3.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 150 participants were included in the analysis, with an average symptom severity score of 3.8 (SD = 0.9) and an average symptom duration of 4.5 days (SD = 1.8). Participants reported using a range of management strategies, including home remedies (40%), over-the-counter medications (35%), prescription medications (20%), and medical treatment (5%).

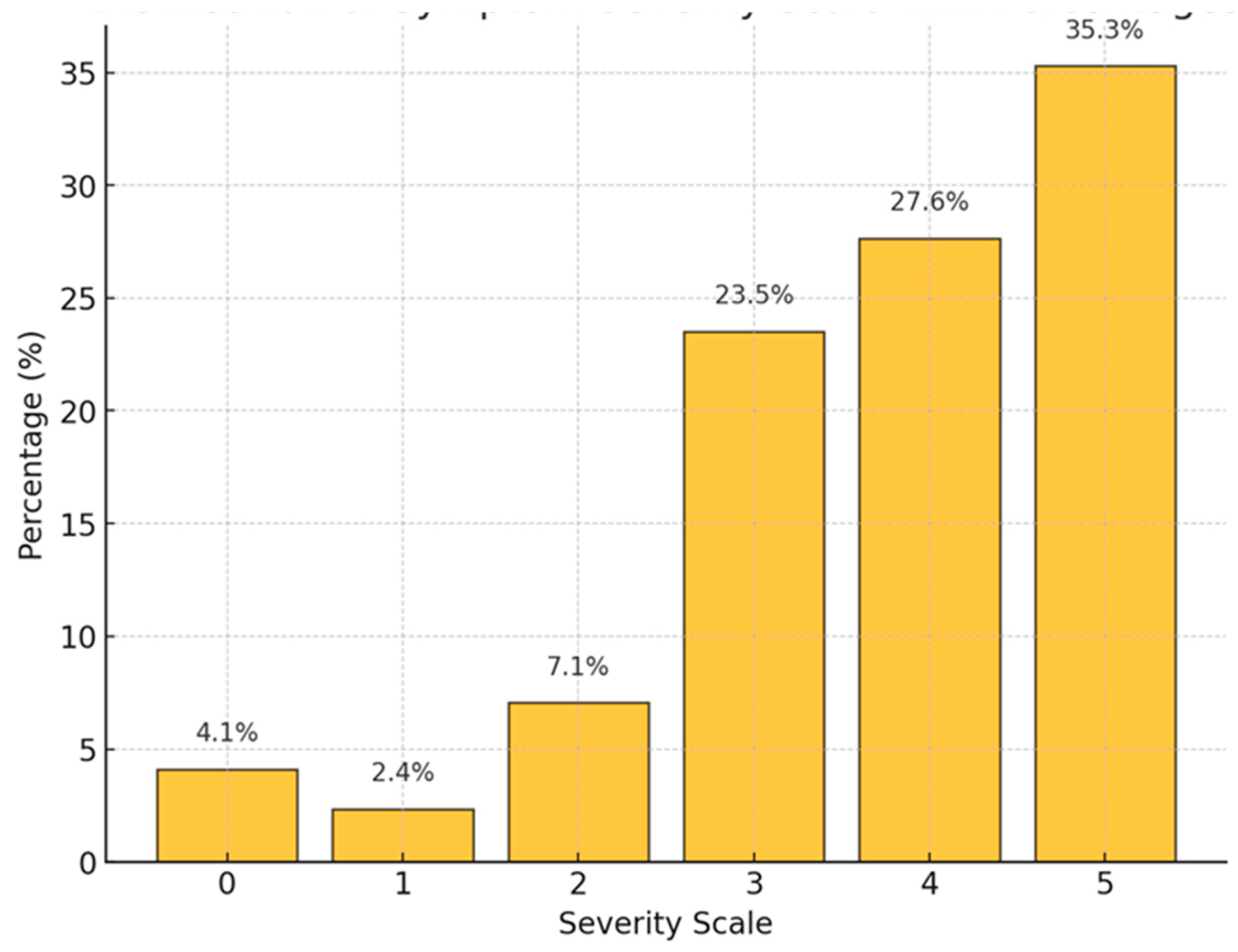

In

Figure 1 the distribution of symptom severity ratings reveals a concentration of responses at the higher end of the scale, with 35.3% of respondents reporting a severity level of 5 and 27.6% at level 4. This indicates that a substantial portion of the sample experienced severe symptoms. In contrast, a smaller segment of respondents reported moderate severity, with 23.5% at a severity level of 3, representing a notable but less prominent group with moderate symptom levels. Only a minimal fraction of the sample reported low severity, with 7.1% at level 2, 2.4% at level 1, and 4.1% at level 0, suggesting that mild or no symptoms were relatively rare. The overall distribution is right-skewed, with higher severity levels more frequently reported than lower ones. This skewed pattern implies that the sample is predominantly composed of individuals experiencing significant symptom burdens, which may reflect the nature of the symptoms studied or characteristics of the patients. The data suggests that most patients perceive their symptoms as severe, with fewer reporting moderate or low severity levels. This pattern may inform targeted interventions or further analyses to understand factors contributing to high symptom severity.

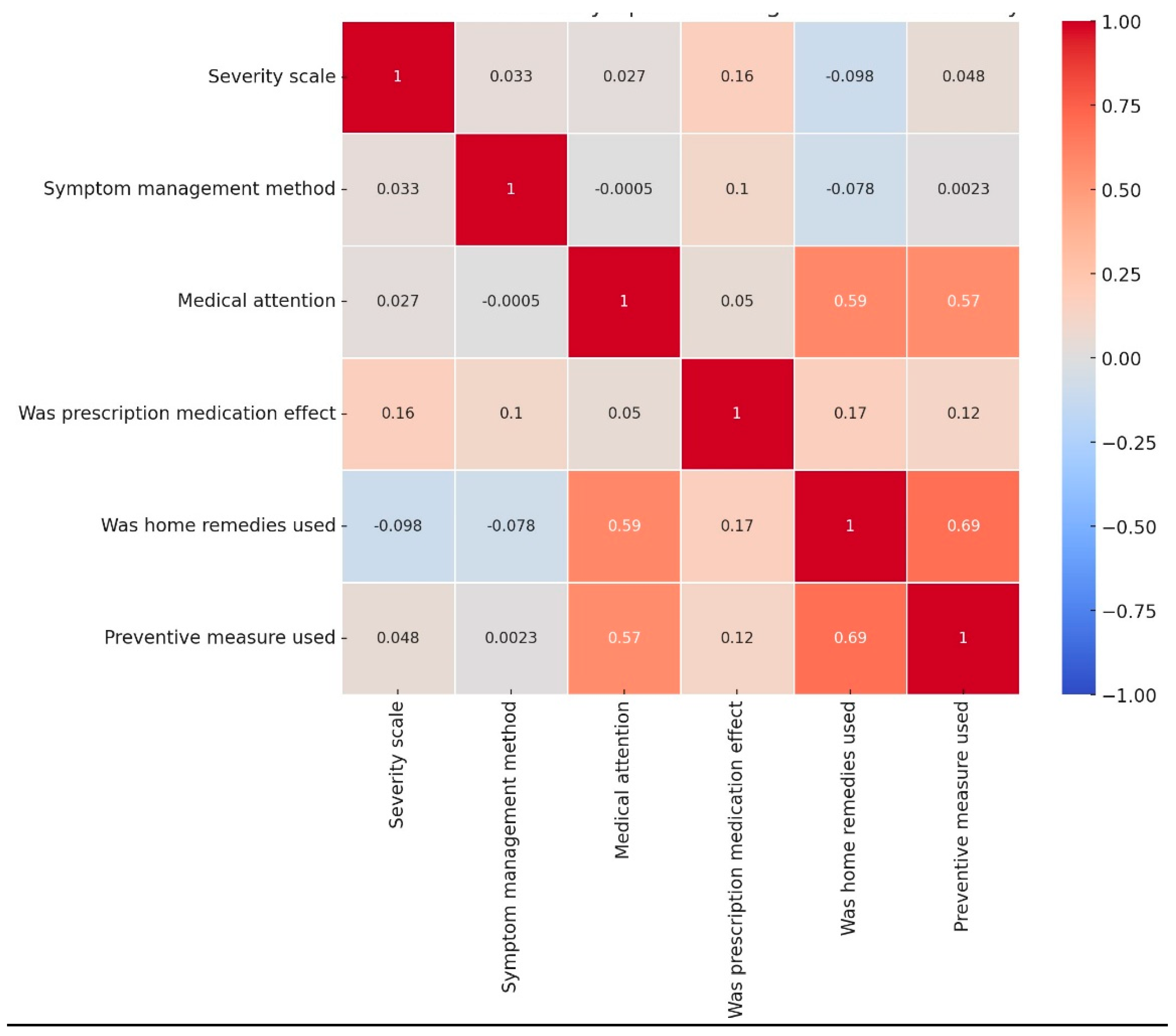

The multivariate analysis assessed the relationship between symptom severity and two predictors namely; symptom management method and symptom duration. The overall model showed an R2 value of 0.004, indicating that the independent variables explain only 0.4% of the variation in severity scores. This suggests that symptom management method and symptom duration are poor predictors of severity. Additionally, the F-statistic p-value of 0.745 confirmed that the model as a whole is not statistically significant. Regarding the independent variables, the symptom management method had a coefficient of 4.33×10−6 with a p-value of 0.680, demonstrating no meaningful or statistically significant effect on symptom severity. Similarly, the symptom duration had a coefficient of -0.1361 with a p-value of 0.523, reflecting a weak and statistically insignificant negative association with severity. While longer symptom duration might slightly reduce severity scores, this effect is not robust or reliable. The results suggest that the independent variables; symptom management method and symptom duration do not significantly explain or predict variation in symptom severity.

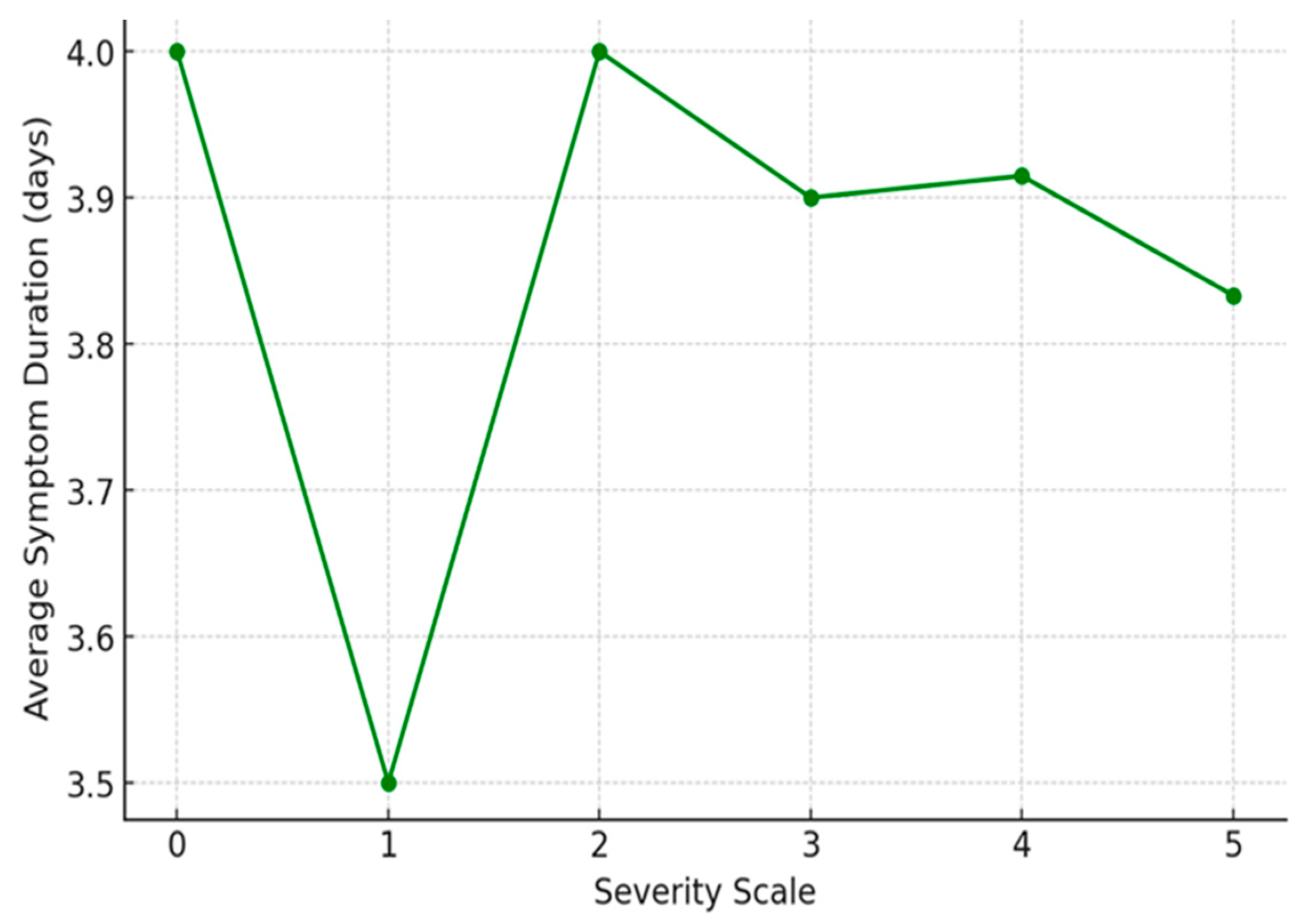

Figure 2. Examination of the relationship between the severity of flu symptoms and the average duration of these symptoms among the respondents (average =3.9). The percentages illustrate the proportion of respondents who fall into each severity level category in relation to the overall symptom duration. Despite the severity variations, the duration of symptoms remains consistently close to 4 days across all levels.

Severity Level 0: Respondents who reported no symptoms over the average of 4 days

Severity Level 1: Respondents who reported the mildest symptoms (Severity 1) experienced symptoms for an average of 3.5 days.

Severity Level 2: For those reporting mild to moderate symptoms (Severity 2), the average duration was slightly higher at 4.0 days.

Severity Level 3: Participants who rated their symptoms as moderate (Severity 3) had an average symptom duration of 3.9 days.

Severity Level 4: Respondents at this severity level experienced symptoms for approximately 3.91 days on average.

Severity Level 5: Despite reporting the most severe symptoms, these respondents had an average duration of 3.83 days, which is slightly less than that of severity levels 2 to 4.

The data on symptom severity and duration reveals a consistent average duration of symptoms across different severity levels, ranging from 3.5 to 4 days. Patients who reported no symptoms (severity level 0) experienced no symptoms over the average of four days. Those with the mildest symptoms (severity level 1) reported an average duration of 3.5 days. For patients with mild to moderate symptoms (severity level 2), the duration increased slightly to 4.0 days. Patients who rated their symptoms as moderate (severity level 3) experienced an average duration of 3.9 days, while those at severity level 4 reported a similar duration of 3.91 days. Interestingly, respondents with the most severe symptoms (severity level 5) experienced an average symptom duration of 3.83 days, slightly lower than those at severity levels 2 to 4. This suggests that the duration of symptoms is relatively stable regardless of severity, with no clear trend of increasing or decreasing duration as symptom severity increases. This observation challenges the expectation that more severe symptoms would correlate with longer illness durations. It implies that factors beyond symptom intensity, such as individual immune responses or the effectiveness of treatments, may play a critical role in determining the overall length of the illness.

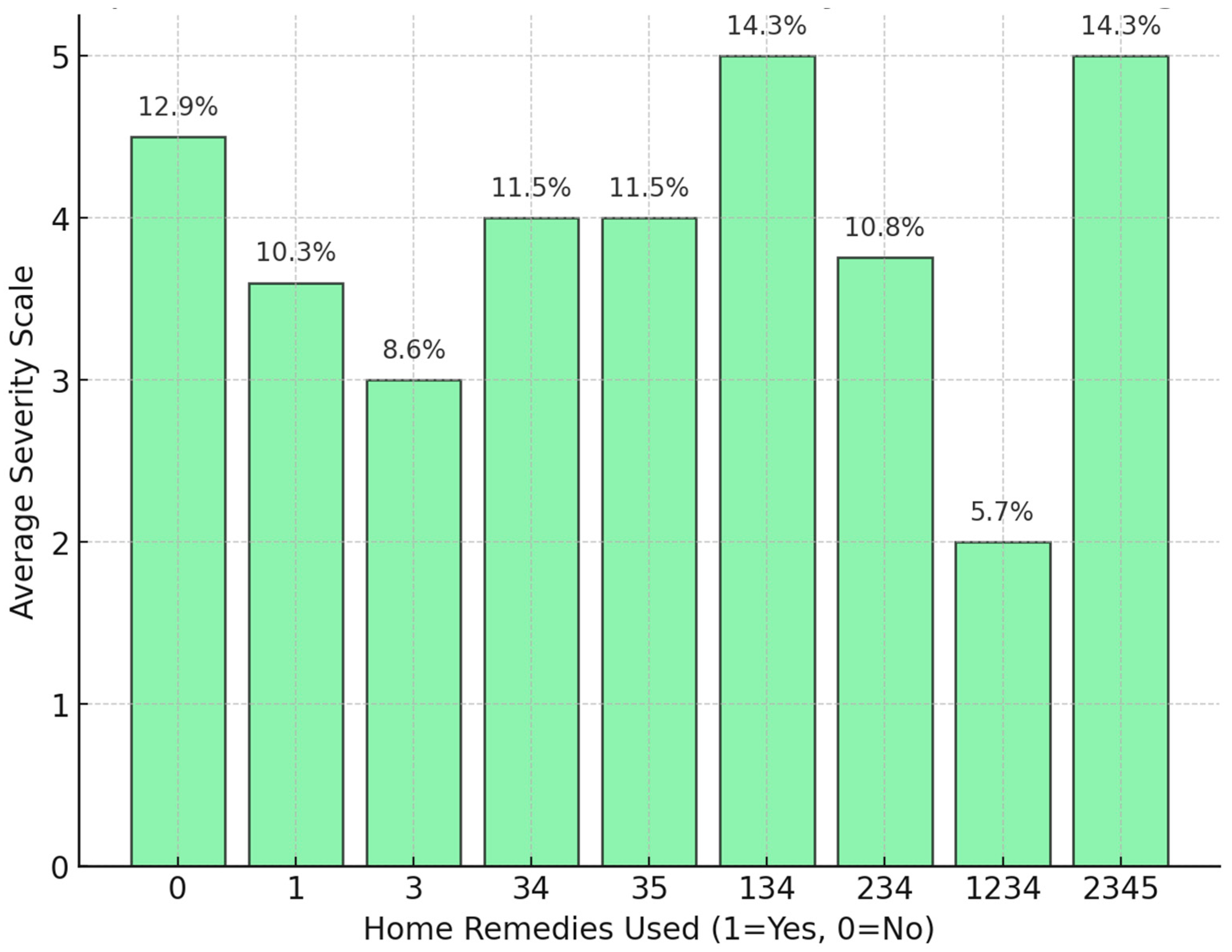

Figure 3, reveals differences in symptom severity levels based on various combinations of home remedies. The highest average severity scores are found in categories "34" and "2345," each representing 14.3% of respondents. This suggests that individuals using these specific combinations of remedies experience more severe symptoms, indicating that these combinations may not effectively alleviate symptom severity. In contrast, moderate severity levels are observed in groups like category "0" (no home remedies), "3," and "35," with percentages of 12.9%, 8.6%, and 11.5%, respectively, implying a moderate impact on severity. The lowest average severity score is seen in category "1234," where only 5.7% of respondents report symptoms at this level. This suggests that using this specific combination of remedies might be associated with the least severe symptoms, indicating a potential benefit when certain remedies are used together. The overall variability in severity scores across different remedy combinations suggests that the effectiveness of home remedies may depend on the specific combination used. However, in some cases, combining multiple remedies does not appear to lower severity, and may even be associated with higher severity levels. The figure indicates that while certain combinations of home remedies may help reduce symptom severity, others do not provide significant relief and might correlate with higher severity. These findings highlight the need for further investigation into which specific remedies or combinations are most effective in managing symptoms.

The independent t-test was conducted to compare symptom severity scores between individuals who used home remedies and those who did not. The t-statistic of -1.122 indicates a slight, non-significant reduction in severity for those using home remedies, with a negative value suggesting that severity is marginally lower in this group. However, the p-value of 0.312 far exceeds the standard significance threshold of 0.05, indicating that this observed difference is not statistically significant. The analysis shows no statistically meaningful difference in average severity scores between individuals who used home remedies and those who did not. These results suggest that, the use of home remedies does not have a significant impact on symptom severity.

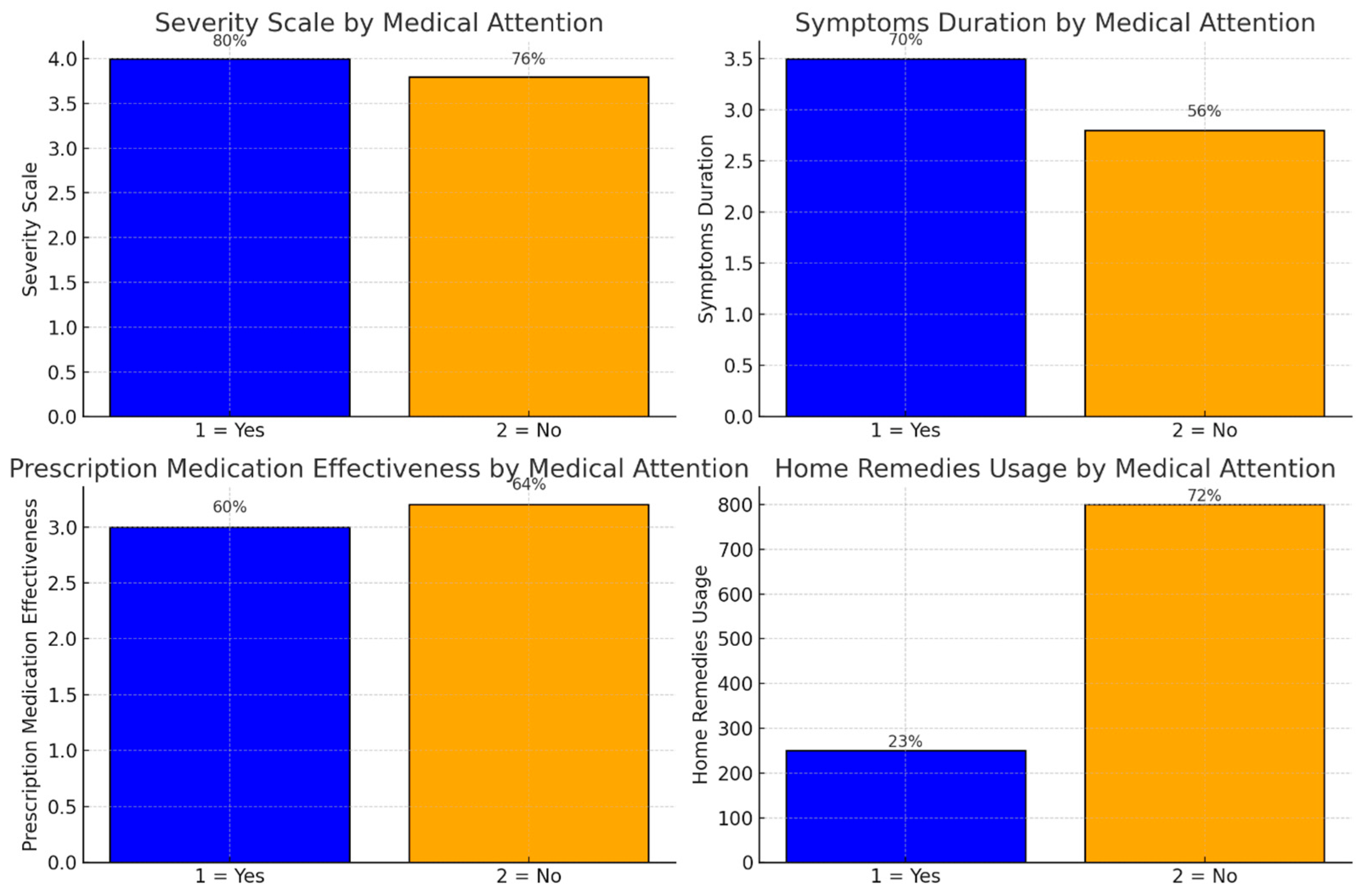

Figure 4 compares symptom outcomes for individuals who sought medical attention (Group 1) versus those who did not (Group 2) across four dimensions. First, on the severity scale, Group 2 (those who did not seek medical attention) reported slightly higher symptom severity, though the difference between the groups is minimal. Secondly, in terms of symptoms duration, individuals in Group 1 (those who sought medical attention) experienced longer durations of symptoms on average. Third, regarding prescription medication effectiveness, those who sought medical attention reported lower effectiveness of prescription medications compared to those in Group 2. Lastly, Home remedies usage was more frequent among individuals who did not seek medical attention (Group 2).

Figure 5, provide insights into various health metrics by comparing respondents who received medical attention (Yes) versus those who did not (No), with percentages on each bar adding context to the distribution of responses. Severity scale by medical attention: The average severity is slightly higher among those who sought medical attention (80%) compared to those who did not (76%). This indicates that individuals experiencing more severe symptoms may be more inclined to seek medical assistance. However, the minor difference suggests that medical attention is typically sought when symptoms are already severe, rather than directly impacting the severity level itself. Symptoms duration by medical attention: The average duration of symptoms is longer for those who received medical attention (70%) than for those who did not (56%). This trend implies that individuals with prolonged or persistent symptoms are more likely to consult healthcare professionals. It may also suggest that medical attention is often sought as a response to ongoing symptoms rather than as a quick remedy for symptom reduction. Prescription medication effectiveness by medical attention: prescription medications are rated as slightly more effective by those who did not seek medical attention (64%) compared to those who did (60%). This minor difference might indicate that individuals managing symptoms without professional care find medications relatively effective or may experience milder symptoms that do not necessitate medical intervention. It may also reflect a selection bias, where those with less severe symptoms self-manage and find prescribed medications sufficient. Home remedies usage by medical attention: usage of home remedies is notably higher among individuals who did not seek medical attention (72%) compared to those who did (23%). This suggests that people who manage symptoms independently may rely more on home remedies, likely due to mild symptoms, personal preferences, or convenience. Conversely, those who seek professional care tend to rely less on home-based treatments, possibly due to access to professional advice or greater symptom severity.

The logistic regression model aimed to predict whether respondents sought medical attention (1 = Yes, 0 = No) based on three health-related metrics: severity scale, symptoms duration, and home remedies used. The model's pseudo-R2 of 0.6243 suggests that it explains approximately 62% of the variability in medical attention-seeking behavior, indicating a reasonably good fit. Additionally, the LLR p-value of 0.038 confirms that the model is statistically significant at the 5% level, implying that these predictors collectively have some predictive power for determining medical attention-seeking. However, a convergence warning was observed, indicating that the model did not converge. This issue could be due to multicollinearity, limited data, or quasi-separation. In this case, quasi-separation is likely, meaning that certain observations are perfectly predicted, which can cause instability in coefficient estimates and reduce reliability. Examining the coefficient estimates, the severity scale has a positive coefficient of 4.017, suggesting that higher symptom severity is associated with a greater likelihood of seeking medical attention. However, this coefficient is not statistically significant, indicating variability in its predictive power. Both symptoms duration and home remedies used have large negative coefficients, but they are also not statistically significant, likely due to extreme variability and potential quasi-separation effects in the data. While the model indicates that severity is positively associated with seeking medical attention, the overall instability due to convergence issues and quasi-separation limits the reliability of these estimates.

To analyze factors influencing symptom severity and the likelihood of seeking medical attention, we employed both multivariate regression and logistic regression models, each yielding complementary insights. Multivariate Regression assessed symptom severity as a continuous outcome influenced by various predictors, including home remedies used, medical treatment used, and symptoms duration. The expanded model achieved an R2 of 0.766, indicating a strong explanatory power. Key findings included a positive association between medical treatment used and severity, suggesting that individuals with more severe symptoms are more likely to seek medical care. Conversely, prescription medication showed a slight negative association with severity, implying a potential symptom-reducing effect. Although interaction terms (e.g., home remedies × medical treatment) slightly improved the model's explanatory power, they did not reach statistical significance. Overall, the OLS model suggested that symptom severity is influenced by multiple factors, with medical care often sought in response to higher severity. Logistic Regression aimed to predict the binary outcome of seeking medical attention based on severity scale, symptoms duration, and home remedies usage. The model's pseudo R2 of 0.624 indicated moderate explanatory power for predicting medical attention. Severity scale had a positive coefficient, confirming that higher severity increases the likelihood of seeking medical care.

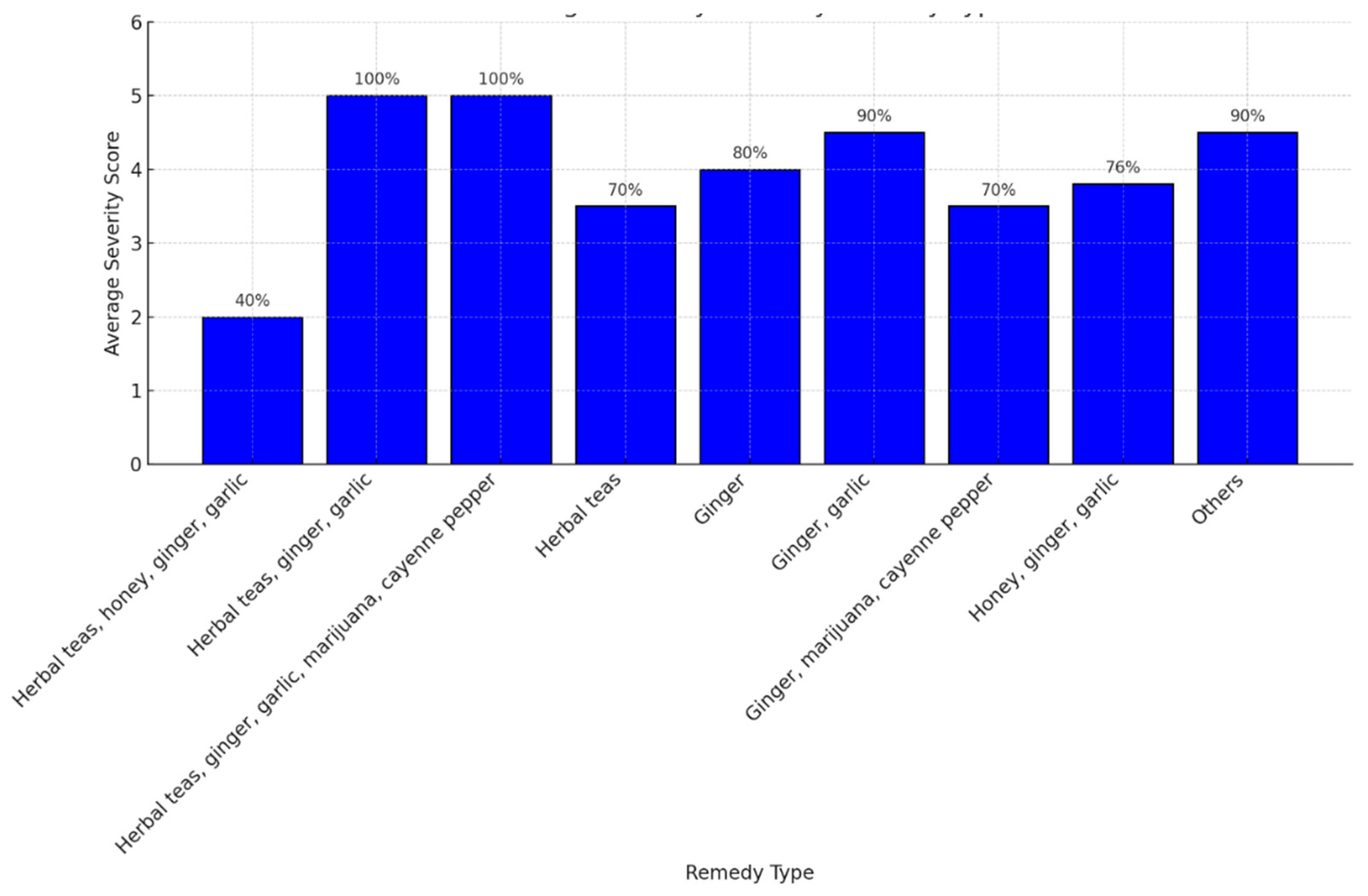

In

Figure 6, highest severity scores (5.0), remedies such as "herbal teas, ginger, garlic, marijuana, cayenne pepper" are associated with the highest severity scores. This suggests that these combinations may either be selected in response to particularly severe symptoms or may have limited effectiveness in reducing severity. The presence of combinations with 100% severity labels underscores their strong association with the most severe symptoms. Moderate severity Scores (3.5 - 4.5), remedies like "herbal teas" (70%) and "ginger, garlic" (90%) are linked with moderately high severity scores. These remedies may provide some symptom relief but are still associated with substantial symptom severity, suggesting that while they may be somewhat effective, they are typically used by individuals experiencing moderate symptom burdens. Lowest severity score (2.0), the combination of "herbal teas, honey, ginger, garlic" (40%) has the lowest severity score in the dataset. This combination might be more effective in alleviating symptoms or may be more commonly used by individuals with milder symptoms, indicating a potential role in reducing symptom severity. General trends, the percentages associated with each remedy combination provide insights into their prevalence and potential effectiveness. Lower percentages and severity scores may indicate better symptom relief, while higher percentages and severity scores suggest that these remedies are either less effective or are used in response to more severe symptoms. Ou study suggest that certain combinations of home remedies, such as herbal teas with honey, ginger, and garlic, may be associated with lower symptom severity, while others, like herbal teas, ginger, garlic, marijuana, and cayenne pepper, are linked to the highest severity levels, potentially reflecting either limited effectiveness or use in severe cases.

The multivariate regression model, which includes interaction terms to explore combined effects of different treatment types on symptom severity, revealed insights into the relationships between home remedies, medical treatment, and prescription medication. Model Fit and Explanatory Power has an R2 of 0.930, suggesting it explains 93% of the variability in symptom severity, indicating a strong fit. Additionally, the F-statistic p-value of 0.224 indicates that the overall model is not statistically significant, suggesting that these predictors and interactions do not collectively provide a statistically robust prediction of severity.

Individual treatment effects, home remedies used had the coefficient of 0.3167 (p = 0.683) that shows a positive but non-significant association with severity, indicating that home remedies alone may have a slight, though inconclusive, effect on increasing severity. Medical treatment used has the coefficient of 0.9167 (p = 0.304) suggesting a larger positive effect, implying that individuals with more severe symptoms are more likely to seek medical treatment, though this relationship is not statistically significant. Prescription medication used have a coefficient of -0.6333 (p = 0.462), prescription medication shows a slight, non-significant tendency to reduce symptom severity, indicating a potential but weak effect on alleviating symptoms.

Interaction effects, home remedies and medical treatment interaction has a coefficient of -0.6667 (p = 0.358), suggesting a possible reduction in severity when both home remedies and medical treatment are used together, though this effect is not statistically significant. Home remedies and prescription medication has the coefficient of 0.3667 (p = 0.582) indicating a minimal and non-significant effect when home remedies and prescription medication are combined, showing limited interaction between these treatments. Medical treatment and prescription medication have a coefficient of -0.1000 (p = 0.863), this interaction shows a negligible and non-significant effect, suggesting that using medical treatment and prescription medication together does not significantly impact symptom severity.

This model suggests that while certain treatment types (e.g., medical treatment and prescription medication) show weak individual associations with symptom severity, none of these effects are statistically significant, and the interactions do not reveal meaningful combined impacts on severity. The high R

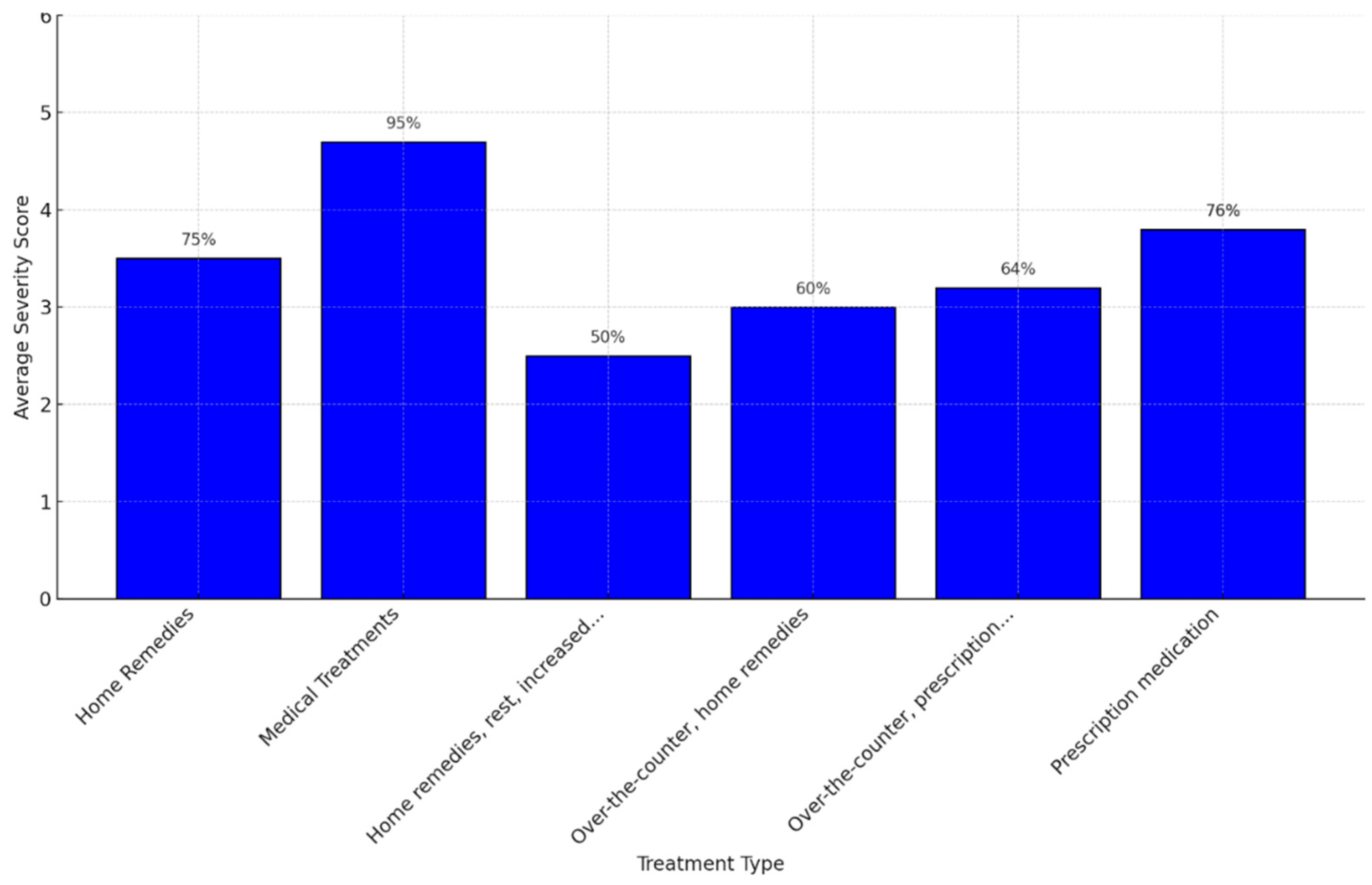

2 value indicates that the model accounts for much of the variability in severity, yet the lack of statistical significance highlights the limitations of these predictors and interactions in providing reliable insights within this study. The analysis of symptom severity scores across different treatment types reveals distinct patterns in the relationship between treatment choice and severity level. Highest severity (4.7), medical treatments are associated with the highest severity score, with 95% of respondents with severe symptoms opting for professional medical care. This likely indicates that individuals experiencing the most intense symptoms are more inclined to seek formal medical intervention. Moderate severity (3.0 - 3.8), home remedies (75%), prescription medication (76%), and a combination of over-the-counter and prescription medications (64%) are linked to moderate severity scores. These treatments appear to offer some symptom relief, making them suitable for managing moderate cases, though the severity scores suggest that their effectiveness may vary depending on individual factors. Lowest severity (2.5), a combination of home remedies, rest, and increased hydration or nutrition (50%) is associated with the lowest severity score. This suggests that such a combination may be effective for managing milder symptoms, possibly due to its holistic approach to symptom relief (

Figure 7).

The OLS regression model evaluated the impact of home remedies used and medical treatment used on symptom severity, revealing important insights into the relationship between these variables and severity levels. For the Model Fit, the model has an R2 of 0.520, explaining 52% of the variability in symptom severity. This indicates a moderate fit, suggesting that the predictors provide some explanatory power. The F-statistic p-value of 0.0764 is close to the significance threshold (0.05), indicating that the predictors are jointly somewhat predictive of symptom severity.

The key coefficients observed included intercept with a value of 3.38 (p < 0.001), the intercept represents the baseline severity score when neither home remedies nor medical treatment are used. Home remedies used had the coefficient of 0.333 (p = 0.251) indicates a small positive but statistically insignificant effect of home remedies on severity. This suggests that using home remedies does not consistently affect symptom severity in this model. Medical treatment used had the coefficient of 0.640 (p = 0.044) indicates a statistically significant positive effect of medical treatment on severity. This implies that individuals with higher symptom severity are more likely to seek medical attention, rather than medical treatment itself increasing severity.

The statistical analysis revealed a p-value of 0.025, which is below the conventional significance threshold of 0.05. This indicates a statistically significant difference in the average symptom severity between the least severe management strategies and the other approaches. Consequently, the results suggest that management techniques associated with the lowest severity scores, such as home remedies, rest, and increased fluid intake, are more effective at alleviating symptoms and reducing their severity compared to other methods.

Moreover, results highlight that medical treatment usage is a significant predictor of symptom severity, likely reflecting that individuals with more severe symptoms are more inclined to seek professional care. In contrast, home remedies do not exhibit a statistically significant effect on severity, suggesting they may be used across a broad range of symptom severities without a consistent impact on the severity score. This analysis underscores the role of medical treatment in addressing higher severity cases, while home remedies appear to be a supplementary or alternative approach that does not strongly correlate with severity levels.

Treatment patterns, the percentages associated with each treatment provide a visual indication of relative symptom severity, with higher percentages linked to more severe cases and lower percentages associated with milder symptoms. This trend suggests that more severe cases are more likely to prompt individuals to seek professional medical treatment, while milder cases are often managed with home remedies and rest. The data suggest that professional medical treatment is commonly associated with severe symptoms, while home-based treatments and rest are more prevalent for milder cases. This pattern highlights a general tendency for individuals to scale their treatment choices based on symptom severity.

The expanded multivariate regression model explores the relationship between symptom severity and additional predictors, including home remedies used, medical treatment used, symptoms duration, and prescription medication used. This model demonstrates improved explanatory power compared to prior analyses but highlights limitations in individual predictor significance. In Model Fit the model’s R2 of 0.766 indicates that it explains 76.6% of the variability in symptom severity, a substantial improvement over earlier models. However, the F-statistic p-value of 0.0776 suggests that, while the predictors collectively provide some predictive value, the model does not reach the 0.05 significance threshold, potentially reflecting sample size or variability constraints.

Key coefficients observed included the intercept with a value of 3.89 (p < 0.002), the intercept represents the baseline severity when none of the predictors are active (e.g., no remedies, treatments, or medications used). Home remedies used with coefficient of 0.1924 (p = 0.444) indicates a small, non-significant positive effect, suggesting that home remedies do not strongly influence severity in this dataset. Medical treatment used had the coefficient of 0.4160 (p = 0.159) suggests a positive effect, where individuals with higher severity are more likely to seek medical care, though this relationship is not statistically significant. Symptoms duration had a coefficient of 0.0076 (p = 0.953), symptoms duration shows no notable or significant effect on severity, suggesting variability that does not correlate directly with severity in this model. Prescription medication used had the coefficient of -0.5639 (p = 0.109) indicates a negative, non-significant effect, implying that prescription medications may slightly reduce severity, though the effect is not statistically robust.

The inclusion of additional predictors improved the model’s ability to explain variability in symptom severity, as reflected by the high R2 value. However, none of the individual predictors achieve statistical significance, indicating that their relationships with severity may be influenced by sample size, variability, or complex interactions not captured by this model. Medical treatment and prescription medication exhibit trends in expected directions—higher severity prompting more treatment and medications potentially reducing severity—but these effects remain inconclusive in this dataset. Meanwhile, symptoms duration shows no notable impact, possibly suggesting a more complex or non-linear relationship with severity.

This multivariate regression model, incorporating interaction terms to examine the combined effects of different treatments on symptom severity, provides high explanatory power but limited statistical significance for individual predictors and interactions. In Model Fit, the model’s R2 of 0.930 indicates that it explains 93% of the variability in symptom severity, reflecting strong explanatory potential. However, the F-statistic p-value of 0.224 suggests that the predictors and interactions collectively do not achieve statistical significance at the 0.05 level, warranting caution in interpreting the results.

Main Effects, Home remedies used had the coefficient of 0.3167 (p = 0.683) suggests a positive but non-significant effect on severity, consistent with prior analyses indicating a limited impact of home remedies on symptom severity. Medical treatment used had a coefficient of 0.9167 (p = 0.304), medical treatment shows a larger positive effect on severity, indicating that individuals with higher severity are more likely to seek medical care. However, this effect remains statistically insignificant. Prescription medication used had the coefficient of -0.6333 (p = 0.462) suggests a slight, non-significant reduction in severity, indicating that prescription medications may help reduce symptoms, though the effect is not strong in this dataset.

Interaction Effects, home remedies × medical treatment had a coefficient of -0.6667 (p = 0.358) suggests a potential reduction in severity when both treatments are combined, though this effect is not statistically significant. Home remedies × prescription medication had coefficient of 0.3667 (p = 0.582) indicates a minimal and non-significant positive interaction, implying a weak or negligible combined effect. Medical treatment × prescription medication had a coefficient of -0.1000 (p = 0.863), the interaction between medical treatment and prescription medication shows a negligible and non-significant effect.

The model demonstrates high explanatory power, explaining a substantial portion of symptom severity variability, but none of the individual predictors or interactions achieve statistical significance. This suggests that while the relationships between these treatments and severity align with expected trends—such as higher severity prompting medical care or prescription medication slightly reducing severity—these effects are not definitive within this study. Interaction terms reveal no statistically strong combined impacts, though some directional patterns (e.g., a negative interaction between home remedies and medical care) merit further exploration with a larger sample.

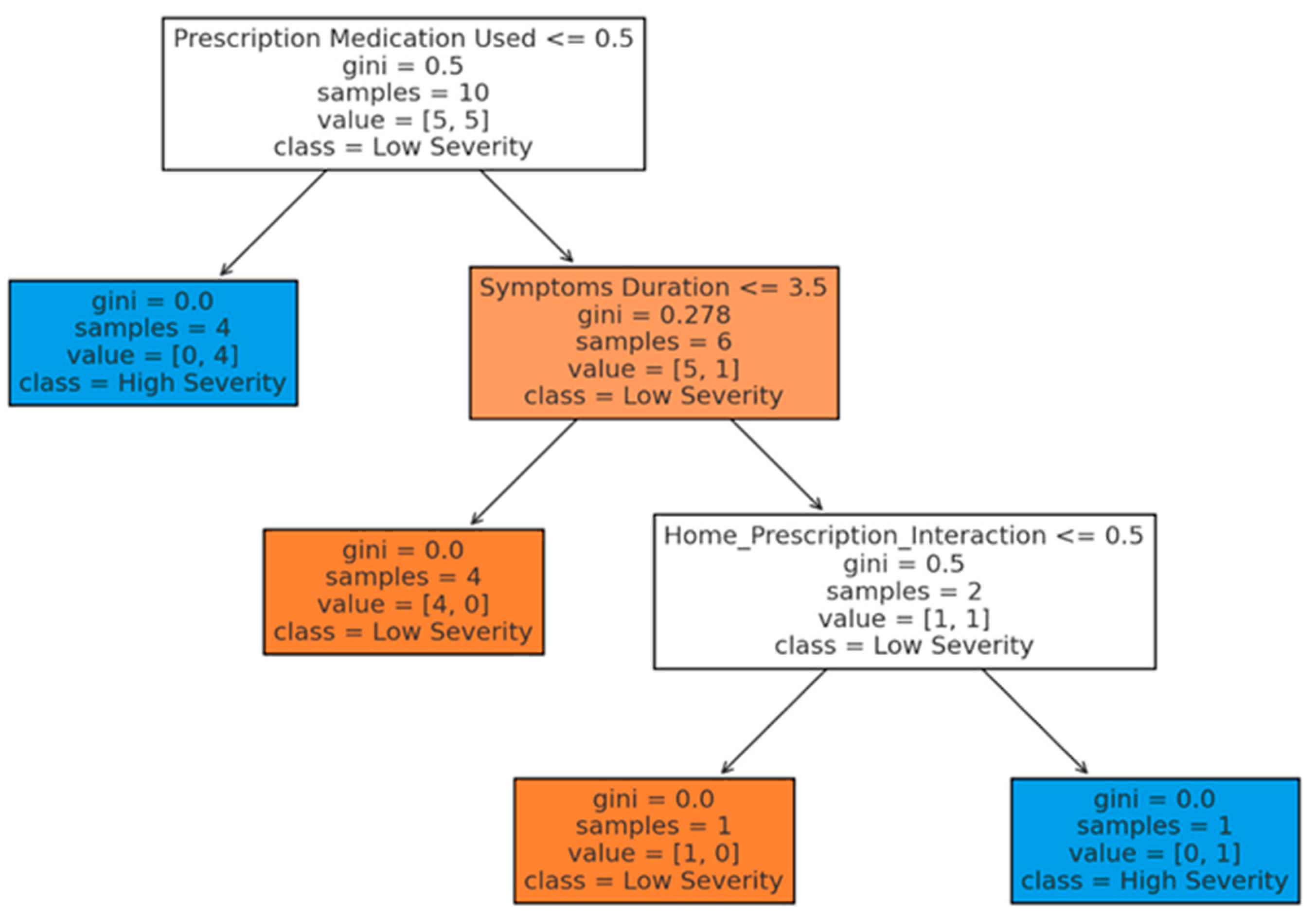

The decision tree analysis in

Figure 8 provides a structured, visual representation of how specific health-related factors and their interactions predict whether symptom severity is classified as high or low. The model’s key decision points highlight the influence of prescription medication usage and symptoms duration, along with interactions involving home remedies. Root Node (prescription medication used) shows the initial split in the tree is based on whether prescription medication was used. If prescription medication was not used (<= 0.5), the model predicts high severity for these cases, indicating that individuals without prescription treatment are more likely to experience severe symptoms. For cases where prescription medication was used, the next split is determined by symptoms duration. If the duration is less than or equal to 3.5 days, the model predicts low severity, suggesting that shorter symptom durations, when coupled with prescription medication, are associated with lower symptom severity. Home_prescription_interaction, the cases where symptoms last more than 3.5 days, the model examines the interaction between home remedies and prescription medication as the next decision point. Depending on the value of this interaction, the model continues to split, ultimately predicting high or low severity based on combined effects, though this interaction provides limited predictive power in this dataset.