1. Introduction

Anion exchange membrane (AEM) fuel cells have gained significant attention due to their cost-effectiveness and high energy conversion efficiency [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. In AEMs, quaternary ammonium (QA) head groups covalently bound to the polymer backbone are susceptible to chemical degradation under alkaline conditions and at elevated temperatures [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Improving the chemical stability of these QA head groups is critical for enhancing the long-term performance of AEMs in fuel cell applications.

In our recent computational studies, we investigated how the chemical structure of QA head groups affects their stability under alkaline conditions. For example, in one of our works, we explored the degradation mechanisms of trimethylhexylammonium (TMHA) and benzyltrimethylammonium (BTMA) head groups, focusing on key degradation pathways such as nucleophilic substitution (

) and ylide formation (YF) [

13]. In another study, we examined the influence of hydration levels on the chemical stability and transport properties of quaternized chitosan (QCS) head groups in AEMs, revealing how water content affects degradation under alkaline conditions [

14]. These investigations highlight the importance of structural and environmental factors in determining the stability of QA head groups.

Building on this prior work, we now shift our focus from the chemical structure of QA head groups to the effect of the solution environment, specifically the impact of Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES). DES, which is a eutectic mixture of Lewis or Brønsted acids and bases, exhibits several favorable properties, including biodegradability, non-toxicity, and low vapor pressure [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Despite its potential to enhance the stability of chemical systems, the role of DES in stabilizing QA head groups in AEMs has not been thoroughly investigated.

In this work, we employed Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations and ab initio Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to study the chemical stability of tetramethylammonium (TMA) head groups, both with and without the presence of a choline chloride and ethylene glycol-based DES. The interactions between hydroxide () ions and TMA head groups were analyzed across various hydration levels (HLs) and temperatures. By incorporating DES molecules, we aimed to explore their role in modulating the degradation mechanisms of TMA head groups, providing insights into the development of more chemically robust AEM materials.

In the following sections, we present our computational approach, including the DFT and ab initio MD methods, followed by an in-depth analysis of the stability of TMA head groups under different hydration levels and temperatures. This study offers new insights into the suppression of degradation mechanisms through the addition of DES, contributing to advancements in AEM-based renewable energy technologies.

2. Model and Methods

2.1. System of Interest

In this study, we modeled a choline chloride and ethylene glycol-based DES, as shown in

Figure 1, at a 1:2 molar ratio. The DES was combined with QA head groups, hydroxide ions (

), and water molecules to simulate the environment relevant to Anion Exchange Membranes (AEMs). These components were used to assess the chemical stability of TMA head groups under various conditions. The TMA head group of the AEM segment was chosen as the model system, and its interactions with

ions were studied in both the presence and absence of DES. This computational model was used for DFT calculations and

ab initio MD simulations to evaluate how DES influences the degradation mechanisms of the head groups, with a particular focus on varying hydration levels and temperatures. The aim was to simulate the behavior of the AEM in DES-supported environments and provide insight into how these factors contribute to the chemical stability of the TMA head groups.

2.2. DFT Calculations

DFT calculations were employed to optimize the electronic ground state geometries and perform frequency calculations, yielding key thermodynamic parameters: reaction energy (

), Gibbs free energy change (

), activation energy (

), and activation Gibbs free energy (

). These calculations were crucial for understanding the stability of TMA head groups in AEMs and the degradation mechanisms triggered by interactions with hydroxide ions (

). The B3LYP functional, with the 6-311++g(2d,p) basis set, was used in conjunction with the polarizable continuum model (PCM) to simulate solvent effects [

22,

23]. The optimization of TMA head groups was carried out in the presence and absence of

ions, both with and without DES.

To model the nucleophilic substitution (

) and ylide formation (YF) degradation mechanisms, transition state structures were identified using the same level of theory, with DFT optimizations performed in implicit DMSO [

24,

25]. The hydration level was varied by explicitly adding water molecules to the system, and transition states were optimized to investigate the stability of the head groups under different hydration conditions. The calculated reaction and activation energies for both

and YF mechanisms were used to assess the stability of TMA head groups in the presence and absence of DES.

The chemical degradation mechanisms are represented by the following reactions: nucleophilic substitution (

) and ylide formation for both DES-supported and unsupported systems, as shown in Equations (

1)–(

6). The reaction energy (

) and activation energy (

) were calculated using Equations (

7) and (

8), while the Gibbs free energy changes (

and

) were calculated using Equations (

9) and (

10). Additionally, basis set superposition error (BSSE) was corrected using the counterpoise method to ensure accurate transition state energy evaluations.

2.3. ab initio Molecular Dynamics

The ab initio MD simulation setup involved placing one TMA head group and one negatively charged ion, along with 1 to 5 water molecules, at temperatures ranging from 298 K to 350 K, both in the absence and presence of DES. The DES used in this study was composed of choline chloride and ethylene glycol in a 1:2 molar ratio. These diverse configurations allowed us to investigate the influence of hydration levels and DES on the chemical stability of the TMA head group.

Each ab initio MD simulation began with an initial configuration consisting of the TMA head group, ion, and water molecules, placed in a simulation box with dimensions . Energy minimization was first performed under the NVE ensemble for 10 ps to optimize the initial configuration. Following this, the simulations were conducted for 50 ps using the NVT ensemble at reference temperatures of 298 K, 320 K, and 350 K.

Atomic forces were computed using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with the BLYP functional. The Kohn-Sham orbitals were represented using a hybrid Gaussian plane-wave (GPW) approach, which combines Gaussian-type orbitals with plane-wave basis sets to efficiently construct the Kohn-Sham matrix while maintaining accuracy. Goedecker-Teter-Hutter (GTH) pseudopotentials were used to represent core electrons, with adjustments made for the density functionals employed. To optimize computational efficiency, matrix elements smaller than were disregarded, and a plane-wave cutoff of 400 Ry was applied. Dispersion forces were included using the Grimme D3 approximation, with a convergence criterion for the self-consistent field (SCF) set to .

Temperature control was managed using the Generalized Langevin Equation (GLE) method [

26], and periodic boundary conditions were applied in all directions [

27]. All simulations were performed using the CP2K software suite (version 9.1) [

28], and bond distances were analyzed at various hydration levels and temperatures using Visualization Molecular Dynamics (VMD) software (version 1.9.1) [

29].

3. Results and Discussion

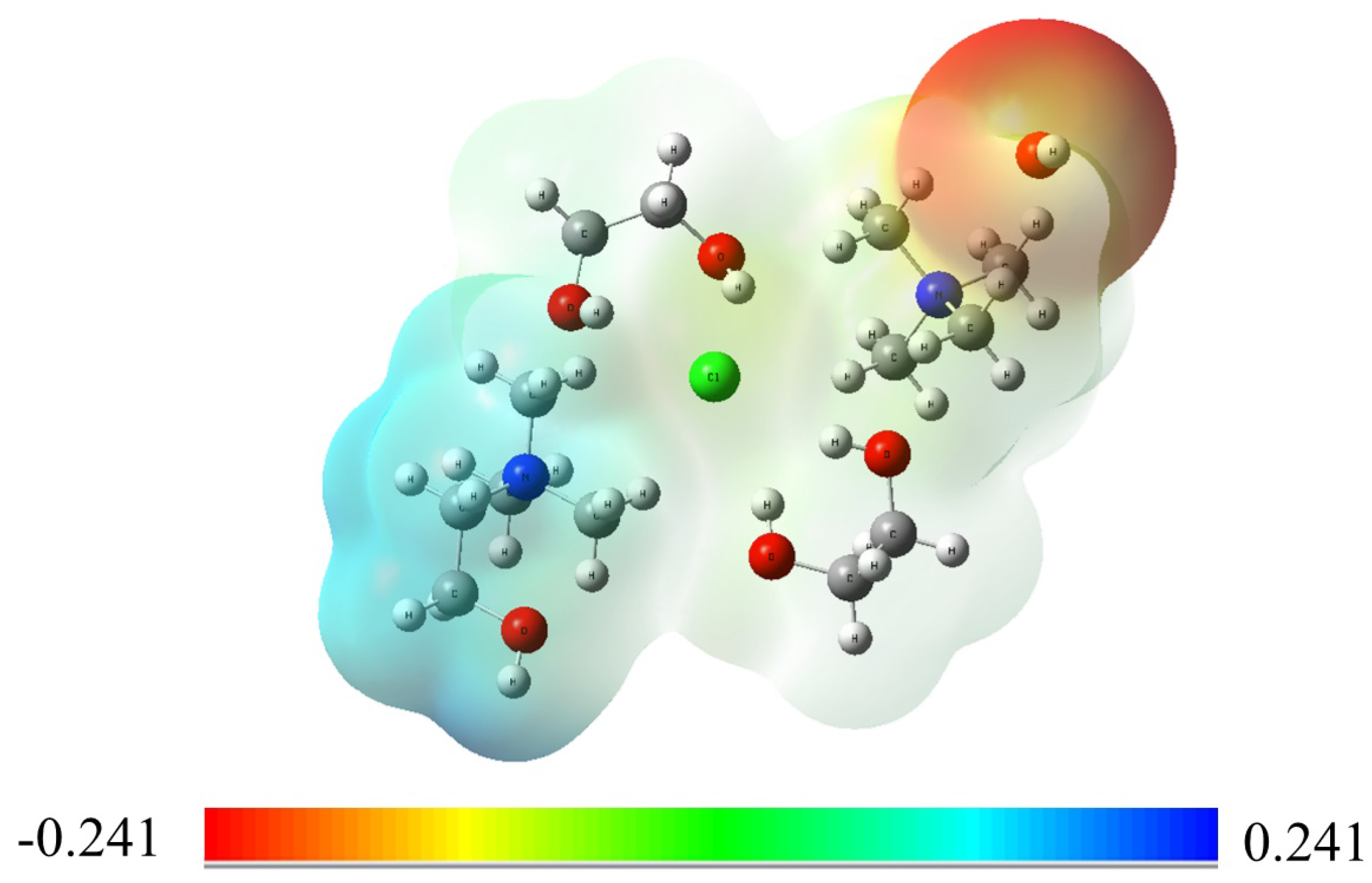

3.1. Electrostatic Potential Map

Molecular electrostatic potential (ESP) maps were employed to visualize the interaction between

ions and the TMA head group in the presence of DES molecules, using the B3LYP DFT method. Initially,

ions were positioned near the nitrogen atom of the TMA head group to neutralize its positive charge. The resulting charge distribution of the TMA head group, with the presence of DES, is displayed in

Figure 2. The ESP map highlights the predominant interaction between

ions and the nitrogen atom of the TMA head group, stabilizing the positive charge. This interaction is a critical factor in enhancing the chemical stability of the TMA head group in the DES environment.

Further analysis of the ESP map indicates that ions tend to occupy the space formed by the three methyl groups surrounding the nitrogen atom. This arrangement may contribute to a stabilizing effect of DES, as it could reduce the reactivity of ions toward the head group, potentially lowering the likelihood of nucleophilic attacks. In practical AEM applications, where the TMA head group is typically tethered to the polymer backbone, DES may offer a means to mitigate degradation under alkaline conditions. While these ESP maps offer useful insights into charge distribution and possible interaction sites, they represent a simplified view of the complex interactions at play. Further research will be required to fully understand the stabilizing effects of DES and its practical impact on AEM stability.

Under operational conditions in AEM fuel cells, increasing current density accelerates water consumption at the cathode, which can lead to a drier environment. In such conditions, ions that are not solvated by water molecules exhibit higher nucleophilicity, potentially accelerating the degradation of TMA head groups. Conversely, when ions are adequately solvated, their nucleophilicity is reduced, which underscores the importance of water content in influencing AEM stability. As water content decreases, the concentration of ions increases, potentially raising the risk of nucleophilic attacks on QA head groups. Understanding this degradation mechanism is important for evaluating the long-term performance of AEMs in fuel cell systems. Future studies that explore the effects of hydration levels and temperature will be valuable for refining our understanding of these interactions and their implications for AEM performance.

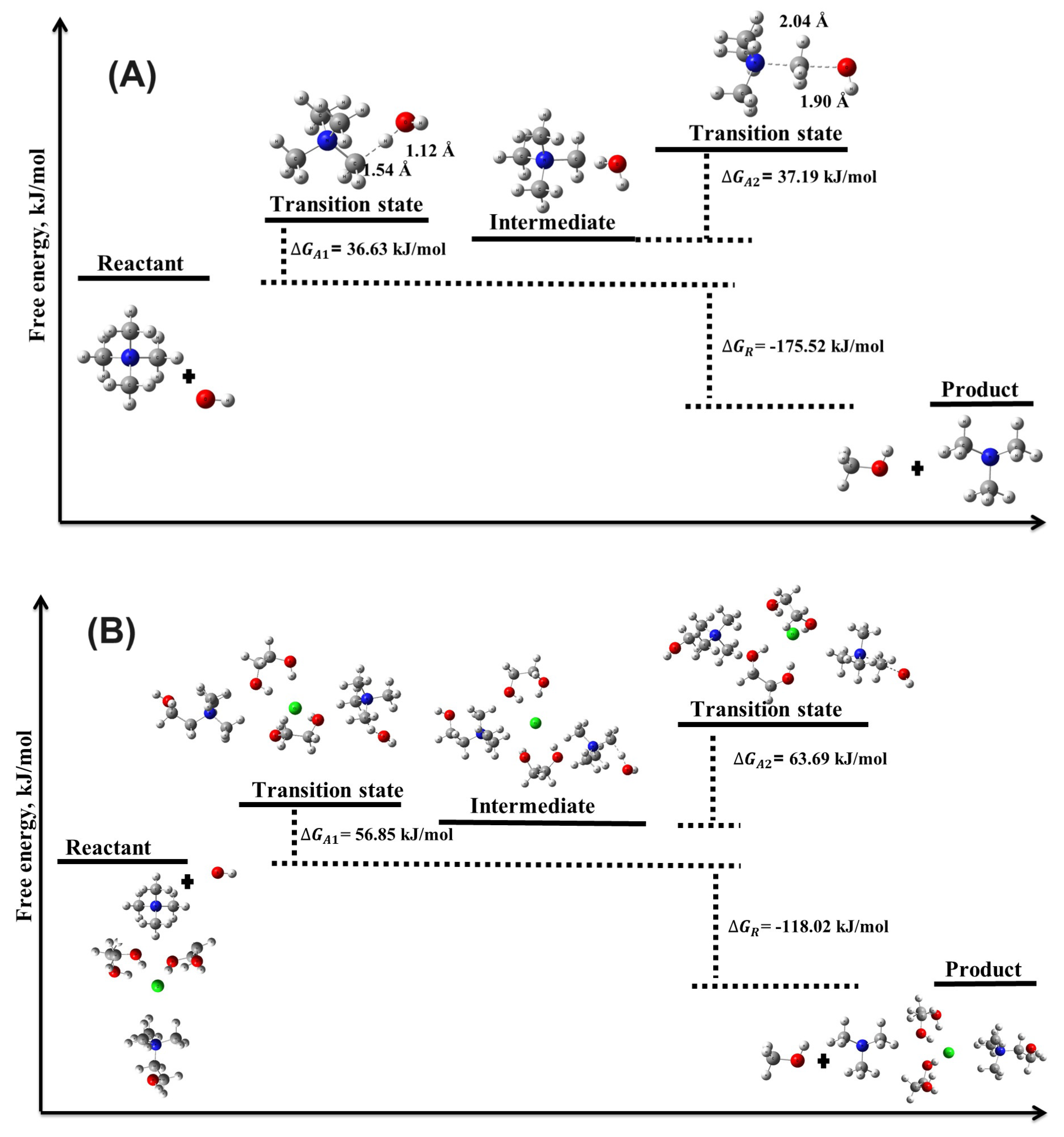

3.2. Activation and Reaction Energies

DFT calculations using the B3LYP hybrid functional were employed to investigate the chemical degradation reactions between

ions and the TMA head group, focusing on the evaluation of reaction energies (

,

) and activation energies (

,

) for these reactions in both the absence and presence of DES. The results (

Table 1,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) provide crucial insights into the degradation mechanisms of TMA-based AEMs in alkaline environments, particularly highlighting the stabilizing role of DES. Compared to other theoretical studies, such as those by Chempath

et al. [

30,

31], the calculated values of

and

in the absence of DES align with previously reported data for

and YF mechanisms. However, the role of DES in modifying these degradation mechanisms, specifically in terms of

,

,

, and

, has not been extensively explored in the literature, marking this study’s contribution to understanding the role of DES in these reactions.

3.2.1. Ylide Formation Mechanism

The ylide formation degradation mechanism was analyzed in two distinct steps. In the first step, the activation energy barrier was found to be moderate, with of 18.02 kJ/mol and of 36.63 kJ/mol. The corresponding reaction energies ( and ) were 16.95 kJ/mol and 26.81 kJ/mol, respectively, suggesting that while the reaction is thermodynamically favorable, it is less so compared to the nucleophilic substitution () mechanism.

In the second step of the YF mechanism, we observed a significant decrease in both and , with values of -135.21 kJ/mol and -175.52 kJ/mol, respectively. This indicates a highly exergonic reaction, favoring the spontaneous degradation of the TMA head group in the absence of DES. The activation energy barrier for this step was still relatively low, with kJ/mol and kJ/mol, further supporting the spontaneous nature of the YF mechanism.

3.2.2. Nucleophilic Substitution Mechanism

The

mechanism displayed lower activation barriers than the YF mechanism, indicating it is more likely to occur under standard alkaline conditions. For the reaction without DES, the activation energy (

) was significantly lower than in the YF mechanism, with the reaction remaining spontaneous and exergonic. These findings align with previous research by Chempath et al. [

30,

31], which identified the

and YF mechanisms as key degradation pathways for TMA in the presence of

ions. The low activation barriers in both mechanisms suggest that these pathways are prominent under alkaline conditions in the absence of DES.

3.2.3. Impact of DES on Activation and Reaction Energies

In the presence of DES, a notable increase in the activation energy barriers was observed for both the YF and mechanisms. For the mechanism, increased to 54.62 kJ/mol, with a substantial rise in to 100.43 kJ/mol. Despite these higher energy barriers, the reaction remained exergonic and spontaneous, as reflected by kJ/mol and kJ/mol. This suggests that the presence of DES introduces a kinetic barrier that slows the degradation process, thereby improving the chemical stability of the TMA head group.

The effect of DES on the YF mechanism was similarly significant. In the first step of the YF mechanism, increased to 27.64 kJ/mol and to 56.85 kJ/mol, indicating that the presence of DES raises the energy barrier for this degradation pathway. Reaction energies also shifted towards more endergonic values, with kJ/mol and kJ/mol, suggesting that the DES environment stabilizes the system. In the second step of the YF mechanism, the presence of DES further increased both activation and reaction energies, with kJ/mol and kJ/mol. Although still exergonic, with kJ/mol and kJ/mol, the increased energy barriers highlight DES’s role in slowing the degradation process.

The increase in activation energy barriers in the presence of DES underscores its potential as a stabilizing agent for TMA head groups in AEMs. By altering the local electrostatic potential, DES raises the energy barriers for both and YF degradation pathways, effectively mitigating the degradation process. This enhanced chemical stability is crucial for the long-term performance of AEMs in alkaline environments.

The higher energy barriers observed in this study suggest that incorporating DES into AEM systems could significantly extend the operational lifetime of these membranes under alkaline conditions. To further explore the stability-enhancing role of DES, we conducted ab initio MD simulations to investigate the influence of hydration levels and temperature on degradation mechanisms. Understanding the impact of these conditions is essential for optimizing AEM performance in real-world operating environments, where moisture content and temperature fluctuations play a critical role in the chemical stability of QA head groups.

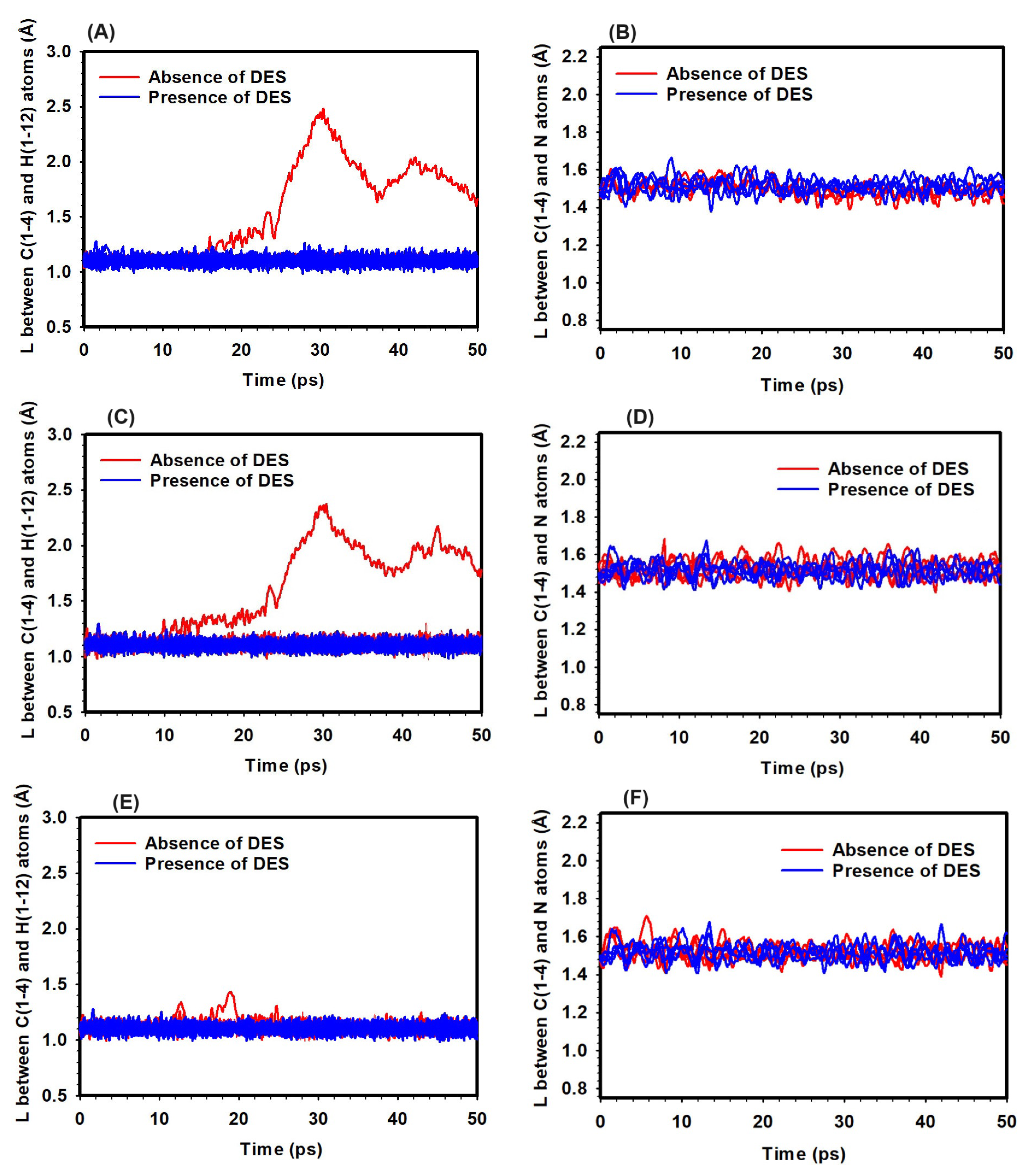

3.3. Effect of Hydration Level

The influence of hydration level on the chemical degradation mechanisms of the TMA head group in the presence of hydroxide ions was investigated. Bond-breaking events, particularly the C/N and H/C bond distances, were analyzed as indicators of potential nucleophilic substitution (

) and ylide formation reactions, leading to the production of methanol and trimethylammonium. The analysis covered three hydration levels: HL 1, HL 3 (representing typical operating conditions), and HL 5, both in the absence and presence of DES (

Figure 5).

At HL 1 and a temperature of 298 K, the C/N bond distance within the TMA head group remained stable at approximately 1.50 Å, indicating minimal bond-breaking events and low

reaction potential, regardless of DES presence (

Figure 5). However, the H/C bond distance increased significantly from 1.10 Å to 2.12 Å in the absence of DES, suggesting potential YF activation. In contrast, the presence of DES maintained the H/C bond distance at around 1.10 Å, effectively suppressing the YF mechanism (

Figure 5).

At HL 3 and 298 K, the C/N bond distance also remained stable, further supporting the low likelihood of

reactions under these conditions (

Figure 5). The H/C bond distance, however, increased to 2.61 Å without DES, indicating a higher propensity for YF reactions. In the presence of DES, the H/C bond distance was stabilized at around 1.10 Å, inhibiting the YF mechanism (

Figure 5).

At HL 5 and 298 K, the C/N bond distances remained stable, showing a low likelihood of

reactions at this hydration level (

Figure 5). The H/C bond distance remained consistent around 1.10 Å, regardless of DES presence, indicating minimal YF mechanism activity at this hydration level and temperature (

Figure 5).

The investigation provided insights into bond-breaking events within the TMA head group. Across all hydration levels at 298 K, minimal bond-breaking events were observed, indicating a low likelihood of reactions. The YF mechanism, influenced by both hydration levels and the presence of DES, showed greater activation potential at lower hydration levels. However, DES effectively suppressed the YF mechanism by stabilizing the H/C bond distance. At higher hydration levels, the YF mechanism remained subdued regardless of DES, emphasizing the importance of hydration in controlling degradation pathways. These findings highlight the interplay between hydration and degradation mechanisms.

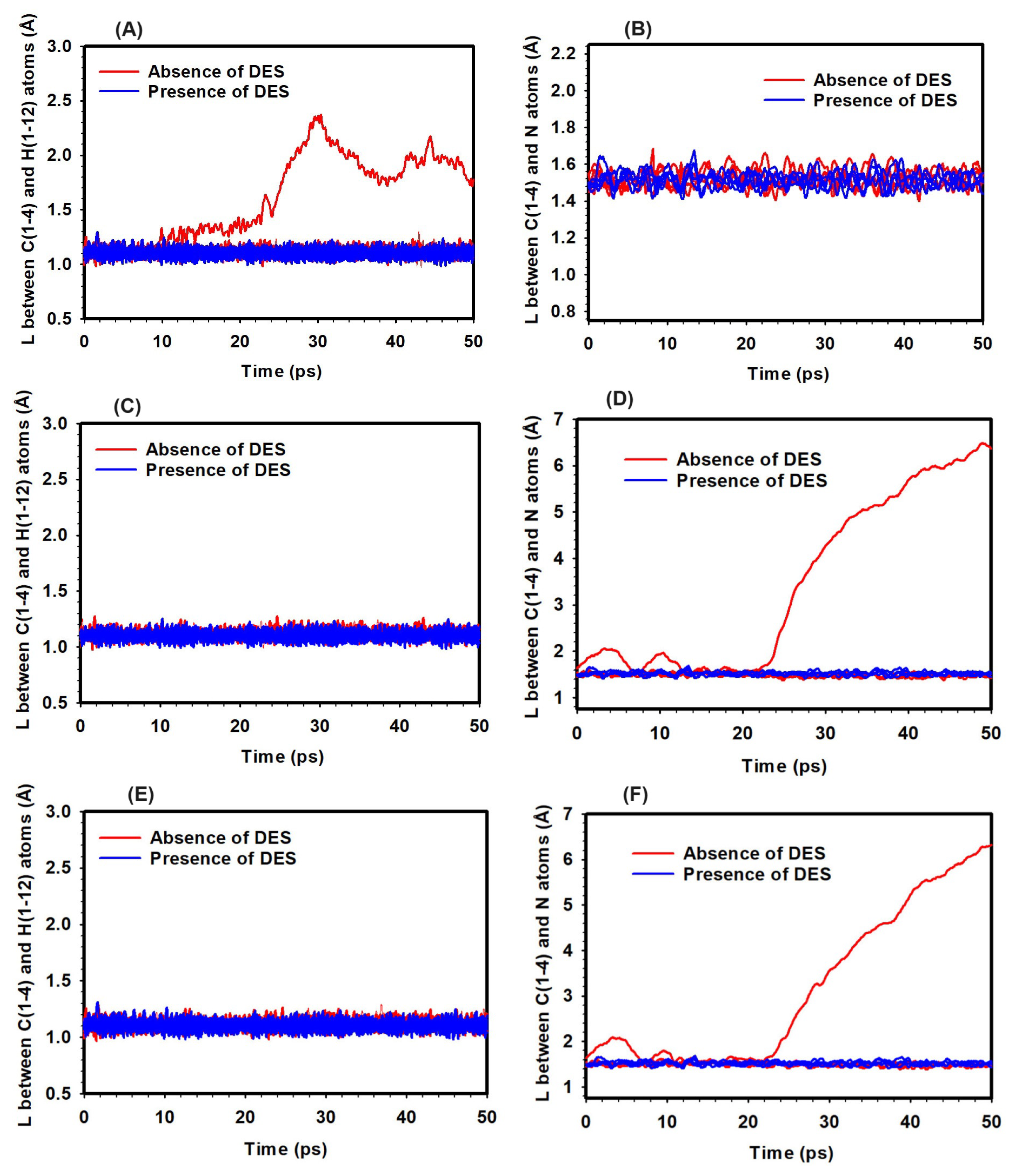

3.4. Effect of Temperature

The effect of temperature on the bond distances within the TMA head group in the presence of hydroxide ions was examined, with an emphasis on potential

and ylide formation (YF) reactions. The study was carried out at three temperatures: 298 K, 320 K, and 350 K, both in the absence and presence of Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES). The analysis tracked changes in the C/N and H/C bond distances (

Figure 6).

At 298 K and hydration level (HL) 3, the C/N bond distance remained at approximately 1.5 Å in both the presence and absence of DES, indicating that no significant bond-breaking events were observed that might suggest

reactions (

Figure 6). In contrast, the H/C bond distance increased from 1.20 Å to 2.61 Å in the absence of DES, potentially indicating activation of the YF mechanism. With DES present, the H/C bond distance remained around 1.10 Å, suggesting that DES may have had a stabilizing effect (

Figure 6).

At 320 K and HL 3, the C/N bond distance increased to 6.3 Å in the absence of DES, suggesting the occurrence of bond-breaking events and the potential for

reactions (

Figure 6). In the presence of DES, the C/N bond distance remained stable at around 1.55 Å, with no significant bond-breaking observed. The H/C bond distance showed little variation, staying close to 1.10 Å in both cases, suggesting that YF activation was limited at this temperature (

Figure 6).

At 350 K and HL 3, the C/N bond distance increased further to 6.56 Å without DES, indicating the possibility of bond-breaking events and

reactions (

Figure 6). With DES present, the C/N bond distance stayed near 1.58 Å, and no significant bond-breaking was observed. Similar to previous results, the H/C bond distance remained consistent around 1.10 Å, regardless of DES, indicating minimal YF mechanism involvement at this temperature (

Figure 6).

These observations suggest that temperature affects the likelihood of bond-breaking events in the TMA head group. The presence of DES appears to reduce the occurrence of these events across all temperatures studied, particularly in relation to and YF reactions. While the YF mechanism may have been more active at lower temperatures, higher temperatures seemed to promote reactions. These findings offer insight into the behavior of the TMA head group under varying thermal conditions, with the influence of DES observed to be a potential stabilizing factor.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we explored the chemical stability of TMA head groups, both with and without the presence of a choline chloride and ethylene glycol-based DES additives using DFT calculations and ab initio MD simulations. The investigation focused on key degradation mechanisms, such as nucleophilic substitution () and ylide formation, and the impact of DES addition on these mechanisms across different hydration levels and temperatures.

Our results indicate that DES effectively enhances the chemical stability of TMA head groups by consistently increasing the activation energy barriers for both and YF mechanisms. In the absence of DES, ylide formation was observed to dominate at lower hydration levels, while nucleophilic substitution became more prominent at elevated temperatures. However, in the presence of DES, both degradation mechanisms were significantly suppressed across all tested conditions, suggesting that DES acts as a stabilizing agent for the TMA head groups.

The ESP maps demonstrated that DES alters the interaction between hydroxide ions and the TMA head group, reducing the reactivity of hydroxide ions and thereby enhancing the chemical stability of the TMA groups. Additionally, DFT calculations showed that DES raised both reaction and activation energy barriers, further supporting the conclusion that DES plays a critical role in mitigating degradation.

Our ab initio MD simulations revealed that hydration levels strongly influence the stability of TMA head groups. Ylide formation was more likely at lower hydration levels in the absence of DES, while nucleophilic substitution became more probable at higher temperatures. The presence of DES, however, stabilized the TMA head groups under both conditions, reducing the likelihood of degradation.

In conclusion, the incorporation of DES into AEM systems offers the potential for improving the chemical stability of TMA head groups, particularly under alkaline conditions. Future work should focus on the experimental validation of these findings and the optimization of DES formulations for practical applications in AEMs, with the goal of enhancing membrane durability and performance in fuel cell technologies.

Author Contributions

Mirat Karibayev: Computational Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft; Bauyrzhan Myrzakhmetov: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing; Yanwei Wang: Supervision, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing; Almagul Mentbayeva: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing

Funding

This work was supported by the research grant AP14869880 "Deep eutectic solvent supported polymer-based high performance anion exchange membrane for alkaline fuel cells" project from MES RK.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials are available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are also grateful to Nazarbayev University Research Computing for providing computational resources for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AEM |

Anion Exchange Membrane |

| AEMFCs |

Anion Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells |

| BSSE |

Basis Set Superposition Error |

| DES |

Deep Eutectic Solvent |

| DFT |

Density Functional Theory |

|

Reaction Energy |

|

Activation Energy |

|

Reaction Free Energy |

|

Activation Free Energy |

| HL |

Hydration Level |

| MD |

Molecular Dynamics |

|

Hydroxide Ion |

| QA |

Quaternary Ammonium |

| YF |

Ylide Formation |

|

Nucleophilic Substitution |

References

- Hossen, M.M.; Hasan, M.S.; Sardar, M.R.I.; bin Haider, J.; Tammeveski, K.; Atanassov, P.; others. State-of-the-art and developmental trends in platinum group metal-free cathode catalyst for anion exchange membrane fuel cell (AEMFC). Appl. Catal. B . Environ. 2022, 121733. [CrossRef]

- Dicks, A.L. Molten carbonate fuel cells. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2004, 8, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormerod, R.M. Solid oxide fuel cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2003, 32, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Zhang, X.; Sun, H.; Wang, S.; Sun, G. Recent advances in multi-scale design and construction of materials for direct methanol fuel cells. Nano Energy 2019, 65, 104048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Diaz, D.F.R.; Chen, K.S.; Wang, Z.; Adroher, X.C. Materials, technological status, and fundamentals of PEM fuel cells–a review. Mater. today 2020, 32, 178–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrin, P.; Brandon, N.P. Progress and outlook for solid oxide fuel cells for transportation applications. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammes, N.; Bove, R.; Stahl, K. Phosphoric acid fuel cells: Fundamentals and applications. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2004, 8, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Jin, J.; Yang, S.; Li, G. A review of the microporous layer in proton exchange membrane fuel cells: Materials and structural designs based on water transport mechanism. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2022, 156, 111998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, S.; Shin, S.H.; Kim, Y.; Moon, S.H. A review on recent developments of anion exchange membranes for fuel cells and redox flow batteries. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 37206–37230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merle, G.; Wessling, M.; Nijmeijer, K. Anion exchange membranes for alkaline fuel cells: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 377, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, D.R. Review of cell performance in anion exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2018, 375, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varcoe, J.R.; Atanassov, P.; Dekel, D.R.; Herring, A.M.; Hickner, M.A.; Kohl, P.A.; Kucernak, A.R.; Mustain, W.E.; Nijmeijer, K.; Scott, K.; Xu, T.; Zhuang, L. Anion-exchange membranes in electrochemical energy systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3135–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karibayev, M.; Myrzakhmetov, B.; Kalybekkyzy, S.; Wang, Y.; Mentbayeva, A. Binding and degradation reaction of hydroxide ions with several quaternary ammonium head groups of anion exchange membranes investigated by the DFT method. Molecules 2022, 27, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karibayev, M.; Myrzakhmetov, B.; Bekeshov, D.; Wang, Y.; Mentbayeva, A. Atomistic Modeling of Quaternized Chitosan Head Groups: Insights into Chemical Stability and Ion Transport for Anion Exchange Membrane Applications. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Vigier, K.D.O.; Royer, S.; Jérôme, F. Deep eutectic solvents: syntheses, properties and applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2012, 41, 7108–7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) and their applications. Chemical Reviews 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, G.; Aparicio, S.; Ullah, R.; Atilhan, M. Deep eutectic solvents: physicochemical properties and gas separation applications. Energy & Fuels 2015, 29, 2616–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Friesen, J.B.; McAlpine, J.B.; Lankin, D.C.; Chen, S.N.; Pauli, G.F. Natural deep eutectic solvents: properties, applications, and perspectives. Journal of natural products 2018, 81, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zheng, G.W.; Zong, M.H.; Li, N.; Lou, W.Y. Recent progress on deep eutectic solvents in biocatalysis. Bioresources and bioprocessing 2017, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z. Natural deep eutectic solvents and their applications in biotechnology. Application of ionic liquids in biotechnology 2019, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda, A.; Matias, A.A.; Paiva, A.; Duarte, A.R.C. Polymer science and engineering using deep eutectic solvents. Polymers 2019, 11, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, P.J.; Devlin, F.J.; Chabalowski, C.F.; Frisch, M.J. Ab initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 11623–11627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennucci, B. Polarizable continuum model. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P.M.; Johnson, B.G.; Pople, J.A.; Frisch, M.J. The performance of the Becke—Lee—Yang—Parr (B—LYP) density functional theory with various basis sets. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1992, 197, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, E.; Jorge, F. Accurate universal Gaussian basis set for all atoms of the periodic table. Chem. Phys. 1998, 108, 5225–5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drużbicki, K.; Krzystyniak, M.; Hollas, D.; Kapil, V.; Slavíček, P.; Romanelli, G.; Fernandez-Alonso, F. Hydrogen dynamics in solid formic acid: insights from simulations with quantum colored-noise thermostats. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, 2018, Vol. 1055, p. 012003. [CrossRef]

- Ewald, P.P. Die Berechnung optischer und elektrostatischer Gitterpotentiale. Annalen der physik 1921, 369, 253–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, J.; Iannuzzi, M.; Schiffmann, F.; VandeVondele, J. cp2k: atomistic simulations of condensed matter systems. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Molecular Science 2014, 4, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD – Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chempath, S.; Einsla, B.R.; Pratt, L.R.; Macomber, C.S.; Boncella, J.M.; Rau, J.A.; Pivovar, B.S. Mechanism of tetraalkylammonium headgroup degradation in alkaline fuel cell membranes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2008, 112, 3179–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chempath, S.; Boncella, J.M.; Pratt, L.R.; Henson, N.; Pivovar, B.S. Density functional theory study of degradation of tetraalkylammonium hydroxides. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2010, 114, 11977–11983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of the key components in the study, including choline chloride–ethylene glycol-based Deep Eutectic Solvent and TMA head group.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of the key components in the study, including choline chloride–ethylene glycol-based Deep Eutectic Solvent and TMA head group.

Figure 2.

Molecular ESP map of the TMA head group in the presence of choline chloride and ethylene glycol at a 1:2 molar ratio, along with a hydroxide ion (). The map illustrates the charge distribution and interaction sites, showing the stabilizing effect of DES on the TMA head group by neutralizing its positive charge and reducing the reactivity of ions.

Figure 2.

Molecular ESP map of the TMA head group in the presence of choline chloride and ethylene glycol at a 1:2 molar ratio, along with a hydroxide ion (). The map illustrates the charge distribution and interaction sites, showing the stabilizing effect of DES on the TMA head group by neutralizing its positive charge and reducing the reactivity of ions.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the transition state structures and corresponding free energy barriers for the mechanism of the TMA head group in the (A) absence and (B) presence of DES.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the transition state structures and corresponding free energy barriers for the mechanism of the TMA head group in the (A) absence and (B) presence of DES.

Figure 4.

Illustration of the transition state structures and corresponding free energy barriers for the ylide formation mechanism of the TMA head group in the (A) absence and (B) presence of DES.

Figure 4.

Illustration of the transition state structures and corresponding free energy barriers for the ylide formation mechanism of the TMA head group in the (A) absence and (B) presence of DES.

Figure 5.

Bond distances in the TMA head group in the absence and presence of DES at hydration levels of 1 (A, B), 3 (C, D), and 5 (E, F). Left panels (A), (C), and (E) show the bond distances between the H and C atoms, while right panels (B), (D), and (F) depict the bond distances between the C and N atoms.

Figure 5.

Bond distances in the TMA head group in the absence and presence of DES at hydration levels of 1 (A, B), 3 (C, D), and 5 (E, F). Left panels (A), (C), and (E) show the bond distances between the H and C atoms, while right panels (B), (D), and (F) depict the bond distances between the C and N atoms.

Figure 6.

Bond distances in the TMA head group in the absence and presence of DES at HL 3 and varying temperatures: 298 K (A, B), 320 K (C, D), and 350 K (E, F). Left panels (A), (C), and (E) show the bond distances between the H and C atoms, while right panels (B), (D), and (F) depict the bond distances between the C and N atoms.

Figure 6.

Bond distances in the TMA head group in the absence and presence of DES at HL 3 and varying temperatures: 298 K (A, B), 320 K (C, D), and 350 K (E, F). Left panels (A), (C), and (E) show the bond distances between the H and C atoms, while right panels (B), (D), and (F) depict the bond distances between the C and N atoms.

Table 1.

, , , and values for the degradation reactions of TMA head group in the absence and presence of DES. All values are in kJ/mol.

Table 1.

, , , and values for the degradation reactions of TMA head group in the absence and presence of DES. All values are in kJ/mol.

| |

|

YF (step 1) |

YF (step 2) |

| |

Without DES |

With DES |

Without DES |

With DES |

Without DES |

With DES |

|

-105.47 |

-68.98 |

16.95 |

27.66 |

-135.21 |

-96.64 |

|

48.18 |

54.62 |

18.02 |

27.64 |

31.02 |

39.97 |

|

-148.70 |

-81.29 |

26.81 |

36.73 |

-175.52 |

-118.02 |

|

64.00 |

100.43 |

36.63 |

56.85 |

37.19 |

63.69 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).