Submitted:

05 October 2024

Posted:

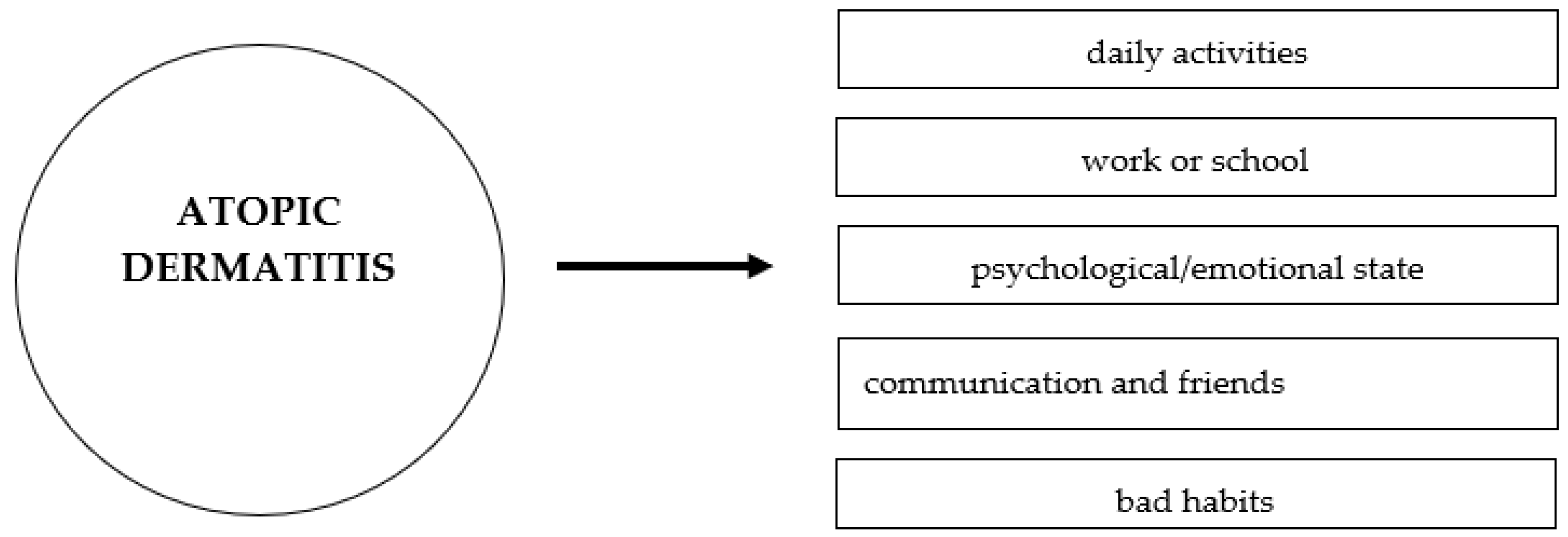

07 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Impact of Atopic Dermatitis on Emotional and Psychological States

3. The Impact of Atopic Dermatitis on Daily Activities, Work Productivity, and Quality of Life

4. Economic Costs of Atopic Dermatitis

5. Standard Therapy and Advanced Treatment Possibilities

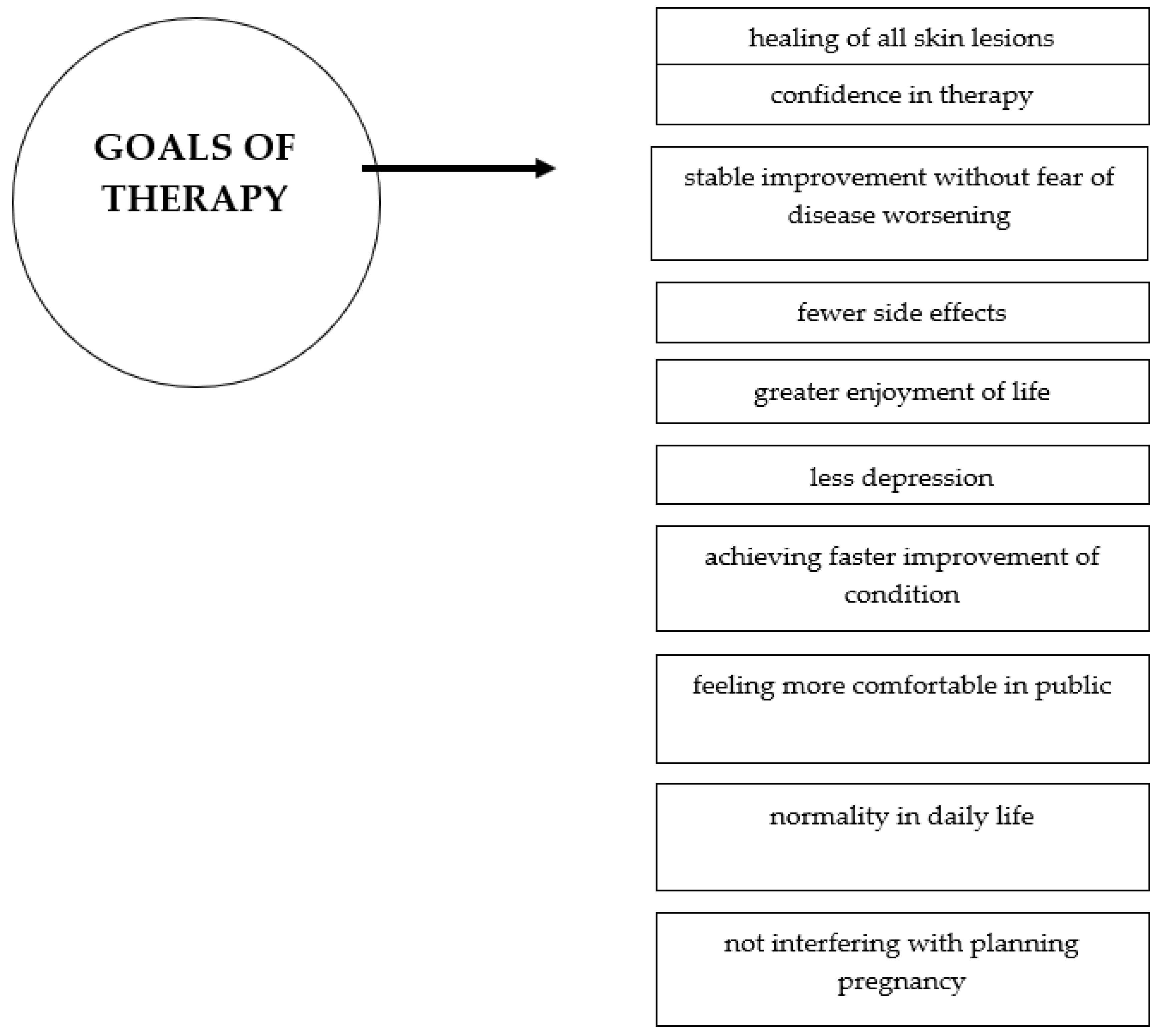

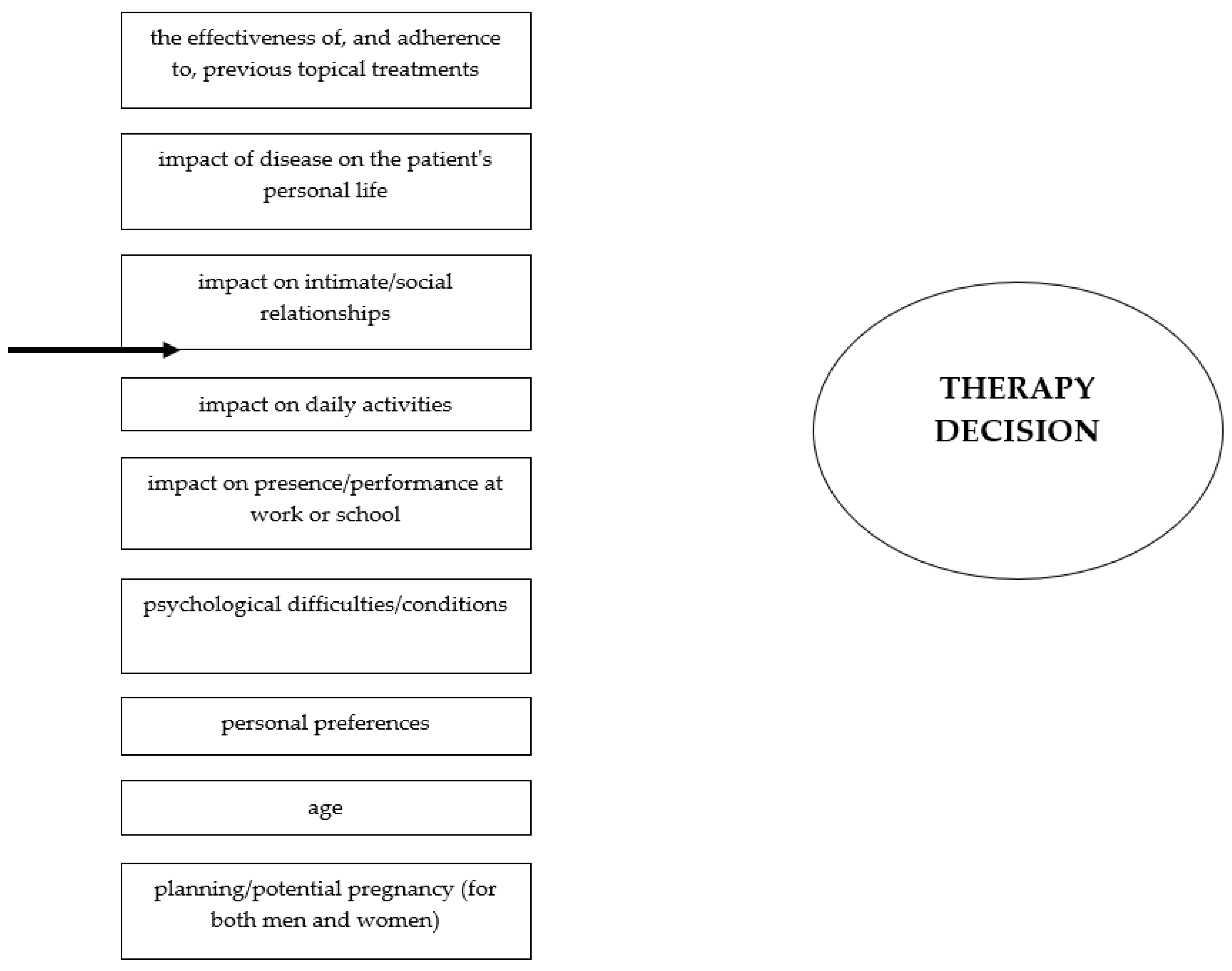

6. Decision to Initiate Systemic Therapy

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russo, F.; Santi, F.; Cioppa, V.; Orsini, C.; Lazzeri, L.; Cartocci, A.; Rubegni, P. Meeting the needs of patients with atopic dermatitis: a multidisciplinary approach. Dermatitis. 2022, 33, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Meštrović-Štefekov, J.; Potočnjak, I.; Cindrić, T.; Ilić, I.; Lovrić, I.; Skalicki, L.; Bešlić, I.; Pondeljak, N. Atopic dermatitis: disease features, therapeutic options, and a multidisciplinary approach. Life (Basel) 2023, 13, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameen, M.; Rabe, A.; Blanthorn-Hazell, S.; Millward, R. Prevalence and clinical profile of atopic dermatitis (AD) in England—a population-based cohort study using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) and Hospital Episode Statistics (HES). Value Health. 2020, 23, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, M.; Langenbruch, A.; Blome, C.; Gutknecht, M.; Werfel, T.; Ständer, S.; Steinke, S.; Kirsten, N.; Silva, N.; Sommer, R. Characterizing treatment-related patient needs in atopic eczema: insights for personalized goal-oriented care. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, A.; Branca, L.; Jeker, F.; Vogt, D.R.; Schwegler, S.; Navarini, A.; Itin, P.; Mueller, S.M. When life is itchy: What harms, helps, and heals from a patient’s perspective? Differences and similarities in skin diseases. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falissard, B.; Simpson, E.L.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Papp, K.A.; Barbarot, S.; Gadkari, A.; Saba, G.; Gautier, L.; Abbe, A.; Eckert, L. Qualitative assessment of adult patients' perceptions of atopic dermatitis using natural language processing analysis in a cross-sectional study. Dermatol. Ther.(Heidelb.). 2020, 10, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Prochnow, T.; Chang, J.; Kim, S.J. Health-related behaviors and psychological status of adolescent patients with atopic dermatitis: a web-based survey of Korean youth risk behavior in 2019. Patient Prefer. Adherence. 2023, 17, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hachem, M.; Di Mauro, G.; Rotunno, R.; Giancristoforo, S.; De Ranieri, C.; Carlevaris, C.M.; Verga, M.C.; Dello Iacono, I. Pruritus in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: a multidisciplinary approach-summary document of the Italian expert group. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2020, 46, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieber, T. Atopic dermatitis: an expanded therapeutic framework for a complex disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Stewart, A.; von Mutius, E.; Cookson, W.; Anderson, H.R. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 121, 947–954.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, J.; Zink, A.; Arents, B.W.M.; Seitz, I.A.; Mensing, U.; Schielein, M.C.; Wettemann, N.; de Carlo, G.; Fink-Wagner, A. Atopic eczema: disease burden and individual suffering—results from a large EU study in adults. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughter, M.R.; Maymone, M.B.C.; Mashayekhi, S.; Arents, B.W.M.; Karimkhani, C.; Langan, S.M.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Flohr, C. The global burden of atopic dermatitis: lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasseeh, A.N.; Elezbawy, B.; Korra, N.; Tannira, M.; Dalle, H.; Aderian, S.; Abaza, S.; Kaló, Z. The burden of atopic dermatitis in adults and adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. Dermatol. Ther. (Heidelb). 2022, 12, 2653–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, C.; Dreher, M.; Weess, H.G.; Staubach, P. Sleep disorders in patients with urticaria and atopic dermatitis: an underestimated burden. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2020, 100, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.J.; Uddin, M.J.; Saha, S.K.; Darmstadt, G.L. Prevalence and psychosocial impact of atopic dermatitis in Bangladeshi children and families. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0249824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marron, S.E.; Cebrian-Rodriguez, J.; Alcalde-Herrero, V.M.; Garcia-Latasa de Aranibar, F.J.; Tomas-Aragones, L. Psychosocial impact of atopic dermatitis in adults: a qualitative study. Actas Dermosfiliogr. (Engl Ed). 2020, 111, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devleesschauwer, B.; Maertens de Noordhout, C.; Smit, G.S.; Duchateau, L.; Dorny, P.; Stein, C.; Van Oyen, H.; Speybroeck, N. Quantifying the burden of disease to support public health policy in Belgium: opportunities and limitations. BMC Public Health. 2014, 14, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworek, A.K.; Jaworek, M.; Szafraniec, K.; Wojas-Pelc, A.; Szepietowski, J.C. Melatonin and sleep disorders in patients with severe atopic dermatitis. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2021, 38, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bešlić, I.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Vrtarić, A.; Bešlić, A.; Škrinjar, I.; Hanžek, M.; Crnković, D.; Artuković, M. Melatonin in dermatologic allergic diseases and other skin conditions: current trends and reports. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.H.; Attarian, H.; Zee, P.; Silverberg, J.I. Burden of sleep and fatigue in US adults with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2016, 27, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meštrović-Štefekov, J.; Novak-Bilić, G.; Kuna, M.; Pap, N.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Psychological stress in patients with atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2018, 26, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, B.; Lee, S.H.; Park, Y.L. Psychological health status and health-related quality of life in adults with atopic dermatitis: a national cross-sectional study in South Korea. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2018, 98, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi, A.; Fujita, H.; Arima, K.; Inoue, T.; Dorey, J.; Fukushima, A.; Taguchi, Y. Health-care resource use and current treatment of adult atopic dermatitis patients in Japan: A retrospective claims database analysis. J. Dermatol. 2019, 46, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Lei, D.; Yousaf, M.; Janmohamed, S.R.; Vakharia, P.P.; Chopra, R.; Chavda, R.; Gabriel, S.; Patel, K.R.; Singam, V.; et al. Association of atopic dermatitis severity with cognitive function in adults. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arima, K.; Gupta, S.; Gadkari, A.; Hiragun, T.; Kono, T.; Katayama, I.; Demiya, S.; Eckert, L. The burden of atopic dermatitis among Japanese adults: an analysis of data from the 2013 National Health and Wellness Survey. J. Dermatol. 2018, 45, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, L.; Gupta, S.; Gadkari, A.; Mahajan, P.; Gelfand, J.M. Disease burden in adults with atopic dermatitis: analysis of survey data from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbabi, M.; Zhand, N.; Samadi, Z.; Ghaninejad, H.; Golestan, B. Psychiatric comorbidity and quality of life in patients with dermatological diseases. Iran J. Psychiatry. 2009, 4, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, J.A.; Park, E-C. ; Lee, M.; Yoo, K-B.; Park, S. Does stress increase the risk of atopic dermatitis in adolescents? Results of the Korean Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey (KYRBWS-VI). PLoS One. 2013, 8, e67890. [Google Scholar]

- Schut, C.; Weik, U.; Tews, N.; Gieler, U.; Deinzer, R.; Kupfer, J. Psychophysiological effects of stress management in patients with atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2013, 93, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Meštrović-Štefekov, J.; Cvitanović, H.; Bulat, V.; Duvančić, T.; Pondeljak, N.; Tolušić-Levak, M.; Lazić-Mosler, E.; Novak-Bilić, G. The COVID-19 pandemic and recent earthquake in Zagreb together significantly increased the disease severity of patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 239(1), 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C. Factors affecting life satisfaction among adolescents with atopic dermatitis. Stud. Korean Youth. 2015, 26, 111–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu, J.K.; Wu, K.K.; Bui, T.-L.; Armstrong, A.W. Association between atopic dermatitis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pondeljak, N.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Stress-induced interaction of skin immune cells, hormones, and neurotransmitters. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Meštrović-Štefekov, J.; Ferček, I.; Pondeljak, N.; Lazić-Mosler, E.; Gašić, A. Atopic dermatitis severity, patient perception of the disease, and personality characteristics: how are they related to quality of life? Life (Basel). 2021, 11, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanbaeva, D.G.; Dentener, M.A.; Creutzberg, E.C.; Wesseling, G.; Wouters, E.F. Systemic effects of smoking. Chest. 2007, 131, 1557–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, U.; Lemmen, C.; Behrendt, H.; Link, E.; Schäfer, T.; Gostomzyk, J.; Scherer, G.; Ring, J. The impact of environmental tobacco smoke on eczema and allergic sensitization in children. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 150, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, J.; Thyssen, J.; Basketter, D.; Puangpet, P.; Kimber, I. T-helper 2 immune skewing in pregnancy/early life: chemical exposures and development of atopic disease and allergy. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 172, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, C.; Ishida, Y.; Kitoh, A.; Otsuka, A.; Kabashima, K. Interaction of peripheral nerves and mast cells, eosinophils, and basophils in the development of pruritus. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 1405–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-B.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang R, Wang, Y.C.; Li, J.B.; Mu, D. The posterior thalamic nucleus mediates histaminergic itch of the face. Neuroscience. 2020, 444, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.; Koo, J.; Lim, S.K. Association between stress and physical activity in Korean adolescents with atopic dermatitis based on the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey 2018-2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 8175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mücke, M.; Ludyga, S.; Colledge, F.; Gerber, M. The impact of regular physical activity and fitness on stress reactivity measured using the Trier Social Stress Test protocol: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2607–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Dougherty, M.; Hearst, M.O.; Syed, M.; Kurzer, M. S:; Schmitz, K.H. Life events, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms in a physical activity intervention for young adult women. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2012, 5, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murota, H.; Yamaga, K.; Ono, E.; Murayama, N.; Yokozeki, H.; Katayama, I. Why does sweat lead to itching in atopic dermatitis? Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 1416–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koszorú, K.; Borza, J.; Gulácsi, L.; Sárdy, M. Quality of life of patients with atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2019, 104, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zuberbier, T.; Orlow, S.J.; Paller, A.S.; Taïeb, A.; Allen, R.; Hernanz-Hermosa, J.M.; Ocampo-Candiani, J.; Cox, M.; Langeraar, J.; Simon, J.C. Patient perspectives on the management of atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japundžić, I.; Bembić, M.; Špiljak, B.; Parać, E.; Macan, J.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Work-Related Hand Eczema in Healthcare Workers: Etiopathogenic Factors, Clinical Features, and Skin Care. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Ferček, I.; Duvančić, T.; Bulat, V.; Ježovita, J.; Novak-Bilić, G.; Šitum, M. Occupational contact dermatitis amongst dentists and dental technicians. Acta Clin. Croat. 2016, 55, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Ghorayeb, E.; Andria, M.; Walker, V.; Schnitzer, J.; Kennedy, M.; Chen, Z.; Belland, A.; White, J.; Silverberg, J.I. Real-world study evaluating the adequacy of existing systemic treatments for patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (QUEST-AD): baseline treatment patterns and unmet needs assessment. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 123, 381–388.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, L.; Gupta, S.; Amand, C.; Gadkari, A.; Mahajan, P.; Gelfand, J.M. The burden of atopic dermatitis in adults in the United States: data on healthcare resource utilization from the 2013 National Health and Wellness Survey. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariëns, L.F.M.; Van Nimwegen, K.J.M.; Shams, M.; De Bruin, D.T.; Van der Schaft, J.; Van Os-Medendorp, H.; De Bruin-Weller, M. Economic burden of adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis indicated for systemic treatment. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2019, 99, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murota, H.; Inoue, S.; Yoshida, K.; Ishimoto, A. Cost-of-illness study for adult atopic dermatitis in Japan: a cross-sectional web-based survey. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, P.H.; Vo, T.Q. Economic burden and productivity loss associated with eczema: a prevalence-based follow-up study in Vietnam. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2019, 69, S57–S63. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Chu, C.; Cho, Y.; Lee, C.; Tsai, C.; Tang, C. PSY11 Work productivity and activity impairment among patients with atopic dermatitis in Taiwan. Value Health. 2019, 22, S376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenbruch, A.; Radtke, M.; Franzke, N.; Ring, J.; Foelster-Holst, R.; Augustin, M. Quality of healthcare for atopic eczema in Germany: results of the national health study AtopicHealth. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 28, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzedine, K.; Shourick, J.; Merhand, S.; Sampogna, F.; Taïeb, C. Impact of atopic dermatitis in adolescents and their parents: a French study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2020, 100, 00294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.; Nyeland, M.E.; Nyberg, F. Increasing severity of atopic dermatitis is associated with a negative impact on work productivity among adults with atopic dermatitis in France, Germany, the UK, and the USA. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, N.; Saeki, H.; Kataoka, Y.; Etoh, T.; Teramukai, S.; Takagi, H.; Tajima, Y.; Ardeleanu, M.; Rizova, E.; Arima, K. Adult Atopic Dermatitis Disease Registry in Japanese patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (ADDRESS-J): baseline characteristics, treatment history, and disease burden. J. Dermatol. 2019, 46, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalom, G.; Babaev, M.; Kridin, K.; Schonmann, Y.; Horev, A.; Dreiher, J.; Cohen, A.D. Health service utilization by 116,816 patients with atopic dermatitis in Israel. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2019, 99, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, L.; Gupta, S.; Amand, C.; Gadkari, A.; Mahajan, P.; Gelfand, J.M. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life and productivity in adults in the United States: analysis using the National Health and Wellness Survey. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 274–279e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicras-Mainar, A.; Navarro-Artieda, R.; Carrillo, J.C. Economic impact of atopic dermatitis in adults: a population-based study (IDEA study). Actas Dermosifiliogr. (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 109, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieris-Hirche, J.; Gieler, U.; Petrak, F.; Milch, W.; Te Wildt, B.; Dieris, B.; Herpertz, S. Suicidal ideation in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a German cross-sectional study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2017, 97, 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girolomoni, G.; Luger, T.; Nosbaum, A.; Gruben, D.; Romero, W.; Llamado, LJ.; DiBonaventura, M. Economic and psychosocial burden of comorbidities in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in Europe: a cross-sectional survey analysis. Dermatol Ther.(Heildeb.). 2020, 11, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drucker, A.M.; Qureshi, A.A.; Amand, C.; Villeneuve, S.; Gadkari, A.; Chao, J.; Kuznik, A.; Bégo-Le-Bagousse, G.; Eckert, L. Healthcare resource utilization and costs among adults with atopic dermatitis in the United States: a claims-based analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 1342–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Launois, R.; Ezzedine, K.; Cabout, E.; Reguai, Z.; Merrhand, S.; Heas, S.; Seneschal, J.; Misery, L.; Taieb, C. The importance of out-of-pocket costs for adult patients with atopic dermatitis in France. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 1921–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väkevä, L.; Niemelä, S.; Lauha, M.; Pasternack, R.; Hannuksela-Svahn, A.; Hjerppe, A.; Joensuu, A.; Soronen, M.; Ylianttila, L.; Pastila, R.; et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy improves quality of life in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis up to 3 months: results of an observational multicenter study. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2019, 35, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schild, M.; Weber, V.; Galetzka, W.; Enders, D.; Zügel, F.S.; Gothe, H. Health resource utilization and associated costs among patients with atopic dermatitis—a retrospective cohort study based on German health claims data. Value Health. 2020, 23, S745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, B.; Blaiss, M.S. The burden of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018, 39, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollenberg, A.; Barbarot, S.; Bieber, T.; Christen-Zaech, S.; Deleuran, M.; Fink-Wagner, A.; Gieler, U.; Girolomoni, G.; Lau, S.; Muraro, A.; et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: Part I. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 657–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Howe, W. Atopic dermatitis (eczema): pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/atopic-dermatitis-eczema-pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Silverberg, J.I.; Gooderham, M.; Katoh, N.; Aoki, V.; Pink, A.E.; Binamer, Y.; Rademaker, M.; Fomina, D.; Gutermuth, J.; Ahn, J.; et al. Combining treat-to-target principles and shared decision-making: International expert consensus-based recommendations with a novel concept for minimal disease activity criteria in atopic dermatitis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.L.; Bruin-Weller, M.; Flohr, C.; Ardern-Jones, M.R.; Barbarot, S.; Deleuran, M.; Bieber, T.; Vestergaard, C.; Brown, S.J.; Cork, M.J.; et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the International Eczema Council. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojanova, M.; Tanczosova, M.; Strosova, D.; Cetkovska, P.; Fialova, J.; Dolezal, T.; Machovcova, A.; Gkalpakiotis, S. BIOREP Study Group. Dupilumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: Real-world data from the Czech Republic BIOREP registry. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 2578–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, T.G. Evaluation and management of severe refractory atopic dermatitis (eczema) in adults. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-and-management-of-severe-refractory-atopic-dermatitis-eczema-in-adults#H1361784051 (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Lauffer, F.; Biedermann, T. Einschätzungen zur Therapie der moderaten bis schweren atopischen dermatitis mit januskinaseinhibitoren [Janus kinase inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis-evaluation of current data and practical experience]. Dermatologie (Heidelb.). 2022, 73, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thyssen, J.P.; Werfel, T.; Barbarot, S.; Hunter, H.J.A.; Pierce, E.; Sun, L.; Cirri, L.; Buchanan, A.S.; Lu, N.; Wollenberg, A. Maintained improvement in physician- and patient-reported outcomes with baricitinib in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis who were treated for up to 104 weeks in a randomized trial. J. Dermatolog Treat. 2023, 34, 2190430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pols, D. H.; Wartna, J. B.; Moed, H.; van Alphen, E. I.; Bohnen, A. M.; Bindels, P. J. Atopic dermatitis, asthma and allergic rhinitis in general practice and the open population: a systematic review. Scan J Prim Health Care 2016, 34(2), 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelava, N.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Duvančić, T.; Romić, R.; Šitum, M. Oral allergy syndrome--the need of a multidisciplinary approach. Acta Clin. Croat. 2014, 53, 210–219. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Milam, E.C. Comorbid scenarios in contact dermatitis: atopic dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, and extremes of age. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024, 12(9), 2243–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).