Introduction

The complexities of the human birthing process stem from the unique shape of the pelvis from human evolution. The shape of the human female pelvis is described as a compromise, or evolutionary trade-off, between a shape optimized for bipedal locomotion and a morphology optimized for birthing of fetuses with relatively large heads due to an encephalization process occurred during the last millions of years of our evolution. This trade-off hypothesis, known as the "obstetric dilemma" (OD) hypothesis, was proposed by researchers such as Washburn: a large pelvis limits functional bipedalism, and a pelvis too narrow impedes an uncomplicated vaginal delivery [

1]. That is, the assumption became that the female pelvis is a tradeoff between the two, settling for a size that allows bipedal walking and birthing without facing a serious disadvantage. If not for this compromise, birthing would not be a favorable process leading to a low fitness for the mother [

2].

Medically, of the causes of maternal morbidity and mortality, pelvis size is often implicated in obstructed labor, a failure of labor to progress due to mechanical reasons. Fetopelvic disproportion is the primary cause of obstructed labor and is the ratio between the baby's limiting factor in size, typically the head circumference or shoulder girdle width, to the mother's pelvis [

3]. The proposition of the OD hypothesis satisfied the reasoning behind fetopelvic disproportion. However, more recently, other factors, including genetics, metabolic factors, and nutrition, have shown to impact the mother's and fetus's physiology and anatomy aiming to explain why the fetopelvic disproportion occurs, including rapid environmental changes, phenotypic plasticity, and biocultural factors [

4,

5,

6]. In a sense, this is related to a very important change that has been occurring in the field of evolutionary biology in the past decades: more and more researchers - including some of the authors of this paper - are becoming part of a major change from a more reductionist and often genetic-centric Neo-Darwinian approach to a more encompassing view of life, often described as an

Extended Evolutionary Synthesis, in which organismal behavior, niche construction and epigenetics are seen as crucial aspects of evolution together with genetics [

7,

8].

It is therefore important that evolutionary medicine, and in particular discussions on the causes of fetopelvic disproportion, start to take into consideration such new ideas and factors such as socioeconomic and ethnic disparities, as this might lead to a more comprehensive understanding, and therefore a potential decrease, of the occurrence of obstructed labor and the need for surgical intervention during births. For instance, in recent years there has been a significant increase in the percentage of babies that are born from Cesarean sections (CS), within numerous countries, including the U.S. [

9]. Originally, such a practice was mostly done in severe cases of obstructed labor, in which surgical intervention would replace vaginal birth to prevent the sequelae of the baby being halted in the birth canal including asphyxiation, stillbirth and neonatal jaundice [

10]. However, the steady rise in Cesarean sections rates worldwide has been criticized, as this practice is primarily for problematic deliveries that could put both the mother and the baby at risk. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends CS rates of 15% worldwide – that is, corresponding to the number that, in average, is truly needed to save the life of, or reduce risks to, the mother and/or baby: however in the U.S. the yearly CS rate of all births has been up to 32% and higher in other countries worldwide, with Brazil being up to 40%. In recent years, there is great disparity in the rate of CS across ethnic groups, with African American women having significantly higher rates of CS [

9,

11]. Disparities in Cesarean section rates among Native American and Latino women are also influenced by socioeconomic factors, access to healthcare, and implicit biases within medical institutions. These factors contribute to a higher prevalence of Cesarean deliveries in these communities, mirroring the trends observed in African American women [

12]. Therefore, it is crucial, and timely, to have a new, more holistic perspective going in line with recent developments and ideas in the fields of evolutionary biology and evolutionary medicine when examining the very complex and intricate causes of fetopelvic disproportion. The main aim of this review is to provide, for the first time, a clear, succinct analysis of factors including genetics, nutrition, and how it contributes to ethnic disparities in obstructed labor to pave the way for more discussions on this important topic by academics, medical practitioners and researchers, and the broader public.

Evolution

In the 1960s through the 1980s, the OD hypothesis was the most popular theory describing the difference between non-human primates and human birthing. Washburn generalized that non-human primates could birth 'uncomplicatedly', requiring little to no assistance to have a successful birth [

1]. Conversely, humans often require multiple attendees to facilitate a safe and successful delivery. To understand the complexities of the human birthing process, the non-human primate and human pelvis must be understood. In non-human primates, the birth canal is shorter and less tube-like, described as a ring. This structure is less complex than the human canal as it provides more space for the fetus to pass [

13]. In humans, the measurement differences between various axes within and the canal's shape are described as a truncated bent cylinder [

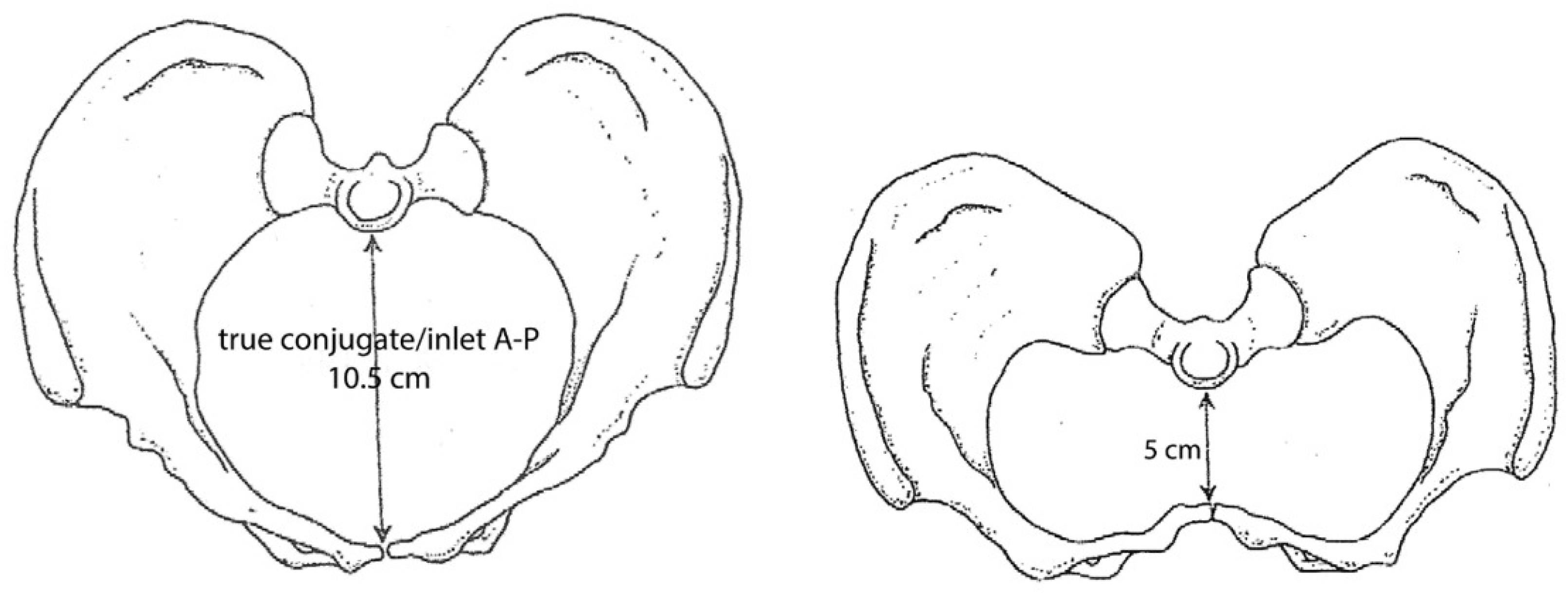

14]. The human pelvis is structured with three planes that form the birth canal: the inlet, midplane and outlet (

Figure 1) [

15]. The female pelvis has a wider sagittal dimension and transverse plane than the male pelvis [

16]. In humans, the baby moves through the birth canal with a complex series of movements known as the 'seven cardinal movements of labor' [

17]. Therefore, measurements in the order of millimeters implicate birth considering the rotations a baby does to get through the canal, which can pose more difficulties that could cause pathological issues for both the mother, such as urogenital fistulas and levator ani tearing.

In primates in general, and humans in particular, pelvis shape is sexually dimorphic and changes over time according to estradiol levels; the size of the pelvis changes to "prime" for birthing when a female reaches reproductive age [

18]. Although the obstetric dilemma stated a locomotor and obstetric tradeoff compared to male pelvises, it is suggested that after a female passes 40 years of age, the female pelvis becomes increasingly male-like [

18]. Males do not have pelvic changes over time, and pelvis growth and development are somatic from sex-influenced autosomal genes causing hormonal changes [

18]. These short-term changes cause expansion and reversal patterns to change the distance between ischial spines are suggested as the cause for the obstructed labor but necessary to support the abdominopelvic cavity during the pregnancy.

In hominins - the taxonomic group including all humans, including our ancestors after they split from the chimpanzee lineage -, evidence for bipedalism occurred before encephalization, and the cranial capacity of

Homo has increased substantially in the last 600,000 years [

19]. The pelvis is disproportionate to the size of the human fetus as the cranial capacity and body size are not much different from other newborn primates [

20]. The human fetus is twice as large in relation to its mother's weight compared to primates of similar size, making it an outlier for female human capacity. Additionally, human infants have accelerated brain growth outside the womb, known as secondary altriciality, where human brains are 30% less developed than other primates when birthed [

21,

22]. The demands of the size of the womb favored fetuses in earlier development in order to fit through the narrow birth canal; therefore, a fetus' head grows significantly after birth [

22].

Metabolics, Nutrition, and Socio-Economic Factors

Environmentally, nutrition contributes to obstructed labor as micronutrients are crucial for good skeletal development and are linked to a successful pregnancy. Food access can depend on one's culture, upbringing, socioeconomic status and availability of healthy food. The term ‘food desert’ is used to describe an area with little access to healthful food. It is important to note that communities with less access to healthy foods are at a higher risk of having compromised bone development [

23]. Additionally, a study analyzing women who delivered at Loyola University Medical Center showed the odds of having at least one morbid condition in pregnancy increased for patients living in a food desert [

24]. Unfortunately, nutritional access has its own ethnic disparity as African-Americans are 38% more likely to report living in a food desert [

25].

An essential nutrient supporting skeletal development is vitamin D. During the emergence of agricultural practices during the Neolithic revolution, deformities of the pelvises were prominent due to weak and poorly mineralized bone. Pre-agricultural diets consisted of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet but farming introduced a major reduction in the diversity of consumed food, and post-agricultural methods turned to a low-protein, high-carbohydrate diet [

13]. Several bioarcheological studies note locations such as the Middle East and Europe during the Neolithic revolution experienced nutritional deficiencies and a resultant decrease in stature [

26,

27,

28].

Evidence from calcium and vitamin D deficiencies is associated with a higher risk of Cesarean sections [

29]. Severe vitamin D deficiency leads to rickets and osteomalacia in adults, and those during the industrial revolution had low sunlight exposure and a diet lacking in diversity. Consequently, osteomalacia and rickets were the most severe risk factor for maternal death until the 20th century; pelvises were deformed and the shape did not allow for an easy canal for the baby to pass through [

30,

31]. The most severe cases led to rachitic pelvises, characterized by deformities that made the birth canal misshapen, making it difficult or impossible for the fetus to exit the birth canal. Rickets allowed for the body's weight and pull of muscles to produce a flat pelvis anteroposteriorly [

32,

33].

Figure 2 shows a comparison of normal pelvis shape and a contracted pelvis impacted by rickets [

6].

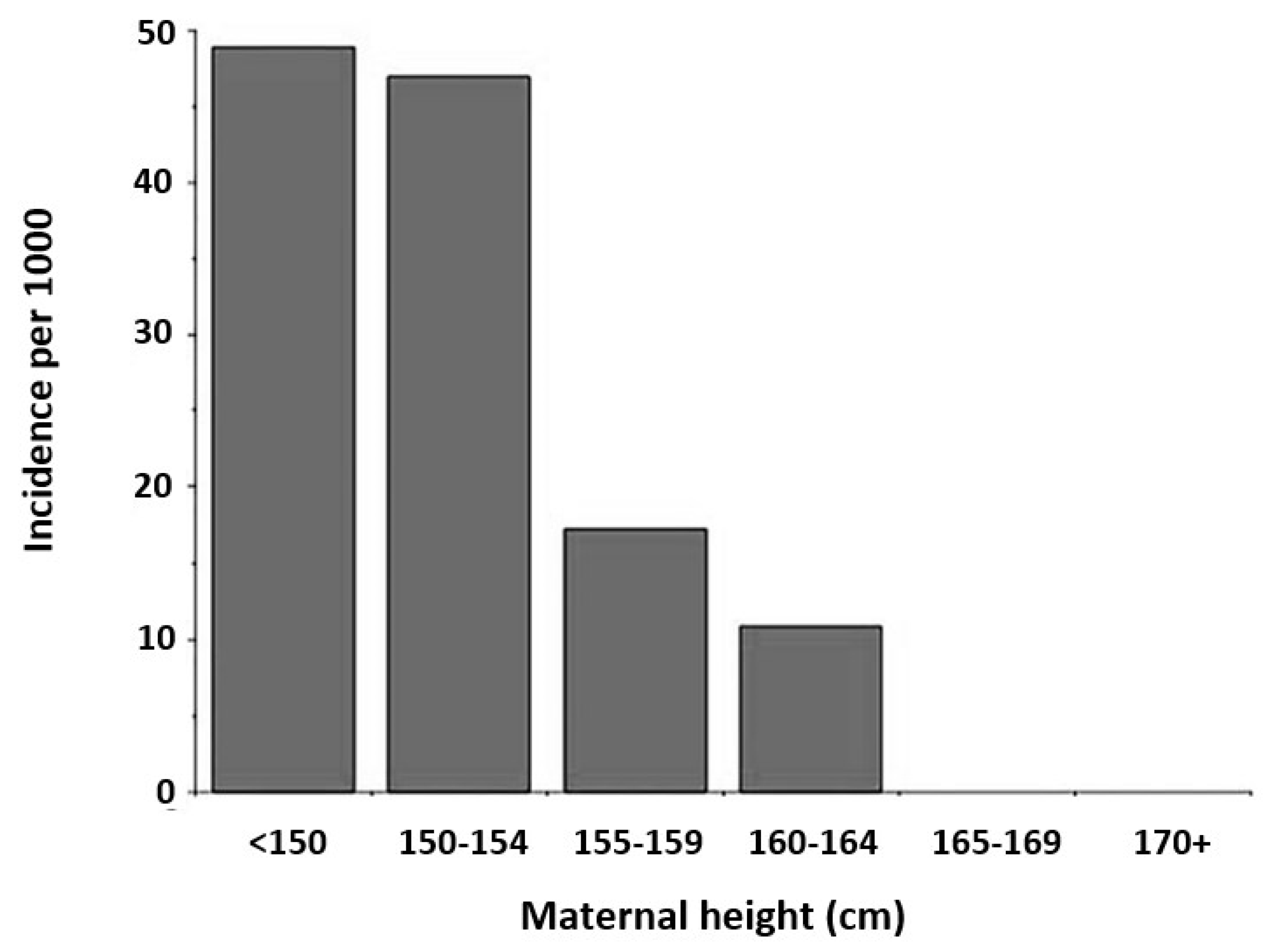

Micronutrient deficiency is still prominent in influencing both maternal and fetal growth. Mothers who grew up experiencing under-nutrition showed shorter stature and improper pelvic growth, where short stature has a known association with smaller and flatter pelvises [

34]. The association of higher risk with obstructed labor and shorter maternal height has been identified from a study completed in Burkina Faso (

Figure 3) [

35,

36]. Mothers below the 20th percentile for height show increased risk of cephalopelvic disproportion [

36,

37,

38].

In regard to overnutrition, there is a complex association between obesity and income. In women studied in the United States, obesity prevalence decreased among women with increased educational levels and average income levels [

39]. Those who identified as men had a more complex association. In contrast, women had a clearer distinction based on their education and income levels relative to the federal poverty level [

39].

Obesity is prevalent in 41.9% of the United States population (2017-2020), increasing from 30.5% in 2000 [

40]. Disparities in obesity are noticeable between ethnic groups. In the United States, there was no association between a lower prevalence of obesity in African American women with increased educational and income levels where in contrast, non-Hispanic ‘white’ women showed a generally negatively correlated trend between education and income [

39]. In addition to being part of a minority population, an inverse relationship has been found between obesity and household income, with supporting research that minority ethnic groups are more likely to experience multidimensional poverty than their ‘white’ counterparts [

39,

40]. Therefore, obesity is being revealed as a disease resulting from the intersection of ethnicity, socioeconomic status, accessibility to resources, and structural environment.

Worldwide, some mothers experience the dual burden of being 'stunted-obese', where they were raised in a state of under-nutrition, which led to growth stunting at first, but later experienced a rapid shift to overnutrition and obesity. Although it is assumed that better living conditions increase health outcomes and decrease labor difficulty, the overnutrition of these stunted mothers increases the fetus size and, therefore, fetopelvic disproportion [

41]. General improvement in living conditions can increase access to nutrition available for a growing fetus, which can grow larger than the mother's birth canal and on a population level, it is possible there could be a general increase in obstructed labor due to access to calories [

42]. Typically, obese mothers give birth to larger babies, and metabolic complications from obesity can contribute to delivery complications [

22,

43]. Notably, shorter and obese women are at an increased risk for gestational diabetes, which can lead to macrosomia in fetuses, leading to a tighter fit [

44]. There is also evidence that improved living conditions worldwide has increased height, and for every 1 mm increase in height per year, the CS rate is predicted to grow by more than 10% because the fetus is relatively bigger to the mother, despite the mother’s height increase [

45]. The stunted-obese phenomenon has been shown in populations like immigrants in the United States and under-resourced communities but could suggest that there may be regions in the United States with American-born citizens that are disproportionately affected by this stunted-obese phenomenon, highlighting disparities in communities from childhood [

42,

46]. It would not be a surprise to find that the stunted-obese phenomenon disproportionately affects ethnic communities, as more African Americans live in food deserts, which have a correlation with increased obesity [

48]. The intersection of ethnicity, poverty, and health outcomes profoundly impacts African American, Native American, and Latino communities. Socioeconomic disadvantages contribute to higher incidences of obesity, gestational diabetes, and other conditions that complicate childbirth and increase maternal morbidity [

48].This may further play a role in the wide maternal health gap between minority women and ‘white’ women.

Genetics, Culture, Racism and Pelvic Shape

Genetics are thought to impact fetopelvic disproportion due to heritability rates in factors that influence the size of the mother's pelvis and the fetus. A twin study evaluating genetic and environmental influences on pelvic morphology demonstrated heritability rates ranging from 0.5-0.8 in 6 of 8 pelvic measurements [

4]. A 2015 study found that women with large-headed neonates tend to have wider pelvises and larger heads themselves [

49]. In response to preventing major fetopelvic disproportion, the pelvises of women with large-headed neonates accommodate to allow for easier birth passage, showing considerable covariation in pelvis size [

49]. The correlation between head circumference and stature was shown to have regression calculations of r=0.45 in females and a stronger correlation of r=0.49 in males [

49]. Females with a large head had a shorter sacrum that projected outward from the birth canal and a pelvic inlet more circular as opposed to an oval pelvic inlet on average for smaller heads [

49]. Historically, the rounder pelvic inlet is associated with the "ideal" shape for neonate accommodation in the pelvis during birth [

50]. Although this study shows evidence for lessening the difficulty of delivery of a large-headed neonate, the selection pressure to make the pelvis more accommodating for birth in the general population has, on average, not shown to be present. Infants with large head circumferences are delivered by unplanned Cesarean delivery at about double the frequency than infants with a normal-range head circumference, irrespective of their birth weight [

51]. The increased risk for instrumental delivery has implications for more fetal complications than high birth weight infants, where birth weight is influenced by environmental factors such as the mother's diet [

52].

However, it is now clear that several epigenetic factors, such as nutrition and related socio-economic aspects, play a huge role in this complex topic, as discussed below. Importantly, another item that is often neglected in such evolutionary discussions on birth obstruction concerns cultural and political factors, including cultural racist and sexist narratives more prevalent in certain societies. For instance, data in the US show the highest overall rates of unplanned cesarean delivery are in African-American women, followed by Asian women than vaginal delivery [

53]. Additionally, low risk African-American and Asian mothers had a higher CS rate than ‘white’ mothers, despite being good candidates for vaginal delivery [

54,

55]. Globally, there are significant differences in the CS rate within different countries, some of them having much higher rates that neighbor countries. The global average CS rate increased by 19% between 1990 and 2018, with the largest increase occurring between 2000-2010 [

9]. In the period between 1990 and 2018, three countries showed greater than 50% increase in CS rate: Turkey, Andorra and Egypt and the lowest rate of CS in Africa [

9]. When divided into categories of country “development”, the least “developed” countries such as those in Sub-Saharan Africa had only an increase by 8.6% in CS in the same 1990 – 2018 timeframe than the average of 19% worldwide, showing great disparity globally [

9]. If the mother has access to cesarean delivery, the reasons for having a CS vary. Personal concerns include fear of vaginal childbirth, or self-doubt with the mother’s ability to have a safe vaginal birth [

56]. However, it appears that the rising CS rates are physician and system-based causes [

57]. A study completed in Chile found Cesarean deliveries being practiced more in patients with private healthcare who were required to have an obstetrician, as opposed to doctors or midwives in the public and academic hospitals [

58]. Cesarean sections come with several risks, particularly in in low- and middle-income countries where mortality and morbidity from CS are estimated to be disproportionately high, and also generally increase the likelihood of the born babies to develop mucosal auto-immune diseases like celiac disease and ulcerative colitis, and even type 1 diabetes and asthma [

59,

60,

61,

62]. CS without medical indication must be minimized as there are serious medical complications, like risk of uterine rupture and abnormal placentation [

63]. CS rates are predicted to increase, and the sequelae like morbidity and mortality of the fetus and mothers of these deliveries are to follow [

9].

Some experts argue the use of midwives and obstetricians since the mid-20th century is a prime example of gene-culture coevolution. In this case, the selective pressure for a wider birth canal and eventually easier childbirth would have been greater without modern obstetrics as the rate of fetopelvic disproportion increased by up to 10-20% since the widespread use of CS [

64]. Although this amount is negligible in clinical care, the short amount of time over which this change occurred renders it remarkable [

64].

Concerning the topic of racism and sexism, historically several medical practitioners have subscribed to the idea that there are different human ‘races’ biologically. In 1886, Turner published an at-the-time distinguished paper comparing pelvic measurements from several human populations to investigate ethnic differences and concluded that pelvic shape does vary across ‘human groups’ [

65]. Turner noted that Europeans mostly had a transversely oval canal whereas other populations assumed a rounder pelvis. Because the rounder pelvises more closely resembled that of apes and at the time, the belief that there was racial superiority of white Europeans over other populations was common, the rounder pelvis was seen was a ‘less departure from the usual mammalian form (Europeans)’ [

65]. It was concluded that pelvic variation was an ‘evolutionary trend’ because the rounder pelvis shape indicated an ‘arrest in evolution from the ape form, the true anthropoid, to the perfect human form which is characteristically flat’ [

65]. We now know this notion is incredibly flawed. There is no specific pelvic shape that definitively designates any particular ‘race’, although some pelvic shapes are more common in some ethnic groups over others.

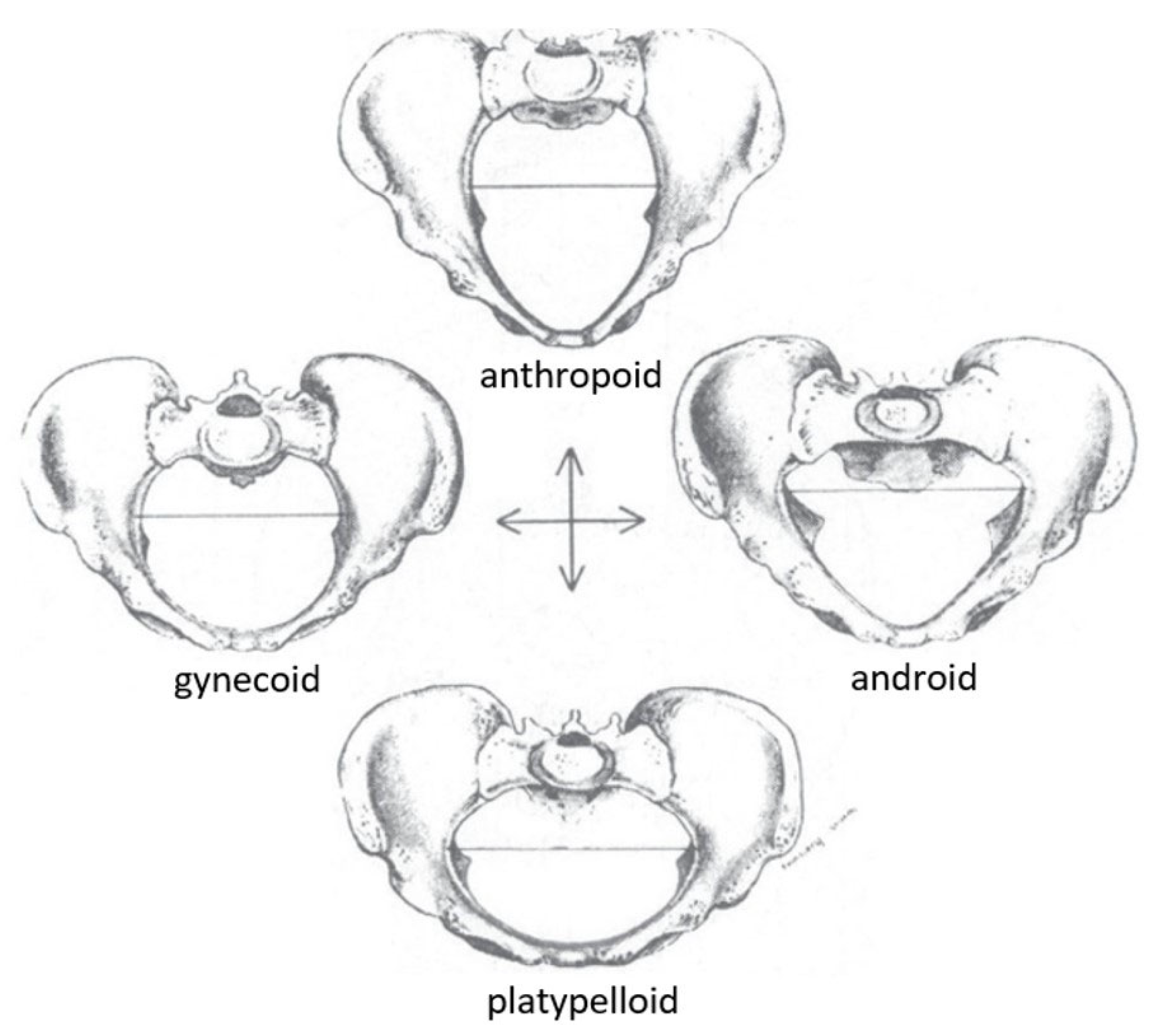

Still, this categorization can be unhelpful or harmful in modern day in the early definitions of this categorization. There are four categories of pelvis shape suggested by Caldwell & Moloy in the 1930s, and their model is the gold standard for obstetrical education today (

Figure 4) [

9,

66]. The first is anthropoid, a long and narrow oval-shaped pelvic inlet. The second is platypelloid, characterized as a short and wide oval-shaped inlet. The third is gynecoid, a circle-shaped inlet flattened in the antero-posterior direction, and fourthly, an android-shaped pelvis with a heart-shaped inlet. In clinical practice, the gynecoid shape is favorable for birth due to its rounded shape. The gynecoid pelvis was considered the 'normal female pelvis', whereas the android pelvis resembled the male pelvis. However, it was recognized that there are mixed characteristics between these four classic types, known as borderline or mixed pelvis types of the four 'pure' or 'parent' forms [

66]. The frequency of pelvic types in Caldwell & Moloy’s study are as follows. The gynaecoid pelvis shape was most common at around 42% of their sample. Anthropoid pelvis shapes were more common in African American women at 40.4% compared to 23.5% of European women and android pelvis shapes were prevalent in about 32.5% of European women and 15.7% of African American women [

15].

The gynecoid pelvis is used to explain how humans evolved differently than apes, and helps distinguish how and why the human birthing process is different from that of other primates. The explanation goes something like this - because human pelvis shape required a more compact pelvic girdle so that humans could be bipedal, the fetopelvic ratio is smaller in humans compared to most apes. Humans, therefore, experience more difficulty in labor and adopt a twisted birth canal so the fetus’s head will pass through with as much ease as possible. The canal starts with a transversely oval inlet and changes into an antero-posteriorly oriented outlet, therefore requiring the fetus head to rotate during labor and emerge facing backward or in the anterior-occiput position. In primate species, the pelvic opening is usually large enough for the fetus to pass through without requiring any rotations, and consequently the fetus is delivered facing forwards in the occiput posterior position [

16]. Because the fetus is delivered facing forward in other primates, the mother can help extract the baby from the vagina by pulling it forwards towards her, but humans cannot. Human mothers trying to extract their own babies certainly would risk damaging the child’s neck and spinal cord as the mother pulls the baby’s head backward. This explains why humans require obstetricians and midwives to assist with labor. The gynecoid pelvis and its associated mechanism of labor differs significantly compared to the anthropoid pelvis and its associated mechanism of labor. The anthropoid pelvis requires a different set of rotations and is more often associated with a forward facing birth [

67]. Because the gynecoid shape is used to describe how human labor came to be and is accepted as the model for womens’ anatomy, it is unwittingly implying that the anthropoid pelvis and the mechanism of labor that accompanies it are ‘less typically human’, which is enormously racist [

15]. The parallel between the words “anthropoid” and “animal” was not incidental; it instead reflected the intentions to debase African-American individuals as anatomically deficient for the vital human act of giving birth [

68].

Previously, the nineteenth and twentieth centuries characterized pelvis shape heavily around ethnicity. The European ‘race’ was viewed as more evolved due to the more difficulty in birthing compared to non-Europeans, quoted as "primitive people" by Engelmann in 1883 [

69]. Physicians and anthropologists took the opportunity to create theories around the different pelvis shapes and how they impacted the ease of birth - often putting a harmful perspective on the evolution of people in general, as mentioned earlier [

6]. Race and religious affiliation seemed to govern the difficulty of the birthing process and, ultimately, evolution itself [

6]. The gynecoid pelvis was the most observed in individuals with European genetic ancestry and was taught as the 'norm'.

This topic relates directly to the practice of determining pelvis shape, which was a method often used clinically to determine potential complications during birthing in the past 70 years. Clinical pelvimetry was used for evaluating pelvis morphology to assess the best delivery routes for complicated births such as those in breech positions or arrested labor [

14]. Pelvimetry could be done radiographically or manually, with manual being invasive and, if done incorrectly, unhelpful to the mother and fetus' outcome [

14]. In obstetrics, Yeomans nicely stated, "pelvic anatomy is to the obstetrician what abdominal anatomy is to the general surgeon—or should be" [

14]. Yeomans does suggest utility in classifying pelvis shape in deciding whether to continue with a CS or instrumental delivery as the shape of the birth canal affects several aspects of labor including fetal position and rotations in the canal, presentation at birth, and likelihood of complications [

15]. More recently, MRI pelvimetry measurements were used as predictive factors for emergent CS delivery in obstructed labor. Today, the sacral outlet diameter distance is used in conjunction with clinical assessment when selecting a safe method of delivery as it is seen as a more accurate depiction of fetopelvic proportionality [

70].

Consequently, there is now a gap in education on the proper mechanisms and progression of labor in other pelvis types. ‘White’ women are the basis of 'normal' gynecoid pelvis shape and obstetrics; therefore, education is largely shaped around this [

71]. However, almost half of African-American women have an anthropoid pelvis shape and have more surgical interventions, possibly contributing to morbidity and mortality [

13,

71]. Latino and Native American women are also among women with a higher prevalence of anthropoid and platypelloid pelvis shapes, which plays a role in their higher rates of Cesarean sections [

72].Anthropoid pelvis shapes lead to generally uncomplicated labor; however, the rotations the fetus experiences differ from what is taught based on the gynecoid pelvis. There is proof that labor occurs differently between gynaecoid and android pelvis shapes, but the prevalence in one group does not infer that one is normal and the other is not. Lack of acknowledgment leads to a lack of education, increasing the rate at which surgical procedures are to be used and increasing the rate of poorly performed interventions [

13]. Forceps are often gently applied when birth needs to progress and the gynaecoid and anthropoid pelvis shapes require a different forceps approach. An attempt to rotate the fetus against the main canal diameter could lead to injury of the mother and baby and even stillbirth [

15]. Surgical interventions come with risks, including sepsis, hemorrhages, and thrombosis, the top causes of mortality and morbidity [

73]. African-American women have the highest rate of Cesarean section. One possible reason for this could be African American women have a higher prevalence of hypertensive disorders and preterm gestation, which are strongly associated with elective primary Cesareans [

74]. It is also not ruled out that poor provider-patient interactions or a mistaken belief about a patient by a provider may contribute to some African American women undergoing C-sections for reasons such as a misunderstanding of the patient’s pain threshold [

74].

Another possible reason for this disparity could be the use of the vaginal birth after Cesarean delivery calculator, which is the calculation used to make a prediction of how successful a woman with a previous CS will be to deliver vaginally. VBAC, or vaginal birth after C-section, is associated with decreased maternal morbidity, avoidance of surgery and surgical complications, lower risk of postpartum hemorrhage and infection, and less risk for complications in future pregnancies [

75]. Likelihood for being selected as a candidate of VBAC, however, is less if you are African-American or Hispanic as one point is deducted from your overall calculated score for being one of these two ethnicities. The VBAC calculator was made to help providers individualize risk assessment for VBAC by accounting for personal risk factors, but unfortunately has exacerbated ethnic disparities in maternal care and maternal outcomes. Only recently has a new VBAC calculator model that excludes race been proposed and used in practice, and unfortunately is not widely adopted [

76].

The disparity Native American pregnant women living on reservations face is unique, but also echoes the theme African-American women face with poor physician-patient interactions and cultural misunderstandings. Early and continuous prenatal care is essential for proper education, discussing concerns, and identifying high risk patients and implementing proper interventions to avoid negative birth outcomes. Unfortunately, Native American women seeking care through the Indian Health Service only begin their prenatal care in the first trimester 66.5% of the time, compared to other ethnicities that begin prenatal care in the first trimester 81.3% of the time [

77]. Specifically, education of cessation of substance use during pregnancy is helpful in reducing the rate of preterm delivery, infant mortality, and low birth weight, which are alarming statistics in Native American women. Native Americans have the highest rates of alcohol, marijuana, and drug use disorders compared to all other ethnic groups, necessitating the need for early pregnancy education and intervention of drug use during pregnancy [

78]. Living on the reservation offers a very low quality of life with high rates of poverty, sexual or physical abuse, and depression and substance abuse. A lot of Native American pregnant women in these environments receive little to no support from their partner or may be embarrassed from an unplanned pregnancy. In order to improve care, there is a need to understand why Native American women are significantly more non-adherent to prenatal healthcare. Some proposed ideas include cultural barriers, lack of proper healthcare systems on reservations, and social determinants. Many Native American women express distrust with physicians, especially white physicians, and “Western medicine”. In addition, it is common for patients in the Indian Health service to see a different physician at every prenatal appointment and wait 2 hours for their 15 minute prenatal appointment. Some even propose that a majority of care provided by natural helpers in the Native American community should take a stronger, official role in providing care in collaboration with clinicians [

79]. Many minority groups experiencing similar struggles with healthcare may suggest that it is not just pelvic shape that plays a strong role, but rather the interaction of various factors that contributes to maternal morbidity and mortality. Despite Native Americans having the widest pelvises, this group faces extremely poor maternal health outcomes [

80]. This further suggests that a more encompassing Extended Evolutionary Synthesis view is needed to explain maternal morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledging these differences is normalizing the variation between pelvis shapes and understanding how to address it in practice. Even in areas with ‘white’ women as a minority, donated books teaching the anatomy and obstetrics primarily of European women from universities in majorly African-American areas are given. This ultimately will influence how healthcare providers in that area care for the non-‘white’ population they serve [

13]. Geographical proximity governs genetic and phenotypic resemblance with pelvis shape, and it is suggested that pelvis shape and size variation is less common than skin color variance geographically [

13]. As modern society includes globalization and immigration, the teaching of one shape of the pelvis puts future mothers at a disadvantage in their pregnancy journey.

New improvements in technology to measure and assess pelvic shape as a factor in a safe delivery bring about new classifications. Humans immigrated from Africa around 60,000 years ago, which is not a significant amount of time to evolutionize into vastly different pelvic shapes. As stated earlier, the anthropoid pelvis shape is far more similar to other human pelvises than that of any ape [

15]. More recent studies do not support the existence of four distinct pelvic types as made by Caldwell & Moloy. In fact, literature is now saying pelvic anatomic variation within populations is more due to nutrition and climate than ethnicity [

15]. A study in Australia used CT scans to measure 64 female pelvises and found no specific groupings, but instead a spectrum of many different shapes [

81]. It is very possible the Caldwell & Moloy classification is incorrect as it was only made using the data of a few thousand pelvises, and only in one specific region, the United States. The recent evidence that pelvic shape depends more on nutrition and climate than other factors may have skewed the data Caldwell & Moloy were pulling from to make their classification. Although limited scientific literature is published about this topic, there is notion that assessing pelvic type during the prenatal period is not useful in predicting cephalo-pelvic disproportion as the external pelvic shape may not correspond to internal features of the pelvic like pubic arch, sacral prominence, and ischial spinous distance, which all play a stronger role in various mechanical issues associated with obstructed labor [

82,

83]. This has thankfully encouraged some midwives in the US to abandon the Caldwell & Moloy classification system and adopt anti-racist methods of pelvic anatomy analysis. These midwives teach their students that assessments are individualized and not tied to socially constructed race categories as there is quite a broad and normal range of variation in pelvic shapes [

82].