Submitted:

02 October 2024

Posted:

03 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experiments

2.1. Materials and Preparations

3. Experimental Design and Method

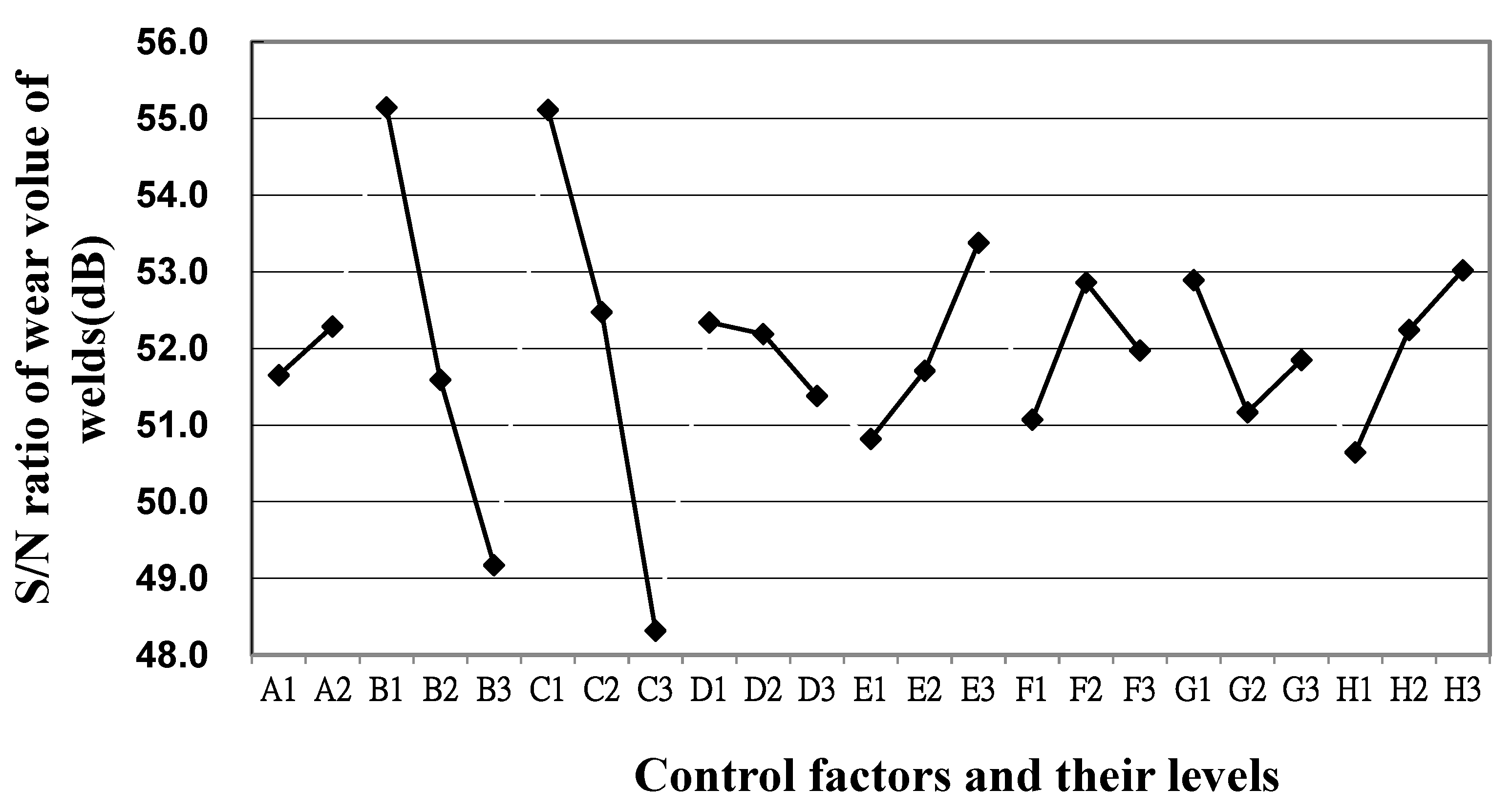

3.1. Experimental Design Based on Orthogonal Array

3.2. Analysis of Variance

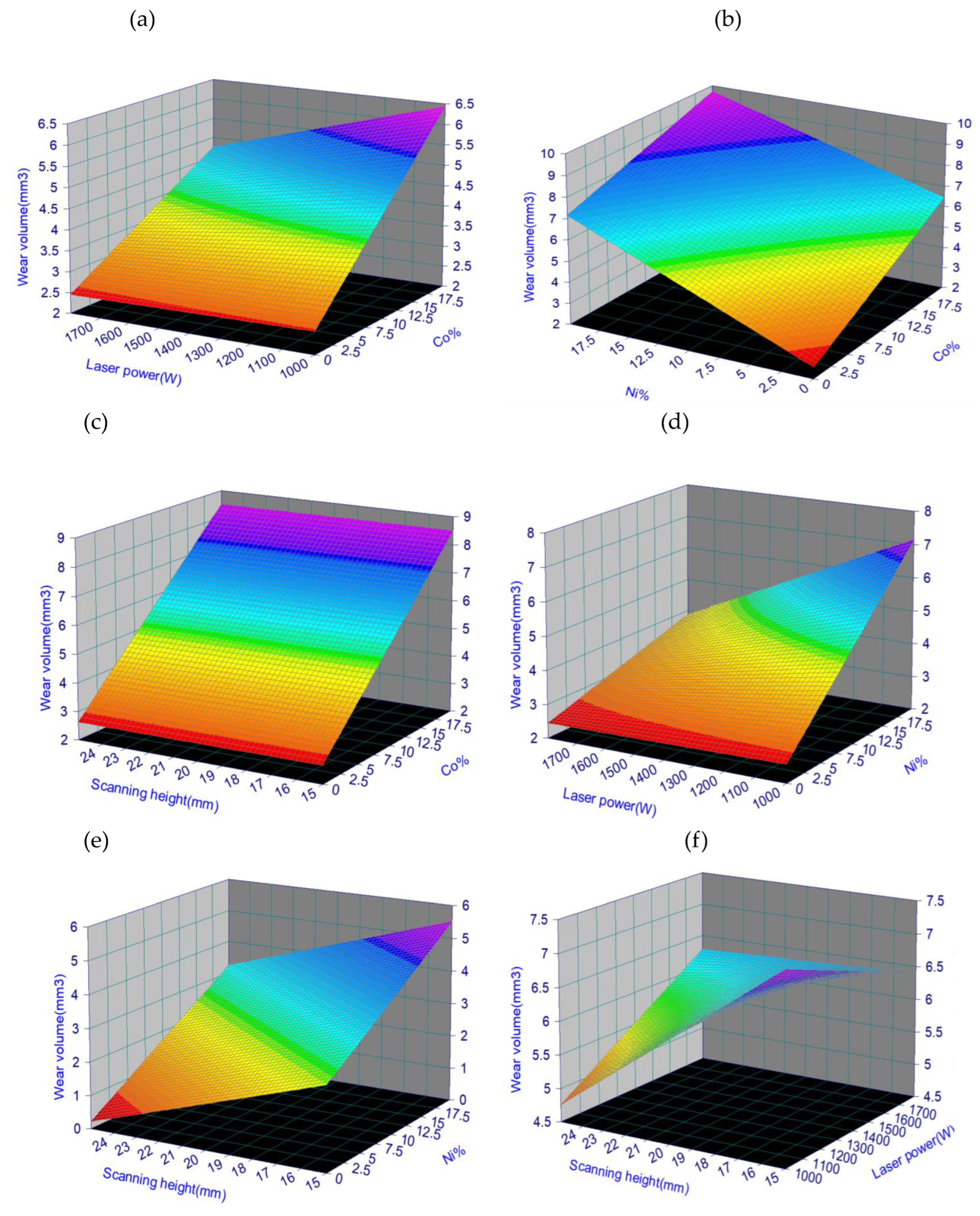

3.3. Response Surface Analysis

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

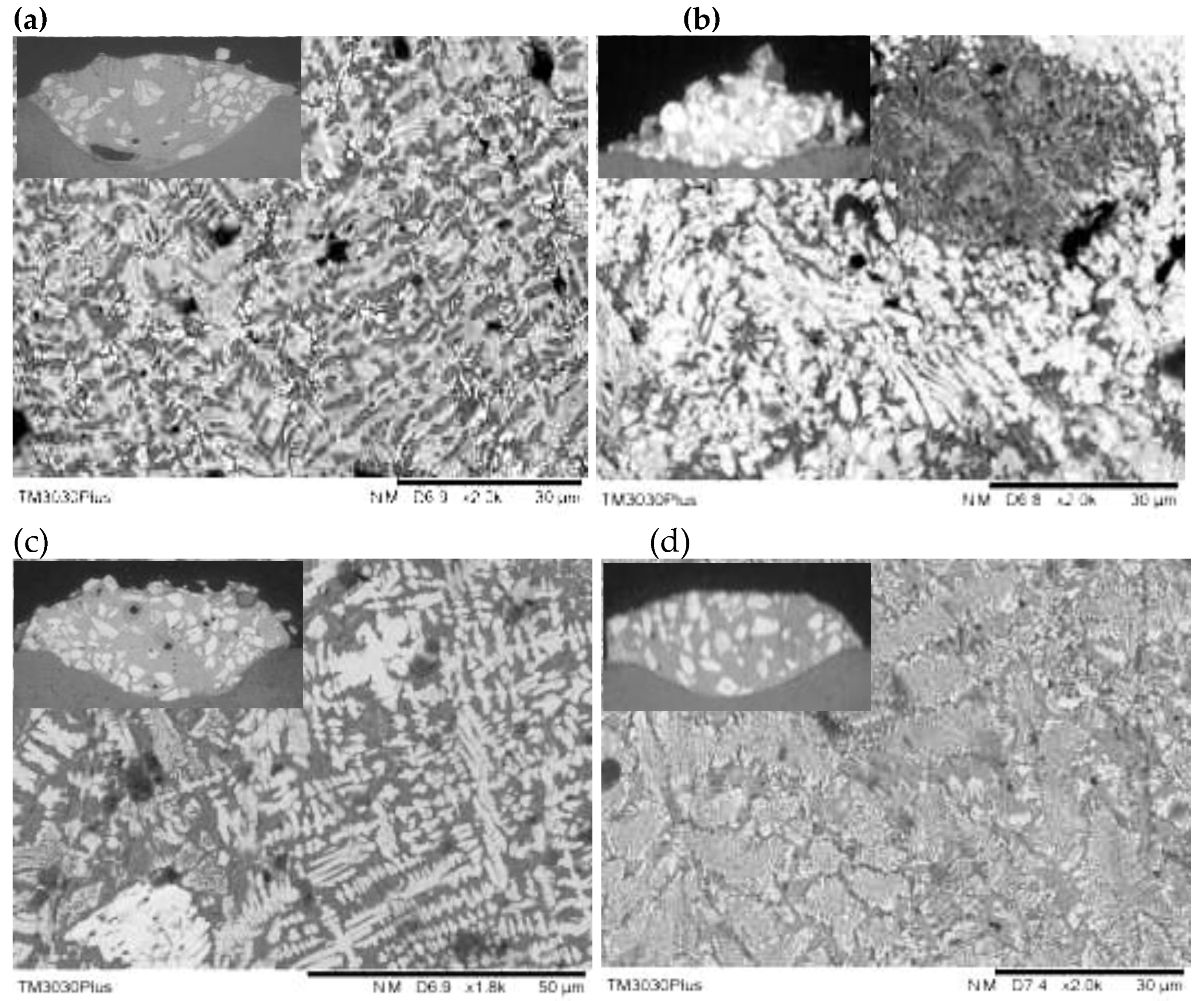

4.1. Microstructure of the Cladding Zone of WC/Co/Ni Welds

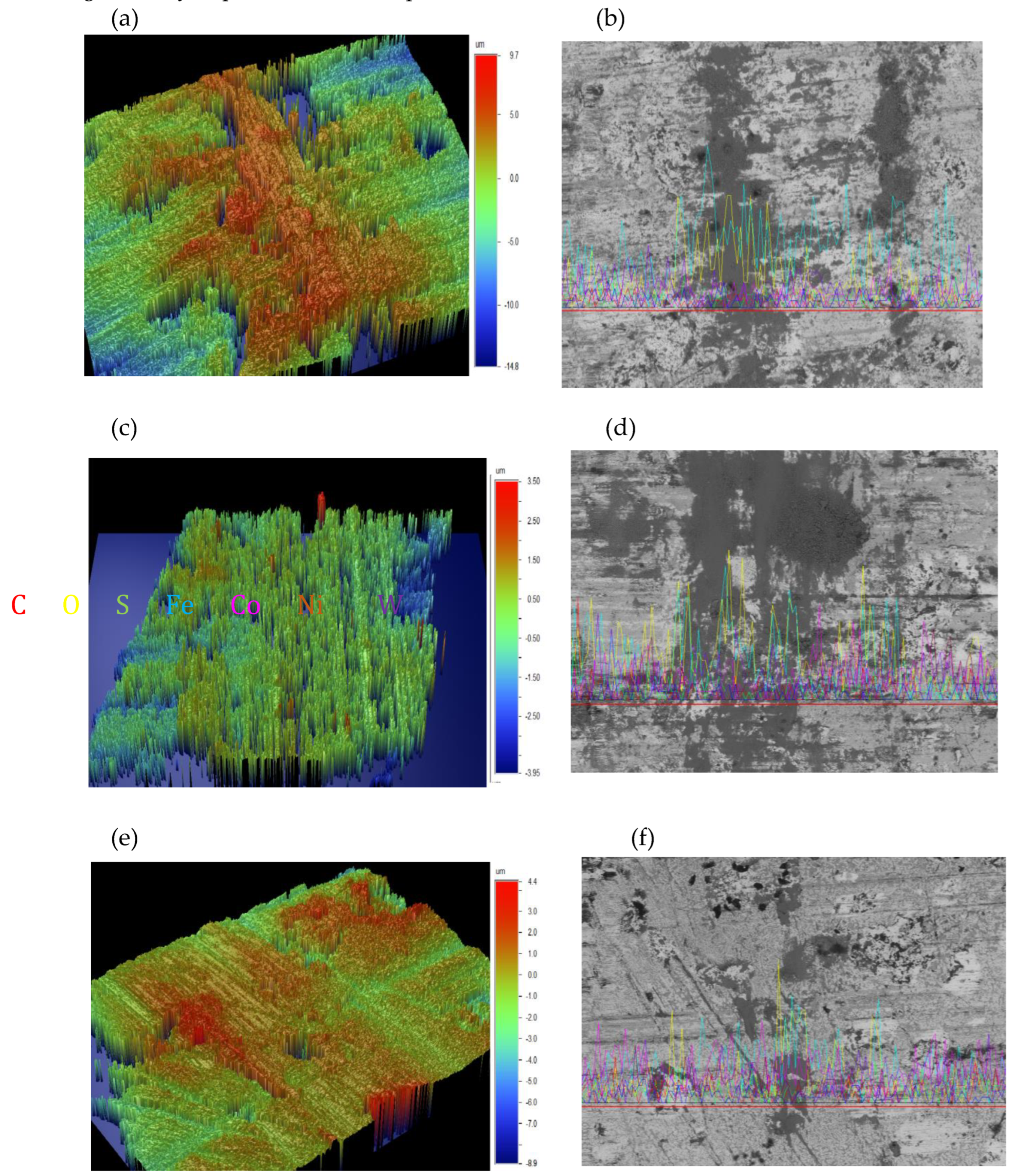

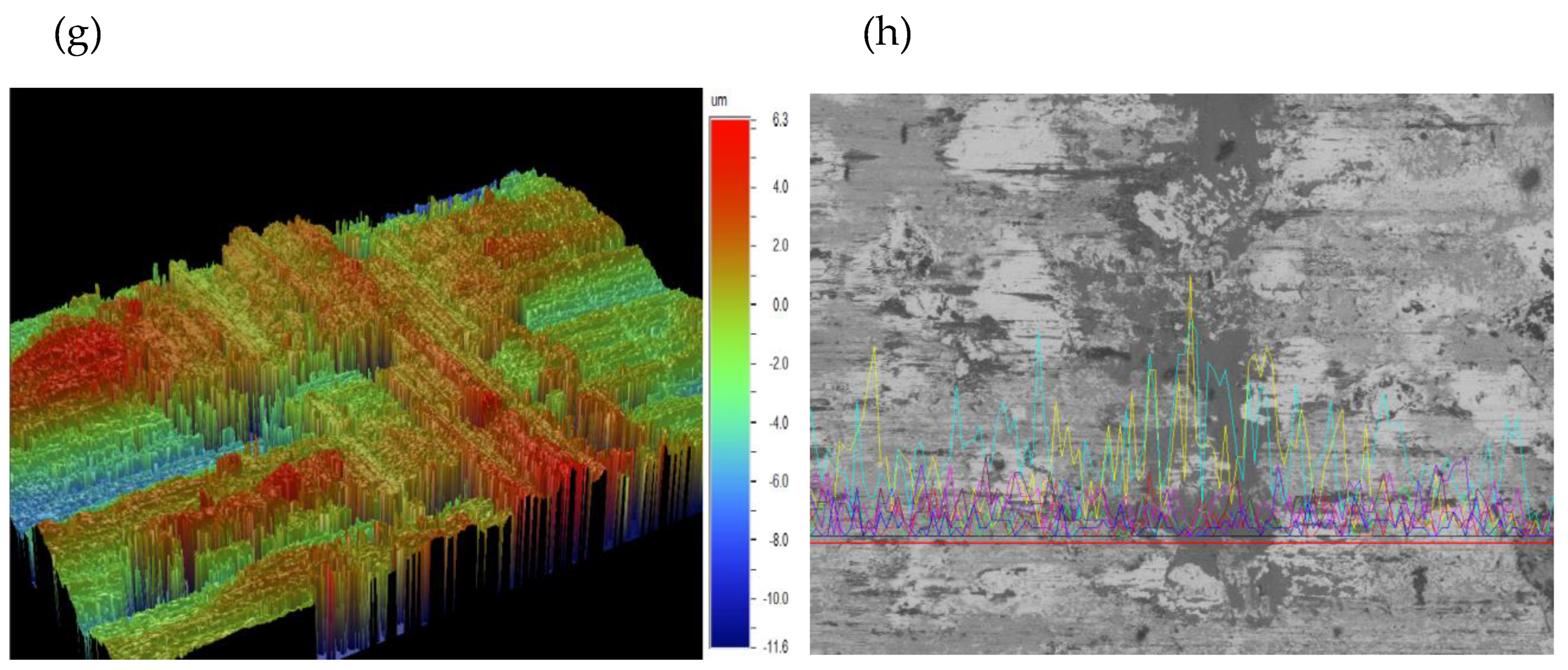

4.2. Wear Properties of Co/Ni Mixed WC Welds

4.3. Effect of Cobalt/Nickel Additive Blends on WC Welds

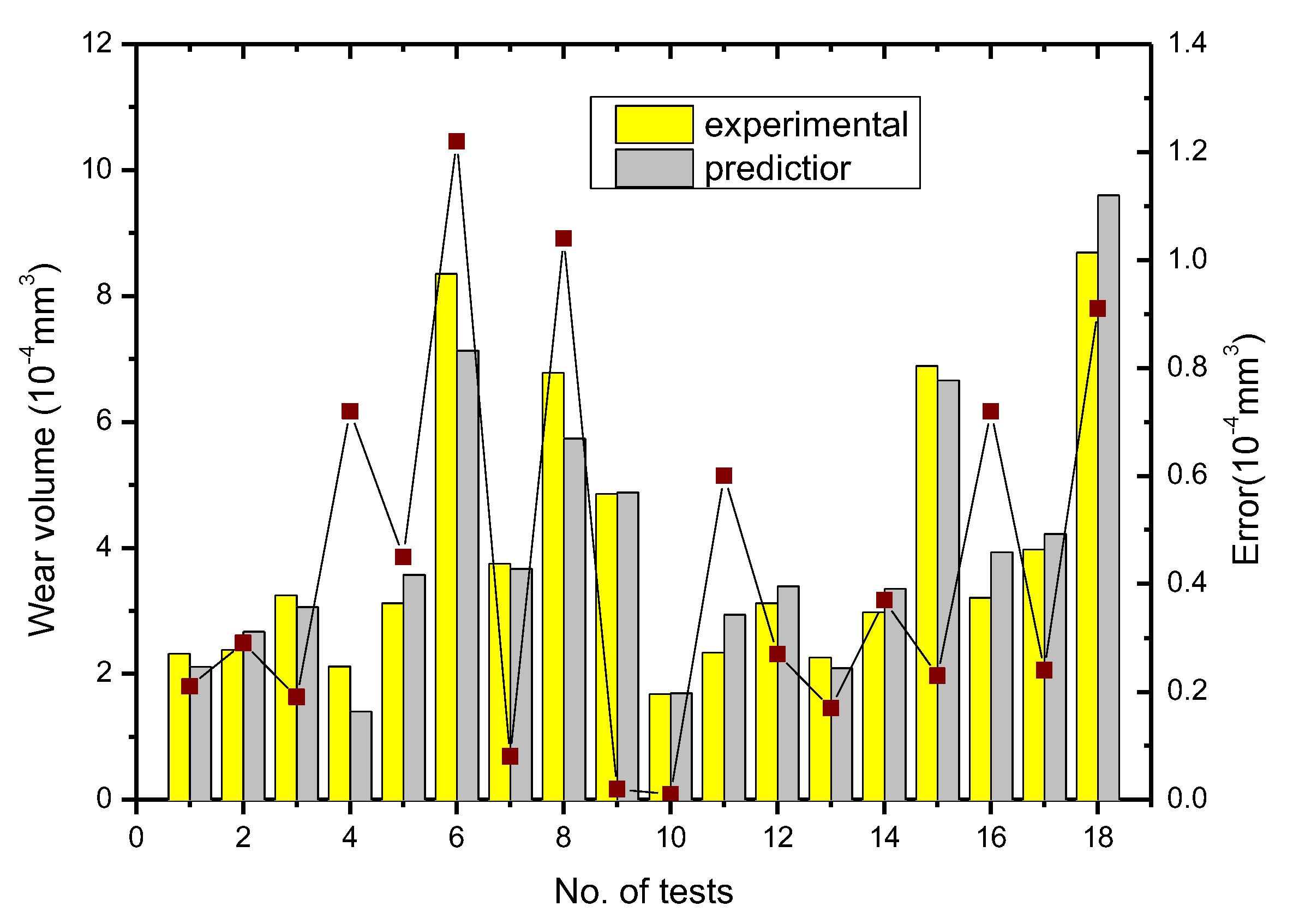

4.4. Empirical Model Analysis

4.5. Empirical Model Analysis

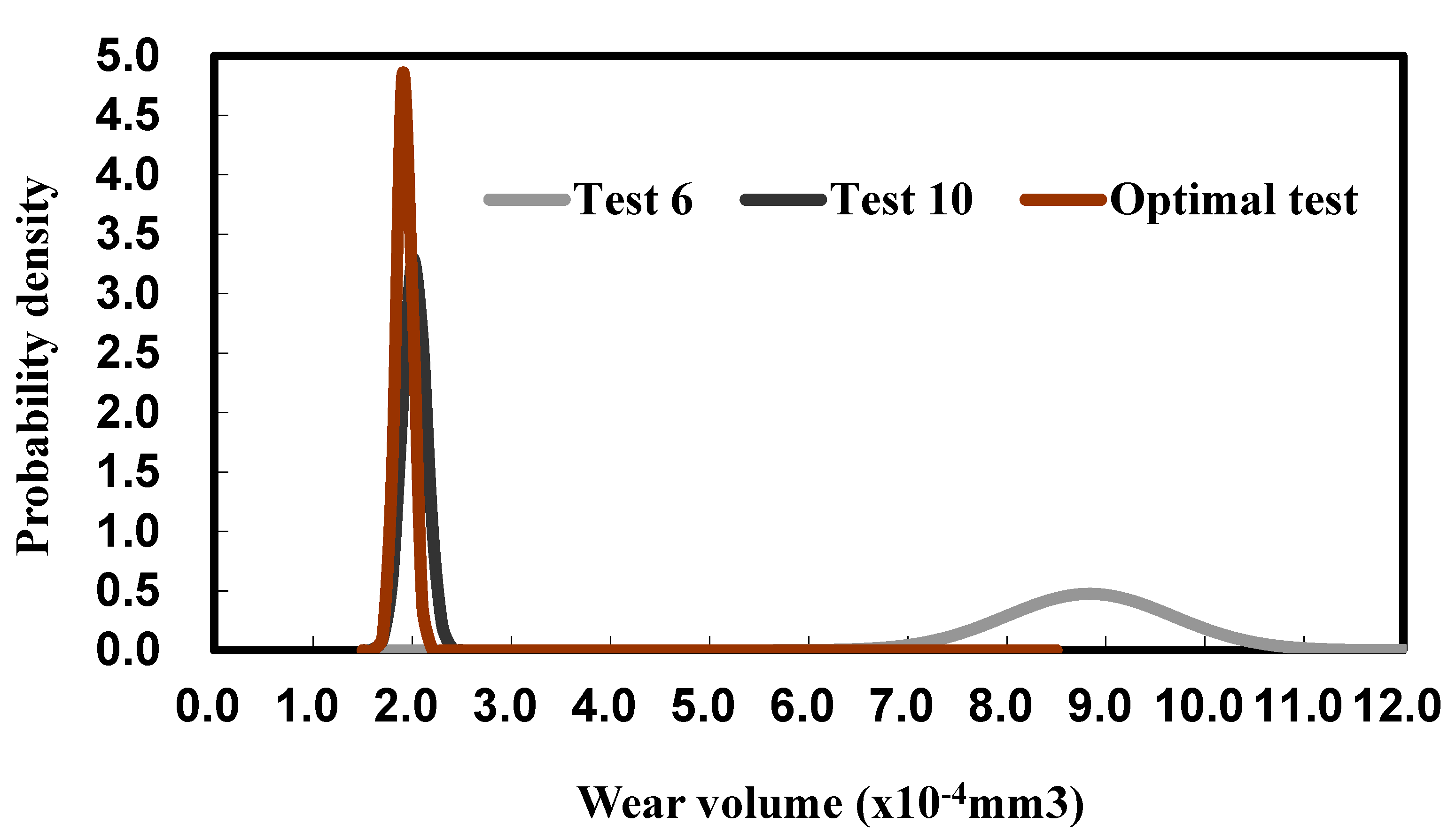

4.6. Confirmation Experiments

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suryanarayanan, R. (1993). Plasma spraying: theory and applications. World scientific.

- Sun G, Zhou R, Lu J, et al. (2015). Evaluation of defect density, microstructure, residual stress, elastic modulus, hardness and strength of laser-deposited AISI 4340 steel. Acta Materialia, 84: 172-189. [CrossRef]

- S.Zhou,X.Dai,(2010)Laser induction hybrid rapid cladding of WC particles reinforced NiCrBSi composite coatings, Appl. Surf. Sci. 256,4708-4714.

- Afzal M, Ajmal M, Khan A N, et al. (2014). Surface modification of air plasma spraying WC–12% Co cermet coating by laser melting technique. Optics & Laser Technology, 56: 202-206. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Lei T, Bao Q, et al. (2002). Problems and the improving measures in laser remelting of plasma sprayed ceramic coatings. Material Science & Technology, 10(4): 431-435.

- Wen P, Feng Z, Zheng S. (2015). Formation quality optimization of laser hot wire cladding for repairing martensite precipitation hardening stainless steel. Optics & Laser Technology, 65: 180-188. [CrossRef]

- Afzal M, Khan A N, Mahmud T B, et al. (2015). Effect of laser melting on plasma sprayed WC-12 wt.% Co coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology, 266: 22-30.

- Zhang J, Lei J, Gu Z, et al. (2020). Effect of WC-12Co content on wear and electrochemical corrosion properties of Ni-Cu/WC-12Co composite coatings deposited by laser cladding. Surface and Coatings Technology, 393: 125807. [CrossRef]

- Tehrani H M, Shoja-Razavi R, Erfanmanesh M, et al. (2020). Evaluation of the mechanical properties of WC-Ni composite coating on an AISI 321 steel substrate. Optics & Laser Technology, 127: 106138. [CrossRef]

- Hao E, Zhao X, An Y, et al. (2019). WC-Co reinforced NiCoCrAlYTa composite coating: Effect of the proportion on microstructure and tribological properties. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials, 84: 104978. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi T, Hagino H. (2021). Effects of the ambient oxygen concentration on WC-12Co cermet coatings fabricated by laser cladding. Optics & Laser Technology, 139: 106922. [CrossRef]

- Da Shu, Zhuguo Li, Ke Zhang, Chengwu Yao, Dayong Li, Zhenbang Dai. (2010). In situ synthesized high volume fraction WC reinforced Ni-based coating by laser cladding. Materials Letters 195 (2017) 178–181. [CrossRef]

- Richter J, Harabas K. (2019). Micro-abrasion investigations of conventional and experimental supercoarse WC-(Ni, Co, Mo) composites. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials, 83: 104986. [CrossRef]

- Cao Q, Fan L, Chen H, et al. (2022). Wear behavior of laser cladded WC-reinforced Ni-based coatings under low temperature. Tribology International, 176: 107939. [CrossRef]

- Paul C P, Alemohammad H, Toyserkani E, et al. (2007). Cladding of WC–12 Co on low carbon steel using a pulsed Nd: YAG laser. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 464(1-2): 170-176. [CrossRef]

- P.H. Chong, H.C. P.H. Chong, H.C. Man, T.M. Yue, Microstructure and wear properties of laser surface-cladded Mo–WC MMC on AA6061 aluminum alloy, Surf. Coat. Technol. 145 (1) (2001) 51–59. [CrossRef]

- P. Wu, H.M. P. Wu, H.M. Du, X.L. Chen, Z.Q. Li, H.L. Bai, E.Y. Jiang, Influence of WC particlebehavior on the wear resistance properties of Ni-WC composite coatings,Wear 257 (1-2) (2004) 142-147.

- Anjani Kumar, Anil Kumar Das. Evolution of microstructure and mechanical properties of Co-SiC tungsten inert gas cladded coating on 304 stainless steel. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, 24(3), 2021, P 591-604.

- Jiandong Wang, Liqun Li, Wang Tao. Crack initiation and propagation behavior of WC particles reinforced Fe-based metal matrix composite produced by laser melting deposition.Optics & Laser Technology 82 (2016) 170-182. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhou, X. Zeng, Q. Hu, et al., Analysis of crack behavior for Ni-based WC composite coatings by laser cladding and crack-free realization, Appl. Surf. Sci. 255 (2008) 1646-1653. [CrossRef]

- P. Farahmand, R. P. Farahmand, R. Kovacevic, Laser cladding assisted with an induction heater (LCAIH) of Ni-60%WC, Coat. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 222 (2015) 244-258.

- C.P. Paul, H. C.P. Paul, H. Alemohammad, E. Toyserkani, A. Khajepour, S. Corbin.Cladding of WC-12 Co on low carbon steel using a pulsed Nd:YAG laser.Materials Science and Engineering A 464 (2007) 170–176. [CrossRef]

- Shengfeng Zhou, Yongjun Huang, Xiaoyan Zeng. A study of Ni-based WC composite coatings by laser induction hybrid rapid cladding with elliptical spot. Applied Surface Science 254 (2008) 3110-3119. [CrossRef]

- F. Kretz, Z. F. Kretz, Z. Gácsi, J. Kovács, T. Pieczonka. The electroless deposition of nickel on SiC particles for aluminum matrix composites. Surf. Coat. Technol., 180-181 (2004), pp. 575-579.

- Sunny Zafar, Apurbba Kumar Sharma.Investigations on flexural performance and residual stresses in nanometric WC-12Co microwave clads. Surface & Coatings Technology 291 (2016) 413-422. [CrossRef]

- S.F. Zhou, J.B. S.F. Zhou, J.B. Lei, X.Q. Dai, J.B. Guo, Z.J. Gu, H.B. Pan. A comparative study of the structure and wear resistance of NiCrBSi/50 wt.% WC composite coatings by laser cladding and laser induction hybrid cladding. Int. Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 60 (2016) 17–27. [CrossRef]

- Da Shu, Zhuguo Li, Ke Zhang, Chengwu Yao, Dayong Li, Zhenbang Dai. In situ synthesized high volume fraction WC reinforced Ni-based coating by laser cladding.Materials Letters 195 (2017) 178–181. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhou, Y. Huang, X. Zeng, A study of Ni-based WC composite coatings by laserinduction hybrid rapid cladding with elliptical spot, Appl. Surf. Sci. 254 (10)(2008) 3110–3119.

- Shu D, Li Z, Zhang K, et al. (2017). In situ synthesized high volume fraction WC reinforced Ni-based coating by laser cladding. Materials Letters, 195: 178-181. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Lei J, Gu Z, et al. (2020). Effect of WC-12Co content on wear and electrochemical corrosion properties of Ni-Cu/WC-12Co composite coatings deposited by laser cladding. Surface and Coatings Technology, 393: 125807. [CrossRef]

- Zhong M, Liu W, Yao K, et al. (2002). Microstructural evolution in high power laser cladding of Stellite 6+WC layers. Surface and Coatings Technology, 157(2-3): 128-137. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhou, X. S. Zhou, X. Dai, H. Zheng, Microstructure and wear resistance of Fe-based WCcoating by multi-track overlapping laser induction hybrid rapid cladding, Opt.Laser Technol. 44 (1) (2012) 190–197.

- Wang Y, Li Y, Han K, et al. (2020). Microstructure and mechanical properties of sol-enhanced nanostructured Ni–Al2O3 composite coatings and the applications in WC-Co/steel joints under ultrasound. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 775: 138977. [CrossRef]

- P. Wu, H.M. P. Wu, H.M. Du, X.L. Chen, Z.Q. Li, H.L. Bai, E.Y. Jiang, Influence of WC particle behavior on the wear resistance properties of Ni-WC composite coatings,Wear 257 (1-2) (2004) 142-147. [CrossRef]

- A. Noviyanto et al. Metal oxide additives for the sintering of silicon carbide: reactivity and densification. Current Applied Physics. 13(1) 2013, 287-292. [CrossRef]

- S.P. Lee et al. Fabrication of liquid phase sintered SiC materials and their characterization.Fusion Engineering and Design. 81( 8-14) 2006, Pages 963-967. [CrossRef]

- Neng Li;Yi Xiong;Huaping Xiong;Gongqi Shi;Jon Blackburn;Wei Liu; Renyao Qin. Microstructure, formation mechanism and property characterization of Ti+SiC laser cladded coatings on Ti6Al4V alloy. Materials Characterization. 2019, 148,43-51. [CrossRef]

- S.Xu,et al., Microstructure and sliding wear resistance of laser cladded WC/Ni composite coatings with different contents of WC particle, J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 21,(2012) 1904-1911.

- Farahmand P, Kovacevic R. (2015). Laser cladding assisted with an induction heater (LCAIH) of Ni–60% WC coating. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 222: 244-258. [CrossRef]

- Luo W, Selvadurai U, Tillmann W. (2016). Effect of residual stress on the wear resistance of thermal spray coatings. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology, 25(1): 321-330. [CrossRef]

- Zoei M S, Sadeghi M H, Salehi M. (2016). Effect of grinding parameters on the wear resistance and residual stress of HVOF-deposited WC-10Co-4Cr coating. Surface and Coatings Technology, 307: 886-891. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. W., Wu, A.,(2000). Taguchi method for Robust Design, The American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 97-177.

- Myers, R. H., Montgomery, D.C.,(2006.). Response surface methodology: Process and product optimization using design experiments, John-Wiley & Sons, USA.

- Lin, B.T. , Jean,M.D., Chou,J.H., 2007. Using response surface methodology for optimizing deposited partially stabilized zirconia in plasma spraying. Applied Surface Science 253,3254–32. [CrossRef]

- Guilemany J M, Dosta S, Miguel J R. (2006). The enhancement of the properties of WC-Co HVOF coatings through the use of nanostructured and microstructured feedstock powders. Surface and Coatings Technology, 201(3-4): 1180-1190. [CrossRef]

- Long J, Zhang W, Wang Y, et al. (2017). A new type of WC-Co-Ni-Al cemented carbide: Grain size and morphology of γ ́-strengthened composite binder phase. Scripta Materialia, 126: 33-36. [CrossRef]

- C.Y. Zhang, S.Y. Chen , L.G. Xie , Echo Yang , Tong Bu , Ivan Cheung , M.D. Jean. Multi-objective Optimization of Laser Welds with Mixed WC/Co/Ni Experiments Using Simplex-centroid Design. Materials science 29(4):2023.445-455.

- C. W. Liu, M. D. Jean,1 Q. T. Wang, and B. S. Chen. Optimization of residual stresses in laser-mixed WC (Co, Ni) coatings. Strength of Materials, 51(1), 2019. 95-101.

- D.S. Nagesh, G.L. Datta. Prediction of weld bead geometry and penetration in shielded metal-arc welding using artificial neural networks. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 123( 2) 2002, 303-312. [CrossRef]

- C.R.Wang, Z.Q. Zhong and M. D. Jean. Effect of ingredients proportions on mechanical properties in lasercoated WC-blend welds. Phys. Scr. 99 (2024), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Meng Liu; Chunzheng Duan; Guohe Li; Yujun Cai; Feng Wang; Lei Li. Multi-response optimization of Ni-based laser cladding via principal component analysis and grey relational analysis. Optik-International Journal for Light and Electron Optics. 2023.287. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Zhijie; Du, Yanbin; He, Guohua; Xu, Lei; Shu, Linsen. Optimization and Characterization of Laser Cladding of 15-5PH Coating on 20Cr13 Stainless Steel. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance. 2023, 32 (3) 962-977. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Jiali;Wang, Chi;Hao, Yunbo;Liang, Xudong;Zhao, Kai. Prediction of TC11 single-track geometry in laser metal deposition based on back propagation neural network and random forest. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology. 2022, 36 (3)1417-1425. [CrossRef]

- Liaoyuan Chen, Tianbiao Yu, Xin Chen, Yu Zhao, Chuang Guan. Process optimization, microstructure and microhardness of coaxial laser cladding TiC reinforced Ni-based composite coatings. Optics & Laser Technology, 152, 2022, 108129. [CrossRef]

- Rasool Saeedi , Reza Shoja Razavi, Saeed Reza Bakhshi, Mohammad Erfanmanesh, Ahmad Ahmadi Bani. Optimization and characterization of laser cladding of NiCr and NiCr-TiC composite coatings on AISI 420 stainless steel. Ceramics International. 47( 3), 2021, 4097-4110.

- Lan-Ling Fu; Jin-Shui Yang; Shuang Li; Hao Luo; Jian-Hao Wu. Artificial neural network-based damage detection of composite material using laser ultrasonic technology. Measurement.2023,220,113435. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Arif Mahmood, Andrei C. Popescu, Mihai Oane , Asma Channa, Sabin Mihai, Carmen Ristoscu, Ion N. Mihailescu. Bridging the analytical and artificial neural network models for keyhole formation with experimental verification in laser melting deposition: Anovel approach. Results in Physics. 26, 2021, 104440.

- S. Chowdhury, S. Anand. Artificial neural network based geometric compensation for thermal deformation in additive manufacturing processes. Int. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Conf, Blacksburg, VA, USA (2016).

- W. Sudnik, D. Radaj, W. Erofeew. Computerized simulation of laser beam welding, modelling and verification. J Phys D Appl Phys, 29 (11) 1996, 2811-2817. [CrossRef]

- Yuhang Zhang, Yifei Xu, Yaoning Sun and Wangjun Cheng. Surface quality optimization of laser cladding based on surface response and genetic neural network model. Surface Topography: Metrology and Properties, 10( 4)2022, 10 044007. [CrossRef]

- S. Genna , E. Menna , G. Rubino, F. Trovalusci. Laser machining of silicon carbide: Experimental analysis and multiobjective optimization. Ceramics International 49(7), 2023,10682-10691. [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Weight of elements (%) | |||||

| WC | W | C | Fe | Co | Cu | S |

| >98.3 | 1.3 | 0.0013 | 0.0005 | 0.0013 | 0.0015 | |

| Co | Co | C | Fe | Al | Cu | S |

| >99.8 | 0.02 | 0.065 | 0.005 | 0.05 | 0.009 | |

| Ni | Ni | Co | Fe | Al | C | S |

| >99.9 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0015 | |

| Symbol | Controllable factors | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| A | Substrate | 45steel | 40Cr | - |

| B | Co(%) | 0 | 10 | 20 |

| C | Ni(%) | 0 | 10 | 20 |

| D | Preheat temperature(℃) | 25 | 100 | 200 |

| E | Laser power(W) | 1000 | 1400 | 1800 |

| F | Carrier flowrate (mL/min) | 1400 | 1600 | 1800 |

| G | Scanning speed (mm/min) | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| H | Scanning height (mm) | 15 | 20 | 25 |

| No.of tests | Substrate | Co | Ni | Preheat temperature | laser power | Carrier Flowrate | Scanning Speed | Scanning height | Wear volume | S/N ratio | |

| Mean | St.dev | ||||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | 10-4mm3 | dB | ||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 1000 | 1400 | 2 | 15 | 2.105 | 0.23 | 60.61 |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 100 | 1400 | 1600 | 4 | 20 | 2.470 | 0.65 | 59.20 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 200 | 1800 | 1800 | 6 | 25 | 3.570 | 0.75 | 57.84 |

| 4 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 25 | 1400 | 1600 | 6 | 25 | 2.400 | 0.35 | 59.69 |

| 5 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 100 | 1800 | 1800 | 2 | 15 | 3.330 | 0.52 | 58.02 |

| 6 | 1 | 10 | 20 | 200 | 1000 | 1400 | 4 | 20 | 8.835 | 0.84 | 56.52 |

| 7 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 100 | 1000 | 1800 | 4 | 25 | 3.810 | 0.49 | 57.23 |

| 8 | 1 | 20 | 10 | 200 | 1400 | 1400 | 6 | 15 | 7.160 | 0.95 | 56.81 |

| 9 | 1 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 1800 | 1600 | 2 | 20 | 5.105 | 0.87 | 56.10 |

| 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 200 | 1800 | 1600 | 4 | 15 | 2.020 | 0.12 | 60.70 |

| 11 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 25 | 1000 | 1800 | 6 | 20 | 2.495 | 0.35 | 59.27 |

| 12 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 100 | 1400 | 1400 | 2 | 25 | 3.330 | 0.62 | 58.02 |

| 13 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 100 | 1800 | 1400 | 6 | 20 | 2.355 | 0.36 | 59.42 |

| 14 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 200 | 1000 | 1600 | 2 | 25 | 3.050 | 0.41 | 58.22 |

| 15 | 2 | 10 | 20 | 25 | 1400 | 1800 | 4 | 15 | 7.365 | 0.75 | 56.70 |

| 16 | 2 | 20 | 0 | 200 | 1400 | 1800 | 2 | 20 | 3.375 | 0.42 | 57.90 |

| 17 | 2 | 20 | 10 | 25 | 1800 | 1400 | 4 | 25 | 4.050 | 0.51 | 56.97 |

| 18 | 2 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 1000 | 1600 | 6 | 15 | 8.485 | 0.49 | 56.25 |

| No. of trials |

Atomic concentration(%) | ||||||

| W | O | C | Fe | Ni | Co | ||

| WC | A(white) | 84.167 | 3.774 | 0.866 | 11.193 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| B(black) | 68.122 | 7.338 | 0.717 | 23.742 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| C(grey) | 88.099 | 2.412 | 0.000 | 3.736 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| WC/Ni | A | 97.209 | 0.884 | 1.023 | 0.624 | 0.260 | 0.000 |

| B | 87.608 | 8.248 | 1.897 | 0.000 | 0.781 | 0.000 | |

| C | 88.099 | 2.412 | 0.000 | 4.603 | 4.49 | 0.000 | |

| WC/Co | A | 90.516 | 2.31 | 1.464 | 4.652 | 0.000 | 0.725 |

| B | 64.295 | 9.932 | 4.23 | 21.148 | 0.000 | 0.092 | |

| C | 62.563 | 21.66 | 2.131 | 12.402 | 0.000 | 0.081 | |

| WC/Co/Ni | A | 82.291 | 4.108 | 0.677 | 6.700 | 3.717 | 2.906 |

| B | 54.965 | 36.235 | 1.284 | 5.574 | 1.656 | 0.000 | |

| C | 86.027 | 5.275 | 0.567 | 4.799 | 1.935 | 1.427 | |

| Symbol |

Sum of Squares |

Degree of Freedom |

Mean square |

F-test |

Contribution percent |

| A | 1.82 | 1 | 1.82 | 7.63 | 0.59 |

| B | 108.36 | 2 | 54.18 | 226.6 | 34.82 |

| C | 140.9 | 2 | 70.45 | 294.64 | 45.28 |

| D | 3.17 | 2 | 1.58 | 6.64 | 1.02 |

| E | 20.24 | 2 | 10.12 | 42.33 | 6.51 |

| F | 9.56 | 2 | 4.78 | 20 | 3.07 |

| G | 9.033 | 2 | 4.51 | 18.88 | 2.9 |

| H | 17.59 | 2 | 8.79 | 36.78 | 5.65 |

| Error | 0.47 | 2 | 0.23 | 1 | 0.15 |

| Symbol | Degree of Freedom |

Sum of Squares |

Mean square |

F-test | Prob > F | Adjust-R2 |

| First-order model | 4 | 70.54 | 17.63 | 20.49 | 0.000 | 0.82 |

| Interaction model | 10 | 76.23 | 7.62 | 9.71 | 0.0032 | 0.84 |

| Second-order model | 14 | 77.86 | 5.56 | 4.31 | 0.1273 | 0.73 |

| Second-order model | Interaction model | ||||||

| Source | Coefficient Estimate |

t- statistical |

Prob > F | Source | Coefficient Estimate |

t- statistical |

Prob > F |

| Intercept | 9.0616 | 0.579 | 0.6032 | Intercept | 12.3394 | 2.1465 | 0.069 |

| B | 0.347 | 0.9442 | 0.4147 | B | 0.153 | 0.8176 | 0.4405 |

| C | 0.1333 | 0.331 | 0.7624 | C | 0.4325 | 1.9486 | 0.0924 |

| E | 0.0024 | 0.1687 | 0.8768 | E | -0.0046 | -1.3315 | 0.2248 |

| H | -0.6669 | -0.5984 | 0.5918 | H | -0.6474 | -2.0972 | 0.0742 |

| BC | -0.0011 | -0.1593 | 0.8835 | BC | -0.0034 | -0.7425 | 0.4819 |

| BE | -0.0002 | -1.0098 | 0.387 | BE | -0.0001 | -1.3688 | 0.2134 |

| BH | 0.0138 | 0.9863 | 0.3967 | BH | 0.0095 | 1.0201 | 0.3416 |

| CE | -0.0001 | -0.6562 | 0.5585 | CE | -0.0002 | -1.6971 | 0.1335 |

| CH | 0.0093 | 0.6078 | 0.5862 | CH | -0.0005 | -0.0593 | 0.9544 |

| EH | 0.0004 | 1.3075 | 0.2822 | EH | 0.0003 | 1.5289 | 0.1701 |

| B2 | -0.0084 | -0.9502 | 0.4121 | First-order model | |||

| C2 | 0.0002 | 0.0236 | 0.9827 | Source | Coefficient Estimate |

t- statistical |

Prob > F |

| E2 | 0.0000 | -0.6321 | 0.5722 | ||||

| H2 | -0.0063 | -0.2081 | 0.8485 | Intercept | 7.1378 | 4.7933 | 0.0004 |

| B | 0.1348 | 5.0347 | 0.0002 | ||||

| C | 0.1652 | 6.1673 | 0.000 | ||||

| E | -0.0019 | -2.8876 | 0.0127 | ||||

| H | -0.1713 | -3.1988 | 0.007 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).