1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive, chronic neurodegenerative disorder characterized by motor symptoms, including tremors, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural disturbances. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN-DBS) is a standard procedure for treating tremors and motor complications [

1,

2]. The impact of it on axial symptoms is still uncertain. Studies have shown that STN-DBS patients experience improved postural instability and gait disturbances. On the contrary, long-term follow-up studies revealed different effects on posture and gait, most showing deterioration.[

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]

Furthermore, the parameters used in stimulation, such as voltage, pulse width, or frequency, are essential to study to establish optimal beneficial effects [

7,

8]. Su et al. showed in a meta-analysis that the low- and high-frequency stimulation of STN had a different impact on motor symptoms and freezing of gait[

9]. Therefore, this study hypothesizes that different frequencies of STN-DBS will have various effects on postural control in individuals with Parkinson's Disease. The primary aim of this study is to quantitatively evaluate the impact of frequency changes on postural control performances of individuals with PD who had bilateral STN-DBS

2. Materials and Methods

This case series study was conducted at Eskisehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Medicine. Patients with PD and STN-DBS were recruited from the movement disorders outpatient clinic between May 2021 and June 2022. They were assessed under different DBS frequency conditions in the Research Institute for Individuals with Disability, Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Clinic of Anadolu University, Eskisehir. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee (Approval no/date: 2021034-2021/5) of Eskisehir Osmangazi University Medical Faculty. This study has been carried out by the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) 1975, as revised in 2013. All patient details have been de-identified to prevent the possibility of patient identification. The reporting of this study conforms to STROBE guidelines[

10].

2.1. Participants

Before participating in the research, every participant gave written consent after being fully informed. We included patients with PD diagnosed according to UK brain bank criteria [

11] who had STN-DBS and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) higher than 25[

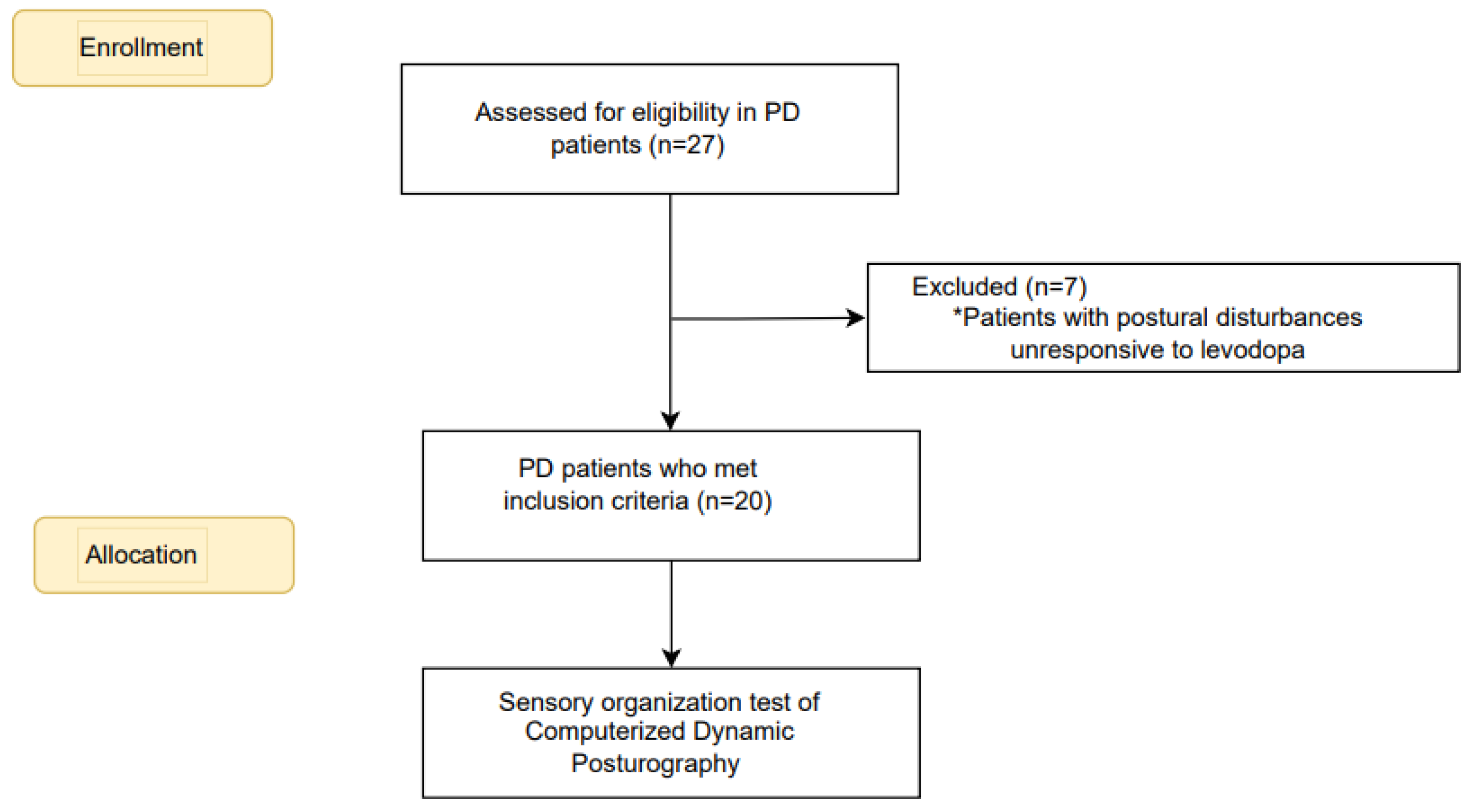

12]. Individuals with other neurological, musculoskeletal, cognitive, or psychological conditions causing gait and postural control disruption were excluded. Patients whose postural disturbances were unresponsive to levodopa were also excluded. The power analysis indicated a sample size of 20 participants was adequate to detect meaningful differences in postural control measures. The flowchart for the recruitment and allocation of PD patients is summarized in

Figure 1.

2.2. Procedures

Demographic (age, height, weight) and clinical characteristics (disease duration, time after surgery, modified Hoehn and Yahr stage, levodopa equivalent daily doses [

12]of the participants were collected. Cognitive functions were evaluated with MMSE [

12]. Participants were assessed with the Turkish version of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale Part III (UPDRS III) [

13] and the Freezing of Gait Questionnaire (FOGQ) [

14,

15]

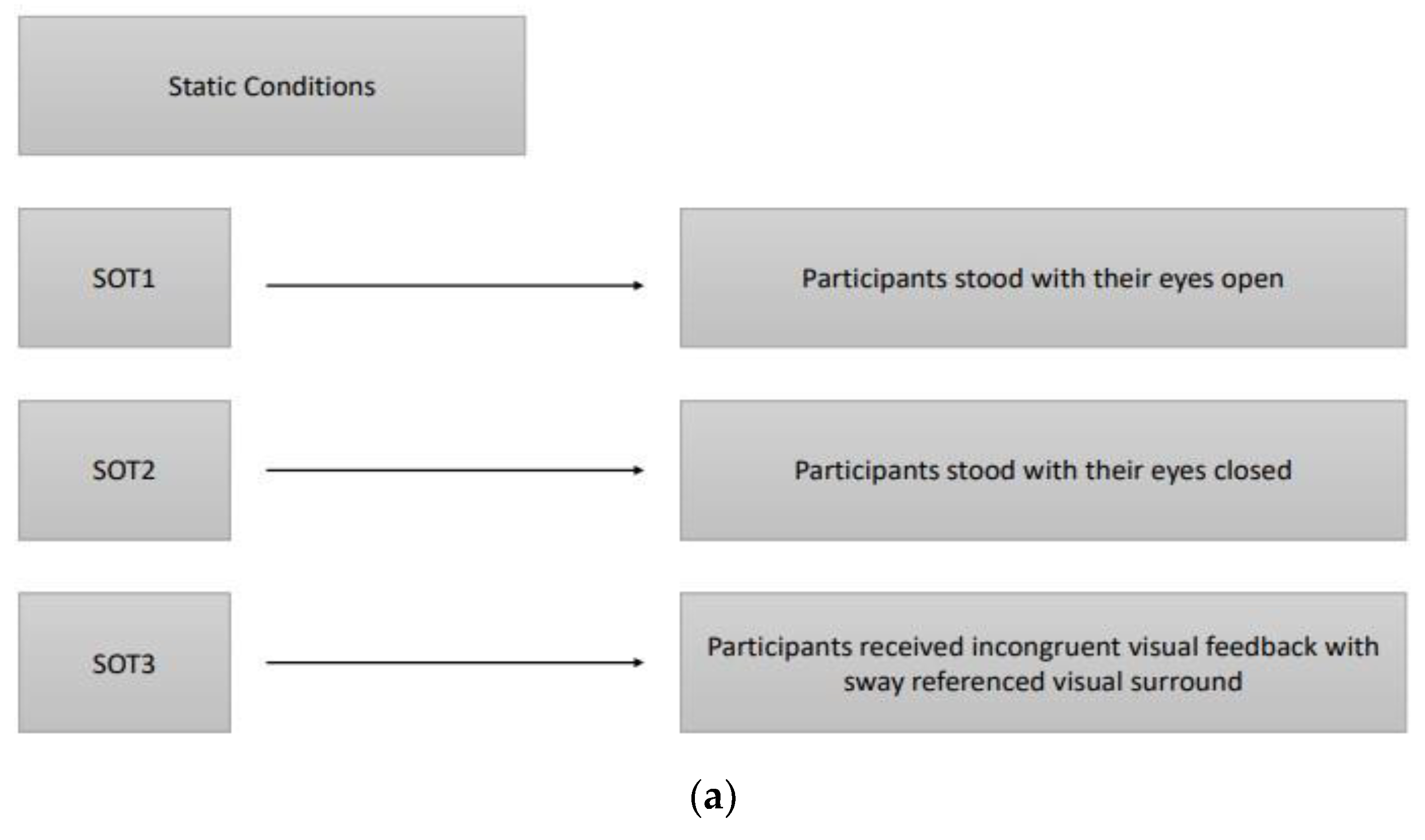

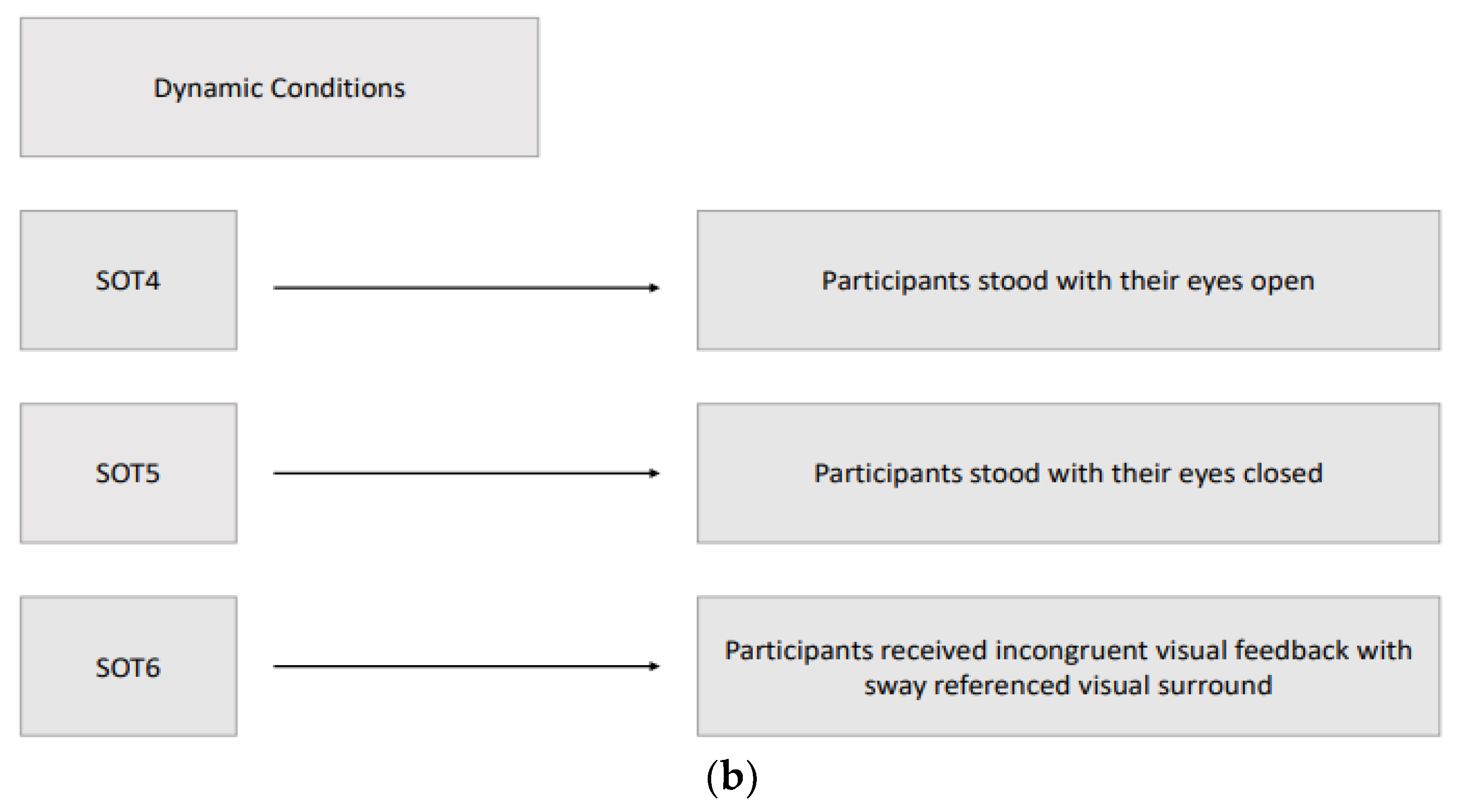

Postural control was evaluated by sensory organization test (SOT) of Computerized Dynamic Posturography (CDP) (Smart Balance Master, NeuroCom International, Inc., Clackamas, Oregon, USA)[

16]. Six different conditions (three static and three dynamic) were used to assess the participant's ability to maintain an upright stance without excessive swaying, integrating somatosensory, visual, and vestibular inputs. The three static conditions with a stable force plate were: SOT1, participants stood with their eyes open; SOT2, participants stood with their eyes closed; SOT3, participants received incongruent visual feedback through a moving visual environment that did not match their physical sway, simulating sensory conflict. The three dynamic conditions with a rotated force plate about the ankle joint axis in proportion to the participant’s spontaneous anterior-posterior (AP) sway were: SOT4, participants stood with their eyes open; SOT5, participants stood with their eyes closed; SOT6, participants received incongruent visual feedback with sway referenced visual surround. In the sway-referenced visual surround conditions, both the visual surround and the platform moved in sync with the participant’s body sway, creating a challenging postural environment and the participant's visual environment rotated around the ankle joint axis in proportion to their spontaneous sway, similar to the movement of the platform in dynamic conditions. The participant's sway within expected angular stability limits during each SOT condition is indicated by the equilibrium score. Participants who had little sway achieved scores near 100, while those approaching their limits of stability scored near zero. During the SOT, participants were evaluated three times in each condition to obtain an equilibrium score ranging between 0-100, of which 100 indicated the best postural balance, and the final equilibrium score for each condition was calculated by taking the average of three scores. Furthermore, a composite equilibrium score was also calculated by taking the average of all scores of six conditions. In addition to the equilibrium score, CDP measured “initial alignment” and “strategy” scores during each SOT condition. The “Initial alignment” score shows a participant’s initial center of gravity (COG) position before each SOT trial. The force plate also measured vertical forces that, along with the participant's height, were used to calculate the COG angle. In CDP, the change in the COG angle about the ankle joint for both feet was measured in real-time [

16]. If the participant’s COG is behind or to the left of their center of foot support, the initial alignment values are reported as negative; if the participant’s COG is in front or to the right of their center of foot support, the initial alignment values are positive. The participant's "Strategy" score reflects their use of ankle and hip movements to maintain equilibrium during each 20-second trial. A score near 100 indicates that the participant primarily uses the ankle strategy to maintain equilibrium, while a score near 0 shows that the participant primarily uses the hip strategy (NeuroCom

®, 2011). The composite balance score was calculated by averaging the balance scores obtained from the six SOT conditions.

Assessments were performed by researchers (a neurologist and a physical therapist) experienced in movement disorders when the best motor response of patients was available at the 'on' state with stimulator adjustments and antiparkinsonian medication, typically 60 minutes after intake of levodopa. Order of the DBS frequency parameters of each participant was randomized, and there was 10-minute waiting period among the low/L (60 Hz), high/H (130 Hz), and very high/VH frequency (180 Hz) treatment settings to expire the effect of the previous frequency setting. Three static and three dynamic sensory organization test (SOT) conditions of Computerized Dynamic Posturography are summarised in

Figure 2.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Mean ± Standard Deviation and Median values were given in descriptive statistics for continuous data, and number and percentage values were given in discrete data. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine the conformity of the data to normal distribution. Friedman's 2-way ANOVA analysis was used to compare the Equilibrium values at 60 Hz, 130 Hz, 180 Hz in the SOT positions of the patients, and Friedman's Multiple Comparisons (post-hoc) test was used to determine the time between the measurements. IBM SPSS for Windows 20.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL) program was used in the evaluations, and p<0.05 was accepted as the statistical significance limit. The data of the research is added as a Supplement (Supplement 1)

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Participants

The study included the data of 20 participants with PD (9 women and 11 men) with a mean age of 61.2±10.1 years. The mean duration of disease was 13.7±5.0 years, and the mean duration of STN-DBS surgery was 3.7±2.2 years with a range of 1-9 years. Participants had a Hoehn & Yahr stage range between 1 and 3 and UPDRS III scores between 22 and 29. Demographics and clinical characteristics are given in

Table 1.

3.2. Static Postural Control

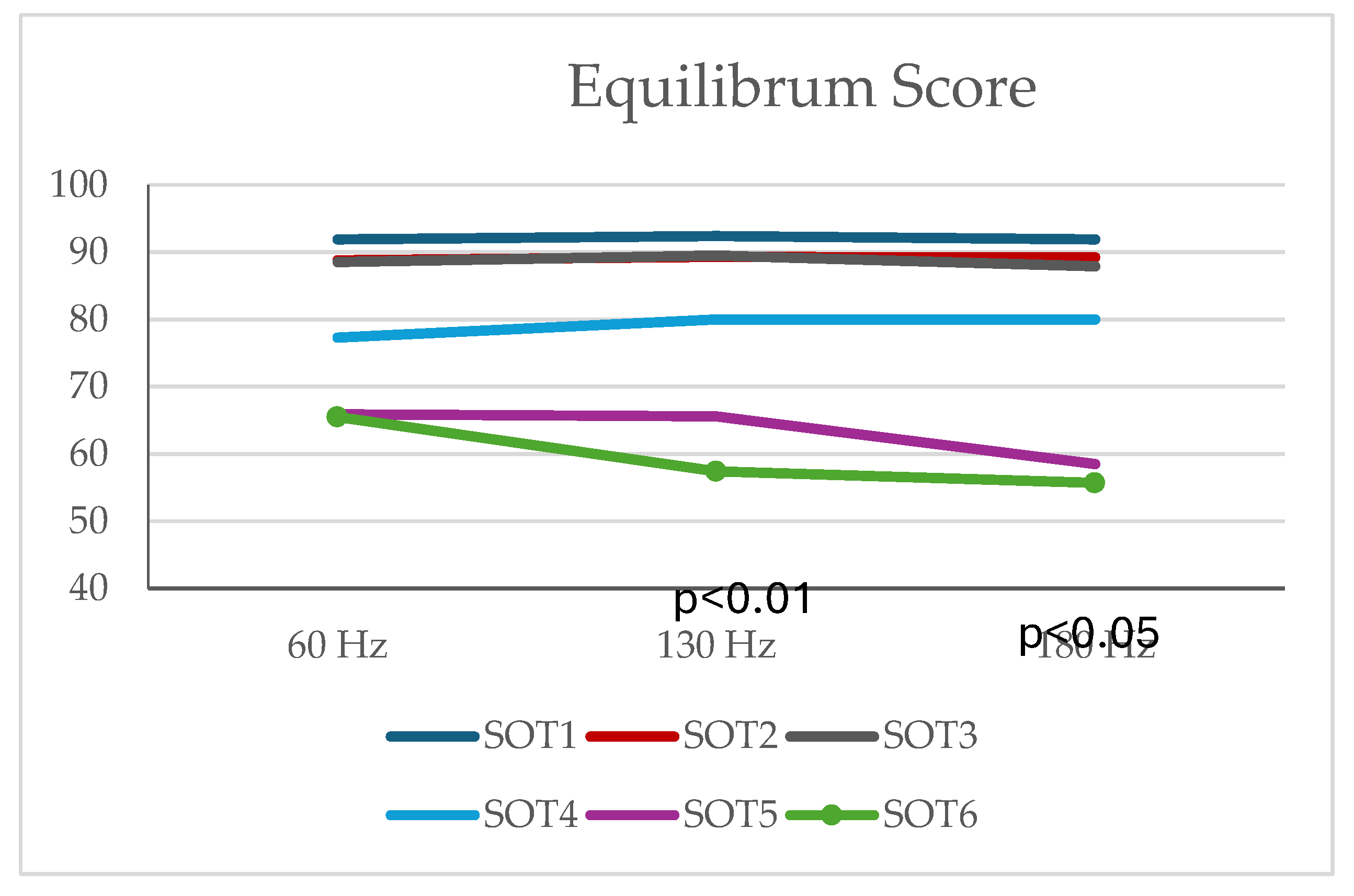

No difference was found between the Equilibrum values at 60 Hz, 130 Hz, 180 Hz in SOT1, SOT2, and SOT3 positions (p>0.05) (

Table 2,

Figure 1).

3.3. Dynamic Postural Control

There were no differences in equilibrium scores of SOT4 and SOT5 conditions. There was a difference between the Equilibrum values at 60 Hz, 130 Hz, 180 Hz in SOT6 position (p<0.01). According to Friedman's Multiple Comparisons (post-hoc) test results, there was a difference between Equilibrum values at 60 Hz and 130 Hz and between Equilibrum values at 60 Hz and 180 Hz. Equilibrum values at 130 Hz were found to be lower than the Equilibrum values measured at 60 Hz (p=0.004) and Equilibrum values at 180 Hz were found to be lower than the Equilibrum values measured at 60 Hz (p=0.028). There was no difference between Equilibrum values at 130 Hz and 180 Hz (p>0.05) (

Table 2,

Figure 3).

According to the post-hoc analysis, participants with 60 Hz showed significantly better equilibrium performance in SOT6, which is disturbed visual & somatosensory and undisturbed vestibular systems. The participants had similar COG and strategy scores between 60, 130, and 180 Hz frequencies (p> 0.05 for all scores). There was no difference between the Composite Scores at 60 Hz, 130 Hz and 180 Hz (p>0.05).

4. Discussion

This study may be one of the most structured studies to evaluate the effect of several frequency parameters on postural sway in patients with PD with STN-DBS. We assessed the effect of low-frequency stimulation between 60 Hz, high-frequency stimulation at 130 Hz, and very high-frequency stimulation at 180 Hz on postural control in patients with PD who underwent bilateral STN-DBS, using objective measurements. Results from the current study revealed that the performance at low frequencies was similar to that at higher frequencies. Values of postural sway did not differ in selected frequency parameters. The only exception was SOT6, in which individuals did better on low frequencies (60 Hz) when compared with higher frequencies (130, 180 Hz). This suggests that the mechanisms of STN-DBS frequency modulation may involve more complex interactions with sensory integration processes, potentially affecting neuroplasticity in sensory pathways. Future research could explore these mechanisms further to enhance therapeutic strategies

. The DBS frequency settings for improvement of axial symptoms of PD are still controversial. An increasing number of reports have explored the use of low-frequency stimulation on gait symptoms[

17,

18,

19,

20] and postural control [

20].

4.1. Static Postural Control

For static postural control, there was no effect of using either 60, 130, or 180 Hz frequency stimulation. Previous studies have shown the improvement of clinical measures of postural stability with low-frequency (60 Hz) STN-DBS. In a trial by Xie et al. [

21], individuals with PD who underwent STN-DBS were compared for the effects of 60 Hz and 130 Hz stimulation. The results showed that 60 Hz stimulation significantly improved axial symptoms, which included swallowing, as assessed by UPDRS III axial subscores. On the contrary, Vallabhajosula et al. [

20] also studied the impact of low- (60 Hz) and high-frequency (>100 Hz) STN-DBS on postural control and gait characteristics and revealed no significant differences between these frequency levels. In this current study, there was no effect of using either low, high, or very high-frequency stimulation for static postural control.

4.2. Dynamic Postural Control

The results for dynamic stability reported by studies investigating different STN-DBS stimulation settings are almost entirely subjective, with clinical scales or accelerometer-based harmonic ratio measurements[

17,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Dynamic postural control can be evaluated objectively with accelerometer-based harmonic ratio measurement. Higher harmonic ratios were considered to represent greater gait rhythmicity and dynamic postural stability. Dynamic postural control was evaluated by calculating the harmonic ratio with an accelerometer. A study conducted this way reported that lower frequency was better with dynamic postural control. However, in the current study, the method gives information about dynamic postural control with a more objective, quantitative, and reliable method. Another study revealed that the dynamic postural control at low-frequency was similar to the higher frequency stimulations. In that study, only eyes-opened and closed evaluations were performed[

20]. Similarly, the current study showed no difference between the frequencies of SOT4 (eyes open) and SOT5 (eyes closed) performances. In addition, the present study showed that 60 Hz patients had significantly better equilibrium performance in SOT6, which is a disturbed visual & somatosensory system and undisturbed vestibular system condition. The dynamic postural controls of the participants are only impaired when they are challenged. The effect of very high-frequency stimulation on dynamic postural control has not been evaluated in previous studies. In the current study, the effect of not only low-frequency but also very high and high-frequency stimulation was examined. Dynamic postural control in very high-frequency stimulation is unchanged compared to high-frequency. In brief, we think that the reason for the controversial result of previous studies in the measurement methods. When evaluated objectively, the difference between frequencies regarding postural control is negligible. While our findings suggest minimal postural disturbance across frequencies, clinicians should consider the study's limitations, including the short duration of frequency application. Longer stimulation periods may yield different outcomes.

4.3. Limitations

The current study has several limitations. The small sample size (n<30) potentially affecting the generalizability of the results to a larger population. A 10-minute adaptation period was used among the three frequency conditions so a more extended period could evoke various results in the dependent variables. All measurements were performed in an ON-medication state, so an interaction of various frequency stimulation with medication could stimulate some effects on the postural control. In addition, it could be better to interpret the results and the change in adults' postural control levels in different test conditions and frequencies by applying more than one measurement. The results in the current study do not reflect the long-term effects of the various frequency conditions; they include acute effects on the postural control.

5. Conclusions

Results from the current study indicated that though low-frequency stimulation (60 Hz) produced similar results compared to high (130 Hz) and very high-frequency (180 Hz) stimulation for postural control, the low-frequency may be useful for individuals with PD who were over-reliant on visual cues and ineffective use of somatosensory and vestibular cues. In addition to the sensory organization test, various motor control tests should be applied to verify the short and long-term effects of low-frequency stimulation on the target group.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, The data of the research is added as a Supplement (Supplement 1).

Author Contributions

In this study, N.D.C., S.O., M.Y., and E.G.Y.T. Methodology was developed by N.D.C., S.O., and M.Y., who also handled the software aspects. Validation and formal analysis were performed by N.D.C. , M.K.K., and E.G.Y.T.,who also led the investigation and data curation efforts. Resources were provided by N.D.C., S.O., M.K.K. and A.Y.K. The original draft of the manuscript was written by N.D.C., S.O., M.Y., and A.Y.K., while review and editing were done by N.D.C., M.Y., S.O., E.G.Y.T, and A.Y.K. Visualization was managed by N.D.C. and S.O., with supervision provided by S.O. Project administration was undertaken by N.D.C. and S.O.

Funding

The study did not require any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is a case series study conducted at Eskisehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Medicine. Patients with PD and STN-DBS were recruited from the movement disorders outpatient clinic between May 2021 and June 2022. They were assessed under different DBS frequency conditions in the Research Institute for Individuals with Disability, Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Clinic of Anadolu University, Eskisehir. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee (Approval no/date: 2021034-2021/5) of Eskişehir Osmangazi University Medical Faculty. This study has been carried out by the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) 1975, as revised in 2013. All patient details have been de-identified to prevent the possibility of patient identification. The reporting of this study conforms to STROBE guidelines9.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study before participation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors. We can confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available and can be shared (Supplement 1).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to our Parkinson’s nurse, Nazan Korul, for her invaluable support and contributions to this study. Her assistance with collecting data, communication with patients, and data collection were instrumental in the successful completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This study was conducted without any external funding. The authors independently designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and made the decision to publish the result.

References

- S. J. Groiss, L. Wojtecki, M. Südmeyer, and A. Schnitzler, "Deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease," (in eng), Ther Adv Neurol Disord, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 20-8, Nov 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Bakker, R. A. M. Bakker, R. A. Esselink, M. Munneke, P. Limousin-Dowsey, H. D. Speelman, and B. R. Bloem, "Effects of stereotactic neurosurgery on postural instability and gait in Parkinson's disease," (in eng), Mov Disord, vol. 19, no. 9, pp. 1092-9, Sep 2004. [CrossRef]

- Castrioto, A. M. Lozano, Y. Y. Poon, A. E. Lang, M. Fallis, and E. Moro, "Ten-year outcome of subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson disease: a blinded evaluation," (in eng), Arch Neurol, vol. 68, no. 12, pp. 1550-6, Dec 2011. [CrossRef]

- P. Krack et al., "Five-year follow-up of bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson's disease," (in eng), N Engl J Med, vol. 349, no. 20, pp. 1925-34, Nov 13 2003. [CrossRef]

- S. Mei et al., "Three-Year Gait and Axial Outcomes of Bilateral STN and GPi Parkinson's Disease Deep Brain Stimulation," (in eng), Front Hum Neurosci, vol. 14, p. 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. J. St George, J. G. Nutt, K. J. Burchiel, and F. B. Horak, "A meta-regression of the long-term effects of deep brain stimulation on balance and gait in PD," (in eng), Neurology, vol. 75, no. 14, pp. 1292-9, Oct 05 2010. [CrossRef]

- V. Dayal, P. Limousin, and T. Foltynie, "Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson's Disease: The Effect of Varying Stimulation Parameters," (in eng), J Parkinsons Dis, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 235-245, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Picillo, A. M. Lozano, N. Kou, R. Puppi Munhoz, and A. Fasano, "Programming Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson's Disease: The Toronto Western Hospital Algorithms," (in eng), Brain Stimul, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 425-437, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Su et al., "Frequency-dependent effects of subthalamic deep brain stimulation on motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis of controlled trials," (in eng), Sci Rep, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 14456, Sep 27 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. von Elm et al., "The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies," (in eng), Lancet, vol. 370, no. 9596, pp. 1453-7, Oct 20 2007. [CrossRef]

- W. R. Gibb and A. J. Lees, "The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease," (in eng), J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, vol. 51, no. 6, pp. 745-52, Jun 1988. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Folstein, L. N. Robins, and J. E. Helzer, "The Mini-Mental State Examination," (in English), Archives of General Psychiatry, vol. 40, no. 7, pp. 812-812, 1983.

- M. C. Akbostanci et al., "Turkish Standardization of Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale and Unified Dyskinesia Rating Scale," (in eng), Mov Disord Clin Pract, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 54-59, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Giladi, H. Shabtai, E. S. Simon, S. Biran, J. Tal, and A. D. Korczyn, "Construction of freezing of gait questionnaire for patients with Parkinsonism," (in eng), Parkinsonism Relat Disord, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 165-170, Jul 01 2000. [CrossRef]

- Acaröz Candan S, Ç. A. , and Ö. TŞ., "Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the freezing of gait questionnaire for patients with Parkinson’s disease.," Neurol Sci Neurophysiol vol. 36, 1, pp. 44-50, 2019.

- A. Frenklach, S. Louie, M. M. Koop, and H. Bronte-Stewart, "Excessive postural sway and the risk of falls at different stages of Parkinson's disease," (in eng), Mov Disord, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 377-85, Feb 15 2009. [CrossRef]

- Z. J. Conway, P. A. Silburn, T. Perera, K. O'Maley, and M. H. Cole, "Low-frequency STN-DBS provides acute gait improvements in Parkinson's disease: a double-blinded randomised cross-over feasibility trial," (in eng), J Neuroeng Rehabil, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 125, Aug 10 2021. [CrossRef]

- Moreau, C.; et al. , "STN-DBS frequency effects on freezing of gait in advanced Parkinson disease," (in eng), Neurology, vol. 71, no. 2, pp. 80-4, Jul 08 2008. [CrossRef]

- V. Ricchi et al., "Transient effects of 80 Hz stimulation on gait in STN DBS treated PD patients: a 15 months follow-up study," (in eng), Brain Stimul, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 388-392, Jul 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Vallabhajosula et al., "Low-frequency versus high-frequency subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation on postural control and gait in Parkinson's disease: a quantitative study," (in eng), Brain Stimul, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 64-75, 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Xie et al., "Low-frequency stimulation of STN-DBS reduces aspiration and freezing of gait in patients with PD," (in eng), Neurology, vol. 84, no. 4, pp. 415-20, Jan 27 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Bellanca, K. A. Lowry, J. M. Vanswearingen, J. S. Brach, and M. S. Redfern, "Harmonic ratios: a quantification of step to step symmetry," (in eng), J Biomech, vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 828-31, Feb 22 2013. [CrossRef]

- Z. J. Conway, P. A. Silburn, W. Thevathasan, K. O. Maley, G. A. Naughton, and M. H. Cole, "Alternate Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation Parameters to Manage Motor Symptoms of Parkinson's Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis," (in eng), Mov Disord Clin Pract, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 17-26, Jan 2019. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).