1. Introduction

An analysis of the current state of the agro-industrial complex (AIC), the industry's problems, a review of international experience, trends, and a vision for the industry's development, identifies freeze-drying as the most effective method. Long-term storage under uncontrolled temperature conditions is ensured because, after the entire freeze-drying cycle, the final moisture content of the dried materials is approximately 2-5% of the initial moisture content. The dried materials can be stored for an extended period without losing their beneficial properties, retaining their shape, color, taste, and nutrients. Freeze-drying can be conducted in a vacuum or atmospheric environment; however, at low temperatures and atmospheric pressure, the process is very slow. For this reason, vacuum drying is used to increase drying efficiency. By enhancing the mass transfer coefficient through pressure reduction, evaporation is significantly increased, which is inversely proportional to the pressure [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

12,

13,

15].

Vacuum drying occurs in a hermetically sealed chamber, resulting in low heat transfer through convection. Therefore, to increase the drying intensity in a vacuum, it is sufficient to raise the temperature to evaporate moisture by transferring heat to the dried product through a heated surface. The entire freeze-drying process consists of three main stages: freezing, sublimation, and secondary drying. In the first stage, the product's temperature is lowered to the freezing point, forming small ice crystals inside the product. During sublimation, the ice crystals evaporate, forming a vapor state. This stage significantly impacts product quality. The faster and deeper the product is frozen, the smaller the ice crystals form, causing less damage to tissues, which then quickly evaporate, resulting in better product quality preservation. The final period of the process, secondary drying, is conducted at positive temperatures [

3,

5,

6,

7,

14].

Berries, by their nature, are capillary-porous bodies; when moisture is removed, they become brittle, slightly changing their size and volume, and can be turned into powder. These materials are characterized by capillary-porous and colloidal properties. During drying, moisture removal from the material depends on the quantitative moisture content and the type of moisture binding with the material. It is necessary to perform work to remove 1 mole of water at a constant temperature while maintaining the same moisture composition. The binding energy is zero if the material contains free energy. As moisture decreases due to sublimation, the strength of the moisture binding with the material increases, and the binding energy rises. If the material's moisture is low, the binding energy is higher. Physical properties undergo changes during thermal processing of moist materials or when exposed to heat. These changes are based on the molecular nature, where the substance absorbs liquid. The transfer of absorbed liquid and vapor within a colloidal capillary-porous body depends on the molecular bond of the liquid with the skeleton substance [

1,

2,

3,

5,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

All types of bonds are divided into three large groups: chemical bonds, physicochemical bonds, and physico-mechanical bonds. All the above forms of moisture bonds are present in food products, but the type of bond plays an important role at different stages of product drying. Mechanically bound water is the weakest, held by filling macro- and micro-capillaries. This bond can be considered free moisture, removed as ice crystals during freeze-drying. It is more durable and firmly held on the surface and in the pores of the product. This bound moisture includes adsorption and osmotic water, and its removal during drying is associated with additional energy consumption for heat [

1,

2,

3,

7,

9,

13,

14,

15]. Chemically bound water has a very strong bond and is not removed during drying. It is essential to consider that plant raw materials, as drying objects, are characterized by high water content and relatively low dry matter content. Most of the water in fruits and vegetables is in a free state, with only 5% of the moisture firmly bound to cellular colloids, mainly consisting of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids. A small amount of biologically active substances that reflect the taste and biological value of raw materials are present, including polyphenols, vitamins, organic acids, and minerals [

3]. Below,

Table 1 lists the nutrients in the berries used in the studies.

Началo фoрмы

Кoнец фoрмы

2. Materials and Methods

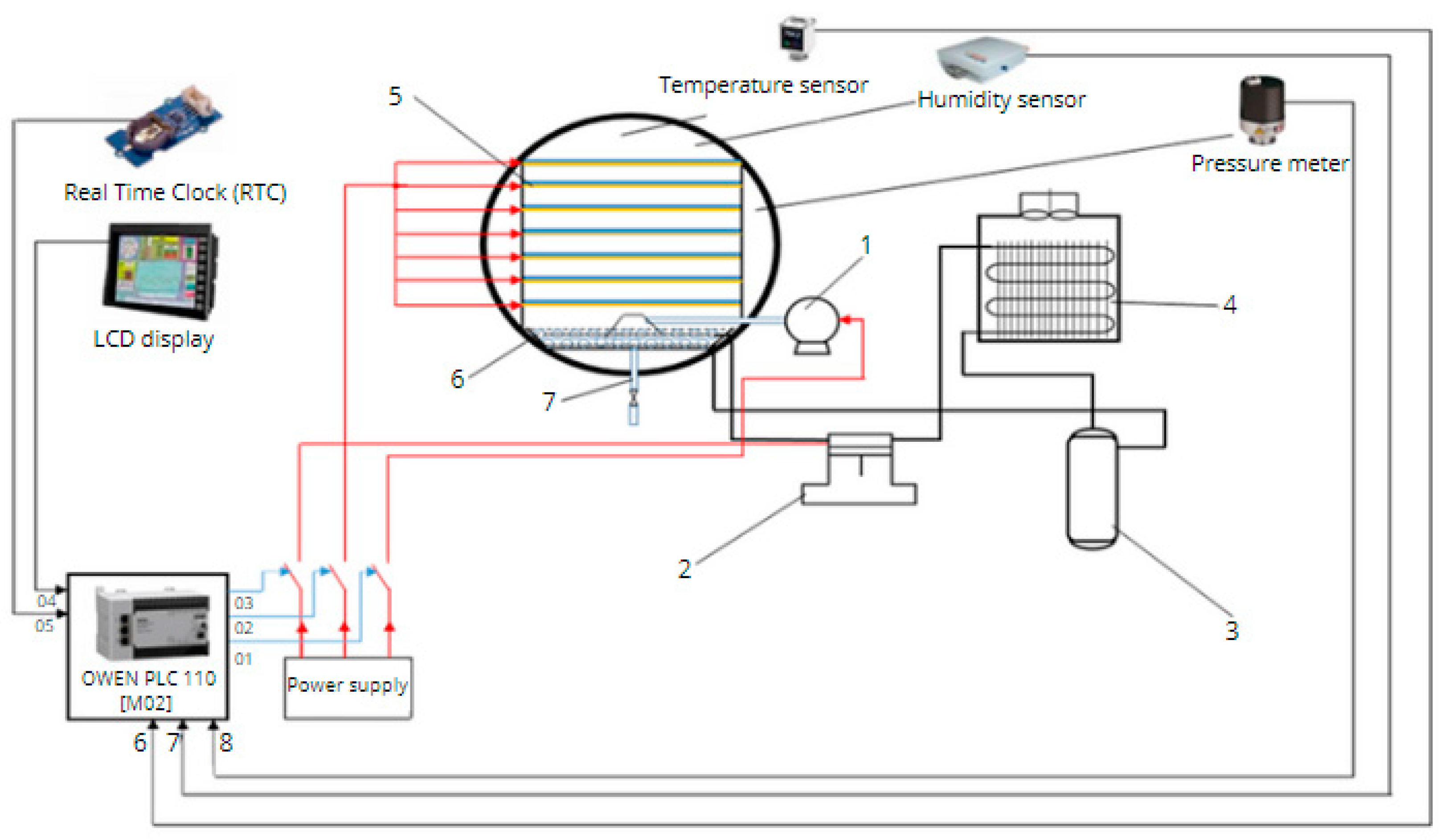

In this work, a lyophilizer "Alaman-1" was used, manufactured at the Department of "Energy Saving and Automation" of the Kazakh National Agrarian Research University. The appearance of this device is shown in

Figure 1. The modernized version differs with improved parameters of the drying chambers and the presence of heaters in them.

The sublimator works as follows. At room temperature, the product is placed in a drying chamber and frozen directly in the sublimator. The freezing rate of the product depends on the size of the ice crystals formed; they should not be too large as they may damage the structure, nor too small as this would prolong the sublimation process. Freezing the product at an air temperature of -30…-35°C or -50…-55°C, depending on the type of product, creates an acceptable ice crystal structure. To obtain a high-quality product, it is frozen to a temperature that ensures the removal of 75-80% of the moisture content. After turning on the vacuum pump, the pressure in the chamber is reduced to 10-30 Pa. The sublimation process then begins. As a result of sublimation, the vapor formed enters the desublimator, where it freezes on pipes cooled by a special agent. The exhausted air is removed from the chamber through a dust collection device and discharged into the atmosphere. At the final stage of the sublimation drying process, heating elements are activated to remove the remaining moisture. After the full drying cycle, the ice on the evaporator is melted using hot air, and the melted water is removed through a drain hole.

The cooling system of this sublimator uses freon 404a. The diagram of the automatic control system for the vacuum sublimation drying unit is shown in

Figure 2. For measuring, recording, and regulating temperature and pressure, a universal eight-channel measuring controller OVEN TRM138 was used. The product in the chamber was removed every thirty minutes, and its mass was measured with an accuracy of 0.1 mg using analytical scales VSL-200/0, 1 A.

The experiment was conducted on the following berries: strawberries, blackberries, raspberries. During the experiment, temperature readings on the surface and inside the berries, in the chamber, and the mass of the product were measured. The rational operating conditions for the equipment were determined by the drying duration, energy consumption, and the physicochemical quality indicators of the dried berries.

3. Results and Discussion

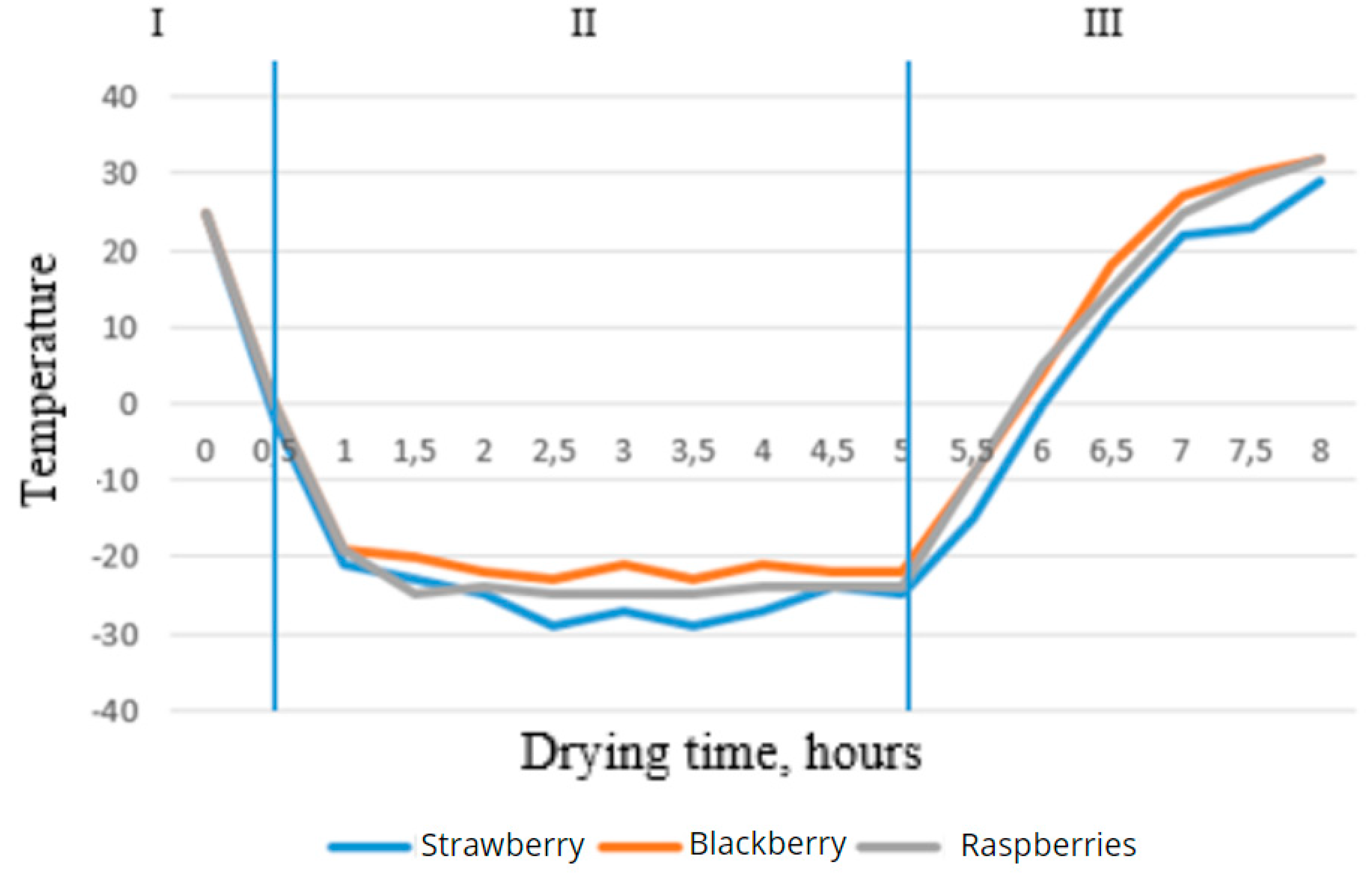

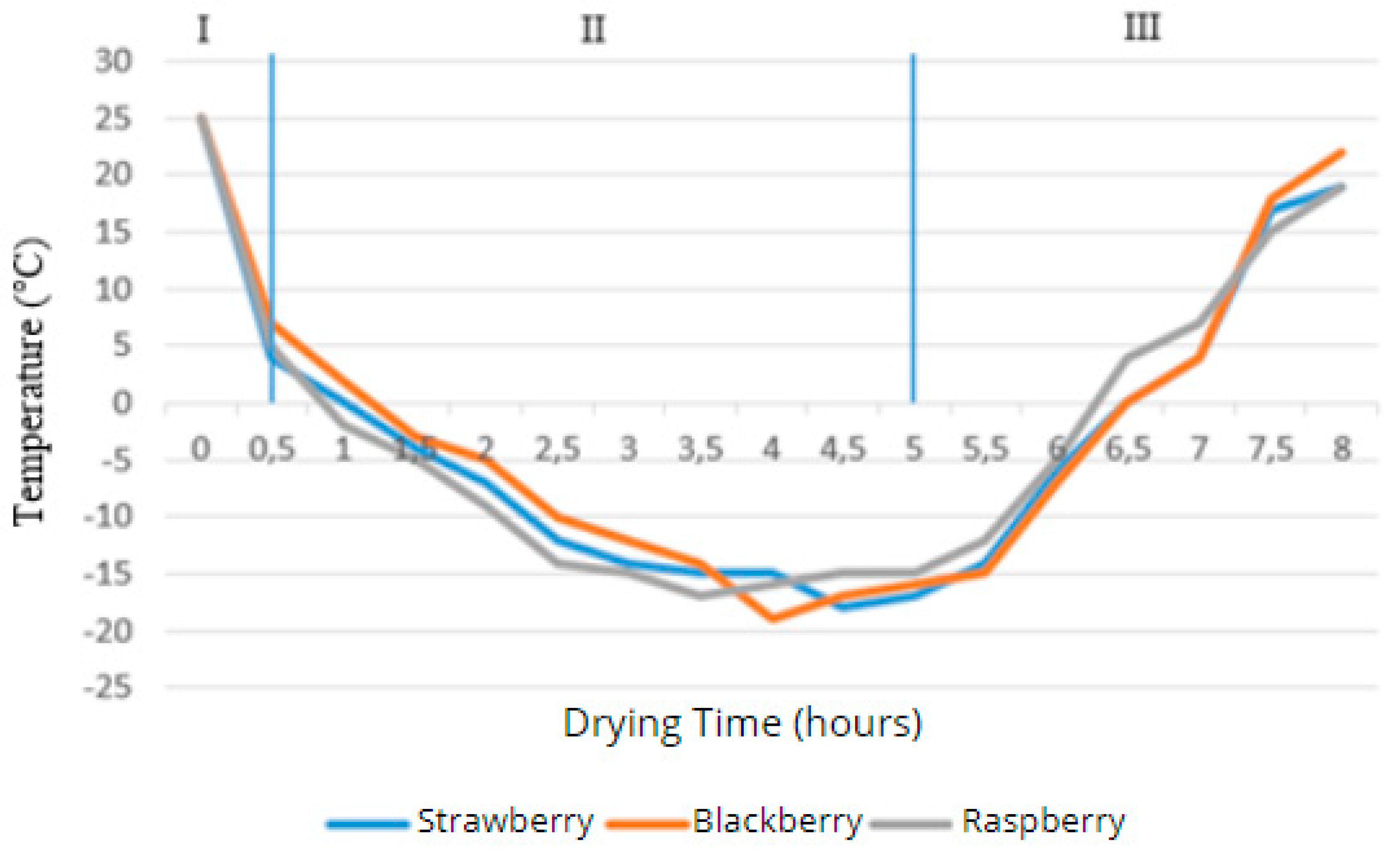

Based on the obtained results, graphs were constructed.

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the graphs of the temperature dependence of the product on the surface and in the center over the drying time.

Figure 3.

- Graph of the product surface temperature versus drying time.

Figure 3.

- Graph of the product surface temperature versus drying time.

Figure 4.

- Dependence of the product center temperature on drying time.

Figure 4.

- Dependence of the product center temperature on drying time.

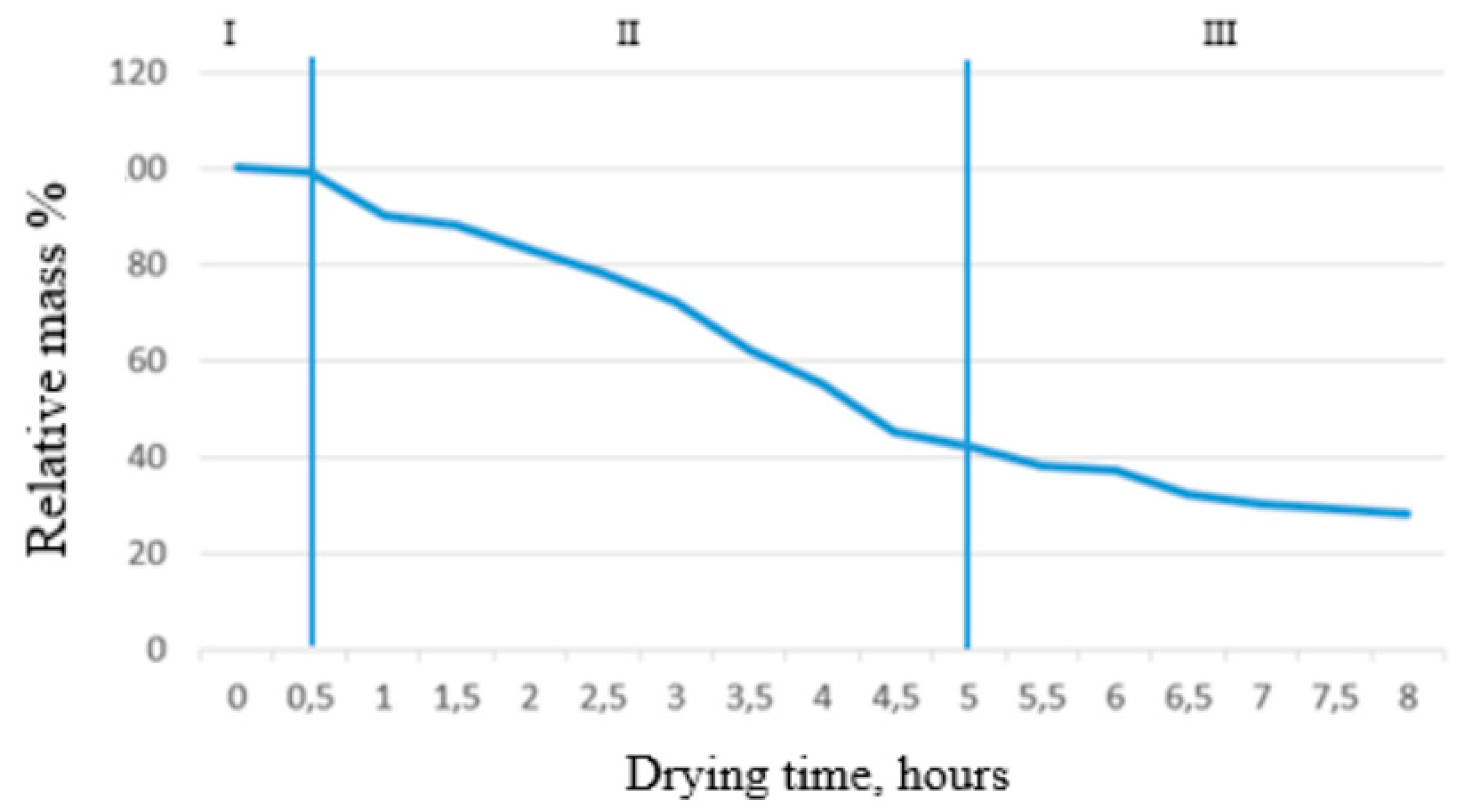

The entire process of vacuum drying, consisting of three stages, is shown in the graphs. The first stage is the freezing of the product at a temperature below its freezing point, characterized by a decrease in the product's temperature, as seen in the first graph. In the second stage, the product's temperature continued to drop due to the removal of liquid in the ice phase under low pressure. The temperature on the surface of the product stabilized between -25°C and -29°C after 2 hours, while the temperature in the middle of the product continued to decrease, reaching a critical value after 5 hours, as shown in the second graph. Thus, it was possible to sublime the berries in 4-5 hours. In the third stage, additional drying occurs through contact heating: the shelves with products are placed directly on a heating plate and heated via heat distribution. This process is characterized on the graphs by an increase in the product's temperature from the sublimation temperature to the drying temperature. Based on the collected data, a graph showing the relationship between the relative mass of strawberries and drying time is presented in Figure 4. As seen from the graph, during the shock freezing stage, the mass of the strawberries remained unchanged.

Figure 4.

- The dependence of strawberry mass on drying time.

Figure 4.

- The dependence of strawberry mass on drying time.

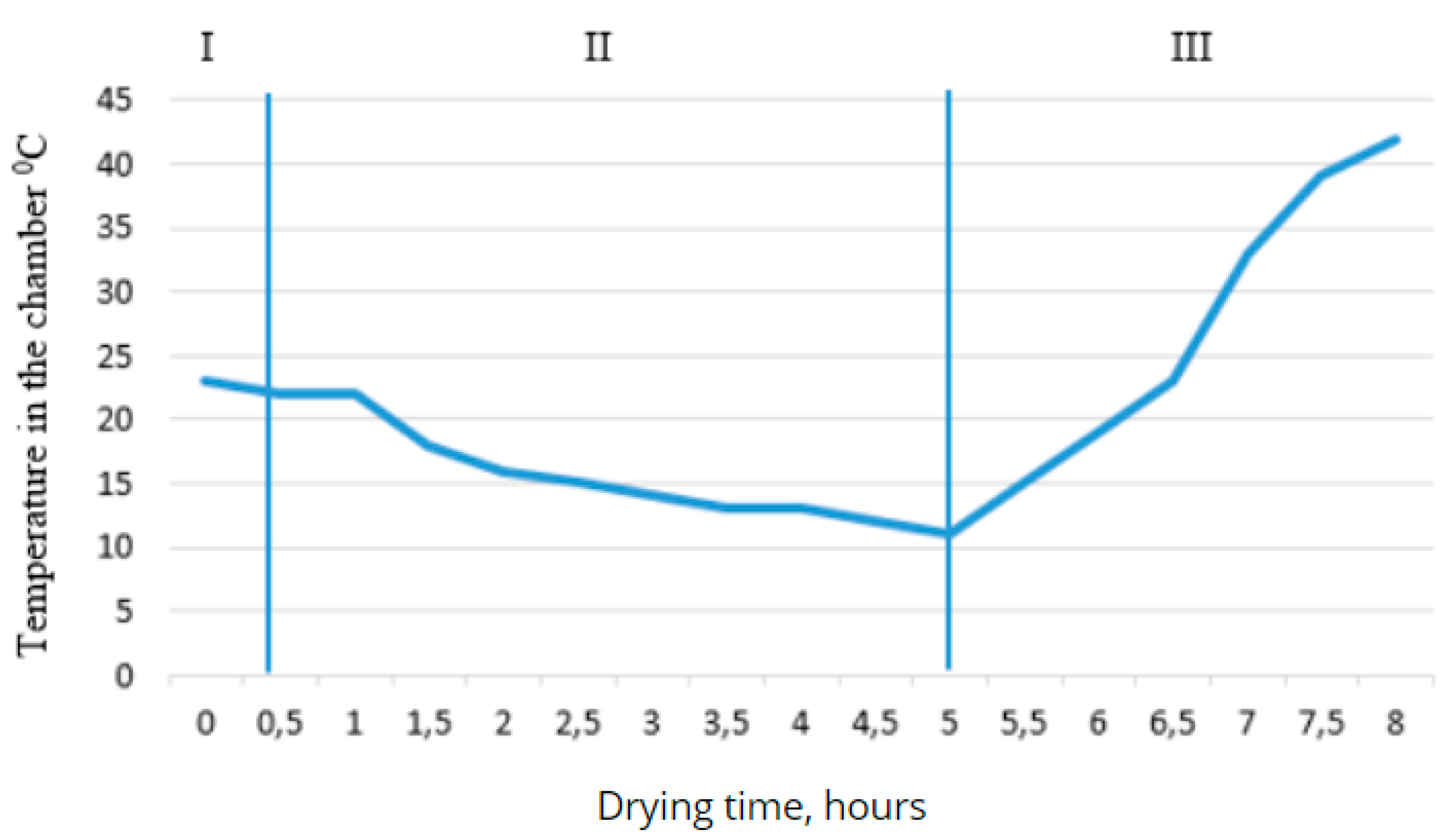

During the second stage of drying, the majority of moisture in the product was removed, accounting for 58% of the total mass. During the final drying process, the remaining portion of the most tightly bound moisture evaporated. After 6.5 hours, the relative mass of the strawberries did not change with time, indicating that almost all moisture had been removed from the product. Based on the graph, it can be concluded that the optimal drying time for this method is 7-8 hours. When the full drying cycle was completed, the final mass of the strawberries was 30% of the original, while for blackcurrants and honeysuckle it was 28% and 27%, respectively. Figure 5 and Figure 6 show the graphs of the temperature dependence in the chamber and evaporator. The final mass of the strawberries after complete drying was 28%, blackcurrants were 27.4%, and honeysuckle was 30.2%.

Figure 5.

- Dependence of the temperature in the chamber on the drying time.

Figure 5.

- Dependence of the temperature in the chamber on the drying time.

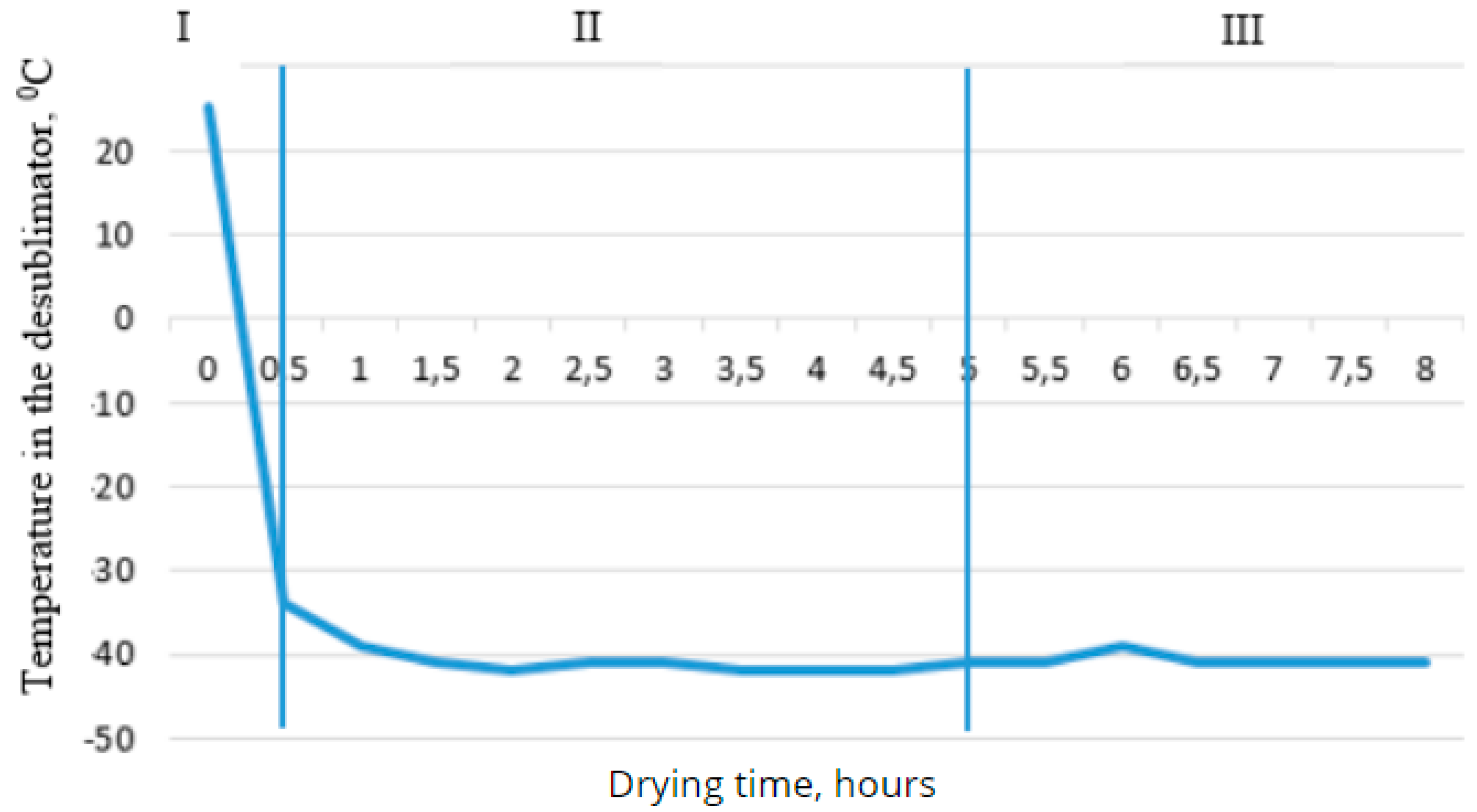

Figure 6.

- Dependence of the desublimator temperature on drying time.

Figure 6.

- Dependence of the desublimator temperature on drying time.

As can be seen from the graph, in the first stage, the temperature does not change, and throughout the full drying cycle, the temperature does not drop below 100°C. This is explained by the reduction of thermal conductivity and convection in vacuum conditions. At the same time, the temperature of the desublimator decreases to -36°C, causing the resulting water vapor to settle and turn into ice on the outer surface of the desublimator, thus reducing the pressure in the chamber. In the second stage of drying, the dependence of the desublimator's temperature on time becomes steady, with the temperature in the desublimator varying between -40°C and -42°C. The temperature in the chamber decreases to 110°C due to the phase transition of the water contained in the product from ice to vapor.

The curve on the first graph shows that after the heating system is turned on under vacuum, the temperature rises sharply. On the second graph, the temperature in the desublimator increases rapidly, and as a result, the control system automatically adjusts, supplying a larger volume of refrigerant to the desublimator, stabilizing the temperature. The outcome of the work was the determination of optimal parameters for the drying process of berries using this method. Based on the obtained data, it can be concluded that at a pressure of 20±5 Pa, the desublimator's temperature should be below -20°C. In practice, a temperature difference of 10°C is typically maintained, with the total drying time being around 8 hours. The surface temperature of the product during the sublimation stage should be within the range of -25±5°C.

Drying is completed when the chamber temperature reaches no more than 40°C and the product surface temperature is about 30°C. The optimal freeze-drying mode should ensure more complete removal of moisture during the preliminary freezing of the berries, a uniform release of vapors from the material due to a gentler temperature regime on the shelves during sublimation, and even drying of the material on all shelves. The time required for freeze-drying depends on the temperature, the specified thickness of the frozen material layer, the vacuum level in the chamber, and the properties of the material being dried.

4. Conclusions

The study of freeze-drying processes for berries is an important area in the technology of food processing and preservation. Understanding and controlling the parameters of freeze-drying allow for improved quality of the final product, which contributes to the development of new methods and technologies in this field.

References

- Abouelenein, D. Volatile Profile of Strawberry Fruits and Influence of Different Drying Methods on Their Aroma and Flavor: A Review // Molecules. 2023. № 15 (28). C. 1–20.

- Atak, A. Comparison of Important Quality Characteristics of Some Fungal Disease Resistance/Tolerance Grapes Dried with Energy-Saving Heat Pump Dryer // Agronomy. 2022. № 4 (12). C. 1–20.

- Bulgaru, V. Phytochemical, Antimicrobial, and Antioxidant Activity of Different Extracts from Frozen, Freeze-Dried, and Oven-Dried Jostaberries Grown in Moldova // Antioxidants. 2024. № 8 (13).

- Chua L., S. , Abd Wahab N. S. Drying Kinetic of Jaboticaba Berries and Natural Fermentation for Anthocyanin-Rich Fruit Vinegar // Foods. 2023. № 1 (12). C. 1–16.

- Cong, Y. Optimization and Testing of the Technological Parameters for the Microwave Vacuum Drying of Mulberry Harvests // Applied Sciences (Switzerland). 2024. № 10 (14).

- Čulina, P. Optimization of the Spray-Drying Encapsulation of Sea Buckthorn Berry Oil // Foods. 2023. № 13 (12). C. 1–20.

- Dalmau, E. , Araya-Farias M., Ratti C. Cryogenic Pretreatment Enhances Drying Rates in Whole Berries // Foods. 2024. № 10 (13).

- Emteborg, H. , Charoud-got J., Seghers J. Infrared Thermography for Monitoring of Freeze Drying Processes—Part 2: Monitoring of Temperature on the Surface and Vertically in Cuvettes during Freeze Drying of a Pharmaceutical Formulation // Pharmaceutics. 2022. № 5 (14).

- Ispiryan, A. , Kraujutiene I., Viskelis J. Retaining Resveratrol Content in Berries and Berry Products with Agricultural and Processing Techniques: Review // Processes. 2024. № 6 (12). C. 1–17.

- Kamanova, S. Effects of Freeze-Drying on Sensory Characteristics and Nutrient Composition in Black Currant and Sea Buckthorn Berries // Applied Sciences (Switzerland). 2023. № 23 (13).

- Tan, S. Hot Air Drying of Seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) Berries: Effects of Different Pretreatment Methods on Drying Characteristics and Quality Attributes // Foods. 2022. № 22 (11).

- Turan, B. Effect of Different Drying Techniques on Total Bioactive Compounds and Individual Phenolic Composition in Goji Berries // Processes. 2023. № 3 (11).

- Xu, Y. Characteristics and Quality Analysis of Radio Frequency-Hot Air Combined Segmented Drying of Wolfberry (Lycium barbarum) // Foods. 2022. № 11 (11).

- Yu, M. Evaluation of Blue Honeysuckle Berries (Lonicera caerulea L.) Dried at Different Temperatures: Basic Quality, Sensory Attributes, Bioactive Compounds, and In Vitro Antioxidant Activity // Foods. 2024. № 8 (13).

- Zhang, X. Sea Buckthorn Pretreatment, Drying, and Processing of High-Quality Products: Current Status and Trends // Foods. 2023. № 23 (12). C. 1–24.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).