Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has become increasingly prevalent in the global population, with over six million Americans living with the disorder, and research suggests this number will continue to rise [

1]. AD remains the most common type of dementia and is prevalent amongst 60-70% of dementia cases. AD is characterized by abnormal effects on cognition and behavior, with the underlying pathophysiology involving the manifestation of extracellular amyloid plaques, synaptic deterioration, and neuronal death [

2,

3]. A retrospective study conducted on 1.8 million individuals found that increased levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol have been noted as a possible risk factor for this disease [

4]. Amidst these developments, statins, such as atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, and others, are often prescribed for the management of hypercholesterolemia and the prevention of cardiovascular diseases [

5]. However, they have emerged over the past few decades as a tool to influence the progression and/or therapeutic potential of this disease. The relationship between statin use and AD remains complex, with multiple studies suggesting that statin use may reduce the risk of developing the disease, while other authors have found no association. This review aims to examine the relationship between statins and the management and prevention of AD.

Methods

Two different databases were utilized to obtain articles for this literature review; Google Scholar and PubMed. Neurodegeneration, statins, pleiotropic, and neuroprotective were keywords used when obtaining applicable articles. There were no specific exclusions made when researching articles. Chemical structures were drawn using KingDraw.

Mechanisms of Neurodegeneration and Cognitive Decline in AD

Amyloid-ꞵ Plaques and Neurofibrillary Tangles

Typically occurring together, amyloid-ꞵ plaques (Aꞵ) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) are the hallmarks of neurodegeneration in AD. Plaques result from proteolytic cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) into 40-43 amino acid-long peptides [

6]. The Aꞵ peptide forms amyloid fibrils that aggregate, with Aꞵ [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40] being the most recognized for its role in AD-affected brains [

7]. NFTs are aggregations of misfolded and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins [

8]. These intracellular aggregations disrupt the axoplasmic flow of neuronal communication and directly correlate to the degree of cognitive decline [

8,

9]. Multiple studies using both human and mice models (transgenic mouse expressing human APP and tau transgenes [

10]) have investigated imaging options to identify Aꞵ and NFTs in the brain [

11,

12,

13]. The main objective of these studies was to identify a relationship between the two and neurodegeneration [

10,

14]. The transgenic mice expressing human genes generated Aꞵ and NFTs and subsequently suffered from neurodegeneration [

10]. During the period of 11 months to 13 months, the mice developed significant tissue atrophy and neuronal loss associated with the increases in plaques and NFTs [

10]. Multitracer PET imaging using Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB) and FDDNP probes allow images of the plaques and tangles to be produced for brain monitoring [

11,

12,

13]

. PIB selectively binds to Aꞵ, allowing for PET imaging to measure the binding in AD individuals using a standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) for gray matter [

11]. FDDNP probes bind to Aꞵ and NFTs, measuring the binding in AD brains using a SUVR for gray matter as well [

11]. Multitracer PET imaging using a combination of these probes can be useful in accurately tracking disease progression [

11].

Oxidative Stress

The formation of Aꞵ plaques and NFTs can be both initiated and exacerbated by the presence of free radicals [

15,

16]. Oxidative stress is when the antioxidants in the body are out of balance with the oxidants in the body, and these oxidants are formed when oxygen molecules have an unpaired electron. The superoxide radical (O

2·−) is generated in the brain and removed by conversion to hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) by superoxide dismutases [

17]. Under ordinary circumstances, the protective antioxidant mechanisms are in balance with the formation of free radicals, keeping possible tissue damage and buildup under control [

18]. Brain tissue is composed of oxidation-sensitive lipids and is an organ with high O

2 consumption, making it extremely vulnerable to damage and high reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

15,

16]. The products of peroxidation are co-localized with Aꞵ plaques, with two of the primary metabolites occurring from white and gray matter [

16].

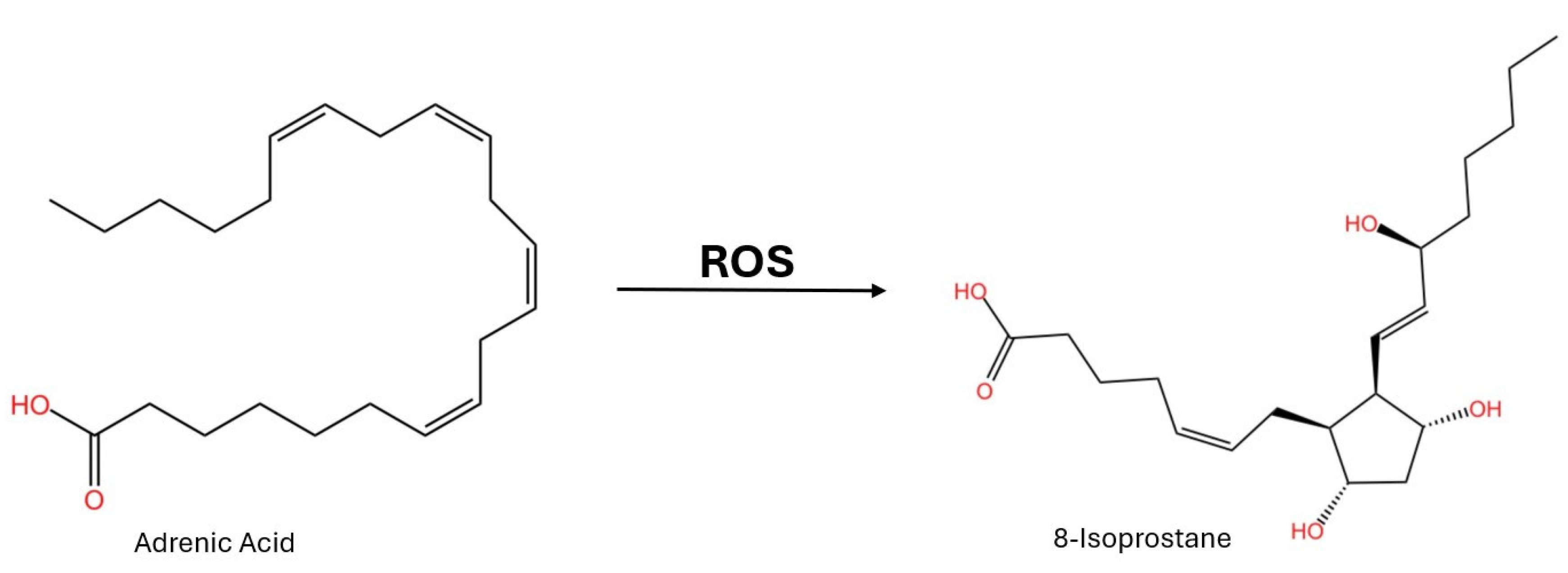

There have been investigations looking into whether these lipid peroxidation products could be potential AD biomarkers. Isoprostanes are oxidized from adrenic acid and found in the white matter (

Figure 1) [

16]. Using blood analysis, 8-isoprostane has been found to be increased in patients with AD in comparison to non-AD controls [

19,

20]. Oxysterols are the oxidized product of normal cholesterols in the brain. In tissue samples from the frontal and occipital cortex, oxysterols have been found in excess in AD-affected individuals [

21]. This links the oxidation of sterols to AD neurodegeneration. However, when observed in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), isoprostanes were not found to be a viable biomarker [

22]. In CSF, isoprostanes increased with age independently from established AD CSF markers (Aꞵ and NFTs) [

22]. Isoprostanes are a promising biomarker for the diagnosis of AD, but further research is needed to enforce this conclusion and find other suitable biomarkers as well.

Neuroinflammation

Neuroinflammation is a hallmark of many other neurodegenerative diseases, with its main purpose lying in CNS protection. In AD, glial activation and proinflammatory factors influence disease progression [

23]. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a semi-permeable membrane that monitors what can cross the barrier to the brain or what cannot. Surface transporters on the BBB move Aꞵ from the brain to the blood, but Aꞵ can affect the expression of tight junctions in the barrier [

24]. A major cause of disruption in the BBB is increased inflammatory cytokines. This disruption can then cause the accumulation of Aꞵ, leading to barrier dysfunction and increased monocyte adhesion [

24]. Astrocytes and microglia produce cytokines and are the main inflammatory cells in the CNS [

23,

24]. Microglia use danger-associated molecular pathways (DAMPs) and pathogen-associated molecular pathways (PAMPs) to recognize, activate, and phagocytize Aꞵ fibrils [

23,

25]. They then send chemokines to the site, and contrary to the normal mechanism, diseased brains show an upregulation of CCL2, -3, and -5 [

25]. These chemokines exacerbate the inflammatory response. In astrocytes near Aβ plaques in diseased brains, CCL4 is upregulated [

25].

Multiple rodent trials using transgenic mice have shown the link between neuroinflammation and AD pathology. Both interleukins and inflammasomes, both known for their role in inflammatory responses, are produced by the microglial cells in AD mouse models [

25]. However, it has been found that the transgenic APP mouse model is not a completely accurate representation of human AD [

26]. A knock-in mouse showing the appropriate amyloid deposition was used, and it was found that these mice share common neuroinflammatory genes with humans [

26]. In these mice, the triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) were upregulated and used as Aβ sensors to activate microglia, which in turn activate proinflammatory signals in the brain [

26]. In vivo, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) is the gold standard for early imaging of neuroinflammation and prevention of further damage [

27,

28]. MRS has shown that neuroinflammation is an early indication of AD and mainly precedes neurodegeneration [

27,

28].

Overall, AD is a multifactorial disease, and there is no single central cause. It is a combination of factors like the ones discussed above and in different grades. Treatment mainly involves a regimen of medications like donepezil and memantine. Donepezil is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that enhances cholinergic transmission at the synapse [

29]. It also has an effect in downregulating microglial activation in the brain, reducing inflammation [

29]. If a patient is unable to take an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, memantine can be used as a supplement. Memantine blocks the overactivation of the excitatory NMDA receptor, preventing neuronal damage [

30].

Statins Lipid-Lowering and Pleiotropic Effects

Low-density lipoproteins (LDL) are fat molecules that circulate the blood carrying cholesterol for cellular processes and are deposited on arterial walls [

31]. Elevated LDL levels can cause a buildup of plaque on the arterial walls. This is the main implication of coronary heart disease [

32]. LDLs are prone to oxidation, and oxLDL is pro-inflammatory, leading to endothelial dysfunction that exacerbates the deposition of plaques [

32]. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is a major component of reverse cholesterol transport. HDL transports cholesterol from peripheral tissues into the liver while also counteracting the oxidation of LDL [

32]. When LDL outweighs HDL, the counteractive effects of the HDL are not enough to prevent oxidation and deposition of plaques, in turn increasing the risk of heart disease. This also gives LDL the moniker “bad cholesterol”. Very low-density lipoprotein triglycerides are produced in the liver and contain a large protein called apoprotein B [

33]. Through interaction with a lipase and apoprotein E, VLDL converts to LDL unless apoprotein B is targeted for degradation [

33].

Statins, like atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, are the main combatants to high cholesterol levels. This is the result of their ability to reduce cholesterol biosynthesis in their target organ, the liver (hepatoselective) [

34,

35,

36]. The main mechanism for this to occur is through the inhibition of hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. HMG-CoA reductase converts HMG-CoA to mevalonate, a precursor to cholesterol [

38]. HMG-CoA is a liver enzyme that is regulated by AMPK and activated by a phosphoprotein phosphatase [

38]. Inhibition of this enzyme results in an increase in LDL clearance from the blood by the liver in patients with high cholesterol, while in patients with hyperlipidemia, the inhibition results in a decrease in both cholesterol and triglycerides by decreasing the production of the transport apoprotein B100 [

37]. However, with more evidence of statins exhibiting neuroprotective effects, there is clearly another mechanism of action at work here.

One such mechanism is an anti-inflammatory downregulation. Neuroinflammation, as discussed above, is one of the major mechanisms of neurodegeneration in AD. Statins, other than pravastatin that cannot cross the BBB, have been shown to bind to leukocyte function antigen-1(LFA-1) and prevent adhesion to intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) [

35,

40]. ICAM-1 signals are reduced, and this downregulates the inflammatory response [

35,

41,

42]. In an investigation using Sprauge-Dawley rats, fluvastatin reduced both cellular adhesion molecules and oxidative stress, independent of the lipid-lowering effects [

42]. Another trial using atorvastatin and lovastatin in mice and guinea pigs exhibited reduced substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in the dorsal root ganglia [

43]. These are two main peptides that can induce a proinflammatory response.

AD responses to Statin Effects

Statin Therapy and ApoE Genotype

ApoE4 is the major lipid and cholesterol carrier in the Central Nervous System (CNS) and one of the most important risk factors for AD [

50]. Statin use has shown the most promising outcomes on individuals with the expression of the ApoE4 allele, demonstrating its effectiveness through the modulation of that allele [

51]. Furthermore, statin use has been seen to be effective in the treatment of AD through the GTPase isoprenylation pathway, resulting in the reduction of Aꞵ formation [

51]. Although it does have its limitations, it is important to mention the possible differences in outcome in the interaction of an individual’s sex and ApoE4 genotype. An analysis of these measures noticed that males with the ApoE4 genotype could benefit more so than their female counterparts. Moreover, these authors also reported that carriers of the ApoE4 genotype have a decreased risk of AD [

52].

Statin Therapy Effects on AD Characteristics

The exact mechanism by which statins may slow the development of AD characteristics is not completely clear, there exists mixed evidence pointing to that hypothesis. This indistinction between studies could pertain to the groups in which statins fall into: fungal-derived, synthetic-derived, lipophilic, and hydrophilic. Lovastatin and simvastatin are amongst the most popular when studying statin effects on the brain due to their ability to cross the BBB [

53,

54]. An investigation into the use of statin therapy as a potential benefit for AD patients was found where the authors utilized multiple different cohort studies focusing on simvastatin use. Within this, they found that statin users did have better cognitive scores and an overall lower risk for AD [

55]. Statin users have also been found to have lower incidence of neurodegenerative disorders compared to non-users, with pitavastatin showing the strongest reduction of incidence among the eight statin types [

56].

Statin use has neuroprotective effects and has the possibility to decrease the progression of AD through its ability to lower cholesterol levels and reduce plaque formation [

57]. An analysis conducted on 40 AD male mice models being treated with atorvastatin demonstrated a reduction in Aꞵ production and tau hyperphosphorylation, leading to increased learning and memory. The authors found increased levels of phosphorylated AKT and glycogen synthase kinase 3ꞵ (GSK3ꞵ) in the hippocampus [

58]. This is significant as evidence suggests that these two signaling pathways are impacted by Aꞵ exposure [

58,

59]. Research has shown the impact that GSK3ꞵ has on the role of AD progression as the hyperfunction GSK3ꞵ is marked by common AD characteristics such as memory impairment and inflammatory responses [

59,

60]. This information could be used as a basis for future studies into the mechanisms by which we can combat the progression of AD.

Conclusion

AD is a devastating neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive cognitive decline, primarily driven by the accumulation of Aβ plaques, NFTs, synaptic dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and tissue atrophy. As the global population ages, finding effective treatments to slow or halt the progression of this disease is paramount. While statins offer a promising future for mitigating the underlying mechanisms of AD, the evidence of their effectiveness remains partially inconclusive. Limitations in literature lie in the common reliance on animal studies and the unknown side effects of statin use. Currently, investigations still reside primarily in animal model studies which show positive results with reduced inflammation and Aꞵ production but may not replicate the complexity of AD in humans. The mechanism of protection that would benefit human models still requires certification. The benefits of statin use for AD treatment must be weighed against the risks of side effects and uncertain future implications. As future research occurs, a more nuanced understanding of which AD patients may benefit from statin treatments is required. Future studies should prioritize larger scale, longitudinal studies in order to understand the effects of statins in more diverse populations and the true mechanism of action for more targeted prevention. At this time, statin treatments should be used with caution and as a more individualized approach for AD prevention and management.

Acknowledgments

We would like to give thanks Brian Piper, PhD, and Gia Fevrier, MBS, at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine for their support on this project.

Disclosures: There is no financial relationship between this paper’s authors and any institution mentioned.

Abbreviations

| Aꞵ |

Amyloid-ꞵ plaques |

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| ApoE |

apolipoprotein E |

| APP |

Amyloid precursor protein |

| BBB |

Blood-brain barrier |

| CGRP |

Calcitonin gene-related peptide |

| CSF |

Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DAMPs |

Danger-associated molecular patterns |

| FDDNP |

2-(1-{6-[(2-[fluorine-18]fluoroethyl)(methyl)amino]-2-naphthyl}-ethylidene)malononitrile |

| HDL |

High-density lipoprotein |

| HMG-CoA |

Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA |

| ICAM-1 |

Intracellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| LDL |

Low-density lipoprotein |

| LFA-1 |

Leukocyte function antigen-1 |

| MRS |

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy |

| NFTs |

Neurofibrillary tangles |

| O2·− |

Superoxide radical |

| PAMPs |

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| PIB |

Pittsburgh Compound B |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| SUVR |

Standardized uptake value ratio |

| TREM2 |

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 |

| VLDL |

Very low-density lipoprotein triglyceride |

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association; 2024.

- Madnani, R.S. Alzheimer’s disease: a mini-review for the clinician. Front Neurol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulep, M.G.; Saraon, S.K.; McLea, S. Alzheimer’s Disease. J Nurse Pract. 2022, 18, 778–781. [Google Scholar]

- Iwagami M, Qizilbash N, Gregson J, Douglas I, Johnson M, Pearce N, et al. Blood cholesterol and risk of dementia in more than 1·8 million people over two decades: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e498–e506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sizar, O.; Khare, S.; Patel, P.; Talati, R. Statin Medications. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Villemagne, V.L.; Rowe, C.C.; Macfarlane, S.; Novakovic, K.E.; Masters, C.L. Imaginem oblivionis: The prospects of neuroimaging for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2005, 12, 221–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, R.P.; Tepper, K.; Rönicke, R.; Soom, M.; Westermann, M.; Reymann, K.; et al. Mechanism of amyloid plaque formation suggests an intracellular basis of Aβ pathogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107, 1942–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Del Tredici, K. Encyclopedia of Movement Disorders. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press;2010.

- Brion, J.P. Neurofibrillary tangles and Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Neurol. 1998, 40, 130–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, J.B.; Ramsden, M.; Forster, C.; Sherman, M.A.; McGowan, E.; Ashe, K.H. Amyloid plaque and neurofibrillary tangle pathology in a regulatable mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2008, 173, 762–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-B.; Cho, S.-J. Multitracer PET imaging of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2008, 43, 236–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoghi-Jadid, K.; Small, G.W.; Agdeppa, E.D.; Kepe, V.; Ercoli, L.M.; Siddarth, P.; et al. Localization of neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid plaques in the brains of living patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002, 10, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, C.A.; Wang, Y.; Klunk, W.E. Imaging β-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the aging human brain. Curr Pharm Des. 2004, 10, 1469–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, I.A.; Kuznetsov, A.V. How the formation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles may be related: a mathematical modelling study. Proc Math Phys Eng Sci. 2018, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.-J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.-W. Role of oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed Rep. 2016, 4, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña-Bautista, C.; Baquero, M.; Vento, M.; Cháfer-Pericás, C. Free radicals in Alzheimer’s disease: Lipid peroxidation biomarkers. Clin Chim Acta. 2019, 491, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aruoma, O.I. Free radicals, oxidative stress, and antioxidants in human health and disease. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1998, 75, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Rottkamp, C.A.; Nunomura, A.; Raina, A.K.; Perry, G. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000, 1502, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, H.K.I.; Brown, C.L.R.; Polidori, M.C.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Griffiths, H.R. LDL-lipids from patients with hypercholesterolaemia and Alzheimer’s disease are inflammatory to microvascular endothelial cells: Mitigation by statin intervention. Clin Sci (Lond). 2015, 129, 1195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademowo, O.S.; Dias, H.K.I.; Milic, I.; Devitt, A.; Moran, R.; Mulcahy, R.; et al. Phospholipid oxidation and carotenoid supplementation in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017, 108, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, G.; Staurenghi, E.; Zerbinati, C.; Gargiulo, S.; Iuliano, L.; Giaccone, G.; et al. Changes in brain oxysterols at different stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Their involvement in neuroinflammation. Redox Biol. 2016, 10, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peskind, E.R.; Li, G.; Shofer, J.B.; Millard, S.P.; Leverenz, J.B.; Yu, C.-E.; et al. Influence of lifestyle modifications on age-related free radical injury to brain. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 1150–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calsolaro, V.; Edison, P. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: Current evidence and future directions. Alzheimers Dement. 2016, 12, 719–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Jiang, L. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015, 11, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; Khoury, J.E.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Saido, T.C. Neuroinflammation in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2018, 9, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaney, A.; Williams, S.R.; Boutin, H. In vivo molecular imaging of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2019, 149, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Song, X.; Zhu, C.; Patrick, R.; Skurla, M.; Santangelo, I.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and metabolic alterations in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis of in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Ageing Res Rev.

- Kumar, A.; Gupta, V.; Sharma, S. Donepezil. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Kuns, B.; Rosani, A.; Patel, P.; Varghese, D. Memantine. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Pirahanchi, Y.; Sinawe, H.; Dimri, M. Biochemistry, LDL Cholesterol. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Rosenson, R.S. Statins in atherosclerosis: Lipid-lowering agents with antioxidant capabilities. Atherosclerosis. 2004, 173, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, H.N. Effects of Statins on Triglyceride Metabolism. Am J Cardiol. 1998, 81, 32B–35B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, C.; Sima, A. Statins: mechanism of action and effects. J Cell Mol Med. 2001, 5, 378–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Most, P.J.; Dolga, A.M.; Nijholt, I.M.; Luiten, P.G.M.; Eisel, U.L.M. Statins: Mechanisms of neuroprotection. Prog Neurobiol. 2009, 88, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, K.R. Cholesterol Lowering Drugs. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA;2024.

- Sirtori, C.R. The pharmacology of statins. Pharmacol Res. 2014, 88, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, M.; Yarrarapu, S.N.S.; Dimri, M. Biochemistry, Cholesterol. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Tandon, V.; Bano, G.; Khajuria, V.; Parihar, A.; Gupta, S. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Indian J Pharmacol. 2005, 37, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie-Majd, A.; Prager, G.W.; Bucek, R.A.; Schernthaner, G.H.; Maca, T.; Kress, H.-G.; et al. Simvastatin reduces the expression of adhesion molecules in circulating monocytes from hypercholesterolemic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003, 23, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, M.; Mezzetti, A.; Marulli, C.; Ciabattoni, G.; Febo, F.; Di lenno, S.; et al. Fluvastatin reduces soluble P-selectin and ICAM-1 levels in hypercholesterolemic patients: Role of nitric oxide. J Investig Med. 2000, 48, 183–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Katoh, M.; Kurosawa, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Watanabe, A.; Doi, H.; Narita, H. Fluvastatin inhibits O2− and ICAM-1 levels in a rat model with aortic remodeling induced by pressure overload. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001, 281, H655–H660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, W.G.; Eckert, G.P.; Igbavboa, U.; Müller, W.E. Statins and neuroprotection: A prescription to move the field forward. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010, 1199, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, D.L.; Connor, D.J.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Petersen, R.B.; Lopez, J.; Browne, P. Circulating cholesterol levels, apolipoprotein E genotype and dementia severity influence the benefit of atorvastatin treatment in Alzheimer’s disease: Results of the Alzheimer’s Disease Cholesterol-Lowering Treatment (ADCLT) trial. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2006, 185, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, U.; Park, S.J.; Park, S.M. Cholesterol metabolism in the brain and its association with Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurobiol. 2019, 28, 554–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posse de Chaves, E.; Narayanaswami, V. Apolipoprotein E and cholesterol in aging and disease in the brain. Future Lipidol. 2008, 3, 505–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütjohann, D. Cholesterol metabolism in the brain: Importance of 24S-hydroxylation. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2006, 185, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennerholm, L.; Bostrom, K.; Jungbjer, B.; Olsson, L. Membrane lipids of adult human brain: lipid composition of frontal and temporal lobe in subjects of age 20 to 100 years. J Neurochem. 1994, 63, 1802–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saher, G. Cholesterol metabolism in aging and age-related disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2023, 46, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Calle, R.; Konings, S.C.; Frontiñán-Rubio, J.; García-Revilla, J.; Camprubí-Ferrer, L.; Svensson, M.; et al. APOE in the bullseye of neurodegenerative diseases: Impact of the APOE genotype in Alzheimer’s disease pathology and brain diseases. Mol Neurodegener. 2022, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alsubaie, N.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Alharbi, B.; De Waard, M.; Sabatier, J.-M. Statins use in Alzheimer disease: Bane or boon from frantic search and narrative review. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagliati, A.; Peek, N.; Brinton, R.D.; Geifman, N. Sex and APOE genotype differences related to statin use in the aging population. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2021, 7, e12156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geifman, N.; Brinton, R.D.; Kennedy, R.E.; Schneider, L.S.; Butte, A.J. Evidence for benefit of statins to modify cognitive decline and risk in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezakhani, L.; Salimi, Z.; Zarei, F.; Moradpour, F.; Khazaei, M.R.; Khazaei, M.; et al. Protective effects of statins against Alzheimer disease. Ewha Med J. 2023, 46, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, S.; Cao, D.; Parent, M. Isoprenoids and related pharmacological interventions: Potential application in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2012, 46, 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Torrandell-Haro, G.; Branigan, G.L.; Vitali, F.; Geifman, N.; Zissimopoulos, J.M.; Brinton, R.D. Statin therapy and risk of Alzheimer’s and age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2020, 6, e12108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, K.; Zhao, T.; Qu, G.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Sun, Y. The efficacy of statins in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Neurol Sci. 2020, 41, 1391–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wang, F.; Shi, Y.; Liu, L.; et al. Atorvastatin ameliorates cognitive impairment, Aβ1-42 production and Tau hyperphosphorylation in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Metab Brain Dis. 2016, 31, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.H. Amyloid beta-induced glycogen synthase kinase 3β phosphorylated VDAC1 in Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for synaptic dysfunction and neuronal damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013, 1832, 1913–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, C.; Killick, R.; Lovestone, S. The GSK3 hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2008, 104, 1433–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).