1. Introduction

Identifying patients who need palliative care and providing timely palliative care to them has shown benefits to these patients and their families. The Supportive and Palliative Indicators Tool (SPICT) was developed by Boyd et.al in Scotland in 2010 for early identifying patients may be benefit from supportive and palliative care for a better treatment review, care plan discussion and end-of-life care. The SPICT comprises three parts, including measures to find out indicators for poor or deteriorating health, clinical indicators of life-limiting conditions and review current care and care planning [

1]. The SPICT has been translated to different languages [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6], and adapted in patients in different settings including acute wards in hospitals [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], primary care [

12,

13,

14] and care homes [

15].

Many patients with chronic conditions and limited functions are cared at home. These patients are often living with multiple chronic conditions, having complex needs and having higher risk of deterioration as well [

16,

17,

18]. Some of these patients receive home-based medical care (HBMC), including physician visits, skilled nursing care, and living care provided by medical care team from hospitals or healthcare agencies in the community [

19,

20]. In Taiwan, the HBMC services are reimbursed by the Integrated Home-Based Medical Care Program of the National Health Insurance [

21]. The program provides different levels of HBMC services for patients with different levels of needs. Because of HBMC patients are often having multiple comorbidities and frail, and they also have a high risk of deterioration [

22]. Therefore, timely identification of their palliative care needs and review the treatments, medications and care plans for these patients is warranted.

Although the SPICT has been validated in different languages and patients living in different settings, it has not been validated in patients receiving HBMC or in the context using traditional Chinese characters. Therefore, we aimed to validate the Taiwan version of the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT-TW) and to measure its ability to predict 6-month mortality in patients received HBMC in Taiwan.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Procedure

This study is a part of the HOme-based Longitudinal Investigation of the multidiSciplinary Team Integrated Care (HOLISTIC) [

23]. It comprised two steps, including the adaptation of the SPICT-TW and the examination of validity and reliability of the SPICT-TW among HBMC recipients. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of National Health Research Institutes in Taiwan (EC1080203, EC1080203-R1).

2.2. Adaptation of the SPICT-TW

Based on the recommendations of World Health Organization (WHO) [

24], we conducted the forward and backward translation of the original SPICT, including the seven general health indicators, a total of 23 clinical indicators for ten specific life-limiting illnesses, and five items for the guideline of palliative care approach to the patients. Following that, we piloted it among HBMC recipients via face-to-face interviews for the feasibility testing and then the expert panel compared the back-translated English version with the original version and made suggestions based on the results drawn from feasibility testing in addition to and modifications to the final version

2.3. The Validity and Reliability of the SPICT-TW

We explored the association between SPICT-TW scores and the six-month mortality after the date of study participation and evaluated the criterion-related validity, and intra-rater and inter-rater reliability (refer to statistical analysis section for detail) [

25]. Therefore, HBMC recipients in this study were evaluated with the SPICT-TW twice by healthcare professionals providing HBMC, such as physicians, nurses or social workers. The two assessments for each patient should be conducted by the same healthcare professional and the interval was less than one month. In order to examine the inter-rater reliability of the SPICT-TW, some patients were assessed by both the physician and another healthcare professional (e.g., nurse, or social workers) simultaneously at the two timepoints.

2.4. Other Measurements

Besides demographic characteristics, we additionally collected data about previous hospital utilisation, five-item WHO Well-Being Index (WHO-5), and Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) at baseline. The WHO-5 was assessed by five statements, which respondents rated according to the scale from “at no time” (0) to “all of the time” (5) in relation to the past two weeks [

26]. The total raw score ranged from 0 to 25. The score of 13 was used as the cut-point that the scores lower or higher than the cut-point represented the good and bad wellbeing respectively.

The CFS, a judgement-based frailty tool, generates a frailty score ranging from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill) by specific domains including comorbidity, function, and cognition [

27]. Participants were assessed with the CFS and categorized into four groups, including “without frailty/ mild frailty” (the score ≤ 5), moderate frailty (the score of 6), severe frailty (the score of 7) and “very severe to terminal ill” (the score of 8-9).

2.5. Participants

Seven from 18 HBMC agents in the HOLISTIC study (five clinics and two hospitals) participated in this validation study. We recruited patients aged ≥50 years who had been consistently receiving HBMC for more than two months, including two stages of services, provided by aforementioned seven HBMC agents. In Taiwan, the HBMC is mainly provided by physician visits for patients who have limited activities of daily living (Barthel index score less than 60) or who are difficult to visit healthcare agents due to disease conditions. The HBMC-Plus comprise physicians, nurse, respiratory therapist and pharmacist visits to patients whose disability is more severe than those in HBMC, having definite medical or nursing care needs such as “change tracheostomy set”, “urinal indwelling catheterization”, “insertion of nasogastric tube”, “bladder irrigation”, “wound treatment”, “intravenous drip”, and “colostomy irrigation” that assessed by both physicians and nurses and chronic conditions requiring long-term nursing care or continual post-discharge healthcare needs [

19].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were imported into Excel and managed and analyzed in SAS. We used the Kuder-Richardson 20 (KR-20), intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Cohen's kappa as indicators for internal consistency reliability, intra-rater reliability and inter-rater reliability respectively. The value of KR 20 was 0.7 or higher indicated an acceptable value of reliability. The value of ICC ≥ 0.7 was considered acceptable and while the value ≥ 0.90 was considered excellent[

28]. The value of kappa ≥ 0.6 was considered acceptable and while the value ≥ 0.80 was considered excellent [

29].

On the other hand, we conducted the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis for the predictive validity. The sensitivities and specificities at different numbers of indicators were individually presented. Both the area under the ROC curve (AUC) and Youden Index were used for determining the distinguishing ability of the scale and considering the optimal number of indicators for the cut-off point, whereas χ

2 test was used for the power of discrimination. We followed the suggestions by Hosmer and Lemeshow that 0.7 ≤ AUC< 0.8 indicated the acceptable discrimination and AUC ≥ 0.8 indicated the excellent discrimination [

30].

To examine the predictive power of optimal number of general health and clinical indicators in SPICT-TW on the follow-up six-month mortality, a multivariate logistic regression model was used after controlling the age, comorbidity, HBMC types, past-30 days hospitalization, WHO-5 wellbeing index, and CFS. Our findings and the suggested cut-off points were examined to compare the different predictive powers in SPICT-TW on the follow-up six-month mortality [

7].

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Background Information of Patients and Evaluators

In total, 129 HBMC recipients were assessed by 35 healthcare professionals (evaluators) with SPICT-TW. We excluded one patient because his two assessments were conducted by different persons. The characteristics of patients are shown in

Table 1. The average age was 82.4 years old (SD=12) and two-third of them had five or more comorbidities. Compared with the HBMC-Plus recipients, HBMC recipients had better wellbeing (p < .001) and less frailty (p < .001). Furthermore, the mainly common diseases were different between the HBMC patients and HBMC-Plus patients. Compared with the HBMC patients, the HBMC-Plus patients had higher percentage rates of pressure injury (46% vs 13%) and Parkinson’s disease (26% vs 12%). Hypertension was the most common disease in both HBMC and HBMC-Plus patients.

These 35 evaluators comprise 11 physicians (31.4%), 19 nurses (54.3%) and 5 other healthcare professionals (e.g., social workers or case managers) (14.3%) (

Table 2). Sixty % of them worked at hospitals and their median of work experience was 15 years (IQR: 4.6-24.5).

3.2. The Reliability and Validity of the SPICT-TW

Table 3 shows results of internal consistency reliability and intra-rater reliability. Overall KR-20 of the SPICT-TW scale ranging from 0.77 to 0.86 by evaluators in different disciplines indicated an acceptable value of internal consistency reliability. The value of ICC was 0.92 (95% CI 0.89-0.95) indicated consistency between the two assessments. Moreover, the inter-rater reliability was examined and values of Cohen's kappa were higher than 0.6 in most of indicators (86.7%).

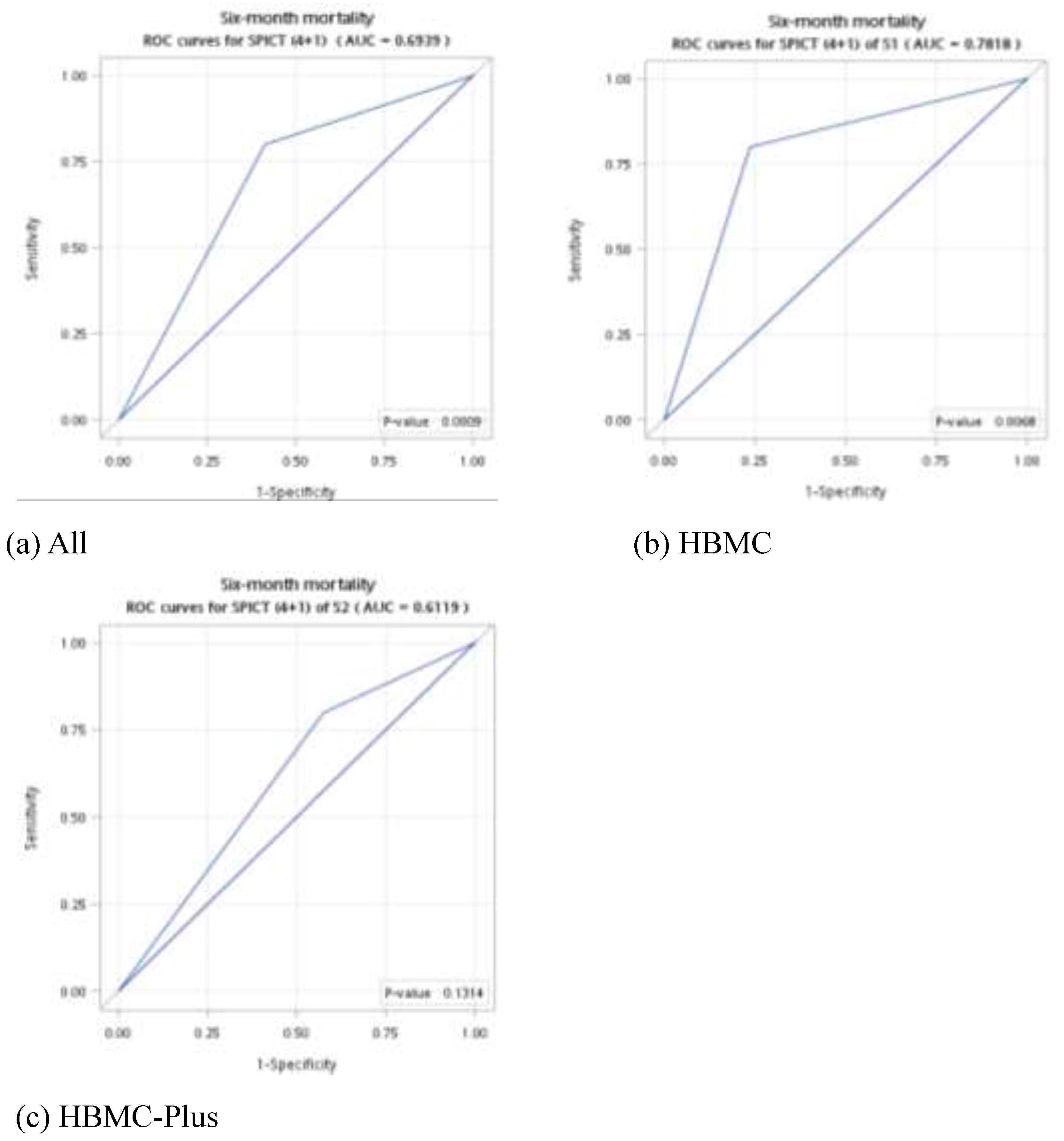

The sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of the number of general health indicators and clinical indicators are shown in

Table 4. The AUCs of general health indicators and clinical indicators were 0.73 and 0.61 respectively between patients with and without six-month mortality, indicating an acceptable validity. It was significant among general health indicators and a cut-off value of 4 for the general health indicators had the highest Youden index value. However, we found AUCs of clinical indicators is nonsignificant.

Using the optimal values for general health indicators and clinical indicators, we conducted the subgroup analysis of the ROC curve among HBMC patients and HBMC-Plus patients. The value of AUC among HBMC recipients was better than HBMC-Plus patients (0.78 vs 0.61) (

Figure 1).

3.3. Association between the SPICT-TW and Six-Month Mortality

The results of univariate and multivariate logistic regressions for predicting the six-month mortality are shown in

Table 5. We examined two models with different definition of SPICT-positive patients. In the model I, the SPICT-positive patients were identified with the aforementioned finding (a cut-off value of 4 for general health indicator and a cut-off value of 1 for clinical indicators) in the Taiwanese context. In the model II, the SPICT-positive patients were identified with a cut-off value of 2 for general health indicator and a cut-off value of 1 for clinical indicators based on the original identification approach of SPICT.

Based on the

Table 5, patients who were identified with a cut-off value of 4 for general health indicates and a cut-off value of 1 for clinical indicators in the SPICT-TW were at significantly higher risk of follow-up 6-month mortality (odds ratio (OR) = 8.30, p = 0.034). The other variables were not significant. It indicated that the SPICT-TW had the predictive power of acceptableness on the follow-up six-month mortality and its optimal cut-off number of indicators is a combination of four general health indicators and one clinical indicator.

4. Discussion

This is the first validation study of SPICT tool in the Taiwanese context using traditional Chinese characters and in the HBMC settings. The SPICT-TW demonstrated similar reliability and validity compared to other language versions of SPICT. It may be an appropriate tool for healthcare professionals to timely detect the needs of palliative care in the older people who received home healthcare. Furthermore, we found that a combination of four general indicators and a clinical indicator in SPCIT-TW have the best prediction ability at predicting 6-month mortality in these HMBC recipients.

Based on the findings of reliability, the internal consistency reliability of SPICT-TW was assessed by the KR-20 and found the acceptable results that was consistent with the previous study in Europe [

2]. We additionally found that it was not affected by different disciplines of healthcare professionals (e.g., physicians, nurses, and social workers) in any time. Both the intra-rater reliability and inter-rater reliability were examined and found with the good level, indicating that the assessment via the SPICT-TW was consistent and reliable.

Studies demonstrated that SPICT has good value of identifying older patients at high risk of health degradation and mortality, although the tool was not developed for prognostic purpose [

8,

10,

31]. In this study, comparing to previous hospitalisation, WHO-5, CFS, or numbers of comorbidities, SPICT-TW positive was the only one significant scale associated with six-month mortality in the multivariable analysis. However, we found that a cut-off point of four general health indicators plus one clinical indicator in SPICT-TW had better association with six-month mortality in Taiwanses cohort. De Bock et al. conducted a retrospective cohort study in Belgium and found that, among inpatients of acute geriatric ward at a university hospital, a cut-off value of two general indicators and a clinical indicator in SPICT successfully predicted one-year mortality with a sensitivity of 0.841, and AUCs of the general indicators (0.76) and the clinical indicators of SPICT (0.75) did not significantly differ [

8]. In contrast, among HBMC patients in our study, in which the conditions are chronic and may be less unstable so that we need more general indicators of SPICT-TW to increase the value of survival prediction. Furthermore, regarding the association with six-month mortality, the AUCs of the general indicators (0.73) in our study was higher than clinical indicators (0.61).

HBMC-Plus patients were significantly frail and having poor well-being than HBMC patients, and the SPICT-TW 4+1 was found to have better prediction of 6-month mortality in HBMC than HBMC-Plus patients. There might have complex mechanisms for this association, including the type of comorbidity, the severity of comorbidity and the functional status of these patients, the frequency of condition fluctuations, and etc. It may also reveal that HBMC and HBMC-Plus are different patient groups, indicating that while considering the follow-up six-month mortality, we should consider different combinations of general indicators and clinical indicators. Moreover, for early identification of palliative care needs, further evaluation of HBMC and HBMC-Plus patients who living with different comorbidity or multimorbidity, and their psychosocial and spiritual well-being should be considered by comprehensive assessments.

The strength of our study resides in its enrollment from a national cohort, employing stratified sampling across Taiwan, and enhances the generalizability of its findings. The involvement of diverse healthcare professionals, including physicians, nurses, and social workers, ensures that the SPICT-TW's reliability and applicability were tested across different disciplines. Additionally, the study in HBMC settings provides practical insights, particularly for elderly patients with multiple chronic conditions. However, there are still several limitations. Firstly, the study focused on six-month mortality, which may not capture long-term outcomes and the full impact of palliative care interventions initiated based on SPICT-TW assessments. Secondly, severity of diseases or clinical conditions related to mortality were not evaluated which might be underestimated the patients' needs of palliative care. Thirdly, although efforts were made to ensure consistency, the subjective nature of some assessments could introduce bias, particularly in the inter-rater reliability evaluations. Finally, while the study assessed mental well-being using the WHO-5 Well-Being Index, it did not evaluate patients' spiritual well-being, which can be a significant component of palliative care.

5. Conclusions

This multicenter study validated the SPICT-TW for among HBMC recipients in Taiwan. SPICT-TW demonstrated high reliability and validity, and may be a practical tool identifying older people at risk of dying within six months who would be benefit from palliative care. Future research should explore the effectiveness of SPICT in initiating timely palliative care and its practical value for the patients’ quality of life, symptoms improvement, and caregiver burden.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jung-Yu Liao, Hsiao-Ting Chang and Ping-Jen Chen; Data curation, Jung-Yu Liao, Hsiao-Ting Chang, Jen-Kuei Peng and Hsien-Cheng Chang; Formal analysis, Hsiao-Ting Chang and Wei-Zhe Tseng; Funding acquisition, Hung-Yi Chiou and Ping-Jen Chen; Methodology, Jung-Yu Liao, Jen-Kuei Peng and Ping-Jen Chen; Project administration, Wei-Zhe Tseng; Supervision, Chao Hsiung, Hung-Yi Chiou and Ping-Jen Chen; Validation, Scott A Murray and Chien-Yi Wu; Visualization, Wei-Zhe Tseng; Writing – original draft, Jung-Yu Liao, Hsiao-Ting Chang, Jen-Kuei Peng, Scott A Murray, Chien-Yi Wu, Hsien-Cheng Chang, Chia-Ming Li, Shao-Yi Cheng, Chao Hsiung, Hung-Yi Chiou, Sang–Ju Yu, Kirsty Boyd and Ping-Jen Chen; Writing – review & editing, Scott A Murray, Chien-Yi Wu, Hsien-Cheng Chang, Chia-Ming Li, Shao-Yi Cheng, Chao Hsiung, Sang–Ju Yu and Kirsty Boyd.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Health Research Institutes [PH-108-GP-04 and PH-109-GP-04], National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan (112-2410-H-037-005-MY3), and a grant from the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital [KMUH112-2R77]. The sponsor played no role in the design, methods, data collection, analysis, or preparation of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of National Health Research Institutes in Taiwan (EC1080203, EC1080203-R1). Trial registration number: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier is NCT04250103 which has been registered on 31st January 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to technical limitations. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to National Health Research Institutes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boyd K, Murray SA: Recognising and managing key transitions in end of life care. BMJ, 2010; 341, c4863.

- Fachado AA, Martínez NS, Roselló MM, Rial JJV, Oliver EB, García RG, García JMF: Spanish adaptation and validation of the supportive & palliative care indicators tool - SPICT-ESTM. Rev Saude Publica, 2018; 52, 3.

- Afshar K, Feichtner A, Boyd K, Murray S, Jünger S, Wiese B, Schneider N, Müller-Mundt G: Systematic development and adjustment of the German version of the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT-DE). BMC Palliat Care, 2018; 17, 27.

- Casale G, Magnani C, Fanelli R, Surdo L, Goletti M, Boyd K, D'Angelo D, Mastroianni C: Supportive and palliative care indicators tool (SPICT™): content validity, feasibility and pre-test of the Italian version. BMC Palliat Care, 2020; 19, 79.

- Sripaew S, Fumaneeshoat O, Ingviya T: Systematic adaptation of the Thai version of the supportive and palliative care indicators tool for low-income setting (SPICT-LIS). BMC Palliat Care, 2021; 20, 35.

- Bergenholtz H, Weibull A, Raunkiær M: Supportive and palliative care indicators tool (SPICT™) in a Danish healthcare context: translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and content validation. BMC Palliat Care, 2022; 21, 41.

- Highet G, Crawford D, Murray SA, Boyd K: Development and evaluation of the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT): a mixed-methods study. BMJ Support Palliat Care, 2014; 4, 285–290.

- De Bock R, Van Den Noortgate N, Piers R: Validation of the supportive and palliative care indicators tool in a geriatric population. J Palliat Med, 2018; 21, 220–224.

- Mudge AM, Douglas C, Sansome X, Tresillian M, Murray S, Finnigan S, Blaber CR: Risk of 12-month mortality among hospital inpatients using the surprise question and SPICT criteria: a prospective study. BMJ Support Palliat Care, 2018; 8, 213–220.

- Piers R, De Brauwer I, Baeyens H, Velghe A, Hens L, Deschepper E, Henrard S, De Pauw M, Van Den Noortgate N, De Saint-Hubert M: Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool prognostic value in older hospitalised patients: a prospective multicentre study. BMJ Support Palliat Care, 2021; bmjspcare-2021-003042.

- Effendy C, Silva JFDS, Padmawati RS: Identifying palliative care needs of patients with non-communicable diseases in Indonesia using the SPICT tool: a descriptive cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care, 2022; 21, 13.

- Mitchell GK, Senior HE, Rhee JJ, Ware RS, Young S, Teo PC, Murray S, Boyd K, Clayton JM: Using intuition or a formal palliative care needs assessment screening process in general practice to predict death within 12 months: A randomised controlled trial. Palliat Med, 2018; 32, 384–394.

- van Wijmen MPS, Schweitzer BPM, Pasman HR, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD: Identifying patients who could benefit from palliative care by making use of the general practice information system: the Surprise Question versus the SPICT. Fam Pract, 2020; 37, 641–647.

- van Baal K, Wiese B, Müller-Mundt G, Stiel S, Schneider N, Afshar K: Quality of end-of-life care in general practice – a pre–post comparison of a two-tiered intervention. BMC Prim Care, 2022; 23, 90.

- Liyanage T, Mitchell G, Senior H: Identifying palliative care needs in residential care. Aust J Prim Health, 2018; 24, 524–529.

- Mondor L, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB, Bronskill SE, Gruneir A, Lane NE, Wodchis WP: Multimorbidity and healthcare utilization among home care clients with dementia in Ontario, Canada: A retrospective analysis of a population-based cohort. PLoS Med, 2017; 14, e1002249.

- Harrison KL, Leff B, Altan A, Dunning S, Patterson CR, Ritchie CS: What's happening at home: a claims-based approach to better understand home clinical care received by older adults. Med Care, 2020; 58, 360–367.

- Ritchie CS, Leff B: Population health and tailored medical care in the home: the roles of home-based primary care and home-based palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2018; 55, 1041–1046.

- Chang HT, Lai HY, Hwang IH, Ho MM, Hwang SJ: Home healthcare services in Taiwan: a nationwide study among the older population. BMC Health Serv Res, 2010; 10, 274.

- Landers S, Madigan E, Leff B, Rosati RJ, McCann BA, Hornbake R, MacMillan R, Jones K, Bowles K, Dowding D et al: The future of home health care: a strategic framework for optimizing value. Home Health Care Manag Pract, 2016; 28, 262–278.

- Shih CY, Chen YM, Huang SJ: Survival and characteristics of older adults receiving home-based medical care: A nationwide analysis in Taiwan. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2023; 71, 1526–1535.

- Su MC, Chen YC, Huang MS, Lin YH, Lin LH, Chang HT, Chen TJ: LACE score-based risk management tool for long-term home care patients: a proof-of-concept study in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18.

- Liao JY, Chen PJ, Wu YL, Cheng CH, Yu SJ, Huang CH, Li CM, Wang YW, Zhang KP, Liu IT et al: HOme-based Longitudinal Investigation of the multidiSciplinary Team Integrated Care (HOLISTIC): protocol of a prospective nationwide cohort study. BMC Geriatr, 2020, 20(1):511.

- World Health Organization. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. 2009 [http://www who int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/ 2009].

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL: Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 1979, 86(2):420-42.

- Bonsignore M, Barkow K, Jessen F, Heun R: Validity of the five-item WHO Well-Being Index (WHO-5) in an elderly population. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2001, 251 Suppl 2:Ii27-31.

- Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A: A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ, 2005, 173(5):489-495.

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL: Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 1979, 86(2):420.

- McHugh ML: Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb), 2012, 22(3):276-282.

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX: Applied Logistic Regression; 2013.

- Bourmorck D, de Saint-Hubert M, Desmedt M, Piers R, Flament J, De Brauwer I: SPICT as a predictive tool for risk of 1-year health degradation and death in older patients admitted to the emergency department: a bicentric cohort study in Belgium. BMC palliat care, 2023, 22(1):79.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).