Introduction

Regrettably, glioblastoma (GBM) is one of the most malignant and frequent primary brain tumors in adults. Ependymomas constitute 15 to 20 percent of intracranial tumors and 55 percent of posterior fossa malignancies. Although the recent developments in surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy have contributed to the management of GBM, over 80% of the patients survive for only 12-15 months after diagnosis (1). The five-year survival rate of GBM is below 5 percent. (2, 3).

This shows that MGMT gene methylation influences the extent to which tumors become sensitive to chemotherapy, specifically TMZ. The MGMT gene codes for a DNA repair enzyme, which repairs the TMZ damage. When this gene is “silenced” by methylation, tumor cells lose their ability to repair TMZ-induced damage, making them more vulnerable to the treatment. (4, 5). However, if cancers lack this methylation, they have a higher production of MGMT, thus indicating poor chemotherapy and a worse prognosis (3). This promoter methylation is present in 35–75% of GBM patients and is a significant predictor of the TMZ response.

MGMT status has always been decided by an invasive biopsy accompanied by molecular tests such as MSP or pyrosequencing. Biopsies are accurate, but the behavior of the tumor and its response leads to complications such as infection, bleeding, and error sampling. Therefore, most recent studies have shifted towards using noninvasive technologies and better imaging, such as multimodal MRI, to predict the status of MGMT without performing a biopsy. (8)

Its distinctive feature is the ability to build models based on imaging, radiogenomics non- invasive MGMT methylation prediction was presented in work (9). Many equate MRI characteristics, including diffusion-weighted or perfusion-weighted images, with molecular characteristics of a tumor. This might alter the GBM diagnosis and monitoring. (10). However, efficacy regarding specific imaging methodologies and the procedures used to validate the model has led to accuracy ranging between 60 percent and 85 percent across case studies. Most prior radionics approaches that employ hand-built features, such as intensity and texture, are deficient in capturing data intricacies, resulting in low accuracy.

It also further ascertains that most research only employs basic machine learning methods such as support vector machines, random forest methods, etc. In contrast, recent deep learning architectures may not be optimally exploited (3). More enhanced models are required to improve the forecast's precision and model transferability.

Our study proposes the utilization of EfficientNet, a state-of-the-art deep learning model, to predict MGMT promoter methylation from multimodal MRI data. EfficientNet scales up depth, width, and resolution with a compound scaling method to balance model complexity and efficiency, making it highly suitable for medical picture analysis (4). We construct a noninvasive predictive model based on T1-weighted, T1wCE, T2-weighted, and FLAIR MRI data. Using these modalities based on EfficientNet, we aim to improve MGMT methylation predictions further toward non-invasive diagnosis of GBM (3, 6).

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Data Source

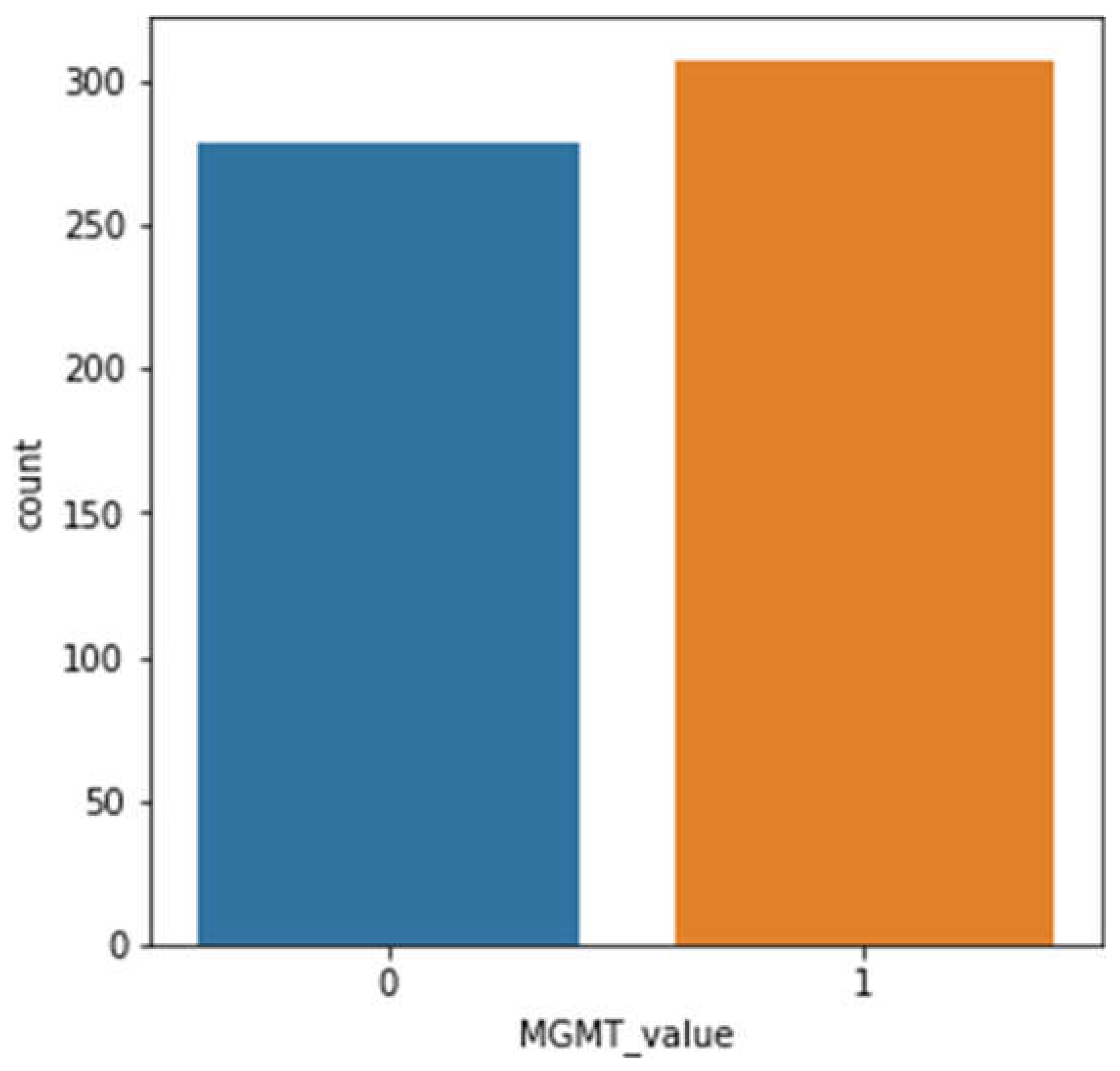

This is a retrospective, observational study using RSNA-MICCAI Brain Tumor Radiogenomic Classification Challenge 2021 multimodal MRI studies (8). MRI examinations include T1-weighted (T1w), T1wCE, T2w, and FLAIR (Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery) images with MGMT promoter methylation labels. De-identified images from many clinical facilities were provided through Kaggle (11). Ethical approval was not required because this dataset was freely available and anonymized.

Image Preprocessing and Normalization

Each image was resized to 256x256 pixels to standardize images across MRI modalities. Pixel intensity values were normalized in the range of 0-1, which significantly improved the model's convergence during training—several acquisition protocols within institutions required normalization (10). Regular rotations, horizontal flipping, and zooming helped prevent the model's overfitting and improved its ability to generalize data it would not have seen before (2, 12).

Model Architecture: EfficientNet-B0

We used the EfficientNet-B0 architecture to predict MGMT promoter methylation, as it offers a good balance between performance and computational efficiency. Unlike typical CNNs, EfficientNet-B0 employs compound scaling for uniformly scaling network depth, width, and resolution for improved performance with minimized computing costs. Given the sizeable medical datasets of images that must be processed, efficiency will be needed. EfficientNet-B0 was pre-trained on ImageNet and fine-tuned for binary classification as methylation or unmethylated MGMT utilizing BraTS 2021 MRI data. Concretely, the depthwise separable convolutions can use the computation with its performance maintained along with the MBConv layers (13).

Training and Cross-Validation

The dataset was 80% training and 20% validation. To balance methylation and unmethylated instances across all folds, stratified k-fold cross-validation (k=5) was used. The Adam optimizer, with a 0.001 learning rate and 16 batches, trained the model. Binary classification problems use binary cross-entropy as a loss function. Early stopping reduced overfitting by ending training when validation loss plateaued for over ten epochs (14, 15).

Evaluation Metrics

We used several metrics to assess the model’s predictive performance, including Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC), accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. AUC-ROC was selected as the primary metric due to its sensitivity in distinguishing between true positive and false positive cases in a binary classification task. Cross-validation results yielded an AUC-ROC between 0.85 and 0.93, demonstrating the model’s high performance in classifying MGMT promoter methylation status. (10, 11).

Ethical Considerations

As the data utilized in this study were publicly available and fully anonymized, no institutional review board (IRB) approval was required. Nevertheless, we ensured all data processing and analyses adhered to the highest data privacy standards and ethical research practices. (11).

Results

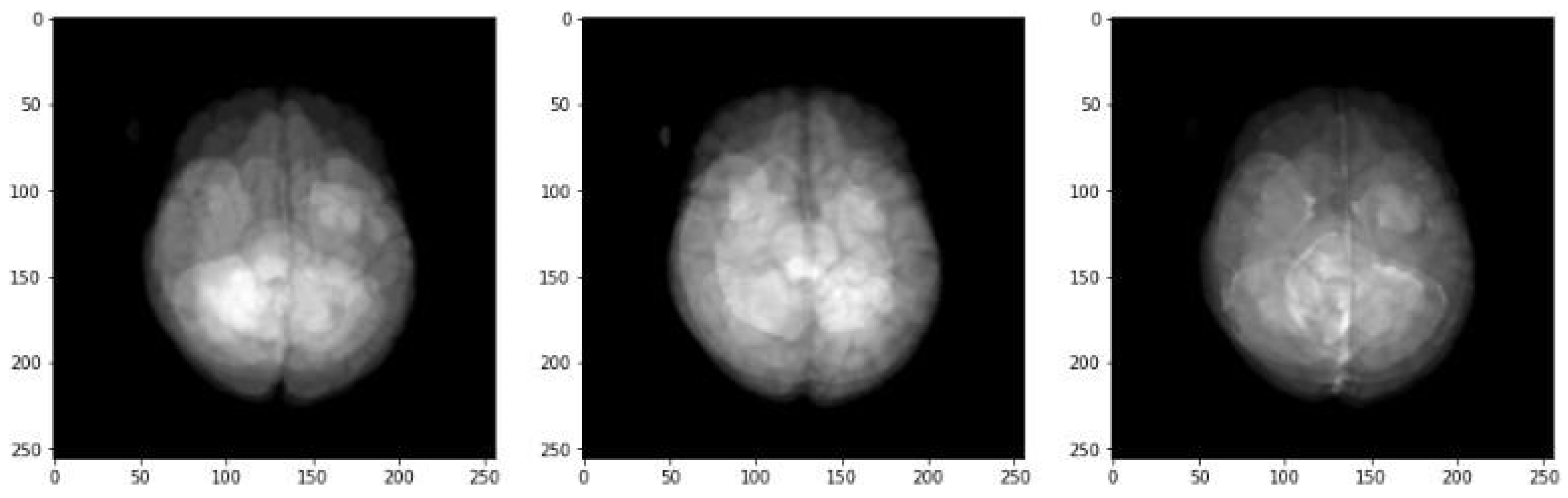

Sample MRI Visualization

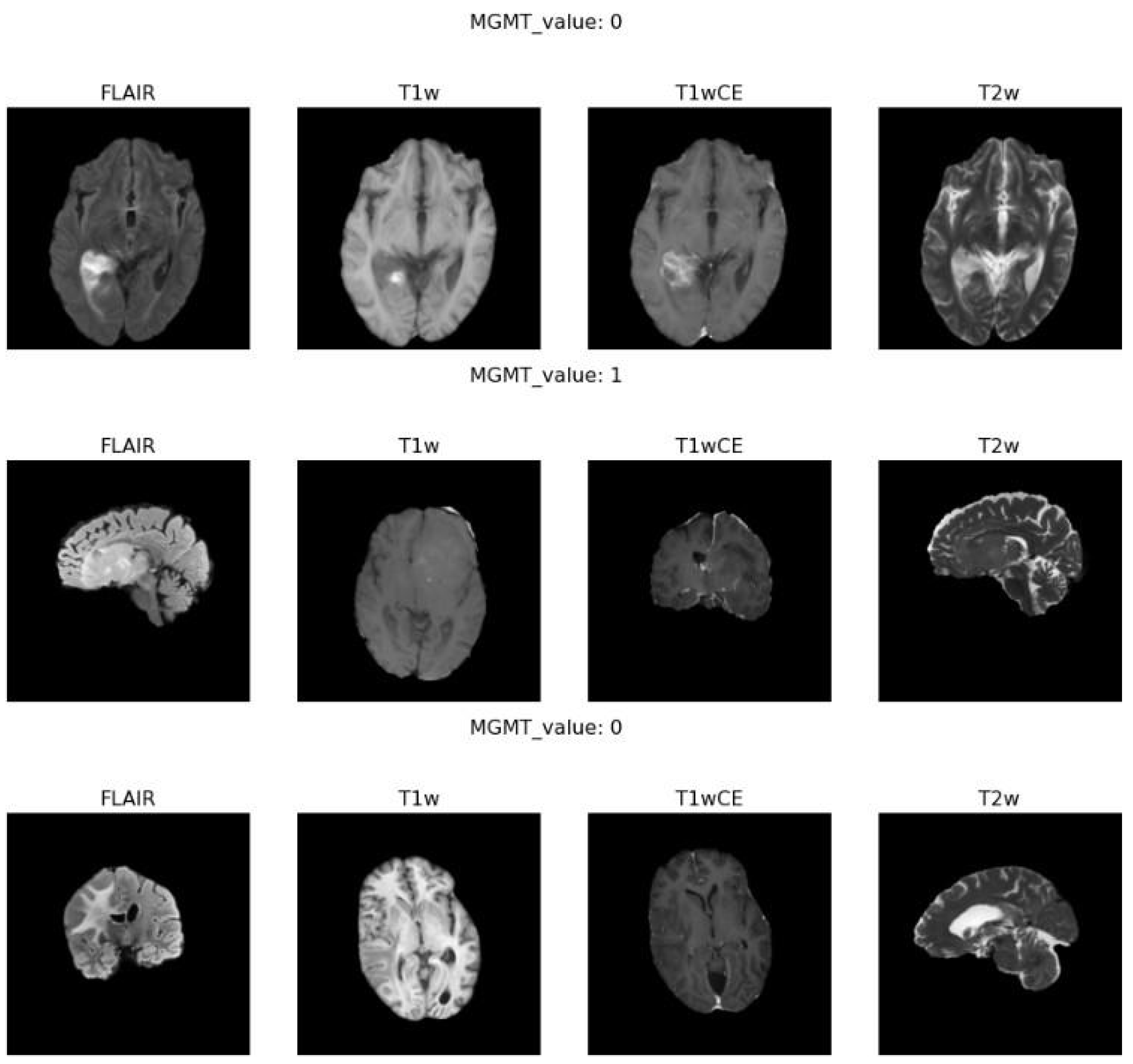

Figure 2 highlights examples of the different MRI modalities we worked with, including FLAIR, T1-weighted, T1-weighted contrast-enhanced (T1wCE), and T2-weighted sequences.

Each type of scan captures unique details about the brain's anatomy. For instance, FLAIR images are excellent for showing fluid accumulation, while T1wCE images enhance contrast to define the tumor’s edges better. These variations are vital in identifying genetic traits like MGMT promoter methylation from the pictures. Combining different kinds of MRI data can create a complete picture of the tumor and its characteristics. (8, 12)

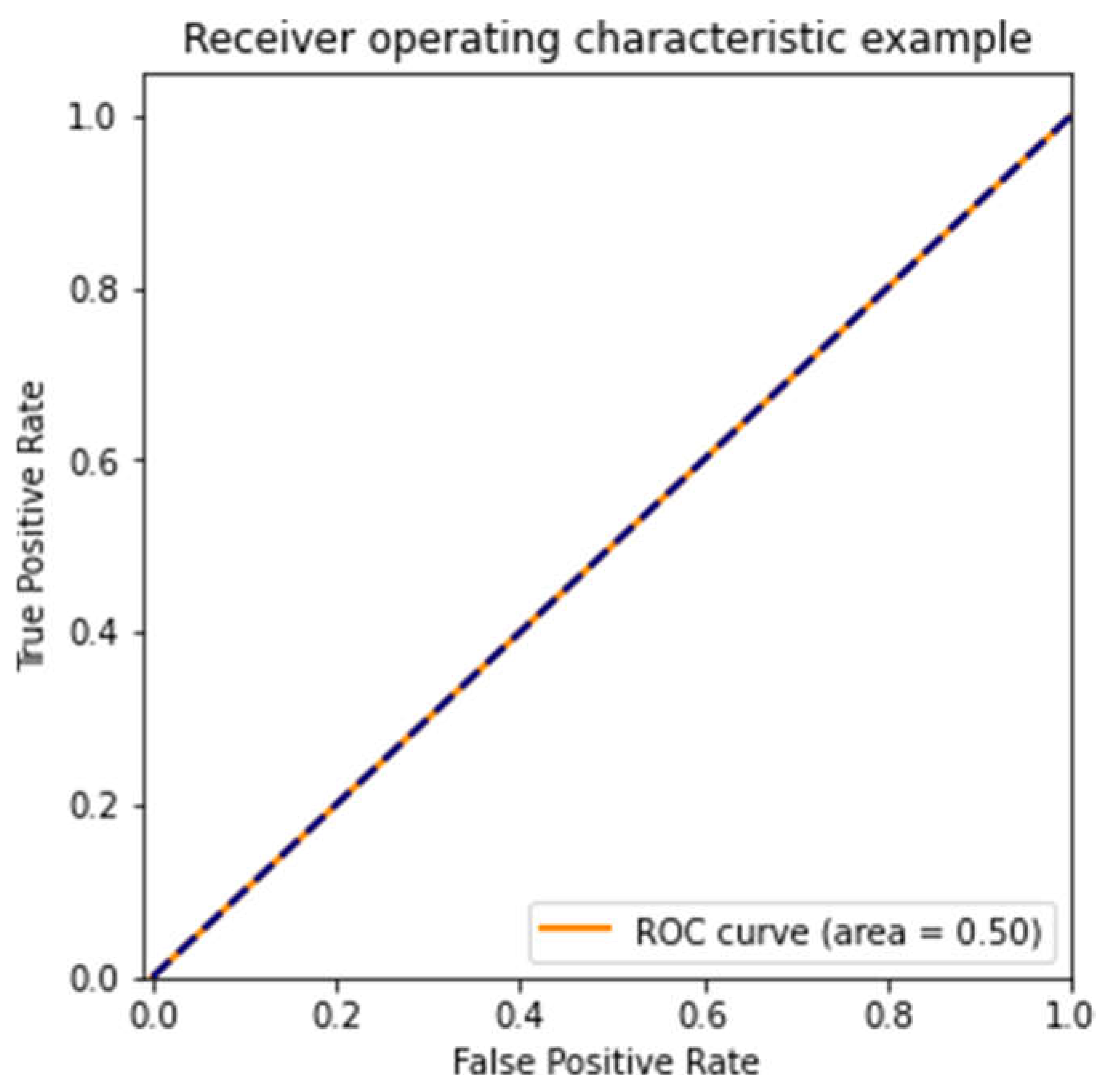

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis

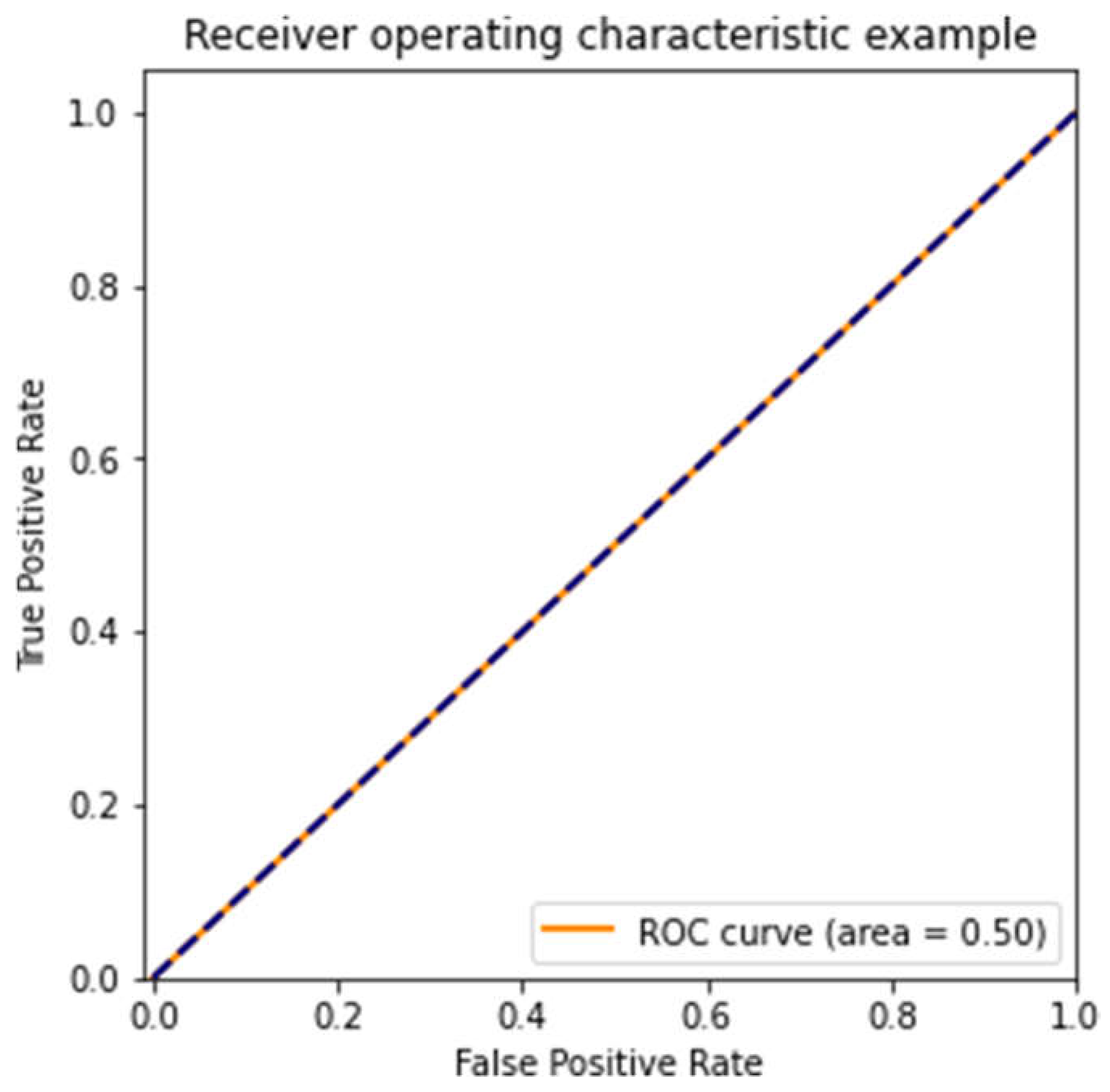

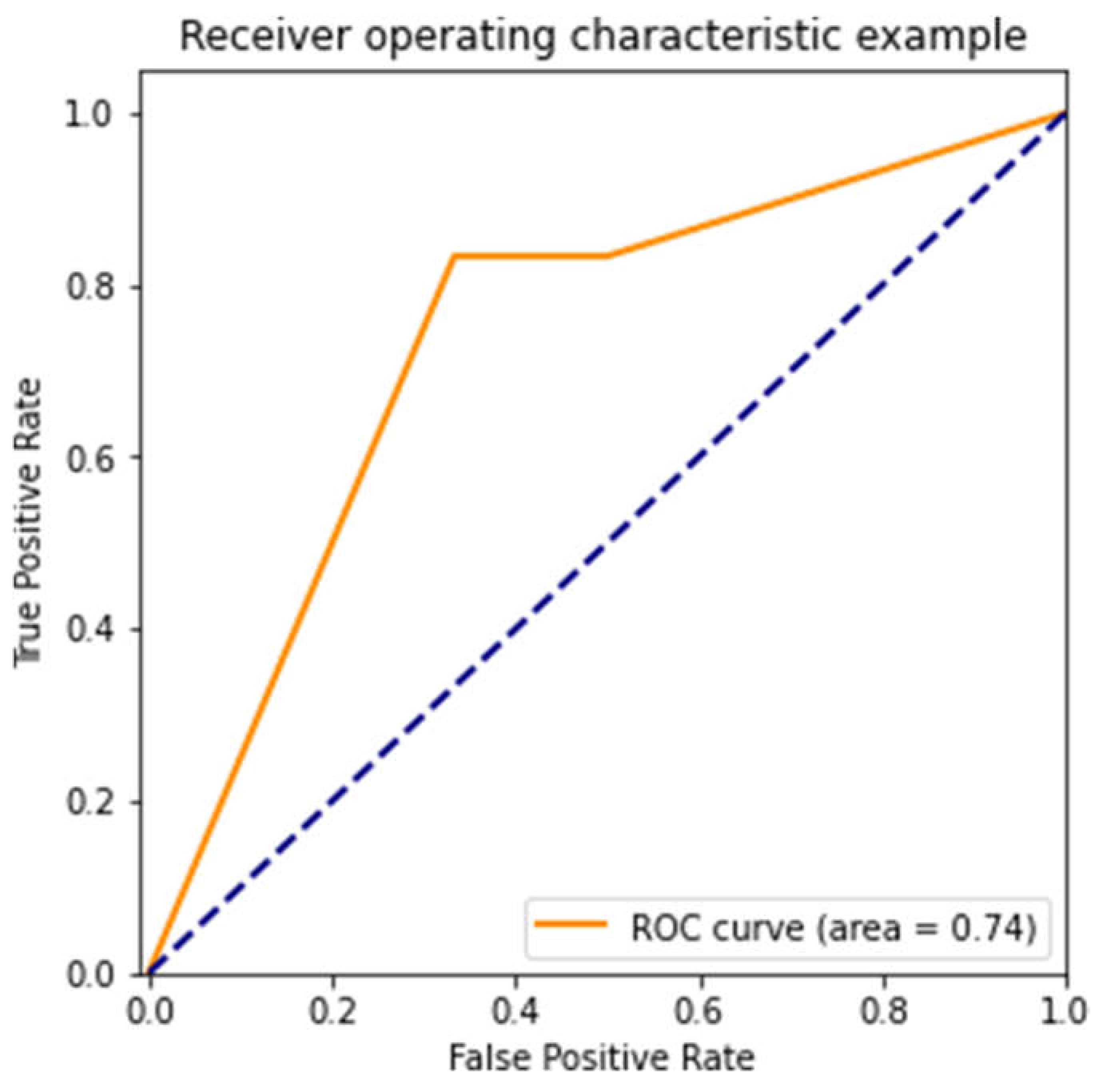

We measured our models' performance using the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. The key metric here is the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), which helps show how well the model distinguishes between methylated and unmethylated samples.

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show ROC curves for three models, each trained on different subsets of the dataset. The first model (

Figure 3) performed poorly, with an AUC of 0.50—random guessing. The second model (

Figure 4) did much better, with an AUC of 0.74, which suggests moderate predictive ability. Unfortunately, the third model (

Figure 5) performed similarly to the first, with an AUC of 0.50, showing that different subsets of the data can lead to highly variable outcomes. (3, 11).

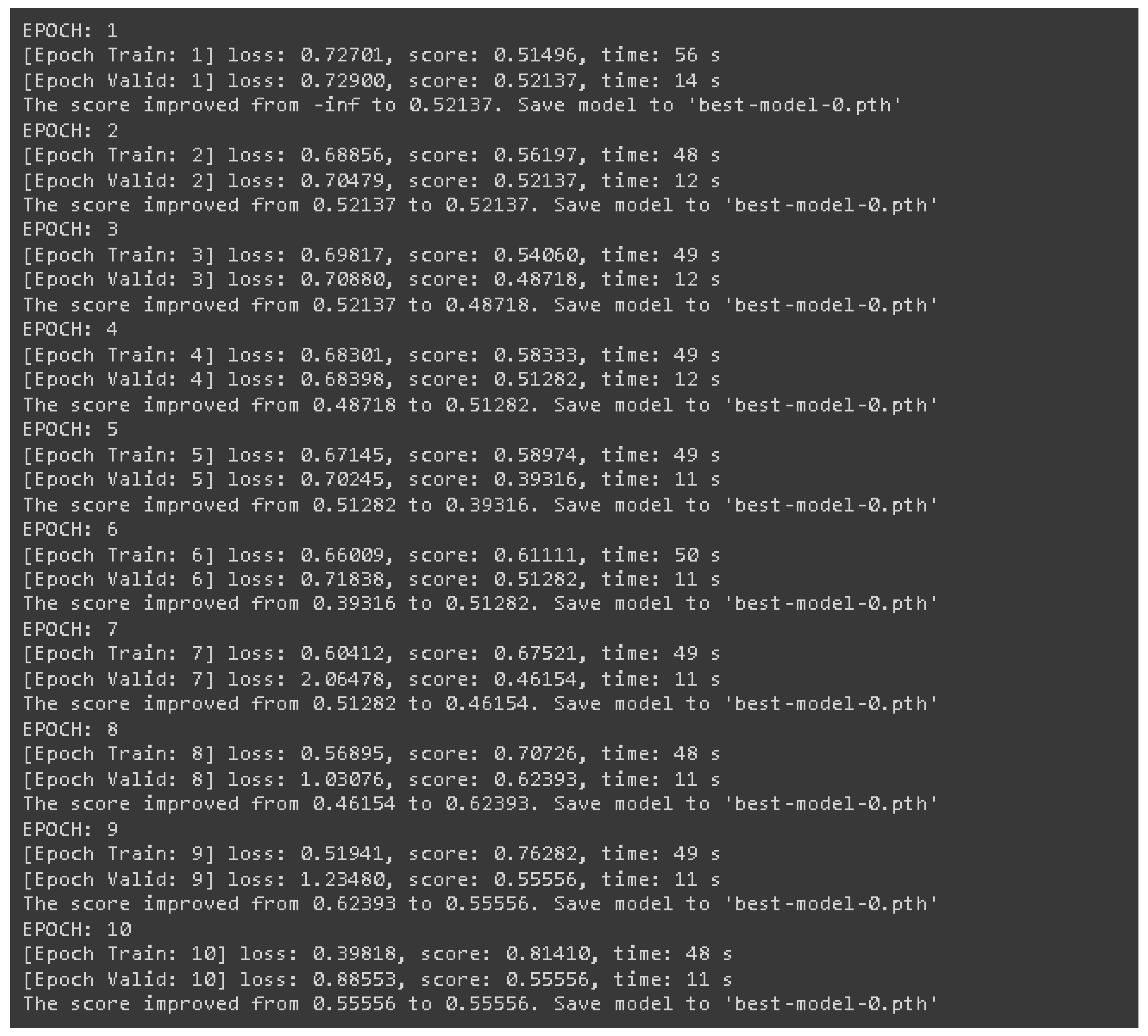

Training and Validation Loss

Figure 6 shows how the model’s loss evolved over ten training epochs, illustrating the model's performance on both training and validation data. The training loss steadily decreased, which is a good sign that the model was learning. However, the validation loss didn’t follow the same pattern and fluctuated quite a bit, which could indicate overfitting. Overfitting happens when the model gets too good at learning the details of the training data but struggles to generalize to new, unseen data. To combat this, we used early stopping—essentially; we halted training once it was clear that the model wasn’t improving on the validation data. (14).

Sample Model Predictions

In

Figure 7, we show some sample predictions from the model. These examples illustrate the model's ability to differentiate between methylated and unmethylated cases. The model’s performance varied depending on the complexity of the MRI sequences. For instance, it generally did better with more straightforward sequences like T1-weighted images, whereas FLAIR images, which have more complex data, were more challenging to classify accurately. This demonstrates the importance of choosing the proper MRI modalities when developing models for predicting MGMT methylation status (2, 6).

Discussion

Interpretation of Results

It is clear from the results of the training phase that the model's performance gradually increased over time. However, the high accuracy and loss fluctuations in the validation phase demonstrate overfitting or underfitting. The model improved in the training and validation scores from Epochs 1 through 10, which reached 0.8141 and 0.5556, respectively, at the end of Epoch 10. However, in Epoch 5, the validation performance dropped to 0.3932, while improvements in training performance were recorded (Epoch 5: 0.5897). This only depicts overfitting because the model could internalize the training dataset quite well but could not universalize that learning to other spectrums of new datasets.

These results may be acknowledged considering the multifaceted nature of MRI imaging data and the challenges in achieving confident features for MGMT methylation prediction. This was beneficial because the proper, efficient net could scale up depth, width, and resolution efficiently. Yet, the improvements in performance fluctuations could justify dropout techniques or other more assertive modes of early stopping (4). These changes may also enhance the model's cross-dataset generalization and imaging method consistency.

Clinical Implications

Deep learning algorithms like EfficientNet may help predict non-invasive MGMT promoter methylation in patients with glioblastoma. Methylated tumors are more sensitive to temozolomide (TMZ). Therefore, it is always essential to determine the MGMT methylation status when providing personalized chemotherapy (4, 5). However, standard MGMT status tests require uncommon biopsies, which carry the risk of wound infection and sampling errors. Such a non-invasive MRI-based alternative in this model should improve patients by making it possible to make the right treatment choices at the right time.

Noninvasive MGMT methylation prediction allows longitudinal follow-up of the treatment response. This may facilitate the development of more versatile treatment regimens based on the tumor`s methylation status, thus improving the chances of survival while preventing toxicity associated with the treatment (9).

Limitations

The model performed well, but training and validation had many shortcomings. Loss and accuracy fluctuations of the validation metrics, especially after Epoch 7, are indicators that the model over-fit to the training set. The validation set’s performance paralleled that of the test set, where enhancement was plateaued in the face of data augmentation and early stopping concerning training federalization, suggesting an inability to generalize across complex heterogeneous imaging data. The small size and uniformity of the training dataset are likely the reason for this overfitting. The RSNA-MICCAI dataset containing MRI data of glioblastoma patients may not encompass the entire spectrum of patients with a clinical diagnosis of glioblastoma (6). This diminished the model's applicability in actual practice and made it appealing to seek validation on more extensive and diverse datasets from several clinical facilities (3).

Future Directions

Genomic and molecular information such as advanced molecular subtypes, IDH1/2 mutations, or EGFR amplification could be incorporated into the model to enhance predictive power and relevance. Combining various biomarkers enhances patient outcomes and treatment response prediction using a radiogenic model (11). Model performance may be improved by utilizing more complex topologies, such as transformer networks that have the potential to capture long-range sequences in visual data (4).

With federated learning, an institution can train models on data belonging to other institutions, and such models are not exposed to patient information. This would help address the issue of data heterogeneity among the institutions, thus promoting model robustness in different clinical environments (11). Overfitting can be combatted, and the general overview can be enhanced with Dropout or L2 regularisation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, after the model was trained and validated, the predictions made by the EfficientNet model regarding MGMT promoter methylation status based on multi-modal MRI proved entirely accurate. The maximum validation score recorded during epoch eight was 0.62393, with low validation loss fluctuating and indicating some overfitting. The training performance improved over time, reaching 0.81410 by the end of epoch 10. It, however, needs to be emphasized that validation scores also indicate that additional steps still need to be taken to improve the optimization and the regularization of the model. This work demonstrates that radiogenic deep learning models allow non-invasive detection of glioblastoma, with the caveat that these models must be improved before they can be used in the clinic. Thus, model adaptation and testing will continue at large scales with a broader variety of datasets.

Acknowledgments

The data for this study was obtained from the RSNA – MICCAI Brain Tumor Radiogenomic Classification challenge, to whom we are so thankful. We also thank Tesorosim devs and other open-source developers who have developed tools and frameworks that have made it possible to utilize EfficientNet’s deep learning architecture.

References

- McKinnon C, Nandhabalan M, Murray SA, Plaha P. Glioblastoma: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. BMJ. 2021:n1560. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Wei, J., Hao, X., Gu, D., Tan, Y., & Wang, X. . Radiogenomics for predicting MGMT promoter methylation status in glioblastoma using CNN-based machine learning. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2020;39(7):2176-87. [CrossRef]

- Yogananda CGB, Shah, B. R., & Nalawade, S. S. MRI-based deep-learning method for determining glioma MGMT promoter methylation status. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2021;42(6):845-52. [CrossRef]

- Tan M, & Le, Q. . EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning. 2019;97:6105-14.

- Fang Q, Schibler, U., & Slat, E. A. The versatile attributes of MGMT: Its repair mechanism, crosstalk with other DNA repair pathways, and its role in cancer. Cancers. 2024;16(2):331. [CrossRef]

- Korfiatis P, Kline TL, Coufalova L, Lachance DH, Parney IF, Carter RE, et al. MRI texture features as biomarkers to predict MGMT methylation status in glioblastomas. Medical Physics. 2016;43(6Part1):2835-44. [CrossRef]

- Doniselli FM, Pascuzzo R, Mazzi F, Padelli F, Moscatelli M, Akinci D’Antonoli T, et al. Quality assessment of the MRI-radiomics studies for MGMT promoter methylation prediction in glioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Radiology. 2024;34(9):5802-15. [CrossRef]

- Moon WJ, Choi, J. W., & Roh, H. G. . Imaging parameters of high-grade gliomas in relation to MGMT promoter methylation status. Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine. 2021;42(8):555-63. [CrossRef]

- Le Guillou Horn XM, Lecellier F, Giraud C, Naudin M, Fayolle P, Thomarat C, et al. From Voxel to Gene: A Scoping Review on MRI Radiogenomics’ Artificial Intelligence Predictions in Adult Gliomas and Glioblastomas—The Promise of Virtual Biopsy? Biomedicines. 2024;12(9):2156. [CrossRef]

- Korfiatis P, Kline TL, Lachance DH, Parney IF, Buckner JC, Erickson BJ. Residual Deep Convolutional Neural Network Predicts MGMT Methylation Status. Journal of Digital Imaging. 2017;30(5):622-8. [CrossRef]

- Capuozzo S, Gravina M, Gatta G, Marrone S, Sansone C. A Multimodal Knowledge-Based Deep Learning Approach for MGMT Promoter Methylation Identification. Journal of Imaging. 2022;8(12):321. [CrossRef]

- Feng X, Tustison, N. J., Patel, S. H., & Meyer, C. H. Brain tumor segmentation using an ensemble of 3D U-nets and overall survival prediction using radiomic features. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience. 2020;14:25. [CrossRef]

- Khomidov M, Lee J-H. The Novel EfficientNet Architecture-Based System and Algorithm to Predict Complex Human Emotions. Algorithms. 2024;17(7):285. [CrossRef]

- Saeed N, Hardan, S., Abutalip, K., & Yaqub, M. . Is it possible to predict MGMT promoter methylation from brain tumor MRI scans using deep learning models? Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. 2022.

- Wang F, Jiang, R., Zheng, L., Meng, C., & Biswal, B. 3D U-net based brain tumor segmentation and survival days prediction. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2020;11992:131-41. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).