Submitted:

03 October 2024

Posted:

08 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moschovi M, Chrousos G. Pineal gland masses. In: UpToDate. Eichler AF (Deputy Editor), Wolters Kluwer. Accessed December 28th, 2023.

- Lombardi G, Poliani PL, Manara R, Berhouma M, Minniti G, Tabouret E, Razis E, Cerretti G, Zagonel V, Weller M, Idbaih A. Diagnosis and Treatment of Pineal Region Tumors in Adults: A EURACAN Overview. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Jul 27;14(15):3646. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil M, Karandikar M. Papillary tumor of pineal region: A rare entity. Asian J Neurosurg. 2016 Oct-Dec;11(4):453. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottolese C, Szathmari A, Beuriat PA. Incidence of pineal tumors. A review of the literature. Neurochirurgie. 2015 Apr-Jun;61(2-3):65-9. Epub 2014 Aug 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fèvre-Montange M, Hasselblatt M, Figarella-Branger D, Chauveinc L, Champier J, Saint-Pierre G, Taillandier L, Coulon A, Paulus W, Fauchon F, Jouvet A. Prognosis and histopathologic features in papillary tumors of the pineal region: a retrospective multicenter study of 31 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006 Oct;65(10):1004-11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaki VN, Solla DJF, Ribeiro RR, da Silva SA, Teixeira MJ, Figueiredo EG. Papillary Tumor of the Pineal Region: Systematic Review and Analysis of Prognostic Factors. Neurosurgery. 2019 Sep 1;85(3):E420-E429. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez D, Parsons DW. Pineal Tumors. American Brain Tumor Association. October, 2023. Accessed August 4th, 2024. Available online: https://www.abta.org/tumor_types/pineal-tumors/.

- Lancia A, Becherini C, Detti B, Bottero M, Baki M, Cancelli A, Ferlosio A, Scoccianti S, Sun R, Livi L, Ingrosso G. Radiotherapy for papillary tumor of the pineal region: A systematic review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020 Mar;190:105646. Epub 2019 Dec 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favero G, Bonomini F, Rezzani R. Pineal Gland Tumors: A Review. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Mar 27;13(7):1547. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami B, Lyman J, Brown A, Coia L, Goitein M, Munzenrider JE, Shank B, Solin LJ, Wesson M. Tolerance of normal tissue to therapeutic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991 May 15;21(1):109-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks LB, Yorke ED, Jackson A, Ten Haken RK, Constine LS, Eisbruch A, Bentzen SM, Nam J, Deasy JO. Use of normal tissue complication probability models in the clinic. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 Mar 1;76(3 Suppl):S10-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding L, McFarlane J, Honey CR, McDonald PJ, Illes J. Mapping the Landscape of Equitable Access to Advanced Neurotechnologies in Canada. Can J Neurol Sci. 2023 Jun;50(s1):s17-s25. Epub 2023 May 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauchon F, Hasselblatt M, Jouvet A, Champier J, Popovic M, Kirollos R, Santarius T, Amemiya S, Kumabe T, Frappaz D, Lonjon M, Fèvre Montange M, Vasiljevic A. Role of surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy in papillary tumors of the pineal region: a multicenter study. J Neurooncol. 2013 Apr;112(2):223-31. Epub 2013 Jan 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicka E, Bobek-Billewicz B, Szymaś J, Tarnawski R. Late dissemination via cerebrospinal fluid of papillary tumor of the pineal region: a case report and literature review. Folia Neuropathol. 2016;54(1):72-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffenoir K, Rigoard P, Wager M, Ferrand S, Coulon A, Blanc JL, Bataille B, Listrat A. Papillary tumor of the pineal region in a child: case report and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008 Mar;24(3):379-84. Epub 2007 Oct 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epari S, Bashyal R, Malick S, Gupta T, Moyadi A, Kane SV, Bal M, Jalali R. Papillary tumor of pineal region: report of three cases and review of literature. Neurol India. 2011 May-Jun;59(3):455-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choque-Velasquez J, Colasanti R, Resendiz-Nieves J, Jahromi BR, Tynninen O, Collan J, Niemelä M, Hernesniemi J. Papillary Tumor of the Pineal Region in Children: Presentation of a Case and Comprehensive Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2018 Sep;117:144-152. Epub 2018 Jun 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pons-Escoda A, Sánchez Fernández JJ, de Vilalta À, Vidal N, Majós C. High Myoinositol on Proton MR Spectroscopy Could Be a Potential Signature of Papillary Tumors of the Pineal Region-Case Report of Two Patients. Brain Sci. 2022 Jun 19;12(6):802. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesny E, Lesueur P. Radiotherapy for rare primary brain tumors. Cancer Radiother. 2023 Sep;27(6-7):599-607. Epub 2023 Jul 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Majdoub F, Blau T, Hoevels M, Bührle C, Deckert M, Treuer H, Sturm V, Maarouf M. Papillary tumors of the pineal region: a novel therapeutic option-stereotactic 125iodine brachytherapy. J Neurooncol. 2012 Aug;109(1):99-104. Epub 2012 Apr 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment Parameter | Definition |

|---|---|

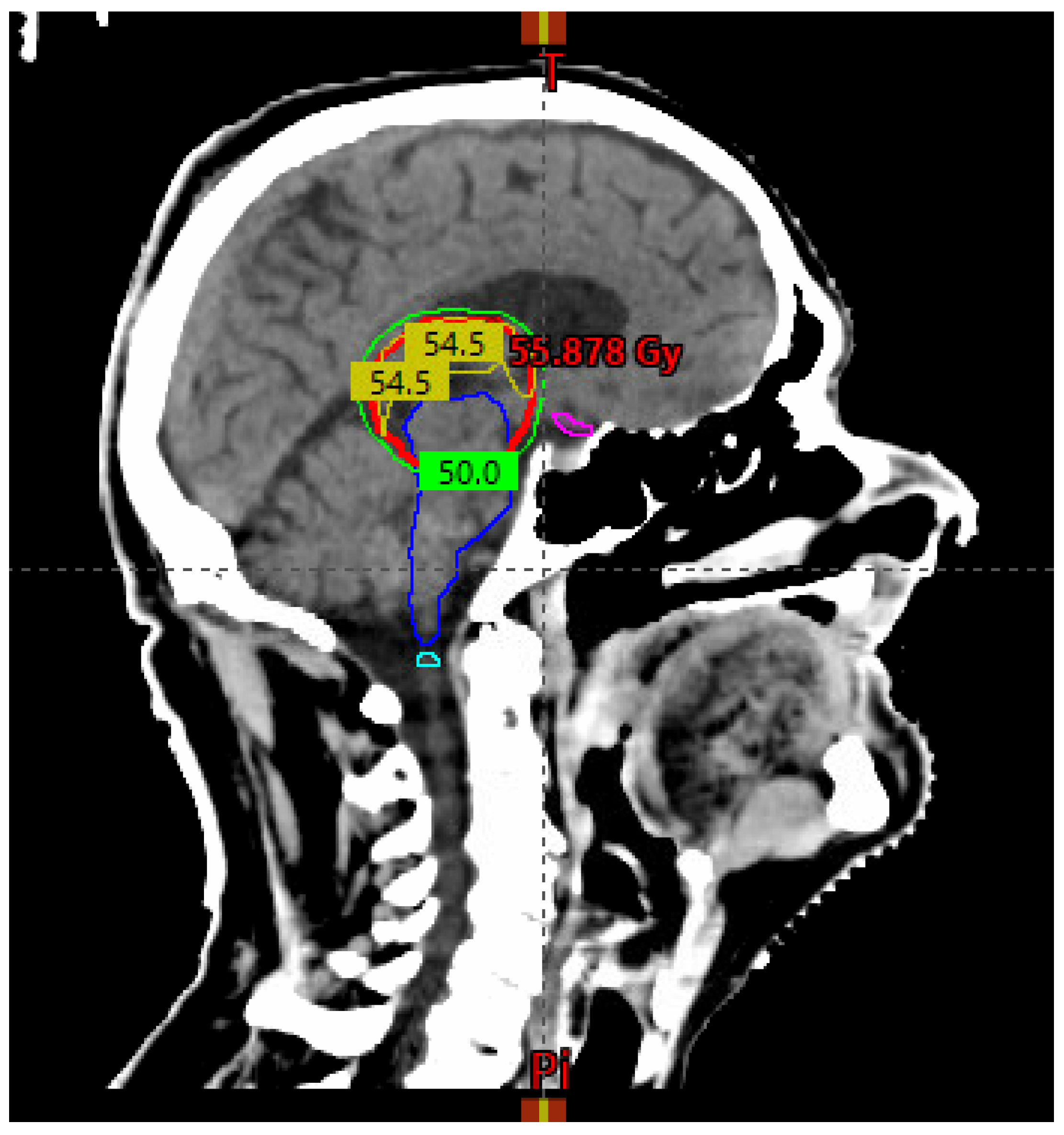

| GTV | Residual disease based on pre-and post-op imaging |

| CTV | GTV + tumor bed on planning CT and MRI + 5 mm margin cropped to anatomic boundaries* |

| PTV | CTV + 5 mm concentric margin |

| Dose and fractionation | 54 Gy / 30 fractions delivered Monday to Friday over six weeks in 1.8 Gy once daily fractions |

| Organs at risk | Dose constraint (to organ at risk + 3 mm concentric margin) |

|---|---|

| Brainstem | V54 Gy < 0.03 cc |

| Spinal cord | V45 Gy < 0.03 cc |

| Optic chiasm | V54 Gy < 0.03 cc |

| Optic nerves | V54 Gy < 0.03 cc |

| Brain | V60Gy < 33%, V50Gy < 66% |

| Eyes | V45 Gy < 0.03 cc |

| Author | Year | Publication Type | # Patients | Surgery Type | Adj RT Dose/Fractionation | RT Volumes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffenoir et al. [15] | 2008 | Case Report | 1 | GTR | 50 Gy / 1.86 Gy per fraction. Five fractions per week | "Tumor bed plus wall of third ventricle" |

| Epari et al. [16] | 2011 | Case Report | 2 | GTR (both patients) | 54 Gy / 30 fractions (both patients) | "Local radiation" |

| Lancia et al. [8] | 2017 | Case Report | 1 | Recurrent disease. STR | 59.4 Gy / 33 fractions. Five fractions per week | CTV = contrast-enhanced lesion + 5 mm margin, PTV = 3 mm expansion of CTV |

| Choque-Velasques et al. [17] | 2018 | Case Report | 1 | GTR | 54 Gy divided into daily doses of 1.8 Gy | "Focal RT to the pineal tumor bed" |

| Pons-Escoda et al. [18] | 2022 | Case Report | 1 | STR | 50 Gy / 25 fractions | "Enhancing area (on post-op MRI)" |

| Lombardi et al. [2] | 2022 | Review Article | NA | RT indicated for STR or recurrent tumors | 50.4-54 Gy in 1.8-2 Gy fractions | “Focal RT” |

| Mesny et al. [19] | 2023 | Review Article | NA | RT indicated for STR or recurrent tumors | 50.4-54 Gy in 1.8-2 Gy fractions | GTV = post-operative cavity and any residual lesion.CTV = margins are undefined |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).