1. Introduction

The loss of cellular redox balance leads to oxidative stress (OS) as a result of an excessive production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) that exceed antioxidant defenses [

1] and cause cellular damage with loss of vital functions.

It is important to note that OS does not always promote damage. Some ROS participate in signaling mechanisms and regulate processes essential for life. A good example is nitric oxide, a free radical and vasodilator, released by endothelial cells; its deficit is associated with cardiovascular and other diseases. OS is involved in a variety of autoimmune diseases of oxidative etiology [

2,

3], particularly rheumatoid arthritis (RA). RA is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease causing progressive disability and premature death [

4]. It is a symmetric peripheral disease involving bone erosion, proximal involvement and destructive bone lesions. In addition to this, RA patients display synovitis, morning stiffness and/or immobility of their proximal interphalangeal joints [

5]. Finally, such patients suffer joint failure due to cartilage damage and severely weakened tendons and ligaments [

6].

In the development of RA, a proinflammatory and hypoxic scenario is generated in the synovial tissue, which leads to an overproduction of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) with DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction. The synovium is the principal target as it is associated with the degree of RA activity. This compartment is severely infiltrated by immune system cells leading to neovascularization [

7]. The joints of patients affected by RA show inflammation, edematous synovial tissue with hyperemia and other alterations [

8].

One important source of ROS in RA is the mitochondria. In particular, the superoxide anion radical is generated in the mitochondrial electron transport chain with the participation of complexes I, II and III [

9]. This ROS is a precursor of other ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide, which triggers a cascade of reactions giving rise to different molecules involved in RA. The accumulation of ROS in the mitochondria leads to the modification of functions such as the activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. An extension of the opening time of these pores can induce an explosive increase of ROS that damage the mitochondria itself which is linked to different pathological conditions expressed in the form of comorbidities of RA [

10,

11]. On the other hand, the joints of patients with RA are in a state of hypoxia, which is linked, as an additional factor, to the production of ROS [

12]. ROS levels have been correlated with the degree of RA activity, C-reactive protein and antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides in the blood of patients with RA, with ROS being reported as an indirect indicator of the degree of synovial inflammation in these patients [

13,

14].

Neutrophils represent 60% of total leukocytes. These cells are part of the innate immunity

, constituting the first lines of defense against infections and orchestrating adaptive immune responses. It has been suggested that neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), activation of peptidyl arginine deiminase (PAD), and generation of citrullinated peptides are at the core of RA pathogenesis. Activated neutrophils accumulate in synovial fluid and tissue. Moreover, fibroblasts such as synoviocytes internalize NET-associated citrullinated peptides, recruit antigen-presenting cells that present this peptide-NET complex to CD4+ T cells to produce an autoimmune response [

16].

Neutrophil levels in RA patients are significantly higher than in subjects with other arthritic diseases. Their concentrations were positively correlated with inflammation and disease severity. ROS are released by neutrophil degranulation, including superoxide anion radical, increased mitochondrial and extracellular oxidative stress with a decrease in antioxidant defense mechanisms in RA [

17,

18].

Macrophages, together with neutrophils, belong to the set of cells that constitute innate immunity. Macrophages release high levels of ROS produced by different sources and sites of formation. The first identified source of superoxide anion radical generation by macrophages was NADPH Oxidase located in the plasma membrane, which produces the superoxide radical by transfer of an electron from NADPH to oxygen. It is worth noting that, in the macrophage

, we find other sites of ROS production – of mitochondrial origin – such as the formation of hydrogen peroxide by monoamine oxidase (MAO) in the outer membrane of the mitochondria; a superoxide anion radical, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical in the mitochondrial matrix, through the electron transport chain. In addition to this we also find hydrogen peroxide with a participation of cytochrome C in the inner membrane of the mitochondria, plus superoxide anion radical and hydrogen peroxide in the cytosol due to the metabolism of xanthine via xanthine oxidase [

19]. From the above

, it is evident that the superoxide anion radical is released by macrophages from different sites and by different enzymes and can play a central role in the triggering of RA.

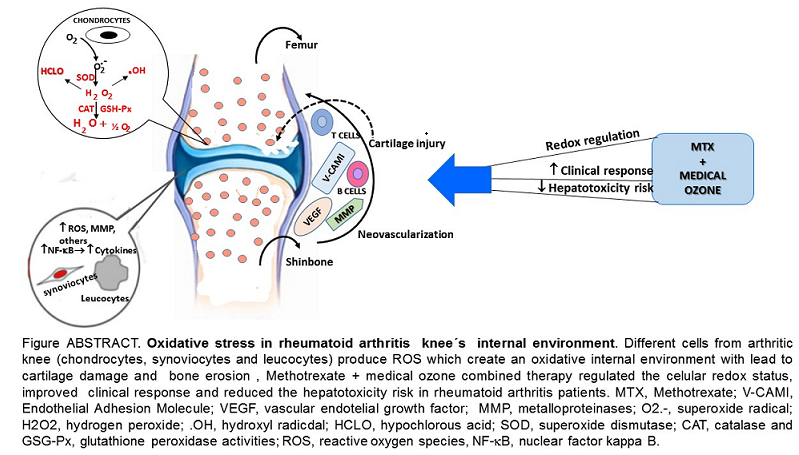

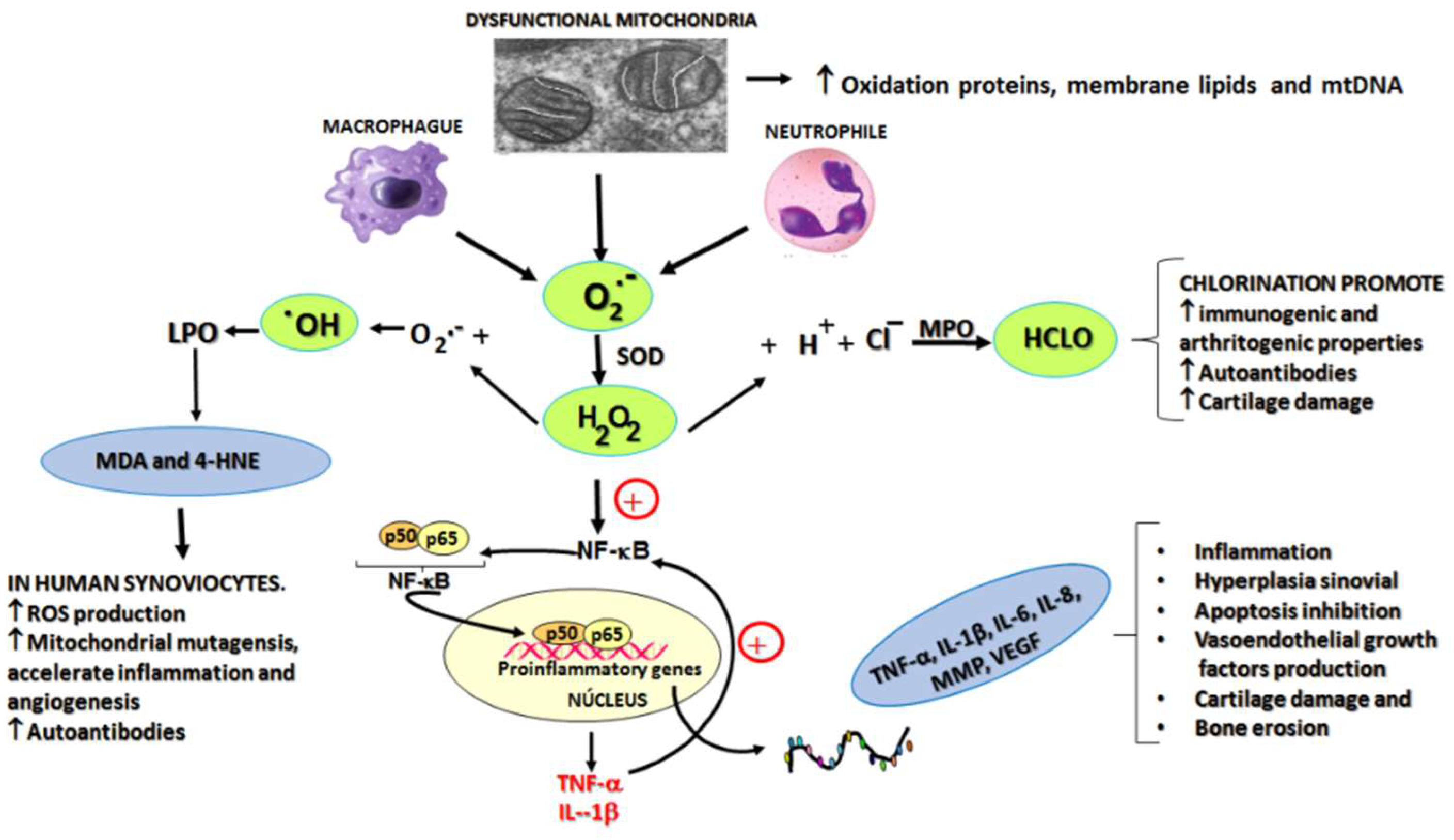

Figure 1 shows the main ROS involved in different events associated with the development and progression of RA (superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical and hypochlorous acid) [

7].

The aim of this review has been to perform a holistic analysis of a selection of redox results from different studies on medical ozone in disease and clinical models. In this review, the interrelation between animal studies and clinical response in patients with RA is discussed. An integrative analysis has led to the proposal of a new mechanism of action. We conclude that the improvement observed in the clinical response of patients with RA treated with the combined therapy methotrexate + medical ozone, compared to monotherapy, is the result of a common mechanism of action, shared by methotrexate and medical ozone, with the participation of adenosinergic transmission.

2. Medical Ozone, a Regulator of Redox Targets with an Impact on RA

2.1. Studies in Animal Models

Medical ozone is made up of an ozone/oxygen mixture (O

3/O

2) obtained by electrosynthesis by passing a current of pure O

2 through a silent electrical discharge generated by specific equipment designed for such purposes, obtaining an ozone concentration between 0.05 and 5 volume percent [

20].

Studies carried out in different disease models using experimental animals, have shown that medical ozone “per se” is capable of regulating the cellular redox state by acting on different processes involved in RA: this is referred to in

Figure 1.

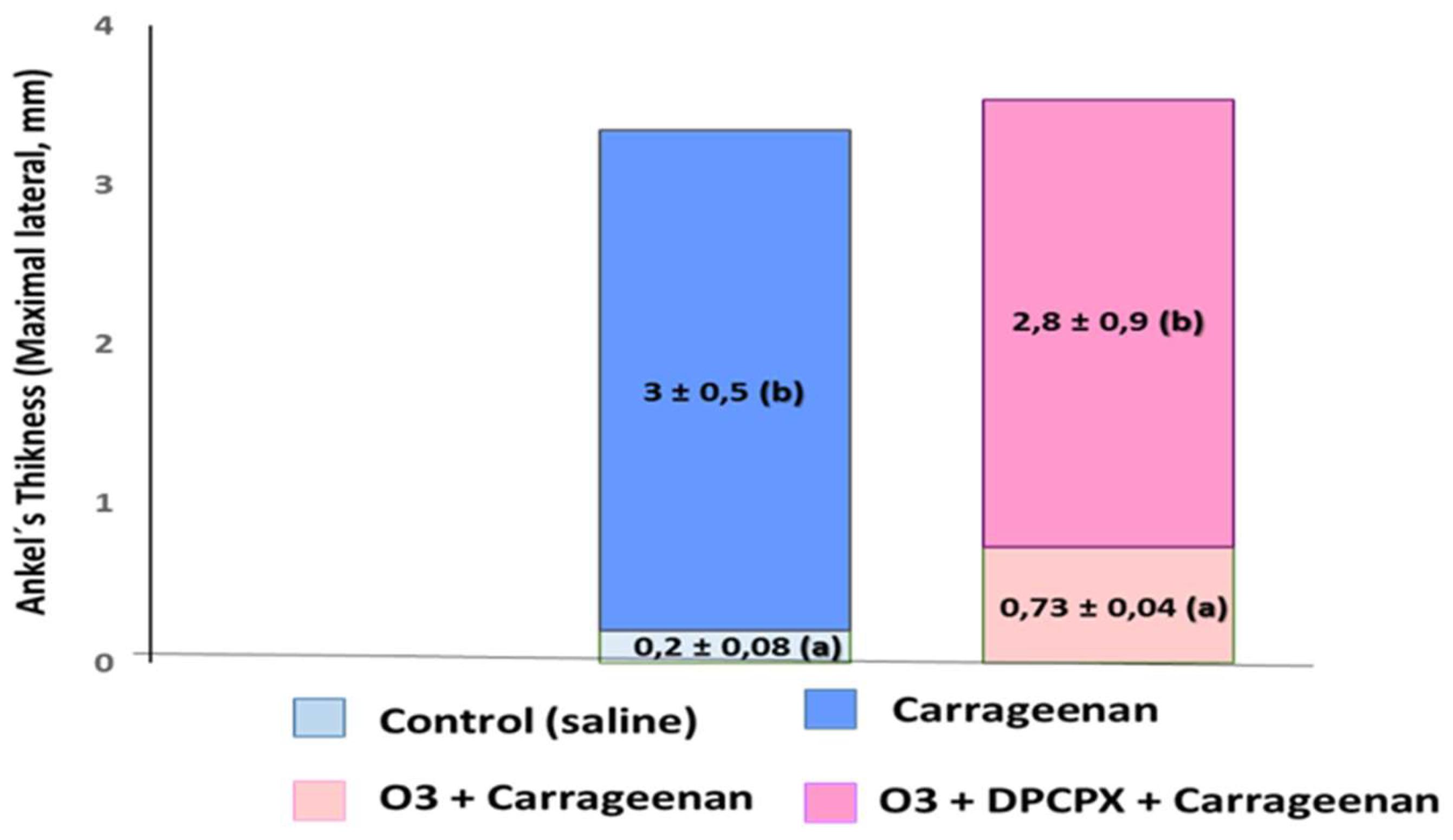

In acute (carrageenan-induced synovitis) and chronic models through administration of a fraction of the streptococcal wall, glycan/polysaccharide peptide (PG/PS), the beneficial effects of medical ozone were demonstrated by the reduction of inflammation and pain in the acute model (

Figure 2). Likewise, in the chronic model, the levels of mRNA transcripts for TNF-α and Il-1β were reduced in the group treated with ozone when compared to those in the control group, which had been treated with the inducer PG/PS and the PG/PG + oxygen group (ozone vehicle) [

21].

It is evident how medical ozone, administered by rectal insufflation, prevented carrageenan-mediated inflammation (0.73 ± 0.04 vs. 3 ± 0.5 mm, respectively) without differing significantly from the control (saline) (0.2 ± 0.08). The participation of adenosine A1 receptors in the anti-inflammatory actions of ozone was demonstrated when DPCPX (8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine), a specific antagonist of these receptors, blocked the protective effects of medical ozone by reestablishing the inflammatory process (3 ± 0.5 vs 2.8 ± 0.9 mm).

The participation of adenosine has an important significance in the therapeutic actions of methotrexate (MTX) in the treatment of patients with RA. Adenosine is considered to be one of the probable mechanisms of action of MTX, due to its capacity to inhibit the release of proinflammatory cytokines [

23]. The beneficial effects of ozone, mediated by A

1 adenosine receptors, have been demonstrated in different disease models: one example is the ischemia/reperfusion injury of the liver [

24]. In this model, medical ozone was shown to promote adenosine accumulation by regulating the activity of adenosine deaminase, the enzyme responsible for its degradation to inosine [

25],

In another experiment ozone reduced the time up to the first seizure in a pentylenetetrazol-induced seizures [

26], as well as in carrageenan-induced synovitis [

22].

The expression of A

1 receptors is redox-dependent. In one report, ROS induced an increase in the expression of adenosine A

1 receptors; this was supported by the finding that incubation of cells with H

2O

2 and catalase, a hydrogen peroxide scavenger, attenuated the expression of adenosine A

1 receptors [

27].

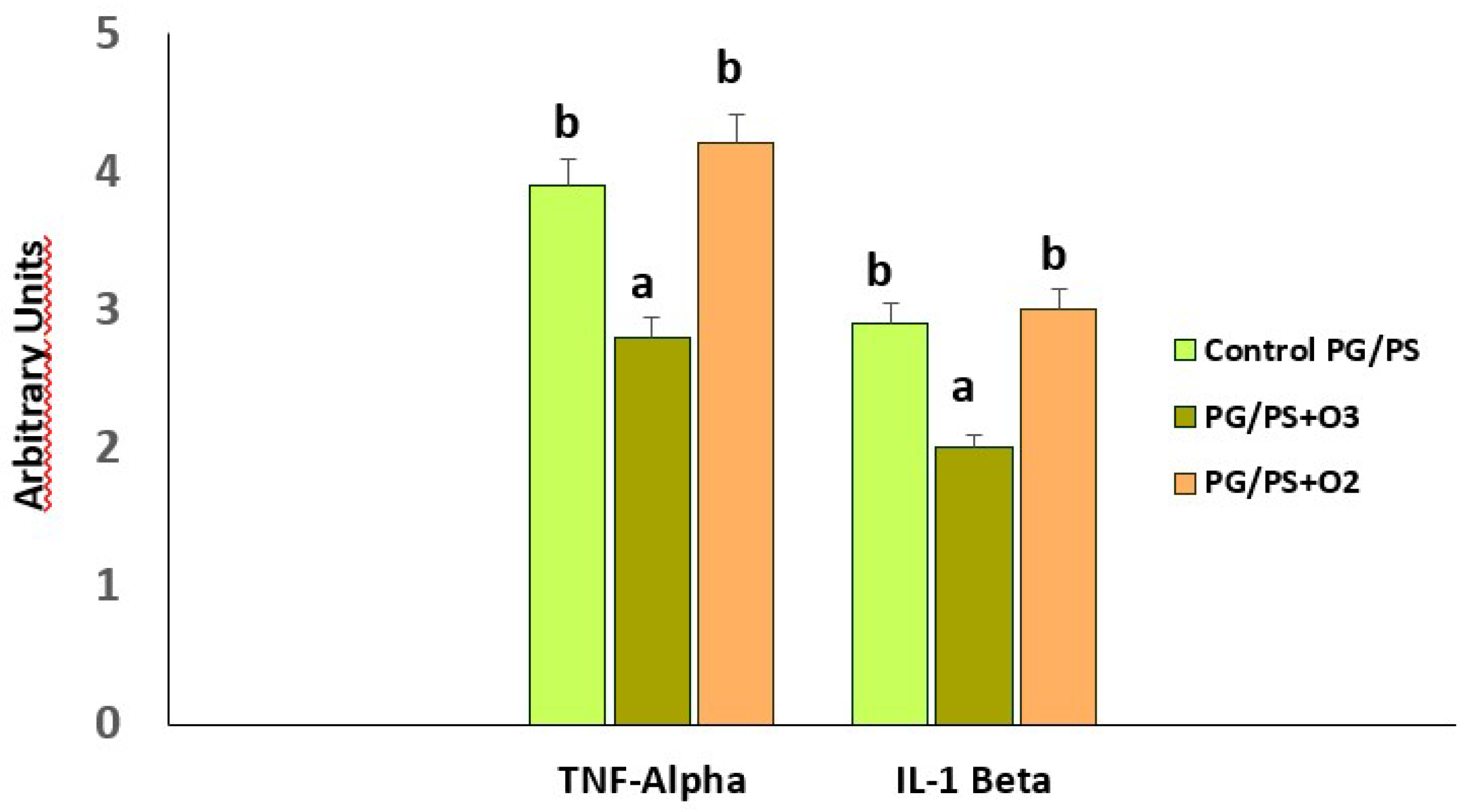

Figure 3 shows the mRNA levels for the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, which, together with IL-6, are characteristic of the cytokine storm in RA [

21].

Preconditioning with medical ozone significantly reduced the concentrations of both cytokines that are generated as a result of an activation of the nuclear transcription factor NF-kB.

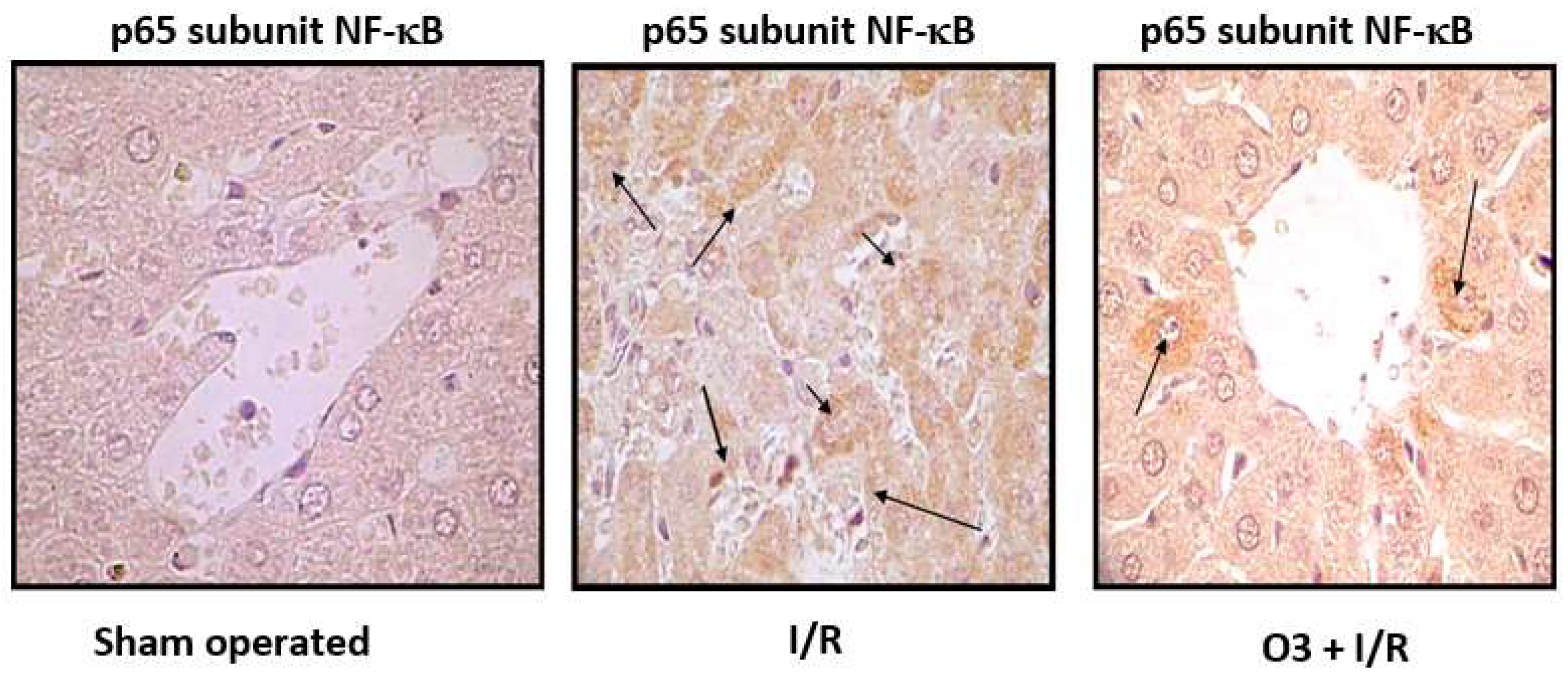

Figure 4 shows the results of immunohistochemistry of the p65 subunit of NF-κB in ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) of the liver.

The p65 subunit of NF-κB is the one that recognizes response elements in DNA and promotes the transcription of proinflammatory cytokines (

Figure 1). In

Figure 4 intense p65 immunoreactivity was observed in the I/R group, while the ozone-treated animals showed only scattered zones of reaction. The results suggest that ozone regulates the expression of this factor – among other mechanisms, by its actions on the control of hydrogen peroxide generation (

Figure 1), one of the activators of this factor.

It can be seen how, in the acute synovitis model, ozone restored the concentrations of hydroperoxides to control levels as well as MDA, the terminal product of lipid peroxidation, which is generated by the formation of hydroxyl radicals through the peroxidation of membrane lipids (

Figure 1). MDA has been recognized as a biogenic aldehyde forming adducts with proteins and contributing to the loss of immune tolerance, among other effects [

28,

29].

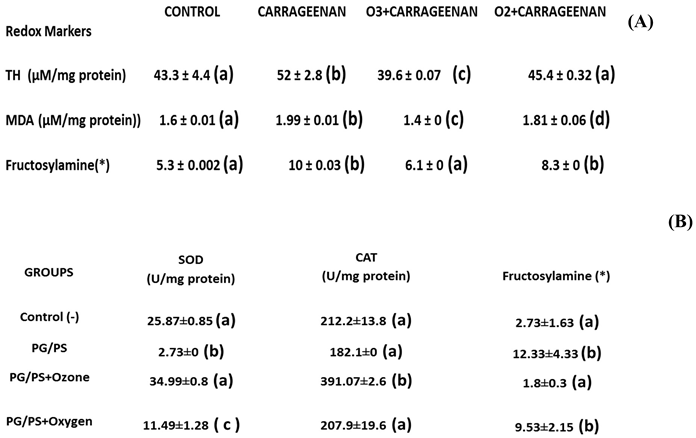

In the chronic model, an increase in SOD was observed, capturing superoxide radicals and generating hydrogen peroxide. This is reduced to water and oxygen by an increase in catalase activity, which increased in all treatment groups.

Legend: TH, total hydroperoxides; MDA (malondialdehyde); O3 (ozone); O2 (oxygen) (*) (relative content/mg protein x 10; SOD (superoxide dismutase) activity; CAT (catalase) activity; PG/PS (peptidoglyan/polysaccharide). The mean ± SD is here given. Different letters indicate significant differences (p <0.05) [21, 22].

Hypochlorous acid (HCLO) is another ROS involved in RA (

Figure 1). It originates from hydrogen peroxide in the presence of a halogen (mainly chlorine). The enzyme Mieloperoxidase (MPO), abundant in neutrophils and macrophages, catalyzes the reaction.

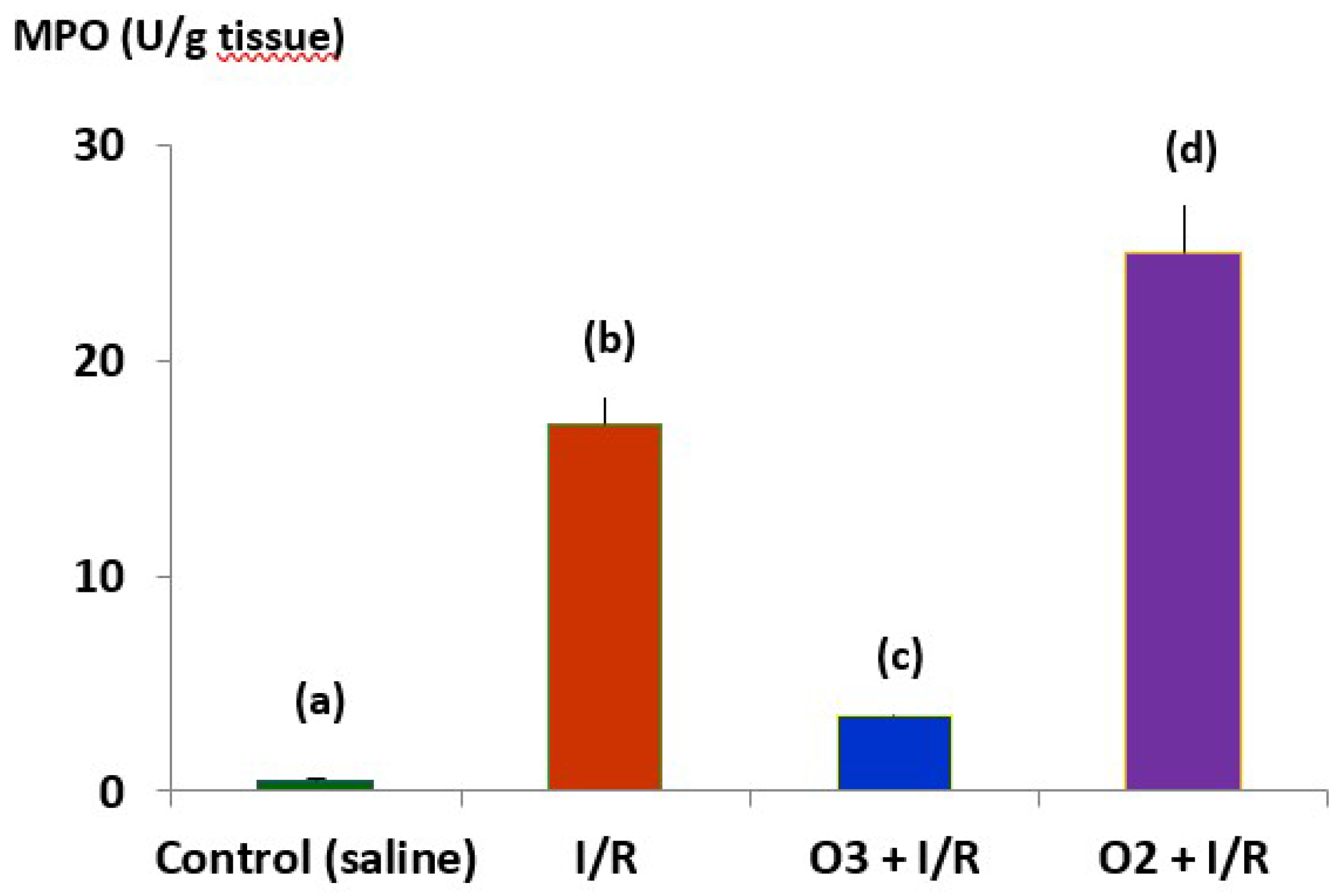

Figure 5 shows the effects of medical ozone on MPO activity in an ischemia/reperfusion model.

The results show that ozone regulated the activity of the enzyme that catalyzes the formation of HCLO, which was significantly lower in the group treated with ozone compared to the group subjected to I/R and O2 + I/R damage. Of note are the results in the group that received oxygen (ozone vehicle) where the damage was greater than that of I/R. The results obtained, at an experimental level, demonstrate that medical ozone is able to act on the different ROS involved in RA and that medical ozone per se exerts beneficial effects in the experimental models of arthritis studied.

2.2. Studies in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

The treatment options available for RA, where methotrexate (MTX) remains the gold standard for this disease plus the so-called biologicals that can reduce pain and stiffness, exhibit a limited effectiveness accompanied by multiple adverse effects such as nausea, hepatotoxicity, hemato/metabolic disorders and interstitial lung diseases. Biological agents (e.g. anti-TNF-α antibodies) are effective, but have adverse effects such as infections in the infusion process and at the injection site, as well as differences in efficacy. With the advent of these new therapies, the treatment of patients with RA has improved. However, due to the heterogeneity and complexity of the pathological mechanisms in RA, some patients still have a poor clinical response, which means that the development of new therapies is still a priority [

30].

Through an oxidative pre/postconditioning mechanism validated in different disease models and in clinical studies [

31], medical ozone has demonstrated its efficacy in diseases of oxidative etiology. Since RA is an autoimmune disease associated with severe and chronic oxidative stress, it is expected that medical ozone will have beneficial effects in the treatment of RA.

The results in patients with RA treated using the combined therapy MTX + medical ozone were in line with experimental studies. A decrease in swollen and painful joints was observed, as well as an improvement in the performance of daily activities; this included a reduction in the levels of antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides and an increase in antioxidant defenses accompanied by a decrease in redox markers which indicate damage.

Table 2 shows the results obtained after 21 days of treatment for patients treated with MTX and for those who received MTX + medical ozone [

32].

No significant differences (p >0.05) between either group were observed for the variables DAS28 and HAQ-DI at the beginning of the study. The DAS28 decreased significantly (p <0.05) in the MTX + Ozone group, whereas there were no changes in the MTX group. At the end of the clinical study, differences (p <0.05) were observed between both groups. HAQ-DI showed results similar to DAS28. and MTX + medical ozone improved the patients' disabilities, whereas the MTX group ended without changes. Again, significant differences (p<0.05) were found between both groups at the end of the study showing beneficial results for the group of patients receiving the combined therapy. Both acute phase reactants (CRP and ESR) decreased (p <0.05) in the MTX + medical ozone group, whereas the MTX group showed no significant changes (p >0.05) at the end of the study.

The MTX + medical ozone group reduced (p<0.05) autoantibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides, which were not modified (p > 0.05) in the group not treated with ozone. Similarly, autoantibody levels in the MTX + ozone group were lower than in the MTX group at the end of the study. These results indicate that medical ozone can achieve a reduction in the autoimmune response and are in line with clinical markers (DAS28, HAQ-DI and acute phase reactants).

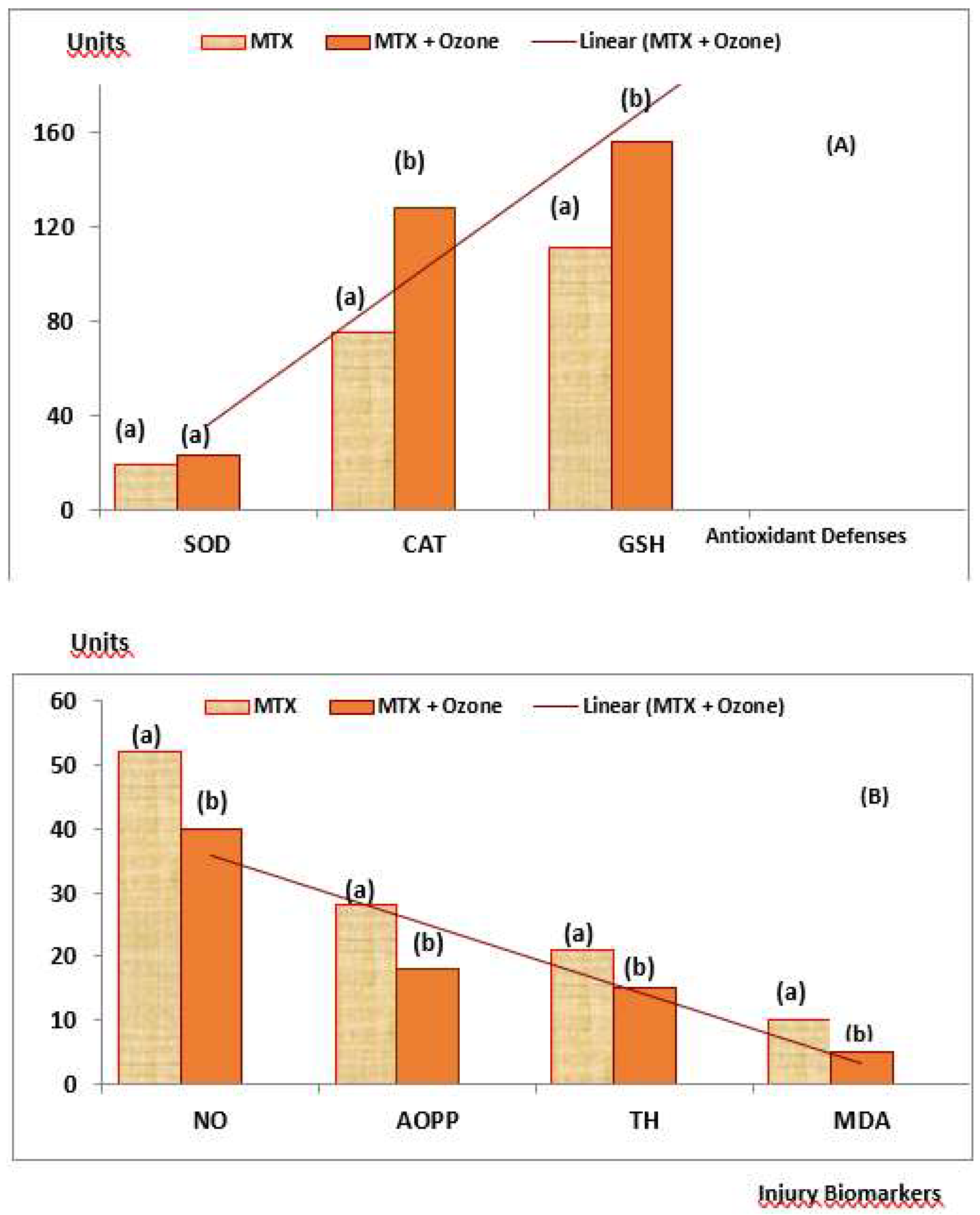

2.2.1. Levels of Redox Biomarkers in the Groups at the End of the Study

Plasma biomarkers of protection (Antioxidant Defenses) and damage (Injury Biomarkers) were studied in both groups of patients (

Figure 6). MTX + ozone increased the capacity of the endogenous antioxidant system to counteract oxidative damage, resulting in a significant decrease (p<0.05) in damage to biomolecules (lipids, MDA and proteins, AOPP), as well as in TH levels and nitric oxide concentrations. By contrast, patients who did not receive ozone showed a reduction in their antioxidant defenses and a higher level of damage (

Figure 6A and

Figure 6B). To find out whether there was any relationship between redox markers and clinical variables, the correlations between these variables were evaluated where only correlations could be found after treatment with MTX + medical ozone; this suggests a stabilization of the antioxidant/prooxidant balance in the patients. GSH was the only protective redox marker that correlated (p<0.05) with all clinical variables (GSH vs CRP = 0.68, VCG = 0.63, DAS28 = 0.57 and HAQ-DI = 0.72) whereas SOD correlated with acute phase reactants and the Disability Index suggesting its participation in the inflammatory process (SOD vs CRP = 0.5, VCG = 0.51 and HAQ-DI = 0.61).

In addition to the clinical efficacy observed for the combined therapy MTX + medical ozone, the hepatoprotective effects of ozone are added in a model for hepatotoxicity induced by carbon tetrachloride, increasing antioxidant defenses (SOD, CAT, GSH), reducing injury markers (lipid peroxidation), thus preserving the concentrations of calcium-dependent ATPase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, hepatic glycogen and phospholipase A.

Likewise, the levels of transaminases and cholinesterase were reestablished with less general liver damage and a decrease in the area damaged by lipidosis [

33,

34].

The clinical study in patients with RA showed that treatment with the combined therapy MTX + ozone reduced the risk of hepatotoxicity 4 times compared to monotherapy [

35].

3. Discussion

The results of the experimental models developed showed that medical ozone “per se” exhibited beneficial effects in diseases involving cartilage and bone remodeling.

Synovitis is a critical pathological event preceding the clinical onset of RA [

36]. The anti-inflammatory effects of ozone were mediated by the activity of adenosine A1 receptors, a reduction in oxidative damage to proteins (AOPP and Fructosylamine) and lipid peroxidation (MDA). A decrease in the inflammatory process is probably the most important goal in the therapy of synovitis. mRNA and proteins for A

1, A

2a, A

2b and A

3 adenosine receptors are expressed in human synoviocytes. The results show that the adenosine A1 receptor is involved in the anti-inflammatory effects of medical ozone in carrageenan-induced synovitis in Wistar rats (

Figure 2). These results agree with the disappearance of the anti-inflammatory effects and the protection provided by ozone against oxidative damage when the specific antagonist of adenosine A1 receptors (DPCPX) was tested – as demonstrated by ankle inflammation, damage to proteins and lipids, as well as a notable reduction in plasma antioxidant capacity (FRAP) [

22].

Previous results had shown that adenosine receptor A1 was associated with the protective effects of ozone. In damage by ischemia / reperfusion of the liver, activation of A1 receptors with CCPA (2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosin), a specific agonist of the A1 receptors, corresponded to the reduction of transaminases, whereas blocking these receptors by DPCPX increased liver damage [

24]. In another study, ozone increased the latency of the first convulsive crisis and restored cell redox balance in pentylenetetrazol seizures (PTZ) in mice. DPCPX completely abolished the protection provided by ozone, evidenced the role of adenosine receptors A

1 against brain damage [

26]. The anti-inflammatory effects of ozone, mediated by adenosine A

1 receptors, can be the consequence of a transferable oxidative stress induced by ozone. This stress, when it was induced by certain specific antineoplastic agents and H

2O

2, regulated the expression of A1 adenosine receptors in the smooth muscle cells of hamsters. [

37]. By promoting a generation of ROS, light and transient, ozone regulates cell redox balance and can represent a stimulus for the expression of A

1 adenosine receptors. Advance Oxidation Protein Products are markers of oxidative damage to proteins and the increase in their levels in patients with AR have been observed. In addition, synoviocytes such as fibroblasts (FLSS) are related to oxidative stress. An exposure of FLSS to AOPP regulated the mRNAs and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, metalloproteinases of the matrix and the growth factor of the vascular endothelium in a manner dependent on the concentration. The degradation of IκB and the nuclear translocation of NF-κB-P65, induced by AOPP were blocked significantly by antioxidant activity, such as superoxide dismutase, N-acetyl-L-cysteine and NADPH oxidase inhibitors. [

38]. Medical ozone was able to maintain the concentrations of AOPP at the control group.

Lipid peroxidation leading to the formation of protein adducts promotes proinflammatory responses characterizing a variety of chronic conditions [

39]. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is one of those ubiquitous products involved in disease pathogenesis, and its levels are increased in synovial fluid. MDA was significantly reduced by ozone treatment, with respect to all experimental groups studied, suggesting the decrease of hydroxyl radicals available to initiate and trigger peroxidative damage of cell membranes, and also suggesting a decrease in RA-associated events mediated by this aldehyde (

Figure 1).

Medical ozone exerted beneficial effects on local inflammation, induced by carrageenan, and these results were corroborated in the systemic and chronic model of arthritis.

TNF-α is a proinflammatory cytokine, activating the NF-κB pathway, leading to a cascade of other proinflammatory cytokines [

40]. Furthermore, it is known to increase the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Current biological therapies, including anti-TNF-α inhibitors, result in disease improvement and prevent joint erosion, in spite of the fact that clinical studies on the efficacy of TNF-α blocking agents clearly show that about 40% of patients receiving this therapy are non-responders [

41]. When TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA levels were determined in spleen homogenates, it was observed that ozone treatment decreased (p<0.05) the concentration of these transcripts compared to the PG/PS and PG/PS + oxygen groups (

Figure 3). Both cytokines are generated when NF-κB is activated, but at the same time, TNF-α is an activator of NF-κB which gives rise to a vicious circle perpetuating the chronic inflammatory process. For this reason, such results indicate that medical ozone treatment contributes to a decrease in the pathological cascade of NF-κB. The protective effects of ozone may be a consequence of its ability to regulate the activity of the p65 subunit of NF-κB, which was demonstrated by ischemic/reperfusion damage to the liver (

Figure 4). The efficacy of ozone in RA can not only be explained by its acting on the generation of proinflammatory cytokines alone, since the disruption of the cellular redox balance is closely related to cartilage damage, bone remodeling and the autoimmune response itself. Ozone therapy was able to regulate cellular redox balance (

Figure 5). It is known that ROS can function as a second messenger to activate NF-κB, which orchestrates the expression of a spectrum of genes involved in the inflammatory response. Overproduction of NO contributes to the pathogenesis of chronic arthritis. In humans, circulating levels of nitrate/nitrite are present in arthritic patients and synovial tissues of RA patients express and produce abnormally high amounts of NO [

42].

Simultaneously with NO, other redox markers were also studied (

Table 1). PG/PS and PG/PS + oxygen exhibited a low SOD activity whereas PG/PS + Ozone and control (-) showed no significant differences. An increase in NO and a decrease in SOD represent, pathologically, an "explosive mixture." The accumulation of superoxide radicals in the presence of overproduced NO leads to the formation of peroxynitrite, a known cytotoxin. Modest increases in superoxide and NO (10-fold in each case) will increase peroxynitrite formation 100-fold. Under proinflammatory conditions, such as in RA, a simultaneous production of superoxide and NO (1000-fold) will increase peroxynitrite formation 1,000,000-fold [

43]. Increased SOD promotes the formation of hydrogen peroxide which may produce additional damage to biomolecules. However, hydrogen peroxide is reduced if catalase activity is increased. PG/PS + Ozone showed an increase compared to all other experimental groups (Control, PG/PS and PG/PS + Oxygen) (

Table 1). Although the control (-) value needed no increased in CAT, the PG/PS and PG/PS + oxygen values did indicate a severe oxidative stress and a low catalase activity: these, by consequence, are by themselves a sure sign of damage.

Medical ozone increased the therapeutic efficacy of MTX in patients with RA. An improvement in the clinical status (reduction in pain, DAS

28, HAQ-DI and acute phase reactants) was observed, as well as a reduction in autoantibodies (anti-CCP) and oxidative stress [

32].

It should be noted that MTX halted the progression of the disease: this represents an important therapeutic response. However, there were no significant differences in the group of patients receiving MTX only, when comparing the beginning and the end of the study. By contrast, patients treated with the MTX + ozone combined therapy significantly improved (p<0.05) in the context of both clinical variables and cellular redox status, suggesting that – in the context of monotherapy (MTX) – the combination MTX + ozone enhances clinical response and exerts an additive or synergistic effect on the response of patients with RA as included in this study. These effects suggest that they are the result of the contribution made by each of the components of the combined therapy (MTX and ozone) in the control of the disease, given that both agents share common therapeutic targets, such as redox balance and actions associated with adenosine. The integration of the results obtained in the different studies carried out with medical ozone in RA (experimental and clinical) allow us to propose a new mechanism of action explaining both the results obtained in disease models and the clinical response of patients (

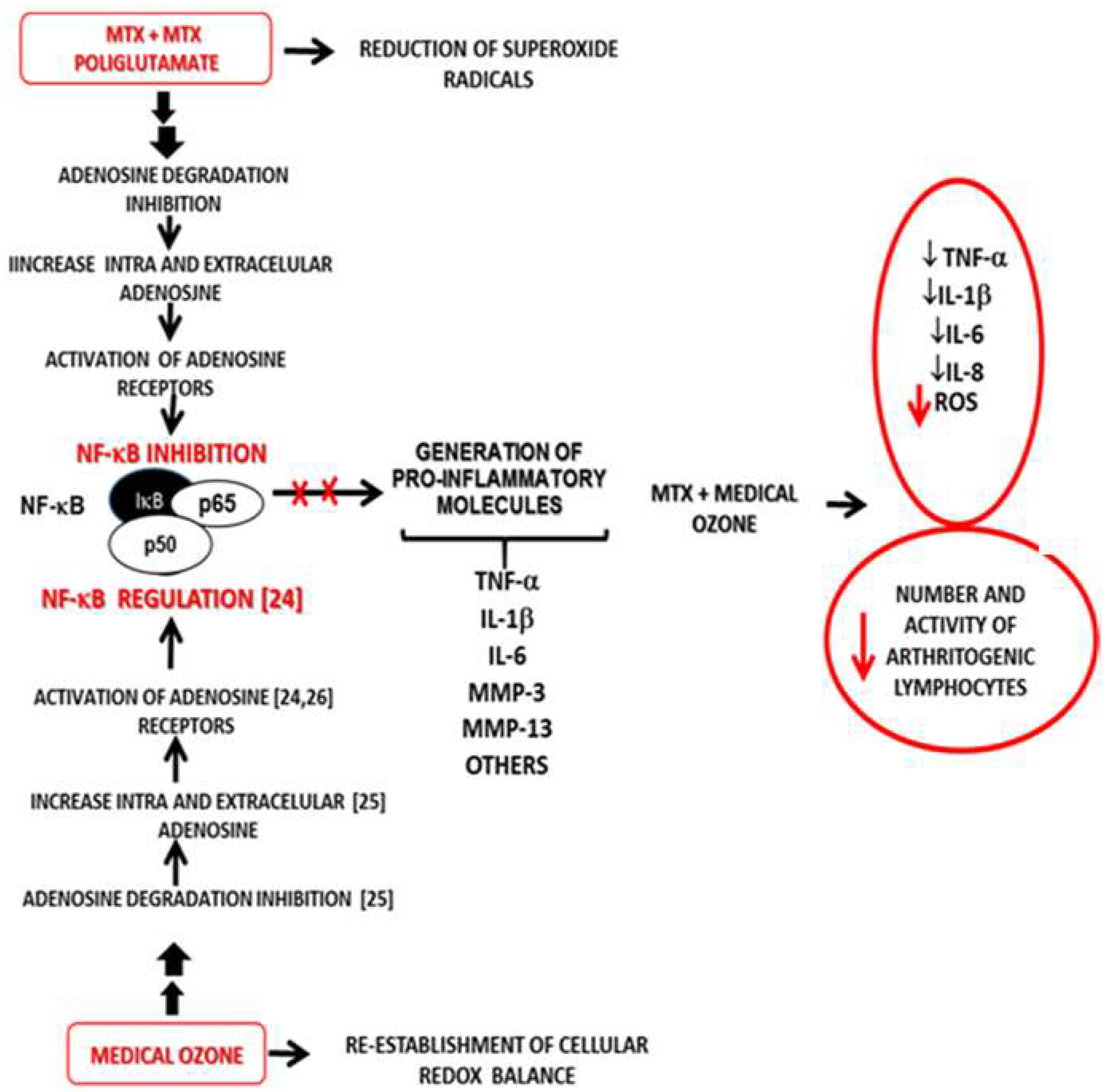

Figure 7).

The proposed mechanism is based on adenosinergic participation, common to MTX and medical ozone, as essential mechanisms in the treatment of RA capable of regulating the redox state, the production of proinflammatory cytokines and arthritogenic lymphocytes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.S.L.F., G.T.O., R.V.-H., G.L.C. and I.S.E.; Methodology, O.S.L.F. and G.T.O.; Software, G.T.O.; Validation, M.E.C.V.; Investigation, O.S.L.F., G.T.O., G.L.C., I.S.E. and M.E.C.V.; Resources, R.V.-H., G.L.C. and I.S.E.; Data curation, G.T.O. and R.V.-H.; Writing—original draft, O.S.L.F.; Writing—review & editing, O.S.L.F., G.T.O., R.V.-H., G.L.C., I.S.E. and M.E.C.V.; Supervision, G.L.C. and M.E.C.V.; Project administration, I.S.E. and M.E.C.V.; Funding acquisition, O.S.L.F. and R.V.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.