Submitted:

30 September 2024

Posted:

01 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

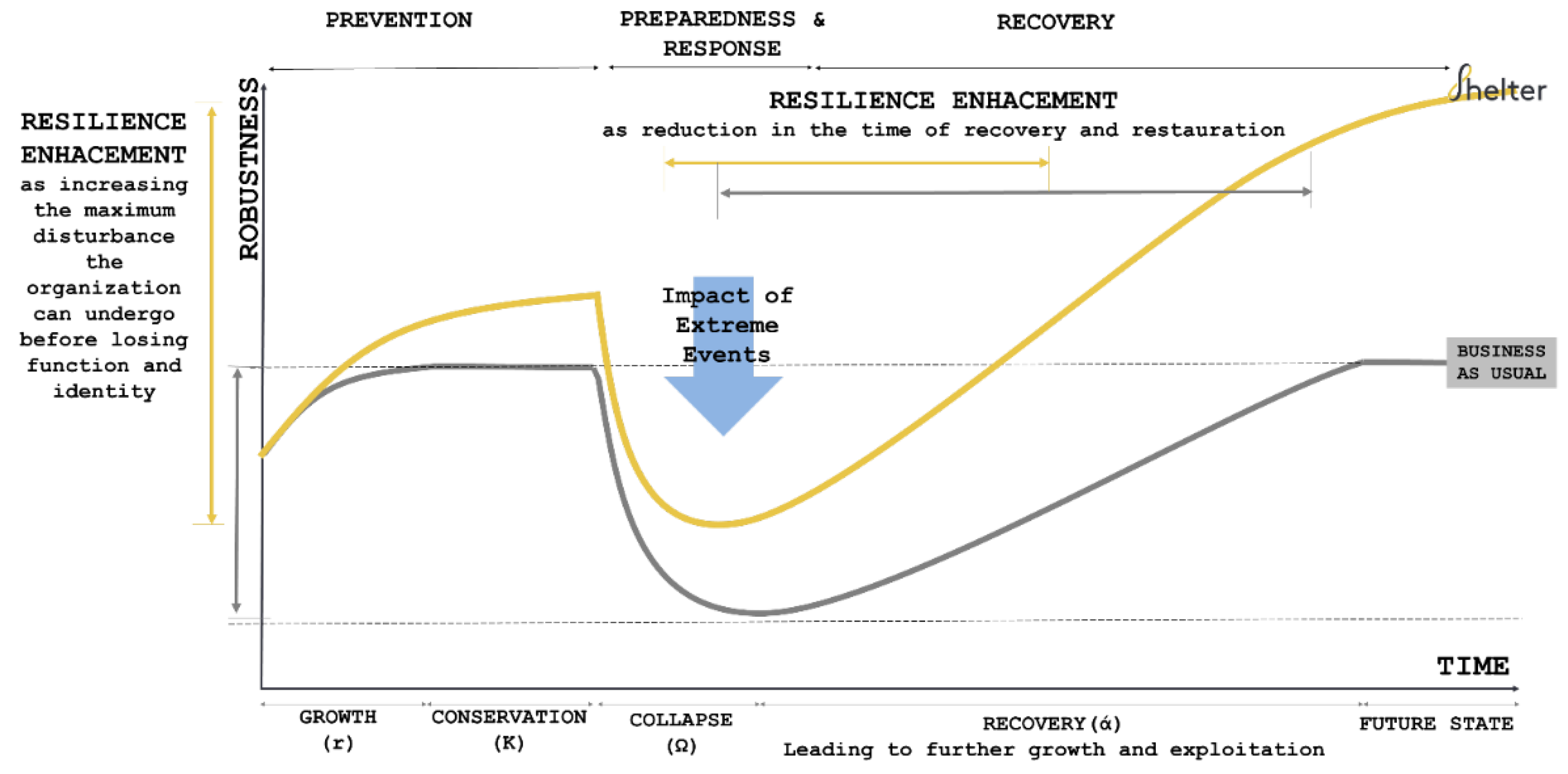

Resilience, initially a concept rooted in psychology, has traversed disciplinary boundaries, finding application in fields such as urban planning and development since the 2010s. Despite its broad application, most definitions remain too abstract to allow their practical integration into urban planning and development contexts. Addressing this challenge, the H2020 projects SHELTER and ARCH offer a practicable integration of resilience with planning and development practices surrounding urban heritage. Following a systemic approach to resilience, both projects integrate perspectives from urban development, climate change adaptation, disaster risk management, and heritage management, supported with tools and guidance to anchor resilience in existing practices. This paper presents the results from both projects, including similarities and differences.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| Concept | Sustainability | Resilience |

|---|---|---|

| Background | Forest Management. Example: 18th century Germany. | Psychological Resilience: the ability to bounce back from a stressful or adverse situation. Theoretical basis developed in the United States in the 1950s. |

| Objective | To maintain the overall natural resource base. | To make systems flexible enough to deal with changes without changing their principal character. |

| Definition: | Premise: Everything that we need for our survival and well-being depends, either directly or indirectly, on the natural environment. Process: To create and maintain the conditions under which humans and nature can exist in productive harmony, thereby enabling the fulfilment of the environmental, social, and economic requirements of present and future generations. | The ability of a system to respond flexibly to situational changes and negative factors without changing the essential state. |

| Type | Primarily linear | Dynamic system |

| Trend | To enable economic development without damaging the natural resource base. | To stimulate flexibility, adaptability, and risk-preparedness to deal with sudden or long-term changes. |

| Complexity | Fair | High |

| Level of Integration | Semi-integrated | Integrated |

| Parameters involved | Limited number | High number |

| Implementation | Management and Development Plans, management mechanisms, etc. | New governance models. Change of attitude and values. Empowering communities. Prioritization of cross-cutting topics, initiatives, and developments |

- Historic building environment resilience: How the historic building environment addresses disruption, affordable comfort, structural security through traditional techniques, vernacular architecture and built/unbuilt environment relationships and its relevance as container and management unit for other cultural heritage scales (as movable cultural heritage)

- Cultural resilience: How historic areas address social inclusion and support social and technical innovation through cultural identity, local knowledge, intangible cultural heritage, and openness to exploring novel pathways.

- Social resilience: How individual’s physical and psychological well-being are addressed within the historic area and strong and healthy personal relationships, connection to culture and nature and learning and sharing of new skills are enabled.

- Governance and institutional resilience: How links and partnerships are created and managed with support networks and across sectors (including public sector/government, research, and business)

- Economic resilience: How well the local and regional economic sectors can make use of competitive advantages as well as their ability to innovate, experiment, and restructure [70]

- Environmental resilience: How historic areas traditionally enhance biodiversity, cut carbon dependence and creates meaningful locally based livelihoods.

| Theme definition | Description of theme | Relationship to resilience | URBAN HERITAGE RESILIENCE DIMENSIONS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBR | CR | SR | GIR | ECR | ENR | ||||

| Social character | The social characteristics of the community. | Represents the social and demographic factors that influence the ability to prepare for and recover from a natural hazard event. | Gender, age, disability, health, household size and structure, language, literacy, education and employment influence abilities to build disaster resilience [71,72] | ||||||

| Social and community engagement | The capacity within communities to learn, adapt and transform. | Represents the social enablers within communities for engagement, learning, adaptation and transformation. | Cooperation and trust are essential to building disaster resilience and arise partly through social mechanisms including social capital [60,73] | ||||||

| Behavioral change has a social and cultural context [74,75] | |||||||||

| Community capital | The cohesion and connectedness of the community. | Represents the features of a community that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit. | Social networks assist community recovery following disaster [76] | ||||||

| Bonding, bridging and linking social capital can enhance solutions to collective action problems that arise following natural disasters [77] | |||||||||

| Economic capital | The economic characteristics of the community | Represents the economic factors that influence the ability to prepare for and recover from a natural hazard event. | Access to economic capital may be a barrier to resilience [78] | ||||||

| Economic capital often supports healthy social capital [72] | |||||||||

| Infrastructure and planning | The presence of legislation, plans, structures or codes to protect infrastructure and ensure service availability. | Represents preparation for natural hazard events using strategies of mitigation or planning or risk management. | Considered siting and planning of infrastructure is an important element of hazard mitigation. Multiple levels of government are involved in the planning process [79,80] | ||||||

| Planners can be agents of change in building disaster resilience [81] | |||||||||

| Emergency services | The presence of emergency services and disaster response plans. | Represents the potential to respond to a natural hazard event. | Emergency response capabilities and systems support resilience through the prevention, preparedness, response and recovery cycle [82] | ||||||

| Information and engagement | Availability and accessibility of natural hazard information and community engagement to encourage risk awareness. | Represents the relationship between communities and information, the uptake of information about risks and the knowledge required for preparation and self-reliance. | Emergency management community engagement comprises different approaches including information, participation, consultation, collaboration and empowerment. | ||||||

| Community engagement is a vehicle of public participation in decision making about natural hazards [83] | |||||||||

| Governance, policy and leadership | The capacity within government agencies to learn, adapt and transform. | Represents the flexibility within organizations to adaptively learn, review and adjust policies and procedures, or to transform organizational practices. | Effective response to natural hazard events can be facilitated by long term design efforts in public leadership [84,85] | ||||||

| Transformative adaptation requires altering fundamental value systems, regulatory or bureaucratic regimes associated with natural hazard management [86] | |||||||||

| Collaborative learning facilitates innovation and opportunity for feedback and iterative management [65,87] | |||||||||

| DIMENSION | Suggestions for operationalization | SINGULARITY |

|---|---|---|

| Historic building environment resilience | Including the physical vulnerability of the historic built environment as a nested concept for general resilience, vernacular architecture as catalyst of heritage-led resilience by capitalizing on its intrinsic characteristics, and considering the singularities of the built environment for conservation-friendly planning | Very High |

| Cultural resilience | Considering tangible and intangible cultural heritage as key driver in urban heritage resilience, fostering identity and sense of place, stimulating social cohesion through cultural activities and traditions, and safeguarding traditional knowledge and practices. Cultural diversity has the capacity to increase the resilience of social systems, since it is the result of centuries of slow adaptation to the hazards that affect local environments. | Very High |

| Social resilience | Considering social memory as key part of historic area resilience. Vulnerable groups (elderly, migrants, children, disabled) are specifically considered and the gender perspective is transversal. | High |

| Governance and institutional resilience | Adoption of adaptive governance approaches that include cross-departmental, cross-sectoral, and cross-scale collaboration, increased community participation, and collaboration with relevant external actors (e.g., NGOs) and special interest groups. | High |

| Economic resilience | Foster the innovation and competitive advantage of the local and regional economic sectors while making use of local materials and practices, valorising local knowledge of craftsmen and artisans, as well as incentivizing solutions from the local cultural sector. | Medium |

| Environmental resilience | Proposing circular approaches that reuse local materials and renewable resources and take advantage of the historic adaptation to local climate and circumstances. | Medium |

3.1. Urban Heritage Resilience in SHELTER and ARCH

| Resilience in SHELTER | Resilience in ARCH |

| “[T]he ability of a historic urban or territorial system-and all its social, cultural, economic, environmental dimensions across temporal and spatial scales to maintain or rapidly return to desired functions in the face of a disturbance, to adapt to change, and use it for a systemic transformation to still retain essentially the same function, structure and feedbacks, and therefore identity, that is, the capacity to adapt in order to maintain the same identity” | “The sustained ability of a historic area as a social-ecological system (including its social, cultural, political, economic, natural, and environmental dimensions) to cope with hazardous events by responding and adapting in socially just ways that maintain the historic area’s functions and heritage significance (including identity, integrity, and authenticity).” |

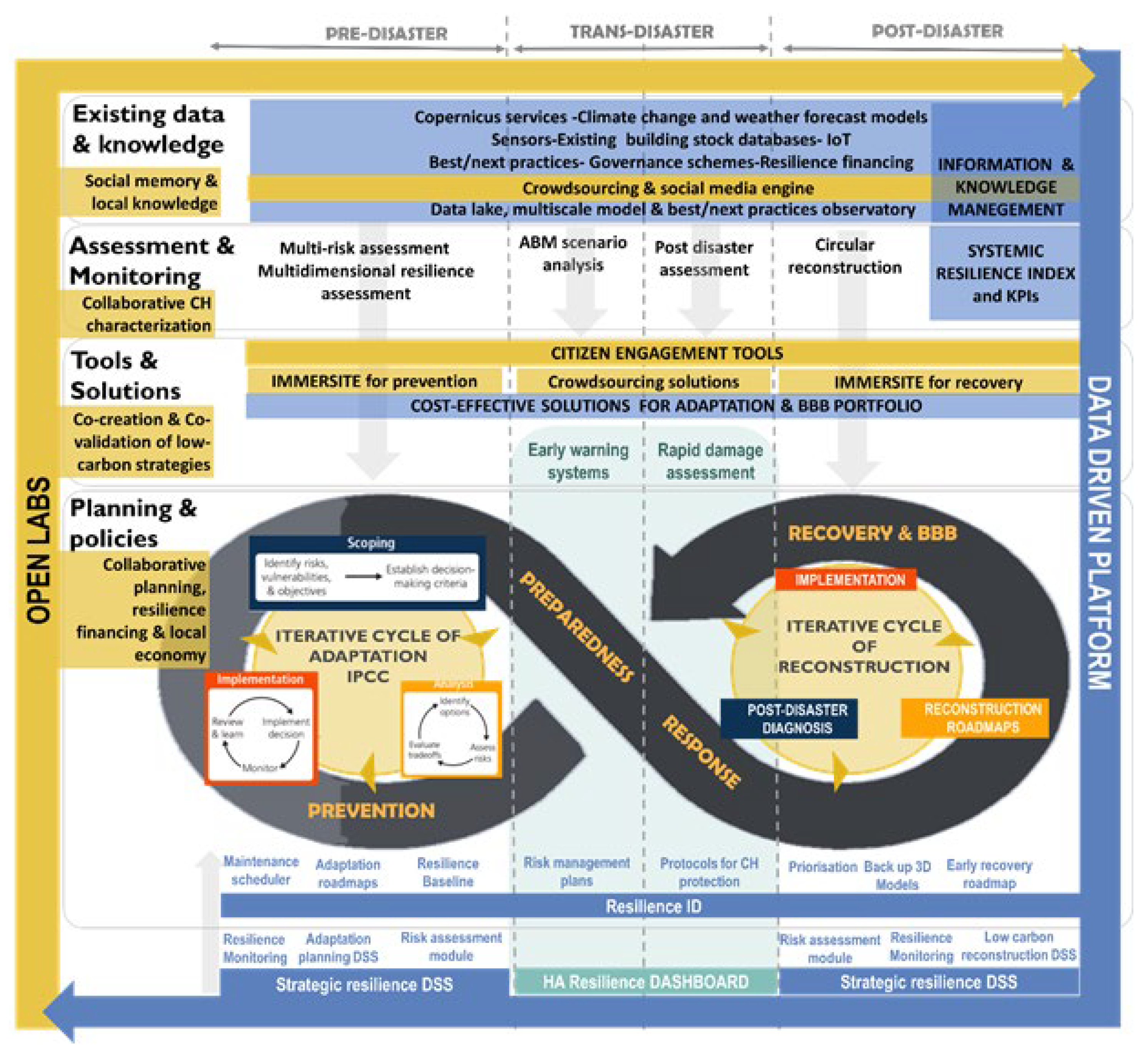

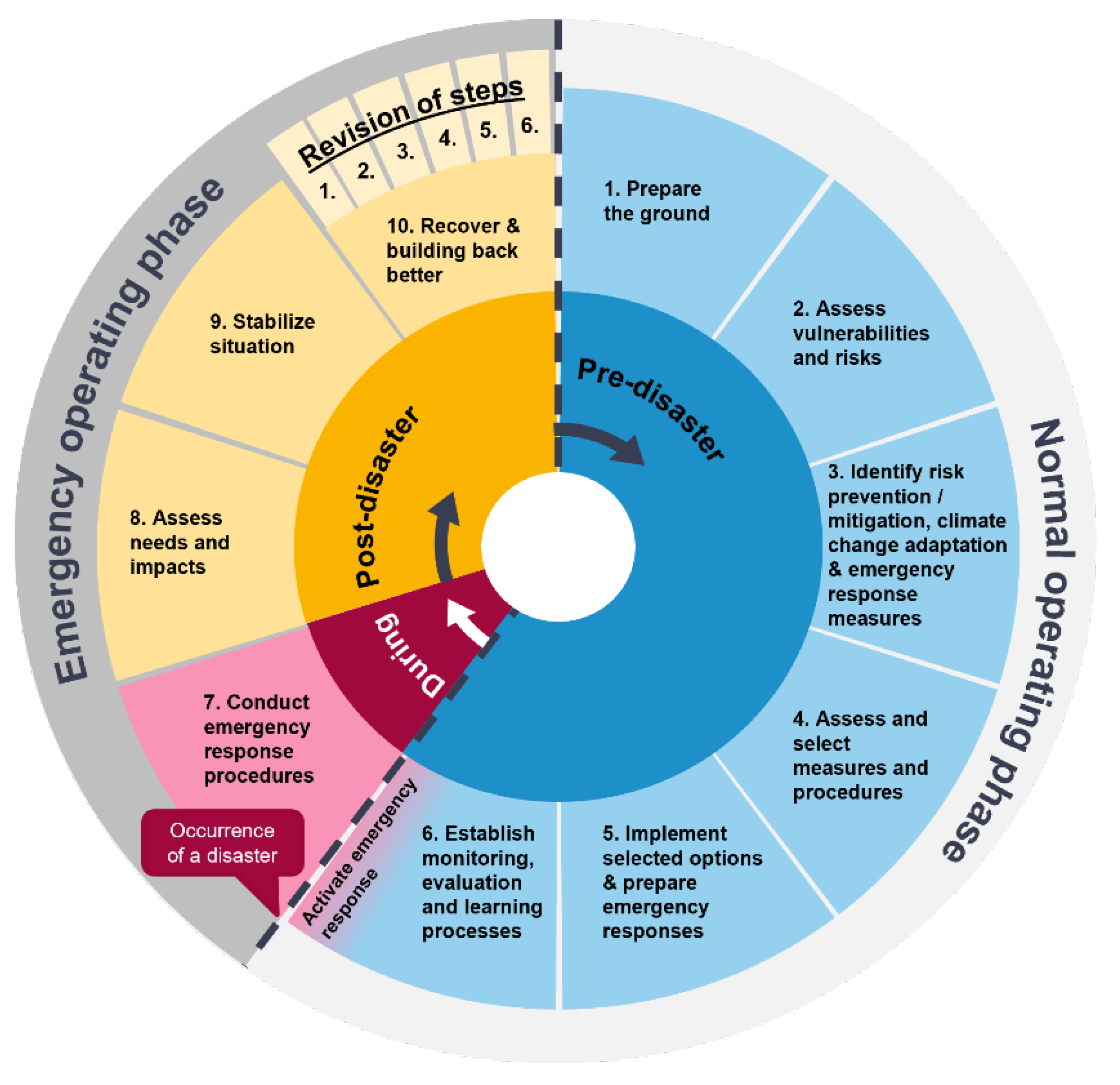

3.2. The SHELTER and ARCH Frameworks

- Proper data acquisition and management, system analysis and scenario definition, including the identification and integration of multiple data sources (satellite, sensors, crowdsourcing, predictive models, statistic models…) and existing knowledge (including local social memory regarding past events, best practices and results...) as the basis for any resilience building process.

- Risk and resilience assessments that include direct and indirect impacts of events on cultural assets (i.e., from physical damage and degradation of sites to socio-cultural, environmental and socio-economic dimensions) and consider sensitiveness, adaptive capacity as well as exposure to a specific or to a combination of multiple hazards.

- Identification and assessment of risk prevention, mitigation, climate change adaptation, and emergency response measures that take the need of urban heritage into account and allow for adaptive policy making.

- Decision-making based on adaptation pathways that can include conservation-friendly multifunctional solutions as the implementation of NBS and local solutions.

- Monitoring and learning processes, covering technical early warning systems as well as regular re-assessments and adaptation of plans, if necessary

3.3. Further operationalizing urban heritage resilience through dedicated tools

Information and Knowledge Management:

Risk and Resilience Assessment:

Strategic Decision Support

- The multi-risk assessment module for diagnosis and prioritisation (identifying “hot spots”) based on the multiscale data model and the data lake.

- A DSS for planning adaptation and building back better that will combine the information from the multi-risk module and the solutions portfolio.

3.4. Changing roles of Urban Cultural Heritage Throughout the Four Different Phases

| Shelter Concept Phase of Resilience | Potential Objectives | Potential Role of cultural heritage |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention | Avoid disaster and crisis | Context/ Element of the Scoping |

| Preparedness | Enhance Preparation for potential disaster and crisis | Asset to be protected |

| Response | Emergency Reactions | Resource |

| Recovery and BBB | Increase the Quality of life for local communities | Resource |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ripp, M. A Metamodel for Heritage-based Urban Development; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, C.; Ripp, M. A metamodel for heritage-based urban recovery. Built Heritage 2022, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Strange, I. Space and place in twentieth-century planning: An analytical framework and an historical review. Conceptions of Space and Place in Strategic Spatial Planning, 2008; 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations and, M. Latham, Habitat III: The new urban agenda, vol. 40, no. 2. 2017.

- European Commission, “Forging a climate-resilient Europe - the new EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change,” European Commission, vol. 6, no. 11, 2021.

- United Nations, “Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development United Nations United Nations Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” United Nations, 2015.

- Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe, “Deutsche Strategie zur Stärkung der Resilienz gegenüber Katastrophen,” 2023. Accessed: Aug. 31, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.bbk.bund.de/DE/Themen/Nationale-Kontaktstelle-Sendai-Rahmenwerk/Resilienzstrategie/resilienz-strategie_node.

- Zebrowski, C. Acting local, thinking global: Globalizing resilience through 100 Resilient Cities. New Perspect. 2020, 28, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR, “Making Cities Resilient 2030 (MCR2030).” Accessed: Aug. 31, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://mcr2030.undrr.

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, C.; Ripp, M. A metamodel for heritage-based urban recovery. Built Heritage 2022, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, K.; Bradley, J.M.; Baugh, D.E.; Jr. , C.W.C. Systems theory as a foundation for governance of complex systems. Int. J. Syst. Syst. Eng. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripp, M.; Daniel, S. Agility in Cultural Heritage Management—Advancing Competence Within Uncertainty as a Sustainable and Resilient Adaptation to Processes of Dynamic Change. Landsc. Arch. Front. 2023, 11, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. D. Hellige, “The metaphorical processes in the history of the resilience notion and the rise of the ecosystem resilience theory,” in Handbook on Resilience of Socio-Technical Systems, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Ripp and A. H. Lukat, “From Obstacle to Resource: How Built Cultural Heritage Can Contribute to Resilient Cities,” in Going Beyond, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 99–112. [CrossRef]

- Petzold, H.G.; Müller, L. Integrative Kinder- und Jugendlichenpsychotherapie: Protektive Faktoren und Resilienzen in der diagnostischen und therapeutischen Praxis. Psychother. Forum 2004, 12, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripp, M.; Rodwell, D. The governance of urban heritage. Hist. Environ. Policy Pr. 2016, 7, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.M. Understanding family resilience. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, A.; Rendall, S.; Reitsma, F. Resilient food systems: a qualitative tool for measuring food resilience. Urban Ecosyst. 2015, 19, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Peixoto, M. F. Peixoto, M. Wosnitza, J. Pipa, M. Morgan, and C. Cefai, “A multidimensional view on pre-service teacher resilience in Germany, Ireland, Malta and Portugal,” in Resilience in Education: Concepts, Contexts and Connections, 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Maguire and P. Hagan, “Disasters and communities: Understanding social resilience,” The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 22, no. 2, 2007.

- Newman, P.; Beatley, T.; Boyer, H. Resilient cities: Responsing to peak oil and climate change. Aust. Plan. 2009, 46, 59–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. S. & G. University. S. of A. E. S. Southwood, Mankind and ecosystems : perturbation and resilience -- the 1st Sabath Memorial Lecture held at Griffith University,. School of Australian Environmental Studies, Griffith University, 1983.

- Sharifi, A.; Chelleri, L.; Fox-Lent, C.; Grafakos, S.; Pathak, M.; Olazabal, M.; Moloney, S.; Yumagulova, L.; Yamagata, Y. Conceptualizing Dimensions and Characteristics of Urban Resilience: Insights from a Co-Design Process. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifdaloz, A. Regmi, J. M. Anderies, and A. A. Rodriguez. Robustness, vulnerability, and adaptive capacity in small-scale social- ecological systems: The Pumpa Irrigation System in Nepal. Ecology and Society 2010.

- C. Folke, S. R. C. Folke, S. R. Carpenter, B. Walker, M. Scheffer, T. Chapin, and J. Rockström, “Resilience Thinking : Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability,” vol. 15, no. 4, 2010.

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egusquiza, A.; Lückerath, D.; Zorita, S.; Silverton, S.; Garcia, G.; Servera, E.; Bonazza, A.; Garcia, I.; Kalis, A. Paving the Way for Climate Neutral and Resilient Historic Districts. Open Res. Eur. 2023, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Milde, D. K. Milde, D. Lückerath, and O. Ullrich, “D7.3 ARCH Disaster Risk Management Framework.,” 2020. Accessed: Aug. 31, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic? 0801. [Google Scholar]

- K. Milde, V. K. Milde, V. Wischott, D. Lückerath, S. Koslowski, and K. Wood, “D7.6 System design, realisation, and intergation,” 2022. Accessed: Aug. 31, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic? 0801. [Google Scholar]

- D. Lückerath, K. D. Lückerath, K. Milde, V. Wischott, and A. Klose, “The ARCH Resilience Assessment Dashboard: An Online Scorecard Approach to Assess the Resilience of Historic Areas,” in EGU General Assembly 2024, Vienna: EGU, 2024. Accessed: Aug. 31, 2024. [Online]. Available. [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future Towards Sustainable Development 2. Part II. Common Challenges Population and Human Resources 4. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- D. R. H. Morchain, “Background paper for Council of Europe’s report on Resilient Cities,” 2012. Accessed: Aug. 31, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://rm.coe. 1680.

- S. Labadi and W. Logan. Urban heritage, development and sustainability: International frameworks, national and local governance. [CrossRef]

- European Comission, “Toledo declaration. Informal ministerial meeting on urban development,” 2010.

- D. Sully, “Conservation Theory and Practice: Materials, Values, and People in Heritage Conservation,” in The International Handbooks of Museum Studies, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Luiten, E.; Renes, H.; Stegmeijer, E. Heritage as sector, factor and vector: conceptualizing the shifting relationship between heritage management and spatial planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1654–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Siravo, “Planning and Managing Historic Urban Landscapes,” in Reconnecting the City, Wiley, 2014, pp. 161–202. [CrossRef]

- Rosetti, I.; Cabral, C.B.; Roders, A.P.; Jacobs, M.; Albuquerque, R. Heritage and Sustainability: Regulating Participation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COUNCIL OF EUROPE, “Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society,” 2005.

- S. Gößling-Reisemann and T. Blöthe, “Low exergy solutions as a contribution to climate adapted and resilient power supply,” in Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Efficiency, Cost, Optimization and Simulation of Energy Conversion Systems and Processes, ECOS 2012, 2012.

- C. S. Holling, “Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems,” Annu Rev Ecol Syst, vol. 4, pp. 1–23, 1973, [Online]. Available: http://www.jstor. 2096.

- G. Fairclough, M. G. Fairclough, M. Dragićević-Šešić, L. Rogač-Mijatović, E. Auclair, and K. Soini, “THE FARO CONVENTION, A NEW PARADIGM FOR SOCIALLY -AND CULTURALLY -SUSTAINABLE HERITAGE ACTION?,” Culture, vol. 8, 2014.

- M. Ripp, “Heritage as a System and Process that Belongs to Local Communities Reframing the role of local communities and stakeholders,” 18. 20 May.

- Linnenluecke, M.; Griffiths, A. Beyond Adaptation: Resilience for Business in Light of Climate Change and Weather Extremes. Bus. Soc. 2010, 49, 477–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardekker, J.A.; de Jong, A.; Knoop, J.M.; van der Sluijs, J.P. Operationalising a resilience approach to adapting an urban delta to uncertain climate changes. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godschalk, D.R. Urban Hazard Mitigation: Creating Resilient Cities. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2003, 4, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaans, M.; Waterhout, B. Building up resilience in cities worldwide – Rotterdam as participant in the 100 Resilient Cities Programme. Cities 2017, 61, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.; Griffiths, A. Beyond Adaptation: Resilience for Business in Light of Climate Change and Weather Extremes. Bus. Soc. 2010, 49, 477–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardekker, J.A.; de Jong, A.; Knoop, J.M.; van der Sluijs, J.P. Operationalising a resilience approach to adapting an urban delta to uncertain climate changes. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaans, M.; Waterhout, B. Building up resilience in cities worldwide – Rotterdam as participant in the 100 Resilient Cities Programme. Cities 2017, 61, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godschalk, D.R. Urban Hazard Mitigation: Creating Resilient Cities. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2003, 4, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Ripp and A. H. Lukat (Translation), “From Obstacle to Resource: How Built Cultural Heritage Can Contribute to Resilient Cities,” in Going Beyond: Perceptions of Sustainability in Heritage Studies No. 2, M.-T. Albert, F. Bandarin, and A. Pereira Roders, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 99–112. [CrossRef]

- Brink, M.v.D.; Termeer, C.; Meijerink, S. Are Dutch water safety institutions prepared for climate change? J. Water Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Termeer, C.; Klostermann, J.; Meijerink, S.; van den Brink, M.; Jong, P.; Nooteboom, S.; Bergsma, E. The Adaptive Capacity Wheel: a method to assess the inherent characteristics of institutions to enable the adaptive capacity of society. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Glavac, S.; Hastings, P.; Marshall, G.; McGregor, J.; McNeill, J.; Morley, P.; Reeve, I.; Stayner, R. Top-down assessment of disaster resilience: A conceptual framework using coping and adaptive capacities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Berkes, C. J. Berkes, C. Folke, and Colding, Navigating Social-Ecological Systems Building Resilience For Complexity And Change. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Berkes, C. J. Berkes, C. Folke, and Colding, Navigating Social-Ecological Systems Building Resilience For Complexity And Change. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Glavac, S.; Hastings, P.; Marshall, G.; McGregor, J.; McNeill, J.; Morley, P.; Reeve, I.; Stayner, R. Top-down assessment of disaster resilience: A conceptual framework using coping and adaptive capacities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. S. Holing, “Understanding the Complexity of Economic, Ecological, and Social Systems,” Ecosystems, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 390–405, 2001. [CrossRef]

- B. Walker, D. B. Walker, D. Salt, and W. Reid, “Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in A Changing World,” Bibliovault OAI Repository, the University of Chicago Press, 2006.

- Brink, M.v.D.; Termeer, C.; Meijerink, S. Are Dutch water safety institutions prepared for climate change? J. Water Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Termeer, C.; Klostermann, J.; Meijerink, S.; van den Brink, M.; Jong, P.; Nooteboom, S.; Bergsma, E. The Adaptive Capacity Wheel: a method to assess the inherent characteristics of institutions to enable the adaptive capacity of society. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Ripp and A. H. Lukat (Translation), “From Obstacle to Resource: How Built Cultural Heritage Can Contribute to Resilient Cities,” in Going Beyond: Perceptions of Sustainability in Heritage Studies No. 2, M.-T. Albert, F. Bandarin, and A. Pereira Roders, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 99–112. [CrossRef]

- B. Walker, D. B. Walker, D. Salt, and W. Reid, “Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in A Changing World,” Bibliovault OAI Repository, the University of Chicago Press, 2006.

- A. Bonazza, I. A. Bonazza, I. Maxwell, M. Drdácký, E. Vintzileou, and C. Hanus, Safeguarding Cultural Heritage from Natural and Man-Made Disasters A comparative analysis of risk management in the EU. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Glavac, S.; Hastings, P.; Marshall, G.; McGregor, J.; McNeill, J.; Morley, P.; Reeve, I.; Stayner, R. Top-down assessment of disaster resilience: A conceptual framework using coping and adaptive capacities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmie, J.; Martin, R. The economic resilience of regions: Towards an evolutionary approach. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, B.H. Identifying and Mapping Community Vulnerability. Disasters 1999, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. S. K. Thomas, B. D. D. S. K. Thomas, B. D. Phillips, W. E. Lovekamp, and A. Fothergill, Social vulnerability to disasters. 2013. [CrossRef]

- B. E. Goldstein, “Collaborative Resilience-Moving Through Crisis to Opportunity (p. 376),” 2011, MIT Press.

- Dake, K. Myths of Nature: Culture and the Social Construction of Risk. J. Soc. Issues 1992, 48, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiser, J.R.; Bostrom, A.; Burton, I.; Johnston, D.M.; McClure, J.; Paton, D.; van der Pligt, J.; White, M.P. Risk interpretation and action: A conceptual framework for responses to natural hazards. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2012, 1, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, Y.; Chaplin, S.; Fairbrother, P. Role of social networks in community preparedness for bushfire. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2014, 5, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. P. Aldrich, Building resilience: Social capital in post-disaster recovery. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- D. Bird, D. D. Bird, D. King, K. Haynes, P. Box, T. Okada, and K. Nairn, Impact of the 2010-11 floods and the factors that inhibit and enable household adaptation strategies. National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility Gold Coast, 2013.

- Crompton, R.P.; McAneney, K.J.; Chen, K.; Pielke, R.A.; Haynes, K. Influence of Location, Population, and Climate on Building Damage and Fatalities due to Australian Bushfire: 1925–2009. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2010, 2, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D. Reducing hazard vulnerability through local government engagement and action. Nat. Hazards 2008, 47, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Smith. Planning for sustainable and disaster-resilient communities. In Hazards Analysis: Reducing the Impact of Disasters, Second Edition, 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. D. Haddow, J. A. G. D. Haddow, J. A. Bullock, and D. P. Coppola, Introduction to emergency management: Fifth Edition. 2013.

- Handmer, J.; Dovers, S. The Handbook of Disaster and Emergency Policies and Institutions; Taylor & Francis: London, United Kingdom, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, F. DESIGNING RESILIENCE – PREPARING FOR EXTREME EVENTS - edited by Louise K. Comfort, Arjen Boin and Chris C. Demchak. Public Adm. 2012, 90, 550–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Tierney, The social roots of risk: Producing disasters, promoting resilience. Stanford University Press, 2014.

- O’neill, S.J.; Handmer, J. Responding to bushfire risk: the need for transformative adaptation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 014018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Understanding uncertainty and reducing vulnerability: lessons from resilience thinking. Nat. Hazards 2007, 41, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. H. Gunderson and C. S. Holling, Panarchy: understanding transformations in systems of humans and nature. 2002.

- Walker, B.; Salt, D. Resilience Practice; Island Press: Washington DC, United States, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Stead, D. Understanding the notion of resilience in spatial planning: A case study of Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Cities 2013, 35, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Stead, D. Understanding the notion of resilience in spatial planning: A case study of Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Cities 2013, 35, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Jigyasu, J. R. Jigyasu, J. King, and G. Wijesuriya, “Managing disaster risk for world heritage,” 2010.

- Climate-ADAPT, ‘The Urban Adaptation Support Tool - Getting started,’” https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/knowledge/tools/urban-ast/step-0-0.

- Lindner, R.; Lückerath, D.; Milde, K.; Ullrich, O.; Maresch, S.; Peinhardt, K.; Latinos, V.; Hernantes, J.; Jaca, C. The Standardization Process as a Chance for Conceptual Refinement of a Disaster Risk Management Framework: The ARCH Project. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petutschnig, L.; Rome, E.; Lückerath, D.; Milde, K.; Swartling. G.; Aall, C.; Meyer, M.; Jordá, G.; Gobert, J.; Englund, M.; et al. Research advancements for impact chain based climate risk and vulnerability assessments. Front. Clim. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Villanueva-Merino, A. A. Villanueva-Merino, A. López-de-Aguileta-Benito, J. L. Izkara, and A. Egusquiza, “Spatial Decision Making for Improvement of the Resilience of the Historic Areas: SHELTER DSS,” pp. 384–395, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.; Graham, K. The importance of heritage preservation in natural disaster situations. Int. J. Risk Assess. Manag. 2007, 7, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Ripp, EARTH WIND WATER FIRE EARTH WIND WATER FIRE Environmental Challenges to Urban World Heritage Organization of World Heritage Cities (OWHC) Northwest-European Regional Conference in Regensburg from -18, 2008. 2017. 16 September.

- A. Egusquiza, A. A. Egusquiza, A. Gandini, and M. Zubiaga, “D.2.1. SHELTER: Historic Areas Resilience structure,” 2019. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: file:///C:/Users/106968/Downloads/D2.1.

- Egusquiza, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “D2.2 SHELTER: Historic Areas Systemic resilience assessment and monitoring framework,” 2020. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: file:///C:/Users/106968/Downloads/D2.2.

- Holtorf, C. Embracing change: how cultural resilience is increased through cultural heritage. World Archaeol. 2018, 50, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics of the notion of resilience | Literature | HERITAGE-LED RESILIENCE |

|---|---|---|

| Robustness Strength |

[25,46,47,48,49] | The survival of the historic cities until modern times shows the capacity of these environments to recover from past disasters. The social memory and local knowledge resulting of this history has to be gathered and operationalised. |

| Flexibility Adaptability Adaptive Capacity Learning capacity Autonomy Room for autonomous change Reflexivity |

[3,25,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] | Historic environments are results of evolution processes to adapt to the requirements of each epoch. The strategies to improve resilience must include and respect the result of these processes (local techniques, selection of materials and construction cultures) but they also need to learn from the flexibility and adaptability of changing conditions that create these results. |

| Living with uncertainty Social memory |

[57,58,59] | Generalised resilience requires to learn to live with uncertainty (“expecting the unexpected”) and to build a memory of past events to build the capability to learn from crisis and disasters. Long-enduring urban environments have developed adaptations to deal with these disturbances, using social memory as key part of the system resilience. |

| Self-organisation | [60,61,62] | During a significant part of their story, historic cities have been an example of urban self-organisation. Like nature’s cycles involving renewal and reorganization the resilience of a system is closely related to this capacity for self-organization. |

| Diversity Variety Inclusive Fair governance Collaboration Social capital |

[53,63,64] [52,61,65] | In ecological systems, diversity provides the conditions for new opportunities in the renewal cycle so the diversity of stakeholder’s partnership and arrangement already created around the heritage conservation can be used to bring diversity of views and considerations into the discussion expanding the role of information, education, and dialogue. |

| Cross-scale dynamic | [25,59] | Response to challenges as climate change and disasters require building cross-scale management capabilities, like the ones necessary for urban conservation. |

| Resourceful Efficiency |

[52,53,64,65,66] | Historic areas have shown effective ways to construct and design functional urban environments with local and durable materials. New resilience strategies should manage the changing process to keep this identity, considering issues such as maintenance, life cycle, durability and compatibility of the materials, local construction techniques…considering the singularity of cultural heritage’s physical vulnerability framed in a broader concept of multidimensional resilience |

| Intersectorality Integrated |

[52,66] | Urban conservation policies and strategies always required integrated visions to include all the needed competences. The improvement of resilience in historic areas is going to need to continue with this tradition and include new department and sectors in the decision making. |

| Innovation Combining different kinds of knowledge for learning Interdependence |

[53,61,67] | The cultural heritage field has always needed the combination of different kinds of knowledge. The focus on the complementarity of this knowledge can help to increase the capacity to learn. Climate change and urban conservation can be used as an example to illustrate the potential contributions of local and traditional knowledge. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).