Submitted:

03 October 2024

Posted:

04 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Vitamin D Presentation to the Colon

Colon Mucosal Metabolism of Vitamin D

Absorption Properties of Colon Mucosa

Colon Absorption of Vitamin D Metabolites

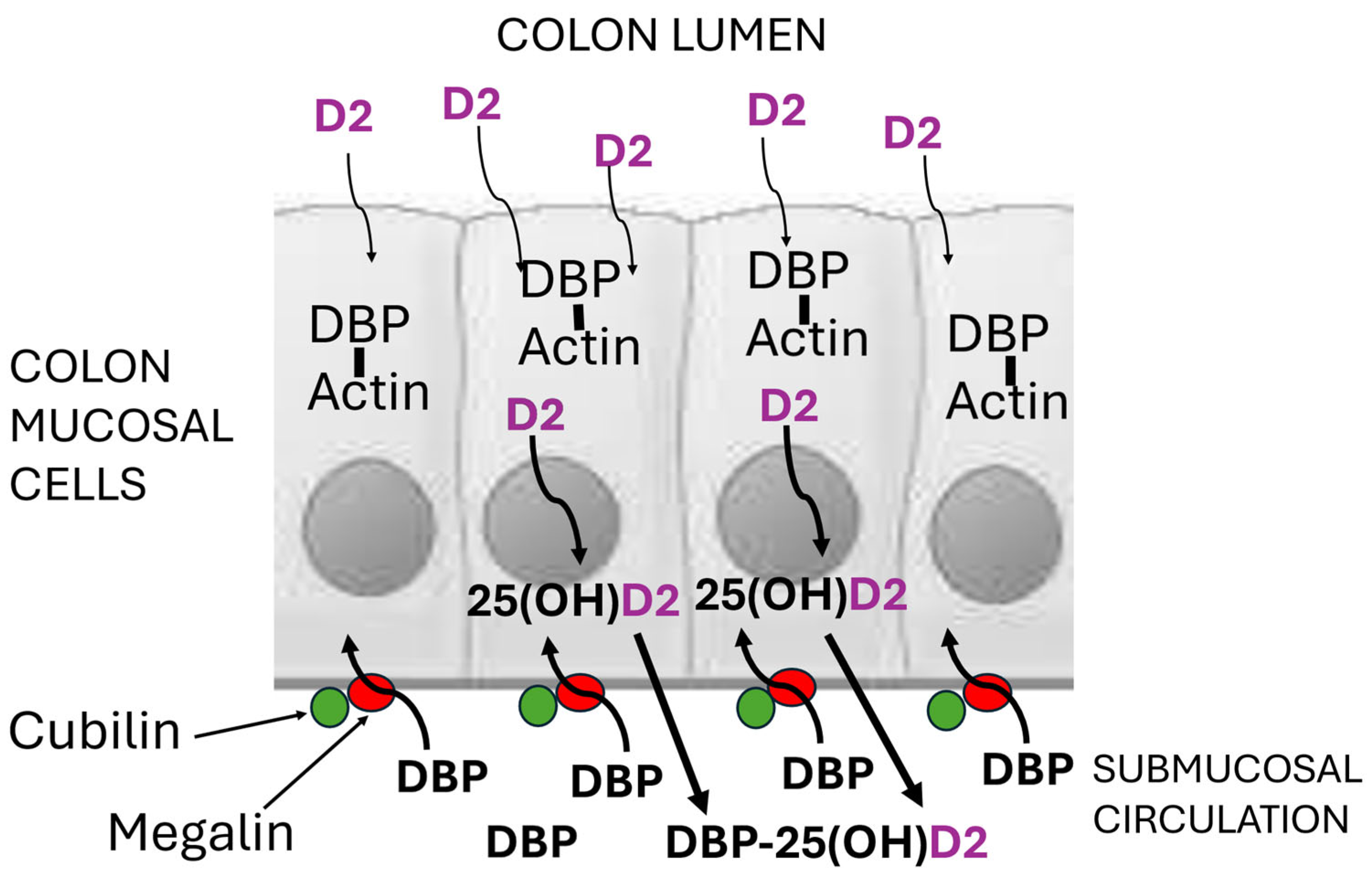

Absorption Mechanism for Vitamin D2 in Colon Mucosal Cells

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reboul, E. Proteins involved in fat-soluble vitamin and carotenoid transport across the intestinal cells: New insights from the past decade. Progress Lipid Res. 2023, 89, 101208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Huang, S.; Yang, N.; Cao, A.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, G.; Ma, Q. Porcine bile acids promote the utilization of fat and vitamin A under low-fat diets. Front. Nutr. 2022, 28, 1005195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.; Tso, P. Vitamin A uptake from foods. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2003, 14, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelsen, O. The relationship between ultraviolet radiation exposure and vitamin D status. Nutrients 2010, 2, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustina, A.; Bilezikian, J.P.; Adler, R.A.; Banfi, G.; Bikle, D.D.; Binkley, N.C.; Bollerslev, J.; Bouillon, R.; Brandi, M.L.; Casanueva, F.F.; et al. Consensus statement on vitamin D status assessment and supplementation: Whys, Whens, and Hows. Endocr. Rev. 2024, bnae009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

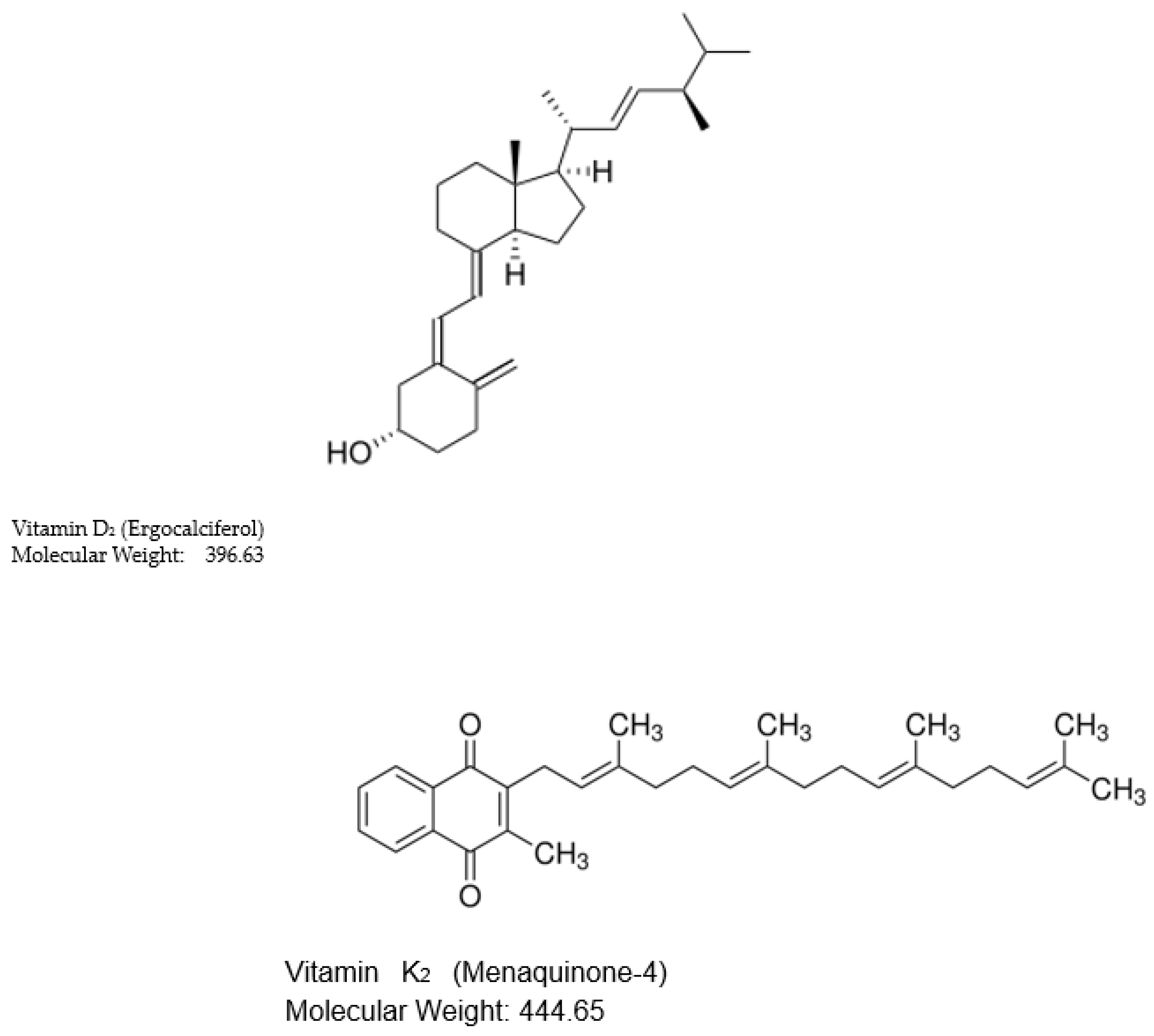

- Paliu, J.-A.; Bita, A.; Diaconu, M.; Tica, A.-A. Quantitative analysis of vitamin D2 and ergosterol in yeast-based supplements using high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2024, 50, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripkovic, L.; Lambert, H.; Hart, K.; Smith, C.P.; Bucca, G.; Penson, P.; Chope, G.; Hyppönen, E.; Berry, J.; Vieth, R.; et al. Comparison of vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplementation in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, R.D.; Garcia, F.G.; Hegsted, D.M.; Kaplinsky, N. Vitamins D2 and D3 in new world primates: influence on calcium absorption. Science 1967, 157, 943–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, L.R.; Bucca, G.; Hesketh, A.; Möller-Levet, C.; Tripkovic, L.; Wu, H.; Hart, K.H.; Mathers, J.C.; Elliott, R.M.; Lanham-New, S.A.; et al. Vitamins D(2) and D(3) have overlapping but different effects on the human immune system revealed through analysis of the blood transcriptome. Front. Immunol. 2022, 24, 790444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarpeykan, S.; Gee, E.K.; Thompson, K.G.; Dittmer, K.E. Undetectable vitamin D3 in equine skin irradiated with ultraviolet light. J. Equine Sci. 2022, 33, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs-Sanford, S.E.; Kiso, W.K.; Schmitt, D.L. Serum vitamin D and selected biomarkers of calcium homeostasis in Asian elephants (Ellephas maximus) managed at a low latitude. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2024, 55, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäpelt, R.B.; Didion, T.; Smedsgaard, J.; Jakobsen, J. Seasonal variation of provitamin D2 and vitamin D2 in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 10907–10912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, A.V.; Rybchyn, M.S.; Mason, R.S.; Fraser, D.R. Short communication: Metabolic synthesis of vitamin D2 by the gut microbiome. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2024, 295, 111666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, E.; James, A.P.; Cunningham, J.; Strobel, N.; Lucas, R.M.; Kiely, M.; Nowson, C.A.; Rangan, A.; Adorno, P.; Atyeo, P.; Black, L.J. Vitamin D composition of Australian foods. Food Chem. 2021, 358, 129836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.-G. Vitamin D receptor influences intestinal barriers in health and disease. Cells 2022, 11, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeker, S.; Seamons, A.; Maggio-Price, L.; Paik, J. Protective links between vitamin D, inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 933–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantieghem, K.; Overbergh, L.; Carmeliet, G.; De Haes, P.; Bouillon, R.; Segaert, S. UVB-induced 1,25(OH)2D3 production and vitamin D activity in intestinal CaCo-2 cells and in THP-1 macrophages pretreated with a sterol Delta7-reductase inhibitor. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006, 99, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagishetty, V.; Chun, R.F.; Liu, N.Q.; Lisse, T.S.; Adams, J.S.; Hewison, M. 1alpha-hydroxylase and innate immune responses to 25-hydroxyvitamin D in colonic cell lines. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 121, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, H.S.; Nittke, T.; Kallay, E. Colonic vitamin D metabolism: implications for the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 347, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzelmann, K. ; Mall. M. Electrolyte transport in the mammalian colon: mechanisms and implications for disease. Physiol. Rev. 2002; 82, 245–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosu, M.; Begari, E. Vitamin K2 in electron transport system: are enzymes involved in vitamin K2 biosynthesis promising drug targets? Molecules 2010, 15, 1531–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, J.P.; Meydani, M.; Barnett, J.B.; Vanegas, S.M.; Barger, K.; Fu, X.; Goldin, B.; Kane, A.; Rasmussen, H.; Vangay, P.; et al. Fecal concentrations of bacterially derived vitamin K forms are associated with gut microbiota composition but not plasma or fecal cytokine concentrations in healthy adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichihashi, T.; Takagishi, Y.; Uchida, K.; Yamada, H. Colonic absorption of menaquinone-4 and menaquinone-9 in rats. J. Nutr. 1992, 122, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groenen-van Dooren, M.M.C.L.; Ronden, J.E.; Soute, B.A.M.; Vermeer, C. Bioavailability of phylloquinone and menaquinones after oral and colorectal administration in vitamin K-deficient rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995, 50, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

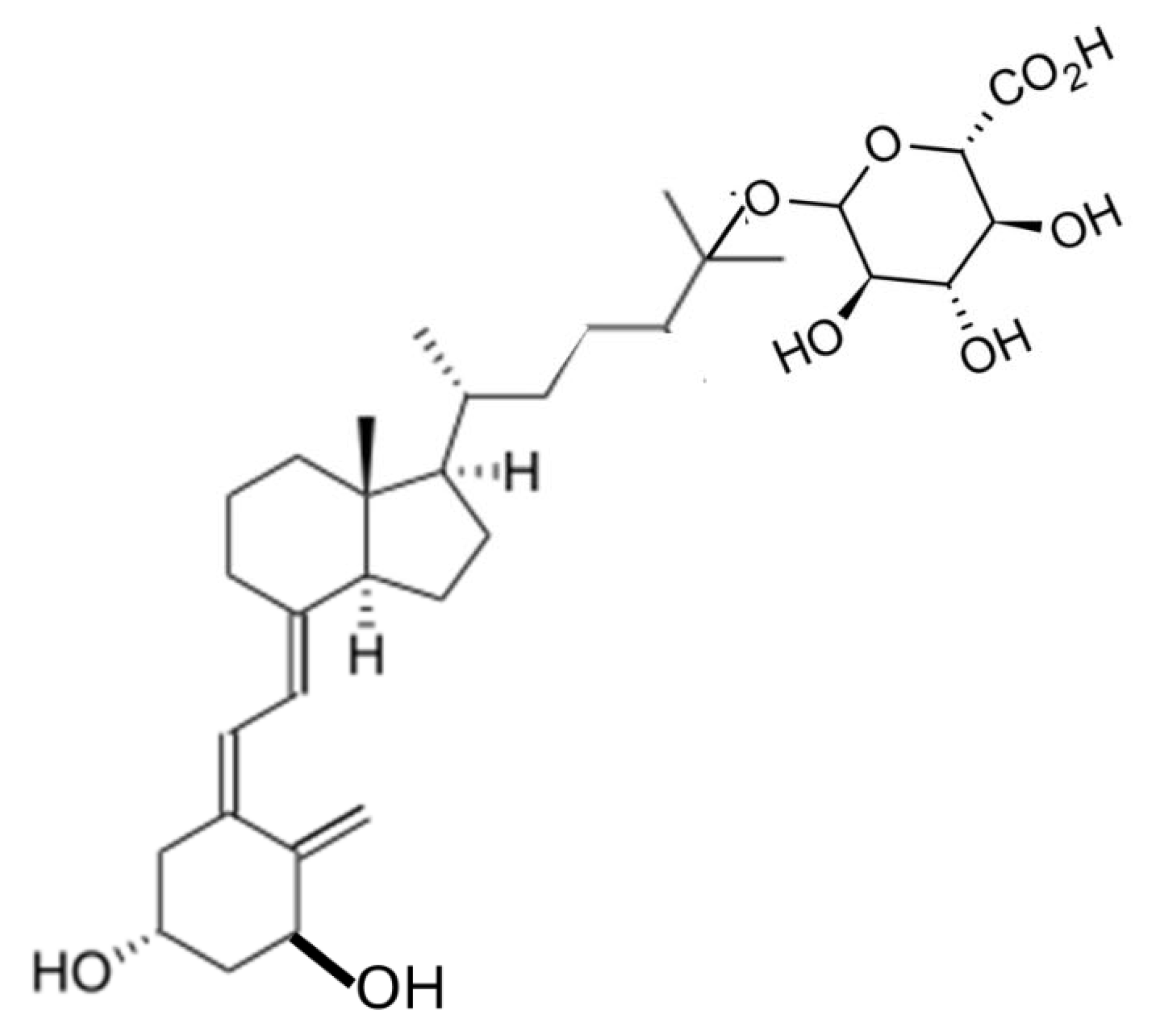

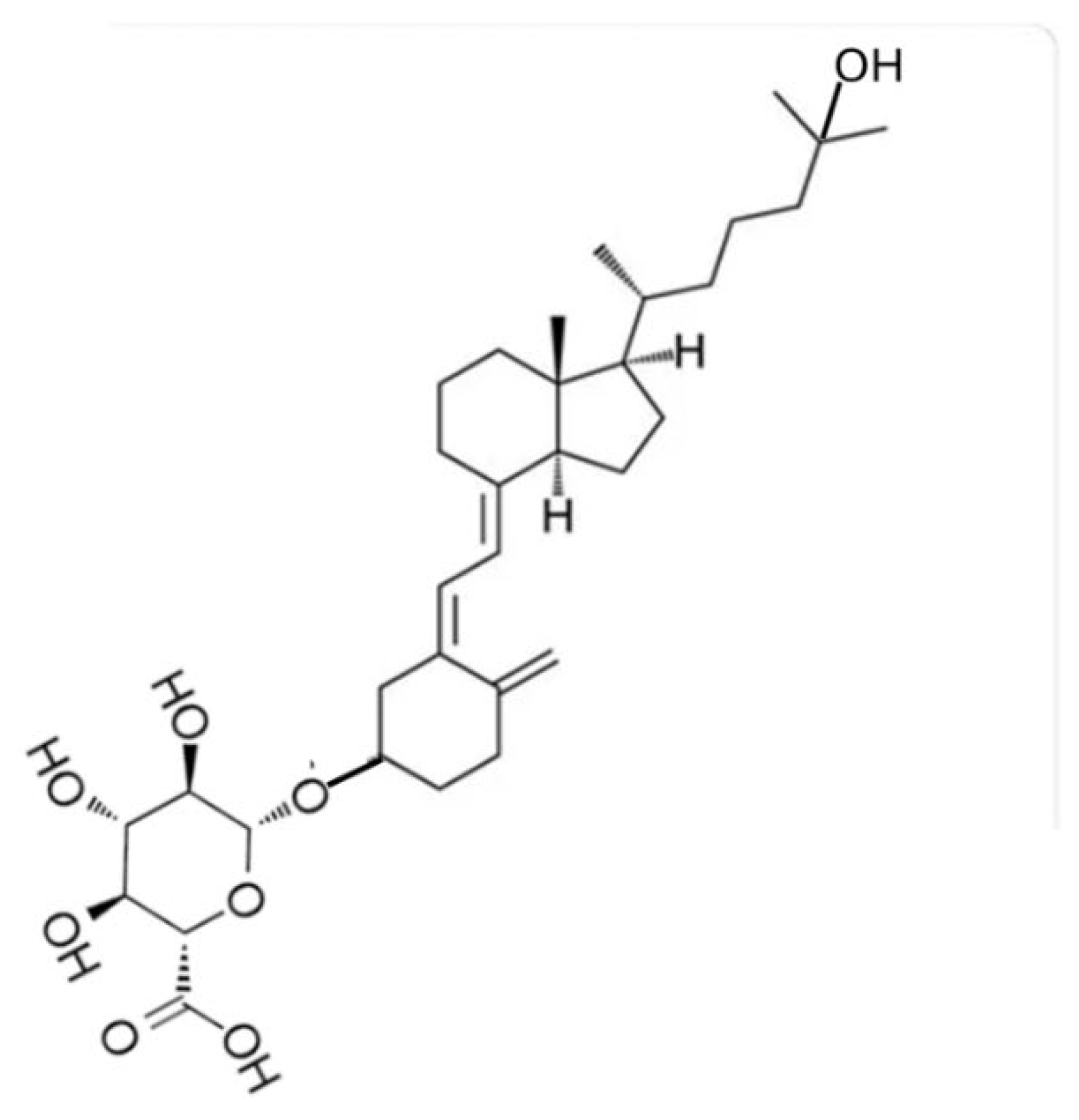

- Goff, J.P.; Koszewski, N.J.; Haynes, J.S.; Horst, R.L. Targeted delivery of vitamin D to the colon using β-glucuronides of vitamin D: therapeutic effects in a murine model of inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 302, G460–G469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszewski, N.J.; Horst, R.L.; Goff, J.P. Importance of apical membrane delivery of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 to vitamin D-responsive gene expression in the colon. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 303, G870–G878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.J.; Koszewski, N.J.; Horst, R.L.; Beitz, D.C.; Goff, J.P. Role of glucuronidated 25-hydroxyvitamin D on colon gene expression in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2020, 319, G253–G260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, S.B.; Goldsmith, R.S.; Lambert, P.W.; Go, V.L. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3: evidence of an enterohepatic circulation in man. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1975, 149, 570–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, P.A.; Kodicek, E. Investigations on metabolites of vitamin D in rat bile. Separation and partial identification of a major metabolite. Biochem. J. 1969, 115, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.R.; Chalmers, T.M.; Fraser, D.R. Enterohepatic circulation of vitamin D: a reappraisal of the hypothesis. Lancet. 1984, 323, 1376–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D.R. Physiological significance of vitamin D produced in skin compared with oral vitamin D. J. Nutr. Sci. 2022, 21, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Schuit, F.; Antonio, L.; Rastinejad, F. Vitamin D binding protein: a historic overview. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2020, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouillon, R.; van Baelen, H.; de Moor, P. Comparative study of the affinity of the serum vitamin D-binding protein. J. Steroid Biochem. 1980. 13, 1029–1034. [CrossRef]

- Teegarden, D.; Meredith, S.C.; Sitrin, M.D. Determination of the affinity of vitamin D metabolites to serum vitamin D binding protein using assay employing lipid-coated polystyrene beads. Anal. Biochem. 1991, 199, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.S.; Martin Petkovich, M.; Holden, R.M.; Adams, M.A. Megalin and vitamin D metabolism - implications in non-renal tissues and kidney disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, R.; Christensen, E.I.; Birn, H. Megalin and cubilin in proximal tubule protein reabsorption: from experimental models to human disease. Kidney Int. 2016, 89, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybchyn, M.S.; Abboud, M.; Puglisi, D.A.; Gordon-Thomson, C.; Brennan-Speranza, T.C.; Mason, R.S.; Fraser, D.R. Skeletal muscle and the maintenance of vitamin D status. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.G.; Fraser, D.R.; Lawson, D.E. Vitamin D plasma binding protein. Turnover and fate in the rabbit. J. Clin. Invest. 1981, 67, 1550–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternes, S.B.; Rowling, M.J. Vitamin D transport proteins megalin and disabled-2 are expressed in prostate and colon epithelial cells and are induced and activated by all-trans-retinoic acid. Nutr. Cancer 2013, 65, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steegenga, W.T.; de Wit, N.J.; Boekschoten, M.V.; Ijssennagger, N.; Lute, C.; Keshtkar, S.; Bromhaar, M.M.; Kampman, E.; de Groot, L.C.; Muller, M. Structural, functional and molecular analysis of the effects of aging in the small intestine and colon of C57BL/6J mice. BMC Med. Genom. 2012, 28, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.G.; Matsuoka, L.Y.; Hollis, B.W.; Hu, Y.Z.; Wortsman, J. Human plasma transport of vitamin D after its endogenous synthesis. J. Clin. Invest. 1993, 91, 2552–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchow, E.G.; Cooke, N.E.; Seeman, J.; Plum, L.A.; DeLuca, H.F. Vitamin D binding protein is required to utilize skin-generated vitamin D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 24527–24532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).