Submitted:

24 September 2024

Posted:

25 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- ●

- Since the methods proposed here are tested on freely downloadable datasets (http://dmb.iasi.cnr.it/supbar codes.php) (split into training and test sets are available), using standard and deep learners (CNN and SVM) fed with various representations of DNA sequences, our system provides a baseline against which future researchers can compare results using ML-based taxonomic methods for classifying species using DNA barcodes;

- ●

- We offer and compare novel methods for representing DNA sequences in a way suitable for DNN training;

- ●

- We propose a method for creating ensembles by varying how the DNA sequence is represented;

- ●

- The datasets and all code developed for this project are available online at https://github.com/LorisNanni/AI-powered-Biodiversity-Assessment-Species-Classification-via-DNA-Barcoding-and-Deep-Learning .

2. Materials and Methods

1-Hot

2-Mer

2-Mer-p

2-Me-p-All

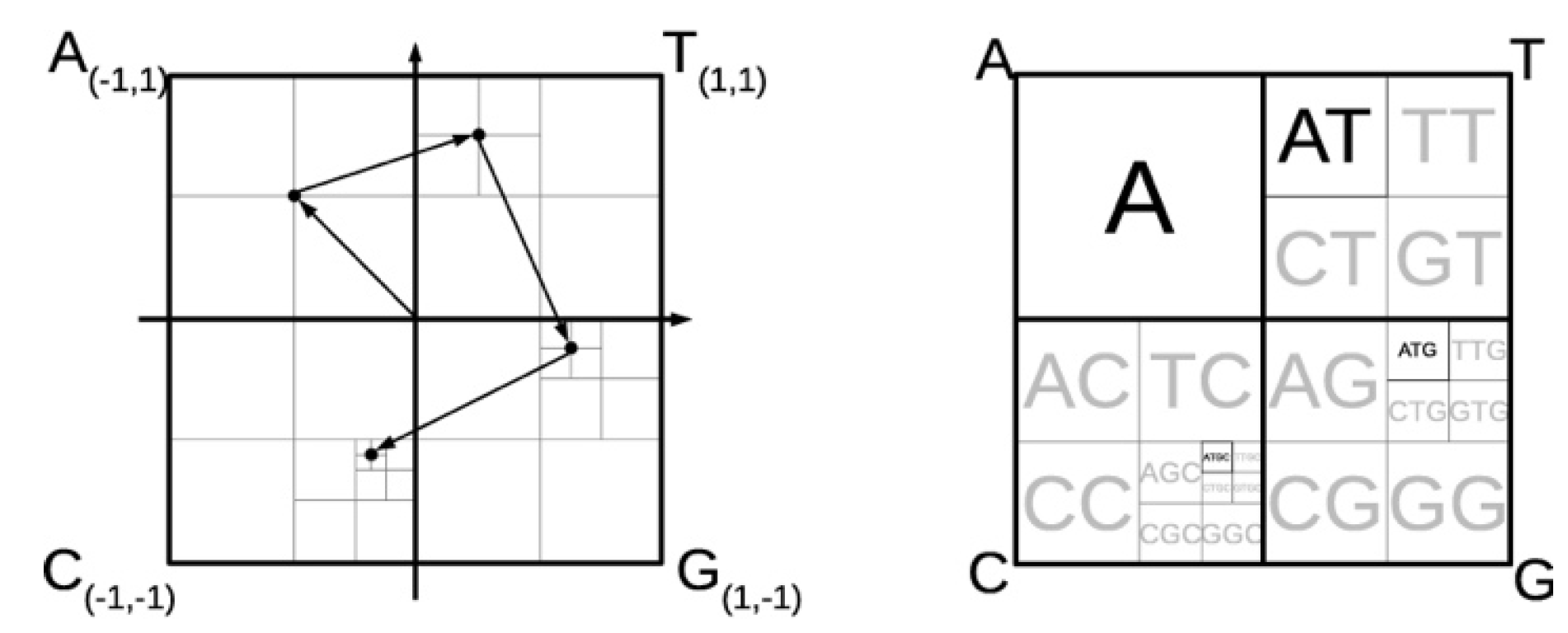

FCGR

- The nucleotide bases "A", "T", "G", and "C" correspond to each corner of the square.

- The starting nucleotide in the sequence is situated midway between the square centre and the letter-corresponding corner.

- The second nucleotide is positioned midway between the first nucleotide location and the letter-associated corner.

- Until every available space in the matrix is assigned, the process is repeated recursively.

Standardizing Sequence Length and Ensemble

- For all DNA representations, we train each network 20 times, thereby obtaining different outputs since the training data are shuffled at every epoch for each training of the net;

- For 2-Mer-p, 20 networks are trained, each using a unique physicochemical property to represent a pair of DNA bases. Overfitting is avoided by using only the first 20 properties available at http://lin-group.cn/server/iOri-PseKNC2.0/download.html i.e. no ad-hoc dataset selection is performed to propose a generic approach.

- ●

- Convolution2d(3, 16, 'Padding', 'same'). The size of the convolutional kernel/filter is 3×3. The number of filters is 16. 'Padding', 'same' means the padding is set so that the spatial dimensions of the input and output feature maps are the same.

- ●

- Batch normalization. It normalizes the output of the previous layer, thus helping with training stability and convergence.

- ●

- Dropout. This CNN introduces dropout, a regularization technique to randomly set a fraction of input units to zero during training. Dropout helps prevent overfitting, dropout rate 0.5.

- ●

- Relu. Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation layer.

- ●

- Fully connected(8). The number of neurons in this fully connected layer is 8.

- ●

- Fully connected. The number of neurons in this layer is equal to the number of classes in the classification task. This layer produces the final output scores before applying softmax.

- ●

- Softmax. The softmax activation function is applied to the output, converting the raw scores into probabilities.

- ●

- Convolution2d(5, 16, 'Padding', 'same'). The size of the convolutional kernel/filter is 5×5. The number of filters is 16. 'Padding', 'same' means the padding is set so that the spatial dimensions of the input and output feature maps are the same.

- ●

- Relu. Rectified Linear Unit activation layer.

- ●

- Convolution2d(5, 36, 'Padding', 'same'): CNN2 has another convolutional layer with size 5×5. The number of filters is 36.

- ●

- Relu: Another ReLU activation layer.

- ●

- Max pooling2d(2). This is a max pooling layer with a 2×2 pool size. Max pooling helps reduce spatial dimensions.

- ●

- Dropout(0.2) CNN2 also has a dropout layer with a dropout rate 0.2.

- ●

- Relu. Another ReLU activation layer.

- ●

- Fully connected(1024/reduce). A fully connected layer with 1024/reduce output neurons. The value of reduce is related to the dataset. We set it to '1' and increase the value if and when encountering a GPU memory problem.

- ●

- Relu. ReLU activation layer.

- ●

- Fully connectedLayer(1024/reduce). Another fully connected layer/reducer with 1024 output neurons.

- ●

- Relu. Another ReLU activation layer.

- ●

- Fully connected(1024/reduce). Yet another fully connected layer with 1024/reduce output neurons.

- ●

- Relu. Another ReLU activation layer.

- ●

- Fully connected(numClasses). A fully connected layer with the number of neurons is equal to the number of classes, as is typical of a CNN output layer.

- ●

- Softmax. The softmax activation layer normalizes the output into a probability distribution over the classes.

- ●

- flattenLayer, converts the multi-dimensional input (such as a 2D image) into a 1D vector by flattening the spatial dimensions.

- ●

- selfAttentionLayer(8, 64), a layer that applies self-attention, which allows the network to focus on different parts of the input. Parameters: Number of attention heads = 8. Size of the projection = 64.

- ●

- bilstmLayer(100), Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory layer, a recurrent layer that can process sequences in both forward and backward directions. Each BiLSTM cell has 100 hidden units.

- ●

- batchNormalizationLayer, it improves model convergence and stabilize the training process by standardizing the inputs to each layer.

- ●

- fullyConnectedLayer(numClasses), a fully connected layer that maps the output from the BiLSTM layer to the number of classes in the classification task.

- ●

- Softmax. The softmax activation layer normalizes the output into a probability distribution over the classes.

3. Datasets

Simulated Dataset

Real Datasets

4. Results

- ●

- CNN1+CNN2, the fusion by sum rule between the ensembles of CNN1 and CNN2, both trained using 2-Mer-p;

- ●

- CNN1, CNN2 and ATT, ensemble, combined by sum rule, of 20 CNN1/CNN2 or 20 ATT, coupled with 2-Mer-p;

- ●

- FCGR, the images create using FCGR used for building an ensemble, combined by sum rule, of 20 CNN1;

- ●

- X+Y, the sum between the approaches X and Y.

| Simulated | Ac | F1 |

| CNN1 | 94.53 | 94.68 |

| CNN2 | 94.48 | 94.70 |

| ATT | 94.63 | 94.73 |

| FCGR | 94.65 | 94.75 |

| CNN1+CNN2 | 94.47 | 94.68 |

| CNN1+ATT | 94.59 | 94.79 |

| CNN1+ATT+FCGR | 94.66 | 94.68 |

| CNN1 (unfiltered) | 94.94 | 95.20 |

| ATT (unfiltered) | 95.21 | 95.43 |

| CNN1+ATT (unfiltered) | 95.18 | 95.42 |

| Accuracy | CNN1+ATT unaligned data |

CNN1+ATT aligned data |

CNN1+ATT+FCGR unaligned data |

CNN1+ATT+FCGR aligned data |

[9] |

[8] |

[28] |

[23]- |

| Cypraeidae | 96.59 | 96.59 | 96.59 | 96.59 | 94.32 | 96.31 | 95.45 | 96.88 |

| Drosophila | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 | 98.28 | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 |

| Inga | 94.21 | 94.21 | 95.04 | 94.21 | 89.83 | 93.44 | 95.11 | 92.62 |

| Bats | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.71 | 99.31 | 98.61 |

| Fishes | 95.50 | 100 | 98.20 | 100 | 95.50 | 100 | 100 | 99.10 |

| Birds | 98.11 | 98.11 | 98.11 | 98.11 | 98.42 | 97.48 | 97.16 | --- |

| Average | 97.26 | 98.00 | 97.85 | 98.00 | 96.06 | 97.49 | 97.69 | --- |

| CNN1+ATT+FCGR | [9] | [8] | [28] | |

| Accuracy | 94.66 | 93.92 | 94.21 | 93.09 |

| F1-score | 94.68 | --- | 93.89 | --- |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chu, K.H.; Li, C.; Qi, J. Ribosomal RNA as molecular barcodes: a simple correlation analysis without sequence alignment. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1690–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, C.; Tittensor, D.P.; Adl, S.; Simpson, A.G.; Worm, B. How many species are there on Earth and in the ocean? PLoS biology 2011, 9, e1001127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, P.D.; Cywinska, A.; Ball, S.L.; DeWaard, J.R. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 2003, 270, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Stoeckle, M.Y.; Zemlak, T.S.; Francis, C.M. Identification of birds through DNA barcodes. PLoS biology 2004, 2, e312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaxter, M.; et al. Defining operational taxonomic units using DNA barcode data. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2005, 360, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitschek, E.; Van Velzen, R.; Felici, G.; Bertolazzi, P. BLOG 2.0: a software system for character-based species classification with DNA Barcode sequences. What it does, how to use it. Molecular ecology resources 2013, 13, 1043–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiannaca, A.; La Rosa, M.; Rizzo, R.; Urso, A. A k-mer-based barcode DNA classification methodology based on spectral representation and a neural gas network. Artificial intelligence in medicine 2015, 64, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Wu, K.-C.; Chuang, L.-Y.; Chang, H.-W. Chang. Deepbarcoding: deep learning for species classification using DNA barcoding. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 2021, 19, 2158–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitschek, E.; Fiscon, G.; Felici, G. Supervised DNA Barcodes species classification: analysis, comparisons and results. BioData mining 2014, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meher, P.K.; Sahu, T.K.; Gahoi, S.; Tomar, R.; Rao, A.R. funbarRF: DNA barcode-based fungal species prediction using multiclass Random Forest supervised learning model. BMC genetics 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohsah, G.N.; Ibrahimzada, A.R.; Ayaz, H.; Cakmak, A. Scalable classification of organisms into a taxonomy using hierarchical supervised learners. Journal of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology 2020, 18, 2050026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizaa, L.S.; et al. Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for Species Family Classification using DNA Barcode. 2023.

- Dao, F.-Y.; et al. Identify origin of replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using two-step feature selection technique. Bioinformatics 2018, 35, 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.P.; Paulay, G. DNA barcoding: error rates based on comprehensive sampling. PLoS biology 2005, 3, e422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, M.; Golding, G.B. Assigning sequences to species in the absence of large interspecific differences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2010, 56, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, K.G.; Pennington, T.D.; Cunningham, C.W. Using DNA to assess errors in tropical tree identifications: How often are ecologists wrong and when does it matter? Ecological Monographs 2010, 80, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System (http://www. barcodinglife.org. Molecular ecology notes 2007, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolazzi, P.; Felici, G.; Weitschek, E. Learning to classify species with barcodes. BMC bioinformatics 2009, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Fractal Analysis of DNA Sequences Using Frequency ChaosGame Representation and Small-Angle Scattering. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L ̈ochel, H.F.; Heider, D. Chaos game representation and its applications in bioinformatics. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2021, 19, 6263–6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffrey, H.J. Chaos game representation of gene structure. Nucleic acids research 1990, 18, 2163–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Yu, J.; Yuan, X.; Du, X. Fish Classification Using DNA Barcode Sequences through Deep Learning Method. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meher, P.K.; Sahu, T.K.; Gahoi, S.; et al. funbarRF: DNA barcode-based fungal species prediction using multiclass Random Forest supervised learning model. BMC Genet 2019, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riza, L.S.; Rahman, M.A.; Prasetyo, Y.; Zain, M.I.; Siregar, H.; Hidayat, T. Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for Species Family Classification using DNA Barcode. Knowl. Eng. Data Sci. 2023, 6, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, A.; Rigon, T.; Dunson, D.B. Inferring taxonomic placement from DNA barcoding aiding in discovery of new taxa. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2023, 14, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, P.; Wieser, C. , DNA Barcode Library of Megadiverse Lepidoptera in an Alpine Nature Park (Italy) Reveals Unexpected Species Diversity. Diversity 2023, 15, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Zhang, P.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Q. Application and Comparison of Machine Learning and Database-Based Methods in Taxonomic Classification of High-Throughput Sequencing Data. Genome Biology and Evolution 2024, 16, evae102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.; Abid, R. Efficacy and accuracy responses of DNA mini-barcodes in species identification under a supervised machine learning approach. 2021 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology (CIBCB), Melbourne, Australia, 2021, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Ne | Individual | Seq. Length | Species |

| Ne1000 | 1000 | 20 | 650 | 50 |

| Ne10000 | 10000 | 20 | 650 | 50 |

| Ne50000 | 50000 | 20 | 650 | 50 |

| Dataset | Type | Training/Test Nums | Seq. Length | Species | Gene Region | Reference |

| Cypraeidae | Invertebrates | 1656 / 352 | 614 | 211 | COI | [14] |

| Drosophila | Invertebrates | 499 / 116 | 663 | 19 | COI | [15] |

| Inga | Plants | 786 / 122 | 1838 | 63 | trnD-trnT, ITS | [16] |

| Bats | Vertebrates | 695 / 144 | 659 | 96 | COI | [17] |

| Fishes | Vertebrates | 515 / 111 | 718 | 82 | COI | [18] |

| Birds | Vertebrates | 1306 / 317 | 691 | 150 | COI | [4] |

| EUC-CNN1 | 1-Hot | 2-Mer | 2-Mer-p | 2-Me-p-All |

| Cypraeidae | 0.101 | 0.103 | 0.089 | 0.088 |

| Drosophila | 0.125 | 0.158 | 0.138 | 0.221 |

| Inga | 0.255 | 0.276 | 0.276 | 0.268 |

| Bats | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fishes | 0.123 | 0.118 | 0.135 | 0.135 |

| Birds | 0.050 | 0.043 | 0.059 | 0.057 |

| Average | 0.109 | 0.116 | 0.116 | 0.128 |

| EUC-CNN2 | 1-Hot | 2-Mer | 2-Mer-p | 2-Me-p-All |

| Cypraeidae | 0.171 | 0.113 | 0.098 | 0.104 |

| Drosophila | 0.142 | 0.138 | 0.126 | 0.130 |

| Inga | 0.208 | 0.145 | 0.139 | 0.445 |

| Bats | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fishes | 0.127 | 0.122 | 0.127 | 0.110 |

| Birds | 0.052 | 0.097 | 0.059 | 0.084 |

| Average | 0.117 | 0.103 | 0.092 | 0.146 |

| CNN2 | CNN1 | CNN1+CNN2 | ATT | CNN1 + ATT | FCGR | CNN1 + ATT + FCGR | |

| Cypraeidae | 0.098 | 0.089 | 0.085 | 0.079 | 0.080 | 0.125 | 0.091 |

| Drosophila | 0.126 | 0.138 | 0.119 | 0.130 | 0.130 | 0.223 | 0.130 |

| Inga | 0.139 | 0.276 | 0.227 | 0.215 | 0.173 | 0.281 | 0.267 |

| Bats | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fishes | 0.127 | 0.135 | 0.117 | 0.123 | 0.135 | 0 | 0 |

| Birds | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.053 | 0.030 | 0.045 | 0.119 | 0.045 |

| Average | 0.092 | 0.116 | 0.100 | 0.096 | 0.094 | 0.125 | 0.088 |

| Ac | CNN1 | CNN2 | CNN1+CNN2 | ATT | FCGR | CNN1+ATT | CNN1+ATT+FCGR |

| Cypraeidae | 96.88 | 96.31 | 96.59 | 96.31 | 96.31 | 96.59 | 96.59 |

| Drosophila | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 |

| Inga | 93.39 | 92.56 | 93.39 | 93.39 | 95.04 | 94.21 | 95.04 |

| Bats | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Fishes | 95.50 | 95.50 | 95.50 | 95.50 | 100 | 95.50 | 98.20 |

| Birds | 95.58 | 96.53 | 97.16 | 98.11 | 94.95 | 98.11 | 98.11 |

| Average | 96.74 | 96.67 | 96.96 | 97.07 | 97.57 | 97.25 | 97.85 |

| Ac | CNN1 | CNN2 | CNN1+CNN2 | ATT | FCGR | CNN1+ATT | CNN1+ATT+FCGR |

| Cypraeidae | 96.59 | 96.02 | 96.59 | 96.31 | 96.59 | 96.59 | 96.59 |

| Drosophila | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 | 99.14 |

| Inga | 95.04 | 91.74 | 92.56 | 93.39 | 95.04 | 94.21 | 94.21 |

| Bats | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Fishes | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Birds | 97.16 | 96.53 | 97.48 | 97.48 | 94.95 | 98.11 | 98.11 |

| Average | 97.98 | 97.23 | 97.62 | 97.72 | 97.62 | 98.00 | 98.00 |

| EUC | CNN1 | CNN2 | ||

| mean | std | mean | std | |

| Cypraeidae | 0.168 | 0.048 | 0.158 | 0.957 |

| Drosophila | 0.162 | 0.043 | 0.116 | 0.013 |

| Inga | 0.599 | 0.252 | 0.620 | 0.214 |

| Bats | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fishes | 0.349 | 0.446 | 0.130 | 0.047 |

| Birds | 0.796 | 0.288 | 0.343 | 0.188 |

| Average | 0.346 | 0.179 | 0.228 | 0.236 |

| Ac | CNN1 | CNN2 | ||

| mean | std | mean | std | |

| Cypraeidae | 95.71 | 0.61 | 95.67 | 0.61 |

| Drosophila | 99.05 | 0.24 | 99.14 | 0 |

| Inga | 91.98 | 2.24 | 92.27 | 1.12 |

| Bats | 99.97 | 0.16 | 99.97 | 0.16 |

| Fishes | 95.36 | 0.33 | 95.23 | 0.54 |

| Birds | 90.68 | 1.51 | 93.64 | 1.44 |

| Average | 95.45 | 0.84 | 95.98 | 0.64 |

| SVM | 1-Hot | 2-Mer | 2-Mer-p |

| Cypraeidae | 0.104 | 0.124 | 0.115 |

| Drosophila | 0.470 | 0.454 | 0.430 |

| Inga | 1.767 | 1.361 | 1.443 |

| Bats | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fishes | 0.135 | 0.144 | 0.135 |

| Birds | 0.018 | 0.179 | 0.021 |

| Average | 0.416 | 0.377 | 0.357 |

| F1 score - Aligned data | CNN1 | ATT | CNN1 + ATT | FCGR | CNN1 + ATT + FCGR |

| Cypraeidae | 98.00 | 97.82 | 98.00 | 97.93 | 98.00 |

| Drosophila | 99.75 | 99.75 | 99.75 | 99.75 | 99.75 |

| Inga | 95.35 | 95.36 | 94.69 | 95.80 | 95.35 |

| Bats | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Fishes | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Birds | 97.94 | 98.67 | 98.99 | 97.49 | 98.99 |

| Average | 98.50 | 98.60 | 98.57 | 98.49 | 98.68 |

| F1 score - unaligned data |

CNN1 | ATT | CNN1 + ATT | FCGR | CNN1 + ATT + FCGR |

| Cypraeidae | 98.36 | 97.82 | 98.00 | 98.12 | 98.00 |

| Drosophila | 99.75 | 99.75 | 99.75 | 99.75 | 99.75 |

| Inga | 94.04 | 94.21 | 94.69 | 96.08 | 95.80 |

| Bats | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Fishes | 96.08 | 96.54 | 96.08 | 100 | 99.35 |

| Birds | 96.94 | 99.11 | 99.11 | 97.34 | 99.11 |

| Average | 97.52 | 97.90 | 97.93 | 98.55 | 98.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).