 13.216 | 0.733 | 0.497 | 1.575 | 2.804 | 9.130 | 3.052 | 7.157 | 4.710 | 0.800 | - | 7.534 | 2.000 | 10.274 |

| UCC | 1650.870 | 0.721 | 13.786 | 0.952 | 0.444 | 1.713 | 2.243 | 11.156 | 3.109 | 3.353 | 3.840 | 0.256 | - | 9.139 | 1.951 | 9.604 | |

| APT: Archean- Proterozoic Terrain (this study); DTT: Deccan Trap Terrain (this study); WCIRAS: West Coast of India River Average Silt (this study); PASS: Post Archean average Australian Shale (Pourmand et al. 2012); UCC: Upper Continental Crust (Rudnick and Gao 2003). | |||||||||||||||||

|

APT DTT |

SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | TiO2 | P2O5 | ∑REE | Y | La | Ce | Yb | Zr | Hf | U | Th | Sc | V | Cr | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Rb | Sr | Nb | Cs | Ba | Ta | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 1 | -0.27 | -0.57 | -0.07 | 0.18 | 0.43 | -0.58 | 0.08 | 0.06 | -0.38 | -0.50 | -0.15 | -0.41 | -0.50 | -0.45 | 0.03 | 0.01 | -0.61 | -0.28 | 0.01 | -0.20 | 0.01 | -0.15 | -0.01 | -0.37 | 0.01 | -0.37 | 0.04 | 0.26 | -0.11 | -0.04 | 0.14 | -0.26 | -0.20 |

| Al2O3 | -0.39 | 1 | -0.02 | -0.21 | -0.53 | -0.60 | -0.18 | -0.28 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.09 | -0.19 | -0.03 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.54 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.28 | -0.01 | 0.34 | -0.16 | -0.21 | -0.09 | 0.22 | -0.11 | 0.68 | -0.04 | -0.31 | 0.54 | 0.11 | -0.31 | 0.60 | 0.20 |

| Fe2O3 | -0.31 | -0.04 | 1 | 0.24 | -0.18 | -0.39 | 0.15 | 0.02 | -0.39 | 0.14 | 0.64 | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.36 | -0.18 | -0.17 | 0.50 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.03 | -0.38 | -0.12 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.23 |

| MnO | -0.19 | -0.12 | 0.32 | 1 | -0.10 | -0.05 | -0.12 | -0.29 | -0.08 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.68 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.57 | -0.01 | -0.01 | -0.29 | -0.33 | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.66 | 0.21 | 0.40 | 0.23 | -0.12 | -0.46 | -0.20 | -0.47 | -0.44 | 0.38 | -0.28 | 0.15 |

| MgO | -0.21 | -0.28 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 1 | 0.65 | -0.14 | 0.52 | -0.27 | -0.33 | -0.24 | -0.11 | -0.02 | -0.35 | -0.43 | -0.44 | -0.44 | -0.38 | -0.18 | -0.27 | -0.61 | -0.08 | -0.28 | -0.11 | -0.33 | -0.03 | -0.66 | 0.19 | 0.44 | -0.28 | 0.05 | -0.06 | -0.30 | -0.21 |

| CaO | -0.29 | -0.45 | -0.06 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 1 | -0.18 | 0.58 | -0.23 | -0.34 | -0.30 | -0.17 | -0.07 | -0.38 | -0.52 | -0.40 | -0.45 | -0.56 | -0.10 | -0.23 | -0.57 | -0.12 | -0.33 | -0.14 | -0.41 | -0.12 | -0.63 | 0.31 | 0.77 | -0.16 | 0.18 | 0.34 | -0.17 | -0.27 |

| Na2O | -0.20 | -0.50 | -0.28 | -0.15 | 0.17 | 0.71 | 1 | -0.06 | -0.11 | -0.10 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.23 | -0.12 | -0.14 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.08 | -0.06 | 0.02 | -0.05 | 0.12 | -0.09 | 0.10 | -0.05 | -0.12 | -0.06 | -0.05 | -0.17 | -0.09 | -0.11 |

| K2O | -0.10 | -0.63 | -0.24 | 0.11 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.75 | 1 | -0.35 | -0.12 | 0.12 | -0.40 | 0.33 | 0.19 | -0.52 | -0.45 | -0.47 | 0.09 | 0.50 | -0.58 | -0.74 | -0.25 | -0.47 | -0.25 | -0.36 | -0.17 | -0.28 | 0.83 | 0.47 | 0.31 | 0.72 | 0.14 | 0.26 | -0.01 |

| TiO2 | 0.37 | -0.05 | -0.05 | -0.25 | 0.00 | -0.14 | -0.08 | -0.02 | 1 | 0.33 | -0.30 | -0.06 | -0.42 | -0.20 | 0.15 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.06 | -0.18 | 0.22 | 0.61 | -0.11 | -0.13 | -0.05 | 0.07 | -0.08 | 0.50 | -0.36 | -0.43 | 0.44 | -0.24 | -0.19 | 0.38 | -0.05 |

| P2O5 | -0.67 | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.11 | -0.05 | -0.04 | -0.16 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.23 | -0.03 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.61 | 0.30 | 0.28 | -0.08 | -0.34 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.58 |

| ∑REE | -0.64 | 0.43 | -0.02 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.15 | -0.02 | -0.02 | -0.15 | 0.79 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.46 | -0.33 | -0.32 | 0.51 | 0.57 | -0.06 | -0.01 | -0.05 | 0.21 | -0.09 | 0.11 | -0.09 | 0.23 | 0.16 | -0.26 | 0.09 | 0.10 | -0.02 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| Y | -0.71 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.22 | -0.01 | 0.00 | -0.28 | 0.58 | 0.70 | 1 | 0.14 | -0.02 | 0.84 | 0.18 | 0.18 | -0.33 | -0.50 | 0.71 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.66 | 0.06 | 0.41 | 0.12 | -0.08 | -0.65 | -0.23 | -0.62 | -0.68 | -0.02 | -0.46 | -0.19 |

| La | -0.62 | 0.46 | -0.08 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.13 | -0.01 | -0.02 | -0.12 | 0.76 | 0.99 | 0.66 | 1 | 0.84 | 0.19 | -0.60 | -0.58 | 0.43 | 0.69 | -0.31 | -0.30 | -0.02 | 0.02 | -0.09 | -0.06 | -0.09 | 0.01 | 0.39 | -0.08 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.15 |

| Ce | -0.58 | 0.41 | -0.01 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.10 | -0.07 | -0.03 | -0.15 | 0.77 | 0.98 | 0.62 | 0.95 | 1 | 0.21 | -0.26 | -0.26 | 0.75 | 0.79 | -0.27 | 0.03 | -0.06 | 0.04 | -0.09 | 0.04 | -0.12 | 0.43 | 0.37 | -0.28 | 0.40 | 0.36 | -0.02 | 0.50 | 0.25 |

| Yb | -0.71 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.01 | -0.08 | -0.20 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.94 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.10 | -0.26 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.01 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 0.30 | -0.63 | -0.48 | -0.29 | -0.57 | -0.16 | -0.11 | -0.06 |

| Zr | 0.40 | -0.29 | 0.05 | -0.15 | 0.05 | -0.10 | -0.07 | 0.09 | 0.53 | -0.39 | -0.52 | -0.28 | -0.52 | -0.52 | -0.16 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.07 | -0.37 | 0.53 | 0.68 | -0.24 | 0.07 | -0.14 | 0.25 | -0.16 | 0.59 | -0.45 | -0.39 | 0.22 | -0.26 | -0.23 | 0.21 | -0.20 |

| Hf | 0.31 | -0.23 | 0.02 | -0.15 | 0.07 | -0.05 | -0.03 | 0.09 | 0.56 | -0.33 | -0.44 | -0.21 | -0.44 | -0.45 | -0.07 | 0.98 | 1 | 0.09 | -0.36 | 0.50 | 0.65 | -0.23 | 0.06 | -0.14 | 0.26 | -0.15 | 0.56 | -0.50 | -0.42 | 0.20 | -0.29 | -0.27 | 0.21 | -0.17 |

| U | 0.41 | -0.48 | 0.00 | -0.13 | 0.15 | -0.09 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.15 | -0.43 | -0.46 | -0.26 | -0.43 | -0.43 | -0.34 | 0.53 | 0.44 | 1 | 0.70 | -0.34 | 0.13 | -0.08 | -0.19 | -0.04 | 0.19 | -0.07 | 0.65 | 0.34 | -0.32 | 0.61 | 0.44 | -0.23 | 0.65 | 0.36 |

| Th | 0.20 | 0.03 | -0.13 | -0.07 | -0.23 | -0.21 | -0.17 | 0.00 | 0.27 | -0.04 | 0.18 | -0.16 | 0.25 | 0.25 | -0.23 | -0.01 | -0.05 | 0.31 | 1 | -0.67 | -0.28 | -0.09 | -0.35 | -0.11 | -0.15 | -0.13 | 0.25 | 0.77 | -0.05 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.13 | 0.72 | 0.36 |

| Sc | -0.33 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.18 | -0.01 | 0.11 | 0.06 | -0.15 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.46 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.11 | -0.45 | -0.38 | 1 | 0.60 | -0.06 | 0.44 | -0.05 | 0.30 | -0.06 | 0.29 | -0.74 | -0.26 | -0.51 | -0.69 | -0.06 | -0.44 | -0.40 |

| V | 0.23 | -0.33 | 0.50 | -0.04 | -0.21 | -0.06 | -0.03 | -0.10 | 0.40 | -0.32 | -0.43 | -0.16 | -0.50 | -0.40 | -0.01 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.05 | -0.19 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.11 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.66 | -0.63 | -0.60 | 0.07 | -0.45 | 0.03 | 0.09 | -0.01 |

| Cr | 0.21 | -0.13 | 0.10 | -0.08 | -0.13 | 0.04 | -0.02 | -0.18 | 0.09 | -0.22 | -0.25 | -0.08 | -0.32 | -0.21 | -0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 | -0.16 | -0.27 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 1 | 0.67 | 0.98 | 0.56 | 0.94 | -0.17 | -0.16 | -0.13 | -0.19 | -0.13 | 0.17 | -0.22 | 0.73 |

| Co | -0.46 | -0.14 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.17 | -0.22 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.56 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.52 | -0.10 | -0.07 | -0.19 | -0.28 | 0.48 | 0.39 | -0.01 | 1 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.65 | -0.03 | -0.51 | -0.32 | -0.45 | -0.46 | 0.18 | -0.38 | 0.41 |

| Ni | 0.08 | -0.14 | 0.27 | -0.09 | -0.20 | 0.02 | -0.01 | -0.21 | 0.05 | -0.21 | -0.33 | -0.15 | -0.40 | -0.31 | -0.05 | 0.05 | 0.10 | -0.22 | -0.32 | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.78 | 0.23 | 1 | 0.63 | 0.96 | -0.12 | -0.16 | -0.13 | -0.14 | -0.11 | 0.11 | -0.17 | 0.75 |

| Cu | 0.32 | -0.38 | 0.42 | -0.05 | -0.12 | -0.09 | -0.11 | -0.12 | 0.05 | -0.34 | -0.53 | -0.24 | -0.57 | -0.50 | -0.18 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.11 | -0.19 | 0.22 | 0.69 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.23 | -0.34 | -0.38 | -0.12 | -0.19 | 0.08 | -0.01 | 0.61 |

| Zn | 0.40 | -0.29 | -0.07 | -0.12 | -0.10 | -0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | -0.05 | -0.28 | -0.39 | -0.34 | -0.35 | -0.38 | -0.40 | -0.03 | -0.15 | 0.36 | 0.08 | -0.35 | -0.03 | 0.01 | -0.24 | -0.05 | 0.31 | 1 | -0.18 | -0.14 | -0.10 | -0.17 | -0.10 | 0.09 | -0.20 | 0.78 |

| Ga | -0.04 | 0.56 | -0.23 | -0.28 | -0.75 | -0.38 | -0.20 | -0.51 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.12 | -0.28 | -0.24 | -0.47 | 0.33 | 0.11 | -0.05 | 0.10 | -0.24 | 0.11 | -0.17 | -0.12 | 1 | -0.06 | -0.51 | 0.52 | 0.13 | -0.16 | 0.52 | 0.05 |

| Rb | -0.10 | -0.05 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.33 | -0.05 | -0.19 | 0.37 | -0.04 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.02 | -0.06 | 0.41 | 0.36 | -0.25 | -0.27 | -0.36 | 0.11 | -0.41 | -0.13 | 0.07 | -0.27 | 1 | 0.34 | 0.59 | 0.95 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.18 |

| Sr | -0.45 | 0.07 | -0.03 | 0.28 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.35 | -0.23 | -0.16 | -0.22 | -0.15 | 0.02 | -0.36 | -0.21 | 0.23 | -0.27 | -0.44 | -0.30 | -0.11 | 0.12 | 1 | -0.15 | 0.25 | 0.14 | -0.15 | -0.18 |

| Nb | 0.31 | -0.06 | -0.19 | -0.30 | -0.35 | -0.17 | -0.07 | -0.04 | 0.64 | -0.06 | 0.10 | -0.27 | 0.14 | 0.15 | -0.25 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.72 | -0.19 | 0.13 | -0.06 | -0.34 | -0.04 | -0.15 | -0.11 | 0.44 | 0.04 | -0.04 | 1 | 0.69 | -0.03 | 0.91 | 0.25 |

| Cs | 0.28 | -0.48 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.20 | -0.04 | -0.07 | 0.32 | 0.25 | -0.39 | -0.46 | -0.18 | -0.46 | -0.43 | -0.23 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.75 | 0.28 | -0.20 | 0.28 | -0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.29 | -0.46 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.22 | 1 | 0.21 | 0.62 | 0.25 |

| Ba | -0.54 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.08 | -0.09 | -0.03 | -0.03 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.47 | -0.41 | -0.34 | -0.52 | 0.07 | 0.13 | -0.32 | -0.27 | 0.23 | -0.31 | -0.44 | -0.37 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.11 | -0.45 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.22 |

| Ta | 0.64 | -0.40 | -0.08 | -0.26 | -0.24 | -0.22 | -0.12 | 0.05 | 0.48 | -0.44 | -0.43 | -0.53 | -0.39 | -0.36 | -0.54 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.61 | 0.65 | -0.38 | 0.29 | 0.01 | -0.31 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.75 | 0.61 | -0.39 | 1 | 0.25 |

| Pb | -0.04 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.02 | -0.16 | -0.10 | -0.16 | -0.08 | -0.11 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.04 | -0.20 | -0.30 | 0.13 | 0.23 | -0.27 | -0.19 | -0.21 | 0.00 | -0.22 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.35 | -0.03 | 0.13 | 0.15 | -0.04 | 1 |

4. Results

4.1. Minerals in the Clay Fraction of Sediments

4.2. Distribution of Major Elements

4.3. Weathering Indices

4.4. Distribution of Trace Elements

4.5. Relationships of Major and Trace Elements

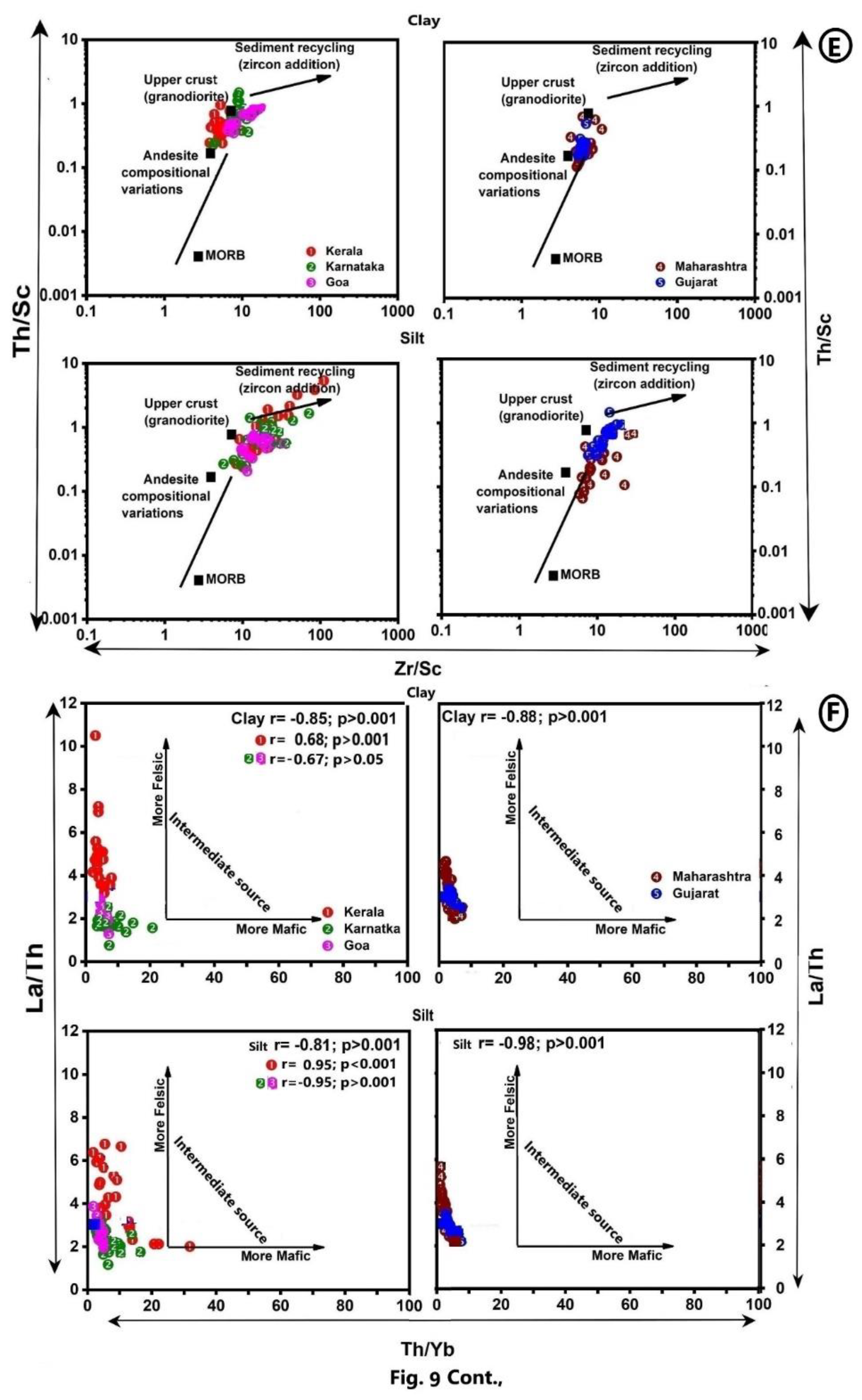

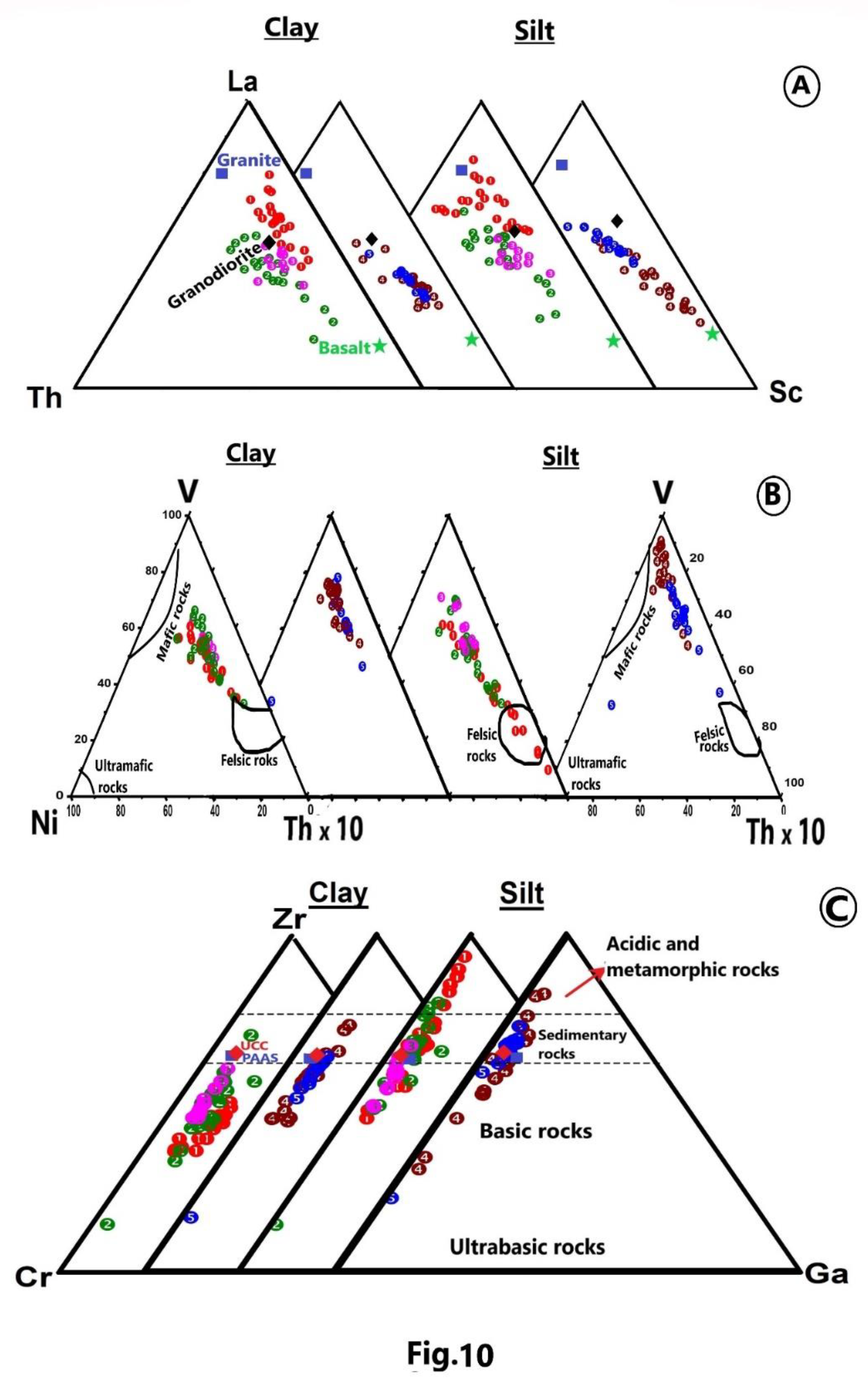

5. Discussion

5.1. Mineralogy and Major Element Geochemistry—Stages of Weathering

5.2. Major Element Chemistry—Provenance

5.3. Relationships among Major Elements and Trace Elements

5.4. Factors Controlling ∑TE in the Sediments

5.5. Factors Controlling Th/U and Rb/Sr Ratios—Lithology and Chemical Weathering

5.6. Dominance of Mafic/Felsic Source Component in the Sediments

5.7. Summary and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Abedini, A.; Calagari, A.A.; and Mikaeili, K. Geochemical characteristics of laterites: The Ailibaltalu Deposit, Iran; Bull. Miner. Res. Explor. 2014, 148, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absar, N.; Sreenivas, B. Petrology and geochemistry of greywackes of the 1.6 Ga Middle Aravalli Supergroup, northwest India: Evidence for active margin processes. Int. Geol. Rev. 2015, 57, 134–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amajor, L.C. Major and trace element geochemistry of Albian and Turonian shales from the Southern Benue trough, Nigeria. J. African Earth Sci. 1987, 6, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Altrin, J.S.; Nagarajan, R.; Madhavaraju, J.; RosalezHoz, L.; Yong, I.L.L.; Balaram, V.; Cruz-Martınez, A.; AvilaRamırez, G. Geochemistry of the Jurassic and Upper Cretaceous shales from the Molango Region, Hidalgo, eastern Mexico: Implications for source-area weathering, provenance, and tectonic setting. C. R. Geosci. 2013, 345, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Altrin, J.S.; Madhavaraju, J.; Vega-Bautista, F.; Ramos-V’azquez, M.A.; P’erez- Alvarado, B.Y.; Kasper-Zubillaga, J.J.; Bessa, A.Z.E. Mineralogy and geochemistry of Tecolutla and Coatzacoalcos beach sediments, SW Gulf of Mexico. Appl. Geochem. 2021, 134, 105103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babechuk, M.G.; Widdowson, M.; Kamber, B.S. Quantifying chemical weathering intensity and trace element release from two contrast ing basalt profiles, Deccan traps, India. Chem Geo. 2014, 363, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babechuk, M.G.; Widdowson, M.; Murphy, M.; Kamber, B.S. A combined Y/Ho, high field strength element (HFSE) and isotope perspective on basalt weathering, Deccan traps, India. Chem Geol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babechuk, M.; Fedo, C. Analysis of chemical weathering trends across three compositional dimensions: applications to modern and ancient mafic-rock weathering profiles. Can J Earth Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, K. S, Surendra, M.; Kumar, T.V. Genesis of certain bauxite profiles from India. Chem. Geol. 1987, 60, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayon, G.; Toucanne, S.; Skonieczny, C.; Andre, L.; Bermell, S.; Cheron, S.; Dennielou, B.; Etoubleau, J.; Freslon, N.; Gauchery, T.; Germain, Y.; Jorry, S.J.; Menot, G.; Monin, L.; Ponzevera, E.; Rouget, M.L.; Tachikawa, K.; Barrat, J.A. Rare earth elements and neodymium isotopes in world river sediments revisited. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2015, 170, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, R.A.; Berner, E.K. Silicate weathering and climate. In Tectonic Uplift and Climate Change; Ruddiman, W.F., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, 1997; pp. 354–365. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, M.R. Plate tectonics and geochemical composition of sandstones. Journal of Geology 1983, 91, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M.R.; Crook, K.A.W. Trace element characteristics of graywackes and tectonic setting discrimination of sedimentary basin. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1986, 92, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.A.H.; Rahman, M.J.J.; Dampare, S.B.; Suzuki, S. Provenance, tectonics and source weathering of modern fluvial sediments of the Brahmaputra-Jamuna River, Bangladesh: Inference from geochemistry. J. Geochem. Explor. 2011, 111, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, J.D.; Erel, Y. Rb-Sr isotope systematics of a granitic soil chronosequence: the importance of biotite weathering. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1997, 61, 3193–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.B.; Huh, Y.; Moon, S.; Noh, H. Provenance and weathering control on river bed sediments of the eastern Tibetan Plateau and the Russian Far East. Chem. Geol. 2008, 254, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boruah, R.; Laskar, J.J. Geochemical characteristics of Neogene sandstones of the East and West Siang Districts of Arunachal Pradesh, NE India: implications for source-area weathering, provenance, and tectonic setting. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2022, 41, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracciali, L.; Marroni, M.; Pandol, B.L.; Rocchi, S.; Arribas, J.; Critelli, S.; Johnsson, M.J. Geochemistry and petrography of Western Tethys Cretaceous sedimentary covers (Corsica and Northern Apennines): From source areas to configuration of margins. Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Paper. 2007, 420, 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chamley, H. Clay mineralogy; Clay mineralogy: Germany, 1989; Volume 623. [Google Scholar]

- Chougong, D.T.; Bessa, Z.E.; Ntyam, S.C.; Yongue, R.F.; Ngueutchoua, G.; Armstrong-Altrin, J.S. Mineralogy and geochemistry of Lob´ e River sediments, SW Cameroon: Implications for provenance and weathering. Journal of African Earth Sciences. 2021, 183, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condie, K.C. Chemical composition and evolution of the upper continental crust: Contrasting results from surface samples and shales. Chemical Geology 1993, 104, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.; Lowe, D.R.; Cullers, R.L. The influence of sediment recycling and basement composition on evolution of mudrock chemistry in the southwestern United States. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1995, 59, 2919–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullers, R.L. The controls on the major and trace element variation of shales, siltstones, and sandstones of Pennsylvanian-Permian age from uplifted continental blocks in Colorado to platform sediment in Kansas, USA. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1994, 58, 4955–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullers, R. The geochemistry of shales, siltstones and sandstones of Pennsylvanian–Permian age, Colorado, USA: Implications for provenance and metamorphic studies. Lithos. 2000, 51, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullers, R.L. Implications of elemental concentrations for provenance, redox conditions, and metamorphic studies of shales and limestones near Pueblo, Co, USA; Chem. Geol. 2002, 191, 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, A.G; Arolkar, D.B.; French, D.; Viegas, A.; Vishwanath, T.A. Petrogenesis of the Bondla layered mafic-ultramafic complex Usgaon, Goa. J Geo Soc India. 2009, 73, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhoundial, D.P.; Paul, D.K.; Sarkar, A.; Trivedi, J.R.; Gopalan, K.; Potts, P.J. Geochronology and geochemistry of the precambrian granitic r ocks of Goa, SW India. J Precam Res. 1987, 36, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.D.; Chen, L.Q.; Bai, Y.H.; Hu, H.P. Variations in rare earth elements with environmental factors in lake surface sediments from 17 lakes in western China. J Mt Sci. 2021, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedo, C.M.; Wayne Nesbitt, H.; Young, G.M. Unraveling the effects of potassium metasomatism in sedimentary rocks and paleosols, with implications for paleoweathering conditions and provenance. Geology. 1995, 23, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedo, C.M.; Eriksson, K.A.; Krogstad, E.J. Geochemistry of shales from the Archaean (*3.0 Ga) Buhwa greenstone belt, Zimbabwe: Implications for provenance and sourcearea weathering. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1996, 60, 1751–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, R.L. Petrology of the sedimentary rocks; Hemphills: Austin, TX, 1968; Volume 170. [Google Scholar]

- Garzanti, E.; Resentini, A. Provenance control on chemical indices of weathering (Taiwan river sands). Sed. Geol. 2016, 336, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokul, A.R.; Srinivasan, M.D.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Viswanathan, L.S. Stratig raphy and structure of Goa. Seminar volume on Earth resources for Goa’s development. Geo Surv of India 1985, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.X.; Liu, J.M.; Zheng, M.H.; Tang, J.X.; Qt, L. Provenance and tectonic setting of the Proterozoic turbidites in Hunan, South China: Geochemical Evidence. J. Sedim. Res. 2002, 72, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, H.; Peng, X. Geochemistry and sedimentology of sediments in a short fluvial system, NW China: implications to the provenance and tectonic setting. Journal of Oceanology and Limnology. 2023, 41, 5–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurumurthy, G.P. Geochemical split among the suspended and mud sediments in the Nethravati River: insights to compositional similarity of peninsular gneiss and the Deccan Basalt Derived sediments, and its implications on tracing the provenance in the Indian Ocean. Geochem Geophys Geosyst, 2024, 25, e2024GC011642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.I.; Fujisawa, H.; Holland, H.D.; Ohmoto, H. Geochemistry of~ 1.9 Ga sedimentary rocks from northeastern Labrador, Canada. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1997, 61, 4115–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Garzanti, E.; Dinis, P.; Yang, S.; Wang, H. Provenance versus weathering control on sediment composition in tropical monsoonal climate (South China) - 1. Geochemistry and clay mineralogy. Chem. Geol. 2020, 558, 119860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, H.M.; Hasna Hossain, Q.; Kamei, A.; Araoka, D. Compositional variations, chemical weathering, and provenance of sands from the Cox’s Bazar and Kuakata beach areas, Bangladesh. Arabian J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, H.M. Major, trace, and REE geochemistry of the Meghna River sediments, Bangladesh: Constraints on weathering and provenance. Geological Journal. 2020, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, A.; Beauvais, A.; Chordon, D.; Arnaud, N.; Jayananda, M.; Mathe, P.E. Weathering history and landscape evolution of western ghats (India) from 40Ar/39Ar dating of supergene K–Mn oxides. J. Geol Soc. 2020, 177, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Cao, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, S. A Rb/Sr record of catchment weathering response to Holocene climate change in Inner Mongolia. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, V. The Western Ghat: The Great Escarpment of India. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Kaotekwar, A.B.; Rajkumar, R.; Satyanarayana, M.; Keshav Krishna, A.; Charan, S.N. Structures, Petrography and Geochemistr y of Deccan Basalts at Anantagiri Hills, Andhra Pradesh. J Geol Soc India. 2014, 84, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessarkar, P.M.; Rao, V.P.; Ahmad, S.M.; Babu, G.A. Clay minerals and Sr–Nd isotopes of sediments along the western margin of India and their implication for sediment provenance. Mar. Geol. 2003, 202, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessarkar, P.M.; Suja, S.; Sudheesh, V. Iron ore pollution in Mandovi and Zuari estuarine sediments and its fate after mining ban. Envi ron Monit Assess. 2015, 187, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, M.S. Geology of India and Burma; Higgin Bothoms: Madras, 1968; Volume 536. [Google Scholar]

- Kump, L.R.; Brantley, S.L.; Arthur, M.A. Chemical weathering, atmospheric CO2 and climate. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2000, 28, 611–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, P.C.; Hawkesworth, C.J.; Devey, C.W.; Rogers, N.W.; van Calsteren, P.W.C. Source and di¡erentia tion of Deccan Trap lavas: imp lications of geochemical and mineral chemical variations. J Petrol. 1990, 31, 1165–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yu, K.; Li, A.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Lan, J. Weathering Intensity Response to Climate Change on Decadal Scales: A Record of Rb/Sr Ratios from Chaonaqiu Lake Sediments, Western Chinese Loess Plateau. Water 2007, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Yang, P. Geochemistry and U-Pb zircon ages of metamorphic volcanic rocks of the Paleoproterozoic Lüliang Complex and constraints on the evolution of the Trans-North China Orogen, North China Craton. Precambr. Res. 2012, 222, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupker, M.; France-Lanord, C.; Galy, V.; Lav´ e, J.; Kudrass, H. Increasing chemical weathering in the Himalayan system since the Last Glacial Maximum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 365, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharana, C.; Srivastava, D.; Tripathi, J.K. Geochemistry of sediments of the Peninsular rivers of the Ganga basin and its implication to weathering, sedimentary processes and provenance. Chem. Geol. 2018, 483, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, T.K.; Vasudevan, V.; Verghese, P.A.; Machado, T. The black sand placer deposits of Kerala, Southwest India. Mar Geol. 1987, 77, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.J.; Doyne, H.C. Laterite and lateritic soils in Sierra Leone. J Agr Sci. 1927, 17, 530–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, A.; Kalavampara, G. Natural resources of Goa: a geological perspective. Geological Society of Goa, Miramar 2009, 213. [Google Scholar]

- McLennan, S.M.; Taylor, S.R. Th and U in sedimentary rocks: Crustal evolution and sedimentary recycling. Nature. 1980, 285, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, S.M. Rare earth elements in sedimentary rocks: Influence of provenance and sedimentary processes. Reviews in Mineralogy. 1989, 21, 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- McLennan, S.M.; Taylor, S.R.; McCulloch, M.T.; Maynard, J.B. Geochemistry and Nd–Sr isotopic composition of deepsea turbidites: crustal evolution and plate tectonic associations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1990, 54, 2014–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, S.M.; Hemming, S.; McDaniel, D.K.; Hanson, G.N. Geochemical approaches to sedimentation, prove nance and tectonics. In: Johnsson JM, Basu A (eds) Processes controlling the composition of clastic sediments. Geol Soc Am, USA 1993, 284, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Naidu, A.S.; Mowatt, T.C.; Somayajulu, B.L.K.; Sreeramachandra Rao, K. Characteristics of clay minerals in the bed loads of major rivers of India. In: Degens, E.T., Kempe, S., Herrera, R. (Eds.), Transport of Carbon and Minerals in Major World Rivers, Pt.3. Mitt. Geol.-Paläont Inst. Univ., Scope/Unep Sonderbd, Hamburg. 1985, 58, 559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, S.M. Geology and evolution of the Indian plate (from Hadean to Holocene 4 Ga to 4 Ka); Capital Publishing Company: New Delhi, 2005; Volume 450. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanaswamy, S. Geochemistry and genesis of laterite in parts of Cannanore District, North Kerala. PhD Thesis, Cochin University of Science and Technology, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt, H.w.; Young, G.M. Early Proterozoic climates and plate motions inferred from major element chemistry of lutites. Nature 1982, 299, 715–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, H.W.; Young, G.M. Petrogenesis of sediments in the absence of chemical weathering: effects of abrasion and sorting on bulk composition and mineralogy. Sediment 1996, 43, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, H.W.; Markovics, G. Weathering of granodiorite crust, long-term storage of elements in weathering profiles, and petrogenesis of siliciclastic sediments. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1997, 6, 1653–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmand, A.; Dauphas, N.; Ireland, T.J. A novel extraction chromatography and MC–ICP–MS technique for rapid analysis of REE, sc and Y: revising CI-chondrite and post-archean Australian Shale (PAAS) abundances. Chem Geol. 2012, 291, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajith, A.; Rao, V.P.; Kessarkar, P.M. Controls on the distri bution and fractionation of yttrium and rare earth elements in core sedimen ts from the Mandovi estuary, western India. Cont Shelf Res. 2015, 92, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.R.; Velbel, M.A. Chemical weathering indices applied to weathering profiles developed on heterogeneous felsic metamorphic parent rocks. Chemical Geology 2003, 202, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourret, O.; Davranche, M. Rare earth element sorption onto hydrous manganese oxide: a modeling study. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 395, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishna, B.P. Archaean granite-greenstone terrain of south Indian shield. In: Naqvi SM, Rogers JJW (eds) Precambrian of South India, Geol Soc India Memoir, 1983, 4, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, Md.A.; Das, S.C.; Pownceby,M. I.; Alam, Md.S.; Zaman, M.N. Geochemistry of Recent Brahmaputra River Sediments: Provenance, Tectonics, Source Area Weathering and Depositional Environment. Minerals 2020, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, R.; Subramanian, V.; Van Grieken, R.; Van’t Dack, L. The elemental chemistry of sediments in the Krishna River basin, India. Chem. Geol. 1989, 74, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.L. India’s water wealth. Orient Longman Ltd., New Delhi, 1975; 255. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V.P.; Rao, B.R. Provenance and distribution of clay minerals in the continental shelf and slope sediments of the west coast of India; Cont. Shelf Res. 1995, 15 1757–1771.

- Rao, V.P.; Wagle, B.G. Geomorphology and surBcial geology of the western continental shelf and slope of India: A review. Curr. Sci. 1997, 73, 330–350. [Google Scholar]

- Roser, B.P. Whole-rock geochemical studies of clastic sedimentary suites. Memoirs of the Geological Society of Japan 2000, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Roser, B.P.; Korsch, R.J. Determination of tectonic setting of sandstone-mudstone suites using SiO2 content and K2O/Na2O ratio. J. Geol. 1986, 94, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roser, B.P.; Korsch, R.J. Provenance signatures of sandstone-mudstone suites determined using discriminant function analysis of major-element data. Chem. Geol. 1988, 67, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.K.; Roser, B.P. Geochemical evolution of the Tertiary succession of the NW shelf, Bengal basin, Bangladesh: Implications for provenance, paleoweathering and Himalayan erosion. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 78, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R.L.; Gao, S.; Holland, H.D.; Turekian, K.K. Composition of the continental crust. The Crust. 2003, 3, 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, A.; Roy, D.K.; Idris, A.M.; Khan, R.; Biswas, P.K.; Ornee. T.I.; Tami. Provenance, weathering, climate and tectonic setting of Padma River sediments, Bangladesh: A geo chemical approach. Catena. 2023, 233, 107485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.K.; Guimar, J.T.F.; Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; Sousa da Silva, M.; Nascimento, W.; Powell, M.A., Jr.; Reis, L.S.; Pessenda, L.C.R.; Rodrigues, T.M.; Fonseca da, Silva, D. ; Eliodoro Costa, V.Geochemical characterization of the largest upland lake of the Brazilian Amazonia: Impact of provenance and processes. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2017, 80, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai Babu, Sk.; Ramana, R.V.; Rao, V.P.; Rammohan, M.; Krishna, A.K.; Sawant, S.; Satyasree, N.; Krishna, A.K. Composition of the peninsular India rivers average clay (PIRAC): a reference sediment composition for the upper crust from peninsular India. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 129, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai Babu, Sk.; Prajith, A.; Rao, V.P.; Rammohan, M.; Ramana, R.V.; Satyasree, N.S. Composition of river sediments from Kerala, southwest India: Inferences on lateritic weathering. J Earth Syst Sci. 2023, 132, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saibabu, Sk.; Rao, V.P.; Satyasree, N.; Ramana, R. V.; Rammohan, M.; and Sawant, S. Mineralogy and geochemistry of the sediments in rivers along the east coast of India: Inferences on weathering and provenance. J. Earth Syst. Sci. [CrossRef]

- Sai Babu, Sk.; Rao, V.P.; Rammohan, M. Controls on the distribution and fractionation of rare earth elements in recent sediments from the rivers along the west coast of India. Environmental Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, K.; Chen, C.T.A. Moderate chemical weathering of subtropical Taiwan: constraints from solid-phase geochemistry of sediments and sedimentary rocks. J. Geol. 2006, 114, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensarma, S.; Rajamani, V.; Tripathi, J.K. Petrography and geochemical characteristics of the sediments of the small River Hemavati, Southern India: implication for provenance and weathering processes. Sed. Geol. 2008, 205, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Rajamani, V. Weathering of charnockite and sediment production in the catchment area of the Cauvery River, southern India. Sed. Geol. 2001, 143, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sensarma, S.; Kumar, K.; Khanna, P.P.; Saini, N.K. Mineralogy and geochemistry of the Mahi River sediments in tectonically active western India: implications for Deccan large igneous province source, weathering and mobility of elements in a semi-arid climate. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2013, 104, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellmann, W. A new definition of laterites. Geol. Surv. India Memoir 1986, 120, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shynu, R.; Rao, V.P.; Kessarkar, P.M.; Rao, T.G. Rare earth elements in suspended and bottom sediments of the Mandovi estuary, central west coast of India: influence of mining. Estu Coast Shelf Sci. 2011, 94, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shynu, R.; Rao, V.P.; Parthiban, G.; Balakrishnan, S.; Narvekar, T.; Kessarkar, P.M. REE in suspended particulate matter and sediment of the Zuari estuary and adjacent shelf, western India: influence of mining and estuarine turbidity. Mar Geol. 2013, 346, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shynu, R.; Rao, V.P.; Kessarkar, P.M. Major and trace metals in suspended and bottom sediments of the Mandovi and Zuari estuaries: d istribution, source and pollution. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Rajamani, V. REE geochemistry of recent clastic sediments from the Kaveri Flood plains, southern India: implication to so urce area weathering and sedimentary processes. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2001, 65, 3093–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viers, J.; Dupré, B.; Raun, J.J.; Deberdt, S.; Angeletti, B.; Ngoupa, J.N.; Michard, A. Major and trace element abundances, and strontium isotopes in the Nyong basin rivers (Cameroon): constraints on chemical weathering processes and elements transport mechanisms in humid tropical environments. Chem. Geol. 2000, 169, 1–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soman, K. Geology of Kerala, 2nd edn; Geological Society of India: Bangalore, 2002; Volume 335. [Google Scholar]

- Sreenath, A.V.; Abhilash, S.; Vijaykumar, P. West coast of India’s rainfall is becoming more convective. J. Clim Atmos Sci. 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suja, S.; Lina, F.; Rao, V.P. Distribution and fractionation of rare earth elements and Yttrium in suspended and bottom sediments of the Kali estuary, western India. Environ Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, V.; Van’t Dack, L.; Van Grieken, R. Chemical composition of river sediments from the Indian subcontinent. Chem. Geol. 1985, 48, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. The continental crust: Its composition and evolution. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Palo Alto, CA, USA, Malden, 1985; 312. [Google Scholar]

- Wampler, J.W.; Krogstad, E.J.; Elliott, W.C.; Kahn, B.; Kaplan, D.J. Long-term selective retention of natural Cs and Rb by highly weathered coastal plain soils. Environm. Sci. Tech. 2012, 46, 3837–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widdowson, M.; Cox, K.G. Uplift and erosion history of the Deccan traps, India: evidence from laterites and drainage patterns of the western ghats and Konkan Coast. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1996, 137, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronkiewicz, D.J.; Condie, K.C. Geochemistry and provenance of sediments from the Pongola Supergroup, South Africa: evidence for a 3.0-Ga-old continental craton. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1989, 53, 1537–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, B.; Wu, F. Spatial and temporal variations of Rb/Sr ratios of the bulk surface sediments in Lake Qinghai. Geochemical Transactions. 2010, 11–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Jung, H.S.; Li, C.X. Two unique weathering regimes in the Changjiang and Huanghe drainage basins: geochemical evidence from river sediments. Sedimentary Geology 2004, 164, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| State (No. of Rivers) |

SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | TiO2 | P2O5 | SiO2/Al2O3 | Fe2O3/Al2O3 | Al2O3/TiO2 | CIA | PIA | ICV | MIA (O) | MIA (R) | IOL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kerala (21) | Range | 29.01-40.66 | 11.37-32.01 | 7.39-15.27 | 0.05-0.22 | 0.65-3.70 | 0.25-2.96 | 0.16-25.28 | 0.68-2.88 | 0.71-1.44 | 0.15-0.83 | 1.05- 2.91 |

0.35- 0.82 |

11.42- 37.04 |

26.95- 96.35 |

20.82-93.92 | 0.44-3.76 | 38.75-95.87 | 21.72- 72.67 |

35.12- 57.04 |

| Avg., | 34.24 | 23.59 | 11.84 | 0.12 | 1.69 | 0.68 | 2.82 | 1.18 | 1.11 | 0.45 | 1.45 | 0.50 | 21.22 | 86.10 | 79.69 | 0.97 | 85.84 | 58.07 | 50.57 | |

| STD (±) | 2.94 | 4.48 | 2.12 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.59 | 7.22 | 0.57 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 6.72 | 19.04 | 20.61 | 0.78 | 15.74 | 12.61 | 5.61 | |

| Karnataka (20) | Range | 37.88-52.33 | 18.09-21.88 | 6.32-17.33 | 0.02-0.34 | 0.29-2.76 | 0.11-0.85 | 0.06-1.04 | 0.51-1.64 | 0.89-1.80 | 0.10-0.40 | 1.91- 2.54 |

0.31- 0.95 |

11.73- 20.38 |

84.49-96.60 | 76.90-94.35 | 0.51-1.24 | 83.14-97.07 | 48.16-71.78 | 33.94-48.13 |

| Avg., | 43.12 | 19.43 | 12.39 | 0.08 | 1.18 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 1.09 | 1.23 | 0.26 | 2.22 | 0.64 | 16.35 | 90.87 | 85.76 | 0.87 | 91.08 | 58.00 | 42.52 | |

| STD (±) | 3.86 | 1.03 | 2.86 | 0.07 | 0.61 | 0.20 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 2.79 | 2.86 | 4.22 | 0.19 | 3.27 | 6.13 | 3.66 | |

| Goa (11) | Range | 36.14-43.11 | 15.61-21.66 | 9.67-17.71 | 0.04-0.58 | 1.21-3.87 | 0.29-1.33 | 0.56-8.40 | 1.28-1.63 | 1.01-1.97 | 0.17-0.49 | 1.82- 2.57 |

0.50- 1.13 |

9.23- 15.94 |

61.49-88.35 | 55.96-81.79 | 0.83-1.61 | 70.30-90.49 | 41.30-59.13 | 40.61-47.97 |

| Avg., | 40.06 | 18.05 | 13.20 | 0.16 | 2.45 | 0.72 | 2.33 | 1.49 | 1.36 | 0.32 | 2.24 | 0.74 | 13.71 | 80.97 | 74.25 | 1.21 | 82.19 | 49.21 | 43.81 | |

| STD (±) | 2.27 | 1.95 | 2.01 | 0.17 | 0.73 | 0.33 | 2.57 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 2.03 | 8.52 | 7.99 | 0.24 | 6.06 | 5.43 | 2.68 | |

| Archean- Proterozoic Terrain (APT) | Range | 29.01-52.33 | 11.37-32.01 | 6.32-17.71 | 0.04-0.58 | 0.65-3.87 | 0.11-2.96 | 0.06-25.28 | 0.51-2.88 | 0.71-1.97 | 0.10-0.83 | 1.05-2.91 | 0.31-1.13 | 9.23-37.04 | 26.95-96.60 | 20.82-94.35 | 0.44-3.76 | 38.75-97.07 | 21.72-72.67 | 33.94-57.04 |

| Avg., | 38.89 | 20.82 | 12.34 | 0.11 | 1.65 | 0.59 | 1.80 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 0.35 | 1.95 | 0.61 | 18.10 | 85.98 | 79.90 | 1.01 | 86.37 | 55.09 | 45.63 | |

| STD (±) | 5.11 | 3.82 | 2.42 | 0.10 | 0.85 | 0.44 | 4.79 | 0.44 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 5.77 | 10.14 | 10.94 | 0.40 | 8.35 | 7.10 | 5.97 | |

| Maharashtra (21) | Range | 28.32-51.21 | 13.71-21.65 | 3.13-14.67 | 0.07-0.44 | 0.79-5.72 | 0.26-2.10 | 0.12-13.22 | 0.55-1.34 | 0.63-2.98 | 0.06-0.54 | 1.87- 3.32 |

0.14- 0.88 |

7.27- 29.27 |

48.67-94.06 | 45.86-91.36 | 0.42-2.13 | 61.96-93.91 | 34.01-79.08 | 31.52-47.59 |

| Avg., | 42.28 | 16.90 | 10.75 | 0.18 | 2.23 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 0.91 | 1.51 | 0.25 | 2.54 | 0.65 | 11.98 | 85.19 | 80.59 | 1.08 | 84.23 | 53.51 | 39.66 | |

| STD (±) | 4.74 | 2.28 | 2.51 | 0.10 | 1.20 | 0.53 | 2.79 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.10 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 4.33 | 9.25 | 9.28 | 0.34 | 7.09 | 9.06 | 4.13 | |

| Gujarat (17) | Range | 42.88-50.36 | 13.04-16.24 | 6.13-10.57 | 0.10-0.24 | 2.51-4.29 | 1.65-6.38 | 0.18-1.31 | 0.66-1.83 | 0.99-2.20 | 0.11-0.36 | 2.71- 3.77 |

0.38- 0.76 |

7.38- 16.10 |

61.78-84.19 | 53.70-80.76 | 0.87-1.65 | 63.94-82.35 | 39.99-58.96 | 30.16-37.18 |

| Avg., | 47.35 | 14.43 | 8.91 | 0.15 | 3.39 | 3.05 | 0.54 | 1.29 | 1.44 | 0.17 | 3.29 | 0.62 | 10.39 | 75.02 | 68.39 | 1.31 | 74.02 | 47.15 | 33.05 | |

| STD (±) | 2.49 | 0.85 | 1.09 | 0.030 | 0.48 | 1.05 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 2.05 | 5.42 | 6.70 | 0.17 | 4.32 | 4.10 | 2.10 | |

| Deccan Trap Terrain (DTT) | Range | 28.32-51.21 | 13.04-21.65 | 3.13-14.67 | 0.07-0.44 | 0.79-5.72 | 0.26-6.38 | 0.12-13.22 | 0.55-1.83 | 0.63-2.98 | 0.06-0.54 | 1.87-3.77 | 0.14-0.88 | 7.27-29.27 | 48.67-94.06 | 45.86-91.36 | 0.42-2.13 | 61.96-93.91 | 34.01-79.08 | 30.16-47.59 |

| Avg., | 44.55 | 15.79 | 9.93 | 0.17 | 2.75 | 1.96 | 0.84 | 1.08 | 1.48 | 0.21 | 2.88 | 0.64 | 11.27 | 80.10 | 74.49 | 1.19 | 79.12 | 50.33 | 36.35 | |

| STD (±) | 4.63 | 2.16 | 2.19 | 0.08 | 1.11 | 1.28 | 2.08 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.53 | 0.14 | 3.55 | 7.33 | 7.99 | 0.25 | 5.70 | 5.12 | 3.11 | |

| West Coast of India River Average Clay (WCIRAC) | Range | 28.32-52.33 | 11.37-32.01 | 3.13-17.71 | 0.65-5.72 | 0.11-6.38 | 0.06-25.28 | 0.51-2.88 | 0.01-2.98 | 0.04-0.58 | 0.06-0.83 | 1.05-3.77 |

0.14- 1.13 |

7.26-37.05 | 26.95-96.60 | 20.82-94.35 | 0.42-3.76 | 38.75-97.07 | 21.72-79.08 | 30.16-48.13 |

| Avg., | 41.41 | 18.69 | 11.32 | 2.20 | 1.27 | 1.32 | 1.15 | 1.32 | 0.13 | 0.29 |

2.34 |

0.63 |

15.21 |

83.63 |

78.98 | 1.06 | 83.94 | 54.12 | 41.92 | |

| STD (±) | 3.26 | 4.06 | 2.60 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 3.43 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.14 |

0.31 |

0.14 |

5.98 |

9.01 |

12.87 | 0.47 | 10.40 | 9.51 | 2.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).