1. Introduction

Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) are multipotent clonogenic cells of mesodermal lineage. Over the past decade, MSCs have emerged as an effective tool for use in regenerative medicine and biomedical engineering due to ease of their derivation and

in vitro expansion, as well as their differentiation potential, immunomodulatory and angiogenic paracrine activity [

1,

2]. At the moment, MSCs have shown encouraging results in clinical trials, but their application has some limitations, one of which is the need for large amounts of cells required for transplantations [

3]. MSCs can be propagated by culturing, however, repeated passaging of these cells leads to the development of a replicative senescence, which is defined as a state of permanent growth arrest after a certain number of cell divisions.

To date, there is a lot of evidence that cellular senescence broadly contribute to the development of organismal aging in several aspects, such as promotion of tissue disfunction, acquisition of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), stem cell pool exhaustion [

4,

5]. That is why, the search for the causes of cellular senescence and possible approaches to prevent or reverse it is nowadays a focus of intense research [

6]. One of the most promising methods is based on the technique of reprogramming of the adult cells into a pluripotent state. Initially, cellular senescence was considered a roadblock to this process [

7]. Nevertheless, several groups soon showed that cells derived from old donors or underwent senescence after long-term cultivation can also generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), similar in their characteristics to iPSCs from young donors [

8,

9]. Subsequent differentiation of the obtained iPSCs resulted in the formation of progeny cells lacking age-associated markers, thus proving the possibility of cell rejuvenation by passing through the pluripotency stage. In 2016, Ocampo and colleagues proposed a new strategy of rejuvenation: cells and organs can be revitalized

in vivo and

ex vivo by partial reprogramming without the need for complete dedifferentiation to pluripotency [

10]. In this groundbreaking study, it was demonstrated that cyclic partial reprogramming erases the cellular markers of senescence in mouse and human cells

in vitro, as well as ameliorates the signs of aging and expands the life span of progeria mice. For reprogramming, a doxycycline-inducible cassette containing genes encoding the Yamanaka pluripotency transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc - OSKM) has been employed. Since then, a number of studies have been published both on mouse models

in vivo and on human and murine cell lines

ex vivo, confirming that partial reprogramming can be an effective rejuvenation strategy (the studies revised in [

11]). Among others, there has been evidence of rejuvenation of MSCs from aged mice. However, there is limited knowledge about this issue in human MSCs that have undergone replicative senescence in culture [

12]. Dr. Göbel and colleagues attempted to delay the onset of replicative senescence by expressing OSKM, LIN28 and shRNA for p53 in human MSCs at early passages. However, this approach did not result in the extending of cell expansion in culture or delay in the acquirement of senescence-associated phenotype [

13].

In this study, we report that application of a partial reprogramming method can ameliorate senescence-associated markers and enhance the therapeutic activity of human MSCs underwent replicative senescence after prolonged culturing.

2. Results

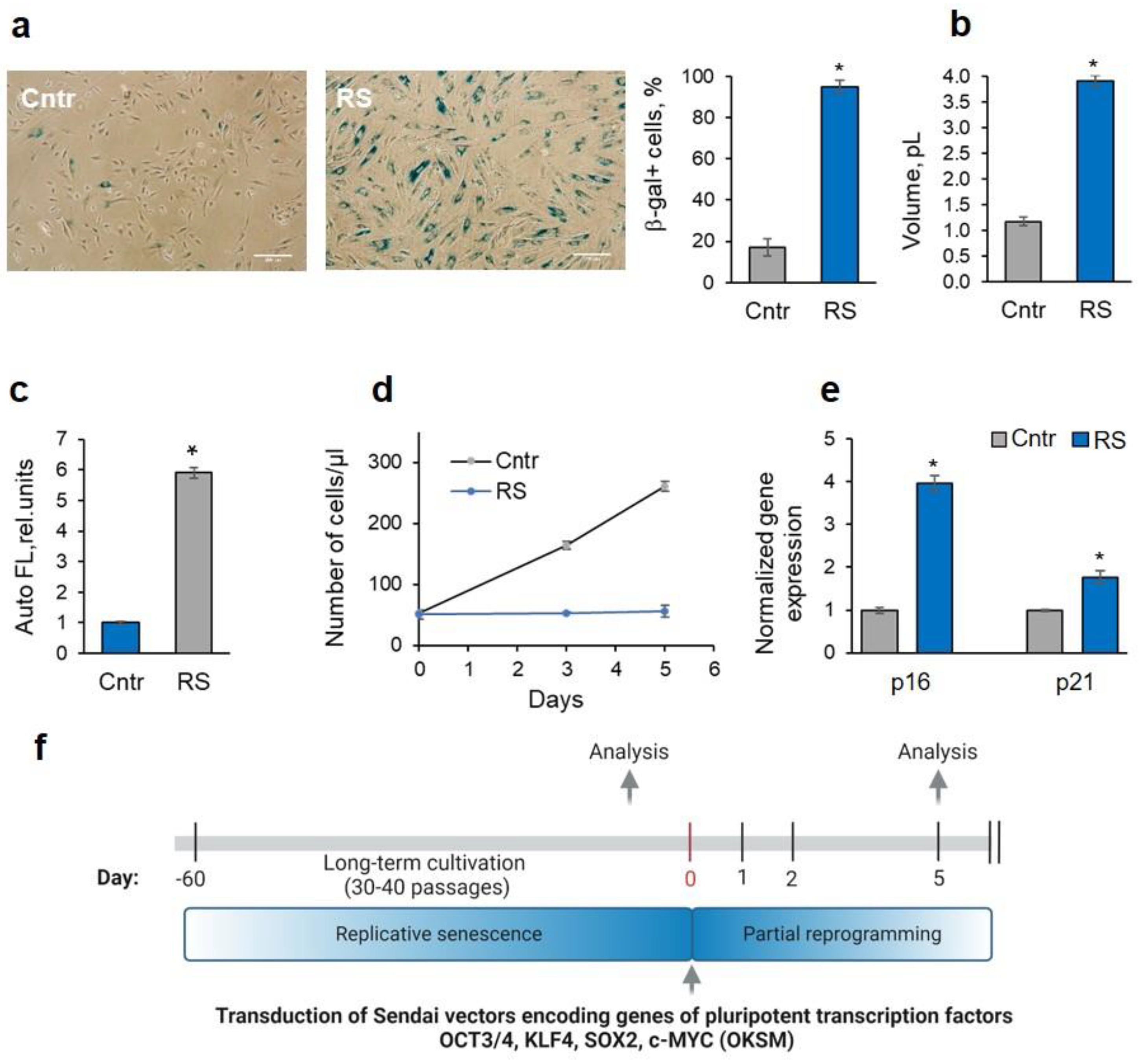

2.1. Partial Reprogramming Leads to Erasure of Replicative Senescence Markers in MSCs

For the experiments, we chose endometrial mesenchymal stem/stromal cells as an example of MSCs, because they possess all the markers and plasticity of MSCs, and, in addition, can be obtained non-invasively from menstrual blood of donors [

14], which is an important factor for their potential use in therapy. Replicative senescence was achieved by long-term cultivation of MSCs for 35-40 passages. MSCs after prolonged cultivation (RS-MSCs) demonstrated all the features of the senescence phenotype: they expressed senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-galactosidase) (

Figure 1A), enlarged their size and flattened (

Figure 1A, B), owned an enhanced autofluorescence (usually associated with the accumulation of lipofuscin in senescent cells [

15]) (

Figure 1C). RS-MSC growth curve demonstrated cell proliferation arrest (

Figure 1D). Moreover, we revealed the upregulation of genes, which code p21 and p16 cell cycle inhibitors (

Figure 1E).

In order to check whether it is possible to rejuvenate RS-MSCs by partial reprogramming, we transduced cells with Sendai vectors containing genes encoding classical Yamanaka transcription factors - Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc (CytoTune-iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kit). Despite the fact that the cassette used in this study is not inducible (in contrast to those employed in most experiments to study the phenomenon of partial reprogramming), its advantage is the high efficiency and the absence of target gene incorporation into the cellular genome, thus preserving its stability. As a mock control, we used RS-MSCs received the same handling procedures but without viral vectors. The characteristics of partially reprogrammed RS-MSCs (PR-MSCs) and RS-MSCs were compared on the 5th day after transduction with Sendai viruses (

Figure 1F), and throughout this time cells were cultured in standard DMEM/F12 full growth medium, which was changed daily.

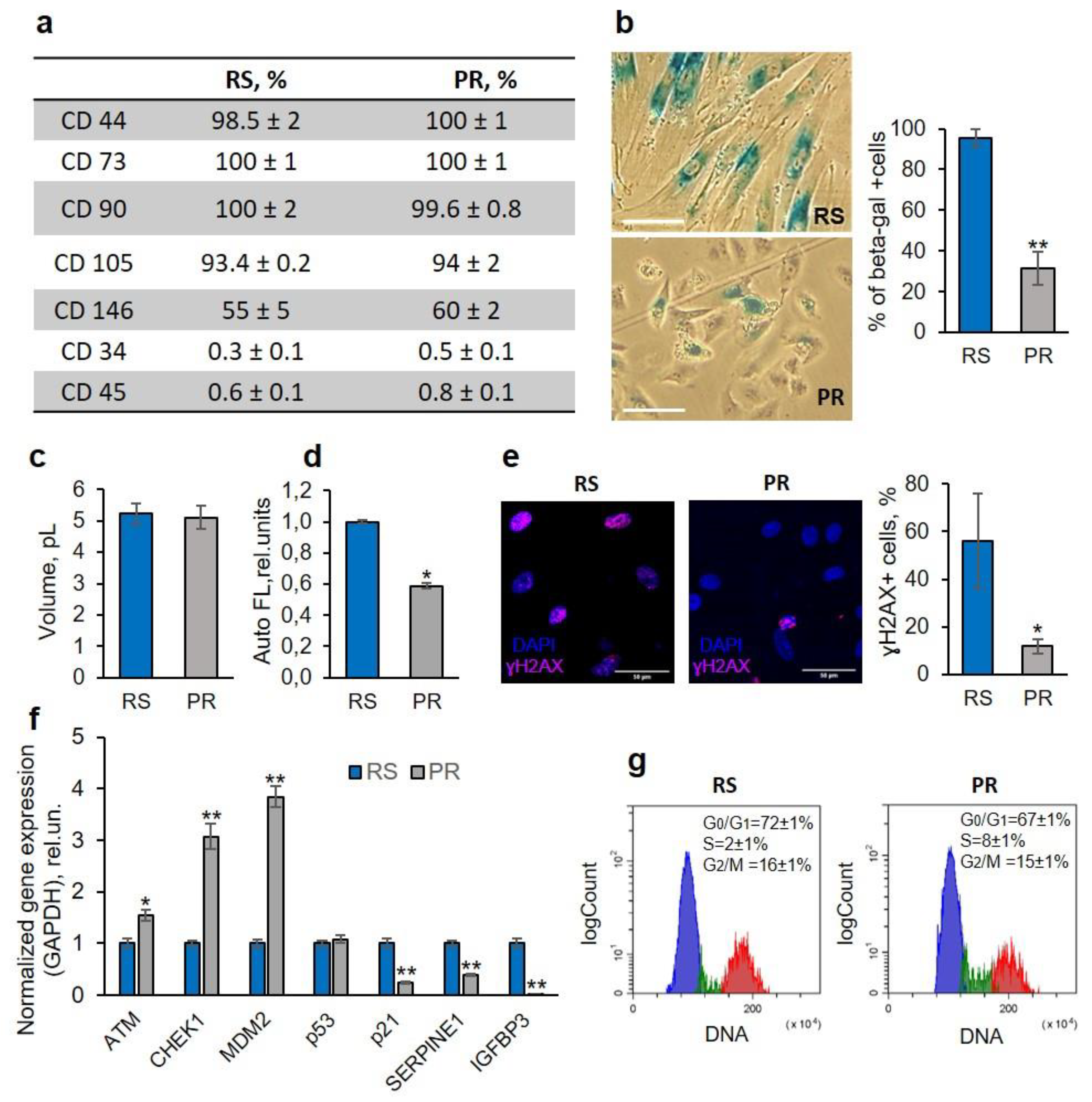

Preservation of Phenotypic Identity of PR-MSCs

To begin with, we tested whether PR-MSCs retain their phenotypic identity during partial reprogramming. Surface CD markers were analyzed using flow cytometry. The reprogrammed cells were positive for CD90, CD105, CD73, CD 44, CD 146, CD140 and did not express CD 34, CD 45 (

Figure 2A). Thus, we confirmed that after short-term expression of OSKM factors, the cells preserved all the phenotypic characteristic markers of MSCs.

Change in Morphology of PR-MSCs

A change in the morphology of PR-MSCs was observed as early as day 2 after transduction with Yamanaka factors. The cell spreading decreased significantly, the number of cells resembled young eMSCs steadily increased and reached 85% by the day 5 (visual assessment,

Figure 2B). No changes in the cell size were observed, when the volume of RS-MSCs and PR-MSCs was measured using the Scepter™ 2.0 Handheld Automated Cell Counter (

Figure 2C), but, at the same time, partial reprogramming resulted in a significant lowering of cell autofluorescence (

Figure 2D).

SA-β-Galactosidase Activity

The number of SA-β-gal-positive cells, estimated by quantitative processing of brightfield images using ImageJ software, markedly decreased on day 5 of the reprogramming process and constituted 31% of the cell population in comparison to 95% in RS-MSCs (

Figure 2B).

DNA Damage

Disruption of DNA integrity is an inherent feature of senescent cells, so the next parameter evaluated was the number of DNA double-strand breaks. Immunofluorescence analysis of γH2AX foci, a marker of DNA double-strand breaks, showed a substantial reduction in γH2AX-positive cells during partial reprogramming - from 55% observed in senescent cells to 12% in PR-MSCs on day 5 of reprogramming (

Figure 2E). In addition, we found an increase in the expression level of genes, which code the proteins responsible for DNA damage repair (ATM and Chk1), that can be considered as a consequence of the DNA repair system activation (

Figure 2F).

Propagation of Senescence

Recent research [

16,

17] have revealed a number of highly abundant proteins in senescence-associated secretory phenotype of endometrial MSCs used in this study. Among them, PAI-1 and IGFBP-3 have shown themselves as significant regulators of paracrine senescence progression within the endometrial MSC population [

16,

17]. Using RT-qPCR analysis, we found a downregulation in SERPINE1 (codes PAI-1) and IGFBP3 genes that additionally testifies to the reversal of senescence-associated characteristics of PR-MSCs.

Proliferative Activity

The arrest of cell proliferation is a key feature of cellular senescence. Using flow cytometry, we analyzed the cell cycle phase distribution of senescent and reprogrammed cells. While cycling cells were almost absent in RS-MSCs, in PR-MSCs the number of S-phase cells increased by the day 5 (

Figure 2G). In addition, qPCR analysis revealed the upregulation of MDM2 gene (negatively regulates the activity of p53). In parallel, we found a significant decrease in the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene p21, a downstream target of p53 and a marker of cellular senescence which mediates the arrest of cell proliferation (

Figure 2F). The obtained results indicate that the reprogrammed cells began to restore their proliferative activity.

Based on the all abovementioned data, we can conclude that partial reprogramming erases the markers of cellular senescence and can exert a rejuvenating effect on human RS-MSCs.

2.2. Revitalization is Accompanied by the Enhancement of Therapeutic Activity of PR-MSCs

One of the key therapeutic features of MSCs is their ability for migration to the cites of injury to stimulate the regeneration of tissue defects, such as skin wounds. We then checked if there was an upregulation in expression of genes that stimulate cell migration of PR-MSCs. We revealed an increase in expression of IL6, VEGFA, as well as of gene coding major matrix metalloproteinase -1 (MMP-1) (

Figure 3A). By interacting with corresponding receptors on the surface of MSCs, the first two activate signaling pathways that stimulate cytoskeleton reorganization, while MMP-1 provides remodeling of extracellular matrix, as a whole facilitating migration and potentially contributing to wound healing and tissue regeneration processes.

In the next step, we decided to check whether revitalization is accompanied by the enhancement of therapeutic paracrine potential of PR-MSCs. For this purpose, we collected the conditioned medium produced by both senescent and revitalized cells over a 24-hour period, from day 4 to day 5 of reprogramming. Exploiting this medium, we performed in vitro wound-healing assay using the same endometrial MSC line as for the partial reprogramming experiments but on the early passage. The obtained data demonstrated accelerated scratch overgrowth in the case of medium from PR-MSCs compared to the medium from RS-MSCs (

Figure 3B). This fact suggests that even short-term activation of pluripotent transcription factors may result in the enhancement of MSC therapeutic activity impaired after prolonged in vitro expansion of cell culture. Having come to this conclusion, we further tested the conditioned medium from revitalized MSCs for biosafety. Sendai virus, which was used for RS-MSC transduction, is a murine parainfluenza virus, expressing a hemagglutinin protein on the surface of its envelope, which can cause agglutination of erythrocytes. By carrying out hemagglutination assay using chicken blood as a source of erythrocytes, we assayed the conditioned medium for the presence of the viral components. The conditioned medium from PR-MSCs demonstrated hemagglutination activity with a titer equals to 32 hemagglutination units, which resulted in formation of lattice (diffuse reddish solution) even in highly diluted samples, in contrast to samples from RS-MSCs, in which erythrocytes precipitated (dark red pellet) (

Figure 3C). Collectively, our data suggest that partial reprogramming is a potentially effective strategy for rejuvenation of cultured MSCs in late passages, but requires an alternative strategy of reprogramming (for example, chemical reprogramming [

18]) for biomedical applications of rejuvenated cells.

3. Discussion

Partial reprogramming technique has shown promising results in amelioration of senescence-associated cell phenotype

in vitro and

in vivo [

11]. The studies carried out were mostly aimed at the rejuvenation of experimental animals or cells isolated from aged donors (mice and humans). However, the development of senescence in cell cultures is also a serious issue concerning biomedical applications of human cells, especially MSCs. At the same time, to the authors knowledge, there is very little data regarding partial reprogramming of cultured human MSCs. In the present study, we attempted to use this method to rejuvenate human MSCs underwent replicative senescence in culture. We aimed to test whether it is possible to consider cellular revitalization as a strategy for obtaining a large biomass of therapeutically active human cells after their long-term propagation. Reversal of cellular senescence in culture would make it possible to obtain an unlimited source of isogenic cells suitable for use in regenerative medicine, including the fabrication of cell products/tissue-engineered constructs and accumulation of therapeutically active conditioned medium.

At the first stage, we subjected human MSCs that underwent replicative senescence to partial reprogramming. The experiments proved the possibility of rejuvenation of MSCs that had completely lost their proliferative activity after 40 – 50 cycles of cell population doubling in culture. Reprogramming was performed by transduction of classical Yamanaka transcription factors – Oct3/4, Klf4, Sox2 and c-Myc (OKSM). Nowadays, many methods for the delivery of pluripotency factors have been developed. The most studied and widespread is the delivery of pluripotency factors using retroviruses, however, this method carries risks such as insertional mutagenesis, residual expression, and reactivation of reprogramming factors [

19]. Alternative methods for delivering reprogramming factors are: RNA transfection, transient or episomal transfection [

13,

20], chemical-based reprogramming using small molecules and growth factors [

18], as well as lipophilic compounds [

21]. In this work, we employed Sendai virus for OKSM delivery because this vector, along with episomal plasmids, possess the highest reprogramming efficiency among non-integrative protocols, and all processes associated with its replication/protein synthesis occur in the cell cytoplasm without affecting the nucleus [

22]. Typically, the duration of one cycle of partial reprogramming to achieve the rejuvenation effect in different studies varies from 2 days to 2.5 weeks, which is largely due to a balance between attempts to enhance the revitalization effect and prevent the loss of the original cellular phenotype [

11]. Our results showed that the expression of OKSM factors in senescent human MSCs for five days is sufficient for a dramatic decrease in the markers of cellular senescence while maintaining the somatic identity of the cells. The data obtained in our work allow one to use the partial reprogramming technique to study the effect of cellular revitalization, and consider PR-MSCs as a suitable model in fundamental research of aging.

After proving the erasure of senescence-associated characteristics of PR-MSCs, we assessed whether revitalization can lead to the enhancement of therapeutic potential of these cells. We showed that partial reprogramming protocol employed in this study resulted in the increase in gene expression of a number of factors stimulating cell migration – an important aspect of MSC functioning within a human body. Along with MSCs themselves, conditioned MSC medium without a cellular component appears to be another promising tool for use in regenerative medicine. Consequently, the next stage of our work was focused on the evaluation whether partial reprogramming can restore the therapeutic activity of the conditioned medium from senescent MSCs. Having carried out an

in vitro scratch assay, we found that the medium from PR-MSCs, in comparison with the medium from RS-MSCs collected after 24-hour incubation from the 4th to the 5th day of reprogramming, causes accelerated healing of the scratch on the cell monolayer. This can evidence of the improvement of wound-healing potential of the medium conditioned by revitalized cells and allows us to consider these mediums as therapeutically active substances. However, in the next set of experiments, we tested the biosafety of the media from PR-MSCs using a hemagglutination assay. The test detected the formation of erythrocyte clumps in samples from PR-MSCs, indicating the presence of free or bound viral hemagglutinin in this medium. The results obtained prove that the use of viral infection as a method of MSC revitalization may hinder the therapeutic use of media conditioned by revitalized cells. As, exploiting viral infection for rejuvenation may carry a risk for application of PR-MSCs in clinical practice, alternative methods of cellular reprogramming are needed for biomedical using of revitalized cells. The great potential may have a chemical reprogramming technique [

18].

To conclude, in the present study, we have proven the possibility of rejuvenation of human MSCs underwent replicative senescence in culture using partial reprogramming, created a biological model of replicative senescence/revitalization, and showed that the approach used can provide the potential benefits for the improvement of therapeutic activity of the conditioned MSC medium. At the same time, our experiments have proven the biological danger of medium conditioned by rejuvenated MSCs when using a viral infection for the delivery of reprogramming factors. Testing various combinations of reprogramming factors, including chemical ones, altering the duration and cyclicity of the reprogramming process, studying the rate of senescence phenotype reacquiring after the reprogramming was stopped - all these studies are necessary to create an optimized and safe protocol that will allow the future use of partial reprogramming strategy in cell therapy.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Cultures

Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs). Human MSCs have been previously derived in our laboratory from human desquamated endometrium (view in [

14]). MSCs were cultivated in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone, USA), 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, USA). Cells were maintained at 37oC, 5% CO2, and were routinely subcultured twice a week at a split ratio of 1:3.

4.2. Induction of Cell Senescence and Rejuvenation

MSC senescence. To achieve replicative senescence, MSCs were cultivated in standard growth conditions up to the 35 – 40th passage (50 – 60 cycles of cell population doubling). Cultivated cells were reseeded after reaching a subconfluent density. Up to the 25th passage MSCs were typically subcultured twice a week at the split ratio of 1:3, and later – at the split ratio of 1:2, at first twice and then once a week. MSCs that achieved replicative senescence stopped their proliferation.

MSC rejuvenation. Cells were rejuvenated after long-term cultivation (at the 35 – 40th passage) using partial reprogramming technique. Partial reprogramming was carried out by the ectopic expression of Yamanaka factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc) in senescent MSCs with the use of CytoTune-iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kit (Thermofisher Scientific, USA). The kit includes three Sendai vectors: polycistronic Klf4–Oct3/4–Sox2 (KOS), cMyc, and Klf4, and provides non-inducible permanent production of Yamanaka factors in cell cytoplasm. For the experiments, senescent MSCs were seeded in the 3 cm dishes the day before transduction (100 000 cells per dish) in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone, USA), 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, USA). On day 0, cell medium was changed to a fresh DMEM/F12 (Gibco, USA) containing three Sendai viruses. The amount of viruses added was calculated basing on the virus titers listed in manufacturer’s instruction at MOI=5:5:3 (KOS:c-Myc:Klf4). On day 1, the cell medium containing the residual viruses was replaced by a fresh full growth DMEM/F12 medium. From day 1 to 5 the full growth DMEM/F12 medium was changed daily. All assays on reprogramming cells were performed at the 5th day after transduction, enabling the characterization of cells after only short-term expression of Yamanaka factors.

4.3. Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Staining

Senescent MSC cultures were assayed for the expression of the senescence associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) with the use of the Senescence β-Galactosidase Staining Kit (Cell Signaling Technology, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each sample not less than 200 randomly selected cells were analyzed.

4.4. Autofluorescence

The increase in the cell autofluorescence (EX488/FL525 signal), which is usually associated in the senescent cells with the lipofuscin accumulation, was detected with the use of CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA).

4.5. Cell Proliferation

The arrest of cell proliferation in senescent MSCs was confirmed by measuring the growth curves with the use of CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA). In these experiments, only viable cells identified by the propidium iodide staining were counted. For cell cycle analysis, cells were harvested and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma- Aldrich, USA) and stained for 5 minutes with 2 μg/mL of 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at room temperature. Cell cycle phase distribution was assessed using flow cytometry (CytoFLEX, Beckman Coulter, 405 nm laser) with subsequent analysis by CytExpert 2.0 (Beckman Coulter, USA) software.

4.6. Cell Size Measurement

Cell volume was estimated in pL with the use of Scepter™ 2.0 Cell Counter (Merck Millipore, USA).

4.7. Immunophenotyping Analysis

MSCs were harvested using 0.05% trypsin/EDTA solution. Cells in an amount of 106/mL were suspended in PBS with 5% fetal bovine serum, incubated with antibodies to CD90, CD105, CD73, CD 44, CD 146, CD140, CD 34, CD 45 conjugated with phycoerythrin (PE) at 40C for 1 hour, and then surface markers expression was measured by flow cytometry (CytoFLEX, Beckman Coulter, USA).

4.8. RT-qPCR Analysis

RT-qPCR analysis was performed as described in [

23]. Expression of target genes was normalized to the expression GAPDH housekeeping gene. All amplification reactions were performed in triplicates.

Table 1.

The list of primers used for qPCR assay.

Table 1.

The list of primers used for qPCR assay.

| Gene |

Primer sequence |

Annealing temperature (T0C) |

| p21 |

F: 5′-CCACATGGTCTTCCTCTGCTG-3′

R: 5′-GATGTCCGTCAGAACCCATG-3′ |

61 |

| p16 |

F: 5′-GAGCAGCATGGAGCCTTC-3′

R: 5′-CCTCCGACCGTAACTATTCG-3′ |

58 |

| MDM2 |

F:5’-TGGGCAGCTTGAAGCAGTTG-3′

R:5’-CAGGCTGCCATGTGACCTAAGA-3′ |

62 |

| CHEK1 |

F:5′-ACCCCAGGATCCTCACAGAA-3′

R:5′-AGCAGCACTATATTCACCAGGA-3′ |

62 |

| ATM |

F: 5′-CAGGCGAAAAGAATCTGGGG-3′

R: 5′-GCACAAAGTAGGGTGGGAAAGC-3′ |

62 |

| GAPDH |

F: 5'-GAGGTCAATGAAGGGGTCAT-3′

R: 5'-AGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGTA-3′ |

59-62 |

| p53 |

F: 5'-CCTCAGCATCTTATCCGAGTGG-3′

R: 5'-TGGATGGTGGTACAGTCAGAGC-3′ |

60 |

| IGFBP3 |

F: 5’-TCACCTGAAGTTCCTCAATGT-3ʹ

R: 5’- ACTTATCCACACACCAGCAGA-3ʹ |

60 |

| SERPINE1 |

F: 5'-CTCATCAGCCACTGGAAAGGCA-3′

R: 5'-GACTCGTGAAGTCAGCCTGAAAC-3′ |

60 |

| IL6 |

F: 5'-AAGCCAGAGCTGTGCAGATG-3′

R: 5'-GTCCTGCAGCCACTGGTTCT-3′ |

60 |

| VEGFA |

F: 5'-CTACCTCCACCATGCCAAGT-3′

R: 5'- GATAGACATCCATGAACTTCACCA-3′ |

60 |

| MMP1 |

F: 5′-ACAGCTTCCCAGCGACTCTA-3′

R: 5′-TTGCCTCCCATCATTCTTCAGG-3′ |

60 |

4.9. Immunofluorescence Analysis

Immunofluorescence analysis was performed as described in [

23]. Primary antibodies: anti-ɣH2AX (1:500, Abcam, Great Britain), secondary antibodies: GAM Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500, Thermofisher Scientific, USA). The coverslips were imaged using confocal laser scanning microscopy (Olympus FV3000, Olympus Corporation).

4.10. Wound-Healing Assay

The conditioned medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum was collected after 24 hours incubation from 4th to 5th day after induction of reprogramming from transduced and control senescent MSCs. The collected medium was then centrifuged on 3,000g to remove cell debris and stored at -800C until use. Two-well silicone inserts (Ibidi, Graefelfing, Germany) in 24-well plates were used to create a defined cell-free scratch. 2×104 MSCs were seeded on both sides of the insert and incubated overnight to reach a confluent monolayer. Then the inserts were removed, the cells were washed with PBS, and 800 µL of conditioned medium from partially reprogrammed or control senescent cells was added to the well. Phase-contrast MSC images were taken at 0, 6, 20 and 24 h to monitor the gap closure.

4.11. Hemagglutination Assay

Firstly, a serial 2-fold dilution of conditioned medium used for wound-healing assay was performed with 0.9% saline solution in a U - bottom shaped 96-well immunological plate (Nunc, USA), starting with the 100 µl of undiluted conditioned medium in the first row. After that, 50 µl of 1% chicken blood suspension in 0.9% saline solution was added to each well and mixed. Then the plate was incubated for 30 minutes at 40C. The appearance of dark red pellet evidences of the absence of agglutination in a sample, while formation of lattice indicates the presence of the erythrocyte/viral hemagglutinin clumps. The hemagglutination titer is reciprocal of the highest dilution of conditioned medium exhibiting hemagglutination.

4.12. Statistics

All experiments were repeated at least 3 times. Data are presented as means ±SD, when indicated. Statistical significance in the pairwise comparisons was evaluated by Student's t-test, p <0.05 was considered to be significant. Microscopy images and flow cytometry histograms shown correspond to the most representative experiments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.I. and M.S.; methodology, J.I., M.S., L.A., I.Ko.; software, J.I., M.S., N.G., I.K.; validation, J.S., M.S. and O.L.; formal analysis, L.L. and I.Ko.; investigation, J.I., M.S., N.P., L.L., I.Ko., N.G., I.K., A.D., T.G., V.Z.; resources, N.P.; data curation, J.I., M.S., I.Ko., O.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.I. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, , J.S., M.S. and O.L.; visualization, M.S., I.Ko., N.G., I.K.; supervision, J.I. and O.L.; project administration, J.I.; funding acquisition, J.I. and O.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

MSC rejuvenation project was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (grant No. 23-74-01142). MSC cultivation was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (grant No. 21-74-20178). .

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the donors of endometrial MSCs for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Anastasia Pulkina (Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation) for her assistance with hemagglutination assay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, J.; Liu, X.X.; Fan, H.; Tang, Q.; Shou, Z.X.; Zuo, D.M.; Zou, Z.; Xu, M.; Chen, Q.Y.; Peng, Y.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Protect against Experimental Colitis via Attenuating Colon Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.; Weng, J.; Guo, L.; Chen, X.; Du, X. Novel Insights into MSC-EVs Therapy for Immune Diseases. Biomark. Res. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Diaz, M.; Quiñones-Vico, M.I.; de la Torre, R.S.; Montero-Vílchez, T.; Sierra-Sánchez, A.; Molina-Leyva, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Biodistribution of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells after Administration in Animal Models and Humans: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.; Horvath, S.; Raj, K.; Lowe, D.; Horvath, S.; Raj, K. Epigenetic Clock Analyses of Cellular Senescence and Ageing. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 8524–8531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Lee, Y.D.; Wagers, A.J. Stem Cell Aging: Mechanisms, Regulators and Therapeutic Opportunities. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Xiong, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Hong, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Fu, X.; Sun, X. Cellular Rejuvenation: Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Interventions for Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utikal, J.; Polo, J.M.; Stadtfeld, M.; Maherali, N.; Kulalert, W.; Walsh, R.M.; Khalil, A.; Rheinwald, J.G.; Hochedlinger, K. Immortalization Eliminates a Roadblock during Cellular Reprogramming into IPS Cells. Nature 2009, 460, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapasset, L.; Milhavet, O.; Prieur, A.; Besnard, E.; Babled, A.; Ät-Hamou, N.; Leschik, J.; Pellestor, F.; Ramirez, J.M.; De Vos, J.; et al. Rejuvenating Senescent and Centenarian Human Cells by Reprogramming through the Pluripotent State. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 2248–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, J.; Paquola, A.C.M.; Ku, M.; Hatch, E.; Böhnke, L.; Ladjevardi, S.; McGrath, S.; Campbell, B.; Lee, H.; Herdy, J.R.; et al. Directly Reprogrammed Human Neurons Retain Aging-Associated Transcriptomic Signatures and Reveal Age-Related Nucleocytoplasmic Defects. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, A.; Reddy, P.; Martinez-Redondo, P.; Platero-Luengo, A.; Hatanaka, F.; Hishida, T.; Li, M.; Lam, D.; Kurita, M.; Beyret, E.; et al. In vivo Amelioration of Age-Associated Hallmarks by Partial Reprogramming. Cell 2016, 167, 1719–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.B.; Zhakupova, A. Age Reprogramming: Cell Rejuvenation by Partial Reprogramming. Development 2022, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, X. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Senescence and Rejuvenation: Current Status and Challenges. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 542629. [Google Scholar]

- Göbel, C.; Goetzke, R.; Eggermann, T.; Wagner, W. Interrupted Reprogramming into Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Does Not Rejuvenate Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Sci. Reports 2018 81 2018, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemelko, V.I.; Grinchuk, T.M.; Domnina, A.P.; Artzibasheva, I. V.; Zenin, V. V.; Kirsanov, A.A.; Bichevaia, N.K.; Korsak, V.S.; Nikolsky, N.N. Multipotent Mesenchymal Stem Cells of Desquamated Endometrium: Isolation, Characterization, and Application as a Feeder Layer for Maintenance of Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell tissue biol. 2012, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulou, E.A.; Tsimaratou, K.; Evangelou, K.; Fernandez-Marcos, P.J.; Zoumpourlis, V.; Trougakos, I.P.; Kletsas, D.; Bartek, J.; Serrano, M.; Gorgoulis, V.G. Specific Lipofuscin Staining as a Novel Biomarker to Detect Replicative and Stress-Induced Senescence. A Method Applicable in Cryo-Preserved and Archival Tissues. Aging (Albany NY) 2013, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griukova, A.; Deryabin, P.; Shatrova, A.; Burova, E.; Severino, V.; Farina, A.; Nikolsky, N.; Borodkina, A. Molecular Basis of Senescence Transmitting in the Population of Human Endometrial Stromal Cells. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 9912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassilieva, I.; Kosheverova, V.; Vitte, M.; Kamentseva, R.; Shatrova, A.; Tsupkina, N.; Skvortsova, E.; Borodkina, A.; Tolkunova, E.; Nikolsky, N.; et al. Paracrine Senescence of Human Endometrial Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Role for the Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 3. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Petty, C.A.; Dixon-McDougall, T.; Lopez, M.V.; Tyshkovskiy, A.; Maybury-Lewis, S.; Tian, X.; Ibrahim, N.; Chen, Z.; Griffin, P.T.; et al. Chemically Induced Reprogramming to Reverse Cellular Aging. Aging (Albany. NY). 2023, 15, 5966–5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klawitter, S.; Fuchs, N. V.; Upton, K.R.; Muñoz-Lopez, M.; Shukla, R.; Wang, J.; Garcia-Cañadas, M.; Lopez-Ruiz, C.; Gerhardt, D.J.; Sebe, A.; et al. Reprogramming Triggers Endogenous L1 and Alu Retrotransposition in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, T.J.; Quarta, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Colville, A.; Paine, P.; Doan, L.; Tran, C.M.; Chu, C.R.; Horvath, S.; Qi, L.S.; et al. Transient Non-Integrative Expression of Nuclear Reprogramming Factors Promotes Multifaceted Amelioration of Aging in Human Cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Meng, G.; Lyu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Chemical Reprogramming of Human Somatic Cells to Pluripotent Stem Cells. Nature 2022, 605, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, M.; Desole, G.; Costanzi, G.; Lavezzo, E.; Palù, G.; Barzon, L. Reprogramming Methods Do Not Affect Gene Expression Profile of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, J.; Guriev, N.; Pugovkina, N.; Lyublinskaya, O. Inhibition of Thioredoxin Reductase Activity Reduces the Antioxidant Defense Capacity of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells under Conditions of Mild but Not Severe Oxidative Stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 642, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).