Submitted:

26 September 2024

Posted:

27 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

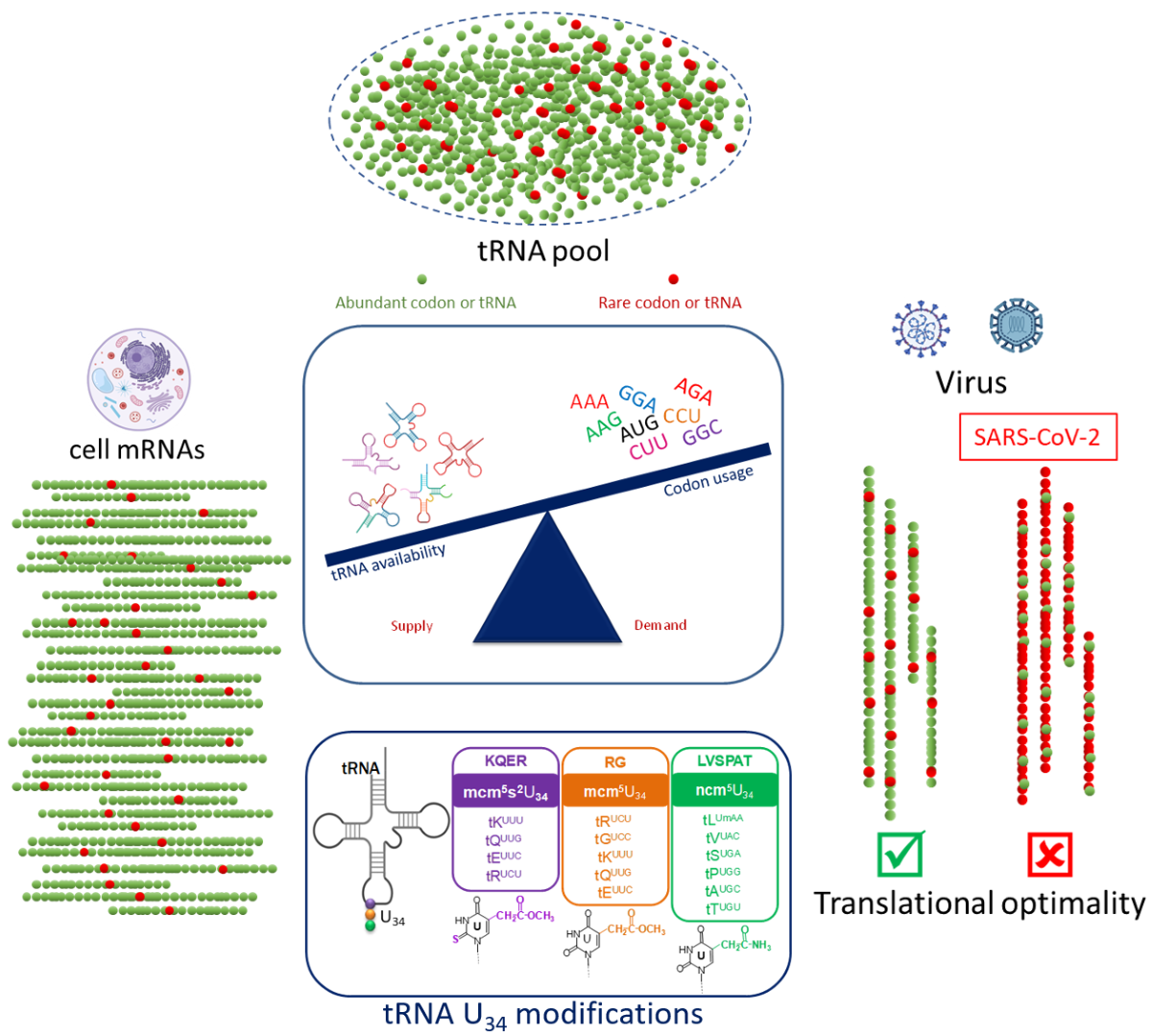

1. Introduction: The Critical Role of Codon Bias in Translation Efficiency

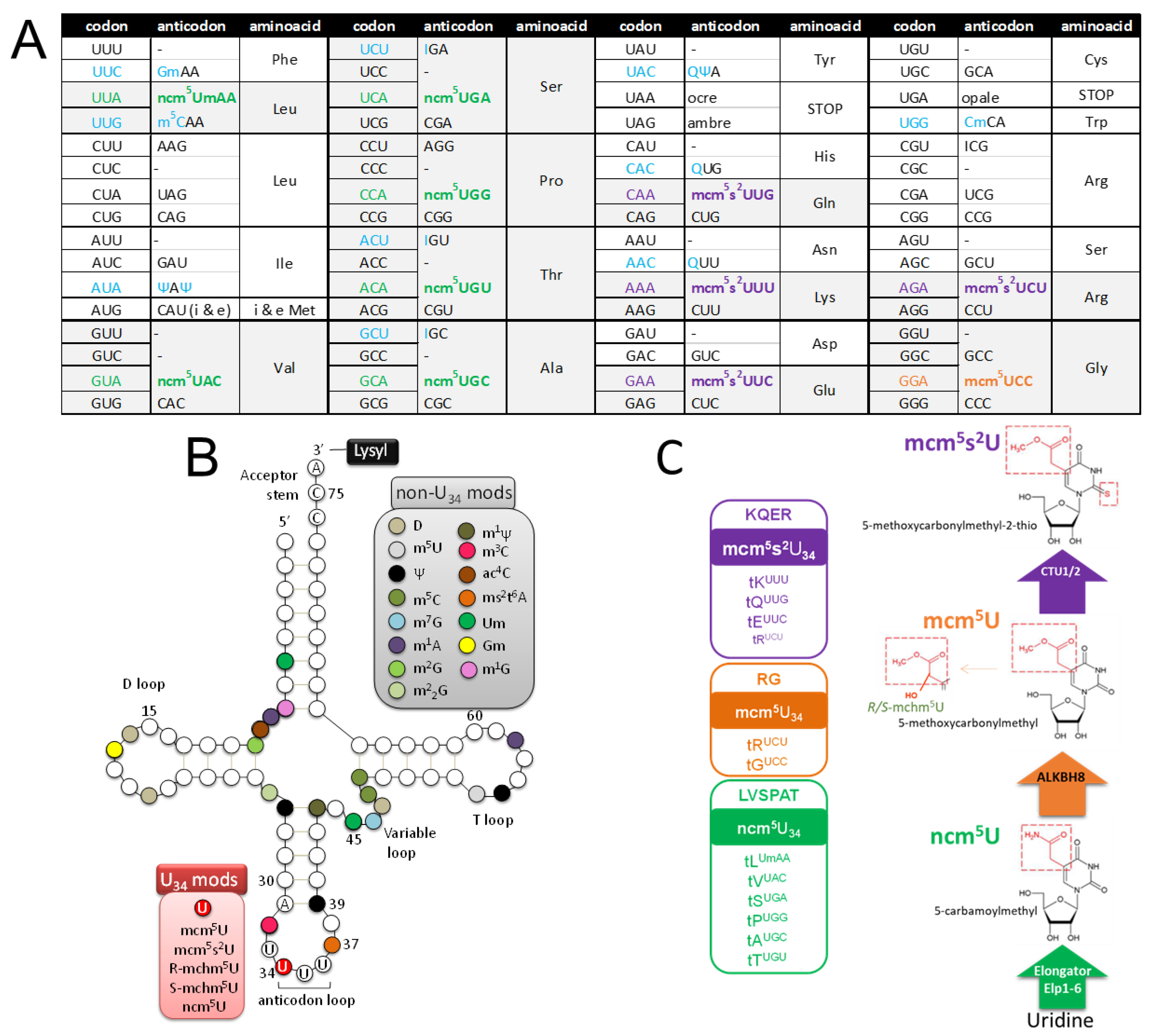

1.2. Codon Bias and tRNA Pool

1.3. Viral Manipulation of Host Translational Machinery through tRNA Modifications

2. Results and Discussion

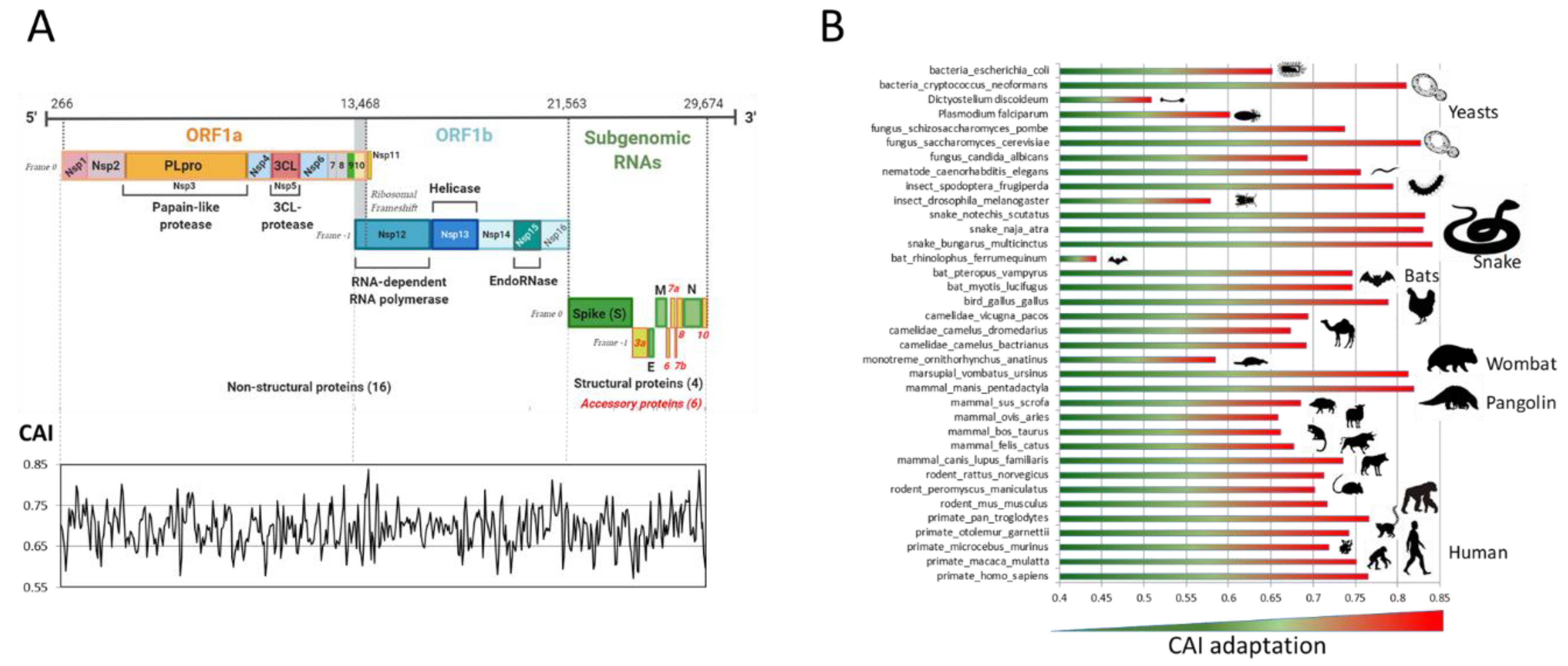

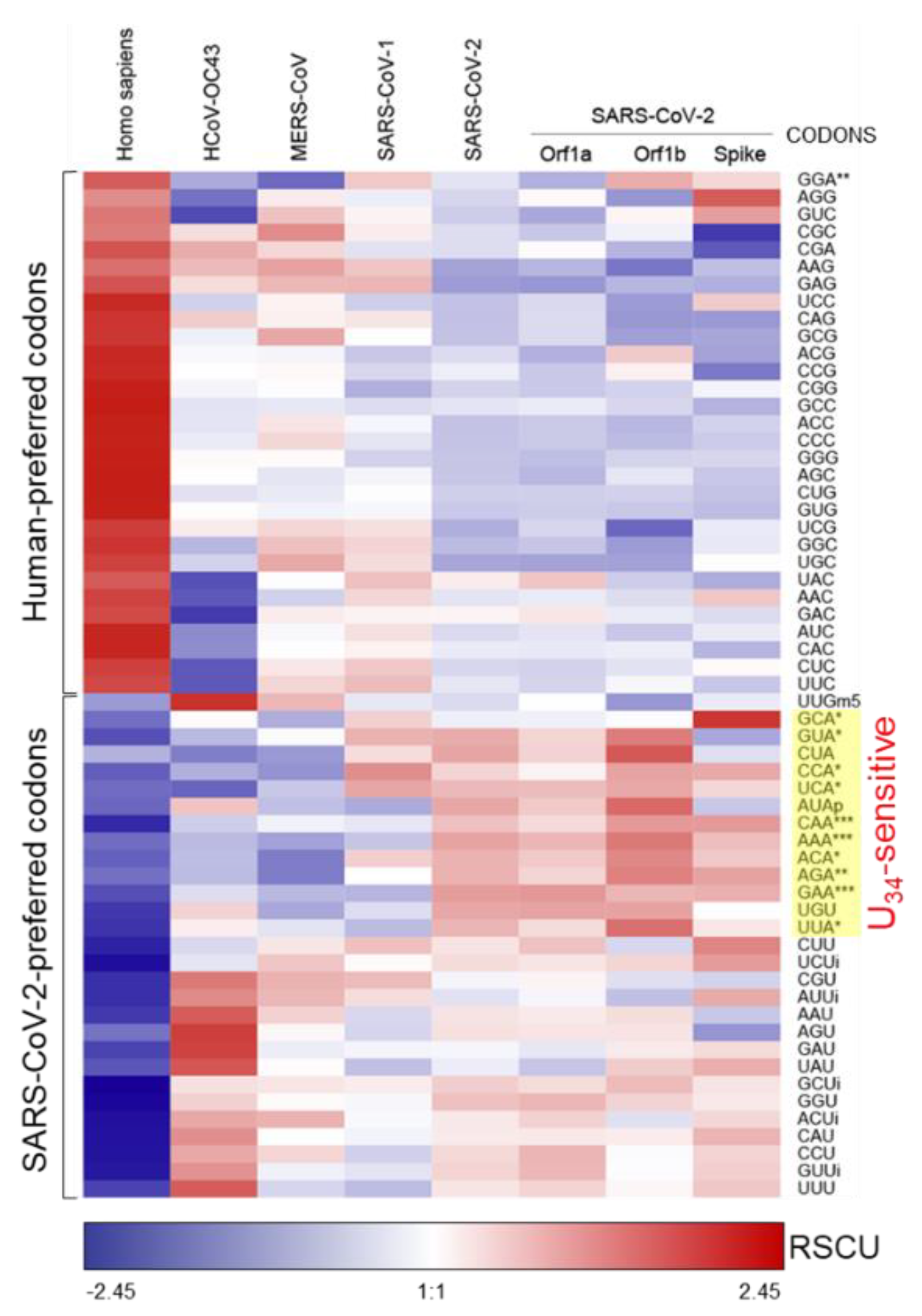

2.1. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Codon Bias

2.1.1. Codon Bias Analysis: A Tool to Shed Light on Virus History, Origins and Evolution

2.1.2. SARS-CoV-2 Adaptation to Various Species

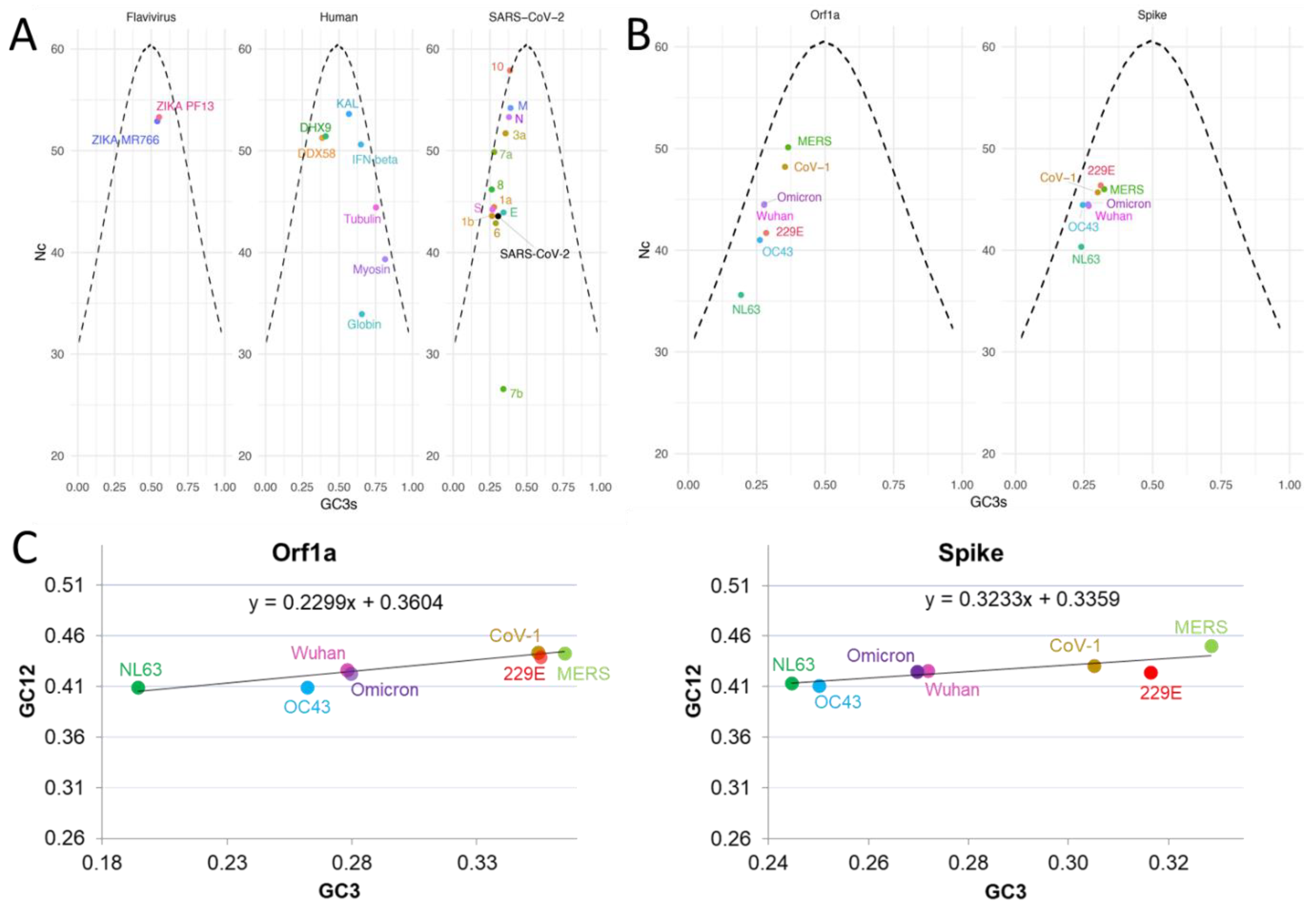

2.1.3. Nc and Neutrality Plots

2.2. SARS-CoV-2 Genome is Enriched in U34-Sensitive Codons

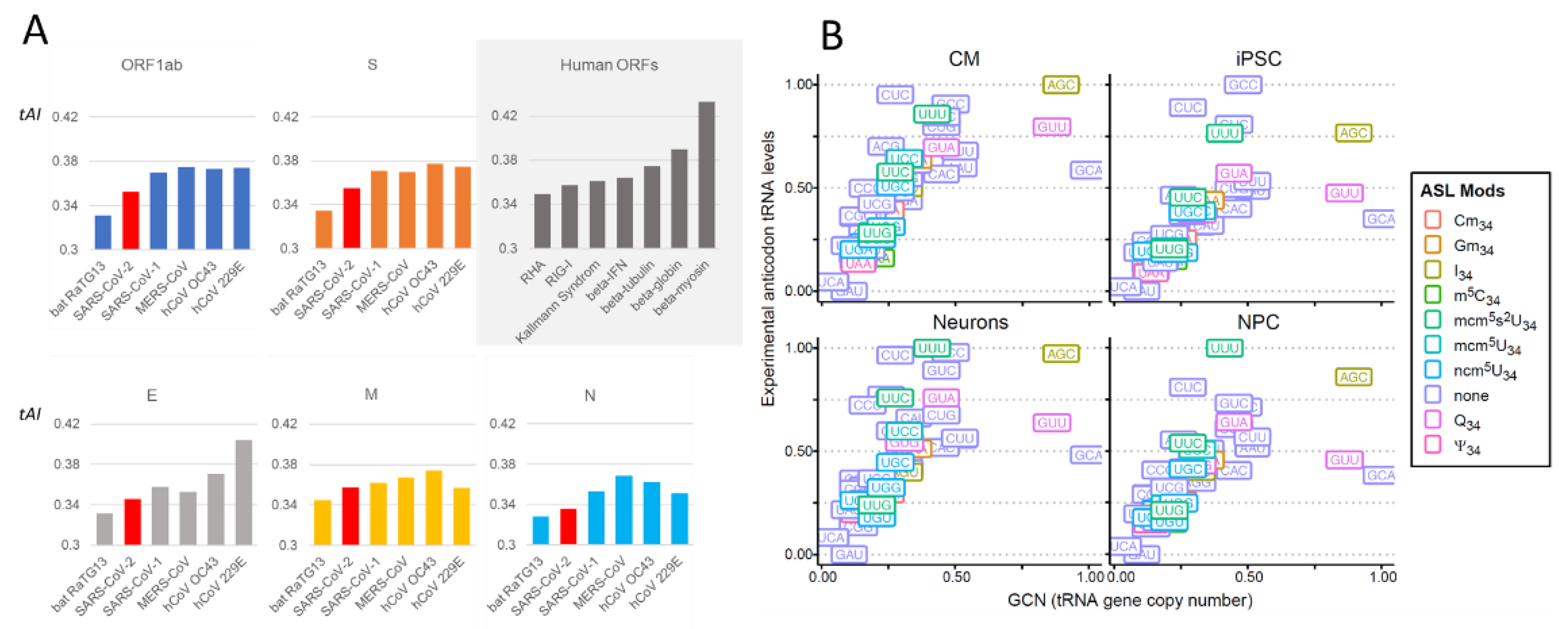

2.2.1. Comparison of Coronavirus Translation Adaptation (tAI)

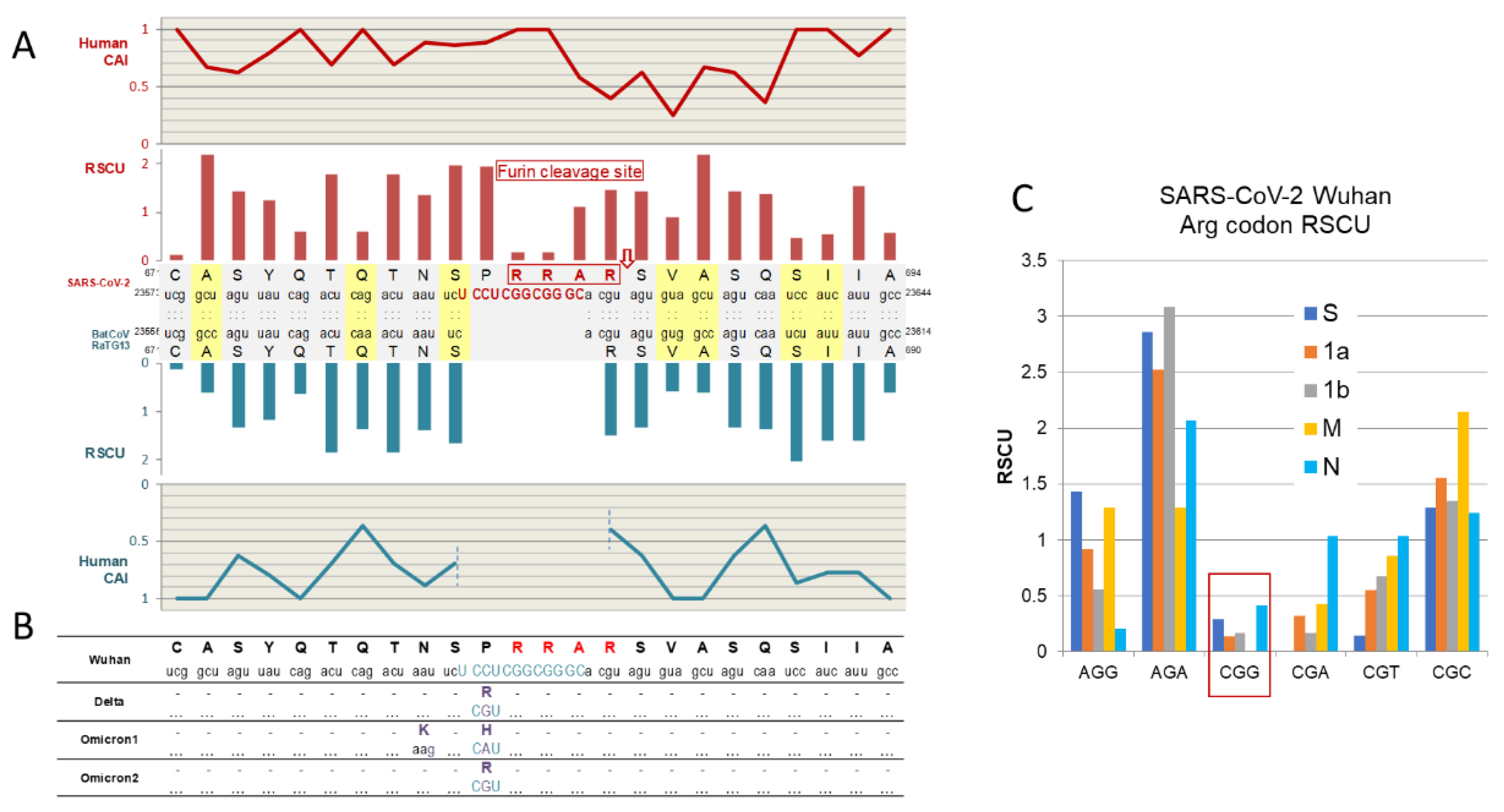

2.2.2. The Enigma of Spike Protein’s Furin Cleavage Site

2.3. Suitability of the SARS-CoV2 Highly Biased Codon Composition for Viral Translation in Target Tissues

2.3.1. tRNA Modifications: Do RNA Viruses Have a Wobble?

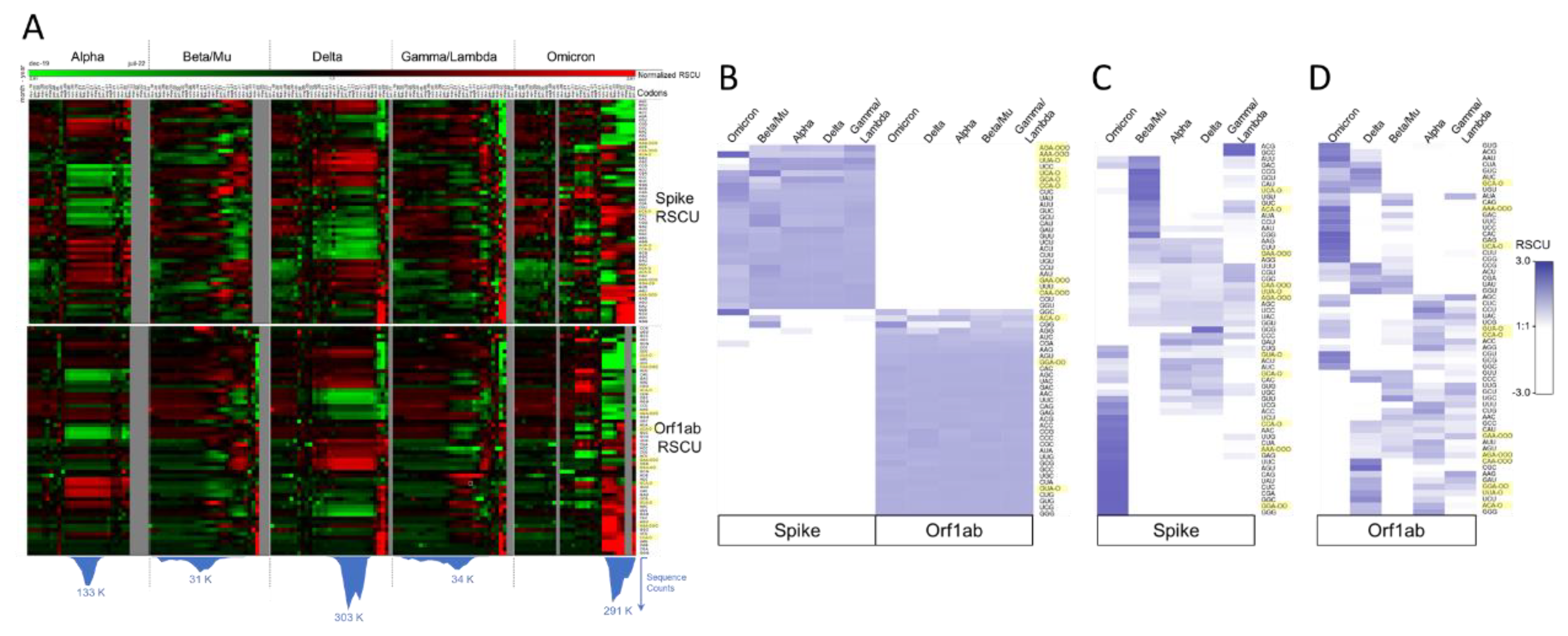

2.3.2. SARS-CoV-2 Codon Bias Dynamics during the Pandemic

2.4. Hypothesis: Virus-Driven Manipulation of the tRNA Pool and tRNA Modifications Forces Translation of SARS-CoV-2 Genes

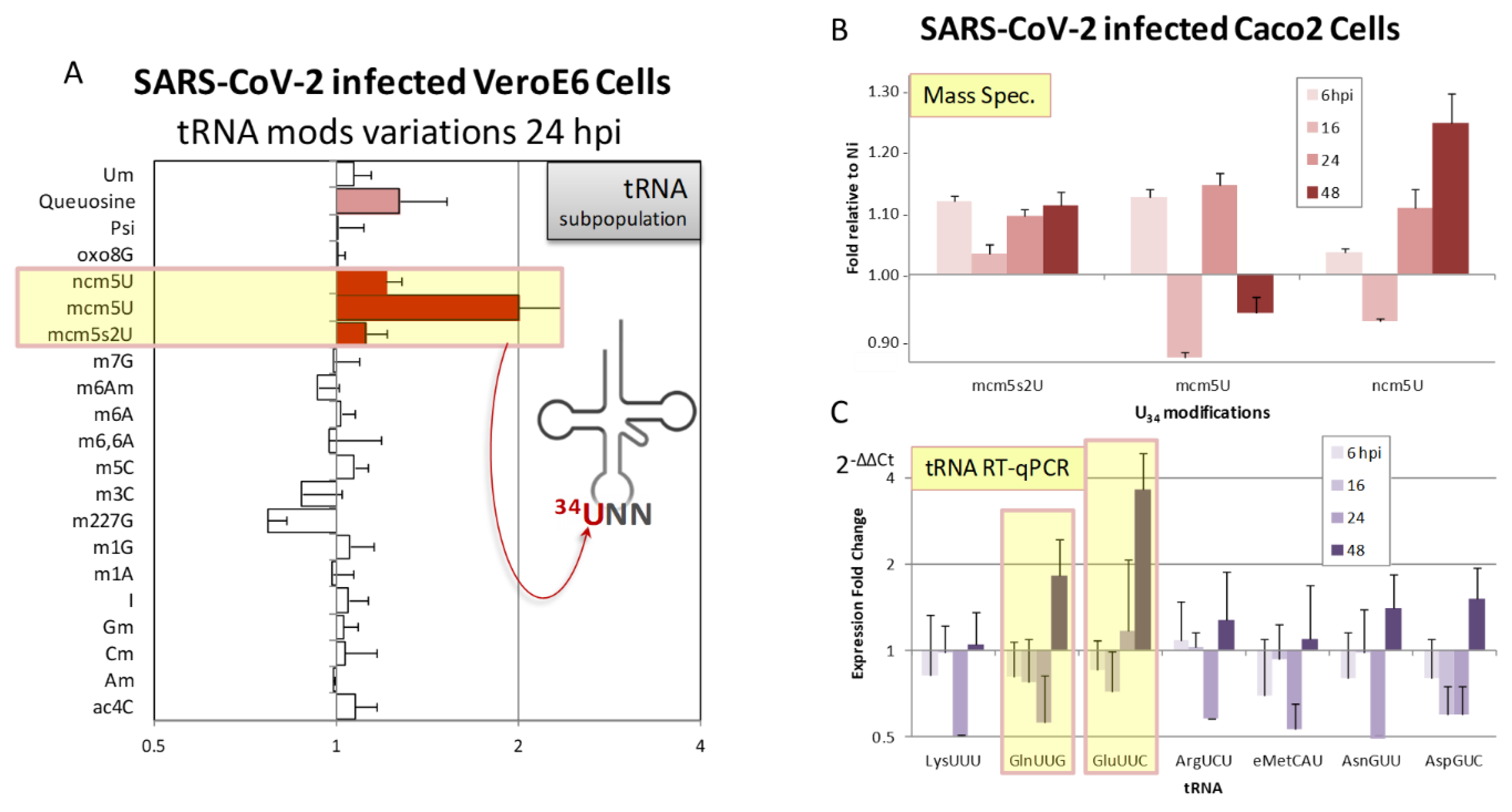

2.5. Evidences Supporting the Ability of SARS-CoV-2 to Exploit the tRNA Epitranscriptome in Order to Favor Viral Translation

2.5.1. Potential Manipulation of tRNAs by SARS-CoV-2

2.5.2. Experimental Data Revealing SARS-CoV-2 Induced tRNA Epitranscriptome Modulations

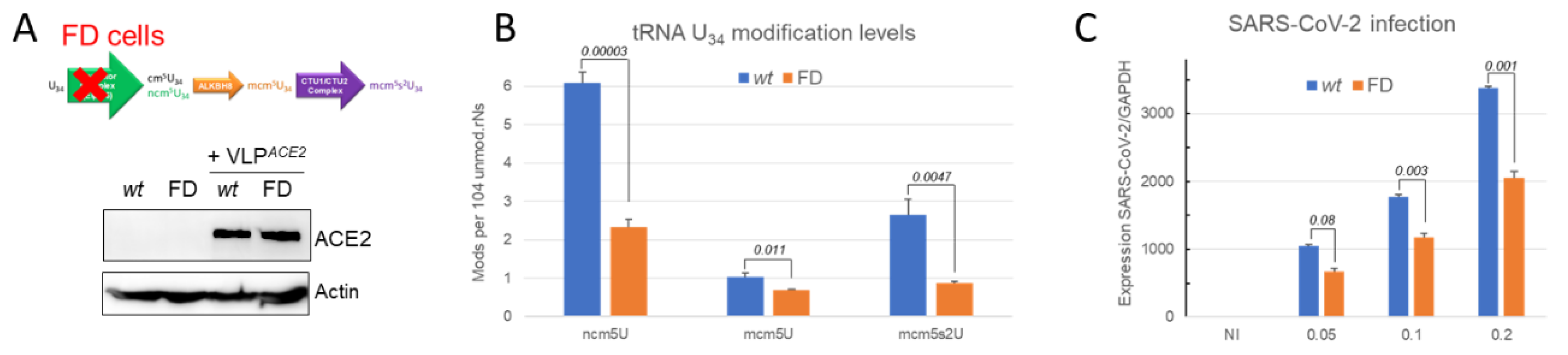

2.5.3. SARS-CoV-2 Infection is Impaired when the tRNA U34 Modification Pathway is Disrupted

3. Concluding Remarks

3.1. Is altering tRNA Epitranscriptome a Common Viral Strategy?

3.2. Future Priority Investigation Areas

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Bio-Informatics - Codon Analysis

4.2. SARS-CoV-2 Sequences

4.3. Experimental Data

4.3.1. Cells and Viruses

4.3.2. Quantification of tRNA Modifications by Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

4.3.3. Assays for Viral Replication

Appendix A. Virus Sequences

| Virus genus | Name | Accession |

| Alphacoronavirus | Human CoV NL63 | MK334043.1 |

| Human CoV 229E | MN306046.1 | |

| Betacoronavirus | BatCoV RaTG13 | MN996532.2 |

| Human CoV-OC43 | KF530087.1 | |

| MERS-CoV | JX869059.2 | |

| SARS-CoV-1 | KY352407.1 | |

| SARS-CoV-2 FRA | european-virus-archive betacovfranceidf03722020 | |

| SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan | NC_045512.2 | |

| SARS-CoV-2 Omicron | ON248829.1 | |

| Flavivirus | Zika MR766 | MK105975 |

| Zika PF13 | KY766069 |

Appendix B. tRNA RTqPCR Primers

| Primer | Target tRNA | Sequence (5‘→3’) |

| tLys-TTT-For | tRNA-Lys-TTT-3-1 | TCAGTCGGTAGAGCATCAGA |

| tLys-TTT-Rev | tRNA-Lys-TTT-3-1 | CCCGAACAGGGACTTGAAC |

| tGln-TTG-For | tRNA-Gln-TTG-1-1 | TGGTGTAATGGTTAGCACTCTG |

| tGln-TTG-Rev | tRNA-Gln-TTG-1-1 | CCGAGATTTGAACTCGGATCG |

| tGlu-TTC-For | tRNA-Glu-TTC-1-1 | CATATGGTCTAGCGGTTAGGATTC |

| tGlu-TTC-Rev | tRNA-Glu-TTC-1-1 | CCCATACCGGGAGTCGAA |

| tArg-TCT-For | tRNA-Arg-TCT-1-1 | CCGTGGCGCAATGGATA |

| tArg-TCT-Rev | tRNA-Arg-TCT-1-1 | CTCGAACCCGGAACCTTT |

| tAsn-GTT-For | tRNA-Asn-GTT-1-1 | TGTGGCGCAATCGGTTAG |

| tAsn-GTT-Rev | tRNA-Asn-GTT-1-1 | GAACCACCAACCTTTCGGTTA |

| tAsp-GTC-For | tRNA-Asp-GTC-2-9 | GTATAGTGGTGAGTATCCCC |

| tAsp-GTC-Rev | tRNA-Asp-GTC-2-9 | AATCGAACCCCGGTCTCC |

| teMet-CAT-For | tRNA-Met-CAT-4-2 | GCGTCAGTCTCATAATCTGA |

| teMet-CAT-Rev | tRNA-Met-CAT-4-2 | GCCCTCTCTGAGGCTCGAAC |

| 103-For | miRNA103a-3p | GCTTCTTTACAGTGCTGCCT |

| 103-Rev | miRNA103a-3p | TTCATAGCCCTGTACAATGCT |

References

- Hershberg, R.; Petrov, D.A. General Rules for Optimal Codon Choice. PLoS Genet 2009, 5, e1000556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grantham, R. , Gautier, C., Gouy, M., Mercier, R.; Pavé, A. Codon catalog usage and the genome hypothesis. Nucleic Acids Res 1980, 8, r49–r62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y. , de Lima Hedayioglu, F., Kalfon, J., Chu, D.; von der Haar, T. Hidden patterns of codon usage bias across kingdoms. J R Soc Interface 2020, 17, 20190819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvathy, S.T. , Udayasuriyan, V.; Bhadana, V. Codon usage bias. Mol Biol Rep 2022, 49, 539–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaney, J.L.; Clark, P.L. Roles for Synonymous Codon Usage in Protein Biogenesis. Annual Review of Biophysics 2015, 44, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supek, F. The Code of Silence: Widespread Associations Between Synonymous Codon Biases and Gene Function. Journal of Molecular Evolution 2016, 82, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barozai, M.Y. , Kakar, A.; Din, D. The relationship between codon usage bias and salt resistant genes in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. Pure and Applied Biology 2012, 1, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, I.; et al. Codon usage of highly expressed genes affects proteome-wide translation efficiency. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, E4940–E4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quax, T.E.F. , Claassens, N.J., Söll, D.; van der Oost, J. Codon Bias as a Means to Fine-Tune Gene Expression. Mol Cell 2015, 59, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, J.B.; Kudla, G. Synonymous but not the same: the causes and consequences of codon bias. Nat Rev Genet 2011, 12, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. A code within the genetic code: codon usage regulates co-translational protein folding. Cell Commun Signal 2020, 18, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; et al. Genome-wide role of codon usage on transcription and identification of potential regulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118, e2022590118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z. , Dang, Y., Zhou, M., Yuan, H.; Liu, Y. Codon usage biases co-evolve with transcription termination machinery to suppress premature cleavage and polyadenylation. Elife 2018, 7, e33569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mordstein, C.; et al. Codon Usage and Splicing Jointly Influence mRNA Localization. Cell Syst 2020, 10, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P.M. , Tuohy, T.M.F.; Mosurski, K.R. Codon usage in yeast: cluster analysis clearly differentiates highly and lowly expressed genes. Nucleic Acids Research 1986, 14, 5125–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulet, D. , David, A.; Rivals, E. Ribo-seq enlightens codon usage bias. DNA Research 2017, 24, 303–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, F.H. Codon--anticodon pairing: the wobble hypothesis. J Mol Biol 1966, 19, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agris, P.F. , Vendeix, F.A.P.; Graham, W.D. tRNA’s wobble decoding of the genome: 40 years of modification. J Mol Biol 2007, 366, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agris, P.F. Wobble position modified nucleosides evolved to select transfer RNA codon recognition: A modified-wobble hypothesis. Biochimie 1991, 73, 1345–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agris, P.F. Decoding the genome: a modified view. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agris, P.F. , Narendran, A., Sarachan, K., Väre, V.Y.P.; Eruysal, E. The Importance of Being Modified: The Role of RNA Modifications in Translational Fidelity. The Enzymes 2017, 41, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, C. , Lünse, C.E.; Mörl, M. tRNA Modifications: Impact on Structure and Thermal Adaptation. Biomolecules 2017, 7, E35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuorto, F.; Lyko, F. Genome recoding by tRNA modifications. Open Biol 2016, 6, 160287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadon, C.; Namy, O. The Importance of the Epi-Transcriptome in Translation Fidelity. Noncoding RNA 2021, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarian, C.; et al. Accurate translation of the genetic code depends on tRNA modified nucleosides. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 16391–16395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Hernandez, A.; et al. Structural and mechanistic basis for enhanced translational efficiency by 2-thiouridine at the tRNA anticodon wobble position. J Mol Biol 2013, 425, 3888–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedialkova, D.D.; Leidel, S.A. Optimization of Codon Translation Rates via tRNA Modifications Maintains Proteome Integrity. Cell 2015, 161, 1606–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.J.O. , Xu, F.; Byström, A.S. Elongator-a tRNA modifying complex that promotes efficient translational decoding. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Gene regulatory mechanisms 2018, 1861, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, U.; et al. A human tRNA methyltransferase 9-like protein prevents tumour growth by regulating LIN9 and HIF1-α. EMBO Mol Med 2013, 5, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungfleisch, J.; et al. CHIKV infection reprograms codon optimality to favor viral RNA translation by altering the tRNA epitranscriptome. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuorto, F.; Lyko, F. Genome recoding by tRNA modifications. Open Biol 2016, 6, 160287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapino, F.; et al. Wobble tRNA modification and hydrophilic amino acid patterns dictate protein fate. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Lin, S. Emerging functions of tRNA modifications in mRNA translation and diseases. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2023, 50, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, W. , Yang, J.-R., Pearson, N.M., Maclean, C.; Zhang, J. Balanced Codon Usage Optimizes Eukaryotic Translational Efficiency. PLOS Genetics 2012, 8, e1002603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Reis, M. , Savva, R.; Wernisch, L. Solving the riddle of codon usage preferences: a test for translational selection. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, 5036–5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabi, R.; Tuller, T. Modelling the efficiency of codon-tRNA interactions based on codon usage bias. DNA Res 2014, 21, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyet, F. , Mouchiroud, D., Duret, L.; Sémon, M. Recombination, meiotic expression and human codon usage. Elife 2017, 6, e27344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, E.M. , Pavon-Eternod, M., Pan, T.; Ribas de Pouplana, L. A Role for tRNA Modifications in Genome Structure and Codon Usage. Cell 2012, 149, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, K.L.M.; et al. Codon-Driven Translational Efficiency Is Stable across Diverse Mammalian Cell States. PLoS Genetics 2016, 12, e1006024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W. , Gallardo-Dodd, C.J.; Kutter, C. Cell type–specific analysis by single-cell profiling identifies a stable mammalian tRNA–mRNA interface and increased translation efficiency in neurons. Genome Res. 2022, 32, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M. , Ramos, B., Soares, A.; Ribeiro, D. Cellular Proteostasis During Influenza A Virus Infection—Friend or Foe? Cells 2019, 8, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavon-Eternod, M.; et al. Vaccinia and influenza A viruses select rather than adjust tRNAs to optimize translation. Nucleic Acids Research 2013, 41, 1914–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandia, R.; et al. Analysis of Nipah Virus Codon Usage and Adaptation to Hosts. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Weringh, A.; et al. HIV-1 Modulates the tRNA Pool to Improve Translation Efficiency. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2011, 28, 1827–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanduc, D. Role of codon usage and tRNA changes in rat cytomegalovirus latency and (re)activation. Journal of Basic Microbiology 2016, 56, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, K.A. , Goodenbour, J.M.; Pan, T. Tissue-specific differences in human transfer RNA expression. PLoS Genetics 2006, 2, 2107–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisien, M. , Wang, X.; Pan, T. Diversity of human tRNA genes from the 1000-genomes project. RNA Biol 2013, 10, 1853–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtipal, N. , Bharadwaj, S.; Kang, S.G. From SARS to SARS-CoV-2, insights on structure, pathogenicity and immunity aspects of pandemic human coronaviruses. Infect Genet Evol 2020, 85, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, Z. , Li, M.; Wang, X. Comparative Review of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and Influenza A Respiratory Viruses. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 552909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabaan, A.A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-COV: A comparative overview. Le infezioni in medicina 2020, 28, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Snijder, E.J. , Decroly, E.; Ziebuhr, J. The Nonstructural Proteins Directing Coronavirus RNA Synthesis and Processing. in Advances in Virus Research 59–126 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Sola, I. , Almazán, F., Zúñiga, S.; Enjuanes, L. Continuous and Discontinuous RNA Synthesis in Coronaviruses. Annual Review of Virology 2015, 2, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadler, K.; et al. SARS — beginning to understand a new virus. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2003, 1, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; et al. Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from COVID-19 virus. Science 2020, 368, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Leader sequences of coronavirus are altered during infection. Frontiers in Bioscience 2018, 23, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, T.; et al. Structural basis of RNA cap modification by SARS-CoV-2. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.-H.; et al. Characterization of the Role of Hexamer AGUAAA and Poly(A) Tail in Coronavirus Polyadenylation. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0165077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, F.K. The Proteins of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2 or n-COV19), the Cause of COVID-19. Protein J 2020, 39, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojkova, D.; et al. Proteomics of SARS-CoV-2-infected host cells reveals therapy targets. Nature ( 2020. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.D.; et al. Characterisation of the transcriptome and proteome of SARS-CoV-2 reveals a cell passage induced in-frame deletion of the furin-like cleavage site from the spike glycoprotein. Genome Med 2020, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkel, Y.; et al. The coding capacity of SARS-CoV-2. Nature ( 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, K.K.; et al. Codon usage bias analysis of citrus tristeza virus: Higher codon adaptation to citrus reticulata host. Viruses 2019, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, E.P.C. Codon usage bias from tRNA’s point of view: Redundancy, specialization, and efficient decoding for translation optimization. Genome Research 2004, 14, 2279–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgs, P.G.; Ran, W. Coevolution of codon usage and tRNA genes leads to alternative stable states of biased codon usage. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2008, 25, 2279–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintó, R.M. , Aragonès, L., Costafreda, M.I., Ribes, E.; Bosch, A. Codon usage and replicative strategies of hepatitis A virus. Virus Research 2007, 127, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, A.M. , Soudy, M.; Mohamed, R. vhcub: Virus-host codon usage co-adaptation analysis. F1000Research 2019, 8, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A. , Al-Taher, A., Al-Nazawi, M., Al-Mubarak, A.I.; Kandeel, M. Analysis of preferred codon usage in the coronavirus N genes and their implications for genome evolution and vaccine design. Journal of Virological Methods 2020, 277, 113806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. , Sun, S., Norenburg, J.L.; Sundberg, P. Mutation and Selection Cause Codon Usage and Bias in Mitochondrial Genomes of Ribbon Worms (Nemertea). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85631. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; et al. Analysis of synonymous codon usage pattern in duck circovirus. Gene 2015, 557, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P.M.; Li, W.H. The codon Adaptation Index--a measure of directional synonymous codon usage bias, and its potential applications. Nucleic Acids Res 1987, 15, 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puigbò, P. , Bravo, I.G.; Garcia-Vallve, S. CAIcal: a combined set of tools to assess codon usage adaptation. Biology direct 2008, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. , Weon, S., Lee, S.; Kang, C. Relative codon adaptation index, a sensitive measure of codon usage bias. Evol Bioinform Online 2010, 6, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, F. The ‘effective number of codons’ used in a gene. Gene 1990, 87, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of codon usage bias in seven Epichloë species and their peramine-coding genes. Frontiers in Microbiology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H. , Chen, M.; Tang, Z. Analysis of Synonymous Codon Usage Bias in Flaviviridae Virus. BioMed Research International 2019, 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nambou, K.; Anakpa, M. Deciphering the co-adaptation of codon usage between respiratory coronaviruses and their human host uncovers candidate therapeutics for COVID-19. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2020, 85, 104471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuglsang, A. The effective number of codons for individual amino acids: some codons are more optimal than others. Gene 2003, 320, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannarozzi, G.; et al. A Role for Codon Order in Translation Dynamics. Cell 2010, 141, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabi, R. , Volvovitch Daniel, R.; Tuller, T. stAIcalc: tRNA adaptation index calculator based on species-specific weights. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingold, H.; Pilpel, Y. Determinants of translation efficiency and accuracy. Molecular Systems Biology 2011, 7, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, O.; Pilpel, Y. Differential translation efficiency of orthologous genes is involved in phenotypic divergence of yeast species. Nat Genet 2007, 39, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, P.P.; Lowe, T.M. GtRNAdb 2.0: an expanded database of transfer RNA genes identified in complete and draft genomes. Nucleic acids research 2016, 44, D184–D189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matyášek, R.; Kovařík, A. Mutation Patterns of Human SARS-CoV-2 and Bat RaTG13 Coronavirus Genomes Are Strongly Biased Towards C to U Transitions, Indicating Rapid Evolution in Their Hosts. Genes 2020, 11, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, T.T.Y.; et al. Identifying SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature ( 2020. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of 2019-nCoV-like Coronavirus from Malayan Pangolins. bioRxiv 2020.02.17.951335 ( 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. , Wu, Q.; Zhang, Z. Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak. Current Biology 2020, 30, 1346–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; et al. Protein Structure and Sequence Reanalysis of 2019-nCoV Genome Refutes Snakes as Its Intermediate Host and the Unique Similarity between Its Spike Protein Insertions and HIV-1. Journal of Proteome Research 2020, 19, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W. , Wang, W., Zhao, X., Zai, J.; Li, X. Cross-species transmission of the newly identified coronavirus 2019-nCoV. Journal of Medical Virology 2020, 92, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H. , Stratton, C.W.; Tang, Y.W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. Journal of Medical Virology 2020, 92, 401–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inquiry launched into wombat hunting by Chinese high rollers. Available online: https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/inquiry-launched-into-wombat-hunting-by-chinese-high-rollers-20190815-p52hn1.html.

- Report sparked by Chinese gamblers shooting wombats to be kept secret | 7NEWS.com.au. Available online: https://7news.com.au/news/wildlife/report-into-chinese-gamblers-shooting-wombats-in-victoria-to-be-kept-secret-c-590856.

- Wang, M.; et al. PaxDb, a database of protein abundance averages across all three domains of life. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP 2012, 11, 492–500. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; et al. Analysis of synonymous codon usage patterns in the edible fungus Volvariella volvacea. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry 2017, 64, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L. , Cui, P., Zhu, J., Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Translational selection in human: more pronounced in housekeeping genes. Biol Direct 2014, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristina, J. , Fajardo, A., Soñora, M., Moratorio, G.; Musto, H. A detailed comparative analysis of codon usage bias in Zika virus. Virus Research 2016, 223, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.M. , Nasrullah, I.; Tong, Y. Genome-Wide Analysis of Codon Usage and Influencing Factors in Chikungunya Viruses. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, N.R.; Ebel, G.D. Effects of arbovirus multi-host life cycles on dinucleotide and codon usage patterns. Viruses 2019, 11, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; et al. Selective gene expression maintains human tRNA anticodon pools during differentiation. Nat Cell Biol 2024, 26, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C.B. , Farzan, M., Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M. , Kleine-Weber, H.; Pöhlmann, S. A Multibasic Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Is Essential for Infection of Human Lung Cells. Molecular Cell 2020, 78, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. et al. A furin cleavage site was discovered in the S protein of the 2019 novel coronavirus. Chinese Journal of Bioinformatics 103–108 (2020).

- Coutard, B.; et al. The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade. Antiviral research 2020, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boni, M.F.; et al. Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Microbiology 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.Y.; et al. Attenuated SARS-CoV-2 variants with deletions at the S1/S2 junction. Emerging Microbes and Infections 2020, 9, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; et al. Characterization of an attenuated SARS-CoV-2 variant with a deletion at the S1/S2 junction of the spike protein. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polte, C.; et al. Assessing cell-specific effects of genetic variations using tRNA microarrays. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.D.; et al. Targeted sequencing reveals expanded genetic diversity of human transfer RNAs. RNA Biology 2019, 16, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.G. Enjoy the Silence: Nearly Half of Human tRNA Genes Are Silent. Bioinformatics and Biology Insights 2019, 13, 117793221986845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Miller, J., Hippen, A.A., M.; Wright, S., Morris, C.; G. Ridge, P. Human viruses have codon usage biases that match highly expressed proteins in the tissues they infect. Biomedical Genetics and Genomics 2017, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Alias, X. , Benisty, H., Schaefer, M.H.; Serrano, L. Translational adaptation of human viruses to the tissues they infect. Cell Reports 2021, 34, 108872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Alias, X. , Benisty, H., Schaefer, M.H.; Serrano, L. Translational efficiency across healthy and tumor tissues is proliferation-related. Molecular Systems Biology 2020, 16, e9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungnak, W., Huang, N., Bécavin, C., Berg, M.; Network, H.L.B. SARS-CoV-2 Entry Genes Are Most Highly Expressed in Nasal Goblet and Ciliated Cells within Human Airways. ArXiv (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sungnak, W.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nature Medicine 2020, 26, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; et al. Digestive system is a potential route of COVID-19: an analysis of single-cell coexpression pattern of key proteins in viral entry process. Gut 2020, 69, 1010–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavon-Eternod, M.; et al. tRNA over-expression in breast cancer and functional consequences. Nucleic Acids Research 2009, 37, 7268–7280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M. , Fidalgo, A., Varanda, A.S., Oliveira, C.; Santos, M.A.S. tRNA Deregulation and Its Consequences in Cancer. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2019, 25, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aharon-Hefetz, N.; et al. Manipulation of the human trna pool reveals distinct trna sets that act in cellular proliferation or cell cycle arrest. eLife 2020, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micalizzi, D.S. , Ebright, R.Y., Haber, D.A.; Maheswaran, S. Translational Regulation of Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Research 2021, 81, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; et al. GC usage of SARS-CoV-2 genes might adapt to the environment of human lung expressed genes. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 2020, 295, 1537–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; et al. A majority of m6A residues are in the last exons, allowing the potential for 3ʹ UTR regulation. Genes and Development 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; et al. m6A mRNA modifications are deposited in nascent pre-mRNA and are not required for splicing but do specify cytoplasmic turnover. Genes and Development 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; et al. METTL3 regulates viral m6A RNA modification and host cell innate immune responses during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Reports 2021, 109091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.H.C.; et al. Direct RNA Sequencing Reveals SARS-CoV-2 m6A Sites and Possible Differential DRACH Motif Methylation among Variants. Viruses 2021, 13, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, H.M.; et al. Targeting the m6A RNA modification pathway blocks SARS-CoV-2 and HCoV-OC43 replication. Genes and Development 2021, 35, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; et al. The Architecture of SARS-CoV-2 Transcriptome. Cell 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C. , Pham, P., Dedon, P.C.; Begley, T.J. Lifestyle modifications: Coordinating the tRNA epitranscriptome with codon bias to adapt translation during stress responses. Genome Biology 2018, 19, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endres, L. , Dedon, P.C.; Begley, T.J. Codon-biased translation can be regulated by wobble-base tRNA modification systems during cellular stress responses. RNA Biology 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, C.S.; Sarin, L.P. Transfer RNA modification and infection - Implications for pathogenicity and host responses. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Gene regulatory mechanisms 2018, 1861, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Y. , Nakai, M.; Yano, T. Sulfur Modifications of the Wobble U 34 in tRNAs and their Intracellular Localization in Eukaryotic Cells. Biomolecules 2017, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Pintó, R.M. , Burns, C.C.; Moratorio, G. Editorial: Codon Usage and Dinucleotide Composition of Virus Genomes: From the Virus-Host Interaction to the Development of Vaccines. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 791750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posani, E.; et al. Temporal evolution and adaptation of SARS-CoV-2 codon usage. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2022, 27, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; et al. Optimization and Deoptimization of Codons in SARS-CoV-2 and Related Implications for Vaccine Development. Advanced Science 2023, 10, 2205445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, S.E.; et al. Analysis of 3.5 million SARS-CoV-2 sequences reveals unique mutational trends with consistent nucleotide and codon frequencies. Virol J 2023, 20, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapulionis, R.; Deutscher, M.P. A channeled tRNA cycle during mammalian protein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92, 7158–7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrushenko, Z.M. , Budkevich, T.V., Shalak, V.F., Negrutskii, B.S.; El’skaya, A.V. Novel complexes of mammalian translation elongation factor eEF1A.GDP with uncharged tRNA and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Implications for tRNA channeling. Eur J Biochem 2002, 269, 4811–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannarozzi, G.; et al. A role for codon order in translation dynamics. Cell 2010, 141, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsolic, I., Carrier, A.; Esteller, M. Genetic and epigenetic defects of the RNA modification machinery in cancer. Trends Genet S0168-9525(22)00252–9 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; et al. Global analysis of tRNA and translation factor expression reveals a dynamic landscape of translational regulation in human cancers. Commun Biol 2018, 1, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezza, C. Metabolism and cancer: the future is now. Br J Cancer 2020, 122, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; et al. A tRNA modification balances carbon and nitrogen metabolism by regulating phosphate homeostasis. Elife 2019, 8, e44795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Laxman, S. tRNA wobble-uridine modifications as amino acid sensors and regulators of cellular metabolic state. Curr Genet 2020, 66, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T. , Malkin, M.G.; Huang, S. tRNA Function and Dysregulation in Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 886642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Qian, S.-B. Translational reprogramming in cellular stress response. WIREs RNA 2014, 5, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, E. Interaction of virus populations with their hosts. Virus as Populations 2020, 123–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, N.; et al. Profiling Selective Packaging of Host RNA and Viral RNA Modification in SARS-CoV-2 Viral Preparations. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; et al. Proteolytic cleavage and inactivation of the TRMT1 tRNA modification enzyme by SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Elife 2024, 12, RP90316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.-L.; Zhou, X.-L. SARS-CoV-2 main protease Nsp5 cleaves and inactivates human tRNA methyltransferase TRMT1. J Mol Cell Biol mjad024 2023, mjad024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Oliviera, A.; et al. Recognition and Cleavage of Human tRNA Methyltransferase TRMT1 by the SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. bioRxiv 2023.02.20.529306 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; et al. Dengue virus exploits the host tRNA epitranscriptome to promote viral replication. bioRxiv 2023.11.05.565734 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.J.O. , Xu, F.; Byström, A.S. Elongator—a tRNA modifying complex that promotes efficient translational decoding. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2018, 1861, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsborn, T. , Tükenmez, H., Chen, C.; Byström, A.S. Familial dysautonomia (FD) patients have reduced levels of the modified wobble nucleoside mcm5s2U in tRNA. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2014, 454, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern-Ginossar, N. , Thompson, S.R., Mathews, M.B.; Mohr, I. Translational Control in Virus-Infected Cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2019, 11, a033001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.; et al. Emerging Roles of tRNAs in RNA Virus Infections. Trends Biochem Sci 2020, 45, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, J.F.; et al. tRNA-modifying enzyme mutations induce codon-specific mistranslation and protein aggregation in yeast. RNA Biol 2021, 18, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano, L.A.; et al. Dengue virus preferentially uses human and mosquito non-optimal codons. Mol Syst Biol (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wilusz, J.E. Controlling translation via modulation of tRNA levels. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2015, 6, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Weringh, A.; et al. HIV-1 modulates the tRNA pool to improve translation efficiency. Mol Biol Evol 2011, 28, 1827–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton-Edkins, Z.A.; White, R.J. Multiple mechanisms contribute to the activation of RNA polymerase III transcription in cells transformed by papovaviruses. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 48182–48191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton-Edkins, Z.A.; et al. Epstein-Barr virus induces cellular transcription factors to allow active expression of EBER genes by RNA polymerase III. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 33871–33880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, R.B. , Feldman, L.T.; Berk, A.J. Transcription of class III genes activated by viral immediate early proteins. Science 1985, 230, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panning, B.; Smiley, J.R. Activation of RNA polymerase III transcription of human Alu elements by herpes simplex virus. Virology 1994, 202, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, A. , Rodschinka, G.; Nedialkova, D.D. High-resolution quantitative profiling of tRNA abundance and modification status in eukaryotes by mim-tRNAseq. Mol Cell 2021, 81, 1802–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, A.; Nedialkova, D.D. Experimental and computational workflow for the analysis of tRNA pools from eukaryotic cells by mim-tRNAseq. STAR Protoc 2022, 3, 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammann, G. , Berg, M., Dalwigk, J.F.; Kaiser, S.M. Pitfalls in RNA Modification Quantification Using Nucleoside Mass Spectrometry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 3121–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalric, A.; et al. Mass Spectrometry-Based Pipeline for Identifying RNA Modifications Involved in a Functional Process: Application to Cancer Cell Adaptation. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 1825–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acera Mateos, P. , Zhou, Y., Zarnack, K.; Eyras, E. Concepts and methods for transcriptome-wide prediction of chemical messenger RNA modifications with machine learning. Brief Bioinform 2023, 24, bbad163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, N.K.; et al. Direct Nanopore Sequencing of Individual Full Length tRNA Strands. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 16642–16653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerneckis, J. , Ming, G.-L., Song, H., He, C.; Shi, Y. The rise of epitranscriptomics: recent developments and future directions. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2024, 45, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; et al. Mass Spectrometry-Based Direct Sequencing of tRNAs De Novo and Quantitative Mapping of Multiple RNA Modifications. J Am Chem Soc (2024). [CrossRef]

- Marco, K.; et al. DORQ-seq: high-throughput quantification of femtomol tRNA pools by combination of cDNA hybridization and Deep sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res gkae765 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Diensthuber, G.; et al. Enhanced detection of RNA modifications and read mapping with high-accuracy nanopore RNA basecalling models. Genome Res gr.278849.123 (2024). 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, N.S.; Horner, S.M. RNA modifications go viral. PLoS Pathogens 2017, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; et al. The Emerging Role of RNA Modifications in the Regulation of Antiviral Innate Immunity. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 845625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed-Belkacem, R.; et al. Potent Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 nsp14 N7-Methyltransferase by Sulfonamide-Based Bisubstrate Analogues. J Med Chem 2022, 65, 6231–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumu, S. , Patil, A., Towns, W., Dyavaiah, M.; Begley, T.J. The gene-specific codon counting database: a genome-based catalog of one-, two-, three-, four- and five-codon combinations present in Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes. Database : the journal of biological databases and curation 2012, 2012, bas002. [Google Scholar]

- Sabi, R. , Volvovitch Daniel, R.; Tuller, T. stAIcalc: tRNA adaptation index calculator based on species-specific weights. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturn, A. , Quackenbush, J.; Trajanoski, Z. Genesis: cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics 2002, 18, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Hoon, M.J.L. , Imoto, S., Nolan, J.; Miyano, S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 1453–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, A.J. Java Treeview--extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 3246–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. , Herrmann, C.J., Simonovic, M., Szklarczyk, D.; von Mering, C. Version 4.0 of PaxDb: Protein abundance data, integrated across model organisms, tissues, and cell-lines. PROTEOMICS 2015, 15, 3163–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).