Submitted:

30 September 2024

Posted:

01 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Secure Multiparty Computation

2.1.1. Universal Composability

2.1.2. Arithmetic Black Box

2.1.3. Sharmind Protocols Set

2.2. Graphs

2.2.1. Shortest Path

2.3. Bellman-Ford Protocols on Top of MPC

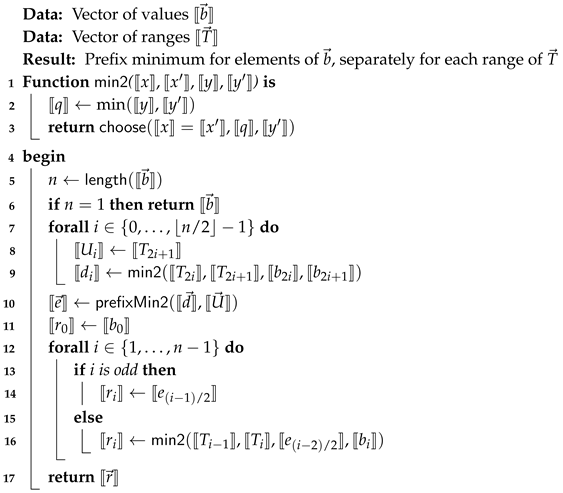

| Algorithm 1: Privacy-preserving Bellman-Ford, main program |

|

| Algorithm 2: PrefixMin2 (version 1) |

|

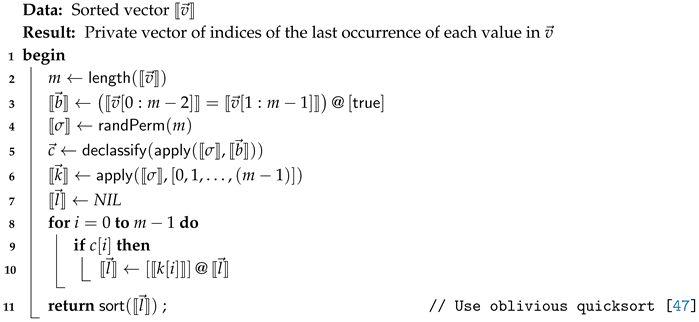

| Algorithm 3: GenIndicesVector |

|

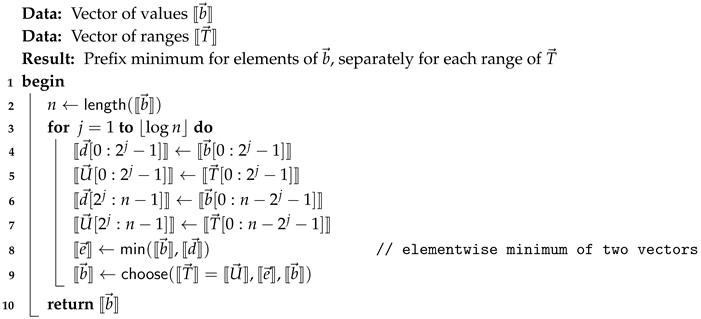

| Algorithm 4: prefixMin2 (version 2) |

|

3. Results

3.1. Security of Protocols Built on Top of ABB

- The input parameters, encompassing n (denoting the quantity of vertices) and s (indicating the source vertex).

- The handles to private values, identified within variables denoted as in the algorithm, regardless of whether these values manifest as individual elements, vectors, or an adjacency matrix.

- Declassified values, which may assume the form of integer values, individual elements, or complete vectors.

- In scenarios wherein the adversary assumes an active role, they gain insight into the ABB’s responses to efforts by the corrupted parties to deviate from the prescribed SSSD protocol.

3.2. Detailed Security Proof for Privacy-Preserving Bellman-Ford

- Arithmetic. The arithmetic operations, encompassing addition and multiplication, necessitate the provision of two handles, each corresponding to integers. Subsequently, these operations yield a handle to an integer, given that both input integers are private.

- Comparison. The comparison operations, encompassing "less than" (<), "less or equal than" (≤), "equal to" (==), and "not equal to" (≠), among others, necessitate two handles corresponding to integers (or floating-point values). These operations yield a handle to a Boolean value. It is worth noting that for the "equal to" (==) and "not equal to" (≠) operations, the input data may also include Boolean values.

- Logic. The logical operation on private vectors is employed using the "choose" function denoted as (, , ). It is imperative to note that , , and all represent vectors of handles. The outcome of this operation is a vector of handles, directing to elements within either or , contingent upon the specific values that the elements within point to. It is pertinent to mention that the data type of the vectors and can encompass integers, floating-point values, and Booleans, all of which are exclusively accessible via handles. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the results derived from the choose operation are exclusively of Boolean type, similarly accessible solely through handles.

- Declassification. This operation entails declassifying private data, making it publicly accessible. The input data for this operation comprises private integers denoted as —a vector of handles. The output, in turn, consists of a public vector of integers represented as x.

- Sorting. This operation takes private integers as input values, residing within vector . The operation’s outcome consists of sorted private integers stored in the private vector . The sorted vector comprises handles to values, reflecting the result of sorting the vector of values referenced by handles within .

- Random permutation. This operation is designed to generate a private permutation of n elements randomly. It takes a public integer n as input and yields a private permutation denoted as via a handle. Subsequently, this permutation can be applied to a private vector using the operation (,), resulting in a private vector . Specifically, for all i∈, . Furthermore, it is feasible to apply the inverse of to v using the operation (,).

- prepareRead and performRead. This operation facilitates the retrieval of data from a vector using a private index. The reading process involves the application of the performRead-operation, which takes two arguments: an integer vector of length n and a second argument derived from prepareRead(n, ), where represents the indices of the m elements intended for retrieval. Subsequently, this operation yields a private vector of length m via a handle. The length of corresponds to the first argument used in prepareRead, while the second argument of performRead is the output of prepareRead. It is crucial to note that if these conditions are not met, the behavior of may be arbitrary. The return value of the performRead-operation is a handle referencing a private vector of integers. The vector within the return value is denoted as , and each element is represented by = .

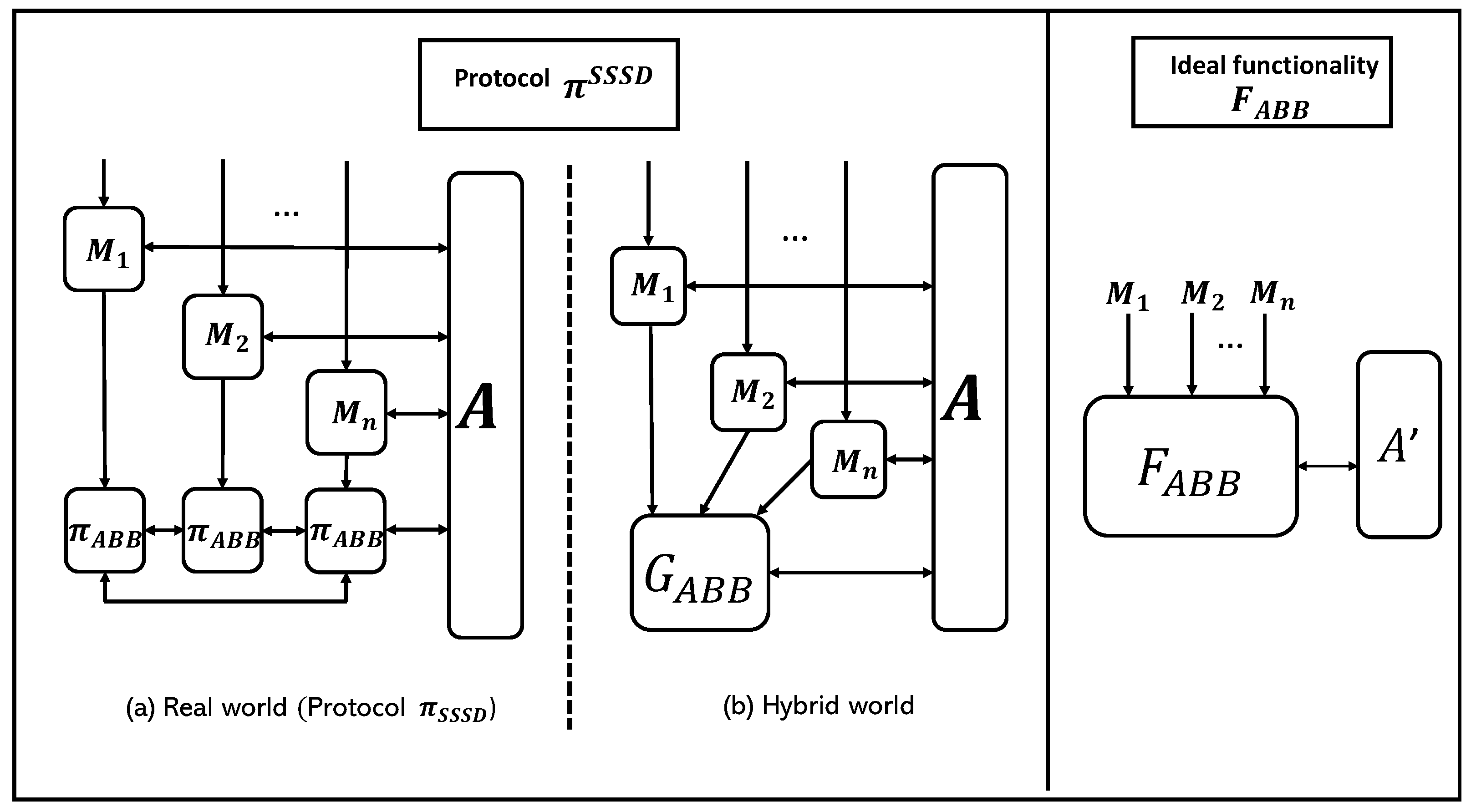

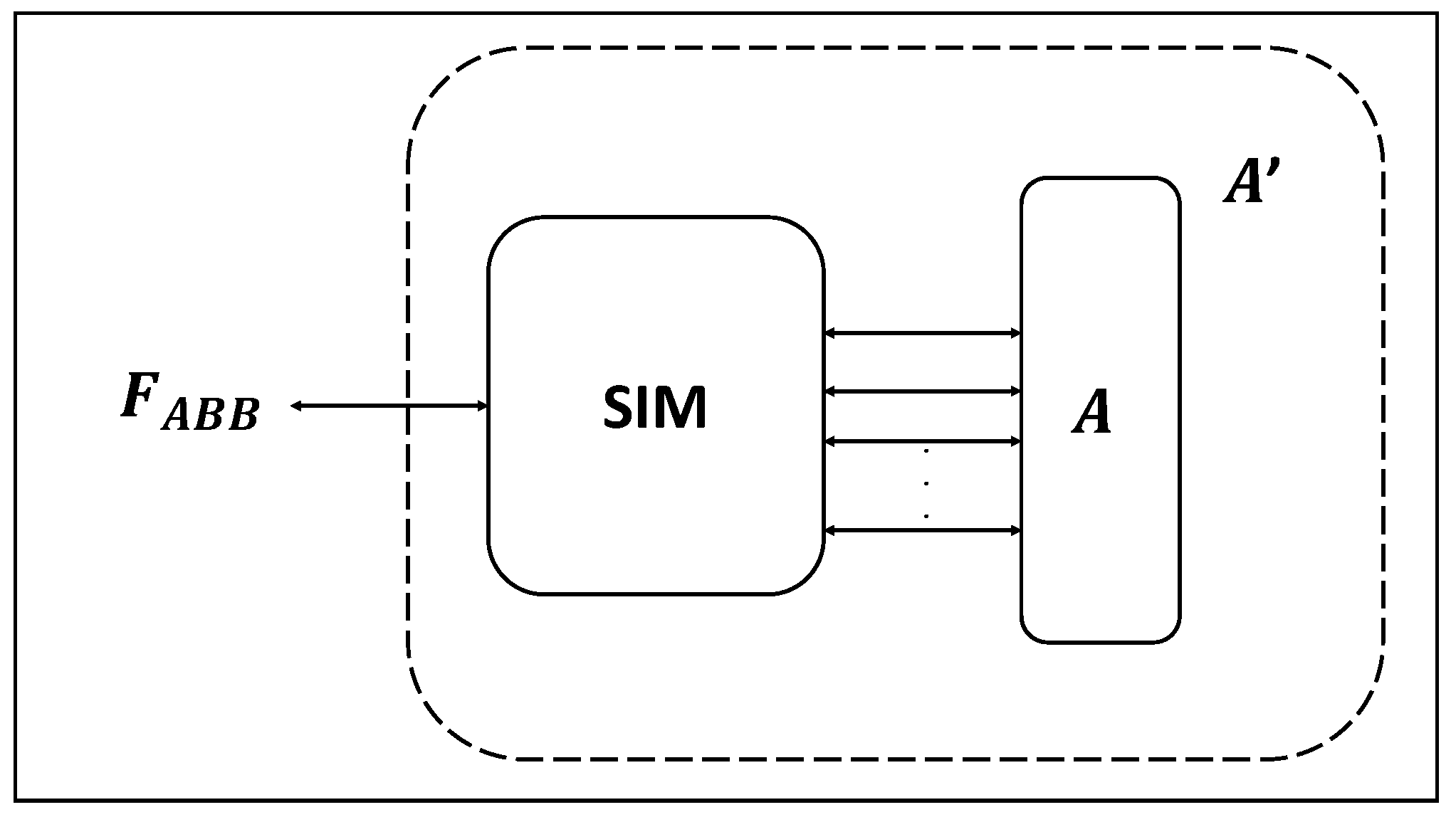

- Upon receiving inputs from all honest computing parties (, for ), these parties abstain from performing any computations themselves. Instead, their role involves exclusively providing inputs to and receiving outputs from either the machines ,…, or the ideal functionality . In the context of the SSSD operation facilitated by Bellman-Ford and supported by , when all honest parties collectively initiate the SSSD operation, they do so with specified arguments: , , , s, and N. Here, and represent the locations of the edges, signifies the weights of said edges, s denotes the source vertex, and N corresponds to the total number of vertices. Subsequently, completes the SSSD computation and furnishes the outcome as a vector of handles to each participating computing party. These handles serve as pointers to the shortest distances from the source vertex s. Notably, the length of the returned vector is equal to N. It is essential to highlight that the ideal functionality maintains ongoing communication with the adversary , ensuring they are apprised of the ongoing computations, as elaborated in Sec Section 2.1.2.

- Upon completion of their computations, each honest computing party transmits their respective SSSD results to the corresponding party . These results manifest as a vector denoting the shortest distances from the single source vertex s to all vertices, represented as .

- If the command is non-SSSD in nature, relays it to as a message that came from .

- If the command originates from to and pertains to SSSD, then relays an SSSD command from each machine to to the adversary . Additionally, sends a series of commands to , as if they came from . These commands correspond to the commands that receives in order to run the Algorithms 1–3.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SMC | Secure multi-party computation |

| SSSD | Single-source shortest distance |

| SIMD | Single-instruction-Multiple-data |

| BFS | Breadth-first search |

| APC | Algebraic Path Computation |

| UC | Universal Composability |

| ABB | Arithmetic Black Box |

References

- Bogdanov, D., Laur, S., & Willemson, J. Sharemind: A framework for fast privacy-preserving computations. In Computer Security-ESORICS 2008: 13th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Málaga, Spain, October 6-8, 2008. Proceedings 13. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 192-206.

- Bogdanov, D., Niitsoo, M., Toft, T., & Willemson, J.: High-performance secure multi-party computation for data mining applications. International Journal of Information Security, 2012, 11, pp. 403-418.

- Bogdanov, D., Jagomägis, R., & Laur, S.: A universal toolkit for cryptographically secure privacy-preserving data mining. In Pacific-asia workshop on intelligence and security informatics, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012, pp. 112-126.

- Ostrak, A., Randmets, J., Sokk, V., Laur, S., & Kamm, L.: Implementing Privacy-Preserving Genotype Analysis with Consideration for Population Stratification.Cryptography 2021 5, 3.

- Kamm, L., Bogdanov, D., Laur, S., & Vilo, J.: A new way to protect privacy in large-scale genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics, 2013 29(7), pp. 886-893.

- Anagreh, M., Vainikko, E., & Laud, P.: Parallel Privacy-preserving Computation of Minimum Spanning Trees. In ICISSP, 2021, pp. 181-190.

- Anagreh, M., Laud, P., & Vainikko, E.: Privacy-Preserving Parallel Computation of Minimum Spanning Forest. SN Computer Science, 2022 3(6), p.448.

- Pankova, A., & Jääger, J.: Short Paper: secure multiparty logic programming. In Proceedings of the 15th Workshop on Programming Languages and Analysis for Security, 2020, pp.3-7.

- Jääger, J., & Pankova, A.: PrivaLog: a privacy-aware logic programming language. In 23rd International Symposium on Principles and Practice of Declarative Programming, 2021, pp.1-14.

- Bogdanov, D., Kamm, L., Kubo, B., Rebane, R., Sokk, V., & Talviste, R.: Students and taxes: a privacy-preserving social study using secure computation. Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2015.

- Bogdanov, D., Kamm, L., Laur, S., Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt, P., Talviste, R., & Willemson, J.: Privacy-preserving statistical data analysis on federated databases. In Privacy Technologies and Policy: Second Annual Privacy Forum, APF 2014, Athens, Greece, May 20-21, 2014. Proceedings 2, Springer International Publishing, 2014, pp.30-55.

- Anagreh, M., Laud, P., & Vainikko, E.: Parallel privacy-preserving shortest path algorithms. Cryptography, 2021 5(4), p.27.

- Anagreh, M., Vainikko, E., & Laud, P.: Parallel privacy-preserving shortest paths by radius-stepping. In 2021 29th Euromicro International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Network-Based Processing (PDP), 2021, pp.276-280. IEEE.

- Anagreh, M., Laud, P., & Vainikko, E.: Privacy-preserving Parallel Computation of Shortest Path Algorithms with Low Round Complexity. In ICISSP, 2022, pp.37-47.

- Anagreh, M., Laud, P.: A Parallel Privacy-Preserving Shortest Path Protocol from a Path Algebra Problem. The 17th International Workshop on Data Privacy Management (DPM 2022), DPM 2022/CBT, 2022, LNCS 13619, 2023, pp.1–16.

- Bogdanov D, Laud P, Randmets J.: Domain-polymorphic programming of privacy-preserving applications. In: Proceedings of the Ninth Workshop on Programming Languages and Analysis for Security, 2014, pp. 53–65.

- Laud, P.: Parallel Oblivious Array Access for Secure Multiparty Computation and Privacy-Preserving Minimum Spanning Trees. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol.,(2), 2015, pp.188-205.

- Laud, P.: Stateful abstractions of secure multiparty computation. Applications of secure multiparty computation, 13, 2015, pp.26-42.

- Canetti, R.: Security and composition of multiparty cryptographic protocols. Journal of CRYPTOLOGY, 2000 13, pp.143-202.

- Laur, S., & Pullonen-Raudvere, P.: Foundations of programmable secure computation. Cryptography, 2021, 5(3), p.22.

- Damgård, I., Pastro, V., Smart, N., & Zakarias, S.: Multiparty computation from somewhat homomorphic encryption. In Annual Cryptology Conference. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012, pp.643-662.

- Yamada, T.: A mini–max spanning forest approach to the political districting problem. International Journal of Systems Science, 2009 40(5), pp.471-477.

- Cramer, R., & Damgård, I. B.: Secure multiparty computation. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Yao, A. C.: Protocols for secure computations. In 23rd annual symposium on foundations of computer science (sfcs 1982), 1982, pp.160-164, IEEE.

- Chaum, D., Crépeau, C., & Damgard, I.: Multiparty unconditionally secure protocols. In Proceedings of the twentieth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, 1988, pp. 11-19.

- Goldreich, O., Micali, S., & Wigderson, A.: How to play any mental game, or a completeness theorem for protocols with honest majority. In Providing Sound Foundations for Cryptography: On the Work of Shafi Goldwasser and Silvio Micali, 2019, pp. 307-328.

- Damgård, I., & Nielsen, J. B. (2003, August). Universally composable efficient multiparty computation from threshold homomorphic encryption. In Annual international cryptology conference, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2003, pp.247-264.

- Henecka, W., K ögl, S., Sadeghi, A. R., Schneider, T., & Wehrenberg, I.: TASTY: tool for automating secure two-party computations. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2010, pp.451-462.

- Gennaro, R., Rabin, M. O., & Rabin, T.: Simplified VSS and fast-track multiparty computations with applications to threshold cryptography. In Proceedings of the seventeenth annual ACM symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing, 1998, pp.101-111.

- Burkhart, M., Strasser, M., Many, D., & Dimitropoulos, X.: SEPIA:Privacy-Preserving Aggregation of Multi-Domain Network Events and Statistics. In 19th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 10), 2010.

- Damgård, I., Geisler, M., Krøigaard, M., & Nielsen, J. B.: Asynchronous multiparty computation: Theory and implementation. In International workshop on public key cryptography. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2009, pp.160-179.

- Pankova, A.: Efficient multiparty computation secure against covert and active adversaries. In: Ph.D. dissertation, University of Tart, Tart-Estonia, 2017.

- Canetti, R.: Universally composable security: A new paradigm for cryptographic protocols. In Proceedings 42nd IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 2001, pp.136-145. IEEE.

- West, D. B.: Introduction to graph theory (Vol. 2). Upper Saddle River: Prentice hall, 2001.

- Bollobás, B.: Modern graph theory (Vol. 184). Springer Science & Business Media, 1998.

- Cormen, T. H., Leiserson, C. E., Rivest, R. L., & Stein, C.: Introduction to algorithms. MIT press, 2022.

- Batchelor, G. K.: Heat transfer by free convection across a closed cavity between vertical boundaries at different temperatures. Quarterly of Applied Mathematics, 1954, 12(3), pp.209-233.

- Dijkstra, E. W.: A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. In Edsger Wybe Dijkstra: His Life, Work, and Legacy, 2022, pp.287-290.

- Thorup, M.: Integer priority queues with decrease key in constant time and the single source shortest paths problem. In Proceedings of the thirty-fifth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, 2003, pp.149-158.

- Meyer, U., & Sanders, P. (2003). δ-stepping: a parallelizable shortest path algorithm. Journal of Algorithms, 2003 49(1), pp.114-152.

- Blelloch, G. E., Gu, Y., Sun, Y., & Tangwongsan, K.: Parallel shortest paths using radius stepping. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM Symposium on Parallelism in Algorithms and Architectures, 2016, pp.443-454.

- Fink, E.: A survey of sequential and systolic algorithms for the algebraic path problem, 1992.

- Ladner, R. E., & Fischer, M. J.: Parallel prefix computation. Journal of the ACM (JACM), 1980, 27(4), pp.831-838.

- Hillis, W. D., & Steele Jr, G. L.: Data parallel algorithms. Communications of the ACM, 1986, 29(12), pp.1170-1183.

- Anagreh, M. Privacy-preserving parallel computations for graph problems. In: Ph.D. dissertation, University of Tartu, Tartu-Estonia, 2023.

- Riivo T.: Applying secure multi-party computation in practice. In: Ph.D. dissertation, University of Tartu, Tartu-Estonia, 2016.

- Bogdanov, D., Laur, S., & Talviste, R.: A practical analysis of oblivious sorting algorithms for secure multi-party computation. In Nordic Conference on Secure IT Systems. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2014, pp.59-74.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).