1. Introduction

Thorium is a weak radioactive element, with abundance similar to that of lead [

1,

2,

3]. From this point of view, thorium should not concern environmental protection researchers [

4]. However, what must be considered is that thorium is a heavy metal, so with potential toxicity similar to other heavy metals [

5,

6]. A special feature is the presence of thorium in various surface waters [

6,

7], but also in soil [

8] or even accumulated in various plants [

8]. It is expected that thorium appears in mining areas in aqueous effluents [

9], but also naturally in streams or rivers that pass-through areas where thorium is accumulated [

9,

10]. At a common pH of surface waters [

11] thorium precipitates and is found in sediments, but under acidic water conditions thorium is found in the ionic form Th

4⁺, or the hydroxyl forms Th(OH)

3⁺, Th(OH)

22⁺, Th(OH)

3⁺ [

12,

13].

Thus, the recovery of thorium from aqueous systems containing thorium or other heavy metals becomes extremely important [

14]. Classical separation processes (precipitation, sedimentation, flocculation, ion exchange) can be taken into account, but modern extractive, adsorptive and membrane processes can be approached [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

Table 1.

The main techniques and methods of thorium recovery.

Table 1.

The main techniques and methods of thorium recovery.

| Techniques or methods of thorium recovery |

Refs. |

| Polymer inclusion membrane |

17 |

| Ionic Liquid Cyphos IL 104. |

18 |

| α–Aminophosphonates, –Phosphinates, and –Phosphine Oxides as Extraction and Precipitation Agents |

19 |

| Polymeric Materials |

20 |

| Highly efficient adsorbent |

21 |

| Binary Extractant Based on 1,5–bis [2–(hydroxyethoxyphosphoryl) –4–ethylphenoxy] –3–oxapentane and Methyl Trioctylammonium Nitrate |

22 |

| 2–nitroso–1–naphthol impregnated MCI GEL CHP20P resin |

23 |

| UiO–66–OH zirconium metal–organic framework |

24 |

| Polyurea–Crosslinked Alginate Aerogels |

25 |

| α–Aminophosphonate Extractant |

26 |

| 8–Hydroxyquinoline Immobilized Bentonite |

27 |

| New Polymer with Imprinted Ions |

28 |

| Zeolite Adsorption |

29 |

| Nanofiltration membrane |

30 |

| Ionic Liquids |

31 |

| Nanofiltration Extraction |

33 |

From a practical point of view, to obtain thorium-free drinking water, the use of emulsion membranes is excluded due to the need for reagents and solvents which would impurity the water and, at the same time, their recovery by breaking the emulsions raises problems difficult to solve in the isolated areas that we have in view [

34,

35]. If an approach based on a membrane technique is desired, then the one that uses hollow fiber membranes is viable [

36,

37]. The beginning of an application with hollow fiber membranes occurs, most of the time, as it happens in the present study, with the study of separation with bulk or flat membranes [

38,

39,

40].

The accessible and efficient procedure is nanofiltration, which uses nanoporous composite membranes and achievable pressures (4–8 atm) with usual means [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

In the present work, the separation of thorium in ionic form, from dilute aqueous solutions similar to those possible to be found in isolated places, is addressed, so as to obtain drinking water.

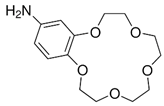

The issue that we propose as a study is the separation of thorium from synthetic solutions using the dead-end filtration technique, with sulfonated poly-ether-ether-sulfonate ketone (sPEEK) membranes containing 4’–Amino–Benzo–15–Crown–5 Ether (ABCE).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Materials

All reagents and organic compounds used in the presented work were of analytical grade.

Th (NO3)4·5H2O, H2SO4 (96%), NaOH pellets, HCl 35% super pure and NH4OH 25% (analytical grade) were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany).

Torin, N–hydroxyl–N,N’–diphenylbenzamidine (HDPBA) and 4’–Amino–Benzo–15–Crown–5 Ether (ABCE) (analytical grade, Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Steinheim, Germany) were used within the study.

The purified water characterized by 18.2 μS/cm conductivity was obtained with a RO Millipore system (MilliQ

® Direct 8 RO Water Purification System, Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) [

16].

(1,4–phenylene ether–ether–ketone) (PEEK) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Steinheim, Germany.

2.2. Procedures and Methods

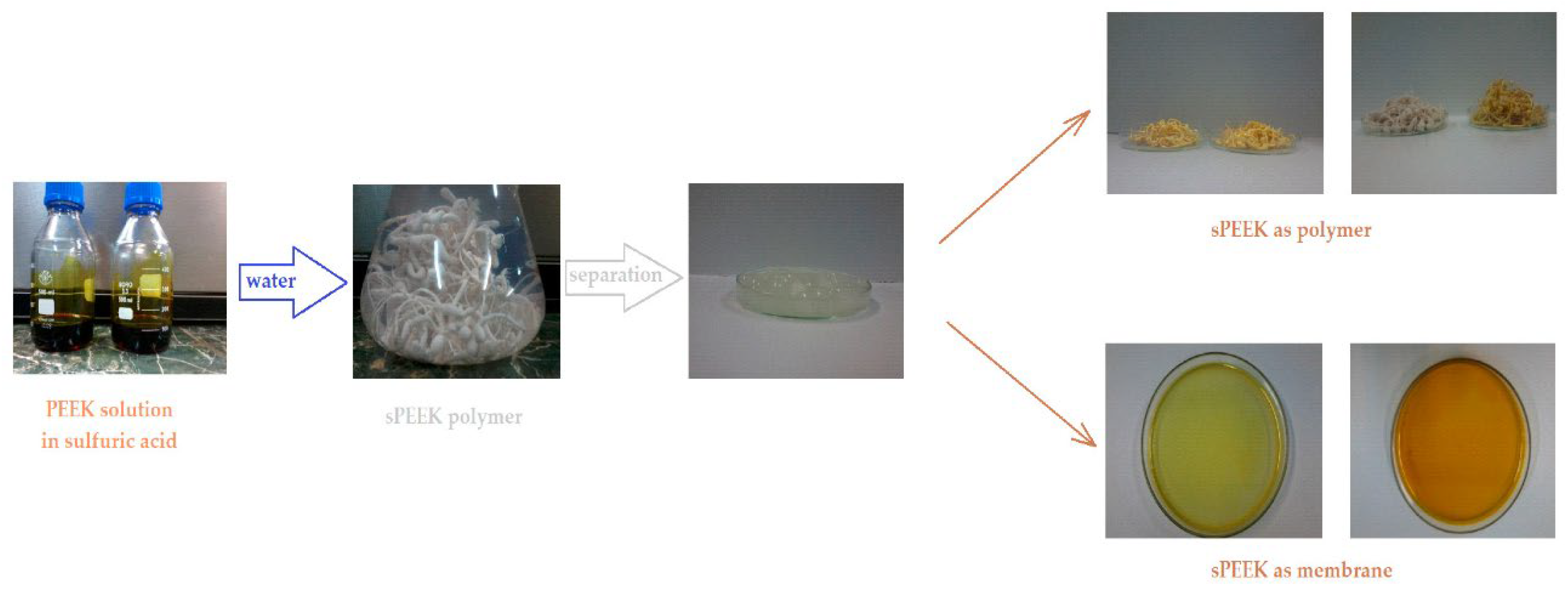

2.2.1. Preparation of sPEEK–M Membranes from PEEK Solution in Sulfuric Acid

The preparation of sPEEK membranes using a solution of PEEK in 96% sulfuric acid was previously reported (

Figure 1) [

45,

46]. In short, the predetermined amount of PEEK is dissolved in 96% sulfuric acid by stirring in an ultrasonic bath, for 48 hours. After dissolution, a solution is obtained in which PEEK has transformed into sPEEK through a chemical reaction at ambient temperature. The sPEEK gel is deposited on a Petri glass support. The film formed on the Petri dish is placed in a vacuum oven, with laminar air flow, at a temperature of 50 °C, for 72 hours. After the drying interval, the sPEEK membrane is cut to the size required for the nanofiltration experiments.

sPEEK–M membranes were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Energy Dispersive X–ray Spectroscopy (EDAX) and thermal analysis (TG and DSC).

The determination of the degree of sulfonation and the ion capacity exchange (i.c.e. = 1.65 mmol/g) were reported [

47,

48,

49].

2.2.2. Preparation of ABCE–sPEEK Composite Membranes

4’–Amino–Benzo–15–Crown–5 Ether–sPEEK composite membranes (ABCE–sPEEK) was obtained by dissolving the crown ether (ABCE) in a concentration of 1.65 mmol/g sPEEK, in the sPEEK solution whose preparation was previously described, after which the steps specified and illustrated in

Figure 1 are followed.

The characteristics of the composite membrane compounds are shown in

Table 2.

Composite membranes (ABCE-sPEEK) were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Energy Dispersive X–ray Spectroscopy (EDAX) and thermal analysis (TG and DSC).

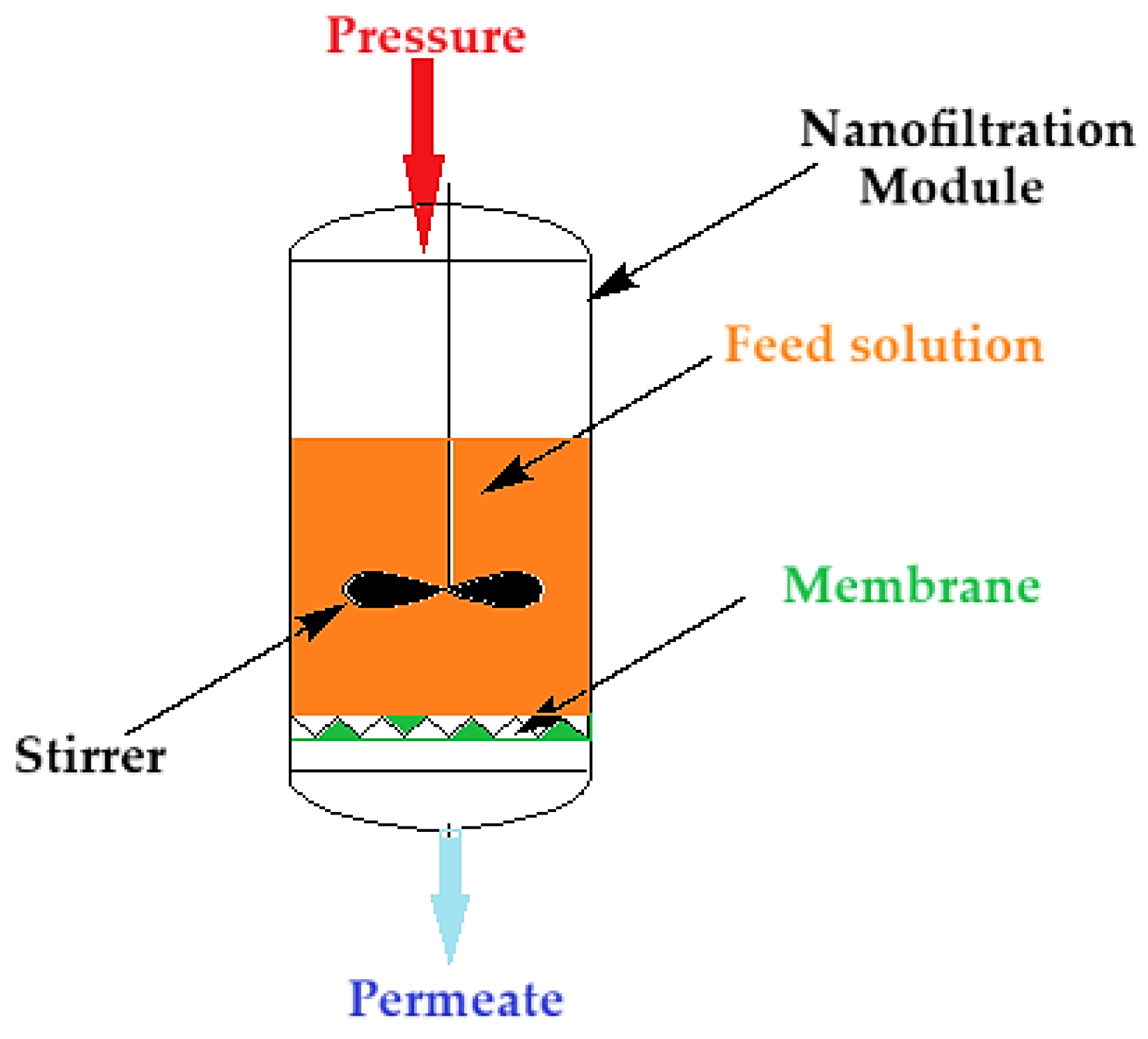

2.2.3. Nanofiltration of Thorium Solution

Nanofiltration of the thorium nitrate solution was carried out (

Figure 2) at a pressure of 5 to 9 atmospheres through the composite membrane (ABCE–sPEEK) and for comparison through the sPEEK membrane. The module of nanofiltration, of dead-end filtration type, is equipped with a propeller stirrer that achieves (performs) a turbulent agitation of the feed solution. The feed solutions have a concentration of 10⁻

4 mol/L and 10⁻

5 mol/L thorium nitrate in ultrapure water also containing nitric acid. The pH variation of these solutions is done with nitric acid solutions of 1 mol/L, 10⁻

1 mol/L, 10⁻

2 mol/L, 10⁻

3 mol/L and 10⁻

4 mol/L.

The result of the nanofiltration was presented in the form of the permeate flux (J) (eq. 1) or of the nanofiltration retention [

50] (R) (eq. 2):

where: J – permeate flux; V – permeate volume; S – surface of the membrane; Δt – operating interval.

where: R – retention (%); C

0 – concentration of feed solution; C

f – final concentration.

The concentration of the thorium ion was determined by the Torin spectrophotometric method. The specific determinations are carried-out coupled extraction separation and spectrophotometric detection at λ = 495 nm. The detection limit of the method is 0.04 µg Th (IV) mL⁻

1, and the RSD (n = 10) is 1.4% [

51]. The obtained results have a total precision of 0.1ppm imposed both by the traceability of the samples taken and by the spectrophotometric methods approached.

2.3. Equipment

For the study of the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive spectrum for the characteristic X–ray (EDAX) analyses, the membrane samples, subjected to the analysis, were visualized with the help of the FESEM–FIB workstation (scanning electron microscope with field emission electron and focused beam of ions) model Auriga (Carl Zeiss SMT, Oberkochen, Germany), by means of the secondary electron/ion detector (SESI) in the sample chamber for the topography/morphology of the surface of the analyzed samples [

52].

The verification of the chemical composition was carried out with the help of the EDS probe produced by Oxford Instruments, UK - energy dispersive spectrometer model X–MaxN with the Aztec acquisition and processing software integrated on the FESEM–FIB Auriga working station [

53].

Thermal analysis (TG-DSC) was performed with a STA 449C Jupiter apparatus, from Netzsch (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany). Each sample was weighed as approximatively 10 mg. The samples were placed in an open alumina crucible and heated up to 900 °C with a 10 K∙min⁻

1 rate, under a flow of 50 mL∙min⁻

1 dried air. As a reference, we used an empty alumina crucible [

54].

The UV-Vis analyses of the solutions were done on a Spectrometer CamSpec M550 (Spectronic CamSpec Ltd., Leeds, UK) [

55].

The UV-Vis studies on the samples composition were validated on dual-beam UV equipment – Varian Cary 50 (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, California, USA) at a resolution of 1 nm, spectral bandwidth 1.5 nm, and 300 nm/s scan rate. The UV-Vis spectra of the samples were recorded for a wavelength from 200 to 800 nm, at room temperature, using 10 mm quartz cells [

56].

The pH of the medium was followed up with a combined selective electrode (HI 4107, Hanna Instruments Ltd., UK) and a multi-parameter system (HI5522, Hanna Instruments Ltd., Leighton Buzzard, UK) [

57].

Other devices used were as follows: ultrasonic bath (Elmasonic S, Elma Schmidbauer GmbH, Singen, Germany), vacuum oven (VIOLA—Shimadzu, Bucharest, Romania) [

58].

3. Results and Discussion

The morphological and structural characterizations of the prepared membranes were carried out by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive X–ray spectroscopy (EDAX) and thermal analysis (TG and DSC), and the performances in the retention process of thorium from acidic aqueous solutions were established by determining the permeate fluxes (J) and thorium retention (R%).

3.1. Characterization of the Prepared Membranes

3.1.1. Morphological Characterization

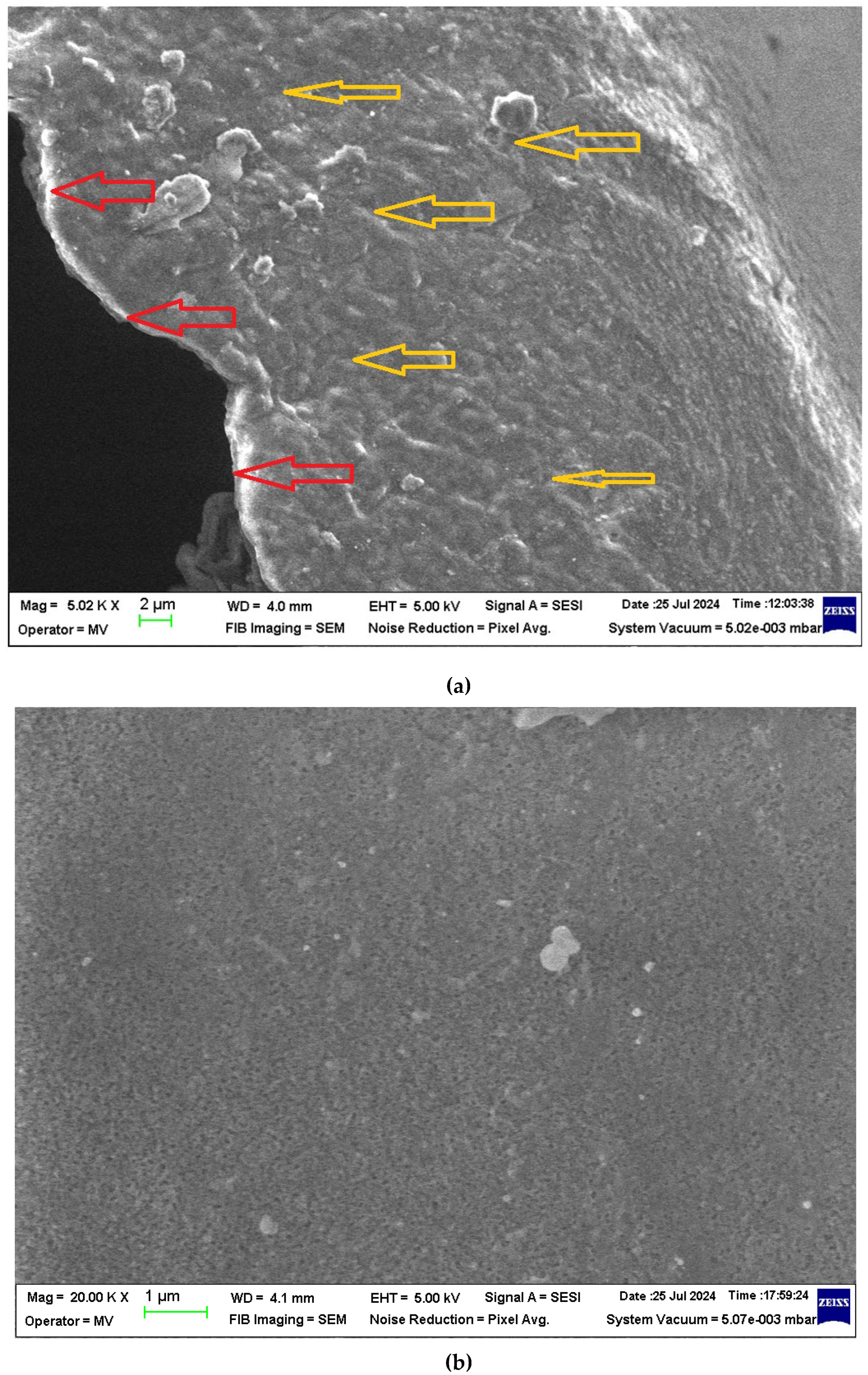

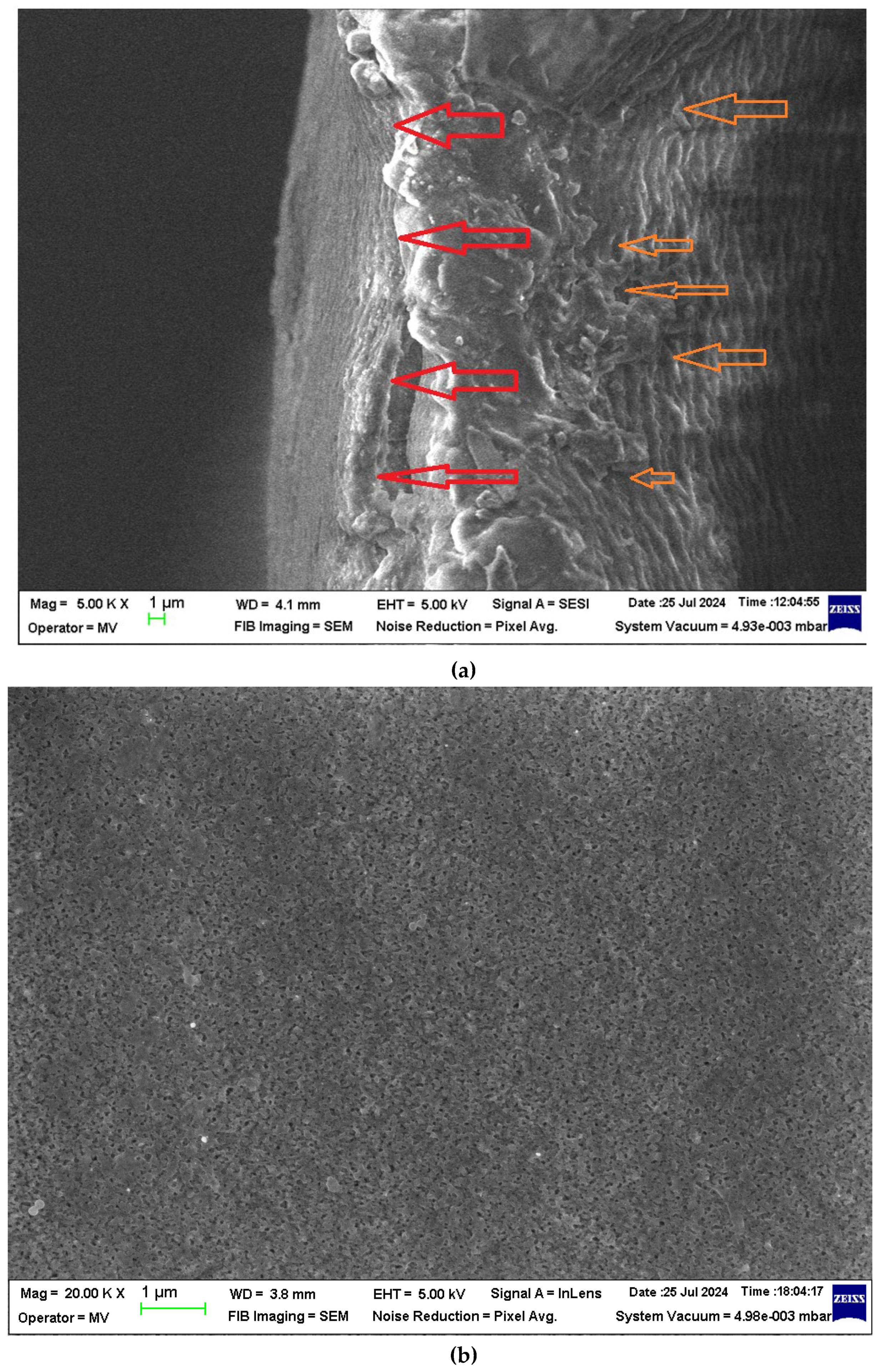

The section morphology of the two membranes – the sPEEK membrane and the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane – was examined in the section and on the bottom surface using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (

Figure 3a,b,

Figure 4a–c). The images were obtained using FESEM–FIB workstation on samples fractured in liquid nitrogen and without metallization.

The section of the sPEEK membrane (

Figure 3a) is a porous structure (orange arrows) in which the selective, more compact upper layer can be observed (red arrow). The bottom surface of the membrane (

Figure 3b) has submicron pores. The section of the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane is compact at selective layer (

Figure 4a, red arrows) and porous (

Figure 4a, orange arrows). The bottom layer reveals the uniform micro-porosity (

Figure 4b,c).

Although they have a different structure, these membranes are likely to be used for nanofiltration of solutions containing ionic thorium, because the materials from which they are made are ion exchangers and/or complexants.

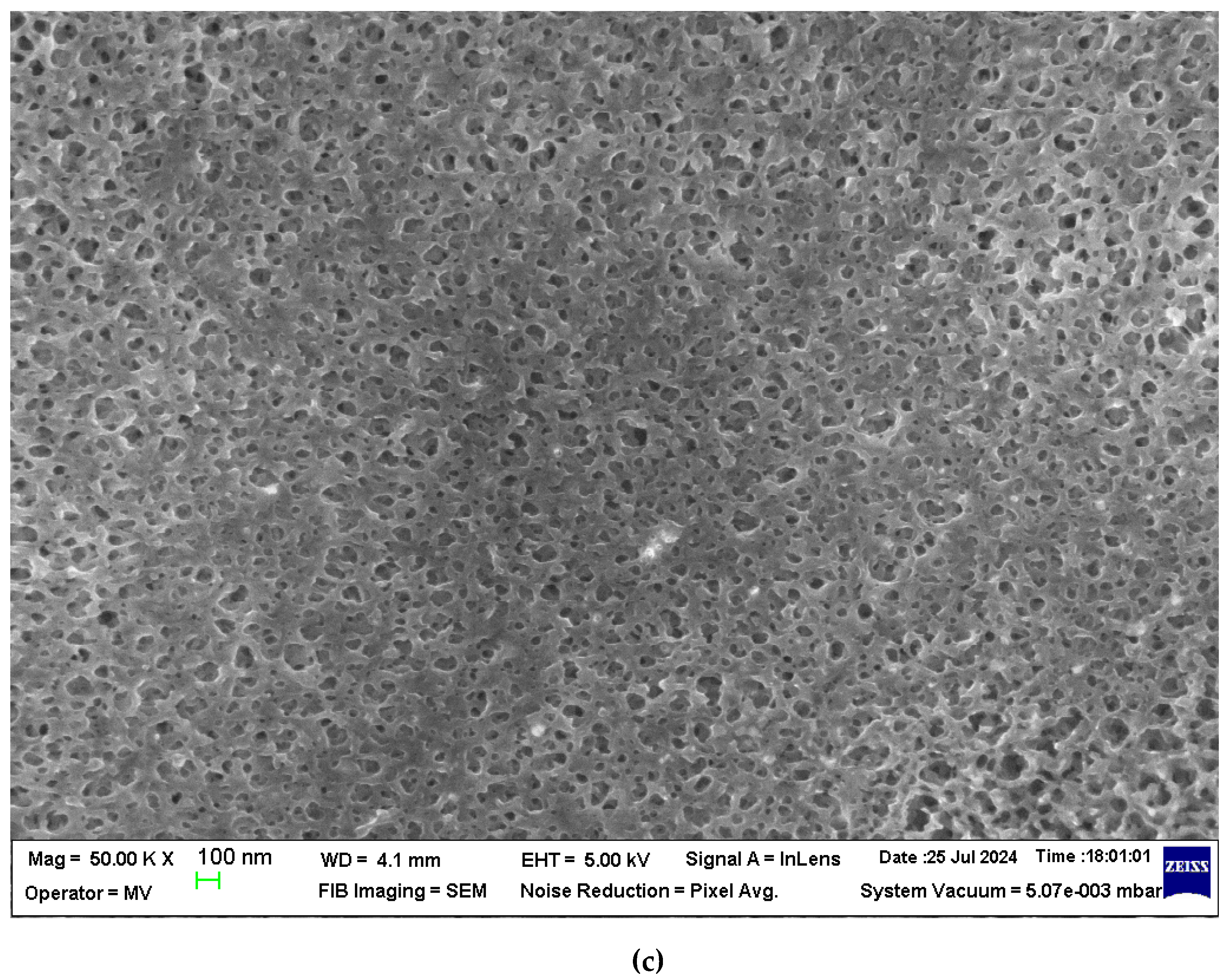

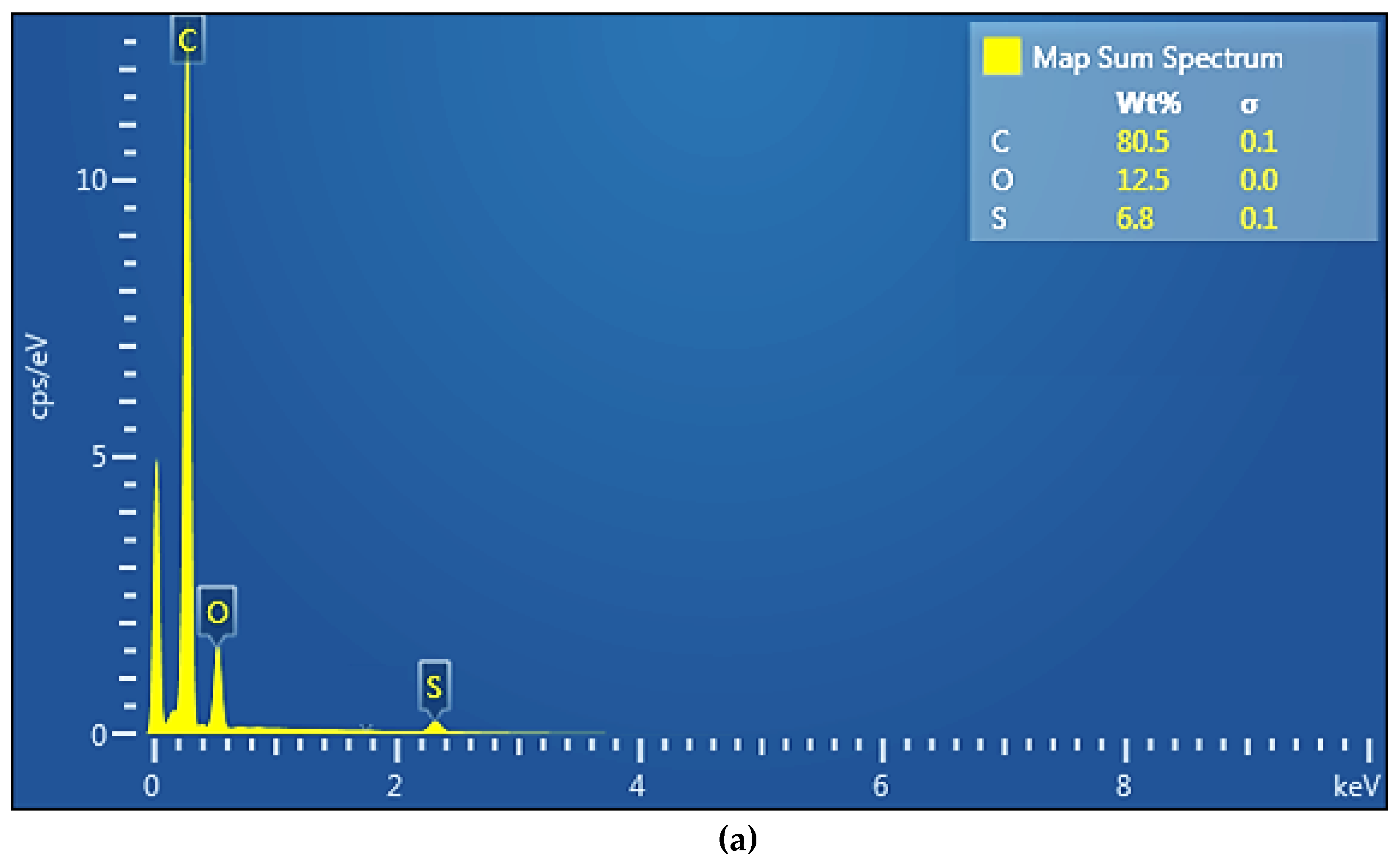

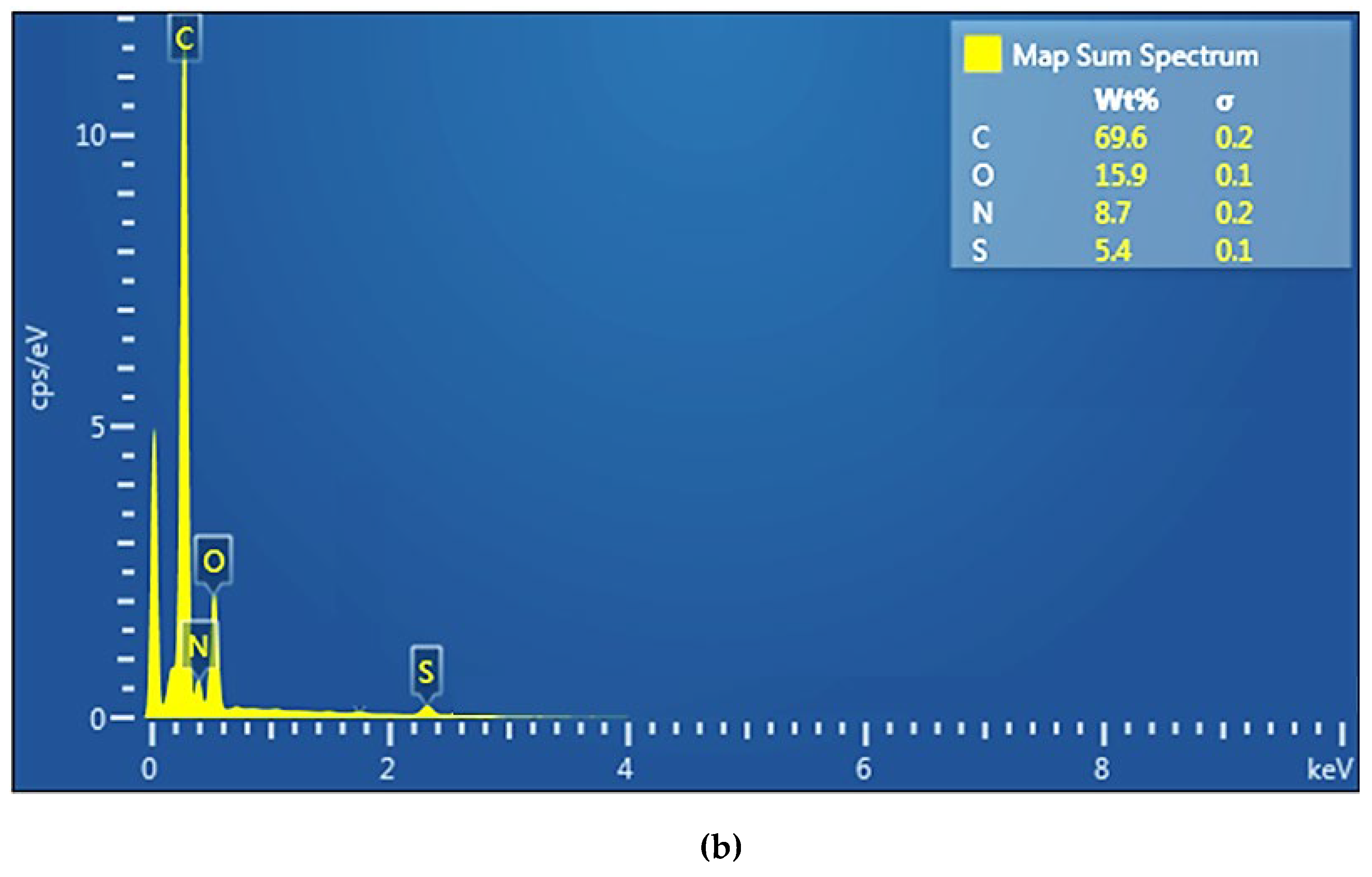

3.1.2. Compositional Analysis

The compositional analysis (EDAX) was performed on the surface of the membranes (

Figure 5a,b).

The EDAX spectrum of the sPEEK membrane (

Figure 5a) highlights the presence of carbon 80.5%, oxygen 12.5% and sulfur 6.8%. The EDAX spectrum of the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane (

Figure 5b) shows the presence of carbon 69.6%, oxygen 15.5%, sulfur 5.4% and nitrogen 8.7%. The analysis shows a decrease in the concentration of carbon and sulfur at the expense of oxygen and nitrogen. The increase in oxygen concentration is a consequence of the 4’–Amino–Benzo–15–Crown–5 Ether (ABCE) ring, and the amino group provides the nitrogen in the EDAX spectrum.

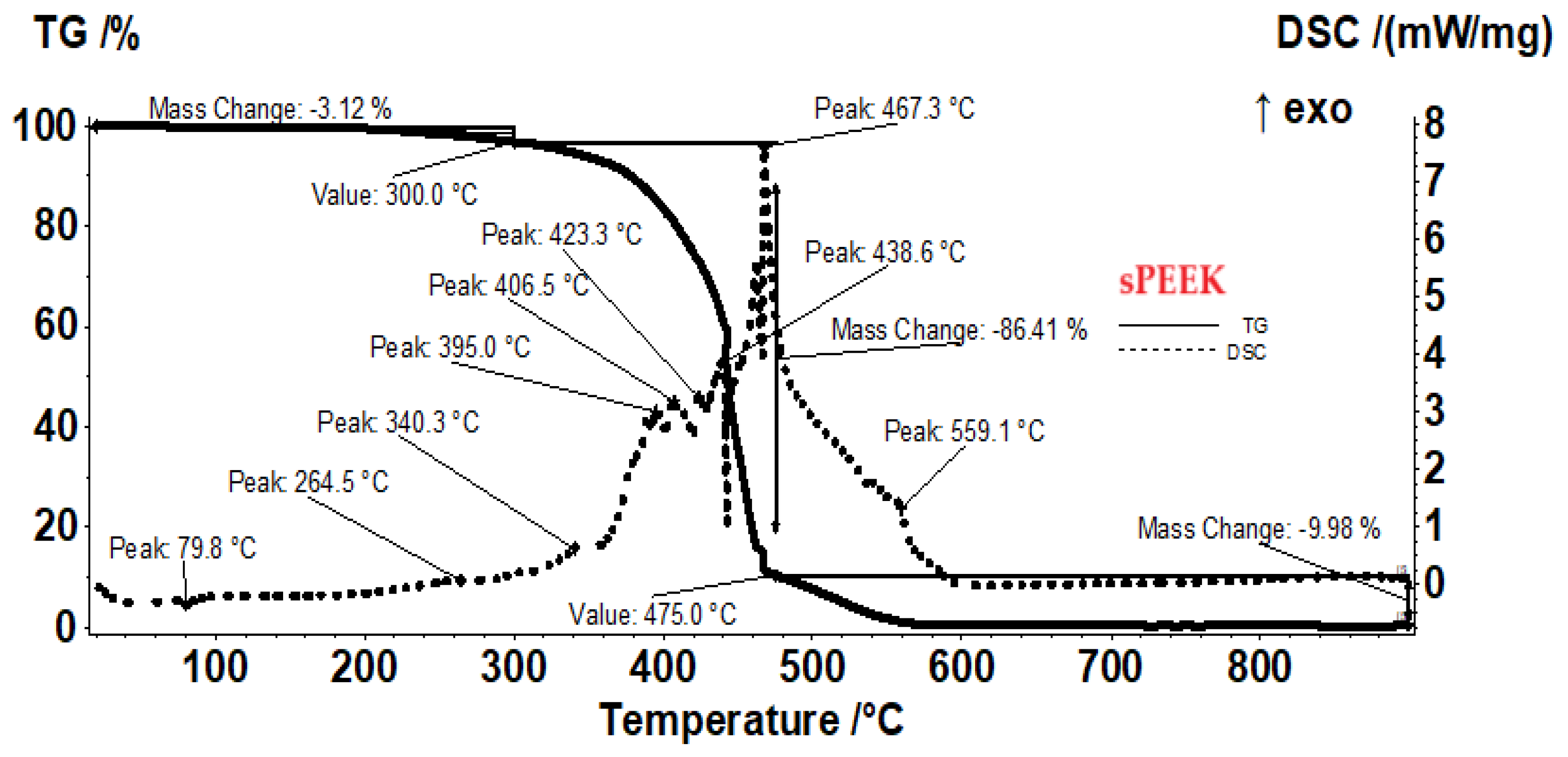

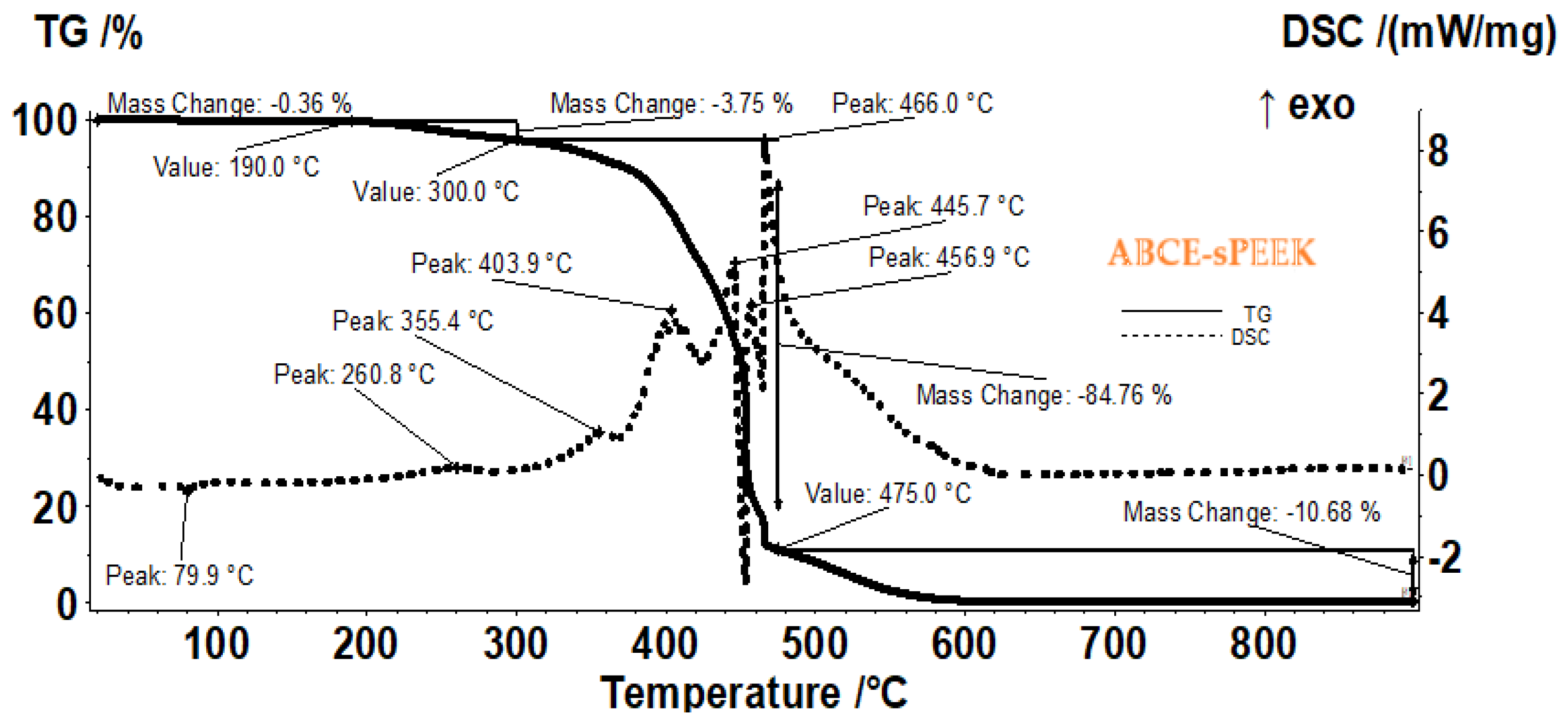

3.1.3. Thermal Analysis

The thermal analysis was performed to indicate the thermal behavior of the membranes from a scientific point of view, but also from a practical point of view (when recycling the membrane polymer through heat treatment).

The sample of the sPEEK membranes (

Figure 6) presents a smaller mass loss than sPEEK in the interval RT−300 °C, only 3.12%, the process being accompanied by a small endothermic peak at 79.8 °C and a small exothermic peak at 264.5 °C. These effects correspond to elimination of residual solvent molecules and beginning of the desulfurization processes. After 300 °C the oxidative degradation becomes evident due to mass loss and associated exothermic effects, indicating the complexity of the sample and degradation reactions. The recorded mass loss between 300–475 °C is of 86.41%. The strong and quick oxidation process towards the end of the interval, starts for ABCE–sPEEK at 440 °C, ~10°C earlier than for sPEEK sample, the exothermic peak being placed at approximatively same temperature, 467.3°C. The residual carbonaceous mass is burned after 475 °C, when a mass loss of 9.98% is recorded and the FTIR of evolved gases identifies CO

2 as the major product.

The sample of the composite membrane (ABCE–sPEEK) (

Figure 7) is stable losing only 0.36% up to 190 °C (residual molecules of water as indicated by FTIR and by the very weak endothermic effect from 79.9 °C). Further, the sample is losing 3.75% of its mass up to 300 °C, the process being accompanied by a weak exothermic peak at 260.8 °C, indicating an oxidation. Between 300–475 °C the sample is losing 84.76% of its mass, in a series of oxidative-degradative processes, accompanied by exothermic peaks at 355.4, 403.9, 445.7, 456.9 and 466.0 °C. The oxidation of the sample becomes highly exothermic and quick after 450 °C. After 475 °C a mass loss of 10.68% is recorded as the residual carbonaceous mass is burned away.

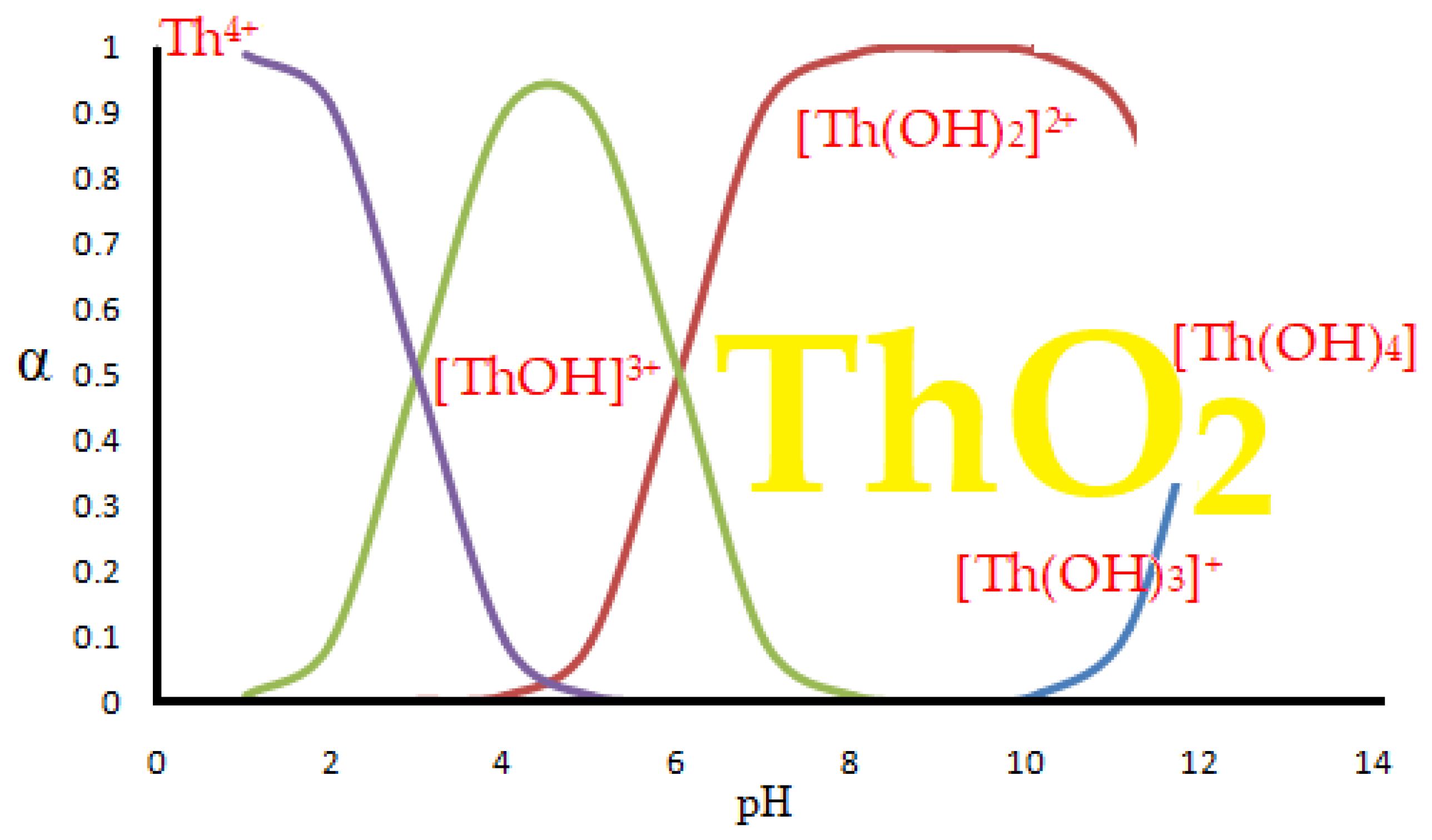

3.2. The Process Performances of the Prepared Membranes

When dissolving thorium nitrate in water, hydroxyl species are formed [

41,

45,

59,

60] shown hypothetically in

Figure 8 [

41,

45].

The degree of formation in solution of various chemical species can be determined exactly if the acidity constants of the chemical species and/or stability constants of the hydroxyl complexes are known [

61]. The existence of chemical species of thorium can be found in Pourbaix diagrams, which take into account both the pH and the electrochemical potential of the aqueous system [

62].

The appearance of thorium dioxide is also related to the pH of the solution [

60,

61], but in this paper we consider the separation of thorium from acidic solutions, pH from 0 to 4, when the predominant chemical species is Th

4⁺.

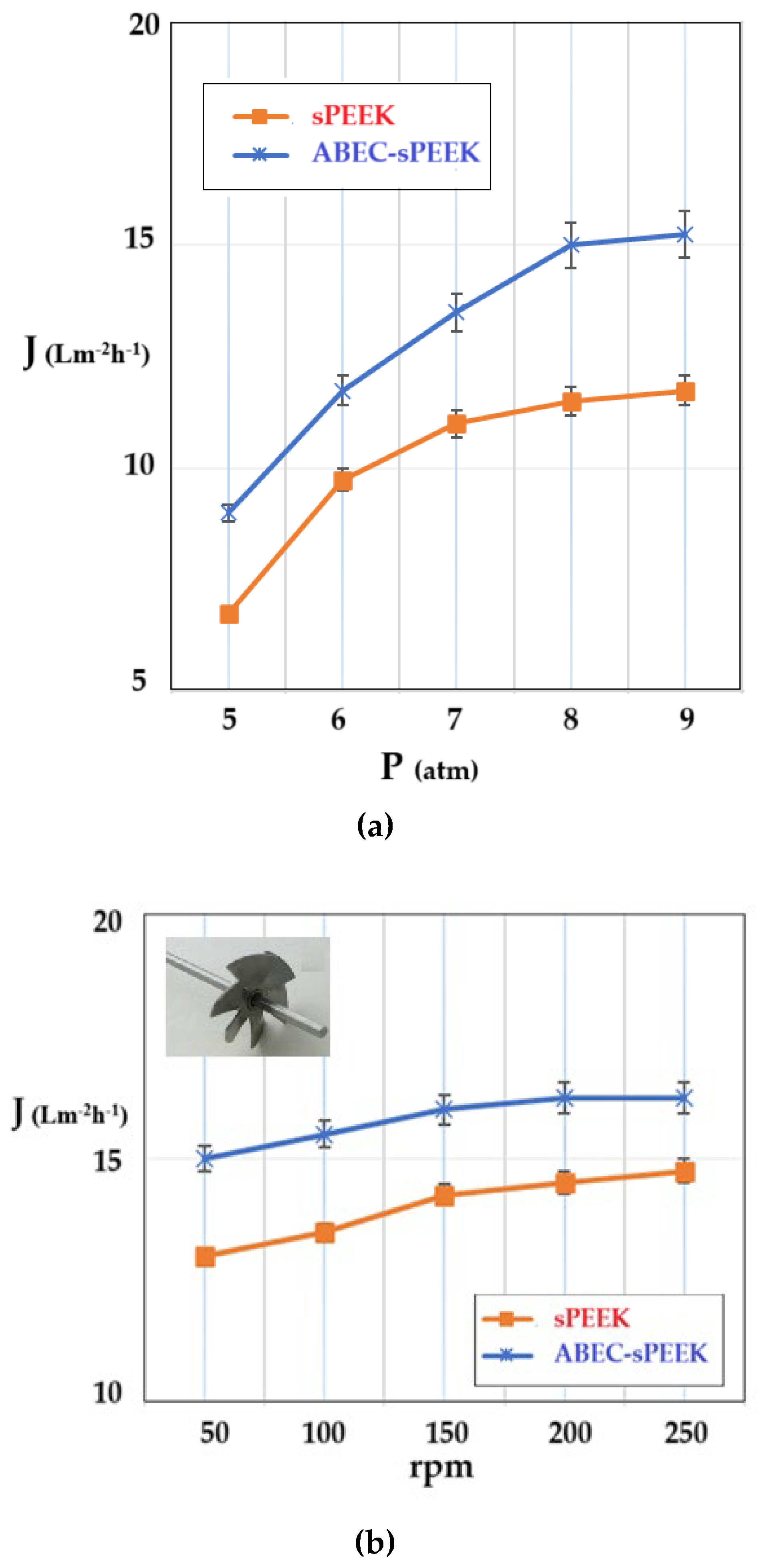

3.2.1. Determination of the Hydrodynamic Performances of the Prepared Membranes

The determination of the hydrodynamic performances of the membranes was carried out using ultrapure water. The variable parameters were the working pressure (

Figure 9a) and the rotational speed of the propeller agitator [

63] (

Figure 9b).

The shape of the flux curves (J) as a function of the working pressure, corresponding to the sPEEK membrane and the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane, is the same. From the obtained results (

Figure 9a), it appears that the working pressure causes an increase in the permeate flux (pure water), in the range of 5–8 atmospheres, after which a plateau is observed. For both membranes, the optimal working pressure is 8 atmospheres. The appearance of the flux plateau (pregnant for the sPEEK membrane) can be explained by the compaction of the membranes at high pressure. This observation is in agreement with the porous structures presented in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. When the pressure increased above the value of 9 atmospheres, the break-up of the membranes was observed.

On the other hand, operating at an operating pressure of 8 atmospheres, increasing the rotation speed (

Figure 9b) causes an increase in the permeate fluxes between 50 rpm and 200 rpm, after which a plateau is observed for both membranes. The appearance of the plateau is determined by the turbulent flow regime that appears at 200 rpm and continues at the following rotation values of the propeller. The speed chosen for the subsequent studies was 200 rpm. The flow regime led to an additional flow contribution of about 20% for the sPEEK membrane and about 15% for the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane.

The permeate fluxes, both depending on the working pressure and the rotational speed of the agitator, are higher for the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane compared to the sPEEK membrane.

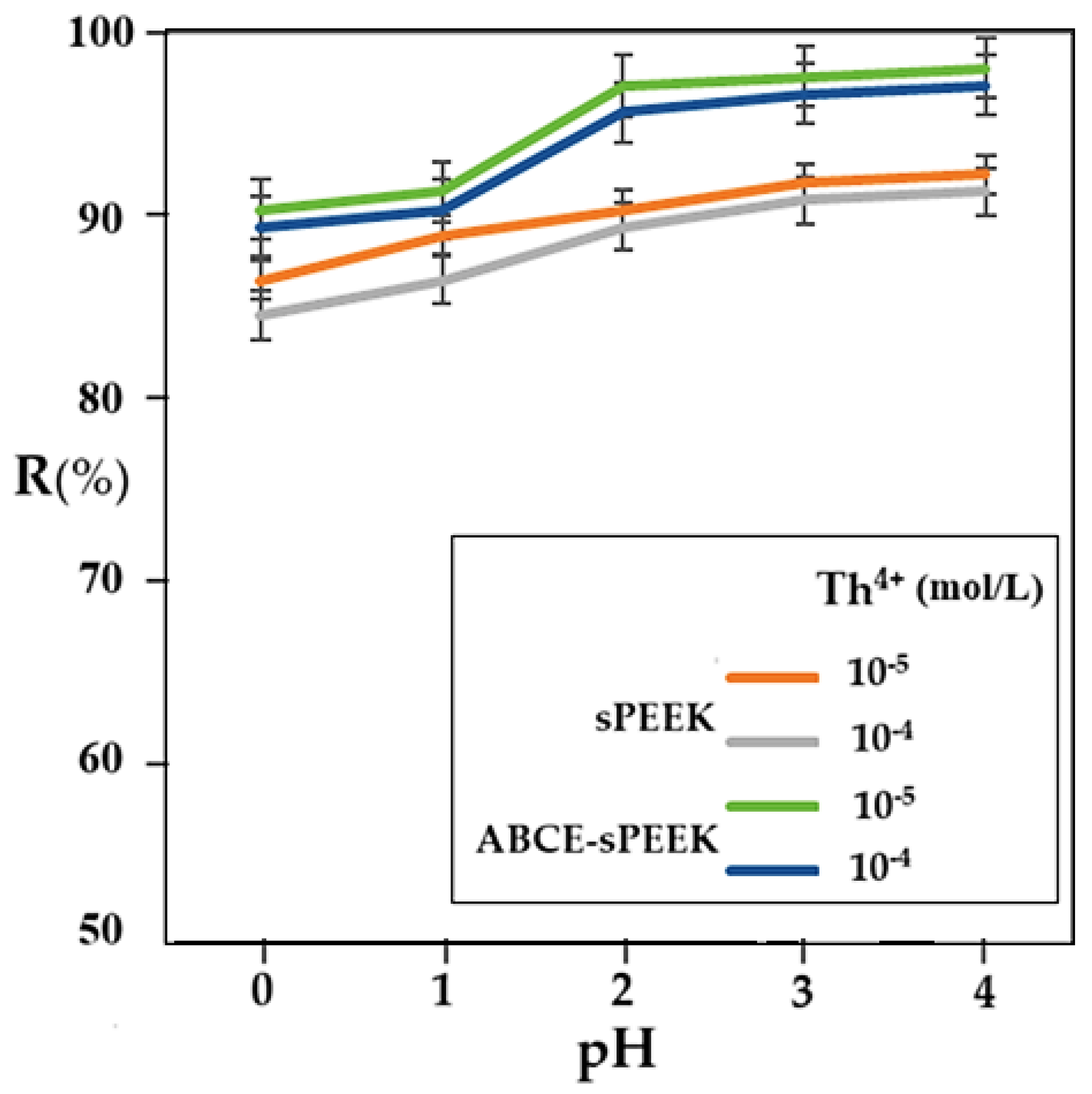

3.2.2. The performance of nanofiltration depending on the pH of the solution and the concentration of the thorium ion

At a working pressure of 8 atmospheres and a rotation speed of the agitator of 200 rpm, the retention variation according to pH was followed for the two membranes, at concentrations of 10⁻

4 mol/L and 10⁻

5 mol/L thorium nitrate in ultrapure water (

Figure 10).

In all cases studied, the retention increases with the increase in pH. In the case of the sPEEK membrane, the retention is between 85% and 90% with a uniform increase over the entire pH range. The retention values for the sPEEK membrane are higher for the 10⁻5 mol/L concentration solution compared to the 10⁻4 mol/L concentration solution.

The thorium retention for the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane varies between 90% and 98%, being higher for the 10⁻

5 mol/L concentration solution than for the 10⁻

4 mol/L concentration solution, over the entire pH range. In the case of the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane, for both thorium concentrations studied, a jump in retention was found at pH 2. This observation is correlated with the acidity constant of sPEEK, which is between 2.0 and 2.2 (

Table 2), but also with the presence of the crown ether in the form of ammonium ion. A plausible explanation would be that the acidic, molecular form of sPEEK (R–SO

3H) passes into the basic, anionic form (R–SO

3⁻) that interacts more strongly with the thorium ion. At the same time, the crown ether specifically complexes the thorium ion, causing an increase in the retention of the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane compared to the sPEEK membrane.

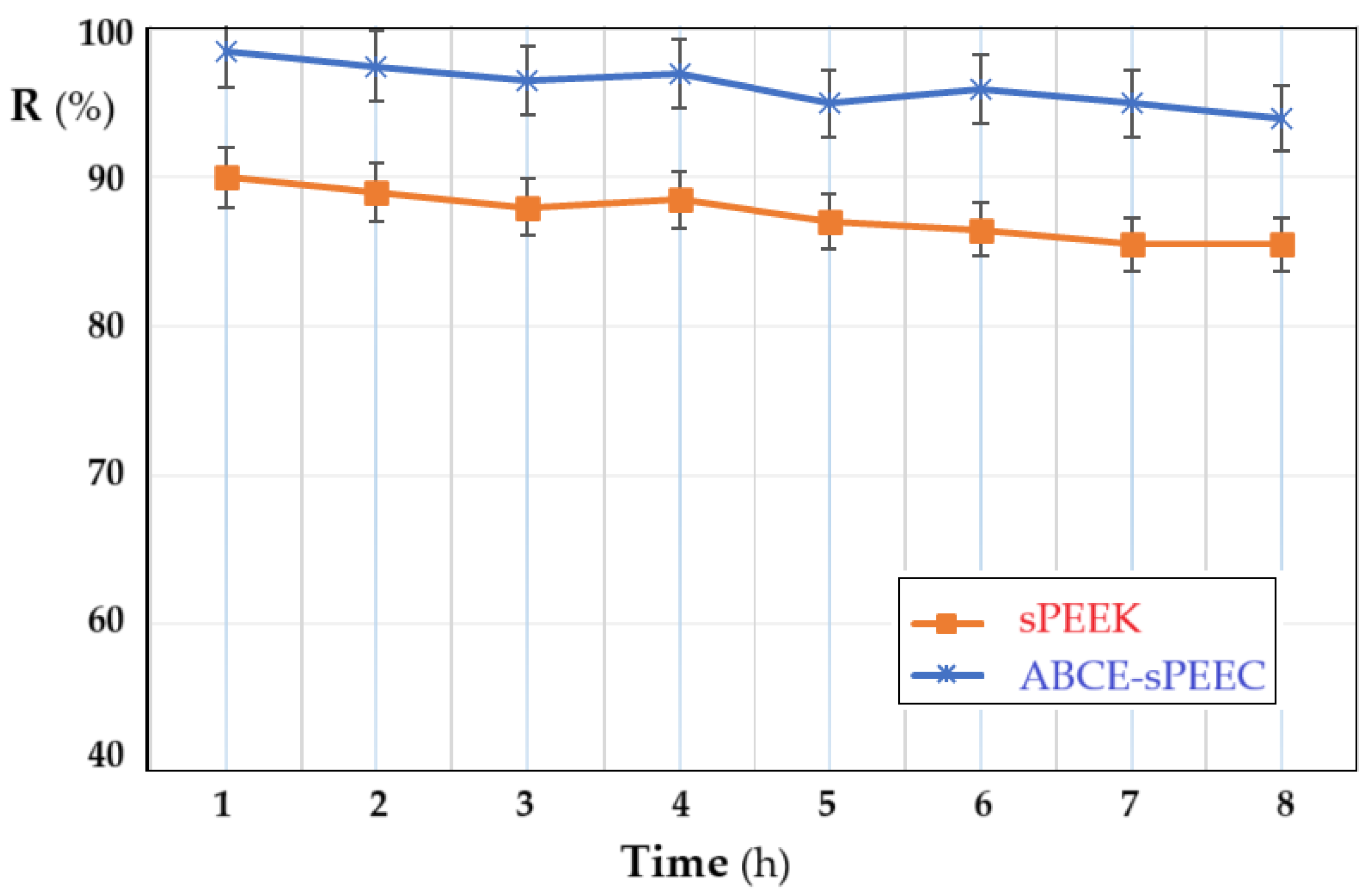

3.2.3. Determination of the Evolution of Nanofiltration Parameters over Time

In order to follow the variation of the retention of the membranes depending on the operating time, the pH of the solution at the value of 4, the concentration of thorium ions of 10⁻5 mol/L, and the stirring regime at 200 rpm were chosen as parameters. Both membranes show a slight decrease in retention, which can be estimated to be within the acceptable limit for the dead-end nanofiltration type working system. The retention of the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane decreases from 98% at the first hour of operation to 95% at eight hours. For the sPEEK membrane, the decrease is from 90% in the first hour of operation, to 85% after eight hours. The obtained values show that in the first hour of operation, the retention mechanism is of adsorption type, after which it switches to the ionic expulsion regime, which determines the acceptable decrease at a relatively long operating time.

The evolution of the permeate flux for the thorium nitrate solution of concentration 10⁻

5 mol/L and pH 4, with the stirring regime at 200 rpm, depending on the operating regime, has the same pattern for both prepared membranes (

Figure 11). From the initial flux, an important decrease is observed until the fourth hour of operation, after which the flux maintains a quasi-constant value.

Figure 11.

Dependence of retention (R%) on operating time: sPEEK membrane (in orange) and ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane (in blue).

Figure 11.

Dependence of retention (R%) on operating time: sPEEK membrane (in orange) and ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane (in blue).

Figure 12.

Dependence of the flux (J) on operating time: sPEEK membrane (in orange) and ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane (in blue).

Figure 12.

Dependence of the flux (J) on operating time: sPEEK membrane (in orange) and ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane (in blue).

The performance of the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane is superior to the performance of the sPEEK reference membrane, in all operating situations.

3.2.4. The Proposed Mechanism of Thorium Ion Retention on sPEEK and ABCE–sPEEK Membranes

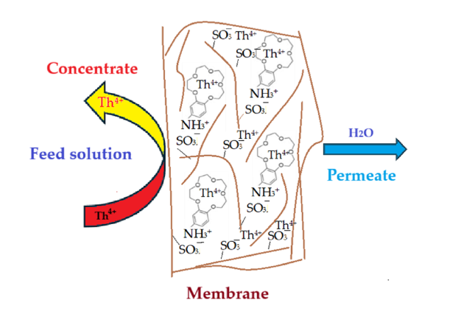

The results obtained in this study show that the sPEEK and ABCE–sPEEK membranes retain the thorium ion through specific superficial interactions followed by ionic expulsion (

Figure 11).

At a working pH, chosen between 0 and 4 units, the ionizing-complexing chemical species interact differently with Th

4⁺ ion (

Table 3).

The choice of sPEEK membrane was made for comparison with the newly prepared composite membrane ABCE–sPEEK (

Figure 13). The reference sPEEK membrane retains the thorium ion due to its strong acidity (pKa = 2) that manifests as such in the acidic environment) with pH 0 to pH 2, and as sulfonated anion at pH 2 to 4. The thorium ion retention occurs at the surface of sPEEK membrane (

Figure 13 a,c,e). This retention of the thorium ion does not completely annihilate the 4+ charge. A large part of the thorium ions accumulates on the surface, which is justified by the ionic expulsion from the nanofiltration process [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72].

In the case of the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane (

Figure 13b,d,f), it was desired to combine the effect of the sulfonic groups of sPEEK with that of ABCE. The choice of the crown ether is justified because the ionic radius of the thorium ion (r = 179 pm) is similar to that of sodium (r = 180 pm) with which this ether specifically complexes (

Figure 13b).

4. Conclusions

The toxicity of thorium is less related to the fact that it is a radioactive element, because the half-life is extremely long. However, being a heavy element, its removal from aqueous systems is imperative.

If we consider that it is desired to remove thorium from waters in isolated areas (for example, mining operations, mountain areas, ...), one of the accessible and efficient processes would be the membrane process. In this paper, nanofiltration is approached as a procedure for removing thorium from dilute synthetic aqueous solutions.

The composite membrane that is proposed as a study is made of sulfonated polyether ether ketone (sPEEK) in which Amino–Benzo–15C5–Ether (ABCE) is incorporated.

The performances of the nanofiltration process are compared between a sPEEK membrane and the composite membrane (ABCE–sPEEK), prepared by the same procedure.

The membranes were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive X–ray spectroscopy EDAX, thermal analysis (TG and DSC) and from the perspective of thorium removal performance.

For all test parameters: pH and thorium ion concentration, working pressure and stirring regime, the composite membrane (ABCE–sPEEK) has superior performance compared to the sPEEK membrane.

Thorium retention for the composite membrane (ABCE–sPEEK) reaches a maximum of 98% compared to the sPEEK membrane which does not exceed 90%.

The fluxes determined under the optimal conditions resulting from the study (pressure, stirring regime, concentration and pH of the thorium solution) are a maximum of 16 L·m⁻2·h⁻1 for the ABCE–sPEEK composite membrane, and 15 L·m⁻2·h⁻1 for the sPEEK membrane.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.N., A.C.N., and V.-A.G.; methodology, A.C.N., G.N., P.C.A., and L.M.; validation, L.M., S.-K.T., and A.R.G.; formal analysis, G.N., A.C.N., A.R.G., and L.M.; investigation, G.N., L.M., P.C.A., G.T.M., V.-A.G.; A.C.N., A.R.G. and V.E.M.; resources, A.C.N., S.-K.T., and G.N.; data curation, L.M., A.C.N., A.R.G., V.-A.G. writing—original draft preparation, A.C.N., G.N., and V.-A.G.; writing—review and editing, G.N., A.C.N., A.R.G. and V.-A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Romanian Government for providing access to the research infrastructure of the National Center for Micro and Nanomaterials through the National Program titled “Installations and Strategic Objectives of National Interest”. The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable help and friendly assistance of Eng. Roxana Truşcă for performing the microscopy analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Poliakovska, K.; Annesley, I.R.; Hajnal, Z. Geophysical Constraints to the Geological Evolution and Genesis of Rare Earth Element–Thorium–Uranium Mineralization in Pegmatites at Alces Lake, SK, Canada. Minerals 2024, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, R.K.; De Melo, L.G.T.C.; Santos, R.M.; Yoon, H.S. An overview of thorium as a prospective natural resource for future energy. Frontiers in Energy Research 2023, 11, 1132611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushakov, S.V.; Hong, Q.-J.; Gilbert, D.A.; Navrotsky, A.; Walle, A.v.d. Thorium and Rare Earth Monoxides and Related Phases. Materials 2023, 16, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serge, A.B.M.; Didier, T.S.S.; Samuel, B.G.; Kranrod, C.; Omori, Y.; Hosoda, M.; Saïdou; Tokonami, S. Assessment of Radiological Risks due to Indoor Radon, Thoron and Progeny, and Soil Gas Radon in Thorium-Bearing Areas of the Centre and South Regions of Cameroon. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caridi, F.; Paladini, G.; Marguccio, S.; Belvedere, A.; D’Agostino, M.; Messina, M.; Crupi, V.; Venuti, V.; Majolino, D. Evaluation of Radioactivity and Heavy Metals Content in a Basalt Aggregate for Concrete from Sicily, Southern Italy: A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelić, M.; Mihaljev, Ž.; Živkov Baloš, M.; Popov, N.; Gavrilović, A.; Jug-Dujaković, J.; Ljubojević Pelić, D. The Activity of Natural Radionuclides Th-232, Ra-226, K-40, and Na-22, and Anthropogenic Cs-137, in the Water, Sediment, and Common Carp Produced in Purified Wastewater from a Slaughterhouse. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, B.; Carrero, S.; Dong, W.; Joe-Wong, C.; Arora, B.; Fox, P.; Nico, P.; Williams, K.H. River thorium concentrations can record bedrock fracture processes including some triggered by distant seismic events. Nature communications 2023, 14, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.S.; Sharma, S.; Maity, J.P.; Martín-Ramos, P.; Fiket, Ž.; Bhattacharya, P.; Zhu, Y. Occurrence of uranium, thorium and rare earth elements in the environment: A review. Frontiers in environmental science 2023, 10, 1058053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, V.K. Thorium as an abundant source of nuclear energy and challenges in separation science. Radiochimica Acta 2023, 111, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aita, S.K.; Abdel-Azeem, M.M.; Abu Khoziem, H.A.; Aly, G.A.; Mahdy, N.M.; Ismail, A.M.; Ali, H.H. Tracking of uranium and thorium natural distribution in the chemical fractions of the Nile Valley and the Red Sea phosphorites, Egypt. Carbonates and Evaporites 2024, 39, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesenko, S.V.; Emlyutina, E.S. Thorium Concentrations in Terrestrial and Freshwater Organisms: A Review of the World Data. Biology Bulletin 2023, 50, 3330–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, B.; Carrero, S.; Dong, W.; Joe-Wong, C.; Arora, B.; Fox, P.; Nico, P.; Williams, K.H. River thorium concentrations can record bedrock fracture processes including some triggered by distant seismic events. Nature communications 2023, 14, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fesenko, S.V.; Emlutina, E.S. Thorium concentrations in the environment: A review of the global data. Biology Bulletin 2021, 48, 2086–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, U.E.; Khandaker, M.U. Viability of thorium-based nuclear fuel cycle for the next generation nuclear reactor: Issues and prospects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 97, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.L.; Lu, Y.; Yang, D.D.; Li, X.H.; Gong, M.M. Purification of thorium by precipitation. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry 2021, 327, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehuddin, A.H.J.M.; Ismail, A.F.; Aziman, E.S.; Mohamed, N.A.; Teridi, M.A.M.; Idris, W.M.R. Production of high-purity ThO2 from monazite ores for thorium fuel-based reactor. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2021, 136, 103728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabi, H.R.; Milani, S.A.; Abolghasemi, H.; Zahakifar, F. Recovery and transport of thorium (IV) through polymer inclusion membrane with D2EHPA from nitric acid solutions. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2021, 327, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; He, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Weng, H.; Lin, M. An Effective Process for the Separation of U(VI), Th(IV) from Rare Earth Elements by Using Ionic Liquid Cyphos IL 104. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 3422–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkonen, E.; Virtanen, E.J.; Moilanen, J.O. α-Aminophosphonates, -Phosphinates, and -Phosphine Oxides as Extraction and Precipitation Agents for Rare Earth Metals, Thorium, and Uranium: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, Y. Polymeric Materials for Rare Earth Elements Recovery. Gels 2023, 9, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T.A.; Sarı, A.; Tuzen, M. Development and characterization of bentonite-gum arabic composite as novel highly-efficient adsorbent to remove thorium ions from aqueous media. Cellulose 2021, 28, 10321–10333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiulina, A.M.; Lizunov, A.V.; Semenov, A.A.; Baulin, D.V.; Baulin, V.E.; Tsivadze, A.Y.; Aksenov, S.M.; Tananaev, I.G. Recovery of Uranium, Thorium, and Other Rare Metals from Eudialyte Concentrate by a Binary Extractant Based on 1,5-bis[2-(hydroxyethoxyphosphoryl)-4-ethylphenoxy]-3-oxapentane and Methyl Trioctylammonium Nitrate. Minerals 2022, 12, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, F.A.; Soylak, M. Separation, preconcentration and inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometric (ICP-MS) determination of thorium(IV), titanium(IV), iron(III), lead(II) and chromium(III) on 2-nitroso-1-naphthol impregnated MCI GEL CHP20P resin. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010, 173, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghaddam, Z.S.; Kaykhaii, M.; Khajeh, M.; Oveisi, A.R. Synthesis of UiO-66-OH zirconium metal-organic framework and its application for selective extraction and trace determination of thorium in water samples by spectrophotometry. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2018, 194, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiou, E.; Pashalidis, I.; Raptopoulos, G.; Paraskevopoulou, P. Efficient Removal of Polyvalent Metal Ions (Eu(III) and Th(IV)) from Aqueous Solutions by Polyurea-Crosslinked Alginate Aerogels. Gels 2022, 8, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, G.; Wei, H.; Liao, W. Selective Extraction and Separation of Ce(IV) from Thorium and Trivalent Rare Earths in Sulfate Medium by an α-Aminophosphonate Extractant. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 167, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, B.A.; Gaber, M.S.; Kandil, A.T. The Removal of Uranium and Thorium from Their Aqueous Solutions by 8-Hydroxyquinoline Immobilized Bentonite. Minerals 2019, 9, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, C.S.A.; Chagas, A.V.B.; de Jesus, R.F.; Barbosa, W.T.; Barbosa, J.D.V.; Ferreira, S.L.C.; Cerdà, V. Synthesis and Application of a New Polymer with Imprinted Ions for the Preconcentration of Uranium in Natural Water Samples and Determination by Digital Imaging. Molecules 2023, 28, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talan, D.; Huang, Q. Separation of Radionuclides from a Rare Earth-Containing Solution by Zeolite Adsorption. Minerals 2021, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbatovskii, K.G. The effect of the adsorption of multicharge cations on the selectivity of a nanofiltration membrane. Colloid Journal 2003, 65, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.R.P.; Paredes, X.; Cristino, A.F.; Santos, F.J.V.; Queirós, C.S.G.P. Ionic Liquids—A Review of Their Toxicity to Living Organisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybak, A.; Rybak, A.; Kolev, S.D. A Modern Computer Application to Model Rare Earth Element Ion Behavior in Adsorptive Membranes and Materials. Membranes 2023, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptakov, V.O.; Milyutin, V.V.; Nekrasova, N.A.; Zelenin, P.G.; Kozlitin, E.A. Nanofiltration Extraction of Uranium and Thorium from Aqueous Solutions. Radiochemistry 2021, 63, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardehali, B.A.; Zaheri, P.; Yousefi, T. The effect of operational conditions on the stability and efficiency of an emulsion liquid membrane system for removal of uranium. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2020, 130, 103532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguel, S.; Samar, M.H. Elimination of rare earth (neodymium (III)) from water by emulsion liquid membrane process using D2EHPA as a carrier in kerosene. Desalination and Water Treatment 2024, 317, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahyari, S.A.; Minuchehr, A.; Ahmadi, S.J.; Charkhi, A. Thorium pertraction through hollow fiber renewal liquid membrane (HFRLM) using Cyanex 272 as carrier. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2017, 100, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammari Allahyari, S.; Charkhi, A.; Ahmadi, S.J.; Minuchehr, A. Modeling and experimental validation of the steady-state counteractive facilitated transport of Th (IV) and hydrogen ions through hollow-fiber renewal liquid membrane. Chemical Papers 2021, 75, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, S.A.; Zahakifar, F.; Faryadi, M. Membrane assisted transport of thorium (IV) across bulk liquid membrane containing DEHPA as ion carrier: Kinetic, mechanism and thermodynamic studies. Radiochimica Acta 2022, 110, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankapati, H.M.; Dankhara, P.M.; Lathiya, D.R.; Shah, B.; Chudasama, U.V.; Choudhary, L.; Maheria, K.C. Removal of lanthanum, cerium and thorium metal ions from aqueous solution using ZrT hybrid ion exchanger. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2021, 47, 101415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziman, E.S.; Mohd Salehuddin, A.H.J.; Ismail, A.F. Remediation of thorium (IV) from wastewater: Current status and way forward. Separation & Purification Reviews 2021, 50, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, G.T.; Albu, P.C.; Nechifor, A.C.; Grosu, A.R.; Tanczos, S.-K.; Grosu, V.-A.; Ioan, M.-R.; Nechifor, G. Thorium Removal, Recovery and Recycling: A Membrane Challenge for Urban Mining. Membranes 2023, 13, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covaliu-Mierlă, C.I.; Păunescu, O.; Iovu, H. Recent Advances in Membranes Used for Nanofiltration to Remove Heavy Metals from Wastewater: A Review. Membranes 2023, 13, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, A.E.D.; Mostafa, E. Nanofiltration Membranes for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Solutions: Preparations and Applications. Membranes 2023, 13, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, J.B.; Santos, T.D.; Zaparoli, M.; de Almeida, A.C.A.; Costa, J.A.V.; de Morais, M.G. An Overview of Nanofiltration and Nanoadsorption Technologies to Emerging Pollutants Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, G.T.; Albu, P.C.; Nechifor, A.C.; Grosu, A.R.; Popescu, D.I.; Grosu, V.-A.; Marinescu, V.E.; Nechifor, G. Simultaneously Recovery of Thorium and Tungsten through Hybrid Electrolysis–Nanofiltration Processes. Toxics 2024, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimbru, A.M.; Rikabi, A.A.K.K.; Oprea, O.; Grosu, A.R.; Tanczos, S.-K.; Simonescu, M.C.; Pașcu, D.; Grosu, V.-A.; Dumitru, F.; Nechifor, G. pH and pCl Operational Parameters in Some Metallic Ions Separation with Composite Chitosan/Sulfonated Polyether Ether Ketone/Polypropylene Hollow Fibers Membranes. Membranes 2022, 12, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechifor, A.C.; Ruse, E.; Nechifor, G.; Serban, B. Membrane materials. II. Electrodialysis with membranes of chemically modified polyetherketones. Rev. Chim. 2002, 53, 472–482. [Google Scholar]

- Baicea, C.; Nechifor, A.C.; Vaireanu, D.I.; Gales, O.; Trusca, R.; Voicu, S.I. Sulfonated poly (ether ether ketone)–activated polypyrrole composite membranes for fuel cells. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater.-Rapid Commun. 2011, 5, 1181–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Din, I.S.; Cimbru, A.M.; Rikabi, A.A.K.K.; Tanczos, S.K.; Ticu Cotorcea, S.; Nechifor, G. Iono-molecular Separation with Composite Membranes VI. Nitro-phenol separation through sulfonated polyether ether ketone on capillary polypropylene membranes. Rev. Chim. 2018, 69, 1603–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Galier, S.; Roux-de Balmann, H. Description of the variation of retention versus pH in nanofiltration of organic acids. Journal of Membrane Science 2021, 637, 119588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashine, N.; Deb, M.K.; Mishra, R.K. Spectrophotometric determination of thorium in standard samples and monazite sands based on the floated complex of thorium with N-hydroxy-N,N’-diphenylbenzamidine and thorin. Anal Bioanal Chem. 1996, 355, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prioteasa, P.; Marinescu, V.; Bara, A.; Iordoc, M.; Teisanu, A.; Banciu, C.; Meltzer, V. Electrodeposition of Polypyrrole on Carbon Nanotubes/Si in the Presence of Fe Catalyst for Application in Supercapacitors. Rev. Chim. 2015, 66, 820–824. [Google Scholar]

- Zamfir, L.-G.; Rotariu, L.; Marinescu, V.E.; Simelane, X.T.; Baker, P.G.L.; Iwuoha, E.I.; Bala, C. Non-enzymatic polyamic acid sensors for hydrogen peroxide detection. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2016, 226, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chircov, C.; Bejenaru, I.T.; Nicoară, A.I.; Bîrcă, A.C.; Oprea, O.C.; Tihăuan, B. Chitosan-Dextran-Glycerol Hydrogels Loaded with Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Wound Dressing Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimulescu, I.A.; Nechifor, A.C.; Bǎrdacǎ, C.; Oprea, O.; Paşcu, D.; Totu, E.E.; Albu, P.C.; Nechifor, G.; Bungău, S.G. Accessible Silver-Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as a Nanomaterial for Supported Liquid Membranes. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechifor, G.; Păncescu, F.M.; Albu, P.C.; Grosu, A.R.; Oprea, O.; Tanczos, S.-K.; Bungău, C.; Grosu, V.-A.; Ioan, M.-R.; Nechifor, A.C. Transport and Separation of the Silver Ion with n–decanol Liquid Membranes Based on 10–undecylenic Acid, 10–undecen–1–ol and Magnetic Nanoparticles. Membranes 2021, 11, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechifor, G.; Grosu, A.R.; Ferencz, A.; Tanczos, S.-K.; Goran, A.; Grosu, V.-A.; Bungău, S.G.; Păncescu, F.M.; Albu, P.C.; Nechifor, A.C. Simultaneous Release of Silver Ions and 10–Undecenoic Acid from Silver Iron–Oxide Nanoparticles Impregnated Membranes. Membranes 2022, 12, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechifor, A.C.; Pîrțac, A.; Albu, P.C.; Grosu, A.R.; Dumitru, F.; Dimulescu, I.A.; Oprea, O.; Pașcu, D.; Nechifor, G.; Bungău, S.G. Recuperative Amino Acids Separation through Cellulose Derivative Membranes with Microporous Polypropylene Fiber Matrix. Membranes 2021, 11, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Duan, T.; Song, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, H. Effects of soil pH and organic matter on distribution of thorium fractions in soil contaminated by rare-earth industries. Talanta 2008, 77, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, D.; Herman, J.S. The mobility of thorium in natural waters at low temperatures. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1980, 44, 1753–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Gong, Y.; Jiang, F.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, T.; Long, D.; Li, Q. Electrochemical behavior of Th (IV) and its electrodeposition from ThF4-LiCl-KCl melt. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 196, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpech, S.; Carrière, C.; Chmakoff, A.; Martinelli, L.; Rodrigues, D.; Cannes, C. Corrosion Mitigation in Molten Salt Environments. Materials 2024, 17, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pîrțac, A.; Nechifor, A.C.; Tanczos, S.-K.; Oprea, O.C.; Grosu, A.R.; Matei, C.; Grosu, V.-A.; Vasile, B.Ș.; Albu, P.C.; Nechifor, G. Emulsion Liquid Membranes Based on Os–NP/n–Decanol or n–Dodecanol Nanodispersions for p–Nitrophenol Reduction. Molecules 2024, 29, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żyłła, R.; Ledakowicz, S.; Boruta, T.; Olak-Kucharczyk, M.; Foszpańczyk, M.; Mrozińska, Z.; Balcerzak, J. Removal of Tetracycline Oxidation Products in the Nanofiltration Process. Water 2021, 13, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhalim, N.S.; Kasim, N.; Mahmoudi, E.; Shamsudin, I.J.; Mohammad, A.W.; Mohamed Zuki, F.; Jamari, N.L.-A. Rejection Mechanism of Ionic Solute Removal by Nanofiltration Membranes: An Overview. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewerin, T.; Elshof, M.G.; Matencio, S.; Boerrigter, M.; Yu, J.; de Grooth, J. Advances and Applications of Hollow Fiber Nanofiltration Membranes: A Review. Membranes 2021, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Quirós, P.; Montenegro-Landívar, M.F.; Reig, M.; Vecino, X.; Saurina, J.; Granados, M.; Cortina, J.L. Integration of Nanofiltration and Reverse Osmosis Technologies in Polyphenols Recovery Schemes from Winery and Olive Mill Wastes by Aqueous-Based Processing. Membranes 2022, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bóna, Á.; Galambos, I.; Nemestóthy, N. Progress towards Stable and High-Performance Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Nanofiltration Membranes for Future Wastewater Treatment Applications. Membranes 2023, 13, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, M.; Mitko, K.; Skóra, P.; Dydo, P.; Jakóbik-Kolon, A.; Warzecha, A.; Tyrała, K. Improving the Performance of a Salt Production Plant by Using Nanofiltration as a Pretreatment. Membranes 2022, 12, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.N.R.; Mohammad, A.W.; Mahmoudi, E.; Ang, W.L.; Leo, C.P.; Teow, Y.H. An Overview of the Modification Strategies in Developing Antifouling Nanofiltration Membranes. Membranes 2022, 12, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarinejad, S.; Esfahani, M.R. A Review on the Nanofiltration Process for Treating Wastewaters from the Petroleum Industry. Separations 2021, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.E.A. Nanofiltration Process for Enhanced Treatment of RO Brine Discharge. Membranes 2021, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).