Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

19 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Backround

3. System Model

3.1. State Equation

3.2. Measurement Model

3.3. Considering Unstable Contact and Slipping

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

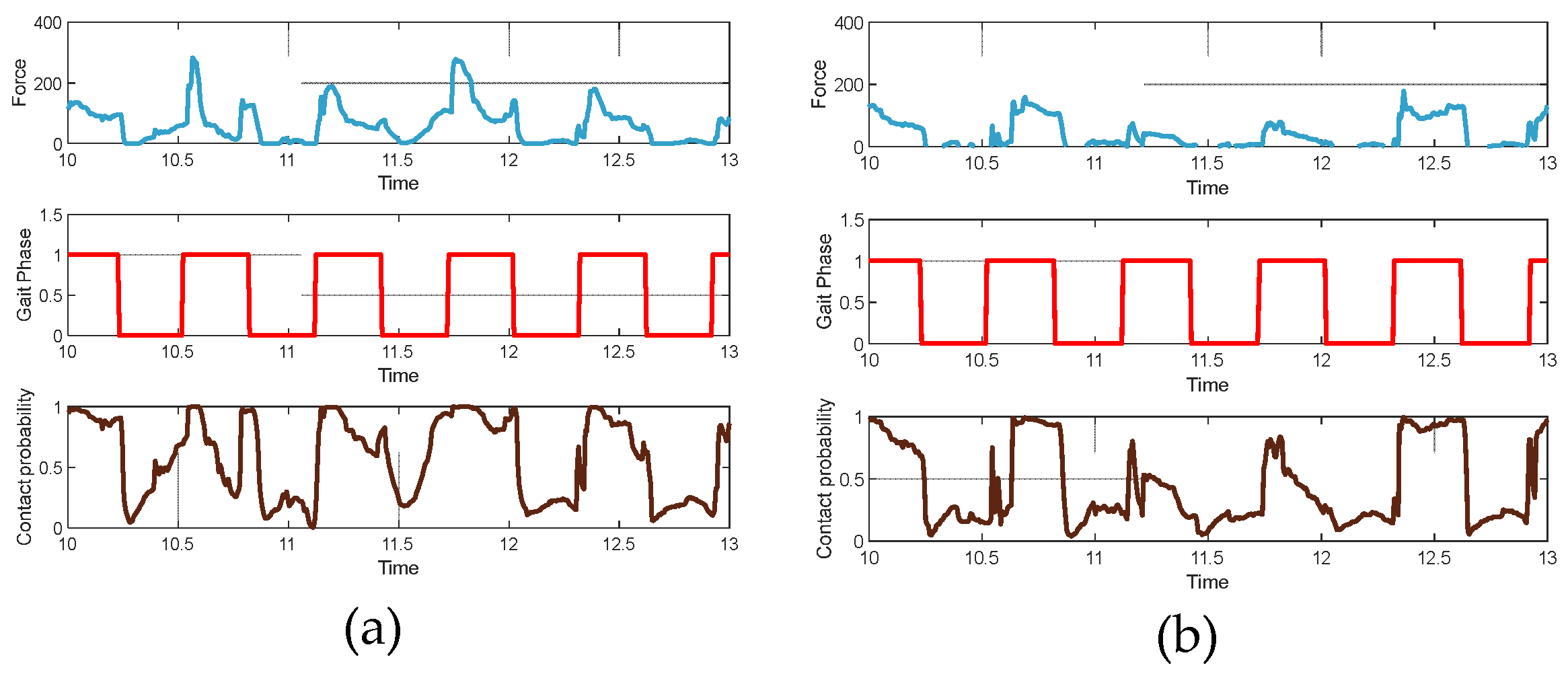

4.1. Contact Probability Calculation

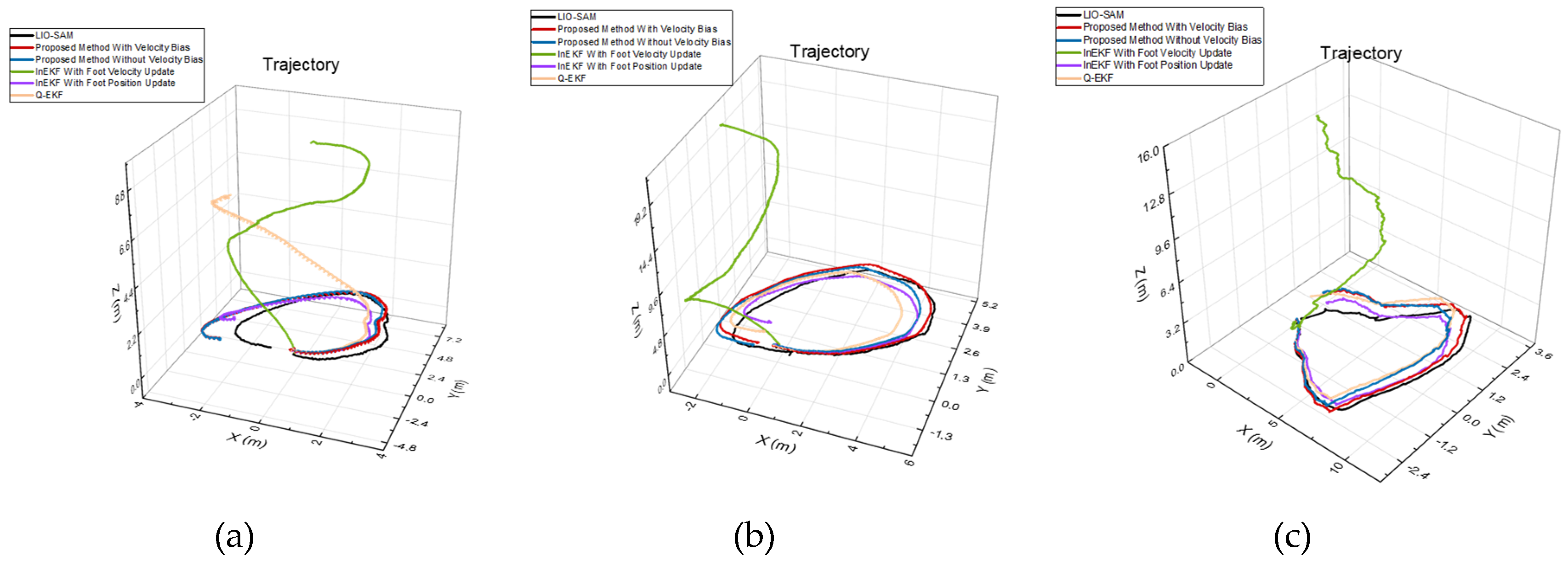

4.2. Algorithm Evaluation

5. Conclusions

References

- Cruz Ulloa, C.; Del Cerro, J.; Barrientos, A. Mixed-reality for quadruped-robotic guidance in SAR tasks. Journal of Computational Design and Engineering. 2023, 10, 1479–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.; Afsari, K.; Serdakowski, J. Real-time and remote construction progress monitoring with a quadruped robot using augmented reality. Buildings 2022, 12, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.; Yubin, L.; Ryoichi, I.; Takeshi, O.; Yoshihiro, S. Quadruped Robot Platform for Selective Pesticide Spraying. In Proceedings of the 2023 18th International Conference on Machine Vision and Applications (MVA), Hamamatsu, Japan, 23–25 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- David, W.; Marco, C.; Maurice, F. VILENS: Visual, Inertial, Lidar, and Leg Odometry for All-Terrain Legged Robots. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junwoon, L.; Ren, K.; Mitsuru, S.; Toshihiro, K. Switch-SLAM: Switching-Based LiDAR-Inertial-Visual SLAM for Degenerate Environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 7270–7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Komsuoglu, H.; Koditschek D., E. A leg configuration measurement system for full-body pose estimates in a hexapod robot. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2005, 21, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Komsuoglu, H.; Koditschek D, E. Sensor data fusion for body state estimation in a hexapod robot with dynamical gaits. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2006, 22, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloesch, M.; Hutter, M.; Hoepflinger M., A. State estimation for legged robots: Consistent fusion of leg kinematics and IMU. In Robotics: Science and Systems VIII. 2013. Nicholas, R., Paul N., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camurri, M.; Fallon, M.; Bazeille, S. Probabilistic contact estimation and impact detection for state estimation of quadruped robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 2, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, R.; Jadidi, M. G.; Grizzle J., W. Contact-aided invariant extended Kalman filtering for legged robot state estimation. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2020, 39, 402–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, J.; Theodorou, E. A. A Kalman filter for robust outlier detection. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 29 October–2 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, B.; Christian, G.; Péter, F.; Marco, H. Mark, A. State estimation for legged robots on unstable and slippery terrain. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jenelten, F.; Hwangbo, J.; Tresoldi, F. ; Dynamic locomotion on slippery ground. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 4170–4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisth, D.; Camurri, M.; Fallon, M. Robust legged robot state estimation using factor graph optimization. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 4507–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Yu, B.; Lee, E.M. STEP: State estimator for legged robots using a preintegrated foot velocity factor. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 4456–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.; Mueller, M.W.; Sreenath, K. Legged robot state estimation in slippery environments using invariant extended kalman filter with velocity update. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation(ICRA), Xi'an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, G.; Semini, C. Proprioceptive sensor fusion for quadruped robot state estimation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 October 2020-24 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rotella, N.; Schaal, S.; Righetti, L. Unsupervised contact learning for humanoid estimation and control. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 21–25 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, R.; Camurri, M.; Dellaert, F. Learning inertial odometry for dynamic legged robot state estimation. In Proceedings of the 5th Annual Conference on Robot Learning, London, UK, 8–11 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, R. State estimation of hydraulic quadruped robots using invariant-EKF and kinematics with neural networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 2231–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, K.; Song, J. Convergence and consistency analysis for a 3-D invariant-EKF SLAM. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 2, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiao, R.; Li, J. A High-Precision LiDAR-Inertial Odometry via Invariant Extended Kalman Filtering and Efficient Surfel Mapping. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Teng, S.; Chakhachiro, T. Fully proprioceptive slip-velocity-aware state estimation for mobile robots via invariant kalman filtering and disturbance observer. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Detroit, MI, USA, 1–5 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grupp, M. evo: Python package for the evaluation of odometry and SLAM. Available online: https://github.com/MichaelGrupp/evo (accessed on 17 September 2024).

| Measurement Type | Noise std. dev | State Variable | Initial Covariance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gyroscope | 0.1 rad/s | Robot Orientation | 0.03 rad |

| Accelerometer | 0.1 m/s2 | Robot Velocity | 0.01 m/s |

| Foot Encoder Pos | 0.01 m | Robot Position | 0.01 m |

| Foot Encoder Vel | 0.1 m/s | Robot Slip Velocity | 0.01 m/s |

| Disturbance Process | 5 m/s |

| Terrain | Method | ATE RMSE | RPE RMSE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position(m) | Rotation(rad) | Position(m) | Rotation(rad) | ||

| Rugged Slopes | QEKF | 1.3459 | 1.0541 | 0.0654 | 0.0385 |

| InEKF with Vel update | 1.5898 | 2.8388 | 0.0743 | 0.0395 | |

| InEKF with Pos update | 0.4704 | 0.2185 | 0.0633 | 0.0358 | |

| PM without Vel Bias | 0.4666 | 0.1628 | 0.0601 | 0.0358 | |

| PM with Vel Bias | 0.4572 | 0.1626 | 0.0601 | 0.0345 | |

| Shallow Grass | QEKF | 0.7893 | 0.4661 | 0.0697 | 0.0367 |

| InEKF with Vel update | 2.3747 | 3.0528 | 0.0665 | 0.0368 | |

| InEKF with Pos update | 0.6525 | 0.3039 | 0.0626 | 0.0655 | |

| PM without Vel Bias | 0.3501 | 0.1238 | 0.0393 | 0.0630 | |

| PM with Vel Bias | 0.3431 | 0.1261 | 0.0391 | 0.0641 | |

| Deep Grass | QEKF | 0.5993 | 0.2867 | 0.0628 | 0.0558 |

| InEKF with Vel update | 3.3818 | 1.3146 | 0.0797 | 0.0452 | |

| InEKF with Pos update | 0.7552 | 0.3526. | 0.0653 | 0.0522 | |

| PM without Vel Bias | 0.6920 | 0.3228 | 0.0646 | 0.0506 | |

| PM with Vel Bias | 0.5289 | 0.2035 | 0.0601 | 0.0498 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).