1. Introduction

Rectal cancer (RC) is the third most common gastrointestinal malignancy, with a rising incidence, particularly among population under 50 years old [

1,

2]. Advances in managing rectal cancer have led to the development of multimodal treatment strategies, including the combined use of preoperative chemo/radiotherapy followed by surgery with or without adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and stage III RC patients [

3]. Mesorectal excision is the primary treatment option for localized rectal cancer [

4]. However, treating stage II RC patients remains a significant clinical challenge due to the higher risk of local and systemic recurrence. Although criteria such as clinicopathologic features, patient age, and specific tumor characteristics provide a framework for using adjuvant treatment in stage II rectal cancer, the decision is complex and should be individualized [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Further research is needed to refine these criteria and improve treatment outcomes.

The progression and spread of the primary tumor are crucial factors for predicting the prognosis. In addition to the TNM stage, several other invasive pathways of tumor spreading, including tumor perforation, perineural tumor invasion, tumor deposits, and tumor budding, are clinically relevant in predicting colorectal cancer [

9,

10]. Direct vascular spread, especially venous invasion, has also been recognized as an important predictor of adverse prognosis [

11]. Extramural venous invasion (EMVI) is defined as the presence of malignant cells in veins beyond the muscularis propria near the primary colorectal tumor [

12]. Invasion of extramural veins allows tumor cells to travel through the portal or systemic circulation, which is a critical step in the metastatic process [

13]. Pathologically detected EMVI in rectal carcinoma is associated with a higher incidence of local and distant metastases, as well as worse overall survival [

14,

15,

16]. Considering recent developments that have enabled the analysis of EMVI on preoperative MRI of the pelvis, the documented presence of EMVI can be a critical factor in stratifying and treating patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) [

17]. Radiomic models that include EMVI status, alongside other clinical factors, have been shown to effectively predict disease-free survival (DFS) in LARC patients [

18,

19,

20]. These models achieve high predictive performance, indicating the utility of integrating EMVI with other prognostic markers.

While EMVI is a significant prognostic marker, its role should be considered alongside other clinical and pathological factors. The College of American Pathologists (CAP) emphasized the importance of individual reporting of vascular invasion in the routine work of oncological surgical specimens [

21]. This organization especially highlighted the importance of detecting EMVI as an independent factor of poor prognosis and increased risk of liver metastases, while the relevance of intramural venous and lymphatic invasion is less clear and therefore neglected in routine work. In addition, the reporting of extra- and intramural vascular invasion presence is recommended but not a mandatory element of the pathohistological report [

22]. While the detection and reporting of EMVI provide significant prognostic and therapeutic insights, challenges remain in standardizing imaging techniques and interpretation across different clinical settings.

In this context, we performed a retrospective study to assess the prognostic value of separate pathological EMVI reporting in operative RC samples and to determine its relationship with standard pathohistological and surgical parameters among a selected cohort of RC patients from our institution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients Characteristic

In this retrospective study, we examined the clinical database for patients diagnosed with rectal cancer, confirmed by pathohistological findings. A total of 100 patients underwent curative resection for rectal cancer between January 2016 and June 2018 at our Institute. The exclusion criteria for patient selection were as follows: 1) Patients who had not undergone previous surgical resection for colorectal cancer; 2) Patients who had received neoadjuvant therapy were excluded from the study, as preoperative treatment may impact EMVI status; 3) Patients with synchronous or metachronous metastatic colorectal cancer; 4) Patients with another existing malignant disease. The disease stage was determined based on the Eighth Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual (14). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Oncology Institute of Vojvodina (protocol code 4/23/1-1819, date of approval 17.05.2023).

2.2. Tumor Characteristic

The data regarding tumor location and the type of surgery performed were gathered from the patient’s medical history. The information collected includes TNM classification, disease stage, number of resected lymph nodes, number of metastatic-positive lymph nodes (PLN), lymph node ratio (LNR), tumor deposit, histological grade (well, moderately, poorly differentiated tumors), circumferential resection margin (CRM), perineural (PNI), lymphovascular invasion (LVI), tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), and mucosal component of the tumor. The lymph node ratio is calculated by dividing the number of metastatic to retrieved lymph nodes. Patients were divided into three groups: LNR 1 (0-0.19), LNR2 (0.20-0.39), LNR3 (˃0.40).

2.3. Follow-Up

Patients underwent post-operative follow-up, including CT scans every 6 months for the first 2 years and then yearly scans for 5 years. Additionally, all patients had a colonoscopy performed 6 months after the surgery, with the frequency of subsequent endoscopic assessments determined by the pathology encountered. Disease-free survival (DFS) was measured from the date of surgery to the date of pelvic recurrence and/or distant disease. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause. Disease progression was defined as the occurrence of local recurrence or distant metastasis. Clinical and pathological factors were compared to assess their impact on local recurrence, distant metastasis, DFS, and OS.

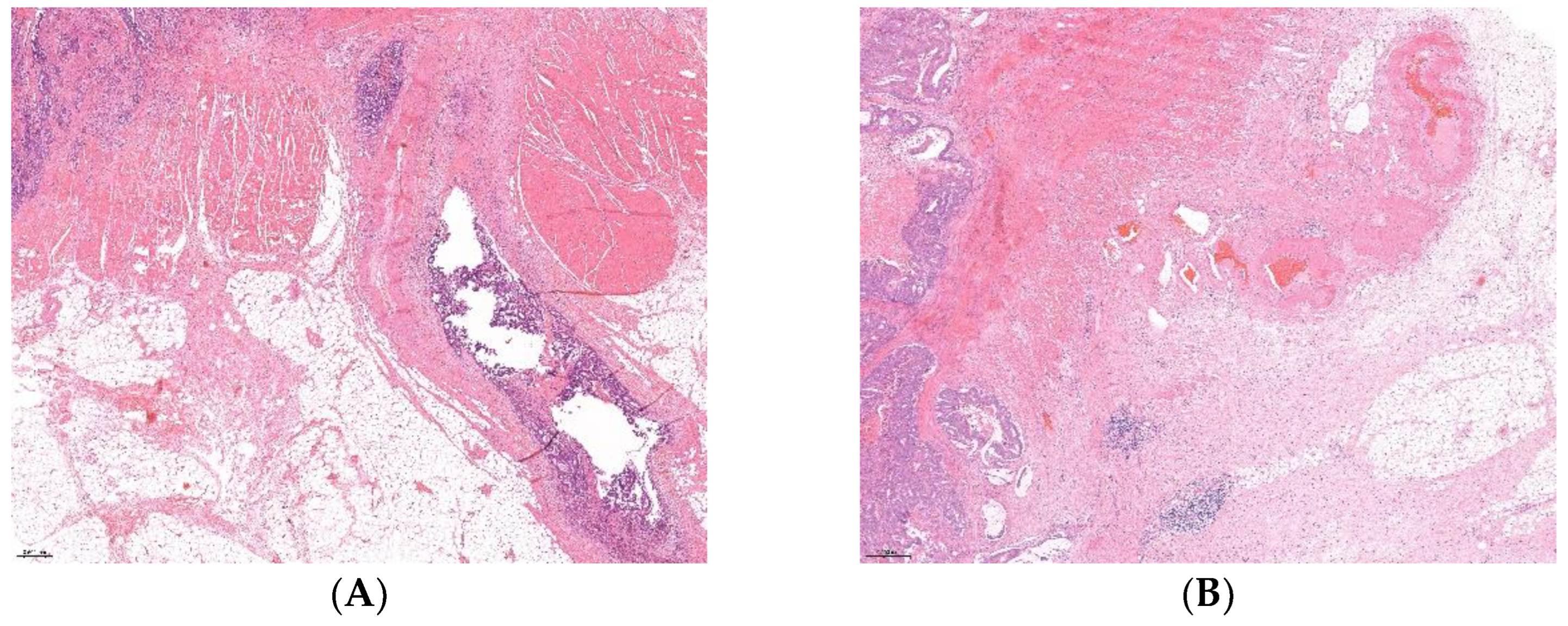

2.4. Pathological Analysis

Pathohistological slides of all included patients samlples were re-examined by a pathologist, and in arbitrary cases by two pathologists, who determined two groups of patients: with and without extramural venuos invasion. Patients were divided in equal EMVI-positive (EMVI+) and EMVI-negative (EMVI-) groups based on histological examination of H&E stained postoperative surgical samples. Re-evaluation was made in order to select patients with just extramural venuos invasion opposite to the lymphovascular invasion or just vascular invasion, as stated in prior pathohistological reports, according to the former protocols. The number of re-examined slides per patient was between 3 and 10.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

For contingency variables, the χ2-test or Fisher’s exact two-tailed test was used when the expected frequencies were lower than five. For continuous variables, the Student’s t-test was used. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (X±SD), while categorical variables were presented by number of cases (percentage). All variables that showed a significant correlation with death outcome and relapse of disease (p<0.05) were analyzed using the Cox Hazard Ratio (Cox HR) model, which was used for both univariate and multivariate regression analysis. The variables that showed significant differences (p<0.05) in univariate analysis were selected for multivariate regression analysis to assess predictors of OS and DFS. Overall and disease-free survival distributions were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences were evaluated by the Log-rank test. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests. All statistical analyses were performed using the Sigma Plot 14.0 licensed statistical analysis software package.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

This retrospective study included 100 RC patients who met inclusion criteria, whose average age was 64.6±9.6 years (range 40-83). The group consisted of 62 (62%) male and 38 (38%) female patients, whose average age did not differ significantly (65.1±9.4 vs. 63.8±9.9 years, p=0.528). Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) was detected in 52/100 (52%) tumor samples, while in 18/100 (18%) cases, perineural invasion (PNI) was observed. According to our criteria of LNR classification, 79/100 (79%) cases were classified as LNR1, 10/100 (10%) as LNR2, and 11/100 (11%) cases were included in LNR3 group. After performed surgery, adjuvant treatment received 61/100 (61%) of RC patients.

3.2. Association of EMVI Status with Clinico-Pathological Parameters

Out of the 100 selected RC patients, there were 50 EMVI+ and 50 EMVI- cases (

Figure 1). Clinical and pathohistological characteristics of patients and tumors in relation to EMVI status are presented in

Table 1. We should note that among EMVI positive patients (EMVI+) 46/50 (92%) were in NO pre-operative stage, 46 out of 50 (92%) were treated with sphincter-preserving surgery, and 47/50 (94%) EMVI+ patients received adjuvant treatment. The presence of EMVI within the selected cohort was significantly associated with female gender (p=0.039), T3/T4 post-operative stages (p<0.001), N1/N2 post-operative stages (p<0.001), positive lymph nodes (PLN˃3, p<0.001), lymph node ratio LNR2 and LNR3 groups (p<0.001), and abundant tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) (p=0.044). According to the binary classified TNM stage, there were significantly more EMVI+ cases among TNMIII/IV tumor stages than within TNMI/II (86.7% vs. 20%, p<0.001). A significant association was also observed between the presence of EMVI and positive LVI, PNI, and CRM (p<0.05 in all tests), while adjuvant therapy was more frequently applied on EMVI+ patients than on EMVI- (70.5% vs. 29.5%, p<0.001).

3.3. Relapse of Disease and Death Outcome in RC Patients

In this study, the median follow-up period after surgery was 56 (range 12-76) months. The median survival without recurrence of the disease was 52 (range 4-76) months. Out of the total RC patients, 66 (66%) were still alive during the follow-up period, while 30 (30%) had verified recurrence of the disease. Clinical and pathohistological features related to the outcome and relapse of the disease are listed in

Table 2. As expected, advanced TNM stages, positive lymph nodes (PLN˃3), and high LNR are significantly associated with more common death outcomes and relapse of disease (p<0.05 in all tests). Considering EMVI status, there were more EMVI+ patients with local recurrences and/or metastases (44% vs. 24%) and death outcomes recorded (40% vs. 20%) than EMVI- cases (p=0.035 and p=0.029, respectively). The presence of LVI was also associated with relapse of disease (p=0.018), while we noted a statistical trend toward the relationship between LVI+ and death outcome (p=0.068). In addition, adjuvant treatment was significantly related to more common death and relapse events (p=0.023 and p<0.001, respectively).

3.4. Overall and Disease-Free Survival of RC Patients

Results of univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis for the overall survival period are listed in

Table 3. Regarding the clinicopathological parameters, univariate analysis showed that OS of RC patients was significantly associated with N1 preoperative stage (p=0.003), PLN˃3 (p<0.001), LNR2 and LNR3 (p=0.038 and p<0.001, respectively), TNMIII/IV stages (p=0.023), presence of EMVI (p=0.045), and positive CRM (p=0.030). Analysis of EMVI status in relation to OS by univariate COX regression revealed that EMVI+ patients had a 2.053 times higher risk of death during the period of postoperative follow-up (95% CI: 1.015-4.152; p=0.045). The remaining analyzed risk parameters: T and N pathological stage, LVI and PNI status, did not show a statistically significant association with the overall survival time by univariate analysis (p>0.05), while received adjuvant therapy almost reached statistical significance (p=0.05). After performing multivariate Cox regression, none of the included risk parameters retained the statistical significance (p˃0.05).

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses for disease-free survival are summarized in

Table 4. Using univariate Cox regression for DFS, a statistically significant relationship was found with: pre-operative N (p<0.001), PLN˃3 (p<0.001), LNR3 (p<0.001), TNM III/IV stage (p=0.017), and positive EMVI and CRM (p=0.038 and p=0.013, respectively). Regarding EMVI status, univariate analysis revealed that EMVI+ patients had a 2.106 times higher risk of disease recurrence than EMVI- patients (95% CI: 1.066-4.870; p=0.038). After adjustment in multivariate analysis, N1 pre-operative stage (HR: 4.632, 95% CI: 1.255-17.100; p=0.021) and positive CRM (HR: 3.331, 95% CI: 1.059-10.480; p=0.040) were obtained as an independent prognostic factor of survival time without relapse in RC patients, while statistical significance for EMVI+ was lost in multivariate regression analysis (p=0.996).

3.5. Comparison of Prognostic Significance of EMVI and LVI Status

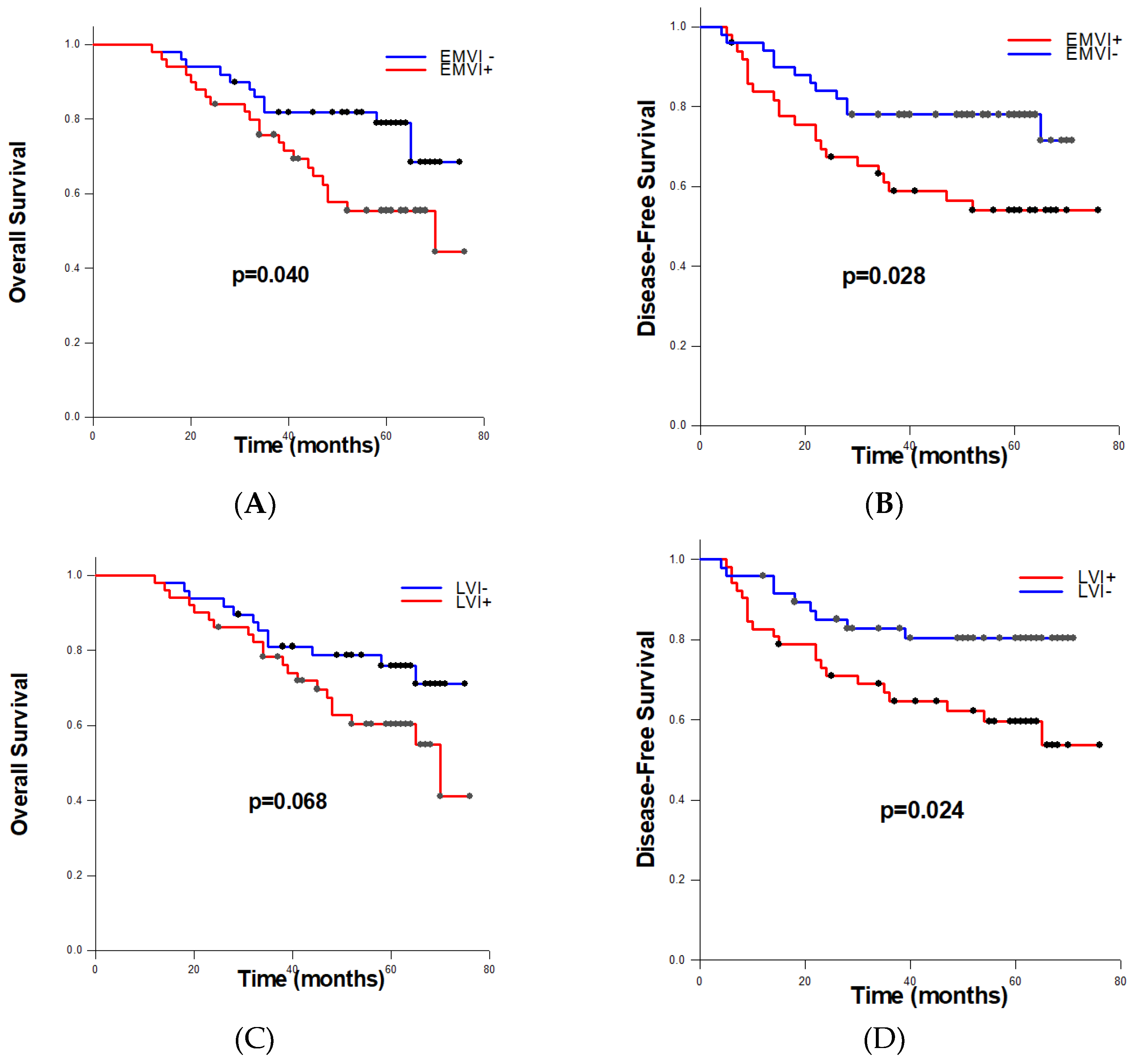

To estimate obtained differences in overall and disease-free survival among RC patients according to the EMVI and LVI status, we performed Log-rank tests. Patients with detected EMVI had significantly shorter average OS (56.230±3.350 months) compared to patients without EMVI (64.640±2.845 months) (p=0.040) (

Figure 2A). Moreover, among EMVI+ cases, significantly shorter average DFS was recorded than within EMVI- cases (52.162±4.319 vs. 61.338±3.041 months, p=0.028) (

Figure 2B). Concerning lymphovascular invasion, differences in overall-survival between LVI+ and LVI- patients were not statistically significant (p=0.068), while patients identified as LVI positive had significantly shorter disease-free survival (p=0.024) (

Figure 2C,D).

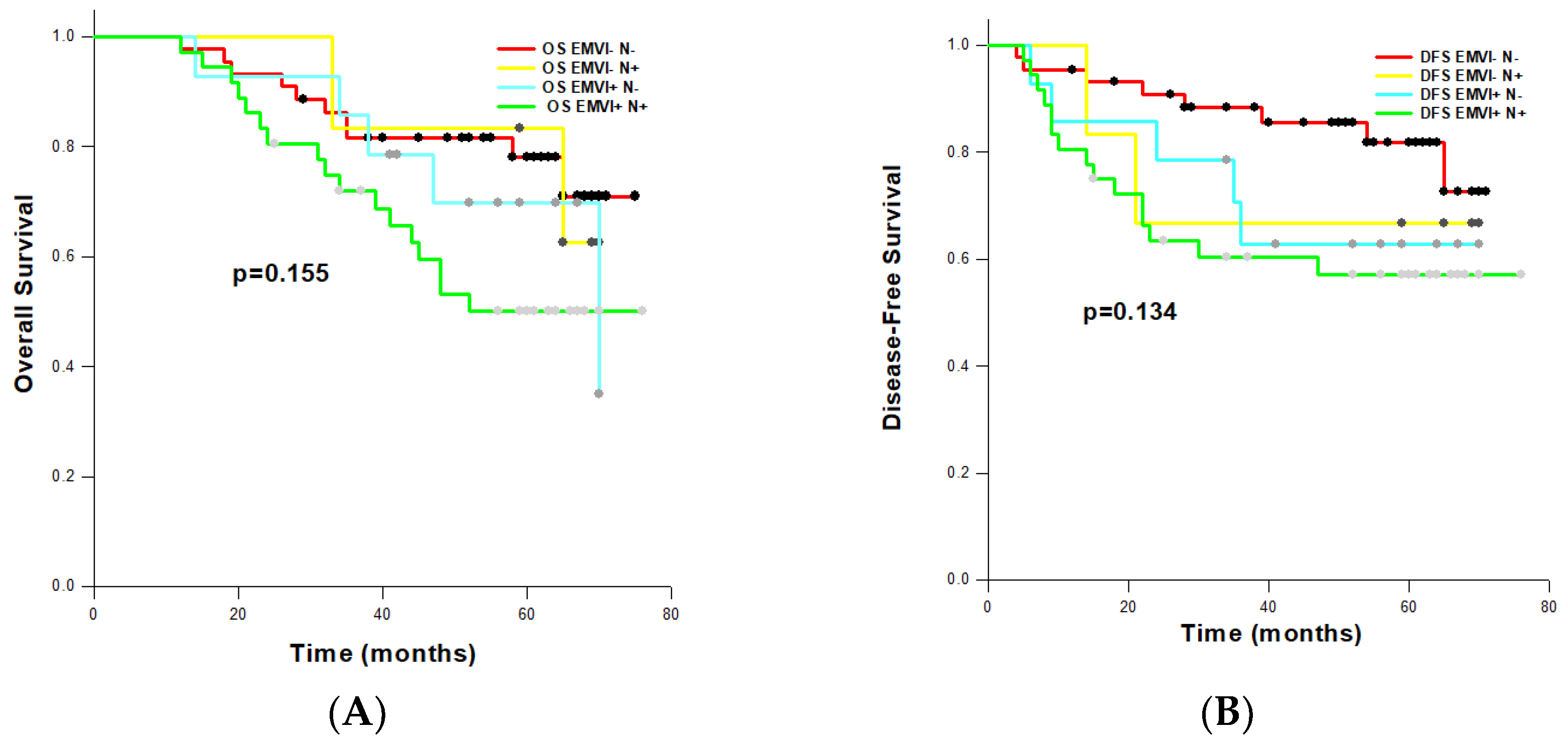

3.6. Comparison of Prognostic Significance of EMVI and N Status

To assess the combined impact of EMVI and pathological nodal (N) status on OS and DFS, we defined four categories according to the EMVI and N status: EMVI−/N−, EMVI+/N−, EMVI−/N+, EMVI+/N−. On univariate analysis, EMVI+/N+ combination was a significant factor for reduced OS (HR: 2.369, 95% CI: 1.084-5.178; p=0.031) and DFS (HR: 2.699, 95% CI: 1.143-6.375; p=0.024). As expected, EMVI+/N+ cases had the shortest OS (54.452±4.080 months) and DFS (50.624±5.267 months) estimated by the Log-rank tests (

Figure 3A,B). We also noted that EMVI+/N- patents had worse overall- and disease-free survival (OS: 59.135±5.403; DFS: 52.364-7.322 months) than EMVI−/N+ patients (OS: 62.792±7.797; DFS: 52.500±14.336 months), although observed differences were not statistically significant (OS: p=0.155; DFS: p=0.134).

4. Discussion

Venous invasion is routinely evaluated in colorectal cancer in daily clinical practice and is classified as intramural and extramural. The anatomic location of the invaded vessel can be important for predicting the prognosis of patients with rectal cancer [

11,

23]. These tumors have an increased potential for vascular seeding. Since the tumor is aggressive enough to invade blood vessels directly, it makes sense that these patients are at higher risk of having occult disease [

24]. Within this study, extramural venous invasion was observed as a potentially negative predictor of rectal cancer outcome. Finally, extramural venous invasion (EMVI) is proven to be not only a feature of aggressive tumor behavior but also a separate and independent parameter in patients with rectal cancer. This is in accordance with multiple studies demonstrating its association with poorer patient outcomes [

25].

The current study proved that EMVI is significantly associated with already established parameters of worse prognosis, including T3/T4 pathological stages (p<0,001), N1/N2 pathological stages (p<0,001), positive lymph nodes (PLN>3, p<0,001) and lymph node ratio LNR2 and LNR 3 (p<0,001), as well as abundant TIL (p=0,004), positive LVI, PNI and CRM (p<0,05 in all tests), which is in agreement with the results of multiple studies [

24,

26,

27].

While it has been well established that patients with stage III colorectal cancer should be offered adjuvant chemotherapy [

28,

29], the guidelines for stage II colorectal cancer are not as clear. The current guidelines from the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain & Ireland (ACGBI), as well as the European Society for Medical Oncology, suggest that patients with high-risk stage II disease, of which EMVI is considered one of the high-risk factors, should be considered for adjuvant chemotherapy [

27,

30,

31]. According to this study, adjuvant therapy was more frequently applied on EMVI+ patients than on EMVI- (p<0,001), which is consistent with the finding by Mc Entee et al. where the authors emphasize that the presence of EMVI should be strongly considered as an indication for adjuvant therapy [

26]. This is consistent with the findings of McClelland and colleagues, who also claim that EMVI+ patients in stage II may benefit from and should be strongly considered for adjuvant chemotherapy [

27].

Extramural venous invasion (EMVI) has been identified as a strong and independent predictor of poor prognosis and increased risk of disease recurrence [

24,

26,

27,

31]. In our study, more EMVI+ patients experienced local recurrences and/or metastases than EMVI- patients (p=0.035), consistent with previous research findings [

12,

24,

26,

31]. Additionally, a higher number of EMVI+ patients had recorded instances of death compared to EMVI- patients (p=0.029), which also aligns with other studies [

24,

26].

The main finding of this study is that patients with detected EMVI had significantly shorter average overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) compared to EMVI- patients, whether they had stage II or stage III rectal cancer (p=0.040 and p=0.028, respectively), which is consistent with other research findings [

23,

24,

26,

27,

31]. Furthermore, this study revealed that differences in OS between lymphovascular invasion LVI+ and LVI- patients were not statistically significant (p=0.068), suggesting the potential superiority of EMVI as a separate and independent negative predictor of disease. Moreover, univariate COX regression analysis demonstrated the negative impact of EMVI on OS (HR: 2.053, 95% CI: 1.015-4.152; p=0.045) and DFS (HR: 2.106, 95% CI: 1.066-4.870; p=0.038), which was not the case for LVI+ RC patients. This result aligns with previous recommendations suggesting that lymphatic and vascular invasion, especially EMVI, should be separately reported [

12,

32,

33,

34] due to their distinct spread pathways and impacts on tumor aggressiveness [

11].

Among the categories formed to assessed the combined effect of EMVI and nodal on overall and disease-free status, in EMVI+/N- category were recorded worse OS and DFS than in EMVI-/N+ category of patients, suggesting the dominance of EMVI status in prognostic stratification of patients, although observed differences were not statistically significant (p=0,155 and p=0,134, respectively). Similar importance of EMVI status was observed in the study by Chand et al. [

31], while other authors provide evidence that the accuracy of nodal staging is limited, and it has not consistently demonstrated prognostic importance in rectal cancer [

35]. Although our results of univariate COX regression analysis clearly demonstrated the negative impact of EMVI on OS and DFS, after adjusting in multivariate analyisis statistical significance for EMVI+ was lost, which is not in accordance with other studies [

24,

36,

37]. Thus, the exact role of postoperative detected EMVI should be re-evaluated with a larger number of patients included in the study.

Methods for evaluating EMVI include preoperative radiologic and postoperative pathologic examinations [

16]. Recent advances in MRI mean it is possible to assess EMVI in pre-operative investigations for rectal cancer [

38]. EMVI assessed by MRI has been associated with an increased risk of local and systemic disease recurrence and diminished survival [

20,

25,

38,

39]. MRI detection of EMVI (mrEMVI) has been shown to be accurate and correlate highly with pathology for those patients who have undergone primary surgery [

23,

25]. The College of American Pathologists recommends recording the status of extramural vascular invasion during routine pathologic examination in rectal cancer patients [

21]. A pathological finding of EMVI should prompt strong consideration of adjuvant therapy for patients who have undergone a curative colorectal cancer resection [

24,

26]. In daily practice it is not common for EMVI to be reported as part of a routine pathologic examination. Depending on the institutional practice, sometimes it is reported as vascular invasion and sometimes as part of LVI. However, the results of this study showed that it makes sense to consider EMVI separately from LVI, as well as that EMVI could be a good addition to TNM staging. In addition, EMVI would have even greater prognostic potential if routinely observed on preoperative pelvic MRI.

5. Conclusion

The results we obtained strongly suggest the importance of separately reporting extramural vascular invasion (EMVI) from lymphovascular invasion. EMVI could potentially serve as a surrogate marker for adverse prognosis and outcome. Our findings indicate that patients with detected EMVI had significantly shorter average overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) compared to EMVI-negative patients, even in the lower stages of rectal cancer. Therefore, we need to pay closer attention to detecting and reporting EMVI during both pathological and radiological examinations in our daily practice.

Author Contributions

M. Đ. writing—original draft preparation, methodology, data curation, investigation; B.K. conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, methodology, formal analysis, review and editing, supervision; T. V. investigation, methodology, visualization; A. Đ. investigation, data curation; N. S. investigation, methodology; M. Đ. writing—original draft preparation, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Oncology Institute of Vojvodina (protocol code 4/23/1-1819, date of approval 17.05.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Spanos, CP. Rectal cancer. Colorectal Disorders and Diseases, Elsevier; 2023, p. 127–34. [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J Clinicians 2021;71:209–49. [CrossRef]

- Ghadimi M, Rödel C, Hofheinz R, Flebbe H, Grade M. Multimodal treatment of rectal cancer. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fujita S, Mizusawa J, Kanemitsu Y, Ito M, Kinugasa Y, Komori K, et al. Mesorectal Excision With or Without Lateral Lymph Node Dissection for Clinical Stage II/III Lower Rectal Cancer (JCOG0212): A Multicenter, Randomized Controlled, Noninferiority Trial. Annals of Surgery 2017;266:201–7. [CrossRef]

- Hagerty BL, Aversa JG, Dominguez DA, Davis JL, Hernandez JM, McCormick JT, et al. Age Determines Adjuvant Chemotherapy Use in Resected Stage II Colon Cancer. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 2022;65:1206–14. [CrossRef]

- Chun HJ, Park SJ, Lim YJ, Song SY. Staging and Treatment. II-7. Overview of Treatment of Rectal Cancer. Gastrointestinal Cancer, Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2023, p. 279–86. [CrossRef]

- Baxter NN, Kennedy EB, Bergsland E, Berlin J, George TJ, Gill S, et al. Adjuvant Therapy for Stage II Colon Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. JCO 2022;40:892–910. [CrossRef]

- Bang HJ, Shim HJ, Hwang JE, Bae WK, Chung IJ, Cho SH. Benefits of Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Clinical T3-4N0 Rectal Cancer After Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy. Chonnam Med J 2023;59:76. [CrossRef]

- Sargent D, Sobrero A, Grothey A, O’Connell MJ, Buyse M, Andre T, et al. Evidence for Cure by Adjuvant Therapy in Colon Cancer: Observations Based on Individual Patient Data From 20,898 Patients on 18 Randomized Trials. JCO 2009;27:872–7. [CrossRef]

- Babaei M, Balavarca Y, Jansen L, Lemmens V, Van Erning FN, Van Eycken L, et al. Administration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II-III colon cancer patients: An European population-based study. Intl Journal of Cancer 2018;142:1480–9. [CrossRef]

- Lord AC, Knijn N, Brown G, Nagtegaal ID. Pathways of spread in rectal cancer: a reappraisal of the true routes to distant metastatic disease. European Journal of Cancer 2020;128:1–6. [CrossRef]

- Betge J, Pollheimer MJ, Lindtner RA, Kornprat P, Schlemmer A, Rehak P, et al. Intramural and extramural vascular invasion in colorectal cancer: Prognostic significance and quality of pathology reporting. Cancer 2012;118:628–38. [CrossRef]

- Van Zijl F, Krupitza G, Mikulits W. Initial steps of metastasis: Cell invasion and endothelial transmigration. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research 2011;728:23–34. [CrossRef]

- McClelland D, Murray GI. A Comprehensive Study of Extramural Venous Invasion in Colorectal Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0144987. [CrossRef]

- Pangarkar SY, Baheti AD, Mistry KA, Choudhari AJ, Patil VR, Ahuja A, et al. Prognostic Significance of EMVI in Rectal Cancer in a Tertiary Cancer Hospital in India. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2021;31:560–5. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui MRS, Simillis C, Hunter C, Chand M, Bhoday J, Garant A, et al. A meta-analysis comparing the risk of metastases in patients with rectal cancer and MRI-detected extramural vascular invasion (mrEMVI) vs mrEMVI-negative cases. Br J Cancer 2017;116:1513–9. [CrossRef]

- Smith NJ, Barbachano Y, Norman AR, Swift RI, Abulafi AM, Brown G. Prognostic significance of magnetic resonance imaging-detected extramural vascular invasion in rectal cancer. British Journal of Surgery 2008;95:229–36. [CrossRef]

- Hu T, Gong J, Sun Y, Li M, Cai C, Li X, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-based radiomics analysis for prediction of treatment response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and clinical outcome in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer: A large multicentric and validated study. MedComm 2024;5:e609. [CrossRef]

- Cai L, Lambregts DMJ, Beets GL, Mass M, Pooch EHP, Guérendel C, et al. An automated deep learning pipeline for EMVI classification and response prediction of rectal cancer using baseline MRI: a multi-centre study. Npj Precis Onc 2024;8:17. [CrossRef]

- Geffen EGMV, Nederend J, Sluckin TC, Hazen S-MJA, Horsthuis K, Beets-Tan RGH, et al. Prognostic significance of MRI-detected extramural venous invasion according to grade and response to neo-adjuvant treatment in locally advanced rectal cancer A national cohort study after radiologic training and reassessment. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2024;50:108307. [CrossRef]

- Protocol for the examination of Resection Specimens From Patients With Primary Carcinoma of the Colon and Rectum. 2024. Available: https://www.cap.org/protocols-and-guidelines/cancer-reportingtools/

cancer-protocol-templates.

- Washington MK, Berlin J, Branton P, Burgart LJ, Carter DK, Fitzgibbons PL, et al. Protocol for the Examination of Specimens From Patients With Primary Carcinoma of the Colon and Rectum. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2009;133:1539–51. [CrossRef]

- Shin Y-M, Pyo J-S, Park MJ. The Impact of Extramural Venous Invasion in Colorectal Cancer: A Detailed Analysis Based on Tumor Location and Evaluation Methods. Int J Surg Pathol 2020;28:120–7. [CrossRef]

- Leijssen LGJ, Dinaux AM, Amri R, Taylor MS, Deshpande V, Bordeianou LG, et al. Impact of intramural and extramural vascular invasion on stage II-III colon cancer outcomes. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2019;119:749–57. [CrossRef]

- Ale Ali H, Kirsch R, Razaz S, Jhaveri A, Thipphavong S, Kennedy ED, et al. Extramural venous invasion in rectal cancer: overview of imaging, histopathology, and clinical implications. Abdom Radiol 2019;44:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Mc Entee PD, Shokuhi P, Rogers AC, Mehigan BJ, McCormick PH, Gillham CM, et al. Extramural venous invasion (EMVI) in colorectal cancer is associated with increased cancer recurrence and cancer-related death. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2022;48:1638–42. [CrossRef]

- McClelland D, Murray GI. A Comprehensive Study of Extramural Venous Invasion in Colorectal Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0144987. [CrossRef]

- Piercey O, Wong H-L, Leung C, To YH, Heong V, Lee M, et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Older Patients With Stage III Colorectal Cancer: A Real-World Analysis of Treatment Recommendations, Treatment Administered and Impact on Cancer Recurrence. Clinical Colorectal Cancer 2024;23:95-103.e3. [CrossRef]

- Shahireen S, Eka V, Rachamsetty K, Duraiswamy D, L RCR. An expatiate review on adjuvant chemotherapy of colorectal cancer. Fut J Pharm & H Sci 2024;4:80–8. [CrossRef]

- Chand M, Evans J, Swift RI, Tekkis PP, West NP, Stamp G, et al. The prognostic significance of postchemoradiotherapy high-resolution MRI and histopathology detected extramural venous invasion in rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2015;261:473–9. [CrossRef]

- Chand M, Bhangu A, Wotherspoon A, Stamp GWH, Swift RI, Chau I, et al. EMVI-positive stage II rectal cancer has similar clinical outcomes as stage III disease following pre-operative chemoradiotherapy. Annals of Oncology 2014;25:858–63. [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk HC, Roxburgh CS, Horgan PG, Foulis AF, McMillan DC. The detection and role of lymphatic and blood vessel invasion in predicting survival in patients with node negative operable primary colorectal cancer. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2014;90:77–90. [CrossRef]

- Maguire, A. Controversies in the pathological assessment of colorectal cancer. WJG 2014;20:9850. [CrossRef]

- Langner C, Schneider N. Prognostic stratification of colorectal cancer patients: current perspectives. CMAR 2014:291. [CrossRef]

- Lord A, D’Souza N, Shaw A, Day N, Brown G. The Current Status of Nodal Staging in Rectal Cancer. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep 2019;15:143–8. [CrossRef]

- Schirripa M, Cohen SA, Battaglin F, Lenz H-J. Biomarker-driven and molecular targeted therapies for colorectal cancers. Seminars in Oncology 2018;45:124–32. [CrossRef]

- Missiaglia E, Jacobs B, D’Ario G, Di Narzo AF, Soneson C, Budinska E, et al. Distal and proximal colon cancers differ in terms of molecular, pathological, and clinical features. Annals of Oncology 2014;25:1995–2001. [CrossRef]

- Tan JJ, Carten RV, Babiker A, Abulafi M, Lord AC, Brown G. Prognostic Importance of MRI-Detected Extramural Venous Invasion in Rectal Cancer: A Literature Review and Systematic Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 2021;111:385–94. [CrossRef]

- Inoue A, Sheedy SP, Heiken JP, Mohammadinejad P, Graham RP, Lee HE, et al. MRI-detected extramural venous invasion of rectal cancer: Multimodality performance and implications at baseline imaging and after neoadjuvant therapy. Insights Imaging 2021;12:110. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).