Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

18 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

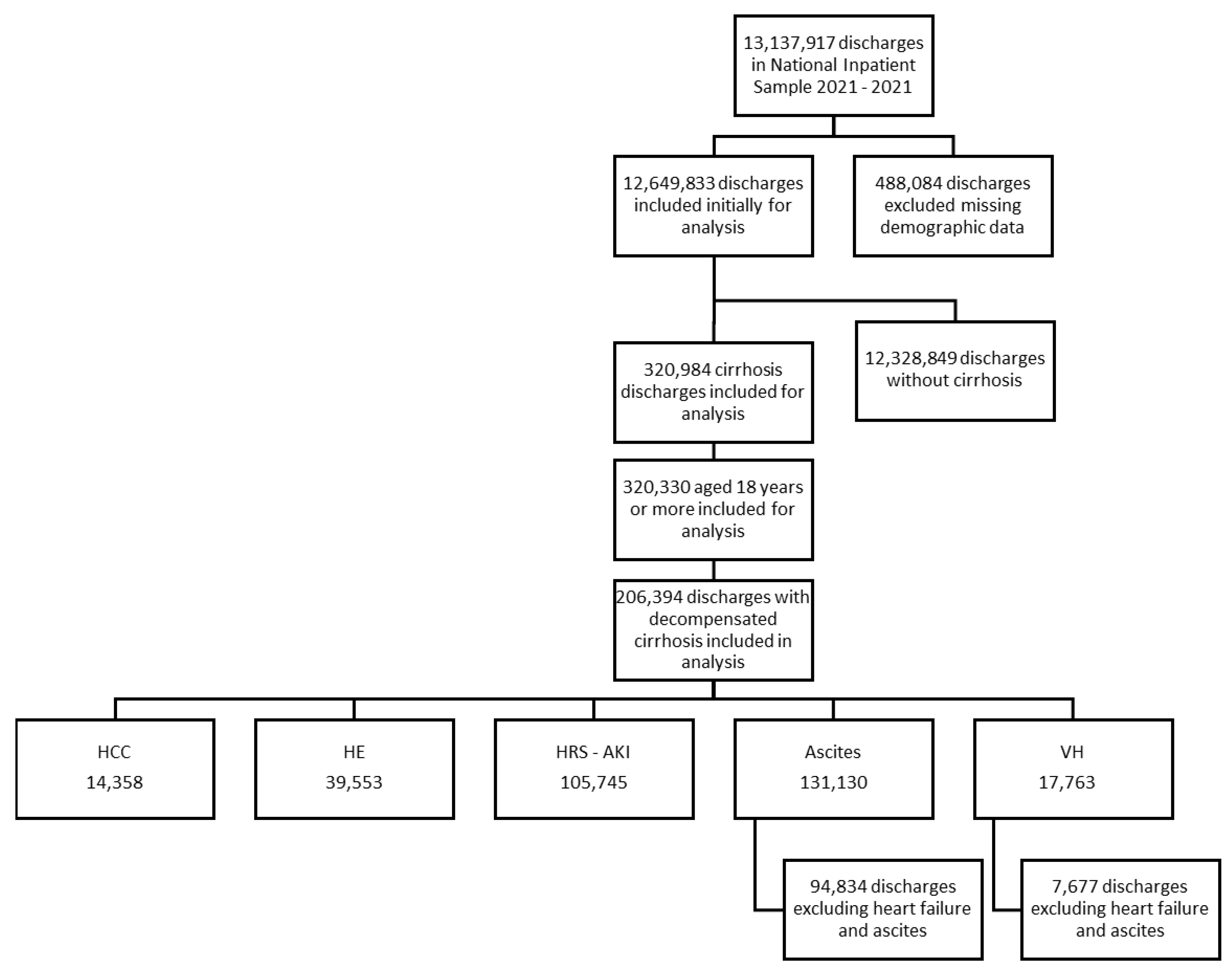

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

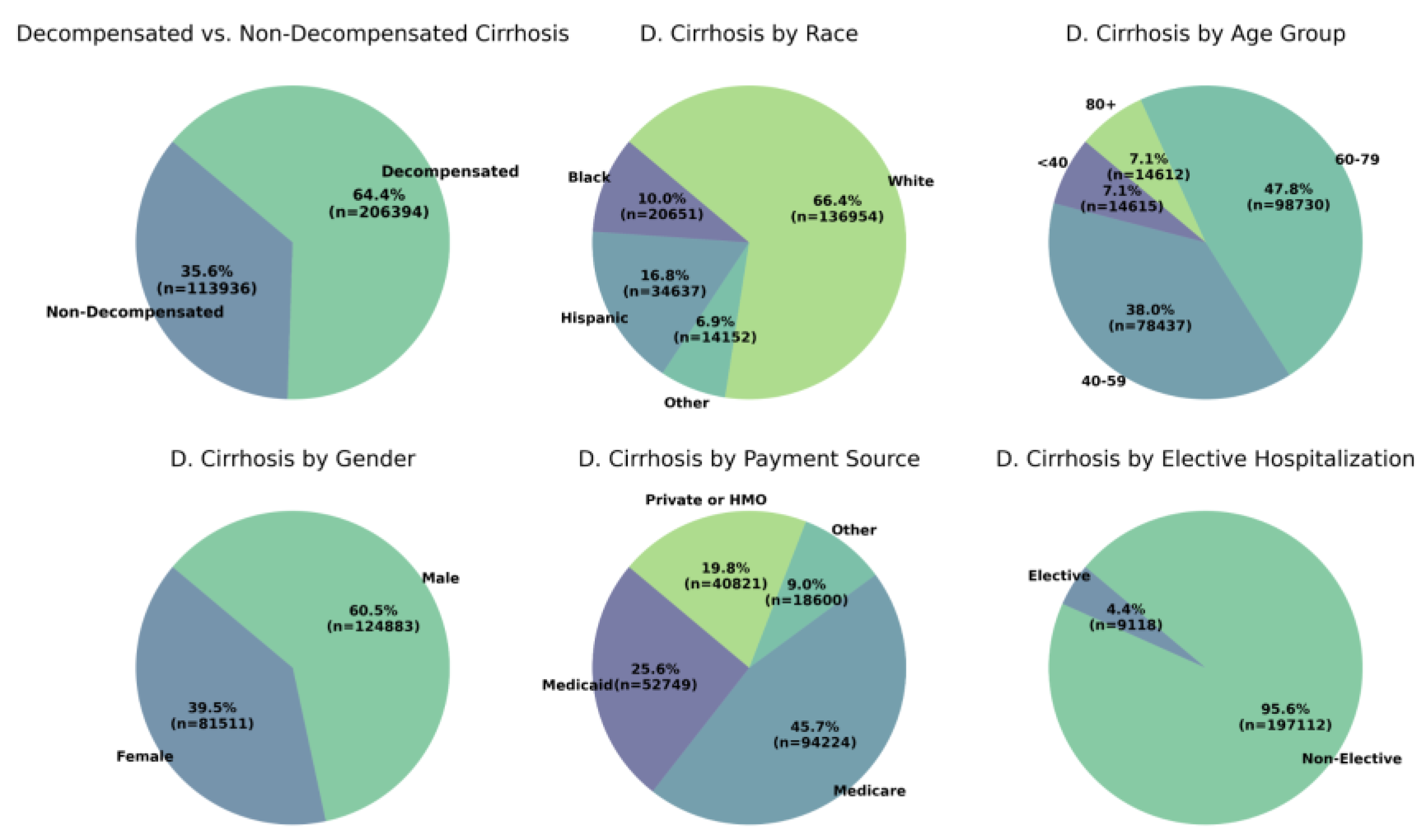

3.1. Patient Characteristics

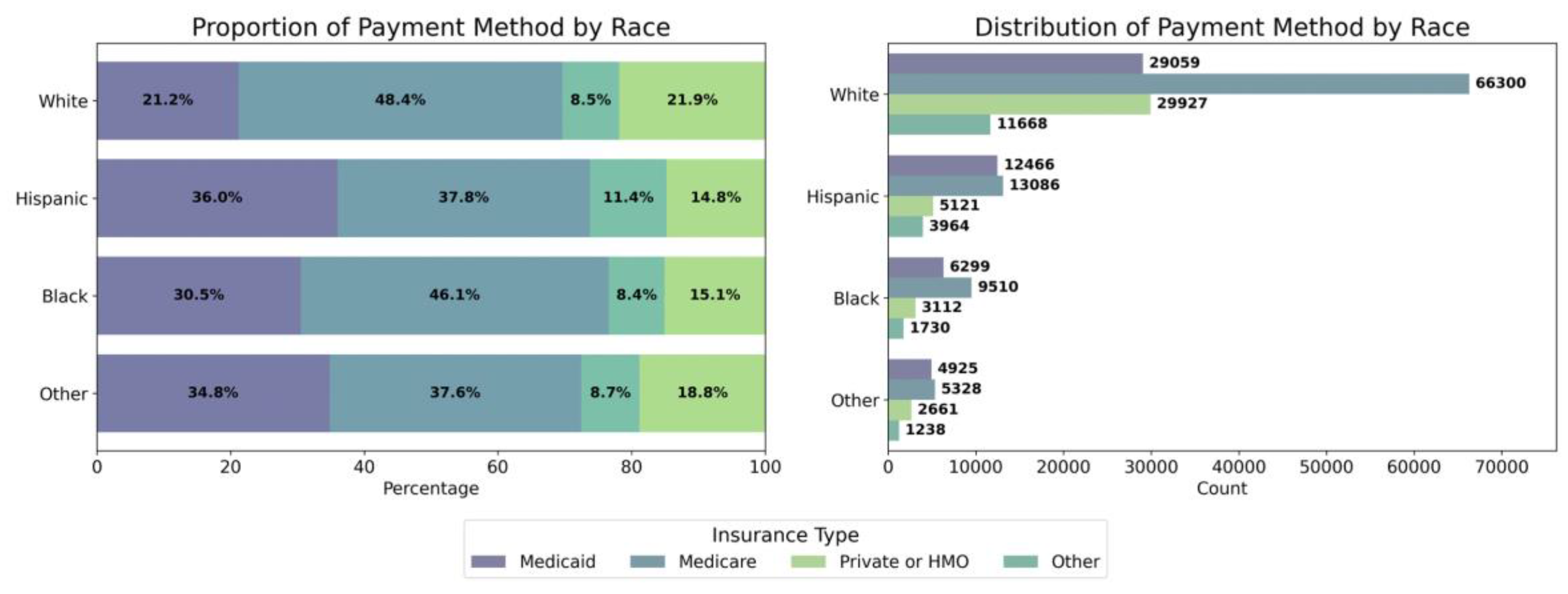

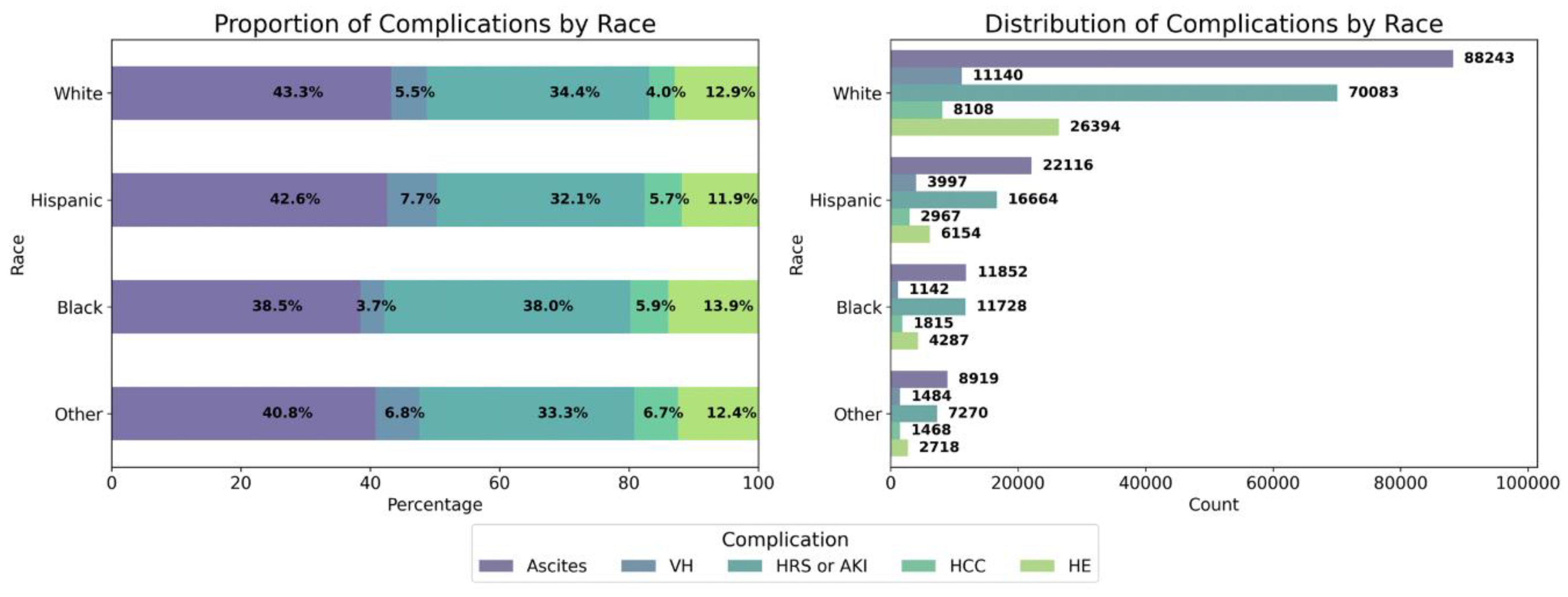

3.2. Racial and Ethnic

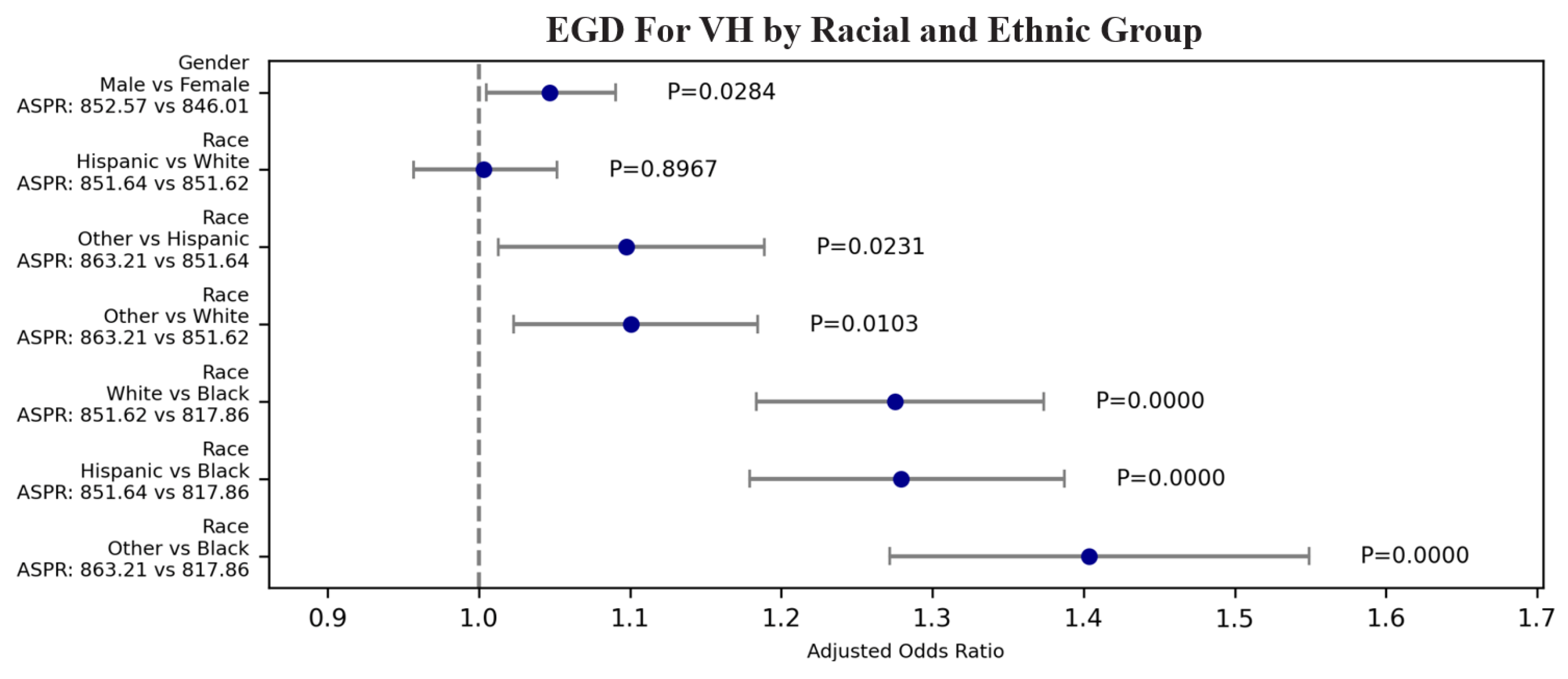

3.2.1. Racial and Ethnic: EGD for VH

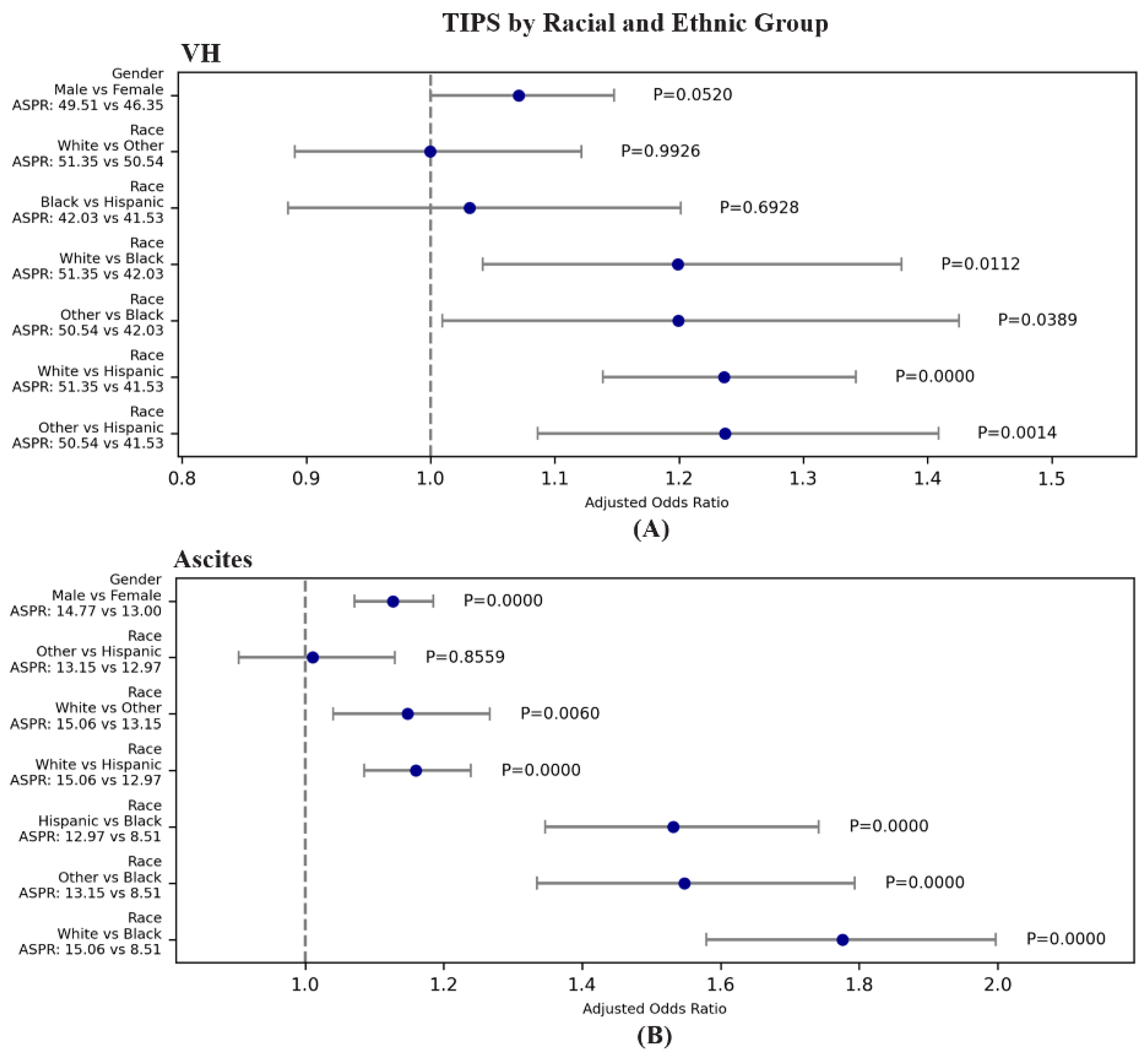

3.2.3. Racial and Ethnic: TIPS for VH and Ascites

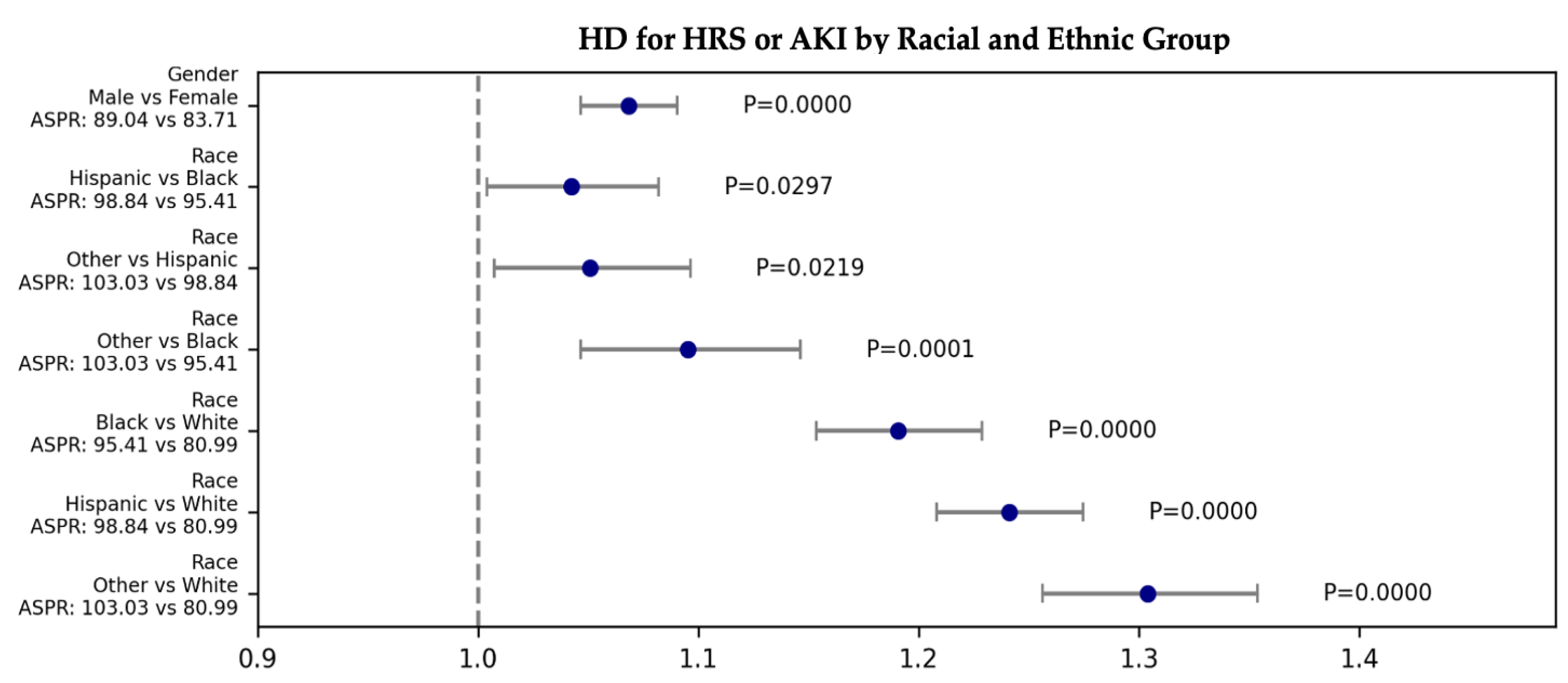

3.2.4. Racial and Ethnic: Hemodialysis/Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT) for HRS or AKI

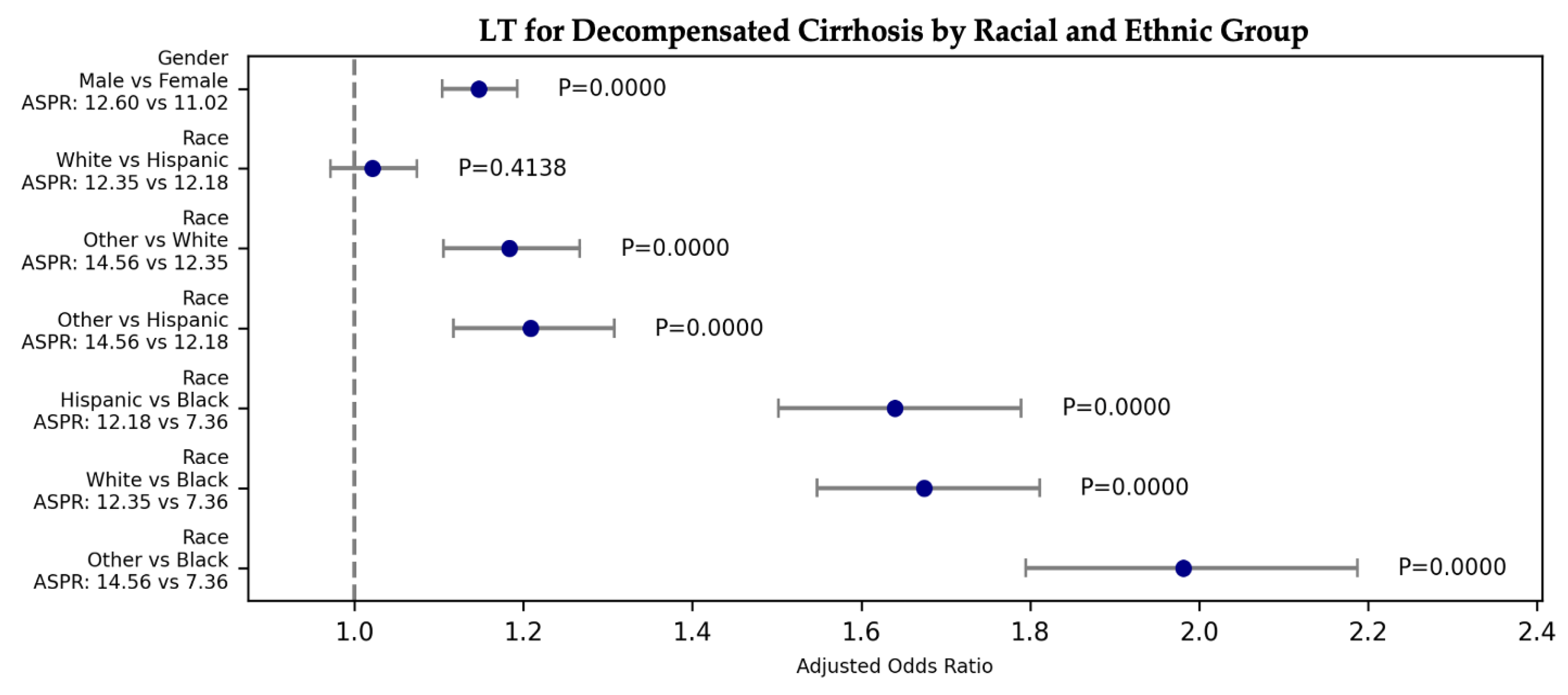

3.2.5. Racial and Ethnic: LT

3.3. Socieconomic

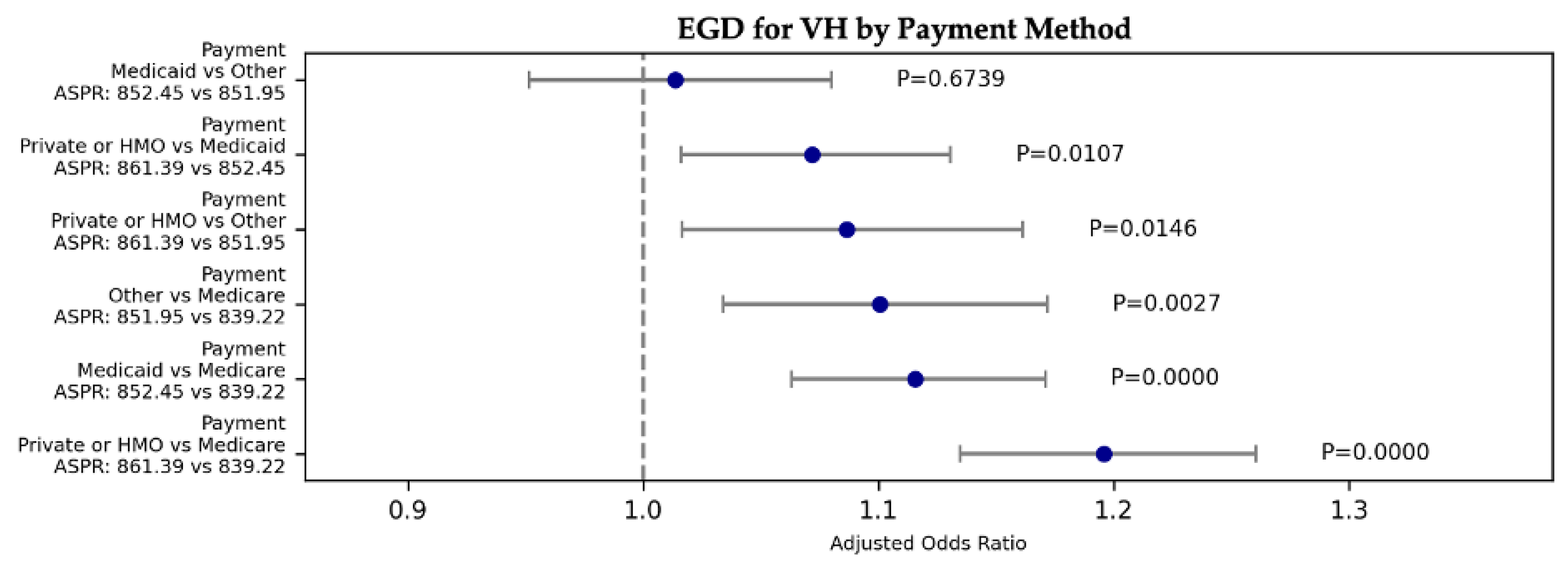

3.3.1. Socieconomic: EGD for VH

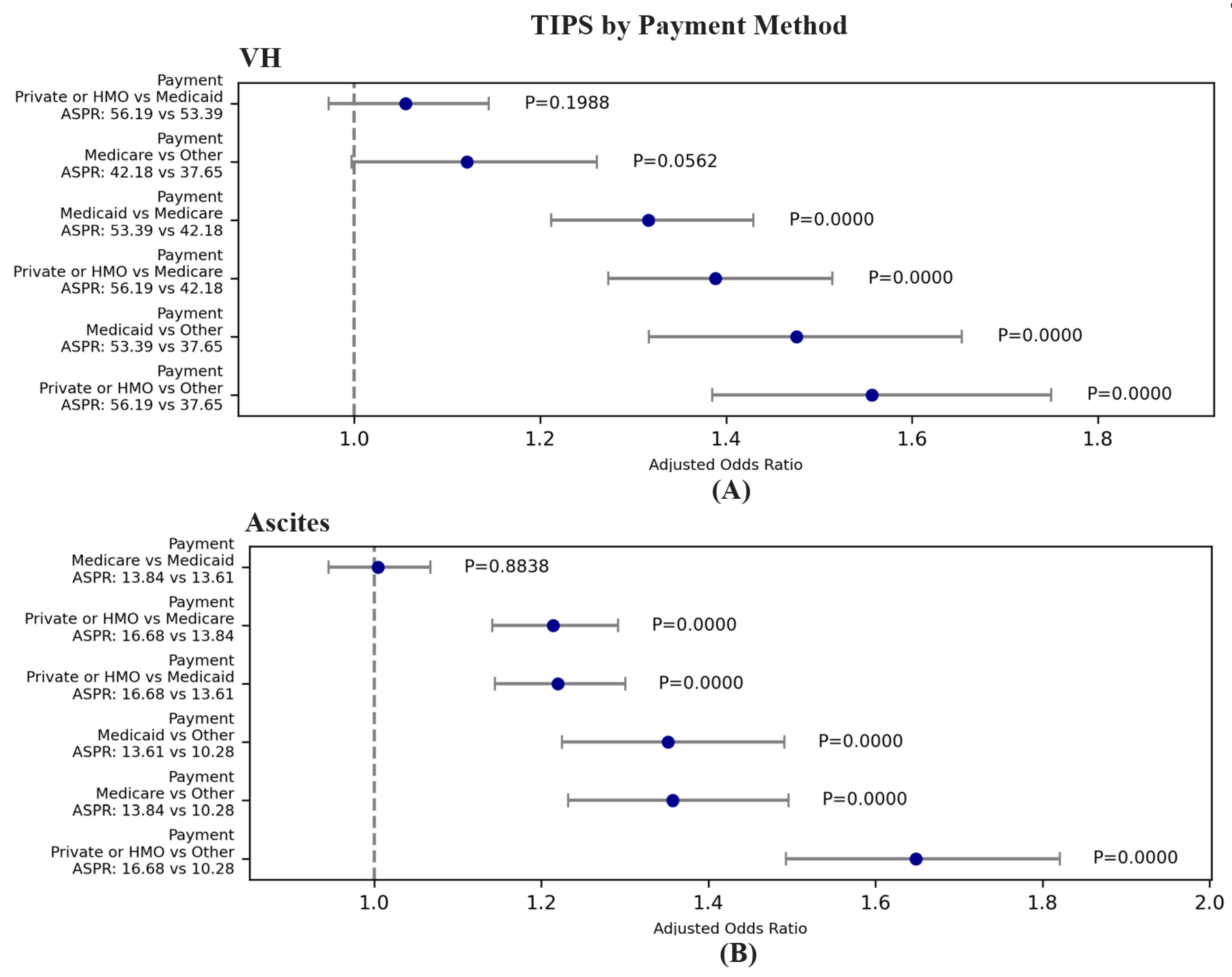

3.3.3. Socieconomic: TIPS for VH and Ascites

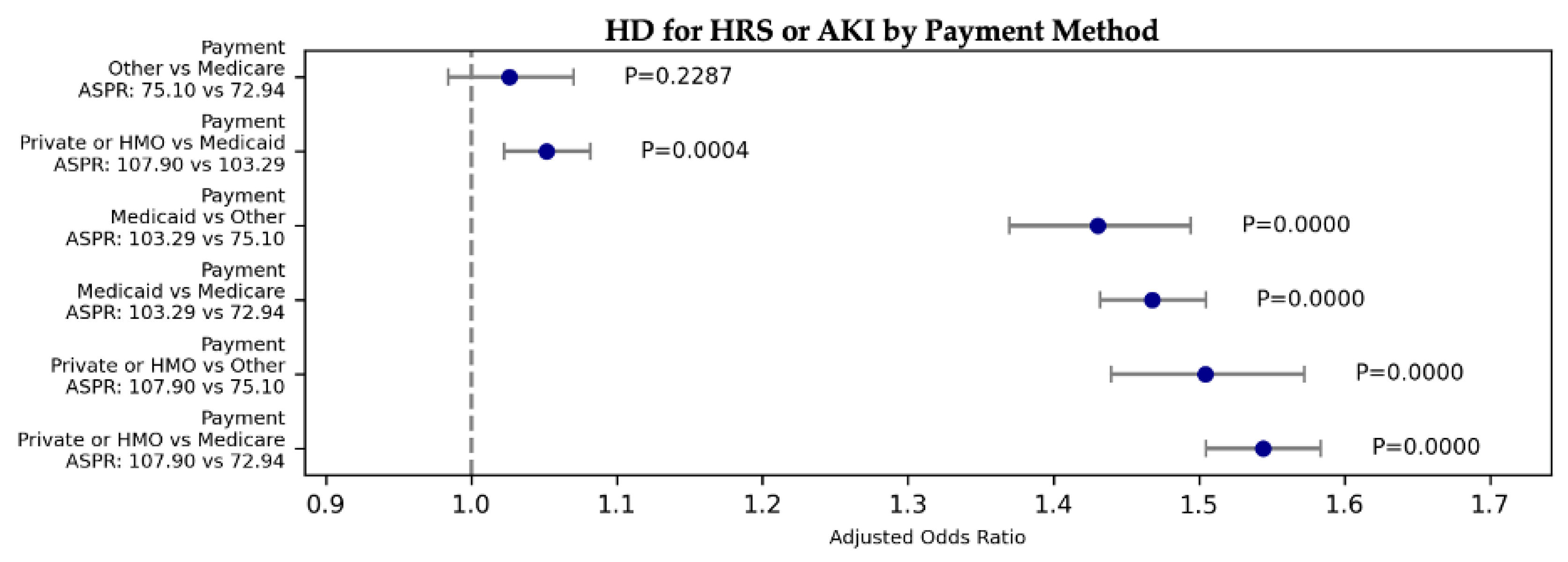

3.3.4. Socieconomic: Hemodialysis/CRRT for HRS or AKI

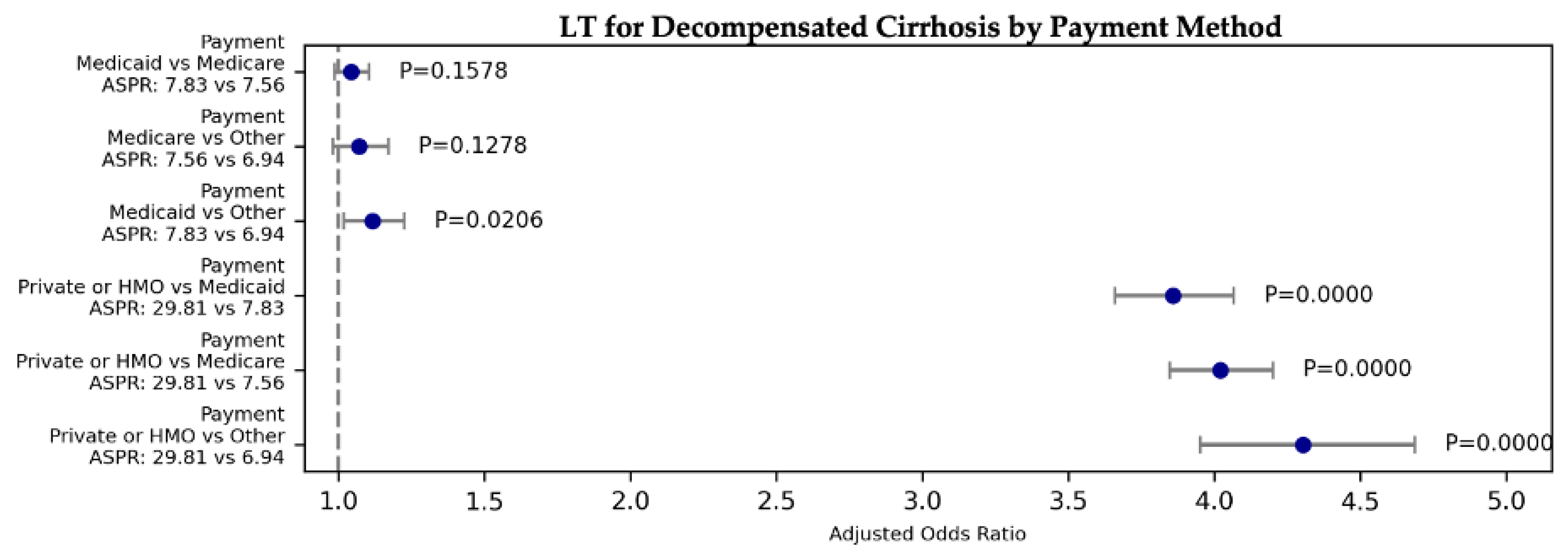

3.3.5. Socieconomic: LT for overall decompensated cirrhosis

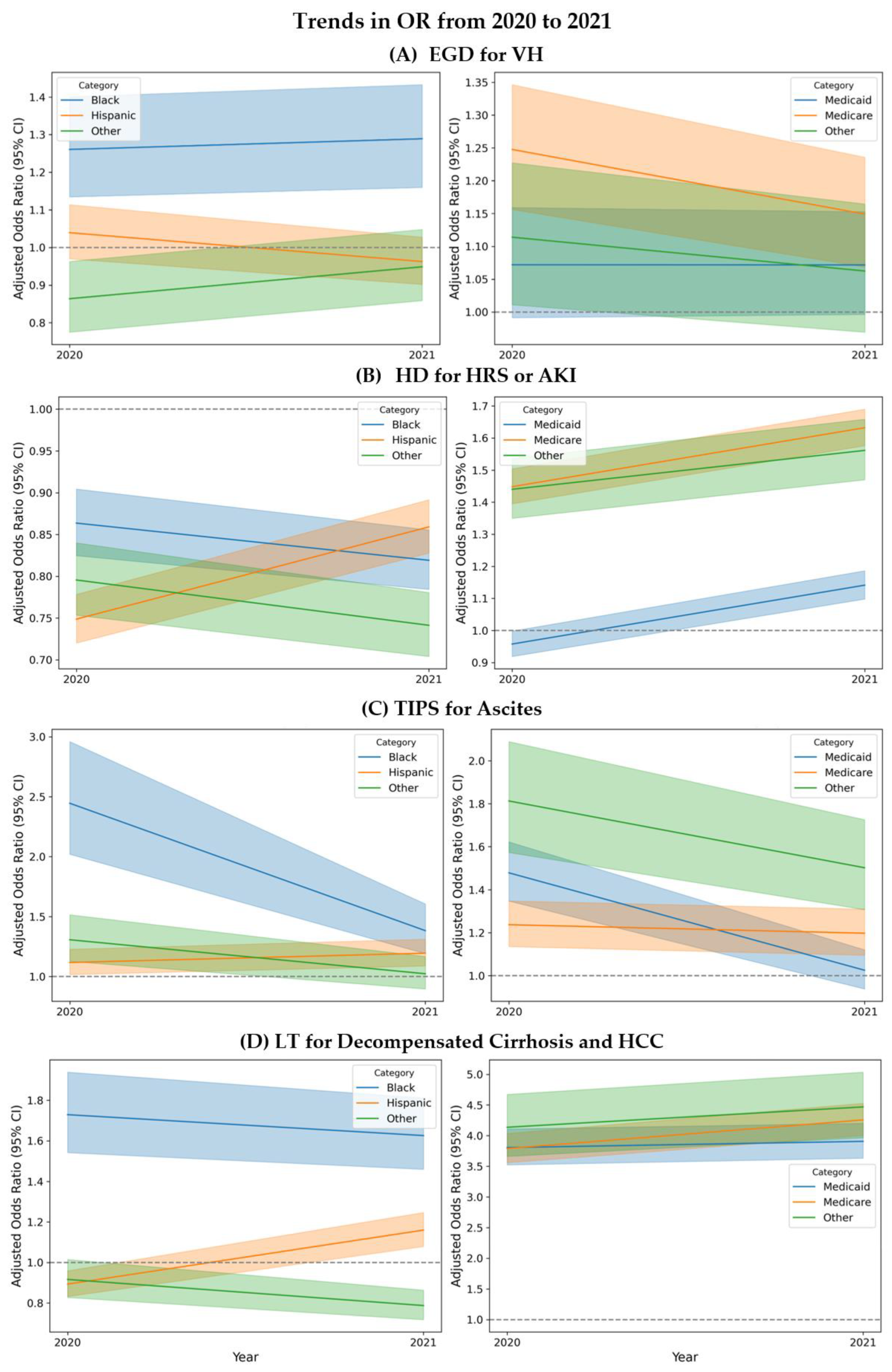

3.4. Trends in Disparities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Subcategory | ICD-10 Codes |

| Cirrhosis Codes | Hepatic Fibrosis and Sclerosis | K740, K7400, K7401, K7402, K741, K742 |

| Biliary Cirrhosis | K743, K744, K745 | |

| Unspecified Cirrhosis of Liver | K7460 | |

| Other Cirrhosis of Liver | K7469 | |

| Alcoholic Cirrhosis of Liver | K7030, K7031 | |

| Alcoholic Fibrosis and Sclerosis | K702 | |

| Complication Codes | Ascites | R188, K7031, K7011, K7151 |

| VH (Variceal Hemorrhage) | I8501, I8511 | |

| HE (Hepatic Encephalopathy) | G9340, G9341, G9349, R40*, K7041, K7111, K7201, K7211, K7291, B190, B1911, B1921 | |

| SCC (Somnolence, stupor, and coma) | R40 | |

| HRS or AKI (Hepatorenal Syndrome or Acute) | K767, N170, N171, N172, N178, N179 | |

| HCC (Hepatocellular Carcinoma) | C220, C228, C229 | |

| Procedure Codes | EGD (Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy) | 0DJ08ZZ, 0D983ZX, 0D958ZX, 0DJ08ZZ, 0D953ZX, 0DJ68ZZ, 0D963ZX, 0DJ07ZZ, 0D568ZZ, 0D578ZZ, 0D588ZZ, 0D598ZZ, 0D5A8ZZ, 0D718ZZ, 0D728ZZ, 0D738ZZ, 0D748ZZ, 0D758ZZ, 0D768ZZ, 0D778ZZ, 0D788ZZ, 0D798ZZ, 0D7A8ZZ, 0D718DZ, 0D728DZ, 0D738DZ, 0D748DZ, 0D758DZ, 0D768DZ, 0D778DZ, 0D788DZ, 0D798DZ, 0D7A8DZ, 0D9180Z, 0D918ZX, 0D918ZZ, 0D9280Z, 0D928ZX, 0D928ZZ, 0D9380Z, 0D938ZX, 0D938ZZ, 0D9480Z, 0D948ZX, 0D948ZZ, 0D9580Z, 0D958ZX, 0D958ZZ, 0D9680Z, 0D968ZX, 0D968ZZ, 0D9780Z, 0D978ZX, 0D978ZZ, 0D9880Z, 0D988ZX, 0D988ZZ, 0D9980Z, 0D998ZX, 0D998ZZ, 0D9A80Z, 0D9A8ZX, 0D9A8ZZ, 0DB18ZX, 0DB18ZZ, 0DB28ZX, 0DB28ZZ, 0DB38ZX, 0DB38ZZ, 0DB48ZX, 0DB48ZZ, 0DB58ZX, 0DB58ZZ, 0DB68ZX, 0DB68ZZ, 0DB78ZX, 0DB78ZZ, 0DB88ZX, 0DB88ZZ, 0DB98ZX, 0DB98ZZ, 0DBA8ZX, 0DBA8ZZ, 0DC18ZZ, 0DC28ZZ, 0DC38ZZ, 0DC48ZZ, 0DC58ZZ, 0DC68ZZ, 0DC78ZZ, 0DC88ZZ, 0DC98ZZ, 0DCA8ZZ, 0DJ08ZZ, 06L30ZZ, 0D554ZZ, 0D518ZZ, 0D528ZZ, 0D538ZZ, 0D548ZZ, 0D558ZZ, 0D568ZZ, 0W3P8ZZ, 3E0G8TZ, 0DQ78ZZ, 0DQ68ZZ, 0DQ28ZZ, 0DQ38ZZ, 0DQ58ZZ, 0DQ48ZZ, 06L38CZ, 06L34CZ, 06L38ZZ, 3E0G8GC, 06L28CZ, 06L28ZZ, 0DL57DZ, 0DL58DZ |

| TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) * | 06183J4, 06184J4, 06183JY, 061847Y, 061849Y, 06184AY, 06184JY, 06184KY, 06184ZY, 06183DY, 06184DY | |

| Hemodialysis and CRRT | Z992, Z4901, Z4931, 5A1D00Z, 5A1D60Z, 5A1D70Z, 5A1D80Z, 5A1D90Z | |

| Liver Tx (Liver transplantation) | 0FY00Z0, 0FY00Z1, 0FY00Z2 | |

| RBC Tx (Red Blood Cell Transfusion) | 30233N1, 30243N1, 30233N0, 30233P0, 30233P1 | |

| Platelets Tx (Platelets Transfusion) | 30233R1, 30243R1, 30230R0 | |

| FFP Tx (Fresh Frozen Plasma Transfusion) | 30233K1, 30243K1, 30233K0, 30233L0, 30233L1 | |

| Exclusion Codes | Heart Failure ** | 39891, 40211, 40291, 40401, 40411, 40403, 40413, 40491, 40493, 428x, I0981, I110, I130, I132, I50 |

| Complication | Procedure | Chi2 | P_Chi2 | OR | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | P_OR | Category1 | Category2 | ASPR_C1 | ASPR_C2 |

| VH | EGD | 57.976 | 1.59E-12 | 1.101 | 1.023 | 1.184 | 1.027E-02 | Other | White | 863.208 | 851.616 |

| VH | EGD | 57.976 | 1.59E-12 | 1.003 | 0.957 | 1.052 | 8.967E-01 | Hispanic | White | 851.639 | 851.616 |

| VH | EGD | 57.976 | 1.59E-12 | 1.275 | 1.183 | 1.374 | 0.000E+00 | White | Black | 851.616 | 817.863 |

| VH | EGD | 57.976 | 1.59E-12 | 1.097 | 1.013 | 1.189 | 2.310E-02 | Other | Hispanic | 863.208 | 851.639 |

| VH | EGD | 57.976 | 1.59E-12 | 1.403 | 1.272 | 1.549 | 0.000E+00 | Other | Black | 863.208 | 817.863 |

| VH | EGD | 57.976 | 1.59E-12 | 1.279 | 1.179 | 1.387 | 0.000E+00 | Hispanic | Black | 851.639 | 817.863 |

| Complication | Procedure | Chi2 | P_Chi2 | OR | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | P_OR | Category1 | Category2 | ASPR_C1 | ASPR_C2 |

| VH | TIPS | 36.676 | 5.39E-08 | 1.236 | 1.138 | 1.342 | 4.500E-07 | White | Hispanic | 51.346 | 41.531 |

| VH | TIPS | 36.676 | 5.39E-08 | 0.999 | 0.891 | 1.121 | 9.926E-01 | White | Other | 51.346 | 50.539 |

| VH | TIPS | 36.676 | 5.39E-08 | 1.199 | 1.042 | 1.379 | 1.124E-02 | White | Black | 51.346 | 42.032 |

| VH | TIPS | 36.676 | 5.39E-08 | 1.237 | 1.086 | 1.409 | 1.355E-03 | Other | Hispanic | 50.539 | 41.531 |

| VH | TIPS | 36.676 | 5.39E-08 | 1.031 | 0.885 | 1.201 | 6.928E-01 | Black | Hispanic | 42.032 | 41.531 |

| VH | TIPS | 36.676 | 5.39E-08 | 1.199 | 1.009 | 1.425 | 3.886E-02 | Other | Black | 50.539 | 42.032 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 121.43 | 3.79E-26 | 1.160 | 1.085 | 1.239 | 1.159E-05 | White | Hispanic | 15.060 | 12.974 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 121.43 | 3.79E-26 | 1.148 | 1.040 | 1.266 | 6.037E-03 | White | Other | 15.060 | 13.151 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 121.43 | 3.79E-26 | 1.776 | 1.579 | 1.997 | 0.000E+00 | White | Black | 15.060 | 8.506 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 121.43 | 3.79E-26 | 1.010 | 0.904 | 1.130 | 8.559E-01 | Other | Hispanic | 13.151 | 12.974 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 121.43 | 3.79E-26 | 1.531 | 1.347 | 1.741 | 0.000E+00 | Hispanic | Black | 12.974 | 8.506 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 121.43 | 3.79E-26 | 1.547 | 1.335 | 1.794 | 1.000E-08 | Other | Black | 13.151 | 8.506 |

| Complication | Procedure | Chi2 | P_Chi2 | OR | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | P_OR | Category1 | Category2 | ASPR_C1 | ASPR_C2 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 476.46 | 6.02E-103 | 1.304 | 1.256 | 1.354 | 0.000E+00 | Other | White | 103.026 | 80.990 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 476.46 | 6.02E-103 | 1.241 | 1.208 | 1.275 | 0.000E+00 | Hispanic | White | 98.836 | 80.990 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 476.46 | 6.02E-103 | 1.191 | 1.154 | 1.229 | 0.000E+00 | Black | White | 95.413 | 80.990 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 476.46 | 6.02E-103 | 1.051 | 1.007 | 1.096 | 2.191E-02 | Other | Hispanic | 103.026 | 98.836 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 476.46 | 6.02E-103 | 1.095 | 1.046 | 1.146 | 9.100E-05 | Other | Black | 103.026 | 95.413 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 476.46 | 6.02E-103 | 1.042 | 1.004 | 1.082 | 2.973E-02 | Hispanic | Black | 98.836 | 95.413 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 45.27 | 1.71E-11 | 1.068 | 1.047 | 1.090 | 0.000E+00 | Male | Female | 89.040 | 83.711 |

| Complication | Procedure | Chi2 | P_Chi2 | OR | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | P_OR | Category1 | Category2 | ASPR_C1 | ASPR_C2 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 234.39 | 1.55E-50 | 1.021 | 0.971 | 1.074 | 0.414 | White | Hispanic | 12.35 | 12.18 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 234.39 | 1.55E-50 | 1.183 | 1.105 | 1.267 | 0.000 | Other | White | 14.56 | 12.35 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 234.39 | 1.55E-50 | 1.674 | 1.548 | 1.811 | 0.000 | White | Black | 12.35 | 7.36 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 234.39 | 1.55E-50 | 1.208 | 1.117 | 1.307 | 0.000 | Other | Hispanic | 14.56 | 12.18 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 234.39 | 1.55E-50 | 1.640 | 1.502 | 1.790 | 0.000 | Hispanic | Black | 12.18 | 7.36 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 234.39 | 1.55E-50 | 1.981 | 1.795 | 2.187 | 0.000 | Other | Black | 14.56 | 7.36 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 51.84 | 6.04E-13 | 1.147 | 1.104 | 1.193 | 0.000 | Male | Female | 12.60 | 11.02 |

| Complication | Procedure | Chi2 | P_Chi2 | OR | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | P_OR | Category1 | Category2 | ASPR_C1 | ASPR_C2 |

| VH | EGD | 48.83 | 1.42E-10 | 1.116 | 1.063 | 1.171 | 9.000E-06 | Medicaid | Medicare | 852.45 | 839.22 |

| VH | EGD | 48.83 | 1.42E-10 | 1.196 | 1.135 | 1.260 | 0.000E+00 | Private/HMO | Medicare | 861.39 | 839.22 |

| VH | EGD | 48.83 | 1.42E-10 | 1.101 | 1.034 | 1.172 | 2.690E-03 | Other | Medicare | 851.95 | 839.22 |

| VH | EGD | 48.83 | 1.42E-10 | 1.072 | 1.016 | 1.131 | 1.071E-02 | Private/HMO | Medicaid | 861.39 | 852.45 |

| VH | EGD | 48.83 | 1.42E-10 | 1.014 | 0.952 | 1.080 | 6.739E-01 | Medicaid | Other | 852.45 | 851.95 |

| VH | EGD | 48.83 | 1.42E-10 | 1.087 | 1.017 | 1.161 | 1.459E-02 | Private/HMO | Other | 861.39 | 851.95 |

| Complication | Procedure | Chi2 | P_Chi2 | OR | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | P_OR | Category1 | Category2 | ASPR_C1 | ASPR_C2 |

| VH | TIPS | 96.19 | 1.02E-20 | 1.055 | 0.972 | 1.145 | 1.988E-01 | Private/HMO | Medicaid | 56.19 | 53.39 |

| VH | TIPS | 96.19 | 1.02E-20 | 1.388 | 1.273 | 1.514 | 0.000E+00 | Private/HMO | Medicare | 56.19 | 42.18 |

| VH | TIPS | 96.19 | 1.02E-20 | 1.557 | 1.385 | 1.750 | 0.000E+00 | Private/HMO | Other | 56.19 | 37.65 |

| VH | TIPS | 96.19 | 1.02E-20 | 1.316 | 1.212 | 1.429 | 0.000E+00 | Medicaid | Medicare | 53.39 | 42.18 |

| VH | TIPS | 96.19 | 1.02E-20 | 1.476 | 1.317 | 1.654 | 0.000E+00 | Medicaid | Other | 53.39 | 37.65 |

| VH | TIPS | 96.19 | 1.02E-20 | 1.121 | 0.997 | 1.261 | 5.616E-02 | Medicare | Other | 42.18 | 37.65 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 119.42 | 1.03E-25 | 1.005 | 0.945 | 1.067 | 8.838E-01 | Medicare | Medicaid | 13.84 | 13.61 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 119.42 | 1.03E-25 | 1.214 | 1.142 | 1.292 | 0.000E+00 | Private/HMO | Medicare | 16.68 | 13.84 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 119.42 | 1.03E-25 | 1.358 | 1.232 | 1.496 | 0.000E+00 | Medicare | Other | 13.84 | 10.28 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 119.42 | 1.03E-25 | 1.220 | 1.145 | 1.300 | 0.000E+00 | Private/HMO | Medicaid | 16.68 | 13.61 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 119.42 | 1.03E-25 | 1.351 | 1.225 | 1.491 | 0.000E+00 | Medicaid | Other | 13.61 | 10.28 |

| Ascites | TIPS | 119.42 | 1.03E-25 | 1.649 | 1.493 | 1.820 | 0.000E+00 | Private/HMO | Other | 16.68 | 10.28 |

| Complication | Procedure | Chi2 | P_Chi2 | OR | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | P_OR | Category1 | Category2 | ASPR_C1 | ASPR_C2 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 1706.49 | 0.00E+00 | 1.544 | 1.505 | 1.584 | 0.000E+00 | Private or HMO | Medicare | 107.895 | 72.939 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 1706.49 | 0.00E+00 | 1.468 | 1.432 | 1.505 | 0.000E+00 | Medicaid | Medicare | 103.289 | 72.939 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 1706.49 | 0.00E+00 | 1.026 | 0.984 | 1.070 | 2.287E-01 | Other | Medicare | 75.104 | 72.939 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 1706.49 | 0.00E+00 | 1.052 | 1.022 | 1.082 | 4.470E-04 | Private or HMO | Medicaid | 107.895 | 103.289 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 1706.49 | 0.00E+00 | 1.504 | 1.439 | 1.572 | 0.000E+00 | Private or HMO | Other | 107.895 | 75.104 |

| HRS or AKI | HD | 1706.49 | 0.00E+00 | 1.430 | 1.369 | 1.494 | 0.000E+00 | Medicaid | Other | 103.289 | 75.104 |

| Complication | Procedure | Chi2 | P_Chi2 | OR | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | P_OR | Category1 | Category2 | ASPR_C1 | ASPR_C2 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 6850.82 | 0.00E+00 | 3.859 | 3.660 | 4.068 | 0.000 | Private or HMO | Medicaid | 29.81 | 7.83 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 6850.82 | 0.00E+00 | 1.042 | 0.984 | 1.103 | 0.158 | Medicaid | Medicare | 7.83 | 7.56 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 6850.82 | 0.00E+00 | 1.116 | 1.017 | 1.224 | 0.021 | Medicaid | Other | 7.83 | 6.94 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 6850.82 | 0.00E+00 | 4.021 | 3.848 | 4.201 | 0.000 | Private or HMO | Medicare | 29.81 | 7.56 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 6850.82 | 0.00E+00 | 4.305 | 3.954 | 4.688 | 0.000 | Private or HMO | Other | 29.81 | 6.94 |

| D. Cirrhosis | Liver Tx | 6850.82 | 0.00E+00 | 1.071 | 0.981 | 1.169 | 0.128 | Medicare | Other | 7.56 | 6.94 |

References

- Huang, D.Q.; Terrault, N.A.; Tacke, F.; Gluud, L.L.; Arrese, M.; Bugianesi, E.; Loomba, R. Global epidemiology of cirrhosis - aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, A.M.; Singal, A.G.; Tapper, E.B. Contemporary Epidemiology of Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis. Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA; Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; Gastroenterology Section, Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

- Nephew, L.D.; Knapp, S.M.; Mohamed, K.A.; et al. Trends in Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Receipt of Lifesaving Procedures for Hospitalized Patients With Decompensated Cirrhosis in the US, 2009-2018. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2324539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G. C., Thuluvath, P. J., & Thuluvath, A. J. (2020). Racial disparities in liver disease: Implications for hepatitis C virus screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. [CrossRef]

- Tapper, E. B., & Saini, S. D. (2021). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Chronic Liver Disease and Hepatitis C. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D.E.; Ripoll, C.; Thiele, M.; Fortune, B.E.; Simonetto, D.A.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Bosch, J. AASLD Practice Guidance on risk stratification and management of portal hypertension and varices in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2024, 79, 1180–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Renal Data System. 2022 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2022. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://usrds-adr.niddk.nih.gov/2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).