1. AI Before Meeting Medical Imaging: From the Origins to Expert Systems

AI permeated medicine slowly but steadily, at first through seminal works, then with the first commercial systems, until the present day when AI represents one of the most promising frontiers of medicine, mainly by deep learning neural networks.

In this narrative review we will describe the history of the development of AI, from the first conceptualizations of learning machines in the 40’s to the modern refinements, regarding neural networks, which allow successful usage of AI in most if not all human disciplines. We will also describe the advancements of the use of AI in medicine, from the first expert systems to modern applications of neural networks in imaging, in particular for oncological applications. The review consists of three main sections: in the first we describe the works of the pioneers of AI in the 20th century, a time when AI was not interested nor capable of analyzing medical images. The second section describes an era when the first AI-based classifications of imaging findings are attempted, with the first widely used machine learning (ML) algorithms. In the present era medical imaging is being transformed by the endless possibilities offered by a large spectrum of neural networks architectures.

2. AI Before Meeting Medical Imaging: From The Origins to Expert Systems

AI is an umbrella term covering a wide spectrum of technologies aiming to give machines or computers the ability to perform human-like cognitive functions such as learning, problem-solving, and decision-making. At its beginning, the goal of AI was to imitate the human mind or, in the words of Frank Rosemblatt

, to make a computer “able to walk, talk, see, write, reproduce itself and be conscious of its existence” [

1].However, it was soon understood that AI could achieve better results at well-defined, specific tasks such as playing checkers [

2], to the level of surpassing the performance of humans, e.g. the computer Deep Blue defeating former world chess champion Garry Kasparov in 1997[

3]. In this section we describe this early phase.

2.1. Prehistory of AI

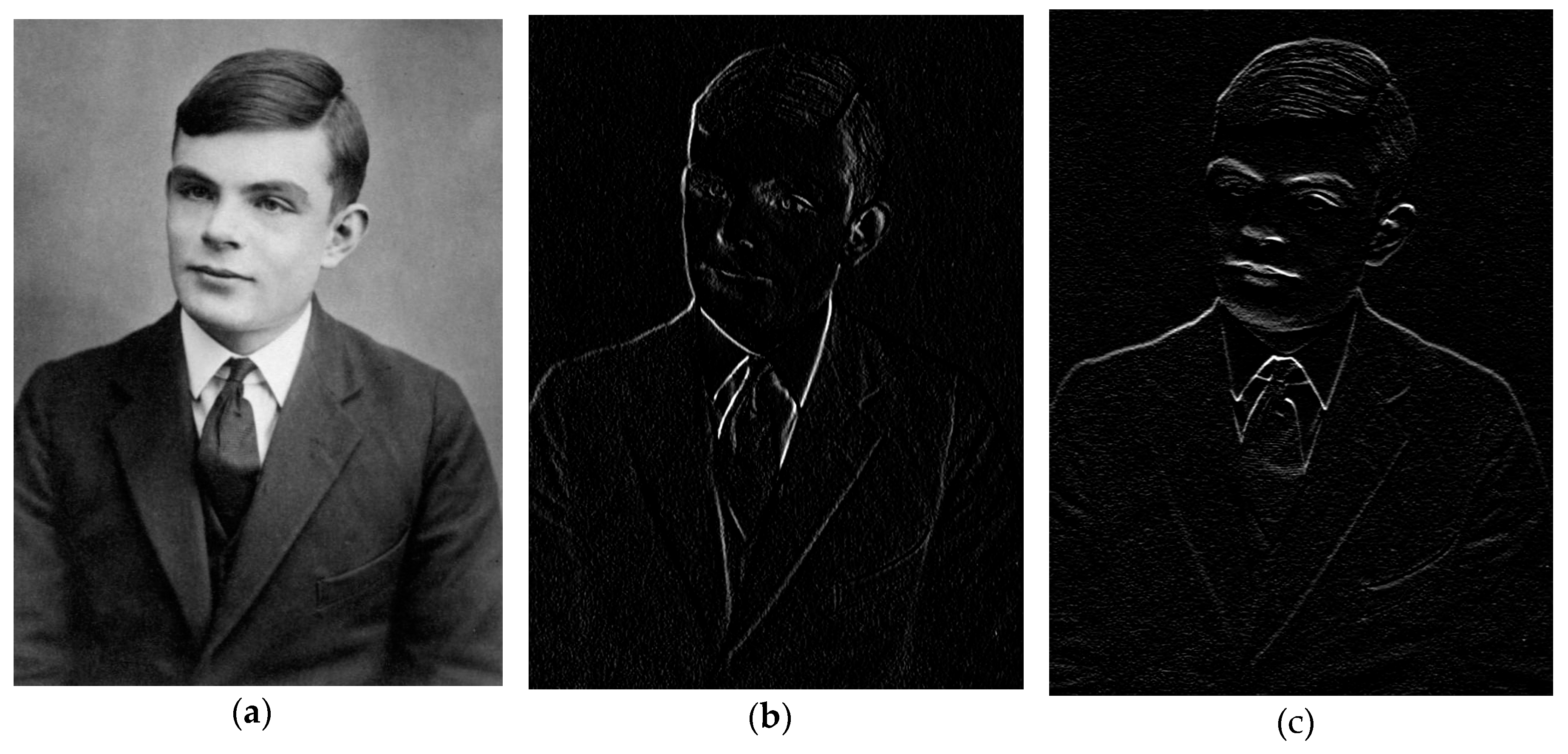

The idea of inanimate objects able to complete tasks that are usually performed by humans and require “intelligence” goes back to ancient times [

4]. The history of AI started with a group of great visionaries and scientists in the 900 which include Alan Turing (London, 1912 – Manchester, 1954,

Figure 1 a), one of the fathers of modern computers. He devised an abstract computer, called the Turing machine, a concept of paramount importance in modern informatics, as any modern computer device is thought to be a special case of a Turing machine [

5]. He also worked at developing a device, the Bombe, at Bletchley Park (75 km northwest of London), to decrypt enemy messages during World War II [

6]. The Bombe, which can be now considered the first computer, involved iteratively reducing the space of solutions from a set of message transcriptions to discover a decryption key. This process had some resemblance to ML, which hypotheses a model from a set of observations [

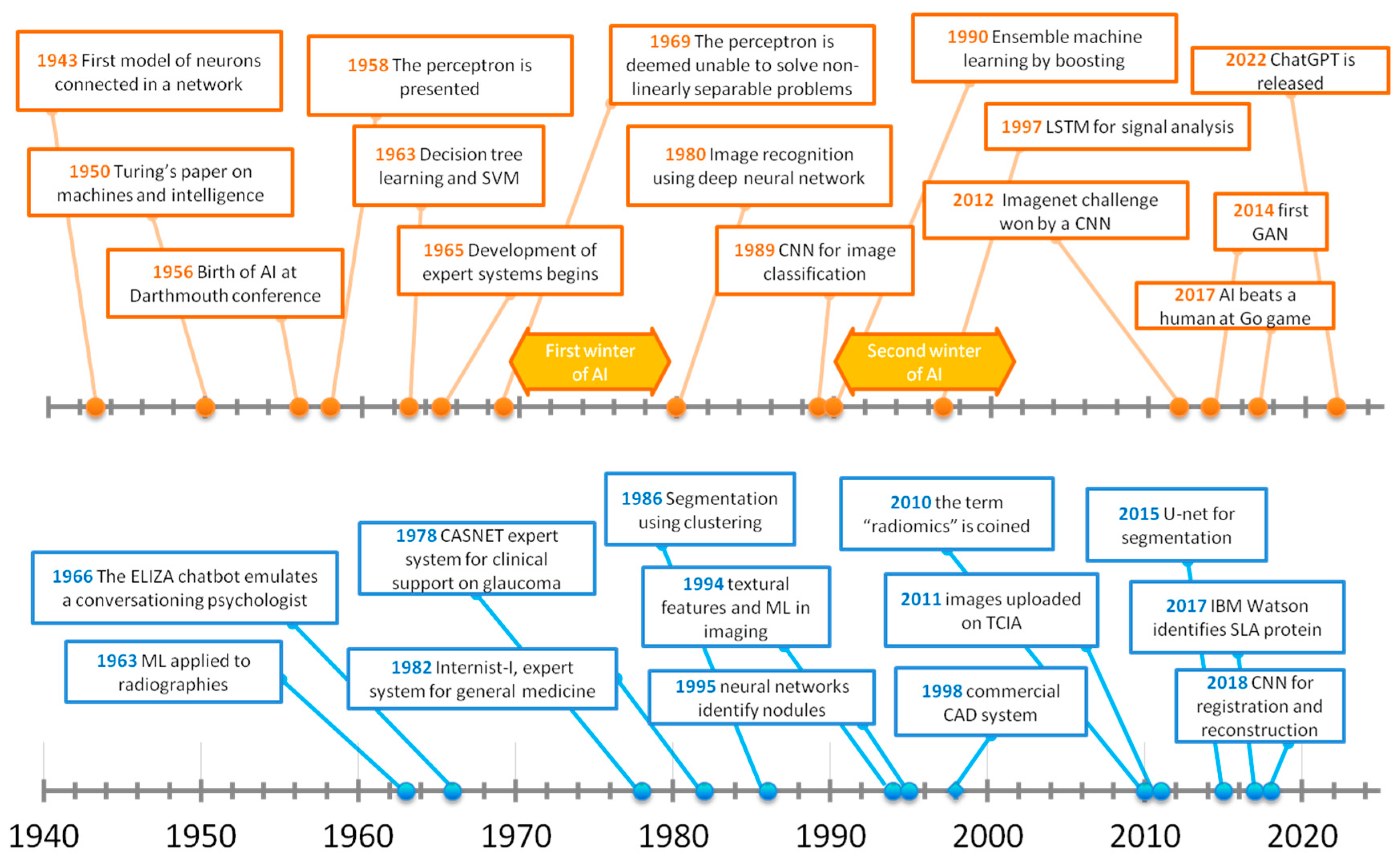

7]. A timeline of the origin and development of AI starting from the Turing machine to reach the triumph of artificial neural networks (ANNs) is provided in

Figure 2.

In a public lecture held in 1947, Turing first mentioned the concept of a “machine that can learn from experience” [

8] and posed the question “can machine think?” in his seminal paper entitled “Computing machinery and intelligence” [

9]. In this paper, Turing introduced a test, the “imitation game” also referred to as the Turing test, to define if a machine can think. In this test, a human interrogates another human and the machine alternatively. If it is not possible to distinguish the machine from the human based upon the answers, then the machine passes the test and is considered able to think.

Turing went on to discuss strategies that might be considered capable of achieving a thinking machine, including AI by programming and learning. He likened the learning process to that of a child being educated by an adult who provides positive and negative examples [

7,

10]. From its very beginning, different branches of AI emerged. Symbolic AI searches the proper rule (

e.g., IF-THEN) to apply to the problem at hand by testing/simulating all the possible rules like in a chess game, without training [

11,

12]. On the other hand, ML is characterized by a training phase, where the machine analyses a set of data, builds a model and measures model performance through a function called goal or cost function [

13]. The term ML was introduced by Arthur L. Samuel (Emporia, USA, 1901 – Stanford, USA, 1990), who developed the first machine able to learn to play checkers [

2]. The dawn of AI is considered the summer conference at Dartmouth College (Hanover, NH, USA) in 1956 [

14]. Also, the term “artificial intelligence” was coined at the meeting by John McCarthy (Boston, USA, 1927 – Stanford, USA, 2011) who defined AI as “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines”. This definition, as well as the implicit definition of AI in the imitation game, escapes the cumbersome issue of defining what “intelligence” is [

15], making the goals and boundaries of the science of AI blurry. For instance, in the early years of AI, research clearly targeted at computers that could have performance comparable with those of the human mind (”strong AI”). In later years, the AI community shifted its aim to more limited realistic tasks, like solving practical problems and carrying out individual cognitive functions ("weak AI") [

15].

2.2. Neural Networks

Neural networks were first conceived in 1943 by Warren S. McCullough (Orange, NJ, USA, 1898 – Cambridge, MA USA, 1969), a neuroscientist, and Walter Pitts (Detroit, USA, 1923 – USA, 1969), a logician, to describe the functioning of the brain using an abstract model [

16]. They proposed a network of units (nodes) that simulate the brain cells, the neurons, which could receive a limited number of binary inputs and send a binary output to the environment or other neurons [

17,

18].However, this early model was not designed to be able to learn [

19], as the weights of its units and signals were fixed, in contrast to modern ML networks, which have learnable weights [

20]. In 1949, the psychologist Donald O. Hebb (Chester, Canada 1904 – Chester, Canada, 1985) introduced the first rule for self-organized learning. He stated that “any two cells or systems of cells that are repeatedly active at the same time will tend to become associated: so that activity in one facilitates activity in the other” [

21], meaning that the weights of connections are increased when frequently used simultaneously [

22]. Inspired by these works, Marvin L. Minsky and Dean Edmonds built an analogue neural network machine called “stochastic neural-analog reinforcement calculator” (SNARC) which could determine a way out of a maze [

23].

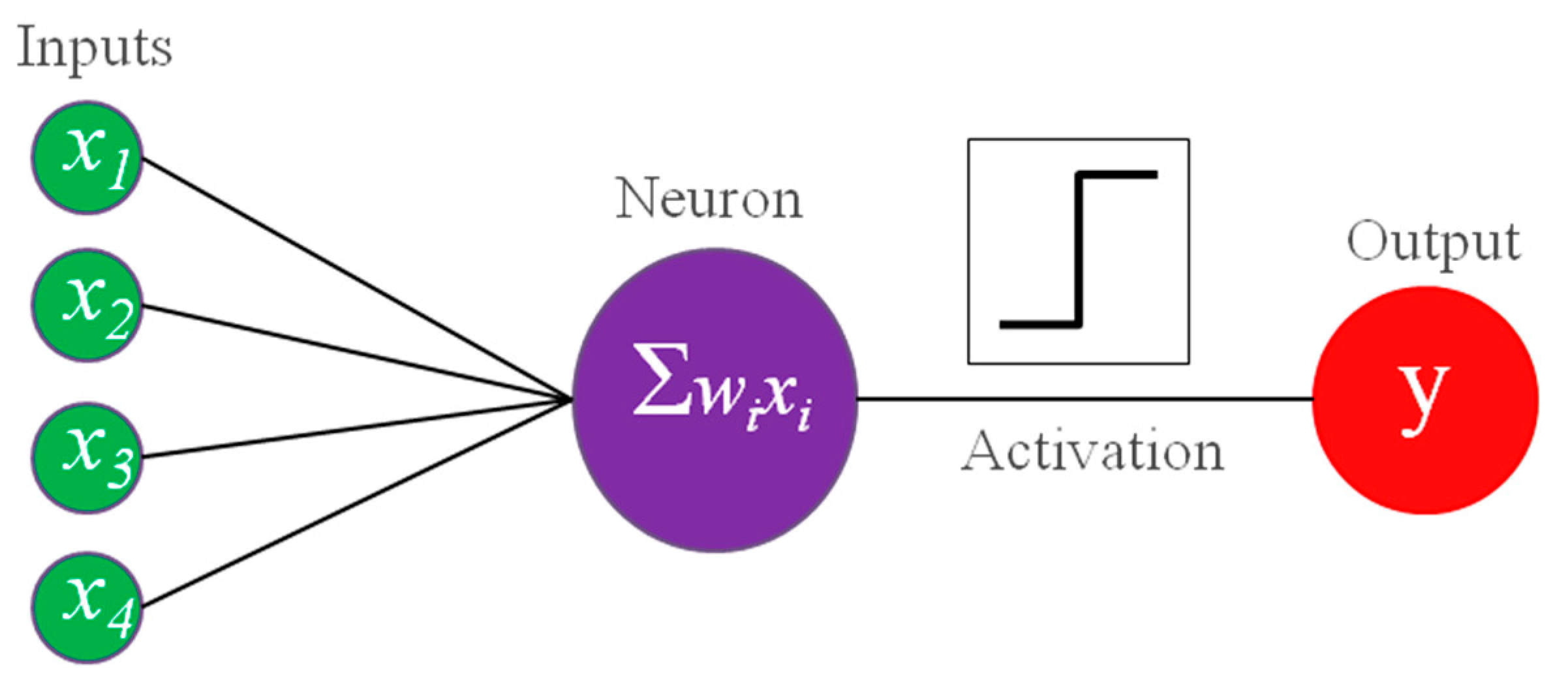

Shortly afterwards, the psychologist Frank Rosenblatt (New Rochelle, NY, USA, 1928 – Chesapeake Bay, USA, 1971) developed a learning neural network machine (

Figure 3), the perceptron [

24]. Since it was built for classification of a binary image generated using a camera, it can be considered as the first application of AI to images [

25]. It used a Heaviside step as activation function, which converts an analogue signal into a digital output [

26]. The learning was accomplished by a delta rule, where delta is simply the difference of the network output and the true value and, an incorrect response is used to modify the weights of the connections towards the correct pattern of prediction [

26]. If multiple units are organized in a layer, to be able to produce multiple outputs from the same input, we obtain a structure which is today called single-layer artificial neural networks (ANNs) [

1]. Later, in 1960, the adaptive linear neuron (ADALINE) used the weighted sum of the inputs to adjust weights [

27], so that it could also estimate how much the answer was right or wrong in a classification problem [

28].

2.3. Supervised and Unsupervised ML

Differently from conventional, statistically based approaches, ML is used to search (“data mining”) for variables of interest and useful correlation and patterns in data, with no hypothesis known in advance to be tested for correlation. From this viewpoint, ML is the inverse of traditional statistical approach [

29]. Their training phase can be either supervised or unsupervised. The most common approach is supervised learning, where the system uses training data with corresponding ground truth labels to learn how to predict these labels [

30]. In unsupervised ML, the training data has no ground truth labels, and the ML learns patterns or relationships in the data, resulting in data-driven solutions for dimensionality reduction, data partitioning, and detection of outliers. To the first category belongs the principal component analysis−PCA [

66], which uses orthogonal linear transformation to convert the data into a new coordinate system to perform data dimension reduction [

32]. PCA is useful when, the high number of variables may cause ML models to overfit. Overfitting occurs when a model memorizes the training examples but performs poorly on independent test sets due to a lack of generalization capability [

30].

2.4. First Applications of AI to Medicine: Expert Systems

In 1969 Minsky and Papert proved [

33] that a single-layer ANN was not able to solve classification problems where the separation function is nonlinear [

34]. Given their undisputed authority in the field, the interest and funding in neural networks decreased until the early 1980s, leading to the “first winter” of AI. During this era, the researchers tried to develop systems that could operate in narrower areas. The idea initially came to Edward A. Feigenbaum (Weehawken, NJ, USA, 1936 –) who became interested in creating models of the thinking of scientists, especially the processes of empirical induction by which hypotheses and theories were inferred from knowledge in a specific field [

35]. As a result, he developed expert systems, computer programs that take a decision such as a medical diagnosis using a knowledge database, and a set of IF-THEN rules [

18]..The first was the DENDRAL [

36], which could derive molecular structure from mass spectrometry data by using an extensive set of rules [

23]. One of the first prototypes to demonstrate feasibility of applying AI to medicine was CASNET, a software to provide support on diagnosis and treatment recommendation for glaucoma [

37]. MYCIN was designed to provide disease identification and antibiotic treatment, based on an extensive set of rules and patient data. It was superseded by EMYCIN and the more general purposing INTERNIST-1 [

38]. These systems aiming at supporting the clinician’s decision are called computer decision support systems (CDSS).

Expert systems were limited by poor performance in areas that cannot be easily represented by logic rules, such as detecting objects with significant variability in images. In addition, they cannot learn from new data and update their rules, accordingly, resulting in a lack of adaptability[

6]. For these reasons, in the 1990s the interest shifted to ML, as the larger availability of microcomputers coincided with the development of new popular ML algorithms such as SVMs and ensemble decision trees [

39].

3. Early Applications of AI to Imaging: Classical ML and ANNs

Gwilym S. Lodwick in 1963 calculated the probability of bone tumor diagnosis with good accuracy based on observations such as the lesion’s location relative to the physis and whether it was in a long or flat bone [

40] using a ML algorithm, specifically Bayes rule [

41]. This early attempt can be considered as the first application of ML to medical images. Due to its low computational cost, this approach - by extracting descriptive features from images and then analyzing them with ML models - dominated the AI field for many years until the advent of deep learning.

3.1. Decision Tree Learning

A decision tree is a set of rules for partitioning the data according to their attributes or features (

Figure 4 a). This is a very intuitive process. In fact, the first classification tree is the Porphyrian tree, a device by the 3

rd century Greek philosopher Porphyry (Tyre, Roman Empire, present-day Lebanon, 234 – Rome, 305), to classify living beings. Decision trees can be combined with ML in decision tree learning, where one or more decision trees are grown to create partitions of data according to rules based on the data features, for classification or regression of data.

The first attempt at decision tree methodology can likely be traced to the mid-1950s with the work of the statistician William A. Belson. He aimed at predicting the degree of knowledge viewers had about from the “Bon Voyage” television broadcast, using demographic variables such as occupational and educational levels [

42], overcoming the limitations of linear regression [

43,

44,

45]. Later, J.N. Morgan and J.A. Sonquist [

46] proposed what is now considered the first decision tree method, popularized thanks to the AID computer program [

45]. Impurity is a measure of the class mix of a subset and splits are chosen so that the decrease in impurity is maximized. Currently, the Gini index [

47] is the preferred method for measuring impurity; it represents the probability of a randomly chosen element to be incorrectly classified, so that a value of zero means a completely pure partition. The Classification And Regression Trees−CART by Leo Breiman also used pruning, a process which reduces the tree size to avoid overfitting [

48,

49]. It is still largely used in imaging analysis, due to its intuitiveness and ease of use, e.g it could classify tumor histology from image descriptions in MRI [

50].

3.2. Support Vector Machines and Other Traditional ML Approaches

The aim of Support Vector Machines (SVMs) is to determine a hyperplane in the

n-dimensional space of attributes that separates data into two or more classes for the purpose of classification. The searched hyperplane is such that the minimum distance from it to the convex hull (i.e. the minimum enclosing a set of points [

51]) of classes is maximal. This idea was first proposed by Vladimir Vapnik and Alexey Chervonenkis in 1964 [

52]. A few years later, Corinna Cortes and Vladimir Vapnik [

53] proposed the first soft-margin SVM. The latter

allows the inclusion of a certain number of misclassified data while keeping the margin as wide as possible so that other points can still be classified correctly. SVM can also perform non-linear classification using the “kernel trick”, a mapping to higher dimensional feature space using proper transformations (

e.g., polynomial functions, radial basis functions). The SVM is one the most frequently used ML approaches in medical data analysis [

54] and it has been found, for instance, to provide accurate results for classification of prostate cancer from multiparametric MRI [

55]. SVM classifiers were also widely used in the analysis of neuroimaging data, e.g. in the study of neurodevelopment disorders [

56] and of neurodegeneration [

57]. An example of SVM classification is provided in

Figure 4 b.

Another popular traditional ML approach is Naïve Bayes learning. It involves constructing the probability of assigning a class to a vector of features based on Bayes’ theorem, and then assigning the class with the maximum probability [

58,

59]. The K-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm was introduced by T. Cover and P. Hart in 1967 [

60]. Its formulation appears to have been made by E. Fix and J.L. Hodges in a research project carried out for the United States armed forces which introduced discriminant analysis, a non-parametric classification method [

61]. They investigated a rule which might be called the KNN rule, which assigns to an unclassified sample point the classification of the nearest of a set of previously classified points.

Traditional machine learning (ML) models analyze input data structured as vectors of attributes, also known as variables, descriptors, or features. These features can be either semantic (e.g., "spiculated lesion") or agnostic (quantitative) [

62]. Coding a problem in terms of a feature vector requires can lead to an extremely large number of features depending on the complexity of the problem to address, increasing the risk for overfitting. Feature selection is a process to determine a subset of features such as all the features in the subset are relevant to the target concept, and no feature is redundant [

63,

64]. A feature is considered redundant when adding it on top of the others will not provide additional information; for instance, if two features are correlated these are redundant to each other [

65]. Feature selection may be considered an application of the Ockham’s razor to ML. According to the Ockham’s razor principle, attributed to the 14

th-century English logician William of Ockham (Ockham, England, 1285 – Munich, Bavaria, 1347), given two hypotheses consistent with the observed data, the simpler one (

i.e., th ML model using the lower number of features), should be preferred [

66]. Depending on the type of data, feature selection can be classified as supervised, semi-supervised, and unsupervised [

65]. There are three main classes of feature selection methods: (i) embedded feature selection, where ML includes the choice of the optimal subset; (ii) filtering, where features are discarded or passed to the learning phase according to their relevance; and (iii) wrapping, which requires evaluating the accuracy of a specific ML model on different feature subsets for choice of the optimal one [

63]. “Tuning” is the task of finding optimal hyperparameters for a learning algorithm for a considered dataset. For instance, decision trees have several hyperparameters that may influence its performance, such as the maximum depth of the tree and the minimum number of samples at a leaf node [

67]. Early attempts for parameter optimization include the introduction of the Akaike information criteria for model selection [

68]. More recent strategies include grid search, in which all parameter space is discretized and searched, and random search [

69], in which values are drawn randomly from a specified hyperparameter space, which is more efficient especially for ANNs [

67].

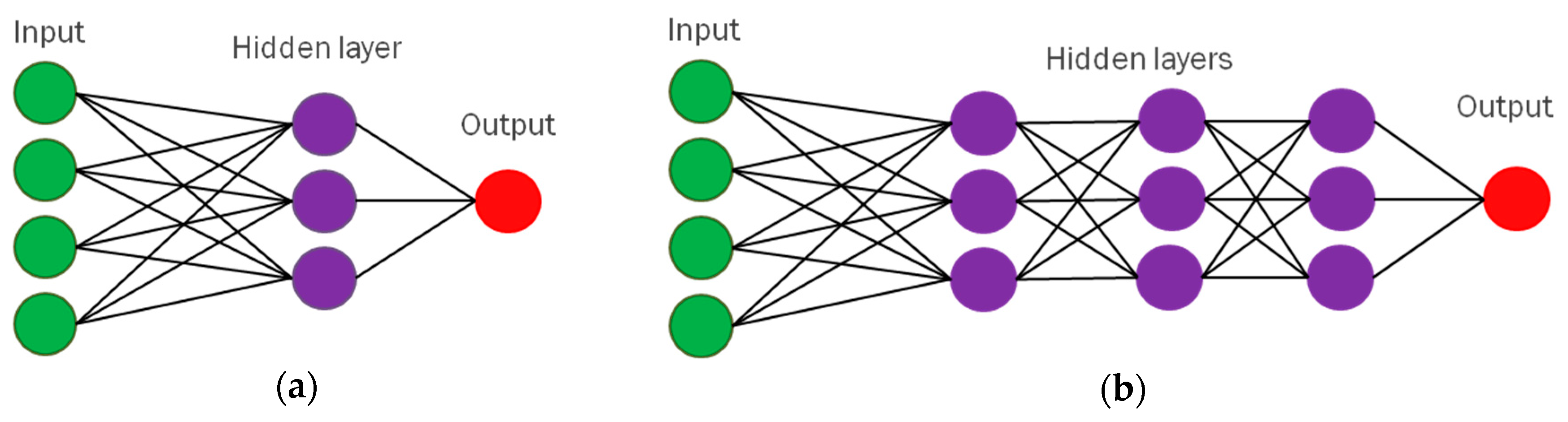

3.3. First Uses of Neural Networks for Image Recognition

To address the criticism of M. Minsky and S. Papert [

33] and enable neural networks to solve nonlinearly separable problems, many additional layers of neuron-like units must be placed between input and output layers, leading to multilayer ANNs. The first work proposing multilayer perceptrons was published in 1965 by Ivakhnenko and Lapa [

71]. A multilayered neural network was proposed in 1980 by Fukushima, called “neocognitron” [

70] which was used for image recognition [

71] and included multiple convolutional layers to extract image features of increasing complexity. These intermediate layers are called

hidden layers [

18] and multilayer architectures of neural networks are called “deep”. Hence, the term “

deep learning” (DL) was coined by R. Dechter [

72]. The difference between single-layer and multilayer ANNs is shown in

Figure 5.

In a DL neural network, training is performed by updating all the weights simultaneously in the opposite direction to a vector that indicates by the change in the error if weights are changed by a small amount, to search a minimum in the error in response. This method is called “standard gradient descent” [

73], and one of its limitations was that it made tasks such as image recognition too computationally expensive.

The invention of back-propagation learning algorithm in mid 1980s [

74] improved significantly the efficiency of training of neural networks. The back-propagation equations provide us with a way of computing the gradient of the cost function starting from the final layer [

75]. Then the backpropagation equation can be applied repeatedly to propagate gradients through all modules all the way to the input layer by using the chain rule of derivatives to estimate how the cost varies with earlier weights [

76]. This learning rule and its variants enabled the use of neural networks in many hard medical diagnostic tasks [

77].

The introduction of the rectifier function or ReLu (rectified linear unit), an activation function, which is zero if the input is lower than the threshold and is equal to the input otherwise, helped reducing the risk of vanishing/exploding gradients [

78] and is the most used activation function as of today.

Despite these progresses, from the beginning of the 1990s, AI entered its second winter, which involved the use of neural networks, to the point that, at a prominent conference, it was noted that the term “neural networks” in a manuscript title was negatively correlated with acceptance [

79]. This new AI winter was partly due to vanishing/exploding gradient problem of DL, which is the exponential increase or decrease of the backpropagated gradient of the weights in a deep neural network.

3.4. Ensemble Machine Learning

During the second winter of AI in the 1990s, while neural networks saw a decrease of interest because of difficulty in training, AI research was focused on other ML techniques such as SVM and decision trees, and on ways to improve their accuracy. Significant improvements in accuracy of decision trees arise from growing an ensemble of trees and subsequently aggregating their predictions[

80]. In bagging aggregation [

81], to grow each tree a random selection is made from the examples in the training set [

82], using a resampling technique approach called “bootstrap” [

83]. The bagging aggregation averages over the versions when predicting a numerical outcome and does a plurality vote when predicting a class [

84]. Random forest, proposed in 1995 by Tin K. Ho [

85], is an example of this approach. In boosting aggregation [

86], the distribution of examples is filtered in such a way as to force the weak learning algorithm to focus on the harder-to-learn parts of the distribution. The popular Adaboost (from ‘adaptive boosting’) reweights individual observations in subsequent samples and is well suited for imbalanced datasets [

87].

3.5. ML Applications to Medical Imaging: CAD and Radiomics

Computer-aided detection or diagnosis (CAD) systems assist clinicians by analyzing medical images and highlighting potential lesions or suggesting diagnoses [

88,

89]. Early CAD systems used hand-crafted image features which were introduced into rule-based algorithms to produce an index (

e.g., a probability of malignancy) to be used for diagnosis [

90]. Features could include spiculations, roughness of margins, and perimeter-to-area ratio, for distinguishing malignant breast lesions [

91] or lung disease in radiographies [

92].

The first commercial CAD system was the ImageChecker M1000 (R2 Technology, Los Altos, CA, USA) which received US Food and Drug Administration−FDA approval in 1998 [

93] and provided the likelihood of malignant lesions according to the presence of clusters of bright spots and spiculated masses, also highlighting regions at risk of malignancy [

90]. Other breast CAD systems were proposed for breast magnetic resonance imaging: CADstream (Merge Healthcare Inc., Chicago, ILL, USA) and DynaCAD for breast (Invivo, Gainesville, FL, USA) [

90].

Early CAD systems exhibited lower specificity and positive predictive value compared to double reading by radiologists, rendering the sole use of CAD not advisable [

94].

Textural features, firstly introduced by Robert.M. Haralick and coworkers in 1973 [

95], began to be used for quantitative analysis of texture with ML for pattern recognition on computed tomography [

96] . The term “radiomics” first appeared in 2010 [

97,

98] combining the terms “radio” referring to radiological sciences and the suffix “omics” often used in biology (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics), to

emphasize a research field encompassing the entire view of a system by mining a large amount of data [

99]. Radiomics focused on investigating the tumor phenotype in imaging for building prognostic and predictive models [

100], in particular for oncological applications [

14]. Thus, it has largely contributed to the idea that ML can be applied to quantitatively analyze images [

101]. An array of ML techniques is currently used for radiomics, including SVM and ensemble decision trees [

102]. The radiomic approach, complemented by ML, has been largely implemented in a large variety of studies devoted to the identification of imaging-based biomarkers of disease severity assessment or staging, and patient’s outcome or risk for side effects [

103,

104,

105,

106,

107]. The scientific community is still investigating the robustness and reproducibility of radiomics features and their dependence on image acquisition systems and parameters across different modalities [

135].

4. The Era of Deep Learning in Medical Imaging

In 1989, Yann LeCun introduced the concept of a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to recognize handwritten digits, paving the way to the use of deep neural networks in imaging [

110]. CNNs have layers that perform a convolution operation with a kernel which acts as a filter

e.g., a Sobel filter, whose effect is shown in Fig 1b and 1c. The numerical values of the kernels that operate image filtering are not fixed a-priory; they are learned from data and set during the training phase [

90]. Unlike the traditional ML approach, the DL do not require extraction of meaningful features to describe the image. The performance of CNNs can be boosted by artificially augmenting the dataset by affine transformations of the images, like translation, scaling, squeezing and shearing, a strategy which reduces overfitting [

79]. Further improvements were achieved with the introduction of specialized layers,

i.e. stacks of neural units that perform a particular task within the DL architecture like dropout [

111], pooling and fully connected layers [

90], allowing an endless spectrum of configurations for the most diverse tasks. In 2012, a deep CNN developed at the University of Toronto had excellent performance at the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge in a 1.2 million high-resolution images of 1,000 classes [

112]. Competitions or challenges have become a major driver of progress in AI [

113,

114]. Autoencoders and Convolutional Autoencoders [

115] are used for dimensionality reduction, data and image denoising, and uncovering hidden patterns in unlabeled data. Additionally, sparse autoencoders can generate extra useful features [

116].

Consequently, it is now clear that DL can be designed for almost any many domains of science, business, and government to perform as diverse as image, signal and sound recognition, transformation or production.

4.1. Medical Images Classification with Deep Learning Models

Neural networks began to be used in CAD by M.L. Giger and coworkers in radiographic images [

89,

117,

118], e.g. in lung [

119] and breast [

88] investigations. In the ’90s [

117] researchers started to use CNNs to identify lung nodules [

120,

121], and to detect microcalcifications in mammography [

122]. Since the first attempts CNNs demonstrated a great potential to solve a large variety of classification tasks, thus they have been implemented across many pathologies and imaging modalities, allowing the analysis of 2D, 3D [

123]. The CardioAI CAD system was one of the first neural network-based commercial systems for analyzing cardiac magnetic resonance images [

124]. Moreover, AI can integrate data from different modalities, an approach termed multimodal AI or multimodal data fusion, which can, for instance, be used to diagnose cancer using both imaging and patient EHR data. This task can be accomplished by designing neural networks that accept multiple data, resulting in multidimensional analysis [

125]. A number of clinical trials have demonstrated the utility of AI-based CAD [

126]. The ScreenTrustCAD prospective clinical trial demonstrated non-inferiority of AI alone compared with double reading by two radiologists on screening mammography. Also in their results,

double reading with one radiologist and AI was superior to double reading by two radiologists, possibly due the combination of the sensitivity ability of AI to detect cancer with sufficient sensitivity, and the ability of consensus readers to increase specificity by dismissing AI false positives [

127]

. Recently, the You Only Look Once (YOLO) neural network architecture, initially designed for real-time object detection, has been under investigation for polyp detection in colonoscopy [

136] and identifying dermoscopic and cardiovascular anomalies [

129]

.

Among the CNN-based systems approved for clinical use, ENDOANGEL (Wuhan EndoAngel Medical Technology Company, Wuhan, China), can provide an objective assessment of bowel preparation every 30 seconds during the withdrawal phase of a colonoscopy [

130].

These DL models are characterized by a very large number of free parameters that must be set during the training phase making network training from scratch can computationally intensive. In Transfer Learning [

131,

132], the knowledge acquired on one domain is transferred to a different one, much like a person using their guitar-playing skills to learn the piano [

133]. This allows a learner in one domain (

e.g., radiographs) to leverage information previously acquired by models such as

the Visual Geometry Group (VGG) and Residual Network (ResNet) which were trained on a related domain (e.g. images of common objects).

4.2. Medical Images Classification with Deep Learning Models

AI can be used in medical image analysis to automatically subdivide an image into several regions based on the similarity or difference between regions, thus performing segmentation of soft tissues and lesions, a tedious task if performed manually. Initially automated segmentation was attempted by using unsupervised [

134] or, supervised ML [

135]. Another approach consists in calculating radiomic features in the neighborhood of pixels and then classifying them using ML [

136]. Image segmentation was made more efficient by the U-Net CNN [

137] currently used for a large variety of segmentation tasks across different image modalities [

138,

139,

140,

141,

142,

143]. It consists of an encoder branch where the input layer is followed by several convolutional and pooling layers, as in a CNN architecture for image classification; then, a symmetric decoder branch allows obtaining a segmentation mask with the same dimension of the input image. The U-Net's peculiar skip connections bridge the encoder and decoder, directly transferring detailed spatial information to the upsampling path, enabling precise object locations in the final segmentation masks [

144]. In 2016, Ö. Çiçek and coworkers [

145] presented a modified three-dimensional version of the original U-Net (3D U-Net) for volumetric segmentation.

4.3. Medical Image Synthesis: Generative Models

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) represent a DL architecture capable of generating new and realistic images by training from a dataset of images, video or other types of data [

146]. GANs include two DL networks, a generator and a discriminator that are trained in an adversarial way, the target goal being to train the generator to produce an image realistic enough to induce the discriminator into classifying it as real. By using GANs it is possible to generate images from other images or from a text string, for instance. One of the most recent architectures for image generation is stable diffusion, which can produce high quality images from text or text-conditional images, e.g. “basal cell carcinoma” in a dermoscopic image [

147].

The use of generative models has proven to be valuable in medical imaging applications, including data synthesis or augmentation [

148,

149]. An example could be the generation of pseudo healthy images, images that visualize a negative image for a patient that is being examined in order to facilitate lesion detection [

150]. Virtual patient cohorts can be synthesized to perform virtual clinical trialsfor testing test new drugs, therapies or diagnostic interventions thus reducing the cost of clinical trials on humans [

151].

Other applications include image denoising and artifact removal [

152], image translation between different modalities [

153], and multi-site data harmonization [

154]. Fast AI-based image reconstruction also emerged to allow real-time MRI imaging [

155]. GAN-based MRI image reconstruction particularly excels in capturing fine textures [

158]. CNNs also have been applied for rigid [

157] and deformable image registration [

156]. A new promising neural architecture, the neural fields, can perform efficiently any of the above tasks by

parameterizing physical properties of images [

159].

4.4. From Natural Language Processing to Large Language Models

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) process an input sequence one element at a time, maintaining in their hidden units a ‘state vector’ that implicitly contains information about the history of all the past elements of the sequence. RNNs can predict the next character in a text or the next word in a sequence [

76] Making them useful for speech and language tasks. However, their

training is challenging because the backpropagated gradients can either grow or shrink at each time step. Over many time steps, this can lead to gradients that either explode or vanish [

76]. In 1997, long short-term memory (LSTM) RNNs were invented [

162], which solve the problem of vanishing gradients for sequences of symbols by including a forget gate which allows the LSTM to reset its state [

163,

164]. This subfield of AI aiming at developing the computer abilities to understand or generate human language is called natural language processing (NLP) [

165]. There has been a surge of research in NLP diagnostic models from structured or unstructured electronic health records (EHR) [

166,

167,

168]. In 2007, IBM introduced Watson, a powerful NLP software in which, in 2017, was instrumental in identifying new RNA-binding proteins linked amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [

124].

A breakthrough in this field was the Transformer deep learning architecture, which, by employing the self-attention mechanism[

169] showed excellent capabilities in managing dependencies between distant elements in an input sequence and in exploiting parallel processing to reduce execution times. Transformers are the basic components of Large Language Models (LLM), such as the Generative Pretrained Transformers (GPT) by OpenAI or the Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) by Google. These are trained on large amount of data from the web and are able to generate text to make translation, summarization and completion of sentences, and also production of creative contents in domains specified by the users. LLM can be used as a decision support system which recommends appropriate imaging from patient’s symptoms and history [

170]. Recently, GPT4, a new version of the ChatGPT by OpenAI, a generative LLM that can generate human-like answers, was released. GPT4 can analyze images, implying that, if successfully applied to radiology, this could result in a CAD system that writes diagnoses from images [

170] and can act as a virtual assistant to the radiologist [

171].

A transformer-based encoder-decoder model analyzing chest radiograph images to produce radiology report text, was assessed by comparing its generated reports with those generated by radiologists [

172].

Beyond the automated image interpretation tasks, since the public availability of the ChatGPT chatbot at the end of 2022, it became apparent its potential use for example in assisting clinicians in the generation of context-aware descriptions for reporting tasks [

170]. Similar uses entail a series of implications that are much debated in the community [

173]. Moreover, LLMs can aid in patients comprehending their reports by summarizing information at any reading level and in the patient's preferred language [

171]. The architectures initially developed to understand and generate text have soon been adapted for other tasks in several domains, including computer vision. Vision Transformers (ViT) [

174] are a variant of Transformers specifically designed for computer vision tasks, such as image classification, object detection, and image generation. Instead of processing sequences of word tokens (i.e. elements of textual data such as words and punctuation marks) as they do in NLP tasks, ViT process image patches to accomplish relevant tasks in medical image analysis, such as lesion detection, image segmentation, registration and classification [

171]. The image generation processes operated by GANs could be further enhanced by implementing the attention mechanisms [

167]. Combining ViTs for analyzing diagnostic images with LLMs for clinical reports interpretation could result in a comprehensive image-based decision support tool. An extremely appealing use of Trasformers is their potential to handle multimodal input data. This capability was demonstrated in the work by Akbari et al. [

175], where a trasformer-based architecture, the Video-Audio-Text Transformer, was developed to integrate images, audio and text.

The possibility to implement modality-specific embedding to convert the entries of each modality to processable information for a transformer-like architecture opens the possibility to analize in a single framework heterogenous data types, which would be extremely relevant for medical applications where complementary information are encoded in textual clinical reports and tests, medical imaging, genetic and phenotypic information [

151].

5. Open challenges for AI in Medical Imaging

In 2017, for the first time in history, DeepMind’s AlphaGo, a self-trained system based on a deep neural network has beaten the world champion in arguably the most complex board game (named “Go”), thus achieving superhuman performance [

176]. It is no wonder then that AI has achieved physician-level accuracy at a broad variety of diagnostic tasks, including image recognition[

127], segmentation and generation [

177,

178]. Since recently, multi-input AI models can merge and mine the complementary information encoded in omics data, EHRs, imaging data, phenomics and environmental data of the patient, which represent a current technical challenge [

151]. Meta AI’s Imagebind[

179] and Google Deepmind’s Perceiver IO[

180] represent significant advancements in in processing and integrating multimodal data.

Other than the flexibility of architecture, other reasons contributed to the large adoption of DL in medical imaging [

183]:

- ○

- ○

he advent of graphics processing units−GPUs and cloud computer which has made available the large computational power needed to train DL models in large datasets;

- ○

the increasing tendency of the researcher community to make the codes and data publicly available;

- ○

Alongside neural networks, other ML techniques remain largely used, due to their ability to accurately solve classification and regression problems without the need for expensive computational resources [

102]. ML can also assist in diagnosing conditions from clinical data, such as myocardial infarction [

185,

186] and in making differential diagnosis among various findings in neonatal radiographs [

187]. In particular, decision trees have demonstrated the ability to

predict specific phenotypes from raw genomic data[

188]

and to assign emergency codes based on symptoms during triage in emergency departments [

189]

.

Despite these successes, there are also drawbacks. A large fraction of AI tools lacks evidence of efficacy reported in peer-reviewed scientific journals [

190]. The performance obtained in the research stage is often difficult to maintain in clinical use [

191]. Therefore, for AI tools to be adopted in clinical practice, a systematic clinical evaluation or trials are warranted. Another relevant criticism raised against the current AI-based tools for medical imaging application is their “narrow scope” as they are frequently designed to detect image abnormalities or pathological conditions, but should be refined to predict clinically meaningful endpoints, which include lesion malignancy, need for treatment and patient survival [

192].

AI also brings risks and ethical issues, such as the need to ensure fairness, meaning it should not be biased against some group or minority [

193]. Bias in AI software may result from unbalanced training data. For instance,

due to a severe imbalance in the training data, an AI tool for diagnosing

diabetic retinopathy was found to be more accurate for light-skinned subjects than for dark-skinned subjects [

194]

. Another risk arises from differences between the training data used to develop the algorithm and actual patient data, known as data shift. Changes in patient or disease characteristics or technical parameters (e.g. treatment management, imaging acquisition protocol) over time or across locations can affect the accuracy of AI (input data shift) [

195]

. Additional risks related to AI include cybersecurity challenges [

196]. Implementating AI requires managing these risks through a quality assurance program and quality management system [

197]

. Within the European Union (EU), the regulatory framework for medical devices in the is defined by European Medical Devices Regulation (EU) 2017/745 (EU MDR) and the General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR), which establish criteria for AI implementation [

198]

. Furthermore, the EU has proposed legislation known as "The Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act)" [

199], aiming at creating a unified regulatory and legal structure for AI.

Finally, a major obstacle to the widespread diffusion of AI-based tools in the field of medical imaging is that very often these systems are seen as black boxes. The scientific community is developing explainability frameworks to make AI models more transparent and understandable to humans leading to “explainable AI” (XAI).

Explainability in AI refers to the ability to understand and interpret how an AI system arrives at its decisions or outputs, for instance by analysing the importance of the feature used. Both system developers and end users can get in this way an idea of the motivations behind the decision provided by an AI system. XAI is essential in DL applications to medical imaging to ensure transparency, accountability, safety, regulatory compliance, and clinical applicability [

200]. By providing interpretable explanations for DL model predictions, XAI techniques enhance the trust, acceptance, and effectiveness of AI systems in healthcare, ultimately improving patient outcomes and advancing the field of medical imaging.

6. Conclusions

After a long and tumultuous history, we are in a phase of enthusiasm and promises regarding AI applications to medicine. Thanks to its versatility and impressive results and fueled by the availability of powerful computing resources and open-source libraries, AI is one of the most promising frontiers of medicine. It is worth underlining that, although DL techniques are very powerful and are enjoying great popularity in recent years, some medical imaging tasks can be successfully addressed by traditional ML methods. The latter, such as RF or SVM, require significantly less data for model training and are less prone to overfitting, thus providing more easily generalizable results than DL models. Furthermore, the predictions of these models are far more explainable than those provided by DL ones. Indeed, to facilitate the diffusion of AI-based tools in clinical workflows, in addition to the development of increasingly cutting-edge technological solutions that can answer different clinical questions, AI-based systems should be validated in large-scale clinical trials to demonstrate their effectiveness and should be made explainable to gain the trust of doctors and patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and Y.Y.; methodology, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, A.R.; visualization, G.P.; supervision, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente) [no grant number provided].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Radanliev, P.; de Roure, D. Review of Algorithms for Artificial Intelligence on Low Memory Devices. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 109986–109993. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, A. Some Studies in Machine Learning Using the Game of Checkers. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1959. [CrossRef]

- Artificial Intelligence: Chess Match of the Century | Nature Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/544413a (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Fron, C.; Korn, O. A Short History of the Perception of Robots and Automata from Antiquity to Modern Times. In Social Robots: Technological, Societal and Ethical Aspects of Human-Robot Interaction; Korn, O., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 1–12 ISBN 978-3-030-17107-0.

- Common Sense, the Turing Test, and the Quest for Real AI | The MIT Press Available online: https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/common-sense-turing-test-and-quest-real-ai (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Haenlein, M.; Kaplan, A. A Brief History of Artificial Intelligence: On the Past, Present, and Future of Artificial Intelligence. California Management Review 2019, 61, 000812561986492. [CrossRef]

- Muggleton, S. Alan Turing and the Development of Artificial Intelligence. AI Communications 2014, 27, 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Turing, A. Lecture on the Automatic Computing Engine (1947). In Lecture on the Automatic Computing Engine (1947); Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Turing, A.M. I.—COMPUTING MACHINERY AND INTELLIGENCE. Mind 1950, LIX, 433–460. [CrossRef]

- Reaching for Artificial Intelligence: A Personal Memoir on Learning Machines and Machine Learning Pioneers - UNESCO Digital Library Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367501?posInSet=38&queryId=2deebfb4-e631-4723-a7fb-82590e5c3eb8 (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Understanding AI - Part 3: Methods of Symbolic AI Available online: https://divis.io/en/2019/04/understanding-ai-part-3-methods-of-symbolic-ai/ (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Garnelo, M.; Shanahan, M. Reconciling Deep Learning with Symbolic Artificial Intelligence: Representing Objects and Relations. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2019, 29, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Sorantin, E.; Grasser, M.G.; Hemmelmayr, A.; Tschauner, S.; Hrzic, F.; Weiss, V.; Lacekova, J.; Holzinger, A. The Augmented Radiologist: Artificial Intelligence in the Practice of Radiology. Pediatr Radiol 2021. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.; Minsky, M.L.; Rochester, N.; Shannon, C.E. A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, August 31, 1955. AI Magazine 2006, 27, 12–12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. On Defining Artificial Intelligence. Journal of Artificial General Intelligence 2019, 10, 1–37. [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, W.S.; Pitts, W. A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity. Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 1943, 5, 115–133. [CrossRef]

- Piccinini, G. The First Computational Theory of Mind and Brain: A Close Look at Mcculloch and Pitts’s “Logical Calculus of Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity.” Synthese 2004, 141. [CrossRef]

- Basheer, I.A.; Hajmeer, M. Artificial Neural Networks: Fundamentals, Computing, Design, and Application. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2000, 43, 3–31. [CrossRef]

- Deep Learning in Neural Networks: An Overview - ScienceDirect Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0893608014002135 (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Wang, H.; Raj, B. On the Origin of Deep Learning 2017.

- Hebb, D. O. Organization of Behavior. New York: Wiley, 1949, Pp. 335, $4.00 - 1950 - Journal of Clinical Psychology - Wiley Online Library Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1097-4679(195007)6:3%3C307::AID-JCLP2270060338%3E3.0.CO;2-K (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Chakraverty, S.; Sahoo, D.M.; Mahato, N.R. Hebbian Learning Rule. In Concepts of Soft Computing: Fuzzy and ANN with Programming; Chakraverty, S., Sahoo, D.M., Mahato, N.R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 175–182 ISBN 9789811374302.

- Toosi, A.; Bottino, A.G.; Saboury, B.; Siegel, E.; Rahmim, A. A Brief History of AI: How to Prevent Another Winter (A Critical Review). PET Clinics 2021, 16, 449–469. [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, F. The Perceptron: A Probabilistic Model for Information Storage and Organization in the Brain. Psychol Rev 1958, 65, 386–408. [CrossRef]

- Parhi, K.; Unnikrishnan, N. Brain-Inspired Computing: Models and Architectures. IEEE Open Journal of Circuits and Systems 2020, 1, 185–204. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M.R.W. Connectionism and Classical Conditioning. Comparative Cognition & Behavior Reviews 2008, 3.

- Macukow, B. Neural Networks – State of Art, Brief History, Basic Models and Architecture. In Proceedings of the Computer Information Systems and Industrial Management; Saeed, K., Homenda, W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 3–14.

- Raschka, S. What Is the Difference between a Perceptron, Adaline, and Neural Network Model? Available online: https://sebastianraschka.com/faq/docs/diff-perceptron-adaline-neuralnet.html (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Butterworth, M. The ICO and Artificial Intelligence: The Role of Fairness in the GDPR Framework. Computer Law & Security Review 2018, 34, 257–268. [CrossRef]

- Avanzo, M.; Wei, L.; Stancanello, J.; Vallières, M.; Rao, A.; Morin, O.; Mattonen, S.A.; El Naqa, I. Machine and Deep Learning Methods for Radiomics. Med Phys 2020, 47, e185–e202. [CrossRef]

- Wold, S.; Esbensen, K.; Geladi, P. Principal Component Analysis. Proceedings of the Multivariate Statistical Workshop for Geologists and Geochemists 1987, 2, 37–52. [CrossRef]

- Dayan, P.; Sahani, M.; Deback, G. Unsupervised Learning. In Proceedings of the In The MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences; The MIT Press, 1999.

- Minsky, M.; Papert, S. Perceptrons; an Introduction to Computational Geometry; MIT Press, 1969; ISBN 978-0-262-13043-1.

- Spears, B. Contemporary Machine Learning: A Guide for Practitioners in the Physical Sciences. 2017.

- The Dendral Project (Chapter 15) - The Quest for Artificial Intelligence Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/quest-for-artificial-intelligence/dendral-project/7791DA5FAAF8D57E4B27E4EE387758E1 (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Rediscovering Some Problems of Artificial Intelligence in the Context of Organic Chemistry - Digital Collections - National Library of Medicine Available online: https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101584906X921-doc (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Weiss, S.; Kulikowski, C.A.; Safir, A. Glaucoma Consultation by Computer. Computers in Biology and Medicine 1978, 8, 25–40. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.A.; Pople, H.E.; Myers, J.D. Internist-I, an Experimental Computer-Based Diagnostic Consultant for General Internal Medicine. N Engl J Med 1982, 307, 468–476. [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.T.; Pincock, D.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sadowski, D.C.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kroeker, K.I. An Overview of Clinical Decision Support Systems: Benefits, Risks, and Strategies for Success. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Bone Tumor Diagnosis Available online: http://uwmsk.org/bayes/bonetumor.html (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Lodwick, G.S.; Haun, C.L.; Smith, W.E.; Keller, R.F.; Robertson, E.D. Computer Diagnosis of Primary Bone Tumors. Radiology 1963. [CrossRef]

- Belson, W.A. A Technique for Studying the Effects of a Television Broadcast. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C (Applied Statistics) 1956, 5, 195–202. [CrossRef]

- de Ville, B. Decision Trees. WIREs Computational Statistics 2013, 5, 448–455. [CrossRef]

- Belson, W.A. Matching and Prediction on the Principle of Biological Classification. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C 1959, 8, 65–75.

- Ritschard, G. CHAID and Earlier Supervised Tree Methods; 2010; p. 74; ISBN 978-0-415-81706-6.

- Morgan, J.N.; Sonquist, J.A. Problems in the Analysis of Survey Data, and a Proposal. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1963, 58, 415–434. [CrossRef]

- Gini: Variabilità e Mutabilità: Contributo Allo... - Google Scholar Available online: https://scholar.google.it/scholar?cluster=11152260366061875585&hl=it&oi=scholarr (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Podgorelec, V.; Kokol, P.; Stiglic, B.; Rozman, I. Decision Trees: An Overview and Their Use in Medicine. J Med Syst 2002, 26, 445–463. [CrossRef]

- Classification And Regression Trees | Leo Breiman, Jerome H. Friedman, Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.1201/9781315139470/classification-regression-trees-leo-breiman-jerome-friedman-richard-olshen-charles-stone (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Shim, E.J.; Yoon, M.A.; Yoo, H.J.; Chee, C.G.; Lee, M.H.; Lee, S.H.; Chung, H.W.; Shin, M.J. An MRI-Based Decision Tree to Distinguish Lipomas and Lipoma Variants from Well-Differentiated Liposarcoma of the Extremity and Superficial Trunk: Classification and Regression Tree (CART) Analysis. Eur J Radiol 2020, 127, 109012. [CrossRef]

- Convex Hull - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/mathematics/convex-hull (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- V. N. Vapnik, A. Ya. Chervonenkis, “A Class of Algorithms for Pattern Recognition Learning”, Avtomat. i Telemekh., 25:6 (1964), 937–945 Available online: http://www.mathnet.ru/php/archive.phtml?wshow=paper&jrnid=at&paperid=11678&option_lang=eng (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Boser, B.E.; Guyon, I.M.; Vapnik, V.N. A Training Algorithm for Optimal Margin Classifiers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the fifth annual workshop on Computational learning theory; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, July 1 1992; pp. 144–152.

- Guido, R.; Ferrisi, S.; Lofaro, D.; Conforti, D. An Overview on the Advancements of Support Vector Machine Models in Healthcare Applications: A Review. Information 2024, 15, 235. [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Zhao, X.; Wei, H.; Li, Y. Diagnostic Accuracy of Different Computer-Aided Diagnostic Systems for Prostate Cancer Based on Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100, e23817. [CrossRef]

- Retico, A.; Gori, I.; Giuliano, A.; Muratori, F.; Calderoni, S. One-Class Support Vector Machines Identify the Language and Default Mode Regions As Common Patterns of Structural Alterations in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2016, 10.

- Predictive Models Based on Support Vector Machines: Whole-Brain versus Regional Analysis of Structural MRI in the Alzheimer’s Disease - Retico - 2015 - Journal of Neuroimaging - Wiley Online Library Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jon.12163 (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Berrar, D. Bayes’ Theorem and Naive Bayes Classifier.; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 403–412.

- Kepka, J. The Current Approaches in Pattern Recognition. Kybernetika 1994, 30, 159–176.

- Cover, T.; Hart, P. Nearest Neighbor Pattern Classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967. [CrossRef]

- Fix, E.; Hodges, J.L.; USAF School of Aviation Medicine Discriminatory Analysis: Nonparametric Discrimination, Consistency Properties; USAF School of Aviation Medicine: Randolph Field, Tex., 1951;

- Hassani, C.; Varghese, B.A.; Nieva, J.; Duddalwar, V. Radiomics in Pulmonary Lesion Imaging. AJR Am.J.Roentgenol. 2019, 212, 497–504. [CrossRef]

- Blum, A.L.; Langley, P. Selection of Relevant Features and Examples in Machine Learning. Artificial Intelligence 1997, 97, 245–271. [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. Correlation-Based Feature Selection for Machine Learning. Department of Computer Science 2000, 19.

- Huang, S.H. Supervised Feature Selection: A Tutorial. Artificial Intelligence Research 2015, 4, 22. [CrossRef]

- Esmeir, S.; Markovitch, S. Occam’s Razor Just Got Sharper.; 2007; pp. 768–773.

- Probst, P.; Wright, M.N.; Boulesteix, A.-L. Hyperparameters and Tuning Strategies for Random Forest. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2019, 9, e1301. [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A New Look at the Statistical Model Identification. Automatic Control, IEEE Transactions on 1974, 19, 716–723. [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random Search for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2012, 13, 281–305.

- Fukushima, K. Neocognitron: A Self-Organizing Neural Network Model for a Mechanism of Pattern Recognition Unaffected by Shift in Position. Biol. Cybernetics 1980, 36, 193–202. [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, K. Neocognitron: A Hierarchical Neural Network Capable of Visual Pattern Recognition. Neural Networks 1988, 1, 119–130. [CrossRef]

- Dechter, R. Learning While Searching in Constraint-Satisfaction-Problems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fifth AAAI National Conference on Artificial Intelligence; AAAI Press: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, August 11 1986; pp. 178–183.

- Fradkov, A.L. Early History of Machine Learning. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 1385–1390. [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning Representations by Back-Propagating Errors. Nature 1986. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A. Neural Networks and Deep Learning. 2015.

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [CrossRef]

- Kononenko, I. Machine Learning for Medical Diagnosis: History, State of the Art and Perspective. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2001, 23, 89–109. [CrossRef]

- Glorot, X.; Bordes, A.; Bengio, Y. Deep Sparse Rectifier Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; JMLR Workshop and Conference Proceedings, June 14 2011; pp. 315–323.

- Simard, P.Y.; Steinkraus, D.; Platt, J.C. Best Practices for Convolutional Neural Networks Applied to Visual Document Analysis. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, 2003. Proceedings.; August 2003; pp. 958–963.

- Galar, M.; Fernandez, A.; Barrenechea, E.; Bustince, H.; Herrera, F. A Review on Ensembles for the Class Imbalance Problem: Bagging-, Boosting-, and Hybrid-Based Approaches. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews) 2012, 42, 463–484. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Bagging Predictors. Machine Learning 1996, 24, 123–140. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Bootstrap Methods: Another Look at the Jackknife. The Annals of Statistics 1979, 7, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Avanzo, M.; Pirrone, G.; Mileto, M.; Massarut, S.; Stancanello, J.; Baradaran-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Rink, A.; Barresi, L.; Vinante, L.; Piccoli, E.; et al. Prediction of Skin Dose in Low-kV Intraoperative Radiotherapy Using Machine Learning Models Trained on Results of in Vivo Dosimetry. Med.Phys. 2019, 46, 1447–1454. [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.K. Random Decision Forests. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (Volume 1) - Volume 1; IEEE Computer Society: USA, August 14 1995; p. 278.

- Schapire, R.E. The Strength of Weak Learnability. Machine Learning 1990, 5, 197–227. [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A Desicion-Theoretic Generalization of on-Line Learning and an Application to Boosting. In Proceedings of the Computational Learning Theory; Vitányi, P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1995; pp. 23–37.

- Doi, K.; Giger, M.L.; Nishikawa, R.M.; Schmidt, R.A. Computer Aided Diagnosis of Breast Cancer on Mammograms. Breast Cancer 1997, 4, 228–233. [CrossRef]

- Giger, M.L.; Chan, H.-P.; Boone, J. Anniversary Paper: History and Status of CAD and Quantitative Image Analysis: The Role of Medical Physics and AAPM. Medical Physics 2008, 35, 5799–5820. [CrossRef]

- Le, E.P.V.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hickman, S.; Gilbert, F.J. Artificial Intelligence in Breast Imaging. Clinical Radiology 2019, 74, 357–366. [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, L.V.; Gose, E.E. Breast Lesion Classification by Computer and Xeroradiograph. Cancer 1972, 30, 1025–1035. [CrossRef]

- Asada, N.; Doi, K.; MacMahon, H.; Montner, S.M.; Giger, M.L.; Abe, C.; Wu, Y. Potential Usefulness of an Artificial Neural Network for Differential Diagnosis of Interstitial Lung Diseases: Pilot Study. Radiology 1990, 177, 857–860. [CrossRef]

- Food, U.S.; Administration, D. Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data: R2 Technologies (P970058) 1998.

- Gilbert Fiona J.; Astley Susan M.; Gillan Maureen G.C.; Agbaje Olorunsola F.; Wallis Matthew G.; James Jonathan; Boggis Caroline R.M.; Duffy Stephen W. Single Reading with Computer-Aided Detection for Screening Mammography. New England Journal of Medicine 2008, 359, 1675–1684. [CrossRef]

- Haralick, R.M.; Shanmugam, K.; Dinstein, I. Textural Features for Image Classification. IEEE Trans.Syst.Man Cybern. 1973, 3, 610 621. [CrossRef]

- Cavouras, D.; Prassopoulos, P. Computer Image Analysis of Brain CT Images for Discriminating Hypodense Cerebral Lesions in Children. Med Inform (Lond) 1994, 19, 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Anderson, A.R.; Gatenby, R.A.; Morse, D.L. The Biology Underlying Molecular Imaging in Oncology: From Genome to Anatome and Back Again. Clin.Radiol. 2010, 65, 517–521. [CrossRef]

- Proceedings of the 2010 World Molecular Imaging Congress, Kyoto, Japan, September 8-11, 2010. Molecular Imaging and Biology 2010, 12, 500–1636. [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.; Hausmann, M.; Lukasova, E.; Biswas, A.; Hildenbrand, G.; Davidkova, M.; Krasavin, E.; Kleibl, Z.; Falkova, I.; Jezkova, L.; et al. Determining Omics Spatiotemporal Dimensions Using Exciting New Nanoscopy Techniques to Assess Complex Cell Responses to DNA Damage: Part B--Structuromics. Crit.Rev.Eukaryot.Gene Expr. 2014, 24, 225–247.

- Avanzo, M.; Gagliardi, V.; Stancanello, J.; Blanck, O.; Pirrone, G.; El Naqa, I.; Revelant, A.; Sartor, G. Combining Computed Tomography and Biologically Effective Dose in Radiomics and Deep Learning Improves Prediction of Tumor Response to Robotic Lung Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy. Med Phys 2021, 48, 6257–6269. [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Kinahan, P.E.; Hricak, H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology 2016, 278, 563–577. [CrossRef]

- Avanzo, M.; Porzio, M.; Lorenzon, L.; Milan, L.; Sghedoni, R.; Russo, G.; Massafra, R.; Fanizzi, A.; Barucci, A.; Ardu, V.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Applications in Medical Imaging: A Review of the Medical Physics Research in Italy. Phys Med 2021, 83, 221–241. [CrossRef]

- Quartuccio, N.; Marrale, M.; Laudicella, R.; Alongi, P.; Siracusa, M.; Sturiale, L.; Arnone, G.; Cutaia, G.; Salvaggio, G.; Midiri, M.; et al. The Role of PET Radiomic Features in Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Clin Transl Imaging 2021, 9, 579–588. [CrossRef]

- Ubaldi, L.; Valenti, V.; Borgese, R.F.; Collura, G.; Fantacci, M.E.; Ferrera, G.; Iacoviello, G.; Abbate, B.F.; Laruina, F.; Tripoli, A.; et al. Strategies to Develop Radiomics and Machine Learning Models for Lung Cancer Stage and Histology Prediction Using Small Data Samples. Physica Medica 2021, 90, 13–22. [CrossRef]

- Pirrone, G.; Matrone, F.; Chiovati, P.; Manente, S.; Drigo, A.; Donofrio, A.; Cappelletto, C.; Borsatti, E.; Dassie, A.; Bortolus, R.; et al. Predicting Local Failure after Partial Prostate Re-Irradiation Using a Dosiomic-Based Machine Learning Model. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12, 1491. [CrossRef]

- Avanzo, M.; Stancanello, J.; Pirrone, G.; Sartor, G. Radiomics and Deep Learning in Lung Cancer. Strahlenther.Onkol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Peira, E.; Sensi, F.; Rei, L.; Gianeri, R.; Tortora, D.; Fiz, F.; Piccardo, A.; Bottoni, G.; Morana, G.; Chincarini, A. Towards an Automated Approach to the Semi-Quantification of [18F]F-DOPA PET in Pediatric-Type Diffuse Gliomas. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 2765. [CrossRef]

- Ubaldi, L.; Saponaro, S.; Giuliano, A.; Talamonti, C.; Retico, A. Deriving Quantitative Information from Multiparametric MRI via Radiomics: Evaluation of the Robustness and Predictive Value of Radiomic Features in the Discrimination of Low-Grade versus High-Grade Gliomas with Machine Learning. Physica Medica 2023, 107, 102538. [CrossRef]

- Traverso, A.; Wee, L.; Dekker, A.; Gillies, R. Repeatability and Reproducibility of Radiomic Features: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 2018, 102, 1143–1158. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Boser, B.; Denker, J.S.; Henderson, D.; Howard, R.E.; Hubbard, W.; Jackel, L.D. Backpropagation Applied to Handwritten Zip Code Recognition. Neural Computation 1989, 1, 541–551. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2014, 15, 1929–1958.

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc., 2012; Vol. 25.

- Reinke, A.; Tizabi, M.D.; Eisenmann, M.; Maier-Hein, L. Common Pitfalls and Recommendations for Grand Challenges in Medical Artificial Intelligence. Eur Urol Focus 2021, 7, 710–712. [CrossRef]

- Armato, S.G.; Drukker, K.; Hadjiiski, L. AI in Medical Imaging Grand Challenges: Translation from Competition to Research Benefit and Patient Care. British Journal of Radiology 2023, 96, 20221152. [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, I.; Rundo, L.; Codari, M.; Di Leo, G.; Salvatore, C.; Interlenghi, M.; Gallivanone, F.; Cozzi, A.; D’Amico, N.C.; Sardanelli, F. AI Applications to Medical Images: From Machine Learning to Deep Learning. Physica Medica 2021, 83, 9–24. [CrossRef]

- Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare | Nature Biomedical Engineering Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41551-018-0305-z (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Chan, H.-P.; Hadjiiski, L.M.; Samala, R.K. Computer-Aided Diagnosis in the Era of Deep Learning. Medical Physics 2020, 47, e218–e227. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H. AI-Based Computer-Aided Diagnosis (AI-CAD): The Latest Review to Read First. Radiol Phys Technol 2020, 13, 6–19. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.C.; Doi, K.; Giger, M.L. Detection of Lung Nodules in Digital Chest Radiographs Using Artificial Neural Networks: A Pilot Study. J Digit Imaging 1995, 8, 88–94. [CrossRef]

- Artificial Convolution Neural Network Techniques and Applications for Lung Nodule Detection - PubMed Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18215875/ (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Lo, S.-C.B.; Lin, J.-S.; M.d, M.T.F.; Mun, S.K. Computer-Assisted Diagnosis of Lung Nodule Detection Using Artificial Convoultion Neural Network. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 1993: Image Processing; SPIE, September 14 1993; Vol. 1898, pp. 859–869.

- Chan, H.P.; Lo, S.C.; Sahiner, B.; Lam, K.L.; Helvie, M.A. Computer-Aided Detection of Mammographic Microcalcifications: Pattern Recognition with an Artificial Neural Network. Med Phys 1995, 22, 1555–1567. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.K.; Greenspan, H.; Davatzikos, C.; Duncan, J.S.; Van Ginneken, B.; Madabhushi, A.; Prince, J.L.; Rueckert, D.; Summers, R.M. A Review of Deep Learning in Medical Imaging: Imaging Traits, Technology Trends, Case Studies With Progress Highlights, and Future Promises. Proceedings of the IEEE 2021, 109, 820–838. [CrossRef]

- Kaul, V.; Enslin, S.; Gross, S.A. History of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2020, 92, 807–812. [CrossRef]

- Lipkova, J.; Chen, R.J.; Chen, B.; Lu, M.Y.; Barbieri, M.; Shao, D.; Vaidya, A.J.; Chen, C.; Zhuang, L.; Williamson, D.F.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for Multimodal Data Integration in Oncology. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 1095–1110. [CrossRef]

- Fazal, M.I.; Patel, M.E.; Tye, J.; Gupta, Y. The Past, Present and Future Role of Artificial Intelligence in Imaging. European Journal of Radiology 2018, 105, 246–250. [CrossRef]

- Dembrower, K.; Crippa, A.; Colón, E.; Eklund, M.; Strand, F. Artificial Intelligence for Breast Cancer Detection in Screening Mammography in Sweden: A Prospective, Population-Based, Paired-Reader, Non-Inferiority Study. The Lancet Digital Health 2023, 5, e703–e711. [CrossRef]

- Eixelberger, T.; Wolkenstein, G.; Hackner, R.; Bruns, V.; Mühldorfer, S.; Geissler, U.; Belle, S.; Wittenberg, T. YOLO Networks for Polyp Detection: A Human-in-the-Loop Training Approach. Current Directions in Biomedical Engineering 2022, 8, 277–280. [CrossRef]

- Ragab, M.G.; Abdulkadir, S.J.; Muneer, A.; Alqushaibi, A.; Sumiea, E.H.; Qureshi, R.; Al-Selwi, S.M.; Alhussian, H. A Comprehensive Systematic Review of YOLO for Medical Object Detection (2018 to 2023). IEEE Access 2024, 12, 57815–57836. [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Mu, G.; Shen, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, W.; An, P.; Huang, X.; et al. Detection of Colorectal Adenomas with a Real-Time Computer-Aided System (ENDOANGEL): A Randomised Controlled Study. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2020, 5, 352–361. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.; Salomon, G. Transfer Of Learning. 1999, 11.

- Kim, H.E.; Cosa-Linan, A.; Santhanam, N.; Jannesari, M.; Maros, M.E.; Ganslandt, T. Transfer Learning for Medical Image Classification: A Literature Review. BMC Medical Imaging 2022, 22, 69. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, K.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.; Wang, D. A Survey of Transfer Learning. Journal of Big Data 2016, 3, 9. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, M.; Gore, J.C.; Adams, W.J. Toward an Automated Analysis System for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Imaging. II. Initial Segmentation Algorithm. Med Phys 1986, 13, 293–297. [CrossRef]

- Bezdek, J.C.; Hall, L.O.; Clarke, L.P. Review of MR Image Segmentation Techniques Using Pattern Recognition. Med Phys 1993, 20, 1033–1048. [CrossRef]

- Comelli, A.; Stefano, A.; Russo, G.; Bignardi, S.; Sabini, M.G.; Petrucci, G.; Ippolito, M.; Yezzi, A. K-Nearest Neighbor Driving Active Contours to Delineate Biological Tumor Volumes. Eng Appl Artif Intell 2019, 81, 133–144. [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation.; Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W.M., Frangi, A.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 234–241.

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention U-Net: Learning Where to Look for the Pancreas 2018.

- Lizzi, F.; Agosti, A.; Brero, F.; Cabini, R.F.; Fantacci, M.E.; Figini, S.; Lascialfari, A.; Laruina, F.; Oliva, P.; Piffer, S.; et al. Quantification of Pulmonary Involvement in COVID-19 Pneumonia by Means of a Cascade of Two U-Nets: Training and Assessment on Multiple Datasets Using Different Annotation Criteria. Int J CARS 2022, 17, 229–237. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, H.; Qi, X.; Dou, Q.; Fu, C.-W.; Heng, P.A. H-DenseUNet: Hybrid Densely Connected UNet for Liver and Tumor Segmentation from CT Volumes 2018.

- Khaled, R.; Vidal, J.; Vilanova, J.C.; Martí, R. A U-Net Ensemble for Breast Lesion Segmentation in DCE MRI. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 140, 105093. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Oghli, M.G.; Alizadehasl, A.; Shiri, I.; Oveisi, N.; Oveisi, M.; Maleki, M.; Dhooge, J. MFP-Unet: A Novel Deep Learning Based Approach for Left Ventricle Segmentation in Echocardiography. Physica Medica 2019, 67, 58–69. [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Walia, E.; Babyn, P. Generative Adversarial Network in Medical Imaging: A Review. Med Image Anal 2019, 58, 101552. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Wang, L.; Gupta, S.; Goli, H.; Padmanabhan, P.; Gulyás, B. 3D Deep Learning on Medical Images: A Review. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20, 5097. [CrossRef]

- Çiçek, Ö.; Abdulkadir, A.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2016; Ourselin, S., Joskowicz, L., Sabuncu, M.R., Unal, G., Wells, W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 424–432.

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc., 2014; Vol. 27.

- Shavlokhova, V.; Vollmer, A.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Vollmer, M.; Wollborn, J.; Lang, G.; Kübler, A.; Hartmann, S.; Stoll, C.; Roider, E.; et al. Finetuning of GLIDE Stable Diffusion Model for AI-Based Text-Conditional Image Synthesis of Dermoscopic Images. Frontiers in Medicine 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Toda, R.; Teramoto, A.; Tsujimoto, M.; Toyama, H.; Imaizumi, K.; Saito, K.; Fujita, H. Synthetic CT Image Generation of Shape-Controlled Lung Cancer Using Semi-Conditional InfoGAN and Its Applicability for Type Classification. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg 2021, 16, 241–251. [CrossRef]

- A Review of Medical Image Data Augmentation Techniques for Deep Learning Applications - Chlap - 2021 - Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Oncology - Wiley Online Library Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1754-9485.13261 (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Wolterink, J.M.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Leiner, T.; Vogl, T.J.; Bucher, A.M.; Išgum, I. Generative Adversarial Networks: A Primer for Radiologists. RadioGraphics 2021, 41, 840–857. [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.N.; Falcone, G.J.; Rajpurkar, P.; Topol, E.J. Multimodal Biomedical AI. Nat Med 2022, 28, 1773–1784. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Shan, H.; Teng, Y.; Tu, N.; Li, M.; Liang, G.; Wang, G.; Wang, S. Parameter-Transferred Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network (PT-WGAN) for Low-Dose PET Image Denoising. IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences 2021, 5, 213–223. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. A Review of Deep Learning-Based Approaches for Attenuation Correction in Positron Emission Tomography. IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences 2020, PP, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhu, A.H.; Maiti, P.; Thomopoulos, S.I.; Gadewar, S.; Chai, Y.; Kim, H.; Jahanshad, N.; Initiative, for the A.D.N. Style Transfer Generative Adversarial Networks to Harmonize Multisite MRI to a Single Reference Image to Avoid Overcorrection. Human Brain Mapping 2023, 44, 4875–4892. [CrossRef]

- Eo, T.; Jun, Y.; Kim, T.; Jang, J.; Lee, H.-J.; Hwang, D. KIKI-Net: Cross-Domain Convolutional Neural Networks for Reconstructing Undersampled Magnetic Resonance Images. Magn Reson Med 2018, 80, 2188–2201. [CrossRef]

- Fourcade, C.; Ferrer, L.; Moreau, N.; Santini, G.; Brennan, A.; Rousseau, C.; Lacombe, M.; Fleury, V.; Colombié, M.; Jézéquel, P.; et al. Deformable Image Registration with Deep Network Priors: A Study on Longitudinal PET Images. Phys Med Biol 2022, 67. [CrossRef]

- Sloan, J.M.; Goatman, K.A.; Siebert, J.P. Learning Rigid Image Registration - Utilizing Convolutional Neural Networks for Medical Image Registration.; August 25 2022; pp. 89–99.

- Zhao, X.; Yang, T.; Li, B. A Review on Generative Based Methods for MRI Reconstruction. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2022, 2330, 012002. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Takikawa, T.; Saito, S.; Litany, O.; Yan, S.; Khan, N.; Tombari, F.; Tompkin, J.; Sitzmann, V.; Sridhar, S. Neural Fields in Visual Computing and Beyond 2022.

- He, K.; Gan, C.; Li, Z.; Rekik, I.; Yin, Z.; Ji, W.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Shen, D. Transformers in Medical Image Analysis. Intelligent Medicine 2023, 3, 59–78. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, M.; Hu, S. TCGAN: A Transformer-Enhanced GAN for PET Synthetic CT. Biomed. Opt. Express, BOE 2022, 13, 6003–6018. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [CrossRef]

- Gers, F.A.; Schmidhuber, J.; Cummins, F. Learning to Forget: Continual Prediction with LSTM. Neural Comput 2000, 12, 2451–2471. [CrossRef]

- Greff, K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Koutník, J.; Steunebrink, B.R.; Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A Search Space Odyssey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learning Syst. 2017, 28, 2222–2232. [CrossRef]

- Steinkamp, J.; Cook, T.S. Basic Artificial Intelligence Techniques: Natural Language Processing of Radiology Reports. Radiologic Clinics of North America 2021, 59, 919–931. [CrossRef]