1. Introduction

Plants of the genus

Ajuga are not officially recognized in main pharmacopoeias but are widely used in traditional medicine across many countries. According to the World Flora, the genus

Ajuga in the Lamiaceae family includes approximately 300 species, of which 91 species are recognized as independent taxa, 192 have synonymous names, and 10 species remain undefined [

1]. The International Plant Names Index lists 261 species of the genus

Ajuga [

2]. The Ukrainian Plant Name Reference includes 10 species of the genus

Ajuga [

3]. Nine species of this genus grow in Ukraine, the most common being

Ajuga reptans L.,

A. genevensis L., and

A. laxmannii (Murray) Benth.

The aerial parts of

Ajuga plants contain various biologically active substances (BAS), including flavonoids, hydroxycinnamic acids, essential oils, alkaloids, tannins, organic acids, and others [

4,

5]. The chemical composition of

A. reptans is relatively understudied. The quantitative composition and antioxidant activity of ethanolic extracts from the root and leaves of

A. reptans were caried out. The dominant compounds in both extracts were verbacoside, isoverbacoside, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid and rosmarinic acid [

6].

A. reptans raw materials also contains volatile oils, iridoids (such as 8-O-acetyl-harpagide) [

7,

8], flavonoids (including isoquercitrin) [

9], tannins, and traces of alkaloids [

10,

11]. Phytoecdysteroids have also been isolated from

A. reptans, including 20-hydroxyecdysone, 29-norcyasterone, 5,20-dihydroexidizone, sengosterone, ajugalactone, and ajugosterone [

12,

13]. The herb also contains macro- and microelements [

14] as well as fatty acids [

15].

Species of the genus

Ajuga are widely used in traditional medicine. These plants are recognized for their diaphoretic, antiseptic, hemostatic, and anti-inflammatory properties [

5,

16]. Most species of this genus are used to treat viral diseases, colds, rheumatism, stomach diseases, and gallstone disease [

17]. Some species are also used in the treatment of malaria and oncology [

18,

19,

20,

21]. The herb of

A. reptans is used in traditional Austrian medicine as a tea to treat respiratory disorders [

22]. In traditional Bulgarian medicine, the plant is regarded as a remedy that enhances metabolism and is also used for gastrointestinal diseases [

23]. In Polish folk medicine,

A. reptans is used for its laxative, analgesic, and astringent properties and is known for its anti-edematous, anti-hemorrhagic, and anti-inflammatory effects [

24].

A. reptans extracts demonstrated antiproliferative potential against prostate and lung cancer cells [

9].

A. reptans is cultivated in the Botanical Garden of the renowned cosmetic brand Yves Rocher as a plant that enriches the "Vegetal" lifting line. In 1959, Yves Rocher's plant cosmetics experts studied

A. reptans and discovered its high collagen content, which has a pronounced lifting effect. The company’s scientists successfully extracted and patented a collagen concentrate, subsequently developing a new facial care line that restores skin structure using a biotechnological process [

25]. Additionally, the phenylpropanoid glycoside from

A. reptans has been used to create a composition for the prevention and treatment of androgenic alopecia and telogen effluvium [

26].

A. reptans extracts, positively affect the skin condition: causing an improvement in the degree of skin hydration and elasticity, reducing the skin pores size and skin hyperpigmentation, and reducing the wrinkles depth [

27].

Moreover, species of the genus

Ajuga are used as ornamental plants due to their vibrant flower colours and prolonged blooming periods. These plants are appreciated for their varied leaf shapes, textures, and colours. Ornamental varieties of

A. reptans, such as ‘Atropurpurea’, ‘Burgundy Glow’, and ‘Multicolor’, are commonly cultivated [

28].

A literature review indicates that the genus

Ajuga plants are valuable medicinal species that have been used in traditional medicine across various countries for a long time [

5,

8,

17]. Due to the beneficial therapeutic effects of

Ajuga genus, it can be considered in future preclinical and clinical studies as a source of natural antioxidants, dietary supplements in the pharmaceutical industry, and stabilizing food against oxidative deterioration [

17]. They contain a complex array of BAS and exhibit diverse pharmacological activities. However,

Ajuga species have been scarcely studied, and the available data on their distribution and medical use suggest promising opportunities for further research and the development of new medicinal products for clinical and pharmaceutical applications.

Based on the review of previous studies and the experience of using A. reptans raw material in folk medicine, it is advisable to experimentally study the antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, haemostatic, wound healing, and hepatoprotective activity of its galenic extracts obtained with water and alcohol solutions of various concentrations.

The purpose of the study was to conduct phytochemical and pharmacological research on A. reptans L. herb extracts to establish their potential for use in medical and pharmaceutical practice.

3. Discussion

Among the phenolic compounds in the

A. reptans extracts (

Table 2), 8 flavonoids were identified: rutin, quercetin, quercetin-3-glucoside, luteolin, apigenin, neohesperidin, naringin, and naringenin. Additionally, 4 tannin metabolites were identified: pyrocatechin, epicatechin, epicatechin gallate, and gallocatechin. 5 hydroxycinnamic acids were also identified: caffeic,

p-coumaric, sinapic, trans-cinnamic, and trans-ferulic acids. 3 phenol carboxylic acids were found: gallic, benzoic, and syringic acids. Quinic acid was also identified in the extracts. The predominant hydroxycinnamic acids in

A. reptans herb extracts were

p-coumaric, caffeic, and sinapic acids; among the flavonoids, rutin, quercetin, and neohesperidin were predominant; and among the tannin metabolites, epicatechin gallate and gallocatechin were the most significant. It was reported that in

A. reptans, raw materials from Turkey, caffeic and chlorogenic acids predominated among hydroxycinnamic acids and luteolin derivatives - among flavonoids [

36]. In the other research isoquercitrin and ferulic acids were dominant phenolic compounds [

8]. Thus, Ukrainian raw materials have a similar qualitative composition but differ in dominant substances.

In the analysis of steroids (

Table 3), 9 steroids were identified: stigmasterol, pregna-5,17-dien-3-ol, ergosterol, 3β-steariloxy-ers-12-ene, stigmaster-5,22-dien-3-ol acetate, β-sitosterol, olean-12-ene, 3β-methoxy-5-cholestene, and traces of cholesterol. Stigmasterol was the dominant compound. The steroid composition has been studied quite well for this genus, so the results correspond to those of previous research [

5].

As shown in

Table 3, 10 volatile compounds were identified and quantified in the

A. reptans herb extracts, including 1 ketone, 2 alcohols, and 1 terpenoid compound. The alcohols and their derivatives included 3-heptanol and a-terpineol; the ketone identified was 2-heptanone. Among sesquiterpenes and their derivatives were α-bergamotene and hexahydrofarnesyl acetone; among aliphatic sesquiterpenes was farnesene; and among terpenoids was a-linalool. The extracts also contained acyclic triterpenes such as squalene and esters like methyl linoleate and linoleic acid. Other research has shown that teupolioside, martinoside, verbascoside, and isoverbascoside are the major chemical constituents among phenylproponoids, and teupolioside is the chemical marker of the

A. reptans extract, and major monoterpenoids include three iridoid glycosides: harpagide, 8-O-acetylharpagide and reptoside [

37]. Thus, our results extend the data on the chemical composition of the volatile fraction.

The qualitative composition and quantitative content of amino acids in the extracts of

A. reptans herb were studied for the first time. The 17 identified amino acids included 10 monoaminomonocarboxylic acids: alanine, valine, glycine, isoleucine, leucine, methionine, serine, threonine, phenylalanine, and cysteine; 2 monoaminodicarboxylic acids: aspartic and glutamic acids; 2 diamino monocarboxylic acids: arginine and lysine; and 2 heterocyclic amino acids: histidine and tryptophan. According to experimental research data (

Table 4), glutamic acid, aspartic acid, arginine, leucine, serine, valine, and glycine predominated in

A. reptans herb extracts.

The soft extracts of

A. reptans herb are classified as practically non-toxic (toxicity class V) when administered intragastrically (LD

50 > 5000 mg/kg) according to the classification by K.K. Sidorov [

34].

The simultaneous administration of the extracts and the hepatotoxic poison led to a reduction (

Table 5) in the content of TBA-reactive substances by 1.58, 1.56, and 1.55 times, respectively, and a decrease in ALT activity by 1.52, 1.32, and 1.25 times in the blood serum of the experimental animals and by 1.88, 2.11, and 1.87 times, respectively, in the liver homogenate compared to the control group of animals. The results obtained from the conducted studies indicate that the

A. reptans herb soft extracts exhibit a pronounced hepatoprotective activity in cases of acute toxic liver damage by suppressing peroxide destructive processes and reducing the development of cytolysis syndrome, and they are practically not inferior to the hepatoprotective action of the comparison drug "Silibor." The hepatoprotective activity of

A. reptans herb extracts has been studied for the first time.

The study results (

Table 6) show that the anti-exudative activity of AR1, AR3 extracts, and quercetin gradually manifested and reached its maximum within 4 hours from the start of the experiment, indicating a moderate effect of these substances. The anti-inflammatory effect is minor and has no pharmacological significance, as a level of pharmacological activity of at least 20% is considered significant for the experimental study of anti-inflammatory agents [

38]. The activity of the AR2 extract increased within 2 hours during the release period of early inflammation mediators (kinin and histamine), confirming the presence of identified polyphenolic compounds with antihistaminic and polyoxygenase activity. The results indicate that, after 2 hours, the AR2 extract exceeded the anti-exudative effect of the reference drug quercetin by more than 1.2 times and maintained this effect for 2 hours. The effect of diclofenac sodium manifested immediately, increased significantly within 2 hours, and reached its maximum 4 hours after the start of the experiment, indicating significant inhibition of all groups of inflammation mediators. In the control group of untreated animals, oedema increased within 4 hours. The study of the anti-inflammatory activity of the tested extracts established that the AR2 extract at a dose of 50 mg/kg exceeded the anti-exudative effect of the reference drug quercetin (anti-exudative effect – 20.52%) after 2 hours. Previously

in vivo and

in vitro studies have shown that the representatives of

Ajuga L. genus inhibit inflammatory responses by suppressing inflammatory factors (cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), nitric oxide (NO), interleukin 8 (IL-8), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [

5,

39]. Such data is available for some

Ajuga species but lacks them for

A. reptans. The best anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory activity was observed for

the A. reptans 100 mg dw/mL extract when compared with diclofenac [

8], but in our research the effective therapeutic dose was 50 mg/kg.

The obtained results (

Table 7) indicate that the local application of

A. reptans extracts (using a gauze pad soaked in the tested extracts directly on the wound surface immediately after the wound was made), significantly decreased bleeding time compared to the control group of animals. The most significant reduction in bleeding was caused by applying the AR1 extract, reducing bleeding time by 40.59%, while the hemostatic activity of the "Rotokan" preparation reduced it by 52.61% compared to the control group. Our conducted studies indicate that

A. reptans extracts have a local hemostatic effect. The study's results on the dynamics of the wound healing process with the application of

A. reptans extracts (

Table 8) show that from the 9th day of the local application of the AR2 extract and the comparison drug "Rotokan," complete wound healing occurred. There was no scientific conformation of the hemostatic and wound healing activity of

A. reptans extracts, although, in folk medicine, it is commonly recommended in these cases [

5,

16,

40].

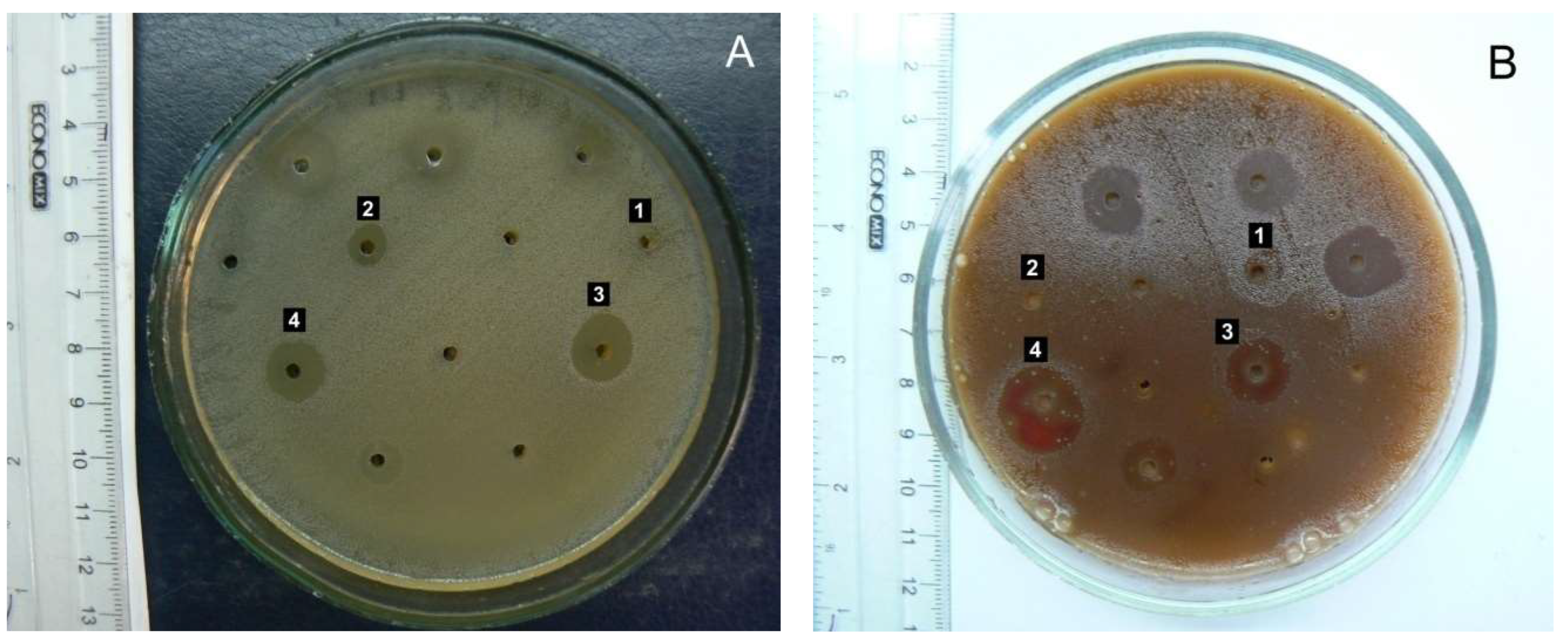

The conducted studies established that A. reptans herb extracts can inhibit the growth of microorganisms to varying degrees, depending on the ethanol concentration used as an extraction agent.

The AR3 herb extract (extraction agent: 70% ethanol) caused significant inhibition of the growth of pathogenic β-hemolytic streptococci of groups A and G – causative agents of tonsillitis and angina (

Figure 3), as well as β-hemolytic streptococcus group B – a causative agent of inflammatory processes in the female external genital organs. Conditionally pathogenic α-hemolytic streptococci of the oral microflora,

St. oralis,

St. sanguinis, and

St. gordonii (which can cause purulent-inflammatory processes of the oral mucosa and periodontal tissues in dental practice), also showed high sensitivity to the AR3 extract. The growth of

S. sanguinis and

St. oralis was also notably inhibited by the AR2 extract. Regarding the primary causative agent of bacterial respiratory infections (bronchitis, otitis, sinusitis), pneumococcus

St. pneumonia, the AR2 and AR3 extracts exhibited a bacteriostatic effect. Therefore, it can be suggested that

A. reptans herb extracts have potential use in treating streptococcal infections in dental, pediatric, and ENT practices.

Enterococcus faecalis, a common causative agent of urological and wound infections, demonstrated quite high sensitivity to AR3. This result deserves special attention due to enterococcus's high natural resistance to most antibiotic groups.

The most common causative agents of purulent-inflammatory processes, staphylococci, were significantly less sensitive to A. reptans herb extracts than streptococci. S. aureus and S. haemolyticus exhibited weak sensitivity to all tested preparations.

Gram-negative bacteria generally showed significantly lower sensitivity to the BAS of A. reptans extracts. Normal E. coli was found to be completely insensitive to them. However, there was a tendency for AR3 to inhibit the growth of E. fergusonii, which has reduced enzymatic activity, as well as Citrobacter and representatives of the putrefactive intestinal microflora Providencia and Morganella. Therefore, the inclusion of A. reptans herb as an auxiliary component can be considered when developing herbal mixtures and complex herbal remedies for treating mild forms of intestinal dysbiosis.

The antibacterial effects of the essential oil isolated from the aerial part of

A. pseudoiva have been tested before against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in vitro, including

B. subtilis,

B. cereus,

S. aureus,

E. coli,

E. faecalis,

K. pneumonia,

P. aeruginosa,

S. typhimurium,

L. monocytogenes, and

E. faecium [

5,

41]. The ethanol and methanol extracts from the aerial parts of

A. laxmannii have been shown to exhibit antibacterial activity against

P. aeruginosa,

L. monocytogenes,

E. coli, and

S. typhimurium [

8]. Thus, the results of the antibacterial effects of

A. reptans herb extracts provide new knowledges.

The

A. reptans herb extracts showed weak fungistatic activity against most types of

Candida yeast-like fungi. Previously, it was also shown that

A. reptans extracts are active against Canada spp. and

E. coli [

36,

37].

During the conducted studies, an important pattern was established: the antimicrobial activity of A. reptans herb extracts increases proportionally with the increase in ethanol concentration in the extracting solution. This may indicate the predominantly hydrophobic properties of BAS provide the antimicrobial activity of the extracts.

The study has some limitations. The sample of Ajuga reptans we used was collected only from one growing locality. We presented the phytochemical characterisation of the sample, but the concentration of bioactive substances is less or more different due to environmental factors and possible chemotypes. In future studies, it may be more adequate to analyse a mixture of herbal samples collected from several localities. Also, the other extraction solvents excluding water, 50% and 70% ethanol, and methods affect the phytochemical composition and pharmacological activity of the extracts to some extent. The authors hope that our study will provide a significant basis for A. reptans investigations in the future, using additional plant material, methods, and activities.

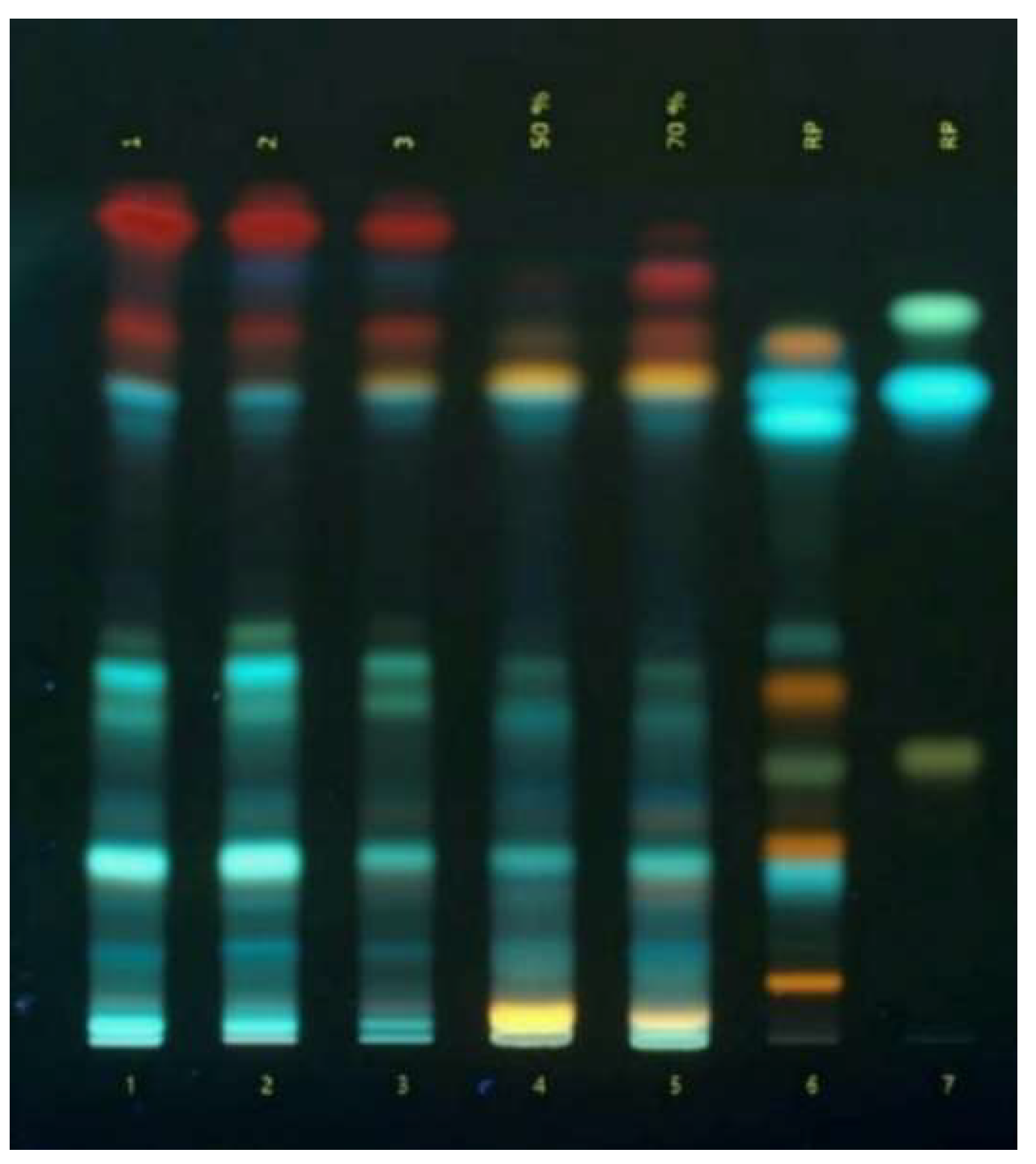

Figure 1.

TLC-chromatogram of phenolic compounds in Ajuga reptans L. herb extracts: 1 - 3 – extracts of A. reptans; 4 – A. reptans extract (extraction agent: 50% ethanol); 5 – A. reptans extract (extraction agent: 70% ethanol); 6 – comparison solution (rutin, caffeic acid, quercetin, apigenin-7-glucoside, isoquercitrin, hyperoside, chlorogenic acid, luteolin, apigenin); 7 – comparison solution (apigenin, ferulic acid).

Figure 1.

TLC-chromatogram of phenolic compounds in Ajuga reptans L. herb extracts: 1 - 3 – extracts of A. reptans; 4 – A. reptans extract (extraction agent: 50% ethanol); 5 – A. reptans extract (extraction agent: 70% ethanol); 6 – comparison solution (rutin, caffeic acid, quercetin, apigenin-7-glucoside, isoquercitrin, hyperoside, chlorogenic acid, luteolin, apigenin); 7 – comparison solution (apigenin, ferulic acid).

Figure 2.

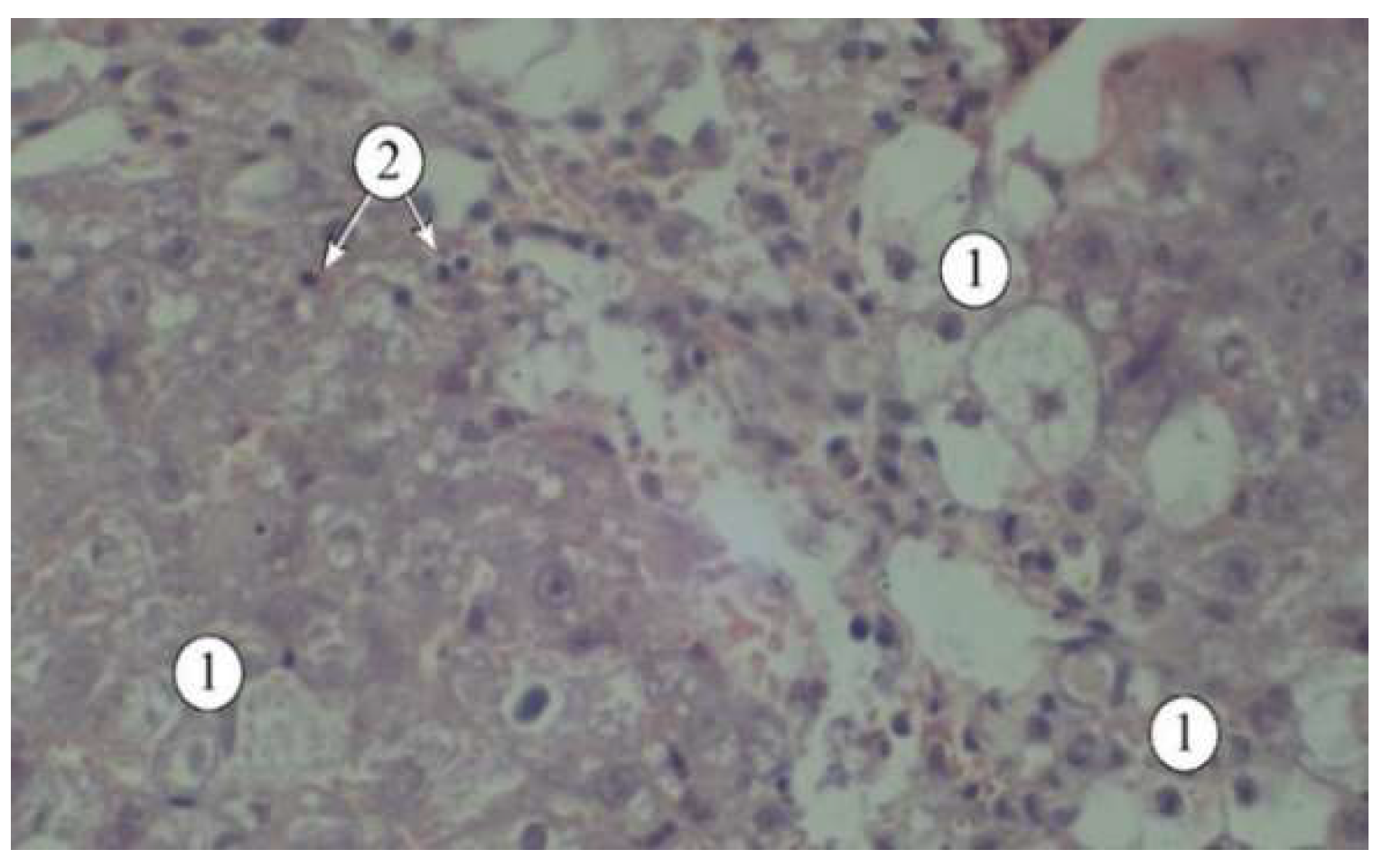

Structural features of liver lobules under the influence of the toxicant. 1 – destructured hepatocytes, 2 – lymphocytes. Staining: hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification: ×200.

Figure 2.

Structural features of liver lobules under the influence of the toxicant. 1 – destructured hepatocytes, 2 – lymphocytes. Staining: hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification: ×200.

Figure 3.

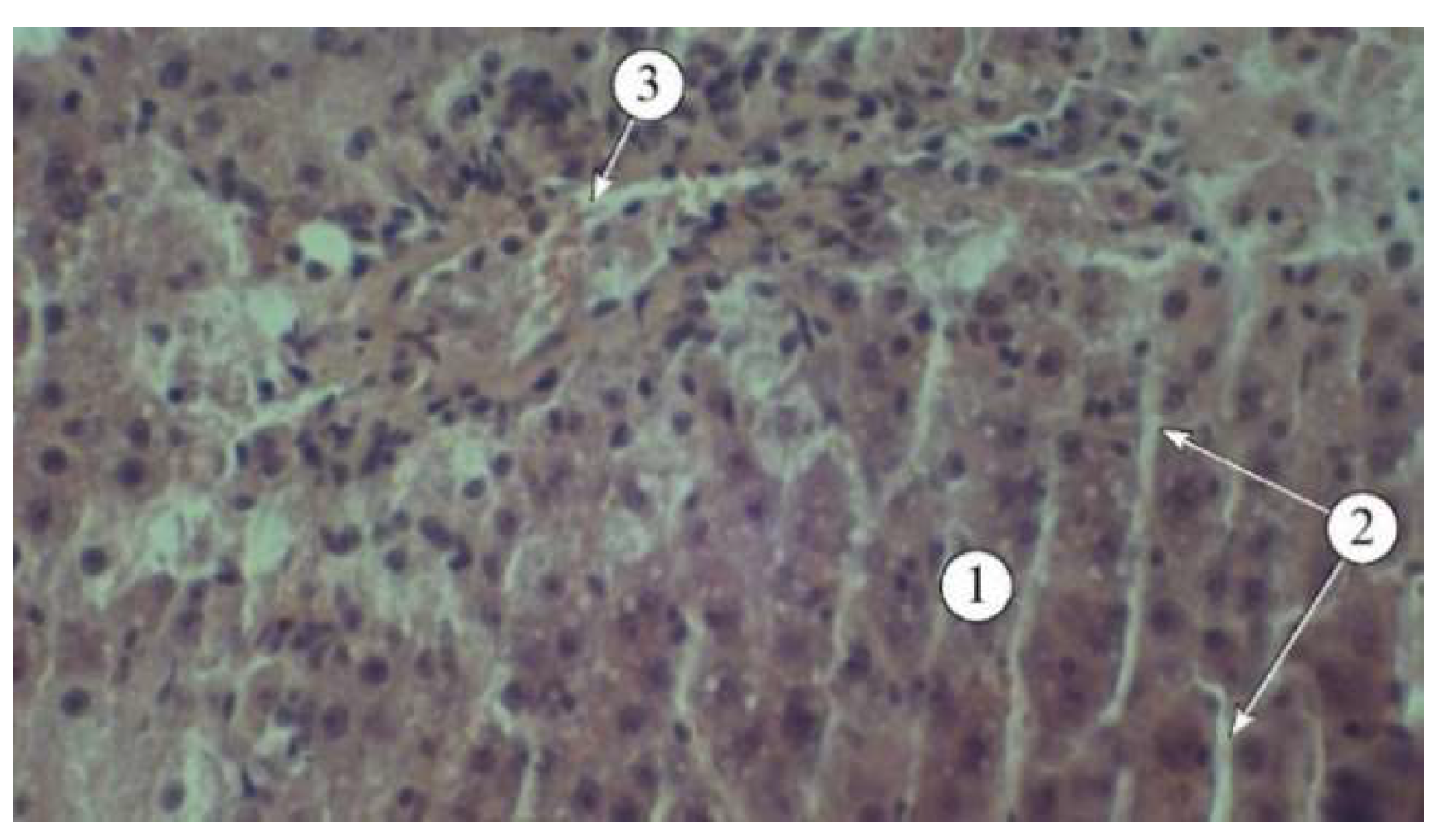

Structural features of liver lobules in animals administered AR2: 1 – hepatic plates, 2 – sinusoids, 3 – blood vessels. Staining: hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification: ×200.

Figure 3.

Structural features of liver lobules in animals administered AR2: 1 – hepatic plates, 2 – sinusoids, 3 – blood vessels. Staining: hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification: ×200.

Figure 4.

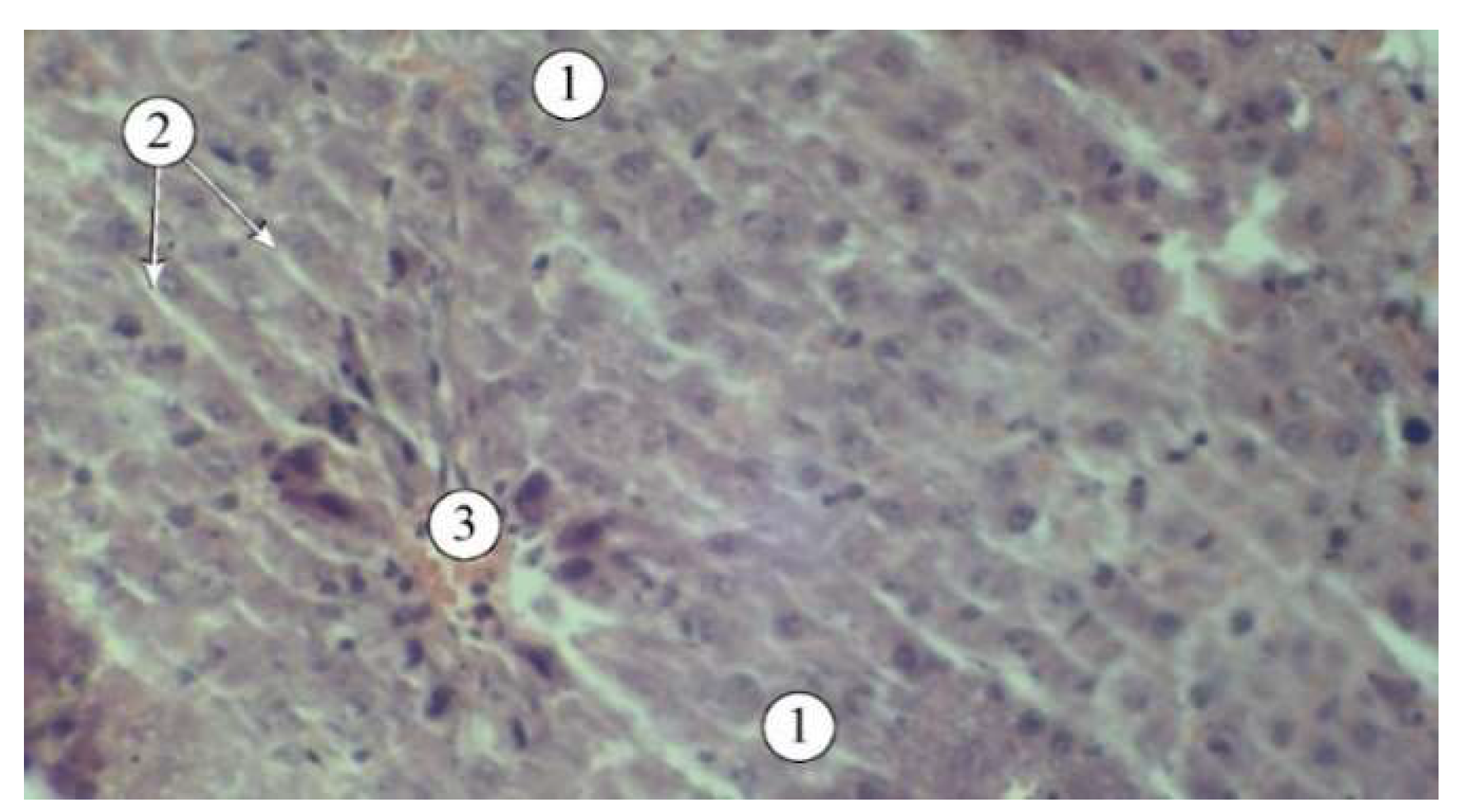

Structural features of liver lobules in animals that received the "Silibor" preparation. 1 – hepatic plates, 2 – sinusoid, 3 – central vein. Staining: hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification: ×200.

Figure 4.

Structural features of liver lobules in animals that received the "Silibor" preparation. 1 – hepatic plates, 2 – sinusoid, 3 – central vein. Staining: hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification: ×200.

Figure 5.

Antimicrobial activity of Ajuga reptans L. herb extracts prepared using AR1 (extraction agent: purified water), AR2 (extraction agent: 50% ethanol), and AR3 (extraction agent: 70% ethanol) against cultures of Enterococcus faecalis (A) and β-hemolytic Streptococcus group G (B).

Figure 5.

Antimicrobial activity of Ajuga reptans L. herb extracts prepared using AR1 (extraction agent: purified water), AR2 (extraction agent: 50% ethanol), and AR3 (extraction agent: 70% ethanol) against cultures of Enterococcus faecalis (A) and β-hemolytic Streptococcus group G (B).

Table 1.

Results of biologically active substances identification in the extracts of Ajuga reptans L. herb

Table 1.

Results of biologically active substances identification in the extracts of Ajuga reptans L. herb

| BAS group |

Reagent |

Analytical effect |

Observations in extracts |

| AR1 |

AR2 |

AR3 |

| Iridoids |

Trim Hill's reagent |

light blue color |

det |

det |

det |

| Flavanoids |

Cyanidine test |

pink color |

det |

det |

det |

| Folin-Denis reagent |

purple-blue color |

det |

det |

det |

| Tannins |

1% solution of gelatin and 10% solution of hydrochloric acid |

amorphous sediment |

det |

det |

det |

| Ferroammonium alums |

black-greenish color |

det |

det |

det |

| 10% solution of lead (II) acetate in acetic acid |

white sediment |

det |

det |

det |

| Coumarins |

Lactone test |

yellow color, white sediment |

det |

det |

det |

| Diazo reagent in an alkaline environment |

brown-red color |

det |

det |

det |

| Saponins |

Foaming reaction |

formation of stable foam |

det |

det |

det |

| Fontan-Cadell reaction |

the height of the foam in the test tubes is the same |

det |

det |

det |

| Amino acids |

0.1% ninhydrin solution |

blue-violet color |

det |

det |

det |

Table 2.

The content of biologically active substances in the extracts of Ajuga reptans L. herb

Table 2.

The content of biologically active substances in the extracts of Ajuga reptans L. herb

| № |

Name of Identified Compound |

Quantitative Content, mg/100 g |

| AR1 |

AR2 |

AR3 |

| Carboxylic Acid |

| 1 |

Quinic acid |

146.31± 4.12 |

158.87 ± 9.43 |

149.14 ± 11.76 |

| Phenolic Acids |

| 2 |

Gallic acid |

48.03 ± 2.33 |

68.44 ± 4.54 |

83,23 ± 6.52 |

| 3 |

Benzoic acid |

102.22 ± 7.09 |

168.59 ± 11.29 |

184.82 ± 9.07 |

| 4 |

Syringic acid |

27.28 ± 1.62 |

33.22 ± 1.58 |

41.96 ± 2.01 |

| Hydroxycinnamic Acids |

| 5 |

Caffeic acid |

326.48 ± 12.17 |

343.60 ± 31.99 |

311.62 ± 23.07 |

| 6 |

p- Coumaric acid |

420.62 ± 23.22 |

432.63 ± 28.32 |

376.96 ± 31.44 |

| 7 |

trans-Ferulic acid |

79.96 ± 5.13 |

87.22 ± 5.65 |

64.74 ± 2.12 |

| 8 |

Sinapic acid |

261.56 ± 21.12 |

284.43 ± 21.45 |

398.23 ± 27.87 |

| 9 |

trans- Cinnamic acid |

113.87 ± 5.08 |

126.27 ± 7.67 |

107.34 ± 12.61 |

| Flavonoids |

| 10 |

Rutin |

2384.71 ± 207.87 |

3465.43 ± 167.34 |

3256.74 ± 267.21 |

| 11 |

Quercetin-3-glucoside |

166.52 ± 6.14 |

173.25 ± 23.45 |

208.45 ± 26.32 |

| 12 |

Naringin |

146.97± 5.18 |

156.43 ± 9.23 |

187.97 ± 20.02 |

| 13 |

Neohesperidin |

330.67 ± 12.16 |

374.28 ± 27.65 |

401.27 ± 31.89 |

| 14 |

Quercetin |

1325.53 ± 115.54 |

1453.22 ± 117.39 |

1543.64 ± 107.86 |

| 15 |

Luteolin |

312.32 ± 21.62 |

341.57 ± 25.02 |

376.54 ± 28.51 |

| 16 |

Apigenin |

117.85 ± 7.02 |

134.67 ± 8.48 |

153.75 ± 18.84 |

| 17 |

Naringenin |

100.51 ± 4.89 |

112.92 ± 10.12 |

132.83 ± 10.08 |

| Tannin Metabolites |

| 18 |

Pyrocatechin |

53.44 ± 2.45 |

65.21 ± 8.55 |

77.15 ± 4.45 |

| 19 |

Epicatechin |

395.93 ± 30.34 |

356.78 ± 12.68 |

401.48 ± 36.33 |

| 20 |

Epicatechin gallate |

1295.58 ± 108.32 |

1129.42 ± 159.56 |

1209.21 ± 143.67 |

| 21 |

Gallocatechin |

1079.72 ± 76.28 |

985.46 ± 76.09 |

1067.53 ± 109.78 |

| Group content, % |

| Vitamin K1 (spectrophotometry) |

0.73 ± 0.02 |

0.81 ± 0.04 |

0.95 ± 0.07 |

| Organic acids (titrimetry) |

2.29 ± 0.05 |

2.03 ± 0.04 |

1.89 ± 0.04 |

| Ascorbic acid (titrimetry) |

0.13 ± 0.01 |

0.09 ± 0.02 |

0.08 ± 0.01 |

| Total polyphenols (spectrophotometry) |

14.25 ± 0.74 |

15.11 ± 0.57 |

15.41 ± 0.82 |

| Total tannins (spectrophotometry) |

3.72 ± 0.30 |

3.08 ± 0.31 |

2.81 ± 0.21 |

| Total flavonoids (spectrophotometry) |

5.37 ± 0.76 |

6.93 ± 0.48 |

7.07 ± 0.71 |

| Total hydroxycinnamic acids (spectrophotometry) |

5.58 ± 0.07 |

5.91 ± 0.09 |

5.80 ± 0.03 |

Table 3.

The content of volatile substances and phytosterols in the extracts of Ajuga reptans L. herb.

Table 3.

The content of volatile substances and phytosterols in the extracts of Ajuga reptans L. herb.

| Substance Name |

Class |

Content, mg/kg |

| AR2 |

AR3 |

| 2-Heptanone |

Ketones |

11.56 |

13.43 |

| 3- Heptanol |

Alcohols |

4.49 |

5.78 |

| α- Linalool |

Terpenoids |

13.30 |

17.83 |

| α- Terpineol |

Monoterpenic alcohols |

9.36 |

10.12 |

| Farnesene |

Aliphatic sesquiterpenes |

7.90 |

9.33 |

| Hexahydrofarnesyl acetone |

Sesquiterpene derivatives |

83.55 |

96.32 |

| α- Bergamotene |

Sesquiterpenes |

6.83 |

9.71 |

| Linoleic acid |

Esters |

77.19 |

68.23 |

| Methyl linoleate |

Esters |

138.97 |

141.52 |

| Squalene |

Acyclic triterpene |

15.38 |

21.83 |

| Ergosterol |

Sterol |

281.69 |

298.43 |

| Isocholesterol |

Sterol |

74.10 |

76.32 |

| Pregna-5,17-dien-3-ol |

Sterol |

843.91 |

903.08 |

| Stigmasterol |

Sterol |

1546.20 |

1789.34 |

| β- Sitosterol |

Sterol |

144.07 |

153.59 |

| Olean-12-en |

Sterol |

133.07 |

139.12 |

| 3β-stearyloxy-ers-12-en |

Sterol |

272.86 |

307.32 |

| Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol acetate |

Sterol |

196.06 |

203.45 |

Table 4.

Amino acid content in the extracts of Ajuga reptans L. herb.

Table 4.

Amino acid content in the extracts of Ajuga reptans L. herb.

| Amino Acid |

Chemical Formula |

Content of Free Amino Acids, мг/100 г |

|

| AR1 |

AR2 |

AR3 |

|

| Monoaminomonocarboxylic |

|

| Alanine |

C3H7O2N |

14.03± 0.07 |

11.83± 0.09 |

10,98± 0,08 |

|

| Valine |

C5H11O2N |

12.67± 0.07 |

14.67± 0.07 |

16,82± 0,04 |

|

| Glycine |

C2H5O2N |

15.45± 0.15 |

13.81±0.06 |

12,89± 0,11 |

|

| Isoleucine |

C6H13O2N |

11.93± 0.06 |

11.64±0.03 |

10,81± 0,10 |

|

| Leucine |

C6H13O2N |

19.73± 0.17 |

18.21±0.02 |

17,88± 0,07 |

|

| Methionine |

C5H11O2NS |

9.07± 0.06 |

7.23±0.03 |

7,82± 0,12 |

|

| Serine |

C3H7O3N |

19.03± 0.14 |

17.13±0.11 |

17,86± 0,16 |

|

| Threonine |

C4H9O3N |

11.04± 0.11 |

10.33±0.08 |

10,72± 0,09 |

|

| Phenylalanine |

C9H11O2N |

10.06± 0.09 |

11.81±0.06 |

13,58± 0,13 |

|

| Cysteine |

C6H12N2O4S2 |

3.82± 0.07 |

4.11±0.07 |

4,67± 0,07 |

|

| Total |

126.83 |

120.77 |

124.03 |

|

| Monoaminodicarboxylic |

|

| Aspartic acid |

C4H7O4N |

29.81± 0.21 |

28.93±0.13 |

26,09± 0,19 |

|

| Glutamic acid |

C5H9O4N |

49.87± 0.18 |

54.91±0.22 |

55,83± 0,15 |

| Total |

79.87 |

83.84 |

81.92 |

| Diaminomonocarboxylic |

| Arginine |

C6H14O2N |

33.76± 0.17 |

35.16±0.09 |

41,82± 0,13 |

| Lysine |

C6H14O2N |

9.53± 0.07 |

8.71±0.07 |

9,07± 0,08 |

| Total |

43.29 |

43.87 |

50.89 |

| Heterocyclic |

| Histidine |

C6H9O2N |

8.83± 0.08 |

9.64±0.06 |

9,87± 0,04 |

| Tryptophan |

C11H12N2O2 |

0.71± 0.02 |

0.93±0.02 |

0,89± 0,04 |

| Total |

9.54 |

10.57 |

10.76 |

| Overall total content |

259.53 |

259.05 |

267.60 |

Table 5.

The effect of Ajuga reptans L. extracts on the biochemical parameters of blood serum and liver condition in acute carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatitis.

Table 5.

The effect of Ajuga reptans L. extracts on the biochemical parameters of blood serum and liver condition in acute carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatitis.

| Biochemical and hematological indicators |

Research Objects |

| Silibor |

AR1 |

AR2 |

AR3 |

50% Oil Solution CCl₄ |

Intact Animals |

| Number of animals |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

| Dose, mg/0.1 kg |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

0.8 mL |

- |

| ALT, µmol/hour.ml |

3.70 ± 0.18*/** |

4.01 ± 0.19*/** |

4.61 ± 0.12*/** |

4.89 ± 0.19*/** |

6.12 ± 0.23* |

1.07 ± 0.04 |

| AST, µmol/hour.ml |

3.25 ± 0.15*/** |

2.30 ± 0.10*/** |

2.93 ± 0.11*/** |

3.83 ± 0.14*/** |

4.03 ± 0.15* |

1.13 ± 0.04 |

| TBA-reactive substances, nmol/ml |

3.45 ± 0.12*/** |

3.42 ± 0.12*/** |

3.52 ±0.17*/** |

3.50 ± 0.12*/** |

5.47 ± 0.27* |

3.27 ± 0.11 |

| Arginase, µmol/0.1 ml |

0.85 ± 0.04*/** |

0.61 ± 0.02*/** |

0.70 ± 0.03*/** |

0.68 ± 0.01*/** |

1.21 ± 0.09* |

0.58 ± 0.02 |

| Ceruloplasmin, u.o. |

25.5 ± 0.95*/** |

25.41 ± 0.98*/** |

24.89 ± 0.85*/** |

25.01 ± 0.97*/** |

19.01 ± 0.78* |

27.00 ± 0.84 |

| Liver Homogenate |

| TBA-reactive substances, µmol/g |

34.15 ± 1.23*/** |

30.35 ± 1.14*/** |

34.06 ± 1.12*/** |

34.23 ± 1.16*/** |

64.31 ± 2.98* |

27.23 ± 0.88 |

Table 6.

The effect of Ajuga reptans L. extracts on the increase in paw volume and suppression of the inflammatory response in rat limbs.

Table 6.

The effect of Ajuga reptans L. extracts on the increase in paw volume and suppression of the inflammatory response in rat limbs.

| Group№ |

Tested substance |

Dose, mg/kg |

, n=8 /

Inflammatory Response Inhibition, % |

| 1 hour |

2 hours |

4 hours |

| I |

AR1 |

100 |

43.80±0.07* |

58.43±0.04 |

82.34±0.08** |

| 2.82 |

5.8 |

9.84 |

| IІ |

AR2 |

100 |

42.88±0.04* |

56.45±0.02** |

45.52±0.03 |

| 6.8 |

15.7 |

20.52 |

| IІІ |

AR3 |

100 |

49.03±0.03 |

62.46±0.03 |

65.35±0.04 |

| 4.7 |

6.3 |

11.8 |

| IV |

Quercetin |

50 |

46.57±0.19 |

63.2±0.15 |

61.09±0.15 |

| 5.8 |

13.4 |

17.2 |

| V |

Diclofenac sodium |

8 |

39.17±0.93** |

33.60±0.05* |

35.52±0.03* |

| 17.97 |

31.54 |

45.14 |

| VІ |

Control |

- |

44.88±0.04 |

71.67±0.02 |

132.29±0.04 |

Table 7.

The effect of Ajuga reptans L. herb extracts and the reference preparation "Rotokan" on the duration of bleeding.

Table 7.

The effect of Ajuga reptans L. herb extracts and the reference preparation "Rotokan" on the duration of bleeding.

| № |

Tested Substance |

Bleeding Duration Time

,c

|

Reduction in Bleeding Time, % |

| 1 |

AR1 |

90.45 ±1.88 |

40.59 |

| 2 |

AR2 |

110.35 ±1.12 |

27.52 |

| 3 |

AR3 |

125.10 ±1.44 |

17.83 |

| 4 |

«Rotokan» |

72.15 ±1.11 |

52.61 |

| 5 |

Intact animals |

152.25 ±1.65 |

- |

Table 8.

Dynamics of the wound healing process applying on of Ajuga reptans L. herb extracts.

Table 8.

Dynamics of the wound healing process applying on of Ajuga reptans L. herb extracts.

| Experimental Animal Groups |

Determination of the wound healing area as a percentage of the total wound surface area, % |

| 3 day |

5 day |

7 day |

9 day |

14 day |

16 day |

| AR1 |

4.30 ±0.12 |

10.45 ±0.10 |

46.90 ±0.13 |

74.25 ±0.21 |

92.80 ±0.13 |

100 |

| AR2 |

7.00 ±0.16 |

25.83 ±0.13 |

62.92 ±0.14 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| AR3 |

6.75 ±0.13 |

24.75 ±0.12 |

60.44 ±0.12 |

83.63 ±0.12 |

100 |

100 |

| «Rotokan» |

7.50 ±0.12 |

28.35 ±0.12 |

69.45 ±0.17 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Intact animals |

4.20 ±0.16 |

19.15 ±0.11 |

55.25 ±0.14 |

70.14 ±0.14 |

92.24±0.11 |

100 |

Table 9.

Antimicrobial activity of the Ajuga reptans L. herb extracts.

Table 9.

Antimicrobial activity of the Ajuga reptans L. herb extracts.

| Microorganism |

Origin |

Diameters of growth inhibition zones, mm |

| Gentamicin |

Fluconazole |

Ajuga reptans L. herb extracts |

| AR1 |

AR2 |

AR3 |

| Staphylococci |

| Staphylococcus (S.) aureus |

pus from a wound |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6.36 ± 0.28 |

| S. haemolyticus |

pus from a boil |

10 |

0 |

6.58 ± 0.12 |

6.95 ± 0.46 |

5.84 ± 0.27 |

| S. epidermidis |

АТСС |

28 |

0 |

0 |

5.01 ± 0.64 |

4.48 ± 0.30 |

| Enterococci |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

urethra |

6 |

0 |

3.83 ± 0.20 |

7.29 ± 0.34* |

11.49 ± 0.61* |

| β-Hemolytic streptococci |

| Streptococcus (St.) pyogenes (GroupA) |

pharynx |

8 |

0 |

0 |

11.96 ± 0.67* |

13.99 ± 0.67* |

| St. agalacticae (Group B) |

vaginal mucus |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9.31 ± 0.49* |

| S. dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis (group G) |

pharynx |

8 |

0 |

4.39 ± 0.09 |

4.65 ± 0.26 |

12.27 ± 0.10* |

| α-Hemolytic streptococci |

| St. gordonii |

oral cavity |

6 |

0 |

4.63 ± 0.12 |

4.51 ± 0.30 |

13.24 ± 0.60* |

| St. sanguinis |

oral cavity |

6 |

0 |

0 |

11.82 ± 0.40* |

0 |

| St. oralis |

oral cavity |

6 |

0 |

[8.96 ± 0.61]* |

12.14 ± 0.34* |

12.13 ± 0.13 |

| St. pneumoniae |

mucus |

6 |

0 |

[6.37 ± 0.24]* |

[10.86 ±0.30]* |

[11.01 ±1.57]* |

| Bacilli |

| Bacillus subtilis |

АТСС 6051 |

34 |

0 |

4.07 ± 0.29 |

8.29 ± 0.48* |

4.48 ± 0.69 |

| Enterobacteria |

| Escherichia coli |

АТСС 25922 |

22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5.80 ± 0.42 |

| Escherichia fergusonii |

defecation |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3.86 ± 0.19 |

| Citrobacter freundii |

defecation |

8 |

0 |

0 |

3.89 ± 0.08 |

12.45 ± 0.50* |

| Morganella morganii |

urine |

6 |

0 |

4.07 ± 0.14 |

4.44 ± 0.35 |

5.66 ± 0.10* |

| Providencia rettgeri |

urine |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9.09 ± 0.21* |

| Providencia stuartii |

urine |

6 |

0 |

0 |

5.10 ± 0.44 |

8.61 ± 0.46* |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

АТСС 700603 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5.68 ± 0.40 |

| Pseudomonads |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

pus from a wound |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Yeast-like Fungi of the Genus Candida |

| Candida albicans |

oral cavity |

0 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

[10.36 ± 0.48] |

| C. tropicalis |

mucus |

0 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

[5.35 ± 0.63] |

| C. lusitaniae |

oral cavity |

0 |

19 |

3.92±0.16 |

5.25±0.72 |

[4.98 ± 0.55] |

| C. lipolytica |

oral cavity |

0 |

6 |

0 |

4.65±0.55 |

[5.83 ± 0.28] |

| C. kefyr |

oral cavity |

0 |

20 |

3.10 ± 0.16 |

4.38 ± 0.29 |

[9.55 ± 0.35] |