2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical considerations

This was a prospective cohort study performed according to the principles of the declaration of helsinki. The objective of the study and the therapeutic efficacy and safety of lcm were explained to the patients and their parents, who provided informed consent prior to enrolment. This study was approved by the bioethics committee of st. Marianna university school of medicine (approval number: no. 6066). All experiments were performed according to the approved protocol.

2.2. Patient Selection and Treatment

This study included 101 randomly selected patients with focal epilepsy (45 females, 56 males; age range, 4.1 - 26.3 years) treated with LCM in the pediatric department of Kawasaki Municipal Tama Hospital and St. Marianna University School of Medicine from April 2020 to September 2022. All patients and their parents were informed about the procedure and the purpose of the study, and they all agreed to participate. The patients included 26 with focal aware seizure (FAS), 48 with focal impaired awareness seizure (FIAS), and 74 with focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizure (FBTCS). In this study, a patient could have multiple seizure types. Details categorized by seizure type and the timing of sampling are shown in

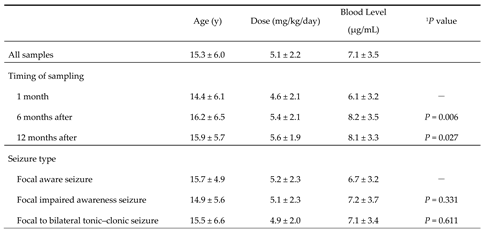

Table 1.

Eligible patients were diagnosed based on “the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) Commission for Classification and Terminology, 2017” [

8,

9] by their clinical seizure type, electroencephalogram, and either cranial computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Children with other systemic (cardiac, respiratory, hepatic, renal, or endocrinological) diseases were excluded.

Before starting LCM treatment, patients received the same kinds and dosages of ASMs for 4 more weeks, but the drugs were insufficiently effective. The dose of LCM was started at 1-2 mg/kg/day. If the patient showed seizures, the dose was increased by 2 mg/kg/day every 2 weeks. The maintenance dose was increased to 12 mg/kg/day for patients weighing less than 30 kg, and to 8 mg/kg/day for patients weighing 30-50 kg. We considered that the dose sufficient to eliminate seizures was the maintenance dose for each patient. For patients weighing more than 50 kg, the maximum dose was set to 400 mg/day. When LCM was added to therapy, all patients were on treatment with multiple ASMs (range, 1-3). Furthermore, the discontinuation criteria for this study were: no routine sampling of blood levels; no measurement of body weight at sampling time; poor adherence; and discontinuation of treatment due to serious side effects. Nine cases experienced side effects, but since their symptoms were only temporary drowsiness and resolved without intervention, they were able to continue in the study.

2.3. Sample Collection and Evaluation

Blood levels of LCM were measured regularly. Blood was sampled at the pediatric outpatient clinic and measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) in an external laboratory (LSI Medience Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). A minimum sample of 0.1 mL of serum was frozen at -30 °C and saved. Blood samples for LCM level measurements were obtained at any time and were measured 1, 6, and 12 months after reaching steady state.

The total number of blood sampling opportunities was 215. The timing of sample collection was arbitrary, so peak and trough levels were estimated individually using simulation software (PEDA VB ver.1.0.0.58).

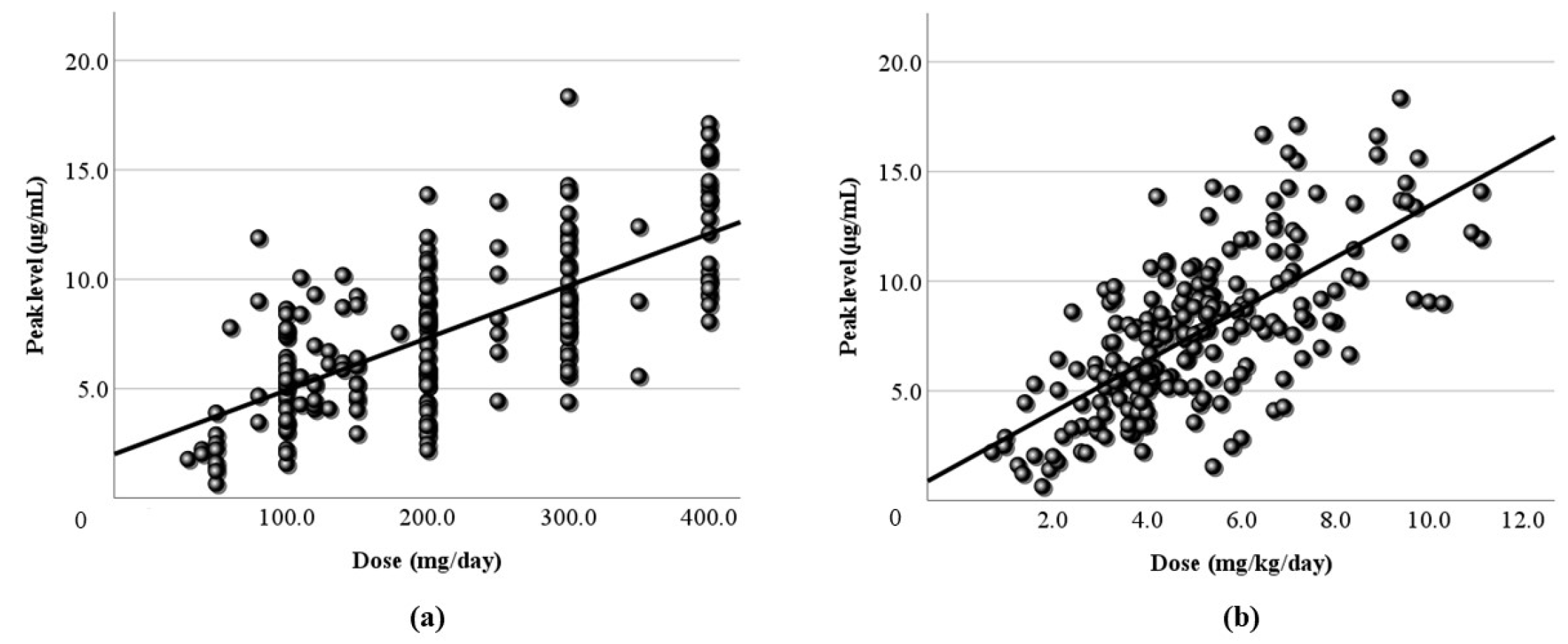

The efficacy of LCM was evaluated by the reduction in the epileptic seizure rate (RR) at the time of blood sampling. RR at each evaluation was calculated as follows.

Overall, a reduction in seizure frequency of greater than 50% was defined as “effective”.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The correlations between parameters (LCM dose, LCM blood level, and RR) were analyzed. Statistical analysis was performed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to verify the correlation and Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test for comparisons between two groups. IBM SPSS Statistics Ver. 28.0.0.0 (190) (IBM Japan, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used for all analyses.

4. Discussion

There have been many reports of the efficacy of LCM for pediatric patients [

10,

11,

12]. Kohn suggested that measuring serum concentrations of LCM in pediatric patients on treatment might not be necessary [

4]. Another reason for not measuring them may be the lack of pharmacokinetic interactions observed between LCM and other ASMs [

7,

13,

14]. TDM is important for effective and safe treatment using oral ASMs. In our view, TDM can be helpful because of the report about CYP2C19 polymorphisms that affect the serum concentration of LCM [

15].

LCM is a drug with a unique mechanism of action, slowly promoting sodium channel inactivation [

2,

3]. LCM has another mechanism involving modulation of CRMP-2 activity [

16,

17,

18]. Thus, it has been considered a promising candidate with a broad spectrum of action, including epilepsy, neuropathic pain, and other indications, and it has been adopted not only in Japan, but also in many other countries.

Though studies of LCM pharmacokinetics in pediatric patients with epilepsy have been reported [

4,

6,

19], the therapeutic range of the blood level has not been established. There are also reports that there is no relationship between the blood level of LCM and its effectiveness [

4]. Therefore, the correlations between oral dosage and blood level and between blood level and RR were investigated to try to set the therapeutic range of LCM. Unfortunately, setting the therapeutic range of LCM blood levels was difficult based on the results, because the blood level and efficacy showed no positive correlation, regardless of duration or seizure type (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). However, it seemed possible to set the optimal range for the therapeutic target, because there was a significant difference between effective and ineffective cases with LCM treatment.

First, there were significant differences in LCM blood levels after steady state was reached in the present study (

Table 1). The blood level immediately after reaching steady state was compared with those 6 months after and 12 months after. Whereas blood levels were significantly higher 6 and 12 months after, there were no differences in effectiveness. The reasons for significant increases in doses may be due to seizure recurrence or weight gain. Whether the dose was increased without seizures decreasing, or the blood level decreased due to the patient’s growth, the RR of effectiveness seemed difficult to increase [

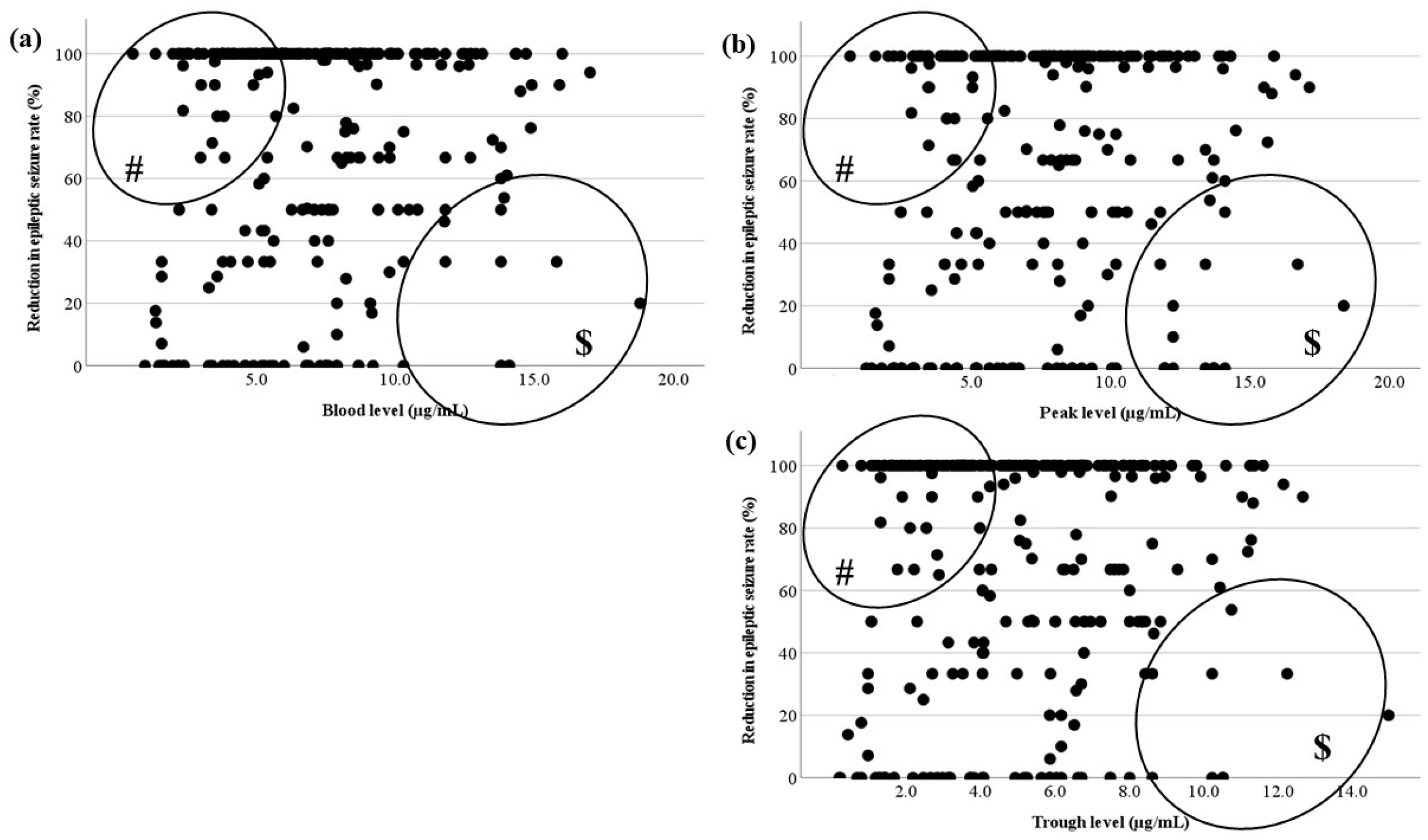

20]. In particular, since there were many cases in which low doses of LCM were effective (# in

Figure 5) [

21], it was predicted that increasing the dose would be less effective in refractory cases in which seizures occurred after steady state (

$ in

Figure 5). These appeared to be the reasons for the lack of correlations. No reports of the effect of LCM depending on the seizure type could be identified, but the effectiveness of LCM for generalized tonic-clonic seizures was reported [

22]. Therefore, we hypothesized that its effect and the required dose may differ by seizure type, and they were compared by classifying them into three types. However, there were no significant differences in their blood levels. Thus, the hypothesis was not confirmed (

Table 1). Furthermore, a correlation between blood level and RR for each seizure type was also sought, but this too could not be confirmed (

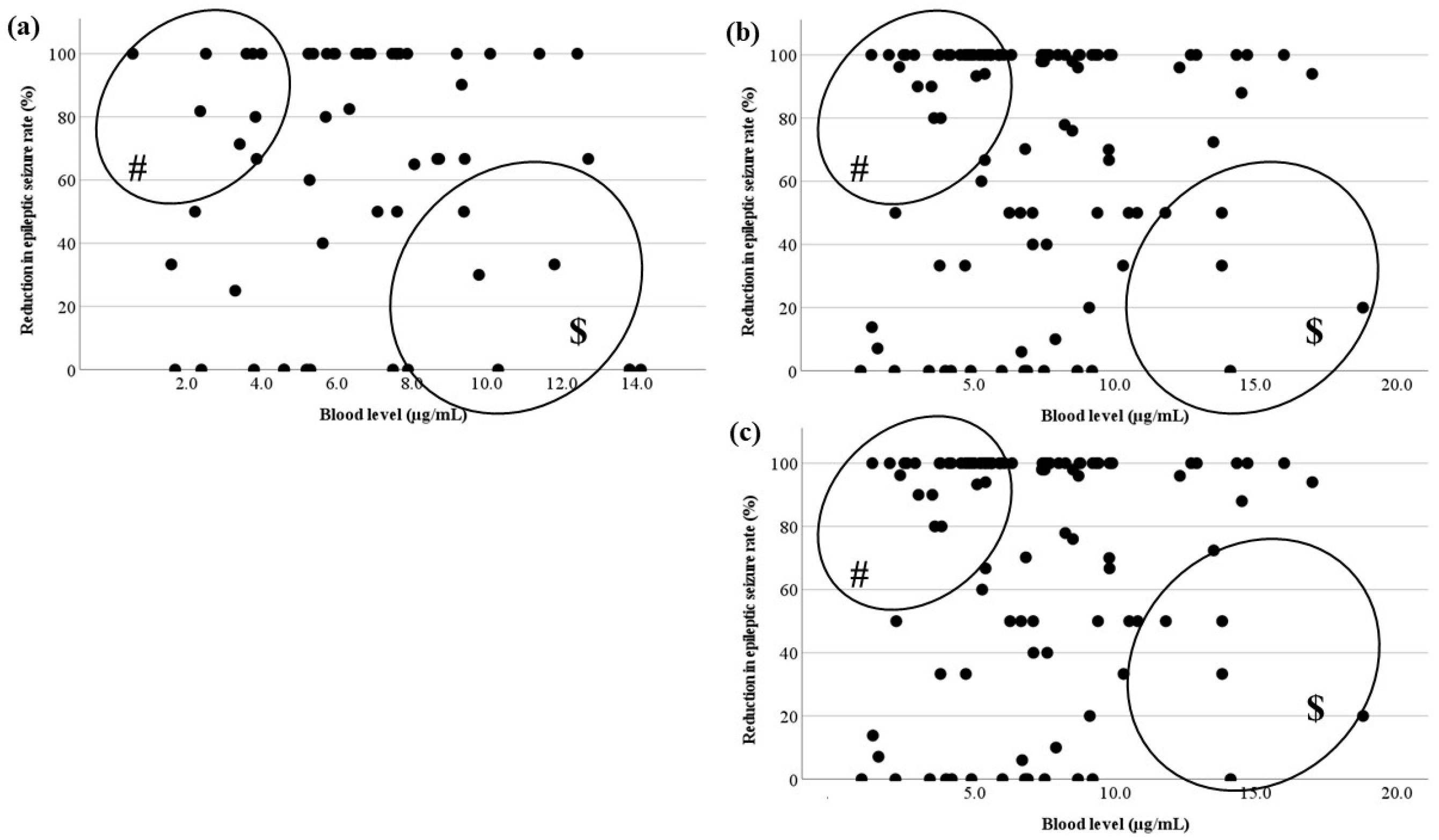

Figure 6). Because it was not possible to change the oral dose or set the therapeutic range depending on the seizure type, the optimal range of LCM treatment for focal seizure was investigated.

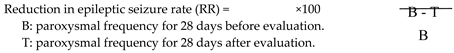

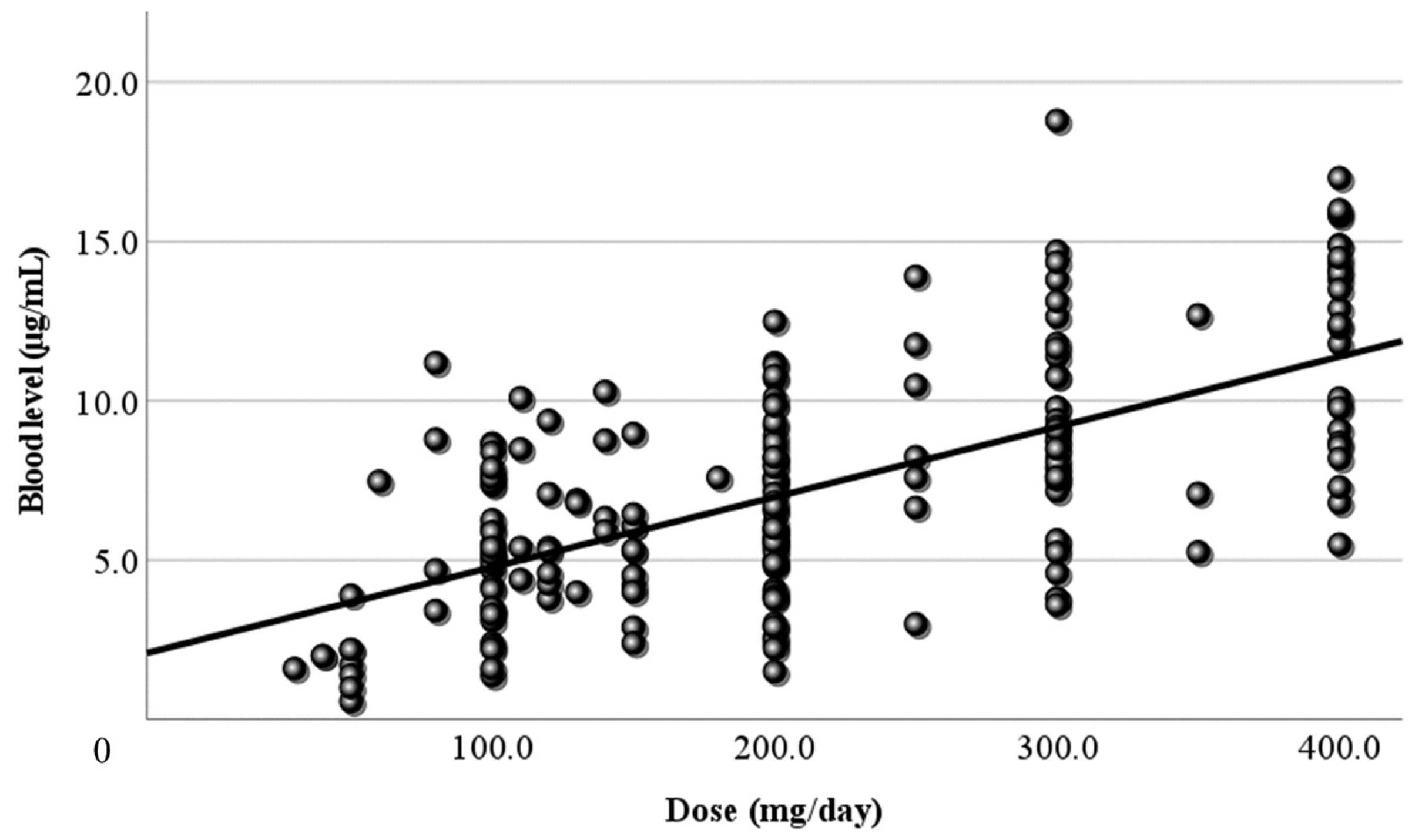

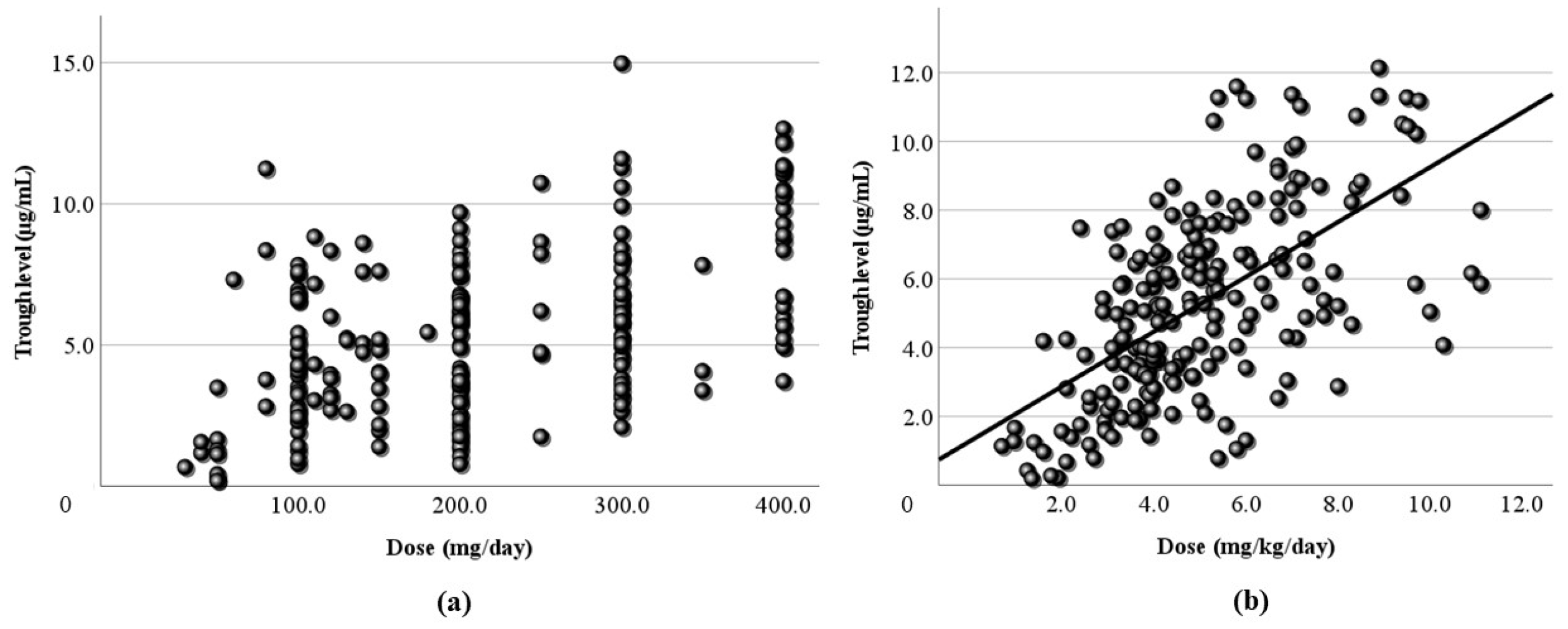

Next, LCM doses and blood levels had a positive correlation in the present study, as in previous reports [

4,

6,

7,

23]. Both the correlation coefficient of the daily dose (

Figure 1) and that of the dose corrected by body weight (

Figure 2) were relatively low (r = 0.406, 0.446, respectively). Based on TDM, it was considered reasonable that the corrected dose was slightly higher than the daily dose. In order to set the optimal range, it was essential to demonstrate the correlation between dose and blood level. Furthermore, the peak (

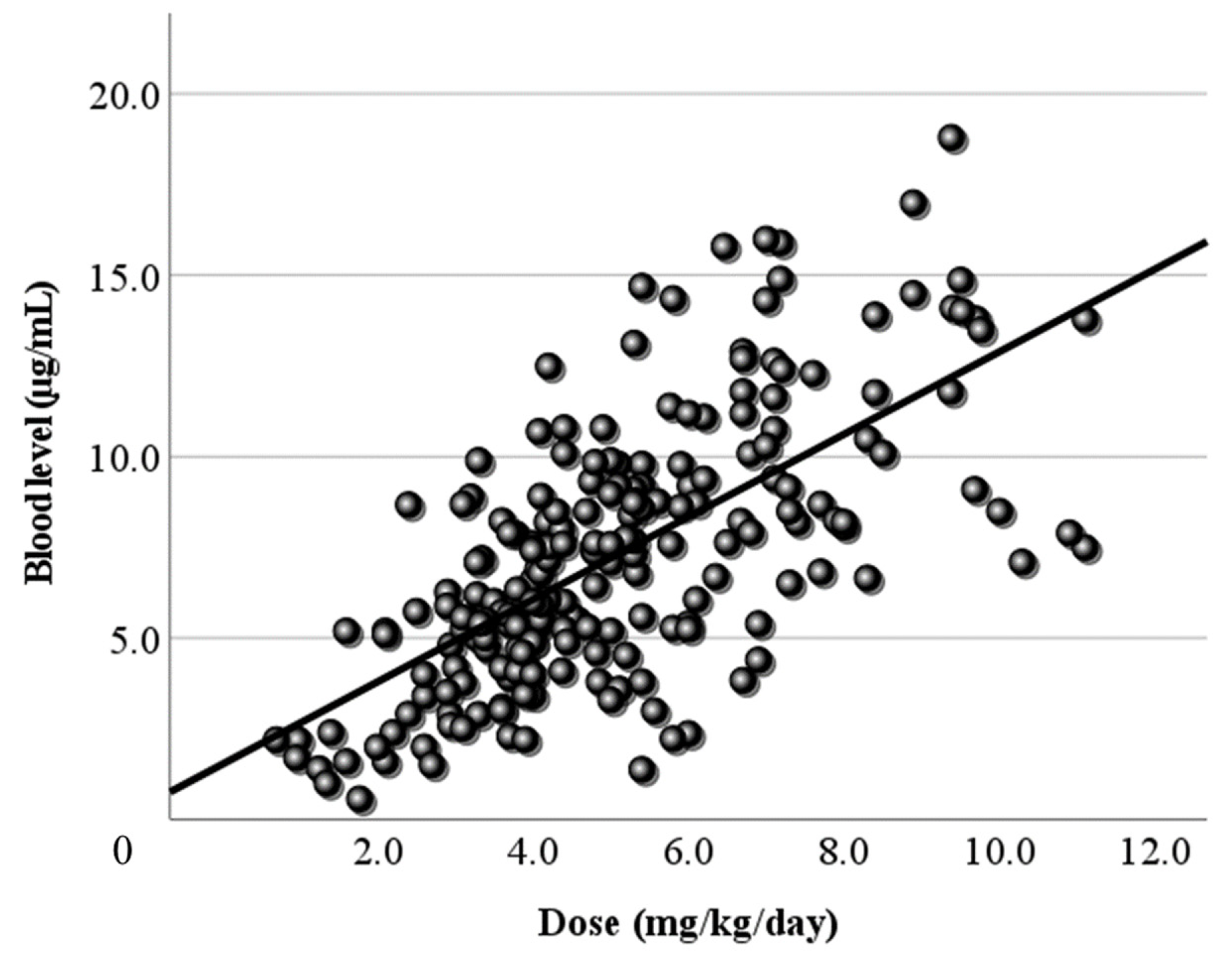

Figure 3) and trough levels (

Figure 4) were simulated using computer software, and the correlation with dose was examined. It was found that the correlation of the peak level was slightly high, and the correlation of the trough level was low. Generally, it is thought that the peak level is more reproducible and stable than actual values, and the trough level must be more so. We thought that the sampling timing of blood caused the trough level to be scattered. It was not believed that factors such as incorrect reporting of medication times and sudden forgetting to take medication have large effects on the trough level. Most of the collected samples were taken 2-4 hours after the morning dose. These are times close to the peak level, and it appeared that even the simulated peak levels were more accurate than the trough levels.

There was no correlation between the blood level and RR in each timing based on TDM (

Figure 5). In

Figure 6, there were no relationships in each seizure type. This could be because there were effective cases even when blood levels were low (# in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), and another reason was that the RR did not increase unexpectedly, because the LCM dose was increased due to insufficient efficacy (

$ in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The reason why cases with low blood levels had high efficacy was unknown, but it is a positive feature preventing dose-dependent side effects that a low dose of LCM is effective. Therefore, it is justified to start with a low initial dosage, since a low blood level is associated with sufficient efficacy. There is also a report that LCM treatment is effective, particularly at higher doses [

19]. In the present cases, if the efficacy was inadequate at the high dose, then sufficient efficacy might not be obtained if the dose was increased to the maximum (12 mg/kg/day).

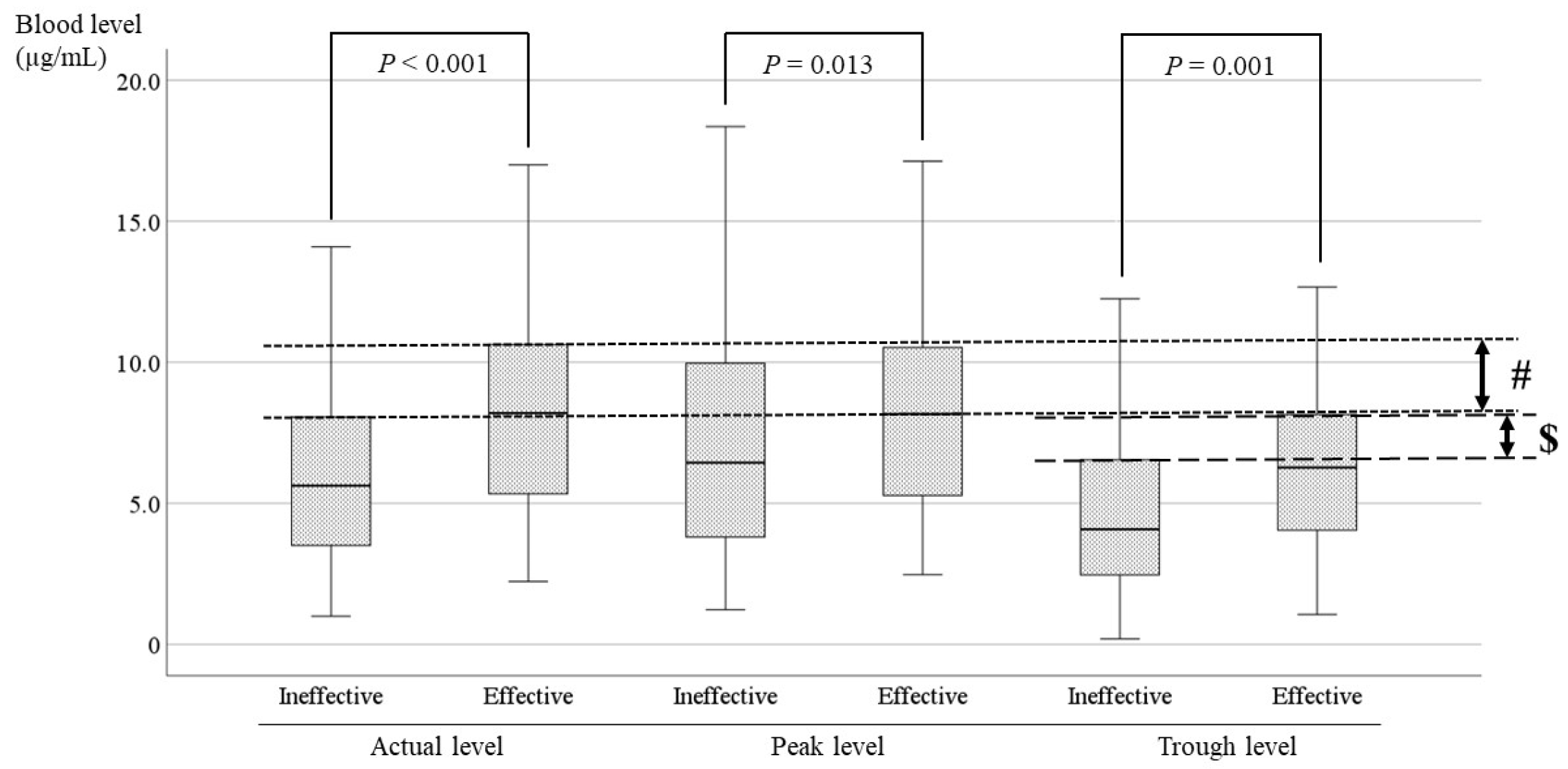

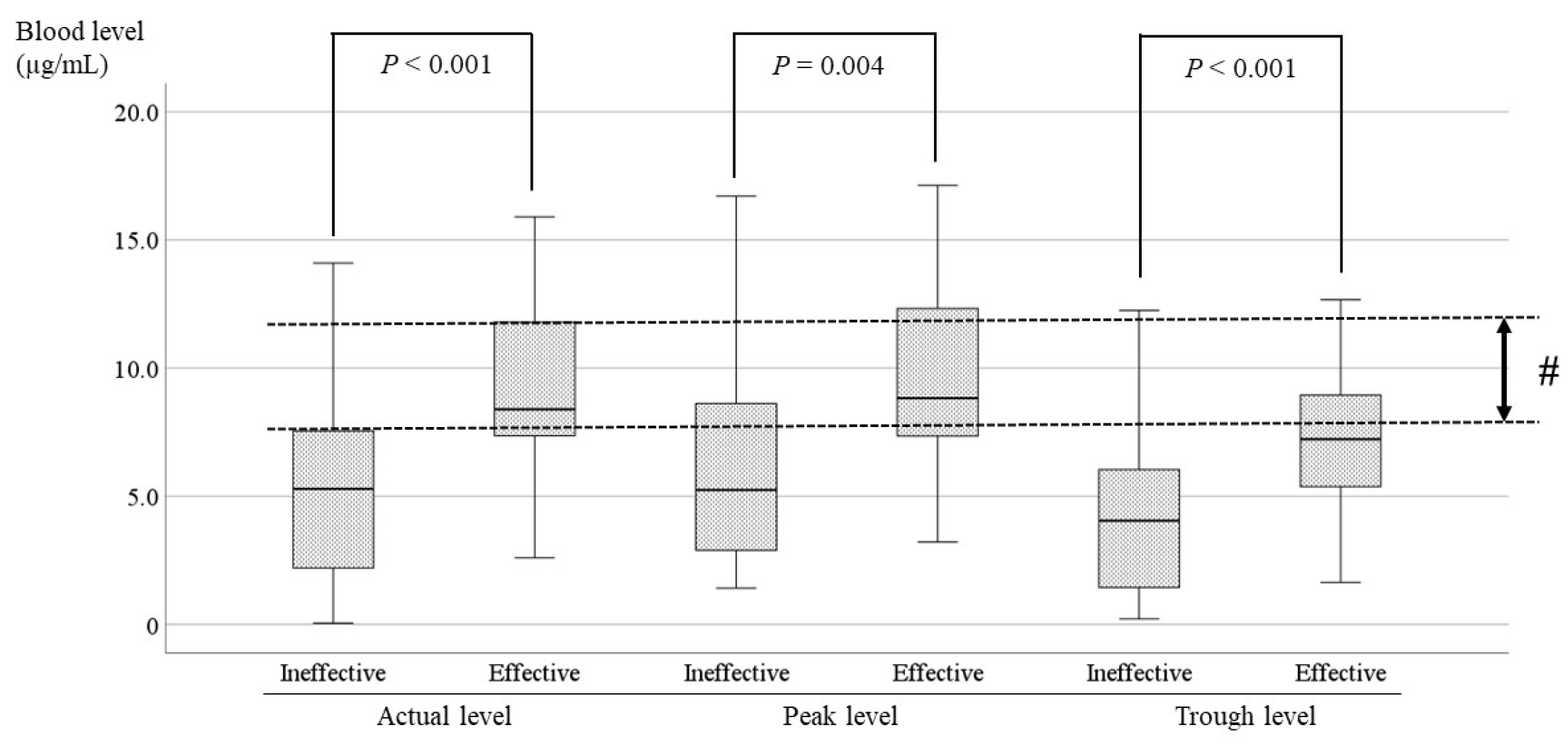

The current study showed significant differences between effective cases and ineffective cases in patients receiving LCM (

P < 0.001,

P = 0.013,

P = 0.001;

Figure 7). The optimal range was set to include the range in which the blood levels of the effective cases and the ineffective cases did not overlap based on the average, standard deviation, and upper limit of the 95% confidence interval. Therefore, it was suggested that the optimal range of the actual level is 8.0–10.5 µg/mL (# in

Figure 7), and the optimal range of the trough level is 6.5–8.0 µg/mL (

$ in

Figure 7). The minimum of the ranges was established to avoid overlap with the level in ineffective cases. Because the correlation between the trough level and the dose was insufficient (r=0.372) in the present study, the optimal recommended range is 8.0–10.5 µg/mL.

LCM has been shown to be effective in the treatment of partial seizures in patients from 4 years of age [

24,

25]. LCM seems to be particularly effective for tonic-clonic seizures [

22]. In the present study, a significant difference was found between effective and ineffective cases of FBTCS in epilepsies with tonic-clonic seizures (

Figure 8). The target range in FBTCS was slightly higher than the optimal range mentioned above. It was expected that the dosage would be adjusted proactively because the patients and their families want the seizures to be completely suppressed, because the seizures in FBTCS are easily identified by the families and have large impacts on daily life. Therefore, doctors would likely make frequent and sensitive adjustments to the LCM dose based on parental reports of detailed seizures. We thought that the optimal ranges in FBTCS would be higher than the optimal range of all cases, and there would be less overlap between the effective group and the other group. The target range of the results in the present study was lower than existing reports [

7,

19,

26,

27,

28]. There have been very few reports that advocated a range lower than the optimal range of the present study [

21]. As mentioned above, there were cases in which low LCM blood levels were effective (# in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), and we thought that the presence of these cases was one of the reasons. Furthermore, it was also considered that these cases were more numerous than the ineffective cases with higher LCM levels (

$ in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). This study was also conducted to determine the relationship between seizure type and LCM dose based on its blood levels [

29,

30], and a correlation between the LCM dose and blood level was demonstrated. However, no correlation was observed between the blood concentration and the seizure reduction rate in FAS, FIAS, and FBTCS, because there were many cases in which low doses of LCM were effective, or even high doses were insufficiently effective. Similar to the comparison of blood levels between the LCM effective group and the other groups in the whole population, the two groups were compared for each seizure type; no significant differences were observed, except for FBTCS. This might be due to inadequate medication in FAS and FIAS compared with FBTCS, due to a tendency to overlook seizures. Therefore, comparisons of the optimal ranges for each type of seizure were impossible, and the required oral dose for each type could not be stated.

Figure 1.

Relationship between the dose and the blood level of LCM. The daily dose (mg/day) and its blood level have a positive correlation at all sampling time points (r=0.406). The regression line is “y = 0.02x + 2.58”.

Figure 1.

Relationship between the dose and the blood level of LCM. The daily dose (mg/day) and its blood level have a positive correlation at all sampling time points (r=0.406). The regression line is “y = 0.02x + 2.58”.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Relationship between the corrected dose and the blood level of LCM. The dose corrected by body weight (mg/kg/day) and the blood level have a positive correlation. The correlation coefficient is 0.446, slightly higher than the coefficient for the daily dose. The regression line is “y = 1.14x + 1.52”.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Relationship between the corrected dose and the blood level of LCM. The dose corrected by body weight (mg/kg/day) and the blood level have a positive correlation. The correlation coefficient is 0.446, slightly higher than the coefficient for the daily dose. The regression line is “y = 1.14x + 1.52”.

Figure 3.

Relationship between the dose and the peak blood level of LCM. (a) The calculated peak blood level and the daily dose (mg/day) have a positive correlation (r = 0.479). (b) The peak blood level and the corrected dose (mg/kg/day) also have a positive correlation (r=0.478). The regression lines are “y = 0.02x + 2.54” and “y = 1.18x + 1.67”, respectively.

Figure 3.

Relationship between the dose and the peak blood level of LCM. (a) The calculated peak blood level and the daily dose (mg/day) have a positive correlation (r = 0.479). (b) The peak blood level and the corrected dose (mg/kg/day) also have a positive correlation (r=0.478). The regression lines are “y = 0.02x + 2.54” and “y = 1.18x + 1.67”, respectively.

Figure 4.

Relationship between the dose and the trough blood level of LCM. (a) The calculated trough blood level and the daily dose (mg/day) have no correlation. (b) The trough blood level and the corrected dose (mg/kg/day) have a subtle positive correlation (r = 0.372), and the regression line is “y = 0.8x + 1.27”.

Figure 4.

Relationship between the dose and the trough blood level of LCM. (a) The calculated trough blood level and the daily dose (mg/day) have no correlation. (b) The trough blood level and the corrected dose (mg/kg/day) have a subtle positive correlation (r = 0.372), and the regression line is “y = 0.8x + 1.27”.

Figure 5.

Relationship between LCM blood levels and RR. (a) There is no correlation between the actual LCM blood level and RR. (b,c) The calculated peak and trough levels do not correlate with RR. (#) This area includes effective cases with low blood levels, ($) another area includes the cases whose RR was not sufficient to increase with a high dose.

Figure 5.

Relationship between LCM blood levels and RR. (a) There is no correlation between the actual LCM blood level and RR. (b,c) The calculated peak and trough levels do not correlate with RR. (#) This area includes effective cases with low blood levels, ($) another area includes the cases whose RR was not sufficient to increase with a high dose.

Figure 6.

Relationship between LCM blood levels and RR for each seizure type. There is no correlation between the actual LCM blood level and RR of (a) FAS, (b) FIAS, (c) and FBTCS. There are effective cases whose LCM blood levels are low (#). There are low RR cases with an increased LCM dose ($).

Figure 6.

Relationship between LCM blood levels and RR for each seizure type. There is no correlation between the actual LCM blood level and RR of (a) FAS, (b) FIAS, (c) and FBTCS. There are effective cases whose LCM blood levels are low (#). There are low RR cases with an increased LCM dose ($).

Figure 7.

Comparisons of LCM blood levels between the effective and ineffective cases. There is a significant difference between effective and ineffective cases at all points. The optimal range encompasses the range in which the blood levels of the effective cases and the ineffective cases do not overlap. (#) For the actual level, the optimal range is 8.0–10.5 µg/mL. ($) The optimal range of the trough level is 6.5–8.0 µg/mL.

Figure 7.

Comparisons of LCM blood levels between the effective and ineffective cases. There is a significant difference between effective and ineffective cases at all points. The optimal range encompasses the range in which the blood levels of the effective cases and the ineffective cases do not overlap. (#) For the actual level, the optimal range is 8.0–10.5 µg/mL. ($) The optimal range of the trough level is 6.5–8.0 µg/mL.

Figure 8.

Comparisons of LCM blood levels between the effective and ineffective cases with FBTCS. The blood levels at all points of the effective cases are significantly higher than the blood levels of ineffective cases. (#) In the actual level, its optimal range is 7.5–12.0 µg/mL.

Figure 8.

Comparisons of LCM blood levels between the effective and ineffective cases with FBTCS. The blood levels at all points of the effective cases are significantly higher than the blood levels of ineffective cases. (#) In the actual level, its optimal range is 7.5–12.0 µg/mL.

Table 1.

Details of patients on LCM treatment.

Table 1.

Details of patients on LCM treatment.