Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

09 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The proposed methodology integrates elements for obtaining energy shortage, congestion in transmission network, regional reserve margin performance, power plant installation regions that could significantly impact emissions reduction, and technologies with higher/lower plant factors.

- Disaggregated data is included for different parameters such as generation cost, availability factors, or regional transmission capacity.

- The case studies, which are a crucial part of this research, demonstrate the importance of disaggregating data for the identification of vulnerabilities in decarbonization scenarios of a Power Electrical System.

- The general economic dispatch model is extended to contemplate the characteristics of the SEN using four different sets of variables and parameters (technologies, generation regions, consumption regions, and time steps).

- The model’s programming runs under the open-source platform Python Optimization Modelling (PYOMO), which is freely available in the repository https://github.com/IhanKaydarin/Multi-regional-time-step-and-technology-economic-dispatch

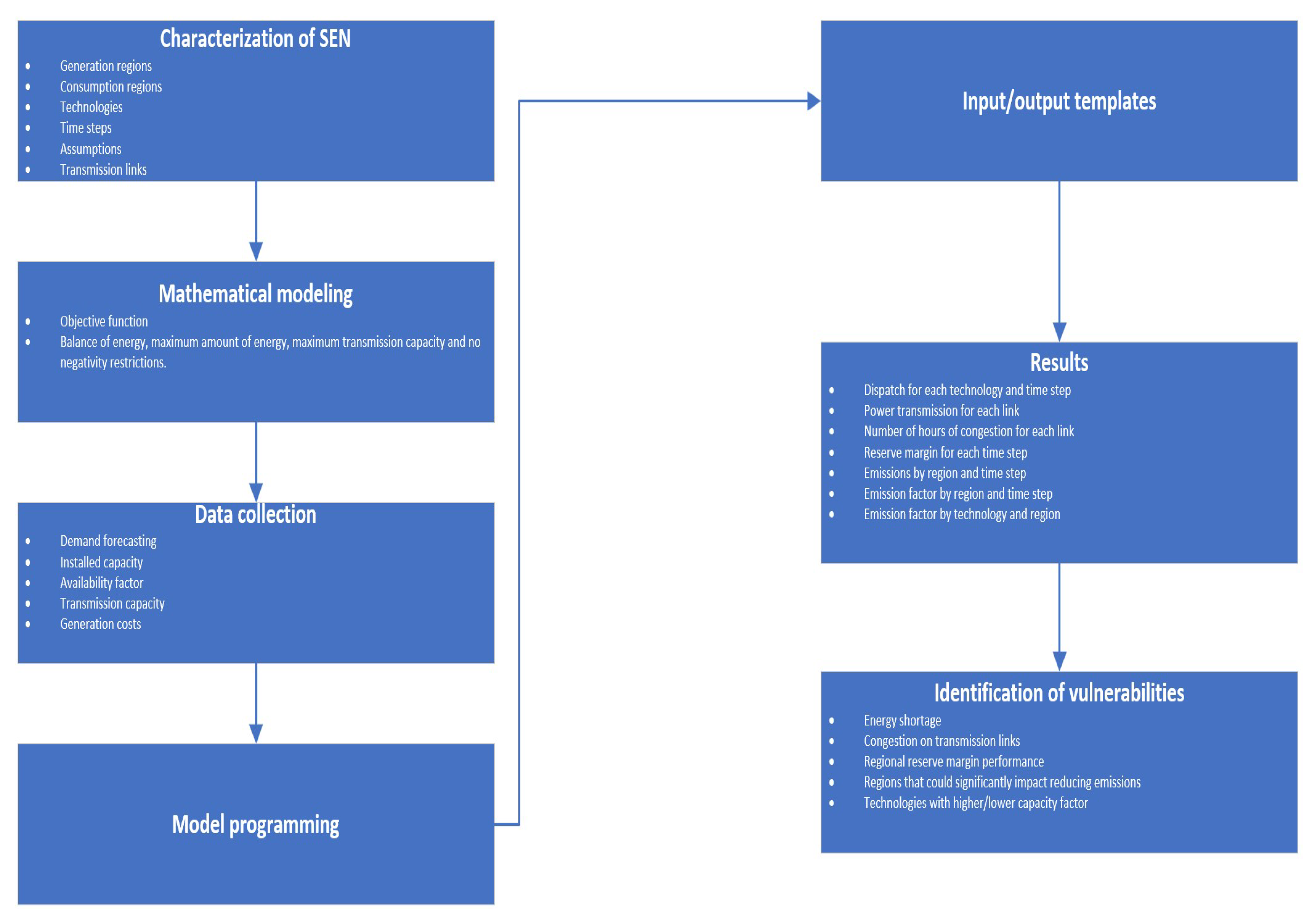

2. Problem Statement and Methodology

- Characterization of electrical power system

- Mathematical modeling

- Data collection

- Model programming

- Input/output templates

- Results

- Identification of vulnerabilities

2.1. Characterization of Electrical Power System

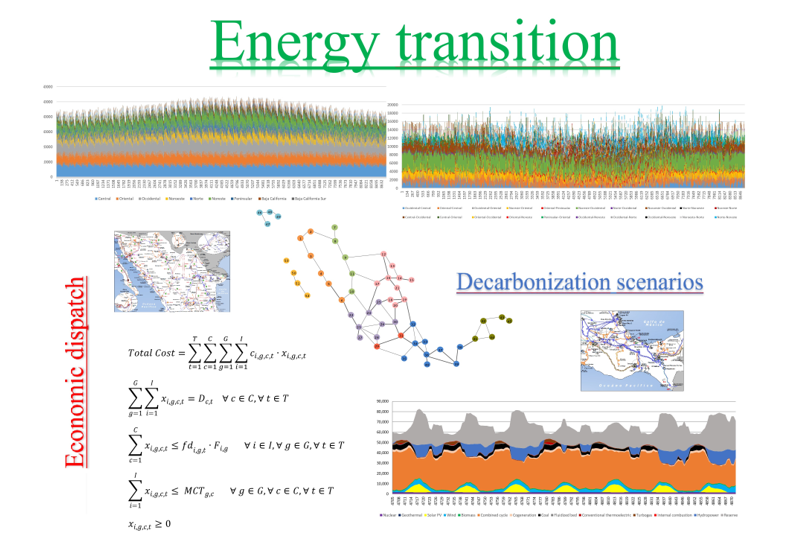

2.2. Mathematical Modeling

2.2.1. Assumptions

2.2.2. Objective Function

2.2.3. Restrictions

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Model Programming

2.5. Input/Output Templates

2.6. Results

- Hourly energy shortage: It can be determined if any restrictions are unmet. There are diverse reasons why this situation could occur, such as the low availability of intermittent technologies, congestion or limited transmission capacity, or the region’s lack of self-supply capacity. Nevertheless, it is possible to overcome this inconvenience by proposing an extra technology with the highest generation cost so that when it is dispatched, the quantity, hours, and region of missing energy can be known.

-

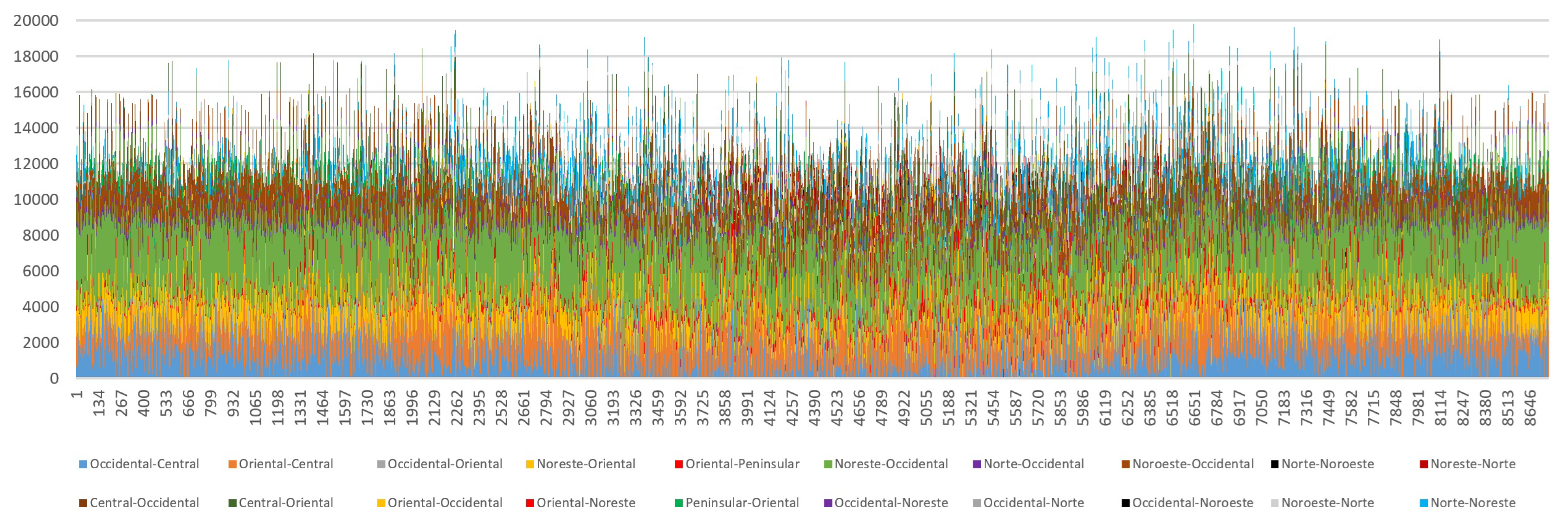

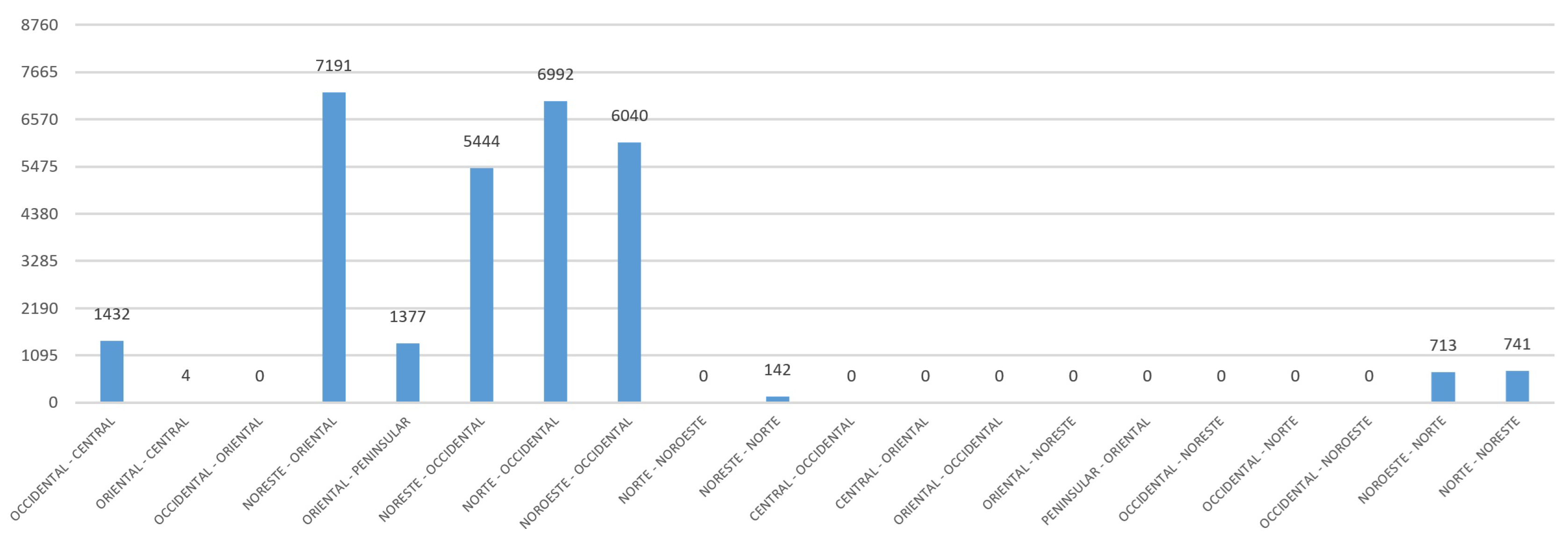

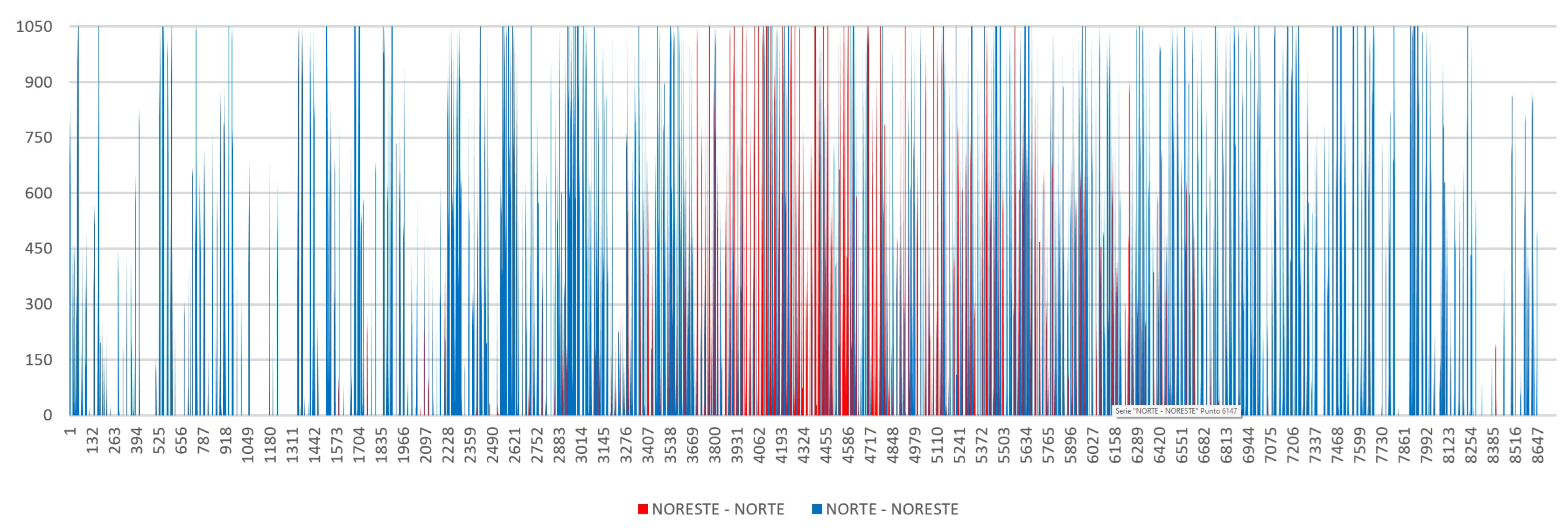

Hours of congestion on transmission lines: This aspect is obtained by counting the hours in which the energy transmitted from one region to another is equal to or greater than 90% of the link capacity. This calculation is shown in equations 6 and 7.Those links with the highest number of hours of congestion represent the regions with the most significant external power dependence, high potential to increase the national transmission network, and areas of opportunity to reduce generation costs.

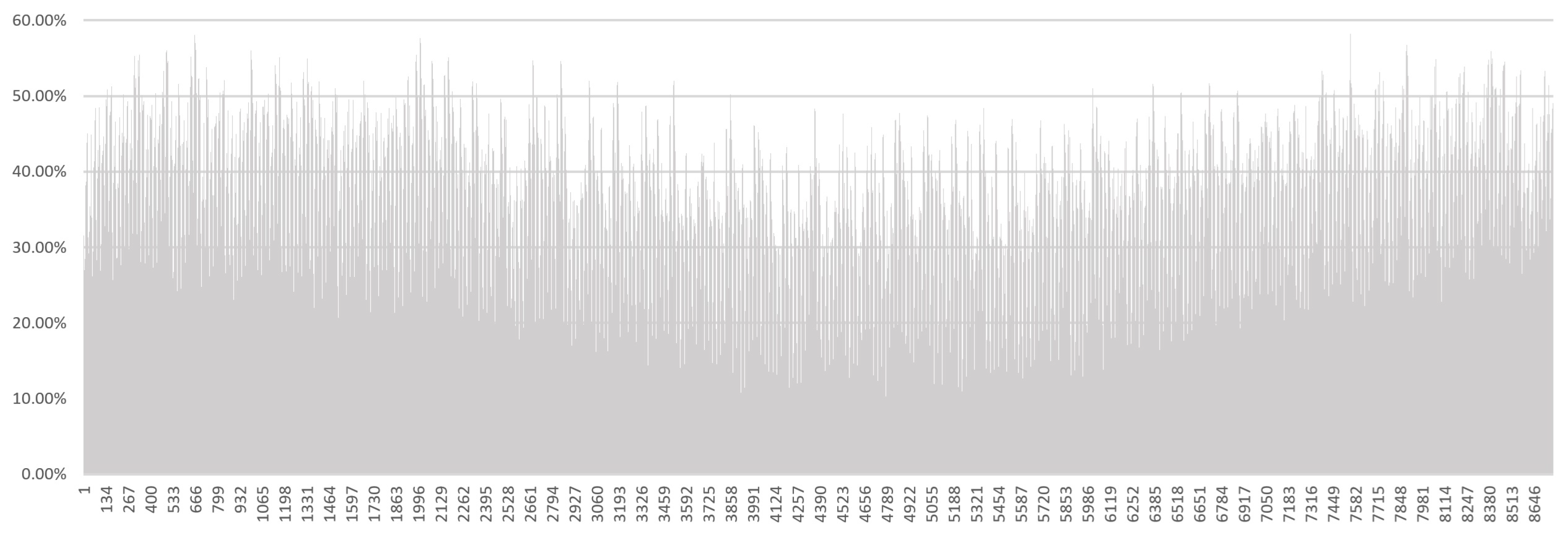

- Regional reserve margin performance: This factor identifies the regions vulnerable to changes in the generation availability of the power units installed in the region. In addition, those regions that meet the indicative values established in the reliability policy are identified. The regional reserve margin is determined through Equation (8):

- Regions where power plants are installed that could significantly impact reducing emissions must be identified: The plants with the highest emission factor and the highest generation must be identified. Nevertheless, it is essential to remember that proposing to install a new plant with a low emission factor requires a more exhaustive analysis than described in this research.

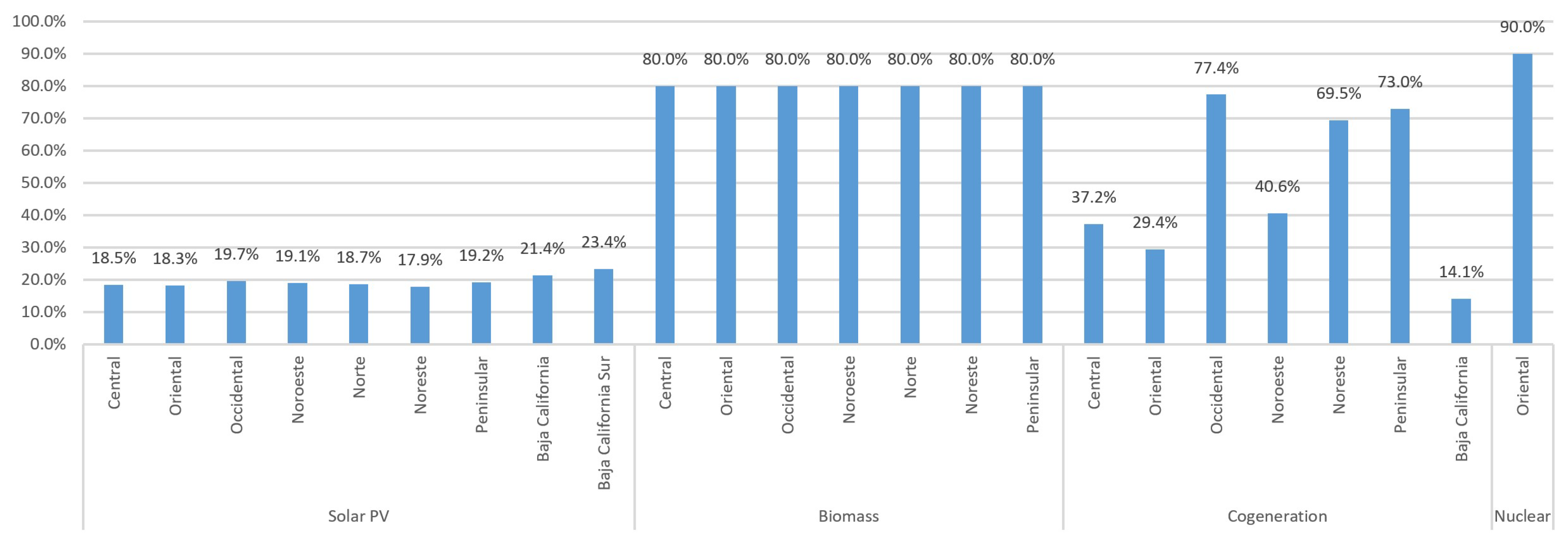

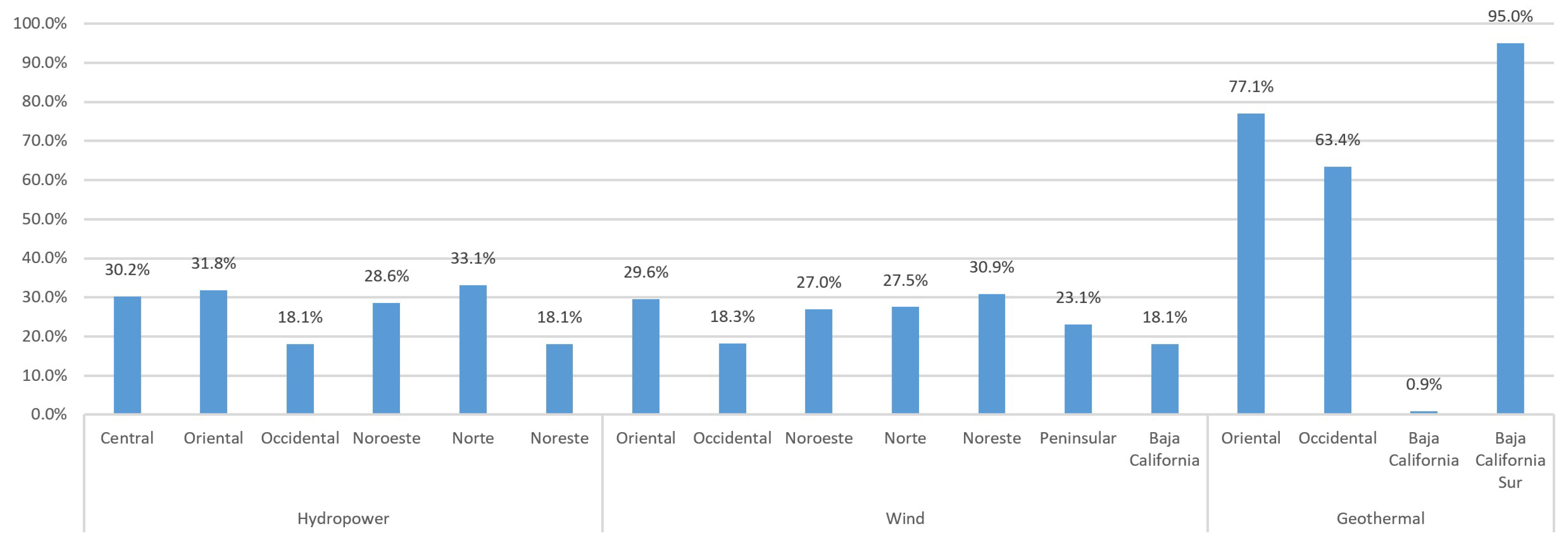

- Technologies with higher/lower capacity factor: This parameter provides valuable information regarding the units essential for energy supply and the underutilized plants.

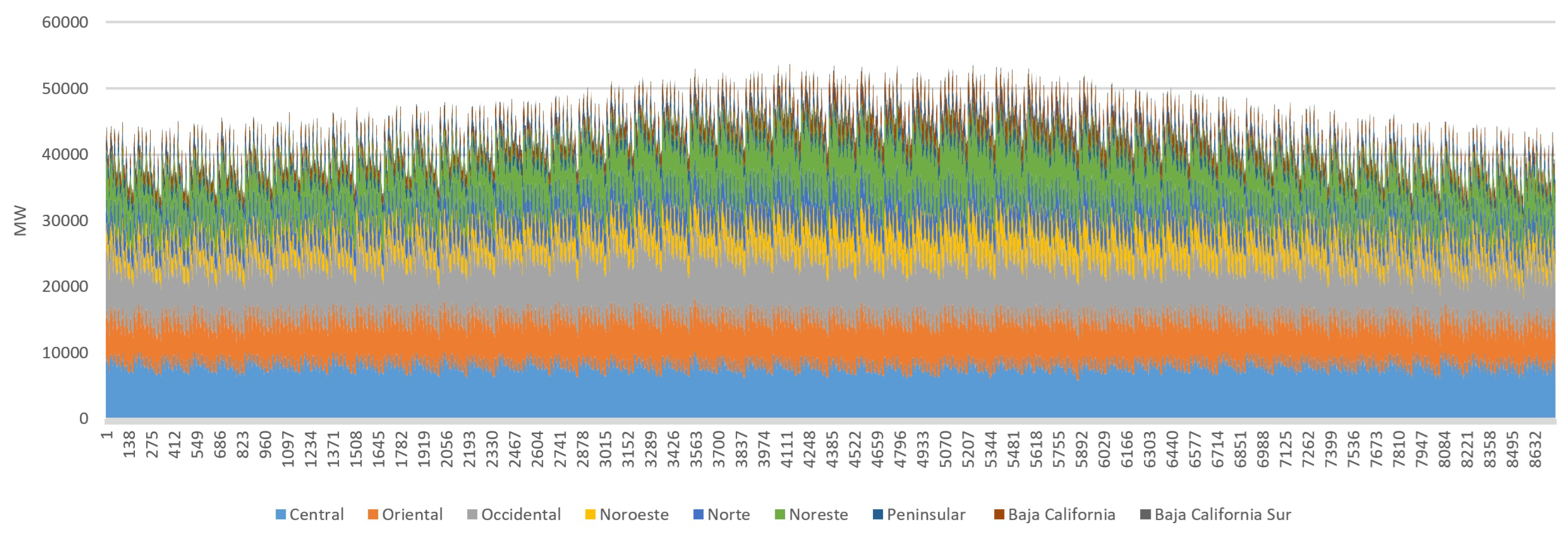

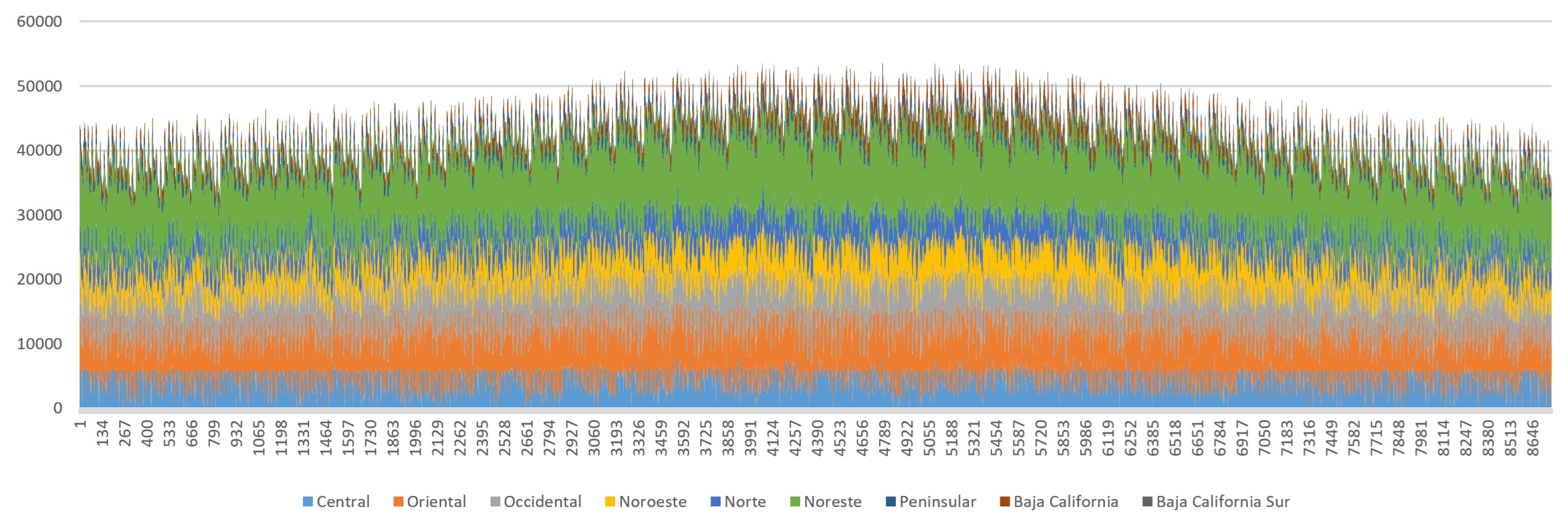

3. Case Studies and Assumptions

3.1. Characterization of SEN

3.2. Mathematical Modeling

3.2.1. Assumptions for SEN 2025

- International interconnections are not considered.

- Availability factors are averaged for thermoelectric, combined cycle, coal-fired, turbogas, internal combustion, fluidized bed, geothermal, bioenergy, cogeneration, and nuclear technologies.

- The total installed capacity for each technology in each region was used.

- The generation cost considers the levelized fuel cost, the regional increase in fuel costs, and the operation and maintenance cost.

- Availability factors for thermal technologies are annual averages.

- Seasons of unavailability due to preventive maintenance of the plants are not considered.

3.2.2. Objective Function of SEN 2025

3.2.3. Restrictions of SEN 2025

- Supply hourly demand by consumption region and time step:

- Maximum power generation by technology, generation region and time step:

- Maximum power grid capacity:

- No negativity:

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Model Programming

3.5. Input/Output Templates for SEN 2025

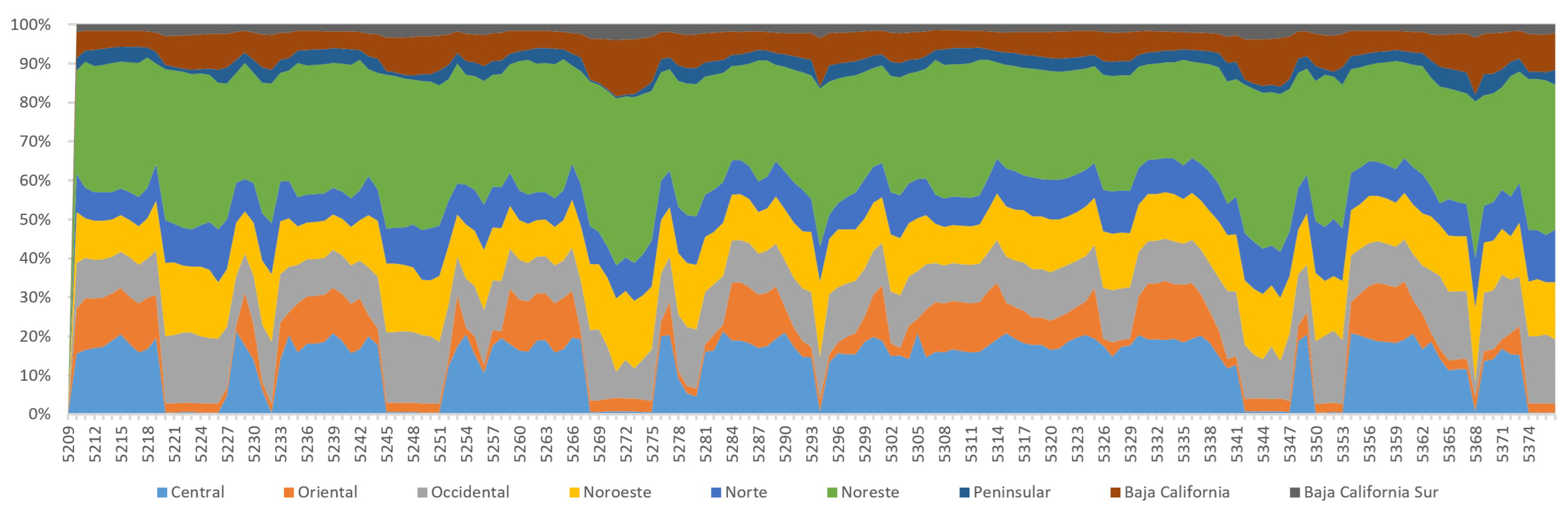

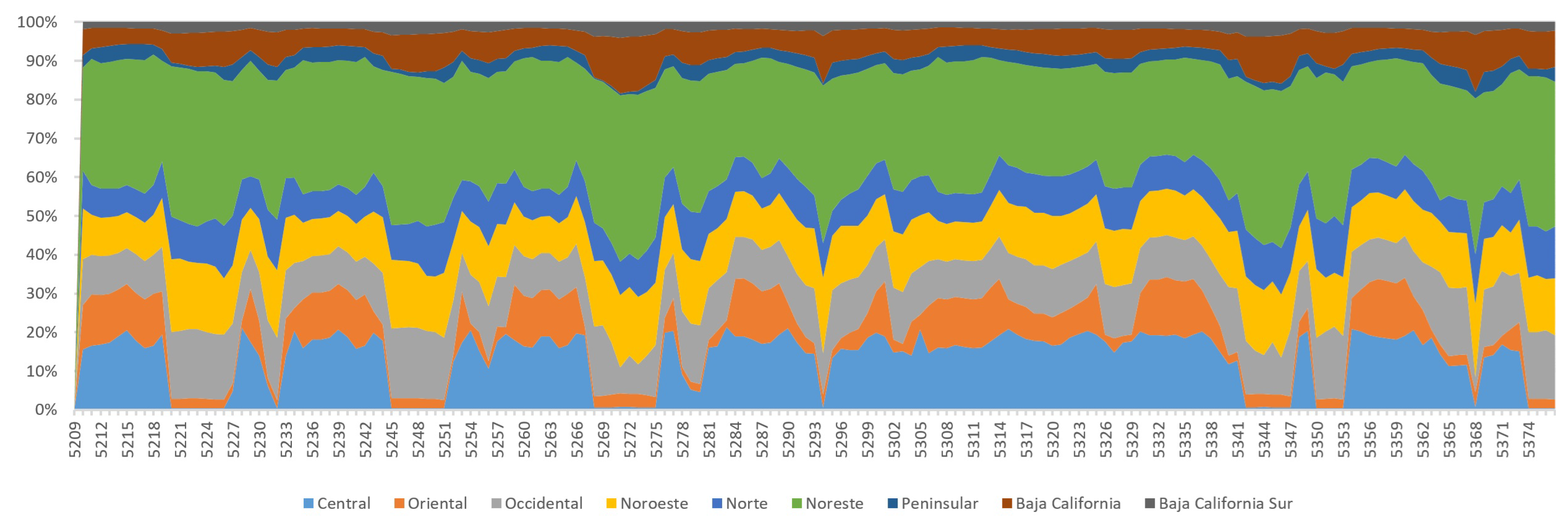

3.6. Results of SEN 2025

3.6.1. Hourly Energy Shortage

3.6.2. Hours of Congestion on Transmission Lines

3.6.3. Regional Reserve Margin Performance

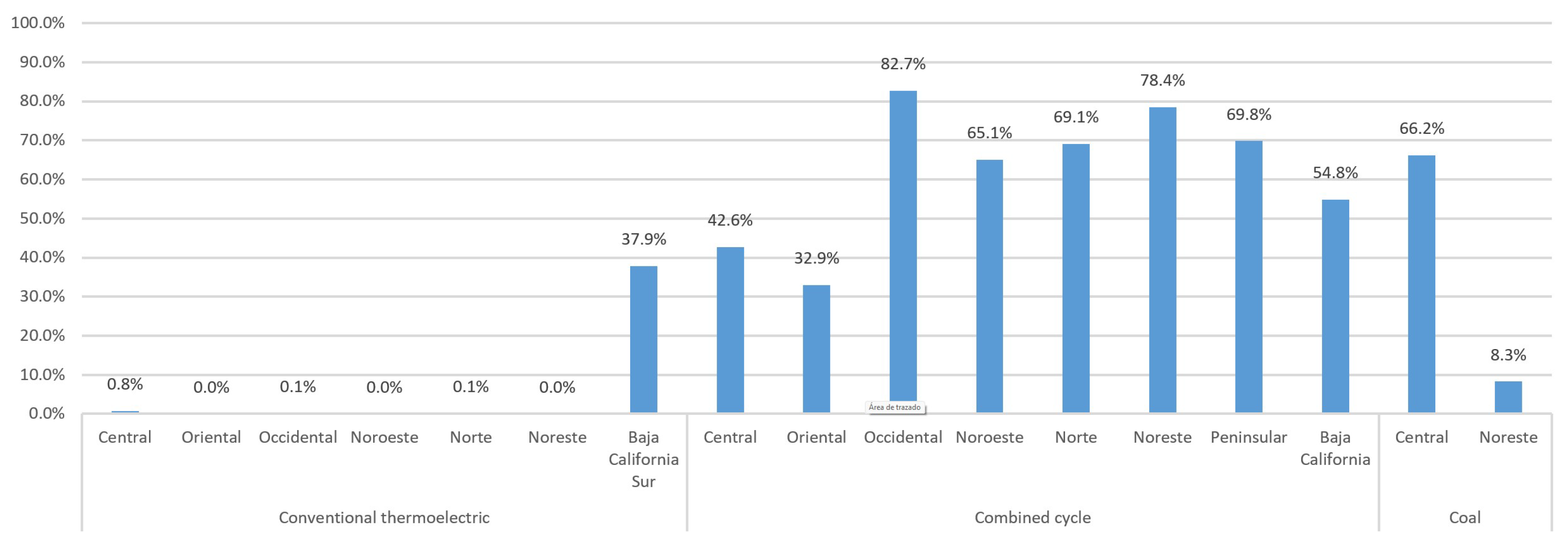

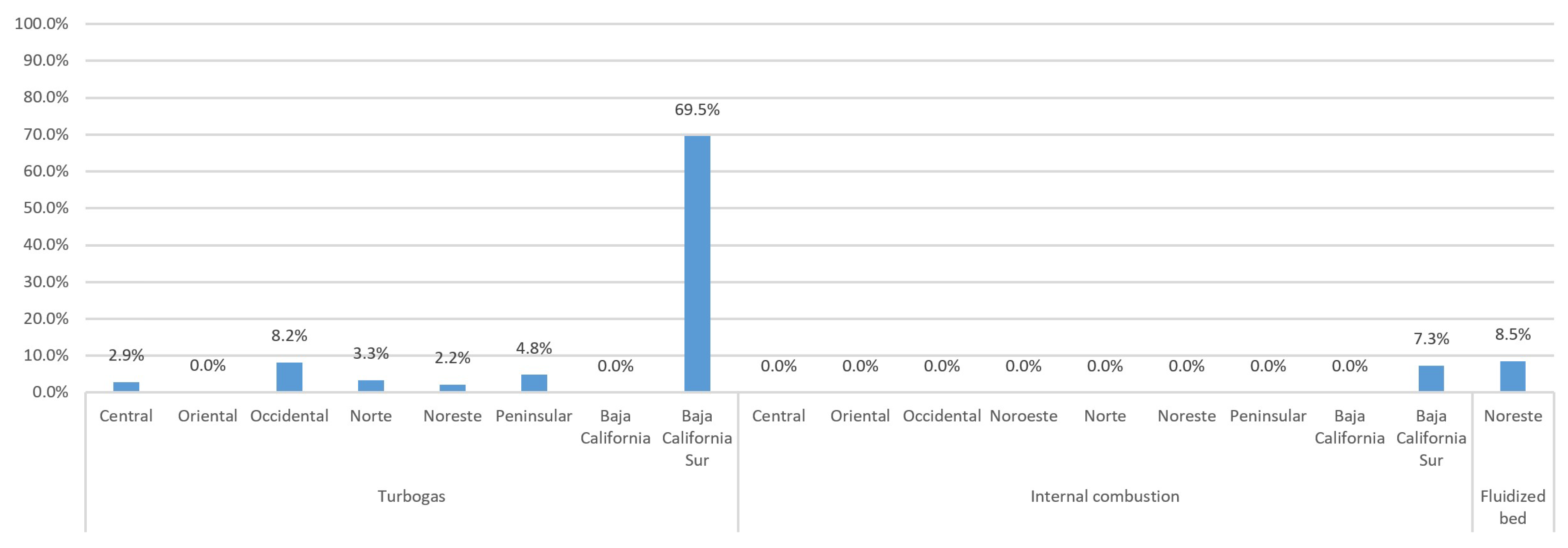

3.6.4. Regions Where Power Plants Are Installed That Could Significantly Impact Reducing Emissions Must be Identified

3.6.5. Technologies with Higher/Lower Capacity Factor

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shukla, P.R.; Skeg, J.; Buendia, E.C.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Pörtner, H.O.; Roberts, D.; Zhai, P.; Slade, R.; Connors, S.; Van Diemen, S.; others. Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems 2019.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, 2021. Accessed: 2024-09-10.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, 2022. Accessed: 2024-09-10.

- Advani, N.K. Assessing species vulnerability to climate change, and implementing practical solutions. Biological Conservation 2023, 286, 110284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hong, J.B.; Han, I.S.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, D.H. Vulnerability assessment of Korean fisheries to climate change. Marine Policy 2023, 155, 105735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.G.T.; Chiu, W.A.; Nasser, E.; Proville, J.; Barone, A.; Danforth, C.; Kim, B.; Prozzi, J.; Craft, E. Characterizing vulnerabilities to climate change across the United States. Environment international 2023, 172, 107772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeagbo, O.; Bamire, A.; Akinola, A.; Adeagbo, A.; Oluwole, T.; Ojedokun, O.; Ojo, T.; Kassem, H.; Emenike, C. The level of adoption of multiple climate change adaptation strategies: Evidence from smallholder maize farmers in Southwest Nigeria. Scientific African 2023, 22, e01971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayaka, B.; Robert, D.; Siriwardana, C.; Adikariwattage, V.; Pasindu, H.; Setunge, S.; Amaratunga, D. Identifying and prioritizing climate change adaptation measures in the context of electricity, transportation and water infrastructure: A case study. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2023, 99, 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedtha, S.; Pramanik, M.; Szabo, S.; Wilson, K.; Park, K.S. Climate change perception and adaptation strategies to multiple climatic hazards: Evidence from the northeast of Thailand. Environmental Development 2023, 48, 100906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzammil, M.; Zahid, A.; Farooq, U.; Saddique, N.; Breuer, L. Climate change adaptation strategies for sustainable water management in the Indus basin of Pakistan. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 878, 163143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Adoption of the Paris Agreement, 2015. Accessed: 2024-09-10.

- Bashir, M.F.; Benjiang, M.; Hussain, H.I.; Shahbaz, M.; Koca, K.; Shahzadi, I. Evaluating environmental commitments to COP21 and the role of economic complexity, renewable energy, financial development, urbanization, and energy innovation: empirical evidence from the RCEP countries. Renewable Energy 2022, 184, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Meena, R.S.; Kumar, S.; Dhyani, S.; Sheoran, S.; Singh, H.M.; Pathak, V.V.; Khalid, Z.; Singh, A.; Chopra, K.; others. India’s renewable energy research and policies to phase down coal: Success after Paris agreement and possibilities post-Glasgow Climate Pact. Biomass and Bioenergy 2023, 177, 106944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balibar, S. Energy transitions after COP21 and 22. Comptes Rendus. Physique 2017, 18, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, M.; Ji, X.; Kirikkaleli, D.; Xu, Q. COP21 Roadmap: Do innovation, financial development, and transportation infrastructure matter for environmental sustainability in China? Journal of environmental management 2020, 271, 111026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnčec, D.; Penca, J.; Lovec, M. The COVID-19 pandemic and the EU: From a sustainable energy transition to a green transition? Energy Policy 2023, 175, 113453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Yu, L.; Xue, R.; Zhuang, S.; Shan, Y. Global low-carbon energy transition in the post-COVID-19 era. Applied energy 2022, 307, 118205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mišík, M.; Nosko, A. Post-pandemic lessons for EU energy and climate policy after the Russian invasion of Ukraine: Introduction to a special issue on EU green recovery in the post-Covid-19 period. Energy Policy 2023, 177, 113546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żuk, P.; Żuk, P. National energy security or acceleration of transition? Energy policy after the war in Ukraine. Joule 2022, 6, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Zhang, M. Evolutionary game on international energy trade under the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Energy Economics 2023, 125, 106827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślusarczyk, B.; Chłąd, M.; Michałek, J.; Dacko-Pikiewicz, Z.; Androniceanu, A. Strategies for supplying enterprises with energy in the context of changing coal prices on the Polish market-The effect of the war in Ukraine. Resources Policy 2023, 85, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J. The Russia-Ukraine conflict and the automotive energy transition: Empirical evidence from China. Energy 2023, 284, 128562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Yue, S.; Nghiem, X.H.; Duan, M. Exploring the risk and economic vulnerability of global energy supply chain interruption in the context of Russo-Ukrainian war. Resources Policy 2023, 81, 103373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de México, G. Contribución Prevista y Determinada a Nivel Nacional (INDC) de México, 2015. Accedido el: 11 de septiembre de 2024.

- de México Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático (INECC), G. Inventario Nacional de Emisiones de Gases y Compuestos de Efecto Invernadero, 2024. Accedido el: 11 de septiembre de 2024.

- de Protección al Ambiente (PROFEPA), P.F. Ley General de Cambio Climático, 2024. Accedido el: 11 de septiembre de 2024.

- de la Federación (DOF), D.O. Decreto por el que se expide la Ley de Transición Energética, 2015. Accedido el: 11 de septiembre de 2024.

- de Energía (SENER), S. Programa de Desarrollo del Sistema Eléctrico Nacional 2024-2038, 2024. Accedido el: 11 de septiembre de 2024.

- Gu, B.; Zhai, H.; An, Y.; Khanh, N.Q.; Ding, Z. Low-carbon transition of Southeast Asian power systems–A SWOT analysis. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2023, 58, 103361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, M.S.; Manrique, L.G.; Peña, I.R.; Navarro, A.D.L.V. Drivers of electricity GHG emissions and the role of natural gas in mexican energy transition. Energy Policy 2023, 173, 113316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diezmartínez, C. Clean energy transition in Mexico: Policy recommendations for the deployment of energy storage technologies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 135, 110407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Lüpke, H.; Well, M. Analyzing climate and energy policy integration: the case of the Mexican energy transition. Climate Policy 2020, 20, 832–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrejon-Campos, O. Evolution of clean energy technologies in Mexico: A multi-perspective analysis. Energy for Sustainable Development 2022, 67, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Arévalo, T.I.; López-Flores, F.J.; Raya-Tapia, A.Y.; Ramírez-Márquez, C.; Ponce-Ortega, J.M. Optimal expansion for a clean power sector transition in Mexico based on predicted electricity demand using deep learning scheme. Applied Energy 2023, 348, 121597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banacloche, S.; Cadarso, M.A.; Monsalve, F.; Lechon, Y. Assessment of the sustainability of Mexico green investments in the road to Paris. Energy Policy 2020, 141, 111458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.M.; Baker, E.; Galicia, J.H. Regional Power Planning Robust to Multiple Models: Meeting Mexico’s 2050 Climate Goals. Energy and Climate Change 2022, 3, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Amaro, J.J.; Østergaard, P.A.; Sheinbaum-Pardo, C. Optimal energy mix for transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources–The case of the Mexican electricity system. Applied Energy 2015, 150, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalaq, A.; Alqunun, K.; Refaat, M.M.; Farah, A.; Benabdallah, F.; Ali, Z.M.; Aleem, S.H.A. Towards increasing hosting capacity of modern power systems through generation and transmission expansion planning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhai, Q.; Yuan, W.; Wu, J. Capacity expansion planning for wind power and energy storage considering hourly robust transmission constrained unit commitment. Applied Energy 2021, 302, 117570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Geng, L.; Cai, Y.; Li, X. Economic dispatch of multi-area integrated electricity and natural gas systems considering emission and hourly spinning reserve constraints. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2021, 132, 107177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Lv, T. Power system planning with increasing variable renewable energy: A review of optimization models. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 246, 118962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter/Variable | Sets | Number of values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technologies (13) |

Generation region (9) |

Consumption region (9) |

Time steps (8760) |

||

| Cost | X | X | X | X | 9224280 |

| Demand | X | X | 78840 | ||

| Availability factor | X | X | X | 1024920 | |

| Installed capacity | X | X | X | 1024920 | |

| Transmission capacity | X | X | X | 709560 | |

| Energy dispatch | X | X | X | X | 9224280 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).