Submitted:

02 October 2024

Posted:

03 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focus Questions

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

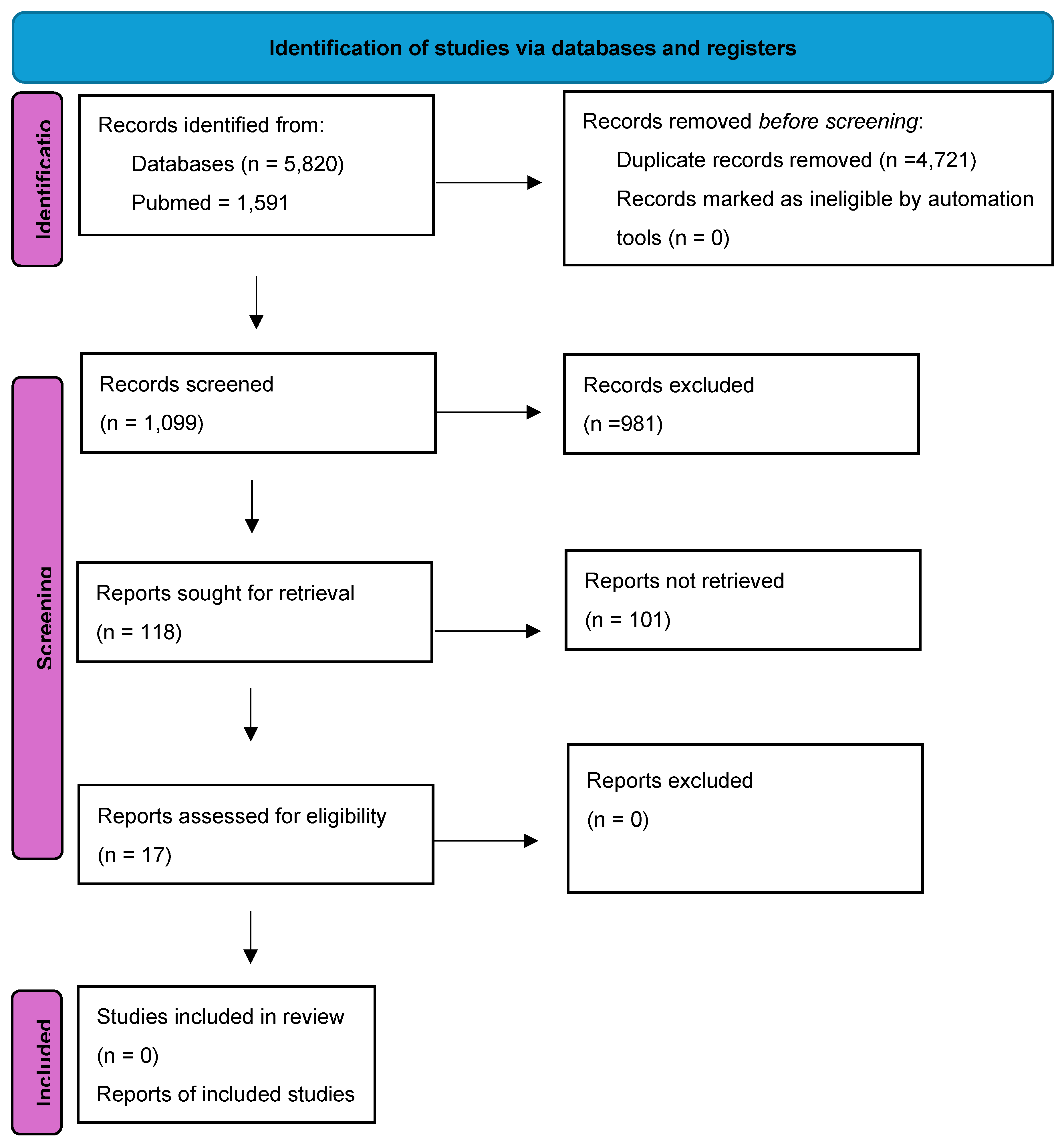

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Bacteria and Mercury Concentration

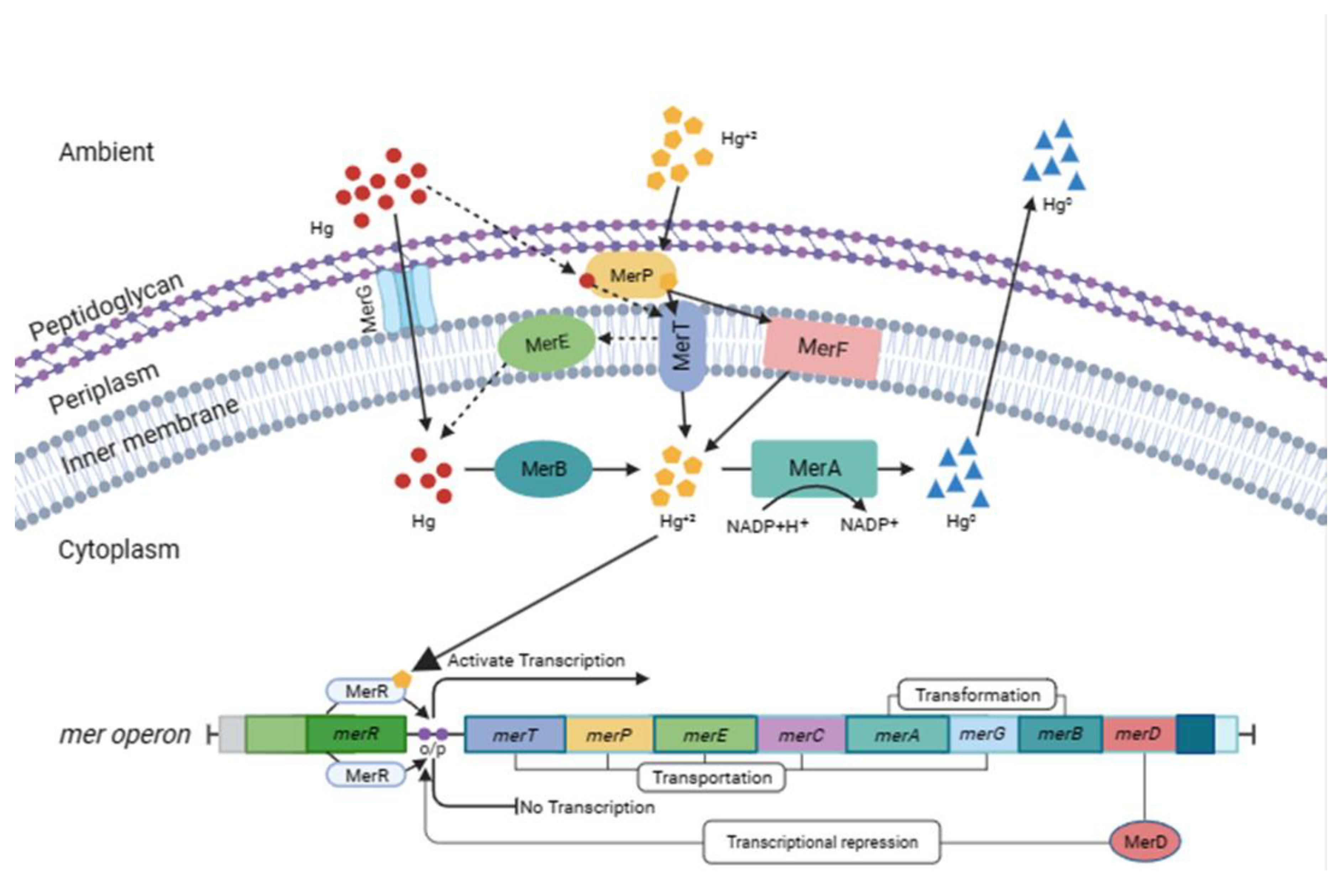

3.3. Genes Involved

3.4. Environments in Which the Gene Was Found

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Aminov, R.I., Mackie, R.I., 2007. Evolution and ecology of antibiotic resistance genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 271, 147–161. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.C.A., da Purificação-Júnior, A.F., da Silva, S.M., Lopes, A.C.S., Veras, D.L., Alves, L.C., dos Santos, F.B., Napoleão, T.H., dos Santos Correia, M.T., da Silva, M.V., Oliva, M.L.V., de Oliveira, M.B.M., 2019. In vitro evaluation of mercury (Hg2+) effects on biofilm formation by clinical and environmental isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 169, 669–677. [CrossRef]

- Aula, I., Braunschweiler, H., Malin, I., 1995. The watershed flux of mercury examined with indicators in the Tucuruí reservoir in Pará, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ., Mercury Pollution and Gold Mining in Brazil 175, 97–107. [CrossRef]

- Ayangbenro, A.S., Babalola, O.O., 2017. A New Strategy for Heavy Metal Polluted Environments: A Review of Microbial Biosorbents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 14, 94. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J.D.S., Sarkis, J.E.D.S., Oliveira, T.A., Ulrich, J.C., 2012. Tissue-specific mercury concentrations in two catfish species from the Brazilian coast. Braz. J. Oceanogr. 60, 209–217. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J.S., Braga, E.S., Favaro, D.T., Perretti, A.R., Rezende, C.E., Souza, C.M.M., 2011. Total mercury in sediments and in Brazilian Ariidae catfish from two estuaries under different anthropogenic influence. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 62, 2724–2731. [CrossRef]

- Azubuike, C.C., Chikere, C.B., Okpokwasili, G.C., 2016. Bioremediation techniques-classification based on site of application: principles, advantages, limitations and prospects. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32, 180. [CrossRef]

- Baquero, F., Martínez, J.-L., Cantón, R., 2008. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in water environments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19, 260–265. [CrossRef]

- Beim, A.M., Grosheva, E.I., 1992. Ecological chemistry of mercury contained in bleached kraft pulp mill effluents. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 65, 135–141. [CrossRef]

- Caille, O., Rossier, C., Perron, K., 2007. A Copper-Activated Two-Component System Interacts with Zinc and Imipenem Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Bacteriology 189, 4561–4568. [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, W., 2008. A world overview — One-hundred-twenty-seven years of research on toxic cyanobacteria — Where do we go from here?, in: Hudnell, H.K. (Ed.), Cyanobacterial Harmful Algal Blooms: State of the Science and Research Needs, Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Springer, New York, NY, pp. 105–125. [CrossRef]

- Catherine, Q., Susanna, W., Isidora, E.-S., Mark, H., Aurélie, V., Jean-François, H., 2013. A review of current knowledge on toxic benthic freshwater cyanobacteria – Ecology, toxin production and risk management. Water Research 47, 5464–5479. [CrossRef]

- Chakdar, H., Thapa, S., Srivastava, A., Shukla, P., 2022. Genomic and proteomic insights into the heavy metal bioremediation by cyanobacteria. J. Hazard. Mater. 424, 127609. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., B. Wilson, D., 1997. Construction and characterization of Escherichia coli genetically engineered for bioremediation of Hg(2+)-contaminated environments [WWW Document]. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Zhang, X., Ma, Y., Song, Y., Li, Y., Geng, G., Huang, Y., 2020. Anammox biofilm system under the stress of Hg(II): Nitrogen removal performance, microbial community dynamic and resistance genes expression. J. Hazard. Mater. 395, 122665. [CrossRef]

- Chenia, H., Jacobs, A., 2017. Antimicrobial resistance, heavy metal resistance and integron content in bacteria isolated from a South African tilapia aquaculture system. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 126, 199–209. [CrossRef]

- Condini, M.V., Hoeinghaus, D.J., Roberts, A.P., Soulen, B.K., Garcia, A.M., 2017. Mercury concentrations in dusky grouper Epinephelus marginatus in littoral and neritic habitats along the Southern Brazilian coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 115, 266–272. [CrossRef]

- Dash, H.R., Das, S., 2012. Bioremediation of mercury and the importance of bacterial mer genes. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 75, 207–213. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Alvarez, C.G., Ruelas-Inzunza, J., Osuna-López, J.I., Voltolina, D., Frías-Espericueta, M.G., 2015. Mercury content and their risk assessment in farmed shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei from NW Mexico. Chemosphere 119, 1015–1020. [CrossRef]

- Díez, S., 2009. Human health effects of methylmercury exposure. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 198, 111–132. [CrossRef]

- Dismukes, G.C., Carrieri, D., Bennette, N., Ananyev, G.M., Posewitz, M.C., 2008. Aquatic phototrophs: efficient alternatives to land-based crops for biofuels. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., Energy biotechnology / Environmental biotechnology 19, 235–240. [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, C.T., Mason, R.P., Chan, H.M., Jacob, D.J., Pirrone, N., 2013. Mercury as a Global Pollutant: Sources, Pathways, and Effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 4967–4983. [CrossRef]

- Fenske, G.J., Scaria, J., 2021. Analysis of 56,348 Genomes Identifies the Relationship between Antibiotic and Metal Resistance and the Spread of Multidrug-Resistant Non-Typhoidal Salmonella. Microorganisms 9. [CrossRef]

- Gontia-Mishra, I., Sapre, S., Sharma, A., Tiwari, S., 2016. Alleviation of Mercury Toxicity in Wheat by the Interaction of Mercury-Tolerant Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria. J. PLANT GROWTH Regul. 35, 1000–1012. [CrossRef]

- Guedron, S., Cossa, D., Grimaldi, M., Charlet, L., 2011. Methylmercury in tailings ponds of Amazonian gold mines (French Guiana): Field observations and an experimental flocculation method for in situ remediation. Appl. Geochem., Mercury biogeochemical cycling in mercury contaminated environments 26, 222–229. [CrossRef]

- Gworek, B., Dmuchowski, W., Baczewska-Dąbrowska, A.H., 2020. Mercury in the terrestrial environment: a review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 32, 128. [CrossRef]

- Hao, J., Yu, M., Jia, L., 2007. Synergistic effects of proteasome inhibitor on TRAIL-induced apoptosis in malignant lymphoma cells. Chin. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 9–11.

- Harayashiki, C.A.Y., Reichelt-Brushett, A., Cowden, K., Benkendorff, K., 2018. Effects of oral exposure to inorganic mercury on the feeding behaviour and biochemical markers in yellowfin bream (Acanthopagrus australis). Mar. Environ. Res. 134, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Heimann, K., Cirés, S., 2015. Chapter 33 - N2-Fixing Cyanobacteria: Ecology and Biotechnological Applications, in: Kim, S.-K. (Ed.), Handbook of Marine Microalgae. Academic Press, Boston, pp. 501–515. [CrossRef]

- Hennebel, T., Boon, N., Maes, S., Lenz, M., 2015. Biotechnologies for critical raw material recovery from primary and secondary sources: R&D priorities and future perspectives. New Biotechnol. 32, 121–127. [CrossRef]

- Hintelmann, H., 2010. Organomercurials. Their Formation and Pathways in the Environment. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M., Nabavi, S.M.B., Parsa, Y., 2013. Bioaccumulation of Trace Mercury in Trophic Levels of Benthic, Benthopelagic, Pelagic Fish Species, and Sea Birds from Arvand River, Iran. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 156, 175–180. [CrossRef]

- Hutcheson, M.S., Smith, C.M., Rose, J., Batdorf, C., Pancorbo, O., West, C.R., Strube, J., Francis, C., 2014. Temporal and Spatial Trends in Freshwater Fish Tissue Mercury Concentrations Associated with Mercury Emissions Reductions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 2193–2202. [CrossRef]

- Istiaq, A., Shuvo, M.S.R., Rahman, K.M.J., Siddique, M.A., Hossain, M.A., Sultana, M., 2019. Adaptation of metal and antibiotic resistant traits in novel β-Proteobacterium Achromobacter xylosoxidans BHW-15. PeerJ 7, e6537. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., Zhang, N., Yang, X., Song, L., Yang, S., 2016. Toxic metal biosorption by macrocolonies of cyanobacterium Nostoc sphaeroides Kützing. J. Appl. Phycol. 28, 2265–2277. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G., Meena, B., Verma, P., Nayak, J., Vinithkumar, N.V., Dharani, G., 2021. Deep-sea mercury resistant bacteria from the Central Indian Ocean: A potential candidate for mercury bioremediation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 169, 112549. [CrossRef]

- Kane, A.L., Al-Shayeb, B., Holec, P.V., Rajan, S., Mieux, N.E.L., Heinsch, S.C., Psarska, S., Aukema, K.G., Sarkar, C.A., Nater, E.A., Gralnick, J.A., 2016. Toward Bioremediation of Methylmercury Using Silica Encapsulated Escherichia coli Harboring the mer Operon. PLOS ONE 11, e0147036. [CrossRef]

- Kardena, E., Panha, Y., Helmy, Q., Hidayat, S., 2020. APPLICATION OF MERCURY RESISTANT BACTERIA ISOLATED FROM ARTISANAL SMALL-SCALE GOLD TAILINGS IN BIOTRANSFORMATION OF MERCURY (II) - CONTAMINATED. Int. J. GEOMATE 19, 106–114. [CrossRef]

- Kojadinovic, J., Potier, M., Le Corre, M., Cosson, R.P., Bustamante, P., 2007. Bioaccumulation of trace elements in pelagic fish from the Western Indian Ocean. Environ. Pollut., Lichens in a Changing Pollution Environment 146, 548–566. [CrossRef]

- Kolka, R.K., Nater, E.A., Grigal, D.F., Verry, E.S., 1999. Atmospheric inputs of mercury and organic carbon into a forested upland/bog watershed. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 113, 273–294. [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, L.D., 1997. Evolution of Mercury Contamination in Brazil. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 97, 247–255. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Lee, S., Jiang, X., 2017. Cyanobacterial Toxins in Freshwater and Food: Important Sources of Exposure to Humans. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology 8, 281–304. [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, D.D., Kelly, D., Budd, K., 2007. Biotransformation of Hg(II) by Cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 243–249. [CrossRef]

- Leopold, K., Foulkes, M., Worsfold, P., 2010. Methods for the determination and speciation of mercury in natural waters—A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 663, 127–138. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Flora, J.R.V., Caicedo, J.M., Berge, N.D., 2015. Investigating the role of feedstock properties and process conditions on products formed during the hydrothermal carbonization of organics using regression techniques. Bioresour. Technol. 187, 263–274. [CrossRef]

- Lo, K., Lu, C., Liu, F., Kao, C., Chen, S., 2022. Draft genome sequence of Pseudomonas sp. A46 isolated from mercury-contaminated wastewater. J. BASIC Microbiol. 62, 1193–1201. [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, K.R., Krishnan, K., Naidu, R., Andrews, S., Megharaj, M., 2017. Mercury toxicity to terrestrial biota. Ecol. Indic. 74, 451–462. [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, K.R., Krishnan, K., Naidu, R., Megharaj, M., 2016. Mercury resistance and volatilization by Pseudoxanthomonas sp. SE1 isolated from soil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 6, 94–104. [CrossRef]

- Mangal, V., Stenzler, B.R., Poulain, A.J., Guéguen, C., 2019. Aerobic and Anaerobic Bacterial Mercury Uptake is Driven by Algal Organic Matter Composition and Molecular Weight. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 157–165. [CrossRef]

- Mata, M.T., Baquero, F., Pérez-Díaz, J.C., 2000. A multidrug efflux transporter in Listeria monocytogenes. FEMS Microbiology Letters 187, 185–188. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, N., Rastegari, H., Kargar, M., 2013. Antibiotic resistance pattern among gram negative mercury resistant bacteria isolated from contaminated environments. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 6. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.C., Pivetta, F., 1997. Human and environmental contamination by mercury from industrial uses in Brazil. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 97, 241–246. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G.W., Newcomb, T.J., Orth, D.J., 2007. Sexual and Seasonal Variations of Mercury in Smallmouth Bass. J. Freshw. Ecol. 22, 135–143. [CrossRef]

- Nriagu, J.O., 1993. Mercury pollution from silver mining in colonial South America. In: Abrao, J.J., Wasserman, J.C., Silva Filho, E.V. (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Symposium Perspectives for Environmental Geochemistry in Tropical Countries. Lewis, London, pp. 365e368. En13-5-93-10-eng.pdf (publications.gc.ca).

- Onsanit, S., Wang, W.-X., 2011. Sequestration of total and methyl mercury in different subcellular pools in marine caged fish. J. Hazard. Mater. 198, 113–122. [CrossRef]

- Pacyna, E.G., Pacyna, J.M., 2002. Global Emission of Mercury from Anthropogenic Sources in 1995. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 137, 149–165. [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshanee, M., Chatterjee, S., Rath, S., Dash, H.R., Das, S., 2022. ok Cellular and genetic mechanism of bacterial mercury resistance and their role in biogeochemistry and bioremediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 423, 126985. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Z., Singh, V.P., 2018. ok Assessment of heavy metal contamination and Hg-resistant bacteria in surface water from different regions of Delhi, India. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 25, 1687–1695. [CrossRef]

- Ren, T., Xu, S., Zhao, W.-B., Zhu, J.-J., 2005. A surfactant-assisted photochemical route to single crystalline HgS nanotubes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 173, 93–98. [CrossRef]

- Roulet, M., Lucotte, M., Canuel, R., Farella, N., Courcelles, M., Guimarães, J.-R.D., Mergler, D., Amorim, M., 2000. Increase in mercury contamination recorded in lacustrine sediments following deforestation in the central Amazon1The present investigation is part of an ongoing study, the CARUSO project (CRDI-UFPa-UQAM), initiated to determine the sources, fate and health effects of the presence of MeHg in the area of the Lower Tapajós.1. Chem. Geol. 165, 243–266. [CrossRef]

- Ruus, A., Øverjordet, I.B., Braaten, H.F.V., Evenset, A., Christensen, G., Heimstad, E.S., Gabrielsen, G.W., Borgå, K., 2015. Methylmercury biomagnification in an Arctic pelagic food web. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 34, 2636–2643. [CrossRef]

- Rytuba, J.J., 2000. Mercury mine drainage and processes that control its environmental impact. Sci. Total Environ., Proceedings of the Fifth 260, 57–71. [CrossRef]

- S. Baishaw, J. Edwards, B. Daughtry, K. Ross, 2007. Mercury in seafood: Mechanisms of accumulation and consequences for consumer health. Rev. Environ. Health 22, 91–114. [CrossRef]

- Sadhu, A.K., Kim, J.P., Furrell, H., Bostock, B., 2015. Methyl mercury concentrations in edible fish and shellfish from Dunedin, and other regions around the South Island, New Zealand. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 101, 386–390. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Merino, M., Singh, A.K., Ducat, D.C., 2019. New applications of synthetic biology tools for cyanobacterial metabolic engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L., Li, Zhanfei, Wang, J., Liu, A., Li, Zhenhua, Yu, R., Wu, X., Liu, Y., Li, J., Zeng, W., 2018. Characterization of extracellular polysaccharide/protein contents during the adsorption of Cd(II) by Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25, 20713–20722. [CrossRef]

- Sierra, M.A., Martínez-Álvarez, R., 2020. Ricin and Saxitoxin: Two Natural Products That Became Chemical Weapons. J. Chem. Educ. 97, 1707–1714. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.K., Lingaswamy, B., Koduru, T.N., Nagu, P.P., Jogadhenu, P.S.S., 2019. A putative merR family transcription factor Slr0701 regulates mercury inducible expression of MerA in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. MicrobiologyOpen 8, e00838. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.S., Kumar, A., Rai, A.N., Singh, D.P., 2016. Cyanobacteria: A Precious Bio-resource in Agriculture, Ecosystem, and Environmental Sustainability. Front. Microbiol. 7.

- Sun, T., Li, S., Song, X., Diao, J., Chen, L., Zhang, W., 2018. Toolboxes for cyanobacteria: Recent advances and future direction. Biotechnol. Adv. 36, 1293–1307. [CrossRef]

- Taj, M.K., Samreen, Z., Ling, J.X., Taj, I., Hassani, T.M., Yunlin, W., 2014. ESCHERICHIA COLI AS A MODEL ORGANISM.

- Ting-Jing, H., Xiao-Yan, C., Xue-Fei, L., Jing-Shu, W., Jing-Hai, Y., Chun-Xiao, G., 2015. In Situ Electrical Resistivity and Hall Effect Measurement of β-HgS under High Pressure. Chin. Phys. Lett. 32, 016402. [CrossRef]

- Tirkey, J., Adhikary, S.P., 2005. Cyanobacteria in biological soil crusts of India. Curr. Sci. 89, 515–521.

- UN Environment, 2019. Global Mercury Assessment 2018 [WWW Document]. URL https://www.unep.org/globalmercurypartnership/resources/report/global-mercury-assessment-2018 (accessed 6.2.23).

- USEPA, 1997. Mercury study report to Congress EPA-452/R-97-004. https://archive.epa.gov/mercury/archive/web/pdf/volume1.pdf.

- van der Merwe, D., 2015. Chapter 31 - Cyanobacterial (Blue-Green Algae) Toxins, in: Gupta, R.C. (Ed.), Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents (Second Edition). Academic Press, Boston, pp. 421–429. [CrossRef]

- van Elsas, J.D., Bailey, M.J., 2002. The ecology of transfer of mobile genetic elements. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 42, 187–197. [CrossRef]

- von Canstein, H., Li, Y., Timmis, N., Deckwer, W.-D., Wagner-Döbler, I., 1999. Removal of Mercury from Chloralkali Electrolysis Wastewater by a Mercury-Resistant Pseudomonas putidaStrain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 5279–5284. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Z., Li, D., He, M., 2015. Application of internal standard method in recombinant luminescent bacteria test. J. Environ. Sci. China 35, 128–134. [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.M., Nislow, K.H., Folt, C.L., 2010. Bioaccumulation syndrome: identifying factors that make some stream food webs prone to elevated mercury bioaccumulation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1195, 62–83. [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Cui, Y., Jie, Y., En-Jie, Z., Chun-Xiao, G., 2011. Study of electronic and elastic properties of β-HgS under high pressure via first-principles calculations. Phys. Status Solidi C 8, 1703–1707. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Wei, S., Hobman, J., Dodd, C., 2020. Antibiotic and Metal Resistance in Escherichia coli Isolated from Pig Slaughterhouses in the United Kingdom. Antibiot.-BASEL 9. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D., Zhai, J., Yong, D., Dong, S., 2013. A rapid and sensitive p-benzoquinone-mediated bioassay for determination of heavy metal toxicity in water. The Analyst 138, 3297–3302. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z., Gunn, L., Wall, P., Fanning, S., 2017. Antimicrobial resistance and its association with tolerance to heavy metals in agriculture production. Food Microbiology 64, 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z., Li, J., Li, Y., Wang, Q., Zhai, X., Wu, G., Liu, P., Li, X., 2014. A mer operon confers mercury reduction in a Staphylococcus epidermidis strain isolated from Lanzhou reach of the Yellow River. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 90, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Zavilgelsky, G.B., Kotova, V.Y., Melkina, O.E., Pustovoit, K.S., 2014. Antirestriction activity of the mercury resistance nonconjugative transposon Tn5053 is controlled by the protease ClpXP. Russ. J. Genet. 50, 910–915. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Chen, L., Liu, D., 2012. Characterization of a marine-isolated mercury-resistant Pseudomonas putida strain SP1 and its potential application in marine mercury reduction. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 93, 1305–1314. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M., Zheng, G., Kang, X., Zhang, X., Guo, J., Wang, S., Chen, Y., Xue, L., 2023. Aquatic Bacteria Rheinheimera tangshanensis New Ability for Mercury Pollution Removal. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24. [CrossRef]

| Source | Bacteria (n)* | Genes | Experimental design | [Hg] Tested | [Hg] max¹ | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Staphylococcus epidermidis | merA, merT, merC and merR | PCR | 40 - 100 µM | 100 µM | Yu et al. | ||

| Laboratory | Synechocystis sp | merA and merR | PCR | 0 – 500 µM | 500µM | Singh et al. | ||

| Wellwater |

Achromobacter xylosoxidans | merR, merT, merP, merC, merA, merD, merE and merR | WGS | - | - | Istiaq et al. | ||

| Laboratory | Escherichia coli | merR | laboratory manipulation | 5 nmol L-1 | 5 nmol L-1 | Mangal et al. | ||

| Soil | Enterobacter cloacae, Enterobacter ludwigii and Klebsiella pneumoniae | mer operon (merA) | Laboratory manipulation | 10 - 250µM and 25 - 500 µM |

200 µM and 500 µM |

Gontia-Mishra et al. | ||

| Laboratory | Salmonella enterica I 4,[5],12:i:- | merR and merT | in silico | - | - | Fenske and Scaria | ||

| Laboratory | anammox bacteria of the genus Candidatus Kuenenia | merA, merB, merD and merR | PCR | 0 - 50 mg L-1 | 50 mg L-1 | Chen et al. | ||

| Slaughterhouses | Escherichia coli | merA and merC | PCR | 25 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL |

25 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL |

Yang et al. | ||

| River water | Klebsiella sp., Escherichia coli, Serratia marcescens, Proteus sp., Citrobacter sp., Pseudomonas sp., Acinetobacter sp. and Enterobacter sp. | merA, merD, merR, merP, merT and merB | Isolation | 10 mg L-1 | 10 mg L-1 | Mirzaei et al. | ||

| Water of aquaculture system | Aeromonas sp., Salmonella sp., Shewanella sp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Myroides odoratus, Serratia liquefaciens, Vibrio fluvialis and Chryseobacterium sp. | merA | PCR | 0.005 – 2.5 mM | 2 mM | Chenia and Jacobs | ||

| Laboratory | Escherichia coli K12 | merR | - | - | Zavilgelsky et al. | |||

| Laboratory | Escherichia coli | merR | Laboratory manipulation | mmol L-1 | 10 μmol L-1 | Wang et al. | ||

| Laboratory | Bacillus cereus, Bacillus sp. and Brevundimonas diminuta | merA, merP, merT and merB | Isolation | 50 - 500 ppm | 500 ppm | Kardena et al. | ||

| Wastewater | Rheinheimera tangshanensis | merT, merR, merC, and merA | PCR | 0 - 120 mg L-1 | solid medium: 120 mg L-1 and liquid medium: 60 mg L-1 |

Zhao et al. | ||

| Seawater | Pseudomonas, Bacillus and Pseudoalteromonas | merA | PCR | 25 - 100 mg L-1 | 100 mg L-1 | Joshi et al | ||

| Wastewater | Pseudomonas | merR, merA and merT | WGS | - | 60 ppm | Lo et al. | ||

| Soil | Pseudoxanthomonas sp. | merA | PCR | 1 - 6 mg L-1 and 5 - 80 mg L-1 |

3 mg L-1 and 40 mg L-1 |

Mahbub et al. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).