Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Stochastic Orders and Their Properties

2.2. One-X Order and A Related Conjecture

2.3. Inter-disciplinary Concept Comparison

| Financial Mathematics Concepts | Actuarial Science Concepts |

| One-X Order: | Less Dangerous: |

| Increasing Convex Order: | Stop-loss Order: |

| Convex Order: | Transitive closure of : . |

3. A Counterexample to Conjecture Section 2.2

3.1. (Increasing) Convex Order Between Exponential Family Distributions

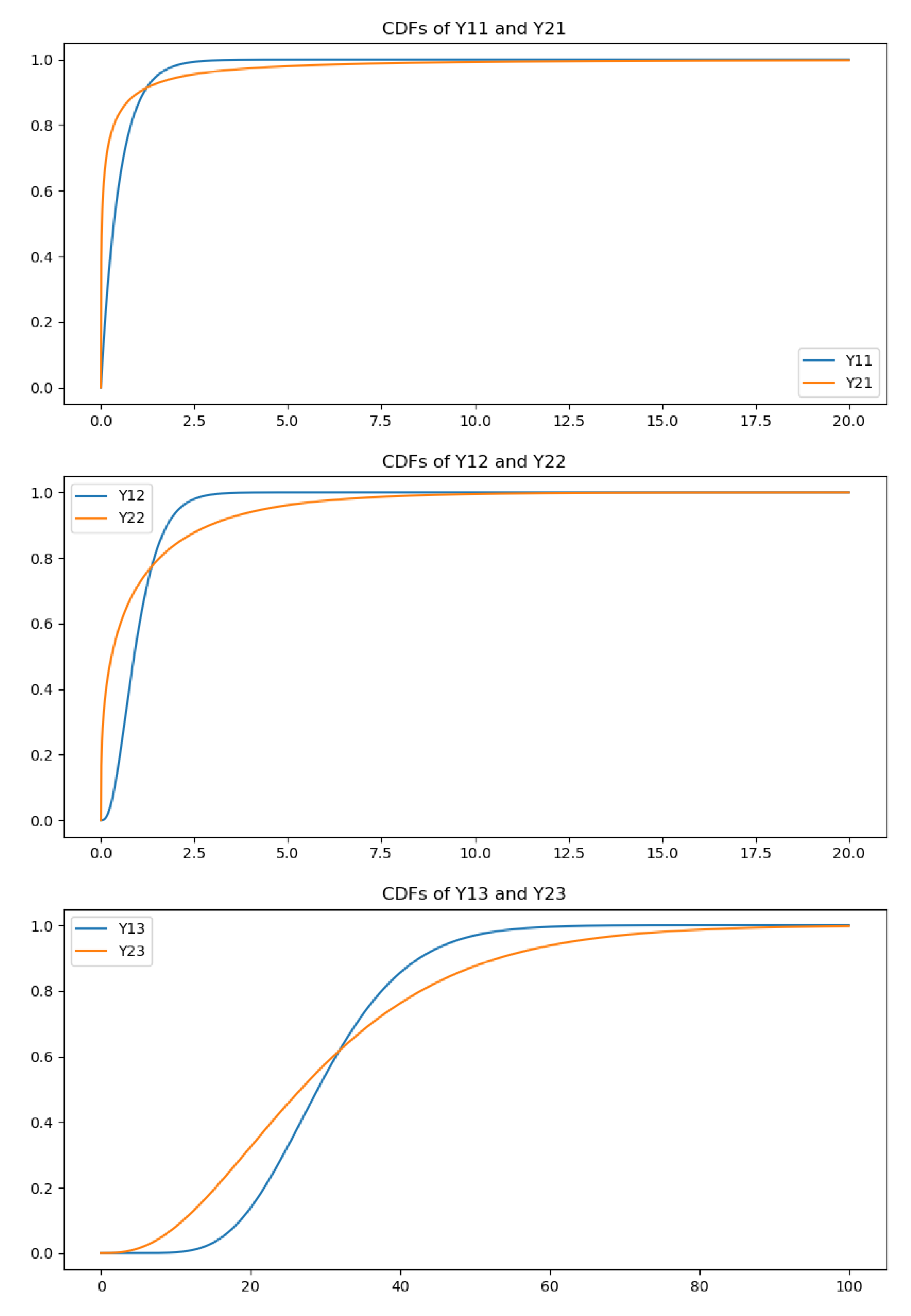

3.2. The Counterexample

- , , ;

- , , .

4. One-X Interpolation Between Convex Ordered Pairs

4.1. A General One-X Interpolation Result

- The random variables assume positive value, since they reflect the distributions of tradable assets on different expirations, and thus they are positive in nature.

-

The random variables share the same mean, since in the most intriguing cases the underlying assets behave as martingales after certain preparation.When the underlying is of equity class, the existence of dividends brings challenges into the construction of IV and local volatility surface. One way to bypass this is the pure stock process [8]: assume that the equity price is , the pure stock is defined as where and is the stock’s forward price. As shown in [8], is a positive martingale with , and all the pricing theories can be transformed from to . In particular, the construction of IV surface or the implied density will be associated with the process.When the underlying is of fixed-income class, the typical options are caps/floors and swaptions. For caps/floors, the underlying is the forward rate which is a martingale under T-forward measure; for swaptions, the underlying is the swap rate which is a martingale under swap measure (for more technical details, see [1]).

- The CDF’s of the random variables are analytic functions, as they mostly arise from approximations of market data by known families of analytic distributions.

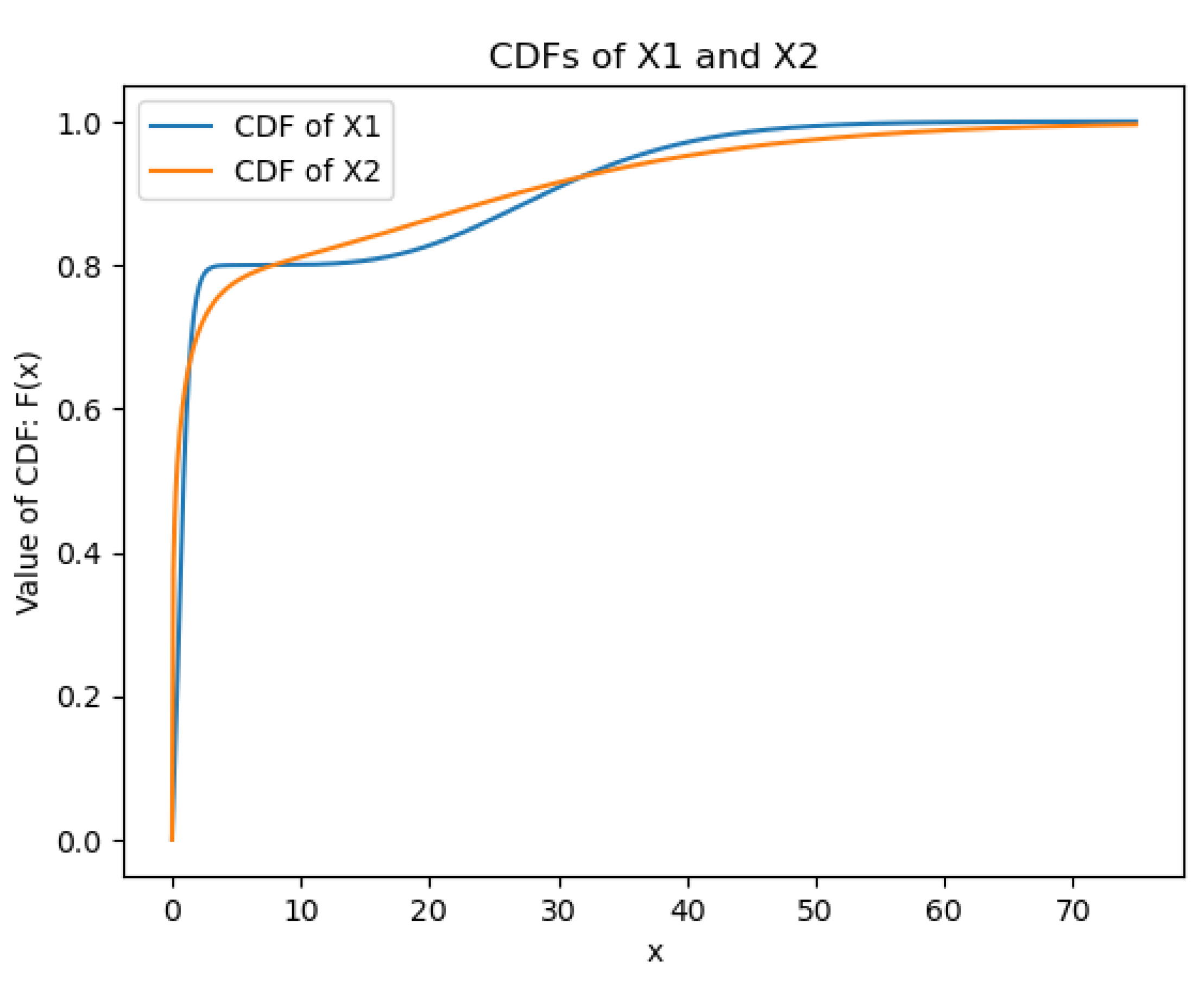

4.2. Log Gaussian Mixtures

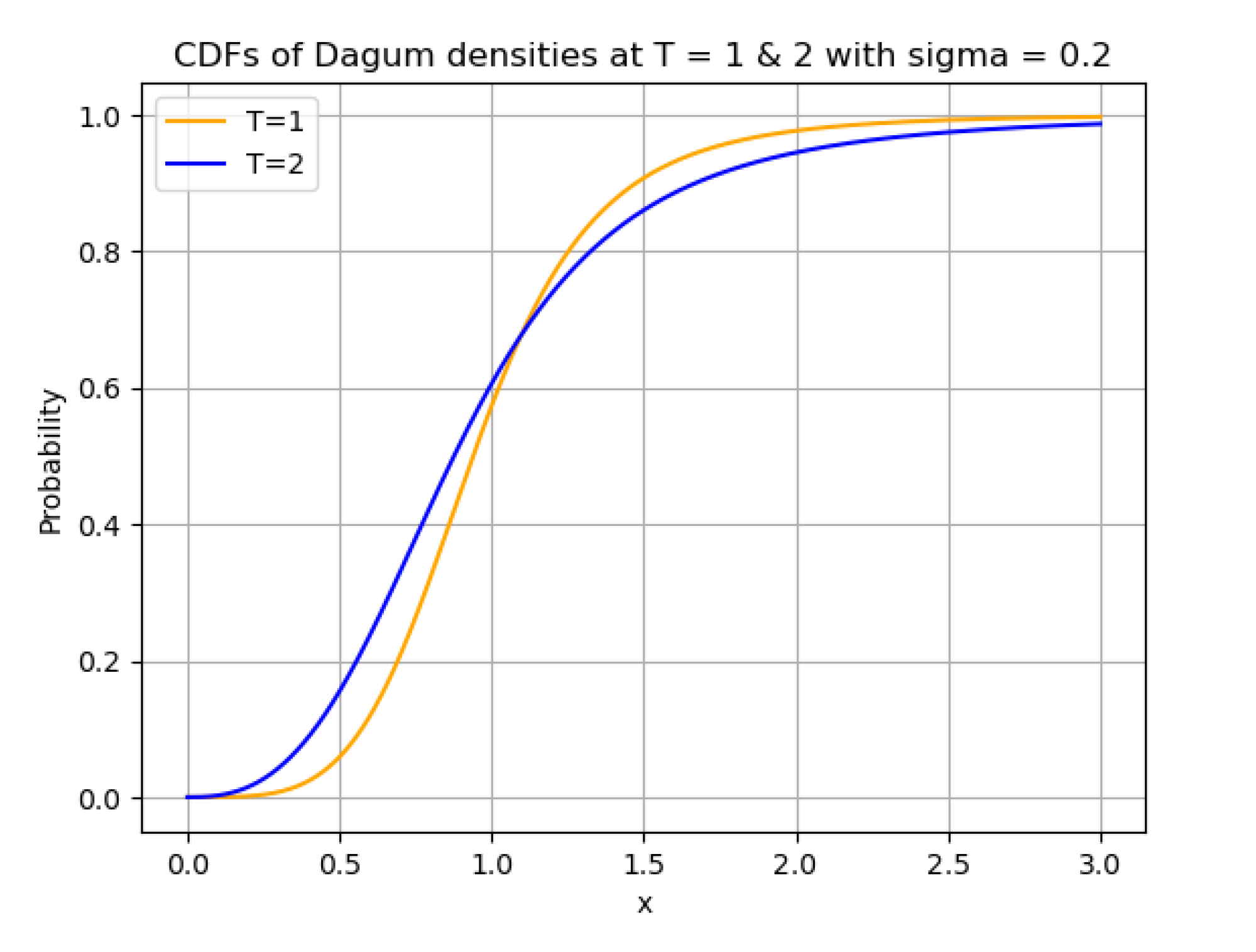

5. , , Unimodality of Density Ratio and Convex Ordering

5.1. A Brief Review of the Concepts

-

is is increasing in y, for any fixed , andis is decreasing in y, for any fixed ;

-

if is differentiable in x, thenis is increasing in y, andis is decreasing in y;

-

if is, moreover, twice differentiable, thenis , andis .

- is increasing for , and

- is decreasing for ,

- satisfies the uniform unimodality of density ratio; and

- is mixed then on .

5.2. Relation with the One-X Property

- If , there is no intersection between the graphs of and of . Without loss of generality, assuming on , we would arrive at the following contradictionsince .

- If , then the graphs of and intersects at a single point , with signs or . In either cases, since (), it always holds , and thuswhich is impossible.

6. IV Surface Construction and Future Work

6.1. Criteria for Log Gaussian Mixtures to the Obey Convex Order

- the first sign change of the difference occurs from − to +, there is an even number of crossing points , and the following inequalities hold:

- the first sign change of the difference occurs from + to −, there is an odd number of crossing points , and the following inequalities hold:

6.2. Convex Ordering and IV Surface Construction

-

IV InterpolationIt is not an uncommon case that for three listed maturities , there are high quality quotes on and while at there are few reasonable bid/ask quote pairs for periods of time. In this case, we can fit implied density functions at and , and we can assume that there is no calendar arbitrage between them. To get an implied density function at , one can do martingale interpolation that guarantees no-arbitrage among the three implied density functions.Ever since the introduction of martingale optimal transport (MOT) [16], martingale interpolation has become an attractive research area. In [16], a straightforward generalization of the McCann’s interpolations from optimal transport (OT) is introduced, and can be viewed as martingale version of McCann’s interpolations (Definition 2.9, [16]). Later, [4], from a probabilistic point of view, proposes a Benamou–Brenier-type formulation of the martingale transport problem for given distributions , in convex order. The unique solution to their problem is a Markov martingale with several remarkable properties: in a specific way, it replicates the movement of a Brownian particle as closely as possible, subject to the conditions and . Similar to McCann’s displacement interpolation, offers a time-consistent interpolation between , as two margins. Recently, [20] suggests a new framework. The authors introduce randomized arcade processes (RAP) which can match any finite sequence of target random variables (in convex order) at fixed times across the entire probability space. This makes RAP a powerful tool for strong stochastic interpolation between target random variables. Then they introduce filtered arcade martingales (FAM) which are martingales constructed using the filtrations generated by RAP. They provide an almost-sure solution to the martingale interpolation problem and reveal an underlying stochastic filtering structure. The paper shows that FAM can be informed by Bayesian updating when the underlying RAP is conditionally-Markov, which adds an additional layer of sophistication to the interpolation process.These martingale interpolation methods are all good candidates for our implied density interpolation purpose. Particularly, the last one which is inspired by the information-based approach [7] helps provide more reasonablely interpolated results. We believe that such frameworks or methods are suitable for implied density function, and thus IV interpolation, especially for the pure stock process in equity or swaption in fixed income. In other words, as long as the underlying asset can be modelled as a martingale process, then the above discussed martingale interpolation methods can be applied for implied density/IV interpolation.The purpose of this interpolated implied density function at is two-folds. On the one hand, it can provide an educated guess when there are few quotes; on the other hand, when there are a few good bid/ask quotes but not enough for a good fitting, one can use the interpolated implied density function as a reference when applying one’s own IV fitting method. For example, one can fit one’s own implied density model and minimize the Kullback–Leibler divergence between the fitted result and the interpolated one to avoid unexpected behaviours when searching for the local minimum of the IV fitting loss function. One can also use the interpolated implied density function to generate enough artificial mid quotes and fit a set of parameters for one’s own model. This set of parameters can be used as a good initial guess to better fit one’s own model with respect to the available (but not enough) market data.Though several financial applications have been proposed, it seems that the current paper is one of the first work considering to apply martingale interpolation to implied density interpolation for maturities with poor liquidity and discussing the proper situation to apply this technique.

-

Synthetic IV generationAlong with the rapid growth of generative AI such as generative adversarial nets (GAN) [15], variational autoencoder (VAE) [21], diffusion model [17] etc, synthetic data generation and its application in financial industry has become an active research area; see, for instance, the pioneer work [2]. The properly generated synthetic financial data gives an extra edge in back-testing and risk management on trading/hedging strategies. Since one of the most important components in equity option market is the IV surface, we consider synthetic IV curve generation on a given listed maturity.Instead of pure non-parametric methods which focus on the direct generation of the IV curve, we propose to apply a more parametric method. For instance, when dealing with pure stock price, for a given listed maturity T, we can assume that the implied density function is of the formwhere n is a fixed large enough integer to generate the required IV smile, represents the probability such that , and is the PDF of a log Gaussian distribution whose mean is and whose standard deviation is . Then instead of learning the distribution of the IV curve itself, one can try to learn the distribution of the set of parameters , using the various generative AI algorithms mentioned above. This approach has the following benefits:

- −

- the problem is reduced to a finite dimensional learning problem which is more feasible;

- −

- with the help of (7), the generated IV curve has no butterfly arbitrage naturally; moreover, due to its parametric form, the resulted IV curve is smoother and stabler;

- −

- due to its parametric form, it is easier to estimate useful quantities such as skewness and kurtosis of the underlying distribution, and compare them with the shape of the IV curve.

Also, notice the fact that mixtures of Gaussian distributions are dense in the set of probability distributions with respect to the weak topology, with a properly chosen n, our assumption will lose minimal information. Moreover, we can apply the above arguments to both bid and ask quotes instead of the sole mid quotes.

References

- L. B. G. Andersen and V. V. Piterbarg. Interest Rate Modeling. Atlantic Financial Press, 2010.

- Hans Buehler, Blanka Horvath, Terry Lyons, Imanol Perez Arribas, and Ben Wood. A data-driven market simulator for small data environments. Preprint arXiv:2006.14498, 2020, arXiv:2006.14498.

- F. Belzunce, C. M. Riquelme and J. Mulero. An Introduction to Stochastic Orders. Elsevier Science, 2015.

- Julio Backhoff-Veraguas, Mathias Beiglböck, Martin Huesmann, Sigrid Källblad. Martingale Benamou–Brenier: a probabilistic perspective. Preprint arXiv:1708.04869, 2017, arXiv:1708.04869.

- M. Beiglböck and N. Juilet. On a problem of optimal transport under marginal martingale constructions. Ann. Probab.441: 42-106, 2016.

- Fischer Black and Myron Scholes. The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities. Journal of Political Economy, 81(3): 637-654, 1973.

- D. Brody, L. P. Hughston and A. Macrina. Financial Informatics: An Information-based Approach to Asset Pricing. G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. World Scientific, 2021.

- Hans Buehler. Volatility and dividends-volatility modelling with cash dividends and simple credit risk. Available at SSRN, 2010.

- Emanuel Derman and Iraj Kani. Riding on a smile. Risk, 7(2): 32–39,1994.

- Bruno, Dupire; et al. Pricing with a smile. Risk, 7(1) 18–20,1994.

- Xiaojing Fan, Chunliang Tao, and Jianyu Zhao. Advanced stock price prediction with xlstm-based models: Improving long-term forecasting. Preprints, August 2024.

- Jim Gatheral. A parsimonious arbitrage-free implied volatility parameterization with application to the valuation of volatility derivatives. Presentation at Global Derivatives & Risk Management, Madrid, page 0, 2004.

- Paul Glasserman and Dab Pirjol. W-shaped implied volatility curves and the Gaussian mixture model. Quantitative Finance, 23(4): 557-577, 2023.

- Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville. Deep learning, MIT press, 2016.

- Ian Goodfellow, Jean Pouget-Abadie, Mehdi Mirza, Bing Xu, David Warde-Farley, Sherjil Ozair, Aaron Courville and Yoshua Bengio. Generative adversarial nets. Advances in neural information processing systems, 27, 2014.

- P. Henry-Labordère. Model-free Hedging: A Martingale Optimal Transport Viewpoint. Chapman & Hall/CRC financial mathematics series. CRC Press, 2017.

- Jonathan Ho, Ajay Jain and Pieter Abbeel. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33: 6840-6851, 2020.

- Werner Hürlimann. Extremal moment methods and stochastic orders. Boletin de la Associacion Matematica Venezolana, 15(2): 153-301, 2008.

- R. Kaas, M. J. Goovaerts, and A. E. van Heerwaarden, A.E. Ordering of Actuarial Risks. Caire education series. CAIRE, 1994.

- Georges Kassis and Andera Macrina. Arcade Processes for Informed Martingale Interpolation and Transport. Preprint arXiv:2301.05936, 2013, arXiv:2301.05936.

- Diederik, P. Kingma and Max Welling. Auto-encoding variational bayes. Preprint arXiv:1312.6114, 2013, arXiv:1312.6114.

- Alfred Müller. Orderings of risks: A comparative study via stop-loss transforms. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 17(3): 215-222, 1996.

- J. B. Ohlin. On a class of measures of dispersion with application to optimal reinsurance. ASTIN Bullentin, 5: 249-266, 1969.

- Glasserman, Paul and Pirjol, Dan. Total positivity and relative convexity of option prices. Peter Carr Gedenkschrift: Research Advances in Mathematical Finance 393-443, 2024.

- Glasserman, Paul and Pirjol, Dan. When Are Option Prices TP2? . Available at SSRN 488 7499, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- M. Shaked and J. G. Shanthikumar. Stochastic Orders. Springer Series in Statistics. Springer New York, 2007.

- V. Strassen. The existence of probability measures with given marginals. Ann. Math. Statist. 36: 423-439 1965.

- Milena Vuletic and Rama Cont. Volgan: a generative model for arbitrage-free implied volatility surfaces. Available at SSRN, 2023.

- Valer Zetocha. The Longitude: managing implied volatility of illiquid assets. Available at SSRN, 2022.

- Valer Zetocha. Volatility Transformers: an optimal transport-inspired approach to arbitrage-free shaping of implied volatility surfaces. Available at SSRN, 2023.

- Siqiao Zhao. PolyModel: Portfolio Construction and Financial Network Analysis. PhD thesis, Stony Brook University, 2023.

| 1 | The authors are thankful for the communications with Prof. Dan Pirjol who pointed out these interesting proposition and example. |

| 2 | Most of this part is based on or inspired by the last part of the second author’s PhD thesis [31], and all the contents are for pure academic research purpose only. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).