2.1. Basic Algebra and Definitions

According to Hamilton [

2], the quaternion is defined as

q =

s +

ui +

vj +

wk, where

s,

u,

v and

w are real numbers, and imaginary versors

i,

j and

k fulfil the conditions:

Equation 1 implies that the quaternion multiplication rules can be rewritten as:

Generally, the quaternion can be written as

q=

s+

v, where

v is an imaginary 3-component vector

v =

ui +

vj +

wk. The multiplication between quaternions

q1 and

q2 is represented by equation:

where indices refer to quaternions

q1 and

q2, symbol ‘·’ indicates the scalar multiplication and ‘×’ the vector multiplication of vectors.

It is apparent from Equation 3 that the quaternion multiplication rules (Equations 1-2) are valid only for the Cartesian reference systems, where all three reference axes are mutually orthogonal. When assuming a non-Cartesian system, Equations 1-2 are no longer valid and new appropriate products must be calculated according to Equation 3. The most general least-restricted reference system corresponds to the crystallographic triclinic system, where no relations binding unit-cell parameters

a,

b,

c, α, β and γ are imposed by symmetry elements. In the triclinic setting, we request that unit quaternion vectors

i,

j and

k be collinear with the unit-cell edges, so vector

r = (

i,

j,

k) runs along the unit-cell diagonal in the imaginary space; both scalars

s1 and

s2 are equal to zero (Equation 3). Thus, for the triclinic unit-cell parameters

a ≠

b ≠

c ≠

a and angles α ≠ β ≠ γ ≠ α, all unrestricted to 90° or any other value, we get:

It can be established that

ij = (

ji)*,

jk = (

kj)*,

ki = (

ik)*, where asterisks denote the conjugation. After some algebraic transformations (cf. Appendix), the multiplication rule for quaternions in any 3-axis coordinates can be written in the form:

where

Parameter is connected to the unit-cell volume (V) by the formula V = abc. For a normal Cartesian reference system, where a=b=c=1 and α = β = γ = 90°, all cosines are equal to 0, all sines are equal to 1, and = 1. Then, Equations 4 reduce to Equations 1-2, which define the quaternions in Cartesian coordinates. For a given lattice described by parameters a, b, c, α, β, and γ simplify to the form convenient for practical calculations, as illustrated in several examples below.

The crystallographic symmetry operations in the quaternion representations were recently presented for point groups of all crystallographic systems, except those in the hexagonal setting [

21]. The quaternion formula for rotating imaginary vector r by angle φ about vector v is:

where quaternion

q(φ,

v) is

and

n =

v/|

v| is the unit vector parallel to the rotation-axis vector

v. Owing to the quaternion definition expanded to the non-Cartesian systems (Equations 4), Equation 6 is valid for any rotations, not only those connected to symmetry operations.

The normalization of vector v is mandatory. It is easy in the Cartesian systems, however, for the triclinic reference systems the length of vector

v = [

uvw] is:

where superscript T denotes transposition and

G is the matrix tensor:

Noteworthy, there are non-Cartesian systems where the application of matrix G is required only for the transformations, either of the proper or improper rotations, the directions of which do not coincide with the symmetric directions of the system. In other words, two or three vector components involve versors, which are not symmetry-related. This does not apply to any crystallographic symmetry operations, because by definition their components must be symmetry-related. Owing to this feature, the quaternions representing symmetry operations have simple forms. For example, the inversion centre of the triclinic system is not connected with any direction but reverses the sign of all components; for the monoclinic system the 2-fold axis and the mirror plane are connected to the [y] direction only; in the orthorhombic system, the rotations are either about axes [x], [y] or [z]. The mixed components of the rotation vectors appear in the tetragonal system (diagonal directions [110] and ), hexagonal family (diagonals [120],[210] and [, and cubic system (six flat diagonals of type [110] and four space diagonals of type [111]), but the directions of these rotation axes run along diagonals of regular polygons and a regular polyhedron (only in the cubic system the space-diagonal is symmetric), so their edges are equal and the directions of the diagonals are fixed relative to the crystal reference system. The same applies to symmetric directions in the reciprocal space and to the relation between direct and reciprocal spaces. However, the vectors for non-symmetric directions of rotations require to be normalized using the G matrix.

2.3. Non-Symmetric Transformations

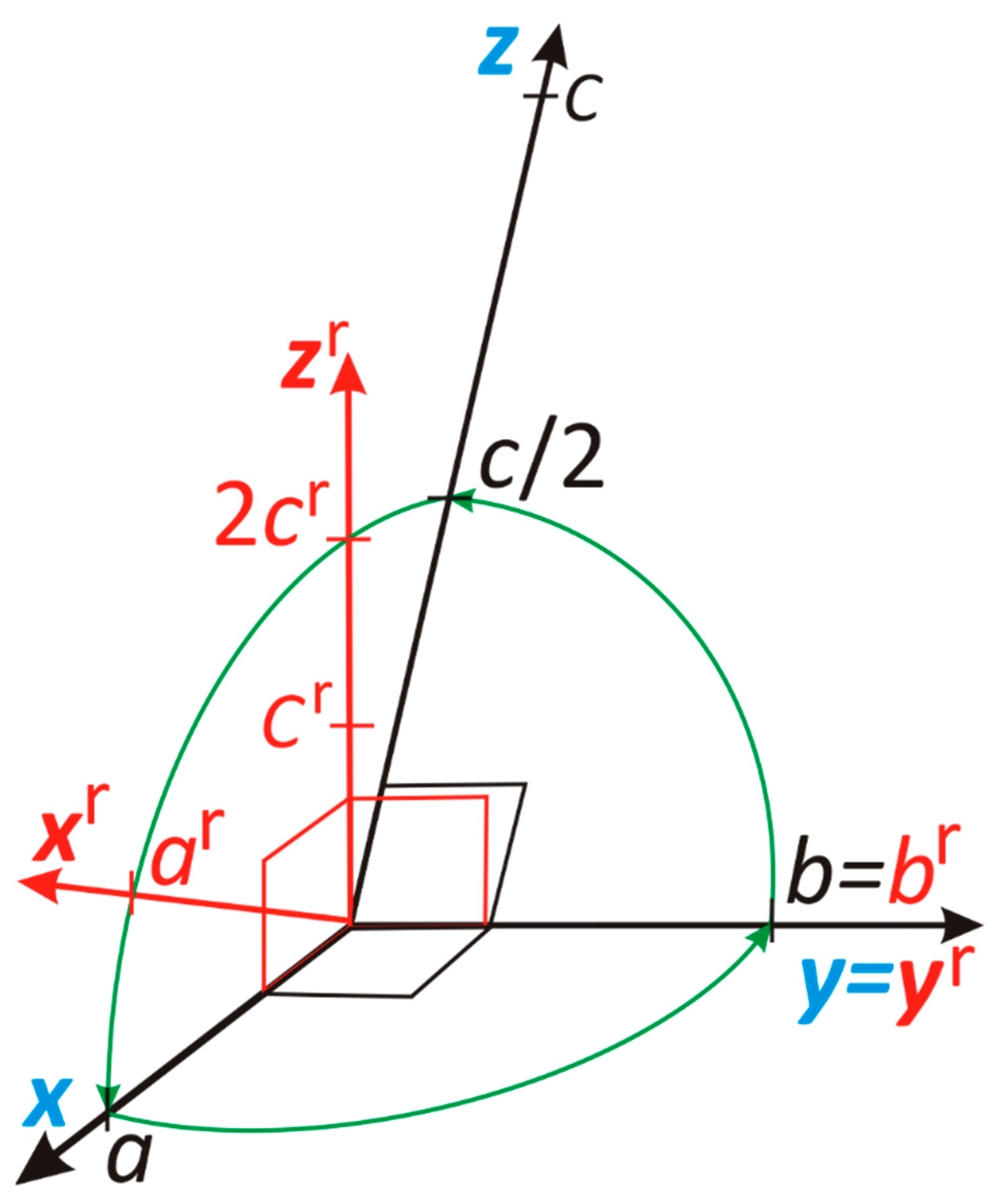

For non-symmetric general transformations in non-Cartesian systems, all lattice parameters should be substituted to Equations 4. Below, we exemplify the quaternion representation of such a non-symmetric rotation by an arbitrary angle about the [y] direction in the monoclinic system. Let’s rotate vector a by angle –β about the [y] direction in the monoclinic reference system, where we assume the following unit-cell parameters:

a =

b = 1,

c= 2; α = γ = 90° ≠ β (

Figure 1).

The substitution of these parameters into the quaternion multiplication rules, specified in Equations 4, gives:

The rotation of

r to

r’ is the leftward rotation, because the rotation angle is negative (–β), so transformation type

r’ =

q*

rq can be applied [

21]:

(for detailed numerical calculations cf. Example S1 in the

Supplementary Materials). Thus, as expected for the assumed relation |

a|=|

c|/2, the rotation of vector a by angle –β around [y], we obtain vector r’ = [0 0 1/2], as shown in

Figure 1.

The next example illustrates the use of reciprocal vectors for quaternion representations of any, not necessarily symmetric, rotations. Hereafter, we will denote the reciprocal vectors by superscript r (instead of the usually used asterisk, to avoid confusion with the conjugation of quaternions). It can be requested for the monoclinic lattice to rotate the a vector about the reciprocal vector cr. According to Ewald’s definition of reciprocal vectors

and for the monoclinic lattice

. The crystal-lattice components of this reciprocal vector

are:

and the unit vector parallel to

is

:

For the example described above (unit-cell parameters: a = b = 1, c = 2; α = γ = 90° ≠ β, as shown in

Figure 1),

. The quaternion for the rightward, 90° rotation around vector

is:

The rotation of vector

a by 90° around the axis

is:

Thus, the rotation by 90° around cr superimposes the image of vector a with vector b along axis [y], as expected for the assumed unit-cell dimensions (

Figure 1).

In the next examples below, we focus on illustrating the advantages of quaternion transformations easily performed in one step in crystallographic coordinates. First, let’s rotate vector r = [001] by an angle of 180° about direction [110] for an orthorhombic lattice with unit cell

a=

b/2=

c=1 and α=β=γ=90°. The multiplication rules for quaternions (Equations 4) in this system are:

So, the quaternion for the requested rotation is:

q(180°, [110]) = (

i +

j)/

and the rotated vector r’ can be calculated as

which corresponds to direct-space crystal-lattice coordinates

r’ = [–3/5, 2/5, 0].

In order to illustrate the effects of skew lattices for the quaternion transformations, let’s consider the non-conventional unit-cell

a =

b/2 =

c = 1, α = β = 90°, γ = 120° (cf. the previous example) and vector r = [100] is to be rotated by angle 180° about the direction [110]. The quaternion multiplication rules (Equations 4) for this system are:

The metric matrix G (Equation 8) is

According to Equation 7, the length of the vector v = [110] is

The quaternion for the rotation by angle 180° about direction [110] is

The rotation of vector r = [100] by angle 180° about direction [110] leads to (cf. Section S4 in the

Supplementary Materials):

which corresponds to the crystal-lattice vector

.

For the same lattice (unit-cell

a =

b/2 =

c = 1, α = β = 90°, γ = 120°, cf. the previous example), let’s now rotate vector

r = [100] by angle 180° about crystal direction

. Hence:

The quaternion for the rotation by angle 180° about direction

is

The rotation vector

r = [100] by angle 180° about direction

is

Thus, the rotation of vector r = [100] about direction

by angle 180° results in vector r’=[–3/7, –4/7, 0]. The calculations are detailed in Section S5 in the

Supplementary Materials).

For somewhat modified unit-cell dimensions

a =

b/2 =

c = 1, α = β = 90°, γ = 120° (cf. the previous example) and vector

r = [100] rotated by angle 180° about direction [110], the quaternion multiplication rules (Equations 4) are:

The metric matrix

G (Equation 8) is

According to Equation 7, the length of the vector v = [110] is

The quaternion for the rotation by angle 180° about direction [110] is

The rotation of vector

r = [100] by angle 180° about direction [110] leads to (cf. Section S4 in the

Supplementary Materials):

corresponding to the crystal-lattice vector

.

2.4. Trigonal System in Hexagonal Setting

All point-group symmetry elements for the crystallographic trigonal system in the hexagonal reference system are listed in

Table 1. We have generally applied the Hermann-Mauguin notation of symmetry elements (1, 2, 3-fold natural axes and their improper analogues

m,

), with the subscripts defining the directions parallel to the rotation axes and perpendicular to the mirror planes. The hexagonal unit-cell coordinates imply the quaternion multiplications defined in Equation 9. For generating the improper rotations, the combination of natural rotations (1, 2 and 3-fold axes) and the inversion centre have been used, which implies the leftward rotation. As shown previously for all point-group symmetry operations, two transformation types,

qrq* and –

qrq*, can be distinguished, which in some cases can be reduced to

qr or

qrq [

21].

For example, the reflection of vector

r = [1, –1, 0] in mirror plane

m[100] can be represented as.

which corresponds to the transformed vector

. For the same mirror plane m[100] and vector

,

gives the transformed vector

.

2.5. Hexagonal System

All symmetry elements for the hexagonal point groups and the quaternion representations of the symmetry operations in the hexagonal reference system are listed in

Table 2. The same notation as in the previous section has been applied.

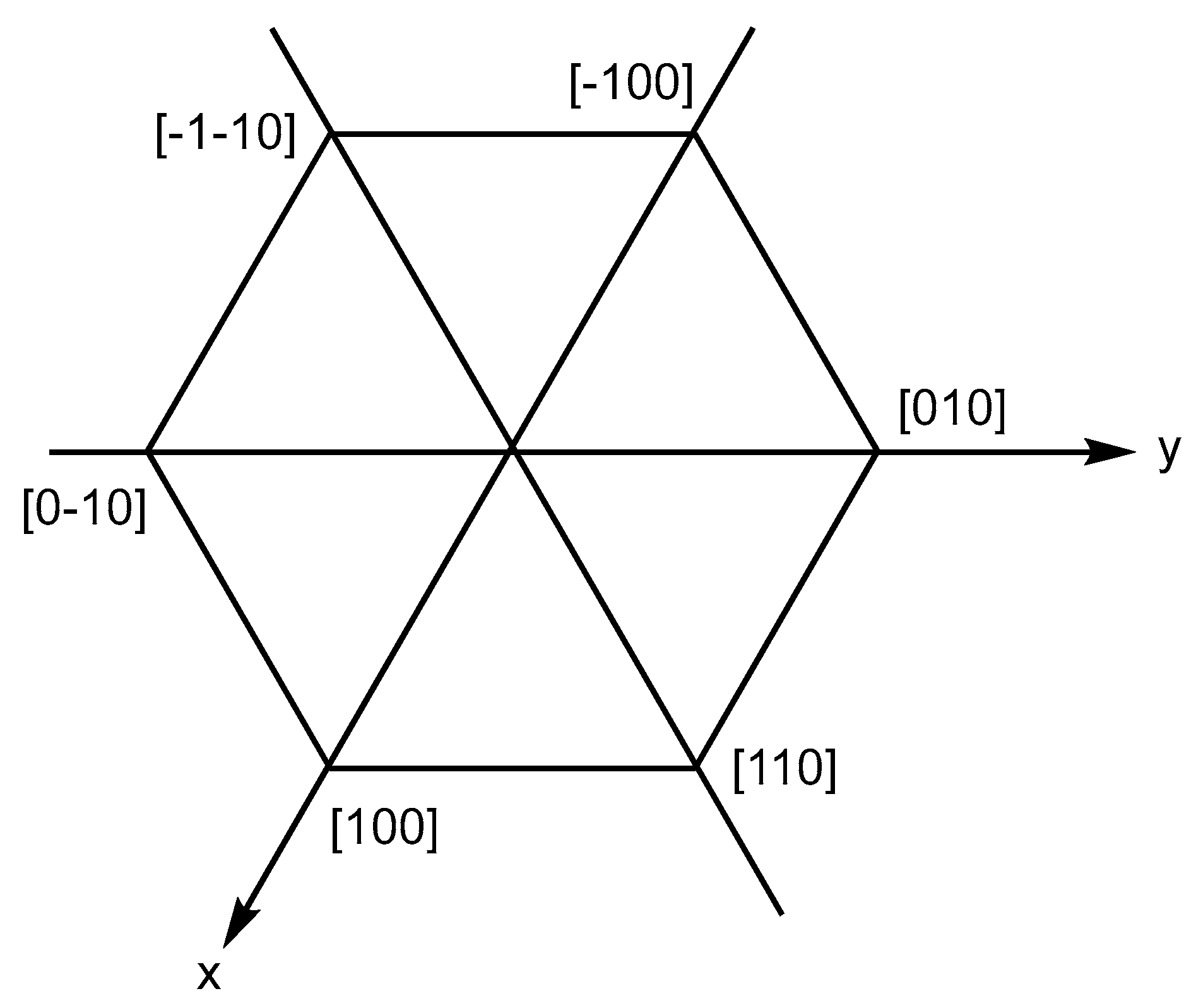

For example, the rotations of the vector [100] around the 6-fold axis parallel to the [

z] axis (

Figure 2) can be performed by calculating

r’ =

q(60°,[

z])·

i·

q(60°,[

z]):

corresponding to vertex [110], as shown in

Figure 2.

By continuing the same procedure, we obtain the quaternion coordinates of the remaining vertices:

These transformations can be applied for the

D6h-symmetric molecule of benzene (C

6H

6), where the C-C aromatic bond length is 1.39 Å and C-H bond is 1.09 Å long. The hexagonal atomic coordinates (cf.

Figure 2) can be easily obtained as:

C1 [1.39, 0, 0], H1 [2.48, 0, 0],

C2 [1.39, 1.39, 0], H2 [2.48, 2.48, 0],

C3 [0, 1.39, 0], H3 [0, 2.48, 0],

C4 [–1.39, 0, 0], H4 [–2.48, 0, 0],

C5 [–1.39, –1.39, 0], H5 [–2.48, –2.48, 0],

C6 [0, –1.39, 0], H6 [0, –2.48, 0].

2.6. Biquaternion for General Application of the Point Symmetry

So far we have discussed the potential application of quaternions for representing symmetry operations in point groups. Quaternions simplify the calculation and avoid the use of matrices. However, the different actions required for the proper and improper rotations,

(inversion center),

(mirror plane

m),

(3-fold inversion axis),

,

etc.), hinder the construction of uniform multiplication tables of symmetry operations for all point groups. The action for proper rotations is defined by Equation 5:

while for improper rotations the action is defined by semi-empirical Equation 10:

The presence of the minus sign in Equation 10 naturally arises from the definition of improper rotations as the combination of proper rotations followed by an inversion.

This problem of different actions can be solved by introducing the square root of –1 as a number, which leads to Hamilton’s less well-known

biquaternion concept (Hamilton, 1853). This square root of –1 is considered as an imaginary number, not a quaternion field. Historically, to avoid confusion with

i used in quaternions (Equations 1-2), Hamilton denoted it as

h. As a number, commutativity of the scalar field

h and quaternion

q is assumed

Accordingly, now Equation 10 for improper rotations (

r’ = –

qrq*) can be rewritten by replacing –1 with

h2:

and by using the commutativity of

h, we obtain

As we treat

h as a number, we can extend the concept of quaternion conjugate to biquaternion “biconjugate”. Given a biquaternion

with

a,

b,

c,

d is a complex number (

f +

gh),

h as defined above,

f,

g are real numbers.

The biconjugate of a biquaternion has exactly the same formula as the conjugate of a quaternion.

So, by using this new definition and noting that (

hq) and (

hq*) are biconjugate of each other, Equations 5 and 10 can be rewritten as:

Because a quaternion conjugate is a special case of a biquaternion biconjugate, this formula is true for both proper and improper rotations. However, compared to Equation 6, the proper and improper rotations are now differentiated as:

One of the simplest point groups involving improper symmetry elements is point group

Ci (

) and its multiplication table of biquaternions (Equation 13) used in symmetry operations (Equation 12) is presented in

Table 3. The two symmetry operations, identity and inversion centre, are represented by biquaternions 1 and

h, respectively.

The multiplication table of biquaternions applied for the representation of symmetry operations in point group

mm2 is presented in

Table 4. The four symmetry elements, identity, two-fold axis 2 along [

z] and two mirror planes perpendicular to [

x] and [

y], are represented by biquaternions 1,

k,

hi and

hj, respectively.

In

Table 3 and

Table 4, some products of multiplied biquaternions are negative, because the biquaternions and quaternions for the identity operation are either 1 or

–1. This follows the quaternion rotation definition (Equation 5), that

q = cos(φ/2) +

n sin(φ/2), which for φ = 0° gives

q = 1, but for φ = 360° it gives

q =

–1. In the geometrical terms, although the final position identical as the original one is obtained, the positive and negative

q sign indicate the even and odd numbers of full rotations of the object, respectively (rotations by 0·360°, 1·360°, 2·360°, 3·360°, 4·360°

etc.). Interestingly, this parity relation applies to the identity composed of inversion centres (

h·

h =

–1,

h·

h·

h·

h = (

h·

h)

2= 1, (

h·

h)

3 =

–1, (

h·

h)

4= 1, (

h·

h)

5 =

–1,

etc.), but not to other improper rotations. For example, for the biquaternions for a combination of two mirror planes

my (

Table 4),

hj·

hj, owing to the commutativity can be rewritten as

h·

h·

j·

j = (

–1)·(

–1) = 1, hence any power of (

hj·

hj)

n= 1. Likewise, all diagonal mirror planes (

), and inversion axes

,

,

,

etc. can be generally encoded as (

h·

N)

2n =1. Nonetheless, the transformation definition in Equation 12 eliminates these negative values for the identity operations and also it unequivocally defines the correspondence of the biquaternions and symmetry operations. Hence the substitution of biquaternions with the corresponding symmetry operations for point group

mm2, yields the multiplication Cayley table (

Table 5).

The multiplications of biquaternions applied for the representation of the cyclic point group

in Table 6, composed of the powers

wn of

w=

h (

Table 3), display no sign changes of the multiplication products, neither for the identity operations nor for any powers

wn, in accordance with the above discussion for the improper rotations. Hence the multiplication table of biquaternions can be straightforwardly rewritten into the Cayley multiplication table of symmetry operations of point group

(

Table 7).

Table 6.

Multiplication table of biquaternions for the symmetry operations in the cyclic point group (S3).

Table 6.

Multiplication table of biquaternions for the symmetry operations in the cyclic point group (S3).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

h

|

|

|

|

|

|

h

|

|

Table 7.

Multiplication Caley table of the symmetry operations in point group (S3).

Table 7.

Multiplication Caley table of the symmetry operations in point group (S3).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|