Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

18 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

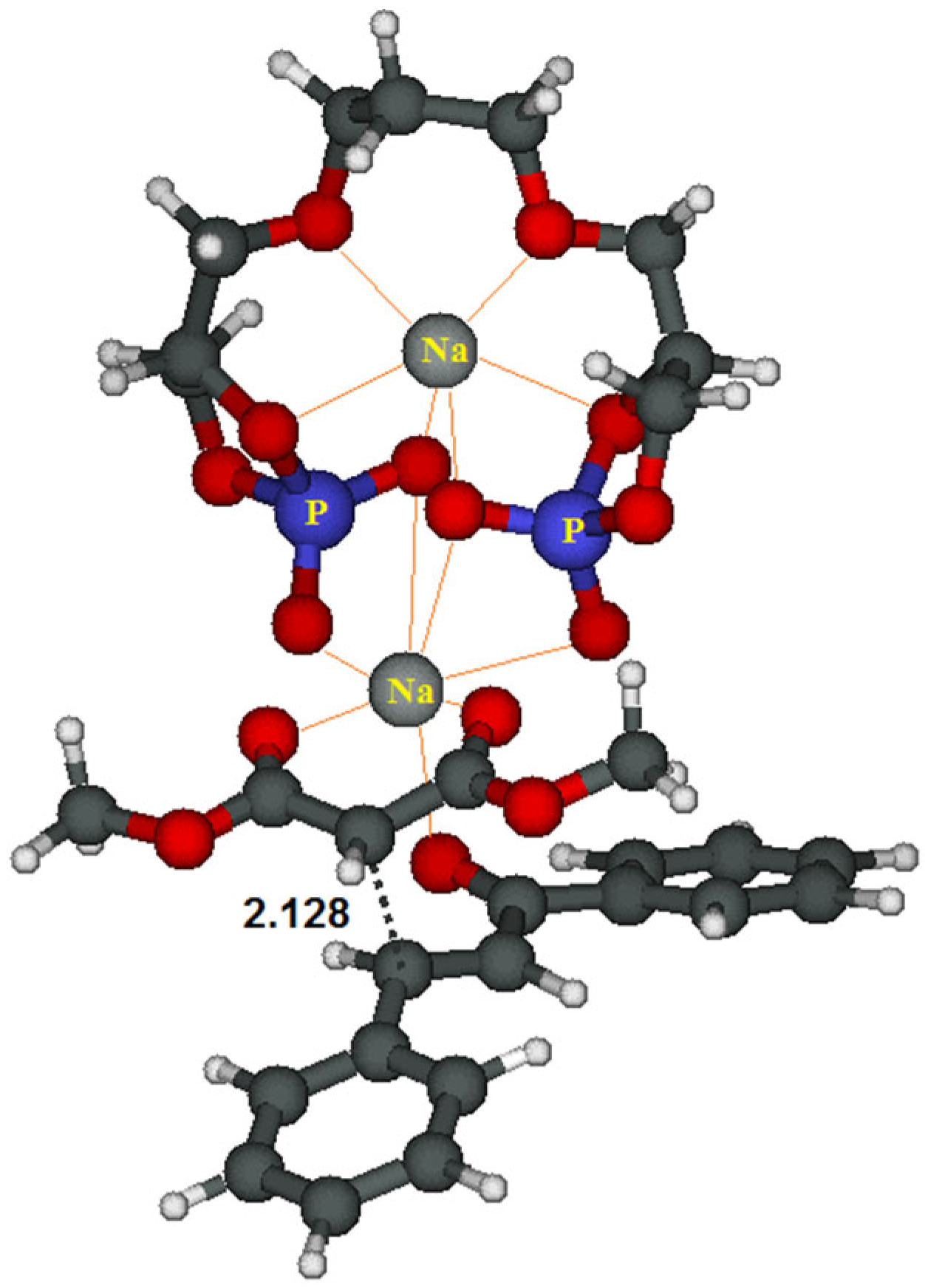

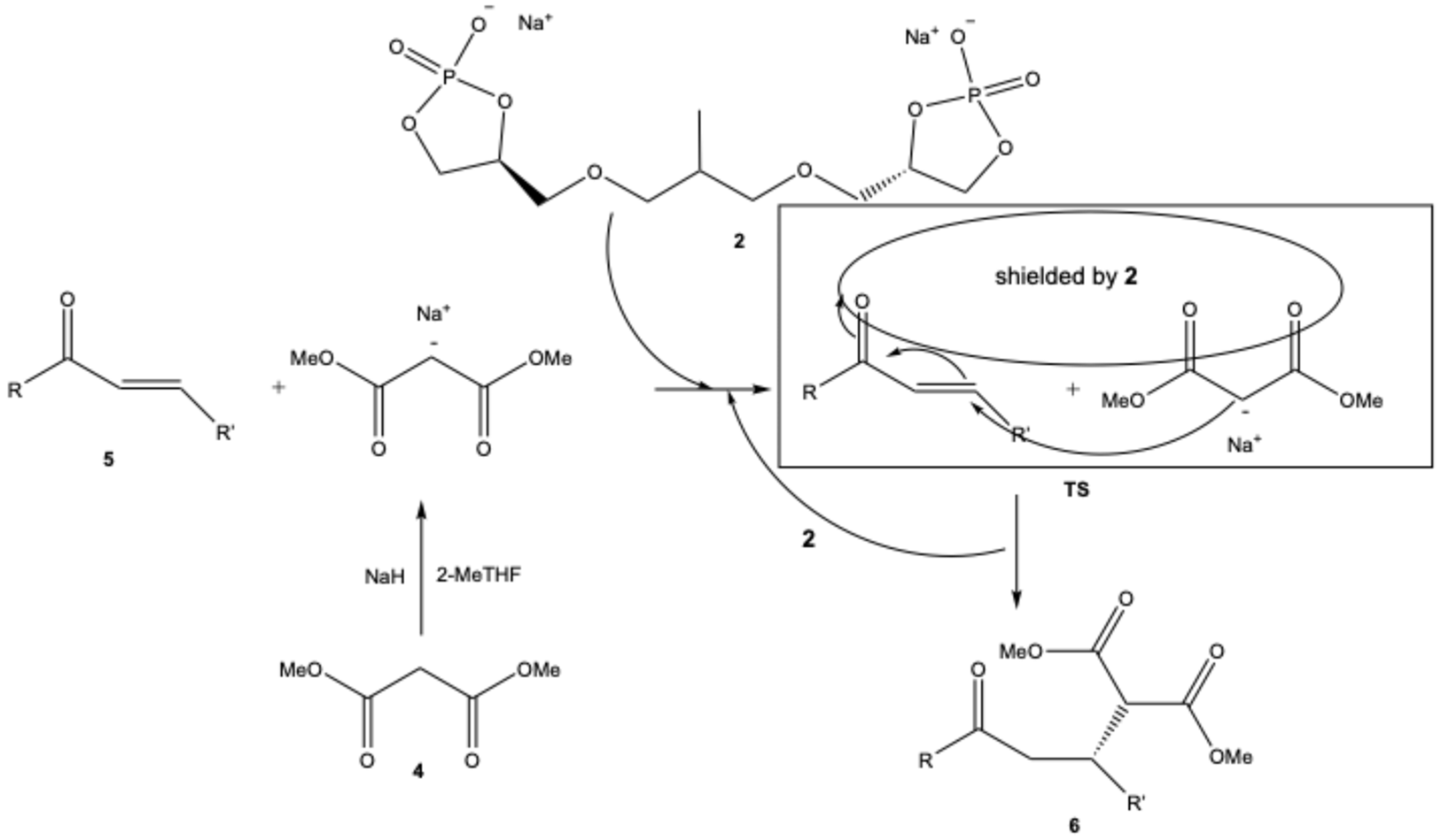

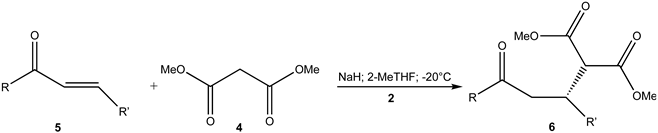

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

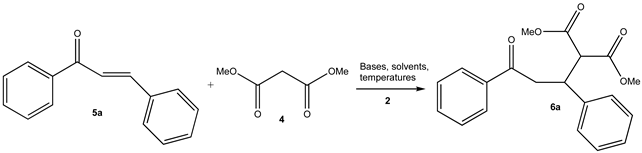

3.2. As a Catalyst in Michael Reactions. Typical Procedure: Synthesis of (R)(-)-Dimethyl 2-(3-oxo-1,3-diphenylpropyl)Malonate (6a)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Book: Akiyama, T.; Ojima, I. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis. 4th Edition, John Wiley and Sons USA, 2022.

- Book: R. A. Aitken, S. N. Kilényi, Asymmetric Synthesis, Springer Netherlands, 2012.

- Garg, A.; Rendina, D.; Bendale, H.; Akiyama, T.; Ojima, I. Recent advances in catalytic asymmetric synthesis. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Cocco, E.; Antenucci, A.; Carlone, A.; Manini, P.; Pesciaioli, F.; Dughera, S. Stereoselective Reactions Promoted by Alkali Metal Salts of Phosphoric Acid Organocatalysts. ChemCatChem, 2024, e202400328. [CrossRef]

- Brodt, N.; Niemeyer, J. Chiral organophosphates as ligands in asymmetric metal catalysis Org. Chem. Front., 2023, 10, 3080–3109. [CrossRef]

- Antenucci, A.; Messina, M.; Bertolone, M.; Bella, M.; Carlone, A.; Salvio, R.; Dughera, S. Turning renewable feedstocks into a valuable and efficient chiral phosphate salt catalyst. Asian J. Org. Chem., 2021, 10, 3279–3284. [CrossRef]

- Antenucci, A.; Ghigo, G.; Cassetta, D.; Alcibiade, M.; Dughera, S. Design, synthesis and application of C2-symmetric cycloglycerodiphosphate. Adv. Synth. Catal., 2023, 365, 1170–1178. [CrossRef]

- Tsogoeva, S. B. Recent Advances in Asymmetric Organocatalytic 1,4-Conjugate Additions. Eur. J. Org. Chem., 2007, 1701–1716. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Liu, X.; Feng, X. Recent advances in metal-catalyzed asymmetric 1,4-conjugate addition (ACA) of nonorganometallic nucleophiles. Chem. Rev.,2018, 118, 7586–7656. [CrossRef]

- Rachwalski, M.; Buchcic-Szychowska, A.; Lesniak, S. Recent advances in selected asymmetric reactions promoted by chiral catalysts: cyclopropanations, Friedel–Crafts, Mannich, Michael and other zinc-mediated processes. An update. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1762–1786. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Matsubara, R. Recent topics on catalytic asymmetric 1,4-addition. Tetrahedron Lett., 2017, 58, 1793–1805. DOI:.

- Yang, J.; Wu, S.; Chen, F.-X. Chiral sodium phosphate catalyzed enantioselective 1,4-addition of TMSCN to aromatic enones. Synlett, 2010, 18, 2725–2728. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Kaplan, M. J.; Antilla, J. C. Chiral calcium VAPOL phosphate mediated asymmetric chlorination and Michael reactions of 3-Substituted oxindoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 3339–3341. [CrossRef]

- Pairault, N.; Zhu, H.; Jansen, D.; Huber, A.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Grimme, S.; Niemeyer, J. Heterobifunctional rotaxanes for asymmetric Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2020, 59, 5102 – 5107. [CrossRef]

- Kohler, E. P.; Chadwell, H. M. Benzalacetophenone. Org. Synth. 1922, 2, 1. [CrossRef]

- Capreti, N. M. R.; Jurberg, I.D. Michael addition of soft carbon nucleophiles to alkylidene isoxazol-5-ones: a divergent entry to β-branched carbonyl compounds. Org.Lett., 2015, 17, 2490−2493. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, M.; Blay, G.; Cardona, L.; Pedro, J. R. Asymmetric conjugate addition of malonate esters to α,β-unsaturated N-sulfonyl imines: an expeditious route to chiral δ-aminoesters and piperidones. Chem. Eur. J., 2013, 19, 14861–14866. [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Fang, G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, G. Enantioselective Michael addition of malonates to chalcone derivatives catalyzed by dipeptide-derived multifunctional phosphonium salts. J. Org. Chem., 2016, 81, 9973–9982. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Jia, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, R. Water-compatible iminium activation: highly enantioselective organocatalytic Michael addition of malonates to α,β-unsaturated enones. J. Org. Chem., 2010, 75, 7428–7430. [CrossRef]

- Kohler, E. P.; Hill, G. A.; Bigelow, L. A. Studies in the cyclopropane series. Third paper. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1917, 39, 2405–2418. [CrossRef]

- De Simone, N. A.; Meninno, S.; Talotta, C.; Gaeta, C.; Neri, P.; Lattanzi, A. Solvent-free enantioselective Michael reactions catalyzed by a calixarene-based primary amine thiourea. J. Org. Chem., 2018, 83, 10318–10325. [CrossRef]

- Ueda, A.; Umeno, T.; Doi, M.; Agakawa, K.; Kudo, K.; Tanaka, M. Helical-peptide-catalyzed enantioselective Michael addition reactions and their mechanistic insights. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6343–6356. [CrossRef]

- Dudzinski, K.; Pakulska, A. M.; Kwiatkowski, P. An efficient organocatalytic method for highly enantioselective Michael addition of malonates to enones catalyzed by readily accessible primary amine-thiourea. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 4222–4225. [CrossRef]

- Jiricek, J.; Blechert, S. Enantioselective synthesis of (--)-gilbertine via a cationic cascade cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 3534–3538. [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G. Density Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules, in: Horizons Quantum Chem., Springer Netherlands, 1980: pp. 5–15. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008,41,157–167. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.; Horn, H.; Ahlrichs, R. Fully optimized contracted Gaussian basis sets for atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys.1992, 97, 2571–2577. [CrossRef]

- Foresman, J.; Frisch, A. Exploring chemistry with electronic structure methods, 1996, Gaussian Inc, Pittsburgh, PA, 1996. https://gaussian.com/expchem3/(accessed June 4, 2021).

- Ribeiro, R.F.; Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Use of solution-phase vibrational frequencies in continuum models for the free energy of solvation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011, 115, 14556–14562. [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions J. Phys. Chem. B, 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [CrossRef]

- Truhlar, D.G.; Garrett, B.C.; Klippenstein, S.J. Current status of transition-state theory J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 12771–. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Li, X.; Caricato, M.; Marenich, A.V.; Bloino, J.; Janesko, B.G.; Gomperts, R.; Mennucci, B.; Hratch, Gaussian 16, Revision A.03, 2016.

- Schaftenaar, G.; Noordik, J.H. Molden: a pre- and post-processing program for molecular and electronic structures. J. Comput. Aided. Mol. Des. 2000, 14, 123–134. [CrossRef]

| |||||||

| Entry | Catalyst 2 (mmol%) | Base | Solvent | T (°C) | Time (h) | Yield (%)1,2 | Ee (%)3 |

| 1 | - | - | MeOH | rt | 24 | traces | - |

| 2 | 5 | - | MeOH | rt | 24 | traces | - |

| 3 | 10 | - | MeOH | rt | 24 | traces | - |

| 4 | 10 | MeOH | 60 | 24 | traces | - | |

| 5 | 5 | - | 2-MeTHF | rt | 24 | traces | - |

| 6 | 10 | - | 2-MeTHF | rt | 24 | traces | - |

| 7 | 10 | - | 2-MeTHF | 60 | 24 | traces | - |

| 8 | 5 | - | Toluene | rt | 24 | - | - |

| 9 | 5 | - | DCM | rt | 24 | - | - |

| 10 | 5 | - | DMSO | rt | 24 | - | - |

| 11 | 5 | - | MeCN | rt | 24 | - | - |

| 12 | 5 | CH3ONa | MeOH | rt | 8 | 52 | 34.3 |

| 13 | 10 | CH3ONa | MeOH | rt | 6 | 51 | 32.8 |

| 14 | 5 | CH3ONa | Toluene | rt | 24 | - | - |

| 15 | 5 | NaH | 2-MeTHF | rt | 3 | 92 | 37.5 |

| 16 | 5 | NaH | 2-MeTHF | 0 | 5 | 90 | 57.2 |

| 17 | 5 | NaH | 2-MeTHF | -20 | 8 | 90 | 91.5 |

| 18 | 5 | NaH | 2-MeTHF | -45 | 8 | 21 | 90.8 |

| 19 | - | NaH | 2-MeTHF | rt | 3 | 91 | - |

| 20 | - | NaH | 2-MeTHF | -20 | 8 | 90 | - |

| |||||

| Entry | R in 5,6 | R’ in 5,6 | Time (h) | Yield (%) of 6 1,2,3 | Ee (%)4 |

| 1 | C6H5 | C6H5 | 8 | 6a; 90 | 91.5 |

| 2 | C6H5 | 4-NO2C6H4 | 10 | 6b; 87 | 88.9 |

| 3 | C6H5 | 4-ClC6H4 | 6 | 6c; 89 | 92.9 |

| 4 | C6H5 | 4-MeC6H4 | 4 | 6d; 92 | 90.0 |

| 5 | C6H5 | 4-CNC6H4 | 10 | 6e; 92 | 90.3 |

| 6 | C6H5 | 2-NO2C6H4 | 12 | 6f; 77 | 90.5 |

| 7 | C6H5 | 3-NO2C6H4 | 8 | 6g; 90 | 89.9 |

| 8 | C6H5 | Thiophen-2-yl | 6 | 6h; 82 | 89.6 |

| 9 | C6H5 | Furan-2-yl | 6 | 6i; 77 | 89.3 |

| 10 | Me | C6H5 | 6 | 6j; 82 | 92.5 |

| 11 | Me | 2-MeC6H4 | 8 | 6k; 90 | 94.4 |

| 12 | Me | 3-MeOC6H4 | 6 | 6l; 85 | 88.8 |

| 13 | C6H5 | Me | 4 | 6m; 87 | 89.5 |

| 14 | 4-CF3C6H4 | C6H5 | 6 | 6n; 92 | 89.7 |

| 15 | 2-MeOC6H4 | C6H5 | 6 | 6o; 79 | 87.0 |

| 16 | 3-MeC6H4 | 4-ClC6H4 | 8 | 6p; 82 | 89.9 |

| 17 | 3-MeC6H4 | 4-NO2C6H4 | 10 | 6q; 91 | 87.0 |

| 18 | 4-CF3C6H4 | 4-MeC6H4 | 6 | 6r; 90 | 92.4 |

| 19 | 4-ClC6H4 | C6H5 | 6 | 6s; 85 | 89.0 |

| 20 | 4-NO2C6H4 | C6H5 | 6 | 6t; 85 | 90.5 |

| 21 | Et | Me | 4 | 6u; 85 | 81.8 |

| 22 |  |

6 | 6v; 83 | 87.5 | |

| 23 |  |

6 | 6w; 91 | 70.2 | |

| 24 | CH3 | H | 8 | 6x; - | - |

| 25 | OCH3 | H | 8 | 6y; - | - |

| 26 | H | H | 8 | 6z; - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).