Method

Our static analyzer checks the function parameters of all WBP loading points. Analyze the value range of the variable based on the data dependency relationship of the actual parameter variable [

1]. It approximates as closely as possible all the possible literal values that the variable at the loading point may receive. To achieve this goal, we constructed a two-stage approach: the first stage collects all the variable sets that the variable depends on (if the variable is assigned values by other variables), and the second stage collects the literal assignments of all variables in the variable set.

Step 1: The symbols tracked by algorithms are divided into three categories: ordinary variables, array types, and record types. The algorithm starts from the analysis of using symbol and constructs a data flow graph for all three types of symbols that symbol depends on.

Suppose there is

symbol a in the data flow graph

. The rule for adding elements to

for array types is:

The rule for adding elements to

for record types is:

Both and are considered elements in .

For any symbol, there are rules:

The algorithm first adds the symbol to , and then analyzes the code upwards, applying three types of rules until can no longer be expanded.

For function calls, there are rules:

This rule states that if symbol is modified in function , and the modification depends on symbol in the function. Then construct a separate data flow graph for . Then add it to the original data flow graph that the edge from symbol to the other arguments passed to . This edge contains call point information, that is, the corresponding relationship between these arguments and formal parameters of .

There are rules for modifying symbol

by return value:

This rule adds it to the original data flow graph that the edge from symbol to all arguments passed to (assuming ).

Afterwards, the algorithm replaces the

and

edges in

with the data flow graph

of

:

This rule replaces

(several formal parameter nodes) in

with several arguments nodes (i.e.

in

) recorded in edge

. This allows it to connect with the existing nodes in

.

In this rule, since the symbol is modified by the return value of , it is also necessary to replace the symbol node returned in with the symbol . This allows it to connect with the existing nodes in .

Step 2: The algorithm collects all the statements in

that have been assigned literal values:

Among them, is the starting point for analysis, represents that is connected to . is the set of possible literal values that the analyzed symbol may receive.

Example

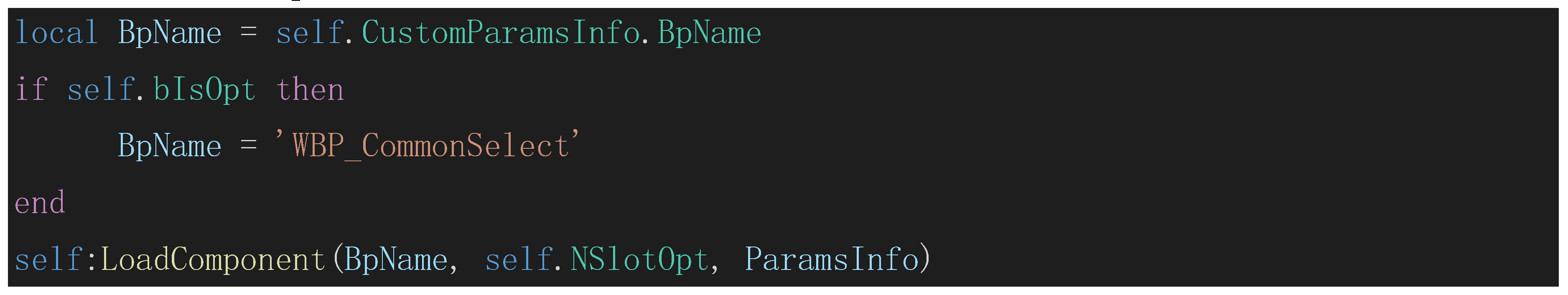

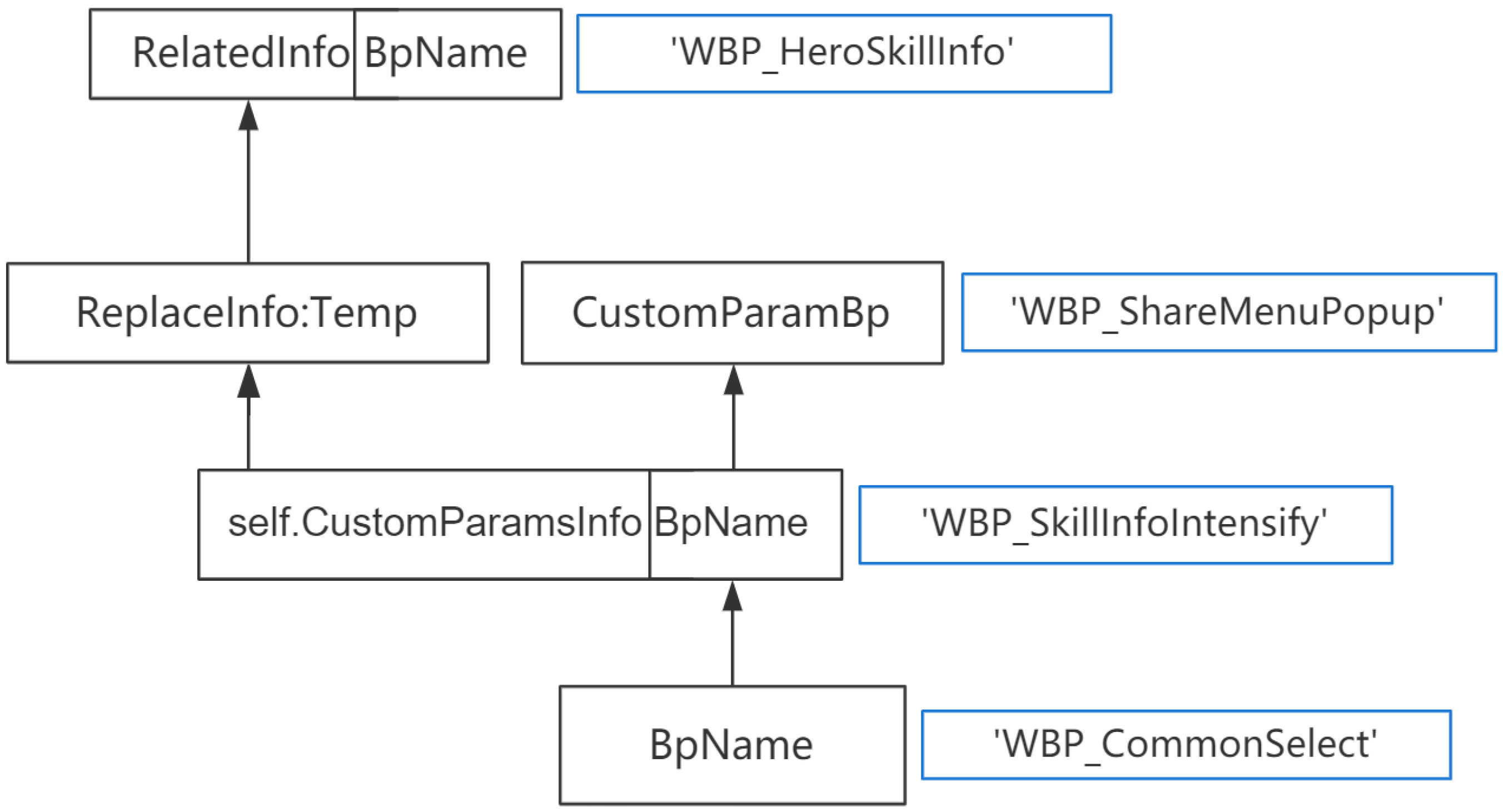

As a code chip:

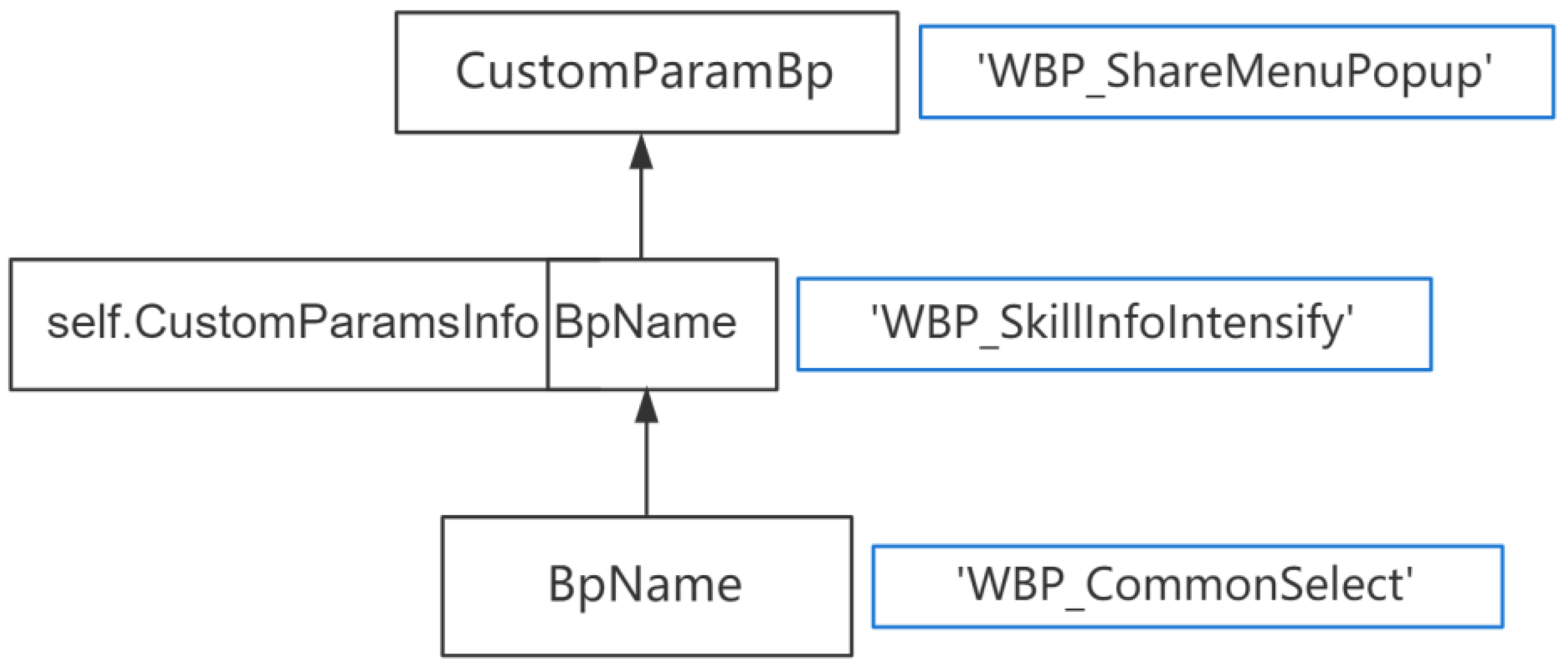

The argument

BpName of the loading point

LoadComponent is the symbol to be analyzed. Looking back, it can be found that

BpName has two modification points, both of which are assignment statements. Therefore, the data flow graph

becomes:

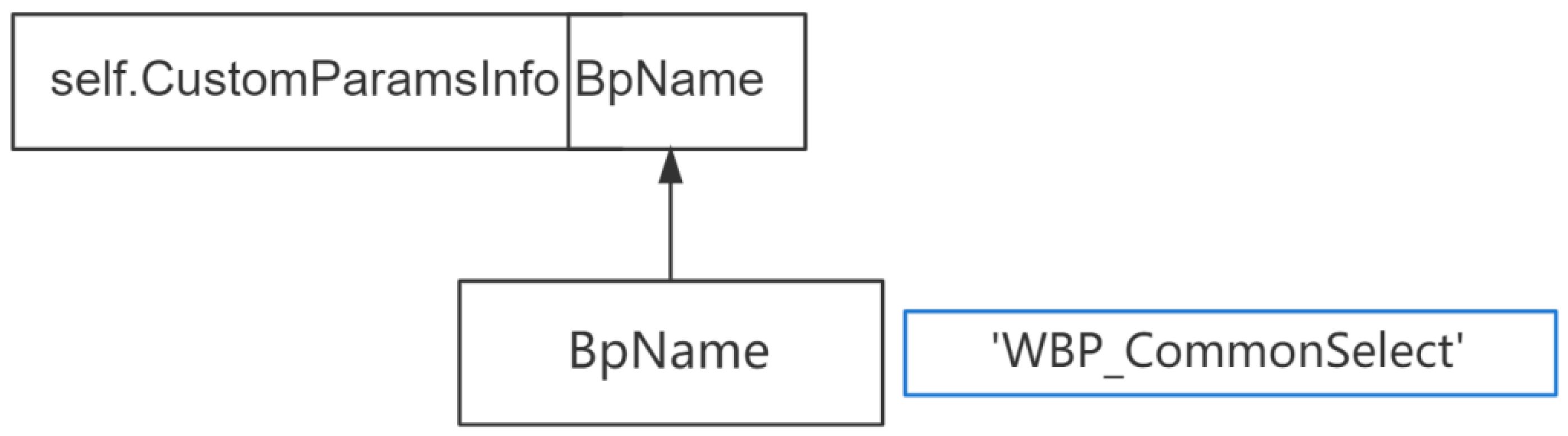

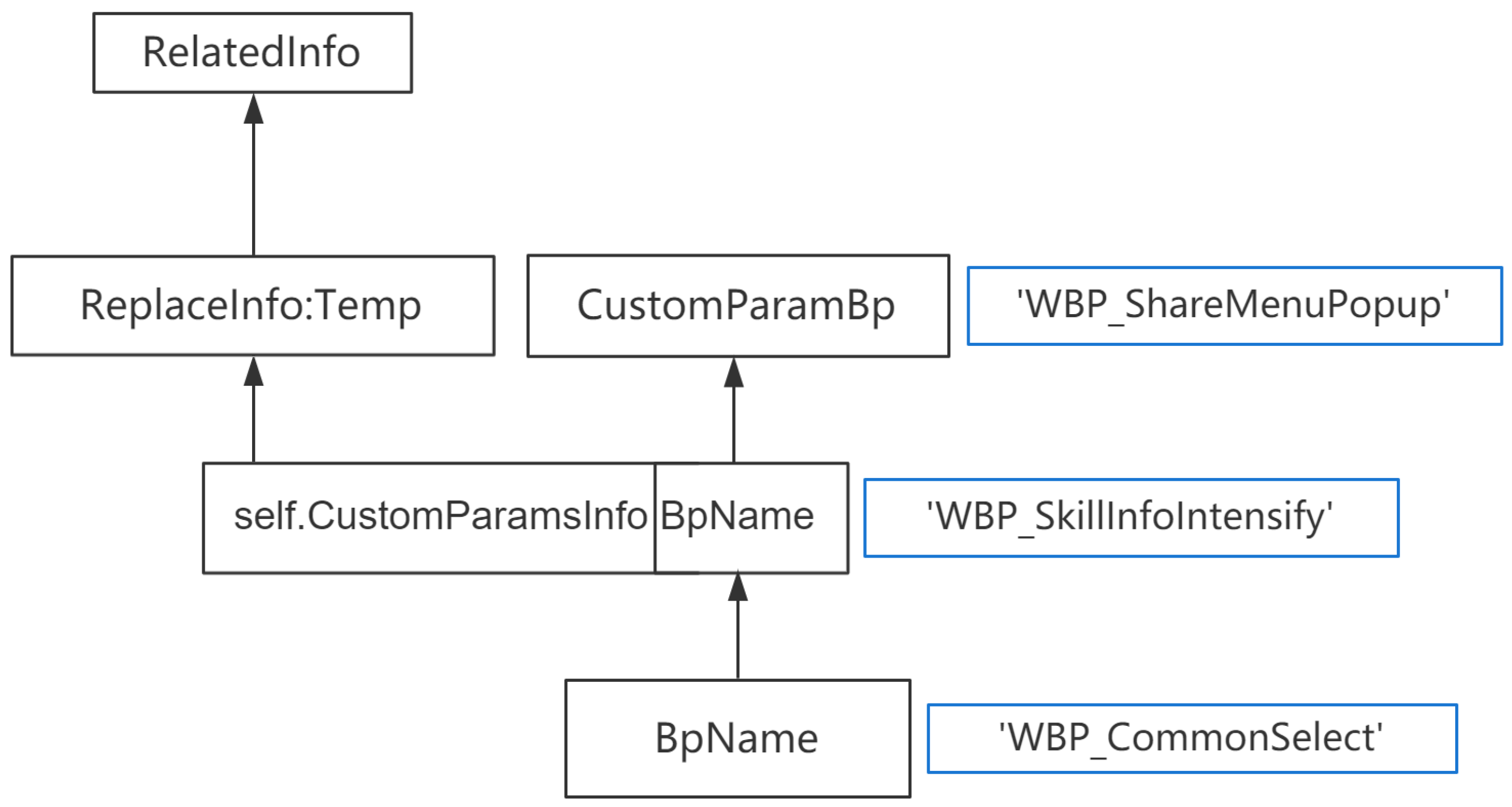

After scanning all the modified points of

BpName, scan the newly added symbols in the data flow graph. If there is code:

Then the data flow graph

becomes:

If all symbols have been scanned and no new symbols have been added, then the range of literal values for all symbols will be merged. The possible values for BpName will be WBP_CommonSelect, WBP_ShareMenuPopup, WBP_SkillInfoIntensify.

From this example, it can be seen that due to the trade-off between the speed and accuracy of the analysis algorithm, we must choose appropriate control flow and data flow abstractions to avoid difficult to handle calculations. To achieve this goal, our algorithm over-approximates the exact set of values that its parameters may have. Therefore, only flow sensitive analysis methods [

2] are used. In this example, we do not calculate whether

self.bIsOpt cannot be

true (if it is always

false, we can exclude one value), but instead adopt all possible paths and contexts that can expand the set of values.

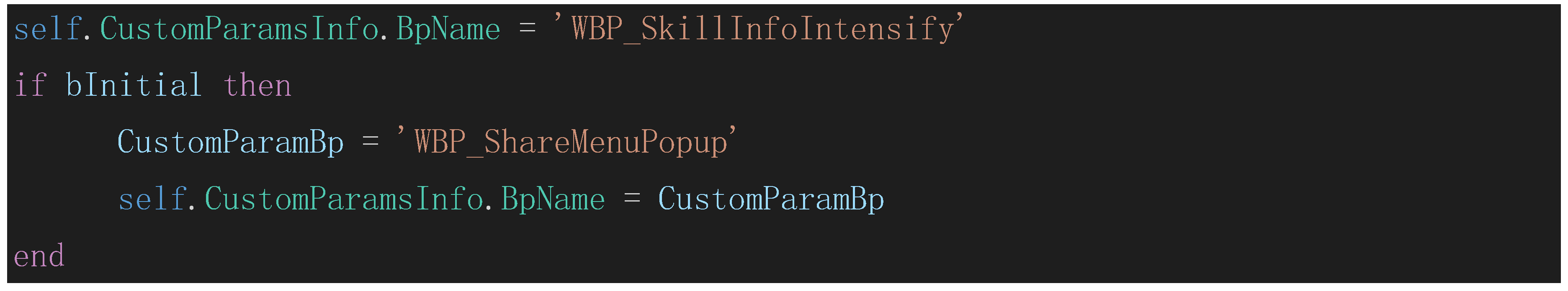

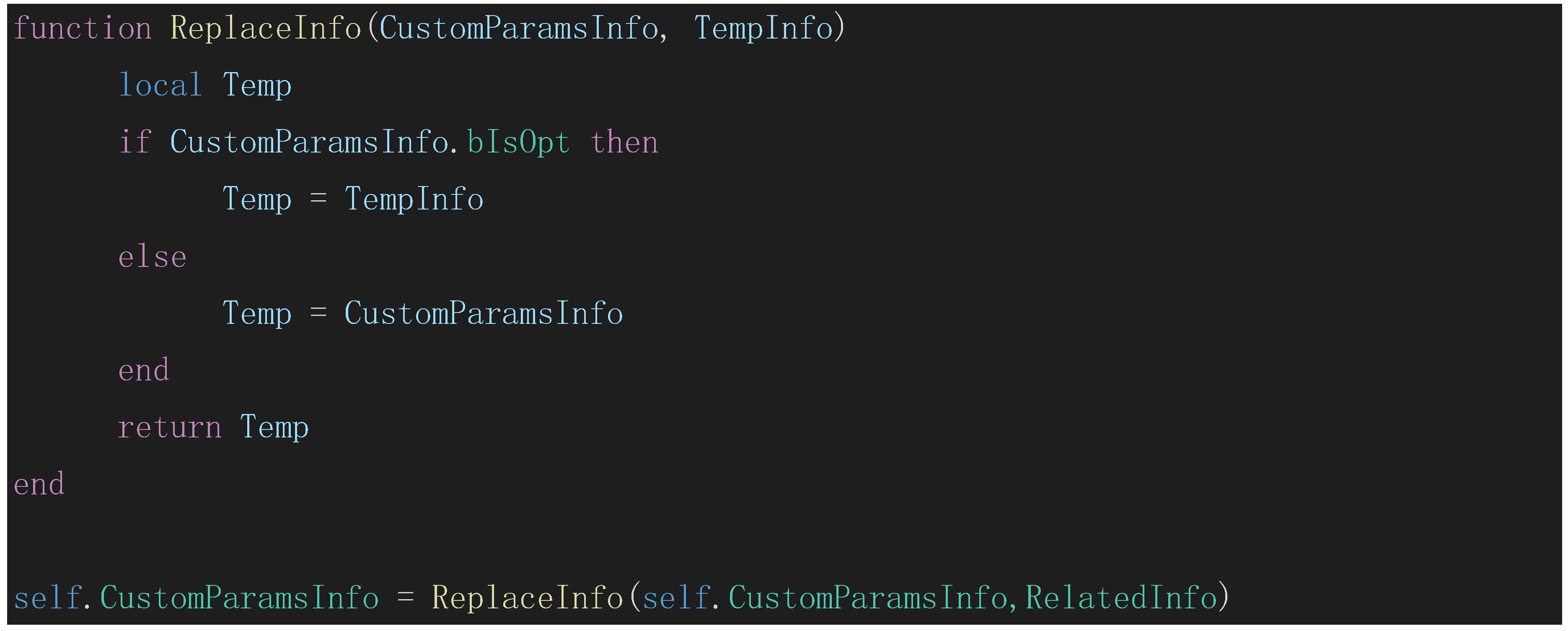

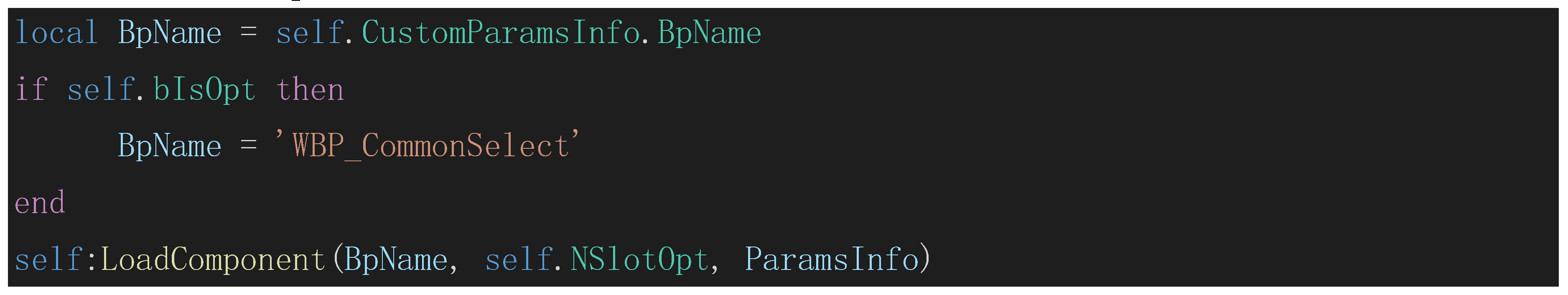

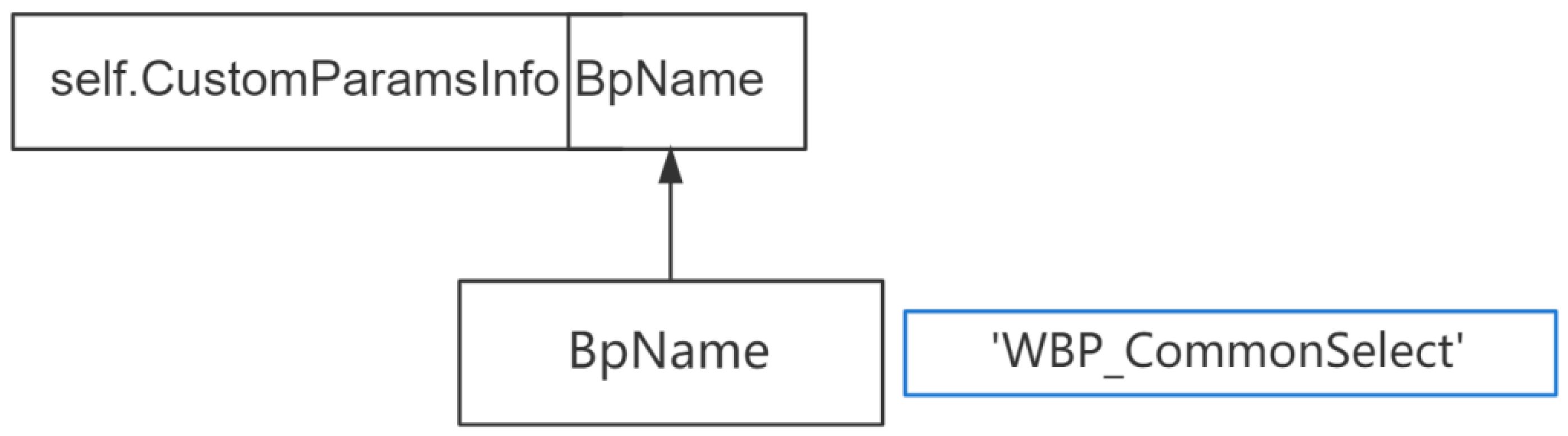

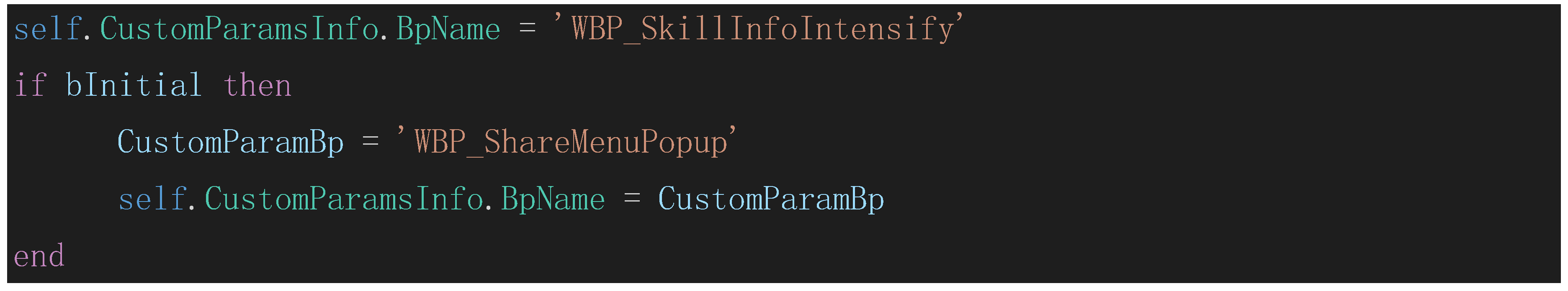

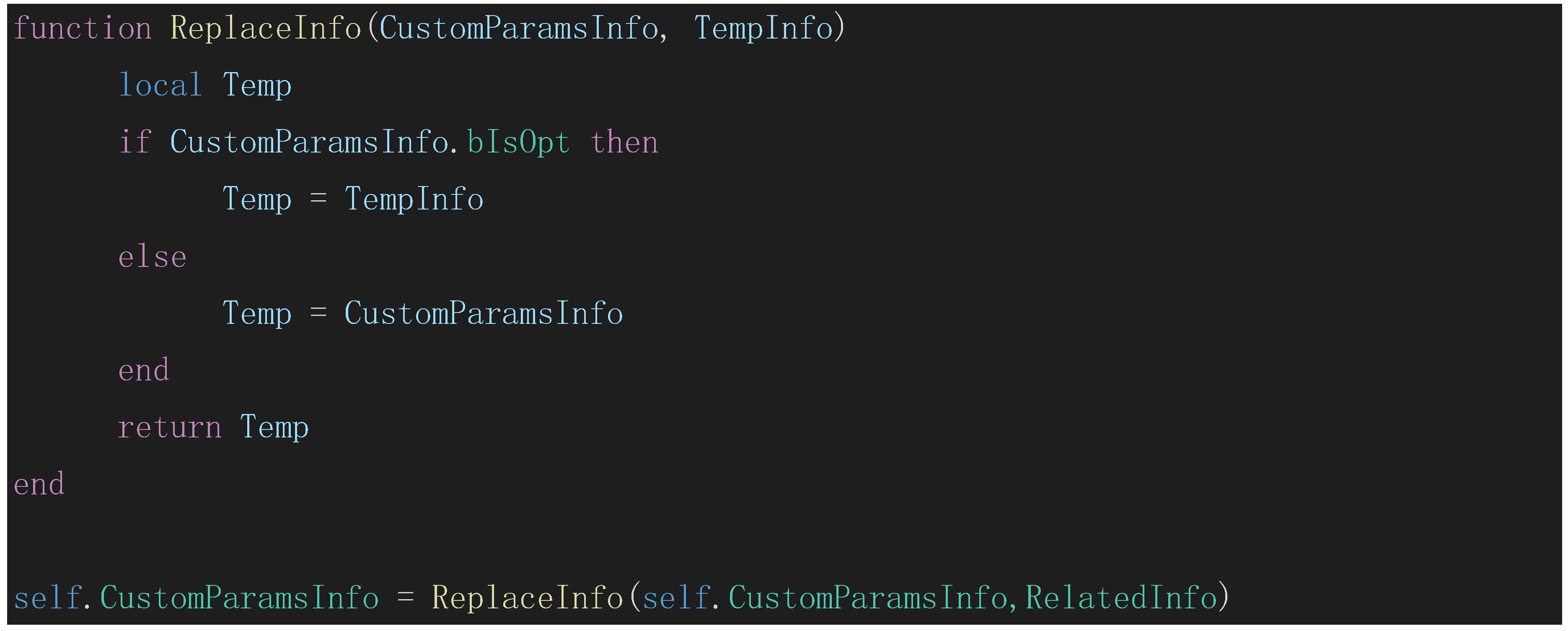

For the analysis of function calls, such as code chip:

The function

replaceInfo indirectly modifies

self.CustomParamsInfo.BpName by modifying

self.CustomParamsInfo. So according to the rule

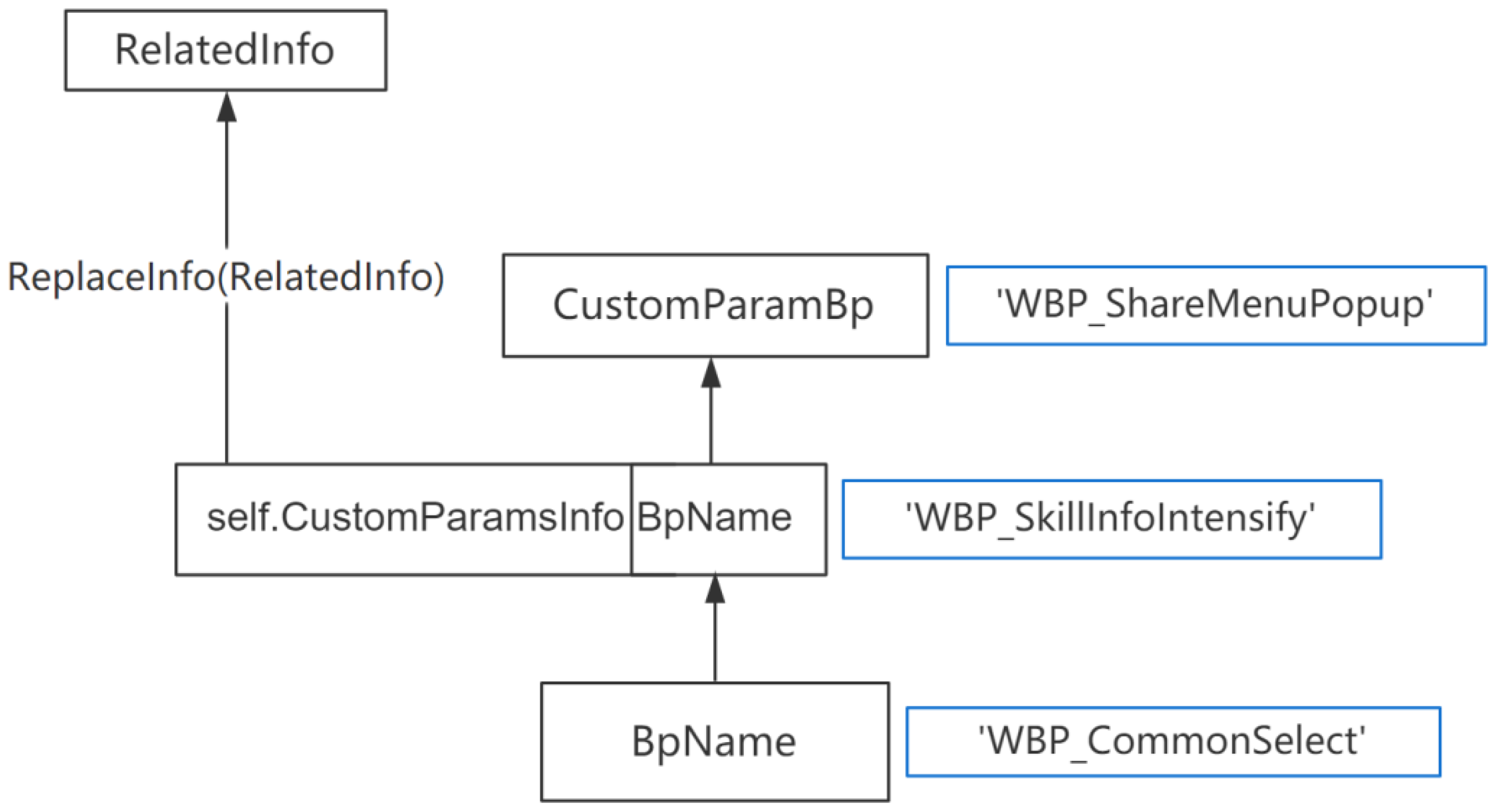

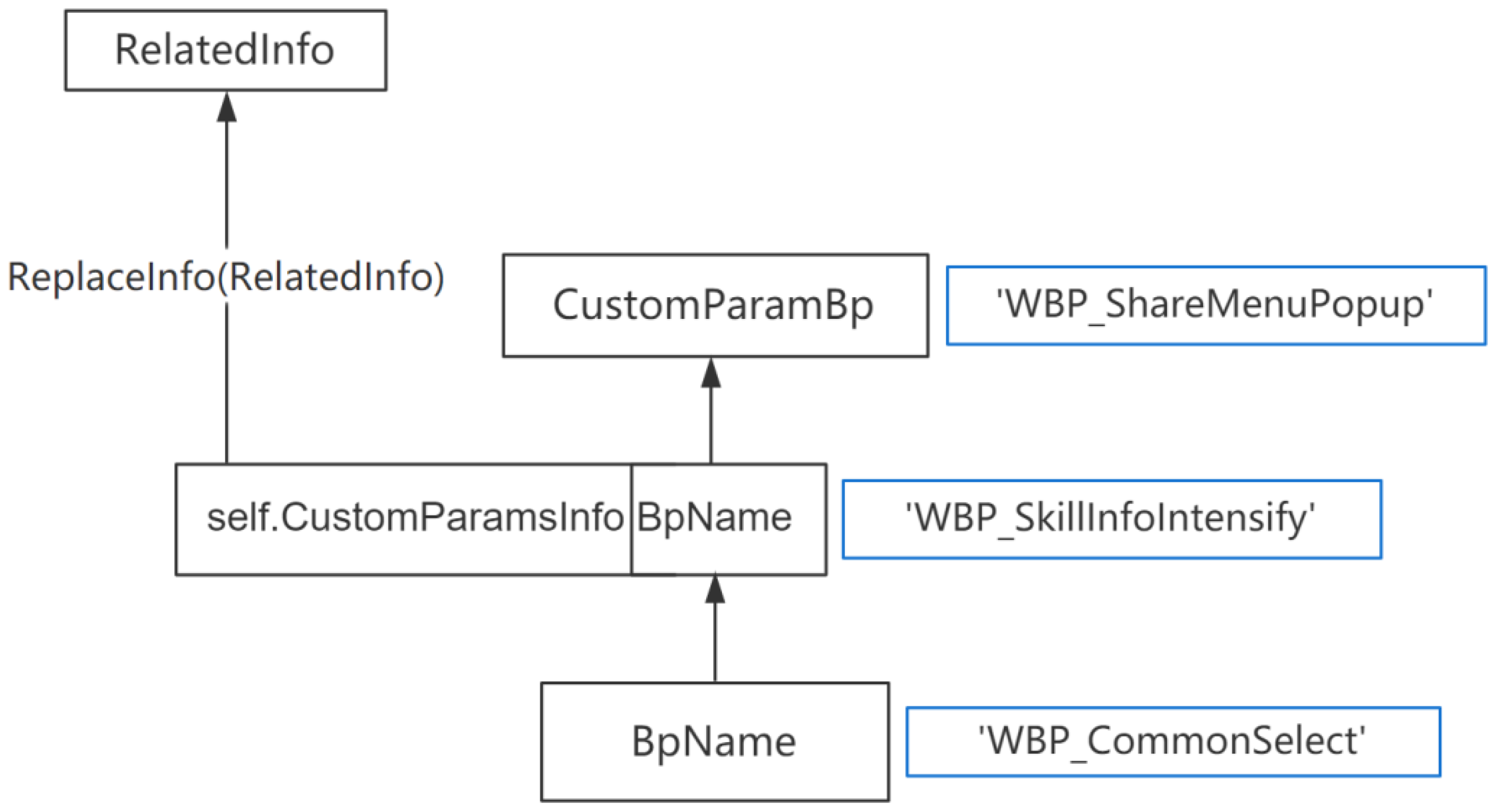

, update the data flow graph to:

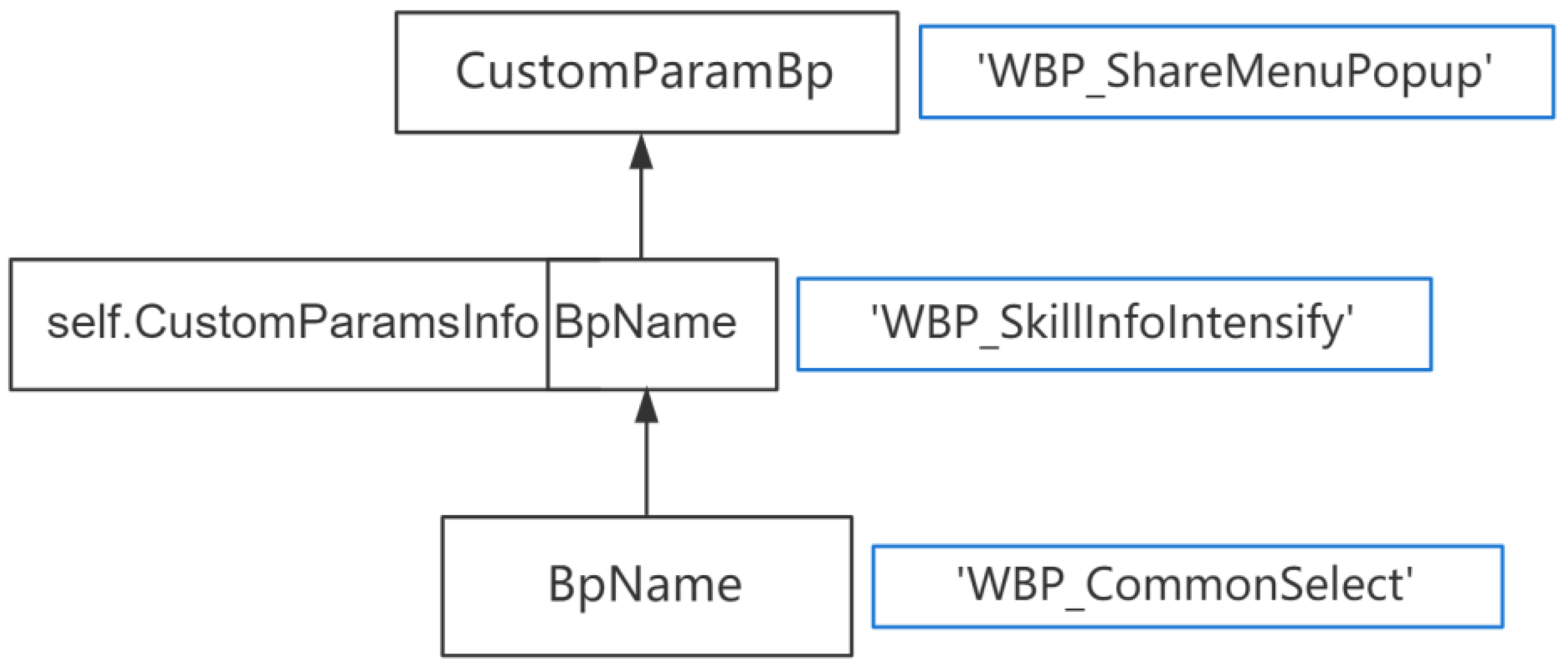

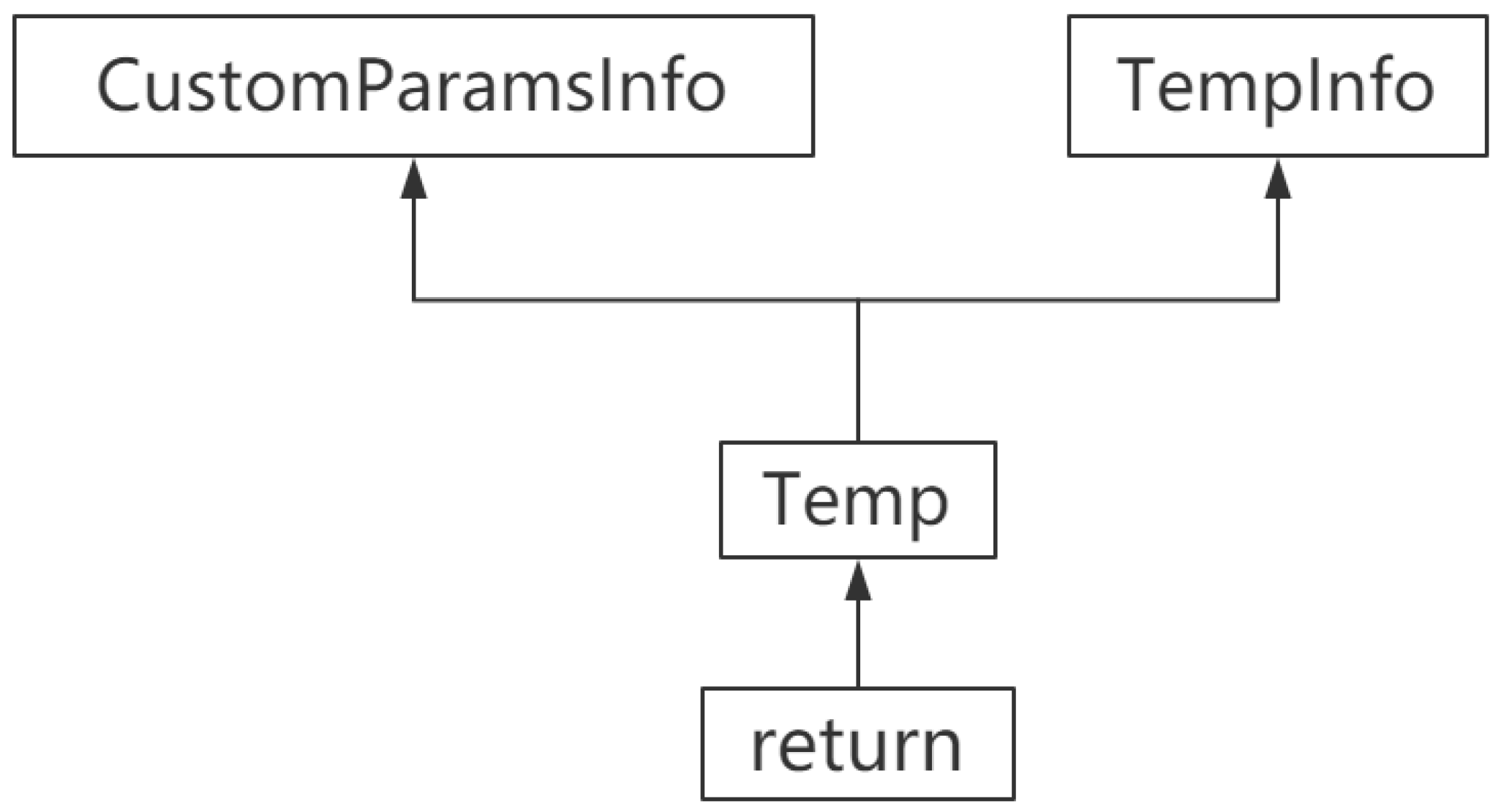

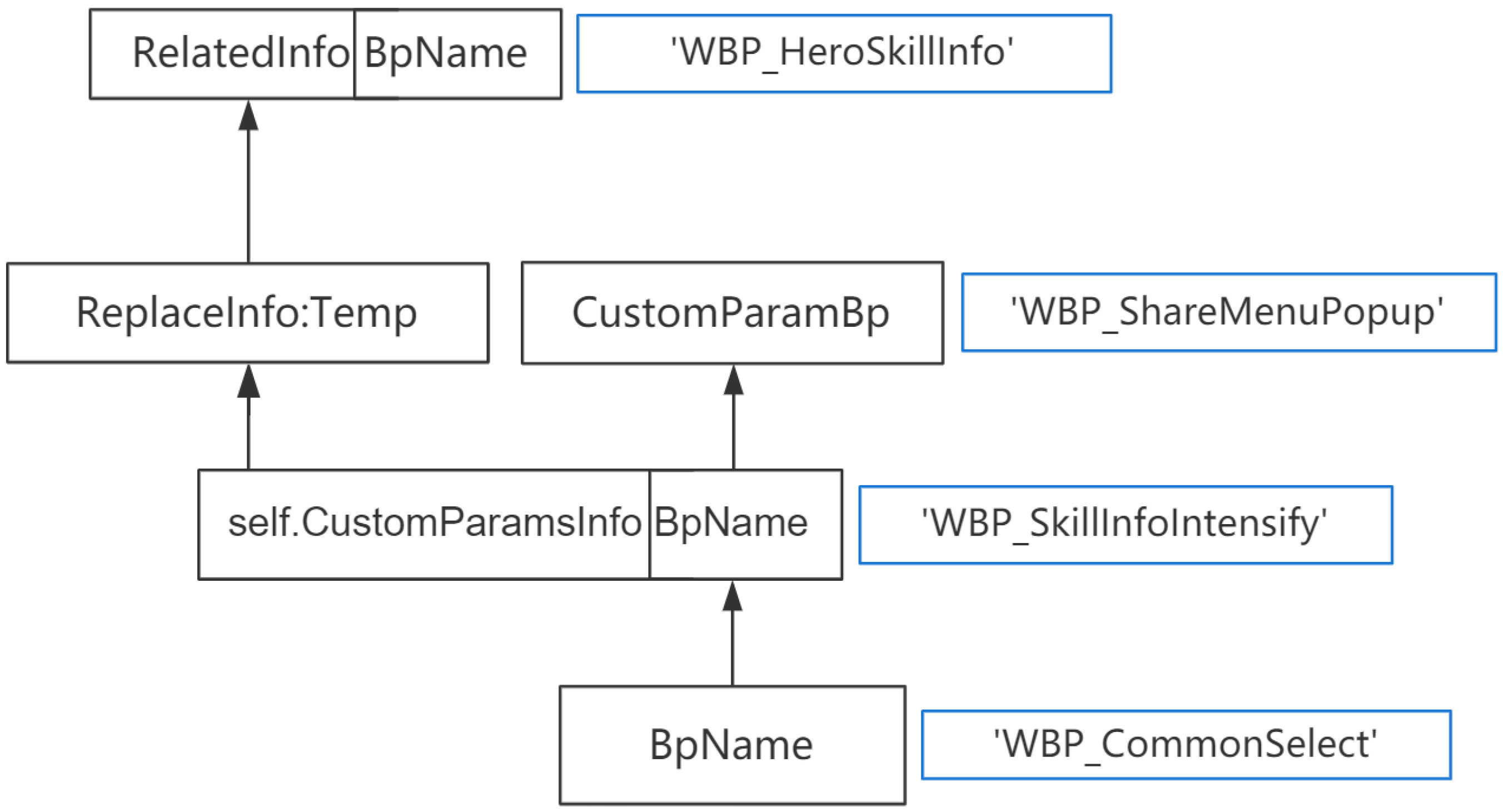

Then build a separate data flow graph

corresponding to the

replaceInfo:

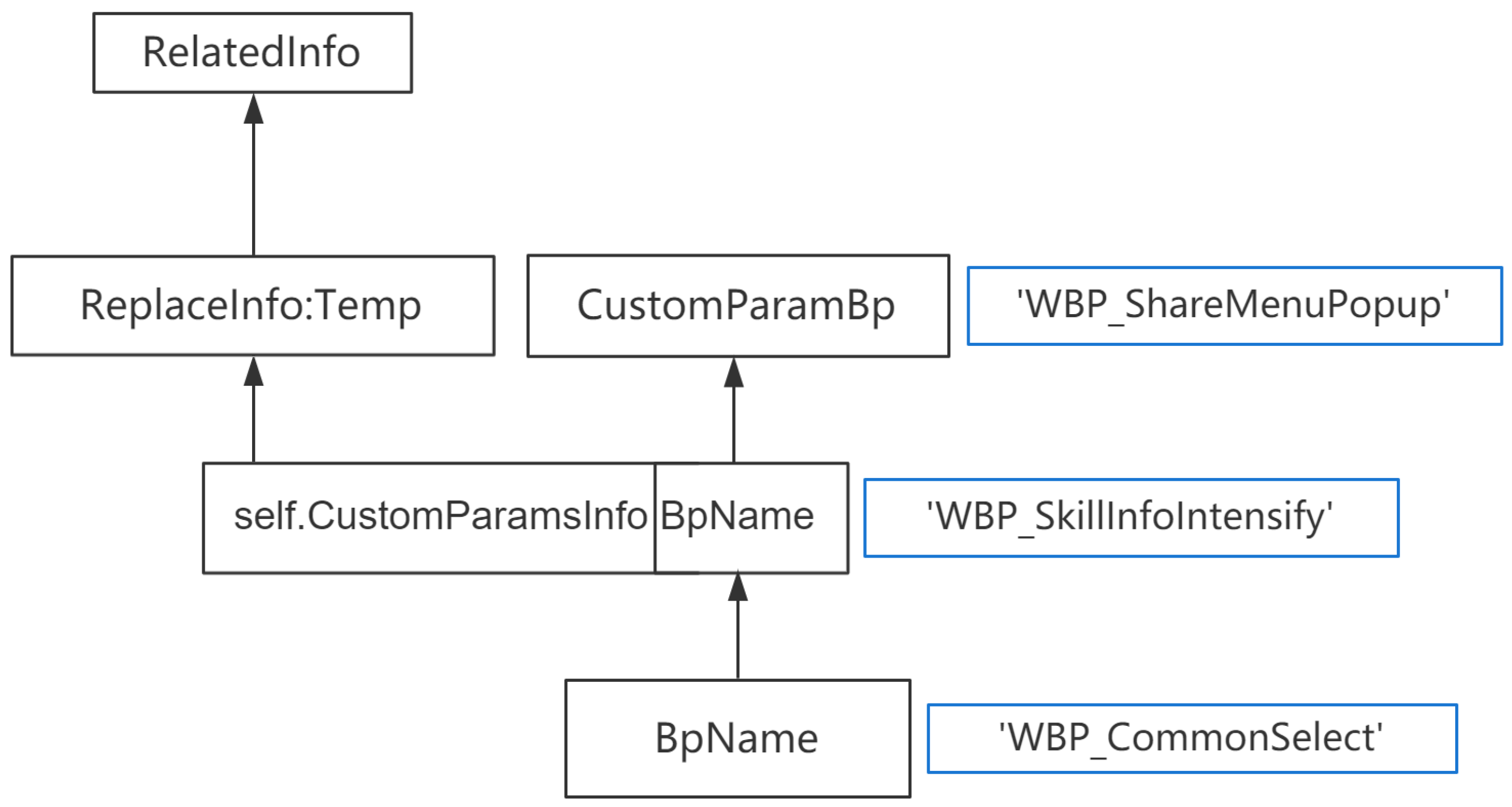

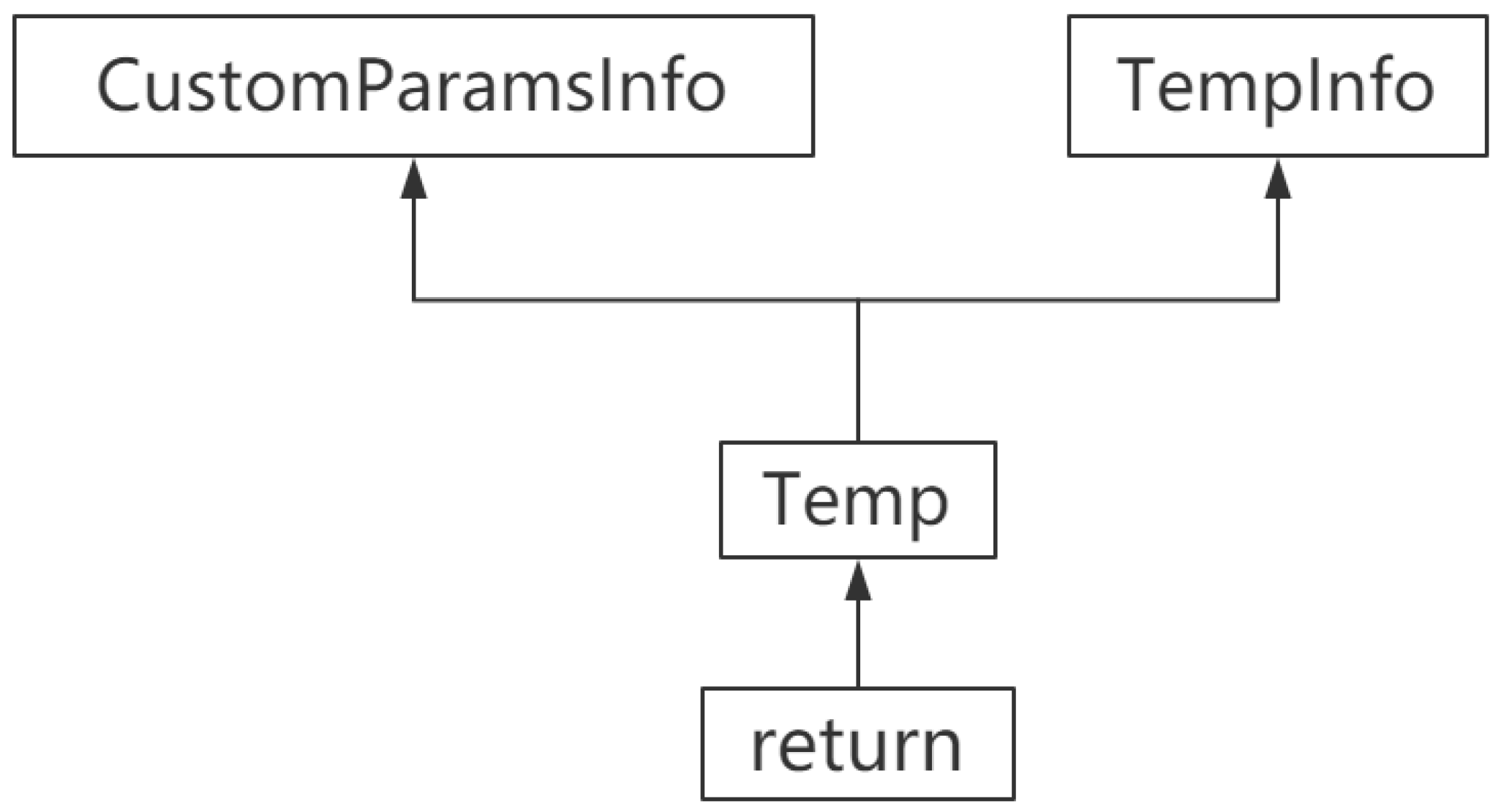

Apply the rule

to replace the newly added nodes in

with

:

Then the algorithm will collect the modification points of the newly added symbol

ReplaceInfo (Step 1) and literal assignment to

ReplaceInfo.BpName (Step 2). If there is code:

Then the data flow graph

becomes:

For code involving string calculations such as substitution and concatenation. At present, some string static analysis algorithms can analyze the patterns that generate string symbols (such as automata [

3,

4,

7,

8] or regular expressions [

5,

6]). If any asset can match the pattern of the symbol, then it is considered to be in use.

Conclusion

Our method uses asset loading points as the root to construct a data flow graph in reverse. This method can determine which symbols to abstract. Due to the fact that only a small portion of the code is related to loading points, a large number of paths that do not interact with valid symbols will not be detected, effectively reducing the cost of analysis. In addition, in some cases, due to the complexity of real-world programs, the precise data flow of actual parameter variables is incalculable (resulting in false negatives), so our reverse analysis tool supports manually marking parameter ranges at the loading point.

References

- Shun, N.A. Analysis Technology Reseach of Data Flow Oriented Java Program Pointer[J]. Computer Programming Skills & Maintenance 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen, R. University of Alberta Expression Data Flow Graph: Precise Flow-Sensitive Pointer Analysis for C Programs. University of Alberta, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, M.I.; Kim, D.; Perkins, J.; et al. Information-Flow Analysis of Android Applications in DroidSafe[C]. Network & Distributed System Security Symposium; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arceri, Vincenzo; Mastroeni, Isabella. Static Program Analysis for String Manipulation Languages. Electronic Proceedings in Theoretical Computer Science 2019, 299, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Negrini, L.; Arceri, V.; Ferrara, P.; et al. Twinning Automata and Regular Expressions for String Static Analysis[C]. Springer: Cham, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, M.T.; Chu, D.H.; Jaffar, J. S3: A Symbolic String Solver for Vulnerability Detection in Web Applications. ACM 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aske Simon, Christensen; Anders, Møller; Michael, I. Schwartzbach. Precise Analysis of String Expressions. BRICS Report Series 2003, 10, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, D.; Ghosh, I.; Rajan, S.; Khurshid, S. Efficient symbolic execution of strings for validating web applications. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Defects in Large Software Systems Held in conjunction with the ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis (ISSTA 2009) - DEFECTS '09 2009; pp. 22–26.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).