Introduction

There is substantial literature indicating that forests and other locations with natural green features have the potential to induce calm, restoration, and recovery [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These findings have motivated the creation of “green healing spaces” in locations where they are typically lacking, such as in urban centers or hospitals. Such efforts are important in several settings including within the US Department of Defense (DoD), where this current study which quantifies the physiological impact of a purposely designed nature walk to reduce stress and promote healing was carried out at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center [

5,

6].

Green healing spaces are inviting, satisfying and desirable, but city and facilities planners face several tradeoffs and considerations when trying to maintain or allocate funding for such resources. Despite a growing body of research documenting enhanced mood in response to walking in green areas, the physiological mechanisms are less well-characterized [

3,

7,

8]. Obtaining quantitative data informing the mechanisms by which such spaces promote healing will provide additional support for implementation of such green spaces as adjuncts for improving health. Two mechanisms that have been proposed to mediate the beneficial effects of nature include impacts on autonomic nervous system (ANS) responses to natural elements, [

7] and processes that refresh and enhance attention.[

9,

10] Calming effects are detected through relative increases in parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity and decreases in sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity (e.g., slower heart rate and breathing). The measurement of heart rate variability (HRV) is one way to assess ANS activity directly in a non-invasive and continuous manner with minimal participant burden [

11,

12,

13]. HRV captures the interactions between the SNS and PNS cores of the ANS, with sympathetic leading to an increased HR due to stressors and parasympathetic related to reduced HR during periods of rest [

14].

Several studies in the past have shown an association between various HRV metrics and stress. A significant decrease was observed in RMSSD (Root mean square standard deviation) and SDNN (Standard deviation of NN values) time domain HRV metrics in university students before an examination vs during, indicating an association with stress condition [

14,

15]. RMSSD captures short term changes between successive RR beats which corelate with changes to the PNS core, while SDNN captures longer variability trends corelated to both SNS and PNS cores. As it is not always feasible to collect long-term 24 hour ECG recordings for HRV analysis in mobile settings and several studies have experimented with short-term (less than 60 seconds) ECG recordings. A study using ultra short term HRV recordings showed significant difference between rest and stressor (Stroop color test) for RMSSD and pNN50 (Percentage of NN intervals over 50ms) metrics when using a window size of 30 seconds [

16]. A comprehensive study on various HRV metrics versus the minimum window for identifying significant changes between rest and a TSST (Trier Social Stress Test) found a window size of 50 seconds for calculating time domain metrics - RMSSD, SDNN and AVNN (Average value of NN intervals) to be significant biomarkers to detect changes in mental stress [

17]. However, only a few studies have examined HRV in response to environmental manipulations, and these have provided mixed evidence relative to changes in PNS activity. In three laboratory studies, subjects were exposed to different virtual environments after a cognitive or social stressor. In two of the studies, which tested the environments using a virtual reality headset [

18] and wrap-around movie screen, [

19] changes in HRV did not significantly vary based on the virtual environment. Notably, in the third study, which tested four virtual environments using computer images, HRV (LF/HF ratio) was significantly lower in response to the artificial environment (“square space”) compared to the three natural/green environments (“natural open”, “under forest”, “tree-line linear”) [

20]. As the authors note, this effect might have been due to either the relaxing effect of the nature-conditions or the non-relaxing effect of the control condition (“square space”).

Four field experiments examined whether walking in a forest or green area increases HRV (High Frequency) relative to walking in an urban environment. In three of the studies, participants were immersed in a natural or urban environment for a brief amount of time (~ 30 minutes). In two of them – both from Japan – the natural environment was associated with increases in HRV, consistent with reduced stress and an enhanced relaxation response [

21,

22]. In the third study, from Denmark, both environments elicited similar increases in HRV, although the control condition was a historic town, and therefore might have had its own calming effect [

23]. By examining real locations, these studies likely increased their external validity; however, they did include lengthy transportation or baseline periods, likely simulating a mild stressor. In a more recent study, subjects walked once weekly, for three weeks, in one of two conditions – a green area or a suburban area [

24]. Following a two-week washout, they then switched conditions. Like the previous studies, this study documented statistically significant higher HRV in the green compared to the suburban condition, again suggesting reduced stress and enhanced relaxation response. Reasons for the mixed responses in the published studies include variability in methods, differences in designs and the populations studied (cultural variation).

With the work presented here, we evaluate the role of using HRV metrics to examine changes in PNS activity between participants walking on an urban road as compared to walking on a green (garden) road. Our primary objective was to calculate HRV metrics continuously during both the walks, to determine if subjects experience suppressed SNS activity and an increase in the PNS response, equating to an overall increase in SDNN and RMSSD (with higher increase in RMSSD) for the green walk as compared to the urban walk. The collected HRV neuronal stress response data is supplemented with saliva cortisol measures to measure the hormonal stress response, thereby providing a more wholistic assessment of the impact of the two different environments on both arms of the stress response.

Materials and Methods

Location

In 2017 “The Green Road” was built at Naval Support Activity, Bethesda (NSA/B) to promote healing among service members based on previous research findings that walking on greener roads can help reduce stress. Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Walter Reed), the DoD’s largest treatment facility is located on NSA/B where many short- and long-term military patients, their family members, active duty and civilian staff, and medical students reside, visit or work. The Green Road consists of a two-acre garden, located in an eight-acre woodland ravine, surrounding an existing natural stream.

Previously we published our results wherein we compared walking along the Green Road to walking on a nearby NSA/B road with concrete sidewalks and built-up features. The paths were matched for activity level and duration; since they run roughly parallel and represented options for pedestrians at NSA/B going to similar places. There, we documented positive subjective responses to the Green Road by using both self-report mood scales and qualitative interviews [

25].

Study Population

The study was approved by Uniformed Services University’s Institutional Review Board. We recruited 20 subjects between September 2018 and November 2019. Inclusion criteria included: being a service member, military retiree, military family member, caregiver, student, or NSA/B employee; being ambulatory; aged 18-60 years; able to speak and read English; able to complete study questionnaires; able to abstain from food, alcohol, and tobacco for one hour prior to experiment; lack of overt heart disease or diagnoses limiting mobility; not pregnant or lactating.

Three participants were removed from analyses (one male and two females) due to corrupted raw RR values from the BodyGuard ECG device worn by the participants that prevented us from calculating HRV metrics. This availed an analytic sample of 17, with a median of 34 years old, and ranged from 19 to 60 (interquartile range: 27, 44), and were mostly female (82%). Over a third were Caucasian (35%), followed by African American (24%), Asian American/Pacific Islander (24%), bi-racial (12%), and American Native (6%). Body mass index (BMI) was between 25 and 30 for 21% of females and 67% of males, and over 30 for 21% of females and no males.

Experimental Procedures

The Green Road, a 1.2-mile woodland path, is one of the US’ largest wild-type healing gardens and was completed in September 2017. This two-acre garden is situated in an eight-acre woodland ravine, with an existing natural stream. In 2017, the woodland was modified to enhance exposure to natural elements (trees, water, stones, wild animals), based on elements deemed desirable by focus groups of military personnel. The Green Road includes a Communal and Commemorative Pavilion (see Supplement for additional detail), while additional features, such as journaling benches, provide invitations for reflection. The road was built as a public/private partnership between the NSA/B and the Institute for Integrative Health (Baltimore) with substantial funding from TKF Foundation (Annapolis, MD), the friends of Shockey Gillet, Capital Funding, LLC, and other donors.

The urban road was comprised of concrete sidewalks and crosswalks on a relatively busy campus surrounded by buildings, multi-level parking garages, signs, small grassy areas, and some trees. The road has mostly man-made features, with some touches of nature. It borders on a memorial plaza featuring a Navy anchor, cement plaque, and tall statue in honor of Walter Reed.

Figure 1.

Images of the green road and the urban road walked by participants. (a) The green road was a 1.2-mile woodland pathway and (b) the urban road comprised of concrete sidewalks & crosswalks.

Figure 1.

Images of the green road and the urban road walked by participants. (a) The green road was a 1.2-mile woodland pathway and (b) the urban road comprised of concrete sidewalks & crosswalks.

After informed consent, all participants walked on both roads on different days with the order randomized. The two walks were frequently scheduled within a few days of each other to accommodate for schedules; the median number of days apart across subjects was four days (range: 1- 13). All sessions started in the morning before 9am and included the following: body weight, height and blood pressure measurements; completing demographics/trait questionnaires (first day only); placement of HRV monitor and chest electrodes; a five-minute pre-walk HRV recording while the subject was sitting down with legs and arms uncrossed; collection of pre-walk salivary sample; completion of state questionnaires (see below); walking on the Green or urban road for approximately 20 minutes; a five-minute post-walk HRV recording similar to the pre-walk; post-walk saliva sample collection; post-walk state questionnaires; qualitative interview.

Physiological Measurement System and HRV Metrics Calculation

To calculate HRV metrics during the Green and urban walks, participants were asked to wear a single lead ECG device called Bodyguard v2. Inter-beat interval (IBI) values obtained from this device were then used to calculate two time domain HRV metrics – RMSSD and SDNN over a finite non-overlapping sliding window using custom written Python code. Based on past literature on short-term HRV recordings we used a window size of 60 seconds for both RMSSD and SDNN.[

17] A single HRV metric was calculated for each 60s interval over the entire walk (both urban and green). This allowed us to study the changes in HRV trends as the walk progressed for both roads. Participants walked for exactly 20 mins on the urban road and between 20-22 mins on the green road which gave rise to an uneven number of samples for both walks. We used spline interpolation during the walks to generate 20 HRV points (RMSSD & SDNN) each during the walk for every participant to simulate homogenous sampling, reduce motion artifacts and account for missed samples from Bodyguard 2. Mean-Square Error (MSE) was used to measure the fit error between the spline and raw HRV data, and a smoothing factor of

s=0.4 was selected for the fitted spline.

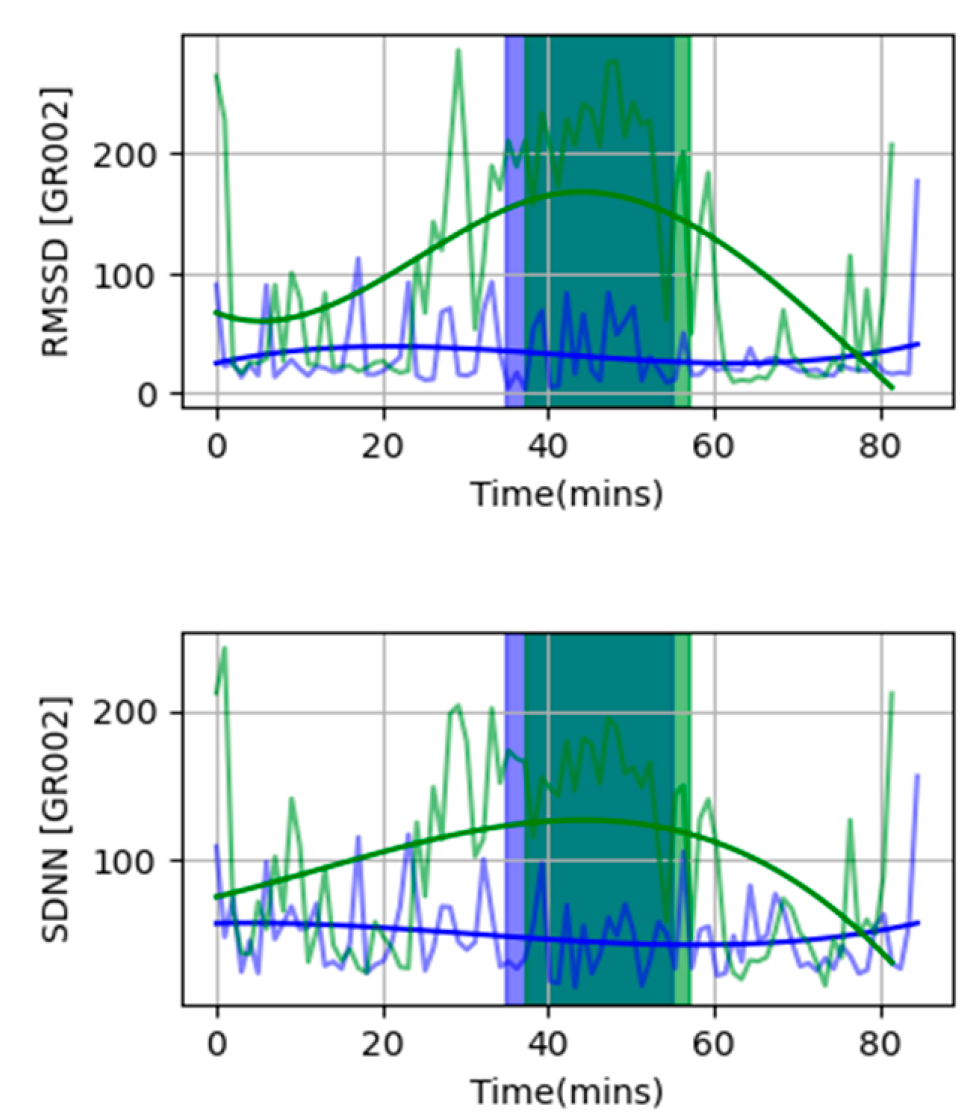

Figure 2 shows an example of how we calculate the smoothen metrics for HRV metrics for participant GR2. A full figure that shows all participants can be found in supplemental section for figures. Colored boxes indicate durations of active walk, with green indicating green road and blue for urban road. We show the smoothened spline fitted to the raw HRV metrics which are calculated over the windows.

Psychological Measurements

We examined two self-report state-scales – the 37-item Profile of Mood States (POMS) and the 5-item Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) [

26,

27]. Both scales asked about how participants were feeling in the present moment, and were administered four times – before and after the Green Road and the Urban Road. The POMS consists of 37 single-word adjectives (e.g., worn-out), and asks participants to rate how they are feeling right now along a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from "not at all" to "extremely". Scores from the POMS include depression, anger, confusion, vigor, and tension, and a total mood disturbance score (based on the all the subscales, and with the vigor items reverse-coded). For these analyses, only the total mood and vigor subscale scores were included, because the other scores had very strong floor effects (≥ 50% receiving the minimal score). These two scale scores demonstrated strong reliability at all timepoints, with alpha around 0.8 for total mood and 0.9 for vigor.

The MAAS has five items asking about how much attention is directed to present circumstances (e.g., “I was rushing through something without being really attentive to it”). Participants rate each item along a seven-point Likert type scale with anchors ranging from “not at all” to “very much”. Post-walk reliability was 0.75 for the Urban Road and 0.85 for the Green Road.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were primarily descriptive and intended to depict dynamic changes in HRV across the two conditions. Additional exploratory analyses examined associations between HRV-derived metrics and state-scales. HRV metrics throughout the walk were aggregated for both roads and pairwise t-test was used to calculate the p-values to quantify significant differences in physiological stress indications.

Raw Data and Analysis Code

Raw IBI values from Bodyguard 2 along with the self-reported state-scales data are available on request. All source code used for analysis in this work is organized in Python Jupyter notebooks and publicly available on Github –

https://github.com/UArizonaCB2/GreenroadHRV.git.

Saliva Cortisol Measurements

Cortisol was measured in salvia samples collected from each participant before and after their walk. Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry was performed using a ThermoScientific TSQ Quantiva triple quadrupole machine. Cortisol was tracked using MS/MS selective reaction monitoring with a mass transition of 363.2 > 121.1 m/z. Cortisol concentrations were derived from the peak area of the mass transition peak using a calibration curve generated using cortisol standard solutions designed to capture endogenous concentrations ranging from 0.4 – 25.0 ng/mL (slope: y = 784.39x, R

2 = 0.9919). The detailed LC/MS conditions are described in a previous report [

28].

Retrospective Stratification of Participants into Groups Based on HRV Changes

In order to differentiate participants who showed a positive change as measured using their HRV metrics versus those that did not, we retrospectively stratified the participants into groups based on those that showed positive impact, negative impact and mixed impact on all HRV metrics when walking the green road as compared to the urban road.

Results

Heart Rate Variability

Table 1 compares HRV data during the Green and urban road walks. Delta R and S values show the difference in mean RMSSD and SDNN between green and urban walk respectively. A positive delta value with a p<0.05 indicates a significant increase in that HRV metric on the green as compared to the urban walk. These differences have been indicated with a (*). We see three different patterns in our participants: (1) those showing an increase in both HRV metrics on the green as compared to urban road; (2) those showing a decrease in both HRV metrics on the green as compared to urban road; and (3) those showing increases in one of the HRV metrics for the green road. We indicate these participants with (1), (2) and (3) respectively, with 52% in 1 (N=9), 35% in 2 (N=6) and 11% in 3 (N=2).

Table 2 summarizes the delta changes in HRV and cortisol metrics during the walk for each group between green and urban road. Only those who showed a significant change have been included in the HRV comparison with everyone being included for cortisol changes. Difference in both metrics was measured as (green – urban), and then aggregated to calculate mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ). ∆% for all 3 metrics was calculated as [μ(green) – μ(urban)) x 100 / μ(urban)]. For group 1 individuals we see a 104% increase (mean) in RMSSD and 47% increase (mean) in SDNN values indicating an overall reduction in physiological stress. This is complemented by our findings in cortisol with an increase of 56%.

While we see a decrease (mean) of 42% and 31% in the respective HRV metrics for those in group 2 signaling a possible increase in physiological stresses we also saw a decrease in cortisol of 27%. For the two individuals in group 3 we are unable to determine a statistically significant increase or decrease in their HRV metrics.

Self-Report Scales

We examined partial correlations between HRV metrics derived above and self-report scales (total mood disturbance, vigor, mindfulness) (

Table 3). The correlations adjusted for pre-walk measures of HRV and pre-walk mood scores. Given the small sample and exploratory nature, we omit p-values, and focus on the general pattern. Compared to post-walk resting HRV, HRV measures taken during the walks had a larger association with post-walk self-report scores, particularly for vigor and mood disturbance; these associations were more robust for the Green Road than for the Urban Road. For the mood scales (total mood, vigor), the associations were in the expected directions, with higher HRV being associated with improved overall mood. Associations between HRV and state-mindfulness were less consistent and for RMSSD were in the opposite direction than expected.

Cortisol

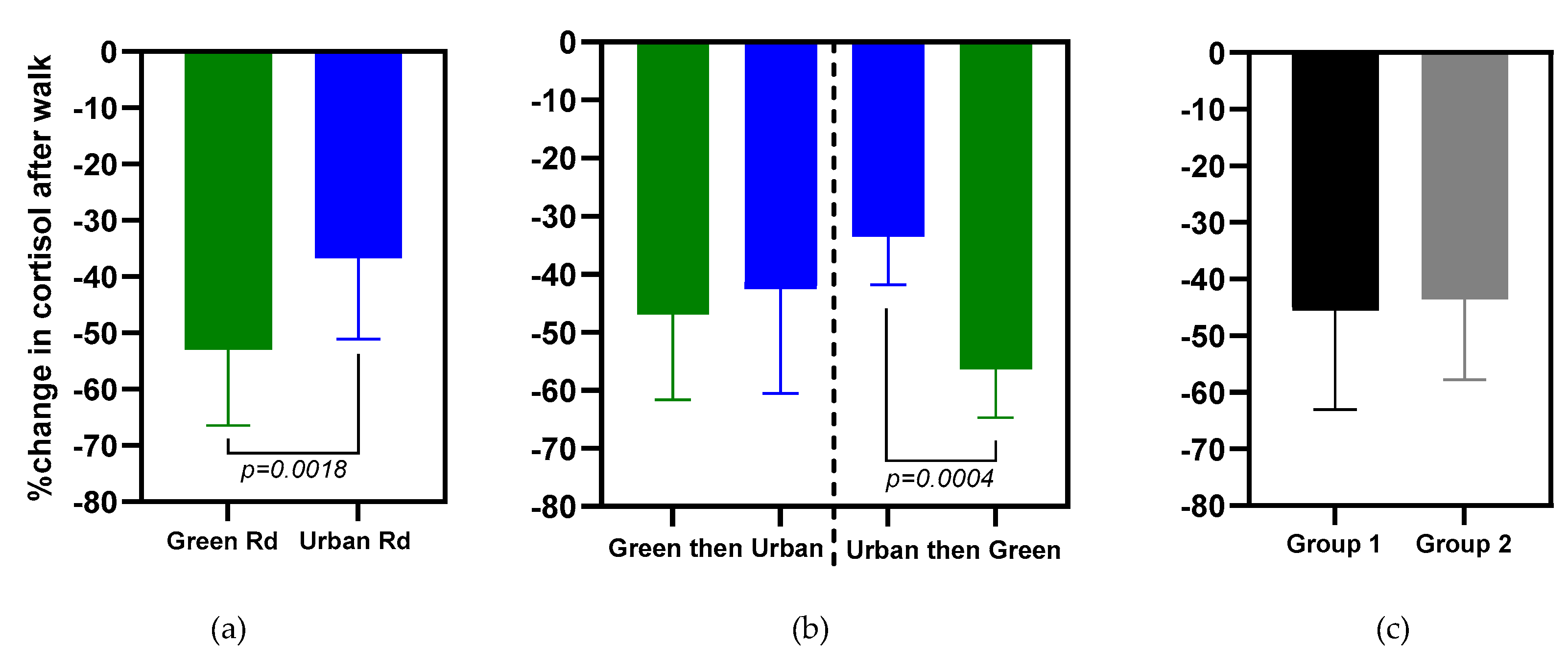

The percent change in measured saliva cortisol after taking a walk is shown in the two right columns in

Table 1. Cortisol was lower after taking a walk for all participants independent of walking path. However, walking the Green Road elicited a significantly larger reduction in cortisol compared to walking the Urban Road as shown in

Figure 3a.

On average we observed a average decrease in cortisol of 53% when walking the green road as compared to 37% for urban road. Further as shown in

Figure 3b we observed an an impact on meaured cortisol dependent on which road was walked first. A significant decrease in measured cortisol was found when participants walked the Green Road after walking the Urban Road (an average decrease of -68%). By comparison, an insignicant increase in measured cortisol was observed for participants who walked the green road first (average increase of 9% in measured cortisol after walking the urban road second).

Interestingly, as shown in

Figure 3c, there was no observed difference in measured cortisol after taking a walk when comparing the participants in HRV group 1 with group 2 (group are the same as shown in

Table 1).

Discussion and Limitations

Grouping the individuals retrospectively based on changes in their HRV metrics allowed the relative effects of both the green and urban environments on the participants to be quantified. For group 1 we saw a significant increase in both HRV metrics for 7 participants, with a larger mean increase in RMSSD (almost double) values as compared to SDNN. SDNN represents the overall autonomic function of the heart (SNS + PNS), while RMSSD is more focused on the parasympathetic modulation of the heart [

29,

30,

31]. For these 7 individuals who were part of this group we argue that walking on the green road showed an increase in their PNS activity, and a marked decrease in their fight or flight responses (SNS activity). While the remaining 2 participants in this group did show a decrease in HRV metrics, they were not statistically significant. For group 2, we saw a significant decrease in both HRV metrics for all 6 participants, when walking on the green road as compared to the urban road. A larger decrease of RMSSD (mean 42%) as compared to SDNN (mean 31%) suggests that these individuals had an elevated SNS activity when walking the urban road as compared to the green road.

These conclusions are supported by the cortisol data where the decrease in cortisol shows reduction in SNS and signals activation of the PNS during the walk. HRV groups 1 and 2 showed similar decreases on cortisol after taking a walk, however, group 1 showed a larger decrease of 56% on average as compared 27% for group 2. Further all participants showed a more significant decrease in cortisol after walking the green road compared with the urban road highlighting the positive impact of the green road on reducing physiological stress compared with the Urban Road.

Group 1 also exhibited a diverse range of individual differences in HRV metric deltas, ranging from a minor change for GR3 (R=1.7, S=3.93) to a relatively large change for GR17 (R=120.25, S=95.58). This wide spread of HRV changes suggests that while walking on the green road had a beneficial impact on reducing stress there is a high degree of individual variability that can stem from baseline physiological conditioning and overall experience during the walk. Supplemental figure 1 shows a plot of HRV metrics for all individuals in group 1, further highlighting the individual differences. We notice that for all participants except GR2 and GR14 HRV metrics drop during the walk and come back to baseline after the walk is over. On the other hand, participants such as GR17 showed a remarkable increase in HRV metrics prior to the green walk, as compared to almost no change prior to (or during) the urban walk. We also note that participants had a wide range of baseline HRV, measured during a 5-minute window prior to walk when participants sat still without moving or talking with their legs and ankles uncrossed. During the urban walk for this group the baseline RMSSD ranged from 13ms (GR20) to 70ms (GR5), mean of 40ms with standard deviation of 20ms. On the other hand, the baseline SDNN for this group ranged from 33ms (GR20) to 99ms (GR15), mean of 65ms, std of 24ms. For the green road the baseline for RMSSD ranged between 16ms (GR20) to 124ms (GR5), mean of 53ms, std of 34ms. SDNN ranged from 46ms (GR3) to 111ms (GR5), mean of 75ms, std of 23ms. In both urban and green walk days (walks happened on different days), the mean baseline for SDNN was higher in comparison to RMSSD, indicating the individuals had a much higher SNS activation as compared PNS prior to both the walks. When comparing the baseline between the 2 days we saw a mean difference of 17ms (std=16ms) for RMSSD and 17ms (std=9ms) for SDNN. This further highlights the variety in individual HRV characteristics on days when the 2 walks were conducted. We also note that GR8 (group 2) reported seeing a snake on green road, further increasing the challenge of controlling such factors on an open walk. Additionally, the difference in terrain such as elevation grade and surrounding noises (GR11 reported being disturbed with construction noises on urban) could be controlled for such real-world tests.

Taken together, these findings are consistent with the stress-attenuating effects of nature exposure, in this case walking the “Green Road”. However, there was considerable individual variability in autonomic nervous system (ANS) stress responses as measured by HRV, with some individuals showing a substantial positive impact on HRV and others little or no. In contrast, the cortisol response decreased more consistently while walking the Green Road. The order in which individuals walked the green road and urban road impacted their cortisol response. Thus, those walking the urban road before the green road showed a substantial reduction in cortisol, while those walking the green road before the urban road showed only a small elevation of cortisol while walking the urban road, suggesting a possible attenuation effect of walking the green road first. Overall, however walking the green road lowered cortisol. Interestingly, there was no difference in % change of cortisol between groups 1 and 2, despite the difference in HRV responses between these two groups, consistent with the different and independent physiological control of the two arms of the stress response – the neuronal (HRV, ANS) and hormonal (cortisol/hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis). Self-reported mood correlated much more closely with HRV metrics recorded during the walk than with HRV metrics taken after the work. This suggests that future studies into autonomic-mediated improvements in mood states should focus more on measuring HRV during an activity or in the moment, rather than after a change is already presumed to have occurred (e.g., during a manipulation, not post- manipulation).

Conclusions

The measured physiological and hormonal response to walking the green road was very individualistic among the participants, and 60% showed both HRV and cortisol responses indicative of decreased stress after walking the green road. These findings provide quantitative data demonstrating the stress-reducing effects of being in nature and supporting the health benefit value of providing access to nature more broadly in many settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Consortium for Health and Military Performance (CHAMP) and by a grant from The Institute for Integrative Health and Nature Sacred (formerly TKF Foundation).

Disclaimers

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Defense Health Agency, Uniformed Services University, the Department of Defense, or the US Government. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions or policies of The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The authors have no competing interests, financial interests or relationships to disclose.

References

- Schweitzer M, Gilpin L, Frampton SB. Healing spaces: elements of environmental design that make an impact on health. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine. 2004;10 Suppl 1:S71-83.

- Bowler DE, Buyung-Ali LM, Knight TM, Pullin AS. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health. 2010/08/04 2010;10(1):456. [CrossRef]

- Doimo I, Masiero M, Gatto P. Forest and Wellbeing: Bridging Medical and Forest Research for Effective Forest-Based Initiatives. Forests. 2020;11(8):791.

- Stier-Jarmer M, Throner V, Kirschneck M, Immich G, Frisch D, Schuh A. The Psychological and Physical Effects of Forests on Human Health: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(4)doi:https://10.3390/ijerph18041770.

- Caravalho JJ. Improving Soldier Health and Performance by Moving Army Medicine Toward a System for Health. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2015;29:S4-S9. [CrossRef]

- Shams-White MM, Cuccia A, Ona F, et al. Lessons Learned From the Creating Active Communities and Healthy Environments Toolkit Pilot: A Qualitative Study. Environmental Health Insights. 2019;13:1178630219862231. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich R. Biophilia, biophobia, and natural landscapes. Biophilia, Biophobia, and Natural Landscapes. 01/01 1993:73-137.

- Bratman GN, Hamilton J, Daily GC. The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1249.

- Kaplan R, Kaplan S. The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press; 1989:xii, 340-xii, 340.

- Cygankiewicz I, Zareba W. Heart rate variability. (0072-9752 (Print)).

- Gao J, Gurbaxani BM, Hu J, et al. Multiscale analysis of heart rate variability in non-stationary environments. Original Research. Frontiers in Physiology. 2013-May-30 2013;4doi:10.3389/fphys.2013.00119.

- Valenza G, Garcia RG, Citi L, Scilingo EP, Tomaz CA, Barbieri R. Nonlinear digital signal processing in mental health: characterization of major depression using instantaneous entropy measures of heartbeat dynamics. Original Research. Frontiers in Physiology. 2015-March-13 2015;6doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00074.

- Schroeder EB, Whitsel EA, Evans GW, Prineas RJ, Chambless LE, Heiss G. Repeatability of heart rate variability measures. Journal of Electrocardiology. 2004/07/01/ 2004;37(3):163-172.

- Taelman J, Vandeput S, Spaepen A, Van Huffel S. Influence of Mental Stress on Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2009:1366-1369.

- Dimitriev D, Dimitriev A, Karpenko Y, Saperova E. Influence of examination stress and psychoemotional characteristics on the blood pressure and heart rate regulation in female students. Fiziologiia Cheloveka. 09/01 2008;34:617-624. [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin L, Cho J, Jeong M, Kim D. Ultra Short Term Analysis of Heart Rate Variability for Monitoring Mental Stress in Mobile Settings. Conference proceedings : Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society Conference. 02/01 2007;2007:4656-9. [CrossRef]

- Pereira T, Almeida PR, Cunha JPS, Aguiar A. Heart rate variability metrics for fine-grained stress level assessment. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2017/09// 2017;148:71-80. [CrossRef]

- Anderson AP, Mayer MD, Fellows AM, Cowan DR, Hegel MT, Buckey JC. Relaxation with Immersive Natural Scenes Presented Using Virtual Reality. Aerospace medicine and human performance. 2017;88 6:520-526.

- Annerstedt M, Jönsson P Fau - Wallergård M, Wallergård M Fau - Johansson G, et al. Inducing physiological stress recovery with sounds of nature in a virtual reality forest--results from a pilot study. Physiol Behav. 2013;118(1873-507X (Electronic)):240-50. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Qu H, Ma Y, Wang K, Qu H. Restorative benefits of urban green space: Physiological, psychological restoration and eye movement analysis. Journal of Environmental Management. 2022/01/01/ 2022;301:113930. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Park BJ, Tsunetsugu Y, Ohira T, Kagawa T, Miyazaki Y. Effect of forest bathing on physiological and psychological responses in young Japanese male subjects. Public Health. 2011/02/01/ 2011;125(2):93-100. [CrossRef]

- Park BJ, Tsunetsugu Y, Kasetani T, Kagawa T, Miyazaki Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine. 2010/01/01 2010;15(1):18-26. [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter UK, Corazon SS, Sidenius U, Kristiansen J, Grahn P. It is not all bad for the grey city – A crossover study on physiological and psychological restoration in a forest and an urban environment☆. Health & Place. 2017;46:145–154.

- de Brito J, Pope Z, Mitchell N, et al. The effect of green walking on heart rate variability: A pilot crossover study. Environmental Research. 03/01 2020;185:109408. [CrossRef]

- Ameli R, Skeath P, Abraham PA, et al. A nature-based health intervention at a military healthcare center: a randomized, controlled, cross-over study. PeerJ. 2021;9.

- Curran S, Andrykowski M, Studts J. Short form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): Psychometric information. Psychological Assessment. 03/01 1995;7:80-83. [CrossRef]

- Brown K, Ryan R. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. Journal of personality and social psychology. 04/01 2003;84:822-48. [CrossRef]

- Runyon JR, Jia M, Goldstein MR, et al. Dynamic Behavior of Cortisol and Cortisol Metabolites in Human Eccrine Sweat. International Journal of Prognostics and Health Management. 2019;doi:10.36001/ijphm.2019.v10i3.2707.

- Carnethon MR, Prineas RJ, Temprosa M, et al. The Association Among Autonomic Nervous System Function, Incident Diabetes, and Intervention Arm in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(4):914-919. [CrossRef]

- Barreto GSC, Vanderlei FM, Vanderlei LCM, Leite ÁJM. Impact of malnutrition on cardiac autonomic modulation in children. Jornal de Pediatria. 2016/11/01/ 2016;92(6):638-644. [CrossRef]

- Chuang C-Y, Tsai C-N, Kao M-T, Huang S. Effects of Massage Therapy Intervention on Autonomic Nervous System Promotion in Integrated Circuit Design Company Employees. IFMBE Proceedings. 01/01 2014;43:562-564. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).