1. Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF, OMIM #219700) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder. To date, 105,000 people live with CF in the world. Its incidence varies from 1/900 to 1/25,000 in different populations. In Mexico its incidence is estimated at 1/ 8500 live births annually [

1,

2,

3]. This disease arises from the presence of two pathogenic variants (PVs)

in trans in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR, OMIM #602421) gene, which is located on chromosome 7q31. The CFTR gene contains 27 exons encoding a glycoprotein (CFTR) of 1480 amino acids, composed of two transmembrane domains (TMD1 and TMD2), two cytosolic nucleotide-binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2), and a phosphorylation-dependent regulatory domain (R) [

3]. CFTR dysfunction results in disrupted epithelial homeostasis of water, chloride, sodium, and bicarbonate across various organs and systems [

4], as a result of this, patients with CF present a variable clinical spectrum, in which lung damage is the main cause of morbidity and mortality, due to the accumulation of abnormally thick and sticky mucus, leading to recurrent infections from

Sthapylococcus aureus and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria. Additionally, CF patients can present pancreatic insufficiency (PI), malnutrition, meconium ileus (10-20%), and male infertility due to congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens (CBAVD) [

5]. The life expectancy of CF patients in developed countries is 50 years, while in Mexico it is 21.37 years [

6].

Traditionally, the diagnosis of CF is carried out by the family’s clinical history, and with the classic characteristics of the disease such as the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IP, elevated sweat chloride≥60 mmol/L and molecular confirmation with the presence of 2 PVs in the

CFTR gene [

7]. In this sense, more than 2000 variants distributed throughout the

CFTR gene have been reported, out of which, 1085 are PV or disease-causing, and 55 variants with variable clinical consequences (

http://www.cftr2.org, 5 September 2024). The most common PV is p.(Phe508del) (c.1521_1523del, rs121909001), which is a deletion of the amino acid phenylalanine at position 508 of the protein. Its frequency is variable since it is present in the 100% of CF patients of the Faroe Islands of Denmark; however in other Latin American populations, this frequency is lower, ranging from 25 to 60%. The particular genetic admixture of Latino populations has given rise to a wide spectrum of PVs, some of which are exclusive to some countries or even to some families, and Mexico is no exception with the report, to date, of 95 PV in patients with CF [

2,

6].

Usually, molecular diagnosis of CF has focused on identifying directly the 2 PVs each inherited from each parent. However, with advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS) providing complete

CFTR sequences, it is now possible to analyze additional variants in the gene, such as variants in the same allele (

in cis) that can form complex alleles [

8]. The study of these complex alleles will allow a deeper understanding of the disease and its broad spectrum of clinical manifestations.

Previous reports have shown that the combination of multiple variants, such as complex alleles, could worsen or mitigate the patient’s clinical condition and potentially influence the structure and function of the CFTR protein, leading to differential responses to CFTR modulator treatment. An example of this was reported in 2020 by Chevalier’s group with the p.[Arg74Trp;Val201Met;Asp1270Asn] complex allele. This allele produces a protein with a partial loss of exon 3 with a reduced function. A single (p.Asp1270Asn) variant, when present with another PV in a compound heterozygous state, is not enough to cause CFTR channel dysfunction. However, individuals with the p.[Arg74Trp;Asp1270Asn] combination in the same allele exhibit a minor functional defect, whereas p.[Arg74Trp;Val201Met;Asp1270Asn] leads to mild CF [

9]. Similarly, the p.Leu997Phe PV could be correlated with CFTR- related disorders (CFTR-RD), but when it is presented as a complex allele with the variant p.(Arg117Leu), this combination could produce a mild CF phenotype [

9].

On another hand, the effect of

in cis variants with p.Phe508del has also been reported. The p.[L467F;F508del] complex allele leads to a dysfunction of the CFTR protein with negative effects on the response to lumacaftor. Moreover, patients carrying the p.Phe508del/p.[Phe508del;Phe87Leu;Ile1027Thr] allele show no response to treatment with ivacaftor + lumacaftor; therefore, the triple combination (ivacaftor/tezacaftor/elexacaftor) is recommended [

10]. Another variant studied was p.Ala238Val, in

cis with p.Phe508del, in which it has been observed that CF patients carrying these alleles present a more severe lung damage and resistance to targeted therapy compared to patients who only carry p.Phe508del [

11].

In this study, we investigated the impact of the p.[Ile148Thr;Ile1023_Val1024del] complex allele, present in nine CF patients due to a potential founder effect. For the first time, we reported two homozygous patients carrying this complex allele, and we modeled the encoded protein to better understand the structural dysfunction that it causes.

2. Materials and Methods

We included nine Mexican patients with positive sweat chloride tests (>60 mmol/L) from six unrelated families. DNA extraction was whole venous blood with the QIAmp DNA Blood Maxi kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Previously, these patients were sequenced using Multiplicon CFTR Master DX (Agilent, CA, USA) on the MiSeq system (Illumina, Inc), which amplified all exons plus 30 bp of their 5ʹ and 3ʹ flanking sequences, and UTRs regions. The analysis of CFTR-sequencing was done using the MASTR Reporter software (Agilent, USA). The variants of the complex allele were confirmed in their families by direct Sanger sequencing using the Big Dye Terminator (Applied Biosystems TM, Foster City, USA). This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethics and Research Committees of the National Institute for Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN CEI 2015/10). Written informed consent and assent were obtained from all participating families.

The clinical characteristics of the patients were collected from the medical history and the CF database of our laboratory. Birthplace of families was established by interrogation, and family trees were constructed using the Progeny free online pedigree program (

https://pedigree.progenygenetics.com).

We used in silico methods to assess the impact of each variant and the complex allele on the CFTR protein. SWISS-MODEL (

https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) and I-TASSER (

https://zhanggroup.org/I-TASSER/) were employed to predict the structural effects of the complex allele on the CFTR protein. SIFT-Indel (

https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/) and Mutation Taster (

https://www.mutationtaster.org/) were used to assess the functional consequences of p.(Ile1023_Val1024del) and p.(Ile148Thr). DynaMut (

https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/dynamut/) allowed us to analyze changes in protein stability and disruptions in interatomic interactions caused by both individual variants and the complex allele. Protein stability was assessed through ΔΔG estimation, which represents the difference in ΔG between the wild-type and mutant proteins. The CFTR models were uploaded into PyMOL (

https://www.pymol.org/), where the align command was used to superimpose the mutant structures onto the wild-type structure (PDB ID: 5UAK). The domains of interest [NBD1, NBD2, R] along with residues 148, 1023, and 1024 of CFTR, were highlighted based on curated domain information from Uniprot and Swiss-Prot.

3. Results

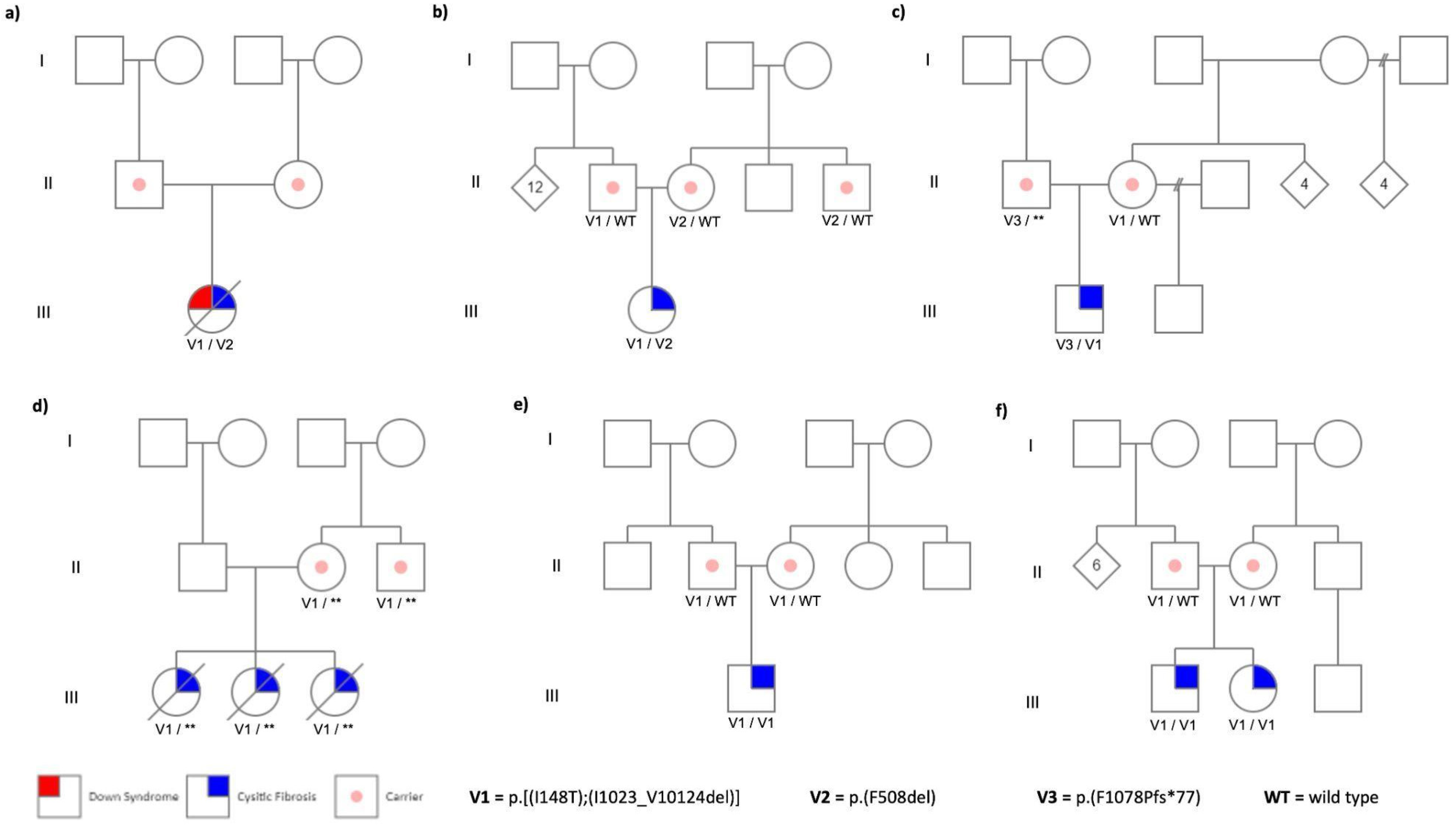

A total of nine CF patients from six unrelated families carrying the complex allele p.[Ile148Thr;Ile1023_Val1024del] were studied. In all families, this complex allele was found

in trans with the Class I and II PVs [c.1521_1523del, [p.(Phe508del) and c.3231_3232del, p.(Phe1078Profs*77)] (

Figure 1a–c). In one family, the second PV could not be identified, possibly due to a deep intronic variant (

Figure 1d). Families 5 and 6, declared as nonconsanguineous, carried the complex allele in a homozygous state (

Figure 1e,f).

All patients presented severe clinical symptoms, characterized by pancreatic insufficiency (PI) and elevated sweat chloride levels (≥85 mEq/L) with diagnosis at birth or less than 4 years of age. Clinical history revealed that all patients’ ancestors were born in Mexico and Guanajuato States (Central Mexico) (

Figure 2).

To further investigate the frequency of variants forming the complex allele, we performed a targeted search in our laboratory dataset containing exome sequences from 2217 individuals. This revealed eight individuals (0.18%) carrying the p.(Ile148Thr) variant, but only one (0.022%), who was also born in Central Mexico (San Luis Potosi state), carrying the complex allele (

Figure 2).

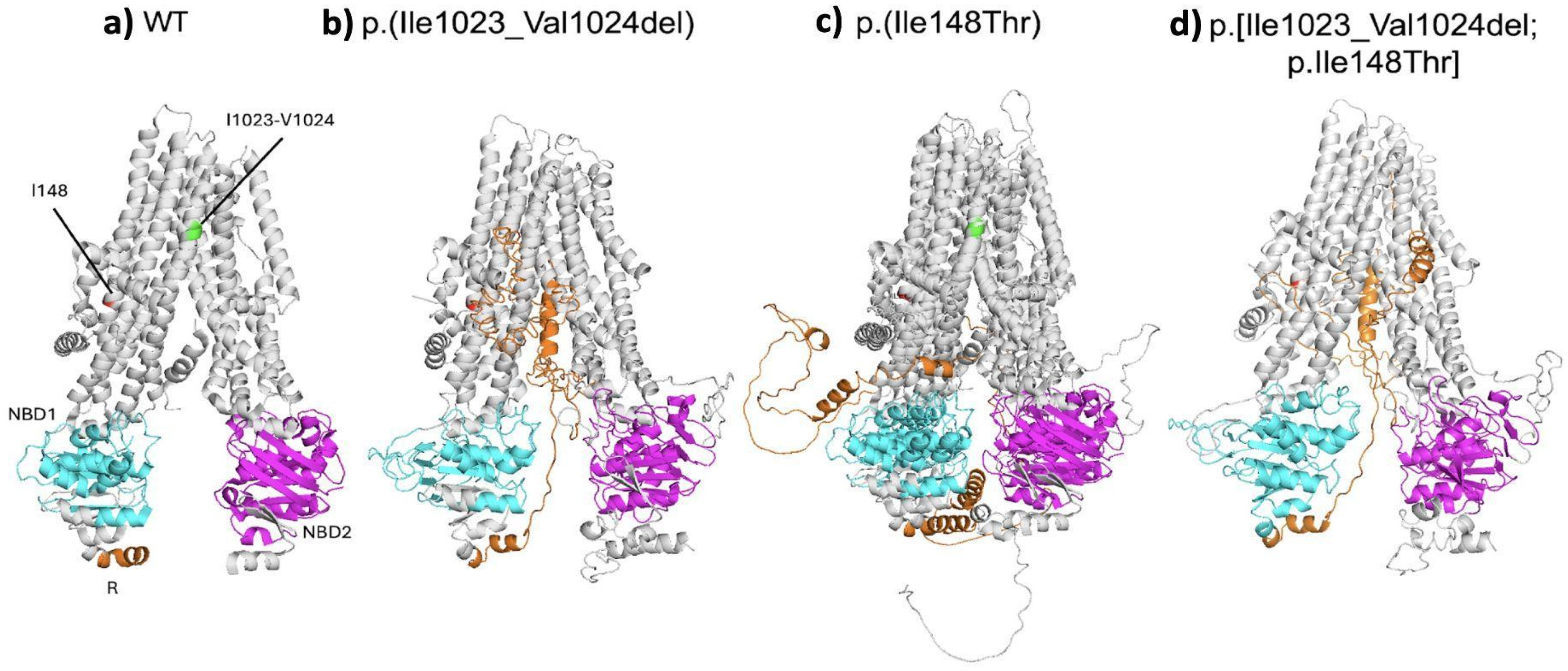

To better our understanding of the structural impact of each variant and the complex allele on the CFTR protein, we performed an in silico analysis (

Figure 3a–d). The SIFT-INDEL tool predicted a confidence score of 0.858 for the p.(Ile1023_Val1024del) variant, indicating a damaging effect. Additionally, MutationTaster classified this variant as disease-causing with a 71% probability. Furthermore, protein modeling revealed that this variant disrupts the secondary structure of CFTR. Specifically, it affects helix 10 of TMD2, which is crucial for its stabilization, configuration, opening and closing of the channel pore. This deletion also disrupts the helical structure of the helix 10, potentially destabilizing the entire transmembrane domain. The structural analysis also predicted a misconfiguration of the protein in the R, NBD1 and NBD2 domains (

Figure 3b).

Modeling of the p.(Ile148Thr) variant displayed a destabilized protein, with a predicted stability change (ΔΔG Stability wt to mut=−2.05 kcal/mol). MutationTaster also classified it as disease-causing (probability: 99.9%). Protein modeling of this variant revealed a significant structural disruption in CFTR (

Figure 3c). The Ile148 is located at the junction between the second and third helixes of TMD1 near the interface between the membrane and the cytoplasm. The substitution of this isoleucine with threonine (148Thr) alters the interaction of helixes 1 and 2, and the cytoplasmic loops 1 and 2 in TMD1 in the protein. Additionally, the change to 148Thr induces changes of the cytoplasmic side of the protein compatible with a narrowing of the cytoplasmic side of changes pore (

Figure 3c).

Finally, when both variants were modeled together, as a complex allele, the resulting protein conformation exhibited more pronounced changes, including a narrowing cytoplasmic face of the channel pore, rearrangement of the NBD1, NBD2 and R domains, as well as the loss of part of the helix 10. In consequence, the combination of p.(Ile148Thr) and p.(Ile1023_Val1024del) variants might alter the ion flow (

Figure 3d).

4. Discussion

Traditionally, CF diagnosis has relied on identifying two PVs

in trans, one inherited from each parent. Advances in sequencing technologies have enabled the detection of rare CFTR variants, including complex alleles. First described in 1991, complex CFTR alleles are characterized by the presence of two or more variants

in cis, creating a significant challenge for CF diagnosis [

4,

8]. Such alleles may have significant implications for CFTR function and the clinical manifestation of the disease [

14].

Previously, we screened 297 CF patients across Mexico [

6]. Notably, the complex allele p.[Ile148Thr;Ile1023_Val1024del] was identified in nine patients from six different families, all of them born in the Central region of Mexico. Here we report, for the first time, two CF patients homozygous for the complex allele. All nine patients exhibited severe clinical symptoms.

Notably, p.(Ile1023_Val1024del) has been reported as a CF-causing variant, while p.(Ile148Thr) has been classified as a neutral common CFTR variant that does not affect the pathogenicity of additional variants in complex alleles [

15]. The classification for these variants is in line with the CFTR (

https://cftr.iurc.montp.inserm.fr and

http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca) databases [

16,

17].

In this study, we documented the structural impact of a complex allele and each independent variant on the CFTR protein, using an in silico analysis. The protein conformation derived from the complex allele showed more severe changes compared with the conformation associated with each independent variant. The p.(Ile1023_Val1024del) variant, which involves a deletion of the ATAGTG sequence in CFTR exon 19, results in the removal of isoleucine and valine at residues 1023 and 1024 in the TMD2 domain [

18,

19]. In addition, protein modeling revealed that this variant disrupts the secondary structure of CFTR, particularly affecting helix 10 of TMD2, which is essential for its stabilization. This analysis also showed misfolding affecting the R and NBD2 domains and the transmembrane domain connecting TMD2 and NBD2, suggesting that channel ion flow may be reduced.

Otherwise, modeling of the p.(Ile148Thr) variant indicates that it destabilizes the CFTR protein (ΔΔG Stability = −2.05 kcal/mol). Ile148 is located at the junction of the first and second helixes of TMD1 near the interface between the membrane and the cytoplasm. The substitution of Ile by Thr may significantly impact the protein’s structure, stability, and interactions, due to the significant differences in hydrophobicity and polarity between these two amino acids. In fact, we found that protein modeling with this amino acid substitution had a significant effect on the configuration of the TMD1, NBD, and R domains of CFTR. Furthermore, the MutationTaster tool classified this variant as disease-causing with a 99.9% probability. Supporting this, a previous functional study showed that nasal epithelial cells (NEC) from individuals carrying p.(Ile148Thr) exhibit a CFTR gating activity of 86%– 87.4%, and induce in patients a variable spectrum of clinical characteristics with null or mild effects, displaying mild channel impairment [

15]. Perhaps this dysfunction is not enough to cause CF manifestations, although it has been reported that in some patients this variant

in trans with a PV may result in CF-like symptoms [

20] or result in a diagnosis of a CFTR-related disorder [

18].

Finally, our modeling suggests that the p.(Ile148Thr) and p.[Ile1023_Val1024del] variants

in cis synergistically affect protein conformation, narrowing the channel and thus altering the ion flow even more, as previously documented on individuals carrying the complex allele along with other Class I and II variants, who displayed a CFTR gating activity on NEC of 7.3% [

15,

20].

A growing body of evidence has demonstrated that patients carrying complex alleles could have altered CFTR biogenesis, inducing a variable spectrum of clinical characteristics which makes diagnosis more complicated. Furthermore, the presence of this alleles could induce a different response to the target drugs, such as elexacaftor/ivacaftor/tezacaftor, highlighting the importance of NGS of CFTR for accurate diagnosis and for personalizing therapeutic strategies to improve patient outcomes [

21,

22].

To estimate the frequency of the complex allele in Mexico, we searched our laboratory’s exome-sequencing dataset for carriers of the complex allele, as well as the individual variants p.(Ile148Thr) and p.(Ile1023_Val1024del). We identified no carriers of the p.(Ile1023_Val1024del), eight carriers of the p.(Ile148Thr), and the complex allele in only one individual, also of Central Mexican origin, suggesting a founder effect. The CFTR-France database shows that the p.[Ile148Thr;Ile1023_Val1024del] complex allele occurs in 23.53% of CF cases [

16]. Moreover, it has been reported that this allele is present in 2.2% of CF patients from Quebec City, Canada [

19]. In our patients, the p.[Ile148Thr;Ile1023_Val1024del] allele was present at a frequency of 0.18%. Notably, this complex allele has not been reported in other populations and is absent from the CFTR2 database, highlighting the importance of these results. Historical records indicate that French-Canadian immigrants settled in Mexico in the late 19th century, mainly in cities of Central Mexico, driven by the growth of industries such as electrical infrastructure, mining, and railways [

23,

24]. This context, coupled with the geographic origin of the complex allele carriers, allows us to suggest that this allele may be of French origin and introduced to America through the French-Canadian population, who much later brought it into the population of Central Mexico, supporting our founder effect hypothesis.

5. Conclusions

Our study provides evidence that the p.(Ile148Thr) variant is pathogenic and underscores the importance of monitoring the clinical outcomes of patients carrying this variant to fully understand its implications. Additionally, our findings support the integration of NGS into CF diagnostics to ensure the identification of all CF alleles, including complex alleles such as p.[Ile148Thr;Ile1023_Val1024del], which is associated with severe clinical manifestations, including early mortality. NGS diagnosis is crucial for developing personalized treatment strategies and improving patient quality of life.

All examples we found of the complex allele are in individuals of Central Mexico, likely due to migration flow from the French-Canadian population during the 19th century. This suggests a founder effect among Mexican CF patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M-H and L.O.; resources, E.L., V.B. and JL.L. methodology, C.A-V, C.C-C, F.B-O, AL.Y-F, JL.J-R, T.MC, JR.V-F; investigation, NG.M-V, AL.Y-F, E.M-C., JR.V-F, F.B-O, F.C-C, H.G-O; writing—original draft preparation, C.C-C, A.M-H, L.O,F.B-O, H.G-O, NG.M-V, writing—review and editing A.M-H, L.O, C.C-C; supervision, A.M-H and L.O.; project administration, A.M-H, L.O; funding acquisition, A.M-H and L.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica (INMEGEN), SS, Tlalpan, 14610, Mexico City, Mexico. Project # 12/2015/I.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica (INMEGEN)(Project # 12/2015/I).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank patients and their families who participated in the study, CONAHCYT for the 2023-000002-01NACF-05918 scholarship awarded to Namibia G Mendiola-Vidal, and the sequencing unit of INMEGEN.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

-

https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/68702.

- Martínez-Hernández, A.; Larrosa, J.; Barajas-Olmos, F.; García-Ortíz, H.; Mendoza-Caamal, EC.; Contreras-Cubas, C.; Mirzaeicheshmeh, E.; Lezana, JL.; Orozco, L. Next-generation sequencing for identifying a novel/de novo pathogenic variant in a Mexican patient with cystic fibrosis: a case report. BMC Med Genomics 2019,12,:68. [CrossRef]

- Kondratyeva, E.; Melyanovskaya, Y.; Efremova, A.; Krasnova, M.; Mokrousova, D.; Bulatenko, N.; Petrova, N.; Polyakov, A.; Adyan, T.; Kovalskaia, V.; Bukharova, T.; Marakhonov, A.; Zinchenko, R.; Zhekaite, E.; Buhonin, A.; Goldshtein, D. Clinical and Genetic Characteristics of a Patient with Cystic Fibrosis with a Complex Allele [E217G;G509D] and Functional Evaluation of the CFTR Channel. Genes (Basel) 2023,28,1705. [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, M.; Efremova, A.; Bukhonin, A.; Zhekaite, E.; Bukharova, T.; Melyanovskaya, Y.; Goldshtein, D.; Kondratyeva, E. The Effect of Complex Alleles of the CFTR Gene on the Clinical Manifestations of Cystic Fibrosis and the Effectiveness of Targeted Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25,114. [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo Ruiz, Victoria; Gildardo, Francisco Zafra de la Rosa; Rafael, Dulijh Uranga Hernández. (s. f.). Genética Clínica 2a Edición. Manual Moderno 2019, 651pp.

- Martínez-Hernández, A.; Mendoza-Caamal, EC.; Mendiola-Vidal, NG.; Barajas-Olmos, F.; Villafan-Bernal, JR.; Jiménez-Ruiz, JL.; Monge-Cazares, T.; García-Ortiz, H.; Cubas-Contreras, C.; Centeno-Cruz, F.; Alaez-Verson, C.; Ortega-Torres,S.; Luna-Castañeda, ADC.; Baca, V.; Lezana, JL.; Orozco, L. CFTR pathogenic variants spectrum in a cohort of Mexican patients with cystic fibrosis. Heliyon 2024,10,e28984.

- Bienvenu, T.; Lopez, M.; Girodon, E. Molecular Diagnosis and Genetic Counseling of Cystic Fibrosis and Related Disorders: New Challenges. Genes 2020 11,619. [CrossRef]

- Lucarelli, M.; Narzi, L.; Pierandrei, S.; Bruno, SM.; Stamato, A.; d’Avanzo, M.; Strom, R.; Quattrucci, S. A new complex allele of the CFTR gene partially explains the variable phenotype of the L997F mutation. Genet Med 2010,12,:548-55. [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, B.; Hinzpeter, A. The influence of CFTR complex alleles on precision therapy of cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2020, Suppl 1,S15-S18. [CrossRef]

- Kondratyeva, E.; Efremova, A.; Melyanovskaya, Y.; Voronkova, A.; Polyakov, A.; Bulatenko, N.; Adyan, T.; Sherman, V.; Kovalskaia, V.; Petrova, N..; Starinova, M.; Bukharova, T.; Kutsev, S.; Goldshtein, D. Evaluation of the Complex p.[Leu467Phe;Phe508del] CFTR Allele in the Intestinal Organoids Model: Implications for Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 8,10377. [CrossRef]

- Petrova, NV.; Kashirskaya, NY.; Vasilyeva, TA.; Balinova, NV.; Marakhonov, AV.; Kondratyeva, E.; Zhekaite, EK.; Voronkova, AY.; Kutsev, SI.; Zinchenko, RA. High frequency of complex CFTR alleles associated with c.1521_1523delCTT (F508del) in Russian cystic fibrosis patients. BMC Genomics. 2022,23,252. [CrossRef]

- Flannick, J.; Mercader, JM.; Fuchsberger, C.; Udler, MS.; Mahajan, A.; Wessel, J.; Teslovich, TM.; Caulkins, L.; Koesterer, R.; Barajas-Olmos, F.; et al. Exome sequencing of 20,791 cases of type 2 diabetes and 24,440 controls. Nature 2019, 570,71-76.

- SIGMA Type 2 Diabetes Consortium; Estrada. K.; Aukrust, I.; Bjørkhaug, L.; Burtt, NP.; Mercader, JM.; García-Ortiz, H.; et al. Association of a low-frequency variant in HNF1A with type 2 diabetes in a Latino population. JAMA 2014, 31, 2305-14.

- Sheridan, MB.; Aksit, MA.; Pagel, K.; Hetrick, K.; Shultz-Lutwyche, H.; Myers, B.; Buckingham, KJ.; Pace, RG.; Ling, H.; Pugh, E.; O’Neal, WK.; Bamshad, MJ.; Gibson, RL.; Knowles, MR.; Blackman, SM.; Cutting, GR.; Raraigh, KS. The clinical utility of sequencing the entirety of CFTR. J Cyst Fibros 2024, 23,707-715. [CrossRef]

- Terlizzi. V.; Castaldo, G.; Salvatore, D.; Lucarelli, M.; Raia, V.; Angioni, A.; Carnovale, V.; Cirilli, N.; Casciaro, R.; Colombo, C.; Di Lullo, AM.; Elce, A.; Iacotucci, P.; Comegna, M; Scorza, M.; Lucidi, V.; Perfetti, A.; Cimino, R.; Quattrucci, S.; Seia, M.; Sofia, VM.; Zarrilli, F.; Amato, F.; Genotype-phenotype correlation and functional studies in patients with cystic fibrosis bearing CFTR complex alleles. J Med Genet 2017,54,224-235. [CrossRef]

-

https://cftr.iurc.montp.inserm.fr/cftr/.

-

http://www.cftr2.org/.

- Monaghan, KG.; Highsmith, WE.; Amos, J.; Pratt, VM.; Roa, B.; Friez, M.; Pike-Buchanan, LL.; Buyse, IM.; Redman, JB.; Strom, CM.; Young, AL.; Sun, W. Genotype-phenotype correlation and frequency of the 3199del6 cystic fibrosis mutation among I148T carriers: results from a collaborative study. Genet Med 2004,6,421-5. [CrossRef]

- Ruchon, AF.; Ryan, SR.; Fetni, R.; Rozen, R.; Scott, P. Frequency and phenotypic consequences of the 3199del6 CFTR mutation in French Canadians. Genet Med 2005,7,210-1.

- Terlizzi V, Centrone C, Botti M, Taccetti G. G378X-I148T CFTR variant: A new complex allele in a cystic fibrosis newborn with pancreatic insufficiency. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2022, 10,e 2033. [CrossRef]

- Laselva, O.; Ardelean, MC.; Bear, CE.Phenotyping Rare CFTR Mutations Reveal Functional Expression Defects Restored by TRIKAFTATM. J Pers Med 2021,15,301. [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, M.; Efremova, A.; Bukhonin, A.; Zhekaite, E.; Bukharova, T.; Melyanovskaya, Y.; Goldshtein, D.; Kondratyeva, E. The Effect of Complex Alleles of the CFTR Gene on the Clinical Manifestations of Cystic Fibrosis and the Effectiveness of Targeted Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25,114. [CrossRef]

-

http://www.gobernacion.gob.mx/work/models/SEGOB/Resource/1353/4/images/Cobo_2012_canadienses_mpi.pdf.

-

https://migracionesinternacionales.colef.mx/index.php/migracionesinternacionales/article/view/237/438.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).