Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

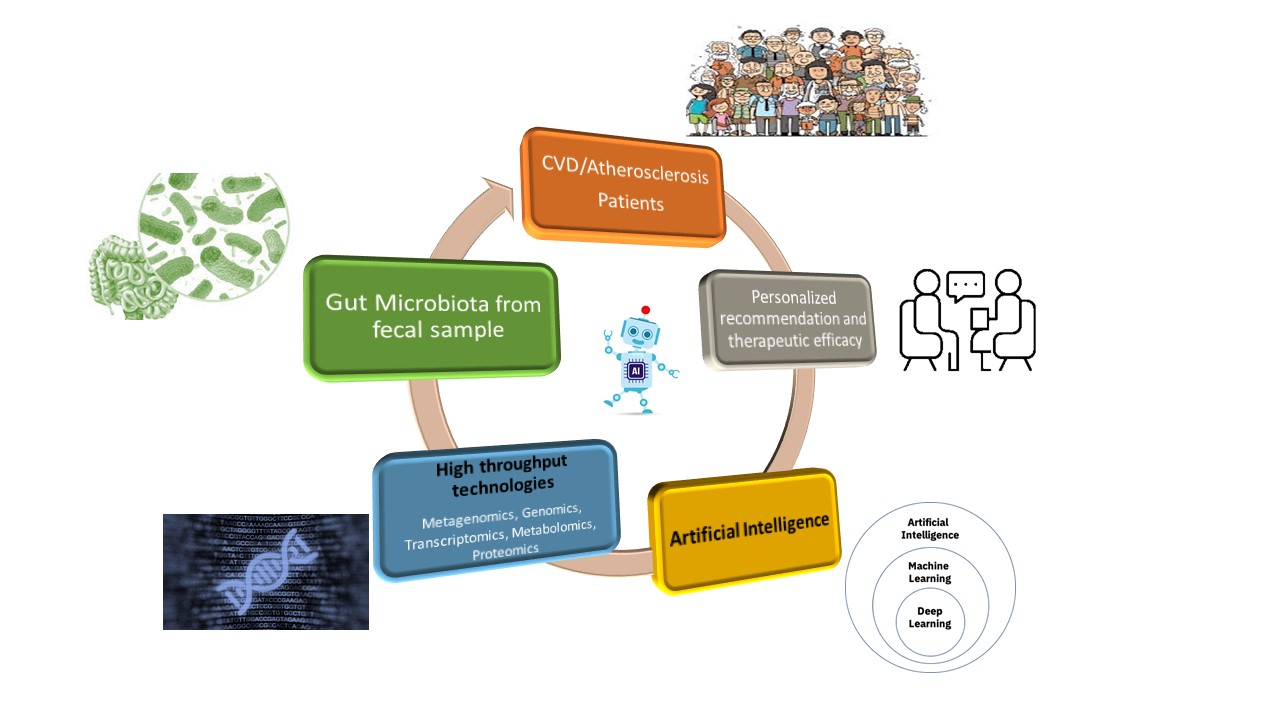

09 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Atherosclerosis Development and Progression

3. AI and ML in Gut Microbiome Analysis: Applications in Disease, and Cardiovascular Health Risk Prediction

3.1. AI and ML for Multi-Dimensional Gut Microbiome Data Analysis and disease prediction

3.2. AI and ML in Predicting Cardiovascular Health and Atherosclerosis Through Gut Microbiome signature

4. Conclusions and Future direction

Supplementary Materials

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; Bonny, A.; Brauer, M.; Brodmann, M.; Cahill, T.J.; Carapetis, J.; Catapano, A.L.; Chugh, S.S.; Cooper, L.T.; Coresh, J.; Criqui, M. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update from the GBD 2019 Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, M.; Zayeri, F.; Salehi, M. Trend Analysis of Cardiovascular Disease Mortality, Incidence, and Mortality-To-Incidence Ratio: Results from Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMC Public Health 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Buring, J.E.; Badimon, L.; Hansson, G.K.; Deanfield, J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Tokgözoğlu, L.; Lewis, E.F. Atherosclerosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Garruti, G.; Liu, M.; Portincasa, P.; Wang, D.Q.-H. . Cholesterol and Lipoprotein Metabolism and Atherosclerosis: Recent Advances in Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Annals of Hepatology 2017, 16, S27–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, P.; Cui, Z.-Y.; Huang, X.-F.; Zhang, D.-D.; Guo, R.-J.; Han, M. Inflammation and Atherosclerosis: Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Intervention. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M.; Bennett, M.R.; Yu, E. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Atherosclerosis. Cells 2022, 11, 3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbrone, M.A.; García-Cardeña, G. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circulation Research 2016, 118, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, A.C.; Meller, N.; McNamara, C.A. Role of Smooth Muscle Cells in the Initiation and Early Progression of Atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2008, 28, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, P.; Cui, Z.-Y.; Huang, X.-F.; Zhang, D.-D.; Guo, R.-J.; Han, M. Inflammation and Atherosclerosis: Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Intervention. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Guan, P.; Majumder, S.; Kaw, K.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, C.; Prakash, S.K.; Kaw, A.; L. Maximillian Buja; Kwartler, C.S.; Milewicz, D.M. Preventing Cholesterol-Induced Perk (Protein Kinase RNA-like Endoplasmic Reticulum Kinase) Signaling in Smooth Muscle Cells Blocks Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology 2022, 42, 1005–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Wright, J.M.; Guan, P.; L Maximilian Buja; Kwartler, C. S.; Milewicz, D.M. Pericentrin Deficiency in Smooth Muscle Cells Augments Atherosclerosis through HSF1-Driven Cholesterol Biosynthesis and PERK Activation. JCI Insight 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaw, K.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Guan, P.; Chen, J.; Majumder, S.; Duan, X.; Ma, S.; Zhang, C.; Kwartler, C.S.; Milewicz, D.M. Smooth Muscle α-Actin Missense Variant Promotes Atherosclerosis through Modulation of Intracellular Cholesterol in Smooth Muscle Cells. European Heart Journal 2023, 44, 2713–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, A.L.; Bäckhed, F. Role of Gut Microbiota in Atherosclerosis. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2016, 14, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trøseid, M.; Andersen, G.Ø.; Broch, K.; Hov, J.R. The Gut Microbiome in Coronary Artery Disease and Heart Failure: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. EBioMedicine 2020, 52, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Li, S.; Li, D.; Cao, J.; Wang, B.; Liang, H.; Zheng, H.; Xie, Y. A Human Gut Microbial Gene Catalogue Established by Metagenomic Sequencing. Nature 2010, 464, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.Y.; Sniffen, S.; McGill Percy, K.C.; Pallaval, V.B.; Chidipi, B. Gut Dysbiosis and Immune System in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ACVD). Microorganisms 2022, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Z.; Xia, H.; Zhong, S.-L.; Feng, Q.; Li, S.; Liang, S.; Zhong, H.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, D.; Su, Z.; Fang, Z.; Lan, Z.; Li, J.; Xiao, L.; Li, J.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Li, F. The Gut Microbiome in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Nature Communications 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Li, L.; Sun, Z.; Zang, G.; Zhang, L.; Shao, C.; Wang, Z. Gut Microbiota and Atherosclerosis—Focusing on the Plaque Stability. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H. ; Jie Ying Lim; Wong, D.; Zhang, S.; Luo, F.; Wang, X.; Sun, C.; Tang, R.; Zheng, W.; Xie, Q. Research Development on Gut Microbiota and Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaque. Heliyon 2024, e25186–e25186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, A.; Satoru Mitomo; Yuki, H. ; Araki, M.; Lena Marie Seegers; McNulty, I.; Lee, H.; Kuter, D.; Ishibashi, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Jouke Dijkstra; Onishi, H.; Hiroto Yabushita; Matsuoka, S.; Kawamoto, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Chou, S.; Naganuma, T.; Masaaki Okutsu. Gut Microbiota and Coronary Plaque Characteristics. Journal of the American Heart Association 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.; Srivatsav, V.; Rizwan, A.; Nashed, A.; Liu, R.; Shen, R.; Akhtar, M. Bridging the Gap between Gut Microbial Dysbiosis and Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients 2017, 9, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, L. Gut Microbiome and Metabolites, the Future Direction of Diagnosis and Treatment of Atherosclerosis? Pharmacological Research 2023, 187, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, H. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Atherosclerosis and Hypertension. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckhed, F.; Fraser, Claire M. ; Ringel, Y.; Sanders, M.; Sartor, R. Balfour; Sherman, Philip M.; Versalovic, J.; Young, V.; Finlay, B. Brett. Defining a Healthy Human Gut Microbiome: Current Concepts, Future Directions, and Clinical Applications. Cell Host & Microbe 2012, 12, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles Alonso, V.; Guarner, F. Linking the Gut Microbiota to Human Health. British Journal of Nutrition 2013, 109, S21–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. Leaky Gut: Mechanisms, Measurement and Clinical Implications in Humans. Gut 2019, 68, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Kirby, J.; Reilly, C.M.; Luo, X.M. Leaky Gut as a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, E.M. M. Leaky Gut – Concept or Clinical Entity? Current Opinion in Gastroenterology 2016, 32, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, F.; Gotteland, M.; Gauthier, L.; Zazueta, A.; Pesoa, S.; Navarrete, P.; Balamurugan, R. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A Relevant Marker of Gut Dysbiosis in Obese Patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, S.J.; El Mokhtari, N.E.; Musfeldt, M.; Hellmig, S.; Freitag, S.; Rehman, A.; KühbacherT. ; Nikolaus, S.; Namsolleck, P.; Blaut, M.; Hampe, J.; Sahly, H.; Reinecke, A.; Haake, N.; GüntherR.; KrügerD.; Lins, M.; Herrmann, G.; FölschU. R.; SimonR. Detection of Diverse Bacterial Signatures in Atherosclerotic Lesions of Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. Circulation 2006, 113, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosos, I.; Tavridou, A.; Kolios, G. New Aspects on the Metabolic Role of Intestinal Microbiota in the Development of Atherosclerosis. Metabolism 2015, 64, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, J.C.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Zhu, W.; Wagner, M.A.; Bennett, B.J.; Li, L.; DiDonato, J.A.; Lusis, A.J.; Hazen, S.L. Transmission of Atherosclerosis Susceptibility with Gut Microbial Transplantation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 2015, 290, 5647–5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludivine Laurans; Mouttoulingam Nirmala; Mouna Chajadine; Bacquer, E. ; Lavelle, A.; Esposito, B.; Alain Tedgui; Hafid Ait Oufella; Zitvogel, L.; Sokol, H.; Taleb, S. Obesogenic Diet Increases Atherosclerosis through Promoting Microbiota Dysbiosis-Induced Gut Lymphocyte Trafficking into Periphery. Archives of cardiovascular diseases 2024, 117, S162–S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Gao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, R.; Jiang, R.; Xu, Y.; Qin, H. Dysbiosis Signatures of Gut Microbiota in Coronary Artery Disease. Physiological Genomics 2018, 50, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baragetti, A.; Severgnini, M.; Olmastroni, E.; Dioguardi, C.C.; Mattavelli, E.; Angius, A.; Rotta, L.; Cibella, J.; Caredda, G.; Consolandi, C.; Grigore, L.; Pellegatta, F.; Giavarini, F.; Caruso, D.; Norata, G.D.; Catapano, A.L.; Peano, C. Gut Microbiota Functional Dysbiosis Relates to Individual Diet in Subclinical Carotid Atherosclerosis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Chen, S.; Gu, G.; Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Ren, J.; Wu, J.; Yang, D.; Zheng, Y. Exploration of Crucial Mediators for Carotid Atherosclerosis Pathogenesis through Integration of Microbiome, Metabolome, and Transcriptome. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ye, L.; Li, J.; Jin, L.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Bao, M.; Wu, S.; Li, L.; Geng, B.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Cai, J. Metagenomic and Metabolomic Analyses Unveil Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota in Chronic Heart Failure Patients. Scientific Reports 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, T.; Wang, P.; Hu, X.; Zheng, L. Probiotics Bring New Hope for Atherosclerosis Prevention and Treatment. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2022, 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadh, M.J.; Bazghandi, B.; Jamialahmdi, H.; Rahimzadeh-Bajgiran, F.; Forouzanfar, F.; Esmaeili, S.-A.; Saburi, E. Therapeutic Potential of Lipid-Lowering Probiotics on the Atherosclerosis Development. European Journal of Pharmacology 2024, 971, 176527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, L.; Centner, A.M.; Salazar, G. Effects of Berries, Phytochemicals, and Probiotics on Atherosclerosis through Gut Microbiota Modification: A Meta-Analysis of Animal Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Morain, V.L.; Ramji, D.P. The Potential of Probiotics in the Prevention and Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2020, 64, e1900797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi-Roshan, M.; Salari, A.; Kheirkhah, J.; Ghorbani, Z. The Effects of Probiotics on Inflammation, Endothelial Dysfunction, and Atherosclerosis Progression: A Mechanistic Overview. Heart, Lung and Circulation 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; Luqman, A.; Zhang, K.; Ullah, M.; Din, A.U.; Xiaoling, L.; Wang, G. Impact of Probiotic Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum ATCC 14917 on Atherosclerotic Plaque and Its Mechanism. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2024, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun Sil Kim; Bo Hyun Yoon; Seung Min Lee; Myoung Hwan Choi; Eun Hye Kim; Lee, B. -W.; Kim, S.; Pack, C.; Young Hoon Sung; Baek, I.-J.; Chang Hee Jung; Kim, T.; Jeong, J.; Chang Hoon Ha. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Ameliorates Atherosclerosis in Mice with C1q/TNF-Related Protein 9 Genetic Deficiency. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2022, 54, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshem, A.; Horesh, N.; Elinav, E. Fecal Microbial Transplantation and Its Potential Application in Cardiometabolic Syndrome. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garshick, M.S.; Nikain, C.; Tawil, M.; Pena, S.; Barrett, T.J.; Wu, B.G.; Gao, Z.; Blaser, M.J.; Fisher, E.A. Reshaping of the Gastrointestinal Microbiome Alters Atherosclerotic Plaque Inflammation Resolution in Mice. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 8966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H.K.; Gudmundsdottir, V.; Nielsen, H.B.; Hyotylainen, T.; Nielsen, T.; Jensen, B.A. H.; Forslund, K.; Hildebrand, F.; Prifti, E.; Falony, G.; Le Chatelier, E.; Levenez, F.; Doré, J.; Mattila, I.; Plichta, D.R.; Pöhö, P.; Hellgren, L.I.; Arumugam, M.; Sunagawa, S.; Vieira-Silva, S. Human Gut Microbes Impact Host Serum Metabolome and Insulin Sensitivity. Nature 2016, 535, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Arze, C.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Schirmer, M.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Poon, T.W.; Andrews, E.; Ajami, N.J.; Bonham, K.S.; Brislawn, C.J.; Casero, D.; Courtney, H.; Gonzalez, A.; Graeber, T.G.; Hall, A.B.; Lake, K.; Landers, C.J.; Mallick, H.; Plichta, D.R.; Prasad, M. Multi-Omics of the Gut Microbial Ecosystem in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nature 2019, 569, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Nayfach, S.; Boland, M.; Strozzi, F.; Beracochea, M.; Shi, Z.J.; Pollard, K.S.; Sakharova, E.; Parks, D.H.; Hugenholtz, P.; Segata, N.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Finn, R.D. A Unified Catalog of 204,938 Reference Genomes from the Human Gut Microbiome. Nature Biotechnology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasolli, E.; Asnicar, F.; Manara, S.; Zolfo, M.; Karcher, N.; Armanini, F.; Beghini, F.; Manghi, P.; Tett, A.; Ghensi, P.; Collado, M.C.; Rice, B.L.; DuLong, C.; Morgan, X.C.; Golden, C.D.; Quince, C.; Huttenhower, C.; Segata, N. Extensive Unexplored Human Microbiome Diversity Revealed by over 150,000 Genomes from Metagenomes Spanning Age, Geography, and Lifestyle. Cell 2019, 176, 649–662.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayfach, S.; Shi, Z.J.; Seshadri, R.; Pollard, K.S.; Kyrpides, N.C. New Insights from Uncultivated Genomes of the Global Human Gut Microbiome. Nature 2019, 568, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sopic, M.; Vilne, B.; Gerdts, E.; Trindade, F.; Uchida, S.; Khatib, S.; Wettinger, S.B.; Devaux, Y.; Magni, P. Multiomics Tools for Improved Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Management. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2023, 29, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, H. Omics Approaches Unveiling the Biology of Human Atherosclerotic Plaques. ˜The œAmerican journal of pathology 2024, 194, 482–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amalie Lykkemark Møller; Vasan, R. S.; Levy, D.; Andersson, C.; Lin, H. Integrated Omics Analysis of Coronary Artery Calcifications and Myocardial Infarction: The Framingham Heart Study. Scientific reports 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, S.; Turner, M.E.; Cao, C. ; Majed Abdul-Samad; Punwasi, N.; Blaser, M.C.; Rachel ME Cahalane; Botts, S.R. C.; Prajapati, K.; Patel, S.; Wu, R.; Gustafson, D.; Galant, N.J.; Fiddes, L.; Chemaly, M.; Hedin, U.; Matic, L.; Seidman, M.; Vallijah Subasri; Singh, S.A. Multi-Omic Landscape of Extracellular Vesicles in Human Carotid Atherosclerotic Plaque Reveals Endothelial Communication Networks. bioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekayvaz, K.; Losert, C.; Viktoria Knottenberg; Gold, C. ; Irene; Oelen, R.; Groot, H.E.; Jan Walter Benjamins; Brambs, S.; Kaiser, R.; Gottschlich, A.; Gordon Victor Hoffmann; Eivers, L.; Martinez-Navarro, A.; Bruns, N.; Stiller, S.; Sezer Akgöl; Yue, K.; Polewka, V.; Escaig, R. Multiomic Analyses Uncover Immunological Signatures in Acute and Chronic Coronary Syndromes. Nature Medicine 2024, 30, 1696–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Luo, H.; Ji, B.; Nielsen, J. Machine Learning for Data Integration in Human Gut Microbiome. Microbial Cell Factories 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beam, A.L.; Kohane, I.S. Big Data and Machine Learning in Health Care. JAMA 2018, 319, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, D.M.; Collins, K.M.; Powers, R.K.; Costello, J.C.; Collins, J.J. Next-Generation Machine Learning for Biological Networks. Cell 2018, 173, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, S.; Sutaoney, P.; Madhyastha, H.; Shah, K.; Chauhan, N.S.; Banerjee, P. Understanding Gut Microbiome-Based Machine Learning Platforms: A Review on Therapeutic Approaches Using Deep Learning. Chemical Biology & Drug Design 2024, 103, e14505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machine Learning for Integrating Data in Biology and Medicine: Principles, Practice, and Opportunities. Information Fusion 2019, 50, 71–91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrieri, A.P.; Haiminen, N.; Maudsley-Barton, S.; Gardiner, L.-J.; Murphy, B.; Mayes, A.E.; Paterson, S.; Grimshaw, S.; Winn, M.; Shand, C.; Hadjidoukas, P.; Rowe, W.P. M.; Hawkins, S.; MacGuire-Flanagan, A.; Tazzioli, J.; Kenny, J.G.; Parida, L.; Hoptroff, M.; Pyzer-Knapp, E.O. Explainable AI Reveals Changes in Skin Microbiome Composition Linked to Phenotypic Differences. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, W.; Ling, C.; He, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Xu, F.; Miao, Z.; Sun, T.; Lin, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, J.-S. Interpretable Machine Learning Framework Reveals Robust Gut Microbiome Features Associated with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2020, 44, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, S.; Alimadadi, A.; Manandhar, I.; Joe, B.; Cheng, X. Machine Learning Strategy for Gut Microbiome-Based Diagnostic Screening of Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Sinha, R.; Shukla, P. Artificial Intelligence and Synthetic Biology Approaches for Human Gut Microbiome. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topçuoğlu, B.D.; Lesniak, N.A.; Ruffin, M.T.; Wiens, J.; Schloss, P.D. A Framework for Effective Application of Machine Learning to Microbiome-Based Classification Problems. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri-Rosario, D.; Martínez-López, Y.E.; Esquivel-Hernández, D.A.; Sánchez-Castañeda, J.P.; Padron-Manrique, C.; Vázquez-Jiménez, A.; Giron-Villalobos, D.; Resendis-Antonio, O. Dysbiosis Signatures of Gut Microbiota and the Progression of Type 2 Diabetes: A Machine Learning Approach in a Mexican Cohort. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2023, 14, 1170459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, H.; Nishida, A.; Matsuda, S.; Kira, F.; Watanabe, S.; Kuriyama, M.; Kawakami, K.; Aikawa, Y.; Oda, N.; Arai, K.; Matsunaga, A.; Nonaka, M.; Nakai, K.; Shinmura, W.; Matsumoto, M.; Morishita, S.; Takeda, A.K.; Miwa, H. Usefulness of Machine Learning-Based Gut Microbiome Analysis for Identifying Patients with Irritable Bowels Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 9, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacılar, H.; Nalbantoğlu, O.U.; Bakir-Güngör, B. Machine Learning Analysis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Associated Metagenomics Dataset. IEEE Xplore. [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Zambrano, L.J.; Karaduzovic-Hadziabdic, K.; Loncar Turukalo, T.; Przymus, P.; Trajkovik, V.; Aasmets, O.; Berland, M.; Gruca, A.; Hasic, J.; Hron, K.; Klammsteiner, T.; Kolev, M.; Lahti, L.; Lopes, M.B.; Moreno, V.; Naskinova, I.; Org, E.; Paciência, I.; Papoutsoglou, G.; Shigdel, R. Applications of Machine Learning in Human Microbiome Studies: A Review on Feature Selection, Biomarker Identification, Disease Prediction and Treatment. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnicar, F.; Thomas, A.M.; Passerini, A.; Waldron, L.; Segata, N. Machine Learning for Microbiologists. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A.L.; Muehlbauer, A.L.; Alazizi, A.; Burns, M.B.; Findley, A.; Messina, F.; Gould, T.J.; Cascardo, C.; Pique-Regi, R.; Blekhman, R.; Luca, F. Gut Microbiota Has a Widespread and Modifiable Effect on Host Gene Regulation. mSystems 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Chen, J.; Kim, J.; Pan, W. An Adaptive Association Test for Microbiome Data. Genome Medicine 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Li, B.; He, T.; Li, G.; Jiang, X. Robust Biomarker Discovery for Microbiome-Wide Association Studies. Methods (San Diego, Calif.) 2020, 173, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laterza, L.; Putignani, L.; Settanni, C.R.; Petito, V.; Varca, S.; De Maio, F.; Macari, G.; Guarrasi, V.; Gremese, E.; Tolusso, B.; Wlderk, G.; Pirro, M.A.; Fanali, C.; Scaldaferri, F.; Turchini, L.; Amatucci, V.; Sanguinetti, M.; Gasbarrini, A. Ecology and Machine Learning-Based Classification Models of Gut Microbiota and Inflammatory Markers May Evaluate the Effects of Probiotic Supplementation in Patients Recently Recovered from COVID-19. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xu, C. Handling High-Dimensional Data with Missing Values by Modern Machine Learning Techniques. Journal of Applied Statistics 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, Y.; Okumura, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Itatani, Y.; Nishiyama, T.; Okazaki, Y.; Shibutani, M.; Ohtani, N.; Nagahara, H.; Obama, K.; Ohira, M.; Sakai, Y.; Nagayama, S.; Hara, E. Development and Evaluation of a Colorectal Cancer Screening Method Using Machine Learning-Based Gut Microbiota Analysis. Cancer Medicine 2022, 11, 3194–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeil, J.; Siptroth, J.; Pospisil, H.; Frohme, M.; Hufert, F.T.; Moskalenko, O.; Murad Yateem; Nechyporenko, A. Classification of Microbiome Data from Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Individuals with Deep Learning Image Recognition. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2023, 7, 51–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango-Argoty, G.; Garner, E.; Pruden, A.; Heath, L.S.; Vikesland, P.; Zhang, L. DeepARG: A Deep Learning Approach for Predicting Antibiotic Resistance Genes from Metagenomic Data. Microbiome 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Syama; Arul, A.; Khanna, N. Automatic Disease Prediction from Human Gut Metagenomic Data Using Boosting GraphSAGE. BMC bioinformatics 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshrit Shtossel; Isakov, H. ; Turjeman, S.; Koren, O.; Yoram Louzoun. Ordering Taxa in Image Convolution Networks Improves Microbiome-Based Machine Learning Accuracy. Gut Microbes 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Guo, Z.; Xia, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Tang, N.; Tong, X.; Wang, M.; Ye, X.; Feng, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Identification of Antimicrobial Peptides from the Human Gut Microbiome Using Deep Learning. Nature Biotechnology 2022, 40, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Jo, J.-H.; Zhang, Z.; MacGibeny, M.A.; Han, J.; Proctor, D.M.; Taylor, M.E.; Che, Y.; Juneau, P.; Apolo, A.B.; McCulloch, J.A.; Davar, D.; Zarour, H.M.; Dzutsev, A.K.; Brownell, I.; Trinchieri, G.; Gulley, J.L.; Kong, H.H. Predicting Cancer Immunotherapy Response from Gut Microbiomes Using Machine Learning Models. Oncotarget 2022, 13, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Y.; Yue, J.; He, J.; Liu, G. Integrating Machine Learning Algorithms and Single-Cell Analysis to Identify Gut Microbiota-Related Macrophage Biomarkers in Atherosclerotic Plaques. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmbrunn, M.V. ; U Boulund; J Aron-Wisnewsky; de, C.; Abeka, R.E.; Davids, M.; Bresser, L.R. F.; Levin, E.; Clement, K.; H Galenkamp; Ferwerda, B.; van; A Kurilshikov; Fu, J.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Soeters, M.R.; Raalte, van; Herrema, H.; Groen, A.K.; M Nieuwdorp. Networks of Gut Bacteria Relate to Cardiovascular Disease in a Multi-Ethnic Population: The HELIUS Study. Cardiovascular research 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, D.; Jia, W.; Wang, W.; Liao, L.; Xu, B.; Gong, L.; Dong, H.; Zhong, L.; Yang, J. Causality of the Gut Microbiome and Atherosclerosis-Related Lipids: A Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Study. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menglei Shuai; Zuo, L. -S.-Y.; Miao, Z.; Gou, W.; Xu, F.; Jiang, Z.; Ling, C.; Fu, Y.; Xiong, F.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, J.-S. Multi-Omics Analyses Reveal Relationships among Dairy Consumption. Gut Microbiota and Cardiometabolic Health. 2021, 66, 103284–103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, R.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Fan, Y.; Shi, Y.; Qiao, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S. Multi-Omics Study Reveals That Statin Therapy Is Associated with Restoration of Gut Microbiota Homeostasis and Improvement in Outcomes in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5778–5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappel, B.A.; De Angelis, L.; Heiser, M.; Ballanti, M.; Stoehr, R.; Goettsch, C.; Mavilio, M.; Artati, A.; Paoluzi, O.A.; Adamski, J.; Mingrone, G.; Staels, B.; Burcelin, R.; Monteleone, G.; Menghini, R.; Marx, N.; Federici, M. Cross-Omics Analysis Revealed Gut Microbiome-Related Metabolic Pathways Underlying Atherosclerosis Development after Antibiotics Treatment. Molecular Metabolism 2020, 36, 100976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Pushpakumar, S.B.; Hebah Almarshood; Ouseph, R. ; Gondim, D.D.; Jala, V.R.; Sen, U. Toll-like Receptor 4 Mutation Mitigates Gut Microbiota-Mediated Hypertensive Kidney Injury. Pharmacological Research 2024, 206, 107303–107303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, H.; Hernyes, A.; Marton Piroska; Balázs Ligeti; Fussy, P. ; Luca Zoldi; Szonja Galyasz; Nóra Makra; Dóra Szabó; Ádám Domonkos Tárnoki; Dávid László Tárnoki. Association between Gut Microbial Diversity and Carotid Intima-Media Thickness. Medicina-lithuania 2021, 57, 195–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gérard, P. Diet-Gut Microbiota Interactions on Cardiovascular Disease. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2022, 20, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.; O’Donovan, A.N.; Caplice, N.M.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Exploring the Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease. Metabolites 2021, 11, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).