1. Introduction

Migraine is a complex neurological disease with a wide range of genetic and environmental risk factors and significant phenotypic variability [

1]. Migraine is the second-common cause of years lived with disability globally and the most common disability among women under 50 [

2]. Analysis of data from 204 countries in the 2019 Global Burden of Disease study revealed a global prevalence of 1.1 billion migraine cases [

3].

Migraine is generally divided into two groups based on the monthly number of headache days. Episodic migraine (EM) is characterized by fewer than 15 headaches per month, while chronic migraine (CM) is defined by 15 or more headache days per month for at least three months, with at least eight of those days being attributed to migraine [

4]. CM affects 1.4% to 2.2% of the general population [

5] and approximately 8% of migraineurs [

6]. Annually, 2.5% of patients with EM develop new-onset CM [

7]. The etiology of migraine chronification is not entirely understood; however, it has been suggested that either increased excitability of the trigeminal nociceptive pathways or the development of central sensitization play a role [

8,

9]. Additionally, many studies have identified risk factors for chronic migraine, which have been summarized in various reviews [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

The incidence of certain diseases is higher among patients with migraine compared to the general population [

15]. Patients with CM, compared to those with EM, have shown higher frequencies of comorbid conditions in both clinic- and population-based research [

15,

16]. Comorbidity and patterns of disease expression can provide information about the possible mechanisms of the disease [

17].

The exact contribution of a family history of migraine to the development of CM remains unknown. This study aimed to fill this critical gap by examining the effect of both maternal and paternal transmission of comorbid medical conditions on the phenotype of CM. Unlike previous research that has primarily focused on individual risk factors, our approach considered the combined genetic load from both parents, offering a comprehensive understanding of the hereditary patterns that may predispose individuals to CM.

By focusing on the familial dimensions of migraine, our research aims to pave the way for advancements in predictive models and personalized treatment strategies, ultimately contributing to the better management and prevention of this incapacitating condition. Through detailed genetic analysis, we hope to uncover nuanced insights into the interplay between genetic predispositions and environmental factors, offering new avenues for therapeutic interventions.

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Design and Participants

The study included a cohort of patients with EM and CM. Data were collected from June 2017 to May 2023. A total of 500 patients with migraine were recruited from the Brain 360 Integrative Brain Health Headache Clinic. Based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 criteria, patients were diagnosed with migraine and categorized as having either EM or CM. Medication overuse was defined as regular overuse of acute migraine treatment for >3 months, including acetylsalicylic acid, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and acetaminophen [paracetamol] for 15 or more days per month, or ergotamines, triptans, opioids, or combination analgesics for 10 or more days per month [

4].

2.2. Data Collection

Data were systematically collected on headache frequency, characteristics, and associated symptoms such as aura, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia, and allodynia. Additional recorded parameters included greater occipital nerve tenderness, supraorbital/supratrochlear tenderness, and shoulder neck tenderness. The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used to assess headache intensity. Information was also gathered on demographic variables, body mass index (BMI), educational status, migraine onset age, and medication-free attack duration. Specific emphasis was placed on the familial history of headache and comorbid conditions in both mothers and fathers to assess potential genetic influences.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted following the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee for Clinical Studies of Baskent University (KA23/416). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 22. Initial tests for the normality of data distribution included the Kolmogorov-Smirnov, skewness, and kurtosis tests. Depending on the data distribution, parametric (independent-samples t-test) or non-parametric (chi-square test) methods were employed to compare the two migraine groups. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. The associations between familial history and migraine phenotypes were particularly examined to explore the hereditary influence.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 500 participants were enrolled in the study, comprising 421 females (84.2%) and 79 males (15.8%). Among these, 315 (63%) were diagnosed with EM and 185 (37%) with CM. The mean age of onset for CM was slightly higher than that for EM, although this difference was not statistically significant.

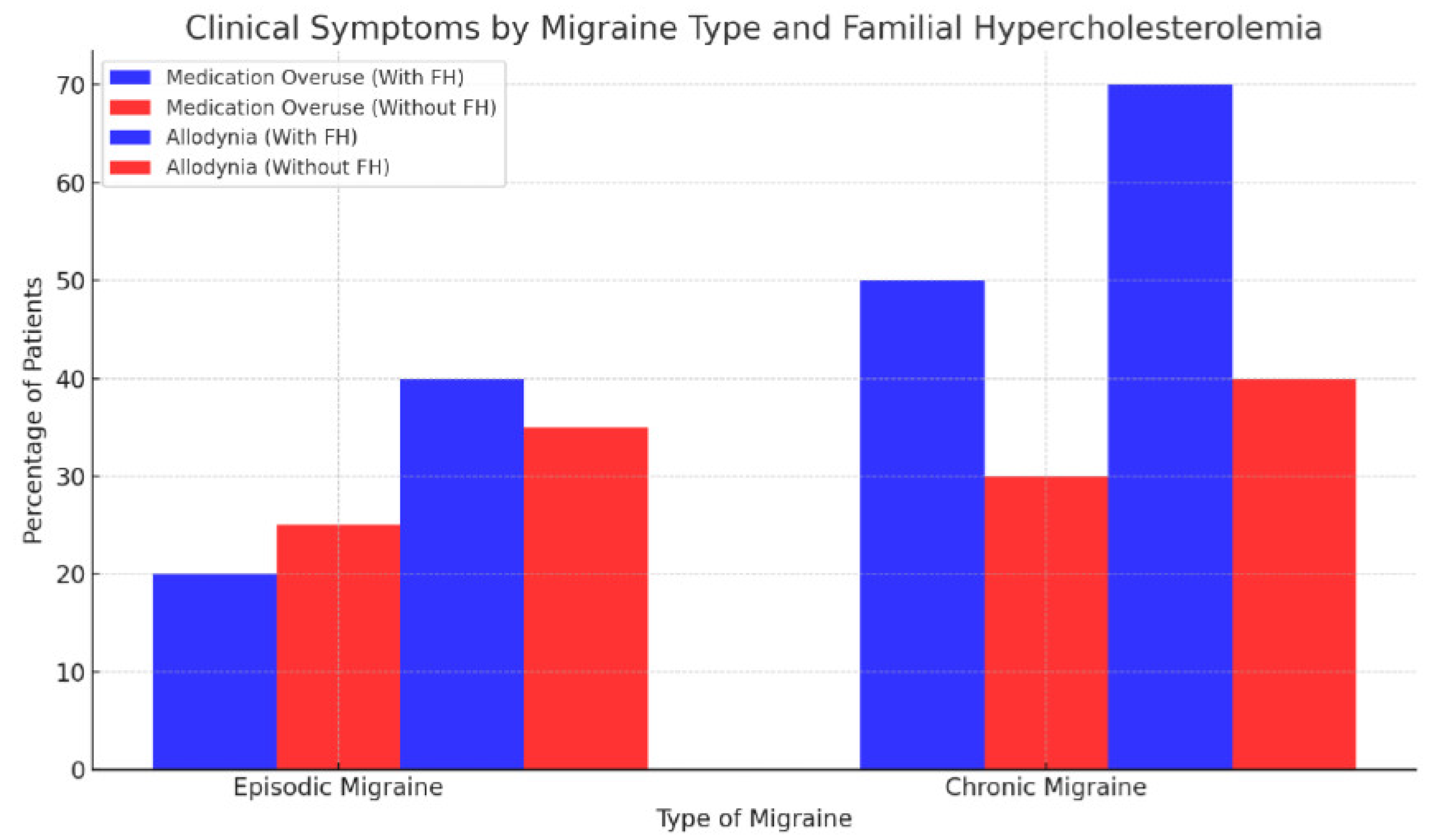

Table 1 presents the demographic data of the patients.

3.2. Headache Characteristics and Comorbidities

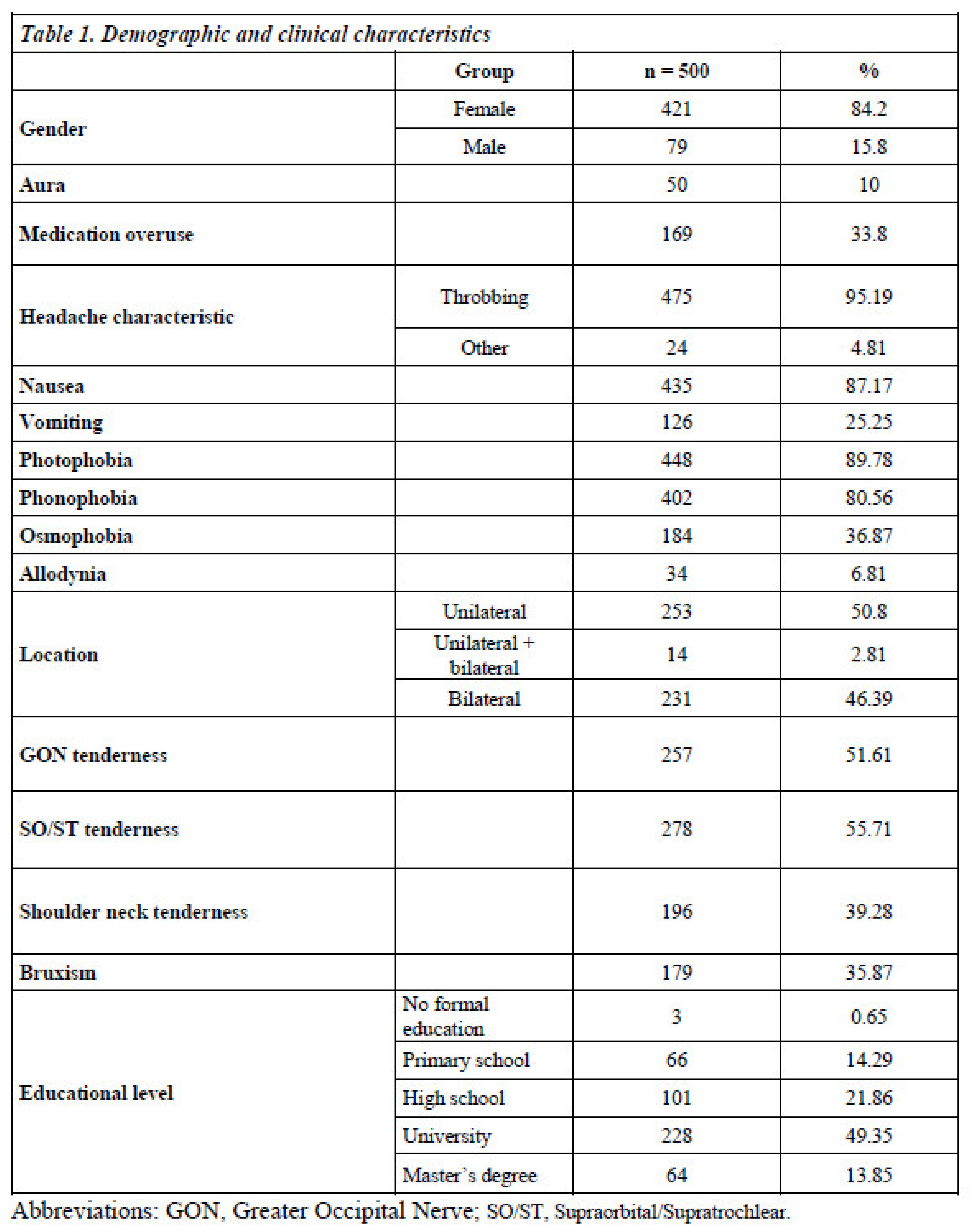

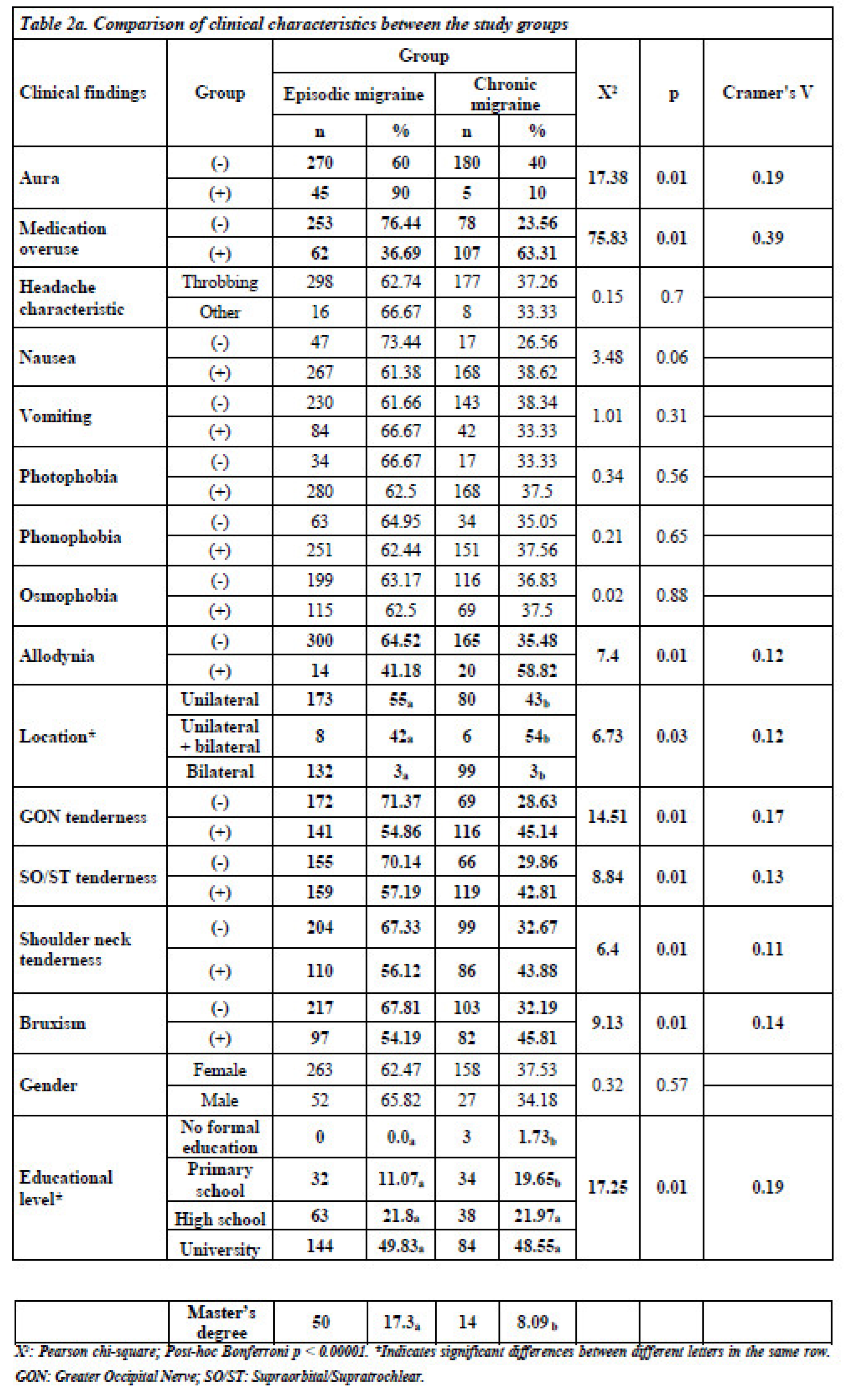

The analysis revealed significant differences in headache characteristics between the two groups. Patients with CM were more likely to have medication overuse (63.31% vs. 23.56%, p < 0.05), and allodynia (58.82% vs. 35.48%, p < 0.05). Bilateral headache presence and greater occipital nerve tenderness were also more commonly observed in the CM group compared to the EM group (p < 0.05). However, supraorbital/supratrochlear tenderness and shoulder/neck tenderness were found to be similar (p < 0.05).

There was no statistically significant difference between patients with EM and those with CM in terms of headache character, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia, or gender (p > 0.05) (

Table 2a).

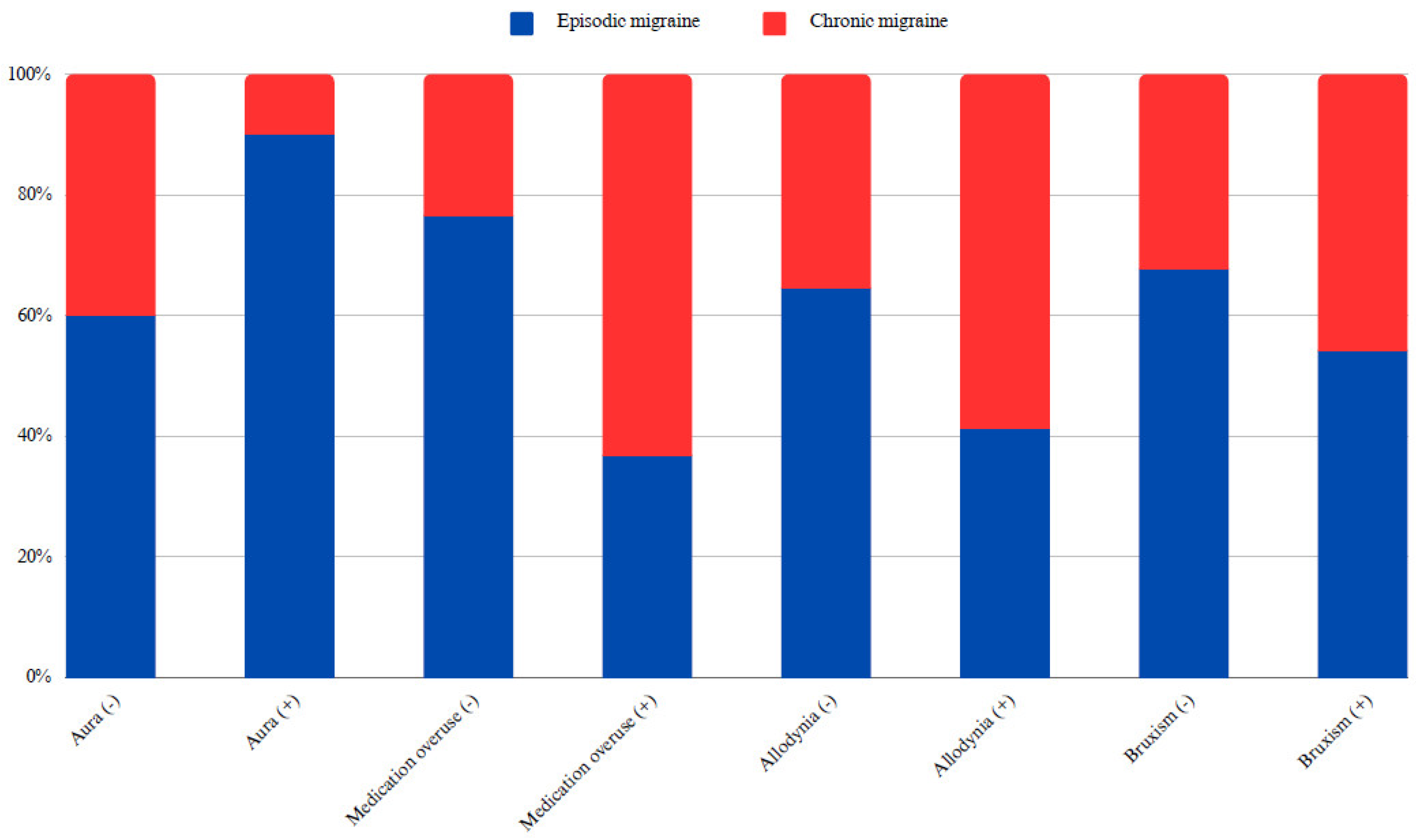

Of the 500 patients included in the study, 50 had auras. While 60% of migraineurs without aura had EM and 40% had CM, 90% of those with aura had EM and 10% had CM, indicating a statistically significant difference (X

2: 17.38; p < 0.05, Cramer’s V: 0.19). In addition, the rate of CM diagnosis was 32.19% in individuals without bruxism and 45.81% in those with bruxism, which was also statistically significant (X

2: 9.13; p < 0.05, Cramer’s V: 0.14) (

Figure 1). However, there were no statistically significant differences between the EM and CM groups in terms of age of onset, pain intensity, or BMI. Considering the average values, the duration of medication-free attacks and age were lower in patients with EM than in those with CM (p < 0.05) (

Table 2b).

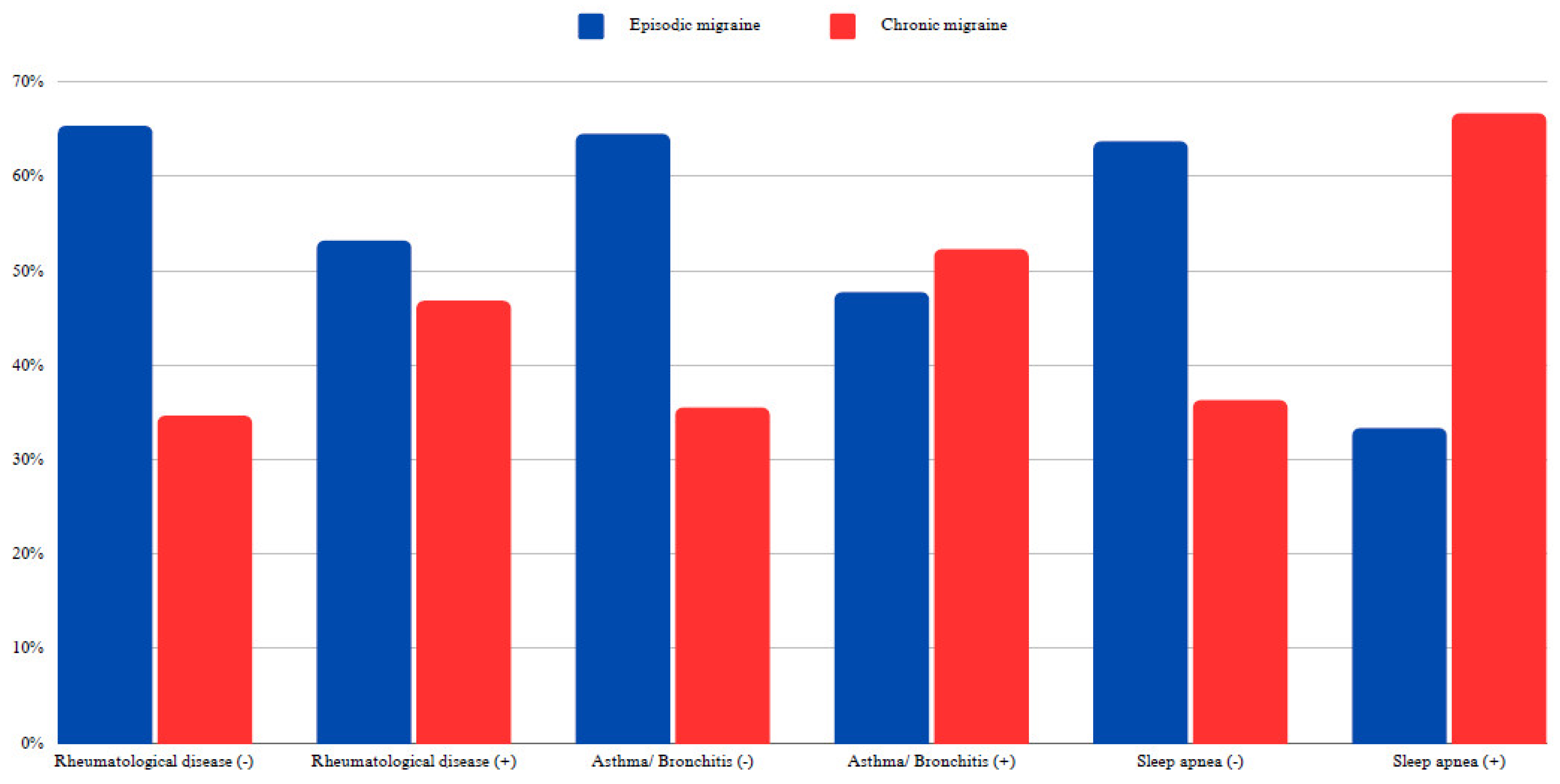

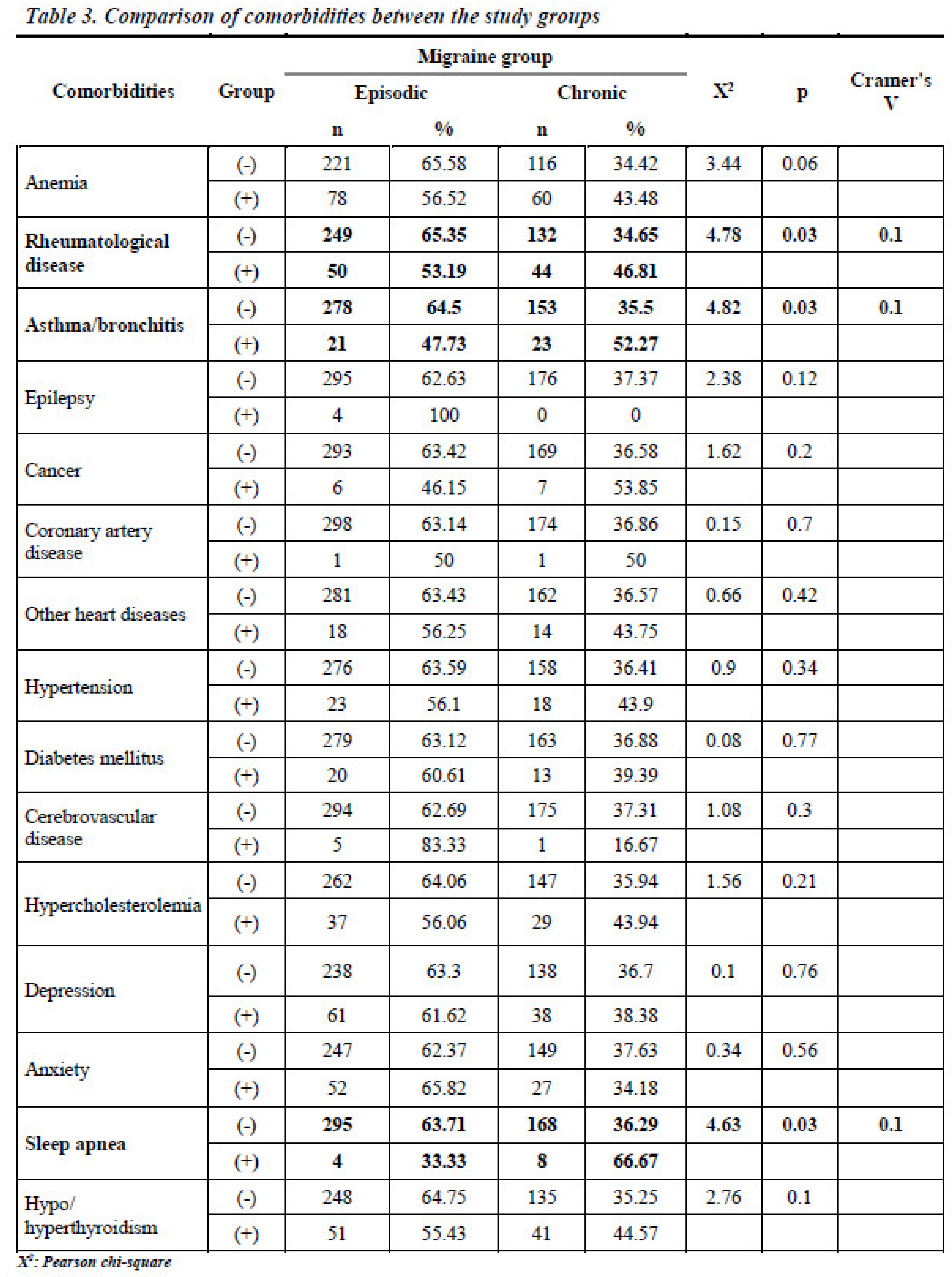

No statistically significant differences were found between the EM and CM groups regarding the presence of anemia, epilepsy, cancer, coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, hypercholesterolemia, depression, anxiety, or thyroid dysfunction (p > 0.05) (

Table 3). Chronic migraine was diagnosed in 46.81% of individuals with rheumatological disease, compared to 34.65% of those without this comorbidity. This difference was statistically significant (X

2: 4.78; p < 0.05, Cramer’s V: 0.1). Similarly, while 35.5% of patients without a diagnosis of asthma-bronchitis were diagnosed with CM, 52.27% of those with a diagnosis of asthma-bronchitis were diagnosed with CM (X

2:4.82; p < 0.05, Cramer’s V: 0.1).

CM was observed in 36.29% of patients without sleep apnea and 66.67% of those with sleep apnea (X

2: 4.63; p < 0.05, Cramer’s V: 0.1) (

Figure 2).

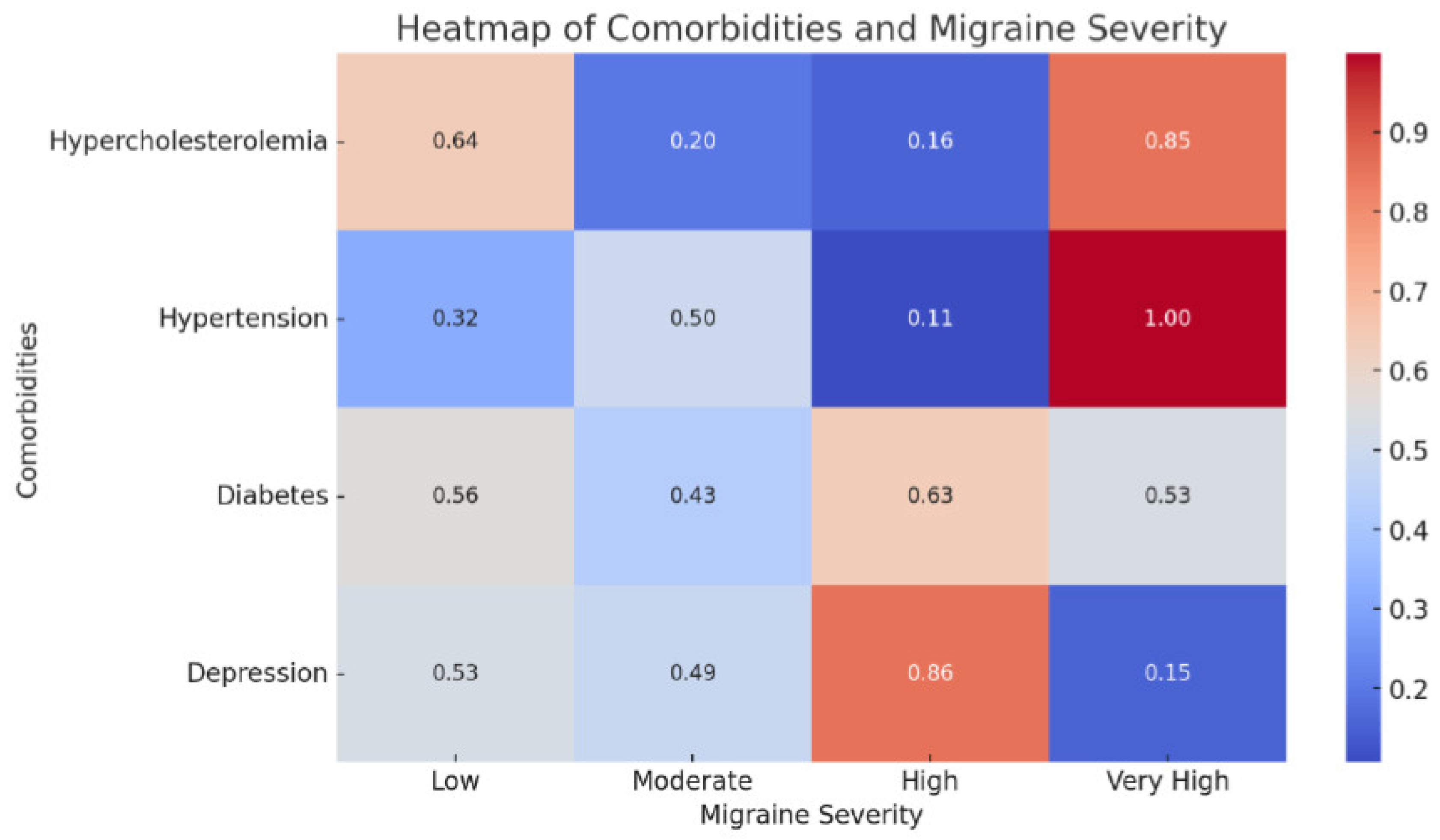

The heatmap depicting the relationship between comorbidities and migraine severity revealed a strong correlation between conditions such as hypercholesterolemia and depression, and higher degrees of migraine severity (

Figure 3).

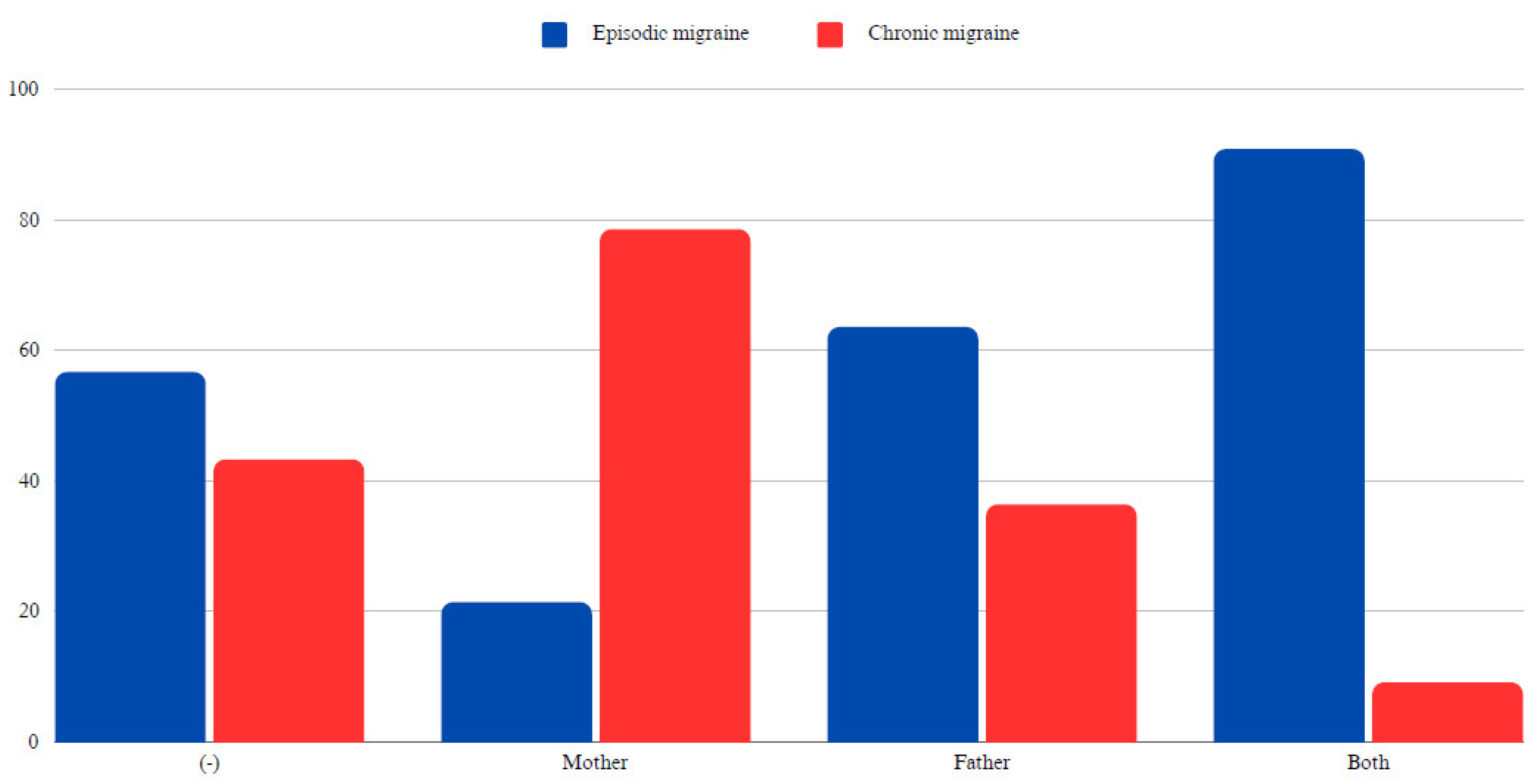

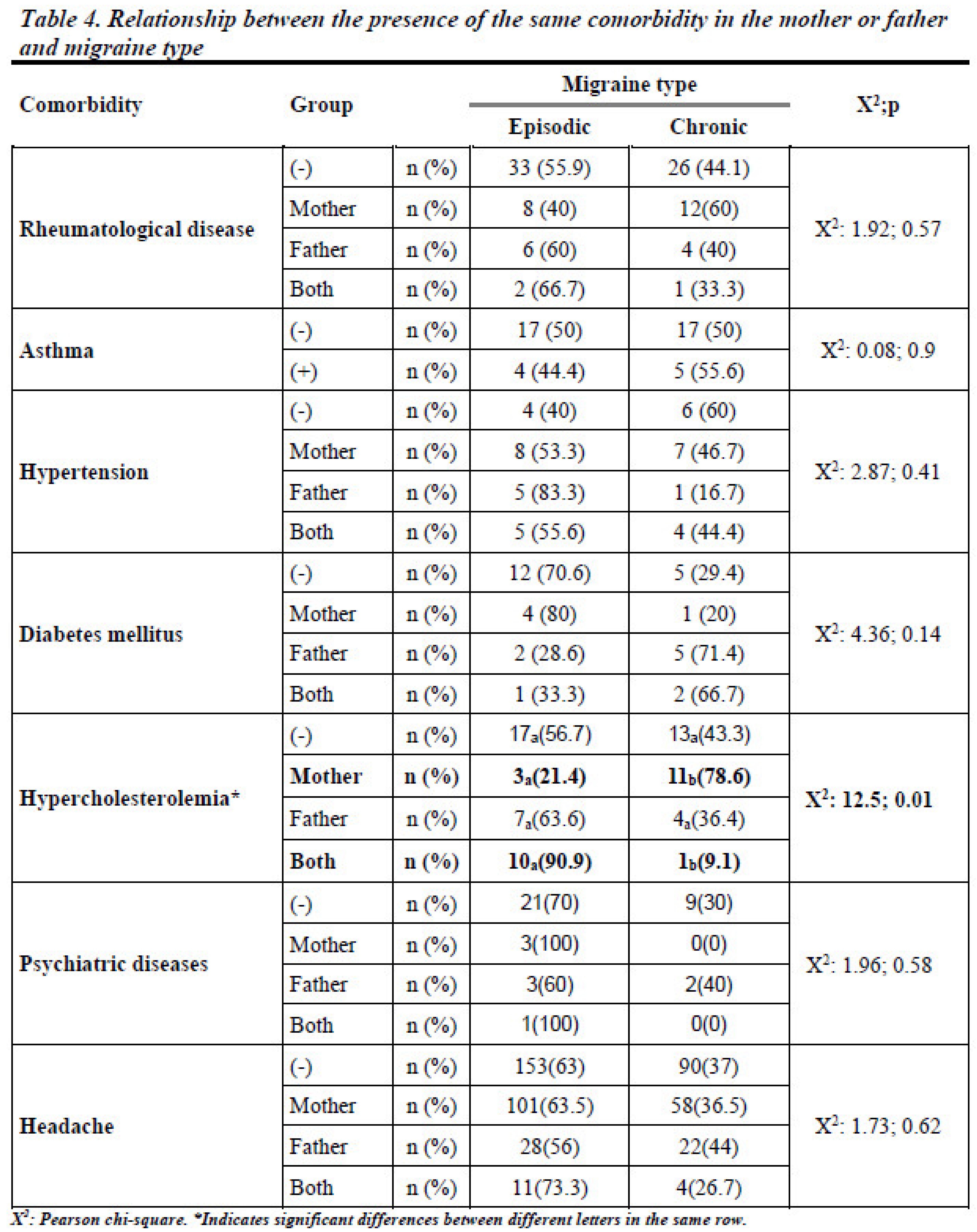

3.3. Familial Influence on Migraine Development

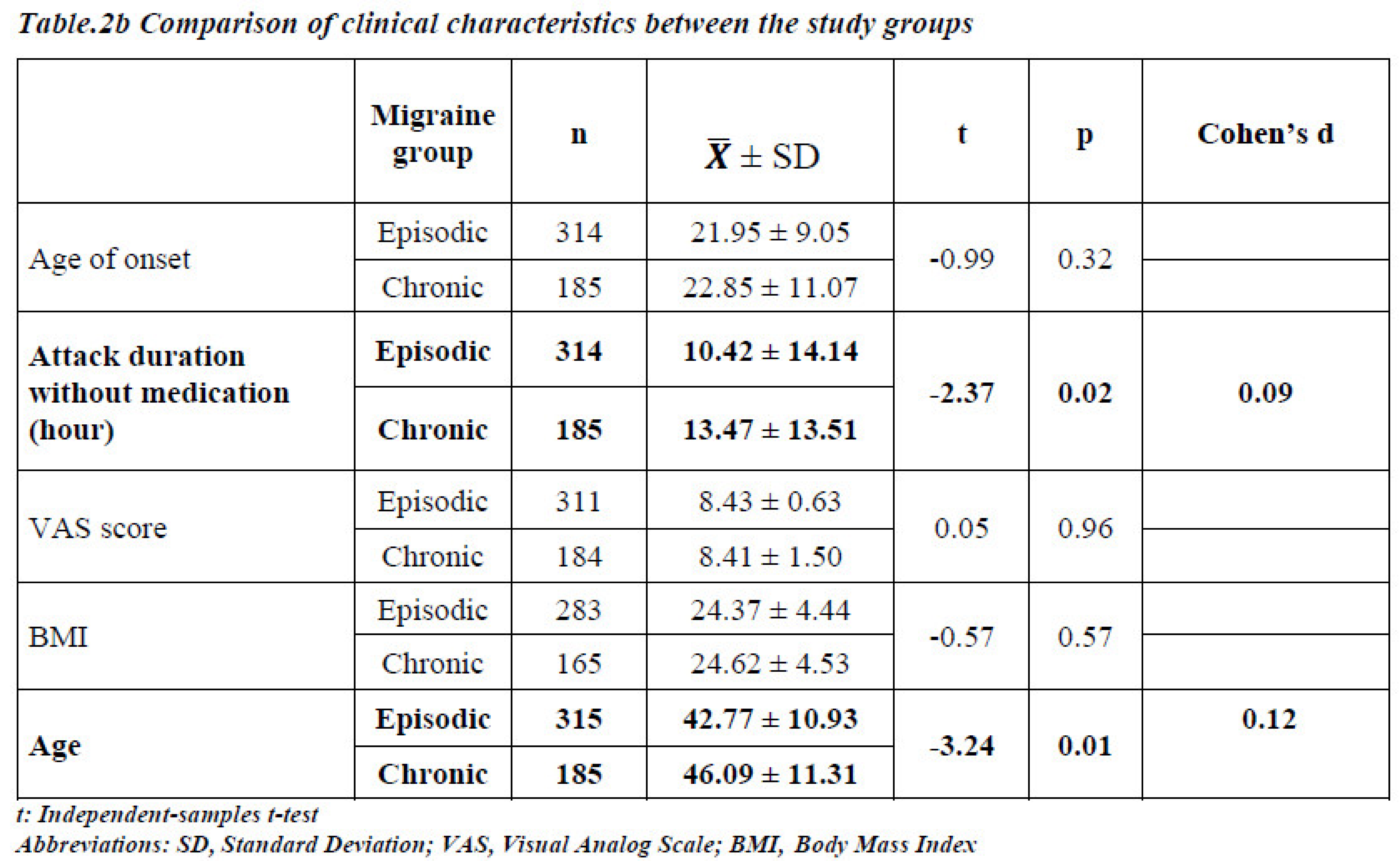

When examining familial influences, no significant statistical difference was found in migraine occurrence based on the presence of the same comorbidities in parents (p > 0.05). However, the presence of hypercholesterolemia in the mother significantly increased the likelihood of CM in the offspring (78.6% in patients whose mothers had hypercholesterolemia vs. 43.3% in those without such a family history, p < 0.05). Detailed data are given in

Table 4 and

Figure 4.

3.4. Educational Levels and Migraine Phenotypes

A statistically significant relationship was found between educational level and migraine phenotype (p < 0.05). Among participants, all the uneducated individuals (n = 3) and 51.52% of those with only primary school education (n = 34) had CM. In contrast, 62.38% (n = 63) of individuals with high school education, 63.16% (n = 144) of those with university education, and 78.13% (n = 50) of those with a master’s degree had EM. These findings suggest that individuals with higher education levels were less likely to have CM, indicating that socioeconomic factors may play a role in migraine chronification (

Table 2a).

Symptoms such as allodynia and medication overuse were more common in CM patients with familial hypercholesterolemia than in those without this hereditary condition (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

This study highlights the complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors in the development of CM. The significant correlation of CM with factors such as medication overuse, allodynia, bilateral headaches, and greater occipital nerve tenderness aligns with previous research emphasizing the multifactorial nature of migraine progression[

7,

18].

4.1. Familial Influence on Migraine Development

Our findings regarding the familial transmission of hypercholesterolemia provide new insights into the genetic underpinnings of migraine. The significant association between maternal hypercholesterolemia and CM suggests a potential sex-linked genetic influence on migraine susceptibility. This observation warrants further genetic studies to explore mechanisms such as mitochondrial DNA variations, which are maternally inherited and may play a role in migraine pathophysiology. However, it is also essential to acknowledge that our study lacks detailed information on specific lipid profiles (including high-density lipoprotein, low-density protein, and very-low-density protein), triglyceride levels, and the treatment status of patients with hypercholesterolemia, which could provide valuable insights into the nuanced nature of this association, as different lipid subtypes may exert varying effects on vascular and neurological functions [

19].

In this study, the examination of various comorbidities in parents, including headache, rheumatological diseases, asthma, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and psychiatric diseases, in relation to CM in patients revealed that these parental comorbidities did not have statistically significant associations with CM in their offspring. An important consideration in interpreting these results is the lack of knowledge about the specific medications used, adherence to treatment regimens, or the overall management and control of these comorbid conditions among the participants. The absence of such details limits the comprehensive understanding of the impact of parental comorbidities on chronic migraine risk in patients[

20].

This study also found a higher incidence of CM in patients with rheumatological disease, asthma/bronchitis, and sleep apnea. These findings are consistent with the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study, which identified arthritis, asthma/bronchitis, and insomnia as risk factors for migraine chronification, although results differed for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, depression, and anxiety [

21]. The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes study similarly detected a higher prevalence of sleep apnea among respondents with CM compared to those with EM [

22].

Our examination of clinical characteristics revealed several intriguing patterns in migraine chronification. In particular, medication overuse, allodynia, bilateral location, and bruxism showed significant associations with CM. Tenderness in various regions was also linked to CM. These findings align with existing literature, highlighting the relevance of these clinical features in identifying individuals at risk for migraine chronification. For example, Ford et al. reported that individuals with CM experienced bilateral pain more frequently [

18]. In our study, individuals with chronic migraine also had higher rates of phonophobia, photophobia, and nausea, although the differences were not statistically significant.

Previous studies have often suggested that individuals with obesity, typically defined as a BMI of ≥30 kg/m², may have an increased risk of developing CM [

17,

23]. Overweight individuals, with a BMI ranging from 25 to 29 kg/m², were reported to have a threefold increased risk compared to those with a normal weight [

23]. In contrast to some expectations and consistent with certain aspects of the literature, this study did not find a significant difference in BMI between patients with EM and those with CM. The BMI values of patients in both groups were below the threshold of 30 kg/m², indicating that none of the study participants were classified as obese. However, BMI does not provide information about the distribution of body fat, muscle mass, or other factors that may influence the complex relationship between weight and migraine. The absence of a clear BMI distinction between EM and CM groups emphasizes the multifactorial nature of migraine chronification, with genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors playing intricate roles.

The visual representations of our data provide compelling insights into the progression and characteristics of migraine. The clustered bar chart elucidated the significant variation in clinical symptoms such as medication overuse and allodynia between patients with EM and CM, particularly highlighting the influence of familial hypercholesterolemia. This suggests a genetic predisposition that exacerbates these symptoms in chronic migraineurs.

The heatmap of comorbidities and migraine severity showed the diverse impact of various comorbid conditions on migraine severity. Notably, conditions such as hypercholesterolemia and depression appeared closely linked to higher severity levels, indicating potential areas for targeted therapeutic intervention. Together, these figures not only underscore the complex interaction between genetics, comorbidities, and migraine progression but also highlight potential focal points for improving management strategies for patients with migraine.

4.2. Educational and Socioeconomic Factors

The relationship between educational level and the prevalence of CM observed in our study underscores the complex interplay of socioeconomic factors in migraine pathophysiology [

10,

21,

24,

25,

26]. Conducted in a private tertiary headache clinic, this study offers insights that might reflect a demographic with access to specialized healthcare services, which may have influenced the observed outcomes. Unlike findings from some studies conducted in North America, where lower educational and socioeconomic status are associated with a higher prevalence of migraine, our results align more closely with European studies suggesting that higher socioeconomic status correlates with a reduced migraine frequency. This divergence may reflect regional differences in stress management and healthcare access, which could significantly influence migraine chronification [

10,

21,

24,

25,

26].

In our cohort, the inverse relationship between educational level and CM supports literature indicating that individuals with lower educational levels are more prone to developing CM [

27]. This association prompts further investigation into how educational status may impact health literacy, access to care, and ultimately, migraine management outcomes. Interestingly, our findings did not align with previous research demonstrating a higher incidence of anxiety and depression among CM sufferers compared to those with EM [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. This discrepancy suggests that the interplay between migraine and psychological conditions might also be influenced by socioeconomic variables, which were not specifically addressed in our study [

33,

34].

Previous studies, particularly those from the USA, have consistently demonstrated an inverse relationship between socioeconomic status and migraine prevalence, with lower income groups experiencing higher rates of migraine. These studies suggest that socioeconomic stressors, including financial instability and limited access to healthcare, might exacerbate migraine severity and hinder effective management [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Given these findings, it is evident that more research is needed to explore the impact of socioeconomic factors on migraine, particularly among patients with higher educational levels who continue to experience CM. Such studies could provide deeper insights into the barriers to effective migraine management across different socioeconomic strata and help tailor interventions that address these unique challenges, especially in settings like ours where patients typically have better access to specialized care[

6,

35,

36].

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

While this study provides valuable insights, it is not without limitations. The sample size for some comorbidities was relatively small, which may have affected the statistical power to detect significant associations. Additionally, the lack of detailed information on treatment regimens and medication adherence could have influenced the results, particularly in understanding how the management of comorbid conditions affects migraine outcomes. Furthermore, the study did not explore crucial parameters such as medication usage, HbA1c levels, and glucose levels in patients with diabetes mellitus. Future research should focus on longitudinal studies to validate these findings and explore gene-environment interactions in a larger cohort. Such studies could also investigate lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise, which were beyond the scope of this study but could play a crucial role in the intricate relationship between genetics and migraine chronification.

4.4. Implications for Clinical Practice

Our study underscores the importance of considering familial health dynamics when assessing migraine risk. This approach could lead to more personalized migraine management strategies, potentially improving outcomes for patients with a high genetic predisposition to chronic migraine.

4.5. Concluding Remarks

In conclusion, our findings suggest that both genetic and environmental factors significantly contribute to migraine chronification. The highlighted role of familial hypercholesterolemia, particularly maternal, suggests new avenues for research into the genetic basis of migraine and its potential treatment targets. Understanding these relationships will be crucial for developing preventive strategies and therapeutic interventions tailored to individual risk profiles, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for migraine sufferers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Louter M, Fernandez-Morales J, De Vries B, et al. Candidate-gene association study searching for genetic factors involved in migraine chronification. Cephalalgia 2015;35(6):500–507. [CrossRef]

- on behalf of Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache, Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, et al. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J. Headache Pain 2020;21(1):137, s10194-020-01208–0.

- Safiri S, Pourfathi H, Eagan A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine in 204 countries and territories, 1990 to 2019. Pain 2022;163(2):e293–e309. [CrossRef]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018;38(1):1–211.

- Natoli J, Manack A, Dean B, et al. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: A systematic review. Cephalalgia 2010;30(5):599–609. [CrossRef]

- Buse DC, Manack AN, Fanning KM, et al. Chronic Migraine Prevalence, Disability, and Sociodemographic Factors: Results From the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2012;52(10):1456–1470. [CrossRef]

- Bigal ME, Serrano D, Buse D, et al. Acute Migraine Medications and Evolution From Episodic to Chronic Migraine: A Longitudinal Population-Based Study. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2008;48(8):1157–1168. [CrossRef]

- Bendtsen L. Central Sensitization in Tension-Type Headache—Possible Pathophysiological Mechanisms. Cephalalgia 2000;20(5):486–508. [CrossRef]

- Burstein R, Collins B, Jakubowski M. Defeating migraine pain with triptans: A race against the development of cutaneous allodynia. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55(1):19–26. [CrossRef]

- Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Manack AN, Lipton RB. Defining the differences between episodic migraine and chronic migraine. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16(1):86–92. [CrossRef]

- Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Excessive acute migraine medication use and migraine progression. Neurology 2008;71(22):1821–1828. [CrossRef]

- Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Clinical course in migraine: Conceptualizing migraine transformation. Neurology 2008;71(11):848–855.

- Manack A, Buse DC, Serrano D, et al. Rates, predictors, and consequences of remission from chronic migraine to episodic migraine. Neurology 2011;76(8):711–718. [CrossRef]

- Manack AN, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Chronic Migraine: Epidemiology and Disease Burden. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(1):70–78. [CrossRef]

- Scher AI, Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Comorbidity of migraine. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2005;18(3):305–310.

- Lipton RB, Manack Adams A, Buse DC, et al. A Comparison of the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study and American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study: Demographics and Headache-Related Disability. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2016;56(8):1280–1289. [CrossRef]

- Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine. Neurol. Clin. 2019;37(4):631–649.

- Ford JH, Jackson J, Milligan G, et al. A Real-World Analysis of Migraine: A Cross-Sectional Study of Disease Burden and Treatment Patterns. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2017;57(10):1532–1544. [CrossRef]

- Tekgol Uzuner G, Yalın OO, Uluduz D, et al. Migraine and cardiovascular risk factors: A clinic-based study. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2021;200:106375. [CrossRef]

- Yalın OÖ, Uluduz D, Özge A, et al. Phenotypic features of chronic migraine. J. Headache Pain 2016;17(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, et al. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2010;81(4):428–432. [CrossRef]

- Buse DC, Rains JC, Pavlovic JM, et al. Sleep Disorders Among People With Migraine: Results From the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2019;59(1):32–45. [CrossRef]

- Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Migraine Chronification. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2011;11(2):139–148.

- Adams AM, Serrano D, Buse DC, et al. The impact of chronic migraine: The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia 2015;35(7):563–578. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari A, Leone S, Vergoni AV, et al. Similarities and Differences Between Chronic Migraine and Episodic Migraine. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2007;47(1):65–72. [CrossRef]

- Wang S-J, Wang P-J, Fuh J-L, et al. Comparisons of disability, quality of life, and resource use between chronic and episodic migraineurs: A clinic-based study in Taiwan. Cephalalgia 2013;33(3):171–181. [CrossRef]

- Onan D, Younis S, Wellsgatnik WD, et al. Debate: differences and similarities between tension-type headache and migraine. J. Headache Pain 2023;24(1):92. [CrossRef]

- Lipton RB, Seng EK, Chu MK, et al. The Effect of Psychiatric Comorbidities on Headache-Related Disability in Migraine: Results From the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2020;60(8):1683–1696. [CrossRef]

- Blumenfeld A, Varon S, Wilcox T, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia 2011;31(3):301–315. [CrossRef]

- Cassidy EM, Tomkins E, Hardiman O, O’Keane V. Factors Associated With Burden of Primary Headache in a Specialty Clinic. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2003;43(6):638–644. [CrossRef]

- Juang K-D, Wang S-J, Fuh J-L, et al. Comorbidity of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in Chronic Daily Headache and Its Subtypes. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2000;40(10):818–823.

- Kim S-Y, Park S-P. The role of headache chronicity among predictors contributing to quality of life in patients with migraine: a hospital-based study. J. Headache Pain 2014;15(1):68. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y-C, Tang C-H, Ng K, Wang S-J. Comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine sufferers in a national database in Taiwan. J. Headache Pain 2012;13(4):311–319. [CrossRef]

- Breslau N, Lipton RB, Stewart WF, et al. Comorbidity of migraine and depression: Investigating potential etiology and prognosis. Neurology 2003;60(8):1308–1312.

- Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al. Prevalence and Burden of Migraine in the United States: Data From the American Migraine Study II. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2001;41(7):646–657. [CrossRef]

- Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Liberman J. Variation in migraine prevalence by race. Neurology 1996;47(1):52–59. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).