Submitted:

25 September 2024

Posted:

25 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

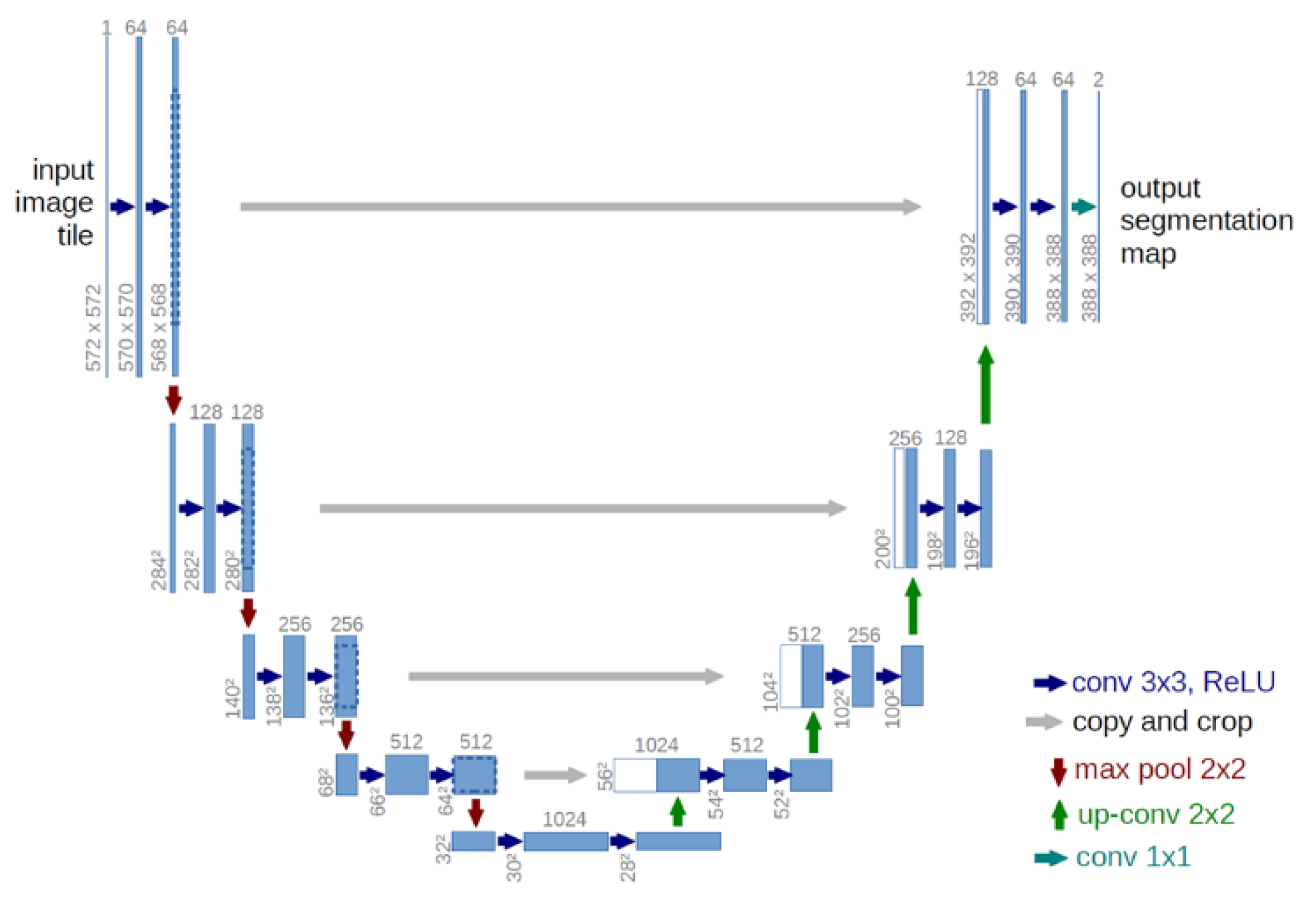

2.1. U-net

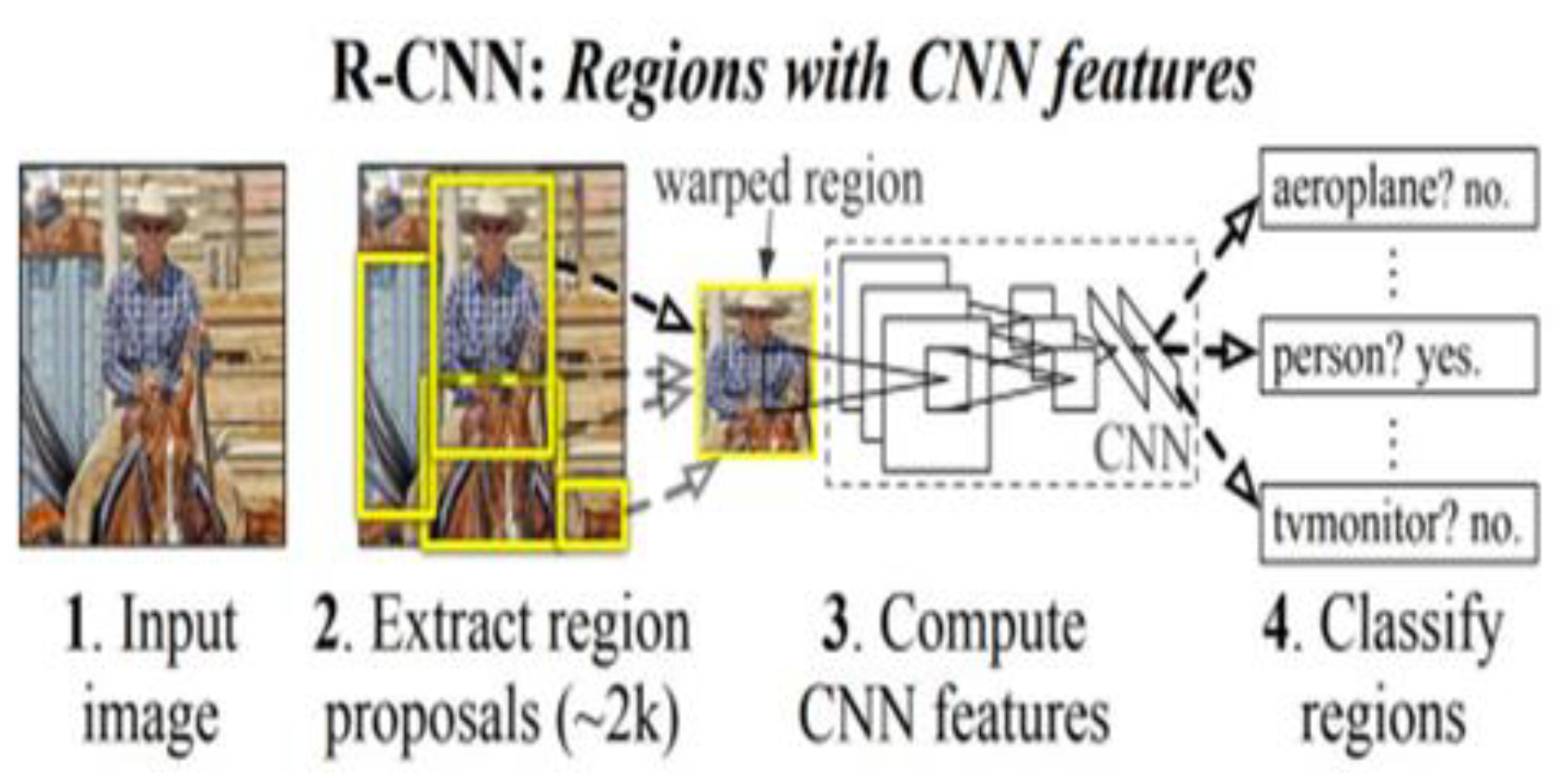

2.2. R-CNN

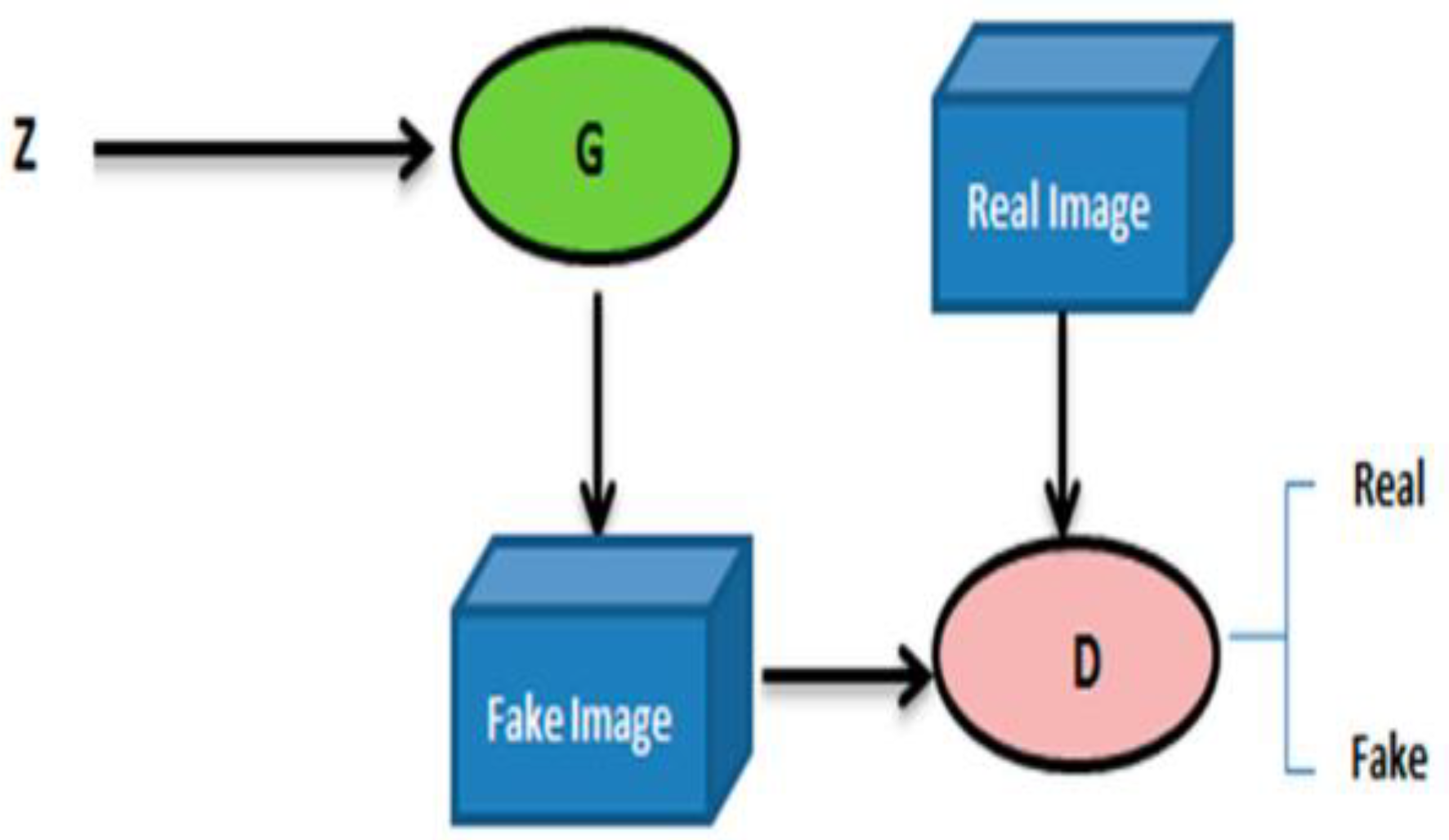

2.3. GAN

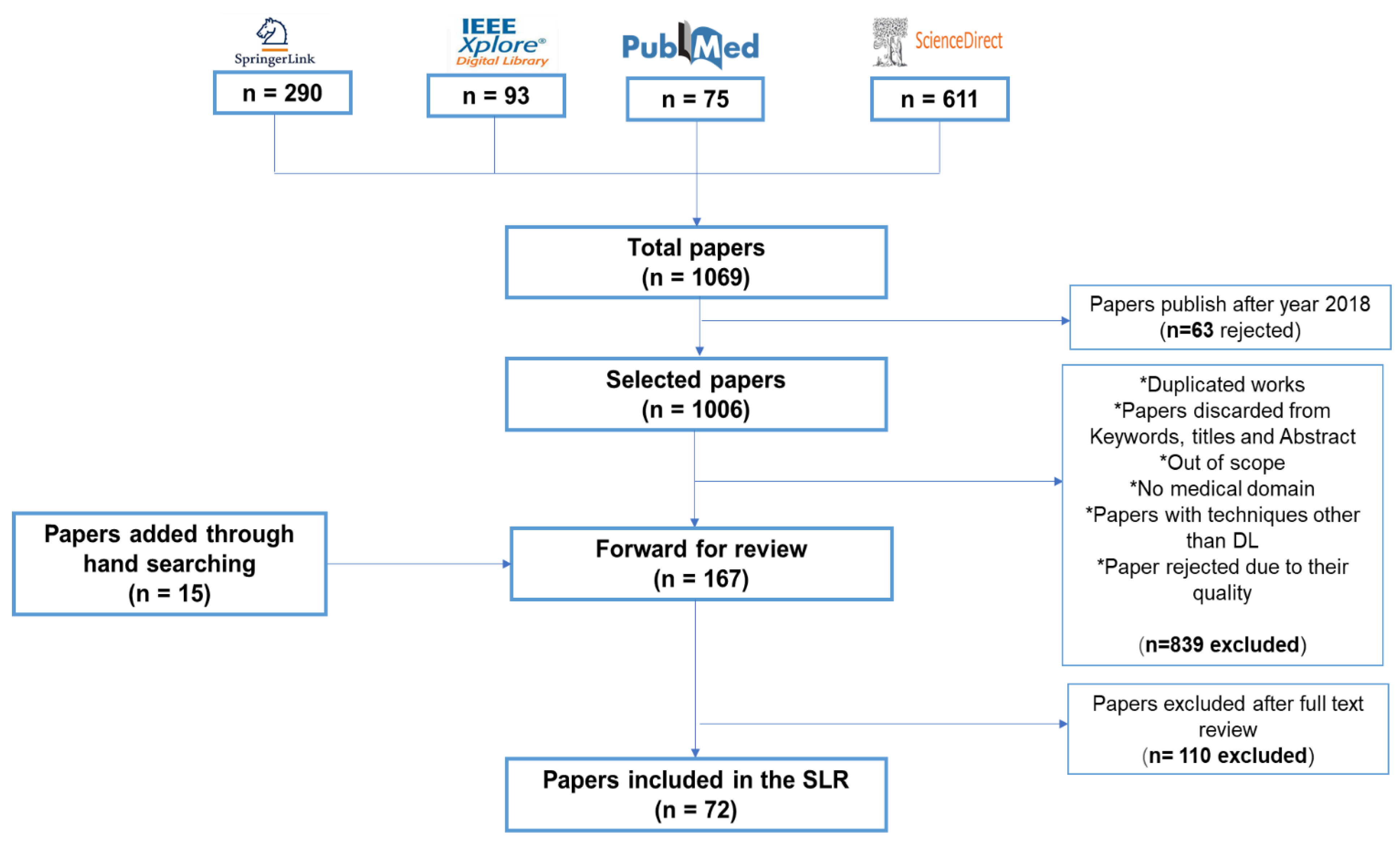

3. Methodology

- Planning the Review: This step involves specifying the requirements for the review process and forming the questions necessary for the study.

- Conducting the Review: This step includes finding relevant works and assessing the quality of the research.

- Documenting the Review: This step involves reporting the selected studies in a paper.

- Planning the Review

- Conducting the Review

- IEEEXplore--(https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/)

- Science Direct--(https://www.sciencedirect.com/)

- Springer Link--(https://link.springer.com/)

- PubMed--(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/)

4. Analysis of the Papers

4.1. RQ1 & RQ2

4.1.1. Cell Segmentation

| Reference | Publication year | Method | Task | Dataset | Instance/Semantic/Both | Code availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14] | 2018 | GAN | Cell segmentation | H1299 data set | Semantic | ✓ |

| [16] | 2023 | DNN | Cell segmentation | Phase contrast microscopy image sequence “mouse muscle progenitor cells” | Semantic | × |

| [17] | 2020 | McbUnet | Cell segmentation | 2018 Data Science Bowl dataset | Semantic | × |

| [20] | 2023 | DOLG-NeXt | Cell contour segmentation | DRIVE CVC-ClinicDB 2018 Data Science Bowl ISBI 2012 |

Semantic | × |

| [24] | 2019 | GRUU-Net | Cell segmentation | DIC-C2DH-HeLa Fluo-C2DL-MSC Fluo-N2DH-GOWT1 Fluo-N2DH-HeLa PhC-C2DH-U373 PhC-C2DL-PSC |

Semantic | × |

| [27] | 2023 | SBU-net | Cell segmentation | Mouse CD4 + T cells Pancreatic cancer cells MCF10DCIS.com cells labeled with Sir-DNA |

Semantic | × |

| [30] | 2021 | Aura-net | Cell segmentation | Microscopy image datasets from the Boston University Biomedical Image Library | Semantic | ✓ |

| [32] | 2019 | AS-UNet | Cell (nuclei) segmentation | MOD dataset BNS dataset |

Semantic | × |

| [38] | 2022 | FANet | Cell (nuclei) segmentation | Kvasir-SEG CVC-ClinicDB Dataset: 2018 Data Science Bowl ISIC 2018 Dataset DRIVE Dataset CHASE-DB1 Dataset EM Dataset |

Semantic | ✓ |

| [39] | 2018 | UNet++ | Cell (nuclei) segmentation | Microscopy images Colonoscopy videos Liver in CT scans Lung nodule |

Semantic | ✓ |

| [40] | 2023 | GeneSegNet | Cell segmentation | Real dataset of human non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Real dataset of mouse hippocampal Area CA1 (hippocampus) |

Instance | ✓ |

| [44] | 2021 | Mask RCNN and Shape-Aware Loss | Cell segmentation | DIC-C2DH-HeLa dataset PhC-C2DH-U373 dataset |

Instance | × |

| [45] | 2019 | C-LSTM with the U-Net | Cell segmentation | Fluo-N2DH-SIM DIC-C2DH-HeLa PhC-C2DH-U373x |

Instance | ✓ |

| [46] | 2019 | Attentive neural cell instance segmentation method | Cell segmentation | 644 neural cell images from a collection of timelapse microscopic videos of rat CNS stem cells | Instance | ✓ |

| [47] | 2023 | CellT-Net | Cell segmentation | LiveCELL Sartorius datasets |

Instance | × |

| [53] | 2023 | Deep learning based on cGANs | Cell segmentation | Salivary gland tumor Fallopian tube biopsy |

Instance | × |

| [54] | 2018 | SCWCSA | Cell segmentation | Dataset containing images of five cellular assays in 96-well microplates | Instance | × |

| [55] | 2019 | Box-based method | Cell segmentation | 644 images sampled from time-lapse microscopic videos of rat CNS stem cells | Instance | ✓ |

| [56] | 2023 | Residual Attention U-Net | Cell and tissue segmentation | Bright-field transmitted light microscopy images | Both | × |

| [57] | 2022 | 3DCellSeg pipeline | Cell segmentation | ATAS HMS LRP Ovules |

Both | ✓ |

| [61] | 2021 | CS-Net | Cell segmentation | EPFL dataset Kasthuri++ dataset CPM-17 |

Both | ✓ |

| [62] | 2023 | MSCA-UNet based on density regression | Cell counting | Synthetic bacterial Modified bone marrow Human subcutaneous adipose tissue |

- | × |

| [66] | 2022 | SAU-Net | Cell counting | Synthetic fluorescence microscopy Modified Bone Marrow Human subcutaneous adipose tissue Dublin Cell Counting 3D mouse blastocyst |

- | ✓ |

| [67] | 2021 | Concatenated fully convolutional regression network | Cell counting | Synthetic bacterial cells Bone marrow cells Colorectal cancer cells Human embryonic stem cells |

- | × |

4.1.2. Nucleus Segmentation

| Reference | Publication year | Method | Task | Dataset | Instance/Semantic | Code availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [70] | 2021 | NucleiSegNet | Nucleus segmentation | KMC liver Kumar dataset |

Semantic | ✓ |

| [71] | 2023 | SAC-Net | Nucleus segmentation | MoNuSeg TNBC |

Semantic | ✓ |

| [72] | 2023 | GSN-HVNET | Nucleus segmentation and classification | CoNSeP Kumar CPM-17 |

Semantic | × |

| [76] | 2023 | FRE-Net | Nucleus segmentation | TNBC MoNuSeg KMC Glas |

Semantic | ✓ |

| [77] | 2021 | Kidney-SegNet | Nucleus segmentation | Dataset of H&E images of kidney tissue TNBC Breast dataset |

Semantic | ✓ |

| [78] | 2023 | AlexSegNet | Nucleus segmentation | 2018 Data Science Bowl TNBC dataset. |

Semantic | × |

| [79] | 2022 | ASW-Net | Nucleus segmentation | BBBC039 dataset Ganglioneuroblastoma image set |

Instance | ✓ |

| [83] | 2020 | FPN with a U-net | Nucleus segmentation | 2018 Data Science Bow MoNuSeg |

Instance | ✓ |

| [84] | 2021 | Benchmark of DL architectures | Nucleus segmentation | Annotated fluorescence image dataset | Instance | ✓ |

| [85] | 2021 | VRegNet | Nucleus detection | Cardiac embryonic dataset | Instance | × |

| [86] | 2019 | RIC-Unet | Nucleus segmentation | TCGA (The Cancer Genomic Atlas) dataset | instance | × |

| [87] | 2022 | TSFD-Net | Nucleus segmentation | PanNuke dataset | Instance | ✓ |

| [88] | 2020 | NuClick | Nucleus and cell segmentation | Gland dataset Nuclei dataset Cell dataset |

Instance | ✓ |

| [89] | 2023 | BAWGNet | Nucleus segmentation | 2018 Data Science Bowl MoNuSeg TNBC |

Instance | ✓ |

| [90] | 2020 | ASPPU-Net | Nucleus segmentation | TNBC dataset TCGA |

Instance | × |

| [91] | 2022 | CNN | Nucleus detection and segmentation | 2018 Data Science Bowl MoNuSeg dataset |

Instance | ✓ |

| [92] | 2020 | cGAN | Nucleus segmentation | Annotations of 30 1000 × 1000 pathology images from seven different organs (bladder, colon, stomach, breast, kidney, liver, and prostate |

Instance | ✓ |

| [93] | 2019 | DL Strategies | Nucleus segmentation | Fluorescence Images | Instance | ✓ |

| [94] | 2019 | CIA-Net | Nucleus | MoNuSeg dataset with seven different organs | Instance | × |

| [95] | 2020 | Bending loss regularized network | Nucleus | MoNuSeg | Instance | × |

| [96] | 2020 | Instance-aware Self-supervised Learning for Nuclei Segmentation | Nucleus | MoNuSeg 2018 Dataset |

Instance | × |

| [97] | 2020 | Triple U-net | Nucleus | MoNuSeg CoNSeP CPM-17 |

Instance | × |

| [98] | 2022 | Contour Proposal Network |

Cell detection Cell segmentation | NCB - Neuronal Cell Bodies BBBC039 - Nuclei of U2OS cells BBBC041 - P. vivax (malaria) SYNTH - Synthetic shapes. |

Instance | ✓ |

4.1.3. Tissue Segmentation

4.2. RQ3

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- Cell segmentation

- Nucleus Segmentation

- Tissue Segmentation

- Integration of DL Tools

- Challenges and Future Directions

Aauthor Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kherlopian, A.R.; Song, T.; Duan, Q.; Neimark, M.A.; Po, M.J.; Gohagan, J.K.; Laine, A.F. A review of imaging techniques for systems biology, BMC Syst. Biol. 2008, 2, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, G.S.; Herrera, W.G.; Bento, M.P.; Appenzeller, S.; Rittner, L. Computational methods for corpus callosum segmentation on MRI: A systematic literature review, Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2018, 154, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Jin, L.; Chen, J.; Fang, Q.; Ablameyko, S.; Yin, Z.; Xu, Y. A survey on applications of deep learning in microscopy image analysis, Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 134, 104523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapaliuk, B.; Zaychenko, Y. Medical image segmentation methods overview, Syst. Res. Inf. Technol. (2018) 72–81. [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.U. An overview of deep learning in medical imaging, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Peng, Z.; Chen, F.; Yan, H.; Zhu, B.; Tai, Y.; Qiu, P.; Liu, C.; Song, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, L. Mutation analysis of 19 commonly used short tandem repeat loci in a Guangdong Han population, Leg. Med. 2018, 32, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, Y.; Prasath, S.; Glinskii, O.; Glinsky, V.; Huxley, V.; Palaniappan, K. Microvasculature segmentation of arterioles using deep CNN, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y.; Networks, G.A. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Song, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. A Review of Deep-Learning-Based Medical Image Segmentation Methods, Sustainability. 2021, 13, 1224. [CrossRef]

- Brereton, P.; Kitchenham, B.A.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Khalil, M. Lessons from applying the systematic literature review process within the software engineering domain, J. Syst. Softw. 2007, 80, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement, PLOS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [CrossRef]

- Arbelle, A.; Raviv, T.R. Microscopy Cell Segmentation via Adversarial Neural Networks, 2018. http://arxiv.org/abs/1709.05860 (accessed November 10, 2023). 10 November.

- Cohen, A.A.; Geva-Zatorsky, N.; Eden, E.; Frenkel-Morgenstern, M.; Issaeva, I.; Sigal, A.; Milo, R.; Cohen-Saidon, C.; Liron, Y.; Kam, Z.; Cohen, L.; Danon, T.; Perzov, N.; Alon, U. Dynamic Proteomics of Individual Cancer Cells in Response to a Drug, Science. 2008, 322, 1511–1516. [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Su, H.; Yin, Z. Phase Contrast Image Restoration by Formulating Its Imaging Principle and Reversing the Formulation With Deep Neural Networks, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2023, 42, 1068–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Ding, H.; Liu, C. Segmentation of Cell Images Based on Improved Deep Learning Approach, IEEE Access. 2020, 8, 110189–110202. [CrossRef]

- Ibtehaz, N.; Rahman, M.S. MultiResUNet : Rethinking the U-Net Architecture for Multimodal Biomedical Image Segmentation, Neural Netw. 2020, 121, 74–87. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Cheng, J.; Fu, H.; Zhou, K.; Hao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Gao, S.; Liu, J. CE-Net: Context Encoder Network for 2D Medical Image Segmentation, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2019, 38, 2281–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Fahim, M.A.I.; Islam, A.K.M.M.; Islam, S.; Shatabda, S. DOLG-NeXt: Convolutional neural network with deep orthogonal fusion of local and global features for biomedical image segmentation, Neurocomputing. 2023, 546, 126362. [CrossRef]

- Cardona, A.; Saalfeld, S.; Preibisch, S.; Schmid, B.; Cheng, A.; Pulokas, J.; Tomancak, P.; Hartenstein, V. An Integrated Micro- and Macroarchitectural Analysis of the Drosophila Brain by Computer-Assisted Serial Section Electron Microscopy, PLOS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000502. [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.; Tajkbaksh, N.; Sánchez, F.J.; Matuszewski, B.J.; Chen, H.; Yu, L.; Angermann, Q.; Romain, O.; Rustad, B.; Balasingham, I.; Pogorelov, K.; Choi, S.; Debard, Q.; Maier-Hein, L.; Speidel, S.; Stoyanov, D.; Brandao, P.; Córdova, H.; Sánchez-Montes, C.; Gurudu, S.R.; Fernández-Esparrach, G.; Dray, X.; Liang, J.; Histace, A. Comparative Validation of Polyp Detection Methods in Video Colonoscopy: Results From the MICCAI 2015 Endoscopic Vision Challenge, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2017, 36, 1231–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, J.C.; Goodman, A.; Karhohs, K.W.; Cimini, B.A.; Ackerman, J.; Haghighi, M.; Heng, C.; Becker, T.; Doan, M.; McQuin, C.; Rohban, M.; Singh, S.; Carpenter, A.E. Nucleus segmentation across imaging experiments: the 2018 Data Science Bowl, Nat. Methods. 2019, 16, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollmann, T.; Gunkel, M.; Chung, I.; Erfle, H.; Rippe, K.; Rohr, K. GRUU-Net: Integrated convolutional and gated recurrent neural network for cell segmentation, Med. Image Anal. 2019, 56, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltissen, D.; Wollmann, T.; Gunkel, M.; Chung, I.; Erfle, H.; Rippe, K.; Rohr, K. Comparison of segmentation methods for tissue microscopy images of glioblastoma cells, in: 2018 IEEE 15th Int. Symp. Biomed. Imaging ISBI 2018, 2018: pp. 396–399. [CrossRef]

- Wollmann, T.; Ivanova, J.; Gunkel, M.; Chung, I.; Erfle, H.; Rippe, K.; Rohr, K. Multi-channel Deep Transfer Learning for Nuclei Segmentation in Glioblastoma Cell Tissue Images, in: A. Maier, T.M. Deserno, H. Handels, K.H. Maier-Hein, C. Palm, T. Tolxdorff (Eds.), Bildverarb. Für Med. 2018, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2018: pp. 316–321. [CrossRef]

- Asha, S.B.; Gopakumar, G.; Subrahmanyam, G.R.K.S. Saliency and ballness driven deep learning framework for cell segmentation in bright field microscopic images, Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 118, 105704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: Redesigning Skip Connections to Exploit Multiscale Features in Image Segmentation, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2020, 39, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaurasia, A.; Culurciello, E. LinkNet: Exploiting Encoder Representations for Efficient Semantic Segmentation, in: 2017 IEEE Vis. Commun. Image Process. VCIP, 2017: pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Uhlmann, V. aura-net : robust segmentation of phase-contrast microscopy images with few annotations, (2021). http://arxiv.org/abs/2102.01389 (accessed November 15, 2023).

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; Glocker, B.; Rueckert, D. Attention U-Net: Learning Where to Look for the Pancreas, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Li, L.; Yang, D.; He, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, H. An Accurate Nuclei Segmentation Algorithm in Pathological Image Based on Deep Semantic Network, IEEE Access. 2019, 7, 110674–110686. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Verma, R.; Sharma, S.; Bhargava, S.; Vahadane, A.; Sethi, A. A Dataset and a Technique for Generalized Nuclear Segmentation for Computational Pathology, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2017, 36, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, P.; Lae, M.; Reyal, F.; Walter, T. Nuclei segmentation in histopathology images using deep neural networks, in: 2017 IEEE 14th Int. Symp. Biomed. Imaging ISBI 2017, IEEE, Melbourne, Australia, 2017: pp. 933–936. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid Scene Parsing Network, in: 2017 IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. CVPR, IEEE, Honolulu, HI, 2017: pp. 6230–6239. [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Chaurasia, A.; Kim, S.; Culurciello, E. ENet: A Deep Neural Network Architecture for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation, (2016). http://arxiv.org/abs/1606.02147 (accessed November 10, 2023).

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Handa, A.; Cipolla, R. SegNet: A Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Architecture for Robust Semantic Pixel-Wise Labelling, (2015). http://arxiv.org/abs/1505.07293 (accessed November 10, 2023).

- Tomar, N.K.; Jha, D.; Riegler, M.A.; Johansen, H.D.; Johansen, D.; Rittscher, J.; Halvorsen, P.; Ali, S. FANet: A Feedback Attention Network for Improved Biomedical Image Segmentation, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, D.; Hou, W.; Zhou, T.; Ji, Z. GeneSegNet: a deep learning framework for cell segmentation by integrating gene expression and imaging, Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 235. [CrossRef]

- C. Stringer, T. C. Stringer, T. Wang, M. Michaelos, M. Pachitariu, Cellpose: a generalist algorithm for cellular segmentation, (n.d.).

- Littman, R.; Hemminger, Z.; Foreman, R.; Arneson, D.; Zhang, G.; Gómez-Pinilla, F.; Yang, X.; Wollman, R. Joint cell segmentation and cell type annotation for spatial transcriptomics, Mol. Syst. Biol. 2021, 17, e10108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Ren, X. Cell segmentation and gene imputation for imaging-based spatial transcriptomics, (2023) 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Norouzi, N. An Effective Deep Learning Framework for Cell Segmentation in Microscopy Images, in: 2021 43rd Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. EMBC, IEEE, Mexico, 2021: pp. 3201–3204. [CrossRef]

- Arbelle, A.; Raviv, T.R. Microscopy Cell Segmentation via Convolutional LSTM Networks, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Wu, P.; Jiang, M.; Huang, Q.; Hoeppner, D.J.; Metaxas, D.N. Attentive neural cell instance segmentation, Med. Image Anal. 2019, 55, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Tan, H.; Li, W.; Yu, L.; Samuel, D. CellT-Net: A Composite Transformer Method for 2-D Cell Instance Segmentation, IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform 2023. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector, in: B. Leibe, J. Matas, N. Sebe, M. Welling (Eds.), Comput. Vis. – ECCV 2016, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016: pp. 21–37. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wen, L.; Bian, X.; Lei, Z.; Li, S.Z. Single-Shot Refinement Neural Network for Object Detection, (2018). http://arxiv.org/abs/1711.06897 (accessed November 10, 2023). 10 November.

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Law, H.; Deng, J. CornerNet: Detecting Objects as Paired Keypoints, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Vasconcelos, N. Cascade R-CNN: High Quality Object Detection and Instance Segmentation, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Tasnadi, E.; Sliz-Nagy, A.; Horvath, P. Structure preserving adversarial generation of labeled training samples for single-cell segmentation, Cell Rep. Methods. 2023, 3, 100592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kofahi, Y.; Zaltsman, A.; Graves, R.; Marshall, W.; Rusu, M. A deep learning-based algorithm for 2-D cell segmentation in microscopy images, BMC Bioinformatics. 2018, 19, 365. [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Wu, P.; Huang, Q.; Qu, H.; Liu, B.; Hoeppner, D.J.; Metaxas, D.N. Multi-scale Cell Instance Segmentation with Keypoint Graph based Bounding Boxes, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ghaznavi, A.; Rychtáriková, R.; Saberioon, M.; Štys, D. Cell segmentation from telecentric bright-field transmitted light microscopy images using a Residual Attention U-Net: A case study on HeLa line, Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 147, 105805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zhang, Q.; Han, Y.; Megason, S.; Hormoz, S.; Mosaliganti, K.R.; Lam, J.C.K.; Li, V.O.K. A novel deep learning-based 3D cell segmentation framework for future image-based disease detection, Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, L.; Refahi, Y.; Wightman, R.; Landrein, B.; Teles, J.; Huang, K.C.; Meyerowitz, E.M.; Jönsson, H. Cell size and growth regulation in the Arabidopsis thaliana apical stem cell niche, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, E8238–E8246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barro, A.V.; Stöckle, D.; Thellmann, M.; Ruiz-Duarte, P.; Bald, L.; Louveaux, M.; von Born, P.; Denninger, P.; Goh, T.; Fukaki, H.; Vermeer, J.E.M.; Maizel, A. Cytoskeleton Dynamics Are Necessary for Early Events of Lateral Root Initiation in Arabidopsis, Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 2443–2454.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofanelli, R.; Vijayan, A.; Scholz, S.; Schneitz, K. Protocol for rapid clearing and staining of fixed Arabidopsis ovules for improved imaging by confocal laser scanning microscopy, Plant Methods. 2019, 15, 120. [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Luo, Z. CS-Net: Instance-aware cellular segmentation with hierarchical dimension-decomposed convolutions and slice-attentive learning, Knowl. -Based Syst. 2021, 232, 107485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Qian, W.; Tian, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yao, Y. MSCA-UNet: Multi-Scale Convolutional Attention UNet for Automatic Cell Counting Using Density Regression, IEEE Access. 2023, 11, 85990–86001. [CrossRef]

- Kainz, P.; Urschler, M.; Schulter, S.; Wohlhart, P.; Lepetit, V. You Should Use Regression to Detect Cells, in: N. Navab, J. Hornegger, W.M. Wells, A.F. Frangi (Eds.), Med. Image Comput. Comput.-Assist. Interv. – MICCAI 2015, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2015: pp. 276–283. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.P.; Boucher, G.; Glastonbury, C.A.; Lo, H.Z.; Bengio, Y. Count-ception: Counting by Fully Convolutional Redundant Counting, in: 2017 IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. Workshop ICCVW, 2017: pp. 18–26. [CrossRef]

- Minn, K.T.; Fu, Y.C.; He, S.; Dietmann, S.; George, S.C.; Anastasio, M.A.; Morris, S.A.; Solnica-Krezel, L. High-resolution transcriptional and morphogenetic profiling of cells from micropatterned human ESC gastruloid cultures, eLife. 2020, 9, e59445. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Krupa, O.; Stein, J.; Wu, G.; Krishnamurthy, A. SAU-Net: A Unified Network for Cell Counting in 2D and 3D Microscopy Images, IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. PP (2021) 1–1. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Minn, K.T.; Solnica-Krezel, L.; Anastasio, M.A.; Li, H. Deeply-supervised density regression for automatic cell counting in microscopy images, Med. Image Anal. 2021, 68, 101892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lempitsky, V.; Zisserman, A. Learning To Count Objects in Images, in: Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. Curran Associates, Inc. 2010. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2010/hash/fe73f687e5bc5280214e0486b273a5f9-Abstract.html (accessed November 10, 2023).

- Sirinukunwattana, K.; Raza, S.E.A.; Tsang, Y.-W.; Snead, D.R.J.; Cree, I.A.; Rajpoot, N.M. Locality Sensitive Deep Learning for Detection and Classification of Nuclei in Routine Colon Cancer Histology Images, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2016, 35, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, S.; Das, D.; Alabhya, K.; Kanfade, A.; Kumar, A.; Kini, J. NucleiSegNet: Robust deep learning architecture for the nuclei segmentation of liver cancer histopathology images, Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 128, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Xie, K.; Pagnucco, M.; Song, Y. SAC-Net: Learning with weak and noisy labels in histopathology image segmentation, Med. Image Anal. 2023, 86, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Fu, C.; Tian, Y.; Song, W.; Sham, C.-W.; Lightweight, A. Multi-Task Deep Learning Framework for Nuclei Segmentation and Classification, Bioengineering. 2023, 10, 393. [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Vu, Q.D.; Raza, S.E.A.; Azam, A.; Tsang, Y.W.; Kwak, J.T.; Rajpoot, N. Hover-Net: Simultaneous segmentation and classification of nuclei in multi-tissue histology images, Med. Image Anal. 2019, 58, 101563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.E.A.; Cheung, L.; Shaban, M.; Graham, S.; Epstein, D.; Pelengaris, S.; Khan, M.; Rajpoot, N.M. Micro-Net: A unified model for segmentation of various objects in microscopy images, Med. Image Anal. 2019, 52, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, P.; Lae, M.; Reyal, F.; Walter, T. Segmentation of Nuclei in Histopathology Images by Deep Regression of the Distance Map, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2019, 38, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Wan, Y.; Chen, L. FRE-Net: Full-region enhanced network for nuclei segmentation in histopathology images, Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 43, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aatresh, A.A.; Yatgiri, R.P.; Chanchal, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Ravi, A.; Das, D.; Bs, R.; Lal, S.; Kini, J. Efficient deep learning architecture with dimension-wise pyramid pooling for nuclei segmentation of histopathology images, Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2021, 93, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singha, A.; BHOWMIK, M. AlexSegNet: an accurate nuclei segmentation deep learning model in microscopic images for diagnosis of cancer, Multimed. Tools Appl. 82 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Liu, Z.; Song, W.; Zhen, X.; Yuan, K.; Xu, F.; Lin, G.N. An Integrative Segmentation Framework for Cell Nucleus of Fluorescence Microscopy, Genes. 2022, 13, 431. [CrossRef]

- Ljosa, V.; Sokolnicki, K.L.; Carpenter, A.E. Annotated high-throughput microscopy image sets for validation, Nat. Methods. 2012, 9, 637–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromp, F.; Bozsaky, E.; Rifatbegovic, F.; Fischer, L.; Ambros, M.; Berneder, M.; Weiss, T.; Lazic, D.; Dörr, W.; Hanbury, A.; Beiske, K.; Ambros, P.F.; Ambros, I.M.; Taschner-Mandl, S. An annotated fluorescence image dataset for training nuclear segmentation methods, Sci. Data. 2020, 7, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuin, C.; Goodman, A.; Chernyshev, V.; Kamentsky, L.; Cimini, B.A.; Karhohs, K.W.; Doan, M.; Ding, L.; Rafelski, S.M.; Thirstrup, D.; Wiegraebe, W.; Singh, S.; Becker, T.; Caicedo, J.C.; Carpenter, A.E. CellProfiler 3. 0: Next-generation image processing for biology, PLOS Biol. 2018, 16, e2005970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Qu, A. A Fast and Accurate Algorithm for Nuclei Instance Segmentation in Microscopy Images, IEEE Access. 2020, 8, 158679–158689. [CrossRef]

- Kromp, F.; Fischer, L.; Bozsaky, E.; Ambros, I.M.; Dorr, W.; Beiske, K.; Ambros, P.F.; Hanbury, A.; Taschner-Mandl, S. Evaluation of Deep Learning Architectures for Complex Immunofluorescence Nuclear Image Segmentation, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2021, 40, 1934–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre-Landry, M.; Liu, Z.; Ling, S.; Bayat, M.; Wilson, D.L.; Jenkins, M.W. Nuclei Detection for 3D Microscopy With a Fully Convolutional Regression Network, IEEE Access Pract. Innov. Open Solut. 2021, 9, 60396–60408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Xie, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y. RIC-Unet: An Improved Neural Network Based on Unet for Nuclei Segmentation in Histology Images, IEEE Access. 2019, 7, 21420–21428. [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, T.; Mannan, Z.I.; Khan, A.; Azam, S.; Kim, H.; De Boer, F. TSFD-Net: Tissue specific feature distillation network for nuclei segmentation and classification, Neural Netw. 2022, 151, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Koohbanani, N.A.; Jahanifar, M.; Tajadin, N.Z.; Rajpoot, N. NuClick: A deep learning framework for interactive segmentation of microscopic images, Med. Image Anal. 2020, 65, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, T.; Fattah, S.A.; Kung, S.-Y. BAWGNet: Boundary aware wavelet guided network for the nuclei segmentation in histopathology images, Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 165, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.; Zhao, L.; Feng, H.; Li, D.; Tong, C.; Qin, Z. Robust nuclei segmentation in histopathology using ASPPU-Net and boundary refinement, Neurocomputing. 2020, 408, 144–156. [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Cheng, Z.; Zhong, H.; Qu, A.; Chen, L. A region-based convolutional network for nuclei detection and segmentation in microscopy images, Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2022, 71, 103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Borders, D.; Chen, R.J.; Mckay, G.N.; Salimian, K.J.; Baras, A.; Durr, N.J. Deep Adversarial Training for Multi-Organ Nuclei Segmentation in Histopathology Images, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2020, 39, 3257–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caicedo, J.C.; Roth, J.; Goodman, A.; Becker, T.; Karhohs, K.W.; Broisin, M.; Molnar, C.; McQuin, C.; Singh, S.; Theis, F.J.; Carpenter, A.E. Evaluation of Deep Learning Strategies for Nucleus Segmentation in Fluorescence Images, Cytometry A. 2019, 95, 952–965. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Onder, O.F.; Dou, Q.; Tsougenis, E.; Chen, H.; Heng, P.-A. CIA-Net: Robust Nuclei Instance Segmentation with Contour-aware Information Aggregation, (2019). http://arxiv.org/abs/1903.05358 (accessed November 16, 2023).

- Wang, H.; Xian, M.; Vakanski, A. Bending Loss Regularized Network for Nuclei Segmentation in Histopathology Images, in: 2020 IEEE 17th Int. Symp. Biomed. Imaging ISBI, IEEE, Iowa City, IA, USA, 2020: pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Shen, L.; Ma, K.; Zheng, Y. Instance-aware Self-supervised Learning for Nuclei Segmentation, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Yu, Z.; Yao, S.; Yan, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liang, C.; Han, C. Triple U-net: Hematoxylin-aware nuclei segmentation with progressive dense feature aggregation, Med. Image Anal. 2020, 65, 101786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upschulte, E.; Harmeling, S.; Amunts, K.; Dickscheid, T. Contour Proposal Networks for Biomedical Instance Segmentation, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Maurya, A.; Stanley, R.J.; Lama, N.; Jagannathan, S.; Saeed, D.; Swinfard, S.; Hagerty, J.R.; Stoecker, W.V. A deep learning approach to detect blood vessels in basal cell carcinoma, Skin Res. Technol. 2022, 28, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, M.; Bosco, M.; Molinaro, L.; Gambella, A.; Papotti, M.; Acharya, U.R.; Molinari, F. A hybrid deep learning approach for gland segmentation in prostate histopathological images, Artif. Intell. Med. 2021, 115, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Song, R.; Ma, Y.; Mou, L.; Liu, J.; Xie, Y.; Ma, M.; Zhao, Y. 3D vessel-like structure segmentation in medical images by an edge-reinforced network, Med. Image Anal. 2022, 82, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guo, Z.; Cao, J.; Tang, J. MDC-net: A new convolutional neural network for nucleus segmentation in histopathology images with distance maps and contour information, Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 135, 104543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, O.M.; Alnahhas, R.N.; Lugagne, J.-B.; Dunlop, M.J. DeLTA 2. 0: A deep learning pipeline for quantifying single-cell spatial and temporal dynamics, PLOS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1009797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannon, D.; Moen, E.; Schwartz, M.; Borba, E.; Kudo, T.; Greenwald, N.; Vijayakumar, V.; Chang, B.; Pao, E.; Osterman, E.; Graf, W.; Van Valen, D. DeepCell Kiosk: scaling deep learning-enabled cellular image analysis with Kubernetes, Nat. Methods. 2021, 18, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-de-Mariscal, E.; García-López-de-Haro, C.; Ouyang, W.; Donati, L.; Lundberg, E.; Unser, M.; Muñoz-Barrutia, A.; Sage, D. DeepImageJ: A user-friendly environment to run deep learning models in ImageJ, Nat. Methods. 2021, 18, 1192–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberl, M.G.; Churas, C.; Tindall, L.; Boassa, D.; Phan, S.; Bushong, E.A.; Madany, M.; Akay, R.; Deerinck, T.J.; Peltier, S.T.; Ellisman, M.H. CDeep3M—Plug-and-Play cloud-based deep learning for image segmentation, Nat. Methods. 2018, 15, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belevich, I.; Jokitalo, E. DeepMIB: User-friendly and open-source software for training of deep learning network for biological image segmentation, PLOS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1008374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Amgad, M.; Mobadersany, P.; McCormick, M.; Pollack, B.P.; Elfandy, H.; Hussein, H.; Gutman, D.A.; Cooper, L.A.D. Interactive Classification of Whole-Slide Imaging Data for Cancer Researchers, Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 1171–1177. [CrossRef]

- Waibel, D.J.E.; Boushehri, S.S.; Marr, C. InstantDL: an easy-to-use deep learning pipeline for image segmentation and classification, BMC Bioinformatics. 2021, 22, 103. [CrossRef]

- Hollandi, R.; Szkalisity, A.; Toth, T.; Tasnadi, E.; Molnar, C.; Mathe, B.; Grexa, I.; Molnar, J.; Balind, A.; Gorbe, M.; Kovacs, M.; Migh, E.; Goodman, A.; Balassa, T.; Koos, K.; Wang, W.; Caicedo, J.C.; Bara, N.; Kovacs, F.; Paavolainen, L.; Danka, T.; Kriston, A.; Carpenter, A.E.; Smith, K.; Horvath, P. nucleAIzer: A Parameter-free Deep Learning Framework for Nucleus Segmentation Using Image Style Transfer, Cell Syst. 2020, 10, 453–458.e6. [CrossRef]

- von Chamier, L.; Jukkala, J.; Spahn, C.; Lerche, M.; Hernández-Pérez, S.; Mattila, P.K.; Karinou, E.; Holden, S.; Solak, A.C.; Krull, A.; Buchholz, T.-O.; Jug, F.; Royer, L.A.; Heilemann, M.; Laine, R.F.; Jacquemet, G.; Henriques, R. ZeroCostDL4Mic: an open platform to simplify access and use of Deep-Learning in Microscopy, (2020) 2020. 03.20.00 0133. [CrossRef]

- Berg, S.; Kutra, D.; Kroeger, T.; Straehle, C.N.; Kausler, B.X.; Haubold, C.; Schiegg, M.; Ales, J.; Beier, T.; Rudy, M.; Eren, K.; Cervantes, J.I.; Xu, B.; Beuttenmueller, F.; Wolny, A.; Zhang, C.; Koethe, U.; Hamprecht, F.A.; Kreshuk, A. ilastik: interactive machine learning for (bio)image analysis, Nat. Methods. 2019, 16, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xun, D.; Chen, D.; Zhou, Y.; Lauschke, V.M.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y. Scellseg: A style-aware deep learning tool for adaptive cell instance segmentation by contrastive fine-tuning, iScience. 2022, 25, 105506. [CrossRef]

- Zargari, DeepSea: An efficient deep learning model for automated cell segmentation and tracking, (n.d.).

- Körber, N. MIA is an open-source standalone deep learning application for microscopic image analysis, Cell Rep. Methods. 2023, 3, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, T.; Mai, D.; Bensch, R.; Çiçek, Ö.; Abdulkadir, A.; Marrakchi, Y.; Böhm, A.; Deubner, J.; Jäckel, Z.; Seiwald, K.; Dovzhenko, A.; Tietz, O.; Bosco, C.D.; Walsh, S.; Saltukoglu, D.; Tay, T.L.; Prinz, M.; Palme, K.; Simons, M.; Diester, I.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. U-Net: deep learning for cell counting, detection, and morphometry, Nat. Methods. 2019, 16, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Miura, T.; Voleti, V.; Yamaguchi, K.; Tsutsumi, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Otomo, K.; Fujie, Y.; Teramoto, T.; Ishihara, T.; Aoki, K.; Nemoto, T.; Hillman, E.M.; Kimura, K.D. ; DeeCellTracker, a deep learning-based pipeline for segmenting and tracking cells in 3D time lapse images, eLife. 2021, 10, e59187. [CrossRef]

- Weigert, M.; Schmidt, U.; Haase, R.; Sugawara, K.; Myers, G. Star-convex Polyhedra for 3D Object Detection and Segmentation in Microscopy, in: 2020 IEEE Winter Conf. Appl. Comput. Vis. WACV, 2020: pp. 3655–3662. [CrossRef]

- Archit, A.; Nair, S.; Khalid, N.; Hilt, P.; Rajashekar, V.; Freitag, M.; Gupta, S.; Dengel, A.; Ahmed, S.; Pape, C. Segment Anything for Microscopy, Bioinformatics, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W.; Beuttenmueller, F.; Gómez-de-Mariscal, E.; Pape, C.; Burke, T.; Garcia-López-de-Haro, C.; Russell, C.; Moya-Sans, L.C. de-la-Torre-Gutiérrez; Schmidt, D.; Kutra, D.; Novikov, M.; Weigert, M.; Schmidt, U.; Bankhead, P.; Jacquemet, G.; Sage, D.; Henriques, R.; Muñoz-Barrutia, A.; Lundberg, E.; Jug, F. Kreshuk, A. BioImage Model Zoo: A Community-Driven Resource for Accessible Deep Learning in BioImage Analysis, 2022. [CrossRef]

| Abbreviation | Meaning | Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACC | Accuracy | H&E | Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| AJI | Aggregated Jaccard Index | IoU | Intersection over union |

| AS-UNet | U-Net with atrous depthwise separable convolution | JI | Jaccard index |

| ASPPU-Net | Atrous spatial pyramid pooling U-Net | MAE | Mean absolute error |

| ASW-Net | Attention-enhanced Simplified W-Net | McbUnet | Mixed convolution blocks |

| BAWGNet | Boundary aware wavelet guided network | MDC-Net | Multiscale connected segmentation network with distance map and contour information |

| cGAN | Conditional generative adversarial network | MoNuSeg | Multi-Organ Nuclei Segmentation |

| CIA-Net | Contour-aware Informative Aggregation Network | PCI | Phase contrast Image |

| C-LSTM | Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory | Res-UNet-H | Residual U-net for human sample |

| CPN | Contour Proposal Network | Res-UNet-R | Residual U-net for rat sample |

| CS-Net | Cellular Segmentation Network | RIC-Unet | Residual Inception-Channel attention-Unet |

| DCNN | Deep convolutional neural network | RINGS | Rapid Identification of Glandural Structures |

| DCNNs | Deep convolutional neural network | SAU-Net | Self-Attention-Unet |

| DDeep3M | Docker-powered deep learning | SAM | Segment any model |

| DeLTA | Deep Learning for Time-lapse Analysis | SBU-net | Saliency and Ballness driven U-shaped Network |

| DOLG | Deep orthogonal fusion of local and global | SCWCSA | Single-channel whole cell segmentation algorithm |

| ER-Net | Edge-reinforced neural network | SSD | Single-shot detector |

| FCRN | Fully Convolutional Regression Network | TCGA | Cancer genome atlas |

| FRE-Net | Full-region enhanced network | TSFD-Net | Tissue Specific Feature Distillation Network |

| FPN | Feature Pyramid Network | W-Net | Cascaded U-Net |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Networks | WSI | Multiresolution whole slide images |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| Reference | Publication year | Method | Task | Dataset | Instance/Semantic | Code availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [99] | 2022 | Vessel U-Net model | Blood cell vessels | HAM10000 data set NIH studies R43 CA153927-01 CA101639-02A2 |

Semantic | × |

| [100] | 2021 | RINGS | Tissue (prostate) segmentation | Dataset of 1500 H&E (hematoxylin & eosin) stained images of prostate tissue |

Semantic | × |

| [101] | 2022 | ER-Net | 3D vessel segmentation | Cerebrovascular datasets Nerve datasets |

Semantic | ✓ |

| [73] | 2019 | Hover-Net | Tissue (nucleus) segmentation and classification | CoNSeP dataset | Instance | ✓ |

| [102] | 2021 | MDC-Net | Tissue (nucleus) segmentation | DATA ORGANS DATA BREAST |

Semantic | ✓ |

| Reference | Software/tool | Microscopy image type | Website | Tool structure | Task |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [103] | DeLTA 2.0 | Time lapse microscopy data. | https://gitlab.com/dunloplab/delta https://delta.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ |

Web-based application | Cell segmentation and tracking |

| [104] | Deepcell | Fluorescence | https://deepcell.org/ https://github.com/vanvalenlab/kiosk-console |

Web-based application Wrapper script Docker Container |

Cell segmentation and tracking |

| [41] | CellPose | Fluorescence brightfield |

https://www.cellpose.org/ | Web-based application Jupyter notebook |

Cell and nucleus |

| [105] | DeepImageJ | PCI | https://deepimagej.github.io/ | ImageJ plug-in | Cell segmentation |

| [106] | CDeep3M | Light X-ray microCT electron microscopy |

https://cdeep3m-viewer.crbs.ucsd.edu/cdeep3m_result/view/6447 | Web-based application Google Colab Docker Container AWS cloud Singularity |

Cell segmentation |

| [107] | DeepMIB | 2D and 3D electron and multicolor light microscopy d | http://mib.helsinki.fi https://github.com/Ajaxels/MIB2 |

Matlab GUI | Cell |

| [108] | HistomicsML2 | WSI | https://histomicsml2.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html https://github.com/CancerDataScience/HistomicsML2 |

Docker Container | Cell/ nucleus /Tissue |

| [109] | InstantDL | Brightfeld CT scans |

https://github.com/marrlab/InstantDL | Docker Container | Cell nucleus segmentation |

| [110] | NucleAlzer | Fluorescence Histology |

www.nucleaizer.org | Web-based application | Nucleus segmentation |

| [111] | ZeroCostDL4Mic | Pseudo-fluorescence Brightfeld |

https://github.com/HenriquesLab/ZeroCostDL4Mic | Google Colab | Cell segmentation |

| [112] | Ilastik | Electron microscopy | https://github.com/ilastik | Python Script | Nucleus segmentation |

| [113] | Scellseg | Phase-contrast | https://github.com/cellimnet/scellseg-publish | GUI | Cell/Tissue segmentation |

| [114] | DeepSea | Time-lapse | https://deepseas.org/software | MATLAB software tool | Cell segmentation |

| [115] | MIA | Phase-contrast Histology |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7970965 | Python script | Image classification, object detection, semantic segmentation and tracking |

| [116] | U-Net plugin | Fluorescence DIC Phase contrast Brightfield electron microscopy |

https://lmb.informatik.uni-freiburg.de/resources/opensource/unet/ | Caffe framework AWS cloud |

Cell detection and segmentation |

| [117] | 3DeeCellTraker | 3D time lapse | https://github.com/WenChentao/3DeeCellTracker | Python script | Cell segmentation and tracking |

| [118] | Stardist | Brightfield Fluorescence |

https://github.com/mpicbg-csbd/stardist | Docker Container | Cell/ nucleus segmentation |

| [119] | SAM | Brightfield | https://github.com/computational-cell-analytics/micro-sam | Python script | Cell segmentation and tracking |

| [120] | BioImage Model Zoo | Microscopy images | https://bioimage.io/#/ | Web-based application | Livecell segmentation Cell segmentation Nucleus segmentation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).