1. Introduction

Since their creation, contact lenses (CLs) have found various evolutions regarding their material, fabrication process, and optical designs, which extended the application possibilities, ranging from vision correction to aesthetic and therapeutic uses [

1,

2,

3]. In particular, the most used CL materials are soft CLs [

2], with a global market size of

$9.5 billion in 2022 [

4].

Soft CLs are made of either hydrogel (Hy) or silicone hydrogel (SiHy), offering numerous advantages such as enhanced comfort and compatibility with the eye due to their high water content [

5]. SiHy CLs provide superior oxygen permeability (until 172 Fatt units) to the eye thanks to their silicon-oxygen (Si-O) structural bond [

2,

6]. Maintaining adequate oxygen levels in the cornea is essential to preventing one of the most common complications associated with soft CLs: corneal hypoxia-oxygen deprivation of the cornea, which can manifest as red eye, corneal swelling, and corneal vascularization [

3,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The introduction of SiHy CLs has been instrumental in addressing a significant portion of this issue [

5,

14]. However, they have not fully resolved many other challenges CL wearers face

. Indeed

, the presence of silicone also has drawbacks as it enhances the hydrophobicity and rigidity of the hydrogel, as well as lipid deposition [

15], which promotes inflammation, discomfort, and dryness that are the reasons for CL wear discontinuation [

16,

17]. On the contrary, the Hy CLs, present a lower oxygen permeability (below 60 Fatt units) [

6], facilitating corneal infection and, thus, corneal infiltration events [

18].

In this context, the effort to improve the properties of Hy CLs has been more limited than with the SiHy CLs. Thus, several authors have evaluated the possibility of enhancing the oxygen pass through SiHy CLs by changes in their components (e.g., silicone monomers [

19] or particles [

20,

21], plasticizers [

22], and crosslinkers [

23,

24])

. Regarding Hy CLs, the literature links the oxygen passing through them to their water content (WC). Hence, to calculate their Dk based on lens WC, several equations have been proposed [

25,

26] and applied in several CL works [

11,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Nevertheless, the ISO standards do not recommend using these equations [

35]

. In alignment with these recommendations, Chirila [

36] asserted that it is essential to determine experimentally the oxygen permeability because those equations focus only on synthetic hydrogels commonly employed in silicone-free CL manufacturing.

In the present work, we have aimed to optimize the oxygen permeability (Dk) of non-silicone hydrogel CLs, using a component commonly used in the CL industry to maintain the cohesiveness of the polymer network, the crosslinker agent. Several studies highlighted the crosslinker’s impact on the properties of the hydrogels [

37]

. Hence, we have evaluated its ability to modulate oxygen permeability and other chemical, optical, and mechanical properties of non-silicone hydrogel CLs. More specifically, we have studied the impact of various lengths and concentrations of ethylene glycol dimethacrylate crosslinker on a mixture of N, N-Dimethylacrylamide, and Cyclohexyl methacrylate monomers. This work highlights the strong effect of crosslinker modifications on the oxygen permeability of non-silicone CLs. It demonstrates, for the first time to our knowledge, that, in addition to water, other usual hydrogel components, like crosslinkers, can modulate the Dk of non-silicone contact lenses. Furthermore, it provides a simple and scalable method to fabricate more permeable non-silicone lenses.

2. Results and Discussion

We analyze the chemical, optical, and mechanical properties of the CLs obtained from the seven manufactured polymer rods (i.e., sample 1E, sample 3E-A, sample 3E-B, sample 3E-C, sample 3E-D, sample 9E, and sample 23E).

2.1. Water Content

We show the water contents (WC) of the fabricated samples in

Table 1.

All samples presented a WC higher than 50% (WC values ranged between 75.69% and 80.60%) (

Table 1). Thus, they may be considered high-WC CLs based on the ISO standard 18369-1:2017 [

38]. The 3-EGDMA concentration affected the CL WC, reducing its content by almost 5% with increasing concentration (

Table 1, samples 3E-A, 3E-B, 3E-C y 3E-D). Regarding crosslinker length and for a similar EGDMA concentration (mol %), the WC raised from 1 to 3 crosslinker repetitions and decreased with more repetitions (

Table 1).

The WC is a pivotal characteristic of soft CLs [

39,

40]. Various studies have proven its effect on CL comfort by modifying their properties like the mechanical and surface ones and the oxygen permeability [

39,

41]. The high values of WC obtained in our work are due to the high amount of the hydrophilic monomer DMAA employed for CL synthesis [

22,

42,

43]. The slight decrease in CL-WC observed in our study related to the increased concentration of crosslinkers is consistent with the findings of other authors [

24]. For instance, in the study of Mohammed et al. [

24], an increase in the percentage of the 1-EGDMA crosslinker from 0 to 2 wt% resulted in a decrease in WC by 7%. This effect may occur because increasing the concentration of the crosslinking agent increases the structural restriction of the polymer chains and, thus, the inside free volume decreases, which, in turn, hinders the entry of water through the network and its swelling.

2.2. Oxygen Permeability

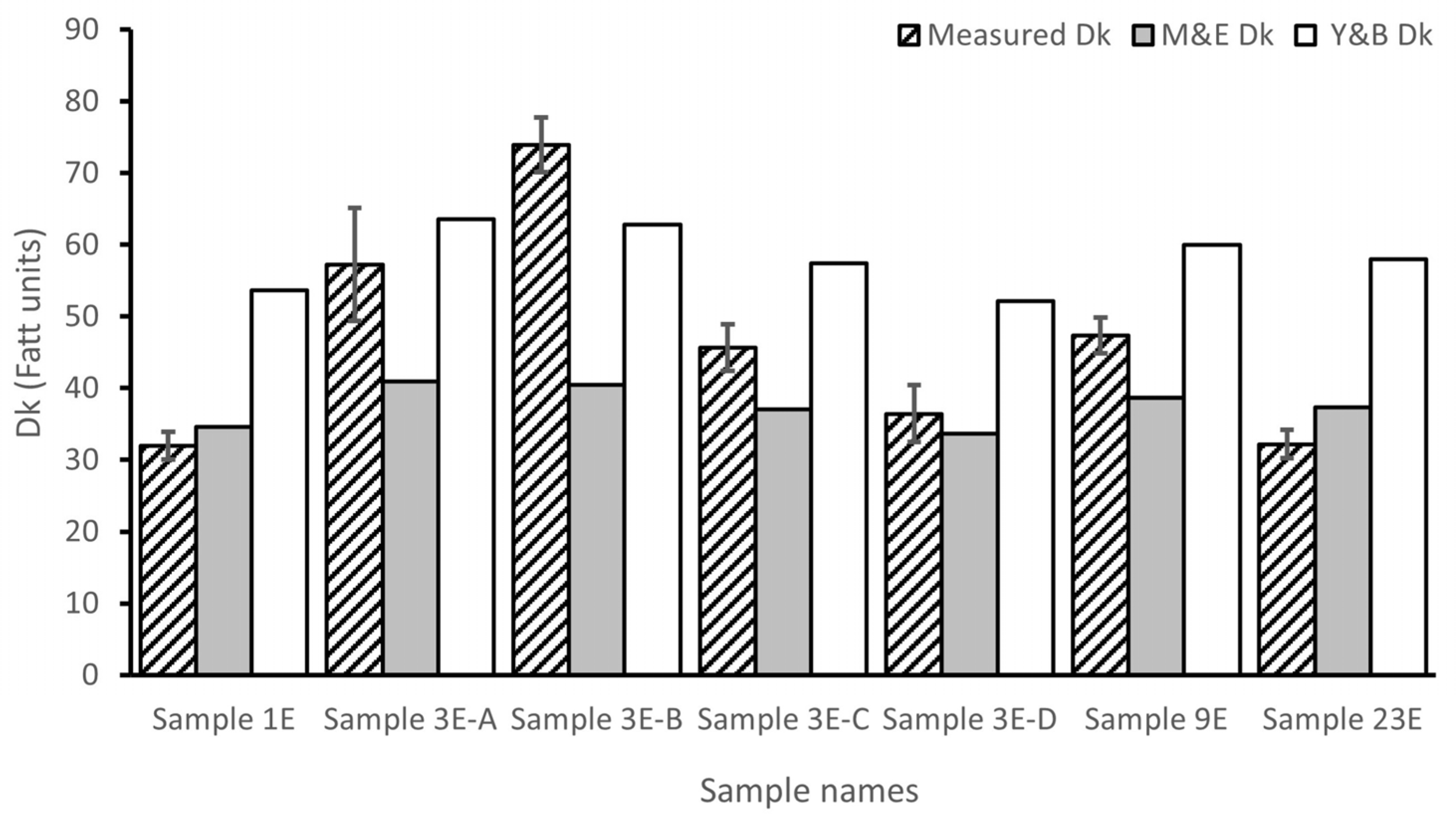

We measured the oxygen permeability (Dk) of the samples synthesized and compared their values with the ones obtained from Morgan and Efron (M&E) [

25] and Young and Benjamin (Y&B) [

26] equations that assume that Dk is exclusively dependent on WC.

The measured Dk of the samples varies from 31.95 to 73.90 Fatt units (

Figure 1).

The Dk parameter evaluates the oxygen diffusion through a material. It is critical in the case of CL that the material allows the oxygen molecule to reach the eye tissue, thus avoiding hypoxia [

44]. Consequently, multiple works have attempted to expand the knowledge of oxygen permeation mechanisms through CL and improve the material’s Dk [

1].

The oxygen diffusion path through the CLs depends on the hydrogel material. While in SiHy CLs, the oxygen flows through the hydrophobic phase, in Hy ones, the diffusion goes through the hydrophilic phase [

23,

26,

45]. This difference in the mechanism of oxygen passage explains the Dk diverseness between the various types of hydrogel CLs. Hence, while commercial SiHy CLs present Dk values ranging from 60 to above 100 Fatt units, Hy CLs show lower oxygen permeability with Dk values below 60 Fatt units [

6,

46]. In our study, six of the seven non-silicone hydrogel CLs fabricated presented Dk values like those of commercial Hy CLs (

Figure 1). Nevertheless, sample 3E-B presented a high Dk value (73.90 Fatt units) like that of commercial SiHy CLs (

Figure 1). This fact and all the Dks obtained for the total fabricated samples show that the crosslinker concentration (see Dk of samples 3E A-D), as well as its length (see Dk of samples 1E, 3E-B, 9E, and 23E), have an impact on oxygen permeability (

Figure 1).

Other authors have studied the impact of 1-EGDMA concentration on SiHy CL oxygen permeability. For instance, Mohammed et al. [

24] showed that the Dk values of SiHy CLs could decrease from 58.9 to 53.5 Fatt units when the 1-EGDMA content increased from 0 to 2 wt%. Similarly, Wu et al. [

23] observed that increasing concentrations of 1-EGDMA (from 0.5 to 1 wt%) decreased the Dk value of the hydrogels.

In our study, we also observed a decrease of the Dk with the rise of the concentration of 3-EGDMA crosslinker, from 0.27 to 0.99 wt% (

Figure 1, samples 3E-B, 3E-C y 3E-D). Similarly to the previous studies, as the crosslinker concentration increases, the space between the monomer chains reduces, limiting oxygen passage. However, the Dk rose when the 3-EGDMA concentration went from 0.15 to 0.27 wt% (

Figure 1, samples 3E-A y 3E-B). Thus, in our study with a lengthier EGDMA version, the oxygen permeability does not vary linearly with the crosslinkers´ concentration.

As shown in

Figure 1, some of our CLs presented Dk values below (Sample 1E and Sample 23E) or above (Sample 3E-B) those estimated by the equations of Morgan and Efron [

25] and Young and Benjamin [

26] and despite having a similar WC (

Table 2). These results, particularly that of Sample 3E-B [Dk experimental= 73.90 Fatt units versus Dk theoretical (Y&B/M&E) = 62.78/40.45 Fatt units], indicate that it is possible to improve the Dk of Hy CLs by modifying crosslinker conditions even with high WC values (80.28%) (

Figure 1 and

Table 1). More importantly, they show that water is not the only component that defines the Dk of Hy CLs and opens new possibilities for developing more permeable non-silicone hydrogel CLs.

2.3. Contact Angle

We also evaluated the in vitro wettability of the fabricated samples, measuring their contact angles (CA) (

Table 1). All the CLs presented a CA ranging from 81.00° to 100.00° (

Table 1).

The wettability of a material is the ability of a liquid to spread on the surface of the material. In the case of CLs, increased wettability means a better spread of the tear film over the lens, which is essential for maintaining a stable and uniform tear film on the lens, keeping ocular health, and enhancing comfort with reduced friction [

47,

48]. Although good wettability implies low CA values (i.e., below 90°), there are commercial CLs with CAs above 90 degrees, such as Acuvue Oasys

® (Senofilcon A) [

49] and PureVision

® (Balafilcon A) [

50] SiHy CLs.

Three of our seven samples presented a CA below 90° but above 80°, a surprising result due to their high WC (

Table 1). Other authors have reported the poor wettability ability of the hydrophilic monomer DMAA in comparison with the monomers N-vinyl pyrrolidone (NVP) and acrylic acid (AA) [

43,

51]. For instance, Hu et al. [

51] reported that a CL based on DMAA presented a CA of 90° and that its change with AA monomer triggered a higher wettability, reducing the CA by 16 degrees. Similarly, Tran et al. [

42] observed that a hydrogel CL mixture of 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA), NVP, and DMAA tended to increase in wettability when the content of NVP increased at the expense of DMAA.

Regarding the four remaining samples with CA above 90°, and as we have previously commented, some commercial CLs presented similar wettability like Acuvue Oasys

® (CA= 96.4°) [

49] and PureVision

® (CA= 93.6°) [

50]. Thus, all our hydrogels synthesized seem to be adequate for CL application.

The crosslinker length did not affect the CA parameter, but its concentration did, as its value decreased with increasing concentration (see CA of samples 3E A-D in

Table 2). Given that the sessile drop test is known to have a variation ranging from about 5° [

52] or more [

50,

53], this result could be negligible. In this sense, Seo et al. have considered insignificant differences in CA of 5 degrees [

54]. On the other hand, Ju et al. observed that the increase of poly (ethylene glycol, EG) diacrylate (PEGDA) crosslinker triggered an augmentation of CA due to the reduction of WC [

55]. Thus, more studies are necessary to confirm our results about the impact of EGDMA concentration and length on CA. Indeed, some authors have also reported a reduction of the CA with an augmentation of the crosslinker length [

55,

56]. Hence, Askari et al. [

56] found that modifying the crosslinkers from 3-EGDMA (0.27 wt%) to a mixture of 3-EGDMA with PEGDA (of either 200 or 600 g/mol) reduced the CA. Similarly, Ju et al. [

55] studied the effect of 10, 13, 23, and 45 EG repetitions of PEGDA on CA and found that the longer the EG chain, the higher the wettability.

2.4. Visible Light Transmittance and Transparency

Table 1 shows the values of the light transmittance of the different CLs. All the materials gave high transmittance, ranging from 85.91 to 99.91%.

The transmittance is a mandatory characteristic of the lens to guarantee the vision quality of the wearer and is related to the inner structure of the material [

57,

58]. Thus, to satisfy visual requirements, hydrogel materials must be able to transmit over 90% of visible light [

59], although some commercial CLs present lower transmittance values [

60].

In our study, all fabricated CLs except sample 3E-D showed a transmittance higher than 90% (

Table 1). Sample 3E-D presented a transmittance value slightly below 90% (

Table 1), but like the value of the commercial Air Optix

® (Lotrafilcon A) and PureVision

® (Balafilcon A) CLs [

60], with average transmittance values of 83% and 85% respectively (between 400 and 700 nm). Consequently, all our lenses presented adequate transparency for CL applications.

The effect of varying crosslinker concentration on the transmittance did not show a particular pattern. A maximum (99.91%) and minimum (85.91%) transmittance was observed at 0.50 and 0.99 wt% of 3EGDMA, respectively (

Table 1, samples 3E-C and 3E-D). Conversely, the number of EG repetitions did affect the transmittance, reaching its maximum value (96%) with only one EG repetition (

Table 1, samples 1E, 3E-B, 9E, and 23E).

This absence of pattern in transmittance due to crosslinker concentration has also been observed in the work of Seo et al. [

54], which employed another crosslinker agent, divinylbenzene. On the contrary, Wu et al. [

23,

24] showed a decrease in the transmittance with the increase of the 1-EGDMA concentration from 0.5 to 1.0 wt%. This different behavior concerning our results may be due to the shorter version of EGDMA that the authors employed to analyze the crosslinker concentration impact.

2.5. Refractive Index

We show the refractive indexes (n) of the samples in

Table 2. The CLR 12-70 refractometer could not measure the sample 1E n. Previous studies have also shown the incapacity of this refractometer to determine the n of some CLs [

61,

62]. The other samples presented n between 1.3630 (sample 3 E-A) and 1.3740 (sample 3 E-D) (

Table 1).

The n is a crucial parameter in the optical design of CLs that determines the CLs´ thickness and curvature. Although the n should be close to the one of the cornea [

63], generally estimated to be close to 1.38 [

64], a higher refractive index could be convenient for some designs, such as in high myopia CLs, because it allows the manufacture of thinner CLs [

65]. Moreover, thin lenses provide many advantages, such as higher comfort, rapid adaptation, and higher oxygen permeability [

66], thus making them more adapted for prolonged CL wear. However, they can be more challenging to handle, more prone to dehydration, and more fragile [

66]. Therefore, the n of commercial Hy and SiHy CLs tend to range from 1.37 to 1.44 for Hy, reaching the lowest values with high WC, and from 1.40 to 1.42 for SiHy [

61,

62,

67,

68]. Thus, the n measured in this study falls in the lower range or is slightly lower than the commercialized CLs. For instance, the samples with the highest refractive indexes sample 3E-D, with a n=1.3740, and Sample 23E, with a n=1.3700 (

Table 1) have similar n values to that of the Proclear 1-Day

® (Omafilcon A) (n=1.38-1.39 with 62% of WC) [

62,

67] and Acuvue 2

® (Etafilcon A) (n=1.40 with 58% of WC)[

62,

67], and the Biotrue ONEday

® (Nesofilcon) (n=1.37), respectively [

62].

Moreover, as previous authors have demonstrated [

33,

61,

67,

68,

69], the n of CLs is inversely related to WC (

Table 1). Thus, both the EGDMA concentration and its length modulate the n, increasing its value when raising these (

Table 1).

The impact of the concentration of crosslinkers on the n of a hydrogel was studied by Zhou et al. [

70]. They synthesized a hydrogel with different concentrations (from 5 to 11 mol%) of the crosslinker triethylene glycol diacrylate (3-EGDA) and observed its maximum n (n= 1.53) at 9 mol% 3-EGDA. These authors suggested that high crosslinker concentration could generate inhomogeneity (high point density) of the CL inner structure and, thus, increase its n [

71]. Further studies are needed to confirm the correlation between n and crosslinker concentration by analyzing the effect of different crosslinking agents and their length.

2.6. Tensile Test

To evaluate the possible effect of crosslinker concentration/length on the mechanical properties of the fabricated samples, we measured Young´s modulus and elongation at break parameters of the different CLs.

All the samples had low Young´s modulus (ranging from 0.066 to 0.167 MPa and high elongation at break (ranging from 178.95 to 356.05%) (

Table 2).

These parameters indicate the elasticity and break resistance of the CLs, which are essential to avoid problems on the ocular surface and to make the lens comfortable and handy [

77,

78,

79,

80]. Moreover, they allow the movement of the CL inside the eye, permitting tear exchange below the lens [

81]. Hence, commercial Hy and SiHy CLs have elastic moduli ranging between 0.3 and 1.9 MPa [

78] and elongation at break ranging from 100% to 250%, according to the measurements of Lonnen et al. [

82].

Although our CLs could be well-handled in the laboratory and considering the elasticity of commercial lenses, they had low elastic modulus (

Table 2). On the other hand, the elongation at break was higher than some commercial lenses, as they could reach 150-200% for the Acuvue2

® and 100%-200% for the Air Optix Night and Day

® (Lotrafilcon A) [

72,

73]. The high values of that parameter could be due to the larger thicknesses of our samples used for the tensile tests compared to the previous studies.

Our results also show that both parameters were affected by changes in the crosslinker concentration and its length (

Table 2). Regarding the concentration, and for the samples with three repetitions of EG (Samples 3E), its increase led to a rise in Young´s modulus and a decrease in the elongation at break (

Table 2). The elongation at break was also reduced by increasing the repetitions of EG in the crosslinker chain up to nine repetitions, while the twenty-three EG repetitions showed an increased elongation (

Table 2). Less clear is the effect of crosslinker length on elastic modulus, observing a lower Young´s moduli for the sample with three EG repetitions and a higher one for one, nine, and twenty-three-EG repetitions (

Table 2).

The crosslinkers are widely used components in hydrogels to enhance rigidity and brittleness [

23,

24,

37,

74,

75]. Consequently, various authors have analyzed the effect of crosslinker concentration and length on CL mechanical properties. For instance, the study of Mohamed et al. [

24] confirms our results about the concentration crosslinker effect on elastic modulus. These authors observed an increase in elastic modulus of 0.4 MPa when doubling 1-EGDMA concentration (from 0.5 at 1wt%) in an NVP SiHy CL. Similar trends have also been observed in the work of Wu et al. [

23], in which the elastic’s modulus increased (2.0 to 2.8 MPa), and the elongation at break decreased (178 to 85%) when the concentration of crosslinkers went from 0.5 to 1 wt%.

Zaragoza et al. [

75] also studied the effect of PEGDA length, finding that the longer the crosslinker (higher number of EG repetitions), the better the inside structure organization and, thus, the higher elastic modulus. On the contrary, Mabilleau et al. [

76] found that the replacement of 3-EGDA by the longer PEGDA crosslinkers decreased the elastic moduli. These authors suggested that the chain length of the crosslinkers provided more flexibility to the material. We observed that the crosslinker length impacted CL elastic moduli, but evolution was not steady. The lowest elastic moduli were for sample 3E-B (3-EGDMA), but it then increased for sample 9E (9-EGDMA), and sample 23 (23-EGDMA, which reached the highest value (

Table 2). Likewise, Xie et al. [

77] studied the mechanical properties of polyisoprene with three dicarboxylic acid crosslinkers differing in length, finding that the middle-length crosslinker provides the lowest elastic moduli. They explained that the shorter crosslinker length would constrain the chains and restrict the chain motion, resulting in remarkable binding effects. Conversely, the longer crosslinker chains would form entanglement, thus increasing the elastic moduli in both cases.

Our results and those of other authors suggest that the concentration and length of the crosslinking agent affect the mechanical properties of contact lenses. Specifically, our results indicate that EGMDA generates softer materials and that their CL application requires the development of strategies to increase their stiffness. We tried to augment the rigidity of our samples by adding to the sample 3E-B a slight amount (5 wt%) of other hydrophobic monomers, such as Dicyclopentanyl methacrylate (DCPMA) and Vinylbenzyl chloride (VBC), that are known to increase the rigidity of the material [

78,

79]. These modifications did not augment much the stiffness (Young´s moduli

DCPMA=0.08; Young´s moduli

VBC=0.12) of the samples and, even worse, reduced the oxygen permeability (DK

DCPMA= 53 Fatt units; DK

VBC= 52 Fatt units)(sample 3E-B properties are shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 1). Therefore, another strategy to enhance the rigidity of the hydrogel is needed, and the introduction of nanoparticles could be one of them [

20].

3. Conclusions

The concentration and length of the crosslinking agent ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) barely affected the water content, the wettability, the refractive index, the transmittance, and the young moduli parameters of non-silicone hydrogel contact lenses based on a mixture of N, N-Dimethylacrylamide and Cyclohexyl methacrylate. On the contrary, they did to the elongation-at-break and oxygen permeability parameters. More importantly, EGDMA variations provided Dk values of up to 73.90 Fatt units, approaching the permeability of silicone hydrogel contact lenses. This crosslinker’s ability to modulate the Dk value opens new possibilities for developing more permeable non-silicone hydrogel contact lenses.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

N,N-Dimethylacrylamide (DMAA) and Cyclohexyl methacrylate (CHMA) were purchased from Cornelius Specialities LTD (Haverhill, UK). Different crosslinkers were used, including ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, noted 1-EGDMA (average molecular weight Mw=198 g/mol), and the polyethylene glycol dimethacrylate with three, nine and twenty-three repetitions of ethylene glycol (EG) [noted as 3-EGDMA (Mw=286 g/mol); 9-EGDMA (Mw=536 g/mol); and 23-EGDMA (Mw= 1136 g/mol), respectively]. These crosslinkers were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK). 2,2′-Azobis(2,4-dimethylvaleronitrile), V65, was used as the polymerization initiator and was obtained from Wako Chemicals BmbH (Neuss, Germany). Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was prepared in our laboratory using Sodium phosphate dibasic from Honeywell (Bracknell, UK), Sodium chloride from VWR Chemicals (Leicestershire, UK), and Sodium phosphate monobasic from Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK), according to the section 4.9 of the ISO 18369-3 [

80]. We also prepared Borate buffered saline (BBS) (pH 7.2, 0.14M)

4.2. Preparation of the Hydrogel Lenses

To obtain contact lenses, we employed the lathe-cutting technique. Thus, from a mixture of the hydrophilic monomer DMAA and hydrophobic monomer CHMA, the different crosslinkers EGDMA (n-EGDMA), and the initiator V65, we generated a hydrogel, following the amounts indicated in

Table 3. The hydrogels were then lathe-cut in CL and finally hydrated in BBS.

The hydrogels were formed by the free-radical polymerization method [

81]. We stirred the hydrophilic and hydrophobic monomers (i.e., DMAA and CHMA, respectively) with the crosslinkers and the initiator at 20°C for 10 minutes. The resultant solution was filtered in a funnel through a paper of Whatman ashless grade 40 (8 µm pores) from Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK), degassed to remove the contained air inside the mixture), and poured into a polyethylene (PE) tube. Afterward, we added nitrogen at the top of the tube and capped it. The mixtures were then cured in a water bath at 25°C for 48 hours and post-cured at 100°C. Then, we extracted the resultant polymer rods from the PE tubes and cut them into buttons latched into lenses. Finally, we soaked lenses into the BBS overnight and autoclaved at 121°C.

4.3. Characterization Methods

4.3.1. Water Content

The water content (WC) of two contact lenses of each type was estimated by measuring the weight of the hydrated CL (W

hydrated) and of the same lens dried after putting it for 4 hours in the oven at 80°C (W

dry), using this formula [

82]

4.3.2. Oxygen Permeability

Given that the thickness of the lenses is a necessary parameter to calculate the oxygen permeability, we measured it with an electronic gauge (ET-3 Rehder, Rehder Development Company, Albany, CA, USA).

We calculated the oxygen permeability twice of each contact lens types using a curved polarographic cell (Rehder Development Company, Albany, CA, USA) coupled to an oxygen permeometer (model 201T, Createch, Albany, CA, USA), according to the polarographic method described in the ISO standard 18369-4 [

35]. The lenses were soaked previously to the measurements in PBS as suggested by ISO standard [

35]. The measurements were undertaken in a closed chamber heated with the temperature held at 35°C and maintained with a water vapor-saturated atmosphere reaching at least 98% relative humidity.

4.3.3. Contact Angle

We measured the contact angles of two contact lenses of each type with the sessile drop technique using a Drop Shape Analyzer (DSA25S, Krüss, Hamburg, Germany). Accordingly, after drying the surface of the CLs with a tissue, a drop of deionized water was deposited slowly on them. Then, we measured the angles during the first 2 seconds, 20 times, and took the means of the values as the contact angle.

4.3.4. Refractive Index

After soaking the synthesized CLs in BBS, refractive indexes of four contact lenses of each type were measured at 589 nm using a contact lens refractometer (CLR 12-70, Index Instruments Ltd., Huntingdon, UK).

4.3.5. Transmittance

To evaluate the optical transparency of the CLs, we determined the percent transmittance (T%) of visible light (wavelength range from 380 to 780 nm) of one hydrated lens of each type, using the UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Cary 60, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

4.3.6. Tensile Test

We performed the tensile tests using a universal testing machine (Instron 3343 tensometer, Instron, Norwood, USA). First, we cut the lenses in their middle area, obtaining lens strips with similar dimensions controlled by a projector (V-12B, Nikon Metrology NV, Tokyo, Japan). After that, we deposited the strips in deionized water for a few seconds, reducing thus their dehydration before attaching them to the grips of the tensile test. Finally, we evaluated the mechanical properties of two contact lenses of each type.

Author Contributions

Execution and writing—original draft preparation, C.L.; writing—review and edition, A.C.1b,3, and M.G-M; research supervision, A.C.2, P.H., M.G-M, and A.C.1b,3; conceptualization and funding acquisition, D.M-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 956274.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This article includes all data generated or analyzed during this study. For more information, please contact the corresponding author A.C.1b,3.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Neil Goodenough, mark’ennovy’s Group R&D Director, for his support and helpful comments during the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

P.H. is a member of the Mark’ennovy R&D Group, and A.C.2 was also member of that group but is now an independent researcher. Both were C.L. supervisors at the UK Mark’ennovy facility. C. L. is an early-stage researcher (ESR) of the European EYE project who performed a research stay of 18 months at the UK Mark’ennovy’s facility. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Nicolson, P.C.; Vogt, J. Soft Contact Lens Polymers: An Evolution. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 3273–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, P.B.; Efron, N. Global Contact Lens Prescribing 2000-2020. Clin Exp Optom 2022, 105, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreddu, R.; Vigolo, D.; Yetisen, A.K. Contact Lens Technology: From Fundamentals to Applications. Adv Healthc Mater 2019, 8, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.J.; Fisher, D. Contact Lenses 2022. Contact lens Spectrum, January, 2023; 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Musgrave, C.S.A.; Fang, F. Contact Lens Materials: A Materials Science Perspective. Materials 2019, 12, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, C.; McParland, M. The ACLM Contact Lens Year Book 2015; ACLM.; Association of Contact Lens Manufacturers: Wiltshire UK2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Papas, E.B. The Role of Hypoxia in the Limbal Vascular Response to Soft Contact Lens Wear. Eye Contact Lens 2003, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, J.A.; Polse, K.A. Corneal Acidosis during Contact Lens Wear: Effects of Hypoxia and CO2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1987, 28, 1514–1520. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.C.; Polse, K.A. Hypoxia, Overnight Wear, and Tear Stagnation Effects on the Corneal Epithelium: Data and Proposed Model. Eye Contact Lens 2007, 33, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillehay, S.M. Does the Level of Available Oxygen Impact Comfort in Contact Lens Wear?: A Review of the Literature. Eye Contact Lens 2007, 33, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, N.; Brennan, N.A.; Chalmers, R.L.; Jones, L.; Lau, C.; Morgan, P.B.; Nichols, J.J.; Szczotka-Flynn, L.B.; Willcox, M.D. Thirty Years of ‘Quiet Eye’ with Etafilcon A Contact Lenses. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2020, 43, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, B.A.; Mertz, G.W. Critical Oxygen Levels to Avoid Corneal Edema for Daily and Extended Wear Contact Lenses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1984, 25, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.P.; Barsam, A.; Chen, C.; Chukwuemeka, O.; Ghorbani-Mojarrad, N.; Kretz, F.; Michaud, L.; Moore, J.; Pelosini, L.; Turnbull, A.M.J.; et al. BCLA CLEAR Presbyopia: Management with Corneal Techniques. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2024, 47, 102190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvord, L.; Court, J.; Davis, T.; Morgan, C.F.; Schindhelm, K.; Vogt, J.; Winterton, L. Oxygen Permeability of a New Type of High Dk Soft Contact Lens Material. Optometry and Vision Science 1998, 75, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, S.W.; Cho, P.; Chan, B.; Choy, C.; Ng, V. A Comparative Study of Biweekly Disposable Contact Lenses: Silicone Hydrogel versus Hydrogel. Clin Exp Optom 2007, 90, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Brennan, N.A.; González-Méijome, J.; Lally, J.; Maldonado-Codina, C.; Schmidt, T.A.; Subbaraman, L.; Young, G.; Nichols, J.J. The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: Report of the Contact Lens Materials, Design, and Care Subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbleton, K.; Woods, C.A.; Jones, L.W.; Fonn, D. The Impact of Contemporary Contact Lenses on Contact Lens Discontinuation. Eye Contact Lens 2013, 39, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczotka-Flynn, L.; Chalmers, R. Incidence and Epidemiologic Associations of Corneal Infiltrates with Silicone Hydrogel Contact Lenses. Eye Contact Lens 2013, 39, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Lin, B. The Influence of Molecular Weight of Siloxane Macromere on Phase Separation Morphology, Oxygen Permeability, and Mechanical Properties in Multicomponent Silicone Hydrogels. Colloid Polym Sci 2017, 295, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.P.D.; Ting, C.C.; Lin, C.H.; Yang, M.C. A Novel Approach to Increase the Oxygen Permeability of Soft Contact Lenses by Incorporating Silica Sol. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.P.D.; Yang, M.C. The Ophthalmic Performance of Hydrogel Contact Lenses Loaded with Silicone Nanoparticles. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Tao, H.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Lin, B. The Influences of Poly (Ethylene Glycol) Chain Length on Hydrophilicity, Oxygen Permeability, and Mechanical Properties of Multicomponent Silicone Hydrogels. Colloid Polym Sci 2019, 297, 1233–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Lin, B.; Han, X.; Chen, P. Study on the Influence of Crosslinking Density and Free Polysiloxan Chain Length on Oxygen Permeability and Hydrophilicity of Multicomponent Silicone Hydrogels. Colloid Polym Sci 2021, 299, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.H.; Ahmad, M.B.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Zainuddin, N. Effect of Crosslinking Concentration on Properties of 3-(Trimethoxysilyl) Propyl Methacrylate/N-Vinyl Pyrrolidone Gels. Chem Cent J 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, P.B.; Efron, N. The Oxygen Performance of Contemporary Hydrogel Contact Lenses. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 1998, 21, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.D.; Benjamin, W.J. Calibrated Oxygen Permeability of 35 Conventional Hydrogel Materials and Correlation with Water Content. Eye Contact Lens 2003, 29, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, A. Local Oxygen Transmissibility of Disposable Contact Lenses. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2003, 26, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soluri, A.; Hui, A.; Jones, L. Delivery of Ketotifen Fumarate by Commercial Contact Lens Materials. Optometry and Vision Science 2012, 89, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulu, A.; Noma, S.A.A.; Gurses, C.; Koytepe, S.; Ates, B. Chitosan/Polyvinylpyrrolidone/MCM-41 Composite Hydrogel Films: Structural, Thermal, Surface, and Antibacterial Properties. Starch/Staerke 2018, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulu, A.; Balcioglu, S.; Birhanli, E.; Sarimeseli, A.; Keskin, R.; Koytepe, S.; Ates, B. Poly(2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate)/Boric Acid Composite Hydrogel as Soft Contact Lens Material: Thermal, Optical, Rheological, and Enhanced Antibacterial Properties. J Appl Polym Sci 2018, 135, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, N.; Morgan, P.B.; Nichols, J.J.; Walsh, K.; Willcox, M.D.; Wolffsohn, J.S.; Jones, L.W. All Soft Contact Lenses Are Not Created Equal. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2022, 45, 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; May, C.; Nazar, L.; Simpson, T. In Vitro Evaluation of the Dehydration Characteristics of Silicone Hydrogel and Conventional Hydrogel Contact Lens Materials. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2002, 25, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driest, P.J.; Allijn, I.E.; Dijkstra, D.J.; Stamatialis, D.; Grijpma, D.W. Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Based Poly(Urethane Isocyanurate) Hydrogels for Contact Lens Applications. Polym Int 2020, 69, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, N. Contact Lens Practice; Elsevier, 2018; ISBN 9780702066603.

- ISO 18369-4:2017 - Ophthalmic Optics — Contact Lenses — Part 4: Physicochemical Properties of Contact Lens Materials 2017.

- Chirila, T. V. Oxygen Permeability of Silk Fibroin Hydrogels and Their Use as Materials for Contact Lenses: A Purposeful Analysis. Gels 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitra, J.; Shukla, V.K. Cross-Linking in Hydrogels - A Review. American Journal of Polymer Science 2014, 4, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 18369-1:2017 Ophthalmic Optics — Contact Lenses — Part 1: Vocabulary, Classification System and Recommendations for Labelling Specifications. In; 2017.

- Tranoudis, I.; Efron, N. Water Properties of Soft Contact Lens Materials. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2004, 27, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tan, G.; Zhang, S.; Guang, Y. Influence of Water States in Hydrogels on the Transmissibility and Permeability of Oxygen in Contact Lens Materials. Appl Surf Sci 2008, 255, 604–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranoudis, I.; Efron, N. Tensile Properties of Soft Contact Lens Materials. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2004, 27, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.P.D.; Yang, M.C. Synthesis and Characterization of Silicone Contact Lenses Based on TRIS-DMA-NVP-HEMA Hydrogels. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.C.; Valint, P.L. Control of Properties in Silicone Hydrogels by Using a Pair of Hydrophilic Monomers. J Appl Polym Sci 1996, 61, 2051–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, N.A.; Efron, N.; Holden, B.A.; Fatt, I. A Review of the Theoretical Concepts, Measurement Systems and Application of Contact Lens Oxygen Permeability. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 1987, 7, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozuelo, J.; Compañ, V.; González-Méijome, J.M.; González, M.; Mollá, S. Oxygen and Ionic Transport in Hydrogel and Silicone-Hydrogel Contact Lens Materials: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. J Memb Sci 2014, 452, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Société française des ophtalmologistes adaptateurs de Lentilles de Contact (SFOALC) Les Avancées En Contactologie: Rapport SFOALC 2019, Rapport Annuel 2019 Des BSOF; Med-line. 2019.

- Kuc, C.J.; Lebow, K.A. Contact Lens Solutions and Contact Lens Discomfort: Examining the Correlations between Solution Components, Keratitis, and Contact Lens Discomfort. Eye Contact Lens 2018, 44, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.C.; Svitova, T.F. Contact Lenses Wettability in Vitro: Effect of Surface-Active Ingredients. Optometry and Vision Science 2010, 87, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, C.M.; WY Chan, V.; Drolle, E.; Hui, A.; Ngo, W.; Bose, S.; Shows, A.; Liang, S.; Sharma, V.; Subbaraman, L.; et al. Evaluating the in Vitro Wettability and Coefficient of Friction of a Novel and Contemporary Reusable Silicone Hydrogel Contact Lens Materials Using an in Vitro Blink Model. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2024, 47, 102129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Codina, C.; Morgan, P.B. In Vitro Water Wettability of Silicone Hydrogel Contact Lenses Determined Using the Sessile Drop and Captive Bubble Techniques. J Biomed Mater Res A 2007, 83A, 1376–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Brittain, W.J. Surface Grafting on Polymer Surface Using Physisorbed Free Radical Initiators. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 6592–6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, M.L.; Morgan, P.B.; Maldonado-Codina, C. Measurement Errors Related to Contact Angle Analysis of Hydrogel and Silicone Hydrogel Contact Lenses. Contact Lens Spectrum 2007, 91, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, K.L.; Rogers, R.; Jones, L. In Vitro Contact Angle Analysis and Physical Properties of Blister Pack Solutions of Daily Disposable Contact Lenses. Eye Contact Lens 2010, 36, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.; Kumar, S.; Lee, J.; Jang, J.; Park, J.H.; Chang, M.C.; Kwon, I.; Lee, J.S.; Huh, Y. il Modified Hydrogels Based on Poly(2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate) (PHEMA) with Higher Surface Wettability and Mechanical Properties. Macromol Res 2017, 25, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; McCloskey, B.D.; Sagle, A.C.; Kusuma, V.A.; Freeman, B.D. Preparation and Characterization of Crosslinked Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Diacrylate Hydrogels as Fouling-Resistant Membrane Coating Materials. J Memb Sci 2009, 330, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, F.; Zandi, M.; Shokrolahi, P.; Tabatabaei, M.H.; Hajirasoliha, E. Reduction in Protein Absorption on Ophthalmic Lenses by PEGDA Bulk Modification of Silicone Acrylate-Based Formulation. Prog Biomater 2019, 8, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusong, P.; Jie, D.; Yan, C.; Qianqian, S. Study on Mechanical and Optical Properties of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Hydrogel Used as Soft Contact Lens. Materials Technology 2016, 31, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, R. The Transparency of Crystalline Polymers The Empirical Approach toward Increasing Transparency Of. Polym Eng Sci 1964, 4, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, N.; Maldonado-Codina, C. 7.35 Development of Contact Lenses from a Biomaterial Point of View: Materials, Manufacture, and Clinical Application. Comprehensive Biomaterials II. [CrossRef]

- Lira, M.; Dos Santos Castanheira, E.M.; Santos, L.; Azeredo, J.; Yebra-Pimentel, E.; Real Oliveira, M.E.C.D. Changes in UV-Visible Transmittance of Silicone-Hydrogel Contact Lenses Induced by Wear. Optometry and Vision Science 2009, 86, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.J.; Berntsen, D.A. The Assessment of Automated Measures of Hydrogel Contact Lens Refractive Index. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 2003, 23, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ehrmann, K. Refractive Index of Soft Contact Lens Materials Measured in Packaging Solution and Standard Phosphate Buffered Saline and the Effect on Back Vertex Power Calculation. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2020, 43, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, N. Soft Lens Materials. In Contact lens practice; 2018; p. 52.

- Patel, S.; Tutchenko, L. The Refractive Index of the Human Cornea: A Review. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2019, 42, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Cui, Y. Polymerizable-Group Capped ZnS Nanoparticle for High Refractive Index Inorganic-Organic Hydrogel Contact Lens. Materials Science and Engineering C 2018, 90, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, H.A.; Slatt, B.J.; Stein, R.M.; Freeman, M.I. Soft Lenses. In Fitting guide for rigid and soft contact lenses; 2002; p. 81.

- González-Méijome, J.M.; Lira, M.; López-Alemany, A.; Almeida, J.B.; Parafita, M.A.; Refojo, M.F. Refractive Index and Equilibrium Water Content of Conventional and Silicone Hydrogel Contact Lenses. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 2006, 26, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, M.; Santos, L.; Azeredo, J.; Yebra-Pimentel, E.; Real Oliveira, M.E.C.D. The Effect of Lens Wear on Refractive Index of Conventional Hydrogel and Silicone-Hydrogel Contact Lenses: A Comparative Study. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2008, 31, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ehrmann, K. Refractive Index of Soft Contact Lens Materials Measured in Packaging Solution and Standard Phosphate Buffered Saline and the Effect on Back Vertex Power Calculation. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2020, 43, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Heath, D.E.; Sharif, A.R.M.; Rayatpisheh, S.; Oh, B.H.L.; Rong, X.; Beuerman, R.; Chan-Park, M.B. High Water Content Hydrogel with Super High Refractive Index. Macromol Biosci 2013, 13, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, J.; Wang, Z.Y. Refractive Index Matching: A General Method for Enhancing the Optical Clarity of a Hydrogel Matrix. Chemistry of Materials 2002, 14, 4487–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, S.L.; Court, J.L.; Redman, R.P.; Wang, J.H.; Leppard, S.W.; O’Byrne, V.J.; Small, S.A.; Lewis, A.L.; Jones, S.A.; Stratford, P.W. A Novel Phosphorylcholine-Coated Contact Lens for Extended Wear Use. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 3261–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonnen, J.; Putt, K.S.; Kernick, E.R.; Lakkis, C.; May, L.; Pugh, R.B. The Efficacy of Acanthamoeba Cyst Kill and Effects upon Contact Lenses of a Novel Ultraviolet Lens Disinfection System. Am J Ophthalmol 2014, 158, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.S.H.; Ashton, M.; Dodou, K. Effect of Crosslinking Agent Concentration on the Properties of Unmedicated Hydrogels. Pharmaceutics 2015, 7, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza, J.; Chang, A.; Asuri, P. Effect of Crosslinker Length on the Elastic and Compression Modulus of Poly(Acrylamide) Nanocomposite Hydrogels. J Phys Conf Ser 2017, 790, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabilleau, G.; Stancu, I.C.; Honoré, T.; Legeay, G.; Cincu, C.; Baslé, M.F.; Chappard, D. Effects of the Length of Crosslink Chain on Poly(2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate) (PHEMA) Swelling and Biomechanical Properties. J Biomed Mater Res A 2006, 77, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.J.; Wang, C.C.; Zhang, R.; Cao, J.; Tang, M.Z.; Xu, Y.X. Length Effect of Crosslinkers on the Mechanical Properties and Dimensional Stability of Vitrimer Elastomers with Inhomogeneous Networks. Polymer (Guildf) 2024, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronci, G.; Grant, C.A.; Thomson, N.H.; Russell, S.J.; Wood, D.J. Influence of 4-Vinylbenzylation on the Rheological and Swelling Properties of Photo-Activated Collagen Hydrogels. MRS Adv 2016, 1, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, F.; Maizuru, N.; Hatano, K. Optical Resin Material and Optical Film EP No 2982700A1 2016.

- ISO 18369-3:2017 - Ophthalmic Optics — Contact Lenses — Part 3: Measurement Methods. In; 2017.

- Brazel, C.S. Fundamental Principles of Polymeric Materials; 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Nashville, TN, 2012.

- Tran, N.P.D.; Ting, C.C.; Lin, C.H.; Yang, M.C. A Novel Approach to Increase the Oxygen Permeability of Soft Contact Lenses by Incorporating Silica Sol. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).