1. Introduction

Islamic religious architecture has transformed in recent decades due to cultural evolutions, technological advancements, and artistic innovation. Mosques, as symbols of spiritual sanctity and communal identity, have also been influenced by modern architectural styles. This research focuses on understanding the impact of these trends on mosque design in Sulaymaniyah Governorate in Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

The Kurdistan Region, particularly Sulaymaniyah, has seen significant mosque construction over the past thirty years, driven by economic and political developments since 1991 and then 2003. This construction boom has raised questions about the alignment of new architectural features with the religious objectives of mosques design, providing a unique opportunity to study the relationship between tradition and modernity in mosque design.

This study examines the diverse manifestations of modern architectural style in contemporary mosques, considering the multifaceted dimensions affecting their essential features. By analyzing mosques in Sulaymaniyah Governorate, the research aims to understand how traditional Islamic architectural elements and modern design principles intersect, raising questions about religious legitimacy, historical symbolism, and the role of architecture in shaping religious values.

Several recent studies explore the influence of modern architectural trends and technologies on mosque design, highlighting the contemporary developments to maintain the spiritual essence and cultural identity of mosques. AL-Ammar & AL-Atabey [

1] and Toorabally, Sieng, Norman, & Razalli [

2] examine the impact of contemporary technologies on the mosque architecture. In addition, Niknam, Rezaei, & Zehtaban [

3] examine the influence of contemporary architecture on Islamic motifs in mosques. Furthermore, Ra’ouf & Al-Muqram [

4] propose hypotheses focusing on functional, aesthetic, and symbolic religious factors as primary drivers of contemporary mosque architecture, contrasting with traditional and environmental influences. Al Tal [

5], Hoteit [

6] and Mahdavinejad [

7] also examine how modern architectural theories and trends impact mosque design. The reviewed studies collectively underscore the importance of balance between modern architectural trends and traditional elements in mosque design to uphold the spiritual essence and cultural identity.

Further studies delve into the evolution of contemporary mosque architecture, exploring the interplay between modernization, symbolism, and technological advancements. These studies highlight the complex dynamics shaping contemporary mosque designs. Hamzehnejad & Amirabadi Farahani [

8] identify authenticity criteria for contemporary mosques in the Islamic world, and Awad [

9] and Mahmoud & Abobakr [

10] explore contemporary mosque design trends in northern UAE cities and worldwide respectively. In addition, Al-Bukhari, Alsabban, & Shehata [

11] emphasize how modern mosques reflect technological advancements, societal needs, and economic status while preserving cultural and spiritual identity. Furthermore, Alkhaled [

12], Alhefnawy & Istanbouli [

13] and Toman [

14]examine the contemporary mosque architecture in Turkey, Italy and Riyadh respectively. Asfour [

15] also examines mosque architecture’s evolution from historical to contemporary styles, highlighting the tension between modernism and symbolism.

In addition, several studies explore different aspects of mosque architecture in the Kurdistan Region. Mustafa & Rashid [

16] and Abdulhamid, Qadir, & Ali [

17] focus on the proportion in mosques in Erbil, and Mustafa & Ismael [

18] conducted a typological study of historical mosques in Erbil as well. Furthermore, Qaradaghi & Qadir [

19] investigated the influence of cultural aspects on mosque architecture, particularly those built between 1970-1990 in Erbil. Sadiq [

20] explored the impact of architectural conservation on the Great Mosque in Duhok. The only study, that examined the mosques in Sulaymaniyah, is Qaradaghi [

21] which studied the architectural and spatial configuration of mosques, emphasizing their unique styles compared to global Islamic patterns. The researchers conclude that cultural and natural factors played a pivotal role in shaping the distinct architectural features of Sulaymaniyah mosques.

Despite the extensive research on mosque architecture evolution and contemporary trends, a research gap exists regarding the specific impact of modern architectural styles on mosque evolution, particularly in the Sulaymaniyah Governorate in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. While previous studies have explored various aspects of mosque design, including structural elements, decorative features, and cultural influences, few have focused on the nuanced interplay between traditional Islamic architecture and modern design principles in this specific regional context. Additionally, while some studies have addressed the need to balance tradition with innovation in mosque design, there is limited research on the religious legitimacy and historical symbolism of contemporary mosques, particularly in relation to modern architectural indicators and achieved design objectives. Therefore, a research gap exists, calling for a dedicated exploration of the transformative impact of modern architectural styles on mosque evolution in this region, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of contemporary mosque architecture.

The research hypothesis is that the adoption of modern architectural style principles will have a significant impact on the evolution of contemporary mosque design in Sulaymaniyah Governorate influencing design objectives related to specifically indoor environment of musalla and external symbolic features.

1.1. Historical Evolution of Mosques

The evolution of mosques through different periods and regions reflects diverse architectural styles and influences. Initially, the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and his companions constructed a simple mosque with a covered prayer shed, which later expanded to include arcades [

22]. This model served as a spiritual type for mosque architecture, allowing for flexibility and diversity in design [

23]. During the Umayyad period, mosques became more specialized, serving various purposes beyond prayer, while the Abbasid era saw further development and the establishment of mosque-palace complexes [

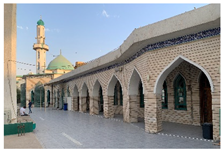

24] (pp. 4 & 8). In Morocco and Andalusia, mosques followed the hypostyle type, influenced by Syrian architecture, with later innovations including complex vaulting and domes. In Yemen, mosques integrated elements from pre-Islamic temples. Anatolian and Kurdistan mosques, influenced by Iranian and Arabic traditions, featured pillared designs and emphasized arches and vault coverings [

22]. In Egypt, mosques evolved from simple structures to more elaborate designs under the Fatimid, Ayyubid, and Mamluk periods, with distinct features such as keel arches and intricate minaret shapes [

25,

26]. Iranian mosques, influenced by pre-Islamic traditions, incorporated domes and iwans, with developments seen in Seljuk, Ilkhanid, Timurid, and Safavid periods [

22]. Ottoman mosques, shaped by various cultural influences, evolved from simple hypostyle plans to more complex domed-square structures, reflecting the Ottoman concern for integrating large spaces with minimal vertical supports across successive stages of development [

27] (pp. 19 & 29).

The evolution of mosques over history in different regions resulted in shaping basic elements contributing to their architectural form and function. These elements can be classified into basic and additional components. Basic elements include the musalla (prayer hall), sahn (courtyard), mihrab (niche), and minbar (pulpit). While, additional elements encompass the minaret, dome, ablution facilities, riwaq (arcade), maqsurah (enclosure), reading desk, mosque furniture, and gate. The musalla serves as the main prayer area, typically adopting a rectangular shape parallel to the Qibla wall for optimal alignment. The sahn, an open central area, offers space for congregation and passive cooling purposes. It is surrounded by covered arcades called riwaq. The sahn enhances the mosque’s aesthetic appeal and functionality. Minarets, which are vertical features, historically symbolize Islam’s presence and solemnity, evolving in shape and style over time. Domes, prevalent in mosque architecture, symbolize the sky and aid in lighting, acoustics and ventilation [

15] (pp. 2) and [

6] (pp. 13548). The mihrab, resembling marks the direction of prayer, while the minbar, positioned nearby, is a stepped pulpit to facilitate the Imam’s sermon delivery. Enclosures like the maqsurah, once reserved for rulers, underscored their status and protection [

22]. Ablution facilities, is integral to Islamic worship, ensure ritual purity before prayer, evolving from fountains to designated rooms within mosque complexes. These elements, with their historical, functional, and symbolic significance, collectively shape the architectural identity and experience of mosques worldwide [

6] (pp. 13551).

Various types of mosques have emerged across different regions, each influenced by local architectural features and climatic conditions [

6] (pp. 13551). While fundamental elements like arches, domes, minarets, and mihrabs are common throughout the Muslim world, regional variations have led to distinct styles [

28] (pp. 1). Six traditional typologies include the hypostyle or Arabic type, Turkish or Ottoman type, Iranian or Persian type, Indian type, and Chinese type. The hypostyle mosque, originating in Arabia, features a large courtyard and a covered prayer hall, often with dome variations and diverse minaret forms [

15] (pp. 5)

. The Persian style, characterized by four iwans surrounding a courtyard, exhibits bulbous domes and colorful ornamentation [

6] (pp.13552). Ottoman mosques boast centralized domes and slender minarets, influenced by Byzantine architecture [

15] (pp. 6), while Indian mosques feature triple domes and spacious courtyards. Chinese mosques resemble traditional Chinese buildings, with walled complexes, timber structures, and distinctive roof forms, exemplified by the Great Mosque of Xi’an [

6] (pp. 13553 & 13553). These variations reflect the diverse cultural and architectural influences shaping mosque design across regions.

Certain functional and symbolic requirements that are considered as essential in mosque design:

Orientation to the Qibla: The most important aspect of the mosque is the orientation of the musalla to the Qibla [

29] (pp. 54), [

30] (pp. 138) and [

15] (pp. 7). It is also confirmed by the Holy Quran in Surat al-Baqarah, Verse 144.

Avoiding cutting off rows by excessive number of columns or walls and eliminating view restrictions [

15] (pp. 7) and [

6] (pp. 13554).It is confirmed by Hadiths of the Prophet (PBUH) as follows: “…Whoever joins up a row, he will be joined to Allah; and whoever cuts off a row, he will be cut off from Allah”[

31] (pp. Hadith 101).

Use plan forms allowing longer rows, especially the first row [

15] (pp. 7). This is due to the virtue of the first row which is confirmed by Hadiths of the Prophet (PBUH) such as follows: “If people came to know the blessing of calling Adhan and the standing in the first row, they could do nothing but would draw lots to secure these privileges” [

31] (pp. Hadith 93).

Providing a quiet environment for concentration, reverence, and piety during prayer [

6] (pp. 13554). The Quran describes the believers during prayer, stating: “Successful are the believers. Those who are humble in their prayers. Those who avoid nonsense” [

32] (pp. 126, Verses 1, 2 & 3).

Avoiding over-decoration that may interrupt prayer’s concentration [

15] (pp. 7). It is confirmed in the Hadith of the Prophet (PBUH) as follows: “The Hour (Judgement Day) will not come until people boast (to each other) with (the construction and decoration of) mosques” [

33] (pp. Hadith 135).

Using the recognizable form as a mosque. Incorporating symbolic features into new mosque designs maintains cultural continuity and fosters a sense of Islamic identity within communities. Fethi [

29] (pp. 54 & 60) introduced these symbolic features as minarets, domes, arches, vaults, and decorative elements. They hold deep symbolic meaning rooted in Islamic tradition and contribute to the aesthetic harmony of mosque architecture. By respecting tradition and honoring past generations, new mosque designs can create a spiritually conducive atmosphere while also embracing environmentally sustainable practices.

1.2. Contemporary Mosques

Contemporary mosques have been influenced by modern architecture, altering traditional forms due to Westernization, urban growth, and societal changes. This has created tension between modern design and traditional religious symbolism, resulting in diverse architectural styles [

29]. Contemporary mosque design trends are categorized into vernacularism, modernism, and postmodernism. Vernacularism preserves historical styles, modernism explores new forms, and postmodernism blends historical styles with modern contexts. Debates exist about the necessity of elements like domes and minarets, with some arguing their overestimated spiritual significance and others emphasizing their evolved role in Islamic architecture. These elements are seen as complementary rather than essential, with some schools of thought considering them optional in modern mosque design [

15].

Contemporary mosques have been designed under the effects of dominant architectural approaches and styles throughout the 20th century and the last two decades. The impact of the modern architectural style on these mosques can be examined by tracing the indicators of modern style in contemporary mosques. The main indicators of modern architectural styles are as follows:

- a)

Simplified geometric shapes: Modern architecture often features basic geometric forms like rectangles, squares, and circles. Emphasizing simplicity and abstraction, this style is epitomized by Mies van der Rohe’s slogan “Less is more” [

34]. It rejects traditional aesthetics in favor of innovative creativity, focusing on simplicity, abstraction, and rational solutions to location, purpose, and technological challenges [

35].

- b)

Use of new technology: Modern architecture incorporates materials like steel, glass, and concrete, offering structural flexibility and creative opportunities [

34]. This approach emphasizes the visible use of technology and materials, avoiding unnecessary ornamentation [

35].

- c)

Emphasis on function over form: Modern architecture prioritizes functionality, designing buildings to serve specific purposes. This approach centers on human usability, encapsulated by L. Sullivan’s slogan “Form follows function” [

34].

- d)

Minimalist design: Modern architecture features a minimalist aesthetic with clean lines, simple surfaces, and no ornamentation [

36]. It prioritizes simplicity, pure material colors, and natural textures for decoration. This approach, which is epitomized by Adolf Loos’ slogan “Decoration is a crime”, reflects the Chicago school’s use of cladding for decoration [

34].

- e)

Open floor plans: Modern buildings often feature open floor plans with large, flexible areas for various activities. This style, characterized by the release of external walls from load-bearing functions, allows for a ‘free plan’ where interior walls can be arranged as needed [

35] (pp. 13).

- f)

Emphasis on natural light: Modern buildings often make use of natural light, with large windows and skylights that provide daylight and reduce the need for artificial lighting [

35] (pp. 8).

- g)

Flat roofs: The adoption of flat roofs became a feature of modern architecture, driven by a desire to align architectural form with evolving needs, materials, and industrial techniques [

36].

- h)

Extroverted building: Modern buildings became extroverted, featuring open floor plans and large external windows to align with the extrovert paradigm of modern capital society [

37].

2. Materials and Methods

The research employs a cause-and-effect approach, examining how modern architectural styles influence expected changes (evolution) in mosque designs. To achieve this, the study utilizes the Indicator-based Impact Assessment method, which identifies key variables indicating impacts. This method involves identifying these indicators and assessing their changes within a specific context or case study [

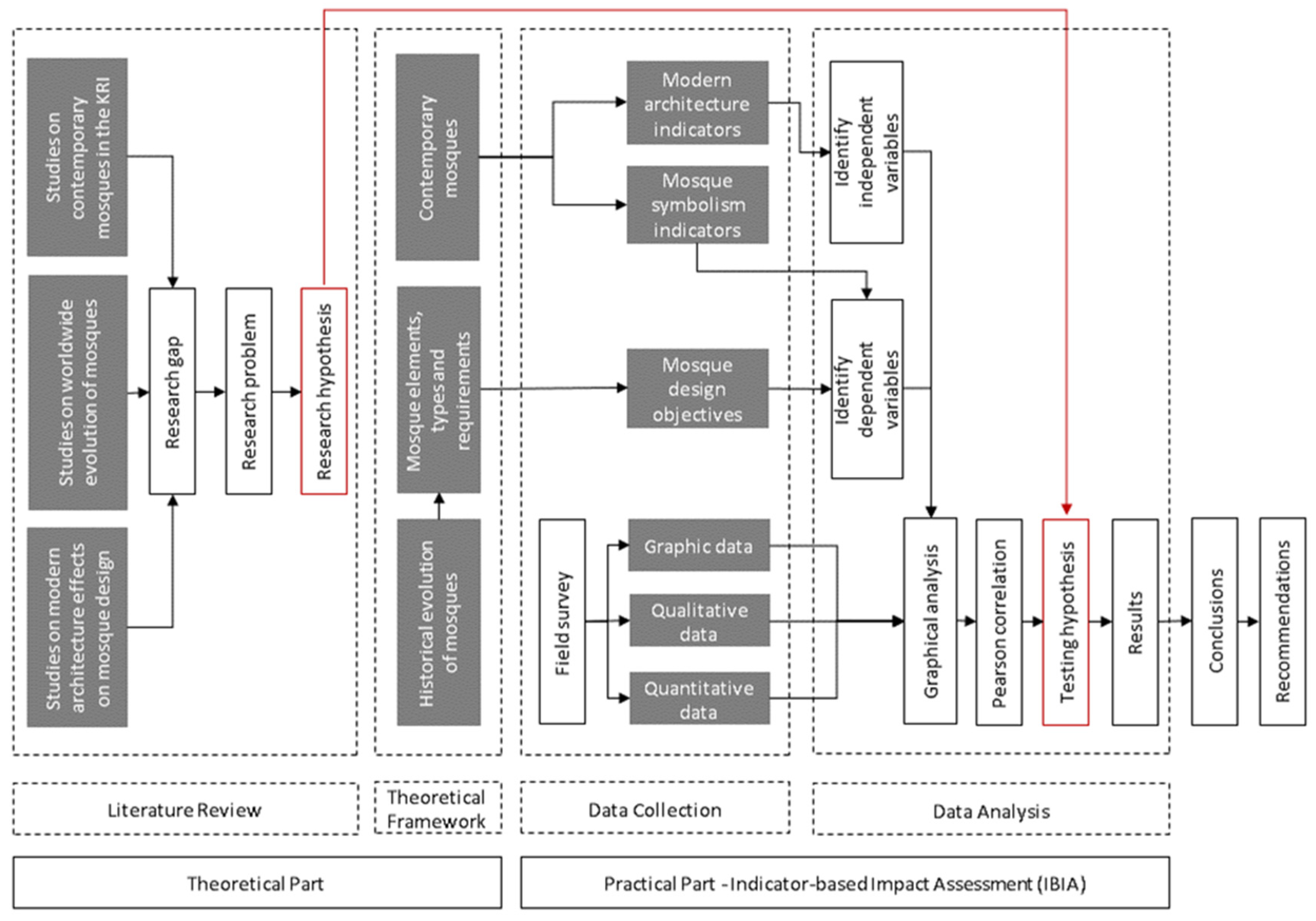

38] (pp. 9). Here, the focus is on the impact of modern architectural styles on the evolution of contemporary mosque design in Sulaymaniyah Governorate. The method is designed to determine whether these impacts align with the desired objectives of mosque design. The study is divided into theoretical and practical parts, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The variables involved in the data analysis are derived from the theoretical part.

To implement this method, certain steps were conducted.

Data collection: A data-sheet was developed for field surveys to gather qualitative, quantitative, and graphic data from 23 selected contemporary mosques constructed within the last three decades, predominantly in Sulaymaniyah. The collected data encompassed information such as location, construction date, architect, geometric properties, floor plans, and photographs, which were subsequently refined and organized.

Based on the previous studies, relevant indicators of modern architectural style for contemporary mosques in Sulaymaniyah were identified. The identified indicators that can be involved in the study are simplified geometric shapes, use of new technology, minimalism, open floor plans, emphasis on natural light, flat roofs, and extroverted design. Then, they were weighted based on the opinion of experts in architecture to gauge the degree of modernity in the selected mosques.

-

Based on Quran, Hadith of Prophet Mohammed (PBOH), and previous studies, key mosque design objectives and requirements were identified in order to be involved in the study. These objectives were specifically aligned with the Sunni Madhab (Shafi’i), reflecting the dominant religious practice in the region. The followings are the objectives and requirements of mosque design that might be affected by modern architecture style:

Avoiding cutting off rows by numerous columns or walls and eliminating view restrictions (expanding the naves)

The use of plan forms that allow for longer rows especially the first row (rectangular shape musalla with long Qibla wall)

Providing a quiet environment for concentration, reverence, and piety during prayer (Tranquility)

Avoiding over-decoration that may interrupt prayers (Reducing Embellishments)

Using the recognizable form as a mosque (Using symbolic mosque elements which are dome, minaret, sahn, arcade, mihrab, minbar, calligraphy, water features, gateway, mosaics and artworks). Then, they were weighted based on opinion of experts in Islamic architecture to ascertain the degree of symbolism in the examined mosques.

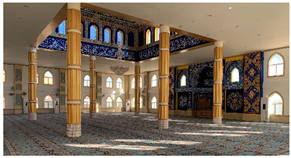

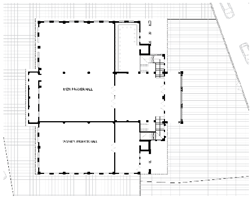

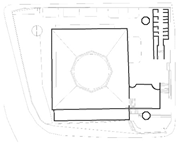

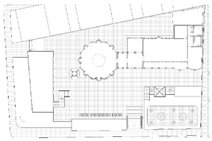

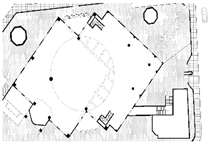

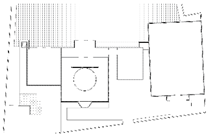

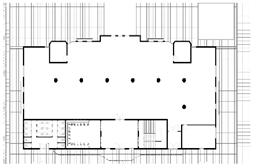

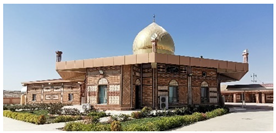

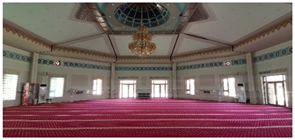

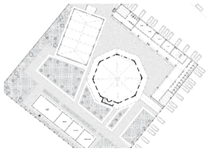

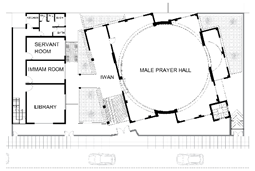

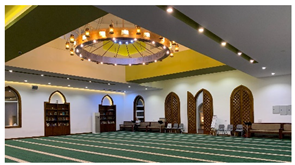

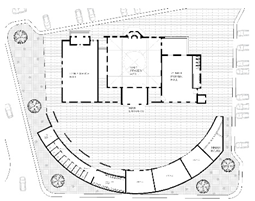

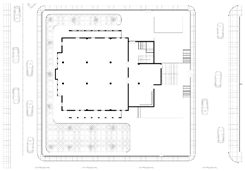

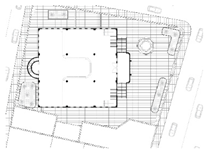

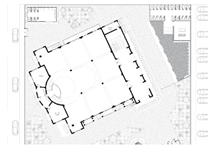

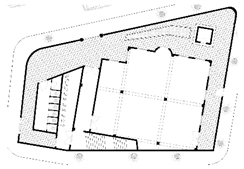

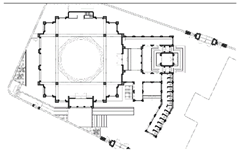

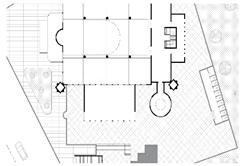

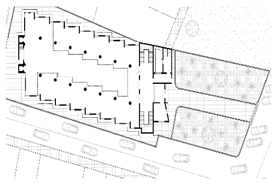

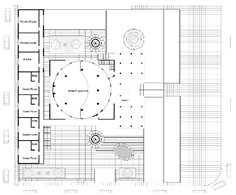

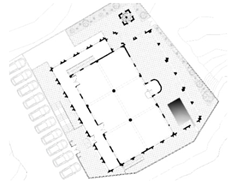

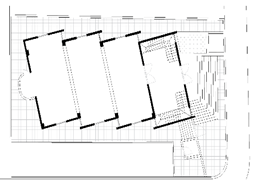

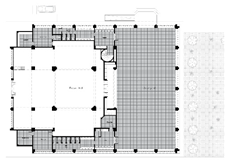

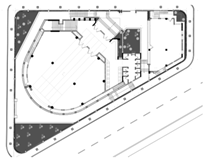

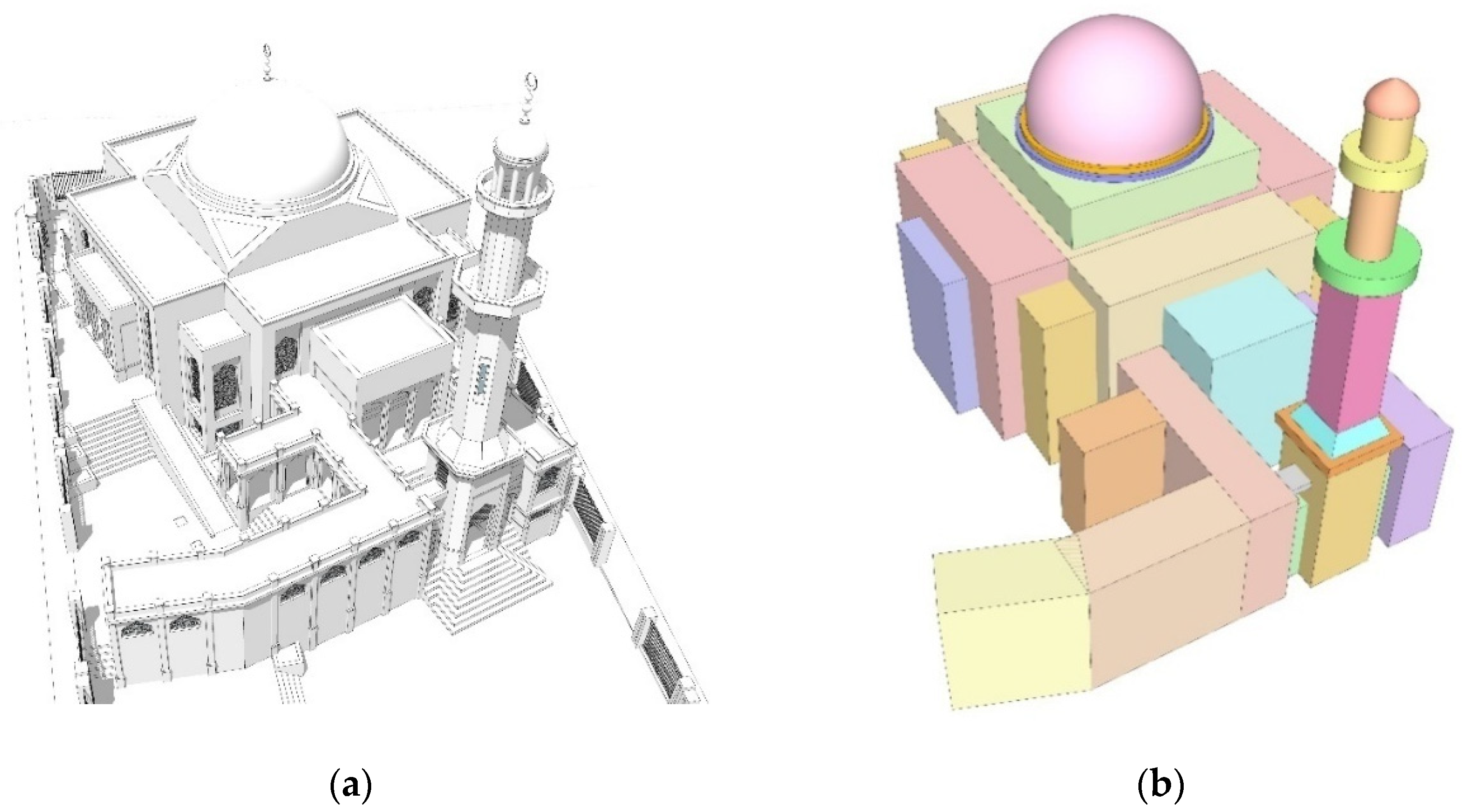

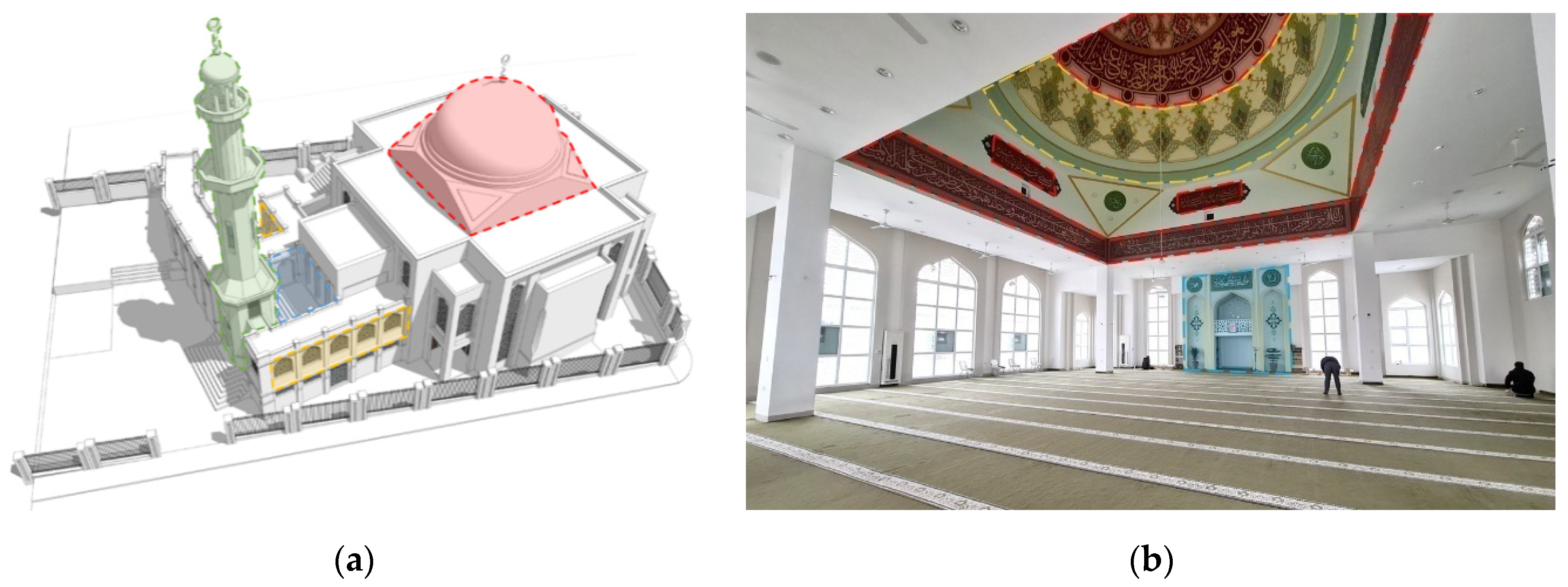

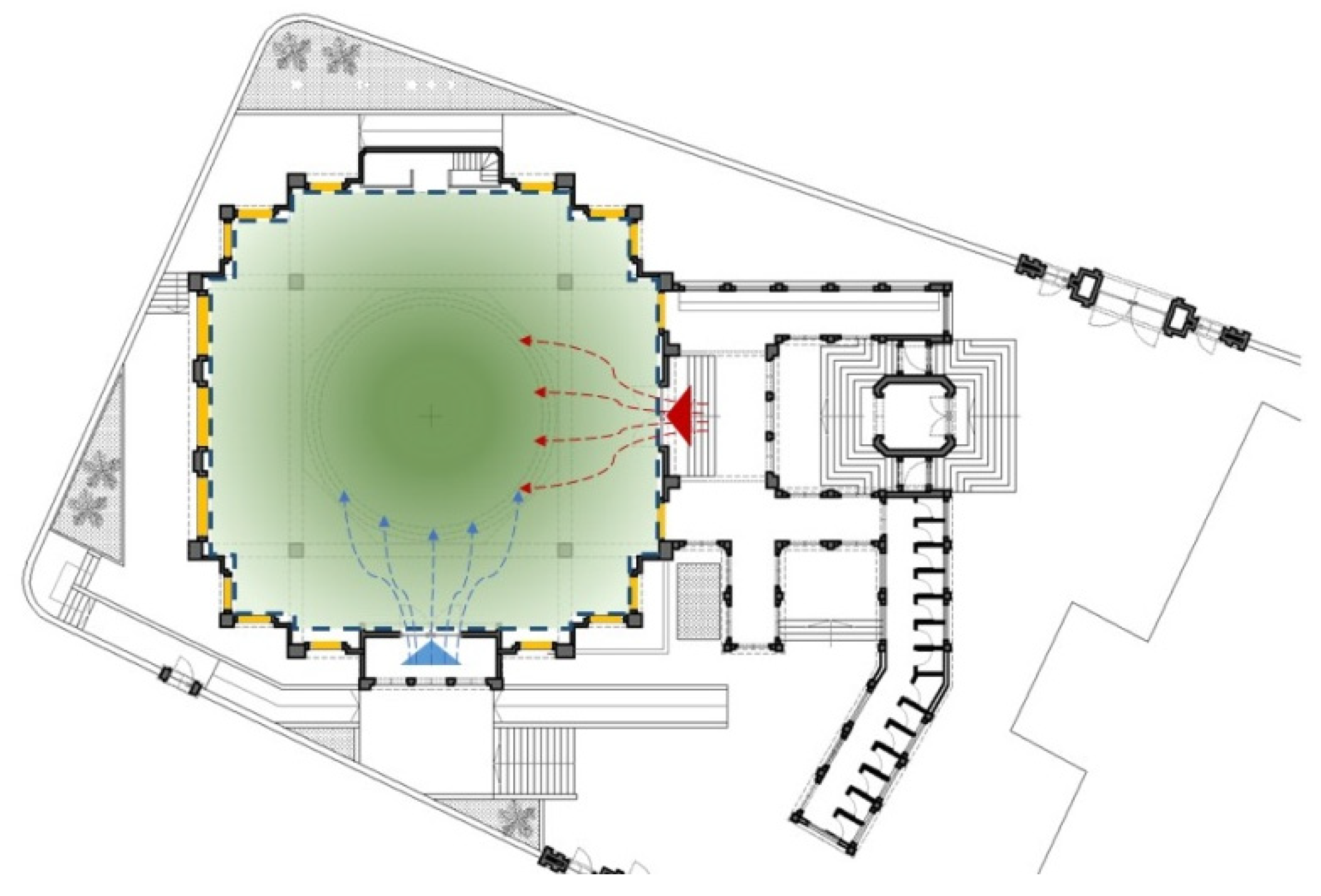

Graphical analysis was used to determine the modernity degree of the mosques based on key indicators of modern architectural style. Specific tools, methods, and equations were employed for each indicator, using checklists for components and geometric calculations where needed. Numerical values were converted to indices using statistical equations to simplify and condense the data, aiding in comparisons and trend identification. Then, the achieved design objectives in the selected mosques were also calculated as numerical indicators and converted to indices. An example of this graphical analysis is illustrated with the Rayyan mosque (

Figure 2).

The basic used formulas to find modern architecture style indicators’ values of a mosques are explained following:

The formula to find the

Simplified Geometric Shapes Index (I

SGS) of a mosque is:

Where:

V is the minimum number of basic volumetric geometric shapes that forms the mosque (

Figure 2). V

MIN is the minimum V value among the selected mosques. V

MAX is the Maximum V value among the selected mosques.

The formula to find the

Using New Technology Index (I

UNT) of a mosque is:

Where:

XSTR is the numerical indicator of using new structures (Concrete and steel) in the construction of the musalla, dome, and minaret(s) of the mosque. 0 ≤XSTR ≤ 3. XIFM is the numerical indicator of using new finishing materials in the internal walls, columns, and ceiling(s) of the mosque. 0 ≤ XIFM ≤ 3. XEFM is the numerical indicator of using new finishing materials in the external walls of musalla, dome(s), and minaret(s) of the mosque. 0 ≤ XEFM ≤ 3. XMAX is the summation of maximum possible X values in a mosque. XMAX = 9

The formula to find the

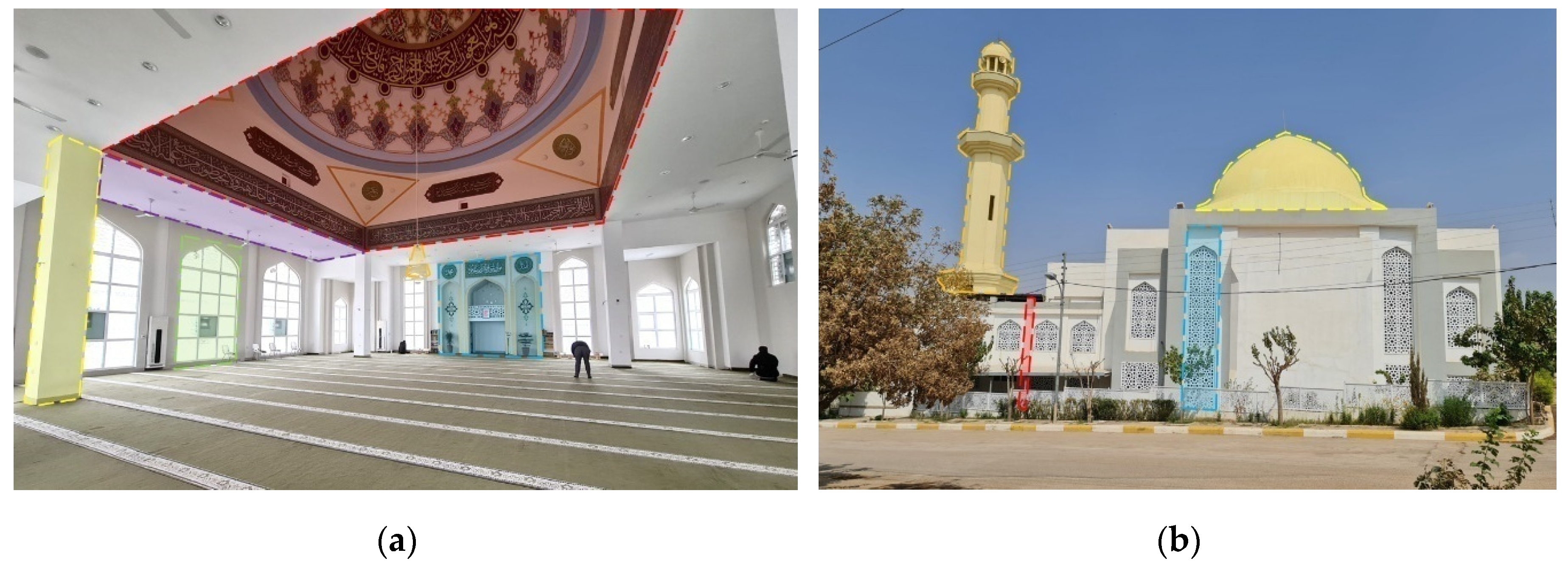

Minimalism Index (

IM) of a mosque is:

Where:

D

INT is a numerical indicator of using interior decoration elements in internal surfaces of mihrab, minbar, dome(s), column(s), ceiling(s), doors, windows, and external surfaces of and having chandelier in the musalla of the mosque (

Figure 3). 0 ≤ D

INT ≤ 2. D

INT = 0 means having no decoration, D

INT = 1 means having medium decoration, and D

INT = 1 means having full decoration. D

EXT is a numerical indicator of using Exterior decoration elements in External surfaces of walls, windows, columns, dome(s), and minaret(s) of the mosque (

Figure 3). 0 ≤ D

EXT ≤ 2. D

EXT = 0 means having no decoration, D

EXT = 1 means having medium decoration, and D

EXT = 1 means having full decoration. D

MAX is the maximum possible D values in a mosque. D

MAX = 26.

The formula to find the

Open Floor Plan Index (I

OFP) of a mosque is:

Where:

NCM is the number of spatially connected musalla in the mosque. NM is the number of musalla in the mosque.

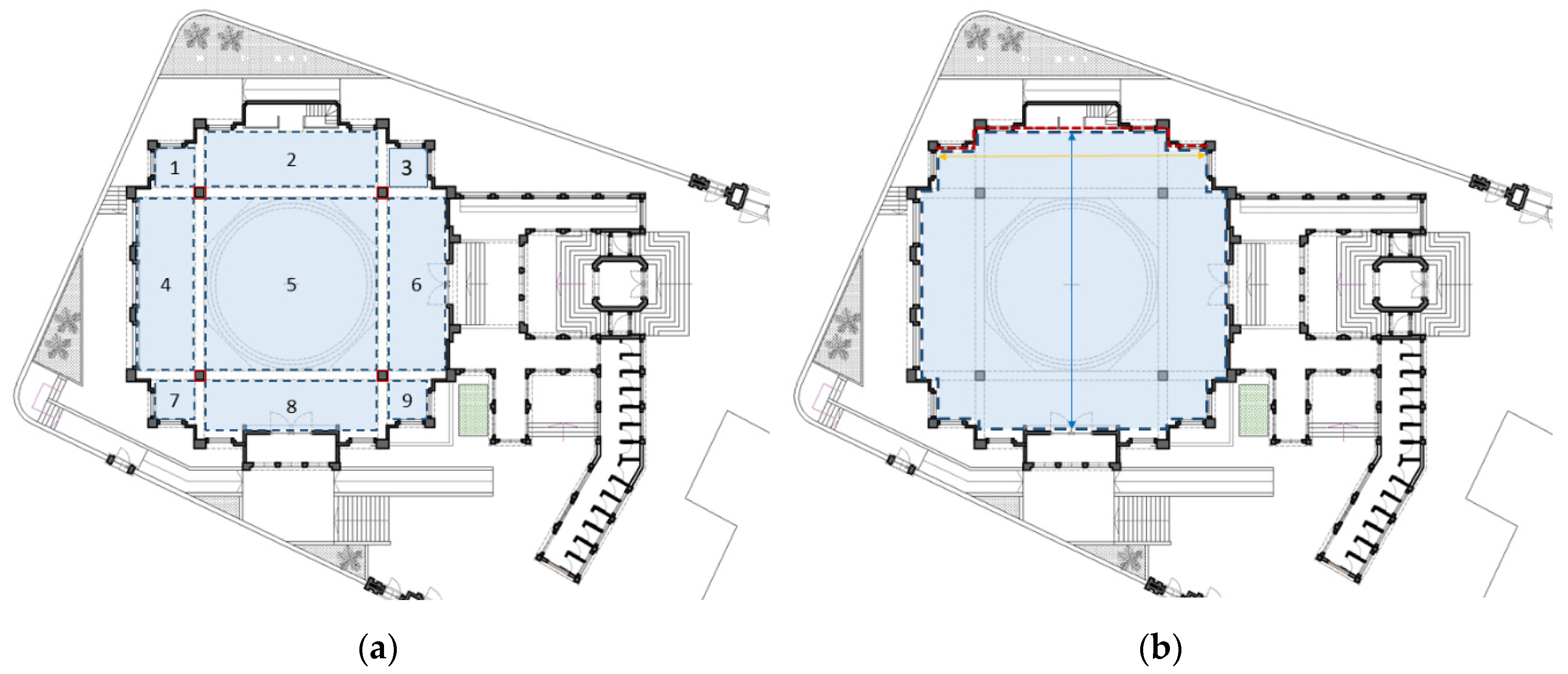

The formula to find the

Emphasis on Natural Lighting Index (I

ENL) of a mosque is:

Where:

R is the ratio of glazing area to floor area in the mosque’s musalla (

Figure 4). A

MG is the glazing area of the mosque’s musalla. A

M is the area of the mosque’s musalla. R

MIN is the minimum R value among the selected mosques. R

MAX is the maximum R value among the selected mosques.

The formula to find the

Flat Roof Index (I

FR) of a mosque is:

Where:

D is a numerical indicator of having dome in the mosque. D = 0 when the mosque has no dome, D = 1 when the mosque has at least a dome. P is a numerical indicator of having pitched roof in the mosque. P = 0 when the mosque has no pitched roof, P = 1 when the mosque has at least a pitched or sloped roof.

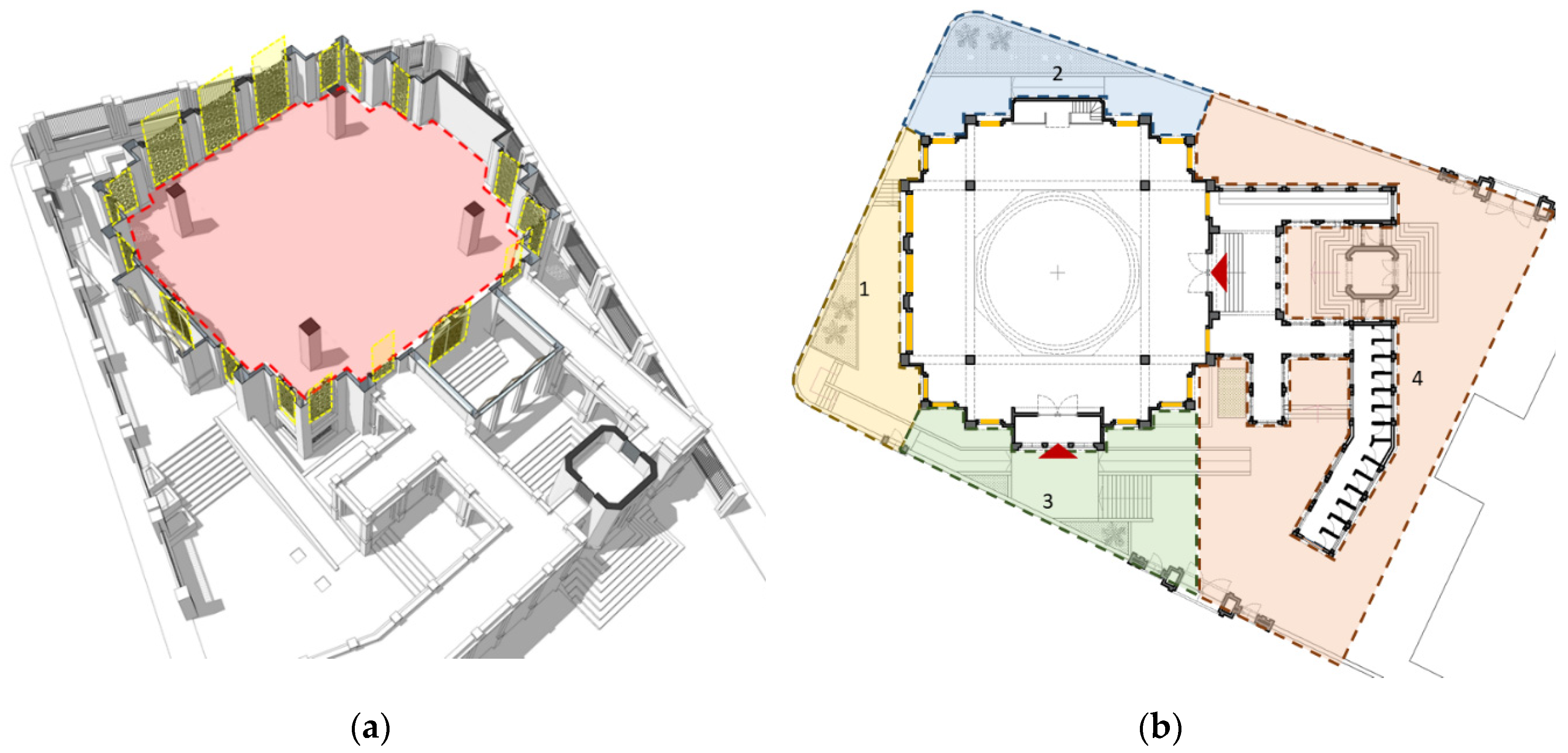

The formula to find the

Extroverted Design Index (I

ED) of a mosque is:

Where:

S is the number of open outdoor spaces surrounding the mosque on four sides (

Figure 4). 0 ≤ S ≤ 4. E is the number of entrances of the mosque’s musalla. 0 ≤ E ≤ 4.

The formula for converting MAS indicators’ values into a

modernity index score (I

MODERN) for a mosque is:

Where:

WSGS is the weight of simplified geometric shapes index = 0.152, WUNT is the weight of using new technology index = 0.176, WM is the weight of minimalism index = 0.168, WOFP is the weight of open floor plan index = 0.16, WENL is the weight of emphasis on natural light index = 0.136, WFR is the weight of flat roof index = 0.08, and WED is the weight of extroverted design index = 0.128.

The formula to find the

Nave Expanding Index (I

NE) of a mosque is:

Where:

Y is the ratio of the musalla area to the number of naves in the musalla of the mosque (

Figure 5). A

M is the area of the musalla. N is the number of the naves in the musalla. Y

MIN is the minimum Y value among the selected mosques. Y

MAX is the maximum Y value among the selected mosques.

The formula to find the

Musalla Proportion Index (I

MP) of a mosque is:

Where:

Z is the ratio of the Qibla wall length and the distance between the Qibla wall and the opposite wall (

Figure 5). L

Q is the Qibla wall length. D is the distance between the Qibla wall and the opposite wall. Z

MIN is the minimum Z value among the selected mosques. Z

MAX is the maximum Z value among the selected mosques.

The formula to find the

Symbolic Elements Index (I

SE) of a mosque is:

Where:

K

DOM, K

MINA, K

SAH, K

ARC, K

MIH, K

MINB, K

CAL, K

WAT, K

GAT, K

ART are numerical indicators of having dome, minaret, sahn, arcade, mihrab, minbar, calligraphy, water features, gateway, and artworks respectively in the mosque. K = 0 when the mosque doesn’t have the relevant symbolic element, K = 1 when the mosque has at least a relevant symbolic element (

Figure 6). W

DOM is the weight of K

DOM indicator = 0.129, W

MINA is the weight of K

MINA indicator = 0.1677, W

SAH is the weight of K

SAH indicator = 0.0839, W

ARC is the weight of K

ARC indicator = 0.0581, W

MIH is the weight of K

MIH indicator = 0.1484, W

MINB is the weight of K

MINB indicator = 0.1484, W

CAL is the weight of K

CAL indicator = 0.0968, W

WAT is the weight of K

WAT indicator = 0.0452, W

GAT is the weight of K

GAT indicator = 0.071, and W

ART is the weight of K

ART indicator = 0.0516.

The formula to find the

Tranquility Index (I

T) of a mosque is:

Where:

I

EI is Entrance Impact Indicator, in which the front and side doors have negative impacts on the tranquility in the musalla (

Figure 7).

The formula to find the

Reducing Embellishments Index (I

RE) of a mosque is:

- 5.

Pearson Correlation Coefficient was used to assess the correlation between mosque design objectives and the impact of modern architecture indicators. The coefficient ranges from -1 (perfect negative correlation) to 1 (perfect positive correlation), with 0 indicating no correlation. The significance level (alpha) is set at 0.1. A p-value less than 0.1 indicates statistical significance, suggesting the null hypothesis can be rejected. A p-value greater than 0.1 indicates no statistical significance, so the null hypothesis is not rejected. The alpha is set at 0.1 due to the limited sample size, as smaller samples are less likely to represent the whole group accurately.

Case Study

The case studies were selected to represent contemporary mosque design in Sulaymaniyah governorate, based on the following criteria:

Contemporary design reflecting modern architectural styles.

Built within the last three decades (1993-2023).

Designed by an architect or architectural firm.

Constructed under the supervision of an engineer.

Building area between 300m² to 3,000m².

Musalla area between 150m² to 1,500m².

The 23 selected mosques are mainly in Sulaymaniyah, Halabja, and Kalar. Five mosques (21.74%) were built before 2003, eight (34.78%) between 2004 and 2013, and ten (43.48%) between 2014 and 2023. Most mosques from the 1990s lack architectural value due to internal conflicts and economic blockades.

The research faced several limitations. Access to architectural data was challenging, with many original mosque drawings lost, necessitating redrawing by the research. Potential discrepancies between design and actual construction introduced errors in architectural data, though efforts were made to correct these inaccuracies.

3. Results and Discussions

The statistical analysis assessed the impact of modern architectural style indicators on contemporary mosque design in Sulaymaniyah Governorate. The degree of impact was determined by the presence or absence of each indicator in the mosques. A correlation analysis was then conducted to evaluate the statistical relationship between the indicators and their impact.

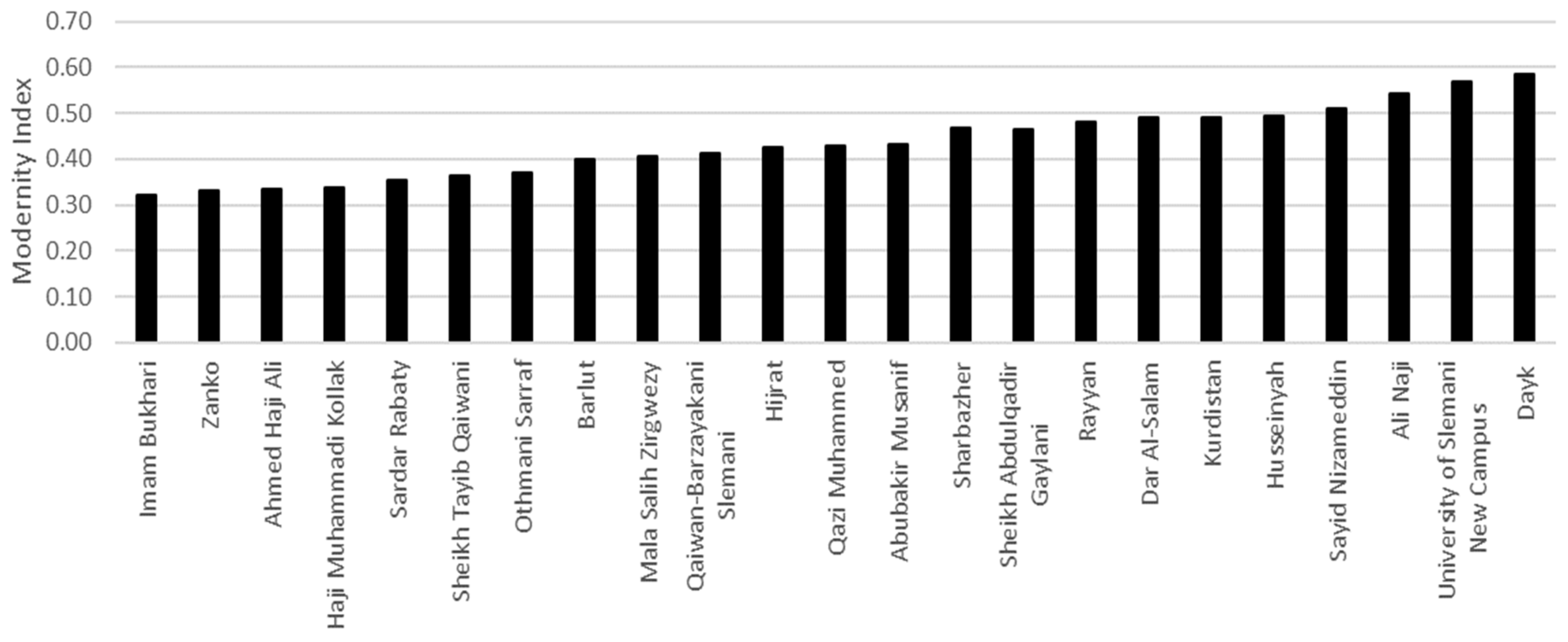

Figure 8 shows the modernity indices for the selected mosques, with values ranging from 0.32 to 0.59. Mosques like Imam Bukhari, Zanko, Ahmed Haji Ali, Haji Muhammadi Kollak, and Sardar Rabaty have lower indices (0.32-0.35). Indices increase with mosques such as Sheikh Tayib Qaiwani, Othmani Sarraf, and Barlut (0.37-0.40). Mosques like Mala Salih Zirgwezy, Qaiwan-Barzayakani Slemani, and Hijrat fall in the 0.41-0.43 range. Higher indices (0.43-0.49) are seen in Abubakir Musanif, Sharbazher, Sheikh Abdulqadir Gaylani, Rayyan, Dar Al-Salam, Kurdistan, and Hussainiya. Sayid Nizameddin, Ali Naji, University of Slemani New Campus, and Dayk exhibit the highest indices (0.51-0.59). These highlight diverse modernity levels among the mosques.

The small range of modernity indices (0.32 to 0.59) among the mosques likely stems from their shared contemporary nature. This coherence in modernity levels reflects the influence of common architectural trends and principles, as well as the fact that these mosques were built within a relatively short time frame. The consistent and contemporaneous architectural approach suggests a unified contemporary style guiding their construction, leading to a more uniform distribution of Modernity Indices.

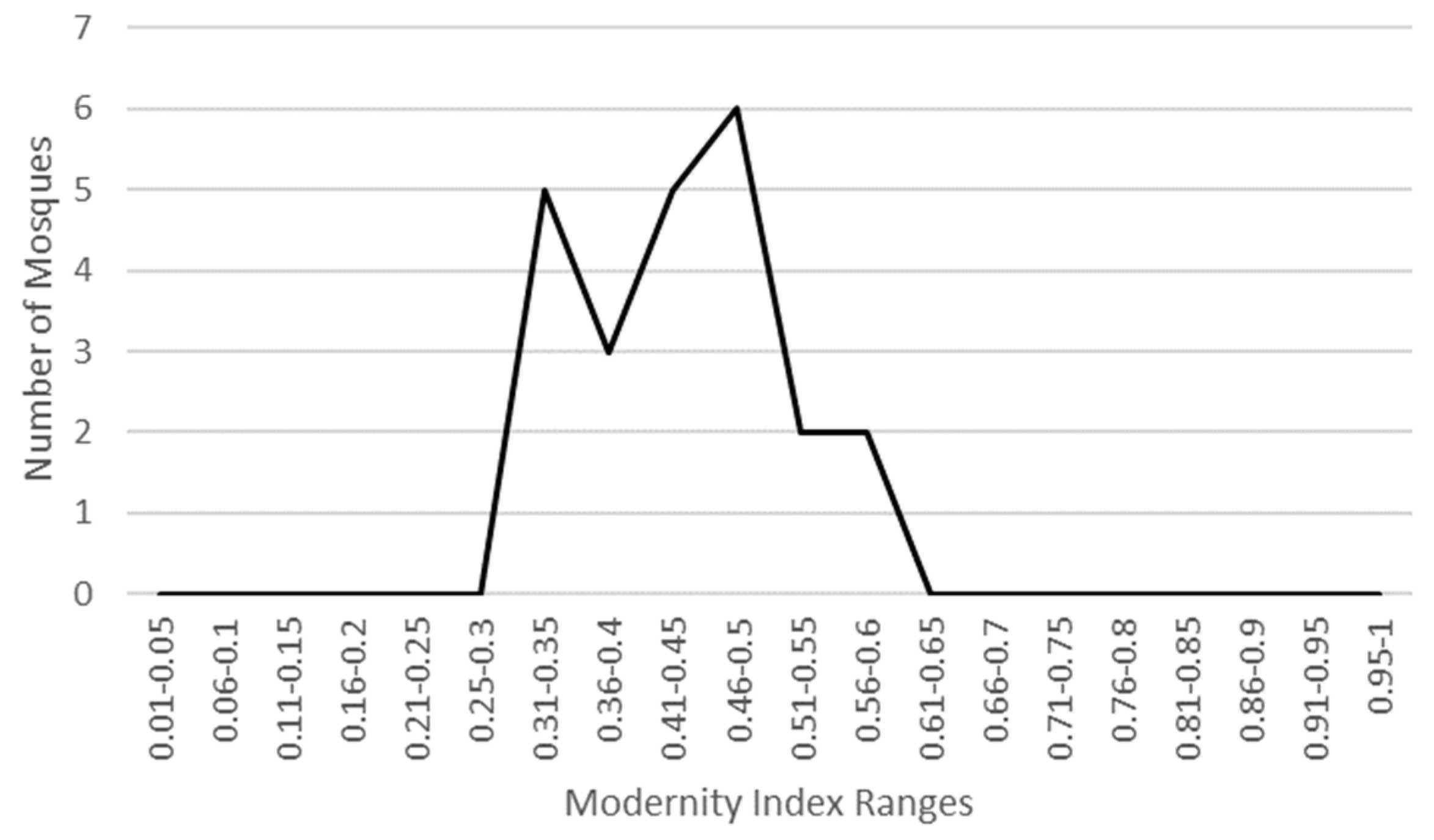

The frequency distribution of mosques based on their Modernity Index, which is presented in (

Figure 9), shows concentrations between 0.31 and 0.5. Frequencies decrease beyond a Modernity Index of 0.5, and no mosques fall below 0.31 or above 0.6. These indicate the distribution of modernity levels across the sampled mosques.

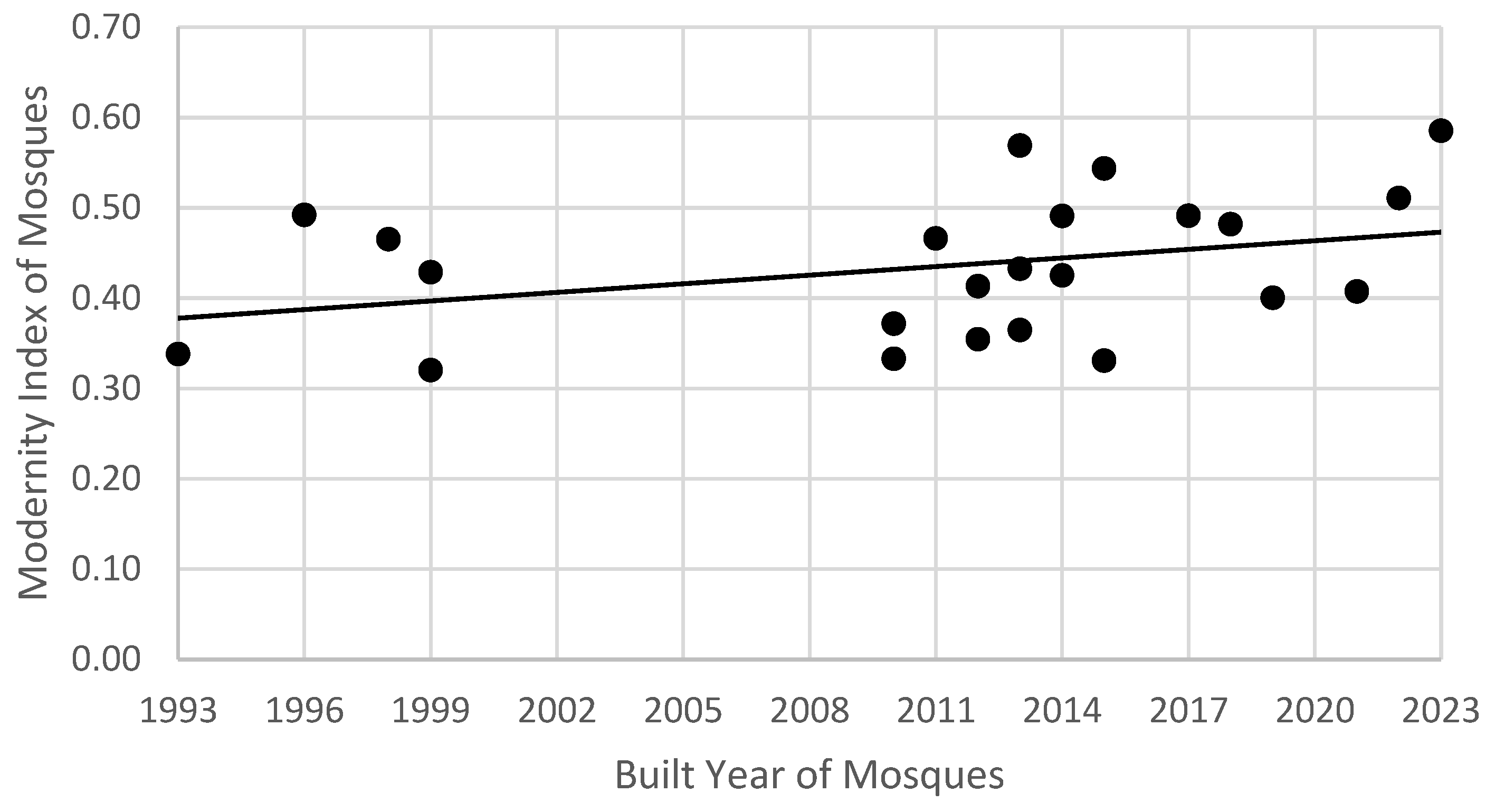

Figure 10 illustrates the correlation between the construction year of mosques and their corresponding Modernity Indices. Spanning from 1993 to 2023, the built years of the mosques do not strictly correlate linearly with their modernity indices. For example, Imam Bukhari, constructed in 1999, shows a Modernity Index of 0.32, lower than more recent mosques like University of Slemani New Campus (2013, Index = 0.57) and Dayk (2023, Index = 0.59). Conversely, mosques such as Sheikh Abdulqadir Gailani (1998, Index = 0.47) and Qazi Muhammed (1999, Index = 0.43) have higher Modernity Indices relative to their construction years. This suggests that factors beyond construction date, such as adherence to traditional styles, significantly influence the Modernity Index. The correlation reflects a blend of temporal and stylistic factors rather than a straightforward linear relationship with construction year alone.

Here are the correlation results between mosque design objectives and modern architecture indicators:

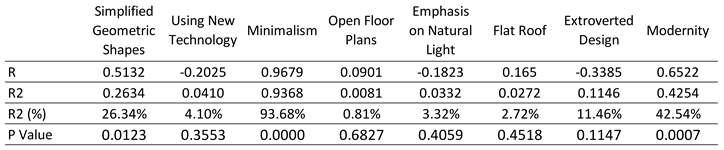

The mosque design objectives are Nave Expanding, Acceptable Musalla Proportion, Using Symbolic Elements, Tranquility in Musalla, and Reducing Embellishments. While, the modern architecture indicators include Simplified Geometric Shapes, Using New Technology, Minimalism, Open Floor Plans, Emphasis on Natural Light, Flat Roof, and Extroverted Design. The coefficients are accompanied by their respective R-squared (R²) values, indicating the proportion of variance explained, as well as the percentage of variance explained (R² %), and the p-values representing the significance of the correlations at a significance level of 0.1.

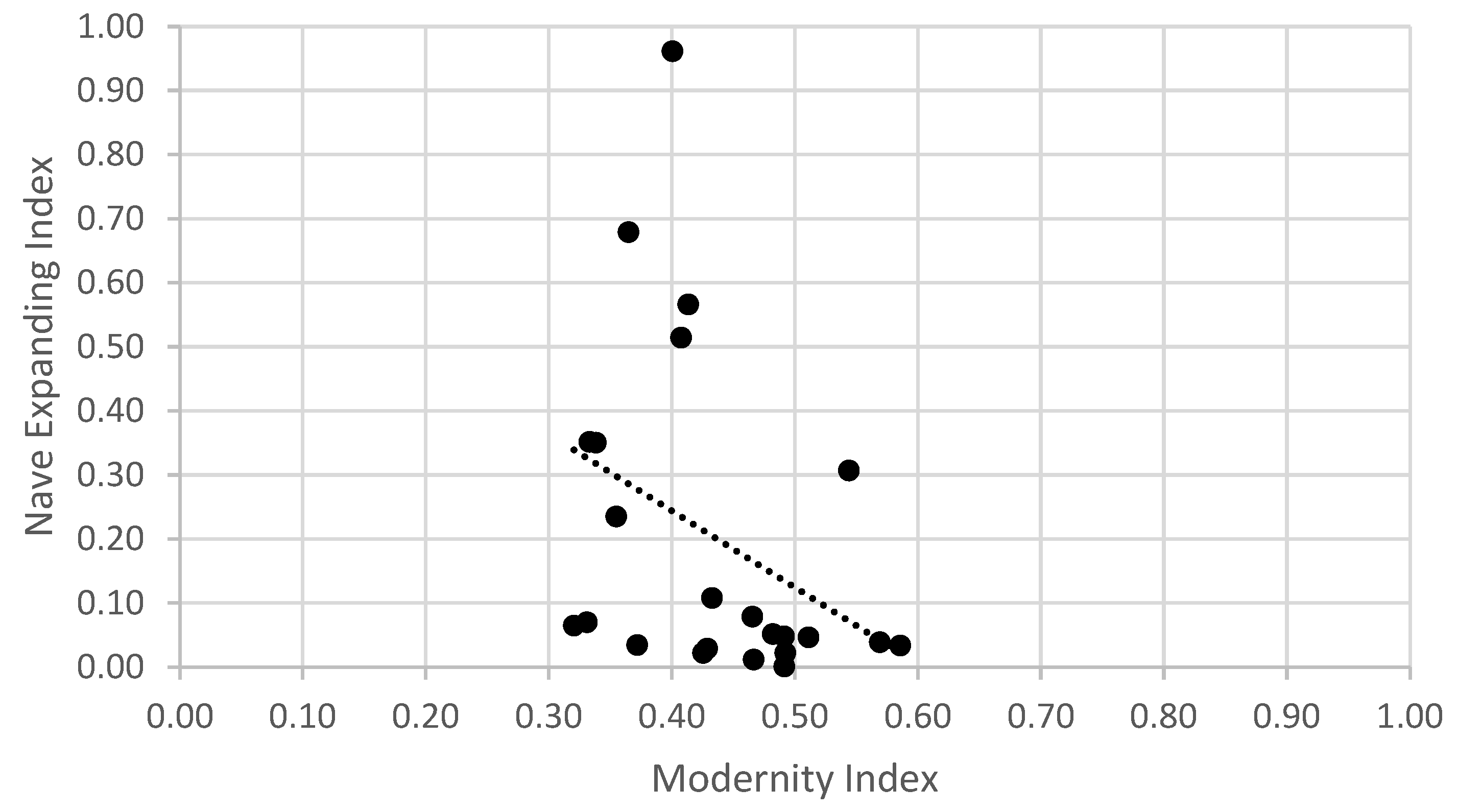

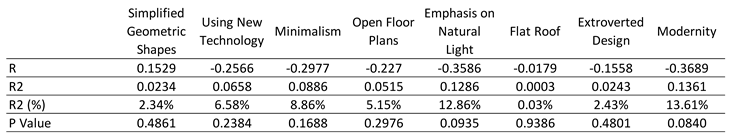

Table 1 and

Figure 11 present the correlations between the Nave Expanding Index and the Indices of Modern Architecture Indicators and Modernity Index as well. The correlations are generally weak, as indicated by the low R-squared values and percentages of variance explained. Among the individual indicators, the Nave Expanding Index shows a slight positive correlation with Simplified Geometric Shapes (R = 0.1529) but negative correlations with Using New Technology, Minimalism, Open Floor Plans, Emphasis on Natural Light, Flat Roof, and Extroverted Design. However, none of these correlations are statistically significant at the 0.1 significance level, as indicated by the p-values above 0.1, except in the Index of Emphasis on Natural Light. The overall Modernity Index also exhibits a negative correlation with the Nave Expanding Index (R = -0.3689), and this correlation approaches statistical significance (p-value = 0.0840). Overall, while some weak correlations are observed, the data suggests that the Nave Expanding Index is not strongly associated with the selected modern architecture indicators and the modernity degree of the mosques.

The weak correlations suggest that other factors or design considerations may have a more influential role in determining the size of naves in the mosques under consideration. There are several additional factors that can contribute to the alteration of the mosque’s interior dimensions. The needs of the local Muslim community, particularly in larger communities, play a crucial role in influencing the dimensions and layout of the mosque’s interior, emphasizing the importance of accommodating varying congregation sizes. Such as Ahmed Haji Ali Mosque and Kurdistan Mosque. In addition, urban planning considerations, especially in densely populated areas with space constraints, may lead to creative solutions for musalla dimensions. Such as mosques of Ali Naji, Dar Alsalam, Mala Salih Zirgwezi, and Sardar Rabati (Annex 1). Furthermore, the integration of technology within mosque spaces, including audio-visual aids and modern amenities, further influences interior layouts to meet contemporary needs. Moreover, community engagement and input in the design process contribute to a more tailored interior design, reflecting the preferences and requirements of the local community. Additionally, adherence to government regulations, building codes, and zoning requirements plays a significant role in shaping mosque design, including decisions related to interior dimensions.

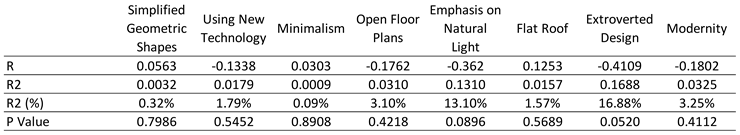

Table 2 shows the correlations between the acceptable proportion of mosques’ musalla and the modern architecture indicators. These correlations are generally weak, as evidenced by the low R-squared values and percentages of variance explained. Among the individual indicators, there are negative correlations with Emphasis on Natural Light (R = -0.362) and Extroverted Design (R = -0.4109). The rest of the correlations aren’t statistically significant at the 0.1 significance level, as indicated by the p-values being above 0.1. There is a very weak positive correlation with Flat Roof Design (R = 0.1253) and a very weak negative correlation with Open Floor Plans (R = -0.1762). The overall Modernity Index also exhibits a weak negative correlation with the proportion of mosques’ musalla (R = -0.1802). Overall, the data suggests that the acceptable proportion of mosques’ musalla has a limited and non-significant association with the selected modern architecture indicators and the modernity degree of the mosques.

The negative effects of Emphasis on Natural Light and the Extroverted design is due to the fact that an extroverted design with an emphasis on natural light often involves features like large windows, courtyards, or open spaces that allow for flexibility in the layout of the musalla. This flexibility enables architects to design a prayer hall that accommodates varying proportions while maintaining a sense of openness and connection to the external environment, and increasing natural lighting as well. Furthermore, the weak correlations between the acceptable proportion of mosques’ musalla and the modern architecture indicators of the mosques indicate that alterations or fluctuations in the musalla proportion are not solely connected to changes in the selected measures of architectural modernity. These correlations point to the likelihood that other factors or design considerations play a more influential role in determining the musalla proportion within the mosques under examination. Urban planning constraints and direction of qibla, particularly in densely populated urban settings, significantly impact the allowable size and shape of musalla, necessitating creative design solutions to optimize available space, as evident in mosques like Dayk, Ali Naji, Dar Al-Salam, Mala Salih Zirgwezi, Sardar Rabati, Sharbazher, and Imam Bukhari. In addition, the size of the community and the users of the mosque influence the musalla proportions, with larger communities requiring more extensive prayer spaces and ignoring the shape and proportion of the musalla. Such as Ahmed Haji Ali Mosque and Kurdistan Mosque which serve larger communities. Aesthetic preferences, as seen in Hussainiya Mosque and Rayyan Mosque, may also play a role, with some communities seeking a balance between aesthetics and functionality (Annex 1). Furthermore, community engagement in decision-making fosters a tailored approach, reflecting congregants’ preferences which affect the musalla shape too. Moreover, adherence to government regulations and building codes, particularly those related to the reduction distances, open areas, and green spaces, impacts musalla proportions in mosques as well.

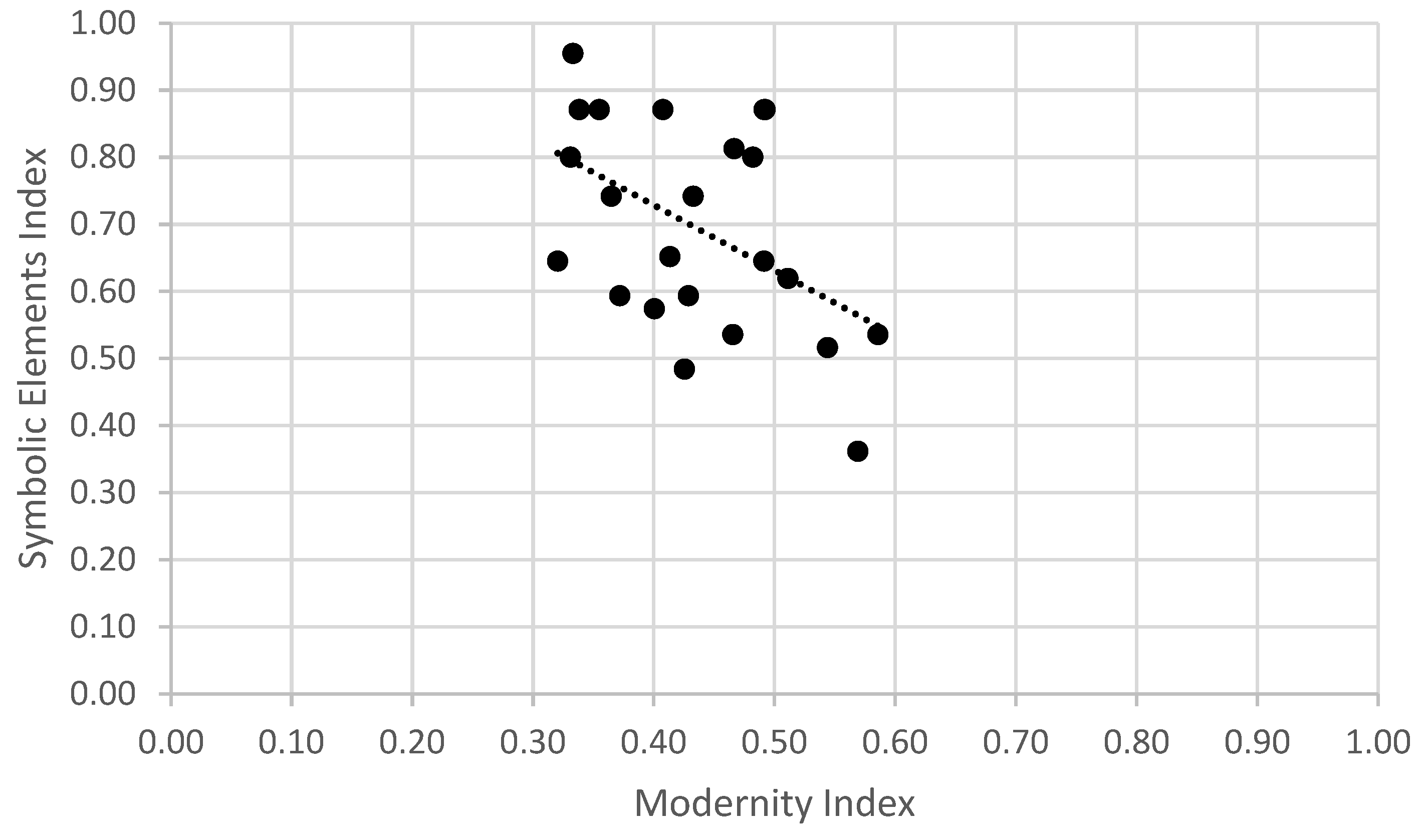

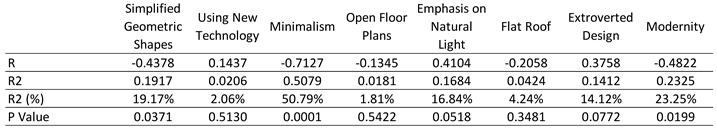

The correlation between the symbolism index of mosques and the modern architecture indicators is notably strong and statistically significant for several factors (

Table 3 and

Figure 12). There is a substantial negative correlation with Simplified Geometric Shapes (R = -0.4378), indicating that as the use of simplified geometric shapes increases, the symbolism index tends to decrease. In addition, there is a significant negative correlation with Minimalism (R = -0.7127), suggesting that mosques with a higher Minimalism index are more likely to exhibit symbolic design elements. The overall Modernity Index also shows a strong negative correlation with the symbolism index (R = -0.4822), signifying that mosques with greater modernity index tend to have lower symbolism index. The p-values for these correlations are below the 0.1 significance level, indicating statistical significance.

Conversely, the correlation between the symbolism index and the use of new technology in mosque design is weak and non-significant. While a slight positive trend suggests higher symbolism in mosques with new technology, it lacks statistical significance. Similarly, the correlation between the symbolism index and open floor plans in mosques is weak and non-significant, indicating a minor tendency for closed floor plan mosques to have fewer symbolic elements without statistical robustness. The correlation between the symbolism index and emphasis on natural light in mosques is strong and positive, indicating that mosques emphasizing natural light tend to incorporate more symbolism. However, the correlation between the symbolism index and flat roofs in mosques is weak and non-significant, showing a minor tendency for flat-roof mosques to have more symbolic features. Moreover, the correlation between the symbolism index and extroverted design in mosques is strong and positive, suggesting mosques with extroverted designs may exhibit higher symbolism degrees.

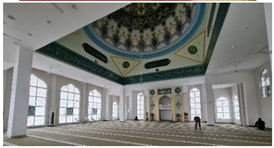

The notable and statistically significant correlations between the symbolism index of mosques and various modern architecture indicators provide insights into the intricate dynamics of contemporary mosque design. Strong negative correlations with Simplified Geometric Shapes, Minimalism, and the overall Modernity Index, indicate that as these indices decrease, symbolic features tend to increase. This is clearly seen in the mosques of Ahmed Haji Ali, Haji Muhammadi Kollak, Sardar Rabaty and Zanko. From a mystical perspective, these correlations, which lead to fewer symbolic features in mosque design, suggest a shift towards a more minimalistic aesthetic, where elaborate symbolism takes a backseat to clean, modern designs. This reflects an evolving approach to spiritual representation in mosque architecture, emphasizing simplicity over ornate decoration. Conversely, there’s a positive tendency for mosques with a higher emphasis on natural light to have more symbolic features. The examples provided, such as Dar Al-Salam Mosque, Hussainiya, and Rayyan Mosque, exemplify this trend by showcasing how mosques with a greater emphasis on natural light tend to have a higher prevalence of symbolic features (Annex 1). This correlation suggests that the design choice to prioritize natural lighting may be associated with a deliberate intention to create a spiritually and aesthetically enriching environment through the incorporation of symbolic elements within the mosque architecture. The findings suggest a nuanced interplay between symbolism and specific modern architectural attributes, highlighting the multifaceted nature of mosque design considerations. These insights contribute to a deeper understanding of the complex relationship between symbolism and contemporary architectural elements in mosque design.

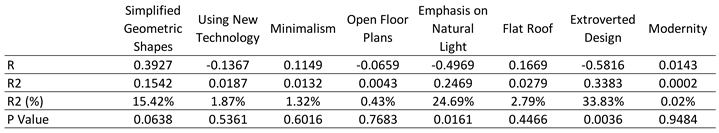

Table 4 highlights correlations between the tranquility index in mosque musallas and their Modernity Index, as well as modern architectural indicators. Notable findings include a strong negative correlation with Extroverted Design (R = -0.5816) and Emphasis on Natural Light (R = -0.4969), suggesting these features reduce tranquility. Conversely, Simplified Geometric Shapes positively correlate with tranquility (R = 0.3927). Correlations with Minimalism, Flat Roof, and Modernity Index are positive but not statistically significant. Weak and insignificant correlations are also found with the use of new technology and open floor plans. These findings reveal the complex relationship between tranquility and design elements in contemporary mosque architecture.

These diverse relationships suggest nuanced relationships with implications for architectural, spatial, and psychological interpretations. The strong negative correlation between the tranquility index and Extroverted Design suggests that mosques with more extroverted architectural features, such as large open spaces or bold external facades, may prioritize visual impact over creating tranquil environments such as mosques of Dayk, Hussainiya and Sardar Rabaty. Conversely, the positive correlation with Simplified Geometric Shapes indicates that mosques employing simple and harmonious geometric forms may evoke a sense of calmness and serenity such as mosques of University of Sulaimani, Ali Naji and Sayid Nizameddin. These architectural choices reflect a deliberate effort by designers to shape the spatial experience within the mosque, with implications for worshippers’ psychological well-being. From the spatial point of view, the significant negative correlation with Emphasis on Natural Light implies that mosques perceived as tranquil tend to limit the use of natural lighting, possibly to create a more subdued and intimate atmosphere such as the mosques of Ahmed Haji Ali, Othmani Sarraf and Qaiwan-Barzayakani Slemani. This suggests that designers may opt for controlled lighting conditions, such as diffused or indirect lighting, to foster a sense of tranquility within the prayer space. Additionally, the weak correlations with Open Floor Plans suggest that mosques designed with more enclosed or compartmentalized spaces may be associated with greater tranquility, as these layouts provide a sense of enclosure and privacy conducive to contemplation and prayer such as Haji Muhammadi Kollak Mosque and Zanko Mosque (Annex 1). In addition, the findings suggest that architectural features play a crucial role in shaping the psychological experience of worshippers within mosque environments. For instance, the negative correlation with Extroverted Design implies that mosques with more visually stimulating and outward-oriented designs may evoke a sense of restlessness or distraction, potentially hindering worshippers’ ability to attain a state of inner calmness. Conversely, the positive correlation with Simplified Geometric Shapes suggests that mosques characterized by simplicity and orderliness may facilitate a sense of mental clarity and tranquility, enhancing the overall spiritual experience for worshippers.

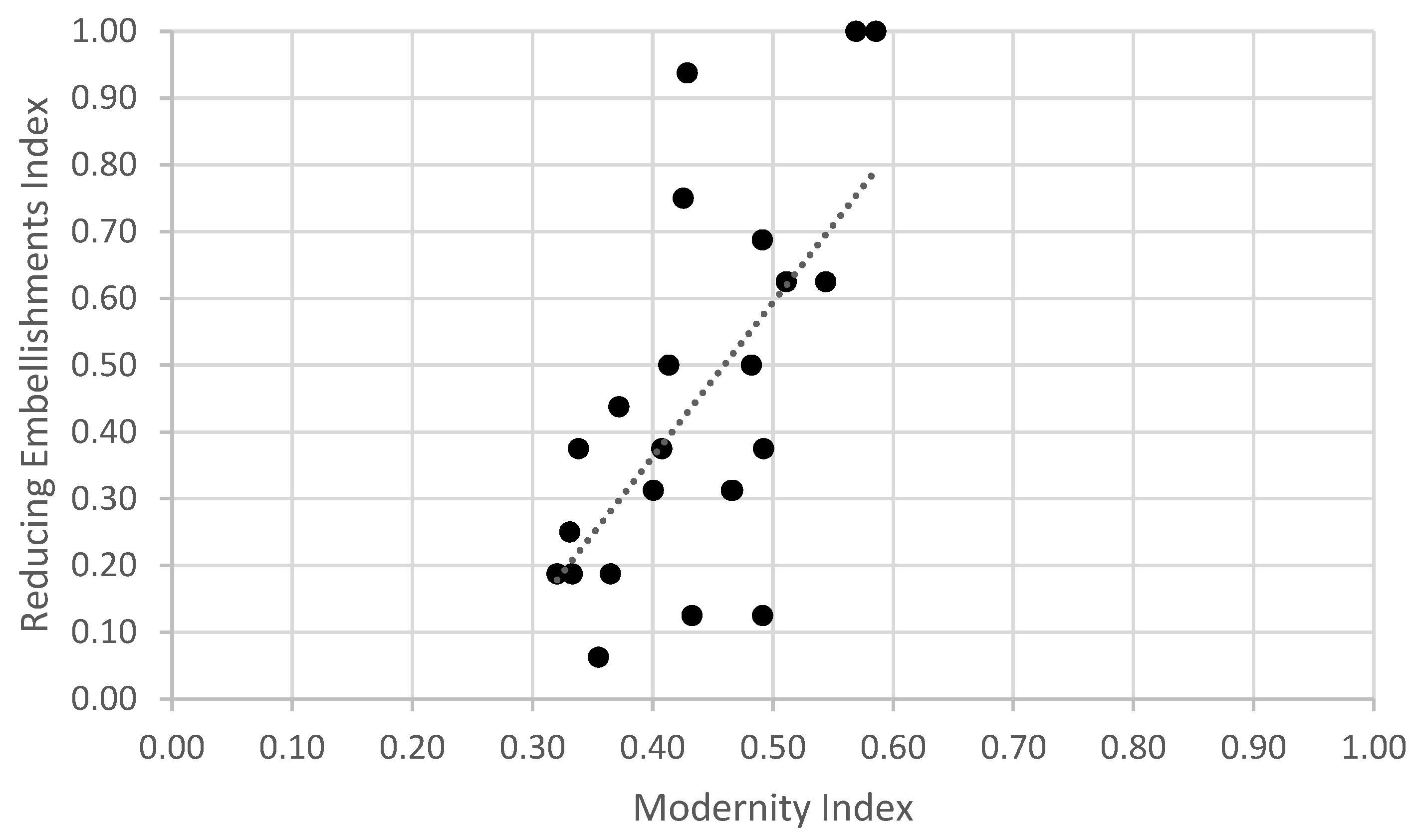

The regression analysis reveals key insights into factors influencing the reduction of embellishments in mosque design (

Table 5). Simplified Geometric Shapes show a positive correlation with reduced ornamentation (R = 0.5132). Minimalism stands out with a very strong positive correlation (R = 0.9679), indicating its significant impact. The Modernity Index also correlates positively (R = 0.6522), linking higher modernity with fewer embellishments. Other indicators, like Using New Technology, Open Floor Plans, Emphasis on Natural Light, Flat Roof, and Extroverted Design, show weak or insignificant correlations, suggesting a more complex or minimal impact.

The positive correlation between the use of Simplified Geometric Shapes and the reduction of embellishments suggests an aesthetic preference for clean lines and geometric simplicity, resulting in a visually uncluttered and harmonious architectural composition within mosque interiors. Furthermore, the dominance of Minimalism as a significant factor underscores the profound influence of minimalist design principles on aesthetic decision-making, emphasizing the importance of simplicity, clarity, and restraint in achieving a refined and elegant aesthetic expression. Similarly, the strong positive correlation with the Modernity Index indicates a shift towards contemporary design sensibilities, characterized by a deliberate reduction of traditional ornamentation in favor of a more streamlined and contemporary aesthetic language. The best examples for these positive correlations area the mosques of University of Sulaimani, Dayk, Ali Naji and Sayid Nizameddin (Annex 1). While correlations with other modern architectural features such as Using New Technology, Open Floor Plans, Emphasis on Natural Light, Flat Roof, and Extroverted Design are less pronounced, they suggest a more nuanced relationship between modern design features and the visual simplicity of mosque interiors, contributing to a richer understanding of the aesthetic dynamics shaping contemporary mosque architecture.

4. Conclusions

This study makes a contribution to the architectural research by aligning mosque design objectives with Shari’ah and examining how contemporary architectural styles influenced these objectives, particularly in the Sulaymaniyah region. It uniquely quantifies these objectives within a religious framework, filling a gap in existing literature. This approach offers practical insights for maintaining the spiritual and functional integrity of mosques, enriching both academic discourse and practical architectural design in the Islamic world.

In general, modern architectural styles have negatively influenced the expansion of the nave sizes of musalla, mainly because of the emphasis on natural light, which is a dominant feature in modern styles. However, other factors, such as community needs, urban planning constraints, and government regulations, should always play pivotal roles in determining mosque interior dimensions.

The influence of modern architecture style indicators on the acceptable proportions of musalla is evident but is not significant except for the effect of emphasis on natural light and extroverted design which is a negative and relatively weak effect. In general, the modern style effects on the acceptable proportions of musalla are not significant. It is assumed that urban planning constraints, community size, aesthetic preferences, and adherence to regulations significantly shape musalla dimensions, highlighting the nuanced considerations in mosque design.

The overall influence of modern architecture style on the symbolism of the mosques is strong but negative. This negative effect is mainly due to the effects of both modern style features which are using simplified geometric shapes, and minimalism. Although, the influences of the features like emphasis on natural light and extroverted design are positive, compared to the rest are not considered.

The overall effects of the modern architecture style on the tranquility in the musalla are not significant. Although using simplified geometric shapes, as a modern style feature, positively affected the tranquility, it is eliminated due to the negative effects of the emphasis on natural light and extroverted design.

Generally, the influence of modern architecture style on reduction of the embellishments in mosques is strong and positive. This influence is mainly due to the effects of both modern style features which are using simplified geometric shapes, and minimalism.

In conclusion, the modern architecture style significantly contributes to the reduction of embellishments in mosque design, but negatively affects the expanding of naves in the musalla and the symbolism of mosques. Furthermore, its impact on other objectives such as the acceptable proportion of musalla and the tranquility within the musalla is relatively insignificant. Thus, the overall influence of the modern style tends to be more negative on the evolution of mosques. It is recommended that those involved in designing contemporary mosques prioritize the integration of modern styles’ features that positively influence the achievement of mosque design objectives.