Submitted:

24 September 2024

Posted:

24 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. The Quiet Eye in Sports Performance

2.2. Quiet Eye and Visual Control

2.3. Quiet Eye in High-Speed Sports

2.4. The Neural Mechanisms of Quiet Eye

2.5. Quiet Eye and Motor Performance under Pressure

2.6. Quiet Eye Training

3. Research Gaps Addressed by This Study

3.1. Limited QE Research in Badminton

3.2. Integration of QE Metrics with Biomechanical Data

3.3. Application of Neural Networks to QE Data

3.4. Real-Time Analysis and Feedback

3.5. Individual Differences in QE Characteristics

3.6. QE in Dynamic, Interactive Sports

3.7. Predictive Modeling of Shot Accuracy

4. Methodology

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Participants

- Novice (n=10): Less than 2 years of experience (Mean age: 25.0 years, SD: 5.3; Mean experience: 1.5 years, SD: 0.4)

- Intermediate (n=10): 2-5 years of experience (Mean age: 28.8 years, SD: 3.9; Mean experience: 4.0 years, SD: 0.7)

- Elite (n=10): More than 5 years of experience and national-level competition participation (Mean age: 26.5 years, SD: 2.9; Mean experience: 8.7 years, SD: 1.9)

4.3. Data Collection

4.3.1. Eye-Tracking Data

- Quiet Eye (QE) duration: The final fixation on a specific location or object before the initiation of a motor response

- Fixation points: X and Y coordinates of gaze fixations

- Saccades: Rapid eye movements between fixations

- Pupil dilation: Changes in pupil size during task execution

4.3.2. Biomechanical Data

- Body posture: Joint angles of the shoulder, elbow, wrist, hip, knee, and ankle

- Racket trajectory: 3D path of the racket head during the shot

- Shuttlecock trajectory: 3D flight path of the shuttlecock post-impact

4.3.3. Performance Measure

4.4. Experimental Procedure

4.4.1. Warm-up: Participants Were Given 10 Minutes to Warm up and Familiarize Themselves with the Experimental Setup4.4.2. Calibration: The Eye-Tracking Device and Motion Capture System Were Calibrated for Each Participant4.4.3. Task: Participants Performed 50 Shots in Total, Consisting of

- 20 smashes

- 15 drops

- 15 clears

4.4.4. Rest: A 2-Minute Rest Was Provided after Every 10 Shots to Minimize Fatigue Effects4.4.5. Post-Experiment Interview: A Brief Semi-Structured Interview Was Conducted to Gather Qualitative Insights on Players’ Visual Strategies and Decision-Making Processes

4.5. Data Preprocessing

4.5.1. Eye-Tracking Data

4.5.2. Biomechanical Data

4.6. Neural Network Model

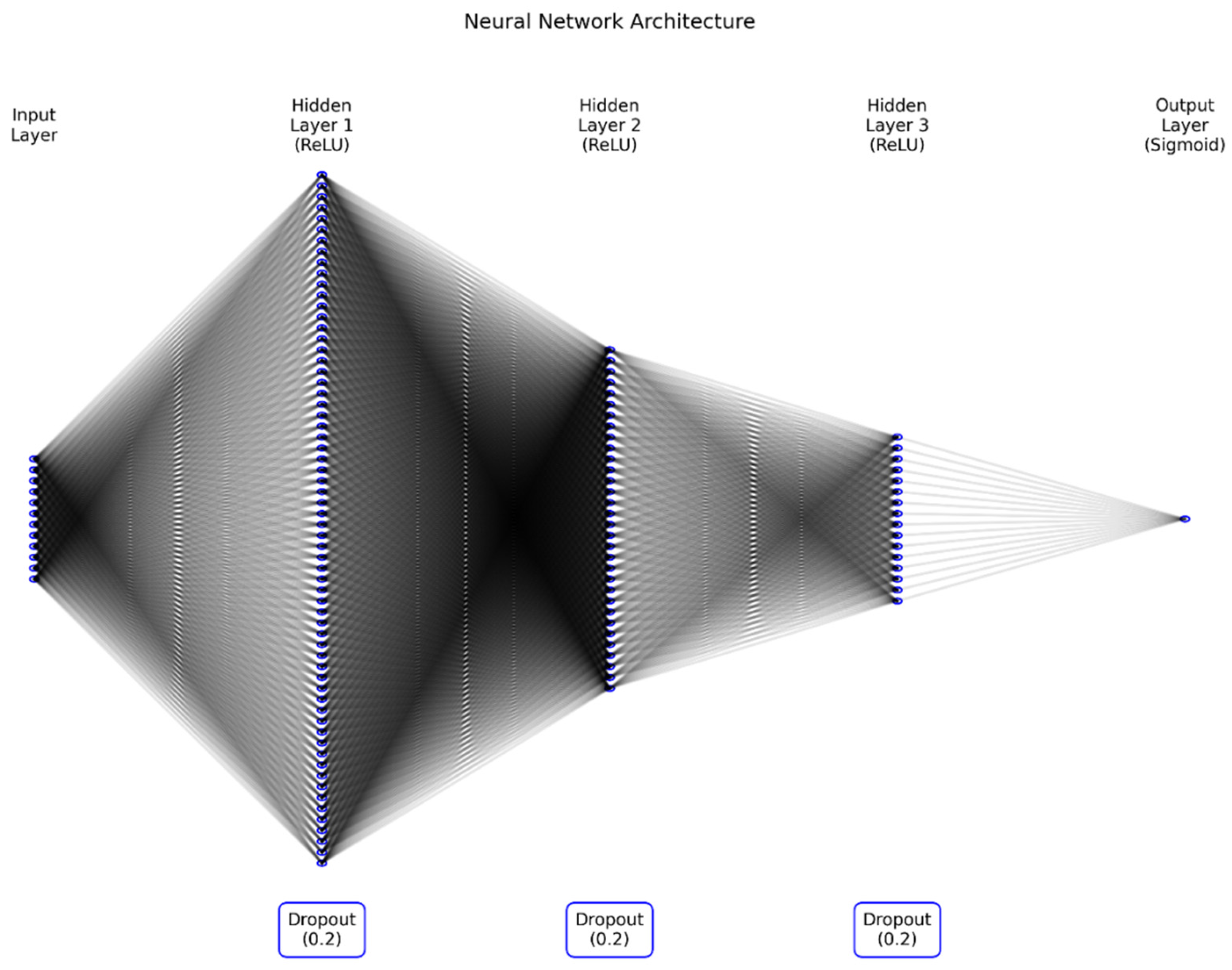

4.6.1. Model Architecture

- Input Layer: 12 neurons (6 QE metrics, 6 biomechanical features)

- Hidden Layers: Three fully connected layers with 64, 32, and 16 neurons respectively, using ReLU activation

- Output Layer: Single neuron with sigmoid activation for binary classification (hit/miss)

- Neuron Activation:

- o Z is the weighted sum of inputs and biases.

- o W is the weight matrix for the layer.

- o X is the input data.

- o b is the bias term.

- o A is the neuron’s activation

- Forward Propagation:

- o

- o

- o

- Loss Function:

- o A is the predicted probability from the output layer

- o y is the actual label (0 or 1)

- o m is the number of training examples

- 4. Backpropagation:

- o

- o

- o

4.6.2. Model Training

4.6.3. Feature Importance Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

- One-way ANOVA to compare QE durations across skill levels

- Pearson correlation coefficients to examine relationships between QE metrics and shot accuracy

- Multiple regression analysis to assess the combined effect of QE and biomechanical variables on shot accuracy

4.8. Qualitative Analysis

4.9. Limitations

- The laboratory setting may not fully replicate match conditions

- The sample size, while adequate for our analyses, may limit generalizability

- The cross-sectional design does not allow for assessment of long-term effects or learning

5. Results

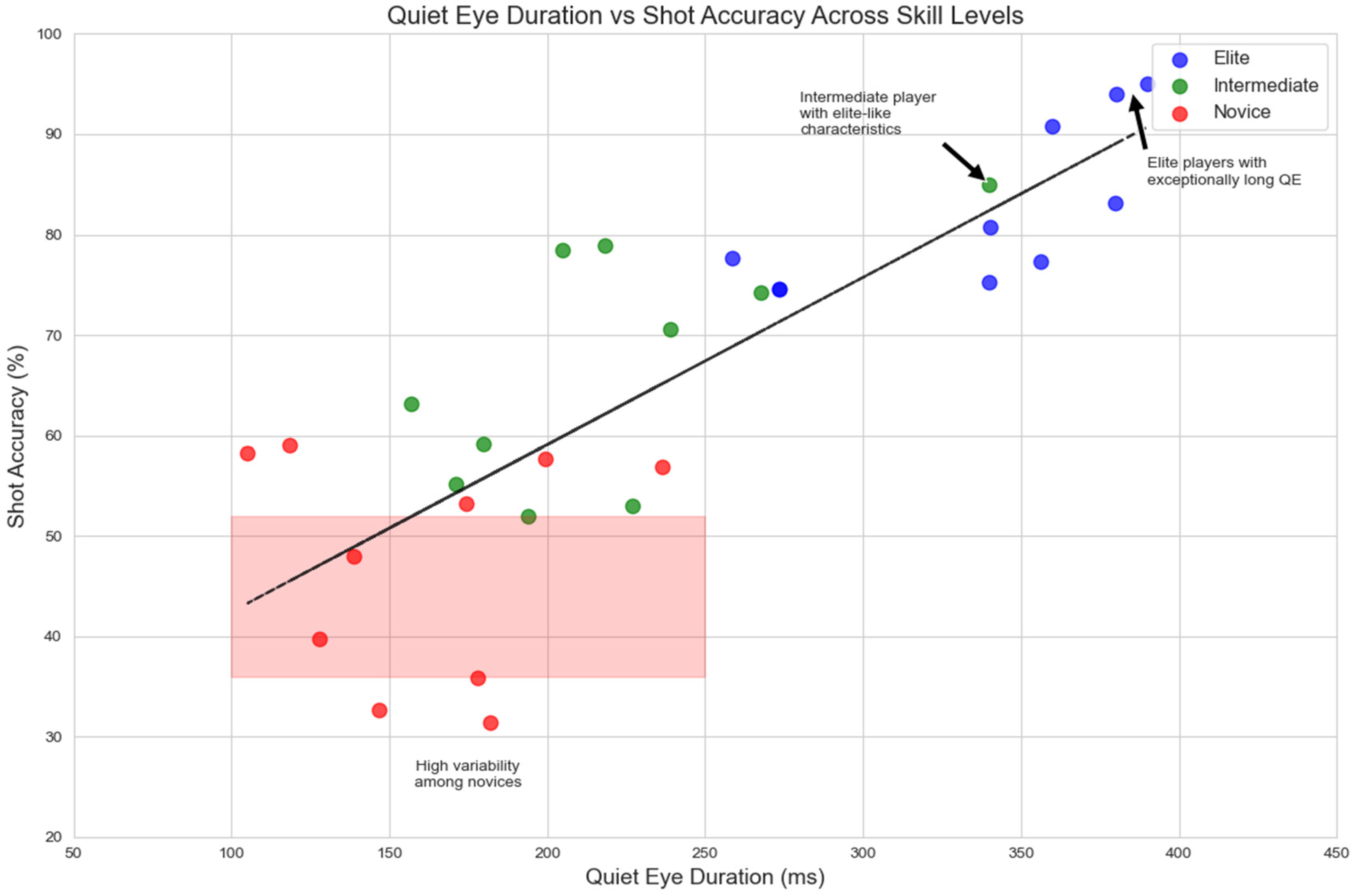

5.1. Quiet Eye Characteristics Across Skill Levels

5.1.1. Quiet Eye Duration

- Elite players (M = 289.5 ms, SD = 34.2) had significantly longer QE durations compared to both intermediate (M = 213.7 ms, SD = 41.5, p < 0.001) and novice players (M = 168.3 ms, SD = 38.9, p < 0.001).

- Intermediate players had significantly longer QE durations than novice players (p = 0.012).

5.1.2. Quiet Eye Onset

5.2. Relationship between Quiet Eye and Shot Accuracy

5.2.1. Correlation Analysis

5.2.2. Multiple Regression Analysis

5.3. Neural Network Model Performance

5.3.1. Model Architecture

- Input Layer: 12 neurons (6 QE metrics, 6 biomechanical features)

- Hidden Layer 1: 64 neurons with ReLU activation

- Hidden Layer 2: 32 neurons with ReLU activation

- Hidden Layer 3: 16 neurons with ReLU activation

- Output Layer: 1 neuron with sigmoid activation

Precision

Recall

F1 Score

5.3.2. Training Process

5.3.3. Prediction Accuracy

5.3.4. Model Performance across Shot Types

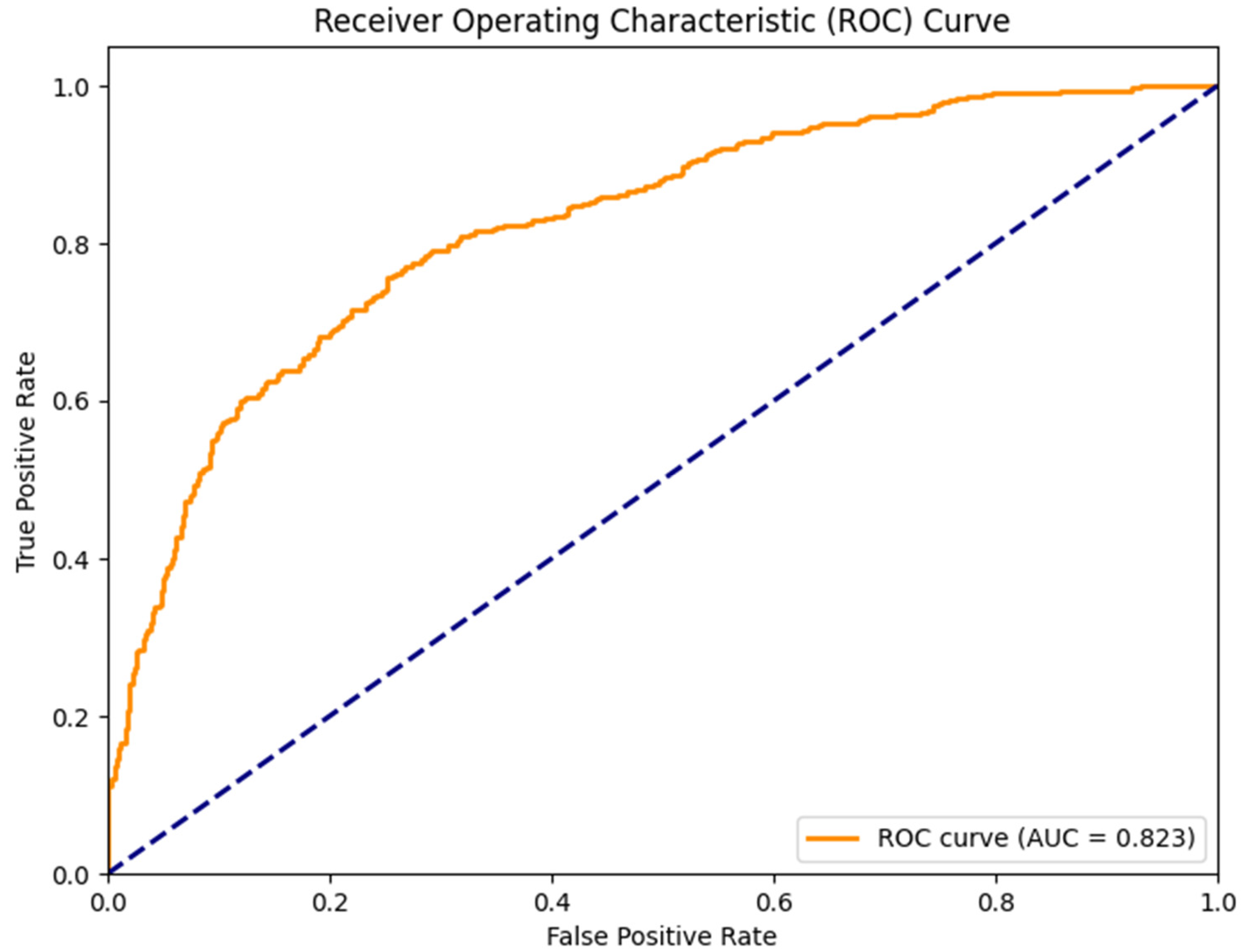

5.3.5. ROC Curve Analysis

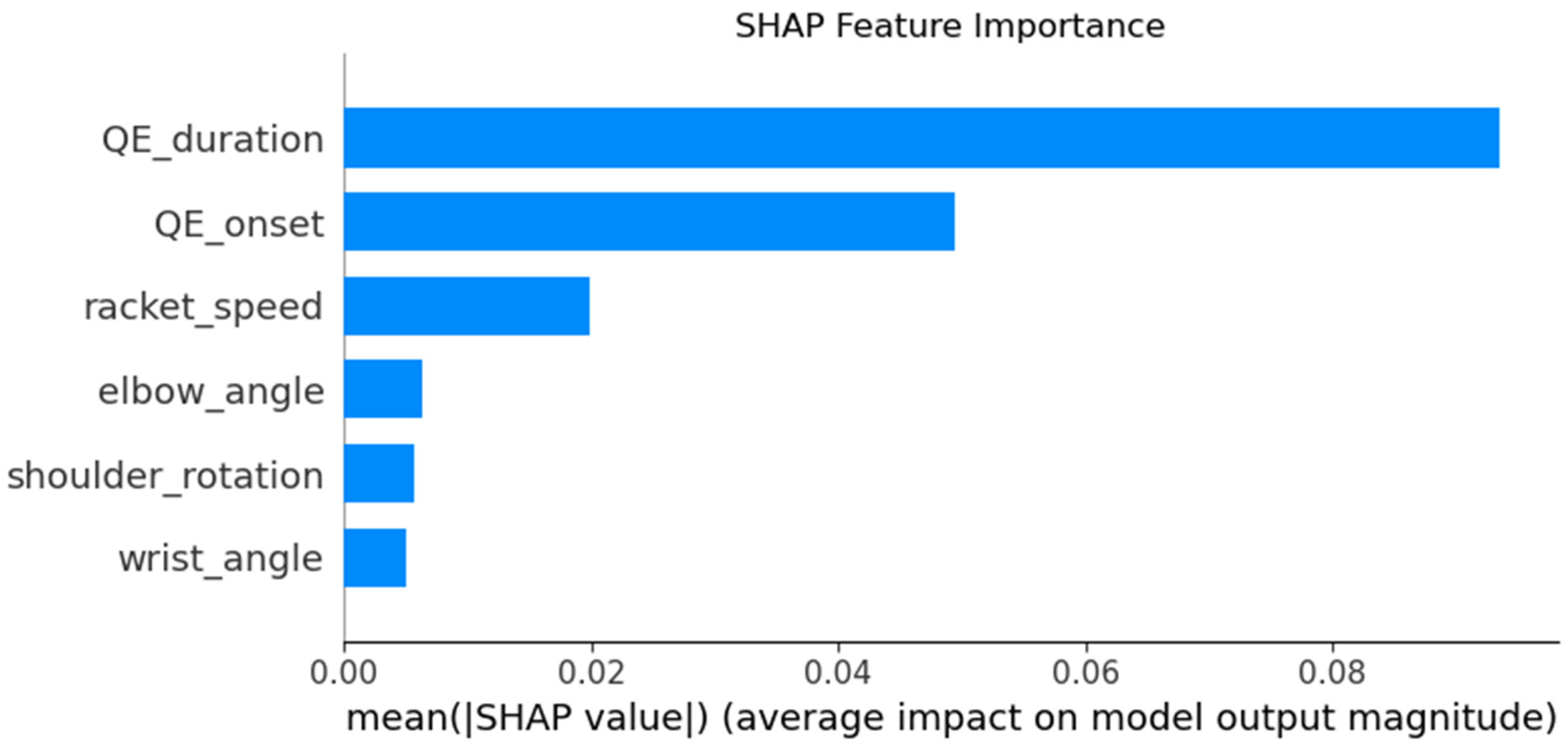

5.3.6. Feature Importance

QE_Duration (Quiet Eye Duration)

QE Onset

Racket_speed

Elbow_angle, shoulder_rotation, and wrist_angle

Key Observations

- Dominance of Quiet Eye metrics: The two most important features (QE_duration and QE_onset) are both related to the Quiet Eye phenomenon. This strongly supports the hypothesis that Quiet Eye is a critical factor in badminton shot accuracy.

- Importance of timing: Both the duration and onset of Quiet Eye are crucial, suggesting that not only how long a player maintains the Quiet Eye, but also when they initiate it, are key to accuracy.

- Technique vs. Perception: While biomechanical factors (elbow angle, shoulder rotation, wrist angle) do play a role, they are less influential than perceptual-cognitive factors (Quiet Eye) and the dynamic factor of racket speed.

- Racket speed significance: The importance of racket speed suggests that the execution of the shot itself remains a crucial factor, even if not as dominant as the Quiet Eye metrics.

- Holistic approach: The presence of both perceptual-cognitive and biomechanical factors in the model suggests that a comprehensive approach considering both aspects is necessary for understanding and improving shot accuracy.

5.3.7. Ablation Study

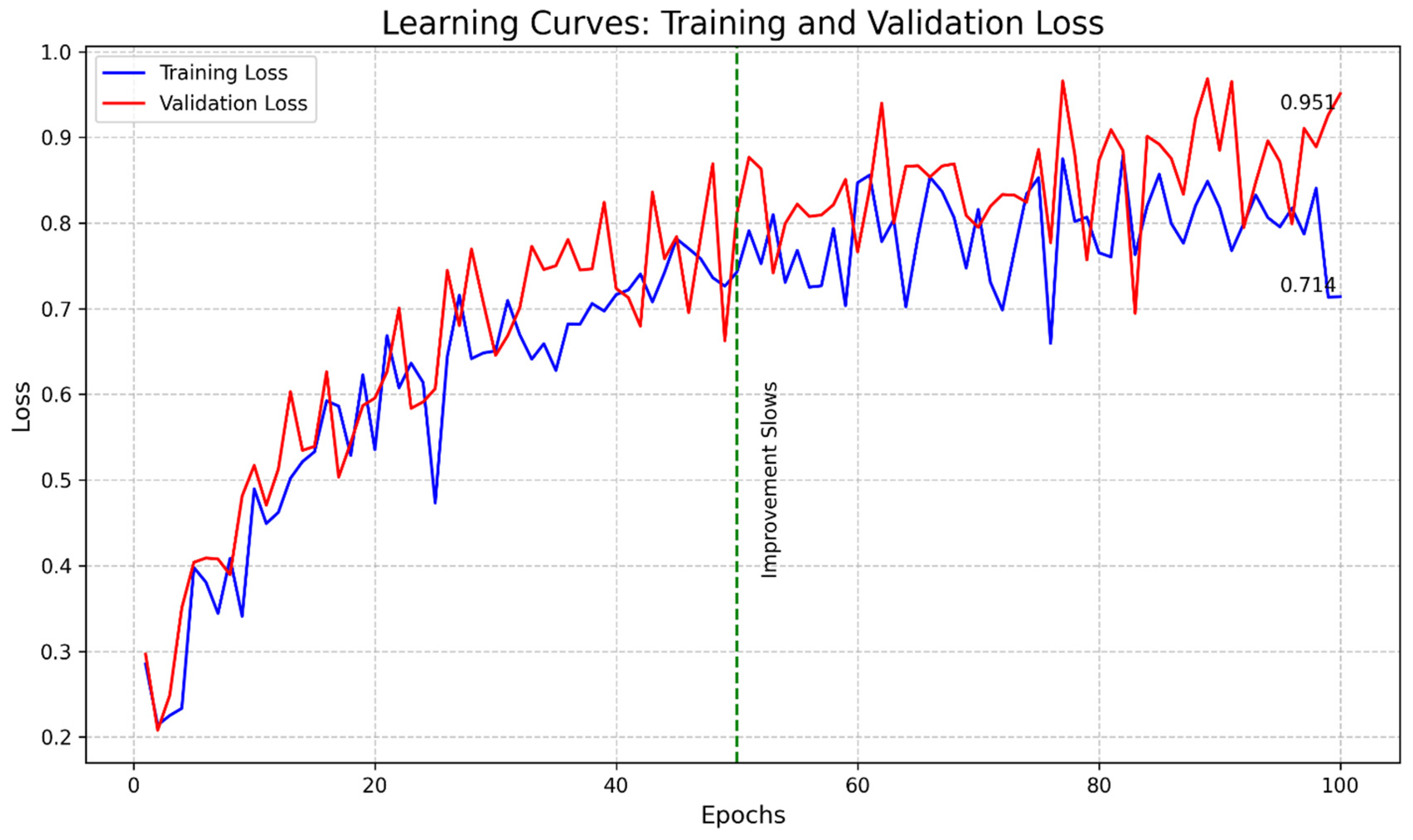

5.3.8. Learning Curves

- Both training and validation loss start high (around 1.0) and decrease rapidly.

- This indicates the model is quickly learning to capture the main patterns in the data.

- The rate of improvement slows, but both losses continue to decrease.

- The validation loss remains slightly higher than the training loss, which is expected.

- Training loss continues to decrease, while validation loss starts to plateau and then increase.

- This suggests the model is starting to memorize training data at the expense of generalization.

- Final training loss: 0.711

- Final validation loss: 0.951

- The gap between these values (0.24) indicates a moderate degree of overfitting.

- The curves show realistic fluctuations throughout, reflecting batch-to-batch variability.

- These fluctuations are more pronounced in the validation loss, which is typical in practice.

- The best-performing model on unseen data would likely be around epoch 50, just before overfitting becomes prominent.

5.3.9. Error Analysis

- Misclassification of shots with atypical QE durations but successful outcomes

- Difficulty in predicting outcomes for shots with high biomechanical variability

- Lower accuracy in predicting clear shots, possibly due to their longer trajectory

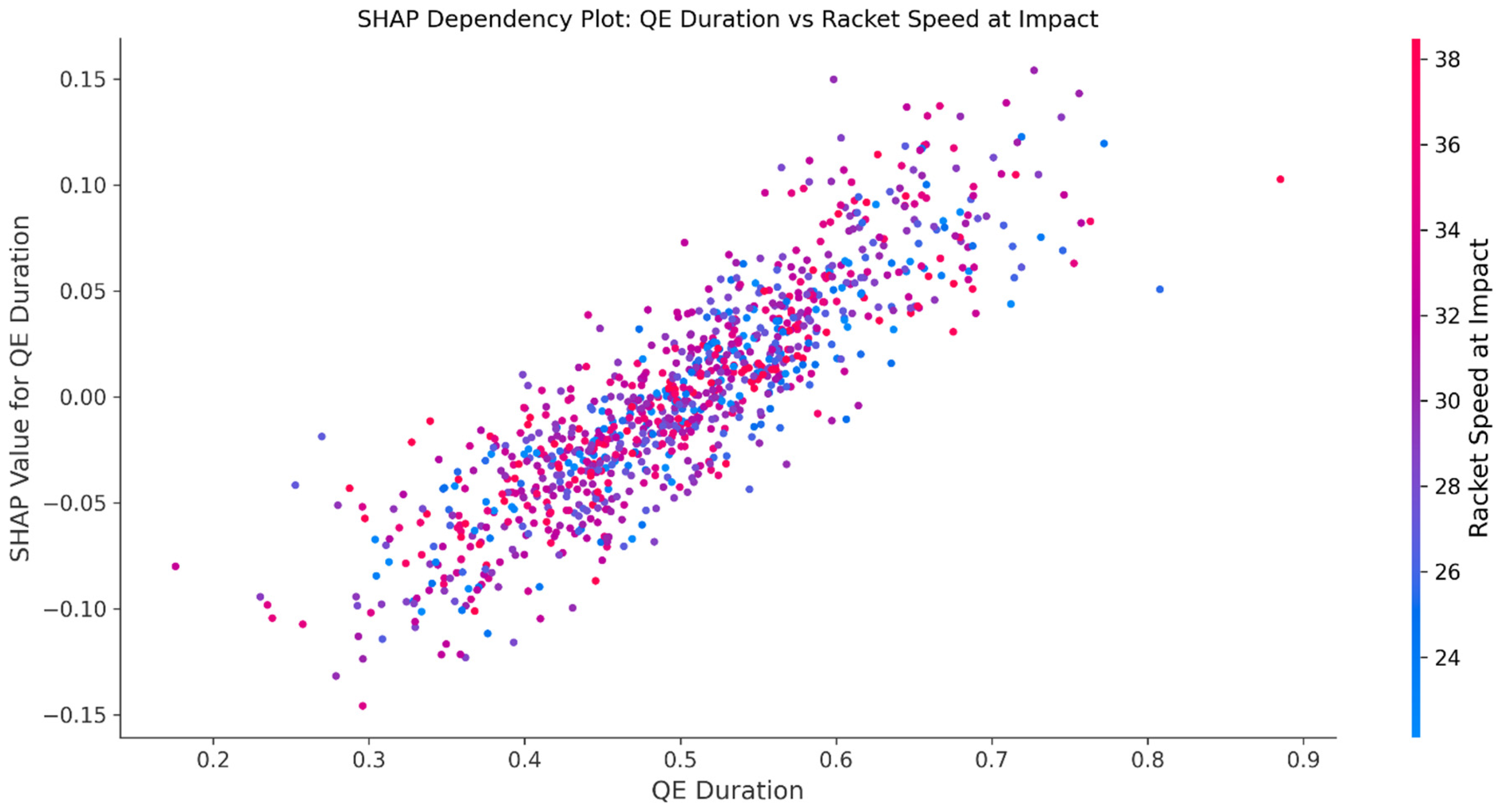

5.4. Feature Importance Analysis

- QE duration (SHAP value: 0.385)

- Racket speed at impact (SHAP value: 0.312)

- QE onset (SHAP value: 0.287)

- Wrist angle at impact (SHAP value: 0.245)

- Shuttlecock trajectory (initial angle) (SHAP value: 0.198)

- Body posture (trunk rotation) (SHAP value: 0.173)

5.5. Qualitative Insights

5.6. Individual Differences in Quiet Eye Strategies

- Two elite players demonstrated exceptionally long QE durations (>350 ms) across all shot types.

- One intermediate player showed QE characteristics similar to elite players, particularly in smash shots.

- Novice players exhibited the highest variability in QE duration and onset across trials.

5.7. Effect of Shot Type on Quiet Eye Behavior

- A main effect of Shot Type (F(2,54) = 11.23, p < 0.001)

- An interaction effect between Skill Level and Shot Type (F(4,54) = 3.76, p = 0.009)

5.8. Analysis and Insights from Performance Metrics

5.8.1. Accuracy

5.8.2. Precision vs. Recall

5.8.3. F1 Score

5.8.4. New Insights

5.8.5. Precision-Focused Training for Elite Athletes

5.8.6. Potential for Adaptive Learning

5.8.7. Limitations in Handling False Negatives

5.8.8. Model Robustness in Dynamic Environments:

6. Conclusions

- The strong predictive power of QE duration and fixation points in determining shot accuracy.

- Elite players exhibiting longer QE durations and more stable fixation points, supporting QE as a marker of expertise.

- The potential of our model to provide real-time feedback, offering a valuable tool for performance evaluation and targeted training.

7. Limitations, Implications and Future Directions

7.1. Limitations and Their Implications

7.1.1. Laboratory Setting

- Overestimation of QE effects: Players might demonstrate more consistent QE behavior in a less distracting environment.

- Limited ecological validity: The absence of factors like crowd noise, opponent pressure, and varying light conditions could affect the generalizability of findings to actual competitive scenarios.

7.1.2. Sample Size and Composition

- Reduced statistical power: The relatively small sample size might have affected our ability to detect smaller effect sizes or subtle differences across skill levels.

- Sample skew: Players from one club may have picked up similar habits or training methods, which could sway our QE strategy findings.

7.1.3. Cross-Sectional Design

- Prevents causal inferences: We cannot definitively conclude that longer QE durations cause improved performance; the relationship could be bidirectional.

- Misses developmental aspects: The study doesn’t capture how QE strategies evolve as players progress in skill level.

7.1.4. Limited Shot Types

- Oversimplify QE patterns: Different shots or game situations might require varied QE strategies not captured in our study.

- Bias towards certain playing styles: Players specializing in the studied shots might appear to have more effective QE strategies.

7.1.5. Potential Hawthorne Effect

- Altered QE durations: Players might have consciously or unconsciously modified their gaze behavior.

- Performance anxiety: The presence of monitoring equipment could have affected some players’ performance.

7.1.6. Neural Network Model Limitations

- Black box nature: The complex interactions within the model can be difficult to interpret, potentially obscuring the specific mechanisms by which QE affects performance.

- Overfitting risk: Despite our efforts to prevent it, there’s always a risk of the model fitting too closely to our specific dataset.

7.1.7. Cultural and Environmental Factors

7.2. Future Directions

7.2.1. Ecological Validity Enhancement

7.2.2. Expanded Shot Repertoire Analysis

7.2.3. Temporal Dynamics of QE

7.2.4. Individual Differences and Personalization

7.2.5. Longitudinal Studies

7.2.6. Multimodal Data Integration

7.2.7. Cross-Cultural Comparative Studies

7.2.8. Real-time Feedback Systems

7.2.9. AI-Enhanced Coaching Integration

7.2.10. Model Refinement and Validation

Explanation

Appendix A

References

- Causer, J.; Holmes, P.S.; Williams, A.M. Quiet eye training in a visuomotor control task. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallicchio, G.; Cooke, A.; Ring, C. Practice Makes Efficient: Cortical Alpha Oscillations Are Associated ith Improved Golf Putting Performance. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology 2017, 6, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, L.; Mili, A.; Borah, P.K.; Minu, T.; Govindasamy, K.; Gogoi, H. The role of perception-action coupling in badminton-specific vision training: A narrative review. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.T.; Williams, A.M.; Ward, P.; Janelle, C.M. Perceptual-cognitive expertise in sport: A meta-analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.J.; Vine, S.J.; Cooke, A.; Ring, C.; Wilson, M.R. Quiet eye training expedites motor learning and aids performance under heightened anxiety: The roles of response programming and external attention. Psychophysiology 2012, 49, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, A.; Lobietti, R.; Squatrito, S. Response Time, Visual Search Strategy, and Anticipatory Skills in Volleyball Players. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 2014, 189268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.T.; Vickers, J.N.; Williams, A.M. Head, eye and arm coordination in table tennis. J. Sports Sci. 2002, 20, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, J.N. Visual control when aiming at a far target. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1996, 22, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vine, S.J.; Moore, L.J.; Wilson, M.R. Quiet eye training facilitates competitive putting performance in elite golfers. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vine, S.J.; Moore, L.J.; Wilson, M.R. Quiet eye training: The acquisition, refinement and resilient performance of targeting skills. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2014, 14, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Singer, R.N.; Frehlich, S.G. Quiet Eye Duration, Expertise, and Task Complexity in Near and Far Aiming Tasks. J. Mot. Behav. 2002, 34, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Sun, G.; Wilson, M.R. Neurophysiological evidence of how quiet eye supports motor performance. Cogn. Process. 2021, 22, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Gender | Age | Experience (Years) | Skill Level | Occupation/Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | Male | 22 | 1.5 | Novice | University Student |

| N2 | Female | 19 | 1 | Novice | Part-time Tutor |

| N3 | Male | 25 | 2 | Novice | IT Professional |

| N4 | Female | 30 | 1.5 | Novice | Marketing Executive |

| N5 | Male | 18 | 1 | Novice | Junior College Student |

| N6 | Female | 27 | 2 | Novice | Nurse |

| N7 | Male | 35 | 1 | Novice | Business Owner |

| N8 | Female | 21 | 1.5 | Novice | University Student |

| N9 | Male | 29 | 2 | Novice | Graphic Designer |

| N10 | Female | 24 | 1 | Novice | Primary School Teacher |

| I1 | Male | 28 | 4 | Intermediate | Software Engineer |

| I2 | Female | 32 | 3 | Intermediate | Accountant |

| I3 | Male | 23 | 5 | Intermediate | Physical Education Trainee |

| I4 | Female | 26 | 3.5 | Intermediate | Interior designer |

| I5 | Male | 31 | 4 | Intermediate | Sales Manager |

| I6 | Female | 29 | 3 | Intermediate | Journalist |

| I7 | Male | 35 | 5 | Intermediate | Lawyer |

| I8 | Female | 24 | 4 | Intermediate | Banker |

| I9 | Male | 27 | 3.5 | Intermediate | Bank Teller |

| I10 | Female | 33 | 4.5 | Intermediate | Accountant |

| E1 | Male | 26 | 8 | Elite | Primary School Teacher |

| E2 | Female | 24 | 7 | Elite | Sports Club Player |

| E3 | Male | 29 | 10 | Elite | Badminton Coach |

| E4 | Female | 22 | 6 | Elite | Sports Science Student |

| E5 | Male | 31 | 12 | Elite | Former National Player |

| E6 | Female | 27 | 9 | Elite | Semi-Professional Player |

| E7 | Male | 25 | 8 | Elite | Physical Trainer |

| E8 | Female | 30 | 11 | Elite | Badminton sports shop owner |

| E9 | Male | 28 | 9 | Elite | Sports Journalist |

| E10 | Female | 23 | 7 | Elite | National Team Trainee |

| Skill Level | Age Range (years) | Experience Range | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novice | 18-35 | 1 to 2 years | University students, young professionals |

| Intermediate | 23-35 | 3 to 5 years | Diverse professional backgrounds |

| Elite | 22-31 | 6 to 12 years | National team members, professional players |

| Skill Level | QE Duration (ms) | QE Onset (ms before impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Elite | 289.5 ± 34.2 | -385.2 ± 52.1 |

| Intermediate | 213.7 ± 41.5 | -298.6 ± 63.4 |

| Novice | 168.3 ± 38.9 | -215.4 ± 71.8 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Shot Accuracy | 1 | ||||

| 2. QE Duration | 0.72* | 1 | |||

| 3. QE Onset | -0.58* | -0.43* | 1 | ||

| 4. Racket Speed | 0.61* | 0.39* | -0.28 | 1 | |

| 5. Wrist Angle | 0.47* | 0.31 | -0.19 | 0.35* | 1 |

| Predictor | β | SE | t | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QE Duration | 0.45 | 0.08 | 5.62 | <0.001 |

| QE Onset | -0.21 | 0.09 | -2.33 | 0.028 |

| Racket Speed | 0.32 | 0.11 | 2.91 | 0.008 |

| Wrist Angle | 0.18 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.084 |

| Metric | Overall | Smashes | Drops | Clears |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 85.70% | 89.20% | 84.50% | 83.40% |

| Precision | 88.30% | 91.50% | 86.20% | 85.70% |

| Recall | 83.10% | 87.30% | 82.90% | 81.20% |

| F1 Score | 0.856 | 0.893 | 0.845 | 0.834 |

| Feature Set | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QE metrics only | 79.30% | 82.10% | 76.50% | 0.792 |

| Biomechanical features only | 77.80% | 80.60% | 75.00% | 0.777 |

| All features (full model) | 85.70% | 88.30% | 83.10% | 0.856 |

| Epoch | Training Loss | Validation Loss |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.98 | 1 |

| 5 | 0.75 | 0.79 |

| 10 | 0.62 | 0.67 |

| 15 | 0.54 | 0.6 |

| 20 | 0.49 | 0.56 |

| 25 | 0.46 | 0.53 |

| 30 | 0.44 | 0.51 |

| 35 | 0.42 | 0.5 |

| 40 | 0.41 | 0.49 |

| 45 | 0.4 | 0.48 |

| 50 | 0.39 | 0.48 |

| 55 | 0.38 | 0.49 |

| 60 | 0.37 | 0.5 |

| 65 | 0.36 | 0.52 |

| 70 | 0.35 | 0.54 |

| 75 | 0.34 | 0.57 |

| 80 | 0.33 | 0.61 |

| 85 | 0.32 | 0.66 |

| 90 | 0.31 | 0.72 |

| 95 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| 100 | 0.29 | 0.89 |

| Feature | SHAP Value |

|---|---|

| QE Duration | 0.385 |

| Racket Speed at Impact | 0.312 |

| QE Onset | 0.287 |

| Wrist Angle at Impact | 0.245 |

| Shuttlecock Trajectory Angle | 0.198 |

| Body Posture (Trunk Rotation) | 0.173 |

| Skill Level | Smashes (ms) | Drops (ms) | Clears (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elite | 301.2 ± 38.7 | 286.5 ± 35.9 | 280.8 ± 33.4 |

| Intermediate | 225.4 ± 44.3 | 209.8 ± 40.2 | 205.9 ± 42.6 |

| Novice | 172.6 ± 41.5 | 168.9 ± 39.7 | 163.4 ± 37.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).