Submitted:

26 September 2024

Posted:

27 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poulek, V.; Dang, M.Q.; Libra, M.; Beránek, V.; Šafránková, J. PV Panel with Integrated Lithium Accumulators for BAPV Applications—One Year Thermal Evaluation. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2020, 10, 150–152.

- Christensen, J.; Hewitson, B.; Busuioc, A.; Chen, A.; Gao, X.; Held, I.; Jones, R.; Kolli, R.; Kwon, W.T.; Laprise, R.; et al. Regional Climate Projections. In IPCC Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis; Solomon, S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Hen, Z., Marquis, M., Averyt, K., Tignor, M., Miller, H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA.

- Van Oldenborgh, G.; Collins, M.; Arblaster, J.; Christensen, J.H.; Marotzke, J.; Power, S.; Rummukainen, M.; Zhou, T. Annex I: Atlas of Global and Regional Climate Projections. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis; Stocker, T., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., Midgley, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013.

- Kjellström, E.; Nikulin, G.; Strandberg, G.; Christensen, O.B.; Jacob, D.; Keuler, K.; Lenderink, G.; van Meijgaard, E.; Schär, C.; Somot, S. European climate change at global mean temperature increases of 1.5 and 2.0 C above pre-industrial conditions as simulated by the 30 EURO-CORDEX regional climate models. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2018, 9, 459–478.

- Nardone, A.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N.; Ranieri, M.S.; Bernabucci, U. Effects of climate changes on animal production and sustainability of livestock systems. Livest. Sci. 2010, 130, 57–69.

- Armstrong, D.V.. Heat stress interaction with shade and cooling. J. Dairy Sci. 1994, 77, 2044–2050.

- Silanikove, N.; Shapiro, F.; Shinder, D. Acute heat stress brings down milk secretion in dairy cows by up-regulating the activity of the milk-borne negative feedback regulatory system. BMC Physiol. 2009, 9, 13.

- Dikmen, S.; and Hansen, P. J. Is the temperature-humidity index the best indicator of heat stress in lactating dairy cows in a subtropical environment? J. Dairy Sci., 2009, 92, 109–116.

- Renaudeau, D.A.; Collin, S.; Yahav, V.; De Basilio, J.L.; Gourdine, R.J. Adaptation to hot climate and strategies to alleviate heat stress in livestock production. Animal, 2012, 6, 707–728.

- Allen, J.D.; Hall, L.W.; Collier, R.J.; Smith, J.F. Effect of core body temperature, time of day, and climate conditions on behavioral patterns of lactating dairy cows experiencing mild to moderate heat stress. J. Dairy Sci., 2015, 98, 118–127.

- Hahn, G. L.; Mader, T. L. and Eigenberg R. A. Perspective on development of thermal indices for animal studies and management. EAAP Technical Series, 2003, 7:31–44.

- Alexandrov, V. Report on the spatial distribution of soil drought in Bulgaria. Agronet, 2006, Sofia. [BG].

- Dimov, D.; Marinov, I.; Penev, T.; Miteva, Ch.; Gergovska, Zh. Influence of temperature-humidity index on comfort indices in dairy cows. Sylwan, 2017, 161 (6): 68-85.

- Nardone, A.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N. and Bernabucci, U. Climatic effects on productive traits in livestock. Vet. Res. Com., 2006, 30(Suppl. 1), 75–81.

- Hernandes-Rivera, J. A.; Alvarez-Valenzuela, F.D.; Correa-Calderon, A.; Macias-Cruz, U.; Fadel, J.G.; Robinson, P.H.; Avendano-Reyes, L.. Effect of short-term cooling on physiological and productive responses of primiparous Holstein cows exposed to elevated ambient temperatures. Acta Agriculturae Scand Section A, 2011, 61: 34-39.

- Provolo, G. and Riva. E. Daily and seasonal patterns of lying and standing behaviour of dairy cows in a freestall barn. In Proc. International Conference “Innovation Technology to Empower Safety, Health and Welfare in Agriculture and Agro-Food Systems,” 2008, Ragusa, Italy.

- Perissinotto, М.; Moura, D.; Matarazzo, S.; Mendes, A. and Naas, I.. Thermal Preference of Dairy Cows Housed in Environmentally Controlled Freestall. Agricultural Engineering International: the CIGR Ejournal. 2006, Manuscript BC 05 016. Vol. VIII. March.

- MAFWE. Ordinance № 44 on the veterinary requirements for livestock farms. April 20, 2006 SG no. 41/2006, Bulgaria (Bg).

- Ozhan, M.; Tiizcmen, N.; and Yanar M. "Buyukbas hayvan yetistirme. Ucuncii baski.' Atatiirk Universitesi Ziraat Fakiiltesi Ofset Tesisi, 2001, Erzurum. (TR).

- Šoch, M.; Matoušková, E.; Trávníček, J. The Microclimatic conditions in cattle and sheep stables at selected farms in Šumava. In: Proc. 3rd Int. Scientific Conference Agroregion, 2000, Zootechnical Section, České Budějovice, 151–152.

- Miteva, Ch. Hygienic aspects of production in dairy cows in freestall barns. Trakia University Publishing House, Stara Zagora; 2012, ISBN 978-954-338-048-0 (Bg).

- Uzal, S.. Seasonal variation of the lying and standing behavior indexes of dairy cattle at different daily time periods in free-stall housing. An. Sci. J., 2013, 84, 708–717.

- Aggarwal, A.; and Upadhyay, R. Heat Stress and Animal Productivity. DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-0879-2_3, © Springer India. 2013.

- Segnalini, M.; Bernabucci, U.; Vitali, A.; Nardone, A.; Lacetera, N. Temperature humidity index scenarios in the Mediterranean basin. Int J Biometeorol., 2013, 57: 451–458.

- Brouček, J.; Mihina, Š.; Ryba, Š.; Tongeľ, P.; Kišac, P.; Uhrinčať, M.; Hanus, A. Effects of High Air Temperatures on Milk Efficiency in Dairy Cows. Czech J. Anim. Sci., 51, 2006 (3): 93–101.

- Huber, P. Temperature, humidity and air movement variations inside a free-stall barn during heavy frost. Ann. Anim. Sci., 2013, Vol. 13, No. 3 587–596.

- Upadhyay, R.C.; Ashutosh, A.K.; Gupta, S.K.; Singh, S.V.; Rani, N.. Inventory of methane emission from livestock in India. In: Aggarwal PK (ed) Global climate change and Indian agriculture. ICAR, New Delhi, 2009, pp 117–122.

- Moallem, U.; Altmark, G.; Lehrer, H.; Arieli, A. Performance of high-yielding dairy cows supplemented with fat or concentrate under hot and humid climates. J. of Dairy Sci. 2010; 93(7):3192–3202. doi: . [CrossRef]

- Dimov, D.; Penev T.; and Marinov, Iv. Temperature-humidity index – an indicator for prediction of heat stress in dairy cows. Vet. ir Zootech. 2020, 78(100): 74-79.

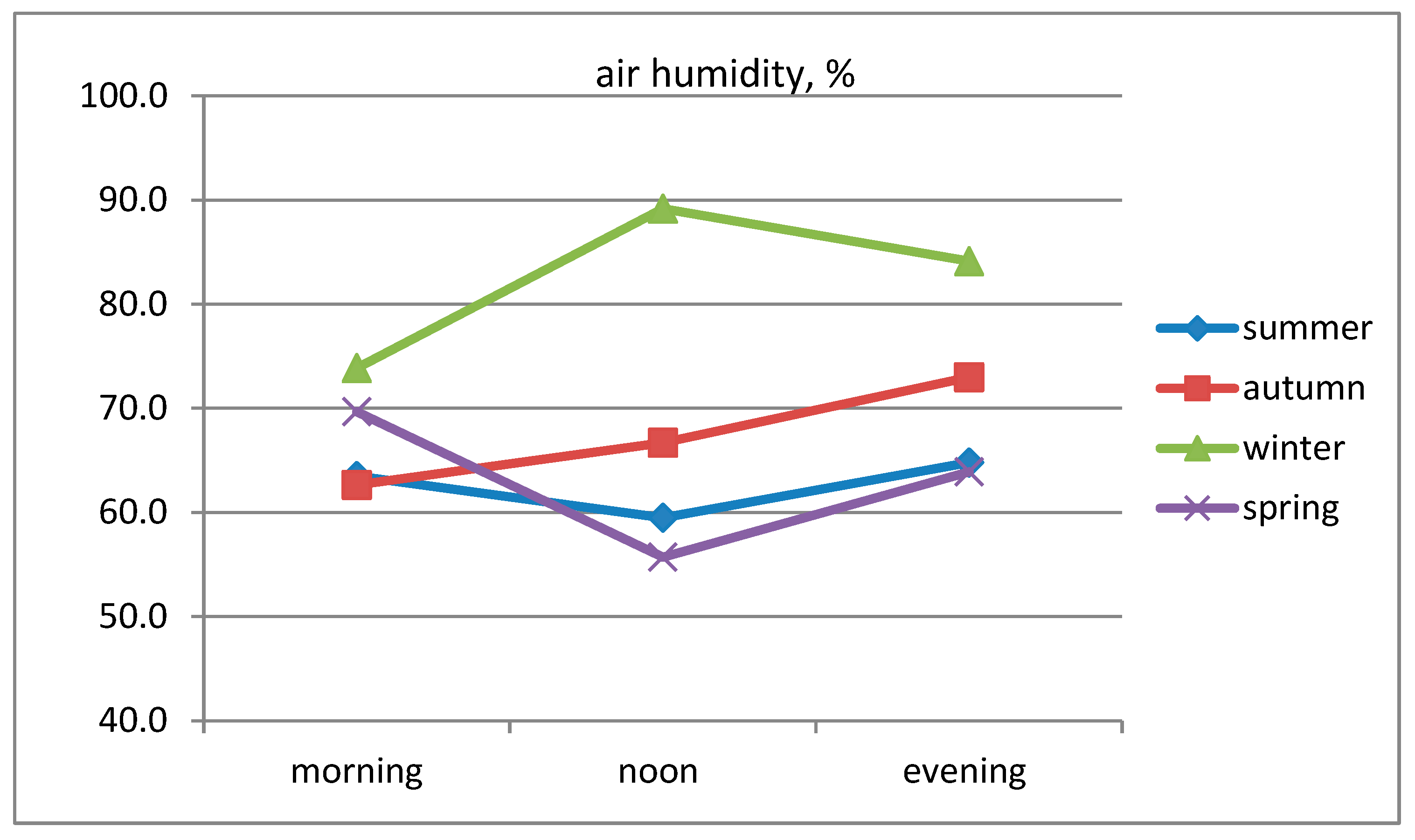

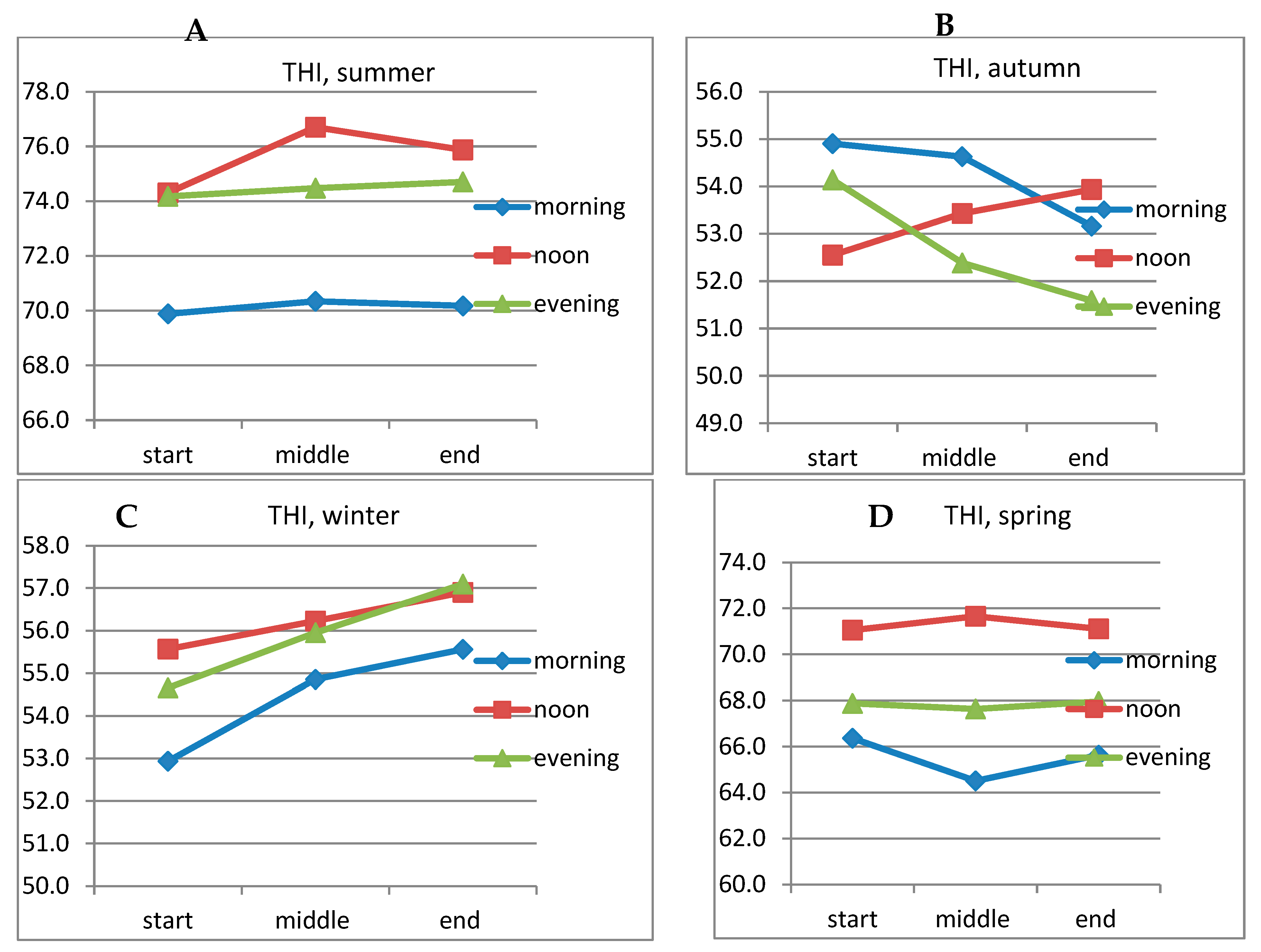

| Season | Number of observations (n) | Temperature, 0С | Humidity, % | THI | |||

| X ± Se | Max | X ± Se | Max | X ± Se | Max | ||

| Summer | 27 | 25.30±0.43 | 31.4 | 62.60±1.29 | 78.0 | 73.41±0.55 | 80.0 |

| Autumn | 18 | 11.37±0.53 | 14.4 | 67.46±2.97 | 85.5 | 53.19±0.88 | 57.92 |

| Winter | 9 | 12.90±0.29 | 13.9 | 82.39±2.32 | 89.8 | 55.53±0.42 | 57.09 |

| Spring | 21 | 21.90±0.95 | 31.4 | 62.51±1.90 | 87.8 | 68.49±1.29 | 78.06 |

| Source of variation | Degrees of freedom (n – 1) | Temperature, 0С | Humidity, % | THI | |||

| MS | F P | MS | F P | MS | F P | ||

| Total for model | 7 | 403.79 | 31.27*** | 536.85 | 5.68*** | 827.92 | 32.68*** |

| Season | 3 | 887.90 | 68.78*** | 1047.4 | 11.08*** | 1854.5 | 73.21*** |

| Milking sequence | 2 | 71.21 | 5.52** | 246.3 | 2.60 - | 99.2 | 3.91* |

| Reporting during milking | 2 | 0.49 | 0.04 - | 54.5 | 0.58 - | 0.7 | 0.03- |

| Error | 79 | 12.91 | 94.6 | 25.3 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).